Abstract

Background

In March 2020, the Ontario government declared a state of emergency due to the growing risk of COVID-19. In response, new guidance for the management of opioid agonist therapy (OAT) was released, which included the expansion of eligibility for take-home doses. We investigated the impact of these changes on trends in the distribution of take-home doses of OAT.

Methods

We conducted a population-based time series analysis among residents of Ontario, Canada who were dispensed OAT between June 25, 2019 and November 30, 2020. For each week of the study period, we calculated the percentage of people dispensed (a) methadone and (b) buprenorphine/naloxone by the number of take-home doses received. We used interventional autoregressive integrated moving average models to estimate changes in the percentage of people dispensed each category of take-home doses in the weeks following the declaration of the state of emergency and release of the OAT dispensing guidance.

Results

Following the state of emergency and release of the OAT dispensing guidance, there was a significant increase in the percentage of Ontarians dispensed 7 to 13 (3.6% increase; p = 0.033) and 14 or more (0.8% increase; p<0.001) take-home doses of methadone, and in the percentage of people dispensed 7 to 13 (4.3% increase; p = 0.001), 14 to 27 (2.8% increase; p<0.001), and 28 or more (0.3% increase; p = 0.008) take-home doses of buprenorphine/naloxone. There were significant decreases in the percentage of Ontarians receiving daily dispensed buprenorphine/naloxone (-3.1%; p = 0.001), as well as the percentage dispensed 1 to 6 take-home doses of methadone (-4.5%; p = 0.001) and buprenorphine/naloxone (-4.9%; p = 0.001).

Conclusion

The new guidance for dispensing OAT in Ontario resulted in increases in the duration of take-home doses of methadone and buprenorphine/naloxone supplied. However, given that changes were small, strategies to improve retention in OAT and ensure equitable access to take-home dosing should continue.

Keywords: Opioid agonist therapy, Take-home doses, Opioid use disorder, COVID-19

Introduction

Opioid agonist therapy (OAT) with methadone or buprenorphine/naloxone is a safe and effective treatment that has been shown to reduce the risk of death among people with opioid use disorder (Bruneau et al., 2018; Karki, Shrestha, Huedo-Medina, & Copenhaver, 2016; Larochelle et al., 2018; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Association (SAMSHA), 2020). Treatment with OAT typically requires regular interaction with the prescribing clinician and daily supervised dosing in community pharmacies until people are deemed eligible for take-home doses based on a clinical assessment of risks and benefits, which generally includes reliance on urine drug screens to confirm abstinence from illicit substances (CRISM National Guideline Review Committee, 2017). A take-home dose, sometimes referred to as a carry, is a dose of OAT that can be taken at home, and can therefore lessen the need for frequent face-to-face contact between people receiving OAT and providers, a known barrier to continued engagement in OAT (Kourounis et al., 2016). Across several treatment settings, it was estimated that only one-third of people with opioid use disorder ever start OAT (Blanco et al., 2013; Socías, Volkow, & Wood, 2016), and among those who did start OAT, less than half remained in treatment for 6 months (Blanco & Volkow, 2019; Timko, Schultz, Cucciare, Vittorio, & Garrison-Diehn, 2016). In this context, concern has been raised that COVID-19-associated changes to healthcare delivery intended to accommodate physical distancing, such as reduced hours of pharmacy operation and shifts to virtual primary care, along with public health requirements to self-isolate or quarantine, could further disrupt regular access to OAT and retention in care (Ahamad et al., 2020). These concerns are driven by evidence demonstrating that individuals who discontinue OAT are at an increased risk of overdose and death (Sordo et al., 2017). In light of this, policies and procedures aimed at ensuring uninterrupted access to OAT during the COVID-19 pandemic are needed.

Canadian guidelines for the management of opioid use disorder recommend two to three months of daily supervised dosing at pharmacies or Opioid Treatment Programs for people receiving methadone, and at least 7 to 10 days for people receiving buprenorphine/naloxone (Bruneau et al., 2018). Further, patients must be deemed clinically and socially stable before take-home doses are prescribed. In Ontario, Canada's most populous province (population of 14.7 million in 2020 (Statistics Canada, 2021)) and home to nearly 40% of the national population, a state of emergency for COVID-19 was declared on March 17, 2020 (Government of Ontario, 2020). Less than a week later, on March 22, 2020, new guidance for the management of OAT during the pandemic was released by a working group of Ontario clinicians with expertise in addiction medicine (Centre for Addiction & Mental Health, 2020). A key recommendation of this guidance was for prescribers to use their clinical judgement to increase the number of take-home doses for those already receiving them, and to provide limited numbers of take-home doses for individuals who may not have been eligible under the existing treatment guidelines (Bruneau et al., 2018; Smith, Brands, Novonta, & Kushnir, 2011). Given this rapid transformation of treatment delivery, as well as the acceleration of an ongoing overdose mortality epidemic, there is an urgent need to evaluate the uptake of this new COVID-19 OAT guidance in Ontario.

