Abstract

Introduction

To complement results of the SUSTAIN program, this study assessed effectiveness and safety of once weekly subcutaneous semaglutide in people with type 2 diabetes (T2D) managed under routine care.

Methods

This was a multicenter, observational, retrospective study including all patients treated with semaglutide. Changes in clinical outcomes from baseline to 6 and 12 months were assessed in patients who were glucagon-like peptide receptor agonist (GLP-1RA) naïve or switching from another GLP-1RA. Discontinuation rate was assessed.

Results

Overall, 216 patients (mean age 64 years, 65.7% men) were evaluated: 135 (61.5%) naïve and 81 (38.5%) switchers from another GLP-1RA. In the naïve cohort, after 6 months from semaglutide initiation, levels of HbA1c significantly decreased by − 1.31% (p < 0.0001). All obesity indices improved, with mean reductions in body weight of − 3.92 kg, in BMI of − 1.43 kg/m2, and in waist circumference of − 5.03 cm. In the switcher cohort, statistically significant improvements in HbA1c (− 0.78%), body weight (− 2.64 kg), and waist circumference (− 3.03 cm) were obtained after 6 months. Reductions were sustained after 12 months in both cohorts (mean semaglutide dose: 0.86 mg in naïve and 0.96 mg in switcher cohort). Blood pressure and lipid profile mean levels decreased after 12 months from semaglutide initiation in both cohorts. No severe hypoglycemia occurred; 6.5% of patients discontinued semaglutide (2.8% due to gastrointestinal side effects).

Conclusion

Effectiveness and tolerability of semaglutide have been confirmed in the real world irrespective of diabetes duration and severity. As expected, more marked reductions in HbA1c and obesity indices were obtained in naïve patients, but it is noteworthy that relevant improvements were also obtained in patients already treated with GLP-1RAs.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13300-022-01218-y.

Keywords: Type 2 diabetes, GLP-1 receptor agonists, Semaglutide, Naïve, Switch

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| In the SUSTAIN Program, once-weekly (ow) subcutaneous semaglutide, the most recent glucagon-like peptide receptor agonist (GLP-1RA) available in Italy, has shown safety and clinically relevant improvements in glycemic control and body weight versus a wide range of comparators in people with type 2 diabetes (T2D). |

| Real-world evidence (RWE) data generation is crucial not only to confirm safety and effectiveness of this drug in routine clinical practice but also to complement evidence from randomized clinical trials. |

| What was learned from the study? |

| This study confirms the effectiveness and tolerability of semaglutide in real-world clinical practice, without any new safety concerns. |

| Patients receiving semaglutide experienced statistically significant and clinically relevant glycemic reduction and obesity index improvements. These results are documented not only in GLP-1RA naïve patients, but also in patients already treated with other GLP-1RAs. |

Introduction

The global prevalence of diabetes has reached pandemic proportions, and diabetes has emerged as one of the most serious and common chronic diseases of these times, causing life-threatening, disabling, and costly complications and reducing life expectancy [1]. Recently, the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes updated the position statements on the optimal management of type 2 diabetes (T2D) in adults; similarly, the Italian guidelines were reviewed [2–4] to focus on the innovative perspectives of new diabetes therapies. Specifically, guidelines now recommend glucagon-like peptide receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs) with proven cardiovascular (CV) benefit as one of the two preferred options for add-on therapy in T2D people with established atherosclerotic CV disease after metformin and lifestyle intervention. GLP-1RAs are also recommended in patients not meeting individualized glycemic goals and needing to minimize hypoglycemia or promote weight loss [3]. In patients with a previous CV event, the new Italian Guidelines recommend metformin, GLP-1RA, or sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors as first-line options because of their documented CV protection [4].

GLP-1RA class now includes several molecules, which can be classified according to their origin, structure, duration of action, and mode of administration [5, 6]. The most recent GLP-RA commercially available in Italy is once weekly subcutaneous (s.c.) semaglutide. It was designed as a powerful, long-acting GLP-1 analogue. Semaglutide has 94% sequence homology with native GLP-1 and three key structural differences that provide extended pharmacokinetics: substitution of Ala with Aib at position 8 increases enzymatic (DPP4) stability, attachment of a linker and C18 di-acid chain at position 26 provides strong binding to albumin, and substitution of Lys with Arg at position 34 prevents C18 fatty acid binding at the wrong site [7, 8].

It has been shown that once weekly GLP-1RA administration, rather than once daily, can significantly improve patient convenience and adherence [9]. Efficacy and safety of semaglutide s.c. have been proven in the SUSTAIN program: semaglutide 1 mg reduced glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels up to 1.8% from baseline, and 57–74% of patients experienced a reduction of HbA1c levels to < 7.0% with 0.5 mg and 67–79% with 1 mg. It also reduced body weight by up to 6.5 kg from baseline. Clinically relevant improvements were documented with semaglutide used as monotherapy or add-on therapy and in both GLP-1RA naïve and switcher patients. In addition, the SUSTAIN 6 trial demonstrated a significant reduction in major CV events with semaglutide versus placebo in patients with T2D at high CV risk. The hazard ratio (HR) for major adverse cardiac events (MACE) was 0.74 (95% CI 0.58, 0.95) in subjects treated with semaglutide versus placebo [10–17].

Real-world evidence (RWE) is increasingly used to complement evidence from randomized clinical trials and measure effectiveness and safety of new drugs when prescribed under routine clinical practice conditions [18, 19].

The objective of the present study was to report the real-world use and impact of semaglutide in patients with T2D who were GLP-1RA naïve or switchers, managed under routine care. Characteristics of patients receiving semaglutide were described for “phenotyping” the semaglutide-treated population. Therefore, 6 and 12 months after semaglutide initiation, changes in HbA1c, weight, and other key clinical parameters, discontinuation rate, and safety were assessed in both GLP-1RA naïve patients and those switching from another GLP-1RA.

Methods

This was a multicenter observational retrospective study, performed in three diabetes clinics in Umbria (Perugia, Città di Castello, Castiglione del Lago, Italy).

All patients treated with semaglutide s.c. were eligible for the study; no exclusion criteria were applied.

