Abstract

Background: Systemic inflammation is a key factor in tumor growth. The Glasgow Prognostic Score (GPS) has a certain value in predicting the prognosis of lung cancer. However, these results still do not have a unified direction.

Methods: A systematic review and meta-analysis were performed to investigate the relationship between GPS and the prognosis of patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). We set patients as follows: GPS = 0 vs. GPS = 1 or 2, GPS = 0 vs. GPS = 1, GPS = 0 vs. GPS = 2. We collected the hazard ratio (HR) and the 95% confidence interval (CI).

Results: A total of 21 studies were included, involving 7333 patients. We observed a significant correlation with GPS and poor OS in NSCLC patients (HRGPS=0 vs. GPS=1 or 2 = 1.62, 95% CI: 1.27–2.07, p ≤ .001; HRGPS=0 vs GPS=1 = 2.14, 95% CI:1.31–3.49, p ≤ .001; HRGPS=0 vs. GPS=2 = 2.64, 95% CI: 1.45–4.82, p ≤ .001). Moreover, we made a subgroup analysis of surgery and stage. The results showed that when divided into GPS = 0 group and GPS = 1 or 2 group, the effect of high GPS on OS was more obvious in surgery (HR = 1.79, 95% CI: 1.08–2.97, p = .024). When GPS was divided into two groups (GPS = 0 and GPS = 1 or 2), the III-IV stage, higher GPS is associated with poor OS (HR = 1.73, 95% CI: 1.43–2.09, p ≤ .001). In the comparison of GPS = 0 and GPS = 1 group (HR = 1.56, 95% CI: 1.05–2.31, p = .026) and the grouping of GPS = 0 and GPS = 2(HR = 2.23, 95% CI: 1.17–4.26, p = .015), we came to the same conclusion.

Conclusion: For patients with NSCLC, higher GPS is associated with poor prognosis, and GPS may be a reliable prognostic indicator. The decrease of GPS after pretreatment may be an effective way to improve the prognosis of NSCLC.

Keywords: meta-analysis, non-small cell lung cancer, systematic review, prognostic, GPS

Introduction

The burden of cancer morbidity and mortality is growing rapidly around the world. The number of new deaths from lung cancer was 1,796,144, accounting for 1/5 (18.0%) of cancer deaths in 2020 (1). Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is an important histological type of primary bronchogenic carcinoma, which is one of the most common malignant tumors, accounting for more than 80% of the total number of lung cancer cases (2, 3). Therefore, it is very urgent to find some reliable and feasible indicators to evaluate the prognosis of patients with NSCLC, to guide individualized treatment and follow-up programs.

Current studies have shown that immune and nutritional status are highly correlated to the occurrence, progression, and the treatment response of cancer (4–6). Systemic inflammation leads to increased protein decomposition and progressive nutritional decline through catabolism. The inflammation parameter is a strong candidate index to predict the prognosis of cancer. The poor prognosis of patients with malignant tumors is often associated with immune-related systemic inflammatory response and malnutrition. Therefore, in recent years, some prognostic markers based on inflammation and nutrition have been introduced, including Glasgow Prognostic Score (GPS) (7), Modified Glasgow prognosis score (MGPS) (8), C-reactive protein-albumin ratio (CRP/ALB, CAR) (9), Prognostic nutrition index (PNI) (10, 11) and advanced lung cancer inflammation index (ALI) (12, 13) to predict the prognosis and survival of patients with lung cancer.

The GPS, which was first reported by Forrest et al., is used to predict the prognosis of patients with NSCLC. The GPS is based on circulating C-reactive protein (CRP) and serum albumin (ALB) levels. The definition of GPS was shown in Table 1 (14). Many scholars have conducted retrospective and prospective studies on the prognostic value of GPS in patients with NSCLC (7, 14–33). However, due to the difference in research design, sample size, and other influencing factors, the conclusions are not completely consistent, and the way of grouping according to GPS is not uniform. Therefore, we conducted this study to fully clarify the prognostic role of GPS in patients with NSCLC.

TABLE 1.

Description of the preoperative GPS.

| GPS | |

|---|---|

| CRP ≤10 mg/L and albumin ≥3.5 g/dl | 0 |

| CRP ≤10 mg/L and albumin <3.5 g/dl | 1 |

| CRP >10 mg/L and albumin ≥3.5 g/dl | 1 |

| CRP >10 mg/L and albumin <3.5 g/dl | 2 |

GPS, Glasgow Prognostic Score, CRP C-reactive protein.

Methods

Search Strategy

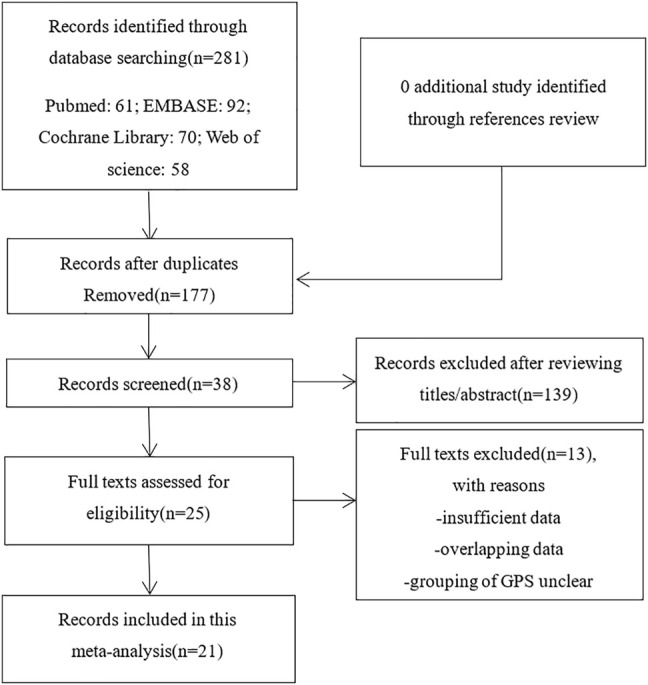

We explored the literature databases PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library for studies that may meet the criteria until April 2021. The search terms were set to “lung adenocarcinoma” OR “Non-Small Cell Lung cancer” OR “NSCLC” OR “LAD” OR “ADC” AND “Glasgow prognostic score”. Determine whether the literature is duplicated by using the author’s name, institution, clinical trial registry number, the number of participants, and baseline data. Among them, if there are studies reported by the same author, the latest and most complete publications would be chosen. Moreover, we manually searched the reference lists describing GPS and patients with NSCLC. The results were limited to humans and the English language. All results were imported into EndNote (Vision X9.2). The selecting process is to be briefed by complying with PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1) (34).

