Abstract

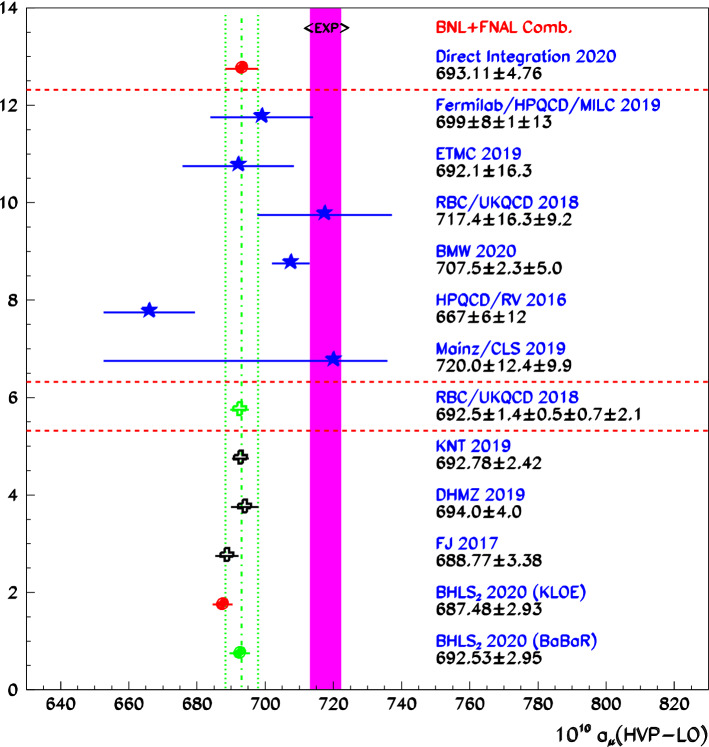

The generic hidden local symmetry (HLS) model has recently given rise to its variant, defined by introducing symmetry breaking mostly in the vector meson sector; the central mechanism is a modification of the covariant derivative at the root of the HLS approach. However, the description of the dipion spectra, especially the Belle one, is not fully satisfactory, whereas the simultaneous dealing with its annihilation sector () is optimum. We show that this issue is solved by means of an additional breaking term which also allows us to consistently include the mixing properties of the system within this extended () scope. This mechanism, an extension of the usual ’t Hooft determinant term, only affects the kinetic energy part of the Lagrangian. One thus obtains a fair account for the dipion spectra which complements the fair account of the annihilation channels already reached. The Belle dipion spectrum is found to provide evidence in favor of a violation of the conserved vector current (CVC) in the lepton decay; this evidence is enforced by imposing the conditions on axial current matrix elements. is found to recover the usual (completed) formulae for the [] mixing parameters, and the global fits return mixing parameter values in agreement with expectations and better uncertainties. Updating the muon hadronic vacuum polarization (HVP), one also argues that the strong tension between the KLOE and BaBar pion form factors imposes to provide two solutions, namely and , in units of , rather than some combination of these. Taking into account common systematics, their differences from the experimental BNL-FNAL average value exhibit significance (KLOE) and (BaBar), with fit probabilities favoring the former.

Introduction

The Standard Model provides the accepted framework which embodies the strong, electromagnetic and weak interactions; it accounts accurately for the observable values reported from low energies up to the highest ones reached at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC). A very few specific measurements look borderline enough, however, to raise a hint of a physics beyond the Standard Model. Among these, the very precisely measured muon anomalous magnetic moment plays a special role; it has generated – and still generates – an important experimental and theoretical activity related to its measurement by the E821 Experiment at Brookhaven National Laboratory (BN)L [1] , for its latest update; this value is at variance with expectations by to , depending on the various predictions, essentially differing by their estimates of the leading-order hadronic vacuum polarization (HVP-LO) as reported in [2] and displayed therein in Fig. 44.

Actually, the significance just quoted refers to using HVP-LO evaluations derived by means of various dispersion relation (DR) methods. In contrast, the Lattice QCD (LQCD) Budapest-Marseille-Wuppertal (BMW) [3] Collaboration recently published an estimate for the HVP-LO [3] claiming 0.8% precision and very close to what is needed to match the BNL measurement; accordingly, the BMW HVP-LO is at variance by more than with any of the reported DR evaluations of the HVP-LO.

The Muon experiment running at the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (FNAL) has very recently published its first results [4] and found them in excellent accord with the previous BNL measurement [1]; the consistency of these two measurements allowing for their combination, the experimental reference value becomes:

Compared to the BNL measurement, this weighted average provides a noticeably improved uncertainty (30% reduction) and a downward shift by . This value still numerically favors the BMW estimate [3] for the HVP-LO over any of the DR ones.

Hence, the puzzle “DR versus data” may become1 “DR versus LQCD,” for which some different kind of physics beyond the Standard Model would have to be invoked. Indeed, if the HVP-LO as derived by DR methods provides a good global electroweak (EW) fit, the change suggested by the BMW evaluation severely impacts the goodness of the global EW fit [6], except if the changes can be localized at low enough energy – Reference [6] quotes 1.94 GeV, assuming the change in the cross sections to be a mere global rescaling.

As long as the missing piece may spread out across the whole non-perturbative region of QCD, which as shown by the KEDR data [7] does not extend much above GeV, one has at hand a somewhat large lever arm. However, the recent KMPS study [8] has shown that the missing contribution to the HVP-LO should come from the energy region below GeV to accommodate the global EW fit. This restricts the requested missing part of the annihilation cross section to a very limited energy region widely explored by several independent groups having collected data using different detectors and colliders; this missing hadronic cross section piece is expected to contribute an additional to the muon HVP-LO, larger than the light-by-light (LbL) contribution to the HVP.

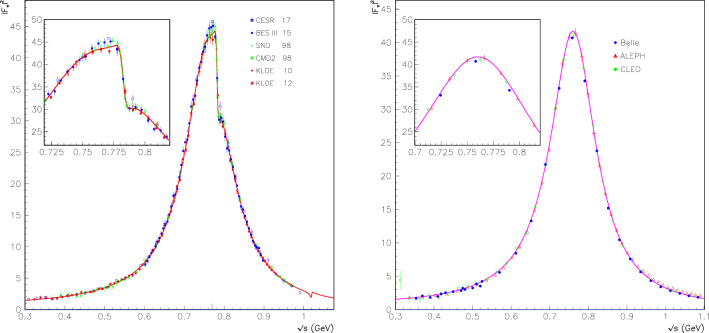

Thus, the energy region to scrutinize is located well inside the realm of the effective resonance Lagrangian approaches (RLA) which have extended the scope of the chiral perturbation theory (ChPT). The inclusion of resonances has given rise to the resonance chiral perturbation theory (RPT) formulation and to the hidden local symmetry (HLS) model which have been proved equivalent [9, 10]. Alongside other processes, the HLS model [11] encompasses the non-anomalous annihilation channels ; it can be complemented by its anomalous sector [12] which allows one to also cover the annihilation channels. Because it deals with only the lowest-lying resonance nonet, the validity range of the HLS Lagrangian naturally extends up to the mass region and is thus quite appropriate to explore the faulty energy region in accordance with QCD which is at the root of the different RLA.

As the BMW evaluation of the muon HVP-LO questions the annihilation data in the energy region up to the meson mass, it is worth testing our understanding of its physics by means of such RLA, in particular the HLS model, which allows us to explore this region already well covered by a large number of data samples in all the significant channels, and thus shrink the window of possibilities to find a non-negligible missing .

As the original HLS model2 assumes U(3) symmetry in both the vector (V) and pseudoscalar (P or PS) sectors, it should obviously be complemented by symmetry breaking inputs in order to account for the rich amount of data samples it is supposed to cover. A first release named BHLS [14, 15], essentially based on the Bando-Kugo-Yamawak (BKY) breaking mechanism [16, 17], extended [18] to account for isospin breaking effects, was proven to perform satisfactorily; however, it exhibited some difficulty in managing the threshold and regions for the dipion and the 3 pion annihilation channels, respectively. In order to solve this issue, the breaking procedure was revisited in depth and gave rise to under two variants [19], namely the Basic Solution (BS) and the reference solution (RS). Both variants are derived by complementing the BKY breaking mechanisms at work in the and sectors of the non-anomalous HLS Lagrangian by additional breaking schemes affecting only the vector meson fields.

Regarding the vector sector of the BS variant, the new breaking input – named covariant derivative (CD) breaking – turns out to perform the substitution3 in the covariant derivative which is a fundamental ingredient of the HLS model; the aim of is to break the symmetry for the components along the basis matrices , and of the canonical Gell–Mann U(3) algebra. The rule naturally propagates to the anomalous sector – i.e. the VVP and VPPP Lagrangian pieces.4

Regarding the PS sector of the BS variant of : Besides the BKY breaking associated with the part of the non-anomalous Lagrangian, the symmetry has been reduced by including the so-called ’t Hooft determinant term [20]; for our purpose, this turns out to add the singlet term to the kinetic energy of the PS fields.

However, if this canceled out the difficulties met at the dipion threshold and in the mass region, the account for the dipion spectra collected in the decay was not fully satisfactory, as can be seen in Table 3 of [19] (see also the discussion in Sect. 17 herein); a closer look indicated that it is the description of the high statistics Belle sample [21] which is faulty. This issue was circumvented by introducing an additional breaking mechanism (the primordial mixing) which defines the RS. The original aim of the present study was to reexamine the issue actually raised by the dipion spectra and to determine which kind of breaking could solve the problem met by the BS variant of . In order to motivate this new breaking scheme – a generalization of the usual ’t Hooft determinant term – Section 3 proceeds to a thorough study of the various dipion spectra and of their impact on the other channels involved in the framework, especially on the pion form factor in the timelike and spacelike regions.

