Abstract

Introduction:

Current treatment for Type 1 diabetes (T1D) is centered around insulin supplementation to manage the effects of pancreatic β cell loss. GDF15 is a potential preventative therapy against T1D progression that could work to curb increasing disease incidence.

Areas Covered:

This paper discusses the known actions of GDF15, a pleiotropic protein with metabolic, feeding, and immunomodulatory effects, connecting them to highlight the open opportunities for future research. The role of GDF15 in the prevention of insulitis and protection of pancreatic β cells against pro-inflammatory cytokine-mediated cellular stress are examined and the pharmacological promise of GDF15 and critical areas of future research are discussed.

Expert Opinion:

GDF15 shows promise as a potential intervention but requires further development. Preclinical studies have shown poor efficacy, but this result may be confounded by the measurement of gross GDF15 instead of the active form. Additionally, the effect of GDF15 in the induction of anorexia and nausea-like behavior and short-half-life present significant challenges to its deployment, but a systems pharmacology approach paired with chronotherapy may provide a possible solution to therapy for this currently unpreventable disease.

Keywords: GDF15, Type 1 diabetes (T1D), Type 2 diabetes (T2D), Insulitis, β cells stress, ER stress, immunomodulator & chronotherapy

1. Introduction –

Type 1 diabetes (T1D) is an autoimmune disorder marked by the destruction of insulin-producing β cells in the pancreas. The International Diabetes Federation (IDF) estimates T1D cases increase by 3% per year globally, with the 2nd highest number of new cases of T1D estimated to be from the USA [1]. Epidemiological studies indicate ~40% of T1D cases reported globally are associated with polymorphism in the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) gene; however, the recent increase in the T1D numbers among children, in parallel with reduced frequency of HLA genotype, indicate increased environmental pressure, as a responsible factor [2–4]. As a result, our understanding of the disease pathology has evolved to the current model that T1D results from a combination of genetic predisposition and various environmental triggers that activate and accelerate disease severity.

The combinatorial disease concept underlying T1D was first proposed by Eisenbarth, who defined and parsed the T1D progression stage from the initiation stage [5]. This work redefined strategies for therapeutic development targeting each stage of the disease. For instance, insulin replacement, which remains the gold-standard therapy, was developed and used as a first-line therapeutic option to treat T1D [6,7]. Several advances, such as the development of the insulin pump and genetically modified long-lasting insulins, have shown promise for minimizing injections and better controlling insulin delivery. There have also been significant efforts in developing preventative therapies targeting the immune responses responsible for pancreatic β cell death. While immunomodulatory therapies like Cyclosporine A, anti-CD3/20 antibodies, and IL-1 inhibitors are only able to delay the onset of the disease, there remains significant interest in developing next-generation immunomodulators targeting immune systems Treg cells, B lymphocytes, and CD3 coreceptor [6,8–10]. Lastly, combinatorial treatment strategies that act at multiple stages of T1D, including the artificial pancreas, stem cell mobilization, β cell encapsulation, and SGLT2 inhibitors, show promising returns in the clinic [6]. However, trials are still in the early stages, and the cost-benefit of these therapies compared to traditional treatments has yet to be determined.

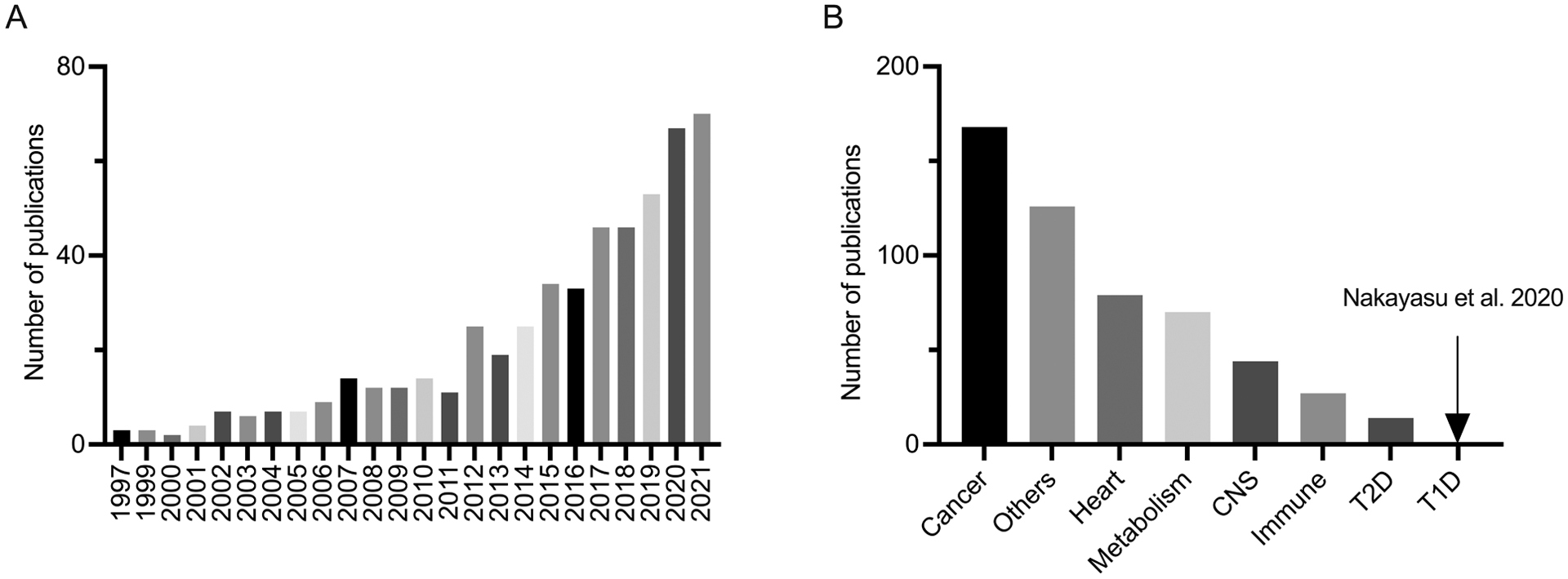

Current therapeutic options only manage T1D, demanding novel and efficient therapies that prevent or delay disease onset. Growth differentiation factor 15 (GDF15 - also known as macrophage inhibitory cytokine 1 & NSAID-activated gene 1 protein and placental TFG-β) a known diabetes biomarker, has triggered widespread interest in this regard due to its impressive tissue-protective actions over the last 2 decades in broad range of metabolic disorders (Fig. 1A, B & Table S1) [11]. The discovery of GDF15’s primary receptor and associated signaling pathway has further bolstered its potential as a druggable target [12]. A recent study by our team has specifically demonstrated the benefits of GDF15 in reducing insulitis and T1D onset [13]. In this review, we map multiple GDF15-relevant pathways in T1D pathology and discuss the therapeutic potential of GDF15 in the treatment of T1D.

Figure 1. Trends of published research articles related to GDF15.

A. represents the distribution of GDF15 research articles published since 1997. B. represents the number of GDF15 research articles arranged according to the topics (CNS: central nervous system, T2D: type 2 diabetes, T1D: type 1 diabetes). The articles containing titles with GDF15 or its aliases (i.e., MIC-1, NAG-1, PTGFB, PALB, & NRG1) were curated using the PubMed search tool, specifically excluding reviews, meta-analysis, commentary, & corrections in our analysis.

