Abstract

Objective:

We aimed to develop an ecological momentary assessment (EMA) measure and sampling protocol to assess the near-term impact of experiences with social media use (SMU) that are associated with risk and protective factors for adolescent suicide.

Methods:

To develop the EMA measure, we consulted literature reviews and conducted focus groups with the target population, adolescents at risk for suicide. Subsequently, we refined the measure through interviews with experts and cognitive interviews with adolescents, through which we explored adolescents’ thought processes as they considered questions and response options. Data were recorded, transcribed, and analyzed using thematic analysis.

Results:

The initial measure had 37 items assessing a range of harmful and beneficial aspects of SMU. Through expert and cognitive interviews, we refined the measure to 4 pathways assessing positive and negative experiences with SMU as well as positive and negative in-person interactions. Each pathway included a maximum of 11 items, as well as 2 items pertaining to SMU at night-time to be assessed once daily. Acceptable targets the EMA measure’s sampling protocol included a 10-day data collection window with text message-based prompts to complete the measure triggered 2–4 times daily.

Conclusions:

By assessing a range of risk and protective factors for youth suicide, while using methods to reduce participant burden, we established content validity for the EMA measure and acceptability for the sampling protocol among youth at high risk of suicide.

1.1. Introduction

The suicide rate in the United States has increased 33% from 1999 to 2018, now the second-leading cause of death among adolescents (Hedegaard, Curtin, & Warner, 2018). This period dovetails with a trend of rapid proliferation in daily use of social media among adolescents (Anderson & Jiang, 2018; Rideout & Michael, 2019), which has left many to question the influence of social media use (SMU) on adolescent suicidal risk. This influence has been explored through systematic reviews, which have observed a potential relationship between SMU and key risk factors, as well as protective factors, for adolescent suicide (Dyson et al., 2016; Marchant et al., 2017). However, studies to date investigating this relationship are predominantly descriptive and cross-sectional, which limits capacity to draw causal inferences or to consider person-specific effects. Research on related mental health and well-being outcomes, has shown SMU in and of itself is responsible for only a small portion of the variability in adolescents’ well-being (Orben & Przybylski, 2019a, 2019b), although within-person differences are estimated to vary considerably (Beyens, Pouwels, van, Keijsers, & Valkenburg, 2020). Rather, frequent SMU is estimated to have an indirect effect on well-being, disrupting activities that have a positive impact on mental health, such as sleep and physical activity, while increasing exposure to negative or harmful content like cyberbullying (Viner et al., 2019). While correlated with poor well-being and psychiatric disorders (Hawton & van Heeringen, 2009; Sisask, Varnik, Kolves, Konstabel, & Wasserman, 2008), suicide is a distinct and complex problem influenced by a range of risk and protective factors (Turecki & Brent, 2016). This suggests need for further study to explicate social media’s influence on adolescents’ risk for suicide.

Investigating within-person variations in social media’s influence could be especially important for understanding unique vulnerabilities among adolescents who are at high risk for suicide, i.e., youth who have experienced recent suicidal thoughts or behaviors. Adolescents who are depressed or suicidal have distinct patterns of SMU (Dyson et al., 2016; Seabrook, Kern, & Rickard, 2016). This includes using social media in ways that could offer benefit, such as a means for distraction from depressed mood states or to reach out to others for support and connection (Dyson et al., 2016; Radovic, Gmelin, Stein, & Miller, 2017), as well use that could contribute to risk. Adolescents who have depression or suicidal thoughts are more likely to be exposed to harmful online content, such as self-harm behaviors or cyberbullying, and to engage in problematic internet use (SMU that inhibits daily life) (Spada, 2014) than youth who are not depressed or suicidal (Biernesser et al., 2020; Dyson et al., 2016; Marchant et al., 2017; Selkie, Fales, & Moreno, 2016). Understanding proximal relationships between SMU and key risk and protective factors for suicide, particularly among adolescents at high risk, could provide critical insights for approaches to youth suicide prevention and treatment.

Ecological momentary Assessment (EMA) presents an opportunity for extending longitudinal study to address important research gaps in the literature evaluating social media’s influence on risk and protective factors for adolescent suicide. EMA uses repeated sampling of subjects’ experiences to develop a fine-grained understanding of behavioral phenomena. Assessment in real-time is a defining feature of EMA, which mitigates recall bias (Shiffman, Stone, & Hufford, 2008). This methodology has long been used to assess children’s use of media (Vandewater & Lee, 2009), and it has been used in several studies exploring fluctuations in suicidal thoughts and well-known risk factors for suicide (e.g., hopelessness, burdensomeness, and loneliness) (Hallensleben et al., 2018; Kleiman, Liu, & Riskind, 2014; Nock, Prinstein, & Sterba, 2009). However, EMA has not yet used to explore suicidal risk within the context of adolescents’ SMU. EMA could offer significant value by shedding light on the sequence by which youth are exposed to harmful or beneficial online content and subsequently experience changes in suicidal risk.