Our objective was to investigate the impact of COVID-19 associated public health restrictions and changes in guidance for the provision of OAT on patterns of take-home doses of methadone and buprenorphine/naloxone. We hypothesized that the declaration of the state of emergency in Ontario due to COVID-19 (March 17, 2020) and the subsequent release of the COVID-19 OAT guidance (March 22, 2020) would lead to an immediate increase in the provision of take-home doses of OAT.

Methods

Study design and setting

We conducted a retrospective, population-based interrupted time-series analysis of Ontario residents receiving methadone or the combination product buprenorphine/naloxone for OAT between June 25, 2019 and November 30, 2020.

Data sources

We obtained data from ICES (formerly the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences), an independent, non-profit research institute in Ontario whose legal status allows for the collection and analysis of administrative healthcare and demographic data, without consent, for health system evaluation and improvement. To identify claims for methadone and buprenorphine/naloxone, we used the Narcotics Monitoring System database, which captures all prescriptions for controlled substances dispensed from community pharmacies in Ontario, regardless of payer. We used the Registered Persons Database, a registry of all Ontario residents eligible for health insurance, to ascertain demographic characteristics. These datasets were linked using unique encoded identifiers and analyzed at ICES. The use of data in this project was authorized under Section 45 of Ontario's Personal Health Information Protection Act, which does not require review by a Research Ethics Board.

Study population and measures

We identified all prescriptions for methadone and buprenorphine/naloxone dispensed between June 25, 2019 and November 30, 2020. To allow for linkage to the ICES data repository, we restricted our analysis to prescriptions dispensed to people with a valid OHIP number. In Ontario, each dose of methadone and different strengths of buprenorphine/naloxone dispensed to an individual on a given date are entered separately into the pharmacy claims system. Therefore, we used claims aggregated by dispense date to determine the total days’ supply dispensed to each person on each day. For each of those records, we then calculated the number of take-home doses dispensed as one less than the total days’ supply on the record to reflect the consumption of the observed dose on the day that the drug was dispensed. Based on this, we reported the total number of aggregated methadone and buprenorphine/naloxone records over the study period, as well as the total number of people dispensed methadone or buprenorphine/naloxone.

Our main outcome was the percentage of individuals dispensed methadone or buprenorphine/naloxone who received take-home doses of OAT in each week of the study period. For each week of the pre-COVID-19 period (June 25, 2019 to March 16, 2020) and the COVID-19 period (March 17, 2020 to November 30, 2020), we categorized the number of people dispensed (a) methadone and (b) buprenorphine/naloxone by the maximum number of take-home doses each person received in that week (categorized as 0, 1 to 6, 7 to 13, 14 to 27, and 28 or more for buprenorphine/naloxone, and as 0, 1 to 6, 7 to 13, and 14 or more for methadone due to rare occurrences of 28 or more methadone take-home doses). We then calculated the percentage of people dispensed each take-home dose category by the corresponding type of OAT. The numerator was the weekly count of people dispensed each category of take-home doses for the medication of interest, and the denominator was the total number of people dispensed the medication during the week of interest. To examine trends in different sub-populations and areas of the province with varying access to pharmacies and outpatient care, we stratified the measures by sex and urban versus rural region of residence. Because methadone is associated with a higher risk of opioid-related overdose than buprenorphine/naloxone (Centre for Addiction & Mental Health, 2020), we reasoned that clinicians may have been more apprehensive about prescribing take-home doses of methadone, particularly to people receiving high doses of the drug. We therefore also stratified our measures by maximum daily methadone dose received during the week of interest (<100 mg/ml vs. ≥100 mg/ml) to explore heterogeneity in take-home methadone dispensing by dose. Finally, to identify interruptions in access to treatment, we also calculated the weekly number of Ontario residents actively being treated with each type of OAT, defined as individuals who were either dispensed the medication during the week of interest, or had a claim for the medication with a days’ supply overlapping that week.

Analysis

We used interventional autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) models (Schaffer, Dobbins, & Pearson, 2021) to examine the impact of the COVID-19-related state of emergency and OAT guidance on the weekly percentage of people dispensed each category of take-home doses, by type of treatment, with a step transfer function representing both the declaration of the state of emergency and the release of the guidance fit to the week starting March 17, 2020 (Tuesday, March 17, 2020 to Monday, March 23, 2020). We differenced each time series to achieve stationarity, which was confirmed using the augmented Dickey-Fuller test. We selected model parameters using the residual autocorrelation function (ACF), partial autocorrelation function (PACF), and inverse autocorrelation function (IACF) correlograms. Lastly, we identified the final models using the autocorrelation plots and the Ljung-Box chi-square test for white noise. All analyses were conducted using SAS (Enterprise Guide v 7.1, Base v 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and used a type 1 error rate of 0.05.

