Abstract

Isoprene is synthesized and emitted in large amounts by a number of plant species, especially oak (Quercus sp.) and aspen (Populus sp.) trees. It has been suggested that isoprene improves thermotolerance by helping photosynthesis cope with high temperature. However, the evidence for the thermotolerance hypothesis is indirect and one of three methods used to support this hypothesis has recently been called into question. More direct evidence required new methods of controlling endogenous isoprene. An inhibitor of the deoxyxylulose 5-phosphate pathway, the alternative pathway to the mevalonic acid pathway and the pathway by which isoprene is made, is now available. Fosmidomycin eliminates isoprene emission without affecting photosynthesis for several hours after feeding to detached leaves. Photosynthesis of fosmidomycin-fed leaves recovered less following a 2-min high-temperature treatment at 46°C than did photosynthesis of leaves fed water or fosmidomycin-fed leaves in air supplemented with isoprene. Photosynthesis of Phaseolus vulgaris leaves, which do not make isoprene, exhibited increased thermotolerance when isoprene was supplied in the airstream flowing over the leaf. Other short-chain alkenes also improved thermotolerance, whereas alkanes reduced thermotolerance. It is concluded that thermotolerance of photosynthesis is a substantial benefit to plants that make isoprene and that this benefit explains why plants make isoprene. The effect may be a general hydrocarbon effect and related to the double bonds in the isoprene molecule.

Isoprene is made by many plants, especially trees (Sanadze, 1969; Rasmussen, 1970; Sharkey, 1996). As much as 500 terragrams year−1 is emitted globally from vegetation (Guenther et al., 1995), exceeding the total hydrocarbon input to the atmosphere from human activities (Wang and Shallcross, 2000). North American species of oaks (Quercus sp.), aspen (Populus sp.), and kudzu (Pueraria lobata [Willd.] Ohwi.) are typical isoprene-emitting species, whereas almost no crop species emit isoprene. Isoprene oxidation in the atmosphere can give rise to ozone and smog if nitrogen oxides are present in the atmosphere (Haagen-Smit, 1952; Daum et al., 2000). This has caused some people to label isoprene emission pollution (Rasmussen, 1972; Pope, 1980), though in otherwise clean environments, isoprene emission does not lead to ozone production (Trainer et al., 1987).

Isoprene is synthesized from dimethylallyl pyrophosphate by isoprene synthase (Silver and Fall, 1991; Silver and Fall, 1995). The dimethylallyl pyrophosphate is made by the deoxyxylulose 5-phosphate/methyl erithritol 4-phosphate pathway (Schwender et al., 1997; Lichtenthaler, 1999) and isoprene synthesis is the dominant product of this pathway in those plants that make isoprene (Sharkey et al., 1991). Isoprene is not stored nor metabolized in leaves, so emission reflects biosynthesis (Delwiche and Sharkey, 1993; P.J. Vanderveer and T.D. Sharkey, unpublished data).

It has been hypothesized that isoprene production helps photosynthesis cope with high temperature (Sharkey and Singsaas, 1995; Singsaas et al., 1997). In some species of oak, monoterpenes may also provide thermotolerance (Loreto et al., 1998; Delfine et al., 2000; Singsaas, 2000). The thermotolerance hypothesis for isoprene function has, up to now, rested on three pieces of evidence (Singsaas et al., 1997). All are indirect because of the need to control endogenous isoprene synthesis to demonstrate its effect. In addition, the high temperature dependence of isoprene emission rate and the long-term effect of temperature on isoprene emission capacity (Sharkey et al., 1999) are consistent with a role for isoprene in heat tolerance.

One of the methods used to demonstrate heat tolerance involved heating leaves in a pure N2 atmosphere (isoprene is not produced in the absence of CO2 and O2) and determining the temperature at which chlorophyll fluorescence increased, an indication of thermal damage to photosynthetic reactions. Singsaas et al. (1997) reported that in kudzu leaves without isoprene, fluorescence increased between 35°C and 40°C, whereas adding isoprene increased the temperature of thermal damage to 45°C. On the other hand, Phaseolus vulgaris leaves did not exhibit an increase in fluorescence until >45°C with or without isoprene. Logan and Monson (1999) reported that in four species, fluorescence of leaves held in nitrogen did not increase until the temperature exceeded 45°C regardless of the presence or absence of isoprene. They interpreted this to indicate “Thermotolerance … is not enhanced by exposure to exogenous isoprene,” but they did not address other experiments on which the thermotolerance hypothesis rests. Upon further experimentation, we conclude that the effect of isoprene when measured in a nitrogen atmosphere is important only below 45°C. If the control leaves do not show damage below 45°C, isoprene will have no effect. However, this does not indicate that isoprene does not provide thermotolerance. Chlorophyll fluorescence in a nitrogen atmosphere is an unnatural situation, originally used because there were no alternatives at the time. To explore the thermotolerance hypothesis further we developed more physiologically relevant methods by which to test the thermotolerance hypothesis.

