Summary

Background

Intimate partner violence against women is a global public health problem with many short-term and long-term effects on the physical and mental health of women and their children. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) call for its elimination in target 5.2. To monitor governments' progress towards SDG target 5.2, this study aimed to provide global, regional, and country baseline estimates of physical or sexual, or both, violence against women by male intimate partners.

Methods

This study developed global, regional, and country estimates, based on data from the WHO Global Database on Prevalence of Violence Against Women. These data were identified through a systematic literature review searching MEDLINE, Global Health, Embase, Social Policy, and Web of Science, and comprehensive searches of national statistics and other websites. A country consultation process identified additional studies. Included studies were conducted between 2000 and 2018, representative at the national or sub-national level, included women aged 15 years or older, and used act-based measures of physical or sexual, or both, intimate partner violence. Non-population-based data, including administrative data, studies not generalisable to the whole population, studies with outcomes that only provided the combined prevalence of physical or sexual, or both, intimate partner violence with other forms of violence, and studies with insufficient data to allow extrapolation or imputation were excluded. We developed a Bayesian multilevel model to jointly estimate lifetime and past year intimate partner violence by age, year, and country. This framework adjusted for heterogeneous age groups and differences in outcome definition, and weighted surveys depending on whether they were nationally or sub-nationally representative. This study is registered with PROSPERO (number CRD42017054100).

Findings

The database comprises 366 eligible studies, capturing the responses of 2 million women. Data were obtained from 161 countries and areas, covering 90% of the global population of women and girls (15 years or older). Globally, 27% (uncertainty interval [UI] 23–31%) of ever-partnered women aged 15–49 years are estimated to have experienced physical or sexual, or both, intimate partner violence in their lifetime, with 13% (10–16%) experiencing it in the past year before they were surveyed. This violence starts early, affecting adolescent girls and young women, with 24% (UI 21–28%) of women aged 15–19 years and 26% (23–30%) of women aged 19–24 years having already experienced this violence at least once since the age of 15 years. Regional variations exist, with low-income countries reporting higher lifetime and, even more pronouncedly, higher past year prevalence compared with high-income countries.

Interpretation

These findings show that intimate partner violence against women was already highly prevalent across the globe before the COVID-19 pandemic. Governments are not on track to meet the SDG targets on the elimination of violence against women and girls, despite robust evidence that intimate partner violence can be prevented. There is an urgent need to invest in effective multisectoral interventions, strengthen the public health response to intimate partner violence, and ensure it is addressed in post-COVID-19 reconstruction efforts.

Funding

UK Department for International Development through the UN Women–WHO Joint Programme on Strengthening Violence against Women Data, and UNDP-UN Population Fund-UNICEF-WHO-World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development, and Research Training in Human Reproduction, a cosponsored programme executed by WHO.

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

In 2013, WHO published the first global and regional estimates on the prevalence of physical or sexual, or both, intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence, based on a systematic review and analyses of existing survey data up to 2010. This review had not been updated since, nor did it systematically search for unpublished reports. This study was based on 141 studies in 81 countries, conducted between 1990 and 2012, and captured through a systematic review and an additional analysis of 54 national datasets. The systematic review had no language restrictions and searched 26 databases using the same search terms on intimate partner violence, non-partner sexual violence, and study designs as the current study. All population-based studies including a prevalence estimate on intimate partner violence or non-partner sexual violence NPSV, or both, were included. Since then, and with the announcement of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) target 5.2 on the elimination of violence against women, there has been a substantial increase in population-based surveys and studies measuring intimate partner violence across the world, with several countries now having conducted multiple surveys.

Added value of this study

This paper presents the first internationally comparable global, regional, and country (or area) prevalence estimates on both lifetime and past year physical or sexual violence, or both, by male intimate partners against ever-partnered women aged 15–49 years within the SDG reporting period (2015–30). In addition to the comprehensive and systematic searches, consultations with countries led to the identification of additional relevant data. This search led to the inclusion of a total of 366 studies from 161 countries and areas.

Implications of all the available evidence

We found that, based on 2000–18 data, more than one in four (27%) ever-partnered women aged 15–49 years had experienced physical or sexual, or both, intimate partner violence since the age of 15 years. One in seven (13%) experienced this violence in the year preceding the survey. The findings support that violence against women by male intimate partners is a global public health concern affecting the lives of millions of women and their children worldwide. Progress in reducing violence has been slow and countries are not on track to meet the commitments outlined in the SDGs. Robust evidence shows that intimate partner violence is preventable and targeted investments are required to implement multilevel, multisectoral prevention interventions and to strengthen the health and other sectors' response to intimate partner violence.

Introduction

Intimate partner violence against women is a grave human rights violation and serious global public health concern.1 This violence refers to physically, sexually, and psychologically harmful behaviours in the context of marriage, cohabitation, or any other form of union, as well as emotional and economic abuse and controlling behaviours.2 Intimate partner violence can have major short-term and long-term physical and mental health effects, including injuries, depression, anxiety, unwanted pregnancies, and sexually transmitted infections among others, and can also lead to death.3, 4, 5 It is estimated that 38–50% of the murders of women are committed by intimate partners globally.6 Intimate partner violence also leads to substantial social and economic costs for governments, communities, and individuals.7 The COVID-19 pandemic and its associated control measures (ie, lockdowns, mobility restrictions, and curfews) are further exacerbating the already heavy burden of intimate partner violence.8, 9

The 2030 UN Agenda for Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), adopted by member countries in 2015, calls for the elimination of violence against women and girls—namely through target 5.2 under goal 5 on gender equality and women's empowerment.10 The first indicator of this target (5.2.1) specifically focuses on intimate partner violence, requiring countries to regularly report on “the proportion of ever-partnered women and girls aged 15 years and older subjected to physical, sexual or psychological violence by a current or former intimate partner”.10 To understand the true magnitude of the problem and to monitor the progress made globally and by countries individually in addressing violence against women, it is crucial to establish a baseline for the global, regional, and national prevalence estimates of intimate partner violence. The regular collection, analyses, and reporting of robust comparable data is the first necessary step to develop targeted evidence-based, effective, and sustainable intersectoral interventions, policies, and programmes aimed at preventing violence against women. In the last decade, there has been a substantial increase in the number of nationally representative population-based surveys collecting data on intimate partner violence.3, 11 However, the measurement of intimate partner violence across surveys still shows notable variations in the quality of the surveys and types of measures used; for example, the definitions and items used to measure physical, sexual, psychological and other forms of intimate partner violence; women sampled (eg, ever-partnered, currently partnered only, or all women); age groups; and whether current or previous partners are included, making comparability across studies and countries challenging.11 Rigorous statistics and estimates on intimate partner violence that adjust for these variations are key to improving understanding of its prevalence, nature, and effect, and how these differ across age groups, countries, and regions.