Involvement of people with lived experience

The Ontario Drug Policy Research Network hosts a Lived Experience Advisory Group (LEAG) that is comprised of people with living and lived experience with opioid use. The LEAG provided feedback on the study approach and the measures included. In addition, we engaged one of the LEAG members, a co-author on this manuscript, throughout the conduct of the study, in order to gain further insight into the methods and the contextualization of the results.

Results

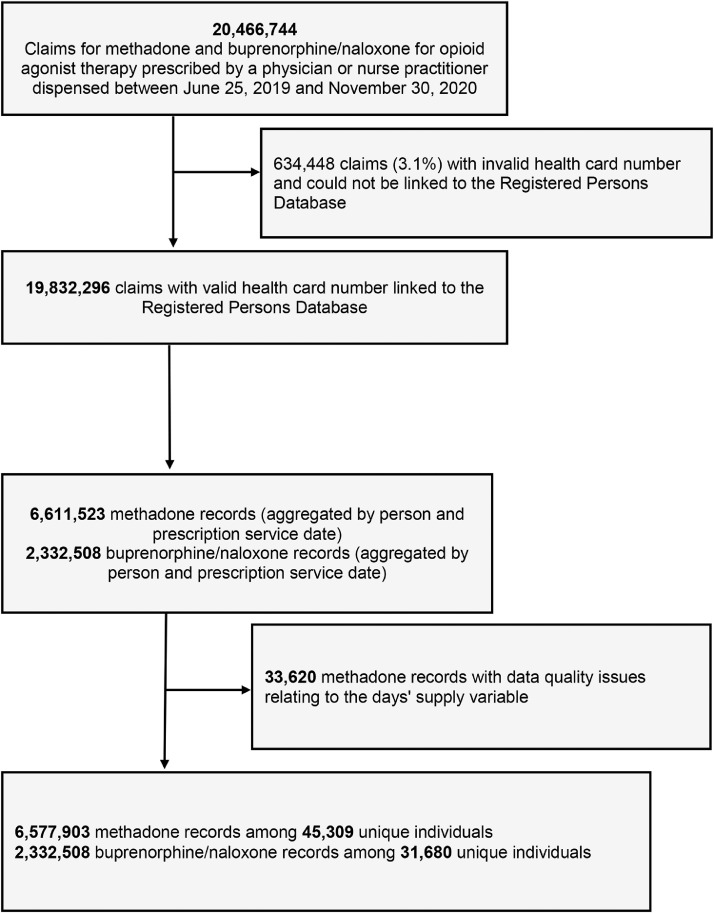

We identified 20,466,744 claims for methadone and buprenorphine/naloxone between June 25, 2019 and November 30, 2020. After aggregating prescriptions dispensed on the same day and applying exclusions, the final dataset contained 6,577,903 methadone records among 45,309 unique people and 2,332,508 buprenorphine/naloxone records among 31,680 unique people (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Record identification process.

