Summary

Cullin-RING E3 ligases (CRLs) are essential ubiquitylation enzymes that combine a catalytic core built around cullin scaffolds with ~300 exchangeable substrate adaptors. To ensure robust signal transduction, cells must constantly form new CRLs by pairing substrate-bound adaptors with their cullins, but how this occurs at the right time and place is still poorly understood. Here, we show that formation of individual CRL complexes is a tightly regulated process. Using CUL3KLHL12 as a model, we found that its co-adaptor PEF1-ALG2 initiates CRL3 formation by releasing KLHL12 from an assembly inhibitor at the endoplasmic reticulum, before co-adaptor monoubiquitylation stabilizes the enzyme for substrate modification. As the co-adaptor also helps recruit substrates, its role in CRL assembly couples target recognition to ubiquitylation. We propose that regulators dedicated to specific CRLs, such as assembly inhibitors or co-adaptors, cooperate with target-agnostic adaptor exchange mechanisms to establish E3 ligase complexes that control metazoan development.

Keywords: ubiquitin, CUL3, monoubiquitylation, KLHL12, SEC31, PEF1, ALG2

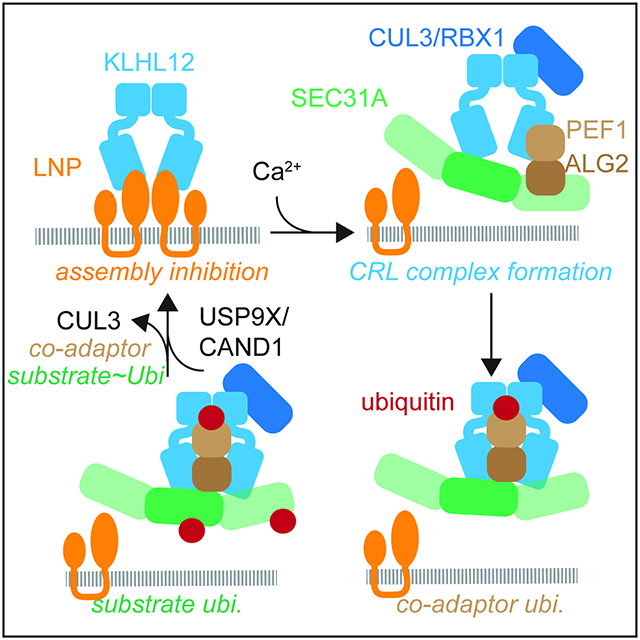

Graphical Abstract

eTOC

Modular E3 ligases are essential for signal transduction, but how cells control their composition is not fully understood. Complementing general adaptor exchange mechanisms, the authors show that formation of a CUL3 E3 ligase requires timely release of an exchangeable adaptor from an assembly inhibitor and complex stabilization through reversible monoubiquitylation.

Introduction

With the average human protein engaging five partners (Goodsell and Olson, 2000; Huttlin et al., 2017), multisubunit complexes play critical roles in cellular information transfer. Reminiscent of molecular machines, many assemblies have assigned distinct tasks to specialized subunits: while scaffolds organize complex architecture and catalytic subunits execute specific reactions, adaptor proteins recruit individual substrates. By pairing the same catalytic core with many exchangeable adaptors, cells can form multiple complexes with shared activity, but unique substrate specificity. Illustrating the importance and prevalence of such modular signaling, human cells contain ~40 PP2A phosphatases, ~30 p97/VCP AAA-ATPases, and ~300 Cullin-RING E3 ligases (CRLs) (Bennett et al., 2010; Buchberger et al., 2015; Goguet-Rubio et al., 2020; Reitsma et al., 2017). How these pivotal enzymes achieve their proper composition and select their targets at the right time and place remains a central question in biology.

As critical examples of modular enzymes, E3 ligases of the CRL family control cell division, differentiation, or survival (Jerabkova and Sumara, 2019; Rape, 2018; Reichermeier et al., 2020; Skaar et al., 2013). Members of the best understood CRLs, the SCF, consist of a CUL1 scaffold, a RBX1 catalytic subunit, and one of 69 substrate adaptors that are composed of SKP1 and a F-box protein (Jin et al., 2004; Zheng et al., 2002b) (Figure 1A). While SKP1 connects the adaptor to CUL1, each F-box protein recognizes targets based on their degron motifs (Mena et al., 2020; Skaar et al., 2013). Cells express F-box adaptor modules in excess over CUL1, and hence, must constantly form and disassemble CRL complexes based on need. Whereas the adaptor exchange factor CAND1 is known to dismantle used CRLs (Liu et al., 2018; Pierce et al., 2013; Reichermeier et al., 2020; Reitsma et al., 2017), how cells choose the next adaptor to build a new E3 ligase is still poorly understood.

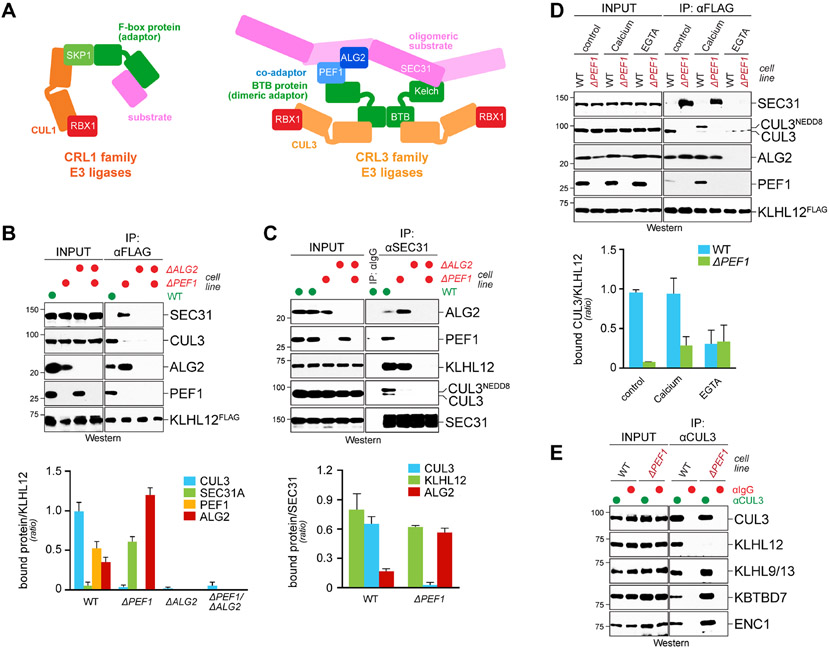

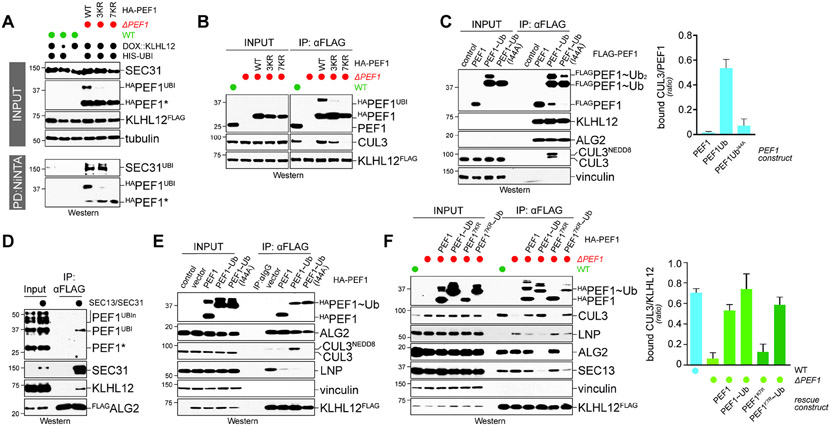

Figure 1: The PEF1-ALG2 co-adaptor is required for CUL3KLHL12 assembly.

A. Complex architecture of CRL1 and CRL3 E3 ligases. Left: CRL1 complexes consist of a CUL1 scaffold, a catalytic RBX1 subunit, and an exchangeable substrate adaptor composed of SKP1 and a F-box protein. Right: CRL3 E3 ligases possess a catalytic core composed of CUL3 and RBX1 and an exchangeable substrate adaptor containing a BTB domain. CUL3KLHL12 also requires the co-adaptor PEF1-ALG2 for stable recognition of its oligomeric substrate SEC31A. B. PEF1-ALG2 is required for CUL3KLHL12 assembly. Endogenously KLHL12FLAG was affinity-purified from 293T cells that had PEF1, ALG2, or both inactivated by CRISPR/Cas9-dependent genome editing. Co-purifying proteins were detected by Western blotting. PEF1 deletion also destabilized ALG2, as it is often observed for protein complexes. C. Endogenous SEC31A was affinity-purified from wildtype cells, cells lacking PEF1 or ALG2, or cells devoid of both co-adaptor subunits, and bound proteins were detected by Western blotting. D. Endogenous KLHL12FLAG was affinity-purified from control or ΔPEF1 cells treated with buffer; EGTA to chelate Ca2+; or additional Ca2+ to mimic ER Ca2+ release. Co-purifying proteins were detected by Western blotting. E. PEF1-ALG2 is required for assembly of CUL3KLHL12, but not other CRL3 complexes. Endogenous CUL3 was affinity-purified from wildtype cells or cells lacking PEF1 and co-purifying BTB adaptors were detected by Western blotting. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. See also Figure S1.

Once an SCF complex has been assembled, its cullin scaffold is modified with the ubiquitin-like protein NEDD8 (Baek et al., 2020b; Meyer-Schaller et al., 2009). In addition to stabilizing the enzyme’s active conformation (Baek et al., 2020a), NEDD8 prevents CAND1 from accessing the E3 ligase and thereby ensures that substrate-bound CRLs are not prematurely dismantled (Liu et al., 2002; Zheng et al., 2002a). After a CRL has released its target, the CSN signalosome cleaves NEDD8 off the cullin and thus allows CAND1 to take apart the CRL complex (Dubiel et al., 2013; Emberley et al., 2012; Enchev et al., 2012; Pierce et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2013; Zemla et al., 2013). Similar to NEDD8 modification, some E3 ligases are activated by ubiquitylation (Kelsall et al., 2019; Uzunova et al., 2012), but whether ubiquitin controls enzyme assembly and whether such regulation is implemented for CRLs is not known.

While formation of SCF E3 ligases has been extensively studied, less is known for CRL3 enzymes that pair a CUL3-RBX1 core with ~120 substrate adaptors containing a BTB domain (Furukawa et al., 2003; Geyer et al., 2003; Mena et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2003) (Figure 1A). CRL3 enzymes control stress signaling, vesicle transport, cell differentiation, or neurotransmission, and mutations in CUL3 or its adaptors lead to aberrant tissue formation and homeostasis (Jerabkova and Sumara, 2019; Rape, 2018; Tokheim et al., 2021). Intriguingly, most CRL3 adaptors are dimers or tetramers that often associate with oligomeric substrates (Geyer et al., 2003; Marzahn et al., 2016; Mena et al., 2020; Mena et al., 2018; Pintard et al., 2003; Werner et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2003; Zhuang et al., 2009). This results in multivalent interactions between the E3 ligase and its target and delays the release of ubiquitylated proteins (Werner et al., 2018). As CAND1 only acts on E3 ligases that are not engaged with substrates, additional factors likely control the CRL3 assembly cycle.

Indeed, many CRL3 E3 ligases require co-adaptor subunits to ubiquitylate their targets: CUL3KLHL12 relies on PEF1-ALG2 to modify the COPII coat protein SEC31A at the endoplasmic reticulum (McGourty et al., 2016). CUL3KBTBD8 cooperates with β-arrestin to target nucleolar ribosome assembly factors (Werner et al., 2018; Werner et al., 2015), CUL3KCTD10 teams up with IRSp53 to remodel actin bundles at sites of cell fusion (Rodriguez-Perez et al., 2021b), and CUL3KLHL10 depends on a Krebs cycle enzyme to ubiquitylate mitochondrial membrane proteins (Aram et al., 2016). Co-adaptors are thought to translate a spatial cue, such as calcium release from the ER, into substrate binding (McGourty et al., 2016; Werner et al., 2018), but how this is integrated with CRL3 assembly is not known.