As a critical first step toward explicating the short-term impact of SMU on adolescent suicidal risk and protective factors, we aimed to develop an EMA measure that could be used acceptably among adolescents at high risk for suicide. Shiffman and colleagues (Shiffman et al., 2008) outline a number of considerations toward the development of EMA measures. First, they recommend identifying, testing, and refining a set of items to assure adequate comprehension and minimize participant burden, which is especially important for pediatric populations (Shiffman et al., 2008). Second, they recommend developing a protocol that maximizes compliance with the measure while minimizing reactivity, referring to the potential for a behavior to be impacted by the act of assessing it (Shiffman et al., 2008). This manuscript describes the iterative development of an EMA measure and sampling protocol aimed to assess the impact of SMU on risk and protective factors for suicide, focusing particularly on adolescents at high risk.

1.2. Materials and Methods

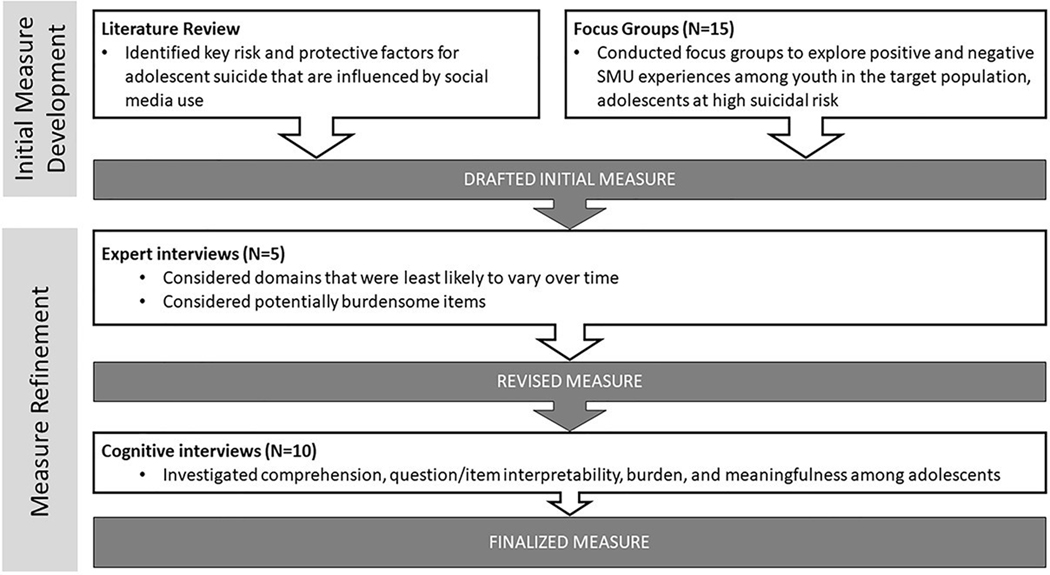

Following recommendations for the development of EMA measures (Shiffman et al., 2008), we consulted literature reviews and engaged in qualitative data collection with the target population (youth at high risk for suicide) to develop the measure, and subsequently refined the measure based on interviews with experts and recently suicidal youth (see Figure 1). This study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board.

Figure 1.

Measure Devlopment and Refinement Proess

Drafting the EMA measure

The EMA measure was informed by literature review and focus groups. First, we identified factors within the literature that convey suicidal risk or protection associated with the use of social media. The primary data sources were two systematic reviews (Dyson et al., 2016; Marchant et al., 2017) and a systematized narrative review (Biernesser et al., 2020) that focused on social media’s influence on suicidal outcomes among adolescents.

Secondly, we performed three focus groups that explored experiences with SMU of adolescents ages 13 to 18 (N=15) who experienced recent suicidal thoughts or behaviors recruited from an intensive outpatient program between January and July 2018. Adolescents were approached by their treating clinician who explored their interest in participating, after which a researcher explained the study. Adolescents provided assent and parents provided consent. Focus groups were conducted in-person at research staff offices by experienced facilitators (CB and JZ) and were approximately two hours. Data collection focused on participants’ positive and negative experiences on social media and perceptions toward the impact of SMU on adolescents’ mental health and suicidal risk. Focus groups were recorded, transcribed verbatim, and inductively coded by two experienced qualitative analysts (CB and JZ) using thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Focus groups themes relating to positive and negative SMU experiences were triangulated with risk and protective factors identified from the literature reviews to hone a list of domains for the initial EMA measure.