Once motivated, this extended breaking scheme is precisely defined and analyzed in Sects. 4 and . The purpose of Sect. 6 is to address the modifications generated in the non-anomalous Lagrangian derived in [19] by this newly introduced kinetic breaking. Special emphasis is given to the pion form factor involved in the decay of the lepton compared to its partner in annihilations ; it is shown that, while is still fulfilled,5 the CVC assumption is violated in the sector as . As the ALEPH [22] and Cleo [23] spectra easily accommodate a modeling with either of the and constraints, this result emphasizes the interest in having another dipion spectrum with statistics comparable to those of Belle [21] or larger.

However, allowing for a violation of CVC within cannot be solely localized in the sector of the Lagrangian, and it propagates to the anomalous Lagrangian pieces as noted in Sect. 7 and developed in the various appendices. Hence, the description of processes as important as the annihilations is extensively modified and so should be tested versus data, as well as the decay modes and those involving couplings. Prior to this exercise, our set of reference data samples has to be updated to account for new data samples [24, 25] or updated ones [26, 27]. This is done in two steps. First, the purpose of Sect. 8 is to deal with the newly issued three-pion data sample collected by the BESIII Collaboration [24]. It is shown that the BESIII spectrum energies should be appropriately recalibrated to match the common energy scale of the other data samples included in our reference data set, especially in the and peak locations.

On the other hand, dealing with the dipion spectra is of course an important – and controversial – issue because of the long-standing discrepancy between some of the available high statistics data samples. Therefore, we take advantage of the newly published SND dipion spectrum [25] to revisit in Sect. 9 the consistency analysis of the different dipion samples to illustrate the full picture and motivate the way we deal with strong tensions when evaluating physics quantities of importance, especially the muon HVP-LO.

Having updated our reference set of data samples, in Sect. 10 we report on global fits performed under various conditions, updating the results derived with the BS and RS variants of the former version of and those obtained using the extended formulation which is the subject of the present study; this extension will be named for clarity. Section 11 addresses a key topic of the broken HLS model within the context. Indeed, the question of supposedly uncontrolled uncertainties associated with using fit results based on an effective Lagrangian may cast some shadow on this kind of method. To definitively address this issue, the best is to quantify the effect by comparing the estimates for the muon HVP derived from with those derived using more traditional methods under similar conditions. Section 11.1 illustrates for the dipion contribution to the muon HVP that specific biases attributable to using are negligible compared to (i) the way the systematics, especially the normalization uncertainty of the various spectra, are dealt with by the various authors, and (ii) the sample content used to derive one’s estimates. These two major sources of uncertainty are, on the other hand, common to any of the reported evaluations.

With these conclusions at hand, our evaluations of the muon HVP-LO are derived. Our favored result which excludes from the fit the dipion spectra from KLOE08 [28] and BaBar [29, 30] is examined in Sect. 11.2; an alternative solution where all KLOE data samples are discarded in favor of the BaBar one is also presented in Sect. 11.5. The full HVP-LO is constructed (Sect. 11.4) and compared with the other currently reported evaluations in Sect. 11.6. Equipped with the kinetic breaking mechanism defined in Sect. 4.2, is well suited to address the mixing properties of the system more precisely than was done with a similar – but much less sophisticated – modeling in [31]. The final aim is to rely on the results of the fit over the largest set of data samples ever used to derive the corresponding mixing parameter values with optimum accuracy.

The derivation of the axial currents is the subject of Sect. 13. Section 14 addresses the singlet-octet basis parameterization defined by Kaiser and Leutwyler [32–34]; it is shown that allows one to recover the expected extended ChPT relations. In Sect. 15, a similar exercise is performed within the quark flavor basis developed by Feldmann, Kroll, and Stech (FKS) in [35–37] and one also yields the expected results. This clearly represents a valuable piece of information about the dealing of in its PS sector.

The aim of Sects. 16 and 17 is to push a step further: we focus on how isospin symmetry breaking shows up in the axial currents associated with light quark pairs when expressed in terms of PS bare fields – a leading-order approximation. The Kroll conditions [38]:

are then examined in detail and shown to exhibit – at in breakings – unexpected constraints among the various components of the kinetic breaking term. In particular, satisfying the Kroll conditions implies that a kinetic breaking with only a term is not consistent and should be extended in order to involve and quadratic contributions. Whether this property is inherent to only looks unlikely.

In Sect. 18, we report on additional fits suggested by the Kroll conditions and tabulate the fit parameter values. The short Sect. 19 reports on side consequences on some physics parameters, especially the muon HVP-LO. Sections 20 and 21 report on the numerical evaluation of the mixing parameters and compare this with available results from other groups.

Finally, Sect. 22 collects the conclusions of this work, an almost 100% COVID-19 lockdown work.

Preamble: on the free parameters of the model

Significant (anti-)correlations between , and the specific HLS parameter a have been reported in our study [19]; this topic was the purpose of its Sect. 20.1. As parameter correlations may easily be of pure numerical origin,6 we did not go beyond analyzing the issue numerically but emphasized that the physics conclusions were safe, i.e. not shadowed by these correlations.

Actually, one can go a step further. Indeed, it can be remarked that the three parameters , and a are involved only in the piece of the non-anomalous Lagrangian and do not occur in its anomalous FKTUY pieces [12, 13]. Let us consider the pieces inherited from named here and in [19] and and perform therein the following parameter redefinition:

| 1 |

where and are introduced by the breaking matrix affecting which actually writes in the framework.7

One can then check that the dependency upon drops out everywhere except in the mass term shown in the Lagrangian piece (see Eq. (40) below). Obviously, this mass term has no influence on the phenomenology we address and thus is discarded.

It follows from here that the actual values for a, and are in fact out of reach and that the single quantities which can be accessed using the data are their , combinations. Practically, fitting within the framework – having fixed – reduces the parameter freedom and the parameter correlations without any loss in the physics insight, being understood that the derived a and are nothing but and just defined.

On the other hand, specific parameters are involved in order to deal with the system. They come from the transformation leading from the renormalized fields – those which diagonalize the PS kinetic energy term – to the physically observable states and can be found8 in Sect. 5. These parameters have been named , and in accordance with the usual custom [35, 38].

In our previous works on the HLS model, in particular [14, 19], one of the () mixing angles [32, 33] was constrained () following an earlier study [31]. This turns out to impose the condition that the mixing angle be algebraically related to the BKY parameter and the nonet symmetry breaking parameter (see Sect. 4.4 in [14]). The experimental picture having dramatically changed since [31], this assumption certainly deserve to be revisited, as will be done in the present work. Moreover, we also imposed [39]:

| 2 |

As a whole, this reduces the number of free parameters by two units without any degradation of the fit quality or any change in the HVP values.

However, for the present purpose, it has been found worthwhile to release these constraints and let , and vary freely. When analyzing below the mixing properties, this assumption will be revisited in a wider context.

Revisiting the dipion spectra: a puzzle?

Section 17 of [19] reported the properties of our set of – more than 50 – data samples when submitted to global fits based on either of the reference solution (RS) and basic solution (BS) variants of the model. Table 3 therein displays a detailed account of the information returned by the fits for the various physics channels. More precisely, this table shows that the reported averages for the displayed groups of the data samples held are generally of the order 1 – with the sole exception of the data sample from [40].

The channel overall piece of information displayed in this Table 3 covers a data group merging the samples provided by the Aleph [22], Cleo [23] and Belle [21] collaborations. One can read9 therein: (RS variant) and (BS variant). In the following, one may refer to these data samples as A, C and B, respectively.

However, this fair behavior of the channel data actually hides contrasted behaviors among the three samples gathered inside this group. This issue deserves reexamination10 within the [19] context.

It was noted in Sect. 11 of [19] that the subtraction polynomials and of the and pion loops, respectively, involved in the pion form factors are different, allowing this way for relative isospin symmetry breaking (IB) effects; more precisely, they are related by:

| 3 |

and the polynomial is also determined by fit.

Within the context, , as any of the other loops involved, is a second-degree polynomial with floating parameters. However, in order to obtain good global fits when including the data – especially the Belle spectrum [21] – the degree of has been increased to the third degree in the BS variant11 of . Actually, this degree assumption is not harmless, as it corresponds to introducing a non-renormalizable counter term in the renormalized Lagrangian. As A and C are well managed within the BHLS framework with a second-degree , the issue raised by the Belle spectrum is thus worthy of being cautiously examined; this is the matter of the present section.

For the series of () global fits presented in the present section, we have chosen to discard the data covering the annihilation channel to shorten the fit code execution times. The lowest energy data point of the Cleo spectrum [23] is discarded as outlier; with this proviso, the three spectra [21–23] are fully addressed within our fits from threshold up to 1 GeV.

Formally, the differences between the dipion spectra in the decay and in the annihilation should solely follow from isospin symmetry breaking (IB) effects. Therefore, a real understanding of these supposes a minima a simultaneous dealing with the annihilation channel and with the dipion spectra collected in the decay. The annihilation data addressed in our fitting codes – CMD-2 [42–44], SND [45] KLOE [46, 47], BESIII [26], Cleo-c [48] – have been presented12 in detail in Sect. 13 of [19].

Actually, the BESIII Collaboration has recently published an erratum [27] to their [26] which essentially confirms the original spectrum but drastically reduces the statistical uncertainties. This will not be discussed at length and we only quote the evolution: running our standard code with the uncorrected BESIII dipion spectrum [26], the various fits return , whereas running it with the corrected data [27] yields ; this more realistic goodness of fit clearly indicates that the errors are indeed better understood, allowing the BESIII spectrum to really influence the physics results derived from fits.

We should also note that the two dipion spectra from KLOE08 [28] and BaBar [29, 30], exhibiting a poor consistency with all the () others, are discarded since the very beginning of the HLS modeling program [14, 15]. Finally, the SND dipion spectrum [25] measured over the GeV energy interval will be analyzed separately below.