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of the study selection process.

Eligibility Criteria

The studies which were included must meet the following criteria: 1) prospective and retrospective study to investigate the prognostic effects of GPS on patients with NSCLC diagnosed by histopathological analysis. 2) the patients were graded strictly according to the definition of GPS(Table 1), and the cases were grouped clearly. 3) publication details were available and complete. 4) the research data provided were sufficient to calculate the hazard ratios (HRs) of the survival rate and its 95% confidence interval (CI). If the HRs cannot be obtained directly from the article, the Kaplan-Meier curve can be calculated (35). 5) the full text was available in English.

If one of the following criteria is met, the study is excluded: 1) reviews, case reports, conference abstracts, chapters of books, editorials, and edited letters or author corrections; 2) studies that cannot be used, such as duplication of data, high similarity of data, poor quality of literature, etc. 3) survival data of studies missing or impossible to calculate; 4) studies of animals. In addition, if the data subset is published in many articles, only the latest articles are included.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Design a standardized extraction table at first. The characteristics of included studies contented the last name of the first author, publication year, the country of the study, study type, sample size, patient’s age, gender, follow-up period, treatment, lung cancer type, and TNM stage. Two authors (KF and CLZ) independently assess the characteristics of selected studies. If there was disagreement, it would be resolved through discussions with the third researcher (BP). All the included studies were evaluated by Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) (36). The score of the scale is between 0 and 9. It is defined as a high-quality study when the score is ≥6.

Statistical Analysis

Pooled HRs and 95% CI is extracted from each study were used as indicators. We used Cochran’s Q test and Higgin’s I 2 statistics to evaluate the statistical heterogeneity between pooled studies. A 2-tailed α level of .05 was set as the threshold for statistical significance. If p < .05 and I2 > 50%, we will choose the random-effect model in this meta-analysis, otherwise the fixed-effect model will be performed (37). In addition, we have also conducted sensitivity analysis to verify the stability of the results.

Publication bias was evaluated using Begg’s statistical test and Egger’s statistical test. Statistical analysis was performed using STATA version 16.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, United States).

Results

Search Results and Basic Characteristics of the Included Studies

As mentioned above, we searched 281 records in online databases and references. After we deleted duplicates that were not related to GPS, we browsed the full text of the remaining 38 studies. Then, after further qualification evaluation, 25 studies were retained. Of these 25 studies, 2 were first excluded because of data duplication; the other 2 lacked relevant survival data. Finally, 21 studies were included in this analysis after cross-reference. There are no additional studies.

The characteristics of qualified studies are shown in Table 2. In included studies, 13 were conducted in Japan, 4 in China, 3 in the United States, and 1 in Australia. We conducted 21 studies involving a total of 7,333 patients with NSCLC. All 21 studies depicted the association between GPS and OS. Among them, the grouping method of 14 studies is divided into two groups: GPS = 0 and GPS = 1 or 2 (7, 14, 15, 17, 18, 20, 21, 23, 24, 27–29, 32, 33). Seven studies were compared twice, grouped by GPS = 0 and GPS = 1, GPS = 0 and GPS = 2 (16, 19, 22, 25, 26, 30, 31).

TABLE 2.

The basic characteristics of the included studies.

| Author | Year | Country | Study type | Sample size (N) | GPS = 0 | GPS = 1 | GPS = 2 | Age (years) | Gender (M/F) | Follow-up (months) | Stage | Treatment | Lung cancer type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forrest (7) | 2003 | United Kingdom | PO and RO | 161 | 27 | 101 | 33 | <60 (37); >60 (124) | 105/56 | NA | III–IV | Non-surgery (RT + CT) | Squamous (64); Adenocarcinoma (53); Others (44) |

| Forrest (14) | 2004 | United Kingdom | PO | 109 | 27 | 69 | 13 | <60 (41); >60 (68) | 63/46 | NA | III–IV | Non-surgery (CT) | Squamous (40); Adenocarcinoma (46); Others (23) |

| Forrest (33) | 2005 | United Kingdom | PO | 101 | 32 | 59 | 10 | <60 (18); >60 (83) | 62/39 | NA | III–IV | Non-surgery (NA) | NA |

| Miyazaki (29) | 2015 | Japan | RO | 97 | 65 | 25 | 7 | >80 | 62/35 | NA | I–IV | Surgery | NA |

| Fan (28) | 2016 | China | RO | 1745 | 668 | 647 | 430 | ≤55 (160); >55, ≤70 (754); >70 (831) | 1,217/528 | 20 (median) | I–IV | Non-surgery (CT) | NA |

| Yotsukura (24) | 2016 | Japan | RO | 1,048 | 817 | 184 | 47 | <65 (481); ≥65 (567) | 597/451 | NA | I–II | Surgery | Squamous (180); Adenocarcinoma (754); Others (114) |

| Miyazaki (23) | 2017 | Japan | RO | 108 | 99 | 4 | 5 | 82 (80–93) | 69/39 | NA | I–IV | Surgery | Adenocarcinoma (76); Others (32) |

| Tomita (21) | 2018 | Japan | RO | 341 | 191 | 112 | 38 | <65 (106); ≥65 (235) | 173/168 | NA | I–III | Surgery | Adenocarcinoma (268); Others (73) |

| Kasahara (20) | 2019 | Japan | RO | 47 | 24 | 6 | 17 | < 65 (14); ≥65 (33) | 37/10 | NA | I–IV | Non-surgery (IO) | Squamous (12); Others (35) |

| Kasahara (18) | 2020 | Japan | RO | 214 | 141 | 43 | 30 | <65 (62); ≥65 (152) | 83/131 | NA | I–IV | Non-surgery (EGFR-TKI) | Adenocarcinoma (212); Others (2) |

| Takamori (15) | 2021 | Japan | RO | 304 | 109 | 85 | 110 | <65 (104); ≥65 (208) | 242/62 | NA | IIIb–IV | Non-surgery (IO) | Squamous (74); Others (230) |