Refining the EMA measure and sampling protocol: expert and cognitive interviews

Consistent with recommendations for measure development (Groves et al., 2009), we recruited five experts to provide feedback on the drafted EMA measure. Their expertise included adolescent mental health (all experts), suicidal risk (two experts), adolescent SMU (two experts), and EMA methodology (two experts). Experts completed in-person interviews with the first author between September to October 2018. Interviews were semi-structured and followed an interview guide to explore the appropriateness of the drafted measure for the intended target population. Because the target population was adolescents at risk for suicide, experts advised on the potential for burden (instrument length and complexity/simplicity of questions and response options) as suggested by Scott and colleagues (Scott, 1997). Finally, experts offered feedback on elements of the EMA sampling protocol: sampling density (frequency of sampling), timeframe for daily sampling, and potential mechanisms for delivering prompts to complete the EMA measure. The first author created analytic memos, referring to a written transcript of concepts and themes that emerged (Gale, Heath, Cameron, Rashid, & Redwood, 2013), immediately following interviews. Subsequently, the first and second author reviewed themes to harmonize experts’ feedback toward recommended changes to the EMA measure and sampling protocol.

After the measure was refined on the basis of expert interviews, adolescents evaluated the next draft of the EMA measure and sampling protocol through cognitive interviews. Cognitive interviews are a recommended step in the measure development process that involve seeking feedback with the measure’s target audience to understand their thought processes while considering questions and response options (Groves et al., 2009). We recruited adolescents from a research study that enrolled adolescents who had been treated for depression and suicidal thoughts or behaviors. Parents provided consent and adolescents provided assent prior to participation. Adolescents completed in-person interviews with the first author between November 2018 to January 2019, during which they reviewed a web-based version of the measure, developed on Qualtrics. We used a variety of methodology to solicit feedback on the proposed measure: think-alouds (verbalizing thought processes while responding to questions); paraphrasing (restating questions in one’s own words); and definitions (defining key terms within questions) (Groves et al., 2009). Consistent with recommendations for cognitive interviewing with youth (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1989), we explored developmental appropriateness of the measure and sampling protocol for adolescents. Interviews were recorded, transcribed, and coded using thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006). We used a deductive approach to coding to evaluate adolescents’ feedback based on criteria essential for establishing content validity. Content validity refers to the extent with which an instrument appropriately and comprehensively covers all facets of concepts it intends to measure relative to the context of use (Groves et al., 2009). These criteria included: comprehension (i.e., subjective readability), burden, interpretation of question wording and response options, and meaningfulness of included domains. Subsequently, we assessed objective readability using the Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level and Flesch Reading Ease tests, which describe how difficult a passage is to understand (Flesch, 1979; Kincaid, Fishburne, RL, & Chissom, 1975), using an automated scoring program offered through https://readable.com.

1.3. Results

Drafting the EMA Measure

Literature review.

A total of five risk factors and two protective factors were prominent within the systematic reviews and systematized narrative review (see Table 1) (Biernesser et al., 2020; Dyson et al., 2016; Marchant et al., 2017). Risk factors included: heavy use of social media, referring to use in high frequency or volume, problematic SMU, cyberbullying victimization, exposure to self-harm or suicidal content, and thwarted belongingness. Thwarted belongingness refers to a psychologically painful mental state that results from an unmet need to connect to others (Van Orden et al., 2010). Protective factors included the provision of social support from peers and social connectedness.

Table 1.

Social Media-Related Risk and Protective Factors for Adolescent Suicide Identified in Literature Reviews and Focus Groups

| Marchant et al, 2017 Systematic Review | Biernesser et al, 2020 Systematized Review | Nesi et al, 2021 Review & Meta-analysis | Biernesser et al, 2021 Focus group inquiry | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk Factors: | ||||

| Heavy/frequent use | X | X | X | |

| Problematic use | X | X | X* | X |

| Nighttime-specific use | X | |||

| Cyberbullying/ peer victimization | X | X | X* | X |

| Exposure to self-harm/ suicidal content | X | X | X* | X |

| Negative upward social comparison | X | |||

| Thwarted belongingness/ social isolation | X | |||

| Protective Factors: | ||||

| Social connectedness | X | X | X | |

| Peer support | X | X | X | |

| Social engagement | X | |||

in Literature Reviews and Focus Groups

Focus groups.

Adolescent focus group participants (N=15) were ages 13–17 (mean age 15.1 years), seven of whom were female, five of whom were male, and two of whom reported other gender identities. Adolescents universally acknowledged positive aspects of SMU; however, across focus groups all agreed that SMU, at times, contributed to suicidal thoughts:

“I think social media definitely, definitely contributes to having suicidal thoughts, at least for me.” [All participants agree.]

