Abstract

Electrical activity plays crucial roles in neural circuit formation and remodeling. During neocortical development, neurons are generated in the ventricular zone, migrate to their correct position, elongate dendrites and axons, and form synapses. In this review, we summarize the functions of ion channels and transporters in neocortical development. Next, we discuss links between neurological disorders caused by dysfunction of ion channels (channelopathies) and neocortical development. Finally, we introduce emerging optical techniques with potential applications in physiological studies of neocortical development and the pathophysiology of channelopathies.

Keywords: cerebral cortex, neurogenesis, neuronal migration, dendrite, axon, ion channel, transporter, channelopathy

Introduction

Precise formation of neocortical circuits is essential for brain function. The cerebral cortex consists of six layers. Its laminar structure is formed in an “inside-out” manner; layer 6 is formed first, followed by formation of upper layers above the lower layers. Neocortical excitatory neurons are produced from neural progenitor cells in the ventricular zone (VZ). During neurogenesis, intermediate progenitors are produced from radial glia. Intermediate progenitors then produce or differentiate into excitatory neurons (Hevner, 2006). The newly born neurons migrate toward the marginal zone (MZ).

During migration, neurons dynamically change their morphology. Neocortical excitatory neurons slowly move in the subventricular zone (SVZ) and the intermediate zone (IZ) with small processes in multiple directions (multipolar migration) (Tabata and Nakajima, 2003). Then, migrating neurons change their shape at the border between the IZ and the cortical plate (CP) to a bipolar shape with long leading processes and short trailing processes, and migrate along the radial axis toward the cortical surface (Nadarajah et al., 2003). Finally, neurons stop migration below the MZ, and elongate dendrites and axons (Tissir and Goffinet, 2003; Mizuno et al., 2007, 2014). The molecular mechanisms of neocortical development have been intensely studied (Tessier-Lavigne and Goodman, 1996; O’Leary and Nakagawa, 2002; Hevner, 2006; Molyneaux et al., 2007; Kawauchi and Hoshino, 2008; Kawauchi, 2012; Marín, 2012). As well as genetic programs, electrical activity and Ca2+ signaling are also crucial for these processes (Katz and Shatz, 1996; Spitzer, 2006). Recent reports showed that dysfunction of ion channels or transporters disrupts neocortical development by altering electrical properties and Ca2+ signaling and may be linked to neurological disorders (Kullmann, 2010; Schmunk and Gargus, 2013; Guglielmi et al., 2015; Heyes et al., 2015; Kahle et al., 2016). In this review, we summarize how ion channels and transporters regulate electrical properties and Ca2+ signaling during neocortical development, focusing on excitatory neurons. Next, we discuss possible links between abnormal electrical signaling caused by dysfunction of ion channels or transporters and neurological disorders. Finally, we discuss the potential application of emerging optical techniques to address remaining issues related to the physiological mechanisms of neocortical development and the pathophysiology of channelopathies in vivo.

Electrical Signaling During Neocortical Development

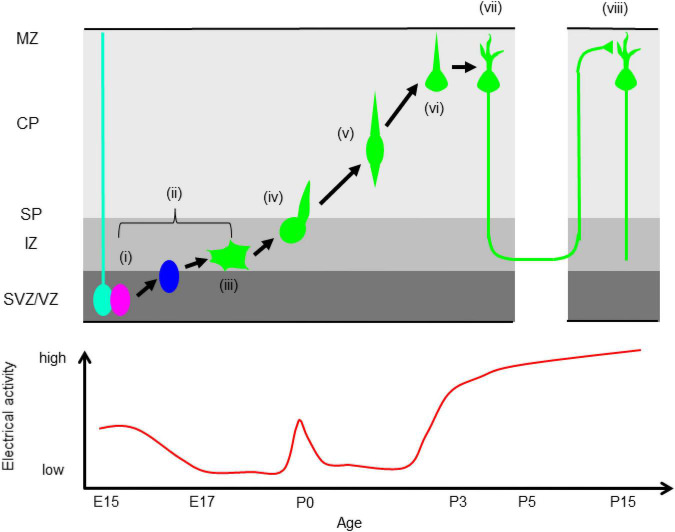

The roles of electrical signaling in axonal and dendritic growth and remodeling during late developmental stages have been intensely studied (Katz and Shatz, 1996; Price et al., 2006). Further studies revealed that electrical signaling is also crucial for early cortical development including neuronal proliferation, differentiation, and migration (Spitzer, 2006). These studies suggest that temporal regulation of electrical signals is critical for neocortical development (Figure 1). We discuss the details below.

FIGURE 1.

Correlation between electrical activity and neocortical development. (i) Proliferation, (ii) neuronal differentiation, (iii) multipolar migration (iv) multipolar-to-bipolar transition, (v) radial migration, (vi) termination of migration, (vii) dendrite and axonal elongation, (viii) synapse formation. VZ, ventricular zone, SVZ, subventricular zone, IZ, intermediate zone, SP, subplate, CP, cortical plate, MZ, marginal zone. The bottom panel shows temporal changes of electrical activity. Electrical activity is high during neurogenesis, low during migration except in the boundary between the IZ and SP, and is elevated again after neurons reach the MZ.