2. GDF15: A functionally pleiotropic molecule

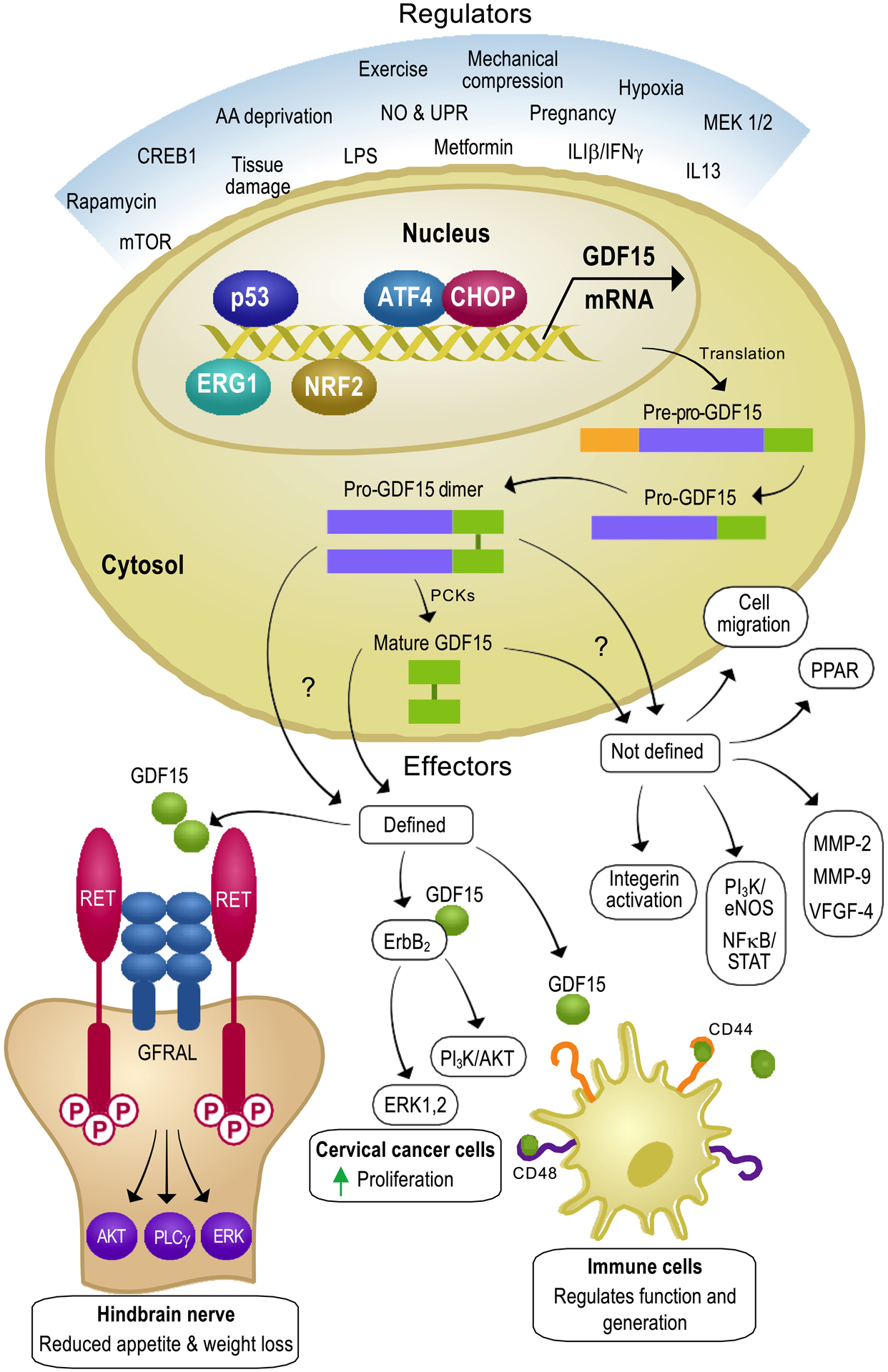

GDF15 is a secreted cytokine, independently discovered by three research groups in 1997 [14–16]. Despite its low sequence homology to TGF-β, GDF15 has been classified as a distant member of the TGF-β family due to the presence of a unique cysteine knot characteristic of this class of molecules. GDF15 is expressed in most tissues as a 308 amino acid propeptide monomer form, which dimerizes via a disulfide linkage between the cysteines in the C-terminus. The pro-protein dimer undergoes proteolytic cleavage at an RXXR residue by a furine-like protease to release the mature GDF15 dimer of 25 kDa into the extracellular space [15,17–21]. In plasma, GDF15 exists in a broad concentration ranging from 0.15 to 1.15 ng/mL and potentially in both proGDF15 and mature GDF15 forms [21,22]. Levels of GDF15 are impacted by plethora of metabolic factors, exercise, tissue injury, pregnancy, hypoxia, and drugs like metformin and rapamycin represented in Fig. 2. Given its central role and metabolic sensitivity, GDF15 is emerging as a premier biomarker to determine prognoses in a number of health disorders, including T1D [11,23,24].

Figure 2. Regulators and effectors of GDF15.

GDF15 is expressed in most human tissues in response to various signals, including tissue damage, hypoxia, mechanical compression and many more. The protein biosynthesis of GDF15 is well-documented and includes pro-GDF15 dimer and mature GDF15 synthesis. It is still not very clear which of these protein forms are functionally relevant as they both are secreted in the plasma. Once released, they have a plethora of effectors, which can be broadly classified as defined and undefined mechanisms. Under defined mechanisms, GDF15 has been shown to interact with 3 distinct receptors i.e., GFRAL, ErbB2 and CD44, which have been reported to have different effects. In addition, there exists a large number of undefined correlational effects of GDF15, which could be the result of either direct or indirect mechanisms.

Recently, the interest in GDF15 has spiked due to multiple landmark studies that independently identified the Glial-cell-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) family receptor α-like (GFRAL) receptor as the primary receptor for GDF15 [25–28]. GFRAL is primarily expressed in the area postrema (A.P.) and the nucleus of the hindbrain’s solitary tract (NST) neurons. Using GFRAL deficient mice, it has been demonstrated that GDF15 acts on GFRAL in the hindbrain, signaling through AKT, ERK, and PLCγ pathways which reduce appetite and ultimately result in weight loss [25,28]. In addition, it was observed that administration of GDF15 accelerates lipid oxidation and was thought to be secondary to AKT/ERK signaling, which contributes to the observed weight loss phenotype [26,27,29]. Taken together, these studies suggest that GDF15 has a significant impact on pathways critical for energy expenditure. This notion was reinforced by Shuang and colleagues, who demonstrated that GDF15 could specifically regulate lipid metabolism by stimulating hepatic triglyceride secretion via β adrenergic signaling [30]. In addition, multiple studies have demonstrated improved glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity [31,32]. Whether this improvement is an indirect effect of weight reduction or directly induced by ectopic expression of GDF15 has yet to be determined. Regardless, these studies make GDF15 a highly enticing therapeutic target for treating obesity and other metabolic epidemics currently plaguing the USA [29,33,34].

While GDF15 is best recognized for its influence on metabolism, it acts in several homeostatic mechanisms in the body. Multiple studies have now shown that GDF15 plays a critical anti-inflammatory role in tissue injury. Most of our mechanistic insights on the role of GDF15 in inflammation come from an early study by Kempf and colleagues, who reported that GDF15 inhibits integrin activation and thereby dampens cytokine signaling and infiltration of pro-inflammatory cells in heart infarcts [35]. In addition, Abulizi et al. and Santos et al. demonstrated that GDF15 deficiency exacerbates the inflammatory response to the sepsis affected tissue, but its role is highly contextual [36,37]. Similarly, in animal models of T1D, Deelman and colleagues showed that GDF15 deficiency results in increased expression of inflammatory markers [38]. In contrast, Santos et al. showed that GDF15’s immunomodulatory role has also been demonstrated in tumorigenesis and cancer progression with contradictory viewpoints, making it difficult to clearly define its underlying mechanism of action as an anti-inflammatory molecule [39–41]. However, the above studies indicate a tissue-protective role of GDF15 in addition to the parasympathetic signaling axis.