In reflecting on how SMU influenced them, adolescents echoed the risk and protective factors identified from literature reviews (see Table 1); however, they identified two additional negative experiences with SMU and one additional positive experience. Adolescents identified night-time specific SMU and social comparison as negative aspects of SMU. They reported using SMU around sleep times, noting desires to connect with friends or to engage in SMU as a means of distraction from a distressed mood state but found the relief they experienced from use was attenuated by the effects of subsequent sleep loss. Adolescents also reported observing others on social media enjoying or partaking in life in a way their current mental health state prohibited, which they felt exacerbated feelings of anxiety or depressed mood. Adolescents considered opportunities for social engagement, such as engaging in SMU to make plans with friends or maintain relationships, as a positive experience. Participants’ quotes can be found in Table 2.

Table 2.

Adolescents’ Perspectives Toward Positive and Negative Social Media Experiences

| Adolescents’ Positive Experiences with SMU |

|

Receiving support from others through SMU: “Sometimes it’ll be like, ‘I really need to talk to her [referring to friend].’ And I’ll text her and she’ll say something really encouraging that just genuinely makes my day.” |

|

Engaging with others through SMU: “I mostly use it [digital media] just to see if like any of my close friends have anything that they went to share on there that I should know about. Just like stay updated on the world. …I usually only use it to contact my friends to see if we’re going to go hang out or something along those lines.” |

| Adolescents’ Negative Experiences with SMU |

|

SMU that prohibited sleep: “At night I get stuck in the cycle of ‘Well, this is distracting me, and this is working, but I need to stop now to go to bed because that’s what I need to do.’ But then I’m like, ‘Or, you could not. And you could keep using this coping mechanism that’s like healthy and can turn unhealthy if I don’t get the amount of sleep I need too.’” |

|

SMU contributing toward a sense of social comparison: “This probably sounds like super petty or stupid, but I want to have the most followers like I want to be the best. And so, many people are competing.” |

|

Exposure to self-injury content: “They’re like, ‘Oh my gosh, this girl’s cutting herself, I think it’s cool, so I’m going to do it.’ Because social media puts that idea in your head that whatever you see online is cool.” |

|

Cyberbullying experienced through SMU: “Because I think bullying is a big part of social media. I think that’s what drives kids to commit suicide or think about committing suicide, and I think the bullying- they think they’re not good enough. They think they’re not worth it. So, they go into that spiral and start to get upset, and that leads them to post things like that.” |

|

Feeling a lack of belonging from peers: “I see my friends doing these things with each other that I’m not doing with them and it sort of makes me feel excluded from that group of friends. And they care about each other more than they care about me. And it’s sort of being out of that tight-knit group that you thought you were a part of when you see things like that.” |

Based on the literature reviews and focus groups, we developed an initial EMA measure, which was 37 items across eight domains, two of which assessed positive aspects of SMU and six of which assessed negative aspects. We prioritized domains for inclusion based the weight of available evidence linking these factors with suicidal risk among adolescents. Additionally, we added a one-item measure of distress (1 to 10 scale) to assess the degree of impact of positive and negative experiences with SMU.

The initial measure assessed 1) frequency of SMU using an adapted one-item measure from a large-scale health survey of Canadian adolescents (Sampasa-Kanyinga & Lewis, 2015); 2) negative online peer experiences with the 12-item Social Networking-Peer Experiences (SN-PEQ) scale (Landoll, La Greca, & Lai, 2013) (demonstrated excellent internal consistency reliability within a brief longitudinal study, α=.90 - .94) (Frison, Kaveri, & Eggermont, 2016); 3) peer support with the 4-item peer subscale of the Multidimensional Scale for Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) (Zimet, Dahlem, Zimet, & Farley, 1988); 4) social comparison through Buunk’s 2-item scale of Negative Upward Social Comparison Affect (demonstrated adequate internal consistency reliability [α=.77] with a sample of older adolescent social media users) (Wang, Wang, Gaskin, & Hawk, 2017); 5) connectedness using from Grieve and colleagues’ 13-item Facebook Social Connectedness Scale (demonstrated excellent internal consistency reliability, α=.92) (Grieve, Indian, Witteveen, Tolan, & Marrington, 2013); 6) sleep-related impairment through two items drawn from Levenson and colleagues’ study of adolescent social media users (Levenson, Shensa, Sidani, Colditz, & Primack, 2016, 2017); 7) thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness with items drawn from the Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire (demonstrated good internal consistency reliability, α = .84) (Hill et al., 2015; Van Orden, Cukrowicz, Witte, & Joiner, 2012); and 8) exposure to self-harm/suicidal content by a one-item measure of exposure to self-harm or suicidal content, which was developed by the authors.

Refining the EMA measure and determining a sampling protocol

Expert interviews.