Neurogenesis, Differentiation, and Cell Fate Specification

Radial glial cells express various ion channels such as α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) and kainate type glutamate receptor, γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptor (GABAAR), voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (VGCCs), P2X receptor, and connexin 26 and 43, but not N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) type glutamate receptor (LoTurco et al., 1995; Bittman and LoTurco, 1999). The electrical properties of neural progenitors are distinct from those of mature neurons (Liu et al., 2010). Neural progenitors are non-spiking because of a small voltage-dependent Na+ current. Their resting potential is about –75 mV, and their input resistance is about 350 MΩ. Activation of AMPA and kainate receptor and GABAAR inhibits DNA synthesis by depolarizing membrane potentials (LoTurco et al., 1995). Further studies revealed that Ca2+ transients are required for the transition from G1 to S phase by releasing adenosine triphosphate (ATP) from progenitor cells through gap junction/hemichannels resulting in activation of P2X receptors. This indicates that temporal patterns of Ca2+ signaling are critical for cell cycle progression and neurogenesis (Weissman et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2010). A recent study demonstrated that activation of GABAAR promotes the transition from apical to basal progenitor cells by elevating of the intracellular Ca2+ concentration, suggesting that the excitatory action of GABAergic signals regulates differentiation of neural progenitors (Tochitani et al., 2021).

Interestingly, electrical activity also affects the cell fate of cortical excitatory neurons. A gain-of-function mutation of an L-type VGCC, CACNA1C (Cav1.2) reduces the fraction of Satb2-positive callosal projection neurons and increases the fraction of Ctip2-positive corticofugal projection neurons in layer 5 (Paşca et al., 2011). Recently, Vitali et al. (2018) showed that regulation of the resting potential is important for specification of upper layer neurons. Neural progenitors are more hyperpolarized at embryonic day 15 (E15) than at E14, and premature hyperpolarization of progenitors by expression of an inward rectifier K+ channel, KCNJ2 (Kir2.1), decreases the fraction of RORβ-positive layer 4 neurons and increases the fraction of Brn2-positive layer 2/3 neurons. There remain interesting questions about how electrical signals regulate transcription networks and how plastic production of neuronal populations is during cortical development.

Neuronal Migration

Newly born neurons have a more depolarized resting potential than neural progenitors (∼ –60 mV), drastically increased input resistance (∼ 3 GΩ), and less frequent spontaneous Ca2+ transients in the SVZ and IZ (Figure 1; Bando et al., 2014). Immature neurons express GABAAR, NMDAR, CACNA1C, and CACNA1D (Cav1.3). The expression levels of CACNA1C and CACNA1D are higher in the IZ and CP than in the VZ (Kamijo et al., 2018; Horigane et al., 2021). In the IZ, glutamate promotes migration into the CP via NMDAR (Behar et al., 1999). Around the border between the IZ and subplate (SP), migrating excitatory neurons show more frequent and larger Ca2+ transients than neurons in the lower IZ (Figure 1), because of activation of NMDAR by SP neurons. The increase of Ca2+ transients promotes the multipolar-to-bipolar transition of migrating upper layer neurons at E17 and E18 (Ohtaka-Maruyama et al., 2018; Horigane et al., 2021). During locomotion in the CP, the frequency of spontaneous Ca2+ transients decreases, and migrating neurons show more frequent Ca2+ transients after reaching the MZ (Figure 1; Bando et al., 2014, 2016). Suppression of spontaneous activity by blocking GABAAR results in acceleration of radial migration and invasion of neurons into the MZ (Behar et al., 2000; Heck et al., 2007; Furukawa et al., 2014). A tandem pore domain K+ channel, KCNK9 (K2P9.1) promotes migration by suppressing spontaneous Ca2+ transients (Bando et al., 2014). Nakagawa-Tamagawa et al. (2021) reported that a disease-associated mutation of CACNA1C causes migration arrest. Furthermore, the strong elevation of spontaneous activity during early developmental stages in the neocortex stops neuronal migration, and induces dendritic branch formation (Bando et al., 2016). These results show that spontaneous Ca2+ transients should be kept low during radial migration and that an increase of Ca2+ signaling acts as a stop signal in cortical excitatory neurons. Electrical signals induce elevation of intracellular Ca2+, which functions as a second messenger; it activates multiple Ca2+-dependent enzymes, followed by activation of downstream signaling cascades, and also regulates cytoskeletal dynamics and exocytosis. Taken together, these findings show that properly regulated Ca2+ signaling at each developmental stage is critical for neocortical formation (Manent and Represa, 2007; Zheng and Poo, 2007; Uhlén et al., 2015; Horigane et al., 2019; Medvedeva and Pierani, 2020).

The correlation between the intracellular Ca2+ level and migration speed differs among cell types. Komuro and Rakic (1996) and Kumada and Komuro (2004) showed that loss of spontaneous Ca2+ transients is a stop signal for cerebellar granule cell migration. Similar to cerebellar granule cells, neocortical inhibitory interneurons stop migration in the absence of spontaneous Ca2+ transients caused by excitatory-to-inhibitory switching of GABAergic signaling (Bortone and Polleux, 2009). Interestingly, migration of neocortical excitatory neurons is also regulated in a Ca2+-dependent manner, but with the opposite mechanism as described above. It remains unclear what underlies the difference in Ca2+-dependency between migration of cortical excitatory and cortical inhibitory interneurons/cerebellar granule cells.