| Tomita (32) | 2014 | Japan | RO | 312 | 264 | 31 | 17 | <65 (104); ≥65 (208) | 192/129 | NA | I–III | Surgery | Adenocarcinoma (237); Others (75) |

| Lindenmann (17) | 2020 | Australia | PO | 300 | 229 | 68 | 3 | 65.4 ± 10.0 (20–87) | 187/113 | 38.1 ± 28.3 | I | Surgery | Squamous (95); Adenocarcinoma (191); Others (14) |

| Machida (27) | 2016 | Japan | RO | 156 | 136 | 16 | 4 | <65 (70); ≥65 (86) | 75/81 | 48.0 | IA–IIIA | Surgery | Adenocarcinoma |

| Kawashima (30) | 2015 | Japan | RO | 1,043 | 897 | 107 | 39 | NA | 671/372 | 36.0–60.0 | I–III | Surgery | Squamous (220); Adenocarcinoma (741); Others (82) |

| Jiang (31) | 2014 | China | PO | 138 | 95 | 32 | 11 | 55 (37–81) | 117/21 | 24.0–60.0 | IIIB–IV | Non-surgery (CT) | Squamous (67); Adenocarcinoma (48); Others (23) |

| Osugi (26) | 2016 | Japan | RO | 327 | 286 | 30 | 11 | ≤69 (171); >69 (156) | 199/128 | ≥60.0 | I–III | Surgery | Squamous (78); Adenocarcinoma (232); Others (17) |

| Su (25) | 2016 | China | PO | 207 | 49 | 111 | 47 | <60 (126); ≥60 (81) | 144/63 | NA | IIIA–IV | Non-surgery (CT) | Squamous (63); Adenocarcinoma (127); Others (17) |

| Ni (22) | 2018 | China | RO | 436 | NO | NO | NO | ≤62 (228); >62 (208) | 297/139 | NA | III–IV | Non-surgery (RT + CT) | Squamous (107); Others (329) |

| Topkan (19) | 2019 | Japan | RO | 83 | 42 | 22 | 19 | >70 | 49/34 | NA | IIIb | Non-surgery (RT + CT) | Squamous (47); Adenocarcinoma (36) |

| Kikuchi (16) | 2020 | Japan | RO | 56 | 31 | 16 | 9 | 71 (65–77) | 40/16 | NA | III–IV | NA | Squamous (25); Adenocarcinoma (28); Others (3) |

GPS, Glasgow Prognostic Score; N, numbers of studies; p, p-values of Q test; NA, not available; PO, prospective studies; RO, retrospective studies; CT, chemo therapy; RT, radiation therapy; IO, immunotherapy; EGFR-TKI, Epidermal growth factor receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

Qualitative Assessment

According to the evaluation of the NOS, all the included reports were considered high-quality (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Quality assessment based on the NOS.

| Study | Year | Selection | Comparability | Outcome | Total score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forrest (7) | 2003 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 8 |

| Forrest (14) | 2004 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 8 |

| Forrest (33) | 2005 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 8 |

| Miyazaki (29) | 2015 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 8 |

| Fan (28) | 2016 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 7 |

| Yotsukura (24) | 2016 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 8 |

| Miyazaki (23) | 2017 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 8 |

| Tomita (21) | 2018 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 8 |

| Kasahara (20) | 2019 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 8 |

| Kasahara (18) | 2020 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 8 |

| Takamori (15) | 2021 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 8 |

| Tomita (32) | 2014 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 8 |

| Lindenmann (17) | 2020 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 8 |

| Machida (27) | 2016 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 8 |

| Kawashima (30) | 2015 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 8 |

| Jiang (31) | 2014 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 8 |

| Osugi (26) | 2016 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 8 |

| Su (25) | 2016 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 8 |

| Ni (22) | 2018 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 8 |

| Topkan (19) | 2019 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 |

| Kikuchi (16) | 2020 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 |

NOS, Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale.