Data were retrospectively collected from electronic medical records (EMR). At baseline (i.e., the date of the first prescription of semaglutide, T0), the following information was collected: gender, age, diabetes duration, family history of diabetes, previous CV disease (stroke, myocardial infarction, ischemic heart disease, dilated cardiomyopathy), years from the diagnosis of the first major CV event, retinopathy, history of leg ulcer, smoking habit, HbA1c, obesity indices [weight, body mass index (BMI), waist circumference], systolic and diastolic blood pressure (SBP and PBP), lipid profile (total cholesterol, triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, renal function [creatinine, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), albuminuria], liver function [alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate transferase (AST), gamma GT (GGT)], previous diabetes therapy and drugs used in combination at the first prescription of semaglutide, antihypertensive drugs, and other chronic therapies.

Follow-up data collected after 6 (T6) and 12 (T12) months were: HbA1c, obesity indices, blood pressure, lipid profile, renal function, mean doses and dose change of semaglutide during follow-up, and time to and reason for semaglutide discontinuation.

Data on severe episodes of hypoglycemia (i.e., episodes requiring intervention of third parties) were also collected.

The study protocol was approved by the regional ethics committee of the participating centers (Umbria Regional Ethics Committee, approval no. 20338/20/ON—November 30, 2020). Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Statistical methods

Considering the preliminary descriptive nature of this study, a formal sample size calculation was not performed. However, a minimum sample size of 47 patients in each cohort allowed detection of a decrease in HbA1c levels of at least 0.5% with a statistical power of 90%, assuming an estimated standard deviation of differences of 1.0 and with a significance level (alpha) of 0.05.

Statistical analyses were performed by stratifying study population by previous use of GLP-1RAs: new GLP-1RA users (naïve cohort) and patients switching from another GLP-1RA to semaglutide (switcher cohort).

Descriptive data were summarized as mean and standard deviation for continuous variables or frequency and proportion for categorical variables. Baseline patient characteristics according to the study cohort were compared using the unpaired t-test or the Mann-Whitney U-test in case of continuous variables and the chi-square test or the Fisher exact test for categorical variables, as appropriate. Statistical significance was declared if p < 0.05.

The co-primary end points were the changes in HbA1c and weight after 6 months. All other changes in continuous clinical end points at 6 and 12 months represented secondary end points. In addition, the proportion of patients reaching HbA1c < 7% and weight loss > 5% was considered categorical secondary end points.

Changes in continuous study end points were assessed using mixed models for repeated measurements. Results are expressed as estimated mean or estimated mean difference from T0 with their 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Paired t-tests derived from linear mixed models for repeated measurements were applied for within-group comparisons in the naïve and switcher cohorts. Between-group comparisons were avoided because of systematic differences in the two study cohorts.

Results

Characteristics of patients treated with semaglutide

Overall, 216 patients (mean age 64 years, 65.7% men) treated with semaglutide were identified in EMRs, of whom 135 (61.5%) were GLP-1RA naïve and 81 (38.5%) switched from another GLP-1RA. The two groups differed in terms of diabetes duration (11.4 vs. 14.4 years; p = 0.004) and proportions of use of antiplatelets (33.3% vs. 18.5%, p = 0.02). Furthermore, 35.6% vs. 23.5% had a history of CV event, although statistical significance was not reached (p = 0.06). No other statistically significant differences emerged in the other baseline patient characteristics (Table 1). In both groups, wide variability (as indicated by the large standard deviations) in terms of age, diabetes duration, and HbA1c was observed.

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics at the first prescription of semaglutide

| Variable | Overall (mean ± SD or %) | Naïve (mean ± SD or %) | Switchers (mean ± SD or %) | p value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 216 | 135 | 81 | |

| Age (years) | 64.1 ± 10.4 | 64.1 ± 11.1 | 64.1 ± 9.2 | 0.67 |

| Males (%) | 65.7 | 65.2 | 66.7 | 0.82 |

| Diabetes duration(years) | 12.5 ± 8.3 | 11.4 ± 8.6 | 14.4 ± 7.5 | 0.004 |

| Family history of diabetes(%) | 59.8 | 62.5 | 55.8 | 0.44 |

| Previous cardiovascular disease | 31.0 | 35.6 | 23.5 | 0.06 |

| Stroke | 2.8 | 3.0 | 2.5 | 0.38 |

| Myocardial infarction | 23.6 | 26.7 | 18.5 | |

| Stroke + IMA | 1.9 | 2.2 | 1.2 | |

| Ischemic heart disease | 2.3 | 3.7 | 0.0 | |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy | 0.5 | 0.0 | 1.2 | |

| Years passed from the diagnosis of the first major cardiovascular event(years) | 5.1 ± 4.7 | 4.6 ± 4.0 | 6.5 ± 6.0 | 0.24 |

| Retinopathy (%) | 14.4 | 12.6 | 17.3 | 0.34 |

| History of leg ulcer (%) | 4.6 | 3.0 | 7.4 | 0.18 |

| Smokers (%) | ||||

| Yes | 15.8 | 14.7 | 17.9 | 0.66 |

| No | 47.5 | 46.1 | 50.0 | |

| Ex | 36.7 | 39.2 | 32.1 | |

| HbA1c (%) | 8.4 ± 1.4 | 8.4 ± 1.6 | 8.3 ± 1.3 | 0.79 |

| Obesity indices | ||||

| Waist circumference (cm) | 113.0 ± 14.1 | 114.0 ± 12.9 | 111.2 ± 16.1 | 0.25 |

| Weight (kg) | 94.6 ± 18.7 | 95.0 ± 17.5 | 94.0 ± 20.5 | 0.53 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 33.5 ± 5.9 | 33.7 ± 5.7 | 33.0 ± 6.3 | 0.21 |

| Blood pressure | ||||

| Systolic (mmHg) | 138.6 ± 16.2 | 137.3 ± 16.4 | 140.6 ± 15.9 | 0.17 |

| Diastolic (mmHg) | 79.9 ± 9.7 | 80.0 ± 9.6 | 79.8 ± 10.0 | 0.83 |

| Lipid profile | ||||

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 170.7 ± 41.9 | 171.3 ± 47.0 | 169.9 ± 33.0 | 0.88 |

| Triglycerides(mg/dl) | 172.4 ± 102.8 | 166.7 ± 96.6 | 181.4 ± 112.0 | 0.23 |

| HDL cholesterol(mg/dl) | 45.0 ± 10.5 | 45.3 ± 11.4 | 44.4 ± 8.9 | 0.87 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | 90.0 ± 33.8 | 91.1 ± 37.2 | 88.3 ± 27.9 | 0.96 |

| Renal function | ||||

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 1.0 ± 0.6 | 0.9 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.9 | 0.65 |