The objective of this study is to provide baseline reliable and internationally comparable global, regional, and national prevalence estimates of lifetime and past year physical or sexual, or both, intimate partner violence by male partners against ever-partnered women, based on an analysis of data from population-based studies and surveys conducted between 2000 and 2018.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

This study modelled estimates on the basis of a comprehensive and systematic review and meta-analysis of population-based prevalence. Data for calculating global, regional, and national prevalence estimates of intimate partner violence were extracted to the WHO Global Database on Prevalence of Violence Against Women using a three-pronged approach. Firstly, a systematic review was conducted to replicate and extend the systematic reviews of the 2010 prevalence estimates on intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence published in 2013.3, 12, 13 For this systematic review, we searched MEDLINE, Global Health, Embase, Social Policy, and Web of Science, using the search terms “domestic violence” or “partner violence” or “spouse abuse” or “spouse violence” or “domestic abuse” or “partner abuse” or “battered women” or “intimate partner violence” or “domestic abuse” or “dating violence” or “sexual violence” or “sexual abuse” or “rape” combined with the study design terms (randomised controlled trials, meta-analyses, review, epidemiological, cohort, case control, longitudinal, retrospective, or cross-sectional). Secondly, we conducted manual searches of all Demographic and Health Surveys and other survey reports, and searched webpages of government statistical or other, or both, offices of each individual country for which publicly accessible studies or surveys could not be identified to also include unpublished reports that met our inclusion criteria (for details of inclusion criteria, search terms, and strategies; see Stöckl and colleagues13). Studies were included if they were conducted between 2000 and 2018, representative at the national or sub-national level, included women aged 15 years or older, and used act-based measures of intimate partner violence (table 1). The exclusion criteria comprised non-population-based data, including administrative data (eg, police or health statistics), studies not generalisable to the whole population, studies with outcomes that only provided the combined prevalence of physical or sexual, or both, intimate partner violence with other forms of violence, and studies with insufficient data to allow extrapolation or imputation.

Table 1.

Operational definitions of physical and sexual intimate partner violence and indicators most frequently used in the surveys included in this analysis

| Definition | |

|---|---|

| Intimate partner* violence | A woman's self-reported experience of being subjected to one or more acts of physical or sexual violence, or both, by a current or former husband or male intimate partner since the age of 15 years† |

| Physical intimate partner violence | Physical intimate partner violence‡ is operationalised as acts that can physically hurt the victim, including, but not limited to: being slapped or having something thrown at you that could hurt you; being pushed or shoved; being hit with a fist or something else that could hurt; being kicked, dragged, or beaten up; being choked or burnt on purpose; or being threatened with or actually having a gun, knife, or other weapon used on you; or a combination of these acts |

| Sexual intimate partner violence | Sexual intimate partner violence§ is operationalised as: being physically forced to have sexual intercourse when you do not want to; having sexual intercourse out of fear for what your partner might do or through coercion; or being forced to do something sexual that you consider humiliating or degrading; or a combination of these acts |

| Lifetime prevalence¶ of intimate partner violence | The proportion of ever-married or ever-partnered women who reported that they had been subjected to one or more acts of physical or sexual violence, or both, by a current or former husband or male intimate partner in their lifetime (defined as since the age of 15 years) |

| Past year prevalence¶ of intimate partner violence (also referred to as recent or current intimate partner violence) | The proportion of ever-married or ever-partnered women who reported that they had been subjected to one or more acts of physical or sexual violence, or both, by a current or former husband or male intimate partner within the 12 months preceding the survey |

The definition of intimate partner varies between settings and includes formal partnerships, such as marriage, as well as informal partnerships, such as cohabitating or other regular intimate partnerships. It was necessary that the denominator was inclusive of all women who could be exposed to intimate partner violence, so for the purposes of this analysis we accepted whatever definitions of partner were used in the surveys and studies that were included in this analysis, which includes current and former husbands, and current and former cohabitating and non-cohabitating male intimate partners.

The age of 15 years is set as the lower age in the range for the purposes of these estimates. Most surveys, including the Demographic and Health Surveys and specialised surveys on violence against women, include girls and women aged 15 years and older in the measure of intimate partner violence to capture the experiences of girls and women in settings where marriage commonly occurs among girls from the age of 15 years.

The Domestic Violence Module of the Demographic and Health Surveys, the WHO multi-country study on Women's Health and Domestic Violence against Women, and other specialised surveys on violence against women that use the WHO multi-country study survey instrument and its adaptations, draw on adapted versions of the Conflicts Tactics Scale to measure the prevalence of physical partner violence.

As operationalised in the Domestic Violence Module of the Demographic and Health Surveys, the WHO multi-country study on Women's Health and Domestic Violence against Women, and other specialised surveys on violence against women that use the WHO multi-country study survey instrument.

Prevalence refers to the number of women who have been subjected to partner violence divided by the number of at-risk women in the study population.

Finally, in line with WHO's quality standards for data publication, a country consultation on the intimate partner violence estimates was conducted between December, 2019, and May, 2020, with 194 WHO member states and one territory. This consultation ensured that countries had the opportunity to review the methods used to generate the estimates, their national modelled intimate partner violence estimates, and the survey data sources used to produce them. During this process, 32 additional studies were identified or provided, or both, by national statistics offices. These studies were reviewed, and the relevant data included from studies that met the inclusion criteria. These survey reports, documentation, and data were all national-level surveys and hence data was provided by national statistical offices or relevant ministries and organisations, or both, implementing the surveys. Where published reports were not available, all information needed to review the eligibility of the study and covariates was sought from the survey implementation body, namely the author.