Meta-Analysis Results

Overall Survival

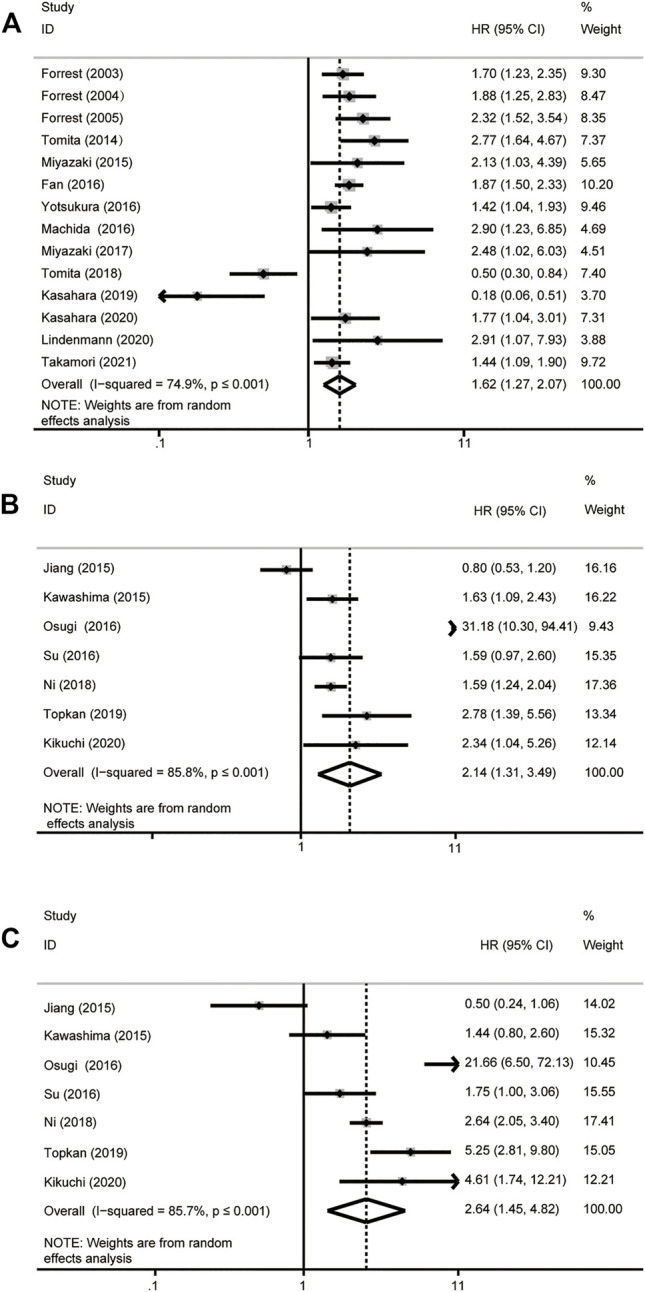

A total of 21 studies including 7,333 patients were included in the analysis of HR for OS (Supplementary Table S1). We choose the random-effect model (I 2 > 50%, p ≤ .001). The results showed that higher GPS is associated with poor OS in patients with NSCLC. The grouping method of 14 studies is divided into two groups: GPS = 0 and GPS = 1 or 2, of which results showed that there is a significant correlation between GPS and OS (HR = 1.62, 95% CI: 1.27–2.07, p ≤ .001) (Figure 2A). The results of the other 7 studies revealed that higher GPS was related to the poor OS (HRGPS=0 vs. GPS=1 = 2.14, 95% CI: 1.31–3.49, p ≤ .001; HRGPS=0 vs. GPS=2 = 2.64, 95% CI: 1.45–4.82, p ≤ .001) (Figures 2B,C).

FIGURE 2.

Forest plot of overall survival analysis. (A) GPS = 0 vs GPS = 1 or 2. (B) GPS = 0 vs GPS = 1. (C) GPS = 0 vs GPS = 2. HR, hazard ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Subgroup Analyses

Furthermore, subgroup analysis was performed according to whether or not surgery and different stages to detect the prognostic value of GPS in patients with NSCLC. We found that when the GPS = 0 group was compared with the GPS = 1 or 2 group, the effect of high GPS on OS was more significant in surgery patients (HR = 1.79, 95% CI: 1.08–2.97, p = .024). However, the influence of high GPS on OS of surgical patients was more significant (HRGPS=0 vs GPS=1 = 6.80, 95% CI: .38–122.45; HRGPS=0 vs. GPS=2 = 5.31, 95% CI: .37–75.45), the result compared with the non-surgery group was not statistically significant (PGPS=0 vs. GPS=1 = .194; PGPS=0 vs. GPS=2 = .218). After the subgroup analysis of the stage, for patients with NSCLC, we found that when the GPS = 0 group was compared with the GPS = 1 or 2 group, the effect of high GPS on poor OS was the most obvious in the III-IV stage (HR = 1.73, 95% CI: 1.43–2.09, p ≤ .001) than in other stages. In the comparison of GPS = 0 and GPS = 1 group (HR = 1.56, 95% CI: 1.05–2.31, p = .026) and the grouping of GPS = 0 and GPS = 2(HR = 2.23, 95% CI: 1.17–4.26, p = .015), we came to the same conclusion. However, there was no significance during the I-III period when the GPS = 0 group was compared with the GPS = 1 group (p = .194) or the GPS = 0 group was compared with the GPS = 2 group (p = .218) (Table 4). Therefore, we consider that the stage of NSCLC and whether or not surgery may be the source of heterogeneity.

TABLE 4.

The subgroup analysis according to whether or not surgery and different stages.

| Group | Analysis | N | References | Random-effects model | Heterogeneity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95%CI) | p | I 2 (%) | p | ||||

| GPS = 0 vs. GPS = 1 or 2 | Subgroup 1 | ||||||

| Surgery | 7 | (17, 21, 23, 24, 27, 29, 32) | 1.79 (1.08–2.97) | .024 | 79.00 | ≤.001 | |

| Non-surgery | 7 | (7, 14, 15, 18, 20, 28, 33) | 1.59 (1.21–2.10) | ≤.001 | 73.20 | ≤.001 | |

| Subgroup 2 | |||||||

| Stage I–II | 2 | (17, 24) | 1.72 (.92–3.22) | .087 | 44.50 | .180 | |

| Stage I–III | 3 | (21, 27, 32) | 1.56 (.45–5.35) | .482 | 91.80 | ≤.001 | |

| Stage III–IV | 4 | (7, 14, 15, 33) | 1.73 (1.43–2.09) | ≤.001 | 18.40 | .299 | |

| Stage I–IV | 5 | (18, 20, 23, 28, 29) | 1.41 (.78–2.52) | .251 | 79.60 | ≤.001 | |

| GPS = 0 vs GPS = 1 | Subgroup 1 | ||||||

| Surgery | 2 | (26, 30) | 6.80 (.38–122.45) | .194 | 95.90 | ≤.001 | |

| Non-surgery | 4 | (19, 22, 25, 31) | 1.47 (.95–2.26) | .082 | 75.60 | .006 | |

| Subgroup 2 | |||||||

| Stage I–III | 2 | (26, 30) | 6.80 (.38–122.45) | .194 | 95.90 | .009 | |

| Stage III–IV | 5 | (16, 19, 22, 25, 31) | 1.56 (1.05–2.31) | .026 | 70.70 | ≤.001 | |

| GPS = 0 vs GPS = 2 | Subgroup 1 | ||||||

| Surgery | 2 | (26, 30) | 5.31 (.37–75.45) | .218 | 95.10 | ≤.001 | |

| Non-surgery | 4 | (19, 22, 25, 31) | 1.83 (.73–4.57) | .195 | 94.70 | ≤.001 | |

| Subgroup 2 | |||||||

| Stage I–III | 2 | (26, 30) | 5.30 (.37–75.32) | .218 | 93.60 | ≤.001 | |

| Stage III–IV | 5 | (16, 19, 22, 25, 31) | 2.23 (1.17–4.26) | .015 | 84.70 | ≤.001 | |

GPS, Glasgow Prognostic Score; N, number of studies; HR, hazard ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval, p, p-values of Q test; OS, overall survival; VS, versus.

