Abstract

In plants, complete embryos can develop not only from the zygote, but also from somatic cells in tissue culture. How somatic cells undergo the change in fate to become embryogenic is largely unknown. Proteins, secreted into the culture medium such as endochitinases and arabinogalactan proteins (AGPs) are required for somatic embryogenesis. Here we show that carrot (Daucus carota) AGPs can contain glucosamine and N-acetyl-d-glucosaminyl and are sensitive to endochitinase cleavage. To determine the relevance of this observation for embryogenesis, an assay was developed based on the enzymatic removal of the cell wall from cultured cells. The resulting protoplasts had a reduced capacity for somatic embryogenesis, which could be partially restored by adding endochitinases to the protoplasts. AGPs from culture medium or from immature seeds could fully restore or even increase embryogenesis. AGPs pretreated with chitinases were more active than untreated molecules and required an intact carbohydrate constituent for activity. AGPs were only capable of promoting embryogenesis from protoplasts in a short period preceding cell wall reformation. Apart from the increase in embryogenesis, AGPs can reinitiate cell division in a subpopulation of otherwise non-dividing protoplasts. These results show that chitinase-modified AGPs are extracellular matrix molecules able to control or maintain plant cell fate.

Zygotic plant embryos pass through characteristic globular-, heart-, and torpedo-shaped stages before being desiccated in the mature seed. Somatic embryos pass through the same stages, but lack a desiccation phase and develop directly into plantlets. The carrot (Daucus carota) cell line ts11 is a temperature-sensitive variant in which somatic embryogenesis is arrested in the globular stage at non-permissive temperatures (Lo Schiavo et al., 1990). The phenotype of ts11 is pleiotropic and may result from a secretory defect (Baldan et al., 1997). It is remarkable that the addition of a carrot class IV endochitinase (designated EP3) allows further development of the embryos into plantlets (De Jong et al., 1992; Kragh et al., 1996). Endochitinases (1, 4-N-acetyl-β-d-glucosaminide glycanhydrolase, EC 3.2.1.14) hydrolyze β (1–4) linkages between at least three adjacent N-acetyl-d-glucosaminyl (GlcNAc) residues in chitin polymers (Molano et al., 1979; Usui et al., 1990). Endochitinases also hydrolyze β (1–4) linkages in partially deacetylated chitin (chitosan) and show variable efficiency in hydrolyzing chitin oligomers (Brunner et al., 1998). Plant cell walls are devoid of chitin or chitosan polymers, suggesting that plants contain other, uncharacterized targets for endochitinase activity.

AGPs are proteoglycans that can occur attached to membranes or in cell walls. In tissue cultures AGPs are secreted into the culture medium from which they can be selectively precipitated with 1,3,5-tri-(p-glycosyloxyphenylazo)-2,4,6-trihydroxybenzenes or Yariv reagent (Kreuger and Van Holst, 1993). Applying Yariv reagent to suspension cultures of rose cells inhibited culture growth due to suppression of cell division. After transfer to medium without Yariv reagent, cell division and culture growth were restored (Serpe and Nothnagel, 1994). Arabidopsis roots grown in the presence of Yariv reagent were found to have only one-third of the length of roots grown without this compound. The reduction of length resulted from cells in the elongation zone that were found to be bulbous rather than elongated (Willats and Knox, 1996). These experiments show that cell expansion can be perturbed by the addition of Yariv reagent.

A role for AGPs in plant development was initially proposed based upon their striking temporal and spatial localization patterns as visualized by the use of monoclonal antibodies (Knox et al., 1989, 1991). Direct addition of mature carrot seed AGPs to a weakly embryogenic cell line caused re-initiation of embryogenic cell formation (Kreuger and Van Holst, 1993). This resulted in the presence of clusters of small cytoplasm-rich rapidly dividing cells, in line with the reverse effect reported for the addition of Yariv reagent to rose cells (Serpe and Nothnagel, 1994). AGPs that contained an epitope recognized by the monoclonal antibody JIM8 were isolated from carrot cell-conditioned medium (McCabe et al., 1997). These JIM8 AGPs were added to a cell population unable to form somatic embryos and devoid of the JIM8 cell wall-bound epitope. This treatment restored the formation of somatic embryos from these cells. Therefore, a role for the JIM8 epitope containing AGPs in cell-to-cell communication during somatic embryogenesis was proposed.

AGPs consist of a small protein backbone contributing less then 10% of the mass of the AGP molecule. More than 90% of the AGP consists of carbohydrate with arabinosyl and galactosyl residues as the major sugar constituents (Nothnagel, 1997). In AGPs the polysaccharides are O-linked to the protein core and have highly complex side chains with different terminal residues. Individual monosaccharides in AGPs can be linked in different ways (Mollard and Joseleau, 1994), further increasing the structural complexity of the molecule. The presence of a small amount of glucosamine (GlcN) in AGPs was previously noted by van Holst et al. (1981). Later, it was found that certain AGPs contain a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) membrane anchor attached to the carboxy terminus of the protein backbone in which a single GlcN residue was detected (Youl et al., 1998; Svetek et al., 1999). However, the occurrence of oligomers of GlcNAc or GlcN has not previously been reported (Van Holst et al., 1981; Komalavilas et al., 1991; Baldwin et al., 1993; Mollard and Joseleau, 1994; Serpe and Nothnagel, 1994, 1996; Smallwood et al., 1996). However, based on these observations and the notable absence of GlcNAc or GlcN in all other wall carbohydrates, it appears that AGPs are one of the few plant cell wall molecules that may contain GlcNAc or GlcN in a form that could be a target for endochitinase activity. Our results suggest that AGPs from developing seeds and embryogenic suspension cultures indeed contain GlcNAc and GlcN residues. In addition, we show that these AGPs indeed contain cleavage sites for endochitinases and that these sites may have biological significance in somatic embryogenesis. We also demonstrate that EP3 endochitinases increase the formation of embryogenic cell clusters and somatic embryos from wild-type carrot protoplasts. Thus, the effect of endochitinases is not restricted to the ts11 variant (De Jong et al., 1993) and may exert its effect through hydrolytic activity on AGPs.

RESULTS

AGPs from Embryogenic Cell Lines Contain GlcN and GlcNAc

Carrot suspension cells in basal medium with 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) were labeled with 14C-GlcNAc). After 1 week, 20% of the total radioactivity could be recovered from the medium by precipitation with Yariv, suggesting incorporation into AGPs. Although about 70% of the label was retained in the cells, less than 2% was found in the insoluble cell wall fraction (data not shown). Because Yariv precipitation can result in coprecipitation of pectins, the pectin-specific monoclonal antibodies JIM5 and JIM7 were used to determine the possible occurrence of pectins in labeled and unlabeled AGP preparations obtained from suspension cell cultures. Immunodetection of pectin epitopes was performed before and after treatment with pectinase. Dot-blot analysis showed that after pectinase treatment, no pectin epitopes could be detected anymore. AGP-specific epitopes that are recognized by the monoclonal antibodies JIM8, MAC207, and MAC254 remained unaltered upon reprecipitation of the AGPs after pectinase treatment (data not shown). Over 80% of the radioactivity originally present in the AGPs was retained in the re-isolated pectin-free AGP fraction, indicating that the radioactivity was incorporated in the AGPs secreted into the medium. It cannot be excluded that some cleavage of AGPs occurred during the pectinase incubation. However, the resulting AGP preparations eluted as a series of defined peaks after high performance anion-exchange chromatography with pulsed amperometric detection (HPAE-PAD) were fully active in the somatic embryogenesis bioassay, and therefore, all AGPs as used in this study were treated with pectinase before use.