Fosmidomycin was reported to inhibit deoxyxyluose-5-phosphate reductoisomerase, an enzyme in the methyl erithritol 4-phosphate pathway by which isoprene is made (Kuzuyama et al., 1998; Zeidler et al., 1998). Leaf pieces floated on fosmidomycin lose the ability to make isoprene (Zeidler et al., 1997). If the inhibition of isoprene were specific, fosmidomycin could provide a method of controlling the production of endogenous isoprene while examining thermotolerance of photosynthesis. In addition, we have refined the thermotolerance hypothesis (Singsaas and Sharkey, 1998). In the refined version, isoprene protects photosynthesis against short high-temperature episodes rather than providing general high-temperature tolerance. Therefore, thermotolerance provided by isoprene should be assessed by observing the recovery from short high-temperature episodes such as oak leaves experience in natural conditions (Singsaas et al., 1999).

Here we report that fosmidomycin inhibits isoprene emission of two important isoprene-emitting species, red oak (Quercus rubra) and kudzu, without inhibiting photosynthesis. We used fosmidomycin-fed leaves to investigate thermotolerance caused by isoprene. Thermotolerance was assessed as recovery of photosynthesis following a 2-min treatment at 46°C. This assay was also used to reexamine whether isoprene improves thermotolerance in P. vulgaris leaves, which do not emit isoprene. Finally, P. vulgaris leaves were used to examine the effect of other hydrocarbons related to isoprene on thermotolerance to determine what characteristic of the isoprene molecule is important for thermotolerance.

RESULTS

Fosmidomycin inhibited isoprene emission after less than 1 h of feeding through the petiole but had no significant effect on photosynthesis for several hours. This was found for both oak leaves (Fig. 1) and kudzu leaves (data not shown, similar to data of Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Gas exchange of an oak leaf before and after feeding 4 μm fosmidomycin through the transpiration stream. Squares denote isoprene emission (nmol m−2 s−1) and circles denote CO2 uptake (μmol m−2 s−1). The arrow indicates when fosmidomycin was added to the transpiration stream of the leaf. Leaf temperature was 30°C and light was 1,000 μmol m−2 s−1.

Thermotolerance was assessed as the recovery of photosynthesis following a short high-temperature episode. Photosynthesis of a detached leaf of kudzu fed water was inhibited between 50% and 100% by changing from 30°C to 46°C. Upon returning to 30°C, photosynthesis recovered almost completely. When the leaf was fed fosmidomycin to eliminate endogenous isoprene, photosynthesis fell by about two-thirds at 46°C and recovered less upon returning to 30°C. Adding 22 μL L−1 isoprene to the airstream passing over a fosmidomycin-fed leaf to replace the endogenous isoprene with exogenous isoprene caused the leaf to behave like the leaf fed only water (Table I). This last experiment controls for any effects fosmidomycin might have other than elimination of the endogenous source of isoprene. Similar results were found using red oak leaves (data not shown). Repeated high-temperature episodes continued to cause more reduction in photosynthesis of red oak leaves when isoprene was absent than when it was present (Fig. 2). We never detected an effect of isoprene on photosynthesis of leaves at 30°C before the heat stress was applied.

Table I.

Recovery of kudzu leaf photosynthesis from a high-temperature treatment

| Treatment | % Recovery |

|---|---|

| Water | 87 ± 7 |

| Fosmidomycin | 56 ± 11 |

| Fosmidomycin plus exogenous isoprene | 89 ± 17 |

Data are photosynthetic rate measured at 30°C 20 min after a short treatment at 46°C divided by the rate at 30°C before the treatment. Data are the mean ± se of three trials. Fosmidomycin was fed through the petiole at 4-μM concentration. Measurements commenced after gas chromatography analysis showed that >90% of the isoprene emission capacity had been lost.