Apart from systemic effects, GDF15’s direct impact on tissues and cells has been well documented. For example, GDF15 was found to directly interact with avian erythroblastosis oncogene B 2(ErbB2) receptor, which activates AKT and ERK pathways [42,43]. Likewise, upregulation of GDF15 by Tumor protein 53 (TP53) activates the Phosphoinositide 3-kinase/endothelial nitric oxide synthase (PI3K/eNOS) pathway and downregulates the Nuclear Factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells/c-Jun N-terminal Kinase (NF-κB/JNK) pathways [44]. Recently two groups independently have identified novel interactions of GDF15 with surface receptors of immune cells [45,46]. Wang et al., shows GDF15 interacts with CD48 on T cells and regulates the function and population of competent Treg cells against hepatocellular carcinoma [45]. Whereas, Gao et al., outlines the mechanism of immune escape of ovarian cancer regulated by GDF15-CD44 interaction in dendritic cells [46]. As GFRAL receptors are reported to be exclusively in the hindbrain, the above studies indicate the existence of a potentially non-GFRAL receptor. Nonetheless, reports of GFRAL receptors detected in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma tissue and our unpublished preliminary data from pancreatic islets imply that GFRAL might not be as exclusive as previously thought [47]. Therefore, these pieces of evidence point towards a gap in our understanding of GDF15’s molecular mechanism. Consequently, further studies are warranted, which eventually would aid in developing a robust GDF15 therapy for multiple disease modalities, including T1D.

3. GDF15: a bridge between T2D and T1D

Obesity is a known risk factor for type 2 diabetes (T2D), as it is considered one of the environmental triggers for genetically predisposed individuals [48]. Obesity is marked by metabolic dysregulation and is associated with increased GDF15 levels [49–52]. The connection between GDF15 and T2D has also been reported by several studies [53,54]. Further, various papers have looked at increased GDF15 levels in obese and diabetic patients, with GDF15 being regarded as a marker for both [20,49,55,56]. GDF15, primarily identified as macrophage inhibitory cytokine 1(MIC-1), has been associated with ameliorating inflammation-mediated cellular stress [14]. Accordingly, interleukin-13 (IL-13) has been known to regulate glucose metabolism, insulin sensitivity, and glucose tolerance via GDF15 [57]. Plus, in a comprehensive human study, an increase in GDF15 levels in early-stage T2D indicated GDF15’s anti-inflammatory response to the onset of diabetes [55]. Therefore, as obesity and diabetes are both associated with chronic inflammation, there exists a strong connection between GDF15 and diabetes in the context of the immune response that needs to be explored further [58].

In addition to inflammation, endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress is also considered a common contributor to T1D and T2D pathogenesis [59]. As a link between GDF15 and a known ER stress protein C/EBP Homologous Protein (CHOP) exists, the possibility of a relationship between GDF15, T1D, and T2D through ER stress is not farfetched [60]. Moreover, clinical studies have implicated that metformin, an insulin-sensitizer widely used to treat T2D patients, exerts its function by activating endogenous GDF15, which reduces ER and mitochondrial oxidative stress [61–65]. Together, these studies assert GDF15 as a bridge between T1D and T2D, which could help develop treatment strategies for both diseases.

4. GDF15’s role in T1D pathogenesis

There is growing evidence indicating GDF15’s involvement in T1D pathogenesis. For instance, recent studies suggest that peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) and AMP-protein kinase (AMPK) both play vital roles in glucose metabolism and can ameliorate T1D development in NOD mice through the activation of GDF15 [66–68]. Similarly, a study by Lertpatipanpong et al. reported that, in transgenic mice, overexpressing GDF15 improves insulin sensitivity and protects pancreatic islets against streptozotocin-mediated β cell destruction [69]. In line with these results, we have reported that human islets and human β cells exposed to pro-inflammatory cytokines have a significant decrease in GDF15, which is similar to pancreatic tissue sections obtained from human T1D cadaveric donors. To understand the mechanism of this reduction we found that GDF15 mRNA translation was blocked by pro-inflammatory cytokines, which acted as a bottle neck. Moreover, when we pretreated human islets with recombinant GDF15 (rGDF15), we saw enhanced protection against pro-inflammatory cytokine-mediated β cell apoptosis/death [13]. Finally, we were able to determine that rGDF15 significantly reduced insulitis and increase β cell survival. We are at present trying to understand the underlying mechanism of our observation and hypothesis that GDF15 effects transcend through the GFRAL receptor found on the β cell surface. Collectively, these data suggest that GDF15 could be a likely target for T1D prevention and management. Hence, these connections are discussed in detail with the relative gaps in knowledge and future area of research below.