Data extractions were conducted by two data analysts (LS and SRM or HS) independently and underwent quality control and rigorous consistency checks by a third reviewer (MM-G). Any conflicts on the inclusion of a paper were discussed with CG-M and where relevant, the Technical Advisory Group with final decisions on inclusion or exclusion of papers made by CG-M. The study protocol is available online.

Data analysis

We developed a statistical framework to produce age-specific and country-specific estimates of intimate partner violence. For the variables for which data were extracted, see the online study protocol. The data pre-processing steps, model structure, statistical analyses (including model validation), and post-processing of estimates have been described elsewhere in detail to allow analyses to be reproduced.11 Briefly, at the pre-processing stages we selected from each survey in the database the age-disaggregated estimates that corresponded to the so-called optimal set of observations. That is, observations for which the case definition encompasses all violent acts (and not only severe acts of violence), refers to physical or sexual violence, or both, where the denominator included all ever-partnered or married women, and for which the male perpetrator was any current or previous intimate male partner(s) or husband(s). If the survey did not report estimates corresponding to that definition, we included the available next best set of observations but a statistical adjustment was applied (see later).

We used a Bayesian hierarchical model to pool and adjust data.14, 15 Any duplicate data identified during consistency checks were reviewed and cross-checked with the original survey or study by the data analyst (LS) and only the most complete record was retained. Our meta-regression framework11 has five nested levels: (1) individual studies, (2) countries, (3) regions, (4) super-regions, and (5) the world. Regions were defined based on the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study classification5 that groups countries into 21 mutually exclusive regions and seven super regions, based on their epidemiological profiles. The structure of this Bayesian logistic regression model has the following features. First, both national and sub-national population-based studies can be included, but sub-national observations are modelled as having more variability (that is, less weight as established by the data). Second, an age standardising approach allows for heterogeneous age groups (eg, a study with 5-year age groups versus a study that includes women aged 15 years or older) to be included in the model. This age standardisation is applied to all observations for which the age interval was longer than 5 years, and the 2010 region-specific female age distribution was used as the standard (obtained from the World Population Prospects 2019 revision). Third, non-linear relationships between intimate partner violence and both age and calendar time are modelled using natural cubic splines (two knots for age, one knot for time); each country has its own age pattern and time trend but those are nested within regions, super-regions, and the world.11 Fourth, approximately 50% of observations did not belong to the so-called optimal set of observations and the model applied statistical adjustments. Adjustment factors were estimated outside of the main model using exact matching to avoid compositional biases. These include adjustments for estimates that referred to: severe violence only, physical violence only, sexual violence only, all women surveyed, only currently partnered women surveyed, perpetrating partner is only current or more recent, and geographical strata (urban and rural). Region-specific adjustment factors, pooled using meta-analytical approaches,11 were used if a region had more than three estimates; otherwise, the overall adjustment factor was chosen to adjust observations. Finally, by definition, all model-based estimates of past year intimate partner violence should be lower than those of lifetime prevalence. This fact was enforced by jointly modelling the prevalence of both timeframes and constraining past year prevalence to be lower than that estimated for lifetime prevalence.

The posterior distribution of the model variables were estimated using Markov chain Monte Carlo simulations in JAGS software version 4.6. Model validation was performed using posterior predictive checks and both in-sample and out-of-sample comparisons that examined median errors, median absolute errors, and coverage of uncertainty intervals (UIs).11 Survey data and model fits for each country are presented in the appendix (pp 1–2). To obtain aggregate estimates (ie, by age, country, or region), we used population denominators for the 2018 calendar year from the World Population Prospects (2019 revision). Because the appropriate denominators should be composed of ever-partnered women, we used the 2018 country-specific and age-specific proportion of women who ever had sex (an objective proxy of partnership formation).

We followed the Guidelines for Accurate and Trans-parent Health Estimates Reporting16 statement in develop-ing the database, analysis, and presentation of the study (appendix pp 11–12). All analyses were done using STATA 16 and R version 4.0.4 statistical software. The model's source code has been made publicly available online. This study is registered with PROSPERO (number CRD42017054100).

Role of the funding source

The funders of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Results

The WHO Global Database contains 359 studies with information on lifetime intimate partner violence. For this analysis, two studies were excluded because they contained information on psychological violence only, 23 studies were excluded because they did not use act-specific questions, and 27 studies were excluded because they were outside of the study period (2000–18). A total of 307 studies were analysed for the lifetime intimate partner violence prevalence.

The Global Database contains 392 studies with infor-mation on past year intimate partner violence. Two studies were excluded because they contained information on psychological violence only, 29 studies were excluded because they did not use act-specific questions, and 29 studies were excluded because they were outside of our study period (2000–18). A total of 332 studies were analysed.

There were 307 unique studies conducted between 2000 and 2018, from 154 countries and areas, totalling 1 767 802 unique women responses, that were included to estimate the lifetime prevalence of physical or sexual, or both, intimate partner violence against women aged 15 years and older. The estimates for violence that occurred within the past year were informed by 332 studies from 159 countries and areas and 1 763 989 individual responses. In total, 366 unique studies from 161 countries and areas with data on lifetime or past year, or both, intimate partner violence underpin these estimates. For both time periods, these studies were representative of 90% of the world's population of ever-partnered women and girls aged 15 years and older.11 The results for the regional analyses by SDG and WHO regions are available in the appendix (pp 3–5). The study characteristics are displayed in table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of included studies on lifetime and past year intimate partner violence conducted between 2000 and 2018

| Lifetime intimate partner violence | Past year intimate partner violence | |

|---|---|---|

| Sample characteristics and representativeness | ||

| Number of women interviewed* | 1 767 802 | 1 763 989 |

| Number of age-specific observations | 1551 | 1598 |

| Number of studies | 307 | 332 |

| Nationally representative studies | 260/307 (85%) | 292/332 (88%) |

| Number of countries† represented | 154 | 159 |

| Countries with one study | 77/154 (50%) | 81/159 (51%) |

| Countries with two studies | 41/154 (27%) | 33/159 (21%) |

| Countries with three studies | 16/154 (10%) | 19/159 (12%) |

| Countries with four or more studies | 20/154 (13%) | 26/159 (16%) |

| Number of Global Burden of Disease regions represented | 21/21 (100%) | 21/21 (100%) |

