Key Points

Question

Is the COVID-19 pandemic associated with changes in mortality among older adults with Alzheimer disease and related dementias (ADRD)?

Findings

In this cross-sectional study of 53 640 888 Medicare enrollees 65 years of age or older, compared with 2019, mortality was 12% higher among beneficiaries without ADRD and 26% higher among beneficiaries with ADRD in 2020. Among nursing home residents without ADRD, mortality was 24% higher, and among nursing home residents with ADRD, mortality was 33% higher.

Meaning

These findings suggest that the COVID-19 pandemic was associated with increased mortality among older Medicare enrollees with ADRD, especially among beneficiaries living in nursing homes.

Abstract

Importance

The COVID-19 pandemic fundamentally altered the delivery of health care in the United States. The associations between these COVID-19–related changes and outcomes in vulnerable patients, such as among persons with Alzheimer disease and related dementias (ADRD), are not yet well understood.

Objective

To determine the association between regional rates of COVID-19 infection and excess mortality among individuals with ADRD.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This retrospective cross-sectional study used data from beneficiaries of 100% fee-for-service Medicare Parts A and B between January 1, 2019, and December 31, 2020, to assess age- and sex-adjusted mortality rates. Participants were 53 640 888 Medicare enrollees 65 years of age or older categorized into 4 prespecified cohorts: enrollees with or without ADRD and enrollees with or without ADRD residing in nursing homes.

Exposures

Monthly COVID-19 infection rates by hospital referral region between January and December 2020.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Mortality rates from March through December 2020 were compared with those from March through December 2019. Excess mortality was calculated by comparing mortality rates in 2020 with rates in 2019 for specific, predetermined groups. Means were compared using t tests, and 95% CIs were estimated using the delta method.

Results

This cross-sectional study included 26 952 752 Medicare enrollees in 2019 and 26 688 136 enrollees in 2020. In 2019, the mean (SD) age of community-dwelling beneficiaries without ADRD was 74.1 (8.8) years and with ADRD was 82.6 (8.4) years. The mean (SD) age of nursing home residents with ADRD (83.6 [8.4] years) was similar to that for patients without ADRD (79.7 [8.8] years). Among patients diagnosed as having ADRD in 2019, 63.5% were women, 2.7% were Asian, 9.2% were Black, 5.7% were Hispanic, 80.7% were White, and 1.7% were identified as other (included all races or ethnicities other than those given); the composition did not change appreciably in 2020. Compared with 2019, adjusted mortality in 2020 was 12.4% (95% CI, 12.1%-12.6%) higher among enrollees without ADRD and 25.7% (95% CI, 25.3%-26.2%) higher among all enrollees with ADRD, with even higher percentages for Asian (36.0%; 95% CI, 32.6%-39.3%), Black (36.7%; 95% CI, 35.2%-38.2%), and Hispanic (40.1%; 95% CI, 37.9%-42.3%) populations with ADRD. The hospital referral region in the lowest quintile for COVID-19 infections in 2020 had no excess mortality among enrollees without ADRD but 8.8% (95% CI, 7.5%-10.2%) higher mortality among community-dwelling enrollees with ADRD and 14.2% (95% CI, 12.2%-16.2%) higher mortality among enrollees with ADRD living in nursing homes.

Conclusions and Relevance

The results of this cross-sectional study suggest that the COVID-19 pandemic may be associated with excess mortality among older adults with ADRD, especially for Asian, Black, and Hispanic populations and people living in nursing homes, even in areas with low COVID-19 prevalence.

This cross-sectional study uses data from 53.6 million Medicare beneficiaries to assess whether there is an association between regional rates of COVID-19 infection and excess mortality among older adults with or without Alzheimer disease and related dementias residing in the community or nursing homes.

Introduction

In 2020, COVID-19 abruptly altered the delivery of health care and the daily operations of nursing facilities.1 Changes in health care delivery included a decrease in inpatient care2,3 and a transition of outpatient care to telehealth platforms.4 Changes in nursing facility operations included lockdowns and strict visitation procedures, resulting in social isolation for many residents.5,6,7 The association between those secondary changes related to the pandemic and patient outcomes, especially among vulnerable populations, has not been well described.

Excess mortality, which captures population-level increases in mortality due to COVID-19 and COVID-19–related changes in society,8,9 is an appropriate measure of both direct and indirect effects of the pandemic. The aim of this study was to explore the association between COVID-19–related changes and the outcomes of vulnerable patients, such as those with Alzheimer disease and related dementias (ADRD), and underserved populations.

Methods

This cross-sectional study used data from beneficiaries of 100% fee-for-service Medicare Parts A and B between January 1, 2019, and December 31, 2020 (eAppendix 1 in the Supplement). Demographic information was obtained from the Master Beneficiary Summary File base. In Medicare claims, race is determined using self-reported Social Security Administration data.10 To improve the accuracy of our race and ethnicity data, we used the Research Triangle Institute algorithm to identify more enrollees as Asian or Hispanic. This algorithm takes the beneficiary race code historically used by the Social Security Administration and applies an algorithm based on first and last names likely to be of Hispanic or Asian origin.11 Small sample sizes precluded analysis for other racial and ethnic identities. This study is compliant with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines for cross-sectional studies. This research was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Bureau of Economic Research Human Subjects Committee, which also waived the requirement for obtaining informed consent because there was no direct contact with patients and only deidentified claims data were used in the analyses.