Because GlcNAc occurs in extracellular glycoproteins with N-linked carbohydrates, it was of importance to verify the absence of such labeled proteins from the AGP preparations. Electrophoresis of AGPs before and after pectinase treatment, followed by silver staining of polyacrylamide gels, did not reveal any contaminating proteins in the AGP fraction (data not shown).

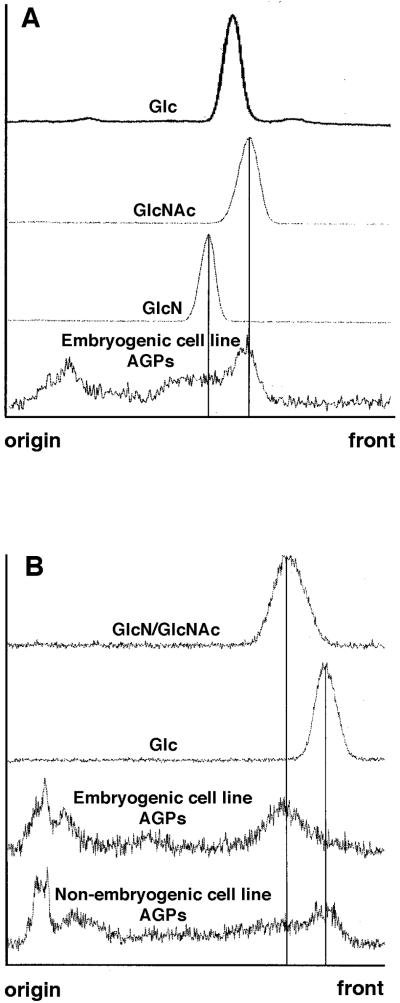

To determine whether 14C-label in the newly formed AGPs occurred in GlcN and in GlcNAc, labeled AGPs were incubated with 2 m trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) for 45 min at 100°C or alternatively for 60 min at 120°C. AGP degradation was monitored by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) followed by autoradiography and densitometric scanning of the autoradiographs (Fig. 1). The AGP sample incubated at 100°C for 45 min contained labeled compounds migrating to a position coinciding with GlcNAc. Label was also found at positions corresponding to GlcN and Glc. However, under these conditions AGP degradation was not complete (Fig. 1A). After incubation of AGPs at 120°C for 60 min, most of the label was found at the position of GlcN. Under these conditions all GlcNAc is deacetylated to GlcN. AGPs from a nonembryogenic cell line contained less aminated sugars and instead had more label converted into monosaccharides such as Glc (Fig. 1B). Because other major components of AGPs such as Ara and Gal have the same mobility as Glc on TLC, the possibility remains that deacetylation, deamination, and interconversion into other hexoses had occurred.

Figure 1.

Optical density scans of autoradiograms of TLCs. The scans represent the mobility of the TFA-degraded AGPs of an embryogenic and a nonembryogenic cell line labeled with 10−7 M 14C]GlcNAc, compared with the mobility of d-[1-14C]labeled Glc, GlcN, and GlcNAc references. A, AGPs and references degraded by means of incubation in 2 m TFA at 100°C for 45 min. B, AGPs and references degraded by means of incubation in 2 m TFA at 120°C for 60 min.

To determine which aminated and acetylated hexoses are present in AGPs, unlabeled AGPs were isolated from embryogenic suspension cultures by Yariv precipitation, and were hydrolyzed, acetylated, and subsequently analyzed by gas-liquid chromatography (GLC) and by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS). The following molar percentages of neutral sugars were found: Ara, 30.4%; Gal, 59.6%; rhamnose, 6.0%; Glc, 1.6%; Xyl, 1.3%; Man, 0.9%, and GlcN, 0.2%. The presence of GlcN was confirmed by GLC and GC-MS data. The mass spectrum of the compound in the AGP hydrolysate that co-eluted with a standard of GlcNAc precisely matched the spectrum of GlcN having mass signals at 84, 102, 144, and 318 m/z (Fox et al., 1989). No galactosamine or mannosamine were found in the AGP hydrolysate. Thus, we have demonstrated unambiguously the presence of GlcN as the only aminated sugar present in AGPs from embryogenic carrot suspension cultures. Therefore, the aminated and acetylated sugar that was found by TLC analysis can only have been GlcNAc.