Experts (N=5) recommended changes to the measure to reduce participant burden. Overall, experts felt the drafted measure should be shortened, both in terms of the number of domains assessed and the total number of items. Experts suggested three domains, perceived burdensomeness, exposure to self-harm content, and connectedness, may have limited variation over time. Experts recommended sampling for approximately 10 days in duration approximately 2–4 times per day, varying by weekday and weekend and with flexibility around school and sleep schedules. Further, they felt that the best mechanism of delivery was via an online survey deployed to participants with a link provided within a text message.

On the basis of expert interviews, we revised the measure to include skip logic to separately assess positive SMU (i.e., social support and belongingness), negative SMU (i.e., negative peer interactions, negative upward social comparison, and thwarted belongingness), or no SMU with the intention that participants would complete only one of these pathways in each sampling timeframe. Pathways included a maximum of 12 questions. Further, we removed two domains, perceived burdensomeness and exposure to self-harm content, due to concerns over limited variability over time. We replaced a third domain, connectedness with belongingness, which experts expected to be more meaningful to proximal suicidal risk.

Cognitive Interviews.

Adolescent participants in cognitive interviews were predominantly female (60%), White (80%), and had a mean age of 15.2 years (range: 13 to 18 years). Adolescents evaluated the EMA measure’s 18 items across five criteria: comprehension, burden, question interpretation, response interpretation, and meaningfulness of the included domains.

Comprehension.

Participants generally found the measure easy to understand, except for questions that assessed the impact of SMU on distress levels. When given the option of responding to changes in distress using a bipolar response scale (−10 to +10) or a unipolar scale (0 to 10), participants noted a preference toward a unipolar scale with 0 representing no change in distress and 10 representing distress either improved significantly or worsened significantly (depending on the pathway that was chosen).

Burden.

Adolescents found the overall length of the measure acceptable but felt some specific questions that required more cognitive processing to be burdensome, particularly questions pertaining to social comparison and thwarted belongingness. Adolescents offered feedback on wording that would reduce burden and suggested one item (“I felt like an outsider among friends/followers on social media”) be removed due to lack of clarity. Additionally, they recommended adding questions pertaining to social comparison affect with a positive valence, noting that sometimes they compare themselves to others in ways that feel uplifting.

Question Interpretability.

Participants felt most items were easy to understand but had difficulty interpreting the question that was used for screening into the EMA measure, “Think about the most significant time you used social media within the past X hours. How would you describe this social media experience?” They suggested minor wording changes for clarity and thought adolescents may benefit from some orientation to how a significant SMU experience is defined, e.g., an experience that impacted their level of distress either positively or negatively, before the EMA protocol began.

Interpretability of Responses.

Based upon expert feedback indicating that participants may be burdened by too many response options, teens were presented with two options for responses to the items assessing belongingness/thwarted belongingness, a 3-point and 7-point Likert scale. Nearly all participants preferred the 7-point response option, which they felt was useful in effectively communicating ambivalent feelings toward their sense of belonging to others.

Meaningfulness.

Participants consistently found that the questions pertaining to belongingness and negative online peer interactions were most important to include. Reflecting on the importance of addressing questions of belongingness, one participant said:

The other ones are important, but how you felt is significant…If I had to shed every single other question, I would choose that one.

Some participants also pointed to important domains they felt were missing from the measure. Three adolescents noted that being exposed to others’ suicidal or self-harm content had a negative impact on their mental health and in some cases incited self-harm urges. Contrary to perspectives from experts, adolescents felt exposure to self-harm/suicidal content within their peer group occurred frequently (daily or more often).

On the basis of cognitive interviews, we developed a final version of the EMA measure (see Table 3) that includes pathways assessing positive and negative experiences with SMU, as well as positive and negative in-person social experiences. Each pathway has a maximum of 11 questions, in addition to 2 questions pertaining to sleep disturbance that are probed once daily.

Table 3.

Summary of Final EMA Measure

| Measure Domains: | Positive SMU | Negative SMU | Positive In-Person | Negative In-person |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nature of experience | 2 items | 2 items | 2 items | 2 items |

| Frequency of SMU | 1 item | 1 item | ||

| Impact of on distress | 1 item | 1 item | 1 item | 1 item |

| Social support | 1 item | - | 1 item | - |

| Positive social comparison affect | 1 item | - | 1 item | - |

| Belongingness | 4 items | 4 items | - | |

| Negative peer interactions | - | 1 item | - | 1 item |

| Exposure to self-harm/suicidal content | - | 1 item | - | 1 item |

| Negative social comparison affect | - | 1 item | - | 1 item |

| Thwarted belongingness | 4 items | - | 4 items | |

| Total number of items at each assessment timepoint | 10 items | 11 items | 9 items | 10 items |

| Night-time specific SMU (assessed once daily) | 2 items | 2 items | - | - |

Objective Readability Assessment.