Figure 2.

Photosynthesis of oak leaves. Leaves were detached and fed water (black circles) or 4 μm fosmidomycin (white circles). Leaves were heated to 46°C at a rate of 3°C per min, held at 46°C for 2 min, then returned to 30°C. The heat stress was applied three times. Data marked by arrows were measured at 46°C; all others were measured at 30°C.

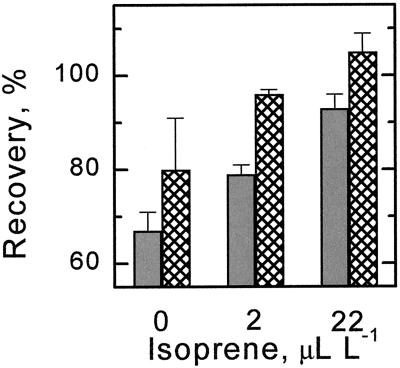

P. vulgaris leaves were tested next. Because this species does not normally emit isoprene, leaves were left attached to the plant and fosmidomycin was not used. To account for variation from leaf to leaf, adjacent leaflets were used, one heated with no added isoprene, one heated with 2 μL L−1 isoprene in the airstream, and one heated with 22 μL L−1 isoprene in the airstream. Recovery was assessed 1 and 24 h after the single heat stress episode. Recovery after 1 h was less than 70% without isoprene but greater than 90% with 22 μL L−1 isoprene; the 2-μL L−1 isoprene treatment had an intermediate response (Fig. 3). The day after the heat stress the isoprene effect was still evident with recoveries relative to the prestress measurement of photosynthesis of 80%, 96%, and 105% for the 0-, 2-, and 22-μL L−1 isoprene treatments. The recoveries of the treated leaves were divided by the recovery of the control leaf to give a recovery ratio. Recovery ratios after 1 h were 1.20 ± 0.08 for 2 μL L−1 and 1.42 ± 0.13 for 22 μL L−1 isoprene. After 24 h the ratios were 1.25 ± 0.19 for 2 μL L−1 and 1.36 ± 0.19 for 22 μL L−1. In other words, isoprene allowed 20% to 40% more recovery from a short high-temperature episode and this pattern was still evident the following day.

Figure 3.

Recovery of photosynthesis of leaves of P. vulgaris following a 2-min treatment of 46°C. Isoprene was supplied in the airstream. The gray bars are data obtained by dividing the rate of photosynthesis 1 h after the heat treatment by the rate measured before the heat treatment. The cross-hatched bars are data obtained by dividing the rate of photosynthesis measured 24 h after the heat treatment by the rate measured before the heat treatment. Each bar is the average of three determinations and the error bar is one se.

P. vulgaris leaves were used to test the effects of hydrocarbons similar to isoprene to determine what attributes of the isoprene molecule are important for thermotolerance. The recovery ratio for isoprene feeding was 1.13 in this series of experiments (Table II). Butadiene is similar to isoprene in having two double bonds but lacking the methyl that makes a branched chain. Butadiene substantially enhanced thermotolerance, more so than isoprene (Table II). 1-Butene and 2-cis butene have just one double bond and provided less thermotolerance than did butadiene with its two double bonds. Results with ethylene were highly variable so six trials were conducted but there was no indication of thermoprotection.

Table II.

Recovery ratio for photosynthesis in response to heating to 46°C for two min

| Compound | Recovery ratio |

|---|---|

| Isoprene (22 μL L−1) | 1.13 ± 0.02, n = 4 |

| Butadiene (22 μL L−1) | 1.77 ± 0.19, n = 3 |

| 1-Butene (22 μL L−1) | 1.19 ± 0.03, n = 3 |

| cis 2-Butene (22 μL L−1) | 1.32 ± 0.26, n = 3 |

| Ethylene (22 μL L−1) | 0.94 ± 0.40, n = 6 |

| 2-Methyl butane (7 μL L−1) | 0.69 ± 0.07, n = 3 |

| n-Butane (20 μL L−1) | 0.82 ± 0.08, n = 3 |

| Isobutane (20 μL L−1) | 0.84 ± 0.10, n = 3 |

Photosynthesis was measured at 30°C and 1,000 μmol photons m−2 s−1. The recovery of photosynthesis of the treated leaf upon returning to 30°C was divided by the recovery of the adjacent leaflet used as a control. In this way each replicate is from adjacent leaf material, eliminating effects of leaf-to-leaf variability. The order of the experiment (control or treated measured first) was varied. Data are reported as mean ± se.