AGPs from Immature Carrot Seeds Contain a Cleavage Site for Plant Endochitinases

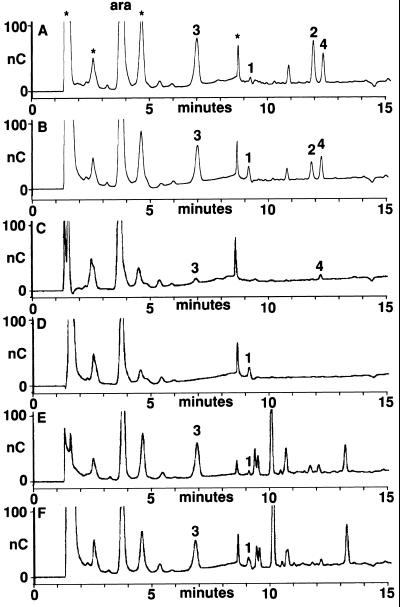

After having shown that GlcN and GlcNAc occur in AGPs, medium AGPs or AGPs from immature carrot seeds were incubated with endochitinase. However, after HPAE-PAD chromatography of these AGPs, no changes in elution profile were observed when compared with untreated preparations. It is apparent that no endochitinase cleavage product was produced in sufficient quantity to be detected by HPAE-PAD (data not shown). Immature seed AGPs were then incubated with a mixture of pure endogalactosidase, endoarabinofuranosidase, and exoarabinofuranosidase of fungal origin. This resulted in a limited number of discrete oligosaccharides resolved by HPAE-PAD (Fig. 2A). The peaks visible in Figure 2A with retention times of 1 min 30 s, 2 min 40 s, 4 min 30 s, and 8 min 40 s (marked by asterisks in Fig. 2A) were observed also in AGP preparations that were treated with pectinase only. These peaks may thus represent oligosaccharides present in the starting material or minor AGP species. The peak with a retention time of 3 min 50 s represents free Ara. Upon inclusion of endochitinases in the incubation mixture, a subtle shift in the pattern of oligosaccharides 1, 2, 3, and 4 occurred. There appeared to be an increase in an oligosaccharide numbered 1 (Fig. 2B, retention time of 9 min 10 s), a decrease in an oligosaccharide numbered 2 (retention time of 11 min 50 s), and a slight decrease in two other oligosaccharides numbered 3 and 4 (retention times of 7 min and 12 min 20 s, respectively). Oligosaccharide 1 did not result from the added endochitinase, endogalactosidase, endo-, and exoarabinofuranosidase preparations, since these only showed a single peak with a retention time of 1 min 30 s after HPAE-PAD, whereas incubation of young flower AGP preparations failed to show oligosaccharides at the position of peak 1 (A.J. van Hengel and S.C. de Vries, unpublished data). In interpreting the relatively small changes in these patterns after endochitinase incubation, it must be taken into account that the AGPs used for analysis are isolated from living plant material and no control was possible over hydrolytic degradation prior to isolation. Upon isolation of AGPs from immature seeds between 4 and 21 d after pollination (DAP) this became evident in the form of an increase in susceptibility for endochitinase activity of oligosaccharide 2 (A.J. van Hengel and S.C. de Vries, unpublished data) with developmental time, suggesting a change in composition or a higher level of preincubation with seed hydrolases. Incubation of AGPs with exoarabinofuranosidase only (Fig. 2C) indicates that removal of terminal arabinosyl residues generates the expected peak of free Ara, but unexpectedly, also the two oligosaccharides marked 3 and 4. Both were found to disappear after incubation with a mixture of exoarabinofuranosidase and the endochitinase (Fig. 2D), whereas oligosaccharide 1 appeared. Oligosaccharides 3 appears much more prominently after incubation of AGPs with endoarabinofuranosidase only (Fig. 2E), suggesting that it arose from residual endo-activity in the exofuranosidase preparation. Oligosaccharide 3 was found to be slightly reduced in area after incubation with a mixture of endoarabinofuranosidase and endochitinase (Fig. 2F), whereas oligosaccharide 1 appeared. Oligosaccharide 2 (Fig. 2A) only appeared after incubation with all three fungal hydrolases, suggesting that it is not the product of a single hydrolytic reaction.

Figure 2.

HPAE-PAD chromatography of AGP-derived oligosaccharides. HPAE-PAD chromatograms of AGPs that were isolated from immature seeds treated with pectinase and then incubated with AGP degrading hydrolases in the presence or absence of EP3 endochitinase. Oligosaccharides that change in relative amount upon incubation with EP3 endochitinase are numbered as 1 (retention time of 9 min 10 s), 2 (retention time of 11 min 50 s), 3 (retention time of 7 min), and 4 (retention time of 12 min 20 s). Peak height is expressed in nanocoulomb (nC). A, AGPs incubated with endogalactosidase, endo-, and exoarabinofuranosidase. B, AGPs incubated with endogalactosidase, endo-, and exoarabinofuranosidase in combination with EP3 endochitinase. C, AGPs incubated with exoarabinofuranosidase. D, AGPs incubated with exoarabinofuranosidase in combination with EP3 endochitinase. E, AGPs incubated with endoarabinofuranosidase. F, AGPs incubated with endoarabinofuranosidase in combination with EP3 endochitinase.

These results show that the product of endochitinase activity, oligosaccharide 1, can be generated from different oligosaccharides. They also show that arabinofuranosidase treatment of immature seed AGPs can make sufficient endochitinase cleavage sites available to be detectable by HPAE-PAD.

Immature Seed AGPs Promote Somati Embryogenesis and Can Be Activated by Chitinases

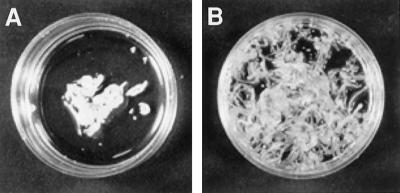

Next we asked whether endochitinase-mediated cleavage of AGPs serves a biological function. The first experiment was to include AGPs in the medium of suspension cultures with a low-to-moderate embryogenic potential. Compared with unsupplemented controls, no significant effect on somatic embryogenesis was observed after addition of carrot immature seed AGPs (Table IA). After preparation of protoplasts from these cells, the number of somatic embryos drops up to 20-fold (Table II). Adding immature seed AGPs at a concentration comparable with that normally found in the medium of suspension cells (1–3 μg/mL after 7 d of subculturing) resulted in a 30-fold increase in the number of somatic embryos formed (Table II; Fig. 3). Therefore, the loss of embryogenic potential due to cell wall removal is mainly caused by the concomitant removal of AGPs (Tables I and II). At an increased AGP concentration, protoplasts produced up to 5-fold more embryos than the cells from which they were derived. Secreted AGPs of an embryogenic culture were added to carrot protoplasts of the same cell line. This resulted in an increase of the number of somatic embryos that was fully comparable with the effect of immature seed AGPs. Thus, AGPs can also confer embryogenic potential to previously nonembryogenic cells, in line with previous observations (Kreuger and van Holst, 1993). It is surprising that the addition of immature seed AGPs preincubated with EP3 endochitinases reduced the number of embryos that developed to the level observed when EP3 chitinases were added alone. This suggested that cleavage of GlcNAc-containing oligosaccharide side chains by EP3 chitinase results in inactivation of AGPs. In contrast, when AGPs were preincubated with EP3 endochitinase and were then re-isolated by Yariv precipitation, the promotive effect of AGPs was not only completely restored, but was even increased by more than 50% when compared with non-chitinase-treated AGPs (Table II). These results showed that endochitinase treatment renders AGPs more effective in promoting somatic embryogenesis, and that an inhibiting compound, not precipitable by Yariv reagent, might be produced.

Table I.

The effect of AGPs on somatic embryogenesis from cells

| Compound | Concentration | Mean No. of Embryos per 10,000 Suspension Cells | sea | nb | P Values Compared with Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| μg mL−1 | |||||

| Control | – | 18 | 2.6 | 2 | – |

| AGPs | 3.0 | 22 | 2.6 | 2 | 0.811 |

Effect of pectinase-treated AGPs isolated from immature seeds at 21 DAP on the no. of somatic embryos formed from suspension cells. The effect of addition of AGPs is expressed as the no. of globular-, heart-, and torpedo-stage embryos obtained per 10,000 suspension cells. Statistical analysis was done by means of F tests on the average of the mean. The overall effect of a treatment was regarded as significantly different when calculated P values were ≤0.05. Bioassay conditions are described in “Materials and Methods.”

The se is included.

The no. of independent experiments (n) was obtained in two individual assays.

Table II.