Dendrite Formation, Axonal Projection, and Synapse Formation

Post-migratory neurons become electrically mature; expression of voltage-gated Na+ channels increases (peak Na+ current: ∼ –90 pA at P0, and ∼ –800 pA at P4), and neurons start firing action potentials (Picken Bahrey and Moody, 2003). Their input resistance is significantly reduced (0.6–1.6 GΩ at P4). Activity-dependent formation and remodeling of dendrites, axons, and synapses have been intensely studied in multiple systems such as visual, somatosensory, olfactory, and motor systems (Hubel et al., 1977; Iwasato et al., 1997; Wong and Ghosh, 2002; Hanson and Landmesser, 2004; Serizawa et al., 2006). Electrical activity is crucial for projection and arborization of thalamocortical axons (Antonini and Stryker, 1993; Uesaka et al., 2007; Mire et al., 2012; Antón-Bolaños et al., 2019). Mire et al. (2012) reported that temporal patterns of thalamocortical neuron activity are crucial for axon guidance through regulation of the axon guidance molecule, Robo1. The activity of thalamocortical axons affects spatial patterning of dendrites in layer 4 neurons through activation of NMDAR (Mizuno et al., 2014). This demonstrates that the cooperative activity of pre- and postsynaptic neurons shapes the thalamocortical circuit (Yamada et al., 2010; Mizuno et al., 2014). Excitatory GABA is essential for dendrite formation in layer 2/3 pyramidal neurons. In layer 2/3 pyramidal neurons, excitatory-to-inhibitory switching of GABA occurs between postnatal day 6 (P6) and P14. Premature excitatory-to-inhibitory switching of GABA by expressing K-Cl co-transporter 2 (KCC2) suppresses dendritic growth in layer 2/3 pyramidal neurons (Cancedda et al., 2007). Suppression of neural activity by expressing KCNJ2 significantly reduces dendritic growth, and layer-specific projection of callosal axons in cortical layer 2/3 neurons (Cancedda et al., 2007; Mizuno et al., 2007, 2010; Wang et al., 2007). Expression of a gain-of-function CACNA1C mutant also disrupts callosal axon projection (Nakagawa-Tamagawa et al., 2021). These reports suggest that the optimal frequency of electrical activity is critical for callosal axon projection. A further study revealed that layer-specific projection of callosal axons requires postsynaptic activity (Mizuno et al., 2010).

Potential Links Between Dysfunction of Ion Channels/Transporters and Neurological Disorders

Dysfunction of ion channels or transporters is associated with neurological and psychiatric disorders such as epilepsy, autism spectrum disorder, and schizophrenia (Kullmann, 2010; Schmunk and Gargus, 2013; Guglielmi et al., 2015; Heyes et al., 2015). In some patients and mouse models of channelopathies, malformations of cortical development are observed. Ion channels and transporters play crucial roles in neocortical development; therefore, developmental defects might underlie the symptoms of channelopathies. We describe some examples below.

NMDAR is a key ligand-gated ion channel for any developmental events and plasticity in the nervous system. Mutations of NMDAR are associated with a wide variety of neurological and psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, epilepsy, and depression (Kalia et al., 2008; Hardingham and Do, 2016; Adell, 2020).

Tandem pore domain K+ channels suppress neuronal excitability by hyperpolarizing the resting membrane potential and reducing membrane resistance. A dominant-negative mutation of KCNK9 was found in patients with Birk-Barel syndrome, a maternally transmitted genomic imprinting disorder characterized by severe intellectual disability, hypotonia, and dysmorphism in the form of an elongated face (Barel et al., 2008). Knock-down or functional blockade of KCNK9 by expressing a disease-associated dominant-negative mutant channel impairs neuronal migration in the developing neocortex (Bando et al., 2014). Since migration defect is associated with many neurological and psychiatric disorders (Ross and Walsh, 2001; LoTurco and Bai, 2006; Ben-Ari, 2008), migration defect might be a candidate of its pathogenesis. Interestingly, another tandem pore domain K+ channel, KCNK2 (K2P2.1) might be linked to brain aging. Le Guen et al. (2019) investigated the genetic influence on sulcal widening in elderly individuals. They found that the regulatory region of KCNK2 influences sulcal widening, suggesting a potential link between KCNK2 expression and brain atrophy (Le Guen et al., 2019).

CACNA1C, a L-type VGCC, is associated with Timothy syndrome, which is characterized by long QT syndrome in the heart, autism spectrum disorder, and mild dysmorphism of the face. Several gain-of-function mutations of CACNA1C have been found in patients (Heyes et al., 2015). Disease-associated mutant CACNA1C disrupts neocortical development, including cell fate specification of cortical projection neurons, radial migration, dendrite formation/remodeling, and callosal axon projection (Paşca et al., 2011; Kamijo et al., 2018; Horigane et al., 2021; Nakagawa-Tamagawa et al., 2021). Downregulation of CACNA1C is also associated with psychiatric disorders. A loss-of function mutation and lower expression level of CACNA1C were found in patients with schizophrenia by genome-wide screening of disease-associated mutations (Purcell et al., 2014; Roussos et al., 2014; Heyes et al., 2015). Conditional knockout of CACNA1C impairs neurite growth in cultured cortical neurons (Kamijo et al., 2018); therefore, downregulation of CACNA1C might cause psychotic symptoms by disrupting neocortical development.

Excitatory-to-inhibitory switching of GABA is mediated by a change in expression of Cl– transporters. During the early developmental stage, Na-K-Cl co-transporter 1 (NKCC1), which transports Cl– into the cell, is highly expressed. In the later stage, expression of NKCC1 decreases and expression of KCC2, which transports Cl– out of the cell, is elevated. Excitatory-to-inhibitory switching of GABA plays important roles in neocortical development. Excitatory GABA regulates neuronal production, migration, and dendrite formation (Cancedda et al., 2007; Heck et al., 2007; Tochitani et al., 2021). Dysfunction of KCC2 or GABAAR is associated with epilepsy (Kaila et al., 2014; Kahle et al., 2016; Maljevic et al., 2019; Watanabe et al., 2019).

Similar to Timothy syndrome, mutations of ion channels associated with cardiac disorders can affect neocortical neural circuit formation. For example, expression of a gain-of-function KCNJ2 mutant that causes atrial fibrillation significantly reduces branching of callosal axons in the upper layers in the contralateral hemisphere (Mizuno et al., 2007).