2-Methylbutane (isoprene minus the double bonds) isobutane and n-butane aggravated the effect of high temperature. After the first experiment a lower concentration of 2-methylbutane was used because of its strong deleterious effect on recovery. At 30°C the alkanes were not inhibitory to photosynthesis; for example, the average photosynthetic rates of leaves before the heat treatment were 9.3 μmol m−2 s−1 in control and 9.1 μmol m−2 s−1 in methylbutane-treated leaves.

Butadiene was tested under more severe heat stress. Treating P. vulgaris leaves at 50°C caused visible damage in control leaves but butadiene could prevent nearly all of the visible damage (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Leaf of P. vulgaris showing control leaflet (A), leaflet heated to 50°C (B), and leaflet heated but in the presence of 22 μL L−1 2-butadine (C). The light areas of the middle leaflet indicate regions where cells have collapsed.

DISCUSSION

We confirm that fosmidomycin inhibits isoprene emission (Zeidler et al., 1998) and extend the result to show that fosmidomycin has no effect on photosynthesis over the short times used in these experiments. Although many inhibitors can block isoprene emission (Loreto and Sharkey, 1990), fosmidomycin is unique in inhibiting isoprene emission without inhibiting photosynthesis. This adds to the evidence that isoprene is made by the deoxyxylulose 5-phosphate pathway (Lichtenthaler, 1999). Moreover, this provided a system for testing the thermotolerance hypothesis of isoprene function in isoprene-emitting species under realistic conditions.

Feeding fosmidomycin until isoprene emission was essentially eliminated reduced thermotolerance. The thermotolerance could be recovered by adding isoprene to the airstream (Table I), confirming that the fosmidomycin effect on thermotolerance was the result of inhibition of isoprene synthesis rather than some other effect. Increased thermotolerance was seen in two important isoprene-emitting species, kudzu and oak. In these experiments thermotolerance was assessed as the ability of photosynthesis to recover from a brief high-temperature episode. This experiment is a realistic test of the effect of isoprene on thermotolerance of photosynthesis because leaves often experience these conditions at tops of trees.

Without isoprene, repeated high-temperature episodes continued to reduce photosynthesis (Fig. 2). As a result, after three high-temperature episodes photosynthesis was much higher in the presence of isoprene than in its absence. Monoterpenes have been shown to provide thermotolerance in a similar manner; specifically, the effect is greater after several high-temperature episodes (Loreto et al., 1998; Delfine et al., 2000). This emphasizes that isoprene and monoterpenes best protect against short, repeated high-temperature episodes. The taxonomic distribution of isoprene emission may reflect plants most likely to experience such heat transients as opposed to low temperature or uniformly high temperature (Hanson et al., 1999).

Unlike our previous report (Singsaas et al., 1997), the nonemitting plant P. vulgaris showed enhanced thermotolerance in the presence of isoprene in this new assay for thermotolerance. Protection of nonemitting species was also found with monoterpenes (Delfine et al., 2000). This indicates that the effects of isoprene are not limited to isoprene-emitting species and so isoprene-induced thermotolerance is probably a general phenomenon.

Data from hydrocarbons similar to isoprene indicate that alkenes provide thermotolerance, whereas alkanes aggravate heat damage. We speculate that the double bonds in isoprene are important for its protective effect. The two double bonds in 1,3-butadiene appeared to be more effective than 1-butene or cis 2-butene. Ethylene did not appear to provide thermotolerance. These results are consistent with isoprene acting in the bulk phase, presumably a membrane and likely the thylakoid membrane. It is unlikely that there is a specific binding site for isoprene. Perhaps isoprene can interact electronically with the double bonds of the thylakoid membrane fatty acids and stabilize them by resonance. This could explain why ethylene, which would not contribute resonance stabilization, had no effect. Others have shown that monoterpenes can also improve thermotolerance, perhaps by the same mechanism as isoprene (Loreto et al., 1998; Delfine et al., 2000).

Recent evidence indicates that thylakoid membranes can become leaky to protons at moderately high temperatures and that this may be responsible for inhibition of photosynthesis at temperatures lower than 45°C (Pastenes and Horton, 1996; Bukhov et al., 1999). Perhaps isoprene and other alkenes dissolve into membranes and prevent the formation of water channels that give rise to the leakiness that can occur at high temperature. The large size of the double bonds could allow alkenes to fill channels as they form at high temperature, preventing leakiness of the membranes. Isoprene and other alkenes alternatively could prevent the formation of non-bilayer lipid structures that have been reported for heat-stressed thylakoid membranes (Gounaris et al., 1984).