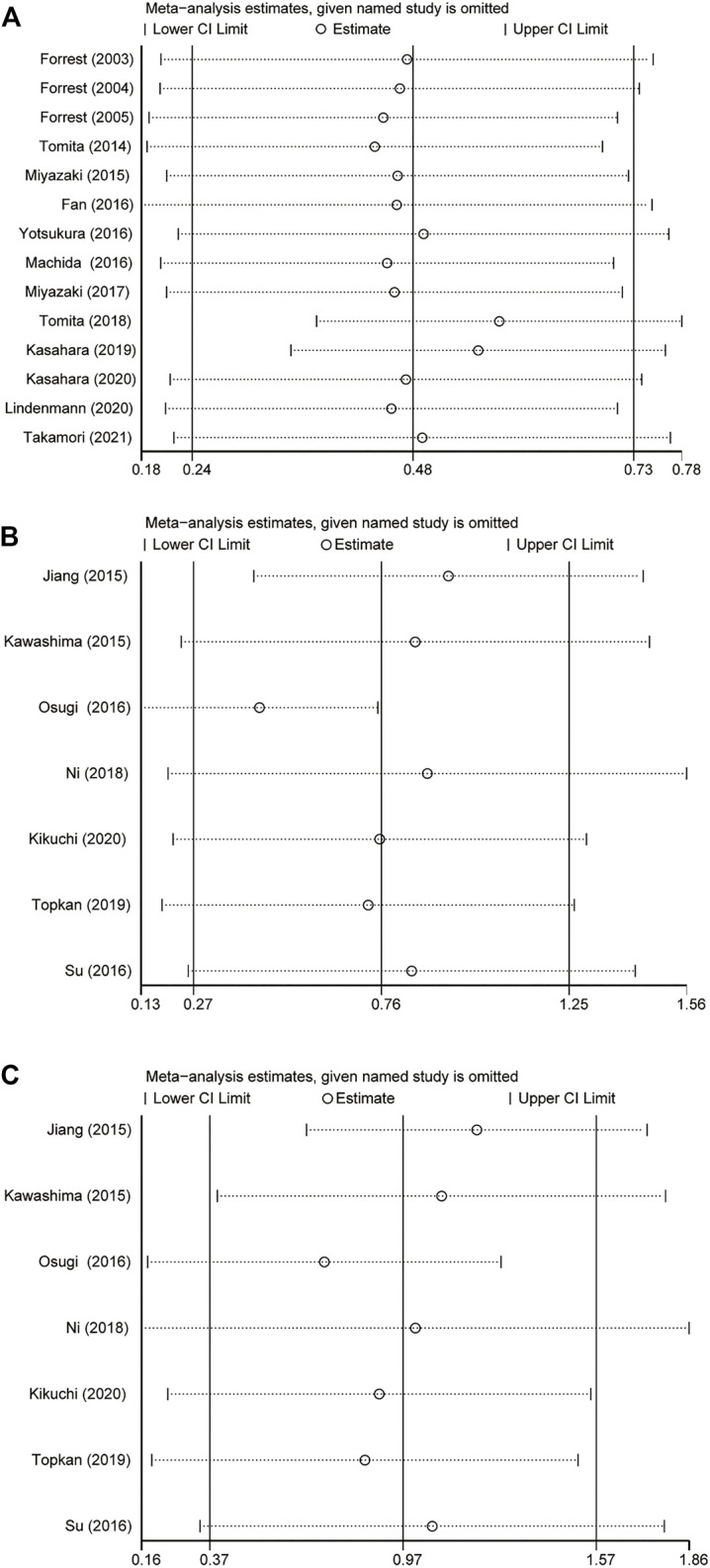

Sensitivity Analysis

The results showed that excluding any single literature had no significant effect on the collection of HR after sensitivity analysis of 21 studies. This shows that our analysis results were robust (Figures 3A–C).

FIGURE 3.

Result of sensitivity analyses by omitting one study in each turn. (A) GPS = 0 vs GPS = 1 or 2. (B) GPS = 0 vs GPS = 1. (C) GPS = 0 vs GPS = 2. GPS, Glasgow Prognostic Score; 95% CI, 95% Confidence Interval.