Here, we show that co-adaptors not only recruit substrates, but can also drive CRL complex assembly. While investigating CUL3KLHL12, we found that its co-adaptor PEF1-ALG2 is required for E3 ligase formation even if the adaptor KLHL12 has engaged its target. The co-adaptor elicits formation of CUL3KLHL12 in at least two ways: it releases KLHL12 from an ER-bound assembly inhibitor, before co-adaptor monoubiquitylation stabilizes the enzyme for effective target modification. We therefore propose that regulatory factors dedicated to individual enzymes, such as the assembly inhibitor and co-adaptor described here, collaborate with target-agnostic adaptor exchange mechanisms to control the formation of modular E3 ligases of the CRL family.

Results

Co-adaptor dependent assembly of CUL3KLHL12

Several CRL3 enzymes rely on co-adaptors to bind their targets at specific locations in the cell, but how substrate recognition and ubiquitylation are coordinated is not known. To address this issue, we focused on PEF1-ALG2, a heterodimeric co-adaptor that allows CUL3 and its adaptor KLHL12 to monoubiquitylate SEC31A at budding COPII vesicles (McGourty et al., 2016). The modification of SEC31A increases COPII vesicle size so that large cargo can be directed from the ER towards secretion or autophagosomal degradation (Jin et al., 2012; Omari et al., 2018).

We began by using CRISPR/Cas9-dependent genome editing to delete PEF1, ALG2, or both in cells that expressed endogenously FLAG-tagged KLHL12 (Figure 1B). We then purified KLHL12 and asked how its interactions changed upon loss of co-adaptor subunits. Supporting previous work (McGourty et al., 2016), we found that deletion of ALG2, which directly engages SEC31A (Helm et al., 2014; Shibata et al., 2007) (Figure S1A), prevented target recognition by KLHL12 (Figure 1B). As seen for other CRLs, the loss of substrate binding prohibited KLHL12’s incorporation into CUL3 complexes. Deletion of PEF1, however, had a very different consequence: rather than disrupting substrate recognition, loss of PEF1 increased the interaction between KLHL12 and SEC31A, yet binding of CUL3 was still almost entirely abrogated (Figure 1B). Reciprocal affinity-purification of endogenous SEC31A confirmed this observation: while SEC31A readily captured KLHL12 in ΔPEF1 cells, it was not incorporated into CUL3 complexes (Figure 1C).

In line with defective CUL3KLHL12 assembly, SEC31A was not ubiquitylated in ΔPEF1 cells, despite its association with KLHL12 (Figure S1B). Because the PEF1-ALG2 stabilized substrate binding to KLHL12 in vitro more efficiently than ALG2 alone (Figure S1A), it therefore appears that the increase in SEC31A association with KLHL12 in ΔPEF1 cells is caused by delayed product release from KLHL12. Thus, although KLHL12 can engage its target in the absence of PEF1, it is unable to assemble a CRL3 complex and catalyze SEC31A ubiquitylation.

In its established role, PEF1-ALG2 translates ER calcium release into SEC31A capture by KLHL12 (McGourty et al., 2016). Calcium chelation by EGTA accordingly prevented KLHL12 from binding SEC31A, which was also the case in the absence of PEF1 (Figure 1D). Without being able to recognize its target, KLHL12 could not recruit CUL3. Supplementing cells with more calcium had the opposite effect and stimulated the binding of KLHL12 to PEF1 and CUL3 (Figure 1D), which, as expected from the restricted access of the CSN signalosome (Emberley et al., 2012; Enchev et al., 2012), increased NEDD8-modification of CUL3. However, even additional calcium did not allow KLHL12 to engage CUL3 in ΔPEF1 cells (Figure 1D). The co-adaptor is therefore required for CUL3KLHL12 assembly in response to the physiological signal that induces ubiquitylation.

All known co-adaptors collaborate with specific BTB proteins to establish CRL3 complexes of unique substrate selectivity. In line with this notion, PEF1 deletion eliminated the association of CUL3 with KLHL12, yet it did not affect any other adaptor detected in CUL3 immunoprecipitates (Figure 1E). We conclude that the co-adaptor PEF1-ALG2 drives formation of a specific CRL3, CUL3KLHL12. As KLHL12 binds SEC31A in the absence of PEF1, the co-adaptor promotes CRL3 assembly independently of its role in recruiting substrates to the E3 ligase.

LNP is a candidate CRL3 assembly inhibitor

Although CUL3KLHL12 required PEF1 for its assembly in cells, it is sufficient to ubiquitylate SEC31A in vitro (Jin et al., 2012; McGourty et al., 2016). When provided at high concentrations, KLHL12 could accordingly bind recombinant CUL3 independently of PEF1 (Figure S1C), and KLHL12 overexpression overcame the defect in CUL3 recruitment in ΔPEF1 cells (Figure S1D).

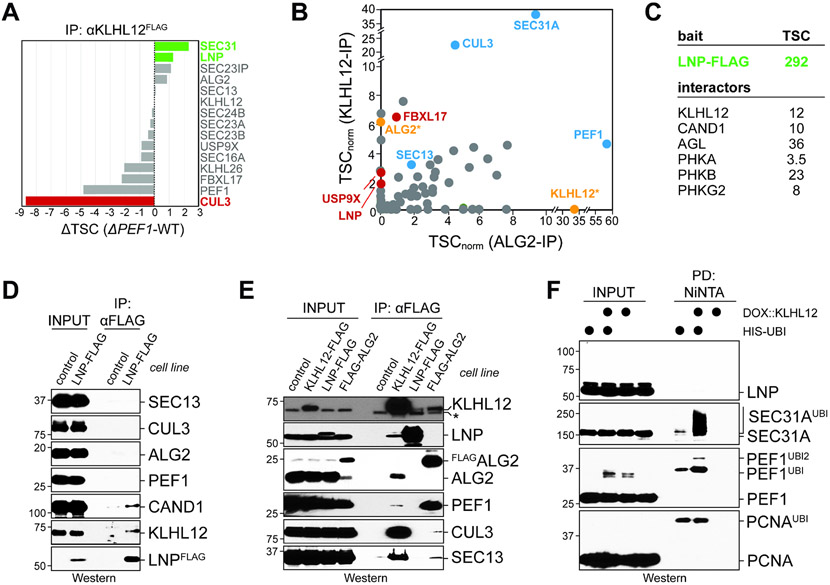

These results led us to hypothesize that PEF1 opposes an unknown inhibitor of CUL3KLHL12 assembly that was absent from our reconstituted systems and became saturated by KLHL12 overexpression. This inhibitor should bind KLHL12 more efficiently in the absence of PEF1, yet we did not expect it to be part of CUL3KLHL12-PEF1-ALG2 holoenzymes. To isolate this protein, we searched by mass spectrometry for binding partners of endogenous KLHL12 that were enriched in ΔPEF1 cells. We then asked if any such KLHL12 interactor was missing from CUL3KLHL12 complexes that were purified through endogenous FLAGALG2. These experiments confirmed that loss of PEF1 increased the association of KLHL12 with SEC31A, while binding of CUL3 was strongly diminished (Figure 2A). At the same time, PEF1 deletion promoted the interaction of KLHL12 with Lunapark (LNP) (Figure 2A), an ER membrane protein that was not detected in CUL3KLHL12-PEF1-ALG2 enzymes (Figure 2B). While we and others had noted LNP in complexes of overexpressed KLHL12 (McGourty et al., 2016; Yuniati et al., 2020), these findings suggested that endogenous LNP preferentially interacts with KLHL12 molecules that are not engaged with co-adaptor or CUL3.

Figure 2: LNP binds KLHL12 in the absence of co-adaptor or CUL3.

A. PEF1 deletion increases the association of KLHL12 with Lunapark (LNP). Endogenous KLHL12FLAG was affinity-purified from wildtype or ΔPEF1 cells and bound proteins were identified by mass spectrometry. The difference between normalized total spectral counts (TSCs) from each condition is shown. B. LNP binds KLHL12 but not CUL3KLHL12-PEF1-ALG2 complexes purified through endogenously FLAG-tagged ALG2. Binding partners of endogenous KLHL12FLAG or FLAGALG2 were determined by mass spectrometry and shown as their normalized TSCs. Blue: core CUL3KLHL12components or substrates; red: proteins preferentially detected in KLHL12, but not CUL3KLHL12, purifications; orange: KLHL12 or ALG2 baits (only shown in the opposite pulldown, not as bait). C. Endogenous LNPFLAG was affinity-purified and binding partners were determined by mass spectrometry. Total spectral counts for specific interactors are shown. D. Validation of endogenous LNPFLAG affinity-purification by Western blotting. SEC13 is a constitutive binder of SEC31A that is detected more easily by Western blotting and used as a surrogate for substrate binding. E. Endogenous LNP does not bind CUL3 or PEF1-ALG2. Endogenous KLHL12, LNP, or ALG2 were affinity-purified in parallel and analyzed for binding partners by Western blotting. The asterisk marks a non-specific band in Western blots of the KLHL12 antibody. F. Ubiquitin conjugates were purified under denaturing conditions from cells expressing His-tagged ubiquitin or doxycycline-induced KLHL12FLAG. Ubiquitylated proteins were detected using specific antibodies.

Affinity-purification of endogenously FLAG-tagged LNP confirmed that it bound KLHL12, yet we did not find evidence for an interaction with CUL3, PEF1, or ALG2 (Figure 2C, D). LNP also recognized CAND1, as noted before (Kajiho et al., 2019). When we purified endogenous KLHL12, ALG2, and LNP in parallel, we again found that LNP engaged KLHL12, while it did not associate with CUL3 or PEF1-ALG2 (Figure 2E). In line with its failure to bind CUL3KLHL12, LNP was not ubiquitylated by CUL3KLHL12 in vivo, although CUL3KLHL12 extensively modified SEC31A and PEF1 in the same experiment (Figure 2F). We conclude that endogenous LNP interacts with KLHL12, but not with the active E3 ligase, CUL3KLHL12. This finding raised the possibility that LNP inhibits CUL3KLHL12 assembly, until it is counteracted by PEF1-ALG2.

LNP restricts CUL3KLHL12 assembly

To test this hypothesis, we first wished to confirm that loss of PEF1 increased the association of LNP with KLHL12. Indeed, using affinity-purification and Western blotting, we found a striking increase of LNP binding to KLHL12 in ΔPEF1 cells (Figure 3A). Deletion of ALG2 also improved this interaction, showing that LNP preferentially engages KLHL12 molecules that do not bind CUL3. PEF1 overexpression had the opposite effect and reduced the association of KLHL12 with LNP, while it stimulated recruitment of CUL3 (Figure 3B). The overexpression of PEF1 also disrupted the co-localization of KLHL12 and LNP that is seen by immunofluorescence microscopy (Figure 3C).

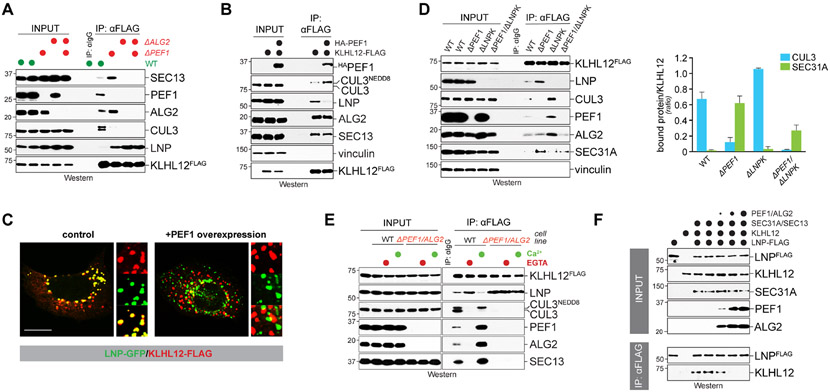

Figure 3: PEF1 and LNP compete for access to KLHL12.