The effect of chitinases and AGPs on somatic embryogenesis from protoplasts

| Compound and Treatment | Concentration | Mean No. of Embryos per 10,000 Protoplasts | sea | nb | P Values Compared with Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| μg mL−1 | |||||

| Control | – | 1 | 0.7 | 2 | |

| AGPs | 0.3 | 5 | 3.5 | 2 | 0.131 |

| 3.0 | 31 | 13 | 2 | 0.016 | |

| 15 | 42 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.000 | |

| 30 | >100 | ndc | 2 | nd | |

| AGPs from culture medium | 15 | 40 | – | 1 | – |

| EP3 | 0.2 | 8 | 3.8 | 4 | 0.020 |

| AGPs + EP3 | 15 + 0.2 | 6 | 1 | – | |

| AGPs + EP3/AGPs re-isolated | 15 + 0.2 | 68 | 2.5 | 8 | 0.000 (0.030)d |

Partial restoration of somatic embryogenesis from protoplasts at an optimal concentration of EP3 chitinase and full restoration by 21 DAP seed AGPs at physiological concentrations. Effect of EP3 endochitinase pre-treatment of immature seed AGPs with and without re-isolation of AGPs by Yariv precipitation. The effect of addition of AGPs is expressed as the no. of globular-, heart-, and torpedo-stage embryos obtained per 10,000 protoplasts. Statistical analysis was done by means of F tests on the average of the mean. The overall effect of a treatment was regarded as significantly different when calculated P values were ≤0.05. Enzyme treatment of AGPs and bioassay conditions are described in “Materials and Methods.” All AGP preparations were pretreated with pectinase.

The se is included.

The no. of independent experiments (n) was obtained in two individual assays.

nd, Not determined.

P value when compared to 15 μg mL−1 AGPs added without EP3 treatment is in parentheses.

Figure 3.

Restoration of somatic embryogenesis from protoplasts by seed AGPs. A, Callus and an occasional somatic embryo formed in unsupplemented control culture. B, Plantlets formed after addition of 3 μg mL−1 of immature 21 DAP seed AGPs, pretreated with pectinase.

In all assays described so far, AGPs were added shortly after protoplast preparation and before cell wall regeneration was complete. AGPs were not effective in promoting embryo formation when added 1 d after protoplast isolation (Table III). AGP epitopes rapidly reappear on the surface of protoplasts after enzymatic digestion of cell surface polysaccharides (Pennell et al., 1989), and within 24 h protoplasts have synthesized a new cell wall. Therefore, AGPs are only fully active before cell wall regeneration is complete. AGPs isolated from manually dissected endosperm of immature seeds were found to be highly active (Table III), demonstrating that AGPs that promote somatic embryogenesis are mainly found in the endosperm. AGPs isolated from gum arabic or from immature seeds at 11 DAP were not active, demonstrating that there is species and temporal specificity in the embryo-forming activity of AGPs. Barium hydroxide hydrolysis, which cleaves polypeptide linkages (Lamport and Miller, 1971) and releases oligosaccharides O-linked to hydroxy-Pro and free oligosaccharides derived from any linkages to other amino acids, did not reduce the embryo-forming effect of AGPs (Table III). This shows that the effect of AGPs on embryogenesis requires its intact carbohydrate, but not its intact polypeptide constituent. AGPs treated with EP3 chitinase gave an approximately 60-fold increase in embryogenesis, which was comparable with the increase reported in Table II. In contrast, treatment with the same mixture of hydrolases employed for the HPAE-PAD analysis (Fig. 2) rendered AGPs completely ineffective. Therefore, AGP side chains with intact arabinogalactan carbohydrate moieties are essential for the effect on somatic embryogenesis (Table III), whereas hydrolytic activation with endochitinases appears essential for full embryo-forming activity of the AGPs.

Table III.

The effect of AGPs and AGP-derived oligosaccharides on somatic embryogenesis

| Compound and Treatment | Fold Increase in Embryogenesis |

|---|---|

| Control | 1 |

| AGPs | 38 |

| AGPs added after 1 d | 1 |

| AGPs from endosperm | 153 |

| AGPs from gum arabic | 3 |

| AGPs 11 DAP | 4 |

| AGPs × EP3/AGPs re-isolated | 61 |

| AGPs × BaOH | 36 |

| AGPs × exoA + endoA + endoG | 2 |

AGPs were isolated from immature seeds at 21 DAP and were added immediately or 1 d after protoplast isolation. AGPs derived from carrot endosperm, gum arabic, or from immature seeds at 11 DAP were isolated and added to protoplasts. Effects of BaOH treatment of AGPs, endogalactosidase, endo-, and exoarabinofuranosidase (endoG, endoA, and exoA, respectively) treatment of AGPs were compared with activation of AGPs by EP3 endochitinase. The results in this table were obtained in duplicate assays, but in single experiments, and therefore did not allow statistical analysis by F tests. The results are expressed as the no. of somatic embryos formed in a dish containing 100,000 protoplasts with AGPs, divided by the no. of somatic embryos formed in control dishes without AGPs that accompanied each experiment. The no. of somatic embryos in the control dishes varied between seven and 11. In all experiments the final concentration of AGPs used was 15 μg mL−1. Enzyme treatment of AGPs and bioassay conditions are described in “Materials and Methods.” All AGP preparations were pretreated with pectinase.

Early Effects of Immature Seed AGPs on Protoplasts

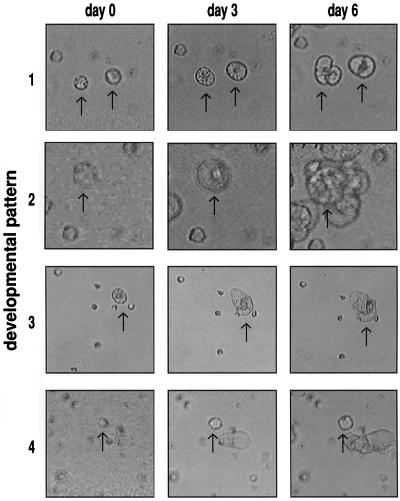

To determine whether protoplasts showed a morphologically recognizable effect after addition of AGPs we employed cell tracking of protoplast-derived cells. Cell tracking involves analysis of daily repeated video recordings made from the same area of a dish containing immobilized carrot protoplasts (Toonen and de Vries, 1997). When following the development of a population of protoplasts by cell tracking, four different possible developmental patterns can be distinguished, commencing from an initially fairly uniform population of protoplast-derived cells (F. Guzzo and S.C. de Vries, unpublished data). Protoplast-derived cells can divide without expanding to much more then their original size, resulting in small compact clusters; they can divide and simultaneously enlarge, resulting in loosely attached clusters of vacuolated cells; they can enlarge, but not divide, resulting in large vacuolated cells, or they can neither divide, nor enlarge and remain unchanged in morphology during the period of analysis. In Figure 4, examples of these four patterns are shown. Somatic embryos only derive from cells that follow pattern 1 (F. Guzzo and S.C. de Vries, unpublished data).

Figure 4.

Development of immobilized carrot protoplasts. Development of individual carrot protoplasts was analyzed by means of video cell tracking. After comparison of images as obtained after 0, 3, and 6 d, four patterns of development were identified: 1, cells that only divide and do not enlarge; 2, cells that enlarge and divide; 3, cells that only enlarge; and 4, cells that do not divide or enlarge. Arrows indicate cells representing the developmental pattern indicated.