| Median date of data collection | 2011·5 | 2011·5 |

| Studies conducted 2000–04 | 53/307 (17%) | 65/332 (20%) |

| Studies conducted 2005–09 | 67/307 (22%) | 67/332 (20%) |

| Studies conducted 2010–14 | 115/307 (37%) | 119/332 (36%) |

| Studies conducted 2015–18 | 72/307 (23%) | 81/332 (24%) |

| Country-years of observations | 302 | 323 |

| Studies requiring adjustments | ||

| Violence definition: severe violence only‡ | 4/307 (1%) | 5/332 (2%) |

| Intimate partner violence type: sexual violence only | 5/307 (2%) | 0/332 |

| Intimate partner violence type: physical violence only | 63/307 (21%) | 84/332 (25%) |

| Population surveyed: all women | 19/307 (6%) | 28/332 (8%) |

| Population surveyed: currently partnered | 26/307 (8%) | 39/332 (12%) |

| Reference partners: current or most recent | 116/307 (38%) | 80/332 (24%) |

| Geographical strata: rural only | 14/307 (5%) | 12/332 (4%) |

| Geographical strata: urban only | 18/307 (6%) | 13/332 (4%) |

| Observations not requiring adjustments | 635/1551 (41%) | 857/1598 (54%) |

Data presented as n or n/N (%).

Number of women interviewed imputed for surveys with missing denominators.

These data include 151 countries for lifetime intimate partner violence and 156 countries for past year intimate partner violence, plus three areas each. In total, these data include 161 countries and areas and 366 studies on lifetime or past year, or both, intimate partner violence.

The definition of severe violence corresponds to the one reported in the survey description.

Globally, 27% (UI 23–31%) of ever-partnered women aged 15–49 years are estimated to have experienced physical or sexual, or both, intimate partner violence at least once in their lifetime (table 3). Among ever-partnered women aged 15 years and older, 26% (22–30%) are estimated to have experienced intimate partner violence at least once in their lifetime.

Table 3.

Global prevalence estimates of lifetime and past year physical or sexual, or both, intimate partner violence among ever-married or ever-partnered women, by age group, in 2018

| Lifetime intimate partner violence prevalence estimate | Past year intimate partner violence prevalence estimate | |

|---|---|---|

| 15–49 years | 27% (23–31%) | 13% (10–16%) |

| 15 years and older | 26% (22–30%) | 10% (8–12%) |

| 15–19 years | 24% (21–28%) | 16% (14–19%) |

| 20–24 years | 26% (23–30%) | 16% (13–19%) |

| 25–29 years | 27% (23–32%) | 15% (12–18%) |

| 30–34 years | 28% (24–33%) | 13% (11–17%) |

| 35–39 years | 28% (24–33%) | 12% (10–15%) |

| 40–44 years | 27% (23–32%) | 10% (8–13%) |

| 45–49 years | 26% (22–31%) | 8% (6–11%) |

| 50–54 years | 25% (21–30%) | 7% (5–9%) |

| 55–59 years | 24% (20–30%) | 6% (5–8%) |

| 60–64 years | 23% (19–31%) | 5% (4–7%) |

| 65 years and older | 23% (18–30%) | 4% (3–7%) |

Data presented as % (uncertainty interval %).

Globally, it is estimated that 13% (UI 10–16%) of ever-partnered women aged 15–49 years have experienced physical or sexual violence, or both, from an intimate male partner within the year preceding the survey interview. This estimate is 10% (8–12%) for women aged 15 years and older.

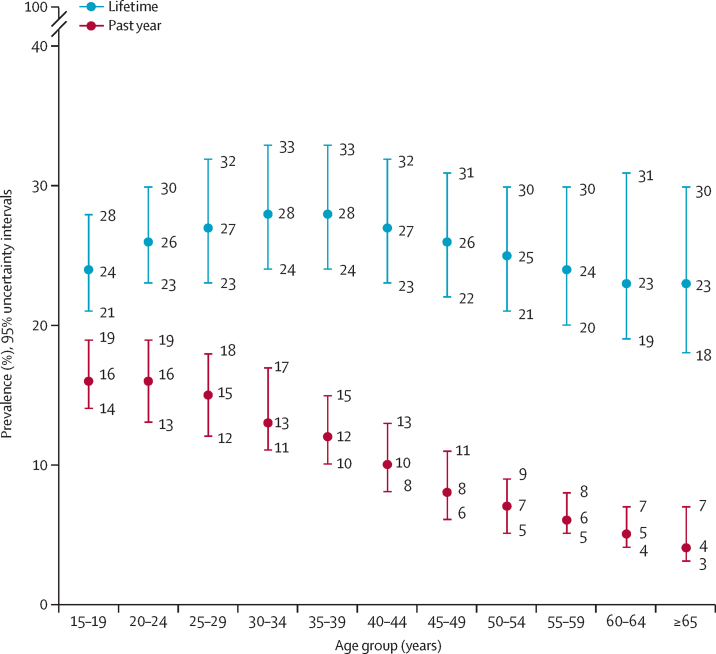

The age disaggregated prevalence of physical or sexual, or both, intimate partner violence shows that such violence is already highly prevalent in the youngest age cohort (table 3, figure 1). Almost one in four ever-partnered adolescent girls between the ages of 15 and 19 are estimated to have experienced physical or sexual violence, or both, from an intimate partner since age 15 (24%; UI 21–28%). The estimated lifetime prevalence of intimate partner violence is high at 26–28% for women between the ages of 20 and 44 years and is comparatively lower among women older than 60 years, at 23% (19–31%) for those aged 60–64 years and 23% (18–30%) for those aged 65 years and older. The prevalence estimates among the older age groups need to be interpreted with caution given their overlapping UIs. As with lifetime prevalence, physical or sexual, or both, intimate partner violence in the past year was highest among the youngest age cohorts: 16% (UI 14–19%) among those aged 15–19 years and 16% (13–19%) among those aged 20–24 years. The estimated prevalence of this type of violence within the past year was substantially lower among ever-partnered women aged 50 years and older, and was lowest among women aged 60–64 years (5%; 4–7%) and those aged 65 years and older (4%; 3–7%).