More severe temperature stress that causes damage to photosystem II and manganese release (Nash et al., 1985) may not be prevented by the presence of isoprene. This could explain why Logan and Monson (1999) did not observe thermotolerance in leaves that did not exhibit thermal damage below 45°C. It is unclear why alkanes should exacerbate thermal damage.

The protection against cell collapse and death shown in Figure 4 may indicate that protection of membranes from loss of integrity may be a general effect of short, unsaturated hydrocarbons. This adds to the information about the role of isoprenoids in membrane integrity including the roles of cholesterol (Demel et al., 1996) and carotenoids (Ourisson and Nakatani, 1994; Havaux and Tardy, 1996). Isoprene may be best suited to situations where the properties of the membrane need to be changed rapidly and reversibly, such as large leaves that rapidly heat up in sunlight and still air and then cool off when the wind increases, dozens or more times per day (Singsaas and Sharkey, 1998). Isoprene may provide a method for rapidly and reversibly changing the properties of membranes.

The benefits for plants that experience heat episodes like those used here are substantial and far exceed the carbon cost of production of isoprene emission (typically 2%–8% of photosynthesis [Monson and Fall, 1989; Loreto and Sharkey, 1990]). The exogenous concentrations of isoprene used in these experiments are within the range that have been calculated to occur inside chloroplasts (Singsaas et al., 1997). Thus, we conclude the physiological effect that explains isoprene emission from plants is protection against short, high-temperature episodes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Material

Kudzu (Pueraria lobata [Willd.] Ohwi.) was grown in 10-L pots in potting medium (Metro-Mix, Scotts Horticultural Products Co., Marysville, OH). Day length was 16 h with a peak photon flux of 400 μmol m−2 s−1 provided by a mix of metal halide and high-pressure sodium lamps. The plants were in a growth chamber with temperatures of 30°C/20°C (day/night) and humidity kept above 60%. Kudzu leaves were detached from the plant to feed fosmidomycin. Detaching the leaves by cutting the petiole often caused the leaf to lose its water supply resulting in low stomatal conductance, but we discovered that if a small section of stem were included with the detached leaf, this problem could be avoided. Phaseolus vulgaris L. var. Linden was grown in the same chamber but in 4-L pots. P. vulgaris leaves were not detached from the plants. Red oak (Quercus rubra) leaves were cut from small trees growing in a greenhouse (winter) or from sun-exposed branches of a large tree growing outside the lab (summer). It was not necessary to include any stem tissue with the detached oak leaves.

Gas Exchange

Gas exchange was carried out as described by Tennessen et al. (1994). Leaf temperature was measured with a copper-constantan thermocouple appressed against the abaxial surface of the leaf. All measurements were made at 30°C and 1,000 μmol photons m−2 s−1 unless otherwise indicated. Air supplied to the leaf was mixed from nitrogen, oxygen, and 5% (v/v) CO2 in air. The oxygen level was 20 kPa and CO2 was 35 Pa.

Hydrocarbons were added to the airstream by substituting nitrogen containing about 100 μL L−1 of the hydrocarbon for some portion of the nitrogen used to make up the air. The concentrations of the added hydrocarbons were measured by withdrawing a 5-mL sample from a port in the airstream flowing from the leaf chamber. This sample was injected into a gas chromatograph, separated using a 30-m DB5 microbore column, then detected by photoionization. Standards of each compound were made by a two-step dilution of liquid authentic standards except for 1,3-butadiene and 1-butene, which were handled as gases and dilutions made of pure gas in N2.

Leaf temperature was controlled by a combination of radiant heat load (without changes in photosynthetically active radiation), thermoelectric module control of cuvette temperature, and changes in the water bath temperature used to control the temperature of the thermoelectric modules.

Fosmidomycin was fed by placing the petiole of the leaf into a microfuge tube containing 4 μm fosmidomycin in water. The level of liquid in the microfuge tube was kept constant by adding water as required.