Methadone

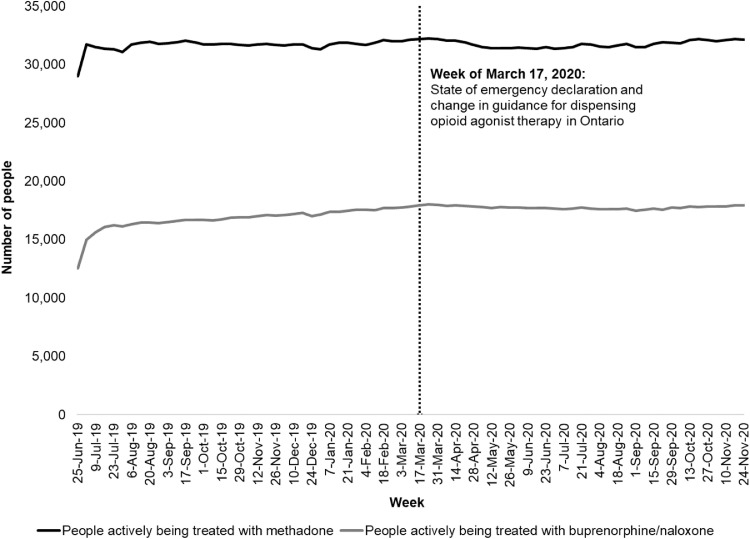

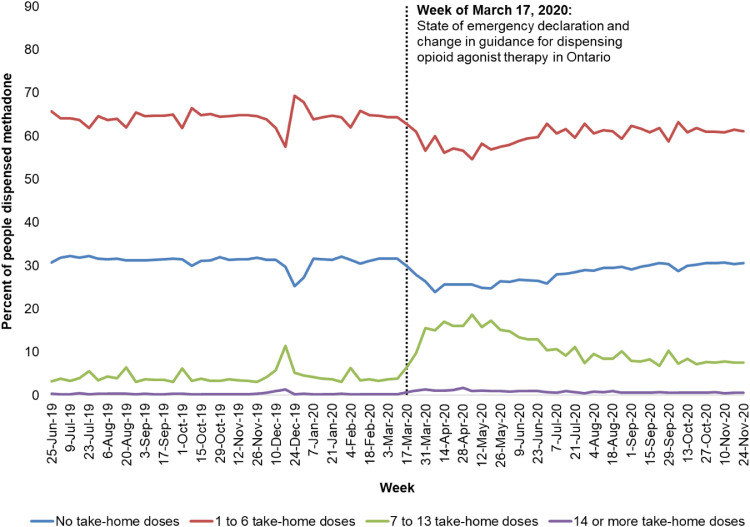

Over the study period, methadone use was more common (range 25,263 to 30,907 individuals per week) compared to buprenorphine/naloxone (range 11,352 to 14,190 individuals per week). The most common dispensing regimen among people receiving methadone was 1 to 6 take-home doses (range 54.7% to 69.3% of people receiving methadone each week), and the second most common regimen was daily dispensed dosing (range 23.8% to 32.3% of people receiving methadone each week). The least common regimen was 14 or more take-home doses (range 0.2% to 1.8% of people receiving methadone each week).

In our main analysis, we observed a significant immediate increase in the percentage of Ontarians dispensed both 7 to 13 take-home doses (estimated step change of 3.6%; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.3% to 7.0%; p = 0.033) and 14 or more take-home doses of methadone (estimated step change of 0.8%; 95% CI 0.4% to 1.1%; p<0.001) following the state of emergency and release of updated OAT guidance, representing 1071 and 229 additional people receiving each respective category of take-home doses in the week following the intervention (Table 1 ). There was a corresponding significant decrease in the prevalence of people receiving 1 to 6 take-home doses (estimated step change of −4.5%; 95% CI −7.3% to −1.7%; p = 0.001), and a non-significant decrease in the percentage of people receiving daily dispensed methadone (estimated step change of −1.9%; 95% CI −4.0% to 0.1%; p = 0.062), representing 1328 and 570 fewer individuals receiving each respective treatment regimen in the week following the state of emergency and release of the COVID-19 OAT guidance. An average of 30% of all methadone recipients continued to receive daily dispensed treatment during the COVID-19 period. Importantly, the total number of people actively being treated with methadone remained consistent over the study period (Fig. 2 ). Among methadone recipients, the observed increases in take-home doses began to trend towards pre-pandemic levels by the end of November 2020, although there remained a slightly higher prevalence of people dispensed 7 or more take-home doses (8.2% during the week of November 24th, 2020 vs. 4.1% during the week of March 10th, 2020) (Fig. 3 ). Trends were similar by sex (Fig. S1), urban versus. rural region of residence (Fig. S2), and by dose dispensed (Fig. S3).

Table 1.

Results of the interventional ARIMA analysis.

| Outcome | ARIMA Model | March 17, 2020 Step Intervention Estimate |

95% Confidence Interval | March 17, 2020 Step Intervention p-value |

Estimated Change in Number of People |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Methadone | |||||

| No take-home doses (daily dispensed) | (2,1,0) no intercept | −1.9% | −4.0% to 0.1% | 0.062 | −570 people |

| 1 to 6 take-home doses | (4,1,0) no intercept | −4.5% | −7.3% to −1.7% | 0.001 | −1328 people |

| 7 to 13 take-home doses | (2,1,0) no intercept | 3.6% | 0.3% to 7.0% | 0.033 | 1071 people |

| 14+ take-home doses | (9,1,0) no intercept | 0.8% | 0.4% to 1.1% | <0.001 | 229 people |

|

Buprenorphine/naloxone | |||||

| No take-home doses (daily dispensed) | (3,1,0) no intercept | −3.1% | −4.8% to −1.3% | 0.001 | −409 people |

| 1 to 6 take-home doses | (3,1,0) no intercept | −4.9% | −7.8% to −1.9% | 0.001 | −646 people |

| 7 to 13 take-home doses | (3,1,0) no intercept | 4.3% | 1.7% to 6.9% | 0.001 | 574 people |

| 14 to 27 take-home doses | (4,1,0) no intercept | 2.8% | 1.8% to 3.8% | <0.001 | 378 people |

| 28+ take-home doses | (10,1,0) no intercept | 0.3% | 0.1% to 0.5% | 0.008 | 40 people |

Note: Boldface indicates statistical significance (p<0.05).