Fitting the dipion spectra

The spectra submitted to global fits are defined by:

| 4 |

using the event distributions and branching fractions provided by each of the Aleph [22], Belle [21] and Cleo [23] collaborations. The full width is derived from its lifetime taken from [49]. The relation with the pion form factor is:

| 5 |

where is derived from the Lagrangian [19] and collects the short-range radiative corrections [50]; the long-range radiative corrections are collected in and evaluated on the basis of [51–53]. The normalization of the full form factor at the origin is, thus, given by the product in the standard , which automatically fulfills13.

Anticipating the following sections, let us state that we will define an extension of standard [19] to allow for a violation of CVC in the sector; it will be named . The main difference – not the only one – between and the standard [19] is that it fulfills where is a floating parameter of order reflecting a symmetry breaking. Moreover, setting therein allows us to recover exactly the standard [19]. When , the rescaling generated by is numerically modulated by accompanying changes in the internal structure of the term in . On the other hand, as the rest of the non-anomalous Lagrangian pieces are unchanged, the properties of remain unchanged; in particular, the condition is still valid as in because the term of vanishes by having stated [19] .

As the data analysis is the main motivation for the forthcoming extension, it was found worthwhile to display, besides the standard fit results, the corresponding information, prior to dealing with its derivation.14

global fits excluding the spacelike data

Table 1 reports on a series of fits aimed at coping with the topic; the global fits reported in this subsection discard the spacelike data [54, 55], and the discussion emphasizes solely the behavior of the dipion data from the annihilation channel and from the decay.

Table 1.

Global fit properties (spacelike data excluded): values for the various sample groups; the numbers of data points are given between parentheses. The subtraction polynomial is always second degree except when explicitly stated (second data column). The tag “spectra” stands for fitting with the reported A, B and C dipion spectra; the tag “lineshapes” stands for the case when these spectra are normalized to their integral over the fitted energy range; the tag “rescaled” covers the case when a common rescaling factor is applied to the three dipion spectra. The last data column displays the results obtained fitting within

| fit (excl. spacelike) | () | free spectra | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spectra | Spectra (3rd deg.) | Lineshapes | Rescaled | ||

| NSK (127) | 138 | 136 | 135 | 138 | 138 |

| KLOE (135) | 146 | 143 | 145 | 144 | 140 |

| BESIII (60) | 47 | 47 | 48 | 48 | 50 |

| (ABC) (84) | 122 | 92 | 79 | 79 | 78 |

| (ALEPH) (37) | 41 | 22 | 23 | 23 | 21 |

| (CLEO) (28) | 33 | 34 | 30 | 31 | 32 |

| (Belle) (19) | 48 | 36 | 26 | 25 | 25 |

| Fit Prob. | 66% | 93% | 95% | 94% | 96% |

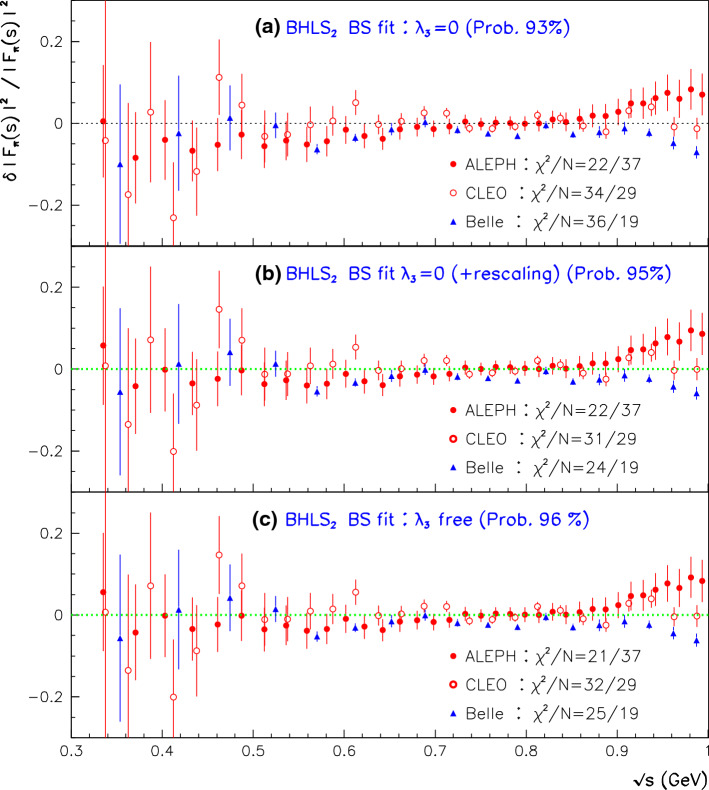

As stated just above, the reference therein to the parameter anticipates the extension proposed below, and states that the condition is strictly identical to having running, in particular its BS variant [19] solely used all along the present work, except as otherwise stated (Fig. 1).

The first data column displays the global fit performed using the published A, B and C spectra imposing the polynomial (see Eq. (3)) to be second degree. Obviously, the averages are reasonable for all the displayed data samples or groups shown (as well as those not shown) except for Belle, which yields the unacceptable average .

-

The simplest (ad hoc) choice to better accommodate the Belle spectrum turns out to allow to be third degree. Doing this, the second data column shows that the fit returns a fair probability, as already known since [19]. Indeed, besides a quite marginal improvement of the account, one observes a sensible improvement in the description of the Aleph () and Belle () spectra, whereas the Cleo spectrum remains unchanged and satisfactory. The improvement for the Belle spectrum is significant () but not fully satisfactory. Nevertheless, the top panel in Fig. 2 shows that the normalized residuals for the spectra exhibit a reasonably flat behavior, thanks to having a third-degree .

So, once the degree for is appropriate, gets a fair account for the A and C data and an acceptable one for the Belle spectrum.

However, inspired by the fit summary Table VII in the Belle paper [21], we have addressed two other similar strategies:

Instead of fitting the A, B and C spectra as such, we choose to use each of them normalized to its integral over the fitting energy range ( GeV); i.e we rather fit the A, B, C lineshapes within the global framework. In this case, a second-degree is already sufficient and yields a fair global fit (95% probability). The corresponding results are displayed in the third data column; they are clearly satisfactory in both the annihilation channel and the sector. In this configuration, the Belle spectrum undergoes an individual improvement by 10 units and comes out with a more reasonable .

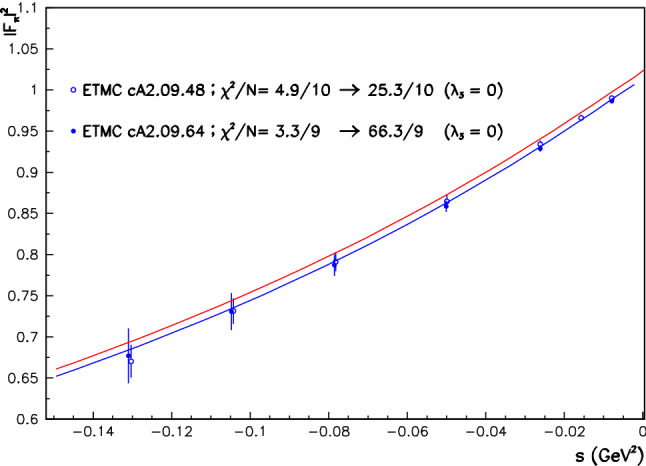

Fig. 1.

derived from the fits with (red curve) and with (blue curve). The LQCD data points from [56], not fitted, are superimposed. The values for average distances are shown for and

Fig. 2.

Normalized residuals derived in the global fits excluding the spacelike data. Top panel displays the case when A, B and C as such are simultaneously fitted; the middle panel displays the case where a common rescaling factor is applied to A, B and C. The bottom panel reports the corresponding results derived by fitting A, B and C as such within the framework

Stated otherwise, once the spectra are normalized, provides a fairly good simultaneous account of the A, B and C spectra and proves that the A, B and C lineshapes are quite consistent with each other without any need for some ad hoc trick. Moreover, there is no point in going beyond the second degree for .

An obviously similar approach to the lineshape method just emphasized is to let the pion form factor be such that15. This is inspired by the stand-alone fit performed by Belle and reported in Table VII of their [21].

In this study, a first fit has been performed across the full energy range of the Belle dipion spectrum using a Gounaris–Sakurai (GS) pion form factor – which fulfills ; this fit is the matter of the leftmost data column of their Table VII and reports . Belle also reports therein a second fit, having allowed for a mere rescaling

of their GS parameterization; the corresponding results are reported in the rightmost data column of their Table VII with . The noticeable 15-unit gain for the value (a 4 effect), resulting from a single additional floating parameter, stresses the relevance of what was just named . Let us perform likewise within the global context.

- As the standard [19] provides , one performs as Belle using rescaling factors of the form . We have first performed global fits using a single spectrum (A, B, C in turn) and derived the following results:

which, unexpectedly, indicate that B, as well as A and C, nicely accommodate a rescaling factor without degrading the description of the annihilation data. We also performed a global fit merging the three spectra each renormalized by a common (single) scale factor. We get:6

more details can be found in the fourth data column of Table 1; the normalized residuals derived from this fit are displayed in the middle panel of Fig. 2. Comparing the fit results reported here, one observes a 13-unit gain compared to using a third-degree , in line with the Belle fits – with exactly the same model parameter freedom as comes replacing the coefficient dropped by reducing the degree of by one unit.7

Such a common rescaling is certainly beyond experimental biases as, moreover, A, B and C have been collected with different detectors by independent teams. This is also much beyond the reported uncertainties on their respective branching fractions which govern the absolute scale of the fitted spectra.

