Abstract

Background and Purpose:

Although the US Black population has a higher incidence of stroke compared to the US White population, few studies have addressed Black-White differences in the contribution of vascular risk factors to the population burden of ischemic stroke in young adults.

Methods:

A population-based case-control study of early-onset ischemic stroke, ages 15-49 years, was conducted in the Baltimore-Washington DC region between 1992 and 2007. Risk factor data was obtained by in-person interview in both cases and controls. The prevalence, odds ratio, and population-attributable risk percent (PAR%) of smoking, diabetes, and hypertension was determined among Black patients and White patients, stratified by sex.

Results:

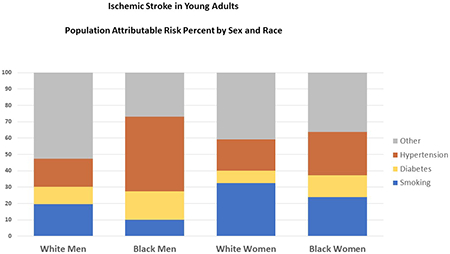

The study included 1,044 cases and 1,099 controls. Of the cases, 47% were Black patients, 54% were men and the mean (±standard deviation) age was 41.0 (±6.8) years. For smoking, the PAR% were: White men 19.7%, White women 32.5%, Black men 10.1% and Black women 23.8%. For diabetes, the PAR% were: White men 10.5%, White women 7.4%, Black men 17.2%, and Black women 13.4%. For hypertension, the PAR% were: White men 17.2%, White women 19.3%, Black men 45.8%, and Black women 26.4%.

Conclusions:

Modifiable vascular risk factors account for a large proportion of ischemic stroke in young adults. Cigarette smoking was the strongest contributor to stroke among White patients while hypertension was the strongest contributor to stroke among Black patients. These results support early primary prevention efforts focused on smoking cessation and hypertension detection and treatment.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

The incidence of stroke in young adults is increasing1 and is the eighth leading cause of death in 25-45 year-olds in the US.2 Both the incidence and mortality of stroke are higher in the Black compared to the White population, particularly at younger ages.3 Smoking, diabetes, and hypertension are important contributors to the burden of ischemic stroke in young adults4 but few studies have addressed the differential importance of these risk factors by race in this population. Therefore, we determined the prevalence, odds ratio (OR), and population-attributable risk percent (PAR%) of these risk factors, stratified by race and sex, in the Stroke Prevention in Young Adults Study.

Methods

The Stroke Prevention in Young Adults Study was designed as a population-based case–control study of early-onset ischemic stroke. Anonymized phenotype data that support the findings of this study are available from dbGaP (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/gap/cgi-bin/study.cgi?study_id=phs000292.v1.p1). During 3 study periods between 1992 and 2008, cases with a first-ever ischemic stroke ages 15-49 years were identified by discharge surveillance from 59 hospitals in the Baltimore/Washington, DC area and by direct referral from regional neurologists. Controls obtained by random digit dialing were frequency-matched to cases by age, sex, region of residence, and, except for the initial study phase, were additionally matched for race. Details of the study design and case adjudication have been previously described.5 A standardized interview was used to obtain information from both cases and controls about stroke risk factors, including age, race, current smoking status, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension. The study was approved by the University of Maryland at Baltimore Institutional Review Board and all participants gave written informed consent.

Statistical analysis was performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). The analysis was restricted to participants who self-identified their race as Black or White. All analyses were stratified by race and sex. We calculated the prevalence of current smoking status, diabetes, and hypertension for each race-sex group. Logistic regression was used to calculate age-adjusted OR and to test for interactions by race. PAR% was calculated using the prevalence and OR for each risk factor.6 The study was conducted in accordance with the STROBE guideline for case-control studies; the STROBE checklist can be found in the supplemental materials.