In patients with other neurological channelopathies, malformation of cortical development was observed. Periventricular nodular heterotopia was observed in some patients with sleep-related hypermotor epilepsy and point mutations in the sodium-activated K+ channel KCNT1 (Slack or KNa1.1) (Rubboli et al., 2018). Polymicrogyria was observed in patients with drug-resistant epilepsy and mutations in the Ca2+-activated K+ channel KCNMA1 (BK channel) (Graber et al., 2021). Periventricular nodular heterotopia and focal cortical dysplasia were observed in patients with Dravet syndrome and mutations in the voltage-gated Na+ channel SCN1A (Nav1.1) (Barba et al., 2014). As discussed above, some neurological disorders are accompanied by malformation of the cortical gyrus. Genetically modified ferret and common marmoset are good experimental models to study the physiological mechanisms of gyrus formation (Sasaki et al., 2009; Kawasaki et al., 2012; Shinmyo et al., 2017). Despite intensive efforts in developmental and clinical studies, the links between developmental defects and channelopathies remain elusive. Further studies could reveal the developmental basis of neurological channelopathies.

Discussion

Future Perspectives: Potential Application of Advanced Optical Techniques in Developmental Neuroscience and Pathophysiological Studies of Neurological Disorders in vivo

To better understand the pathogenetic mechanisms of neurological channelopathies, it seems essential to investigate the roles of ion channels in neocortical development in vivo. Previously, developmental studies of the neocortex have been performed with fixed tissue and acute or cultured brain slices. Although these traditional methods are powerful tools to reveal the mechanisms of electrical activity-dependent neocortical development, there remain important problems. One of them is that secreted extracellular signals, including maternal signals, are washed out in the slice condition. For instance, taurine, a weak agonist of GABAAR, plays important roles in the development of the embryonic nervous system (Kilb and Fukuda, 2017). Taurine is provided to the embryo from the mother through the placenta because mouse embryos do not synthesize taurine (Sturman et al., 1977; Sturman, 1981). Thus, monitoring neocortical development in the intact brain is the next step. To achieve this, optical methods seem ideal. Recently, in vivo two-photon imaging of the neonatal and embryonic mouse neocortex has been achieved (Mizuno et al., 2014, 2018; Yuryev et al., 2016; Kawasoe et al., 2020; Hattori et al., 2020). Voltage imaging is promising to monitor electrical signals in the developing neocortex in vivo or in utero. Recently, the performance of genetically encoded voltage indicators (GEVIs) has been improved (Gong et al., 2015; Kannan et al., 2018; Adam et al., 2019; Bando et al., 2019a,b; Piatkevich et al., 2019; Villette et al., 2019; Cornejo et al., 2022). In contrast with chemical voltage-sensitive dyes (VSDs), GEVIs can be expressed in a cell-type-specific manner, resulting in an improved signal-to-noise ratio. Furthermore, long-term monitoring of electrical signals is possible using GEVIs, but not with patch-clamp recording and VSDs. Long-term monitoring of electrical activity would help researchers determine the correlation between electrical signals and developmental events such as neurogenesis, migration, and neurite growth. The combination of Ca2+ or voltage imaging and holographic photostimulation is a powerful tool to show causal links between electrical activity and developmental events (Carrillo-Reid et al., 2016). Two-photon multimodal imaging of voltage and Ca2+ in neuronal populations in vivo was recently reported (Bando et al., 2021). Application of these techniques could reveal how electrical signals are transformed into intracellular signals that drive neocortical circuit formation.

Developmental events occur in three-dimensional tissues. Thus, volumetric imaging is also important. Recently, fast three-dimensional imaging techniques were developed using a spatial light modulator, an acousto-optic lens, and an electrical tunable lens (Katona et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2016, 2018; Yang and Yuste, 2017). To image deep in the brain during development, three-photon imaging and an adaptive optics are also helpful (Ji et al., 2010; Horton et al., 2013). The combination of advanced microscopy and emerging optical probes could strongly drive developmental neuroscience.

Another important issue is how developmental defects cause neurological disorders. Recent studies showed that the properties of local neocortical circuits, such as neuronal ensembles (groups of co-active neurons), are altered in mouse models of psychiatric and neurological disorders, such as schizophrenia and autism (Fang and Yuste, 2017; Hamm et al., 2017). Simultaneous manipulation, and readout of cortical activity during behavior is promising to further elucidate the causal links between aberrant cortical activity and symptoms (Carrillo-Reid et al., 2016, 2019). Application of the recently developed two-photon mesoscope will help to clarify the alteration of cortex-wide computation at cellular resolution in animal models of disorders (Ota et al., 2021).

In summary, developmental studies revealed that dysfunction of ion channels and transporters disrupts neocortical circuit formation. Clinical studies reported potential links between neurological disorders and mutations of ion channels and transporters. However, the causal links between dysfunction of the ion channels and transporters, neocortical circuit formation, and neurological disorders are not understood. Emerging optical technologies could bridge these biophysical, developmental, and clinical studies.

Author Contributions

YB organized the content. All authors wrote, revised, and approved the manuscript for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We thank all laboratory members at the Department of Organ and Tissue Anatomy and Department of Neurophysiology for discussions.

Funding

This work was supported by the Japan Science Society, Sasakawa Scientific Research grant (YB), the Hamamatsu Society for Science and Technology (YB), the Uehara Memorial Foundation (YB), the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Grants-in-aid (20K15914 to YB; 19K07284 to MI; 17K08512, 20K21499, and 21H02655 to SY; 21H02661 and 21H05687 to AF; and 19K22594 to KS), the Takeda Science Foundation (YB and SY), and the Hamamatsu University School of Medicine Grant-in-aid (YB, MI, and SY).