5. GDF15: the makings of a T1D therapy

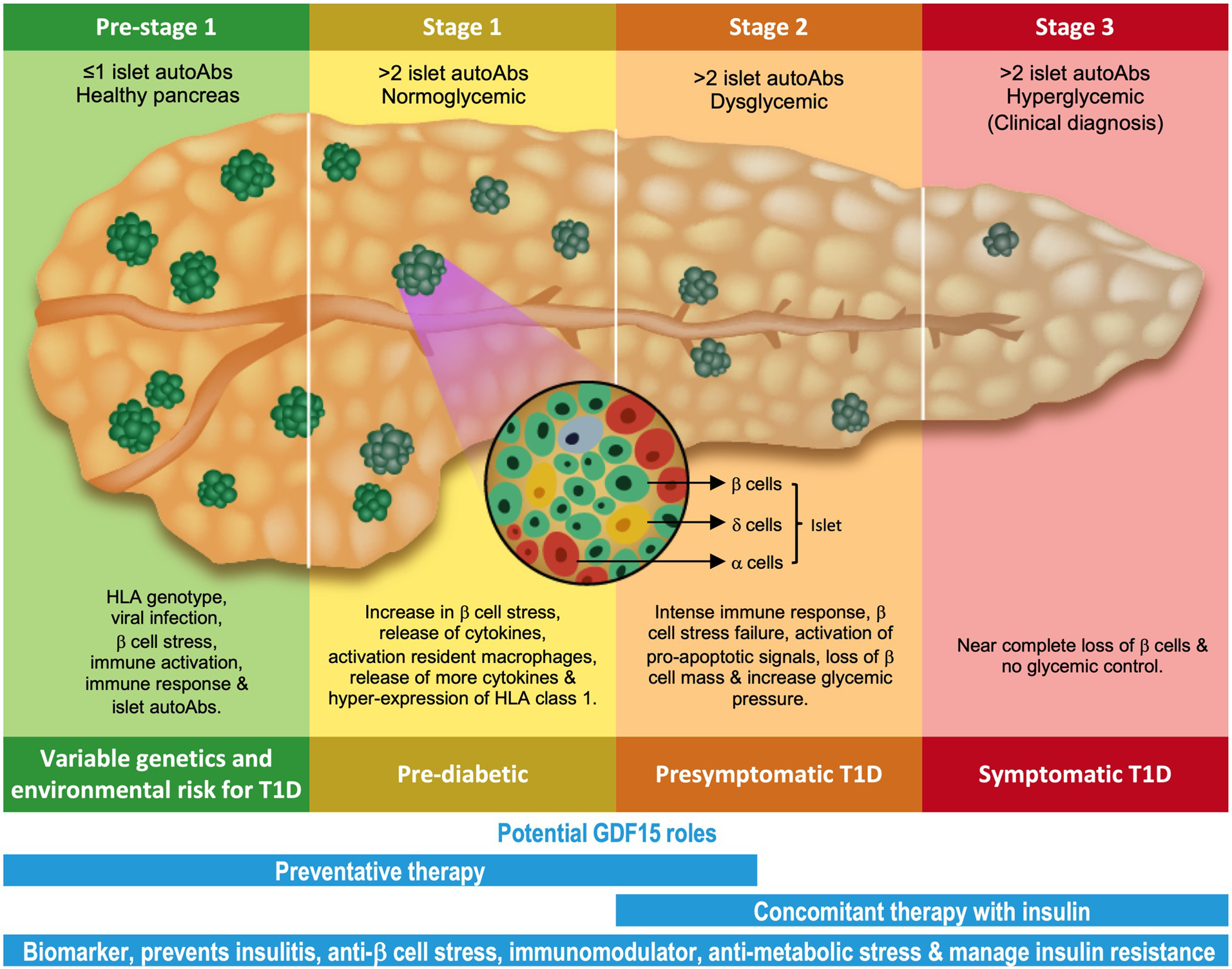

Studies since the early 1980’s suggest that T1D is a multi-stage disease, broadly divided into three major stages and one pre-stage (Fig. 3) [70,71]. The pre-stage of T1D is mainly associated with genetic mutation of the HLA gene, triggered by various environmental factors such as β cell mass, β cell stress, pancreatic size, congenital rubella/enterovirus infections, or metabolic stress [72–74]. These factors initiate immune activation and response towards pancreatic β cells. Based on this classification, early treatment strategies have mainly focused on developing anti-inflammatory drugs to treat the onset of T1D, with no long-term success [6,8–10]. Nevertheless, interest in this area persists, as multiple clinical studies are being performed worldwide to develop next-generation immunomodulatory drugs against T1D initiation [75]. Following the trend, GDF15 has been associated with immunosuppressant activity and is regarded as the first anti-inflammatory cytokine to demonstrate regulation of chemokine-triggered leukocyte integrin activation [30,35,76,77]. Therefore, GDF15 could be deemed as a lucrative immunomodulatory target in the future. However, there is a growing paradigm shift in the field regarding T1D pathogenesis. According to the latest consensus, the pancreas is not considered the target of the immune response; and instead, it is regarded as the initiator of immune activation [78,79]. Therefore, this could be a potential rationale for the lack of any successful immunomodulatory drug so far.

Figure 3. Schematic representing the stages of T1D and the potential GDF15 therapeutic roles.

T1D is divided into 3 main stages and one pre-stage 1. The pre-stage 1 is marked by HLA genotype which gets triggered by an insult, such as viral infection, β cell stress or both. This initiates immune activation and response, leading to increased β cell stress and hyper HLA expression. Eventually, these events initiate pro-apoptotic signals and cause loss of β cell mass. GDF15 is an established biomarker for T1D and has been shown to reduce T1D insulitis. The potential roles of GDF15 in preventing or slowing the progression of T1D could be a combination of anti-β cell stress, immunomodulatory effect, management of metabolic stress and finally, restoration of glycemic control. Overall, GDF15 has the potential to be developed as a preventative therapy for pre-stage 1 to stage 2, or a concomitant therapy along with insulin to reduce the progression of the disease in the later stages.

Subsequently, scientists in the field have diverted their attention to understanding T1D β cell physiology that potentially instigates immune response [73,74,79]. Out of the number of factors, cytokines from neighboring macrophage cells or immune cells initiate β cell stress, which activates STAT1, IRF1, and NFκB pathways to hyper-express HLA class 1 protein, which is responsible for initiating a full-blown immune response [80–83]. GDF15 has been associated with the downregulation of the NFκB/STAT pathways in endothelial cells to attenuate cell apoptosis in response to high glucose stimulus [44]. As GDF15 in islets increases cell survival and decreases insulitis, together, the above studies imply a direct effect of GDF15 on β cell fate through NFκB/STAT pathways, which counteracts cytokine-mediated HLA-induced immune response [13]. Furthermore, GDF15 is associated with regulating mitochondrial dysfunction and ER stress, both of which are considered crucial in aggravating β cell stress and initiating inflammation [60,80,84–86]. Evidence of GDF15 being the target of p53 and its role in activating pro-survival pathways(AKT/ERK) suggests GDF15 could have a direct protective role towards pancreatic β cells [42,44]. In summary, GDF15 can be developed as a holistic therapy, focusing on its direct β cell function against T1D initiation, whereas the indirect effect of GDF15 through the immune system should be explored with caution (Fig. 3).

As outlined previously, T1D is an autoimmune disease; however, metabolic and neurological implications contribute significantly to the progression of T1D. It is well documented that the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems regulate various branches of glucose homeostasis, including regulation of hormone secretion (insulin & glucagon) and maintenance of β cell populations in our body [87]. Therefore, researchers have started investigating the neuronal contribution to diabetes pathology [88–90]. To this end, as mentioned earlier, GFRAL receptors are present in the brainstem, nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS), and hypothalamus, implying a possible regulation of glucose homeostasis by GDF15 through stimulation of sympathetic and parasympathetic signaling [12,91,92]. This link is another addition to the growing list of potential GDF15 crosstalk with factors responsible for T1D, ultimately bolstering the therapeutic potential of GDF15 (Fig. 3).

6. Therapeutic future of GDF15

The discovery of GDF15’s dedicated receptor has helped clear some of the ambiguity regarding GDF15’s mechanism of action and related effects, which has opened a plethora of new therapeutic possibilities in the field. Initial studies have shown that manipulating GDF15/GFRAL signaling cascade in mice and nonhuman primates causes weight loss and regulates body metabolism [25,29]. Consequently, GDF15 related therapies are being developed to treat obesity, cancer-induced cachexia, heart disease, and many more metabolic disorders [29,93,94]. In addition, there is a steady rise in the number of GDF15-related clinical trials. According to ClinicaITrial.gov, 104 clinical trials are looking into GDF15 as a biomarker or potential drug target. Interestingly, only six studies in this list are related to T2D, while none are on T1D, indicating a large area for future studies with a therapeutic focus (Table S1).

Often increased circulating GDF15 levels documented in various disease pathologies are contradictory, yet the exogenous administration of GDF15 has consistently been demonstrated to be beneficial in regulating normal cellular functions [95–99]. Generally, GDF15 expression levels play a vital role in transcending its effect in the body, and therefore most treatment strategies focus on regulating its level in the system. However, developing GDF15 as a potential therapy has been challenging due to its very short half-life and its susceptibility to proteolytic cleavage in the serum [29,100]. The addition of recombinant modifications like human serum albumin (HAS) and fragment crystallization region of immunoglobulin G (FC) has significantly extended GDF15 protein half-life without hampering its associated anorexia and weight loss phenotypes [28,29,101]. Direct targeting of GDF15 transcription regulators like MKKK/p38, p53, and Egr-1, or post-transcriptional regulators like tristetraprolin (TTP), are also being explored as therapeutic options [102,103].

High GDF15 levels induce vomiting and nausea in patients, posing a critical risk to GDF15 therapeutic endeavors [104,105]. As a result, exploring small molecules like XIB4035 and BT13, which can mimic GDF15 effects by targeting GFRAL/RET receptor signaling, could potentially increase the target specificity and reduce off-target effects [34,106]. In addition, approaches like reducing the dosage of GDF15 agonist should be explored for temporary relief. Furthermore, an alternative strategy to achieve the targeted GDF15 effect could be by implementing antibody strategies targeting the GDF15/GFRAL signaling axis. As antibodies against GDF15 or GFRAL receptors have been utilized to outline the GDF15-GFRAL circuitry, multiple studies are underway to explore its efficacy in mitigating GDF15’s side effects [26,29,93]. As GDF15 is pleiotropic, there is a high probability that any GDF15 agonist therapies might fail in the clinical trials due to unwanted effects in the body. Therefore, a combination of an agonist and an antagonist therapy targeting specific regions of the body, such that the agonist only affects the area of interest, could hold the key to increasing GDF15’s precision and reducing its side effects. Such technology is being developed by Pondion therapeutics for targeting PDL1 and Ionis pharmaceutical for GLP1 receptor. However, whether such concepts can be applied to GDF15 therapy need to be explored and tested.

7. Conclusion

The current standards of T1D therapy have not changed significantly in that Insulin replacement is still considered the most cost effective and easily available treatment option worldwide. However, efforts to develop therapeutics that target the early stages of T1D are gaining ground in preclinical studies. In alignment with this, we have reported that GDF15 prevents insulitis and delays the development of diabetes in prediabetic mice [13]. Additional research discussed above points to a direct or indirect β cell protection by GDF15, which makes it a potential concomitant therapy with Insulin. This strategy is particularly beneficial in the early stages of T1D, where patients may have some functional β cells remaining in the islets. Therefore, using early indicators of risk for developing T1D, such as family medical history, genetic predisposition for HLA gene mutation, and the presence and number of islet autoantibodies could help in identifying the appropriate time for GDF15 therapy. We hypothesize that administration of GDF15 therapy at the right stage of T1D could delay clinical onset by potentially preserving the remaining β cells. Further, administration of GDF15 could increase the success of islet replacement therapies for those patients receiving such treatment. Overall, β cell protection by GDF15, if demonstrated in humans, could significantly improve T1D patient outcomes. However, there are still significant questions that need to be addressed by thorough fundamental work to understand GDF15’s precision, efficacy, and long-term effects in humans.