A. PEF1 or ALG2 deletion increases LNP binding to KLHL12, while binding to CUL3 is lost. Endogenous KLHL12FLAG was purified from cells lacking PEF1, ALG2, or both, and bound proteins were detected by Western. B. PEF1 overexpression reduces LNP binding to KLHL12. KLHL12FLAG and HAPEF1 were expressed as indicated, KLHL12FLAG was affinity-purified, and bound proteins were detected by Western. C. PEF1 overexpression disrupts colocalization of KLHL12 and LNP. Localization of LNPGFP (green) and KLHL12FLAG (red) was analyzed in U2OS cells either in the absence (left panel) or presence (right panel) of overexpressed PEF1. Scale bar: 10 μm D. LNPK deletion increases co-adaptor and CUL3 binding to KLHL12. Endogenous KLHL12FLAG was affinity purified from cells lacking LNPK, PEF1, or both and bound proteins were detected by Western. E. Calcium controls LNP binding to KLHL12 dependent on PEF1-ALG2. Wildtype or ΔALG2ΔPEF1 cells expressing endogenous KLHL12FLAG were treated with buffer, EGTA, or Ca2+. KLHL12 was affinity-purified and bound proteins were detected by Western. F. PEF1-ALG2 dissociates KLHL12-LNP complexes. A fusion of N- and C-terminal LNP domains was immobilized and incubated with KLHL12 to form KLHL12-LNP complexes. PEF1-ALG2 was added and remaining complexes were analyzed by Western blotting. All binding reactions contained SEC31A-SEC13 complexes to allow formation of substrate-bound KLHL12, the product of PEF1-ALG2 activity. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. See also Figure S2.

To further investigate the relationship between LNP and PEF1, we asked whether deletion of LNPK, the gene encoding LNP, affects co-adaptor recognition by endogenous KLHL12. We noted that the loss of LNP impaired the association of KLHL12 with the membrane fraction (Figure S2A), suggesting that the ER protein LNP recruits KLHL12 to its site of activation in the cell. At the same time, the absence of LNP stimulated the association of KLHL12 with PEF1-ALG2 and CUL3 (Figure 3D), and it improved formation of large COPII vesicles (Figure S2B), the product of CUL3KLHL12 activation (Jin et al., 2012). Overexpression of LNP or its carboxy-terminal domain had the opposite effect and obliterated the binding of KLHL12 to co-adaptor and CUL3 (Figure S2C). Together, these results showed that LNP and PEF1 compete for access to KLHL12 to regulate formation of CUL3KLHL12 complexes.

Reminiscent of PEF1 deletion, we found that calcium chelation, a condition that inactivates CUL3KLHL12, stabilized LNP’s association with KLHL12 (Figure 3E). As seen before (McGourty et al., 2016), the lack of calcium also prevented KLHL12 from engaging CUL3. Supplementing cells with calcium had the opposite effect and released LNP from KLHL12, which was accompanied by increased binding of KLHL12 to NEDD8-modified active CUL3. Importantly, changes in calcium levels did not alter the interaction between LNP and KLHL12 if PEF1 and ALG2 were deleted (Figure 3E). The competition between co-adaptor and LNP for access to KLHL12 is therefore regulated by calcium signaling, the physiological trigger of CUL3KLHL12 activation.

To reconstitute this regulatory circuit, we generated LNPN-C, which lacks transmembrane domains yet retains its ability to bind KLHL12 in cells (Figure S2C). After immobilizing LNPN-C on beads, we found that it recognized, and thus directly bound, purified KLHL12 (Figure S2D). By contrast, when we favored assembly of CUL3KLHL12 by including co-adaptor and calcium, KLHL12 did not engage LNP, which showed that KLHL12 can either bind LNP or form a CUL3KLHL12 E3 ligase. To determine whether PEF1-ALG2 displaces KLHL12 from LNP, we immobilized LNPN-C-KLHL12 complexes on beads and incubated these with increasing concentrations of PEF1-ALG2. As this resulted in a dose-dependent release of KLHL12 from LNP (Figure 3F), we postulate that LNP inhibits assembly of CUL3KLHL12 until it is displaced by the co-adaptor, PEF1-ALG2.

PEF1 interactions with CUL3KLHL12

A recent study showed that LNP uses a Pro-rich motif to bind KLHL12 (Yuniati et al., 2020), an observation that we confirmed (Figure 4A). PEF1 possesses a similar Pro-rich sequence in its amino-terminal domain, which is required for recognition by KLHL12 (Figure 4A) and for restoring CUL3KLHL12 assembly in ΔPEF1 cells (Figure 4B). In line with their competing functions towards CUL3KLHL12, PEF1 and LNP contain similar sequence motifs that mediate KLHL12 recognition.

Figure 4: PEF1 requires the BTB domain of KLHL12 for stable binding.

A. KLHL12FLAG was affinity-purified from cells that co-expressed HA-tagged wildtype or Pro-motif mutant LNP or PEF1, respectively. Binding of LNP or PEF1 to KLHL12 was detected by Western blotting. B. A PEF1 mutant with a defective KLHL12-binding Pro-rich motif fails to support CUL3KLHL12 assembly. ΔPEF1 cells expressing endogenously FLAG-tagged KLHL12 were reconstituted with wildtype or mutant PEF1. KLHL12 was affinity-purified and bound proteins were detected by Western. C. PEF1 requires both the Kelch repeats as well as the BTB domain in KLHL12 for binding. Wildtype KLHL12 or mutants (ΔSUB: FG289/290AA; AMF: A60D/M61A/F62A; C3: L66A/S67A/E68A) were affinity-purified from 293T cells and analyzed for bound HA-tagged LNP or endogenous PEF1-ALG2 by Western. D. Endogenous KLHL12FLAG was purified from wildtype or ΔALG2/ΔPEF1 cells transfected with control siRNAs or siRNAs targeting CUL3, and bound proteins were detected by Western blotting. E. The BTB domain of KLHL12 is required for association with PEF1-ALG2. KLHL12, monomeric KLHL12, a fusion between the BTB domain of KLHL41 and the Kelch repeats of KLHL12, or a fusion of the BTB domain of KLHL12 with the Kelch repeats of KLHL41 were affinity-purified from 293T cells and analyzed for HALNP and endogenous PEF1-ALG2 or CUL3 by Western blotting using specific antibodies. See also Figure S3.

The converse experiment showed that mutation of a loop in the Kelch repeats of KLHL12 (“ΔSUB”), which detects the Pro-rich motif (Chen et al., 2020; Jin et al., 2012), prevented the interaction of KLHL12 with PEF1 (Figure 4C). Surprisingly, mutation of Leu66/Ser67/Glu68 to Ala residues in the BTB domain of KLHL12 (“C3”), a surface known to recruit CUL3, also impaired its association with PEF1-ALG2 (Figure 4C). While the BTB mutation caused the expected defect in CUL3 binding, it did not inhibit LNP recognition by KLHL12. An independent BTB mutation (“AMF”; Ala60/Met61/Phe62 to Glu/Glu/Ala) similarly reduced the association of KLHL12 with PEF1-ALG2 and CUL3 without affecting LNP recognition. Consistent with the notion that both the BTB domain and Kelch repeats contribute to co-adaptor recognition, neither KLHL12 domain alone was sufficient to recruit PEF1, and as a consequence, CUL3 (Figure S3). As depletion of CUL3 did not prevent KLHL12 from recognizing PEF1 (Figure 4D), the co-adaptor appears to require the BTB domain of KLHL12 for a stable interaction.

To further probe the involvement of KLHL12’s BTB domain in recruiting PEF1, we replaced the BTB domain of KLHL12 with that of KLHL41. The latter BTB domain homodimerizes to bring two Kelch repeats into proximity, which is needed for KLHL12 to associate with PEF1-ALG2 and SEC31A at the same time (McGourty et al., 2016); however, it is sufficiently different from KLHL12 to test whether the BTB domain specifies co-adaptor recognition. While PEF1-ALG2 associated with wildtype KLHL12, it did not bind the fusion between the BTB-domain of KLHL41 and the Kelch repeats of KLHL12 (Figure 4E). By contrast, the recognition of LNP was not affected by the presence of KLHL41’s BTB domain. We conclude that PEF1 not only depends on the Kelch repeats, but also the BTB domain of KLHL12, to engage this CRL3 adaptor. As the BTB domain recruits CUL3, this finding further links the co-adaptor to the process of CUL3KLHL12 assembly.

PEF1 ubiquitylation stabilizes CUL3KLHL12

If it were PEF1’s only task to release KLHL12 from LNP, LNPK deletion should rescue CUL3KLHL12 assembly in cells lacking PEF1. As this was not the case (Figure 3D), PEF1 must have additional functions in controlling CUL3KLHL12 formation. Considering the role of KLHL12’s BTB domain in recruiting PEF1, we therefore asked whether PEF1 monoubiquitylation, which we had described before (McGourty et al., 2016), also regulates CRL3 assembly or stability.

As we knew that the PEF1 has multiple functions towards CUL3KLHL12, we decided to test for a role of PEF1 modification in CRL assembly by generating a ubiquitylation-resistant protein. We mutated three Lys residues in PEF1 that were modified in proteomic analyses (PEF13KR) or removed all Lys residues (PEF17KR). To analyze the ubiquitylation status of these variants, we introduced them into ΔPEF1 cells that expressed His-tagged ubiquitin and purified conjugates under denaturing conditions. While PEF13KR was modified less abundantly than the wildtype protein, mutation of all Lys residues in PEF17KR abolished ubiquitylation (Figure 5A). Intriguingly, cells that expressed PEF17KR were unable to modify the CUL3KLHL12 substrate SEC31A. This experiment thus not only showed that all Lys residues in PEF1 had to be mutated to prevent its ubiquitylation, but it also suggested that PEF1 modification is required for full CUL3KLHL12 activity.

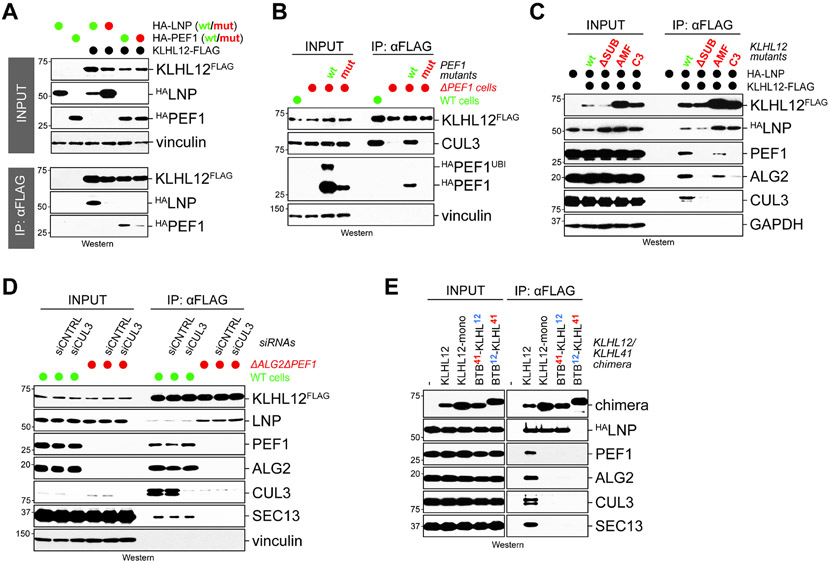

Figure 5: PEF1 monoubiquitylation stabilizes CUL3KLHL12 complexes.