Figure 1.

Global prevalence estimates of lifetime and past year physical or sexual, or both, intimate partner violence among ever-married or ever-partnered women, by age group, in 2018

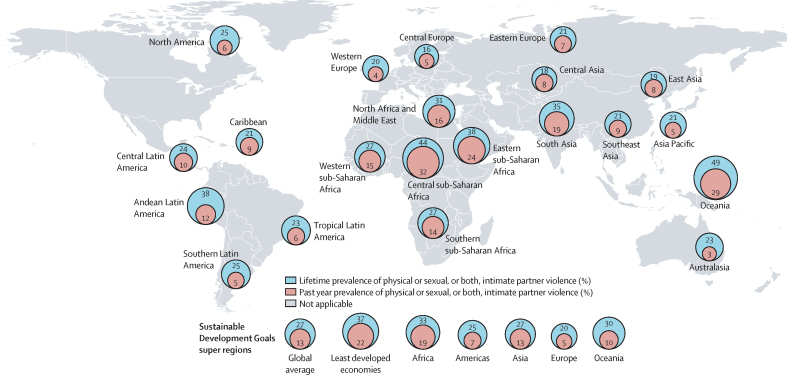

Regional variations by the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study classifications showed that the estimated lifetime prevalence of physical or sexual, or both, intimate partner violence among ever-partnered women aged 15–49 years (the age range for which there is the most data on intimate partner violence) was the highest in Oceania (49%; UI 38–61%) and central sub-Saharan Africa (44%; 33–55%), followed by Andean Latin America (38%; 31–46%) and eastern sub-Saharan Africa (38%; 31–44%; table 4). The prevalence of lifetime physical or sexual, or both, intimate partner violence was also high, and more than the global average, in south Asia (35%; 26–46%) and north Africa and the Middle East (31%; 24–40%).

Table 4.

Regional prevalence estimates of lifetime and past year physical or sexual, or both, intimate partner violence among ever-married or ever-partnered women aged 15–49 years, by Global Burden of Disease region, in 2018

| Lifetime intimate partner violence prevalence estimate | Past year intimate partner violence prevalence estimate | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Central Europe, eastern Europe and central Asia | |||

| Central Asia | 18% (13–24%) | 8% (6–12%) | |

| Central Europe | 16% (12–21%) | 5% (3–6%) | |

| Eastern Europe | 21% (15–29%) | 7% (5–11%) | |

| High income | |||

| Asia Pacific | 21% (12–35%) | 5% (3–10%) | |

| Australasia | 23% (16–32%) | 3% (2–5%) | |

| Western Europe | 20% (15–26%) | 4% (3–6%) | |

| Southern Latin America | 25% (17–35%) | 5% (3–8%) | |

| North America | 25% (14–41%) | 6% (4–9%) | |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | |||

| Caribbean | 21% (17–26%) | 9% (7–12%) | |

| Andean Latin America | 38% (31–46%) | 12% (9–15%) | |

| Central Latin America | 24% (19–31%) | 10% (7–14%) | |

| Tropical Latin America | 23% (15–34%) | 6% (4–10%) | |

| North Africa and the Middle East | 31% (24–40%) | 16% (12–22%) | |

| South Asia | 35% (26–46%) | 19% (12–27%) | |

| Southeast Asia, east Asia and Oceania | |||

| East Asia | 19% (11–32%) | 8% (3–17%) | |

| Southeast Asia | 21% (15–31%) | 9% (6–14%) | |

| Oceania | 49% (38–61%) | 29% (19–40%) | |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | |||

| Central sub-Saharan Africa | 44% (33–55%) | 32% (22–43%) | |

| Eastern sub-Saharan Africa | 38% (31–44%) | 24% (19–29%) | |

| Southern sub-Saharan Africa | 27% (19–37%) | 14% (9–22%) | |

| Western sub-Saharan Africa | 27% (22–33%) | 15% (12–19%) | |

| World | 27% (23–31%) | 13% (10–16%) | |

Data presented as % (UI%). Country estimates are presented in the appendix (pp 6–10). UI=uncertainty interval.

The three regions with lowest lifetime intimate partner violence prevalence estimates were central Europe (16%; UI 12–21%), central Asia (18%; 13–24%), and western Europe (20%; 15–26%), although even these rates are still high.

As with the lifetime prevalence of intimate partner violence, the highest prevalence of past year physical or sexual, or both, intimate partner violence among ever-partnered women aged 15–49 years was in the regions of central sub-Saharan Africa (32%; UI 22–43%) and Oceania (29%; 19–40%), followed by eastern sub-Saharan Africa (24%; 19–29%) and south Asia (19%; 12–27%; table 4).

Overall, mostly high-income countries including Australasia (3%; UI 2–5%), western Europe (4%; 3–6%), central Europe (5%; 3–6%), southern Latin America (5%; 3–8%), and North America (6%; 4–9%) had the lowest estimated prevalence rates of past year physical or sexual, or both, intimate partner violence among women aged 15–49 years.

Differences in the prevalence of intimate partner violence between the largely higher-income regions and low-income and middle-income regions were much more pronounced for prevalence in the past year compared with lifetime prevalence (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Map of 2018 lifetime versus past year prevalence of physical or sexual, or both, intimate partner violence among ever-partnered women aged 15–49 years by Global Burden of Disease region and Sustainable Development Goals super region

The appendix (pp 6–10) provides the 2018 prevalence estimates and 95% UIs for lifetime and past year physical or sexual, or both, intimate partner violence among ever-partnered women aged 15–49 years, for every country and area that had at least one available data source that met the inclusion criteria for this analysis.