| eGFR (ml/min*1.73m2) | 79.8 ± 22.0 | 80.3 ± 21.7 | 79.0 ± 22.7 | 0.97 |

| eGFR < 60 ml/min*1.73m2(%) | 18.9 | 18.1 | 20.3 | 0.71 |

| Albuminuria (mg/dl) | 8.2 ± 14.5 | 6.7 ± 11.3 | 10.0 ± 17.6 | 0.20 |

| Hepatic function | ||||

| ALT (iu/l) | 30.3 ± 24.0 | 29.0 ± 21.3 | 32.2 ± 27.5 | 0.87 |

| AST (iu/l) | 28.2 ± 21.7 | 25.6 ± 16.2 | 31.9 ± 27.6 | 0.45 |

| GGT (iu/l) | 45.5 ± 59.3 | 43.1 ± 64.6 | 49.4 ± 49.7 | 0.052 |

| Antihypertensive drugs (%) | 59.7 | 57.8 | 63.0 | 0.45 |

| ARB | 16.2 | 14.8 | 18.5 | 0.47 |

| Diuretic | 21.8 | 23.7 | 18.5 | 0.37 |

| Calcium-antagonists | 27.8 | 25.9 | 30.9 | 0.43 |

| ACE-inhibitor | 29.2 | 25.9 | 34.6 | 0.18 |

| Beta blocker (%) | 28.2 | 30.4 | 24.7 | 0.37 |

| Lipid-lowering agents (%) | 38.4 | 40.7 | 34.6 | 0.37 |

| Statin | 37.0 | 39.3 | 33.3 | 0.38 |

| Ezetemibe | 6.5 | 6.7 | 6.2 | 0.89 |

| Anticoagulants (%) | 4.2 | 2.2 | 7.4 | 0.06 |

| Antiplatelets (%) | 27.8 | 33.3 | 18.5 | 0.02 |

*Unpaired t-test or Mann-Whitney U-test for continuous variables and chi-square test or Fisher exact test for categorical variables, as appropriate

Statistically significant p values (p < 0.05) are in bold

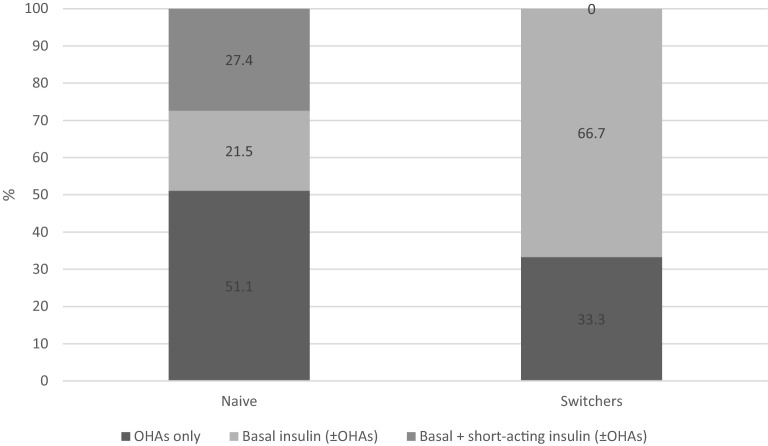

Among patients already treated with GLP-1RA, 52 (66.7%) switched from liraglutide 1.8 mg, 12 (15.4%) from dulaglutide, 7 (9.0%) from exenatide LAR, 5 (6.4%) from liraglutide 1.2 mg, 1 (1.3%) from liraglutide 0.6 mg, and 1 (1.3%) from lixisenatide 50 mg. Furthermore, 54 patients (66.7%) were treated with schemes including basal insulin, while the remainder were treated with oral hypoglycemic agents (OHA) only (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Treatment schemes at semaglutide initiation by cohort (naïve or switchers)

Among GLP-1RA-naïve patients, 69 (51.1%) were treated with OHAs only before starting semaglutide, while 66 (48.9%) were treated with basal insulin, of whom 37 (27.4%) were also prescribed short-acting insulin (Fig. 1). Therefore, previous and concomitant treatments varied within the naïve and switcher populations.

Concomitant glucose-lowering, antihypertensive, and lipid-lowering treatments were not modified during the study period.

Effectiveness of liraglutide

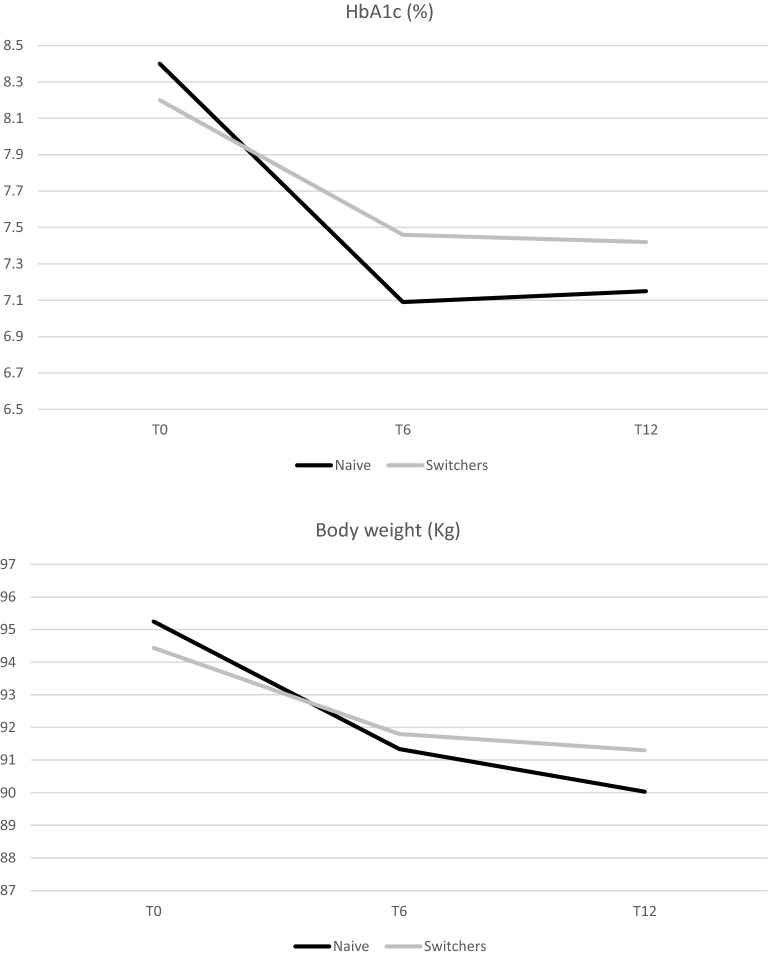

Data availability for each study end point at each visit is shown in Appendix 1. Changes in estimated mean levels of continuous end points during the follow-up and within-group comparisons (T6 vs. T0 and T12 vs. T0) are shown in Table 2 and Fig. 2.