Fig. 2.

Weekly number of people actively being treated with methadone and buprenorphine/naloxone, June 25, 2019 to November 30, 2020. Note: Counts for the week of June 25th and July 2nd, 2019 appear lower because our study period began on June 25, 2019, and therefore data for people who were actively being treated during the first couple weeks of the study period do not capture individuals who were dispensed OAT prior to the beginning of the study period and had take-home doses that overlapped the beginning of study period.

Fig. 3.

Weekly percentage of people dispensed methadone by number of take-home doses,

June 25, 2019 to November 30, 2020, Ontario.

Buprenorphine/naloxone

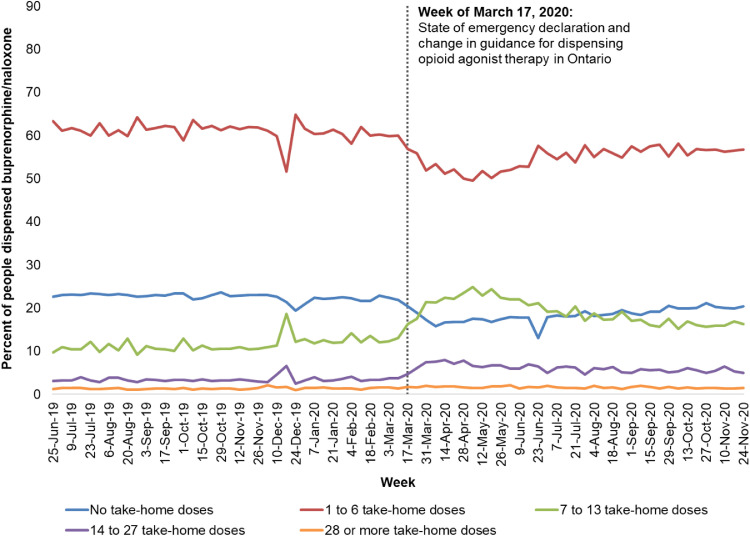

Among people receiving buprenorphine/naloxone, the most common dispensing pattern across the entire study period was 1 to 6 take-home doses (range 49.5% to 64.9% of people receiving buprenorphine/naloxone each week), and the least common was 28 or more take-home doses (range 1.0% to 2.1% of people receiving buprenorphine/naloxone each week). Daily dosing was the second most commonly dispensed regimen across the study period, ranging from 13.1% to 23.6% of people receiving buprenorphine/naloxone in each week. Similar to methadone, there was a significant immediate increase in the weekly percentage of people dispensed 7 to 13 (estimated step change of 4.3%; 95% CI 1.7% to 6.9%; p = 0.001), 14 to 27 (estimated step change of 2.8%; 95% CI 1.8% to 3.8%; p<0.001), and 28 or more take-home doses of buprenorphine/naloxone (estimated step change of 0.3%; 95% CI 0.1% to 0.5%; p = 0.008) following the state of emergency and release of updated OAT guidance, representing 574, 378, and 40 additional people receiving each respective category of take-home doses in the week following the intervention (Table 1). There was a corresponding significant decrease in the prevalence of people receiving daily dispensed buprenorphine/naloxone (estimated step change of −3.1%; 95% CI −4.8% to −1.3%; p = 0.001) and 1 to 6 take-home doses of buprenorphine/naloxone (estimated step change of −4.9%; 95% CI −7.8% to −1.9%; p = 0.001), representing 409 and 646 fewer people receiving each respective treatment regimen in the week following the intervention. Overall, an average of 18% of people continued to receive daily dispensed buprenorphine/naloxone following the intervention. Consistent with patterns observed among methadone recipients, the number of people actively being treated with buprenorphine/naloxone was relatively stable during the study period (Fig. 2). As with methadone, the distribution of take-home doses among buprenorphine/naloxone recipients started to return to levels observed prior to the pandemic towards the end of the study period, although there continued to be a slightly higher prevalence of people receiving 7 or more take-home doses at the end of November 2020 relative to March 2020 (22.9% during the week of November 24th, 2020 vs. 18.0% during the week of March 10th, 2020) (Fig. 4 ). Similar trends were observed by sex (Fig. S4) and by urban vs. rural location in the province (Fig. S5).

Fig. 4.

Weekly percentage of people dispensed buprenorphine/naloxone by number of take-home doses, June 25, 2019 to November 30, 2020, Ontario.