8. Expert Opinion

Generally, around 90% of therapies fail at the clinical development stage due to poor pharmacokinetics, toxicity, and/or lack of efficacy [107,108]. This high failure rate accounts for an enormous economic burden on the drug development process and eventually discourages real innovation. The common reasons for this lack of success are usually associated with the poor predictive ability of preclinical studies for human efficacy and randomized controlled clinical trials [109]. Recently, a study by Cheung et al. performed a Mendelian randomized study to look at serum GDF15 relationship with cardiometabolic phenotype and reported no effect of GDF15 on anthropometric measurement in human subjects [110]. They further suggested that the effects observed in animal studies might be different in humans and advised caution for future drug development ventures. The study accounted for various SNPs found in serum GDF15; however, there is a possibility of GDF15 existing in 4 different protein forms in the serum, out of which only one is considered active and thought to produce the characteristic functions [21,111]. Therefore, the conclusion drawn by Cheung et al. might have looked at a mixed population of GDF15, which could explain the lack of GDF15 association with weight loss in humans. Nevertheless, the study points out a valid concern regarding GDF15’s therapeutic blind spot, i.e., translation from bench to bedside. Therefore, we suggest the application of a systems pharmacology approach, which accounts for genome-wide association (GWA), proteome-wide association (PWA), and phenome-wide association studies (PheWAS) with exhaustive pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic (PD/PK) studies, to help develop a robust GDF15 therapy to target T1D.

As mentioned earlier, the pleiotropic nature of GDF15 makes it an exciting target but has the potential to be a therapeutic challenge. Its potential to cause several side effects upon administration can jeopardize its precision and efficacy. Therefore, research focusing on GDF15 fidelity is of utmost priority. One approach to curtail this unwanted outcome would be implementing chronotherapy strategies in the GDF15 drug development plan. Since the 1970’s, various drugs are being evaluated with respect to chronotherapy which utilizes our body’s innate time-keeping system called the circadian clock to determine the right time of drug/therapy administration, such that it reduces potential side effects and increases its efficacy and precision [112,113]. The circadian clock is a vital homeostatic mechanism present in almost every cell of our body and known to regulate about 50% of all protein-coding genes in humans, creating various physiological and biochemical rhythms synced to the natural night and day cycle [114,115]. Due to the circadian nature of multiple genes in the body, it is becoming evident that drugs show low to no effect, if administered at the wrong time of the day, when the target concentration is low. This can also in some cases lead to pronounced unwanted effect of the drug [116,117]. Therefore, knowing the drug target and its associated mechanism with respect to circadian timing could offer a solution.

With regards to T1D, circadian clock is known to regulate body glucose metabolism and immune response in our body [118–120]. Plus, a study by Takahashi & Bass’s group has demonstrated that loss of clock in pancreatic islets can trigger diabetes onset due to impaired β cell function [121]. Indeed, the connection between the circadian clock and T1D seems logical. Likewise, studies have reported GDF15 as a clock-controlled gene with a nominal diurnal circadian rhythmicity in human serum, and the GFRAL receptor being expressed in the hippocampus, spinal cord, and thalamus regions of the brainstem, NTS and area postrema (AP), which are associated with the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), aka master circadian clock, solidifies the possibility of a connection [12,91,114,122–124]. Therefore, applying chronotherapy strategies in the GDF15 therapeutic undertaking might be beneficial to determine a specific time of the day to administer GDF15, such that it produces a precise effect with no or minimal side effects. However, the lack of a defined GDF15 mechanism in T1D presents a significant challenge to develop it as a chronotherapy. Tools are being developed to measure the internal timing of the effector tissue, or measure daily rhythms of sleep and temperature by wearable sensors (less invasive) which can speed up the development of chronomedicines in the future [113,125]. Such advances can offer an avenue for honing and improving GDF15 therapy for T1D treatment as well. In addition, exploring tissue/cell type-specific delivery or activation of GDF15 to reduce possible side effects might be of worth as well.

Finally, in our opinion, the absence of a well-defined GDF15 mechanism of action in T1D pathology is an imperative hurdle that needs immediate attention. Though discovering the GFRAL receptor helped alleviate some mysticism, identifying the receptor exclusively in the brain tissue creates ambiguity regarding the evidence showing GDF15’s direct action on peripheral tissue. Thus, presenting the question of whether GDF15 can act on peripheral tissue directly or indirectly through the GFRAL-β adrenergic signaling pathway. Further, studies showing a difference in effect based on GDF15 structures, i.e., matured vs. proGDF15, have brought into question the established signaling pathways [21,22]. Therefore, these crucial gaps in knowledge needs to be addressed in future studies.

In conclusion, with the increasing number of T1D cases in pediatric patients, new and efficient strategies are needed more than ever. None of the current therapies for T1D are sufficient to prevent the disease by themselves, plus they have been known to have severe drawbacks in the long run. Therefore, a systems approach in developing a therapy for T1D is necessary. As our knowledge regarding T1D pathogenesis has grown, we have evolved from the initial viewpoint of T1D being only a pancreatic disease to a more complex macro and micro environmental dysfunction. In alignment with this thought, GDF15 possesses the potential to address T1D holistically and could push us closer to a cure.

Supplementary Material

Article highlights.

The stress-induced growth differentiating factor-15 (GDF15) has been documented to play a critical role in a number of diseases.

The recent discovery of potential receptor targets of GDF15 has brought significant attention to the field due to its therapeutic possibilities.

Recently we have demonstrated that GDF15 ameliorates β-cell death during the initial stages of T1D progression.

However, the pleotropic nature of GDF15 poses a significant challenge for its therapeutic potential.

There remains a gap in knowledge regarding GDF15’s pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic characteristics in various diseases, including T1D. Therefore, further in-depth research is warranted.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases grant U01 DK127786 (to R.G.M and T.O.M.) and U01 DK127505 (to E.S.N.). Battelle operates PNNL for the U.S. Department of Energy under contract DE-AC05-76RLO01830.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as either of interest (•) or of considerable interest (••) to readers

- 1.Federation ID. IDF diabetes atlas ninth. Dunia: IDF. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nguyen C, Varney MD, Harrison LC, et al. Definition of high-risk type 1 diabetes HLA-DR and HLA-DQ types using only three single nucleotide polymorphisms. Diabetes. 2013;62(6):2135–2140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hermann R, Knip M, Veijola R, et al. Temporal changes in the frequencies of HLA genotypes in patients with Type 1 diabetes—indication of an increased environmental pressure? Diabetologia. 2003;46(3):420–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fourlanos S, Varney MD, Tait BD, et al. The rising incidence of type 1 diabetes is accounted for by cases with lower-risk human leukocyte antigen genotypes. Diabetes care. 2008;31(8):1546–1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eisenbarth GS. Type I diabetes mellitus. New England journal of medicine. 1986;314(21):1360–1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pathak V, Pathak NM, O’Neill CL, et al. Therapies for type 1 diabetes: current scenario and future perspectives. Clinical Medicine Insights: Endocrinology and Diabetes. 2019;12:1179551419844521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.von Scholten BJ, Kreiner FF, Gough SC, et al. Current and future therapies for type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2021:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; *Detailed review of latest T1D therapies in use and in development.