Table 2.

Effectiveness of semaglutide: results of longitudinal models by treatment group

| Change in: | Visit | Naive | Switchers | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated mean and 95% CI | Estimated mean difference from T0 and 95% CI | Within group p value* |

Estimatedmean and 95% CI | Estimated mean difference from T0 and 95% CI | Within group pvalue* |

||

| HbA1c (%) | T0 |

8.4 (8.19;8.62) |

8.24 (7.95;8.53) |

||||

| T6 |

7.09 (6.85;7.34) |

− 1.31 (− 1.56;− 1.06) |

< 0.0001 |

7.46 (7.14;7.78) |

− 0.78 (− 1.11;− 0.45) |

< 0.0001 | |

| T12 |

7.15 (6.81;7.49) |

− 1.26 (− 1.6;− 0.91) |

< 0.0001 |

7.42 (6.94;7.9) |

− 0.82 (− 1.3;− 0.34) |

0.0001 | |

| Weight (kg) | T0 |

95.25 (92.11;98.39) |

94.44 (90.37;98.52) |

||||

| T6 |

91.34 (88.17;94.5) |

− 3.92 (− 4.79;-3.05) |

< 0.0001 |

91.8 (87.68;95.92) |

− 2.64 (− 3.81;− 1.48) |

< 0.0001 | |

| T12 |

90.03 (86.72;93.34) |

− 5.22 (− 6.51;− 3.93) |

< 0.0001 |

91.32 (87.02;95.62) |

− 3.13 (− 4.8;-1.45) |

0.0003 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | T0 |

33.77 (32.78;34.77) |

33.11 (31.82;34.4) |

||||

| T6 |

32.34 (31.33;33.34) |

− 1.43 (− 1.74;− 1.13) |

< 0.0001 |

32.11 (30.81;33.42) |

− 1.00 (− 1.4;− 0.59) |

< 0.0001 | |

| T12 |

31.96 (30.9;33.03) |

− 1.81 (− 2.26;− 1.35) |

< 0.0001 |

32.26 (30.88;33.63) |

− 0.85 (− 1.44;− 0.26) |

0.005 | |

| Waist circumference (cm) | T0 |

113.29 (110.62;115.96) |

111.56 (107.75;115.38) |

||||

| T6 |

108.26 (105.56;110.96) |

− 5.03 (− 6.37;− 3.7) |

< 0.0001 |

108.53 (104.64;112.42) |

− 3.03 (− 4.82;− 1.25) |

0.001 | |

| T12 |

107.93 (104.95;110.91) |

− 5.36 (− 7.16;− 3.56) |

< 0.0001 |

109.47 (105.01;113.93) |

− 2.09 (− 4.96;0.77) |

0.15 | |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | T0 |

137.43 (133.82;141.03) |

140.58 (136.07;145.09) |

||||

| T6 |

138.28 (130.95;145.61) |

0.85 (− 7;8.7) |

0.83 |

136.46 (128.00;144.92) |

− 4.12 (− 13.26;5.02) |

0.37 | |

| T12 |

131.77 (123.34;140.19) |

− 5.66 (− 14.51;3.18) |

0.20 |

132.89 (120.62;145.15) |

− 7.69 (− 20.36;4.98) |

0.23 | |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | T0 |

80.07 (78.02;82.13) |

79.72 (77.15;82.3) |

||||

| T6 |

80.51 (76.6;84.42) |

0.43 (− 3.57;4.44) |

0.83 |

77.12 (72.45;81.78) |

− 2.61 (− 7.38;2.17) |

0.28 | |

| T12 |

74.94 (70.51;79.38) |

− 5.13 (− 9.61;− 0.65) |

0.03 |

78.03 (71.69;84.37) |

− 1.69 (− 8.03;4.65) |

0.59 | |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | T0 |

171.18 (163.13;179.23) |

171.5 (161.41;181.59) |

||||

| T6 |

162.32 (152.79;171.86) |

− 8.86 (− 17.09;− 0.63) |

0.04 |

166.8 (155.07;178.52) |

− 4.7 (− 14.37;4.97) |

0.34 | |

| T12 |

157.33 (145.67;168.99) |

− 13.85 (− 24.39;− 3.32) |

0.01 |

162.31 (146.09;178.53) |

− 9.19 (− 23.98;5.61) |

0.22 | |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | T0 |

168.43 (150.84;186.03) |

186.64 (164.54;208.75) |

||||

| T6 |

163.83 (141.7;185.97) |

− 4.6 (− 26.32;17.12) |

0.68 |

153.78 (126.93;180.63) |

− 32.86 (− 58.93;− 6.8) |

0.01 | |

| T12 |

155.76 (127.65;183.88) |

− 12.67 (− 40.33;14.99) |

0.37 |

177.81 (138.12;217.5) |

− 8.83 (− 47.74;30.07) |

0.65 | |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | T0 |

45.14 (43.22;47.06) |

44.28 (41.85;46.71) |

||||

| T6 |

44.38 (42.1;46.66) |

− 0.77 (− 2.68;1.14) |

0.43 |

42.2 (39.45;44.96) |

− 2.07 (− 4.23;0.08) |

0.06 | |

| T12 |

45.37 (42.67;48.07) |

0.22 (− 2.16;2.61) |

0.85 |

45.66 (41.93;49.39) |

1.38 (− 1.93;4.68) |

0.41 | |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | T0 |

90.02 (83.59;96.45) |

89.38 (81.29;97.46) |

||||

| T6 |

83.19 (74.8;91.58) |

− 6.83 (− 14.64;0.99) |

0.087 |

95.38 (85.85;104.91) |

6.00 (− 2.56;14.57) |

0.17 | |

| T12 |

80.37 (70.59;90.14) |

− 9.66 (− 18.92;− 0.39) |

0.04 |

82.55 (68.85;96.25) |

− 6.83 (− 19.66;6) |

0.29 | |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | T0 |

0.94 (0.84;1.04) |

1.05 (0.92;1.18) |

||||

| T6 |

0.95 (0.85;1.06) |

0.01 (− 0.04;0.06) |

0.74 |

1.05 (0.91;1.19) |

0 (− 0.06;0.07) |

0.95 | |

| T12 |

0.95 (0.84;1.07) |

0.01 (− 0.06;0.08) |

0.75 |

1.07 (0.92;1.22) |

0.02 (− 0.07;0.11) |

0.70 | |