Results

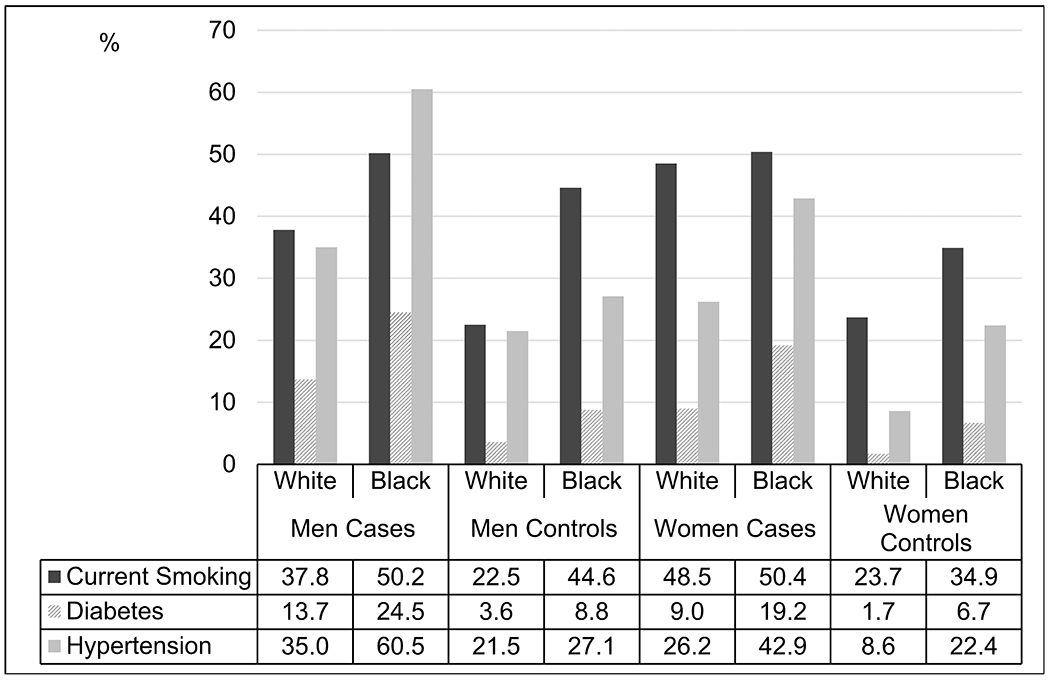

There were 1,044 cases and 1,099 controls. Of the cases, 47% were Black patients, 54% were men. The mean ± standard deviation (SD) age of cases was 41.0 ± 6.8 years and 38.6 ± 7.4 years for controls. For both cases and controls, the prevalence of smoking, diabetes, and hypertension was higher among Blacks compared to Whites (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of Vascular Risk Factors Stratified by Race and Sex

The OR for smoking was significantly higher among Whites compared to Blacks in each sex group, particularly among women (OR 2.9 vs OR 1.7; p=0.007) (Table 1). The mean packs per day among cases in the 4 race-sex groups were White men 1.20, Black men 0.65, White women 1.03, Black women 0.76. The OR for hypertension was higher among Black men compared to White men (OR 3.9 vs OR 1.8; p=0.0008), but there was no significant difference among women.

Table 1.

Age-Adjusted Odds Ratio of Vascular Risk Factors for Ischemic Stroke and 95% Confidence Interval

| Risk Factor | White Men OR (95% CI) |

Black Men OR (95% CI) |

P Value* | White Women OR (95% CI) |

Black Women OR (95% CI) |

P Value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (Cases/Controls) | 622 (315/307)† | 453 (249/204)‡ | 585 (235/350)§ | 483 (245/238)‖ | ||

| Current Smoking | 2.2 (1.6-3.1) | 1.5 (0.8-1.7) | 0.03 | 2.9 (2.0-4.0) | 1.7 (1.2-2.4) | 0.007 |

| Diabetes | 3.6 (1.8-7.1) | 3.2 (1.8-5.7) | 0.77 | 5.2 (2.1-12.9) | 2.7 (1.5-5.0) | 0.71 |

| Hypertension | 1.8 (1.3-2.6) | 3.9 (2.6-5.9) | 0.0008 | 3.8 (2.4-6.1) | 2.4 (1.6-3.6) | 0.93 |

P-value for interaction by race

1 case missing hypertension data

1 case and 1 control missing hypertension data

1 case and 1 control missing diabetes data, 2 cases missing hypertension data

1 case missing smoking data, 1 control missing hypertension data

Using prevalence and OR of each risk factor, PAR% was determined and demonstrated similar results (Table 2). Smoking was the strongest contributor to ischemic stroke in the White patients, particularly among White women (PAR 32.5%). Hypertension was the strongest contributor to ischemic stroke among the Black patients, particularly among Black men (PAR 45.8%). Among both men and women, diabetes was a stronger contributor to ischemic stroke among Black compared to White patients.

Table 2.

Population-Attributable Risk Percent and 95% Confidence Interval of Vascular Risk Factors for Ischemic Stroke

| Risk Factor | White Men PAR% (95% CI) |

Black Men PAR% (95% CI) |

White Women PAR% (95% CI) |

Black Women PAR% (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current Smoking | 19.7 (15.0-24.2) | 10.1 (2.5-17.1) | 32.5 (27.8-36.9) | 23.8 (17.9-29.3) |

| Diabetes | 10.5 (8.1-12.9) | 17.2 (13.9-20.4) | 7.4 (5.5-9.3) | 13.4 (10.4-16.3) |

| Hypertension | 17.2 (12.6-21.6) | 45.8 (41.1-50.1) | 19.3 (16.0-22.5) | 26.4 (21.7-30.8) |

Discussion

We found that vascular risk factors are responsible for a high proportion of ischemic stroke in young adults, particularly smoking among White patients and hypertension among Black patients. The higher OR and PAR% for smoking among White patients may be due to the higher number of cigarettes smoked among White current smokers. The higher OR and PAR% for hypertension among Black patients may be due, in part, to the earlier onset and longer duration of hypertension in this group.3 The prevalence of current smoking and hypertension have increased among young adults hospitalized with acute ischemic stroke in the United States7, suggesting an opportunity for stroke prevention through risk factor modification.