A. PEF1 ubiquitylation is required for full CUL3KLHL12 activity. ΔPEF1 293T cells were reconstituted with PEF1, PEF13KR, or PEF17KR lacking all Lys residues of PEF1. Cells expressed HISubiquitin and KLHL12FLAG as indicated. Following denaturing purification, ubiquitylated PEF1 or SEC31A were detected by Western. B. PEF1 ubiquitylation sites are required for CUL3KLHL12 assembly. ΔPEF1 cells expressing endogenous KLHL12FLAG were reconstituted with indicated PEF1 mutants. KLHL12FLAG was affinity-purified and bound CUL3 was detected by Western. C. Ubiquitylation of PEF1 promotes its incorporation into CUL3 complexes. FLAG-tagged PEF1, PEF1~Ub, or PEF1~UbI44A were purified from 293T cells and bound KLHL12, ALG2, and CUL3 were detected by Western. Quantification is shown on the right. D. Monoubiquitylated PEF1 is retained by substrate-bound CUL3KLHL12. Recombinant FLAGALG2 was immobilized on beads and incubated with ubiquitylated PEF1 generated in vitro by CUL3KLHL12. When indicated, SEC31A was included to connect ALG2 with CUL3KLHL12. Bound PEF1 was detected by Western. E. Ubiquitylated PEF1 stabilizes CUL3KLHL12. Endogenously FLAG-tagged KLHL12 was affinity-purified from cells expressing HA-tagged PEF1 variants, and bound proteins were detected by Western blotting. F. The indicated HA-tagged PEF1 constructs were expressed in ΔPEF1 cells with endogenously FLAG-tagged KLHL12. KLHL12 was affinity-purified and bound proteins were detected by Western. Quantification is shown on the right. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. See also Figure S4.

Having ubiquitylation-resistant PEF1 at hand, we expressed it in ΔPEF1 cells to test for its impact on CUL3 recruitment to endogenous KLHL12. While wildtype PEF1 or PEF13KR restored the interaction between KLHL12 and CUL3, cells that only expressed non-ubiquitylatable PEF17KR could not form stable CUL3KLHL12 complexes (Figure 5B). Reciprocal affinity-purification of CUL3 supported these observations: CUL3 captured KLHL12 in ΔPEF1 cells reconstituted with PEF1 or PEF13KR, yet it did not associate with KLHL12 in cells that only expressed PEF17KR (Figure S4A). As shown below, PEF17KR maintained its ability to bind ALG2 and therefore is likely properly folded. These findings indicated that cells must be able to ubiquitylate PEF1 to maintain stable CUL3KLHL12 complexes.

We next asked if increasing PEF1 modification showed the opposite effect of preventing PEF1 ubiquitylation and improve CUL3KLHL12 assembly. Indeed, when we fused PEF1 to ubiquitin to generate a constitutively ubiquitylated protein (PEF1~Ub), we found that it engaged CUL3 much more efficiently than its unmodified counterpart (Figure 5C). Fusing PEF1 to ubiquitin with a mutant hydrophobic patch (PEF1~UbI44A) did not enhance CUL3 binding; thus, it was ubiquitin recognition, rather than steric effects, that improved the interaction between PEF1 and CUL3. While PEF1~Ub was recruited to CUL3 via KLHL12, loss of ALG2 or calcium chelation – two conditions that abrogate SEC31A binding – had no impact on the interaction of PEF1~Ub with KLHL12 and CUL3 (Figure S4B, C). If we ubiquitylated PEF1 in vitro to install the modification on its proper Lys residues, monoubiquitylated PEF1 was also much more effectively retained by CUL3KLHL12 than the unmodified or polyubiquitylated protein (Figure 5D). These findings showed that PEF1 ubiquitylation enhances its association with CUL3KLHL12.

As PEF1 is required for CUL3KLHL12 assembly, these results indicated that modification of PEF1 could stabilize the E3 ligase complex. To test this hypothesis, we purified KLHL12FLAG from cells that expressed PEF1~Ub along with endogenous PEF1 and therefore possessed both unmodified and ubiquitylated PEF1. We found that PEF1~Ub strongly improved the recruitment of CUL3 to KLHL12 (Figure 5E). As seen for the interactions of PEF1, CUL3KLHL12 assembly required a functional hydrophobic patch in the fused ubiquitin. PEF1~Ub displaced LNP from KLHL12 with similar efficiency as PEF1 or PEF1~UbI44A (Figure 5E; Figure S4D), which indicated that PEF1 ubiquitylation stabilizes CUL3KLHL12 independently of releasing the assembly inhibitor. In vitro, recombinant PEF1~Ub stimulated the association of KLHL12 to CUL3, when the E3 ligase scaffold and adaptor were present at low concentrations (Figure S4E).

We next purified KLHL12 from ΔPEF1 cells that were reconstituted with the PEF1 variants described above and thus only contained the heterologous protein, but no endogenous PEF1. As we had seen before, KLHL12 did not associate with CUL3 in the absence of PEF1, and expression of PEF1, but not the ubiquitylation-resistant PEF1KR7, restored CUL3KLHL12 assembly (Figure 5F). If we introduced PEF1KR7~Ub into ΔPEF1 cells, CUL3KLHL12 complexes were readily detected, which showed that ubiquitylation is required for PEF1 to drive CUL3KLHL12 assembly. However, cells that only expressed PEF1~Ub fusions without unmodified PEF1 did not maintain ALG2 or SEC13 in complexes with CUL3 and KLHL12, suggesting that both unmodified and ubiquitylated PEF1 are needed for CUL3KLHL12 function: while unmodified PEF1 likely cooperates with ALG2 to recruit the substrate, ubiquitylated PEF1 stabilizes CUL3KLHL12 for efficient target modification.

Control of PEF1 ubiquitylation

Our findings implied that PEF1 must cycle through unmodified and ubiquitylated states to control CUL3KLHL12, and cells should therefore express a deubiquitylase that removes ubiquitin from PEF1. To identify this enzyme, we subjected PEF1~Ub, which can be recognized but not cleaved by DUBs, to affinity-purification and mass spectrometry and found that it strongly enriched USP9X (Figure 6A). By contrast, PEF1 fused to ubiquitin with a mutant hydrophobic patch (PEF1~UbI44A) did not recruit USP9X. Analysis of affinity-purifications by Western blotting confirmed that PEF1~Ub captured USP9X much more efficiently than PEF1, PEF1~UbI44A or a PEF1~Ub* fusion carrying a short insertion in ubiquitin (Figure 6B). Calcium chelation enhanced the binding of USP9X to PEF1~Ub (Figure S4C), suggesting that USP9X might inactivate CUL3KLHL12.

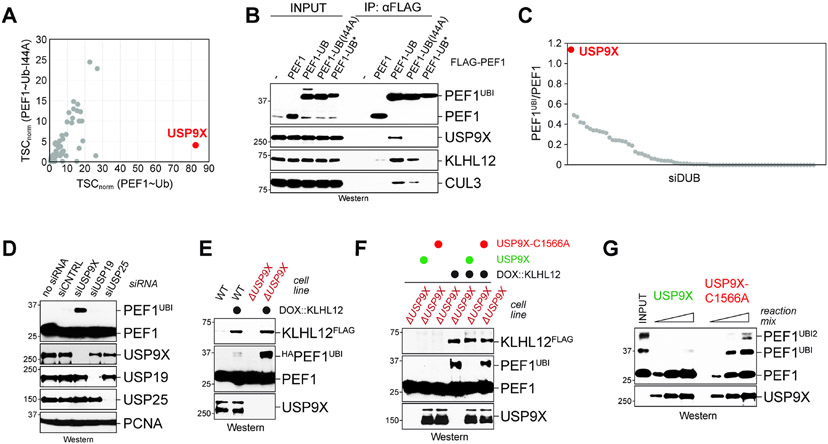

Figure 6: USP9X targets ubiquitylated PEF1.

A. PEF1~Ub, which is recognized but not cleaved by DUBs, was affinity-purified from 293T cells and binding partners were determined by mass spectrometry. PEF1~UbI44A was used as control. B. PEF1~Ub, but not PEF1, PEF1~UbI44A, or PEF1~Ub* (carrying a small insertion in ubiquitin), is recognized by USP9X. PEF1 variants were affinity-purified and binding partners were detected by Western blotting. C. Each of 75 DUBs were depleted from 293T cells using siRNAs. Following doxycycline-dependent induction of KLHL12, cell lysates were investigated for PEF1 ubiquitylation using Western blotting. Shown is the ratio of ubiquitylated to unmodified PEF1. D. 293T cells were depleted of USP9X and control DUBs. KLHL12 expression was induced by doxycycline and levels of ubiquitylated PEF1 were analyzed by Western. E. Deletion of USP9X by CRISPR/Cas9-dependent genome engineering leads to increased PEF1 ubiquitylation. Lysates of wildtype or ΔUSP9X cells were analyzed by Western blotting for PEF1 ubiquitylation after KLHL12 induction. F. ΔUSP9X cells were transfected with USP9X or USP9XC1566A, KLHL12 was induced with doxycycline, and PEF1 monoubiquitylation was investigated by Western. G. PEF1 was ubiquitylated by recombinant CUL3KLHL12 and incubated with either USP9X or USP9XC1566A that had been purified from 293T cells. Modification of PEF1 was visualized by Western blotting for increasing amounts of reaction mix.

To complement these binding studies, we depleted ~75 DUBs from cells and monitored PEF1 ubiquitylation after CUL3KLHL12 was activated by doxycycline-induced KLHL12 expression. Both this comprehensive analysis and a targeted experiment using independent siRNAs showed that USP9X is the predominant DUB that counteracts PEF1 modification (Figure 6C, D). We also observed increased PEF1 ubiquitylation in ΔUSP9X cells generated by genome editing (Figure 6E), which was reverted upon re-expression of active USP9X, but not catalytically dead USP9XC1566A (Figure 6F). As USP9X, but not USP9XC1566A, deubiquitylated PEF1 in vitro (Figure 6G), we conclude that PEF1 ubiquitylation is removed by USP9X.

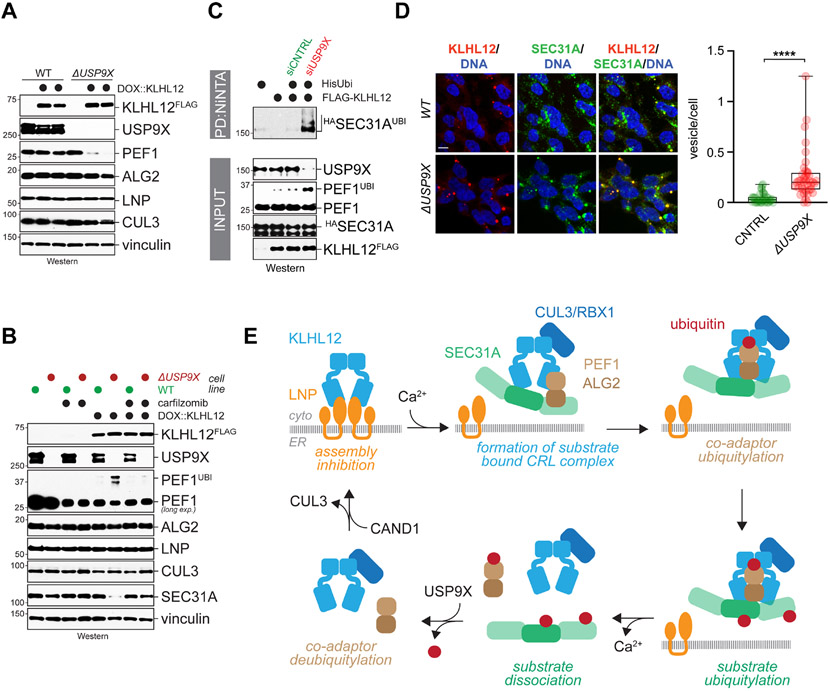

Having shown than USP9X targets PEF1 provided us with an approach to ask whether PEF1 ubiquitylation activates CUL3KLHL12, as expected from our analysis of CUL3KLHL12 complex formation. We first noted that expression of KLHL12 in ΔUSP9Xcells led to a precipitous drop in PEF1 (Figure 7A), which limited the steady state levels of KLHL12-SEC31A complexes (Figure S5). Although changes in soluble PEF1 were prevented by treatment of cells with carfilzomib (Figure 7B), the proteasome inhibitor already blocked PEF1 monoubiquitylation, potentially by depleting free ubiquitin. Rather than driving PEF1 degradation, we propose that increased PEF1 ubiquitylation activates CUL3KLHL12, which results in large COPII structures that might ultimately be cleared from cells.