We assessed objective readability for the final version of the EMA measure by calculating Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level and Flesch Reading Ease scores. The Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level score was 6.9, suggesting roughly 7 years of formal education are necessary to read and understand the measure. The Flesch Reading Ease score was 60.0, which suggest appropriateness for youth ages 13 and older (Linney, 2017).

Sampling Protocol.

Recommendations for an acceptable sampling density for this measure ranged from 3 days to 1 month with a mean of 10.6 days. Adolescents’ suggestions for how often the measure could be triggered ranged between 2 to 4 times per day (mean of 3 times daily). Adolescents suggested the sampling timeframe should be flexible to their schedules, avoiding times they are in class, having meals with family, attending church or extra-curricular activities, or sleeping. While some adolescents preferred the measure be deployed via an app, they acknowledged that may exclude youth who did not have access to smartphones. All adolescents thought responding via text message would be acceptable.

1.4. Discussion

Through this study, we developed an EMA measure and sampling protocol to assess changes in distress associated with SMU experiences known to influence risk and protective factors for suicide among adolescents. We first drafted the measure based on literature reviews and qualitative data collection and secondly refined the measure and protocol through expert and cognitive interviews with adolescents at high risk for suicide. This research offers initial evidence for the content validity of the EMA measure and acceptability of the associated sampling protocol. Feedback from experts and adolescents led to refinements in item content to address concepts deemed to be most relevant to understanding fluctuations in distress among youth at risk for suicide, anchored with meaningful response options, and delivered in a manner and at times that would be acceptable to adolescents.

This development process yielded a measure that can briefly assess the impact of SMU experiences that are salient to key risk and protective factors for adolescent suicide. First, the measure uses skip logic to improve efficiency in assessing a range of domains: frequency of use, sleep impairment, negative peer interactions, social support, social comparison affect, and belongingness. Of note, two of these domains, social media-related sleep impairment and negative affect associated with online social comparison, were identified only through focus groups and not through the literature reviews. However, these two factors are known to be influential for adolescent social media users with depression and anxiety (Lup, Trub, & Rosenthal, 2015; Woods & Scott, 2016; Yang, 2016), and studies assessing sleep impairment and social comparison within offline environments have found significant associations with suicidal risk (Goldstein, Bridge, & Brent, 2008; Merchant, Kramer, Joe, Venkataraman, & King, 2009; Wetherall, Robb, & O’Connor, 2019). Furthermore, this measure assesses impact on in-person social interactions, which presents the opportunity for fine-grained within-person comparative analyses to understand the unique contribution of SMU to fluctuations in distress.

Strengths and Limitations

The study’s strengths lie in its careful methodological approach to measure development and refinement using an iterative approach that incorporated feedback from both experts and adolescents. The small sample size and use of convenience sampling limits generalizability of the findings. Further, while these methods have established the initial content validity of the measure and acceptability of the sampling protocol, the utility of the measure and sampling protocol remain unknown until psychometric testing is complete and pilot testing reveals adherence with the sampling protocol and some measures of convergent and predictive validity.

Additionally, the estimate of objective readability suggests this measure is adequate for youth in 8th grade or higher. While this is the target age for the measure, Doak and colleagues recommend health literature be written at or below a 5th grade reading level (Doak, Doak, & Root, 1995). Therefore, it is possible that youth of low literacy levels may experience some level of difficulty reading this survey based on these measures. Nonetheless, readability formulas such as this are known to be limited in their ability to diagnose survey question difficulty (Lenzner, 2013). This study’s approach of cognitive interviewing is likely to present a more robust picture of the comprehension for youth within the measures’ intended target population.

Conclusion

This manuscript describes the development of an EMA measure and sampling protocol that aims to assess social media’s impact on the suicidal risk of adolescents. Although future studies are necessary to assess its psychometric properties, this newly developed EMA measure shows promise as an acceptable assessment of social media’s influence on proximal suicidal risk.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Development of an ecological momentary assessment measure and sampling protocol

Exploring brief momentary assessment of social media’s impact on adolescent suicidal risk

Multi-phase approach to establishing content validity and an acceptable sampling protocol

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Isha Yemula for her assistance with transcription. We are also thankful for the adolescents and content and measurement experts who participated in this study.

Funding details: This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health under Grants T32 MH018951 and P50 MH115838.