In Table IV the results of the cell tracking experiments on protoplasts obtained from two embryogenic suspension cultures are summarized. Samples of protoplasts were immobilized and cultured with and without immature seed AGPs. The results are presented as a percentage of the total number of protoplasts that follow any of the four possible developmental patterns as shown in Figure 4. For each culture treatment more than 600 individual protoplasts were recorded. The particular pattern followed was determined from the video tapes at d 6 to ensure that all cells that could have responded had indeed done so. Without any addition about 5% of the protoplasts followed pattern 1 (division without elongation) and the same percentage of protoplasts was found to follow pattern 3 (elongation). Thirteen percent followed pattern 2 (division in elongated cells), whereas three-quarters of the protoplasts remained unchanged (pattern 4). Addition of AGPs resulted in a statistically significant (P = 0.04) decrease in cells following pattern 4, resulting in a redistribution of cells over the other three patterns of development. A subtle difference was noted in that after addition of AGPs more cells entered into pattern 1, suggesting that AGPs are more effective in triggering cells into a rapid cell division mode than they are in promoting cell elongation. The increase in the number of cells following pattern 1 after addition of AGPs was, however, not statistically significant (P = 0.06). The addition of 2,4-D had an effect comparable with that of AGPs, also decreasing the number of cells following pattern 4. These cells entered into either one of the other patterns of development with a slight preferential increase for cells that elongate only (pattern 3). Addition of 2,4-D and AGPs gave an additive effect on the decrease in the number of cells following pattern 4. In following the fate of the cells that had shifted to the other three patterns of development, an additive effect between 2,4-D and AGPs was observed for cells entering into the rapid division mode without elongation (pattern 1). No additive effect was seen for cells following the developmental patterns 2 or 3.

Table IV.

The effect of AGPs on the development of individual carrot protoplasts as analyzed by video cell tracking

| Compound | Developmental Patterns

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1, P values compared with control | 2, P values compared with control | 3, P values compared with control | 4, P values compared with control | |||||

| No additions | 5.0 | – | 13.1 | – | 5.0 | – | 76.9 | – |

| AGPs | 10.6 | 0.06 | 15.8 | 0.14 | 8.8 | 0.11 | 64.8 | 0.04 |

| 2,4-D | 7.8 | 0.12 | 17.1 | 0.04 | 10.4 | 0.04 | 64.7 | 0.04 |

| 2,4-D + AGPs | 14.9 | 0.04a | 17.5 | 0.91a | 10.3 | 0.99a | 57.4 | 0.16a |

Development of protoplasts of embryogenic carrot cell lines. The protoplasts were placed into four different categories: 1, dividing protoplasts; 2, dividing and enlarging protoplasts; 3, enlarging protoplasts; and 4, protoplasts that do not divide nor enlarge. Protoplasts were cultured in the presence or absence of 2,4-D with or without AGPs isolated from immature 21 DAP carrot seeds. Protoplasts that follow either of the four developmental pathways are represented as a percentage of the total no. of analyzed protoplasts of one treatment. The overall effect of addition of 2,4-D or 21 DAP AGPs was assessed by means of F tests using the absolute nos. of embryos formed after addition of 2,4-D or AGPs, and the absolute no. of embryos formed in controls without any additions. All AGP preparations were pretreated with pectinase.

The overall effect of addition of AGPs in cultures containing 2,4-D was compared with control cultures containing solely 2,4-D. (P values less than 0.05 were regarded as indicative for significant differences).

We conclude that the biological effect of AGPs is to reactivate cells to enter into division and to a lesser extent to promote elongation. The resulting increase in cells that follow pattern 1 is, however, not statistically relevant. Because in a comparable population of cells AGPs increase embryogenesis over 25-fold (Tables I–III), the primary effect of AGPs is seen in embryogenesis and not in cell division or cell elongation.

DISCUSSION

Several questions remained after the initial finding that plant endochitinases were able to rescue somatic embryogenesis in a carrot line unable to complete embryo development (de Jong et al., 1992). The first and most important of these was to identify a plant-derived substrate for these enzymes. Staehelin et al. (1994) and Goormachtig et al. (1998) showed that plant chitinases were able to cut and inactivate bacterial lipochitooligosaccharides (LCOs), suggesting a role for chitinases in controlling the level of chitin-based signaling molecules. Although LCOs from bacterial origin mimicked the effect of chitinases on ts11 embryogenesis (de Jong et al., 1993), biologically active LCO-like molecules have so far not been found in higher plants. Previous results showed that the gene encoding the 32-kD carrot chitinase was expressed in the endosperm during zygotic embryogenesis (van Hengel et al., 1998), suggesting that a potential substrate would be present in developing seeds. In conifer cultures an extracellular enzyme activity, possibly coinciding with chitinase activity, was reported to cause hydrolysis of AGPs (Domon et al., 2000).

Our evidence that AGPs are candidate molecules to function as a substrate for endochitinases consists of the presence of GlcNAc and GlcN in secreted AGPs from embryogenic cell cultures, the presence of chitinase cleavage sites in seed and secreted AGPs, and the observation that chitinase treatment enhances the embryo-promoting activity of AGPs.

A second related question was whether the activity of chitinases is restricted to embryogenesis in the carrot cell variant ts11. In this work we show that chitinases are also able to increase somatic embryogenesis from wild-type protoplasts. Taken together, our data suggest a general role for chitinases and AGPs in plant embryogenesis.

AGPs Contain GlcNAc, GlcN, and Cleavage Sites for Endochitinases

The occurrence of GlcNAc or GlcN in AGPs has not been reported before in studies on the total sugar composition of AGPs (Van Holst et al., 1981; Komalavilas et al., 1991; Baldwin et al., 1993; Mollard and Joseleau, 1994; Serpe and Nothnagel, 1994, 1996; Smallwood et al., 1996). The carrot AGPs characterized here only contained about 0.2% of aminated sugars in the form of GlcN and GlcNAc, in line with the value found by van Holst et al. (1981). It is well possible that GlcNAc has been overlooked in most analyses, especially in view of the tissue and stage specificity of AGP epitopes (Knox et al., 1989, 1991). Because a subset of secreted AGPs contain GPI anchors with a single GlcN residue (Youl et al., 1998), the possibility exists that our GC-MS analysis has detected such AGPs in carrot culture media. Secreted rose cell AGPs contain between two and six times more GlcN as expected, based on the presence of the GPI anchor alone. No preferential release of GlcN occurred after incubation with glycoamidase A, suggesting that the GlcN was not present as N-glycans in rose AGPs (Svetek et al., 1999). Several tobacco chitinases, including the class I type, are capable of degrading partially re-acetylated chitin (chitosan), chitin oligomers of at least three residues, but not oligomers of GlcN (Brunner et al., 1998). The carrot EP3 class IV endochitinase employed here is related to class I enzymes and is also able to use chitosan as substrate (van Hengel, 1998). Therefore, it is unlikely that GPI anchors themselves are the substrate for endochitinase activity. It is evident that the occurrence of endochitinase cleavage sites in AGPs is a relatively rare event, because only very few differences in AGP-derived oligosaccharides were observed after endochitinase treatment. Generating partially degraded AGPs has also proven to be a useful tool for controlled degradation in structural studies of AGPs (Gleeson and Clarke, 1979; Tsumuraya et al., 1984, 1990; Saulnier et al., 1992). The enzymes and the combinations that we have used imply that GlcNAc is present in side chains of AGPs (van Hengel, 1998). However, these studies do not provide enough information to allow a precise identification of the AGP oligosaccharides that contain an endochitinase cleavage site. In addition to EP3 endochitinases, β-galactosidase and α-arabinofuranosidase activity is present in the conditioned medium of carrot suspension cultures (Konno and Katoh, 1992; Konno et al., 1994). A potential problem, therefore, is that AGPs may always be partially processed prior to isolation and therefore variable in composition. In vivo, hydrolytic enzymes of fungal and plant origin have been shown to be capable of degrading AGPs, suggesting that a stepwise AGP degradation mechanism occurs by means of individual hydrolytic enzymes (Nothnagel, 1997).