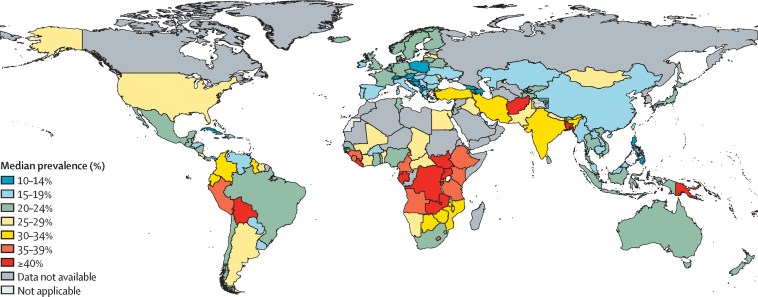

There was a wide variation in prevalence across countries (figure 3). The median prevalence estimates of lifetime physical or sexual, or both, intimate partner violence among ever-partnered women aged 15–49 years was highest in 19 countries (Kiribati [53%], Fiji [52%], Papua New Guinea [51%], Bangladesh and Solomon Islands [both 50%], Democratic Republic of the Congo and Vanuatu [both 47%], Afghanistan and Equatorial Guinea [both 46%], Uganda [45%], Liberia and Nauru [both 43%], Bolivia [42%], Gabon, South Sudan, and Zambia [all 41%], Burundi, Lesotho, and Samoa [all 40%]). The median estimates of these countries ranged from 53% (UI 35–70%) in Kiribati, 50% (37–62%) in Bangladesh, and 50% (33–67%) in the Solomon Islands, to 40% (27–55%) in Burundi, 40% (21–62%) in Lesotho, and 40% (25–57%) in Samoa. All except two of these 19 countries are in Oceania (excluding Australia and New Zealand), sub-Saharan Africa, or south Asia regions. A further 16 countries (Cameroon and Tuvalu [both 39%], Angola, Kenya, Marshall Islands, Peru, Rwanda, Timor-Leste, and Tanzania [all 38%], Ethiopia, Guinea, and Tonga [all 37%], Sierra Leone [36%], and India, Federated States of Micronesia, and Zimbabwe [all 35%]), mainly from sub-Saharan Africa and south Asia, had the second highest prevalence ranges, with 35–39% of ever-married or ever-partnered women aged 15–49 years having been subjected to physical or sexual, or both, violence from an intimate partner at least once in their lifetime.

Figure 3.

Map of prevalence estimates of lifetime physical or sexual, or both, intimate partner violence among ever-partnered women aged 15–49 years, in 2018

The group with the lowest prevalence estimates for lifetime physical or sexual violence, or both (ranging from 10 to 14%), includes 12 countries (Georgia and Armenia [both 10%], Singapore [11%], Switzerland and Bosnia and Herzegovina [both 12%], Albania, Poland, North Macedonia, and Croatia [all 13%], and Cuba, Azerbaijan, and the Philippines [all 14%]). Of the 12 countries, six were in subregions of Europe, with a prevalence between 12 and 13%, and three were countries in western Asia, with prevalence estimates for lifetime physical or sexual violence, or both, of: 10% (UI 6–17%) in Armenia, 10% (6–18%) in Georgia, and 14% (8–22%) in Azerbaijan. The other three countries were: Singapore with 11% (5–22%), Cuba with 14% (8–23%), and the Philippines with 14% (10–21). Four additional countries from Europe and one from central Asia had prevalence between 15 and 16%.

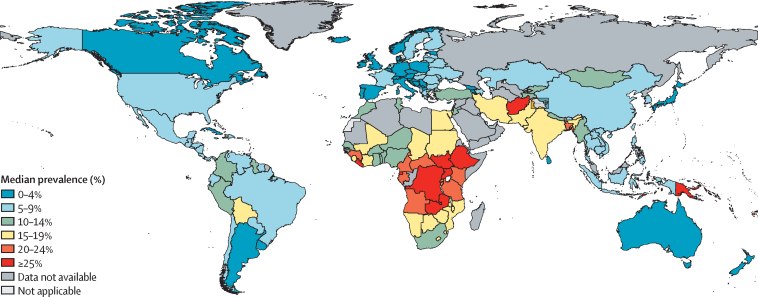

Figure 4 presents a map with the country-level past year prevalence of physical or sexual, or both, intimate partner violence among ever-partnered women aged 15–49 years. The 14 countries with the highest prevalence estimates of intimate partner violence in the past year (ranging from 25–36%) were Democratic Republic of the Congo (36%; UI 23–50%), Afghanistan (35%; 22–50%), Papua New Guinea (31%; 19–45%), Vanuatu (29%; 16–48%), Equatorial Guinea (29%; 16–46%), Solomon Islands (28%; 15–46%), Timor-Leste (28%; 19–40%), Zambia (28%; 19–39%), Ethiopia (27%; 17–38%), Liberia (27%; 17–40%), South Sudan (27%; 13–48%), Uganda (26%; 18–36%), Angola (25%; 14–39%), and Kiribati (25%; 14–42%). There were 14 additional countries (Tanzania [24%], Bangladesh, Fiji, Kenya, and Rwanda [all 23%], Burundi, Cameroon, and Gabon [all 22%], Central African Republic, Guinea, and Federated States of Micronesia [21%], and Nauru, Sierra Leone, and Tuvalu [20%]) that had prevalence rates between 20 and 24%, mainly from the sub-Saharan African and Oceania regions.

Figure 4.

Map of prevalence estimates of past year physical or sexual, or both, intimate partner violence among ever-partnered women aged 15–49 years, in 2018

Of the 30 countries with the lowest prevalence estimates for past year physical or sexual violence, or both (up to 4%), 24 were high-income countries. 23 of the 30 countries within this lowest prevalence range were in Europe. The other seven were Australia, Canada, Japan, New Zealand, Singapore, Sri Lanka, and Uruguay.

Discussion

Our study confirms that, concerningly, physical or sexual violence, or both, against women by male intimate partners is highly prevalent globally. Overall, we found that more than one in four (27%) ever-partnered women aged 15–49 years had experienced physical or sexual violence, or both, from a current or former intimate partner at least once in their lifetime; and one in seven (13%) had experienced it in the past year. This finding means that in 2018, up to 492 million ever-partnered women aged 15–49 years had been subjected to this type of violence by an intimate partner at least once since the age of 15 years.