So, one reaches an outstanding fit quality by rescaling the three spectra by the same amount; this improvement of the sector is not obtained at the expense of degrading, even marginally, the account of the annihilation data. Within the context – and discarding the spacelike spectra – it is found that , a non-negligible value. This amount is certainly related to intrinsic details of the Lagrangian model, noticeably the mass and width differences of the neutral and charged mesons which also contribute to the absolute scale.

Finally, the last data column in Table 1 shows that the forthcoming succeeds in producing a nice fit, very close to ones corresponding to the information displayed by Eq. (7) and reported in the fourth data column of Table 1. The normalized residuals are displayed in the bottom panel of Fig. 2.

One can observe that the three sets of normalized residuals shown in Fig. 2 are almost identical and each is quite acceptable. Finally, we should stress that in all configurations, Table 1 exhibits a fair account of the A and C spectra; it is therefore noticeable, and even amazing, that a remarkable simultaneous fit of A, C and B can also be derived. Moreover, in both kinds of configurations (rescaling or not), the same, fair account of all the annihilation data is obtained.

global fits including the spacelike data

The fit properties and parameter values reported just above have been derived using the dipion spectra only in the timelike region for both the and pairs. Moreover, it has been shown [19] that, within the framework, the same analytic function describes fairly well the pion form factor in the spacelike and timelike energy regions. It is, therefore, desirable to enforce the impact of the analyticity requirement within the BHLS framework by requiring a simultaneous account of both energy regions.

Therefore, including the spacelike data [54, 55] in the set of samples submitted to the global fit appears a natural step. A priori, this should mostly affect ; however, as and are deeply interconnected within the framework, extending the fit to the spacelike region can be of consequence for both form factors. This subsection reports on the global fit results derived when also including the spacelike data.

The first data column of Table 2 displays the fit information when fitting with using a second-degree polynomial, having discarded the Belle spectrum. As evidenced by its reported probability (93%), the fit exhibits a nice account of each group of data samples as we always observe . This proves that the need for a third-degree is caused solely by the Belle (B) spectrum.

Table 2.

Global fit properties (including the spacelike data): of the various sample groups; their numbers of data points are shown between parentheses. The subtraction polynomial is always second degree except when explicitly stated (second data column). The tag “spectra” stands for fitting the A, B and C dipion spectra as such; the tag “rescaled” covers the case when a common rescaling factor is applied to the three dipion spectra

| Fitting framework (incl. spacelike) | () | ( free) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spectra | Spectra (3rd deg.) | Rescaled (2nd deg.) | Spectra | Rescaled | |

| NSK (127) | 138 | 134 | 137 | 138 | 136 |

| KLOE (135) | 139 | 146 | 154 | 140 | 141 |

| BESIII (60) | 48 | 47 | 47 | 48 | 48 |

| Spacelike (59) | 62 | 65 | 77 | 62 | 61 |

| (ABC) (84) | 92 | 88 | 81 | 77 | |

| (ALEPH) (37) | 24 | 23 | 28 | 25 | 21 |

| (CLEO) (28) | 30 | 33 | 30 | 31 | 32 |

| (Belle) (19) | 37 | 30 | 25 | 24 | |

| Fit Prob. | 93% | 89% | 79% | 91% | 94% |

The second data column in this table reports the same fit also including the Belle spectrum but with a third-degree ; it exactly corresponds to those already reported in the second data column of Table 1. The average of the various sample groups are observed to be quite similar, including for the Belle data sample (); for the spacelike data, it yields a favorable . This case corresponds to the fit configurations previously used in [19]; with 89% probability, it is clearly a satisfactory solution, and one does not observe any degradation of the goodness of fit by having included the spacelike data.

The fit reported in the third data column of Table 2 is the exact analog of the one displayed in the fourth data column of Table 1, also taking into account the spacelike data. Here, also, carries the second degree. The best fit returns a global rescaling factor with:

| 8 |

Comparing with Eq. (7), one observes a drop in probability produced by the inclusion of the spacelike data within the global fit procedure (). Compared to having excluded the spacelike data, the effect is noticeable on the KLOE data () and for the data (). On the other hand, having reduced the degree, one observes a clear degradation of the spacelike data account as . Nevertheless, even if not the best reachable fit, as will be seen shortly, this configuration provides a quite reasonable picture.

The last two data columns in Table 2 refer to the extended model fit results. In this case, we have examined the solution (fourth data column) and, for completeness, also performed the analysis with an additional rescaling of the spectra (fifth data column).

One clearly observes that the original spectra exhibit uniformly good properties in all channels, and the fit yields a 91% probability, as displayed in the fourth data column. Complemented with an additional common rescaling of the spectra, some marginal improvement is observed in the description of these as shown in the last data column of Table 2.

In contrast to the preceding subsection (no dealing with the spacelike data), using a second-degree and rescaling the spectra, while improving the sector, leads to a degraded account of the spacelike data () and a loss of the remarkable prediction of the LQCD pion form factor data [56] reported in [19]; this is illustrated by Fig. 1. Comparing this Figure with Fig. 8 of [19], derived by excluding the data from the fit, one observes good agreement with the solution.16 Finally, the last two data columns in Table 2 show that perfectly succeeds in recovering uniformly good ’s with fit probabilities exceeding 90% and a fair account of all channels.

Summary

Therefore, after including the data within the minimization procedure, a fit using a third-degree succeeds, recalling the conclusions already reached in [19]; however, one has to accept an average of 1.95 for Belle, whereas those for Aleph and Cleo are 0.62 and 1.18, respectively.

The fact that A, B and C carry a common lineshape may look hardly accidental. However, in contrast to Table 1, where evidence for solely a rescaling looks reasonable, Table 2 indicates that a mere rescaling is insufficient – not to mention that the prediction for the LQCD pion form factor data [56] is severely degraded compared to [19]. In this case, – complemented or not with a common rescaling of the spectra – performs nicely and fulfills all desirable analyticity requirements using a second-degree only, as should be preferred. The fits reported in Sects. 3.2 and 3.3 convincingly illustrate that the third degree looks somewhat ad hoc and can be avoided.

Therefore, we are led to complement the covariant derivative (CD) breaking introduced in [19] by an additional term (see Sect. 4) which breaks the kinetic sector of the HLS Lagrangian. This points toward a violation of CVC in the sector (at a level for ). For completeness, we also examine the effect of a possible rescaling complementing the CVC breaking (generated by a nonzero ); this is reported in the last data column of Table 2. This rescaling may correspond to a (higher order?) correction to the product (at a level). However, this additional freedom does not produce a significant effect and is discarded from now on.

To conclude, the present analysis highlights the importance of having at one’s disposal a new high statistics dipion spectrum; it is, indeed, of importance to reach conclusions about the specific behavior exhibited by the Belle spectrum within global fits. The challenging properties exhibited by fitting the dipion spectra or, alternatively, their lineshapes may look amazing enough to call for a confirmation of the Belle spectrum properties. Indeed, it is not unlikely that the much higher statistics of the Belle spectrum (50 times those of Cleo [21]) allow a finer structure to show up, calling for a more refined description.

Extending the breaking scheme

The hidden local symmetry model [13] has been supplied with specific symmetry breaking mechanisms to provide the framework [19] within which almost all annihilation channels occurring up to the mass are encompassed. This allowed for a simultaneous fit of almost all collected data samples covering the non-anomalous decay channels (, , ) and anomalous ones [12] (, , ). As clear from [19], one gets a fair description with superb goodness of fit.

As just emphasized in Sect. 3, the decay mode is also a natural part of the successive HLS frameworks [14, 19, 41, 57, 58]. However, as illustrated by Table 2, the issue is whether one must consider, besides the ALEPH [22] and Cleo [23] spectra, those from Belle [21]. Our present goal is to define an extension of which can naturally simultaneously encompass the A, C and B spectra and continuously recover the framework in some smooth limit. Anticipatively, this extension has been named .

has been constructed by considering, besides the BKY mechanism [16, 17], the covariant derivative breaking and the primordial mixing procedures – see Sects. 4 and 8 of [19]. These essentially address the vector sector of the HLS model and rotations allow us to render the Lagrangian canonical. This also lets the vector meson kinetic energy supplied by the Yang–Mills Lagrangian be canonical.

Regarding the pseudoscalar (PS) sector, the BKY mechanism [14, 16, 17] also contributes to break the symmetries of the HLS model. We should also emphasize that the mass breaking in the kaon sector is at the origin of the dynamical mixing of the vector mesons [57], which is the central piece of the various broken versions of the HLS model. Indeed, thanks to having different charged and neutral kaon loops, the (, , ) mass matrix at one loop becomes non-diagonal and, thus, imposes another step in the vector field redefinition [14, 19]. This back-and-forth play between vector field redefinition and isospin symmetry breaking in the PS sector should be noted.

Besides the two mechanisms just listed, in order to account for the physics of the anomalous processes, the ’t Hooft determinant terms [20], more precisely its kinetic part, provide the needed nonet symmetry breaking in the PS sector. Moreover, higher-order and loop terms in chiral perturbation theory and QED corrections are expected to extend the breaking of the PS kinetic energy term beyond the singlet component. It is the purpose of the present section to extend the kinetic breaking17 to the full system; one already knows from the preceding section that it provides a consistent picture of the sector as it renders consistent the account of the A, C and B spectra.

Once these symmetries have been broken, the PS kinetic energy term of the HLS Lagrangian is no longer diagonal, and a field redefinition is mandatory to restore its canonical form.18 This is performed in the two steps addressed right now.