| eGFR (ml/min*1.73m2) | T0 |

80.7 (76.82;84.57) |

79.34 (74.33;84.35) |

||||

| T6 |

79.42 (75.1;83.74) |

− 1.28 (− 4.11;1.55) |

0.37 |

78.76 (73.29;84.23) |

− 0.58 (− 4.14;2.98) |

0.75 | |

| T12 |

80.63 (75.77;85.49) |

− 0.07 (− 3.69;3.56) |

0.97 |

78.43 (71.97;84.88) |

− 0.91 (− 5.74;3.92) |

0.71 | |

| Albuminuria (mg/dl) | T0 |

6.79 (3.75;9.82) |

9.93 (6.53;13.33) |

||||

| T6 |

4.88 (0.77;8.99) |

− 1.91 (− 6.65;2.84) |

0.43 |

5.49 (0.86;10.12) |

− 4.44 (− 9.65;0.77) |

0.09 | |

| T12 |

4.9 (− 0.76;10.56) |

− 1.88 (− 7.98;4.21) |

0.54 |

13.48 (6.91;20.04) |

3.54 (− 3.41;10.5) |

0.31 | |

| Semaglutide dose | T0 |

0.25 (0.22;0.29) |

0.57 (0.53;0.62) |

||||

| T6 |

0.82 (0.78;0.86) |

0.57 (0.52;0.61) |

< 0.0001 |

0.96 (0.91;.01) |

0.39 (0.33;0.44) |

< 0.0001 | |

| T12 |

0.86 (0.8;0.91) |

0.60 (0.54;0.67) |

< 0.0001 |

0.96 (0.88;1.03) |

0.38 (0.3;0.47) |

< 0.0001 | |

Changes in estimated mean levels of continuous end points during the follow-up and within-group comparisons (T6 vs. T0 and T12 vs. T0)

*Paired t-test derived from linear mixed models for repeated measurements. Statistically significant p values (p < 0.05) are in bold

Fig. 2.

Effectiveness of semaglutide: results of longitudinal models by treatment group. Changes in estimated mean levels of HbA1c and body weight during the follow-up

In the naïve cohort, after 6 months from semaglutide initiation, levels of HbA1c were significantly reduced by − 1.31% (p < 0.0001) (mean dose of semaglutide was 0.82 mg), and reduction was sustained after 12 months (− 1.26; p = 0.0001) (mean dose 0.86 mg).

All obesity indices were improved after 6 and 12 months: body weight decreased by − 3.92 kg after 6 months (p < 0.0001) and by − 5.22 kg after 12 months (p < 0.0001) (corresponding to a BMI reduction of − 1.43 kg/m2 at 6 months and − 1.81 kg/m2 at 12 months; p < 0.0001 for both comparisons); waist circumference was reduced by − 5 cm after 6 months (p < 0.0001), and the reduction was maintained after 12 months from baseline (p < 0.0001).

In patients already treated with GLP-1RAs, statistically significant improvements in HbA1c and body weight were obtained after 6 and 12 months from semaglutide initiation.

After 6 months, levels of HbA1c were significantly reduced by − 0.78% (p < 0.0001) (mean dose of semaglutide was 0.96 mg), and reduction was sustained after 12 months (− 0.82%; p = 0.0001) (mean dose of semaglutide remained 0.96 mg) (Table 2).

All obesity indices were improved after 6 and 12 months: body weight decreased by − 2.64 kg after 6 months (p < 0.0001) and by − 3.13 kg after 12 months (p = 0.0003) (corresponding to a BMI reduction of –1.00 kg/m2 at 6 months and − 0.85 kg/m2 at 12 months (0.005); waist circumference was reduced by − 3 cm after 6 months (p < 0.0001) (Table 2 and Fig. 2).

Clinically relevant reductions of systolic and diastolic blood pressure mean levels were documented after 12 months from semaglutide initiation in both cohorts, although statistical significance was reached only for diastolic blood pressure in the naïve cohort (Table 2).

Total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol levels also significantly improved in the naïve cohort during 12 months, while the reduction in triglyceride levels was statistically significant at 6 months in the switcher cohort (Table 2).

No changes were documented in renal function (Table 2).

In terms of categorical end points, HbA1c levels < 7% were reached by 52% of naive patients and 31% of switchers and weight loss > 5% by 46.9% of naive patients and 25.9% of switchers.

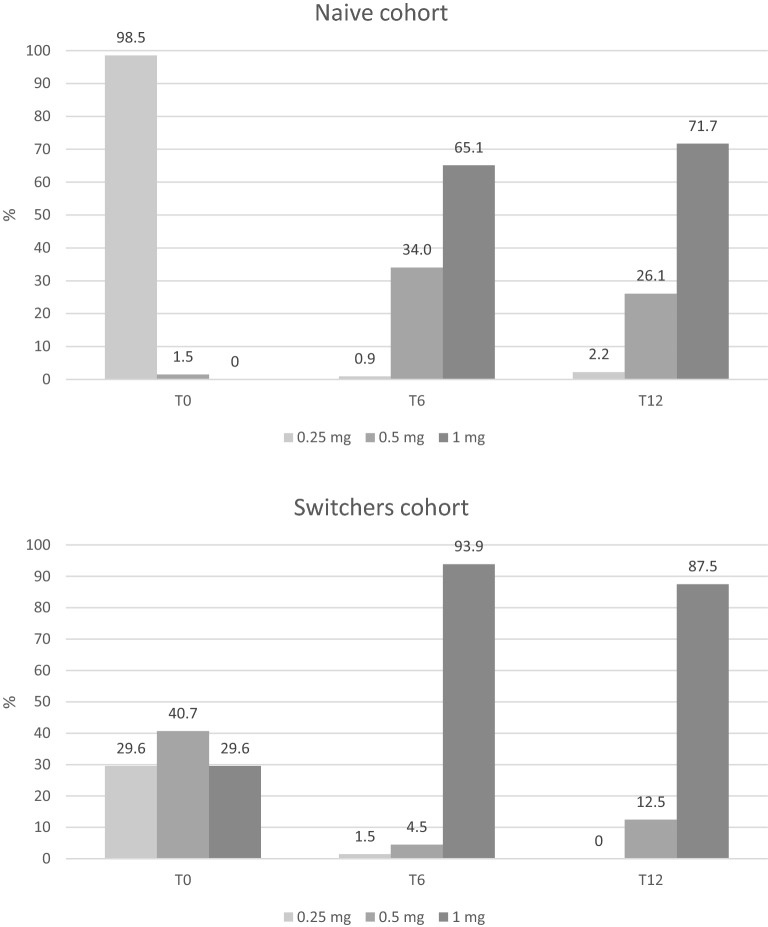

Semaglutide s.c. dosing

Dose of semaglutide was titrated during 12 months. In the naïve cohort, almost all patients started with 0.25 mg. After 6 months, 65.1% of patients were treated with 1 mg and after 12 months 71.7% were treated with the maximum dose of 1 mg. In the switcher cohort, the initial dose of semaglutide was 0.5 mg in 40.7% of cases, but also the other two doses were frequently adopted. After 6 and 12 months, most patients was prescribed the maximum dose of 1 mg (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Dosing of semaglutide during follow-up by cohort