Disclosure Statement

Drs. Biernesser, Bear, Mair, Zelazny, and Trauth have no disclosures to report. Dr. Brent receives research support from NIMH, AFSP, the Once Upon a Time Foundation, and the Beckwith Foundation, receives royalties from Guilford Press, from the electronic self-rated version of the C-SSRS from eRT, Inc., and from performing duties as an UptoDate Psychiatry Section Editor, receives consulting fees from Healthwise, and receives Honoraria from the Klingenstein Third Generation Foundation for scientific board membership and grant review.

Contributor Information

Candice Biernesser, Departments of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh; Western Psychiatric Hospital, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center..

Todd Bear, Department of Behavioral and Community Health Sciences, Graduate School of Public Health, University of Pittsburgh..

David Brent, Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh; Western Psychiatric Hospital, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center..

Christina Mair, Department of Behavioral and Community Health Sciences, Graduate School of Public Health, University of Pittsburgh..

Jamie Zelazny, School of Nursing, University of Pittsburgh..

Jeanette Trauth, Department of Behavioral and Community Health Sciences, Graduate School of Public Health, University of Pittsburgh..

References

- Anderson M, & Jiang J. (2018). Teens, social media, and technology. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2018/05/31/teens-social-media-technology-2018/.

- Beyens I, Pouwels JL, van D II, Keijsers L, & Valkenburg PM (2020). The effect of social media on well-being differs from adolescent to adolescent. Sci Rep, 10(1), 10763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biernesser C, Sewall CJR, Brent D, Bear T, Mair C, & Trauth J. (2020). Social media use and deliberate self-harm among youth: a systematized narrative review. Child Youth Serv Rev, 116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, & Clarke V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Doak C, Doak L, & Root J. (1995). Teaching patients with low literacy levels. 2nd edition. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Dyson MP, Hartling L, Shulhan J, Chisholm A, Milne A, Sundar P, Scott SD, Newton AS (2016). A systematic review of social media use to discuss and view deliberate self-harm acts. PLoS ONE, 11(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flesch R. (1979). How to write in plain English: A book for lawyers and consumers: Harpercollins. [Google Scholar]

- Frison E, Kaveri S, & Eggermont S. (2016). The short-term longitudinal and reciprocal relations between peer victimization on Facebook and Adolescent’s Well-Being. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45(9), 1755–1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, & Redwood S. (2013). Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol, 13, 117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein TR, Bridge JA, & Brent DA (2008). Sleep disturbance preceding completed suicide in adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol, 76(1), 84–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieve R, Indian M, Witteveen K, Tolan G, & Marrington J. (2013). Face-to-face or Facebook: Can social connectedness be derived online? Comp Hum Behav, 29(3), 604–609. [Google Scholar]

- Groves R, FJ F, Couper M, Lepkowski J, Singer E, & Tourangeau R. (2009). Survey Methodology, 2nd Edition. Hoboken, NJ: A John Wiley and Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Hallensleben N, Glaesmer H, Forkmann T, Rath D, Strauss M, Kersting A, & Spangenberg L. (2018). Predicting suicidal ideation by interpersonal variables, hopelessness and depression in real-time. an ecological momentary assessment study in psychiatric inpatients with depression. Eur Psychiatry, 56, 43–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawton K, & van Heeringen K. (2009). Suicide. Lancet, 373(9672), 1372–1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedegaard H, Curtin SC, & Warner M. (2018). Suicide mortality in the United States, 1999–2018. NCHS Data Brief (330), 1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill RM, Rey Y, Marin CE, Sharp C, Green KL, & Pettit JW (2015). Evaluating the Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire: comparison of the reliability, factor structure, and predictive validity across five versions. Suicide Life Threat Behav, 45(3), 302–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kincaid J, Fishburne R, RL R, & Chissom B. (1975). Derivation of new readability formulas (automated readability index, fog count, and flesch reading ease formula) for Navy enlisted personnel. Memphis, TN: Chief of Naval Technical Training: Naval Air Station. [Google Scholar]

- Kleiman EM, Liu RT, & Riskind JH (2014). Integrating the interpersonal psychological theory of suicide into the depression/suicidal ideation relationship: a short-term prospective study. Behav Ther, 45(2), 212–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landoll RR, La Greca AM, & Lai BS (2013). Aversive peer experiences on social networking sites: development of the Social Networking-Peer Experiences Questionnaire (SN-PEQ). J Res Adolesc, 23(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenzner T. (2013). Are readability formulas valid tools for assessing survey question difficulty? Paper presented at the American Association of Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) Annual Conference, Boston, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Levenson JC, Shensa A, Sidani JE, Colditz JB, & Primack BA (2016). The association between social media use and sleep disturbance among young adults. Prev Med, 85, 36–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levenson JC, Shensa A, Sidani JE, Colditz JB, & Primack BA (2017). Social media use before bed and sleep disturbance among young adults in the United States: a nationally representative study. Sleep, 40(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linney S. (2017). The Flesch Reading Ease and Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level. Retrieved from https://readable.com/blog/the-flesch-reading-ease-and-flesch-kincaid-grade-level/ [Google Scholar]