References

- Adam Y., Kim J. J., Lou S., Zhao Y., Xie M. E., Brinks D., et al. (2019). Voltage imaging and optogenetics reveal behaviour-dependent changes in hippocampal dynamics. Nature 569 413–417. 10.1038/s41586-019-1166-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adell A. (2020). Brain NMDA receptors in schizophrenia and depression. Biomolecules 10:947. 10.3390/biom10060947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antón-Bolaños N., Sempere-Ferràndez A., Guillamón-Vivancos T., Martini F. J., Pérez-Saiz L., Gezelius H., et al. (2019). Prenatal activity from thalamic neurons governs the emergence of functional cortical maps in mice. Science 364 987–990. 10.1126/science.aav7617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonini A., Stryker M. P. (1993). Rapid remodeling of axonal arbors in the visual cortex. Science 260 1819–1821. 10.1126/science.8511592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bando Y., Grimm C., Cornejo V. H., Yuste R. (2019a). Genetic voltage indicators. BMC Biol. 17:71. 10.1186/s12915-019-0682-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bando Y., Sakamoto M., Kim S., Ayzenshtat I., Yuste R. (2019b). Comparative evaluation of genetically-encoded voltage indicators. Cell Rep. 26 802–813. 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.12.088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bando Y., Hirano T., Tagawa Y. (2014). Dysfunction of KCNK potassium channels impairs neuronal migration in the developing mouse cerebral cortex. Cereb. Cortex 24 1017–1029. 10.1093/cercor/bhs387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bando Y., Irie K., Shimomura T., Umeshima H., Kushida Y., Kengaku M., et al. (2016). Control of spontaneous Ca2+ transients is critical for neuronal maturation in the developing neocortex. Cereb. Cortex 26 106–117. 10.1093/cercor/bhu180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bando Y., Wenzel M., Yuste R. (2021). Simultaneous two-photon imaging of action potentials and subthreshold inputs in vivo. Nat. Commun. 12:7229. 10.1038/s41467-021-27444-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barba C., Parrini E., Coras R., Galuppi A., Craiu D., Kluger G., et al. (2014). Co-occurring malformations of cortical development and SCN1A gene mutations. Epilepsia 55 1009–1019. 10.1111/epi.12658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barel O., Shalev S. A., Ofir R., Cohen A., Zlotogora J., Shorer Z., et al. (2008). Maternally inherited Birk Barel mental retardation dysmorphism syndrome caused by a mutation in the genomically imprinted potassium channel KCNK9. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 83 193–199. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.07.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behar T. N., Schaffner A. E., Scott C. A., Greene C. L., Barker J. L. (2000). GABA receptor antagonists modulate postmitotic cell migration in slice cultures of embryonic rat cortex. Cereb. Cortex 10 899–909. 10.1093/cercor/10.9.899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behar T. N., Scott C. A., Greene C. L., Wen X., Smith S. V., Maric D., et al. (1999). Glutamate acting at NMDA receptors stimulates embryonic cortical neuronal migration. J. Neurosci. 19 4449–4461. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-11-04449.1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ari Y. (2008). Neuro-archaeology: pre-symptomatic architecture and signature of neurological disorders. Trends Neurosci. 31 626–636. 10.1016/j.tins.2008.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bittman K. S., LoTurco J. J. (1999). Differential regulation of connexin 26 and 43 in murine neocortical precursors. Cereb. Cortex 9 188–195. 10.1093/cercor/9.2.188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bortone D., Polleux F. (2009). KCC2 expression promotes the termination of cortical interneuron migration in a voltage-sensitive calcium-dependent manner. Neuron 62 53–71. 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.01.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancedda L., Fiumelli H., Chen K., Poo M. M. (2007). Excitatory GABA action is essential for morphological maturation of cortical neurons in vivo. J. Neurosci. 27 5224–5235. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5169-06.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo-Reid L., Han S., Yang W., Akrouh A., Yuste R. (2019). Controlling visually guided behavior by holographic recalling of cortical ensembles. Cell 178 447–457. 10.1016/j.cell.2019.05.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo-Reid L., Yang W., Bando Y., Peterka D. S., Yuste R. (2016). Imprinting and recalling cortical ensembles. Science 353 691–694. 10.1126/science.aaf7560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornejo V. H., Ofer N., Yuste R. (2022). Voltage compartmentalization in dendritic spines in vivo. Science 375 82–86. 10.1126/science.abg0501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang W. Q., Yuste R. (2017). Overproduction of neurons is correlated with enhanced cortical ensembles and increased perceptual discrimination. Cell Rep. 21 381–392. 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.09.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa T., Yamada J., Akita T., Matsushima Y., Yanagawa Y., Fukuda A. (2014). Roles of taurine-mediated tonic GABAA receptor activation in the radial migration of neurons in the fetal mouse cerebral cortex. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 8:88. 10.3389/fncel.2014.00088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Y., Huang C., Li J. Z., Grewe B. F., Zhang Y., Eismann S., et al. (2015). High-speed recording of neural spikes in awake mice and flies with a fluorescent voltage sensor. Science 350 1361–1366. 10.1126/science.aab0810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graber D., Imagawa E., Miyake N., Matsumoto N., Miyatake S., Graber M., et al. (2021). Polymicrogyria in a child with KCNMA1-related channelopathy. Brain Dev. 44 173–177. 10.1016/j.braindev.2021.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guglielmi L., Servettini I., Caramia M., Catacuzzeno L., Franciolini F., D’Adamo M. C., et al. (2015). Update on the implication of potassium channels in autism: K(+) channelautism spectrum disorder. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 9:34. 10.3389/fncel.2015.00034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamm J. P., Peterka D. S., Gogos J. A., Yuste R. (2017). Altered cortical ensembles in mouse models of schizophrenia. Neuron 94 153–167. 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.03.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson M. G., Landmesser L. T. (2004). Normal patterns of spontaneous activity are required for correct motor axon guidance and the expression of specific guidance molecules. Neuron 43 687–701. 