Diagonalization of the PS kinetic energy piece

In the BHLS/ model, the pseudoscalar (PS) kinetic energy term is written as [14, 19]:

| 9 |

where is the so-called BKY breaking matrix at work in the sector of the non-anomalous Lagrangian [19] (); combining the new breaking scheme defined in [17] and the extension proposed in [18], we write [14]:

| 10 |

The departure from unity of the and entries ( and ) of , numerically small [14], are treated as perturbations19 in amplitude calculations whereas occurring as the entry is expected and treated as ; this entry can be also referred to as flavor breaking [35–37]. Assuming the pion decay constant occurring in the HLS-based Lagrangian models is the observed one, its renormalization is unnecessary and has been shown to imply [14] . Therefore, phenomenologically, one is left with only two free parameters, and .

To restore the PS kinetic energy of the piece of the BKY broken HLS Lagrangians to canonical form, a first field transform [31] is performed:

| 11 |

is the (first step) renormalized PS field matrix which brings back into canonical form. One has:

| 12 |

which defines the matrix W. We use the notation to recall the specific Gell–Mann matrix to which the neutral pion is associated, and devote the notation to the corresponding mass eigenstate. The entries of W in Eq. (12) are given by:

| 13 |

which are used all along this study. For further use, Eq. (12) is re-expressed:

| 14 |

In terms of the R1 renormalized fields, is thus canonical:

| 15 |

The following expression of in the U(3) algebra canonical basis clearly exhibits the precise structure of the BKY breaking procedure:

| 16 |

where I is the unit matrix. complements the usual Gell–Mann matrices normalized by Tr.

Displayed in this way, the departure from unity of the breaking matrix exhibits its three expected contributions. , a purely isospin symmetry breaking (ISB) parameter, is associated with , as it should be. In contrast, the effect of the flavor breaking amount will be met several times below. Its origin is naturally shared between and ; both simultaneously vanish in the “no-BKY breaking” limit . So, as expected, the BKY matrix entry, combines correlatedly SU(3) and nonet symmetry (NSB) breakings in the PS sector. Let us also note that [19] , as will be noted below in the modified context – see Eq. (71).

The kinetic breaking: a generalization of the ’t Hooft term

A more direct breaking of the U(3) symmetric PS field matrix to SU has also been found phenomenologically requested to successfully deal with the whole BHLS realm of experimental data [14, 19]. These are the so-called ’t Hooft determinant terms [20, 31–33]; limiting ourselves here to the kinetic energy term, we have been led to supplement the HLS kinetic energy piece by:

| 17 |

where P is the usual U(3) symmetric pseudoscalar bare field matrix [14, 19], and the (measured) charged pion decay constant. This relation is connected with by the identity:

Expanding in Eq. (17), the leading order term is20:

| 18 |

only involving the singlet PS bare field .

The ’t Hooft term tool, already used in the previous broken HLS versions, can be fruitfully generalized. Indeed, Eq. (17) can be interpreted as:

| 19 |

where21.

Equation (19) gives a hint that other well-chosen forms of the matrix may exhibit interesting properties. Indeed, it clearly permits us to define mechanisms not limited to only nonet symmetry breaking. This leads us to propose the following choice for :

| 20 |

as it manifestly allows for a breaking of isospin symmetry and enriches the ability of the HLS model to cover the mixing properties. As will be seen shortly, it also leads to differentiate the pion pair couplings to and . With this choice, Eq. (19) becomes at leading order:

| 21 |

This form for is certainly not the only way to generalize the usual ’t Hooft term. For instance, among other possible choices, one could quote:

| 22 |

which turns out to drop the crossed terms in Eq. (21) – and in all expressions reported below. On the other hand, as will be seen in Sect. 16, it happens that a generalization such as Eq. (20) is necessary to allow to fulfill expected properties of the axial currents in a nontrivial way.

In order to deal with kaons or charged pions, one could also define appropriate projectors ; however, this does not appear necessary, as the BKY breaking already produces the needed breaking effects [14, 19].

In the broken HLS frameworks previously defined, the (single) ’t Hooft breaking parameter was counted as when truncating the Lagrangian to its leading order terms in all the previously defined breaking parameters [19]. Consistency, thus, implies counting all the just introduced as .

The PS kinetic energy of the extended Lagrangian

The full PS kinetic energy term of the broken HLS Lagrangians is provided by their Lagrangian piece:

| 23 |

Performing the change of fields of Eq. (12) which diagonalizes and using as given in Eq. (20), the full kinetic energy term can be written:

| 24 |

omitting the kaon and (charged) pion terms which are standard and displayed elsewhere [14, 19]. We have defined:

| 25 |

where A, B, C are given by Eq. (13). One should note the intricate combination of the ’t Hooft breaking parameters with the BKY parameter .

Defining the (co-)vector , can be written:

| 26 |

M being the sum of the unit matrix and of a rank 1 we write:

| 27 |

The second step renormalized fields are defined by:

| 28 |

which brings the kinetic energy into canonical form:

| 29 |

At the same order, one has:

| 30 |

and, finally, using Eqs. (13) and (14):

| 31 |

where W is defined in Eq. (12).

PS meson mass eigenstates: the physical PS field basis

The PS field R basis renders the kinetic energy term canonical; nevertheless, this R basis is not expected to diagonalize the PS mass term into its mass eigenstates (). Indeed, for instance, up to small perturbations, the and are almost pure singlet and octet field combinations, while the physically observed and mass eigenstate fields are mixtures of these. In order to preserve the canonical structure of the PS kinetic energy one should consider the transformation from R fields to the physically observed mass eigenstates; as the PS mass term (not shown) is certainly a positive definite quadratic form, this transformation should be a pure rotation.

In the traditional approach, the physical and fields are related to the singlet-octet states by the so-called one-angle transform:

| 32 |

However, extending to the mass eigenstate () triplet, one expects a three-dimensional rotation and thus three angles. Adopting the Leutwyler parameterization [39], one has:

| 33 |

to relate the R fields which diagonalize the kinetic energy to the physical (i.e. mass eigenstates) neutral PS fields. The three angles occurring there (, and even ) are assumed perturbations; nevertheless, it looks better to stick close to the one-angle picture by keeping the trigonometric functions of , the so-called third mixing angle [31]; for clarity and for the sake of comparison with other works, is not treated as manifestly small. The Leutwyler rotation matrix can be factored out into a product of two rotation matrices:

| 34 |

Substantially, the second matrix in the right-hand side of Eq. (34) reflects isospin breaking effects. In the following, we name and the two matrices showing up there; they fulfill:

| 35 |

up to terms of degree higher than 1 in . This implies [39]:

| 36 |

As for their perturbative order, and are treated as . Equations (36) and (31) allow us to define the (linear) relationship between the physical , and states and their bare partners occurring in the original HLS Lagrangians.

Extended : the non-anomalous Lagrangian

The non-anomalous Lagrangian in the present approach can also be written:

| 37 |

as in [19]. As in this Reference, one splits up the first two terms in a more appropriate way:

| 38 |

essentially addresses the physics of the annihilations to charged pions and to kaons pairs; within the present breaking scheme, it remains strictly identical to those displayed in Appendix A.1 of [19]. The is also unchanged, as it does not address PS meson interactions; it is identical to those displayed in Appendix A.3 of [19]. Both pieces have not to be discussed any further, and their expressions will not be reproduced here to avoid lengthy repetition.

All modifications induced by the generalized ’t Hooft kinetic breaking mechanism are concentrated in the piece and are displayed right now. Using22 ():

| 39 |

the expression of in terms of bare PS fields is given, at lowest order in the breaking parameters, by:

| 40 |

where we have limited ourselves to displaying only the terms relevant for our purpose. The (classical) photon and W mass terms [13, 17] are not considered and are given only for completeness. However, it is worth recalling that the photon mass term does not prevent the photon pole from residing at as required [62], at leading order. The interaction part of can be split into several pieces. Discarding couplings of the form , we can write:

| 41 |

with:

| 42 |

and:

| 43 |

where the subscript b indicates that the field is bare. Equation (31) provides the relationship between bare and renormalized states, in particular:

| 44 |

The occurrence of the parameter generates a decoupling of the and interaction intensities. Also using Eq. (36), Eqs. (43) and (44) give at first non-leading order:

| 45 |

in terms of physical neutral PS fields, and then:

| 46 |

Once more, the rest of the is unchanged compared to their expressions [19].

Regarding the pion form factor in the decay, the changes versus Sect. 11.1 in [19] and the present are very limited:

| 47 |

This implies a global rescaling of the pion form factor by ; it also implies that the loop acquires a factor of . The transition amplitude and the propagator are changed correspondingly (see Sect. 11.1 in [19]). On the other hand, remains identical to its expression, as well as both kaon form factors.

Extended : the anomalous Lagrangian pieces

If only the part of the non-anomalous Lagrangian is affected by the kinetic breaking presented above, all the anomalous FKTUY pieces [12, 13] are concerned.

The Lagrangian pieces of relevance for the phenomenology we address are, on the one hand:

| 48 |

where Q is the usual quark charge matrix and A, V and P respectively denote the electromagnetic field, the vector field matrix and the U(3) symmetric bare pseudoscalar field matrix as defined in [14] regarding their normalization. As we did not find any important improvement by assuming , the difference of these has been set to zero; consequently, the Lagrangian piece [13] drops out.

On the other hand, the following pieces should also be considered:

| 49 |

These involve, besides and , a third parameter which is also not fixed within the HLS framework [13] and should be derived from the minimization procedure. For easier reading of the text, we have found it worth pushing them into Appendices A and B.

Regarding the pseudoscalar fields, the Lagrangian pieces listed in Appendices A and B are expressed in terms of the physically observed whereas, for simplicity, the vector mesons are expressed in terms of their ideal combinations: and . The procedures to derive the couplings to the physically observed and and to construct the cross sections for the annihilations are given in full detail in Sect. 12 of [19]. Nevertheless, we have found it worthwhile to construct the amplitude and the cross section for the annihilations in the extended framework; this information23 is provided in Appendix C.