Hydrocarbons

Alkenes and alkanes were purchased from Aldrich Chemical Co. (Milwaukee, WI). 1,3-Butadiene and both butanes were handled as compressed gases, whereas all other hydrocarbons were handled as liquids. Ethylene was purchased from Scott Specialty gases (Plumsteadville, PA) at a concentration of 100 μL −1 in nitrogen and diluted with air from the gas exchange system.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Fosmidomycin was a gift from Fujisawa Chemical Co. (Osaka).

Footnotes

This research was supported by the National Science Foundation (grant no. IBN–9975482).

LITERATURE CITED

- Bukhov NG, Wiese C, Neimanis S, Heber U. Heat sensitivity of chloroplasts and leaves: leakage of protons from thylakoids and reversible activation of cyclic electron transport. Photosynth Res. 1999;59:81–93. [Google Scholar]

- Daum PH, Kleinman LI, Nunnermacker LJ, Lee YN, Springston SR, Newman L, Weinstein-Lloyd J, Valente RJ, Imhoff RE, Tanner RL. Analysis of O3 formation during a stagnation episode in central Tennessee in summer 1995. J Geo Res Atmos. 2000;105:9107–9119. [Google Scholar]

- Delfine S, Csiky O, Seufert G, Loreto F. Fumigation with exogenous monoterpenes of a non-isoprenoid-emitting oak (Quercus suber): monoterpene acquisition, translocation, and effect on the photosynthetic properties at high temperatures. New Phytol. 2000;146:27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Delwiche CF, Sharkey TD. Rapid appearance of 13 C in biogenic isoprene when 13 CO2 is fed to intact leaves. Plant Cell Environ. 1993;16:587–591. [Google Scholar]

- Demel RA, Kinsky SC, Kinsky BB, Van Deenen LL. Effects of temperature and cholesterol on the glucose permeability of liposomes prepared with natural and synthetic lecithins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;150:655–665. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(68)90055-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gounaris K, Brain APR, Quinn PJ, Williams WP. Structural reorganization of chloroplast thylakoid membranes in response to heat stress. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1984;766:198–208. [Google Scholar]

- Guenther A, Hewitt CN, Erickson D, Fall R, Geron C, Graedel T, Harley P, Klinger L, Lerdau M, McKay WA. A global model of natural volatile organic compound emissions. J Geophys Res. 1995;100:8873–8892. [Google Scholar]

- Haagen-Smit AJ. Chemistry and physiology of Los Angeles smog. Ind Eng Chem. 1952;44:1342–1346. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson DT, Swanson S, Graham LE, Sharkey TD. Evolutionary significance of isoprene emission from mosses. Am J Bot. 1999;86:634–639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havaux M, Tardy F. Temperature-dependent adjustment of the thermal stability of photosystem II in vivo: possible involvement of xanthophyll-cycle pigments. Planta. 1996;198:324–333. [Google Scholar]

- Kuzuyama T, Shimizu T, Takahashi S, Seto H. Fosmidomycin, a specific inhibitor of 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate reductoisomerase in the nonmevalonate pathway for terpenoid biosynthesis. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:7913–7916. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenthaler HK. The 1-deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate pathway of isoprenoid biosynthesis in plants. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1999;50:47–65. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.50.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan BA, Monson RK. Thermotolerance of leaf discs from four isoprene-emitting species is not enhanced by exposure to exogenous isoprene. Plant Physiol. 1999;120:821–825. doi: 10.1104/pp.120.3.821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loreto F, Förster A, Dürr M, Csiky O, Seufert G. On the monoterpene emission under heat stress and on the increased thermotolerance of leaves of Quercus ilex L. fumigated with selected monoterpenes. Plant Cell Environ. 1998;21:101–107. [Google Scholar]

- Loreto F, Sharkey TD. A gas-exchange study of photosynthesis and isoprene emission in Quercus rubra L. Planta. 1990;182:523–531. doi: 10.1007/BF02341027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monson RK, Fall R. Isoprene emission from Aspen leaves: the influence of environment and relation to photosynthesis and photorespiration. Plant Physiol. 1989;90:267–274. doi: 10.1104/pp.90.1.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nash D, Miyao M, Murata N. Heat inactivation of oxygen evolution in photosystem II particles and its acceleration by chloride depletion and exogenous manganese. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1985;807:127–133. [Google Scholar]