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardingham G. E., Do K. Q. (2016). Linking early-life NMDAR hypofunction and oxidative stress in schizophrenia pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 17 125–134. 10.1038/nrn.2015.19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattori Y., Naito Y., Tsugawa Y., Nonaka S., Wake H., Nagasawa T., et al. (2020). Transient microglial absence assists postmigratory cortical neurons in proper differentiation. Nat. Commun. 11:1631. 10.1038/s41467-020-15409-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heck N., Kilb W., Reiprich P., Kubota H., Furukawa T., Fukuda A., et al. (2007). GABA-A receptors regulate neocortical neuronal migration in vitro and in vivo. Cereb. Cortex 17 138–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hevner R. F. (2006). From radial glia to pyramidal-projection neuron: transcription factor cascades in cerebral cortex development. Mol. Neurobiol. 33 33–50. 10.1385/MN:33:1:033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyes S., Pratt W. S., Rees E., Dahimene S., Ferron L., Owen M. J., et al. (2015). Genetic disruption of voltage-gated calcium channels in psychiatric and neurological disorders. Prog. Neurobiol. 134 36–54. 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2015.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horigane S. I., Hamada S., Kamijo S., Yamada H., Yamasaki M., Watanabe M., et al. (2021). Development of an L-type Ca2+ channel- dependent Ca2+ transient during the radial migration of cortical excitatory neurons. Neurosci. Res. 169 17–26. 10.1016/j.neures.2020.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horigane S. I., Ozawa Y., Yamada H., Takemoto-Kimura S. (2019). Calcium signalling: a key regulator of neuronal migration. J. Biochem. 165 401–409. 10.1093/jb/mvz012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton N. G., Wang K., Kobat D., Clark C. G., Wise F. W., Schaffer C. B., et al. (2013). In vivo three- photon microscopy of subcortical structures within an intact mouse brain. Nat. Photonics 7 205–209. 10.1038/nphoton.2012.336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubel D. H., Wiesel T. N., LeVay S. (1977). Plasticity of ocular dominance columns in monkey striate cortex. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 278 377–409. 10.1098/rstb.1977.0050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasato T., Erzurumlu R. S., Huerta P. T., Chen D. F., Sasaoka T., Ulupinar E., et al. (1997). NMDA receptor-dependent refinement of somatotopic maps. Neuron 19 1201–1210. 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80412-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji N., Milkie D. E., Betzig E. (2010). Adaptive optics via pupil segmentation for high-resolution imaging in biological tissues. Nat. Methods 7 141–147. 10.1038/nmeth.1411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahle K. T., Khanna A. R., Duan J., Staley K. J., Delpire E., Poduri A. (2016). The KCC2 cotransporter and human epilepsy: getting excited about inhibition. Neuroscientist 22 555–562. 10.1177/1073858416645087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaila K., Price T. J., Payne J. A., Puskarjov M., Voipio J. (2014). Cation-chloride cotransporters in neuronal development, plasticity and disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 15 637–654. 10.1038/nrn3819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalia L. V., Kalia S. K., Salter M. W. (2008). NMDA receptors in clinical neurology: excitatory times ahead. Lancet Neurol. 7 742–755. 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70165-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamijo S., Ishii Y., Horigane S. I., Suzuki K., Ohkura M., Nakai J., et al. (2018). A critical neurodevelopmental role for L-type voltage-gated calcium channels in neurite extension and radial migration. J. Neurosci. 38 5551–5566. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2357-17.2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannan M., Vasan G., Huang C., Haziza S., Li J. Z., Inan H., et al. (2018). Fast, in vivo voltage imaging using a red fluorescent indicator. Nat. Methods 15 1108–1116. 10.1038/s41592-018-0188-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katona G., Szalay G., Maák P., Kaszás A., Veress M., Hillier D., et al. (2012). Fast two-photon in vivo imaging with three-dimensional random-access scanning in large tissue volumes. Nat. Methods 9 201–208. 10.1038/nmeth.1851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz L. C., Shatz C. J. (1996). Synaptic activity and the construction of cortical circuits. Science 274 1133–1138. 10.1126/science.274.5290.1133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki H., Iwai L., Tanno K. (2012). Rapid and efficient genetic manipulation of gyrencephalic carnivores using in utero electroporation. Mol Brain 5:24. 10.1186/1756-6606-5-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasoe R., Shinoda T., Hattori Y., Nakagawa M., Pham T. Q., Tanaka Y., et al. (2020). Two-photon microscopic observation of cell-production dynamics in the developing mammalian neocortex in utero. Dev. Growth Differ. 62 118–128. 10.1111/dgd.12648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawauchi T. (2012). Cell adhesion and its endocytic regulation in cell migration during neural development and cancer metastasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 13 4564–4590. 10.3390/ijms13044564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawauchi T., Hoshino M. (2008). Molecular pathways regulating cytoskeletal organization and morphological changes in migrating neurons. Dev. Neurosci. 30 36–46. 10.1159/000109850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilb W., Fukuda A. (2017). Taurine as an essential neuromodulator during perinatal cortical development. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 11:328. 10.3389/fncel.2017.00328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komuro H., Rakic P. (1996). Intracellular Ca2+ fluctuations modulate the rate of neuronal migration. Neuron 17 275–285. 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80159-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kullmann D. M. (2010). Neurological channelopathies. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 33 151–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumada T., Komuro H. (2004). Completion of neuronal migration regulated by loss of Ca(2+) transients. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101 8479–8484. 