Update of the 3 annihilation channel

The BESIII Collaboration has recently published the Born cross section spectrum [24] for the annihilation over the GeV energy range collected in the ISR mode. This new data sample complements the spectra collected at the VEPP-2M Collider by CMD2 [43, 63–65] and SND [66, 67] covering the and peak regions. Besides, the only data on the 3 cross section stretching over the intermediate region were collected much earlier [68] by the former neutral detector (ND). As the measurement by BaBar [69] only covers the GeV region, it is of no concern for physics studies up to the signal. On the other hand, previous independent analyses [19, 70] indicate that the CMD2 spectrum [65] returns an average per point, much above 2 units, which led to discard it from global approaches.

The BESIII sample [24] is the first three-pion sample to encompass the whole range of validity of the HLS model, providing a doubling of the number of candidate data points and, additionally, the first cross-check of the cross section behavior in the energy region between the narrow and signals.

We first examine how it fits within the global HLS framework in isolation (i.e. as a single representative of the 3 annihilation channel) and determine its consistency with the already analyzed data samples covering the other annihilation channels, namely , and both modes. A second step is devoted to consistency studies between the BESIII spectrum and those previously collected in the same 3 channel by the ND [68], CMD2 [43, 63, 64] and SND [66, 67] detectors.

The BESIII 3 data sample in isolation within

The fit procedure already developed within the previous BHLS frameworks [14, 19] – and closely followed here – relies on a global minimization. In order to include the BESIII sample within the framework,24 one should first define its contribution to the global . This requires us to define the error covariance matrix appropriately merging the statistical and systematic uncertainties provided by the BESIII Collaboration together with its spectrum, and paying special care to the normalization uncertainty treatment. This should be done by closely following the information provided together with its spectrum by the Collaboration.25

For definiteness, the data point of the BESIII sample [24] at the energy squared is:

using obvious notations; it is useful to define , the experimental fractional systematic error. Then, the elements of the full covariance matrix W associated with the BESIII spectrum are written as:

| 50 |

where the indices run over the number of data points (). V is the (diagonal) matrix of the squared statistical errors (), and is the reported fractional systematic error at the data point of energy (squared) , defined as just above. The systematic errors are considered point-to-point correlated and reflecting a (global) normalization uncertainty.

At the start of the fit iterative procedure, the natural choice for A is the vector of measurements itself (); in the iterations afterwards, it is highly recommended [73–75] to replace the measurements by the fitting model function M () derived at the previous iteration step in order to avoid the occurrence of biases. Then, the experiment contribution to the global is written as:

| 51 |

Moreover, a normalization correction naturally follows from the global scale uncertainty. It is a derived quantity of the minimization procedure. Defining the vector B (), this correction is given by [19, 75]:

| 52 |

For the purpose of graphical representation, one could either perform the replacement , or apply the correction to the model function . When graphically comparing several spectra, the former option should clearly be preferred, as indeed, even if not submitted to the fit, other parent data samples can be fruitfully represented in the same plot by performing the change26:

using the BESIII fit function M(s). Such a plot is obviously a relevant visual piece of information.

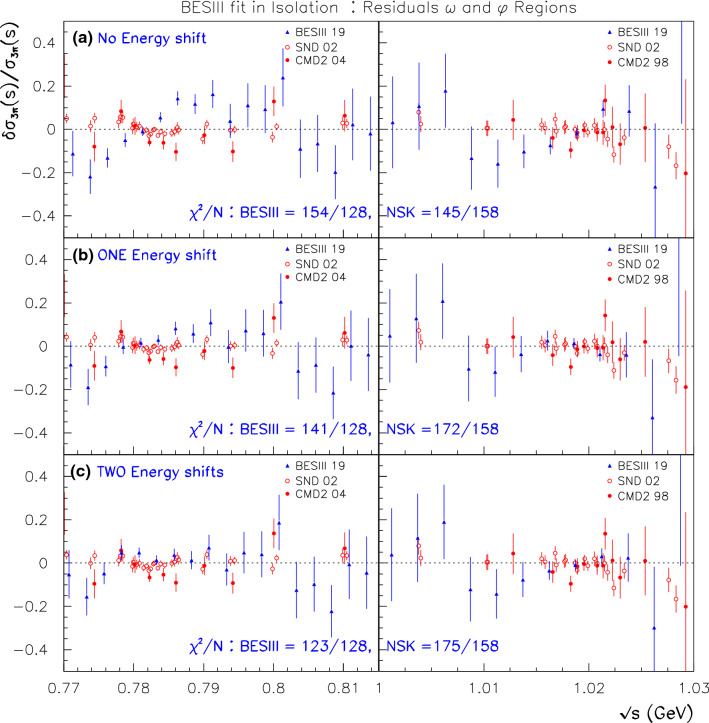

A global fit involving all data covering the , and both channels and only the BESIII spectrum to cover the 3 annihilation final state has been performed and returns, for the BESIII sample,27.

The top panels in Fig. 3 display the distribution of the BESIII normalized residuals corrected as noted just above. In the region, at least, the normalized residual distribution is clearly energy-dependent. The normalized (pseudo-)residuals of the unfitted data samples displayed,28 namely those from [42, 66] in the region and from [63, 67] in the region, likewise corrected for the normalization uncertainty, are, instead, satisfactory,29 despite being unfitted. The fit process allows us to compute the (global) distance of the NSK samples to the (BESIII) fit function and returns , a reasonable value for unfitted data.

Fig. 3.

Normalized residuals of fits to the BESIII data in isolation under three different configurations: no energy shift (top panels), one global energy shift (middle panels) and two energy shifts (bottom panels). The normalized residuals are defined as , where – see the text for the definitions. The partial ’s are displayed. Also shown, the NSK ’s distance of the CMD2 and SND data to the best fit solutions derived from fitting BESIII data in isolation in each configuration

However, the behavior of the BESIII residuals may indicate a mismatch between the and pole positions in the BESIII sample compared to the other () data samples involved in the (global) fit; indeed, the narrow and signals are already present in the and channels, and therefore, as when dealing with the CMD3 and BaBar dikaon samples in [19], a mass recalibration (shift) could be necessary to avoid mismatches with the pole positions for and in the other data samples. We thus have refitted the BESIII data, by allowing for such a mass shift to recalibrate the BESIII energies and match our reference energy scale.30 So, we define:

and let vary within the fit procedure. The fit returns keV with , and thus the (noticeable) gain of 29 units should be attributed to only allowing for a nonzero . The corresponding normalized residuals, displayed in the middle row of Fig. 3, are clearly much improved, whereas the distance of the NSK 3 data sample to the BESIII fit function stays the same.

Owing to the sharp improvement produced by this mass shift, it was tempting to check whether the energy (re-)calibration could be somewhat different at the and the masses. For this purpose, it is appropriate to redefine the fitting algorithm by stating:

| 53 |

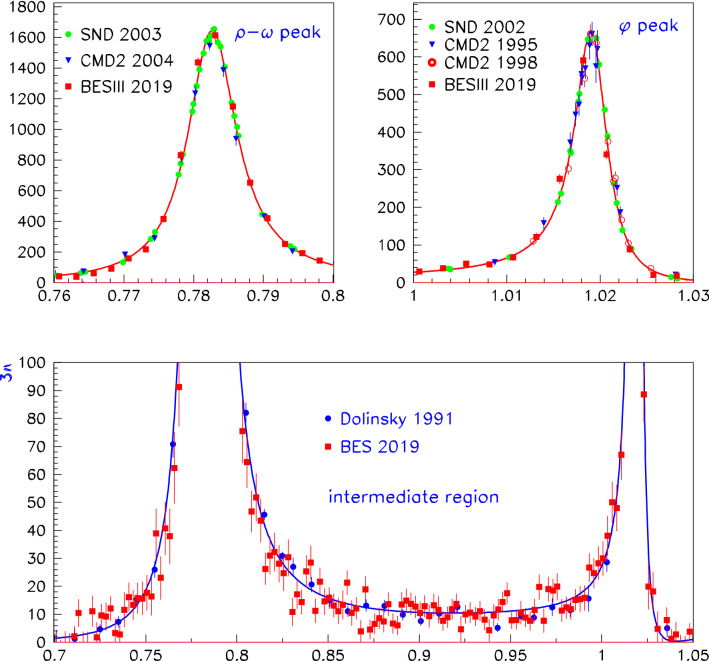

where should be chosen appropriately, i.e. significantly outside the and peak energy intervals. As obvious from the bottom panel of Fig. 5, the 3 cross section in the intermediate energy region is almost flat and indicates that the choice for is far from critical; we chose GeV.

Fig. 5.

The global fit with the spectra, corrected for their normalization uncertainty; only statistical errors are shown. The top panels display the data and fit in the and mass intervals; the bottom panel focuses on the intermediate energy region. The energy recalibration has been applied to the BESIII data

The corresponding global fit has been performed and returns , with an additional gain of 18 units, to be added to the previous 29-unit gain. The recalibration constants versus are:

After this recalibration has been applied, the BESIII normalized residuals, shown in the panels of the bottom row in Fig. 3, are observed to be flat, as well as their NSK partners also displayed.

We should note that is in striking correspondence with the central value for the energy shift reported by BESIII [24] compared to their Monte Carlo ( MeV) and is found highly significant (about ). is also consistent with this number but quite significantly different from . Actually, comparing the three rightmost panels in Fig. 3, one observes that the main gain of decorrelating the energy calibration at the and peaks widely improves the former energy region; the latter looks almost insensitive, as reflected by the fact that the nonzero is only a effect.

So, once two energy recalibrations have been performed, the description of the BESIII sample is quite satisfactory and, fitted with the other annihilation channels, the probability is comfortable (91.6%).