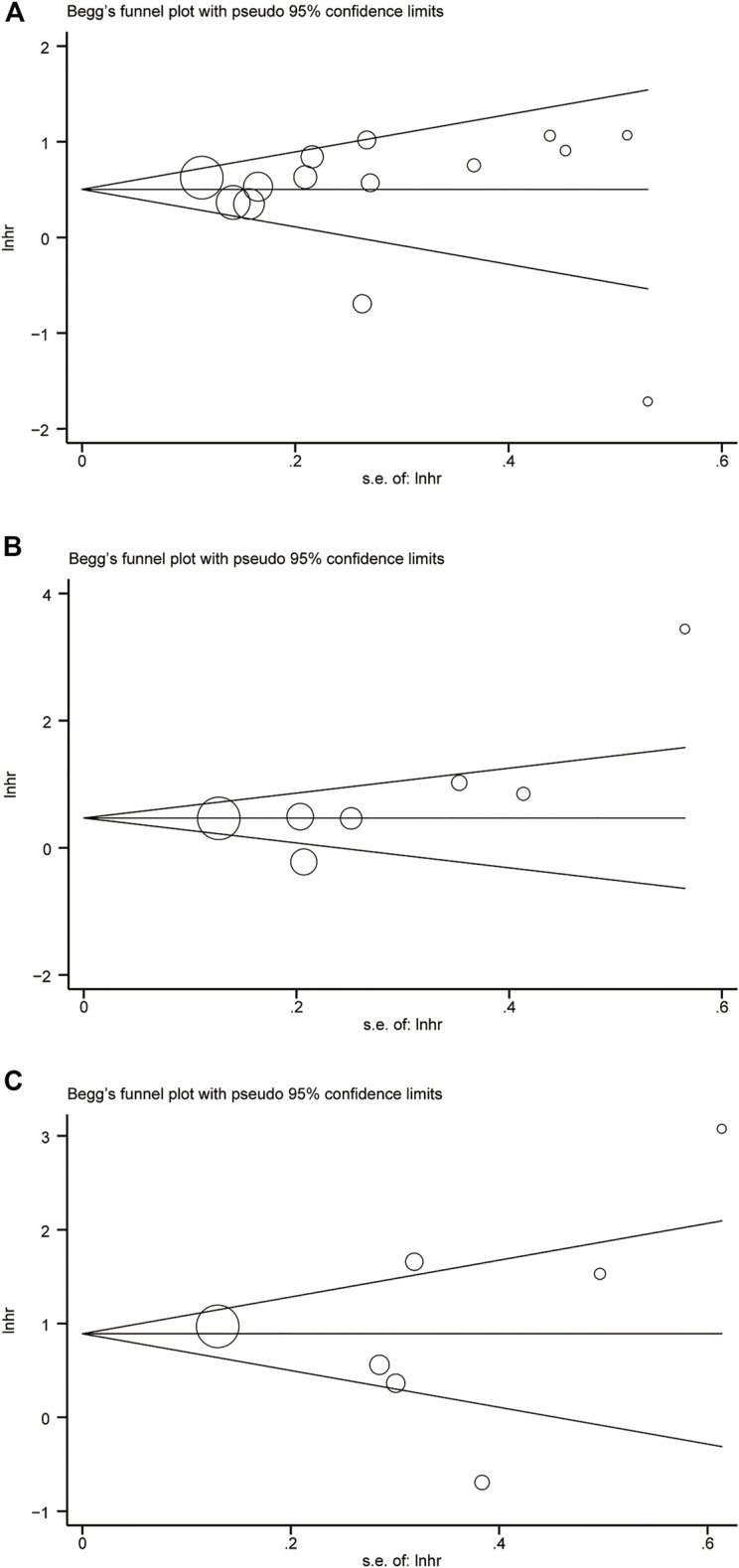

Publication Bias Assessment

Considering the risk of bias may affect the results of meta-analysis, assessment of potential publication bias using Begg’s funnel chart and Egger’s test. The results showed that the two methods did not produce bias, which proves the reliability of the results (Figures 4A–C).

FIGURE 4.

Begg’s funnel plot. (A) GPS = 0 vs GPS = 1 or 2. (B) GPS = 0 vs GPS = 1. (C) GPS = 0 vs GPS = 2.

Discussion

NSCLC as a kind of cancer with high morbidity and mortality seriously endangers people’s health and quality of life. At present, there is more and more evidence that systemic inflammatory response and systemic immune response defects play an important role in cancer invasion and progression (38). Although inflammation-related prognostic indicators have received some attention in NSCLC, the mechanism of the survival relationship between them is not clear, which may be related to malnutrition, immunodeficiency, up-regulation of growth factors, or angiogenesis.

CRP is a representative acute phase reaction, its level increases rapidly in inflammation, and is considered to be one of the most widely used indicators of systemic inflammation. Many studies have proved that CRP plays an important role in the diagnosis and prognosis of NSCLC (39–42). ALB is the most commonly used to evaluate nutritional status, and low ALB in patients with NSCLC usually indicates weight loss and malnutrition (43–45). In addition, as early as 2001, Mcmillan found that the increase of CRP concentration in circulation was always accompanied by the decrease of ALB concentration (46). Therefore, systemic inflammation may affect the concentration of serum ALB. The relationship between CRP and ALB was proposed by Forrest et al. For the first time, they combined CRP and serum ALB as prognostic scores, and confirmed their prognostic value in patients with NSCLC (13), which was defined as Glasgow prognostic score (47). Gradually, the value of GPS in predicting prognosis has been confirmed in many studies.

High GPS is highly related to the poor prognosis of many different types of tumors, but its value in the prognosis of patients with NSCLC is still contentious (15, 16). This study was a relatively comprehensive meta-analysis to investigate the value of GPS in predicting the prognosis for patients with NSCLC. In this study, we performed a meta-analysis including 21 studies with a total of 7,333 patients. As far as we know, this is the first meta-analysis that the GPS group divided into GPS = 0 with GPS = 1 or 2, GPS = 1 with GPS = 2, and GPS = 0 with GPS = 2. The OS of patients with NSCLC was evaluated by comparing the HRs between different groups to explore the relationship between GPS and OS. In addition, we also conducted a subgroup analysis of treatment and stage, which better demonstrated the prognostic value of GPS in patients with NSCLC.

The results of the study showed that high GPS predicted a poor OS in patients with NSCLC. Subgroup analysis was according to surgery and stage showed that GPS = 1 or 2 was more likely to predict poor OS in patients undergoing surgery. Moreover, based on the results of subgroup analysis of stage, we had reason to believe that the prognostic value of GPS was more significant in NSCLC patients with III-IV stage. When GPS = 1 or 2, patients undergoing surgery would face worse OS than patients without surgery, suggesting that clinicians should pay attention to the inflammatory status and nutritional status of patients during treatment. This is also the biggest difference between our study and Jin et al. (48), whose study is the antecedent of our study and shows that the association between MGPS and poor OS is not significant in patients undergoing surgery. This difference may be due to the fact that some patients with GPS = 1 are included in patients with MGPS = 0. For patients with NSCLC who have undergone surgery, the use of GPS to predict prognosis may be more sensitive than the use of MGPS to evaluate. This is worthy of further study. Anyway, controlling inflammation and improving nutritional status as far as possible is one of the key measures to ensure a good prognosis of patients with NSCLC.

Our study has certain limitations. Firstly, Japanese and Chinese studies accounted for the vast majority of included studies, which led to selection bias. Secondly, in the literature selection, we only chose the research that could obtain the full text in English. This may lead to language bias. Thirdly, there were many differences in measuring CRP and ALB levels, such as the time, place, method, and personnel of the measurement. However, sensitivity analysis showed that the results of this meta-analysis were reliable at least. Finally, since only 4 studies reported the prognostic role of progress-free survival (PFS), we did not analyze PFS, which meant that there were limitations in the selection of prognostic indicators. Therefore, in our meta-analysis, potential heterogeneity may be inevitable. Well-designed studies and repeated measurements in a larger population may help to evaluate the prognostic value and other clinical significance of GPS in NSCLC.