- Lup K, Trub L, & Rosenthal L. (2015). Instagram #instasad?: exploring associations among Instagram use, depressive symptoms, negative social comparison, and strangers followed. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw, 18(5), 247–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchant A, Hawton K, Stewart A, Montgomery P, Singaravelu V, Lloyd K, Purdy N, Daine K, John A. (2017). A systematic review of the relationship between internet use, self-harm and suicidal behaviour in young people: the good, the bad and the unknown. PLoS ONE, 12(8), e0181722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merchant C, Kramer A, Joe S, Venkataraman S, & King CA (2009). Predictors of multiple suicide attempts among suicidal black adolescents. Suicide Life Threat Behav, 39(2), 115–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Prinstein MJ, & Sterba SK (2009). Revealing the form and function of self-injurious thoughts and behaviors: a real-time ecological assessment study among adolescents and young adults. J Abnorm Psychol, 118(4), 816–827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orben A, & Przybylski AK (2019a). The association between adolescent well-being and digital technology use. Nat Hum Behav, 3(2), 173–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orben A, & Przybylski AK (2019b). Screens, teens, and psychological well-being: evidence from three time-use-diary studies. Psychol Sci, 30(5), 682–696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (1989). Cognitive Testing Interview Guide: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/washington_group/meeting5/wg5_appendix4.pdf

- Radovic A, Gmelin T, Stein BD, & Miller E. (2017). Depressed adolescents’ positive and negative use of social media. J Adolesc, 55, 5–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rideout V, & Michael R. (2019). The Common Sense Census: Media use by tweens and teens. Retrieved from https://www.commonsensemedia.org/sites/default/files/uploads/research/2019-census-8-to-18-full-report-updated.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Sampasa-Kanyinga H, & Lewis RF (2015). Frequent use of social networking sites is associated with poor psychological functioning among children and adolescents. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 18(7), 380–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott J. (1997). Children as Respondents: Methods for Improving Data Quality. New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Seabrook EM, Kern ML, & Rickard NS (2016). Social networking sites, depression, and anxiety: a systematic review. JMIR Ment Health, 3(4), e50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkie EM, Fales JL, & Moreno MA (2016). Cyberbullying prevalence among US middle and high schoole-aged adolescents: a systematic review and quality assessment. Journal of Adolescent Health, 58(2), 125–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Stone AA, & Hufford MR (2008). Ecological momentary assessment. Annu Rev Clin Psychol, 4, 1–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sisask M, Varnik A, Kolves K, Konstabel K, & Wasserman D. (2008). Subjective psychological well-being (WHO-5) in assessment of the severity of suicide attempt. Nord J Psychiatry, 62(6), 431–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spada MM (2014). An overview of problematic internet use. Addict Behav, 39(1), 3–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turecki G, & Brent DA (2016). Suicide and suicidal behaviour. Lancet, 387(10024), 1227–1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Cukrowicz KC, Witte TK, & Joiner TE (2012). Thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness: construct validity and psychometric properties of the Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire. Psychol Assess, 24(1), 197–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC, Braithwaite SR, Selby EA, & Joiner TE Jr. (2010). The Interpersonal Theory of Suicide. Psychol Rev, 117(2), 575–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandewater EA, & Lee SJ (2009). Measuring children’s media use in the digital age: issues and challenges. Am Behav Sci, 52(8), 1152–1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viner RM, Aswathikutty-Gireesh A, Stiglic N, Hudson LD, Goddings AL, Ward JL, & Nicholls DE (2019). Roles of cyberbullying, sleep, and physical activity in mediating the effects of social media use on mental health and wellbeing among young people in England: a secondary analysis of longitudinal data. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JL, Wang HZ, Gaskin J, & Hawk S. (2017). The mediating roles of upward social comparison and self-esteem and the moderating role of social comparison orientation in the association between social networking site usage and subjective well-being. Front Psychol, 8, 771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetherall K, Robb KA, & O’Connor RC (2019). An examination of social comparison and suicide ideation through the lens of the Integrated Motivational-Volitional Model of Suicidal Behavior. Suicide Life Threat Behav, 49(1), 167–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods HC, & Scott H. (2016). #Sleepyteens: social media use in adolescence is associated with poor sleep quality, anxiety, depression and low self-esteem. J Adolesc, 51, 41–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang CC (2016). Instagram use, loneliness, and social comparison orientation: interact and browse on social media, but don’t compare. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw, 19(12), 703–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimet G, Dahlem N, Zimet S, & Farley G. (1988). The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 1988(52), 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.