At first sight, the differing energy shifts just reported may look surprising as, for ISR spectra, the energy calibration is very precisely fixed by the energy at which the accelerator is running at meson factories. However, such energy shifts could be related to unaccounted effects of the secondary photon emission expected to affect the resonances showing up at lower energies. In the case of the BESIII spectrum, this concerns the and regions, where photon radiation effects are enhanced by the resonances, causing shifts between the physical resonance parameters and their observed partners.31 This topic is specifically addressed in Appendix D, where it is shown – and illustrated by Table 14 therein – that the expected shifts produced by secondary ISR photons are in striking correspondence with the fitted and .

Table 14.

The energy shifts in keV of the resonance locations by local ISR photon emission at . We adopted PDG resonance parameter values (in MeV). The values for are obtained in a global fit involving all 3 data samples (BESIII+NSK)

| 782.65 | 8.49 | −403 | −486 ± 72 | |

| 1019.46 | 4.26 | −213 | −135 ± 59 |

Exploratory global fits including the BESIII 3 sample

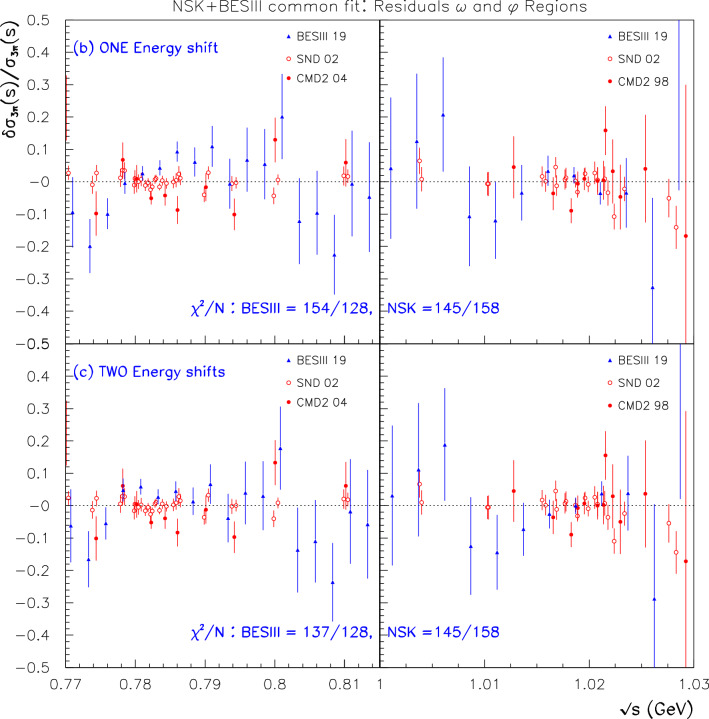

Having proved that the BESIII 3 data sample suitably fits the global framework, we perform the analysis by merging the BESIII and the parent CMD2 and SND data samples within a common fit procedure. For completeness, we have first performed a global fit allowing for a single energy calibration constant. The fit returns and 84.7 % probability. The values for BESIII (154/128) and NSK (145/158) are also reasonable; however, the normalized residuals for BESIII shown in the top panels of Fig. 4 – especially the leftmost panel – still exhibit a structured behavior.

Fig. 4.

Normalized residuals of fits to the BESIII, CMD2 and SND data under two different configurations: top panels correspond to a (global) fit with only one energy shift for the BESIII spectrum; the bottom ones are derived allowing different and . The partial are displayed for the BESIII sample on the one hand, and for the CMD2 and SND ones (NSK) on the other hand

Therefore, we have allowed for two independent energy shifts and within the iterative fit procedure. Convergence is reached with and 91.2% probability. The value for BESIII (137/128) is improved by 17 units, whereas it is unchanged for NSK (147/158); thus the improvement of the total only proceeds from the 17-unit reduction of the BESIII partial . The bottom panels in Fig. 4 are indeed observed flat in the and regions (this last distribution is still less sensitive to the fit quality improvement). The energy recalibration constants of the BESIII data with regard to the NSK energy scale are:

in fair accord with those derived in the global fit performed discarding the NSK 3 data. Compared to its fit in isolation, the BESIII data is degraded by units, while (see Table 4 third data column) the NSK data is degraded by units compared to the fit performed discarding the BESIII data sample, the rest being unchanged. Regarding the average per data point, the degradation is of the order 0.1 -unit for both the NSK and BESIII samples, a quite insignificant change. So, one can conclude that the full set of consistent data samples can welcome the BESIII sample [24], once the energy shifts and are applied.

Table 4.

Global fit properties of the fits ; second line in the table title indicates the running conditions regarding the data samples submitted to fit or the running of the BS or RS variants when . The number of data points involved is given between parentheses in the first column. The last lines display the global and probability of each fit

| BS () | () | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Excl. | Incl. | BS | RS | |

| NSK (127) | 136 | 134 | 138 | 136 |

| KLOE (135) | 141 | 146 | 139 | 139 |

| BESIII (60) | 48 | 47 | 49 | 48 |

| Spacelike (59) | 62 | 67 | 62 | 60 |

| (ABC) (84) | 93 | 82 | 80 | |

| (112) | 89 | 88 | 88 | 87 |

| (182) | 120 | 120 | 124 | 124 |

| NSK (158) | 142 | 146 | 147 | 147 |

| BESIII (128) | 138 | 138 | 137 | 137 |

| NSK (92) | 103 | 104 | 103 | 104 |

| NSK (49) | 41 | 42 | 39 | 39 |

| BaBar (27) | 41 | 42 | 41 | 41 |

| Spacelike (25) | 18 | 19 | 17 | 18 |

| Decays (8) | 5 | 4 | 9 | 9 |

| 1179/1280 | 1285/1365 | 1269/1365 | 1262/1365 | |

| Probability | 93.3% | 83.1 % | 90.0 % | 91.5 % |

Figure 5 displays the fit function and data in the 3 channel. All data are normalization-corrected as emphasized above, and additionally, the energy shifts induced by having different and calibration constants are applied to the BESIII data sample; one should also note the nice matching of the ND and BESIII data in the intermediate region. Additional fit details of this new global fit are given in the third data column of Table 4.

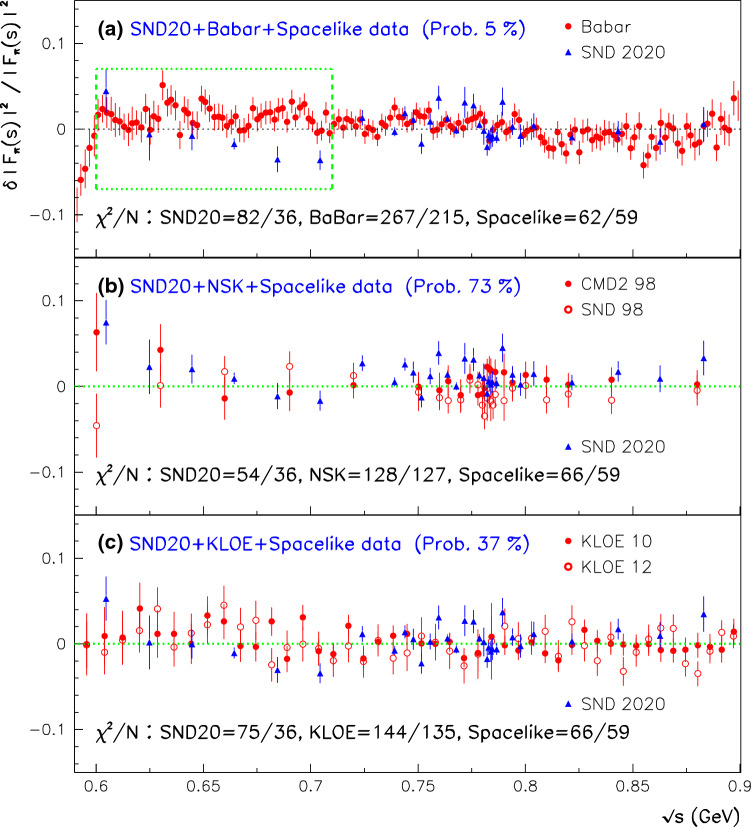

Revisiting the annihilation channel

A fair understanding of the dipion annihilation channel, which provides by far the largest contribution () to the muon HVP, is an important issue. Fortunately, the cross section is also the most important channel encompassed within the BHLS [14, 75] and [19] frameworks developed previously. All the existing dipion data samples were examined within the context of these two variants of the HLS model. As some of them exhibit strong tensions [14] with significant effects on the derived physics quantities, it looks worthwhile to revisit this issue when a new measurement arises, at least to check whether the consistency pattern previously favored deserves reexamination.

Besides the data samples formerly collected and gathered in [76], an important place should be devoted to the data from CMD-2 [43, 44, 77] and SND [45] collected in scan mode on the VEPP-2M collider at Novosibirsk; these CMD2 and SND samples are collectively referred to below as NSK. These were followed by higher statistics samples, namely the KLOE08 spectrum [28] collected at Dane and those collected by BaBar [78] at PEP-II, both using the initial-state radiation (ISR) method [79]. Slightly later, the KLOE Collaboration produced two more ISR data samples, KLOE10 [46] and KLOE12 [47], the latter being tightly related to KLOE08 (see Fig. 1 in [80]). In this reference, the KLOE-2 Collaboration has also published a dipion spectrum derived by combining the KLOE08, KLOE10 and KLOE12 spectra; this combined spectrum is referred to below as KLOE85, thus named according to its number of data points.

Two more data samples, also collected in the ISR mode, were appended to this list by BESIII [26] – with recently improved statistical errors [27] – and a CLEO-c group [48]. Finally, the SND collaboration has just published a data sample [25] collected in scan mode on the new VEPP-2000 facility at Novosibirsk; this spectrum, seemingly still preliminary, is referred to below as SND20. Another high statistics data sample, also collected in scan mode, is expected from the CMD3 Collaboration [81].