AGPs and Cell Identity

The temporal and spatial expression of AGP epitopes present on the cell surface and the proposed functions of AGPs in plant development suggest that in plants the identity of cells or tissues might be reflected by the AGPs present in the cellular matrix (Nothnagel, 1997). If so, the production of AGPs that reflect cellular identity must be correlated to cell differentiation. This hypothesis is supported by the observation that MAC207 epitopes, present on a large number of AGPs, are lost from cells involved in sexual reproduction and are absent in early zygotic embryos where the MAC207 epitope reappears after the embryos reach the heart stage (Pennell et al., 1989). An almost inverse pattern was found using the JIM8 monoclonal antibody. In oil seed rape, AGPs containing JIM8 epitopes were localized in gametes, anthers, ovules, and in the early embryo (Pennell et al., 1991). Taken together, the presence of MAC207 and JIM8 epitopes demonstrates that the expression of certain AGP epitopes is tightly connected to flower and embryo development and suggests that AGPs might be involved in the regulation of cell differentiation.

The presence of JIM8 epitopes was shown to have a polar localization in the cell wall of individual carrot suspension cells (Pennell et al., 1992; McCabe et al., 1997). The function of this JIM8 reactive material is unknown. It was previously suggested that cells containing the JIM8 epitope represent an intermediary cell type in somatic embryogenesis (Pennell et al., 1992). However, the development of living cells decorated with the JIM8 antibody by cell tracking revealed that the JIM8 cell wall epitope does not coincide with the ability of single suspension cells to form somatic embryos (Toonen et al., 1996). The release of compounds containing the JIM8 epitope from JIM8-labeled cells was suggested to function as a soluble signal that may activate non-JIM8 decorated cells to enter into the embryogenic pathway. The removal of the cell population carrying JIM8 epitopes resulted in a decrease in the embryogenic potential in the remaining cell culture (McCabe et al., 1997). Addition of the JIM8 epitope containing soluble signals might then compensate for the lack of this cell population. Apart from a more structural role in ensuring a proper membrane-cell wall connection, AGPs have been proposed to function as signaling molecules (Bacic et al., 1988). We have shown here that AGPs can be activated after chitinase treatment, suggesting that entire AGPs themselves are signaling molecules rather than small chitinaceous molecules derived from them. The effects of AGPs on embryogenesis were observed at concentrations that did not exceed nanomolar ranges, which seems to be in line with a signaling function rather than a structural role. EP3 endochitinases alone can partially restore the embryogenic potential in wild-type suspension cell protoplasts. It is likely, but unproven, that this effect is mediated through endogenous AGPs.

Schultz et al. (1998) have outlined potential mechanisms for the involvement of GPI-membrane anchored AGPs in signal transduction pathways. It remains possible that the entire AGP molecule, as well as oligosaccharides derived from it, perform different signaling roles. Thus, depending on the environment and ambient presence of enzymes such as endochitinases, AGPs may give rise to a variety of molecules capable of redirecting fate and controlling proliferation of plant cells. This would be fully in line with our observations that AGPs can simultaneously reactivate non-dividing and nonexpanding cells and can form somatic embryos from dividing plant cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Material and Isolation of Chitinases and AGPs

Embryogenic carrot (Daucus carota L. cv Trophy) suspension cultures were initiated and maintained as described (De Vries et al., 1988). Nonembryogenic cultures arose from embryogenic ones after subculture for approximately 1 year. EP3 endochitinases were isolated as described (Kragh et al., 1996) or produced as single isozymes in the Baculovirus insect cell expression system. No difference was observed in catalytic activity between the plant and insect cell-produced enzymes. AGPs were isolated from carrot suspension cultures 7 d after subculturing or from immature carrot seeds (Novartis Seeds, Enkhuizen, The Netherlands) by precipitation with Yariv reagent as described (Kreuger and Van Holst, 1993). Pectin-free AGP fractions were obtained by incubating 1 mg of AGPs in 50 mm NaAc, pH 5.0, containing 10 units of pectinase (Sigma, St. Louis) for 16 h followed by a second AGP isolation. The AGP concentration was determined by the radial gel diffusion method (Van Holst and Clarke, 1985).

Labeling of Suspension Cultures and Degradation of Labeled AGP Fractions

Carrot suspension cells (2 mL packed cell volume) were cultured for 1 week in 50 mL of B5 medium containing 0.2 μm 2,4-D. The cells were washed with and transferred to B5 medium with or without 0.2 μm 2,4-D and were grown in the presence of [1-14C]GlcNAc. Medium samples were taken after 2, 3, 4, and 7 d.

Cell wall fractions were obtained using the method described by Brown and Fry (1993).

The degradation of the labeled AGP fractions was done by incubation with 2 m TFA for 45 min at 100°C or 60 min at 120°C. After degradation the samples were analyzed by TLC (n-butanol:acetic acid:water, 6:2:2) next to the reference compounds d-[1-14C] Glc, d-[1-14C]GlcN, and [1-14C]GlcNAc that had been subjected to the same degradation reactions.

Detection and quantification of label was done using a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA).

AGP Carbohydrate Composition Analysis

A solution of AGPs was hydrolyzed in 2 m TFA (1 h at 121°C) using inositol as internal standard. The released sugars were converted into their alditol acetates (Englyst et al., 1982) and were analyzed by GLC on an SPB-1701 capillary column (30 m × 0.32 mm, 0.25-μm film thickness, Supelco, Bellefonte, PA) in a GC8000 Top gas chromatograph. The temperature program was run from 80°C to 180°C at 20°C/min, 180°C to 250°C at 1.5°C/min, and at 250°C for 3 min.

Identification of the compounds was confirmed GC-MS using a SPB-1701 capillary column (30 m × 0.32 mm, 0.25-μm film thickness, Supelco) in a gas chromatograph (HP 6890, Hewlett-Packard, Palo Alto, CA) coupled to a mass-selective detector (HP 5973, Hewlett-Packard) and using an HP Chem Station (Hewlett-Packard). The temperature program was identical to the one used for GLC measurements.