- 8.Group C-ERCT. Cyclosporin-induced remission of IDDM after early intervention: association of 1 yr of cyclosporin treatment with enhanced insulin secretion. Diabetes. 1988;37(11):1574–1582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keymeulen B, Walter M, Mathieu C, et al. Four-year metabolic outcome of a randomised controlled CD3-antibody trial in recent-onset type 1 diabetic patients depends on their age and baseline residual beta cell mass. Diabetologia. 2010;53(4):614–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moran A, Bundy B, Becker DJ, et al. Interleukin-1 antagonism in type 1 diabetes of recent onset: two multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. The Lancet. 2013;381(9881):1905–1915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hess G, Horsch A, Zdunek D. Gdf-15 as biomarker in type 1 diabetes. Google Patents; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rochette L, Zeller M, Cottin Y, et al. Insights into mechanisms of GDF15 and receptor GFRAL: therapeutic targets. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakayasu ES, Syed F, Tersey SA, et al. Comprehensive proteomics analysis of stressed human islets identifies GDF15 as a target for type 1 diabetes intervention. Cell metabolism. 2020;31(2):363–374. e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; **Shows that GDF15 translation is blocked in T1D pancreas, and exogenous treatment prevents insulitis progression in NOD mice and isolated human pancreatic tissues.

- 14.Bootcov MR, Bauskin AR, Valenzuela SM, et al. MIC-1, a novel macrophage inhibitory cytokine, is a divergent member of the TGF-β superfamily. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1997;94(21):11514–11519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hromas R, Hufford M, Sutton J, et al. PLAB, a novel placental bone morphogenetic protein. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Gene Structure and Expression. 1997;1354(1):40–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lawton LN, de Fatima Bonaldo M, Jelenc PC, et al. Identification of a novel member of the TGF-beta superfamily highly expressed in human placenta. Gene. 1997;203(1):17–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paralkar VM, Vail AL, Grasser WA, et al. Cloning and characterization of a novel member of the transforming growth factor-β/bone morphogenetic protein family. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273(22):13760–13767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fairlie W, Moore A, Bauskin A, et al. MIC‐1 is a novel TGF‐β superfamily cytokine associated with macrophage activation. Journal of leukocyte biology. 1999;65(1):2–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moore A, Brown DA, Fairlie WD, et al. The transforming growth factor-β superfamily cytokine macrophage inhibitory cytokine-1 is present in high concentrations in the serum of pregnant women. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2000;85(12):4781–4788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ding Q, Mracek T, Gonzalez-Muniesa P, et al. Identification of macrophage inhibitory cytokine-1 in adipose tissue and its secretion as an adipokine by human adipocytes. Endocrinology. 2009;150(4):1688–1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baek SJ, Eling T. Growth differentiation factor 15 (GDF15): A survival protein with therapeutic potential in metabolic diseases. Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2019 2019/June/01/;198:46–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lockhart SM, O’Rahilly S. Colchicine—an old dog with new tricks. Nature Metabolism. 2021 2021/April/01;3(4):451–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bauskin AR, Brown DA, Kuffner T, et al. Role of macrophage inhibitory cytokine-1 in tumorigenesis and diagnosis of cancer. Cancer research. 2006;66(10):4983–4986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mimeault M, Batra SK. Divergent molecular mechanisms underlying the pleiotropic functions of macrophage inhibitory cytokine‐1 in cancer. Journal of cellular physiology. 2010;224(3):626–635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mullican SE, Lin-Schmidt X, Chin C-N, et al. GFRAL is the receptor for GDF15 and the ligand promotes weight loss in mice and nonhuman primates. Nature medicine. 2017;23(10):1150–1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; **Identification of GFRAL, the GDF15 receptor, and its dowstreatm mechanism. The authors also reported the interaction between GFRAL-GDF15 is important for weight loss phenotype.

- 26.Emmerson PJ, Wang F, Du Y, et al. The metabolic effects of GDF15 are mediated by the orphan receptor GFRAL. Nature medicine. 2017;23(10):1215–1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; **Confirmation of GFRAL as the GDF15 receptor. The authors showed the use of antiGFRAL antibodies to block GDF15-induced body weight and food intake suppression. They also detected GFRAL in mouse, rat and monkey tissues.

- 27.Hsu J-Y, Crawley S, Chen M, et al. Non-homeostatic body weight regulation through a brainstem-restricted receptor for GDF15. Nature. 2017;550(7675):255–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; **This paper confrmed GFRAL as a GDF15 receptor and confirmed its location in the area postrema and nucleus tractus solitarius of the mouse brainstem. They showed Gfral knockout mice are resistant to chemotherapy-induced anorexia and body weight loss. They further outline the neuronal circuitary activated by GDF15 in the brain.

- 28.Yang L, Chang C-C, Sun Z, et al. GFRAL is the receptor for GDF15 and is required for the anti-obesity effects of the ligand. Nature medicine. 2017;23(10):1158–1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; **Confirmation of GFRAL as the GDF15 receptor and its location in the hindbrain responsible for systemic metabolic effects. They further outline the mechanism of the GDF15-induced weight loss phenotype.

- 29.Xiong Y, Walker K, Min X, et al. Long-acting MIC-1/GDF15 molecules to treat obesity: Evidence from mice to monkeys. Science translational medicine. 2017;9(412). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; **Developed extended half-life recombinent GDF15 and further identified the presence of GFRAL in various species.

- 30.Luan HH, Wang A, Hilliard BK, et al. GDF15 is an inflammation-induced central mediator of tissue tolerance. Cell. 2019;178(5):1231–1244. e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; *GDF15 is induced following LPS exposure and assists in the initiation of the β-adrenergic signaling cascade, resulting in tissue-protective hepatic triglyceride outflow.

- 31.Chrysovergis K, Wang X, Kosak J, et al. NAG-1/GDF-15 prevents obesity by increasing thermogenesis, lipolysis and oxidative metabolism. International journal of obesity. 2014;38(12):1555–1564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Macia L, Tsai VW-W, Nguyen AD, et al. Macrophage inhibitory cytokine 1 (MIC-1/GDF15) decreases food intake, body weight and improves glucose tolerance in mice on normal & obesogenic diets. PloS one. 2012;7(4):e34868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang D, Day EA, Townsend LK, et al. GDF15: emerging biology and therapeutic applications for obesity and cardiometabolic disease. Nature Reviews Endocrinology. 2021 2021/October/01;17(10):592–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sidorova YA, Bespalov MM, Wong AW, et al. A novel small molecule GDNF receptor RET agonist, BT13, promotes neurite growth from sensory neurons in vitro and attenuates experimental neuropathy in the rat. Frontiers in pharmacology. 2017;8:365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; **Identification of RET, co-receptor of GFRAL, activating molecule.

- 35.Kempf T, Zarbock A, Widera C, et al. GDF-15 is an inhibitor of leukocyte integrin activation required for survival after myocardial infarction in mice. Nature medicine. 2011;17(5):581–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abulizi P, Loganathan N, Zhao D, et al. Growth differentiation factor-15 deficiency augments inflammatory response and exacerbates septic heart and renal injury induced by lipopolysaccharide. Scientific reports. 2017;7(1):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Santos I, Colaço HG, Neves-Costa A, et al. CXCL5-mediated recruitment of neutrophils into the peritoneal cavity of Gdf15-deficient mice protects against abdominal sepsis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2020;117(22):12281–12287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mazagova M, Buikema H, van Buiten A, et al. Genetic deletion of growth differentiation factor 15 augments renal damage in both type 1 and type 2 models of diabetes. American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology. 2013;305(9):F1249–F1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vaňhara P, Hampl A, Kozubík A, et al. Growth/differentiation factor-15: prostate cancer suppressor or promoter? Prostate cancer and prostatic diseases. 2012;15(4):320–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Breit SN, Johnen H, Cook AD, et al. The TGF-β superfamily cytokine, MIC-1/GDF15: a pleotrophic cytokine with roles in inflammation, cancer and metabolism. Growth factors. 2011;29(5):187–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wischhusen J, Melero I, Fridman WH. Growth/differentiation factor-15 (GDF-15): from biomarker to novel targetable immune checkpoint. Frontiers in Immunology. 2020;11:951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li S, Ma Y-M, Zheng P-S, et al. GDF15 promotes the proliferation of cervical cancer cells by phosphorylating AKT1 and Erk1/2 through the receptor ErbB2. Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research. 2018;37(1):1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li C, Wang J, Kong J, et al. GDF15 promotes EMT and metastasis in colorectal cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7(1):860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li J, Yang L, Qin W, et al. Adaptive induction of growth differentiation factor 15 attenuates endothelial cell apoptosis in response to high glucose stimulus. PloS one. 2013;8(6):e65549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang Z, He L, Li W, et al. GDF15 induces immunosuppression via CD48 on regulatory T cells in hepatocellular carcinoma. Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer. 2021;9(9):e002787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gao Y, Xu Y, Zhao S, et al. Growth differentiation factor-15 promotes immune escape of ovarian cancer via targeting CD44 in dendritic cells. Experimental Cell Research. 2021 2021/May/01/;402(1):112522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhao Z, Zhang J, Yin L, et al. Upregulated GDF-15 expression facilitates pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma progression through orphan receptor GFRAL. Aging (Albany NY). 2020;12(22):22564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; **These findings point to GFRAL not being completely isolated to the hindbrain, and may be also found in the pancreas. This is notable for further exploration into GDF15’s effect on the pancreatic β-cells.