Important tension between some of these samples – namely KLOE08 and BaBar – and all others have already been identified [2, 75]; the occurrence of the new data sample from SND (and its comparison with NSK, KLOE and BaBar [25]) allows us to reexamine this consistency issue and provides the opportunity to remind the reader how it is dealt with within global frameworks.

The sample analysis method: a brief reminder

The broken HLS modelings previously developed, especially as well as its present extension, aim at providing frameworks which encompass a large part of the low-energy physics, the realm of the non-perturbative regime of QCD, and extend up to the mass region; they have rendered possible fair simultaneous accounts of the six major annihilation channels (, , , , ) up to 1.05 GeV/c; slightly modified (), this framework also now provides a satisfactory understanding of the A, B and C dipion spectra from the decay of the lepton.

As already noted several times, the Lagrangians which substantiate the various broken HLS models emphasize a property expected from QCD: the different annihilation channels should be correlated via their common underlying QCD background; this is reflected within our effective Lagrangians by the fact that all their model parameters are simultaneously involved in the amplitudes for any of the accessible physics processes they encompass. A straightforward example is represented by g, the universal vector coupling, and this property is, more generally, exhibited by the expressions for the various amplitudes derived from within the various broken HLS Lagrangians.

Most of the Lagrangian parameters are not known ab initio and are derived from the data via a global fit involving all channels and, possibly, all available data samples. For this purpose, the provided data samples and associated information (data points, statistical errors, systematics, correlated or not) are supposed reasonably32 well estimated. With this at hand, one can construct a motivated global and derive the Lagrangian parameters through a minimization procedure like minuit.

Among the various kinds of uncertainties reported by the different experiments, special care should be devoted to the global normalization uncertainties – which can be energy-dependent, as already dealt with in Sect. 8.1. Actually, as for energy scale recalibrations (see also Sect. 8.1), it looks obvious that the most appropriate normalization of a given sample can only be determined by comparing with several other independent spectra covering the same physics channel. Even more, a global treatment of these provides the best normalization of each sample versus all the others by a kind of bootstrap mechanism.

Actually, a global fit, when possible, appears to be the best tool to determine the most appropriate normalization of each spectrum in accord with its reported uncertainties, including its normalization uncertainties; this is noted in detail in [19, 75] and above in Sect. 8. The goodness of the corresponding fit indicates the confidence one can devote to the normalization corrections.

The probability of the best fit reflects the quality of the experimental information and the relative consistency of the various data samples involved in the procedure within the model framework; we now have three significantly different HLS frameworks at hand which have been shown in [19] and just above to lead to a consistent picture.

Samples covering the channel: a few properties

Let us first consider the data samples already identified as not exhibiting significant tension among them within the frameworks, the previous one [19] or the present one; this defines a reference set of data samples, named . This covers the data samples already considered in Sect. 8 and all the existing data samples covering the and decay channels. Regarding the dikaon spectra, we refer the reader to our analysis in [19], where the tensions between the CMD3 spectra [71, 72] and the others from SND, BaBar and (corrected [19]) CMD2 led us to discard them from the analysis.33 As for dipion spectra, it was shown in Sect. 4 that the residual tension observed in the account for Belle compared to Aleph and Cleo can be absorbed. The reference set also includes the spacelike pion [54, 55] and kaon form factor spectra [82, 83] which are satisfactorily understood within the frameworks [19].

For the purpose of reexamining sample tensions, it seems appropriate to also include in , the pion form factor spectra collected by BESIII [26, 27] and Cleo-c [48]. Indeed, anticipating somewhat our fit results, it has been observed that, alone or together with either of the NSK, KLOE, BaBar samples, or with any combination of these, they get the same individual sample ’s, with fluctuations not exceeding 1.5 units for each of them. Fitting the sample set thus defined within the present framework returns and a 94% probability; in this fit, the BESIII and Cleo-c samples yield

One can consider the probability of the global fit (here 94%) as a faithful tag of mutual consistency of the (more than 50) samples included in which fairly fit the broken HLS framework.

We have made two kinds of global fits:

(i) Fits involving and each of NSK, KLOE34 and BaBar in turn; the diagonal in Table 3 reports the main results, namely the value returned for of resp. NSK, KLOE, BaBar and the probability of the global fit at the corresponding table entry.

(ii) Fits involving and the pairwise combinations (NSK, KLOE), (NSK, BaBar) and (KLOE, BaBar) in turn; the main fit results are reported in the non-diagonal entries of Table 3. In order to simplify the comparison of each of the NSK, KLOE, BaBar accounts provided by these “pairwise” fits, we have organized the non-diagonal entries in a specific manner: the entry (NSK, KLOE) provides and the global fit probability, whereas the entry (KLOE, NSK) provides and the (same) fit probability. The same rule applies mutatis mutandis to the other pairwise fits: (NSK, BaBar) and (KLOE, BaBar) together with .

Relying on Table 3, one clearly observes that the single-mode fits for NSK and KLOE are fairly good and in nice accord with the results returned by the corresponding pairwise fit. The pattern is somewhat different when BaBar is involved.

Table 3.

Properties of the global fits performed with the present upgraded model using the sample collection with one among the NSK, KLOE and BaBar samples and with pairs of these. The table is organized such that the first line displays the value for returned by fitting the three configurations ( + NSK), ( + NSK + KLOE), ( + NSK + BaBar); the corresponding fit probabilities are shown within square brackets. The second and third lines display the similar information for KLOE and BaBar. The number of data points in each of NSK, KLOE and BaBar is shown in the first column for convenience

| [Prob] | + NSK | + KLOE | + BaBar |

|---|---|---|---|

| NSK (127) | 129/127 [95.3%] | 142/127 [91.2%] | 138/127 [51.7%] |

| KLOE (135) | 136/135 [91.2%] | 132/135 [95.2%] | 148/135 [31.9%] |

| BaBar (270) | 328/270 [51.7%] | 354/270 [31.9%] | 326/270 [62.9%] |

In order to be complete, let us briefly summarize the fit results obtained within the present framework concerning KLOE08 and the KLOE85 sample derived by the KLOE2 Collaboration from their combination of the KLOE08, KLOE10 and KLOE12 spectra [80].

Regarding KLOE08: The global fit for + KLOE08 returns and a 74.7% global fit probability. With an average , one does not confidently consider the results derived from the fit to this combination compared to KLOE10 + KLOE12.

- Regarding KLOE85: The fit for + KLOE85 returns (global fit probability 94.7%) which clearly indicates that the KLOE08 issue is reasonably well dealt with in the KLOE85 combination [80]. We have also performed the pairwise fit + KLOE85 + NSK. In this case, we get:

with an 80.7% probability. This fit is obviously reasonable35 but less satisfactory than + NSK + KLOE, as the tension between KLOE85 and NSK is large, much larger than when using +NSK + KLOE as displayed in Table 3.

The case for the 2020 SND dipion sample: fits in isolation

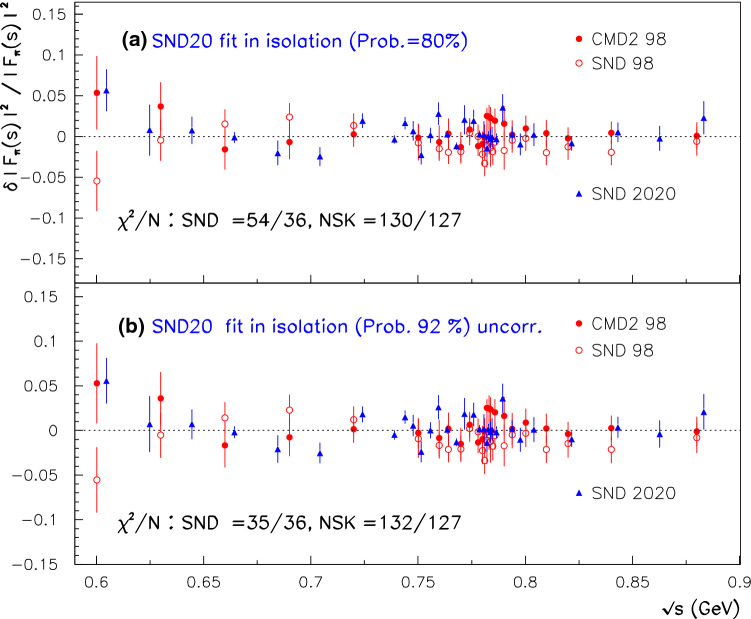

In order to analyze the new data sample recently provided by the SND Collaboration [25], the treatment of the reported systematic errors has been performed as emphasized above for the data from BESIII (see Sect. 8.1), as the systematics are expected to be fully point-to-point correlated.36 For the present analysis, we have first performed global fits37 where the single representative for the annihilation channel is SND20, the new SND data sample [25]; the spacelike pion form factor data [54, 55] have also been discarded from the fits in isolation. Figure 6 summarizes our results.

Fig. 6.

Fit of the SND20 data [25] in isolation within the framework. The top panel displays the results corresponding to a fit where SND20 systematics are fully point-to-point correlated, whereas the bottom panel is obtained by treating the SND20 systematics as fully uncorrelated. The NSK spectra are displayed but not fitted. See text for further explanation

The top panel in Fig. 6 indicates that, in single mode, the best fit returns a reasonable probability. However, this comes with a large average (to be compared with the diagonal in Table 3). Nevertheless, amazingly, the SND20 form factor derived from this global fit provides a fairly good account of the NSK (CMD2 and SND) data not submitted to the fit as one yields , much better than SND20 itself. The NSK (pseudo-)residual spectrum is consistent with flatness, and additionally, the ratio 130/127 indicates that there is no significant energy calibration mismatch between the NSK samples and SND20 – this may have shown up in the drop-off region.