Figure 7: USP9X restricts CUL3KLHL12 activity.

A. USP9X deletion causes a KLHL12-dependent decrease in the abundance of PEF1 in lysates. Expression of KLHL12FLAG was induced in wildtype or ΔUSP9X 293T cells, and levels of indicated proteins were determined by Western blotting. B. Expression of KLHL12FLAG was induced by doxycycline in wildtype or ΔUSP9X cells, and levels of indicated proteins in lysates were determined by Western. When indicated, the proteasome inhibitor carfilzomib was added. C. USP9X restricts SEC31A ubiquitylation. Ubiquitin conjugates were purified under denaturing conditions in cells depleted of USP9X, as indicated, and modified SEC31 was detected using Western blotting. D. Deletion of USP9X causes a KLHL12-dependent increase in the number of large COPII vesicles marked by KLHL12 (red) and SEC31A (green). DNA was stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar: 10 μm E. Model of regulated CUL3KLHL12assembly. See also Figure S5.

Supporting this notion, we found by denaturing purification of ubiquitin conjugates that SEC31A ubiquitylation was strongly increased in cells depleted of USP9X (Figure 7C). Moreover, as expected from the role of SEC31A monoubiquitylation in COPII vesicle size regulation (Jin et al., 2012; Omari et al., 2018), USP9X deletion led to larger COPII structures upon KLHL12 expression (Figure 7D). Together, these findings suggested that USP9X restricts the activation of CUL3KLHL12 that is the result of PEF1 ubiquitylation. We conclude that monoubiquitylation of PEF1 both stabilizes and activates CUL3KLHL12.

Discussion

The ~300 E3 ligases of the CRL family are responsible for ~20% of ubiquitylation events in human cells and control essential steps in cell division, differentiation, or survival. Their central place in cell signaling requires that CRL complexes must be rapidly assembled whenever and wherever they are needed. Cells partly owe their ability to form new CRLs to the adaptor exchange factor CAND1, which dismantles E3 ligases and thereby keeps the catalytic core of the enzyme open for new substrate-bound adaptors. Here, we show that CRL complex formation also requires enzyme-specific regulators, such as an assembly inhibitor, co-adaptor, and deubiquitylase. The resulting mechanism of regulated CRL assembly couples E3 ligase formation to specific substrate recognition and ubiquitylation (Figure 7E).

Rather than being freely available for CRL assembly, we show that the CUL3KLHL12 adaptor KLHL12 is kept inactive by binding the integral ER membrane protein LNP. When calcium release from the ER signals a need for large COPII structures, the co-adaptor PEF1-ALG2 dissociates KLHL12 from LNP and recruits the target, SEC31A, to assemble substrate-bound CUL3KLHL12. Following initial formation of the CRL, CUL3KLHL12 monoubiquitylates PEF1 to stabilize the enzyme for efficient SEC31A modification. Once CUL3KLHL12 lets go of its target, we anticipate that CAND1 releases KLHL12 from CUL3, USP9X clears PEF1 ubiquitylation, and LNP re-captures KLHL12. We conclude that the assembly of CUL3KLHL12 is a tightly regulated process.

While LNP keeps KLHL12 from CUL3 to prevent premature CRL assembly, it localizes to ER three-way junctions that possess similar membrane topology as budding vesicles (Chen et al., 2015). In addition to inhibiting CUL3KLHL12 assembly, LNP could therefore also establish a KLHL12 pool that is poised for substrate recognition and CRL3 assembly. This apparently paradoxical activity is reminiscent of CAND1, which dismantles CRLs only to support formation of new E3 ligases. Despite its binding to KLHL12, endogenous LNP neither engaged CUL3 nor was it ubiquitylated by CUL3KLHL12. Why LNP-KLHL12 complexes fail to recruit CUL3 is unclear, but it could be related to the observation that LNP engages CAND1 (Kajiho et al., 2019) (Figure 2C, D). We hypothesize that LNP-bound CAND1 dissociates CUL3 that is still bound by KLHL12 to coordinate adaptor capture by LNP with E3 inactivation. If CAND1 were to be released from LNP, this might allow for the ubiquitylation of LNP by CUL3KLHL12 that was recently suggested (Yuniati et al., 2020). LNP is therefore an adaptor-specific inhibitor of CUL3KLHL12 assembly that ensures timely activation of the E3 ligase.

Once LNP has been displaced from KLHL12, PEF1 monoubiquitylation locks CUL3KLHL12 in place. Ubiquitylation might alter PEF1 conformation or solubility to increase its association with CUL3. In addition, as ubiquitin’s hydrophobic patch was needed for its effect on CUL3KLHL12, we anticipate that ubiquitylated PEF1 is specifically bound by the E3 ligase. While unmodified PEF1 requires ALG2 to access CUL3KLHL12, the ubiquitylated co-adaptor could engage the E3 ligase independently of ALG2. PEF1~Ub also bound CUL3 in the absence of calcium, prompting us to speculate that ubiquitylation helps PEF1 access a new site on the E3 ligase. This might shift CUL3KLHL12 from a strictly calcium-dependent E3 ligase to an enzyme that operates at lower calcium levels and thus has more time to ubiquitylate SEC31A than what is provided by calcium pulses. To prevent that PEF1 ubiquitylation inappropriately activates CUL3KLHL12, this modification is kept in check by USP9X, a DUB whose mutation causes craniofacial malformation and autism as also observed upon CUL3 inactivation (Basar et al., 2021; De Rubeis et al., 2014; Jolly et al., 2020; Werner et al., 2015). In addition to the assembly inhibitor LNP, the formation of CUL3KLHL12 complexes is therefore also controlled by reversible co-adaptor monoubiquitylation.

Do these regulatory principles apply to more CRL complexes? Akin to LNP, cryptochrome proteins inhibit CUL4COP1 assembly by competing for access to the accessory subunit DET1 (Rizzini et al., 2019). Other CRL3s show a similar dependency on co-adaptors as CUL3KLHL12 for local ubiquitylation (Aram et al., 2016; Rodriguez-Perez et al., 2021a; Werner et al., 2015). These CRL3s monoubiquitylate substrates that are bound through multivalent interactions: CUL33KBTBD8-β arrestin recognizes, for example, twelve independent motifs in its substrate TCOF1 (Werner et al., 2018), which is reminiscent of the multiple motifs presented by the SEC31A copies in a vesicle coat. Given their similarities to CUL3KLHL12, we suspect that these enzymes are subject to co-adaptor dependent assembly. However, their co-adaptors do not have distinct subunits to mediate E3 ligase formation and substrate binding, respectively, as we have seen for PEF1-ALG2. Revealing a potential co-adaptor role in CRL assembly will therefore require the generation of co-adaptor separation of function mutants in the future.

It is exciting to speculate that other modular enzymes use similar strategies to navigate the assembly of a shared catalytic core with exchangeable adaptors. This might include adaptors of CRL4 whose binding to the E3 ligase core is not determined by CAND1 (Reichermeier et al., 2020), or the AAA-ATPase p97, which relies on ~30 adaptors to recognize its targets in protein complexes (van den Boom and Meyer, 2018). Akin to CRL adaptors that engage the same site on cullins, p97 adaptors compete for access to p97’s N-domain (Buchberger et al., 2015). p97 forms complexes with more than one adaptor at a time, which is reminiscent to the adaptor/co-adaptor pair investigated here (Hanzelmann et al., 2011). Moreover, p97 engages a protein, SVIP, which prevents adaptor recognition, yet recruits p97 to lysosomal membranes and might thus be a functional analog of LNP (Hanzelmann and Schindelin, 2011; Johnson et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2011). p97 complexes could therefore be regulated by similar means as CUL3KLHL12, raising the intriguing possibility that the principles of modular complex assembly described here could extend beyond CRL enzymes.

Limitations of the Study

CUL3 binds ~120 adaptor proteins with BTB domains. How many of these adaptors require co-adaptors for substrate binding is not known. As a consequence, it is not clear in how many cases co-adaptors or assembly inhibitors, such as Lunapark, are employed to control formation of CRL3 complexes. Whether similar mechanisms as those discovered here apply to other CRL families will also need to be investigated in the future.

STAR METHODS

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead contact

All questions and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Michael Rape (mrape@berkeley.edu).

Materials availability

The plasmids and CRISPR-edited cell lines generated in this study are available from the lead contact upon request.

Data and code availability

All data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon request.

This study does not report original code.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

All CRISPR/Cas9-genome-edited cells lines generated in this study were derived from HEK 293T (UC Berkeley Tissue Culture Facility), HEK 293T-Rex dox::KLHL123xFLAG (Jin et al., 2012) and HEK293T KLHL123XFLAG (Mena et al., 2018) parental cell lines listed in the Key Resources Table. The sgRNAs and the procedure used for CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing are listed in the Key Resources Table and detailed in the Methods Section, respectively. The oligos encoding sgRNAs were cloned into pX330 vector which was amplified in E.coli: One Shot Stbl3 Chemically competent cells (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat#:C7373-03)

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Mouse monoclonal anti-beta-ACTIN (clone C4) | MP Biomedicals | Cat#:691001; RRID:AB_2335127 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-HA-Tag (C29F4) | Cell Signaling | Cat#:3724; RRID:AB_10693385 |

| Mouse anti-HA. 11 antibody | BioLegend | Cat#:MMS-101P |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-Flag DYKDDDDK Tag | Cell Signaling | Cat#:S2368 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-Flag DYKDDDDK Tag | Sigma | Cat#:F3165 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-FLAG clone M2 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#:F1804; RRID:AB_262044 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-PEF1/peflin | Abcam | Cat#:ab137127 [EPR9310] |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-ALG2/PDCD6 | Proteintech | Cat#:12303-1-AP; RRID:AB_2162459 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-CUL3 | Bethyl | Cat#:A301-109A; RRID:AB_873023 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-Lunapark | Abcam | Cat#:ab121416; RRID:AB_11129552 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-GAPDH | Cell Signaling | Cat#:14C10; RRID:AB_561053 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-α-tubulin | Calbiochem | Cat#:DM1A |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-SEC31 | BD Transduction Laboratories | Cat#:612350; RRID:AB_399716 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-CAND1 | Cell Signaling | Cat#:8759S (D1F2); RRID:AB_11178669 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-TIP120B (CAND2) | Bethyl | Cat#:A304-046A-T; RRID:AB_2621295 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-USP25 | Abcam | Cat#:ab187156 [ERP15019] |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-SEC13 | Bethyl | Cat#:A303-980A; RRID:AB_2620329 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-KLHL9/13 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. | Cat#:D-4:sc-16686; RRID:AB_2131164 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-KLHL12 | Proteintech | Cat#:14883-1-AP; RRID:AB_10644282 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-KLHL12 | Cell Signaling | Cat#:9406S (2G2); RRID:AB_2797699 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-LNP | Novus | Cat#:NBP1-80637 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-USP9X | Cell Signaling | Cat#:14898S (D4Y7W); RRID:AB_2798640 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-PCNA | Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. | Cat#:PC10:sc-56; RRID:AB_628110 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-KLHL25 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. | Cat#:K20:sc-100774; RRID:AB_1124139 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-ENC1 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. | Cat#:7:sc-135896; RRID:AB_2293504 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti- USP19/ZMYND9 | Bethyl | Cat#:A301-586A |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-Vinculin | Cell Signaling | Cat#:4650S; RRID:AB_10559207 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-KLHL1 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. | Cat#:N-18:sc-79553; RRID:AB_2130725 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-CUL3 generated with Covance | (Mena et al., 2018) | N/A |

| Mouse anti-KBTBD8 antibody produced with Promax | (Werner et al., 2015) | N/A |

| m-IgGk BP-HRP conjugate | Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. | Cat#:sc-516102 |

| HRP Goat-anti-Mouse IgG light-chain specific | Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories | Cat#:115-035-174 |