- Ourisson G, Nakatani Y. The terpenoid theory of the origin of cellular life: the evolution of terpenoids to cholesterol. Chem Biol. 1994;1:11–23. doi: 10.1016/1074-5521(94)90036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastenes C, Horton P. Effect of high temperature on photosynthesis in beans: I. Oxygen evolution and chlorophyll fluorescence. Plant Physiol. 1996;112:1245–1251. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.3.1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope C. The candidates and the issues. Sierra. 1980;65:15–17. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen RA. Isoprene: identified as a forest-type emission to the atmosphere. Environ Sci Technol. 1970;4:667–671. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen RA. What do the hydrocarbons from trees contribute to air pollution? J Air Pollut Control Assoc. 1972;22:537–543. doi: 10.1080/00022470.1972.10469676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanadze GA. Light-dependent excretion of molecular isoprene. Prog Photosynth Res. 1969;2:701–706. [Google Scholar]

- Schwender J, Zeidler J, Groner R, Muller C, Focke M, Braun S, Lichtenthaler FW, Lichtenthaler HK. Incorporation of 1-deoxy-D-xylulose into isoprene and phytol by higher plants and algae. FEBS Lett. 1997;414:129–134. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01002-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharkey TD. Isoprene synthesis by plants and animals. Endeavor. 1996;20:74–78. doi: 10.1016/0160-9327(96)10014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharkey TD, Loreto F, Delwiche CF. The biochemistry of isoprene emission from leaves during photosynthesis. In: Sharkey TD, Holland EA, Mooney HA, editors. Trace Gas Emissions from Plants. San Diego: Academic Press; 1991. pp. 153–184. [Google Scholar]

- Sharkey TD, Singsaas EL. Why plants emit isoprene. Nature. 1995;374:769. [Google Scholar]

- Sharkey TD, Singsaas EL, Lerdau MT, Geron C. Weather effects on isoprene emission capacity and applications in emissions algorithms. Ecol Appl. 1999;9:1132–1137. [Google Scholar]

- Silver GM, Fall R. Enzymatic synthesis of isoprene from dimethylallyl diphosphate in aspen leaf extracts. Plant Physiol. 1991;97:1588–1591. doi: 10.1104/pp.97.4.1588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver GM, Fall R. Characterization of aspen isoprene synthase, an enzyme responsible for leaf isoprene emission to the atmosphere. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:13010–13016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.22.13010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singsaas EL. Terpenes and the thermotolerance of photosynthesis. New Phytol. 2000;146:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Singsaas EL, Laporte MM, Shi J-Z, Monson RK, Bowling DR, Johnson K, Lerdau M, Jasentuliyana A, Sharkey TD. Leaf temperature fluctuation affects isoprene emission from red oak (Quercus rubra) leaves. Tree Physiol. 1999;19:917–924. doi: 10.1093/treephys/19.14.917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singsaas EL, Lerdau M, Winter K, Sharkey TD. Isoprene increases thermotolerance of isoprene-emitting species. Plant Physiol. 1997;115:1413–1420. doi: 10.1104/pp.115.4.1413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singsaas EL, Sharkey TD. The regulation of isoprene emission responses to rapid leaf temperature fluctuations. Plant Cell Environ. 1998;21:1181–1188. [Google Scholar]

- Tennessen DJ, Singsaas EL, Sharkey TD. Light emitting diodes as a light source for photosynthesis research. Photosynth Res. 1994;39:85–92. doi: 10.1007/BF00027146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trainer M, Williams EJ, Parrish DD, Buhr MP, Allwine EJ, Westberg HH, Fehsenfeld FC, Liu SC. Models and observations of the impact of natural hydrocarbons on rural ozone. Nature. 1987;329:705–707. [Google Scholar]

- Wang KY, Shallcross DE. Modelling terrestrial biogenic isoprene fluxes and their potential impact on global chemical species using a coupled LSM-CTM model. Atmos Environ. 2000;34:2909–2925. [Google Scholar]

- Zeidler J, Schwender J, Müller C, Wiesner J, Weidemeyer C, Beck E, Jomaa H, Lichtenthaler HK. Inhibition of the non-mevalonate 1-deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate pathway of plant isoprenoid biosynthesis by fosmidomycin. Z Naturforsch. 1998;53:980–986. [Google Scholar]

- Zeidler JG, Lichtenthaler HK, May HU, Lichtenthaler FW. Is isoprene emitted by plants synthesized via the novel isopentenyl pyrophosphate pathway? Z Naturforsch. 1997;52:15–23. [Google Scholar]