10.1073/pnas.0401000101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Guen Y., Philippe C., Riviere D., Lemaitre H., Grigis A., Fischer C., et al. (2019). eQTL of KCNK2 regionally influences the brain sulcal widening: evidence from 15,597 UK Biobank participants with neuroimaging data. Brain Struct. Funct. 224 847–857. 10.1007/s00429-018-1808-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Hashimoto-Torii K., Torii M., Ding C., Rakic P. (2010). Gap junctions/hemichannels modulate interkinetic nuclear migration in the forebrain precursors. J. Neurosci. 30 4197–4209. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4187-09.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LoTurco J. J., Bai J. (2006). The multipolar stage and disruptions in neuronal migration. Trends Neurosci. 29 407–413. 10.1016/j.tins.2006.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LoTurco J. J., Owens D. F., Heath M. J., Davis M. B., Kriegstein A. R. (1995). GABA and glutamate depolarize cortical progenitor cells and inhibit DNA synthesis. Neuron 15 1287–1298. 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90008-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maljevic S., Møller R. S., Reid C. A., Pérez-Palma E., Lal D., May P., et al. (2019). Spectrum of GABAA receptor variants in epilepsy. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 32 183–190. 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manent J. B., Represa A. (2007). Neurotransmitters and brain maturation: early paracrine actions of GABA and glutamate modulate neuronal migration. Neuroscientist 13 268–279. 10.1177/1073858406298918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marín O. (2012). Cellular and molecular mechanisms controlling the migration of neocortical interneurons. Eur. J. Neurosci. 38 2019–2029. 10.1111/ejn.12225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medvedeva V. P., Pierani A. (2020). How do electric fields coordinate neuronal migration and maturation in the developing cortex? Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 8:580657. 10.3389/fcell.2020.580657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mire E., Mezzera C., Leyva-Díaz E., Paternain A. V., Squarzoni P., Bluy L., et al. (2012). Spontaneous activity regulates Robo1 transcription to mediate a switch in thalamocortical axon growth. Nat. Neurosci. 15 1134–1143. 10.1038/nn.3160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno H., Hirano T., Tagawa Y. (2007). Evidence for activity-dependent cortical wiring: formation of interhemispheric connections in neonatal mouse visual cortex requires projection neuron activity. J. Neurosci. 27 6760–6770. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1215-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno H., Hirano T., Tagawa Y. (2010). Pre-synaptic and post-synaptic neuronal activity supports the axon development of callosal projection neurons during different post-natal periods in the mouse cerebral cortex. Eur. J. Neurosci. 31 410–424. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.07070.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno H., Ikezoe K., Nakazawa S., Sato T., Kitamura K., Iwasato T. (2018). Patchwork-type spontaneous activity in neonatal barrel cortex layer 4 transmitted via Thalamocortical projections. Cell Rep. 22 123–135. 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno H., Luo W., Tarusawa E., Saito Y. M., Sato T., Yoshimura Y., et al. (2014). NMDAR-regulated dynamics of layer 4 neuronal dendrites during thalamocorticalreorganization in neonates. Neuron 82 365–379. 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.02.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molyneaux B. J., Arlotta P., Menezes J. R., Macklis J. D. (2007). Neuronal subtype specification in the cerebral cortex. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 8 427–437. 10.1038/nrn2151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadarajah B., Alifragis P., Wong R. O., Parnavelas J. G. (2003). Neuronal migration in the developing cerebral cortex: observations based on real-time imaging. Cereb. Cortex 13 607–611. 10.1093/cercor/13.6.607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa-Tamagawa N., Kirino E., Sugao K., Nagata H., Tagawa Y. (2021). Involvement of Calcium-dependent Pathway and β subunit-interaction in Neuronal Migration and Callosal Projection deficits caused by the Cav1.2 I1166T Mutation in Developing Mouse Neocortex. Front. Neurosci. 15:747951. 10.3389/fnins.2021.747951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtaka-Maruyama C., Okamoto M., Endo K., Oshima M., Kaneko N., Yura K., et al. (2018). Synaptic transmission from subplate neurons controls radial migration of neocortical neurons. Science 360 313–317. 10.1126/science.aar2866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary D. D., Nakagawa Y. (2002). Patterning centers, regulatory genes and extrinsic mechanisms controlling arealization of neocortex. Curr. Opin. Neurosci. 12 14–25. 10.1016/s0959-4388(02)00285-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ota K., Oisi Y., Suzuki T., Ikeda M., Ito Y., Ito T., et al. (2021). Fast, cell-resolution, contiguous-wide two-photon imaging to reveal functional network architectures across multi-modal cortical areas. Neuron 109 1810–1824. 10.1016/j.neuron.2021.03.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paşca S. P., Portmann T., Voineagu I., Yazawa M., Shcheglovitov A., Paşca A. M., et al. (2011). Using iPSC-derived neurons to uncover cellular phenotypes associated with Timothy syndrome. Nat. Med. 17 1657–1662. 10.1038/nm.2576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piatkevich K. D., Bensussen S., Tseng H. A., Shroff S. N., Lopez-Huerta V. G., Park D., et al. (2019). Population imaging of neural activity in awake behaving mice. Nature 574 413–417. 10.1038/s41586-019-1641-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picken Bahrey H. L., Moody W. J. (2003). Early development of voltage-gated ion currents and firing properties in neurons of the mouse cerebral cortex. J. Neurophysiol. 89 1761–1773. 10.1152/jn.00972.2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price D. J., Kennedy H., Dehay C., Zhou L., Mercier M., Jossin Y., et al. (2006). The development of cortical connections. Eur. J. Neurosci. 23 910–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell S. M., Moran J. L., Fromer M., Ruderfer D., Solovieff N., Roussos P., et al. (2014). A polygenic burden of rare disruptive mutations in schizophrenia. Nature 506 185–190. 10.1038/nature12975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross M. E., Walsh C. A. (2001). Human brain malformations and their lessons for neuronal migration. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 24 1041–1070. 