Discussion

In this population-based study, we observed increases in the duration of take-home doses supplied following the implementation of COVID-related public health restrictions and updated OAT guidance, with immediate increases in the percentage of people receiving one week or more of medication. The greater flexibility in take-home provision of OAT was more concentrated among individuals already receiving take-home doses of methadone or buprenorphine/naloxone, with slightly less impact observed among individuals being dispensed OAT daily. In addition, take-home prescribing trends began to revert to pre-pandemic patterns towards the end of the study period, suggesting that shifts in use may not have been sustained over time. Overall, we found that updated OAT guidance and public health restrictions liberalized the duration of take-home doses permitted for people receiving OAT, however, approximately one-third of methadone recipients and one-fifth of buprenorphine/naloxone recipients continued to receive daily dispensed treatment during the pandemic.

Our study has important implications for public health. Specifically, a central tenet of the updated COVID-19 OAT guidance recommended increased access to take-home dosing when clinically appropriate; however, our findings suggest that the guidance may not have been equitably applied to all OAT recipients in Ontario, with a considerable proportion of people remaining on daily dispensed OAT. There are several possible reasons why some individuals may not have shifted to longer take-home doses of OAT. First, clinical judgment is required when deciding whether people are sufficiently clinically stable to be suitable for take-home doses. It is anticipated that some people would not meet these criteria, and would therefore not have their take-home doses altered (Centre for Addiction & Mental Health, 2020, 2021). Second, although many people receiving OAT have stated that take-home programs offer more flexibility and autonomy, some may prefer the structure of daily dispensing, and therefore individual preferences and circumstances should be considered when determining the frequency of take-home doses (Majid & Loshak, 2019). Third, people newly initiating treatment would generally start with daily dispensed treatment (Smith et al., 2011). However, this is unlikely to fully explain our findings, as data from Ontario estimates that 17.7% of monthly OAT recipients in 2020 were newly starting treatment (Ontario Drug Policy Research Network, 2018), whereas 30% of methadone recipients in our study continued to receive daily dispensed therapy. Finally, the trends observed could be reflective of variability in how prescribers determined eligibility for take-home doses (Centre for Addiction & Mental Health, 2020, 2021; Smith, Brands, Novonta, & Kushnir, 2011). One qualitative study of participants from across Canada found that despite increased access to take-home doses of OAT among some people during the pandemic, there was a lack of standardization across clinics, and many had not adapted their services to allow for ease of accessibility (Russell et al., 2021). Introducing standardized criteria for take-home doses could facilitate equitable access to this treatment.

The reversal in trend towards pre-pandemic OAT prescribing practices observed towards the end of our study period is important and suggests that efforts to increase accessibility of OAT take-home doses could be short-lived. This could reflect concerns about patient safety following prolonged liberalization of OAT prescribing or a return to the ‘status quo’ of more restrictive pre-pandemic criteria for take-home dosing (Smith et al., 2011). More research is therefore needed to understand the extent to which the reversion back to pre-pandemic trends of take-home dose dispensing was driven by patient-centered decision making, particularly given the documented preferences of some people who use drugs towards extended take-home doses (Frank et al., 2021). Ensuring equitable access to OAT is particularly important in the context of the recent surge in opioid-related overdose deaths occurring during the pandemic across North America. In Ontario specifically, an estimated 17,843 additional years of life were lost due to opioid overdose during the first six months of the pandemic compared with the six months prior (Gomes, Kitchen, & Murray, 2021). Consequently, measures are needed to further improve retention in OAT treatment and equitable access to take-home doses, including introducing standardized criteria for assessing patient stability and making OAT treatment options more patient-centered.