Safety

Patients discontinuing semaglutide during the 12 months were a small minority (N = 14, 6.5%). Mean time to discontinuation was 4.3 ± 3.6 months; in 6 out of 14 patients, the reason for discontinuation was the occurrence of gastrointestinal side effects; in the other cases, the interruption was due to patient decision or need for therapy intensification.

No severe hypoglycemia occurred.

Discussion

This study confirms the effectiveness and tolerability of semaglutide s.c. in real-world clinical practice, without any new safety concerns.

Results show relevant reductions in HbA1c and obesity indices and additional benefits in cardiovascular risk factors, in both cohorts of naïve patients and switchers from another GLP-1RA.

The study documented the generalizability of the benefits obtained in the SUSTAIN program [10–17] to the real-world setting. In the SUSTAIN program, HbA1c was reduced from 1.1 to 1.5% with semaglutide 0.5 mg and from 1.4 to 1.8% with semaglutide 1 mg; weight was reduced from 3.5 to 4.6 kg with semaglutide 0.5 mg and from 4.5 to 6.5% with semaglutide 1 mg. In the present study, after 6 months, in the naïve cohort, 34% of patients were treated with 0.5 mg and 65% with 1 mg; HbA1c and weight decreased by 1.3% and 3.9 kg, respectively.

The study also documented that semaglutide can be used in a wide range of people with T2D, irrespective of age, diabetes duration, previous use of GLP-1RAs, and background glucose-lowering treatment, supporting its use not only in patients with recent T2D diagnosis, but also in more advanced stages of the disease, such as patients already treated with insulin. Furthermore, in the study population the proportion of patients with established CV disease was lower than in CV outcome trials (CVOTs) [20]; in fact, among patients initiating semaglutide under routine clinical practice, from 1/4 to 1/3 of patients had a history of CV events.

As expected, more marked improvements in HbA1c and weight were obtained in naïve patients, but it is noteworthy that further improvements were obtained in patients already treated with GLP-1RAs. Existing data suggest that semaglutide can be more effective than other GLP-1RAs, while the safety profile does not differ from that reported with other GLP-1RAs [21]. The reason why semaglutide is more effective than the other GLP-1RAs is still to be clarified, but it seems to be related to its molecular properties. The high constant level of the drug may contribute to receptor activation and full dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) protection. The weight effect is believed to be exerted via receptors in the central nervous system through a facilitated entry into additional regions of the nervous system due to the molecular structure of semaglutide [22].

GLP-1RAs demonstrated additional benefits on CV risk factors such as blood pressure reduction and improvement of dyslipidemia [23]. In line with available literature, even this study showed a trend of improvement in CV risk factors, although statistical significance was reached only in some cases. A recent expert opinion of the Italian Diabetes Society underlined that GLP-1RAs possess properties useful to treat not only hyperglycemia, but also additional conditions such as CV risk factors and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease [6].

Study results are consistent with real-world studies conducted in other countries. In Canada, a study based on the retrospective analysis of a diabetes registry (SPARE study) on 937 naïve patients documented a statistically significant mean reduction in HbA1c of − 1.03 and in weight of − 3.9 kg, with no significant change in self-reported incidence of hypoglycemia [24]. Another real-world Canadian study (REALIZE-DM, N = 164) documented that in patients switching from another GLP-RA (liraglutide or dulaglutide), semaglutide allowed achieving further reductions in HbA1c (− 0.65% after 6 months) and weight (− 1.69 kg) [25].

In the US, the EXPERT study based on the use of EMRs showed that switching to injectable semaglutide from any other GLP-1RA was associated with significant improvements in HbA1c (N = 710) at 6 months (− 0.7%) and sustained at 12 months; weight reductions (N = 921) were also significant at 6 months (− 2.1 kg) and greater at 12 months (− 2.8 kg) [26]. In addition, data from the US Commercially Insured and Medicare Advantage Population (N = 1888) showed that naïve patients obtained a reduction in HbA1c two times larger than that of switchers (− 1.2% vs. 0.6%); additionally, among the subgroup of patients with a baseline HbA1c value > 9% (75 mmol/mol), percentage point changes in HbA1c were − 2.2% (− 24.0 mmol/mol) [27]. Another US retrospective study using Optum's de-identified Clinformatics® Data Mart Database assessed that persistence at 360 days was significantly greater with semaglutide (67%) than for comparators (dulaglutide 56%, liraglutide 40%, and exenatide QW 35.5%), while adherence was comparable or greater [28].

In Europe, as part of the SURE observational prospective study, in the SURE Denmark/Sweden cohort (N = 331), use of semaglutide was associated with HbA1c reduction of − 1.2% and weight loss of − 5.4 kg; furthermore, at the end of study, 67.5% of patients achieved HbA1c < 7%, whereas 49.4% achieved a weight reduction of ≥ 5% [29]. In the SURE Switzerland cohort (N = 214), HbA1c was reduced by − 0.8%, weight by − 5.0 kg, and waist circumference by − 4.8 cm [30]. Moreover, real-world data from a diabetes outpatient clinic in Denmark (N = 119) showed that in people with T2D on a broad range of glucose-lowering treatments, effects of semaglutide once weekly on HbA1c and body weight were comparable to the effects observed in clinical studies, but with fewer persons receiving the maximum dose of semaglutide [31]. Finally, in a retrospective evaluation of 189 patients in Wales, HbA1c was reduced by 1.5% and weight by 3 kg after 6 months [32].

Semaglutide was generally well tolerated, and no new safety signals were identified in these real-world studies.