Enzymatic Hydrolysis of AGPs and Chromatography

Samples of 80 μg of AGPs were incubated for 24 h in 10 mm MES [2-(N-morpholino)-ethanesulfonic acid], pH 5.5, supplemented with 80 to 200 ng of EP3 chitinases and/or with 0.050 units of exoarabinofuranosidase, 0.024 units of endoarabinofuranosidase, and 0.030 units of endogalactosidase, all three of which were produced by Aspergillus niger. Analysis of AGPs and enzymatically degraded AGPs was performed by HPAE-PAD, using the CarboPac PA-100 column (Dionex, Sunnyvale, CA). The flow rate was 1 mL/min and the eluent consisted of 10% (v/v) 0.5 m NaOH: water in combination with a linear salt gradient starting at t = 3 min with 0% NaAc and ending at t = 18 min with 80% (v/v) 0.5 m NaAc.

Bioassay

Protoplasts were obtained from suspension cultures 3 d after subculturing. The cells were collected and incubated overnight in 1% (w/v) macerozyme and 2% (w/v) cellulase (both from Yakult Biochemicals, Tokyo) in 50 mm citrate-Hac, pH 4.8, and 0.3 m mannitol. Protoplasts were sieved through a 50-μm nylon mesh and washed three times in 100 mm CaCl2 and 0.3 m mannitol. After 2 h the protoplasts were washed once more and transferred to B5 medium with 0.3 m mannitol to initiate somatic embryogenesis. After the formation of heart- and torpedo-stage embryos, the plant material was transferred to fresh B5 medium without mannitol for further embryo development into plantlets. Aliquots of 30 μg of AGPs and 400 ng of EP3 were added to 100,000 freshly isolated carrot protoplasts in 2 mL of B5 medium containing 0.3 m mannitol. Enzyme treatment of AGPs to be used in bioassays was performed by incubation of 100 μg of AGP and 200 ng of EP3 in 1 mL of 20 mm citrate buffer, pH 5.5, for 16 h, followed by a re-isolation of AGPs. In the controls the enzymes were replaced by water. Aliquots of 500 μg of AGPs were incubated in 1 mL of 0.1 m barium hydroxide for 6 h at 100°C. The hydrolysate was neutralized by adding 1 n H2SO4 until the pH was stable at 7.0. After a 15-min centrifugation at 12,000g the precipitated BaSO4 was discarded and the supernatant containing the hydrolyzed AGPs was used in the bioassays. Hydrolyzed AGPs were used in the bioassay in concentrations that were based on the amount of AGPs from which the hydrolysate was derived. Samples in which AGPs were omitted, but were otherwise treated the same way were added to protoplasts. In none of these controls were more somatic embryos observed than in unsupplemented controls.

Cell Tracking

Immobilization of protoplasts obtained from two different embryogenic cell lines and subsequent video cell tracking was performed as described before for single cells (Toonen and De Vries, 1997), with the difference that the medium used contained 0.3 m mannitol. 2,4-D was added to the phytagel top layer to give a final concentration of 2 μm. AGPs in 1 mL of B5 medium were poured on top of the phytagel layers to give a final concentration of 13 μg/mL. Statistical analysis was done by using the SAS System based upon a generalized linear model (Aitkin et al., 1991). The overall effect of treatment was assessed by means of F tests and significant differences were expressed with P values less than 0.05.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jaap Visser for purified Aspergillus glycosidases capable of degrading carrot AGPs, and Herman Spaink and André Wijfjes for use of the HPAE-PAD equipment and their technical assistance. Monoclonal antibodies recognizing pectin or AGP epitopes were kindly provided by Keith Roberts.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Netherlands Organisation for Research and the European Union Biotechnology Program (project no. BIO 4 CT 960689).

LITERATURE CITED

- Aitkin M, Anderson D, Francis B. Statistical Modelling in GLIM. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bacic A, Harris PJ, Stone BA. Structure and function of plant cell walls. In: Preiss J, editor. The Biochemistry of Plants: a Comprehensive Treatise. San Diego: Academic Press; 1988. pp. 297–371. [Google Scholar]

- Baldan B, Guzzo F, Filippini F, Gasparian M, LoSchiavo F, Vitale A, De Vries SC, Mariani P, Terzi M. The secretory nature of the lesion of carrot cell variant ts11, rescuable by endochitinase. Planta. 1997;203:381–389. doi: 10.1007/s004250050204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin TC, McCann MC, Roberts K. A novel hydroxyproline-deficient arabinogalactan protein secreted by suspension-cultured cells of Daucus carota: purification and partial characterization. Plant Physiol. 1993;103:115–123. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.1.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JA, Fry SC. Novel O-d-galacturonyl esters in the pectic polysaccharides of suspension-cultured plant cells. Plant Physiol. 1993;10:993–999. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.3.993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner F, Stintzi A, Fritig B, Legrand M. Substrate specificities of tobacco chitinases. Plant J. 1998;14:225–234. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong AJ, Cordewener J, Lo Schiavo F, Terzi M, Vandekerckhove J, Van Kammen A, De Vries SC. A carrot somatic embryo mutant is rescued by chitinase. Plant Cell. 1992;4:425–433. doi: 10.1105/tpc.4.4.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong AJ, Heidstra R, Spaink HP, Hartog MV, Meijer EA, Hendriks T, Lo Schiavo F, Terzi M, Bisseling T, Van Kammen A. Rhizobium lipooligosaccharides rescue a carrot somatic embryo mutant. Plant Cell. 1993;5:615–620. doi: 10.1105/tpc.5.6.615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries SC, Booij H, Meyerink P, Huisman G, Wilde HD, Thomas TL, Van Kammen A. Acquisition of embryogenic potential in carrot cell-suspension cultures. Planta. 1988;176:196–204. doi: 10.1007/BF00392445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domon J-M, Neutelings G, Roger D, David A, David H. A basic chitinase-like protein secreted by embryogenic tissues of Pinus caribaea acts on arabinogalactan proteins extracted from the same cell lines. J Plant Physiol. 2000;156:33–39. [Google Scholar]

- Englyst H, Wiggins H, Cummings J. Determination of the non-starch polysaccharides in plant foods by gas-liquid chromatography of constituent sugars as alditol acetates. Analyst. 1982;107:307–318. doi: 10.1039/an9820700307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox A, Morgan S, Gilbart J. Preparation of alditol acetates by gas chromatography and mass spectrometry. In: Bermann J, McGinnis G, editors. Analysis of Carbohydrates. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1989. pp. 87–117. [Google Scholar]

- Gleeson PA, Clarke AE. Structural studies on the mayor component Gladiolus style mucilage, an arabino-galactan-protein. Biochem J. 1979;181:607–621. doi: 10.1042/bj1810607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goormachtig S, Lievens S, van de Velde W, van Montagu M, Holsters M. Srchi13, a novel early nodulin from Sesbania rostrata, is related to acidic class III chitinases. Plant Cell. 1998;10:905–915. doi: 10.1105/tpc.10.6.905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knox JP, Linstead PJ, Peart J, Cooper C, Roberts K. Developmentally regulated epitopes of the cell surface arabinogalactan proteins and their relation to root tissue pattern formation. Plant J. 1991;1:317–326. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1991.t01-9-00999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knox PJ, Day S, Roberts K. A set of surface glycoproteins forms an early marker of cell position, but not cell type, in the root apical metistem of Daucus carota L. Development. 1989;106:47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Komalavilas P, Zhu J-K, Nothnagel EE. Arabino-galactan-proteins from the suspension culture medium and plasma membrane of rose cells. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:15956–15965. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konno H, Katoh K. An extracellular β-galactosidase secreted from cell suspension cultures of carrot: its purification and involvement in cell wall-polysaccharide hydrolysis. Physiol Plant. 1992;85:507–514. [Google Scholar]