- 48.Wilkin T The accelerator hypothesis: weight gain as the missing link between type I and type II diabetes. Diabetologia. 2001;44(7):914–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dostálová I, Roubicek T, Bártlová M, et al. Increased serum concentrations of macrophage inhibitory cytokine-1 in patients with obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus: the influence of very low calorie diet. European Journal of Endocrinology. 2009;161(3):397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kempf T, Guba-Quint A, Torgerson J, et al. Growth differentiation factor 15 predicts future insulin resistance and impaired glucose control in obese nondiabetic individuals: results from the XENDOS trial. European Journal of Endocrinology. 2012;167(5):671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vila G, Riedl M, Anderwald C, et al. The relationship between insulin resistance and the cardiovascular biomarker growth differentiation factor-15 in obese patients. Clinical Chemistry. 2011;57(2):309–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kralisch S, Hoffmann A, Estrada-Kunz J, et al. Increased Growth Differentiation Factor 15 in Patients with Hypoleptinemia-Associated Lipodystrophy. Int J Mol Sci. 2020. Sep 29;21(19). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Melhem S, Steven S, Taylor R, et al. Effect of Weight Loss by Low-Calorie Diet on Cardiovascular Health in Type 2 Diabetes: An Interventional Cohort Study. Nutrients. 2021. Apr 26;13(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Niu Y, Zhang W, Shi J, et al. The Relationship Between Circulating Growth Differentiation Factor 15 Levels and Diabetic Retinopathy in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:627395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Carstensen M, Herder C, Brunner EJ, et al. Macrophage inhibitory cytokine-1 is increased in individuals before type 2 diabetes diagnosis but is not an independent predictor of type 2 diabetes: the Whitehall II study. European Journal of Endocrinology. 2010. 01 May. 2010;162(5):913–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xu J, Kimball TR, Lorenz JN, et al. GDF15/MIC-1 functions as a protective and antihypertrophic factor released from the myocardium in association with SMAD protein activation. Circulation research. 2006;98(3):342–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lee SE, Kang SG, Choi MJ, et al. Growth differentiation factor 15 mediates systemic glucose regulatory action of T-helper type 2 cytokines. Diabetes. 2017;66(11):2774–2788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Berg AH, Lin Y, Lisanti MP, et al. Adipocyte differentiation induces dynamic changes in NF-κB expression and activity. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Eizirik DL, Pasquali L, Cnop M. Pancreatic β-cells in type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus: different pathways to failure. Nature Reviews Endocrinology. 2020;16(7):349–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Li D, Zhang H, Zhong Y. Hepatic GDF15 is regulated by CHOP of the unfolded protein response and alleviates NAFLD progression in obese mice. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2018;498(3):388–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Day EA, Ford RJ, Smith BK, et al. Metformin-induced increases in GDF15 are important for suppressing appetite and promoting weight loss. Nature Metabolism. 2019;1(12):1202–1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schernthaner-Reiter M, Itariu B, Krebs M, et al. GDF15 reflects beta cell function in obese patients independently of the grade of impairment of glucose metabolism. Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases. 2019;29(4):334–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Coll AP, Chen M, Taskar P, et al. GDF15 mediates the effects of metformin on body weight and energy balance. Nature. 2020;578(7795):444–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ouyang J, Isnard S, Lin J, et al. GDF-15 as a Weight Watcher for Diabetic and Non-Diabetic People Treated With Metformin [Review]. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2020 2020-November-18;11(911). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yang M, Darwish T, Larraufie P, et al. Inhibition of mitochondrial function by metformin increases glucose uptake, glycolysis and GDF-15 release from intestinal cells. Sci Rep. 2021. Jan 28;11(1):2529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Maganti AV, Tersey SA, Syed F, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ activation augments the β-cell unfolded protein response and rescues early glycemic deterioration and β cell death in non-obese diabetic mice. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2016;291(43):22524–22533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Aguilar-Recarte D, Barroso E, Gumà A, et al. GDF15 mediates the metabolic effects of PPARβ/δ by activating AMPK. Cell Reports. 2021;36(6):109501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lin S-C, Hardie DG. AMPK: Sensing Glucose as well as Cellular Energy Status. Cell Metabolism. 2018 2018/February/06/;27(2):299–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lertpatipanpong P, Lee J, Kim I, et al. The anti-diabetic effects of NAG-1/GDF15 on HFD/STZ-induced mice. Scientific Reports. 2021;11(1):1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Couper JJ, Haller MJ, Greenbaum CJ, et al. ISPAD Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines 2018: Stages of type 1 diabetes in children and adolescents. Pediatric diabetes. 2018;19:20–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.DiMeglio LA, Evans-Molina C, Oram RA. Type 1 diabetes. Lancet. 2018. Jun 16;391(10138):2449–2462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Eizirik DL, Colli ML, Ortis F. The role of inflammation in insulitis and β-cell loss in type 1 diabetes. Nature Reviews Endocrinology. 2009;5(4):219–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Campbell-Thompson M, Wasserfall C, Montgomery EL, et al. Pancreas organ weight in individuals with disease-associated autoantibodies at risk for type 1 diabetes. Jama. 2012;308(22):2337–2339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dotta F, Censini S, van Halteren AG, et al. Coxsackie B4 virus infection of β cells and natural killer cell insulitis in recent-onset type 1 diabetic patients. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2007;104(12):5115–5120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pathak V, Pathak NM, O’Neill CL, et al. Therapies for Type 1 Diabetes: Current Scenario and Future Perspectives. Clin Med Insights Endocrinol Diabetes. 2019;12:1179551419844521–1179551419844521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Moon JS, Goeminne LJ, Kim JT, et al. Growth differentiation factor 15 protects against the aging‐mediated systemic inflammatory response in humans and mice. Aging cell. 2020;19(8):e13195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ratnam NM, Peterson JM, Talbert EE, et al. NF-κB regulates GDF-15 to suppress macrophage surveillance during early tumor development. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2017;127(10):3796–3809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.GF B Lawrence lecture. Death of a beta cell: homicide or suicide. Diabet Med. 1986;3(2):119–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Roep BO, Thomaidou S, van Tienhoven R, et al. Type 1 diabetes mellitus as a disease of the β-cell (do not blame the immune system?). Nature Reviews Endocrinology. 2021;17(3):150–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gysemans C, Callewaert H, Overbergh L, et al. Cytokine signalling in the β-cell: a dual role for IFNγ. Biochemical Society Transactions. 2008;36(3):328–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wyatt RC, Lanzoni G, Russell MA, et al. What the HLA-I!-Classical and Non-classical HLA Class I and Their Potential Roles in Type 1 Diabetes. Curr Diab Rep. 2019;19(12):159–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Carrero JA, McCarthy DP, Ferris ST, et al. Resident macrophages of pancreatic islets have a seminal role in the initiation of autoimmune diabetes of NOD mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2017;114(48):E10418–E10427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Marroqui L, Dos Santos RS, Op de beeck A, et al. Interferon-α mediates human beta cell HLA class I overexpression, endoplasmic reticulum stress and apoptosis, three hallmarks of early human type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2017 2017/April/01;60(4):656–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sivitz WI, Yorek MA. Mitochondrial dysfunction in diabetes: from molecular mechanisms to functional significance and therapeutic opportunities. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;12(4):537–577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Moore F, Naamane N, Colli ML, et al. STAT1 is a master regulator of pancreatic β-cell apoptosis and islet inflammation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2011;286(2):929–941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yatsuga S, Fujita Y, Ishii A, et al. Growth differentiation factor 15 as a useful biomarker for mitochondrial disorders. Annals of neurology. 