The recent demonstration of pronounced effects on HbA1c and body weight and the positive CV effects of semaglutide in reducing the MACE risk [16] is extremely encouraging in relation to the clinical use of this drug. Further studies are needed to assess long-term effectiveness and safety of semaglutide and its impact on additional end points (e.g., fatty liver index). In addition, after the recent results of the PIONEER program [33, 34], oral semaglutide was approved as the first oral GLP-1RA for the treatment of T2DM, enlarging the possibility of use of the drug in patients who are unable or unwilling to self-administer an injectable agent.

The study has strengths and limitations. The main strength was that this is the first Italian study documenting the real-world impact of semaglutide. Another strength is that the COVID-19 pandemic only partly limited data collection during follow-up. Among limitations, small sample size, retrospective design, lack of 12-month follow-up data for a substantial proportion of patients, and lack of data on fasting blood glucose, side effects, and mild hypoglycemia can be mentioned.

Conclusion

In conclusion, semaglutide s.c. was associated with significant glycemic and weight-loss benefits in adults with T2D, supporting its real-world use in all stages of the diabetes disease. Not only naïve patients, but also patients already treated with insulin or switching from other GLP-1RAs benefitted from the treatment, suggesting that semaglutide is currently the most powerful in the GLP-1RA class, and it is never too late to consider it.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the whole staff of participating centers and all the collaborators.

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received by the authors for this study. The journal’s Rapid Service Fee was provided by CORESEARCH SRL (Maria Chiara Rossi, Giusi Graziano) through a Novo Nordisk S.p.A. unconditional grant.

Medical Writing and/or Editorial Assistance

Editorial assistance was provided by CORESEARCH SRL (Maria Chiara Rossi, Giusi Graziano) through a Novo Nordisk S.p.A. unconditional grant. The authors of the publication are fully responsible for the contents and conclusions. Novo Nordisk S.p.A. did not influence and has not been involved in the data interpretation presented in the manuscript.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Author Contributions

Chiara Di Loreto, Giovanni Nasini and Viviana Minarelli contributed to the study concept and design of data. Chiara Di Loreto, Roberto Norgiolini and Paola Del Sindaco contributed to drafting of the manuscript, interpretation of data, statistical analysis, and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Chiara Di Loreto, Giovanni Nasini, and Viviana Minarelli contributed to acquisition of data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Chiara Di Loreto is the guarantor of this work and, as such, has full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Disclosures

Chiara Di Loreto has received consultation fees and speaker honoraria from Novonordisk, Lilly, and Mundipharma. Giovanni Nasini, Roberto Norgiolini, Viviana Minarelli, and Paola Del Sindaco have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. The study protocol was approved by the regional the ethics committee of all the participating centers (Umbria Regional Ethics Committee, approval no. 20338/20/ON-November 30, 2020). Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1.Sun H, Saeedi P, Karuranga S, Pinkepank M, Ogurtsova K, Duncan BB, Stein C, Basit A, Chan JCN, Mbanya JC, Pavkov ME, Ramachandaran A, Wild SH, James S, Herman WH, Zhang P, Bommer C, Kuo S, Boyko EJ, Magliano DJ. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2021 Nov 24:109119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Buse JB, Wexler DJ, Tsapas A, Rossing P, Mingrone G, Mathieu C, D'Alessio DA, Davies MJ. 2019 Update to: Management of Hyperglycemia in Type 2 Diabetes, 2018. A Consensus Report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care. 2020;43(2):487–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.American Diabetes Association. 9. Pharmacologic Approaches to Glycemic Treatment: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2021. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(Suppl 1):S111-S124. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Linea Guida della Società Italiana di Diabetologia (SID) e dell’Associazione dei Medici Diabetologi (AMD). La terapia del diabete mellito di tipo 2. SISTEMA NAZIONALE LINEE GUIDA DELL’ISTITUTO SUPERIORE DI SANITÀ 26/07/21. https://www.siditalia.it/pdf/LG_379_diabete_2_sid_amd.pdf [last accessed 12 november 2021]

- 5.Vilsbøll T. Liraglutide: a once-daily GLP-1 analogue for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2007;16:231–237. doi: 10.1517/13543784.16.2.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Napoli R. Avogaro A. Formoso G., Piro S., Purrello S., Targher G. Beneficial Effects of Glucagon-Like Peptide 1 Receptor Agonists on Glucose Control, Cardiovascular Risk Profile, and Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. An Expert Opinion of the Italian Diabetes Society. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2021;21:S0939–4753(21)00410–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Kalra S, Sahay R. A Review on Semaglutide: An Oral Glucagon-Like Peptide 1 Receptor Agonist in Management of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Ther. 2020;11:1965–82- [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Lau J, Bloch P, Schäffer L, Pettersson I, Spetzler J, Kofoed J, Madsen K, Knudsen LB, McGuire J, Steensgaard DB, Strauss HM, Gram DX, Knudsen SM, Nielsen FS, Thygesen P, Reedtz-Runge S, Kruse T. Discovery of the once-weekly glucagon-like peptide (GLP-1) analogue semaglutide. J Med Chem. 2015;58:7370–7380. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rea F, Ciardullo S, Savaré L, Perseghin G, Corrao G. Comparing medication persistence among patients with type 2 diabetes using sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors or glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists in real-world setting. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2021;180:109035. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Sorli C, Harashima SI, Tsoukas GM, Unger J, Karsbøl JD, Hansen T, Bain SC. Efficacy and safety of onceweekly semaglutide monotherapy versus placebo in patients with type 2 diabetes (sustain 1): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, multinational, multicentre phase 3A trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5:251–260. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30013-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahrén B, Masmiquel L, Kumar H, Sargin M, Karsbøl JD, Jacobsen SH, Chow F. Efficacy and safety of onceweekly semaglutide versus once-daily sitagliptin as an add-on to metformin, thiazolidinediones, or both, in patients with type 2 diabetes (sustain 2): a 56-week, double-blind, phase 3A, randomised trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5:341–354. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30092-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahmann AJ, Capehorn M, Charpentier G, Dotta F, Henkel E, Lingvay I, Holst AG, Annett MP, Aroda VR. Efficacy and safety of once-weekly Semaglutide versus exenatide ER in subjects with type 2 diabetes (sustain 3): a 56-Week, open-label, randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:258–266. doi: 10.2337/dc17-0417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aroda VR, Bain SC, Cariou B, Piletič M, Rose L, Axelsen M, Rowe E, DeVries JH. Efficacy and safety of once-weekly semaglutide versus once-daily insulin glargine as add-on to metformin (with or without sulfonylureas) in insulin-naive patients with type 2 diabetes (sustain 4): a randomised, open-label, parallel-group, multicentre, multinational, phase 3A trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5:355–366. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30085-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rodbard HW, Lingvay I, Reed J, de la Rosa R, Rose L, Sugimoto D, Araki E, Chu PL, Wijayasinghe N, Norwood P. Semaglutide added to basal insulin in type 2 diabetes (sustain 5): a randomised, controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol. 2018;1103:2291–2301. doi: 10.1210/jc.2018-00070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pratley RE, Aroda VR, Lingvay I, Lüdemann J, Andreassen C, Navarria A, Viljoen A; SUSTAIN 7 investigators. Semaglutide versus dulaglutide Once Weekly in patients with type 2 diabetes (sustain 7): a randomised, open-label, phase 3B trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;6:275–86. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Marso SP, Bain SC, Consoli A, Eliaschewitz FG, Jódar E, Leiter LA, Lingvay I, Rosenstock J, Seufert J, Warren ML, Woo V, Hansen O, Holst AG, Pettersson J, Vilsbøll T; SUSTAIN-6 Investigators. Semaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1834–44. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Ahmann A, Chow F, Vivian F, et al. Semaglutide provides superior glycemic control across SUSTAIN 1–5 clinical trials. Int J Nutrol. 2018;11(S 01):Trab722.