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.1041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roussos P., Mitchell A. C., Voloudakis G., Fullard J. F., Pothula V. M., Tsang J., et al. (2014). A role for noncoding variation in schizophrenia. Cell Rep. 9 1417–1429. 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.10.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubboli G., Plazzi G., Picard F., Nobili L., Hirsch E., Chelly J., et al. (2018). Mild malformations of cortical development in sleep-related hypermotor epilepsy due to KCNT1 mutations. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 6 386–391. 10.1002/acn3.708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki E., Suemizu H., Shimada A., Hanazawa K., Oiwa R., Kamioka M., et al. (2009). Generation of transgenic non-human primates with germline transmission. Nature 459 523–527. 10.1038/nature08090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmunk G., Gargus J. J. (2013). Channelopathy pathogenesis in autism spectrum disorders. Front. Genet. 4:222. 10.3389/fgene.2013.00222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serizawa S., Miyamichi K., Takeuchi H., Yamagishi Y., Suzuki M., Sakano H. (2006). A neuronal identity code for the odorant receptor-specific and activity-dependent axon sorting. Cell 127 1057–1069. 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinmyo Y., Terashita Y., Dinh Duong T. A., Horiike T., Kawasumi M., Hosomichi K., et al. (2017). Folding of the cerebral cortex requires Cdk5 in upper-layer neurons in gyrencephalic mammals. Cell Rep. 20 2131–2143. 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.08.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer N. C. (2006). Electrical activity in early neuronal development. Nature 444 707–712. 10.1038/nature05300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturman J. A. (1981). Origin of taurine in developing rat brain. Brain Res. 254 111–128. 10.1016/0165-3806(81)90063-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturman J. A., Rassin D. K., Gaull G. E. (1977). Taurine in developing rat brain: maternal-fetal transfer of [35 S] taurine and its fate in the neonate. J. Neurochem. 28 31–39. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1977.tb07705.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabata H., Nakajima K. (2003). Multipolar migration: the third mode of radial neuronal migration in the developing cerebral cortex. J. Neurosci. 23 9996–10001. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-31-09996.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tessier-Lavigne M., Goodman C. S. (1996). The molecular biology of axon guidance. Science 274 1123–1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tissir F., Goffinet A. M. (2003). Reelin and brain development. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 4 496–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tochitani S., Furukawa T., Bando R., Kondo S., Ito T., Matsushima Y., et al. (2021). GABAA receptors and maternally derived Taurine regulate the temporal specification of progenitors of excitatory Glutamatergic neurons in the mouse developing cortex. Cereb. Cortex 31 4554–4575. 10.1093/cercor/bhab106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uesaka N., Hayano Y., Yamada A., Yamamoto N. (2007). Interplay between laminar specificity and activity-dependent mechanisms of thalamocortical axon branching. J. Neurosci. 27 5215–5223. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4685-06.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlén P., Fritz N., Smedler E., Malmersjö S., Kanatani S. (2015). Calcium signaling in neocortical development. Dev. Neurobiol. 75 360–368. 10.1002/dneu.22273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villette V., Chavarha M., Dimov I. K., Bradley J., Pradhan L., Mathieu B., et al. (2019). Ultrafast two-photon imaging of a high-gain voltage indicator in awake behaving mice. Cell 179 1590–1608.e23. 10.1016/j.cell.2019.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitali I., Fièvre S., Telley L., Oberst P., Bariselli S., Frangeul L., et al. (2018). Progenitor hyperpolarization regulates the sequential generation of neuronal subtypes in the developing neocortex. Cell 174 1264–1276.e15. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.06.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C. L., Zhang L., Zhou Y., Zhou J., Yang X. J., Duan S. M., et al. (2007). Activity- dependent development of callosal projections in the somatosensory cortex. J. Neurosci. 27 11334–11342. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3380-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe M., Zhang J., Mansuri M. S., Duan J., Karimy J. K., Delpire E., et al. (2019). Developmentally regulated KCC2 phosphorylation is essential for dynamic GABA-mediated inhibition and survival. Sci. Signal. 12:eaaw9315. 10.1126/scisignal.aaw9315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman T. A., Riquelme P. A., Ivic L., Flint A. C., Kriegstein A. R. (2004). Calcium waves propagate through radial glial cells and modulate proliferation in the developing neocortex. Neuron 43 647–661. 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong R. O., Ghosh A. (2002). Activity-dependent regulation of dendritic growth and patterning. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 3 803–812. 10.1038/nrn941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada A., Uesaka N., Hayano Y., Tabata T., Kano M., Yamamoto N. (2010). Role of pre- and postsynaptic activity in thalamocortical axon branching. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107 7562–7567. 10.1073/pnas.0900613107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W., Carrillo-Reid L., Bando Y., Peterka D. S., Yuste R. (2018). Simultaneous two-photon imaging and two-photon optogenetics of cortical circuits in three dimensions. eLife 7:e32671. 10.7554/eLife.32671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W., Miller J. E., Carrillo-Reid L., Pnevmatikakis E., Paninski L., Yuste R., et al. (2016). Simultaneous multi-plane imaging of neural circuits. Neuron 89 269–284. 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.12.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W., Yuste R. (2017). In vivo imaging of neural activity. Nat. Methods 14 349–359. 10.1038/nmeth.4230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuryev M., Pellegrino C., Jokinen V., Andriichuk L., Khirug S., Khiroug L., et al. (2016). In vivo calcium imaging of evoked calcium waves in the embryonic cortex. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 9:500. 10.3389/fncel.2015.00500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J. Q., Poo M. M. (2007). Calcium signaling in neuronal motility. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 23 375–404. 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]