A prior study of 296 cases of stroke in young adults in the same geographic region examined the PAR% of current smoking, diabetes and hypertension among Black and White patients.8 In contrast to our findings, this study reported a higher PAR% of smoking among Black compared to White patients (40.5% Black men, 29.1% Black women vs 22.6% White men, 17.2% White women). Consistent with our findings, this study reported a higher PAR% of hypertension among Black compared to White patients (53.0% Black men, 50.5% Black women vs 21.7% White men, 21.3% White women). The differences between the two studies in smoking prevalence among controls may be due to differences in study methodology. The present study obtained both case and control risk factor data in person using the same structured interview. In contrast, the earlier study obtained case information from chart review and control information from a risk factor survey conducted by the Center for Disease Control. Study differences may also be due to the different time periods of the participant recruitment.

The multinational European Stroke in Young Fabry Patients study4 also evaluated the PAR% of risk factors for ischemic stroke in young adults ages 18-55 years but did not provide race- or sex-stratified findings. The PAR% of smoking was 15.0%, similar to our findings among men but lower than our findings among women. The PAR% of hypertension was 25.2%, lower than our finding among Black men but similar to our findings in the other race-sex groups.

The primary limitation of our observational study is the case-control design with the inherent potential for bias due to selection bias in recruitment of case and control participants, differential recall, and unrecognized confounding. Specifically, we did not include hyperlipidemia, body mass index, alcohol and illicit drug use, which may have been confounders in our analysis. In addition, since risk factor status was self-reported, the prevalence of hypertension and diabetes among those with limited access to health care providers may be underestimated.

Despite these limitations, our study shows the impact of modifiable vascular risk factors, specifically smoking and hypertension, on ischemic stroke in young adults, and highlights the importance of smoking in White patients and hypertension in Black patients. These results emphasize the need for early primary prevention efforts focused on smoking cessation and hypertension detection and treatment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

The contributions of Esther Berrent to the operational success of the Stroke Prevention in Young Adults Study are gratefully acknowledged.

Sources of Funding:

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the VA Maryland Health Care System, Baltimore, Maryland and was also supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (R01NS45012, R01NS105150, R01NS100178). The contents do not represent the views of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Non-standard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- OR

Odds Ratio

- PAR

Population Attributable Risk

Footnotes

Disclosure: None

Online Supplemental Data: Racial and Ethnic Disparities Reporting Guidelines Checklist, STROBE Checklist

References

- 1.Kissela BM, Khoury JC, Alwell K, Moomaw CJ, Woo D, Adeoye O, Flaherty ML, Khatri P, Ferioli S, De Los Rios La Rosa F et al. Age at Stroke: Temporal trends in stroke incidence in a large, biracial population. Neurology. 2012;79:1781–1787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heron M Deaths: Leading causes for 2017. Natl Vital Stat Reports. 2019;68. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr68/nvsr68_06-508.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carnethon MR, Pu J, Howard G, Albert MA, Anderson CAM, Bertoni AG, Mujahid MS, Palaniappan L, Taylor HA, Willis M et al. Cardiovascular Health in African Americans: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;136:e393–e423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aigner A, Grittner U, Rolfs A, Norrving B, Siegerink B, Busch MA. Contribution of Established Stroke Risk Factors to the Burden of Stroke in Young Adults. Stroke. 2017;48:1744–1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hamedani AG, Cole JW, Cheng Y, Sparks MJ, O’Connell JR, Stine OC, Wozniak MA, Stern BJ, Mitchell BD, Kittner SJ. Factor V Leiden and Ischemic Stroke Risk: The Genetics of Early Onset Stroke (GEOS) Study. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;22:419–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fleiss JL. Statistical methods for rates and proportions. 2nd ed. New York: Wiley; 1981:94–95. [Google Scholar]

- 7.George MG, Tong X, Bowman BA. Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and strokes in younger adults. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74:695–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rohr J, Kittner S, Feeser B, Hebel JR, Whyte MG, Weinstein A, Kanarak N, Buchholz D, Earley C, Johnson C et al. Traditional Risk Factors and Ischemic Stroke in Young Adults: The Baltimore-Washington Cooperative Young Stroke Study. Arch Neurol. 1996;53:603–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.