Conclusion

For patients with NSCLC, higher GPS is associated with a poor prognosis. GPS is an independent risk factor for OS and maybe a reliable prognostic indicator in NSCLC. The decrease of GPS after pretreatment may be an effective way to improve the prognosis of NSCLC.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

The study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (General Program) (81873399); Special Youth Talent Project for Health Development and Scientific Research in the Capital (2018-4-4154).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.por-journal.com/articles/10.3389/pore.2022.1610109/full#supplementary-material

References

- 1. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA A Cancer J Clin (2021) 71:209–49. 10.3322/caac.21660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Barta JA, Powell CA, Wisnivesky JP. Global Epidemiology of Lung Cancer. Ann Glob Health (2019) 85. 10.5334/aogh.2419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2021. CA A Cancer J Clin (2021) 71:7–33. 10.3322/caac.21654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chan JE, Mann AK, Kapp DS, Rehkopf DH. Income, Inflammation and Cancer Mortality: a Study of U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Mortality Follow-Up Cohorts. BMC Public Health (2020) 20:1805. 10.1186/s12889-020-09923-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zitvogel L, Pietrocola F, Kroemer G. Nutrition, Inflammation and Cancer. Nat Immunol (2017) 18:843–50. 10.1038/ni.3754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McMillan DC. Systemic Inflammation, Nutritional Status and Survival in Patients with Cancer. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care (2009) 12:223–6. 10.1097/MCO.0b013e32832a7902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Forrest LM, McMillan DC, McArdle CS, Angerson WJ, Dunlop DJ. Evaluation of Cumulative Prognostic Scores Based on the Systemic Inflammatory Response in Patients with Inoperable Non-small-cell Lung Cancer. Br J Cancer (2003) 89:1028–30. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kishi T, Matsuo Y, Ueki N, Iizuka Y, Nakamura A, Sakanaka K, et al. Pretreatment Modified Glasgow Prognostic Score Predicts Clinical Outcomes after Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy for Early-Stage Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. Int J Radiat Oncology*Biology*Physics (2015) 92:619–26. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2015.02.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yang J-R, Xu J-Y, Chen G-C, Yu N, Yang J, Zeng D-X, et al. Post-diagnostic C-Reactive Protein and Albumin Predict Survival in Chinese Patients with Non-small Cell Lung Cancer: a Prospective Cohort Study. Sci Rep (2019) 9:8143. 10.1038/s41598-019-44653-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shoji F, Matsubara T, Kozuma Y, Haratake N, Akamine T, Takamori S, et al. Preoperative Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index: A Predictive and Prognostic Factor in Patients with Pathological Stage I Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. Surg Oncol (2017) 26:483–8. 10.1016/j.suronc.2017.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Watanabe I, Kanauchi N, Watanabe H. Preoperative Prognostic Nutritional index as a Predictor of Outcomes in Elderly Patients after Surgery for Lung Cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol (2018) 48:382–7. 10.1093/jjco/hyy014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mandaliya H, Jones M, Oldmeadow C, Nordman IIC. Prognostic Biomarkers in Stage IV Non-small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC): Neutrophil to Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR), Lymphocyte to Monocyte Ratio (LMR), Platelet to Lymphocyte Ratio (PLR) and Advanced Lung Cancer Inflammation index (ALI). Transl Lung Cancer Res (2019) 8:886–94. 10.21037/tlcr.2019.11.16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jafri SH, Shi R, Mills G. Advance Lung Cancer Inflammation index (ALI) at Diagnosis Is a Prognostic Marker in Patients with Metastatic Non-small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC): a Retrospective Review. BMC Cancer (2013) 13:158. 10.1186/1471-2407-13-158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Forrest LM, McMillan DC, McArdle CS, Angerson WJ, Dunlop DJ. Comparison of an Inflammation-Based Prognostic Score (GPS) with Performance Status (ECOG) in Patients Receiving Platinum-Based Chemotherapy for Inoperable Non-small-cell Lung Cancer. Br J Cancer (2004) 90:1704–6. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Takamori S, Takada K, Shimokawa M, Matsubara T, Fujishita T, Ito K, et al. Clinical Utility of Pretreatment Glasgow Prognostic Score in Non-small-cell Lung Cancer Patients Treated with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Lung Cancer (2021) 152:27–33. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2020.11.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kikuchi R, Takoi H, Tsuji T, Nagatomo Y, Tanaka A, Kinoshita H, et al. Glasgow Prognostic Score Predicts Chemotherapy‐triggered Acute Exacerbation‐interstitial Lung Disease in Patients with Non‐small Cell Lung Cancer. Thorac Cancer (2021) 12:667–75. 10.1111/1759-7714.13792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lindenmann J, Fink-Neuboeck N, Taucher V, Pichler M, Posch F, Brcic L, et al. Prediction of Postoperative Clinical Outcomes in Resected Stage I Non-small Cell Lung Cancer Focusing on the Preoperative Glasgow Prognostic Score. Cancers (2020) 12:152. 10.3390/cancers12010152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kasahara N, Imai H, Naruse I, Tsukagoshi Y, Kotake M, Sunaga N, et al. Glasgow Prognostic Score Predicts Efficacy and Prognosis in Patients with Advanced Non‐small Cell Lung Cancer Receiving EGFR‐TKI Treatment. Thorac Cancer (2020) 11:2188–95. 10.1111/1759-7714.13526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Topkan E, Bolukbasi Y, Ozdemir Y, Besen AA, Mertsoylu H, Selek U. Prognostic Value of Pretreatment Glasgow Prognostic Score in Stage IIIB Geriatric Non-small Cell Lung Cancer Patients Undergoing Radical Chemoradiotherapy. J Geriatr Oncol (2019) 10:567–72. 10.1016/j.jgo.2018.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kasahara N, Sunaga N, Tsukagoshi Y, Miura Y, Sakurai R, Kitahara S, et al. Post-treatment Glasgow Prognostic Score Predicts Efficacy in Advanced Non-small-cell Lung Cancer Treated with Anti-PD1. Anticancer Res (2019) 39:1455–61. 10.21873/anticanres.13262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tomita M, Ayabe T, Maeda R, Nakamura K. Comparison of Inflammation-Based Prognostic Scores in Patients Undergoing Curative Resection for Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. World J Oncol (2018) 9:85–90. 10.14740/wjon1097w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ni X-F, Wu J, Ji M, Shao Y-J, Xu B, Jiang J-T, et al. Effect of C-Reactive Protein/albumin Ratio on Prognosis in Advanced Non-small-cell Lung Cancer. Asia-pac J Clin Oncol (2018) 14:402–9. 