Our findings are consistent with those of other jurisdictions. Specifically, studies conducted in the United States found increases in the number of methadone take-home doses (Amram, Amiri, Thorn, Lutz, & Joudrey, 2021; Figgatt, Salazar, Day, Vincent, & Dasgupta, 2021), the average days’ supply of dispensed buprenorphine (Cance & Doyle, 2020) and the mean number of dispensed units of buprenorphine per prescription following the onset of COVID-19 (Currie, Schnell, Schwandt, & Zhang, 2021). A recent survey-based study conducted in Connecticut found a large reduction in the percentage of patients receiving one or no take-home doses of methadone (37.5% before the pandemic to 9.6% during the pandemic), and a large increase in the percentage receiving 14 take-home doses (14.2% before the pandemic to 26.8% during the pandemic) (Brothers, Viera, & Heimer, 2021). The smaller magnitude of changes in our study may reflect regional variation in the response to the COVID-19 pandemic on methadone prescribing, differences between patient populations in risk factors for adverse outcomes, and/or the use of population-based databases in our study compared to the survey approach used by Brothers et al. On a global scale, 47 countries expanded take-home dose capacities for OAT during the COVID-19 pandemic (Harm Reduction International). Unpublished research from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime and the Medecins du Monde has reported that expanded access to OAT during COVID-19 resulted in high adherence to treatment, high continuation of treatment for people in isolation, limited adverse events, and high satisfaction among people receiving OAT and prescribers in several countries, including Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Indonesia, Moldova, Morocco, Myanmar, and Nepal (United Nations Office on Drugs & Crime & Medecins du Monde, 2021). Our study advances the literature by conducting a large population-based analysis of the impact of COVID-19 on take-home doses of methadone and buprenorphine/naloxone by duration dispensed, which provides specific targets to inform future clinical practice.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of our study include the use of a large and comprehensive database capturing all individuals dispensed methadone and buprenorphine/naloxone during the study period. However, our study has some limitations. First, our data source does not capture OAT dispensed to people in correctional institutions or OAT administered as part of treatment in a public hospital, although this would represent a small fraction of all OAT dispensed in Ontario. Furthermore, our study period precluded our ability to examine the longer-term impacts of the COVID-19 OAT guidance, including whether subsequent waves of COVID-19 resulted in a resurgence of longer take-home doses. We were also unable to assess how trends in urine drug screens changed during the COVID-19 pandemic and what impact this may have had on clinicians’ decision to prescribe take-home doses. Further, our databases do not contain information on other factors known to influence OAT access and retention, including opioid use disorder severity, race or ethnicity, housing status and history of incarceration. Finally, due to the nature of our study design, we were not able to assess rates of people exiting treatment over the study period and how they may have differed between dosing regimens. However, the number of people actively being treated with methadone and buprenorphine/naloxone was relatively stable across the study period, which indicates that patterns of people initiating and discontinuing treatment likely did not change substantially over the study period. Nevertheless, future work is needed to understand how the pandemic-related guidance for the management of opioid agonist therapy impacted patterns of treatment discontinuation.

Conclusion

We observed a small, but statistically significant increase in the dispensing of longer take-home doses of OAT immediately following the declaration of a COVID-19 state of emergency and updated OAT guidance. However, approximately one-third of methadone recipients and one-fifth of buprenorphine/naloxone recipients continued to receive daily dispensed treatment during the pandemic. Given the worsening of the opioid crisis during the COVID-19 pandemic in Ontario, these findings suggest that more comprehensive strategies to improve retention in OAT and ensure equitable access to take-home dosing are required.

Ethics approval

The authors declare that they have obtained ethics approval from an appropriately constituted ethics committee/institutional review board where the research entailed animal or human participation.

Declarations of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Jennifer Wyman participated as an author in the opioid agonist therapy guidance document that was released in Ontario in March 2020 and is referred to in this manuscript. No other authors have any competing interests to declare.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by grants from the Ontario Ministry of Health (grant #0691) and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (grant #153070). This study was supported by ICES, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health (MOH) and the Ministry of Long-Term Care (MLTC). Parts of this material are based on data and information compiled and provided by the MOH and Canadian Institute for Health Information. The analyses, conclusions, opinions and statements expressed herein are solely those of the authors and do not reflect those of the funding or data sources; no endorsement is intended or should be inferred. We thank IQVIA Solutions Canada Inc. for use of their Drug Information File.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2022.103644.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- Ahamad, K., Bach, P., Brar, R., Chow, N., Coll, N., Compton, M. et al. (2020). Risk mitigation in the context of dual public health emergencies. Retrieved from https://www.bccsu.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Risk-Mitigation-in-the-Context-of-Dual-Public-Health-Emergencies-v1.6.pdf.

- Amram O., Amiri S., Thorn E.L., Lutz R., Joudrey P.J. Changes in methadone take-home dosing before and after COVID-19. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2021;133 doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco C., Iza M., Schwartz R.P., Rafful C., Wang S., Olfson M. Probability and predictors of treatment-seeking for prescription opioid use disorders: A national study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2013;131(1–2):143–148. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco C., Volkow N.D. Management of opioid use disorder in the USA: Present status and future directions. Lancet (London, England) 2019;393(10182):1760–1772. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(18)33078-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brothers S., Viera A., Heimer R. Changes in methadone program practices and fatal methadone overdose rates in Connecticut during COVID-19. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2021;131 doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruneau J., Ahamad K., Goyer M.-.È., Poulin G., Selby P., Fischer B., et al. Management of opioid use disorders: A national clinical practice guideline. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2018;190(9):E247. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.170958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cance J.D., Doyle E. Changes in outpatient buprenorphine dispensing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2020;324(23):2442–2444. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.22154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. (2020). Early guidance for pharmacists in managing opioid agonist treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic. Retrieved from https://camh.ca/-/media/files/camh-covid-19-oat-guidance-for-pharmacists-pdf.pdf.

- Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. (2021). Opioid agonist therapy: A synthesis of Canadian guidelines for treating opioid use disorder. Retrieved from https://www.camh.ca/-/media/files/professionals/canadian-opioid-use-disorder-guideline2021-pdf.pdf.