- 18.Seeger JD, Nunes A, Loughlin AM. Using RWE research to extend clinical trials in diabetes: An example with implications for the future. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2020;22(Suppl 3):35–44. doi: 10.1111/dom.14021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berger ML, Sox H, Willke RJ, Brixner DL, Eichler HG, Goettsch W, Madigan D, Makady A, Schneeweiss S, Tarricone R, Wang SV, Watkins J, Daniel MC. Good practices for real-world data studies of treatment and/or comparative effectiveness: Recommendations from the joint ISPOR-ISPE Special Task Force on real-world evidence in health care decision making. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2017;26:1033–1039. doi: 10.1002/pds.4297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nreu B, Dicembrini I, Tinti F, Sesti G, Mannucci E, Monami M. Major cardiovascular events, heart failure, and atrial fibrillation in patients treated with glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists: An updated meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2020;30:1106–1114. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2020.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holst JJ, Madsbad S. Semaglutide seems to be more effective the other GLP-1Ras. Ann Transl Med. 2017;5:505. doi: 10.21037/atm.2017.11.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Secher A, Jelsing J, Baquero AF, Hecksher-Sørensen J, Cowley MA, Dalbøge LS, Hansen G, Grove KL, Pyke C, Raun K, Schäffer L, Tang-Christensen M, Verma S, Witgen BM, Vrang N, Bjerre KL. The arcuate nucleus mediates GLP-1 receptor agonist liraglutide-dependent weight loss. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:4473–4488. doi: 10.1172/JCI75276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iorga RA, Bacalbasa N, Carsote M, Bratu OG, Stanescu AMA, Bungau S, Pantis C, Diaconu CC. Metabolic and cardiovascular benefits of GLP-1 agonists, besides the hypoglycemic effect (Review) Exp Ther Med. 2020;20:2396–2400. doi: 10.3892/etm.2020.8714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown RE, Bech PG, Aronson R. Semaglutide once weekly in people with type 2 diabetes: Real-world analysis of the Canadian LMC diabetes registry (SPARE study) Diabetes Obes Metab. 2020;22:2013–2020. doi: 10.1111/dom.14117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Effectiveness Analysis of Switching From Liraglutide or Dulaglutide to Semaglutide in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: The Retrospective REALISE-DM Study. Diabetes Ther. 2021;12:527–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Lingvay I, Kirk AR, Lophaven S, Wolden ML, Shubrook JH. Outcomes in GLP-1 RA-Experienced Patients Switching to Once-Weekly Semaglutide in a Real-World Setting: The Retrospective. Observational EXPERT Study Diabetes Ther. 2021;12:879–896. doi: 10.1007/s13300-021-01010-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Visaria J, Uzoigwe C, Swift C, Dang-Tan T, Paprocki Y, Willey VJ. Real-World Effectiveness of Once-Weekly Semaglutide From a US Commercially Insured and Medicare Advantage Population. Clin Ther Clin Ther. 2021;43:808–821. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2021.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Uzoigwe C, Liang Y, Whitmire S, Paprocki Y. Semaglutide Once-Weekly Persistence and Adherence Versus Other GLP-1 RAs in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes in a US Real-World Setting. Diabetes Ther. 2021;12:1475–1489. doi: 10.1007/s13300-021-01053-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rajamand Ekberg N, Bodholdt U, Catarig AM, Catrina SB, Grau K, Holmberg CN, Klanger B, Knudsen ST. Real-world use of once-weekly semaglutide in patients with type 2 diabetes: Results from the SURE Denmark/Sweden multicentre, prospective, observational study. Prim Care Diabetes. 2021;15:871–878. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2021.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rudofsky G, Catarig AM, Favre L, Grau K, Häfliger S, Thomann R, Schultes B. Real-world use of once-weekly semaglutide in patients with type 2 diabetes: Results from the SURE Switzerland multicentre, prospective, observational study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2021;178:108931. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Hansen KB, Svendstrup M, Lund A, Knop FK, Vilsbøll T, Vestergaard H. Once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide treatment for persons with type 2 diabetes: real-world data from a diabetes out-patient clinic. Diabet Med. Diabet Med. 2021;38:e14655. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Williams DM, Ruslan AM, Khan R, Vijayasingam D, Iqbal F, Shaikh A, Lim J, Chudleigh R, Peter R, Udiawar M, Bain SC, Stephens JW, Min T. Real-world clinical experience of semaglutide in secondary care diabetes: a retrospective observational study. Diabetes Ther. 2021;12:801–811. doi: 10.1007/s13300-021-01015-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rodbard HW, Dougherty T, Taddei-Allen P. Efficacy of oral semaglutide: overview of the PIONEER clinical trial program and implications for managed care. Am J Manag Care. 2020;26(16 Suppl):S335–S343. doi: 10.37765/ajmc.2020.88554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thethi TK, Pratley R, Meier JJ. Efficacy, safety and cardiovascular outcomes of once-daily oral semaglutide in patients with type 2 diabetes: The PIONEER programme. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2020;22:1263–1277. doi: 10.1111/dom.14054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.