This study also draws attention to the high amount of recent or current intimate partner violence experienced by young women, with one in six women (16%) aged 15–24 years estimated to have been subjected to physical or sexual, or both, intimate partner violence within the year preceding the survey. This finding is concerning because adolescence and early adulthood are important life stages in which the foundations for healthy relationships are built; this violence has long-lasting effects on women's health and overall wellbeing.17

We found that the lifetime and past year prevalence of physical or sexual, or both, intimate partner violence varied widely across regions and countries, with higher prevalence rates of both types in low-income and middle-income countries and regions than high-income countries. These differences between higher-income and lower-income regions were notably more pronounced with past year prevalence than lifetime prevalence, and the relative differences between lifetime and past year prevalence were smaller in low-income and middle-income countries and regions. It is important to note that there are 28 countries with past year physical or sexual, or both, intimate partner violence prevalence that is substantially higher than the global average. Several of these are countries affected by conflict. These findings are consistent with the different social, economic, and political circumstances that are associated with intimate partner violence and limit women's ability to leave abusive relationships, such as economic insecurity, gender inequitable norms, high amounts of societal stigma, economic insecurity, discriminatory family law, and inadequate support services.18, 19

The limitations of these analyses first include the reliance on the availability and quality of existing violence against women survey data and measures. The modelled estimates and UIs presented in this Article are the most accurate that could be derived from the available 2000–18 prevalence data from 161 countries and areas on intimate partner violence. However, although there has been an increase in the number of national population-based surveys with such data, there are gaps in the availability of data in some geographical regions, and not all surveys are recent or use gold standard measures.1

Second, all estimates in this study are based on women's self-reported experiences of being subjected to intimate partner violence. Given the sensitive nature of the issue, the true prevalence of physical or sexual, or both, intimate partner violence is likely to be higher. Survey design and implementation, including interviewer training, play an important role in enabling disclosure and affect survey results.20

Third, the definition of a partnership is variable across contexts, and we relied on the survey's definition of a partnership. However, some studies might not have captured all partnership types and this could have affected our estimates, especially among adolescent and younger women.

Fourth, our estimates for women aged 60 years and older are limited by the relative paucity of empirical observations. Because most data, especially for low-income and middle-income countries, came from demographic and health surveys, data availability is skewed towards women of reproductive age in the 15–49 year range. Although this group of women might be at a higher risk of intimate partner violence, there is a need for more and better quality data to optimally capture the violence experienced by older women21 and across the life course.

And finally, psychological intimate partner violence has substantial negative effects on women. However, this type of violence could not be included in the current estimation process because of the challenges that exist with variations in definitions, measurement, and non-standardisation across surveys and countries.22 Work by WHO is underway to address these challenges and overcome this limitation.

We need to continue strengthening, standardising, and building capacity for the collection, reporting, and use of data on violence against women to support countries' efforts and to monitor progress at national, regional, and global levels. We recommend that governments invest in dedicated surveys on violence against women or comprehensive modules with specially trained interviewers and adherence to ethical and safety standards to better estimate the magnitude of violence against women. These improved estimates are crucial to the development of effective prevention policies and programmes. There is a need to develop robust survey measures to better understand violence experienced by women living with multiple forms of discrimination, for example those living with disabilities, indigenous and minority ethnic or migrant women, transgender women, and women in same-sex partnerships, for which there are currently few data.23

Despite the limitations in available data, this study unequivocally establishes the persistently high prevalence of intimate partner violence. Notably, intimate partner violence is preventable. There has been a substantial increase in the body of knowledge on what works to prevent violence against women and girls in the last decade.24 The RESPECT women framework for prevention summarises much of this evidence.25 This framework, endorsed by 14 agencies and funders, organises evidence-based interventions for the prevention of violence against women through seven strategies. Several high-level initiatives, such as the Action Coalition on Gender-based violence of the Generation Equality Forum, are advocating for and investing in countries to do more when it comes to evidence-based prevention, including developing community-based and school-based interventions that promote gender equality and challenge gender stereotypes and discriminatory norms, reforming discriminatory laws, and ensuring women's access to formal wage employment and secondary and higher education. Other programmes showing promise with regards to violence prevention focus on transforming attitudes that justify violence against women and promoting more equitable relationships within the family, reducing exposure to violence during childhood and reducing child abuse, and increasing access to cash transfers, particularly women's access to cash transfers.25 More research is needed to identify effective prevention interventions and bring them to scale.24 At the same time, services are needed for the millions of women already living with violence.26

Although progress has been made in implementing such programmes, this progress is grossly insufficient to meet the SDG target of eliminating violence against women by 2030. This problem is likely to have been further exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic that has caused an unprecedented setback in efforts towards the reduction of violence against women.8 Although these estimates are based on pre-COVID-19 survey data, helpline, police, and other service data suggest that the pandemic and its associated lockdowns might have led to further increases in intimate partner violence.8 The full effect of the COVID-19 pandemic will only be known when population-based surveys are able to fully resume. The need to scale up existing interventions and the preparedness of health and other sectors to ensure women's access to services centered around people who have experienced intimate partner violence and referrals is even more pressing.

Intimate partner violence affects the lives of millions of women, children, families, and societies worldwide. These data clearly show that this violence predates the COVID-19 pandemic and will probably continue long after. Preventing intimate partner violence from happening in the first place is necessary and urgent. Governments, societies, and communities need to take heed, invest more, and act with urgency to reduce violence against women, including by addressing it in post-COVID-19 reconstruction efforts.