10.1111/ajco.13055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Miyazaki T, Yamasaki N, Tsuchiya T, Matsumoto K, Kunizaki M, Kamohara R, et al. Ratio of C-Reactive Protein to Albumin Is a Prognostic Factor for Operable Non-small-cell Lung Cancer in Elderly Patients. Surg Today (2017) 47:836–43. 10.1007/s00595-016-1448-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yotsukura M, Ohtsuka T, Kaseda K, Kamiyama I, Hayashi Y, Asamura H. Value of the Glasgow Prognostic Score as a Prognostic Factor in Resectable Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol (2016) 11:1311–8. 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.04.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Su K, Wang X, Chi L, Liu Y, Jin L, Li W. High glasgow Prognostic Score Associates with a Poor Survival in Chinese Advanced Non-small Cell Lung Cancer Patients Treated with Platinum-Based First-Line Chemotherapy. Int J Clin Exp Med (2016) 9:16353–9. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Suzuki H, Osugi J, Muto S, Matsumura Y, Higuchi M, Gotoh M. Prognostic Impact of the High-Sensitivity Modified Glasgow Prognostic Score in Patients with Resectable Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. J Can Res Ther (2016) 12:945–51. 10.4103/0973-1482.176168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Machida Y, Sagawa M, Tanaka M, Motono N, Matsui T, Usuda K, et al. Postoperative Survival According to the Glasgow Prognostic Score in Patients with Resected Lung Adenocarcinoma. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev (2016) 17:4677–80. 10.22034/apjcp.2016.17.10.4677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fan H, Shao Z-Y, Xiao Y-Y, Xie Z-H, Chen W, Xie H, et al. Comparison of the Glasgow Prognostic Score (GPS) and the Modified Glasgow Prognostic Score (mGPS) in Evaluating the Prognosis of Patients with Operable and Inoperable Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol (2016) 142:1285–97. 10.1007/s00432-015-2113-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Miyazaki T, Yamasaki N, Tsuchiya T, Matsumoto K, Kunizaki M, Taniguchi D, et al. Inflammation-based Scoring Is a Useful Prognostic Predictor of Pulmonary Resection for Elderly Patients with Clinical Stage I Non-small-cell Lung Cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg (2015) 47:e140–e145. 10.1093/ejcts/ezu514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kawashima M, Murakawa T, Shinozaki T, Ichinose J, Hino H, Konoeda C, et al. Significance of the Glasgow Prognostic Score as a Prognostic Indicator for Lung Cancer Surgery. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg (2015) 21:637–43. 10.1093/icvts/ivv223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jiang A-G, Lu H-Y. The Glasgow Prognostic Score as a Prognostic Factor in Patients with Advanced Non-small Cell Lung Cancer Treated with Cisplatin-Based First-Line Chemotherapy. J Chemother (2015) 27:35–9. 10.1179/1973947814Y.0000000188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tomita M, Ayabe T, Chosa E, Nakamura K. Prognostic Significance of Pre- and Postoperative glasgow Prognostic Score for Patients with Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. Anticancer Res (2014) 34:3137–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Forrest LM, McMillan DC, McArdle CS, Angerson WJ, Dagg K, Scott HR. A Prospective Longitudinal Study of Performance Status, an Inflammation-Based Score (GPS) and Survival in Patients with Inoperable Non-small-cell Lung Cancer. Br J Cancer (2005) 92:1834–6. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: the PRISMA Statement. BMJ (2009) 339:b2535. 10.1136/bmj.b2535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tierney JF, Stewart LA, Ghersi D, Burdett S, Sydes MR. Practical Methods for Incorporating Summary Time-To-Event Data into Meta-Analysis. Trials (2007) 8:16. 10.1186/1745-6215-8-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Stang A. Critical Evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for the Assessment of the Quality of Nonrandomized Studies in Meta-Analyses. Eur J Epidemiol (2010) 25:603–5. 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring Inconsistency in Meta-Analyses. BMJ (2003) 327:557–60. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Diakos CI, Charles KA, McMillan DC, Clarke SJ. Cancer-related Inflammation and Treatment Effectiveness. Lancet Oncol (2014) 15:e493–e503. 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70263-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sin DD, Man SFP, McWilliams A, Lam S. Progression of Airway Dysplasia and C-Reactive Protein in Smokers at High Risk of Lung Cancer. Am J Respir Crit Care Med (2006) 173:535–9. 10.1164/rccm.200508-1305OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zhou B, Liu J, Wang Z-M, Xi T. C-reactive Protein, Interleukin 6 and Lung Cancer Risk: a Meta-Analysis. PLoS One (2012) 7:e43075. 10.1371/journal.pone.0043075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Xu M, Zhu M, Du Y, Yan B, Wang Q, Wang C, et al. Serum C-Reactive Protein and Risk of Lung Cancer: a Case-Control Study. Med Oncol (2013) 30:319. 10.1007/s12032-012-0319-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Pletnikoff PP, Laukkanen JA, Tuomainen T-P, Kauhanen J, Rauramaa R, Ronkainen K, et al. Cardiorespiratory Fitness, C-Reactive Protein and Lung Cancer Risk: A Prospective Population-Based Cohort Study. Eur J Cancer (2015) 51:1365–70. 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.04.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tolia M, Tsoukalas N, Kyrgias G, Mosa E, Maras A, Kokakis I, et al. Prognostic Significance of Serum Inflammatory Response Markers in Newly Diagnosed Non-small Cell Lung Cancer before Chemoirradiation. Biomed Res Int (20152015) 2015:1–5. 10.1155/2015/485732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Li S-Q, Jiang Y-H, Lin J, Zhang J, Sun F, Gao Q-F, et al. Albumin-to-fibrinogen Ratio as a Promising Biomarker to Predict Clinical Outcome of Non-small Cell Lung Cancer Individuals. Cancer Med (2018) 7:1221–31. 10.1002/cam4.1428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Li X, Qin S, Sun X, Liu D, Zhang B, Xiao G, et al. Prognostic Significance of Albumin-Globulin Score in Patients with Operable Non-small-cell Lung Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol (2018) 25:3647–59. 10.1245/s10434-018-6715-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. McMillan DC, Watson WS, O'Gorman P, Preston T, Scott HR, McArdle CS. Albumin Concentrations Are Primarily Determined by the Body Cell Mass and the Systemic Inflammatory Response in Cancer Patients with Weight Loss. Nutr Cancer (2001) 39:210–3. 10.1207/S15327914nc392_8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. McMillan DC. The Systemic Inflammation-Based Glasgow Prognostic Score: a Decade of Experience in Patients with Cancer. Cancer Treat Rev (2013) 39:534–40. 10.1016/j.ctrv.2012.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Jin J, Hu K, Zhou Y, Li W. Clinical Utility of the Modified Glasgow Prognostic Score in Lung Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. PLoS One (2017) 12:e0184412. 10.1371/journal.pone.0184412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.