- CRISM National Guideline Review Committee. (2017). CRISM national guideline for the clinical management of opioid use disorder. Retrieved from https://crism.ca/projects/opioid-guideline/.

- Currie J.M., Schnell M.K., Schwandt H., Zhang J. Prescribing of opioid analgesics and buprenorphine for opioid use disorder during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. A. M. A. Network Open. 2021;4(4) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.6147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figgatt M.C., Salazar Z., Day E., Vincent L., Dasgupta N. Take-home dosing experiences among persons receiving methadone maintenance treatment during COVID-19. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2021;123 doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank D., Mateu-Gelabert P., Perlman D.C., Walters S.M., Curran L., Guarino H. It's like ‘liquid handcuffs”: The effects of take-home dosing policies on Methadone Maintenance Treatment (MMT) patients’ lives. Harm Reduction Journal. 2021;18(1):88. doi: 10.1186/s12954-021-00535-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes T., Kitchen S.A., Murray R. Measuring the burden of opioid-related mortality in Ontario, Canada, during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. A. M. A. Network Open. 2021;4(5) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.12865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Government of Ontario (2020). Ontario enacts declaration of emergency to protect the public. Retrieved from https://news.ontario.ca/en/release/56356/ontario-enacts-declaration-of-emergency-to-protect-the-public.

- Harm Reduction International. The global state of harm reduction (2020). Retrieved from https://www.hri.global/global-state-of-harm-reduction-2020.

- Karki P., Shrestha R., Huedo-Medina T.B., Copenhaver M. The impact of methadone maintenance treatment on HIV risk behaviors among high-risk injection drug users: A systematic review. Evidence-based Medicine & Public Health. 2016;2:e1229. doi: 10.14800/emph.1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kourounis G., Richards B.D., Kyprianou E., Symeonidou E., Malliori M.M., Samartzis L. Opioid substitution therapy: Lowering the treatment thresholds. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2016;161:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larochelle M.R., Bernson D., Land T., Stopka T.J., Wang N., Xuan Z., et al. Medication for opioid use disorder after nonfatal opioid overdose and association with mortality: A cohort study. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2018;169(3):137–145. doi: 10.7326/m17-3107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majid, U., & Loshak, H. (2019). Opioid agonist treatments for opioid use disorder: A rapid qualitative review. Retrieved from https://cadth.ca/buprenorphine-opioid-use-disorders-rapid-qualitative-review-0.

- Ontario Drug Policy Research Network. (2018). Ontario prescription opioid tool. Retrieved from https://odprn.ca/ontario-opioid-drug-observatory/ontario-prescription-opioid-tool/.

- Russell C., Ali F., Nafeh F., Rehm J., LeBlanc S., Elton-Marshall T. Identifying the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on service access for people who use drugs (PWUD): A national qualitative study. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2021;129 doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffer A.L., Dobbins T.A., Pearson S.-.A. Interrupted time series analysis using autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) models: A guide for evaluating large-scale health interventions. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2021;21(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12874-021-01235-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C.B.R., Brands B., Novonta G., Kushnir V. 2011. Methadone Maintenance Treatment Program Standards and Clinical Guidelines. Retrieved from Ontario, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Smith C., Brands B., Lacroix M., Weisdorf D., Novotná G., Kushnir V. College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario; 2011. Methadone Maintenance Treatment Program Standards and Clinical Guidelines. [Google Scholar]

- Socías M.E., Volkow N., Wood E. Adopting the 'cascade of care' framework: An opportunity to close the implementation gap in addiction care? Addiction. 2016;111(12):2079–2081. doi: 10.1111/add.13479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sordo L., Barrio G., Bravo M.J., Indave B.I., Degenhardt L., Wiessing L., et al. Mortality risk during and after opioid substitution treatment: Systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. British Medical Journal. 2017;357:j1550. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. (2021). Population estimates, quarterly. Retrieved from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1710000901.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Association (SAMSHA). (2020). Medications for opioid use disorder- for healthcare and addiction professionals, policymakers, patients, and families. Retrieved from https://store.samhsa.gov/product/TIP-63-Medications-for-Opioid-Use-Disorder-Full-Document/PEP20-02-01-006. [PubMed]

- Timko C., Schultz N.R., Cucciare M.A., Vittorio L., Garrison-Diehn C. Retention in medication-assisted treatment for opiate dependence: A systematic review. Journal of Addictive Diseases. 2016;35(1):22–35. doi: 10.1080/10550887.2016.1100960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, & Medecins du Monde. (2021). Take-home OST in the context of COVID-19: Successes and opportunities. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zmeKjiaxCmw.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.