| Peroxidase AffiniPure Goat Anti-Mouse IgG, Fcγ fragment specific | Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories | Cat#115-035-008; RRID:AB_2313585 |

| HRP Sheep-anti-Mouse IgG | Sigma | Cat#:A5906-1ML |

| HRP Goat-anti-Rabbit IgG | Sigma | Cat#:A6154-5X1ML |

| Donkey-anti-Mouse IgG Alexa Fluor 647 | Invitrogen | Cat#:A31571 |

| Goat-anti-Rabbit IgG Alexa Fluor 568 | Invitrogen | Cat#:A11011 |

| Normal mouse IgG | Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. | Cat#:Sc-2025; RRID:AB_737182 |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| E.coli LOBSTR | Laboratory of Thomas Schwartz | N/A |

| E.coli: One Shot Stbl3 Chemically competent cells | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat#:C7373-03 |

| E. coli: DH5alpha | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat#:18265017 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#:P7626 |

| Calcium Chloride dehydrate | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#:1.02382 |

| Polyethylenimine (PEI), Linear, MW 25000, Transfection Grade | Polysciences | Cat#:23966-1 |

| TCEP (Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride)) | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#:C4706 |

| EGTA | Sigma | Cat#:E3889-25G |

| Dithiothreitol | Invitrogen | Cat#:15508-013 |

| 2-Mercaptoethanol | VWR Life Sciences | Cat#:60-24-2 |

| UREA | FisherChemical | Cat#:U16-3 |

| Iodoacetamide | ACROS | Cat#:144-48-9 |

| 16% Formaldehyde solution | Thermo Scientific | Cat#:28908 |

| Doxycycline hyclate | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#:D9891 |

| Formic Acid (Optima LC/MS) | Fisher Chemical | Cat#:64-18-6 |

| Trichloroacetic acid | Fisher Chemical | Cat#:A322-100 |

| 3xFLAG peptide | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#:F4799 |

| CUL3 peptide (aa 1-19, H2N-MSNLSKGTGSRKDTKMRIRC-amide) | BSI | ID: Cul3_1 peptide Lot #: T8090 |

| PEF1 | (McGourty et al., 2016) | N/A |

| PEF1~Ub | This paper | N/A |

| 6xHiSFLAGALG2 | (McGourty et al., 2016) | N/A |

| 6xHISALG2 | (McGourty et al., 2016) | N/A |

| 6xHISSEC31A/SEC13 | (Stagg et al., 2006) | N/A |

| KLHL126xHis | (Jin et al., 2012) | N/A |

| 9xHISLNPN-C-GGSGGSGFLAG | This paper | N/A |

| CUL3/RBX1 | (Jin et al., 2012) | N/A |

| E1/UBA1 | (Wickliffe et al., 2011) | N/A |

| UBCH5C | (McGourty et al., 2016) | N/A |

| APPBP1/UBA3 (Nedd8 E1) | (McGourty et al., 2016) | N/A |

| UBE2M (Nedd8 E2) | (Scott et al., 2010) | N/A |

| NEDD8 | Boston Biochem | Cat#:UL-812 |

| UBIQUITIN | Boston Biochem | Cat#:U-100H |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| Pierce 660nm Protein Assay Reagent | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat#:22660 |

| Chemiluminescent HRP substrate | Millipore | Cat#:WBKLS0500 |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| HEK 293T | UC Berkeley Cell Culture Facility | N/A |

| HEK 293T-Rex dox::KLHL123xFLAG | (Jin et al., 2012) | N/A |

| HEK 293T LNP3xFLAG | This paper | N/A |

| HEK 293T 3xFLAGALG2 | This paper | N/A |

| HEK293T KLHL123XFLAG | (Mena et al., 2018) | N/A |

| HEK293T KLHL123XFLAG Δpef1 | This paper | N/A |

| HEK293T KLHL123XFLAG Δalg2 | This paper | N/A |

| HEK293T KLHL123XFLAG Δpef1Δalg2 | This paper | N/A |

| HEK293T KLHL123XFLAG Δlnp | This paper | N/A |

| HEK293T KLHL123XFLAG Δlnp/Δpef1 | This paper | N/A |

| HEK293T-Rex dox:: KLHL123XFLAG Δusp9x | This paper | N/A |

| U2-OS | UC Berkeley Cell Culture Facility | N/A |

| SF9 | UC Berkeley Cell Culture Facility | N/A |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| ON-TARGET plus siCONT #3 | Horizon Discovery | D-001810-03 |

| ON-TARGET plus Human siUSP9X – SMARTpool | Horizon Discovery | L-006099-00-0005 |

| ON-TARGET plus Human siUSP9X – Set of 4 | Horizon Discovery | LU-006099-00-0002 |

| ON-TARGET plus Human siUSP19 – SMARTpool | Horizon Discovery | L-006068-00-0005 |

| ON-TARGET plus Human siUSP19 – Set of 4 | Horizon Discovery | LU-006068-00-0002 |

| ON-TARGET plus Human siUSP9X – Individual | Horizon Discovery | J-006099-06-0005 |

| ON-TARGET plus Human siUSP9X – Individual | Horizon Discovery | J-006099-09-0005 |

| ON-TARGET plus Human siUSP25 – SMARTpool | Horizon Discovery | L-006074-00-0005 |

| ON-TARGET plus Human siCUL3 – SMARTpool | Horizon Discovery | L-010224-00-0005 |

| ON-TARGET plus Human siKLHL12 – SMARTpool | Horizon Discovery | L-015890-00-0005 |

| Custom PDCD6 (ALG2) duplex | Horizon Discovery | MCGCD-000009 |

| ATGGCCGCCTACTCTTACCG (sgRNA for ALG2 FLAG-tagging) | This paper | N/A |

| ACTAAGTGGAGAATCTTTGA (sgRNA for LNP FLAG-tagging) | This paper | N/A |

| TGCTGCAGGCGCGGCGCTGC (sgRNA_1 for ALG2 deletion) | This paper | N/A |

| AGGGTCGATAAAGACAGGAG (sgRNA_2 for ALG2 deletion) | This paper | N/A |

| GGTCAACTGCAATTGGTCTT (sgRNA_1 for PEF1 deletion) | This paper | N/A |

| AGTCAGGCCGCATCGATGTC (sgRNA_2 for PEF1 deletion) | This paper | N/A |

| AAGTTTGAAATTTACTAACA (sgRNA_1 for LNP deletion) | This paper | N/A |

| TAAGACTCTCTAGTCAGAAA (sgRNA_2 for LNP deletion) | This paper | N/A |

| CTGTAGGGTTAGTCGAATTA (sgRNA_1 for USP9X deletion) | This paper | N/A |

| ATGGGCCGAGCACACACCTG (sgRNA_2 for USP9X deletion) | This paper | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pCS2+ HALNP | This paper | N/A |

| pCS2+ HALNP ( PGGPP to AAAAA) | This paper | N/A |

| pCS2+ HALNPC (aa 100-428) | This paper | N/A |

| pCS2+ HALNPN (aa 1-45) | This paper | N/A |

| pCS2+ HALNPN-C (Δ46-99) | This paper | N/A |

| pCS2+ LNP-sfGFP | This paper | N/A |

| pCS2+ 3xHAPEF1 | (McGourty et al., 2016) | N/A |

| pCS2+ 3xHAPEF1 (K3R) (K137R/K165R/K167R) | (McGourty et al., 2016) | N/A |

| pCS2+ 3xHAPEF1 (K7R) (all K to R) | (McGourty et al., 2016) | N/A |

| pCS2+ 3xHAPEF1 (PGAPP to AAAAA) | This paper | N/A |

| pCS2+ FLAGPEF1 | This paper | N/A |

| pCS2+ FLAGPEF1~UB | This paper | N/A |

| pCS2+ FLAGPEF1~UB (I44A) | This paper | N/A |

| pCS2+ FLAGPEF1~UB* (UB contains duplicated DQQRLAFAGK in addition to I44A mutation) | This paper | N/A |

| pCS2+ HAPEF1~UB | This paper | N/A |

| pCS2+ HAPEF1-UB (I44A) | This paper | N/A |

| pCS2+ HASEC31A | (McGourty et al., 2016) | N/A |

| pCS2+ SEC13 | (McGourty et al., 2016) | N/A |

| pCS2+ KLHL12FLAG | (McGourty et al., 2016) | N/A |

| pCS2+ KLHL12FLAG (ΔSUB) (FG289AA) | (McGourty et al., 2016) | N/A |

| pCS2+ KLHL12FLAG (C3) (LSE67AAA) | (McGourty et al., 2016) | N/A |

| pCS2+ KLHL12FLAG (ΔAMF) (AMF61DDA) | (McGourty et al., 2016) | N/A |

| pCS2+ KLHL12FLAG (L20D/M23D/L26D/I49K) | (McGourty et al., 2016) | N/A |

| pCS2+ KLHL41(1-131)-KLHL12(132-Cterm)FLAG | (Mena et al., 2018) | N/A |

| pCS2+ KLHL12(1-131)-KLHL41(132-Cterm)FLAG | (Mena et al., 2018) | N/A |

| pCMV 3xFLAGUSP9X | This paper | N/A |

| pCMV 3xFLAGUSP9X (C1566A) | This paper | N/A |

| pET28 9xHISLNP (Δ46-99)-GGSGGSGFLAG | This paper | N/A |

| pFastbac1 6xHISMBP-PEF1 | (McGourty et al., 2016) | N/A |

| pFastbac1 6xHISMBP-PEF1~UB | This paper | N/A |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Fiji | (Schindelin et al., 2012) | RRID:SCR_002285 |

| Metamorph Advanced | Molecular Devices | RRID:SCR_002368 |

| CompPASS | (Huttlin et al., 2017) | N/A |

| ImageJ | (Schindelin et al., 2012) | PRID:SCR_003070 |

| Other | ||

| Bovine Serum Albumin | Sigma | Cat#:A8806-5G |

| Lipofectamine RNAiMAX | ThermoFischer Scientific | Cat#:13778030 |

| TransIT-293 | Mirus | Cat#:MIR2700 |

| Lipofectamine 3000 | ThermoFischer Scientific | Cat#:L3000008 |

| Complete, EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail tablets from Roche | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#:11873580001 |

| Hoechst 33342 | AnaSpec | Cat#:83218 |

| Opti-MEM (1X) Reduced Serum Medium | Gibco | Cat#:31985-070 |

| DMEM (1X) +GlutaMAX™-I | Gibco | Cat#:51985091 |

| Trypsin-EDTA (0.25%) | Gibco | Cat#:25200056 |

| Fetal Bovine Serum | VWR LifeScience | Cat#:97068-107 |

| Non-essential amino acid solution | UC Berkeley Cell Culture Facility | N/A |

| Ni-NTA | QIAGEN | Cat#:30210 |

| Lipofectamine RNAiMAX | ThermoFisher | Cat#:13778150 |

| ANTI-FLAG® M2 Affinity Agarose Gel slurry | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#:CA2220 |

| Protein G-Agarose | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#:11243233001 |

| TEV protease | UCB QB3 MacroLab | N/A |

| Carfilzomib | Selleck Chemical LLC | Cat#:PR-171 |

U2-OS cells used for co-localization studies were obtained from UC Berkeley Tissue Culture Facility and transfected with mammalian expression vectors as described in the Methods section.

All mammalian expression vectors used in this study were amplified in E. coli: DH5alpha (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat#: 18265017) or E.coli: One Shot Stbl3 Chemically competent cells (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat#:C7373-03).

Recombinant protein for in vitro assays was generated using E.coli LOBSTR (laboratory of Thomas Schwartz) and baculovirus expression system in SF9 insect cells (UC Berkeley Tissue Culture Facility).