- Konno H, Tanaka R, Katoh K. An extracellular a-L-arabinofuranosidase secreted from cell suspension cultures of carrot. Physiol Plant. 1994;91:454–460. [Google Scholar]

- Kragh KM, Hendriks T, De Jong AJ, Lo Schiavo F, Bucherna N, Hojrup P, Mikkelsen JD, De Vries SC. Characterization of chitinases able to rescue somatic embryos of the temperative-sensitive carrot variant ts11. Plant Mol Biol. 1996;31:631–645. doi: 10.1007/BF00042235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuger M, van Holst GJ. Arabinogalactan proteins are essential in somatic embryogenesis of Daucus carota L. Planta. 1993;189:243–248. [Google Scholar]

- Lamport D, Miller D. Hydroxyproline arabinosides in the plant kingdom. Plant Physiol. 1971;48:454–456. doi: 10.1104/pp.48.4.454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Schiavo F, Giuliano G, De Vries SC, Genga A, Bollini R, Pitto L, Cozzani F, Nuti-Ronchi V, Terzi M. A carrot cell variant temperature sensitive for somatic embryogenesis reveals a defect in the glycosylation of extracellular proteins. Mol Gen Genet. 1990;223:385–393. doi: 10.1007/BF00264444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe PF, Valentine TA, Forsberg LS, Pennell RI. Soluble signals from cells identified at the cell wall establish a developmental pathway in carrot. Plant Cell. 1997;9:2225–2241. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.12.2225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molano J, Polacheck I, Duran A, Cabib A. An endochitinase from wheat germ activity on nascent and preformed chitin. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:4901–4907. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollard A, Joseleau JP. Acacia senegal cells cultured in suspension secrete a hydroxyproline-deficient arabino-galactan-protein. Plant Physiol Biochem. 1994;32:703–709. [Google Scholar]

- Nothnagel EA. Proteoglycans and related components in plant cells. Int Rev Cytol. 1997;174:195–291. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)62118-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennell RI, Janniche L, Kjellbom P, Scofield GN, Peart JM, Roberts K. Developmental regulation of a plasma membrane arabinogalactan protein epitope in oilseed rape flowers. Plant Cell. 1991;3:1317–1326. doi: 10.1105/tpc.3.12.1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennell RI, Janniche L, Scofield GN, Booij H, De Vries SC, Roberts K. Identification of a transitional cell state in the developmental pathway to carrot somatic embryogenesis. J Cell Biol. 1992;119:1371–1380. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.5.1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennell RI, Knox JP, Scofield GN, Selvendran RR, Roberts K. A family of abundant plasma membrane-addociated glycoproteins related to the arabinogalactan proteins is unique to flowering plants. J Cell Biol. 1989;108:1967–1977. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.5.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saulnier L, Brillouet J-M, Moutounet M, Du Penhoat CH, Michon V. New investigations of the structure of grape arabinogalactan-protein. Carbohydr Res. 1992;224:219–235. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(92)84108-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz C, Gilson P, Oxley D, Youl J, Bacic A. GPI-anchors on arabinogalactan-proteins: implications for signalling in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 1998;3:426–431. [Google Scholar]

- Serpe MD, Nothnagel EA. Effects of Yariv phenylglycosides on Rosa cell suspensions: evidence for the involvement of arabinogalactan-proteins in cell proliferation. Planta. 1994;193:542–550. [Google Scholar]

- Serpe MD, Nothnagel EA. Heterogeneity of arabinogalactan-proteins on the plasma membrane of rose cells. Plant Physiol. 1996;112:1261–1271. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.3.1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smallwood M, Yates EA, Willats WGT, Martin H, Knox JP. Immunochemical comparison of membrane-associated and secreted arabinogalactan-proteins in rice and carrot. Planta. 1996;198:452–459. [Google Scholar]

- Staehelin C, Schultze M, Kondorosi E, Mellor RB, Boller T, Kondorosi A. Structural modifications in Rhizobium meliloti Nod factors influence their stability against hydrolysis by root chitinases. Plant J. 1994;5:319–330. [Google Scholar]

- Svetek J, Yadav MP, Nothnagel EA. Presence of a glycosylphosphatidylinositol lipid anchor on rose arabinogalactan proteins. J Biol Chem. 1999;27:14724–14733. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.21.14724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toonen MAJ, de Vries SC. Use of video cell tracking to identify embryogenic cultured cells. In: Lindsey K, editor. Plant Tissue Culture Manual. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1997. pp. 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Toonen MAJ, Schmidt EDL, Hendriks T, Verhoeven HA, van Kammen A, de Vries SC. Expression of the JIM8 cell wall epitope in carrot somatic embryogenesis. Planta. 1996;20:167–173. [Google Scholar]

- Tsumuraya Y, Hashimoto Y, Yamamoto S, Shibuya N. Structure of L-arabino-D-galactan-containing glycoproteins from radish leaves. Carbohydr Res. 1984;134:215–228. [Google Scholar]

- Tsumuraya Y, Mochizuki N, Hashimoto Y, Kovac P. Purification of an exo-β-(1→3)-D-galactanase of Irpex lacteus (Polyporus tulipiferae) and its action on arabino-galactan-proteins. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:7207–7215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usui T, Matsui H, Isobe K. Enzymic synthesis of useful chito-oligosaccharides utilizing transglycosylation by chitinolytic enzymes in a buffer containing ammonium sulfate. Carbohydr Res. 1990;203:65–77. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(90)80046-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hengel AJ. Chitinases and arabinogalactan proteins in somatic embryogenesis. PhD thesis. The Netherlands: Wageningen University; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- van Hengel AJ, Guzzo F, van Kammen A, de Vries SC. Expression pattern of the carrot EP3 endochitinase genes in suspension cultures and in developing seeds. Plant Physiol. 1998;117:43–53. doi: 10.1104/pp.117.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Holst G-J, Clarke AE. Quantification of arabinogalactan-protein in plant extracts by single radial gel diffusion. Anal Biochem. 1985;148:446–450. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(85)90251-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Holst G-J, Klis FM, De Wildt PJM, Hazenberg CAM, Buijs J, Stegwee D. Arabinogalactan protein from a crude cell organelle fraction of Phaseolus vulgaris L. Plant Physiol. 1981;68:910–913. doi: 10.1104/pp.68.4.910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willats WGT, Knox JP. A role for arabinogalactan-proteins in plant cell expansion: evidence from studies on the interaction of beta-glucosyl Yariv reagent with seedlings of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1996;9:919–925. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1996.9060919.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youl JJ, Bacic A, Oxley D. Arabinogalactan-proteins from Nicotiana alata and Pyrus communis contain glycosylphosphatidylinositol membrane anchors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:7921–7926. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.7921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]