2015;78(5):814–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Güemes A, Georgiou P. Review of the role of the nervous system in glucose homoeostasis and future perspectives towards the management of diabetes. Bioelectronic medicine. 2018;4(1):1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chandra R, Liddle RA. Recent advances in the regulation of pancreatic secretion. Current opinion in gastroenterology. 2014;30(5):490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rodriguez-Diaz R, Caicedo A. Neural control of the endocrine pancreas. Best practice & research Clinical endocrinology & metabolism. 2014;28(5):745–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Rosario W, Singh I, Wautlet A, et al. The brain–to–pancreatic islet neuronal map reveals differential glucose regulation from distinct hypothalamic regions. Diabetes. 2016;65(9):2711–2723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Li Z, Wang B, Wu X, et al. Identification, expression and functional characterization of the GRAL gene. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2005;95(2):361–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Mullican SE, Rangwala SM. Uniting GDF15 and GFRAL: Therapeutic Opportunities in Obesity and Beyond. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2018. Aug;29(8):560–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Jones JE, Cadena SM, Gong C, et al. Supraphysiologic administration of GDF11 induces cachexia in part by upregulating GDF15. Cell reports. 2018;22(6):1522–1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lerner L, Tao J, Liu Q, et al. MAP3K11/GDF15 axis is a critical driver of cancer cachexia. Journal of cachexia, sarcopenia and muscle. 2016;7(4):467–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lajer M, Jorsal A, Tarnow L, et al. Plasma growth differentiation factor-15 independently predicts all-cause and cardiovascular mortality as well as deterioration of kidney function in type 1 diabetic patients with nephropathy. Diabetes care. 2010;33(7):1567–1572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Myhre PL, Prebensen C, Strand H, et al. Growth differentiation factor 15 provides prognostic information superior to established cardiovascular and inflammatory biomarkers in unselected patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Circulation. 2020;142(22):2128–2137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wu X, Xuan W, You L, et al. Associations of GDF-15 and GDF-15/adiponectin ratio with odds of type 2 diabetes in the Chinese population. Endocrine. 2021;72(2):423–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Brown DA, Lindmark F, Stattin P, et al. Macrophage inhibitory cytokine 1: a new prognostic marker in prostate cancer. Clinical cancer research. 2009;15(21):6658–6664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Falkowski B, Rogowicz-Frontczak A, Szczepanek-Parulska E, et al. Novel biochemical markers of neurovascular complications in type 1 diabetes patients. Journal of clinical medicine. 2020;9(1):198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bauskin AR, Brown DA, Junankar S, et al. The propeptide mediates formation of stromal stores of PROMIC-1: role in determining prostate cancer outcome. Cancer research. 2005;65(6):2330–2336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Fung E, Kang L, Sapashnik D, et al. Fc-GDF15 glyco-engineering and receptor binding affinity optimization for body weight regulation. Sci Rep. 2021. Apr 26;11(1):8921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tiedje C, Diaz-Muñoz MD, Trulley P, et al. The RNA-binding protein TTP is a global post-transcriptional regulator of feedback control in inflammation. Nucleic acids research. 2016;44(15):7418–7440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Eling TE, Baek S-J, Shim M-s, et al. NSAID activated gene (NAG-1), a modulator of tumorigenesis. BMB Reports. 2006;39(6):649–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Borner T, Shaulson ED, Ghidewon MY, et al. GDF15 Induces Anorexia through Nausea and Emesis. Cell Metab. 2020. Feb 4;31(2):351–362.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Fejzo MS, Arzy D, Tian R, et al. Evidence GDF15 Plays a Role in Familial and Recurrent Hyperemesis Gravidarum. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2018. Sep;78(9):866–870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Hedstrom KL, Murtie JC, Albers K, et al. Treating small fiber neuropathy by topical application of a small molecule modulator of ligand-induced GFRα/RET receptor signaling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2014;111(6):2325–2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Paul SM, Mytelka DS, Dunwiddie CT, et al. How to improve R&D productivity: the pharmaceutical industry’s grand challenge. Nature reviews Drug discovery. 2010;9(3):203–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hay M, Thomas DW, Craighead JL, et al. Clinical development success rates for investigational drugs. Nature biotechnology. 2014;32(1):40–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Hingorani AD, Kuan V, Finan C, et al. Improving the odds of drug development success through human genomics: modelling study. Scientific Reports. 2019 2019/December/11;9(1):18911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Cheung C-L, Tan KC, Au PC, et al. Evaluation of GDF15 as a therapeutic target of cardiometabolic diseases in human: a Mendelian randomization study. EBioMedicine. 2019;41:85–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Assadi A, Zahabi A, Hart RA. GDF15, an update of the physiological and pathological roles it plays: a review. Pflügers Archiv - European Journal of Physiology. 2020 2020/November/01;472(11):1535–1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Dallmann R, Brown SA, Gachon F. Chronopharmacology: New Insights and Therapeutic Implications. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology. 2014;54(1):339–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Adam D Core Concept: Emerging science of chronotherapy offers big opportunities to optimize drug delivery. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2019;116(44):21957–21959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Ashok Kumar PV, Dakup PP, Sarkar S, et al. It’s About Time: Advances in Understanding the Circadian Regulation of DNA Damage and Repair in Carcinogenesis and Cancer Treatment Outcomes. Yale J Biol Med. 2019;92(2):305–316. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Ruben MD, Wu G, Smith DF, et al. A database of tissue-specific rhythmically expressed human genes has potential applications in circadian medicine. Science translational medicine. 2018;10(458). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Damato AR, Luo J, Katumba RGN, et al. Temozolomide chronotherapy in patients with glioblastoma: a retrospective single-institute study. Neuro-Oncology Advances. 2021;3(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Dakup PP, Porter KI, Little AA, et al. The circadian clock regulates cisplatin-induced toxicity and tumor regression in melanoma mouse and human models. Oncotarget. 2018;9(18):14524–14538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Cailotto C, La Fleur SE, Van Heijningen C, et al. The suprachiasmatic nucleus controls the daily variation of plasma glucose via the autonomic output to the liver: are the clock genes involved? European Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;22(10):2531–2540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Druzd D, Matveeva O, Ince L, et al. Lymphocyte circadian clocks control lymph node trafficking and adaptive immune responses. Immunity. 2017;46(1):120–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Gibbs JE, Blaikley J, Beesley S, et al. The nuclear receptor REV-ERBα mediates circadian regulation of innate immunity through selective regulation of inflammatory cytokines. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2012;109(2):582–587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Marcheva B, Ramsey KM, Buhr ED, et al. Disruption of the clock components CLOCK and BMAL1 leads to hypoinsulinaemia and diabetes. Nature. 2010;466(7306):627–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Anzulovich-Miranda AC. Circadian Synchronization of Cognitive Functions. Psychiatry and Neuroscience Update: Springer; 2015. p. 141–156. [Google Scholar]

- 123.Zhao L, Isayama K, Chen H, et al. The nuclear receptor REV-ERBα represses the transcription of growth/differentiation factor 10 and 15 genes in rat endometrium stromal cells. Physiol Rep. 2016. Feb;4(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Tsai VW, Macia L, Feinle-Bisset C, et al. Serum Levels of Human MIC-1/GDF15 Vary in a Diurnal Pattern, Do Not Display a Profile Suggestive of a Satiety Factor and Are Related to BMI. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0133362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Vlachou D, Bjarnason GA, Giacchetti S, et al. TimeTeller: a New Tool for Precision Circadian Medicine and Cancer Prognosis. bioRxiv. 2020:622050. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.