METHODS DETAILS

Cell Culture

Wild-type and engineered HEK293T expressing endogenously FLAG-tagged KLHL12, ALG2, or LNP, and HEK293T-REx cell lines harboring doxycycline-inducible promoter for expression of KLHL123XFLAG, were maintained in DMEM (1X) +GlutaMAX™-I (Gibco) supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) (VWR LifeScience). HEK293T-REx cells were maintained in DMEM with certified tetracycline free FBS. For passaging, the cells were washed at no higher than 90% confluence with DPBS (1X) (Gibco) and trypsinized with 0.25% Trypsin-EDTA (Gibco). The cells were frozen in FBS supplemented with 10% DMSO and maintained at −80°C and −150°C. U2-OS cells were cultured in DMEM (1X) +GlutaMAX™-I (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS and non-essential amino acids (UC Berkeley Cell Cuture Facility).

Transfections

HEK293T cells were transfected with plasmid DNA for ectopic expression using polyethylenimine (PEI) or TransIT-293 transfection reagent (Mirus) at a 3:1 transfection reagent to DNA ratio. Depending on the assays, transfections were performed in 15 cm, 10 cm, 6-well, or 12-well plates. HEK293T cells were transfected with siRNAs at 10 to 30 nM using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (ThermoFisher Scientific). All transfection mixtures were prepared in Opti-MEM Reduced Serum Medium (Gibco). Cells were typically harvested 24 to 48 hours post-transfection. Transfection of U2OS cells with KLHL123XFLAG and LNP-sfGFP was performed using Lipofectamine 3000 reagent according to the manufacturer’s protocol (ThermoFisher Scientific).

Generating CRISPR/Cas9 genome-edited cell lines

All cell lines used in this publication were generated from HEK293T cells or HEK293T-REx cells allowing for doxycycline-inducible expression of KLHL123XFLAG. The guide RNA sequences were designed using the on-line resource provided by the Zhang Lab at MIT (http://crispr.mit.edu). The sequences of the genes for editing were obtained from the UCSC Genome browser. The oligonucleotides for guide RNAs (listed in the Key Resources Table) and their complementary sequences were ordered from IDT, annealed, and cloned into a pX330 vector according to the protocol at https://benchling.com/protocols/5DmqRd/crispr-mediated-gene-disruption-in-ch12f3-2-cells/sbs. For CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene disruption, HEK293T cells cultured in a 6-well plate at 50% confluence were transfected using TransIT-293 transfection reagent (Mirus) with two pX330 plasmids (2 μg of total DNA) each encoding a guide RNA for site-specific gene cutting. The guides for cutting were designed to create deletions and introduce open reading frame (ORF) shifts for gene disruption. Three days post-transfection, a sample of transfected cells was treated with DNA extraction solution (QuickExtract, Epicentre) and editing was assessed by PCR amplification of the sequence of interest using specific PCR primers. Clonal selection was performed by seeding the cells into 96-well plates at one cell per well density, allowing the single cells to expand, and checking editing by PCR. The clones were validated using Western blotting with specific antibodies.

For CRISPR/Cas9-mediated tagging of endogenous KLHL12, LNP, ALG2, or PEF1, a similar approach was used with modifications. The cells were transfected with one pX330 plasmid and a 200-nt long donor template encoding the triple FLAG tag sequence (66 nt) flanked with 134 nt long homology arms. The clones were validated using Western blotting, mass spectrometry, and sequencing of the PCR amplified edited region.

Guide RNAs for CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing

Single RNA guides were used for constructing 3xFLAGALG2 (ATGGCCGCCTACTCTTACCG) and LNP3xFLAG (ACTAAGTGGAGAATCTTTGA) HEK293T cell lines. The KLHL123xFLAG HEK293T cell line is described in (Mena et al., 2018). A pair of RNA guides was used to disrupt the following genes in HEK293T cells or HEK293T-REx cell lines expressing doxycycline inducible KLHL123xFLAG: ALG2 (TGCTGCAGGCGCGGCGCTGC, AGGGTCGATAAAGACAGGAG), PEF1 (GGTCAACTGCAATTGGTCTT, AGTCAGGCCGCATCGATGTC), LNP (AAGTTTGAAATTTACTAACA, TAAGACTCTCTAGTCAGAAA), USP9X (CTGTAGGGTTAGTCGAATTA, ATGGGCCGAGCACACACCTG). Doubly and triply edited cell lines were generated sequentially using the procedure described above.

siRNAs

The following siRNAs were obtained from Dharmacon: ON-TARGETplus Human USP9X siRNA – SMARTpool and Set of 4 Upgrade (AGAAAUCGCUGGUAUAAAU, ACACGAUGCUUUAGAAAUUU, GUACGACGAUGUAUUCUCA, GAAAUAACUUCCUACCGAA), ON-TARGETplus Human USP19 siRNA – SMARTpool and Set of 4 Upgrade (GAGGACACCACUAGUAAGA, UGGCGGAGGUAAUUAAGAA, UCAAGAAUAGACUCGUAUGA, CAGAGUUGUUGCUCGAUUG), ON-TARGETplus Human USP9X siRNA – Individual (AGAAAUCGCUGGUAUAAAU, GAAAUAACUUCCUACCGAA), ON-TARGETplus Human USP25 siRNA – SMARTpool (ACAAGUUCCUUAUCGAUUA, UGAAAGGUGUCACAACAUA, UAAGGAUGCUUUCAAAUCA), Custom PDCD6 duplex (Sense: CAUUGUGCCAUGAGGUAAAUU, Antisense (UUUACCUCAUGGCACAAUGUU), ON-TARGETplus Human CAND1 siRNA – SMARTpool (GACUUUAGGUUUAUGGCUA, CGUGCAACAUGUACAACUA, CAACAAGAACCUACAUACA, CAUAACAAGCCAUCAUUAA), ON-TARGETplus Human CAND2 siRNA – SMARTpool (ACGAGGACAGCGAGCGCAA, GCACCCUGAUCCAAUGUUU, AGAACGGUGAGGUGCAGAA, UGUCGGAGUUGCAGAAGGA), ON-TARGETplus Human CUL3 siRNA – SMARTpool (GAAGGAAUGUUUAGGGAUA, GAGAUCAAGUUGUACGUUA, GAAAGUAGACGACGACAGA, GCACAUGAAGACUAUAGUA), ON-TARGETplus Human KLHL12 siRNA – SMARTpool (GGAAGGUGCCGGACUCGUAUU, GCAGGGAUCUGGUUGAUGAUU, GGACUAAUGUUACACCAAUUU, UGACAAAUACUCAUGCUAAUU), ON-TARGETplus Control siRNA #3 (UAGCGACUAAACACAUCAAUU)

Recombinant DNA

pCS2+- and pCMV-based mammalian expression plasmids with engineered Fse1 and Asc1 restriction sites for cloning were used to construct plasmids for transfection of mammalian cell lines. The pCS2+ vector with the following inserts was transiently introduced into HEK293T cells for ectopic expression: 3xHAPEF1, HAPEF1~UB, FLAGPEF1, FLAGPEF1~UB, HALNP, HALNPC, HALNPN-C, HALNPN 6xHISUbiquitin, Sec13, HASEC31, LNP-sfGFP. The PEF1~UB genetic fusion was generated by fusing N-terminus of ubiquitin to the C-terminus of PEF1 via a flexible GVDGGGGGG linker. The two C-terminal Gly residue of the ubiquitin moiety were removed to prevent formation of the isopeptide bond. The same ORF was cloned into pFastBac1 vector for Bac-to-Bac baculovirus expression system and purification of the fusion from SF9 insect cells. The N-terminally FLAG-tagged USP9X ORF was cloned into a pCMV vector. pCS2+ vectors containing fusion inserts were generated by PCR ligation of two PCR amplified inserts with complementary sequences followed by ligation into the vector backbone. Deletion of the sequence encoding two transmembrane domains of LNP, mutation of the conserved PGXPP to AAAAA motif in LNP and PEF1 ORFs, the I44A mutation in Ubiquitin, K3R (K137R/K165R/K167R) and K7R mutations in PEF1, and C1566A mutation in USP9X were introduced using site-directed mutagenesis followed by DpnI digestion of the parental plasmid. Point mutants of KLHL12 in pCS2-KLHL12FLAG (ΔSUB (FG289AA), C3 (LSE67AAA), and dimerization defective KLHL12 (L20D/M23D/L26D/I49K)) were previously described (Jin et al., 2012, McGourty et al., 2016). The construction of pCS2-KLHL41BTB/BACK-KLHL12KELCH-FLAG plasmid is described in Mena et al., 2018.

9xHISLNPN-C-GGSGGSGFLAG was cloned into pET28 vector for bacterial expression. The bacterial and SF9 ES insect cell expression vectors to produce recombinant protein for in vitro ubiquitylation and binding assays were previously described (Jin et al., 2012, McGourty et al., 2016). pX330 was obtained from Addgene.

Antibodies

The following antibodies were used in this study: PEF1/peflin (Abcam, ab137127 [EPR9310], rabbit monoclonal), ALG2/PDCD6 (Proteintech, 12303-1-AP, rabbit polyclonal), ALG2/PDCD6 (Abcam, ab133326 [EPR3260], rabbit monoclonal), CUL3 (Bethyl, A301-109A, rabbit polyclonal), Lunapark (Abcam, ab121416, rabbit polyclonal), HA (Cell Signaling, 3724S (C29F4), rabbit monoclonal), HA.11 (BioLegend, MMS-101P, mouse), FLAG (Sigma, F7425, rabbit polyclonal), β-actin (MP Biomedicals, clone 4, mouse monoclonal), GAPDH (Cell Signaling 14C10, rabbit monoclonal), α-tubulin (Calbiochem, DM1A, mouse monoclonal), SEC31 (BD Transduction Laboratories, 612350, mouse monoclonal), CAND1 (Cell Signaling, 8759S (D1F2), rabbit monoclonal), TIP120B (Bethyl, A304-046A-T, rabbit polyclonal), USP25 (Abcam, ab187156 [ERP15019] rabbit polyclonal), SEC13 (Bethyl, A303-980A, rabbit polyclonal), KLHL9/13 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., D-4:sc-16686), KLHL12 (Proteintech, 14883-1-AP, rabbit polyclonal), FLAG (Cell signaling, 2368S), KLHL12 (Cell Signaling, 9406S (2G2) mouse monoclonal), LNP (Novus, NBP1-80637, rabbit polyclonal), USP9X (Cell Signaling 14898S (D4Y7W), rabbit monoclonal), PCNA (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., PC10:sc-56, mouse monoclonal), KLHL25 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., K20:sc-100774, mouse monoclonal), ENC1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., 7:sc-135896, mouse monoclonal), USP19/ZMYND9 (Bethyl, A301-586A, rabbit), Vinculin (Cell Signaling, 4650S, rabbit), KLHL1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., N-18:sc-79553, rabbit polyclonal), CUL3 (mouse monoclonal antibody generated with Covance (Mena et al., 2018)), KBTBD8 (mouse produced with Promab (Werner, et al., 2015). m-IgGk BP-HRP conjugate (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-516102), HRP Goat-anti-Mouse IgG light-chain specific (Jackson Immunoresearch, 115-035-174), HRP Sheep-anti-Mouse IgG (Sigma, A5906-1ML), and HRP Goat-anti-Rabbit IgG (Sigma, A6154-5X1ML) secondary antibodies were used for Westerns. Donkey-anti-Mouse Alexa488 and Goat-anti-Rabbit Alexa568 (Invitrogen) secondary antibodies were used for immunofluorescence.

Recombinant proteins

Recombinant LNP was produced by expressing 9xHISLNPN-C-GGSGGSGFLAG from pET28 vector in LOBSTR E. coli. Fifty mL of LB with 100 μg/mL of kanamycin and 35 μg/mL of chloramphenicol was inoculated with a single colony and allowed to grow overnight. 1.5L of LB containing kanamycin and chloramphenicol was inoculated with 20 mL of the overnight culture and allowed to reach O.D. 0.6. The flasks were cooled in ice to 12°C and induced with 0.25 mM IPTG. The cells were incubated with vigorous shaking at 12°C for 18 hours and harvested at the final O.D of about 1.2. The cells were spun at 4000 rpm 4°C for 15 min in Sorvall RC3B+ centrifuge (Thermo Scientific) and re-suspended in 25 mL of cold 1X PBS per one litter of culture. The cells were spun down, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C.