For R Project for Statistical Computing see https://www.r-project.org/

For the model source code see https://github.com/pop-health-mod/vawstats-release”

For the protocol see https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/11/8/e045574.long

For the World Population Prospects 2019 revision see https://population.un.org/wpp/

For JAGS software see http://mcmc-jags.sourceforge.net/

Data sharing

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declaration of interests

CG-M is a staff member of the UNDP-UN Population Fund-UNICEF-WHO-World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development, and Research Training in Human Reproduction in the Department of Sexual and Reproductive Health and Research that is executed by WHO. SRM is a consultant in the Department of Sexual and Reproductive Health and Research, outside of the submitted work. LS is a staff member of the UNDP-UN Population Fund-UNICEF-WHO-World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development, and Research Training in Human Reproduction in the Department of Sexual and Reproductive Health and Research that is executed by WHO. MM-G's research programme is funded by a Tier II Canada Research Chair in Population Health Modelling, outside of the submitted work. HS is funded by a European Research Council Starting Grant (716458) and the British Academy, outside of the submitted work. SRM declares no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

We thank the UN Inter-Agency Working Group on Violence Against Women Estimation and Data, and the independent external Technical Advisory Group to the UN Inter-Agency Working Group on Violence Against Women Estimation and Data for reviewing and guiding the process of developing the methods and the estimates. We thank WHO country and regional offices for facilitating the country consultations. We also thank all government technical focal people for the violence against women estimates and the Sustainable Development Goal focal points who reviewed the preliminary estimates on intimate partner violence against women and provided valuable feedback and input. We thank those who assisted with the data extraction and review at various stages of the database development. The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this Article and they do not necessarily represent the views, decisions, or policies of the McGill University, the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, Ludwig Maximilians Universität, or WHO. This work was funded by the UK Department for International Development (now Foreign Commonwealth and Development Office) and the UNDP-UN Population Fund-UNICEF-WHO-World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction, a cosponsored programme executed by WHO.

Editorial note: the Lancet Group takes a neutral position with respect to territorial claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributors

LS contributed to the study design, data extraction and curation, investigation, methods, validation, microdata analysis, visualisation, writing the original draft, and reviewing and editing the manuscript. MM-G contributed to the data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methods, validation, visualisation, and reviewing and editing the manuscript. HS contributed to the systematic review design and protocol, the study design, data extraction and curation, investigation, methods, and reviewing and editing the manuscript. SRM contributed to the search strategy design and protocol, study design, data extraction, and curation, investigation, and reviewing the manuscript. CG-M conceptualised the study and contributed to the study design, funding acquisition, investigation, validation, methods, project administration, resources, supervision, and reviewing and editing the manuscript. CG-M had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Devries KM, Mak JY, García-Moreno C, et al. Global health. The global prevalence of intimate partner violence against women. Science. 2013;340:1527–1528. doi: 10.1126/science.1240937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krug EG, Mercy JA, Dahlberg LL, Zwi AB. The world report on violence and health. Lancet. 2002;360:1083–1088. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11133-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.García-Moreno C, Pallitto C, Devries K, Stöckl H, Watts C, Abrahams N. Global and regional estimates of violence against women: prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. 2013. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/85239/9789241564625_eng.pdf

- 4.Bacchus LJ, Ranganathan M, Watts C, Devries K. Recent intimate partner violence against women and health: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMJ Open. 2018;8 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vos T, Barber RM, Bell B, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2015;386:743–800. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60692-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stöckl H, Devries K, Rotstein A, et al. The global prevalence of intimate partner homicide: a systematic review. Lancet. 2013;382:859–865. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61030-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walby S. The cost of domestic violence: up-date 2009. Feb 26, 2019. https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/21695/

- 8.Roesch E, Amin A, Gupta J, García-Moreno C. Violence against women during COVID-19 pandemic restrictions. BMJ. 2020;369 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamadani JD, Hasan MI, Baldi AJ, et al. Immediate impact of stay-at-home orders to control COVID-19 transmission on socioeconomic conditions, food insecurity, mental health, and intimate partner violence in Bangladeshi women and their families: an interrupted time series. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8:e1380–e1389. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30366-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.UN Goal 5: achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls. https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal5

- 11.Maheu-Giroux M, Sardinha L, Stöckl H, et al. A framework to model global, regional, and national estimates of intimate partner violence. medRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2020.11.19.20235101. published online March 2. (preprint). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abrahams N, Devries K, Watts C, et al. Worldwide prevalence of non-partner sexual violence: a systematic review. Lancet. 2014;383:1648–1654. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62243-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stöckl H, Sardinha L, Maheu-Giroux M, Meyer SR, García-Moreno C. Physical, sexual and psychological intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence against women and girls: a systematic review protocol for producing global, regional and country estimates. BMJ Open. 2021;11 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-045574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finucane MM, Paciorek CJ, Danaei G, Ezzati M. Bayesian estimation of population-level trends in measures of health status. Stat Sci. 2014;29:18–25. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flaxman AD, Vos T, Murray CJL. University of Washington Press; Seattle: 2015. An integrative metaregression framework for descriptive epidemiology. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stevens GA, Alkema L, Black RE, et al. Guidelines for Accurate and Transparent Health Estimates Reporting: the GATHER statement. PLoS Med. 2016;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stöckl H, March L, Pallitto C, Garcia-Moreno C. Intimate partner violence among adolescents and young women: prevalence and associated factors in nine countries: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:751. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heise L, Fulu E. What works to prevent violence against women and girls evidence reviews. Paper 1: state of the field of violence against women and girls. 2015. https://www.whatworks.co.za/documents/publications/16-global-evidence-reviews-paper-1-state-of-the-field-of-research-on-violence-against-women-and-girls/file

- 19.Sardinha L, Nájera Catalán HE. Attitudes towards domestic violence in 49 low- and middle-income countries: a gendered analysis of prevalence and country-level correlates. PLoS One. 2018;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0206101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.WHO Putting women first: ethical and safety recommendations for research on domestic violence against women. 2001. https://www.who.int/gender/violence/womenfirtseng.pdf

- 21.Meyer SR, Lasater ME, García-Moreno C. Violence against older women: a systematic review of qualitative literature. PLoS One. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0239560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jewkes R. Emotional abuse: a neglected dimension of partner violence. Lancet. 2010;376:851. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61079-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.García-Moreno C, Zimmerman C, Morris-Gehring A, et al. Addressing violence against women: a call to action. Lancet. 2015;385:1685–1695. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61830-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jewkes R, Willan S, Heise L, et al. Effective design and implementation elements in interventions to prevent violence against women and girls. January, 2020. https://www.whatworks.co.za/documents/publications/373-intervention-report19-02-20/file [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.WHO RESPECT women: preventing violence against women. 2019. https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/preventing-vaw-framework-policymakers/en/

- 26.UN Women. UNFPA. WHO. UNDP. UNODC Essential services package for women and girls subject to violence. 2015. https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2015/12/essential-services-package-for-women-and-girls-subject-to-violence#view

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.