For purification, 5 mL of cell volume was re-suspended in 40 mL of Lysis Buffer (500 mM NaCl, 50 mM KHEPES pH 8.0, 10% glycerol, 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 1mg/mL Lysozyme (L6876-10G, Sigma), 1 mM PMSF, and two dissolved protease inhibitor cocktail tablets per 100 mL of Lysis Buffer (Complete EDTA-free, Roche)). The mixture was incubated at 4°C for 15 min and sonicated using a macrotip probe (Qsonica, LLC) with amplitude of 65, 10 sec on/90 sec on cycles for 3 min on ice with frequent mixing. The cells were spun at 18,000 rpm, 4°C for 35 min in Fiberlite F21-8x50y rotor (Sorvall Lynx 4000 Centrifuge) and the cleared lysate was supplemented with 15 mM Imidazole (4 M stock with pH adjusted to 7.5 with HCl). The lysate was incubated at 4°C with 1 mL of Ni-NTA resin (Qiagen) (washed three times with water and equilibrated three times with Wash buffer (500 mM NaCl, 50 mM KHEPES pH 8.0, 10% glycerol, 10 mM Imidazole) before mixing with the lysate) on a rotary shaker for two hours. The mixture was poured into an Econo-Pac disposable chromatography column (BioRad) and the resin was washed by gravity in the presence of 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol with 20 mL of the wash buffer/15 mM Imidazole, 20 mL of the wash buffer/25 mM Imidazole, and 15 mL of the wash buffer/40 mM Imidazoled. The protein was eluted in three two-mL fractions containing 100 mM, 300 mM, and 600 mM Imidazole, respectively. The fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250. Fractions deemed sufficiently pure were combined, concentrated in a 30,000 MWCO concentrator (Amicon Ultra) to 2 mL, and dialyzed against 4L of dialysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM KHEPES pH 7.5, 10% Glycerol, 1 mM DTT) for 18 hours. The protein was frozen in 50 mL aliquots in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C.

Purification of 6xHISSec31A/Sec13, 6xHisFLAGALG2, KLHL12HIS, CUL3, and PEF1 used in binding and in vitro ubiquitylation assays were previously described (McGourty et al., 2016; Jin et al., 2012; Eletr et al., 2005). Purification of PEF1~UB genetic fusion was purified from SF9 insect cells exactly as PEF1. Purification of recombinant proteins for in vitro CUL3 neddylation and SEC31/PEF1 ubiquitylation are described in McGourty et al., 2016, Jin et al., 2012, and Wickliffe et al., 2011. Recombinant Ubiquitin (U-100H) and Nedd8 (UL-812) were purchased from Boston Biochem.

Large-scale immunoprecipitation and mass spectrometry

CRISPR/Cas9-edited HEK293T cell lines expressing endogenous FLAG-tagged proteins were seeded into 20 to 40 15 cm plates per condition and grown to confluence before harvesting. Unmodified HEK293T were seeded into 15 cm plates at 4 x 106 cells per plate density, transfected on the next day with 1 to 2.5 μg of recombinant DNA at approximately 50% confluence and harvested 48 hours post-transfection. The cells were scraped into the medium, spun down in 0.5L conical bottles in a Sorvall RC 3BP+ centrifuge at 1200 rpm for 5 min, and washed once with DPBS. The cell pellet was frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C.

The cells were lysed in 5 volumes of immunoprecipitation lysis buffer (IPB) containing 50 mM KHEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% NP-40, and two EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail tablets (Roche) per 50 mL of the IPB. For LNP3xFLAG immunoprecipitation, the IPB buffer contained 0.5% NP-40. The cells were incubated on a rotary shaker at 4°C for 1 hour and spun in a Sorvall RC 3BP+ centrifuge (Thermo Scientific) at 4°C 1500g for 5 min. The supernatant was further spun in Sorvall Lynx 4000 centrifuge (Thermo Scientific) using Fiberlite F21-8x50y rotor at 4°C 18,000 rpm for 30 min. An aliquot of the cleared lysate was mixed with 2X Laemmli/6M Urea/2-ME buffer for SDS-PAGE followed with Colloidal Coomassie staining or Western blot analysis and the rest of supernatant was mixed with 100 to 200 uL of the M2 anti-FLAG affinity agarose gel (Sigma, A2220-10mL) (washed three times with 1 mL of IPB buffer per wash prior to mixing with the sample). The mixture was incubated on a rotary shaker at 4°C for 2 hours, spun at 4°C 2000 rpm 5 min in Sorvall Legent RT+ centrifuge (Thermo Scientific), and the supernatant was carefully aspirated. The resin was transferred to a 1.5 mL eppendorf tube in 1 mL of the IPB and further washed six times with 1 mL of IPB per wash. The last wash was removed completely using a squeezed gel loading tip and the bound FLAG-tagged protein was eluted in three 200 uL aliquots of DPBS containing 0.2 mg/mL of 3XFLAG peptide (Millipore, Cat#F4799) and 0.2% TRITON X100 with incubation in a thermomixer at 30°C 900 rpm for 20 min per elution. The last eluate was removed completely using a squeezed gel loading tip and the combined eluate was spun in tabletop eppendofr 5424R centrifuge at 2000 rpm for 2.5 min to pellet any contaminating resin. The supernatant was collected and an aliquot was mixed with 2X Laemmli/6M Urea/2-Mercaptoethanol (2-ME) gel loading buffer for SDS-PAGE/Colloidal Coomasie staining or Western blot analysis. The rest of the cleared eluate was mixed with 100% Trichloroacetic acid (Fisher Chemical) (23% final TCA) and incubated overnight on ice to ensure complete protein precipitation.

The precipitated protein was spun at 4°C 15,000 rpm for 20 min in centrifuge, the supernatant was removed and the precipitated protein was washed three times in 90% acetone containing 0.01N HCL with 1 mL per wash. The pellet was dried for several hours on air and the dried protein was dissolved in 84 uL of 100 mM TRIS-HCl pH 8.5 containing 8M urea (Fisher Chemical) using a bath sonicator. The dissolved protein was treated with 5 mM TCEP (Sigma) for 15 min at RT and then alkylated for 20 min with 10 mM iodoacetamide (Sigma) in the dark at RT. The mixture was diluted four-fold with 100 mM TRIS-HCl pH 8.5 and trypsinized (0.5 mg/mL Trypsin, Fisher) at 37°C overnight in a thermomixer with gentle shaking. The digested protein was supplemented with Formic acid (Optima LC/MS) (Fisher Chemical) at the final concentration of 2% and submitted to Vincent J. Coates Proteomics/Mass Spectrometry Laboratory at UC Berkeley where the samples were analyzed with multi-dimensional protein identification technology (MuDPIT). Analysis of the mass spectrometry results was performed by comparing the results to approximately 150 FLAG immunoprecipitations of unrelated proteins using the CompPASS software suite as previously described (Huttlin et al., 2015; Sowa et al., 2009).

Small-scale immunoprecipitation and Western blot analysis

Immunoprecipitation of endogenous protein from original HEK293T cells or endogenous FLAG-tagged protein from CRISPR/Cas9-edited HEK293T cell lines was performed from two or three 15 cm fully confluent plates. For immunoprecipitation of transiently expressed FLAG-tagged protein, HEK293T cells were seeded onto into one 15- or 10-cm plate and transfected on the next day with 0.5 to 2 μg of recombinant DNA. For transient knockdown of USP9X and ALG2, the cells were treated with corresponding siRNAs at the final concentration of 30 nM for 48 hours. To examine the effect of Ca2+ on the CUL3KLHL12 ligase assembly and activity, the cells were incubated overnight in 10 mM CaCl2 or 5 mM EGTA. The cells were harvested 36 to 48 hours post-transfection by removing the medium and collecting the cells into DPBS. The cells were either frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C or lysed right away for immunoprecipitation. The cells collected from three confluent 15-cm plates were re-suspended in 1.2 mL of IPB/0.1% NP-40. Depending on the cell pellet size, 500 to 750 uL of IPB/0.1% NP-40 were used to lyse cells collected from one 10- or 15-cm plate. The lysate was incubated at 4°C on a rotary shaker for one hour, spun at 5000 rpm for 5 min, and the collected supernatant was spun at 15,000 rpm for 25 min in tabletop eppendorf 5424R centrifuge. The total protein in the cleared lysate across the conditions was normalized by diluting the lysate ten-fold in DPBS and measuring absorbance at 280 nm. After equalizing both the total protein concentration and the lysate volume, an aliquot was mixed with 2X Laemmli/6M Urea/2-ME buffer for Western blot analysis of the input and the lysate was mixed with 20 to 30 uL of anti-FLAG affinity agarose gel (Sigma) (washed three times with 400 μL of IPB/0.1% NP-40 buffer per wash prior to mixing with the sample). For immunoprecipitation of endogenous CUL3 or SEC31 protein, the lysate was mixed with Protein G-Agarose resin (Sigma-Aldrich, Ref: 11719416001) and either mouse monoclonal anti-CUL3 antibody (Mena et al., 2018) or mouse monoclonal anti-SEC31 antibody (BD Transduction Laboratories, 612350), respectively, used at 5 μg/mL final concentration. For the control, sample normal mouse IgG (sc-2025, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) was mixed with the cleared lysate. The samples were incubated at 4°C on a rotary shaker for two hours, and the resin was washed six times with 700 uL of IPB/0.1% NP-40 per wash. The last wash was removed completely and the resin was either re-suspended in 100 uL of 2X Laemmli/6M Urea/2-ME gel loading buffer or the protein was first eluted with 3XFLAG or CUL3 peptide and then mixed with 2X Laemmli/6M Urea/2-ME loading buffer.

Prior to SDS-PAGE, the samples were incubated at 65°C with shaking. The samples were typically loaded onto 11% acrylamide gel and protein was subsequently transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane (Thermo Scientific, Ref: 88018). To reduce non-specific signal, the membrane was incubated in blocking buffer (phosphate buffer saline containing 0.1% TWEEN (PBST) and 2% non-fat milk powder for one hour at RT, incubated with primary antibodies at 4°C overnight in the blocking buffer, washed three times with PBST over the course of 30 min, incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies in blocking buffer for one to two hours at RT. The membranes were then washed four times with PBST over the course of 40 min and treated with chemiluminescent HRP substrate (Millipore, Cat #: WBKLS0500). The chemiluminescence signal was captured on ProSignal™ blotting film (Prometheus, Cat # 30-810L) and visualized using an SRX-101A developer (Konica Minolta).

Subcellular fractionation

HEK293T cells were cultured in 10 cm plates to ~ 90% confluence, washed with DPBS, trypsinized, and collected in DMEM (1X) +GlutaMAX™-I (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS to quench trypsin. The cells were spun down and washed with 10 mL of DPBS. Following centrifugation, the cell pellet was re-suspended in 10 mL of DPBS and 1 mL of the cell suspension was used for fractionation. Briefly, the cells were centrifuged at 100 RCF 4°C, re-suspended in 350 μL of 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM KHEPES pH 7.5, 25 μg/mL digitonin (Sigma-Aldrich, 11024-24-1) and incubated on a rotary shaker at 4°C for 10 minutes. The samples were then spun at 2000 RCF 4°C for 5 minutes and the supernatant was mixed with an equal volume of 2X Laemmli/6M Ureβ-mercaptoethanol. The pellet was then washed by re-suspending in 1 mL of DPBS at 4°C and the membranous fraction was pelleted at 2000 RCF 4°C for 5 minutes. The supernatant was apirated and the pellet was re-suspended in 300 μL of 2X Laemmli/6M Ureβ-mercaptoethanol. The samples were heated to 65°C for 20 min, resolved on a denaturing gel, and analyzed by Western blotting using specific antibodies.

In vitro LNP exchange reaction