The ADRD cohort was determined using the Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse (CCW) algorithms for the calendar year (eAppendix 1 in the Supplement); similar cohorts have been shown to have a sensitivity of 0.85 and specificity of 0.89 compared with clinically diagnosed dementia.12 We also used the CCW algorithm to measure 3 relevant chronic conditions associated with poorer outcomes in the setting of COVID-19 infection: heart failure, diabetes, and lung cancer.13,14 Nursing home residence was determined using place of service and Current Procedural Terminology codes from the carrier (physician) and outpatient files to identify enrollees with any nursing facility–related services in each month.15 If the beneficiary had 1 or more nursing facility–related place of service or Current Procedural Terminology codes in the relevant period, the beneficiary was classified as a nursing home resident. For each period, 4 cohorts were created: (1) patients with ADRD, (2) patients without ADRD; (3) patients with ADRD residing in nursing facilities; and (4) patients without ADRD residing in nursing facilities.

Mortality rates were calculated at the national level for each of the 4 cohorts, by race and ethnicity, for March through December 2019 and for March through December 2020. Excess mortality was defined as the ratio of mortality in the 2020 period relative to the corresponding period in 2019 (or, equivalently, the percentage by which the mortality rate of 2020 exceeded that of 2019). We calculated excess mortality for the cohorts with or without ADRD for each of the 306 hospital referral regions (HRRs) in the US, for both earlier (March-July 2020) and later (August-December 2020) periods (eAppendix 2 in the Supplement). By using largely overlapping populations during 2019 and 2020 within each HRR, we implicitly adjusted for underlying initial health conditions and other potential confounders.

Because patients with ADRD and nursing home residents were older than the general Medicare population, we adjusted for sex and age and applied population weights for the reference population (patients with ADRD) to populations without ADRD. We did not adjust excess mortality rates by race or ethnicity to ensure that the true burden of COVID-19 in regions such as New Orleans or the Bronx was reflected in our estimates rather than being attenuated by the application of national risk-adjustment weights.16

Statistical Analysis

Using the daily COVID-19 infection rates per HRR obtained from The New York Times,17 we also created population-weighted quintiles of COVID-19 infection rates per 100 000 population to consider excess mortality by quintile of exposure for the cohorts with or without ADRD during the first and second waves of the pandemic (eAppendix 3 in the Supplement). We then used box and whisker plots to show the variability of HRR-level ADRD excess mortality in HRRs with sample sizes of at least 5000 patients with ADRD. We also performed a trend test (2012-2018) for differences in region-specific mortality rates across quintiles of COVID-19 exposure (eAppendix 2 in the Supplement).

Means were compared using t tests, and 95% CIs were estimated using the delta method (eAppendix 2 in the Supplement).18 Statistical significance was defined as a 2-sided P < .05. All data were analyzed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

We compared mortality rates for 26 952 752 Medicare enrollees in March through December 2019 with rates for 26 688 136 enrollees in March through December 2020. As shown in Table 1, 2 412 124 enrollees (8.9% of the total) were diagnosed as having ADRD in 2019, and 2 308 234 enrollees (8.6% of the total) in 2020. During 2020 the nursing home population decreased by 18.7%. In 2019, the mean (SD) age of community-dwelling beneficiaries without ADRD was 74.1 (8.8) years, whereas the mean (SD) age of community-dwelling beneficiaries with ADRD was 82.6 (8.4) years. For nursing home residents, the mean (SD) age for patients with ADRD (83.6 [8.4] years) was similar to that for patients without ADRD (79.7 [8.8] years) (eAppendix 4 in the Supplement). Among patients diagnosed as having ADRD in 2019, 63.5% were women, 36.5% were men, 2.7% were Asian, 9.2% were Black, 5.7% were Hispanic, and 80.7% were White; the composition did not change appreciably in 2020. In 2019, the rates of Medicaid dual eligibility were substantially higher in the population with ADRD (25.8%) compared with the population without ADRD (9.6%), as were rates of lung disease (30.2% vs 18.2%), diabetes (33.9% vs 22.9%), and heart failure (50.8% vs 25.3%).

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of Medicare Enrollees With or Without ADRD, 2019 vs 2020.

| Characteristic | With ADRD, % | P value 2019 vs 2020 | Without ADRD, % | P value 2019 vs 2020 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 2020 | 2019 | 2020 | |||

| All enrollees, No. | 2 412 124 | 2 308 234 | 24 540 628 | 24 379 902 | ||

| Nursing home residents, No.a | 1 074 880 | 934 454 | 871 865 | 647 346 | ||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 82.6 (8.4) | 82.3 (8.5) | <.001 | 74.1 (8.8) | 74.0 (9.0) | <.001 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 63.5 | 62.6 | <.001 | 55.1 | 55.0 | <.001 |

| Male | 36.5 | 37.4 | <.001 | 44.9 | 45.0 | <.001 |

| Race and ethnicity | ||||||

| Asian | 2.7 | 2.9 | <.001 | 2.8 | 2.9 | <.001 |

| Black | 9.2 | 9.1 | <.001 | 6.7 | 6.5 | <.001 |

| Hispanic | 5.7 | 5.8 | <.001 | 4.9 | 4.9 | <.001 |

| White | 80.7 | 80.3 | <.001 | 82.2 | 82.2 | <.001 |

| Otherb | 1.7 | 1.9 | <.001 | 3.3 | 3.5 | <.001 |

| Medicaid recipient | 25.8 | 25.0 | <.001 | 9.6 | 8.9 | <.001 |

| End-stage kidney disease | 1.6 | 1.70 | <.001 | 0.7 | 0.7 | <.001 |

| Nursing home resident | 44.6 | 40.5 | <.001 | 3.6 | 3.9 | <.001 |

| Chronic conditionc | ||||||

| Lung disease | 30.2 | 35.3 | <.001 | 18.2 | 21.4 | <.001 |

| Diabetes | 33.9 | 37.6 | <.001 | 22.9 | 24.6 | <.001 |

| Heart failure | 50.8 | 57.0 | <.001 | 25.3 | 28.7 | <.001 |

Abbreviation: ADRD, Alzheimer disease and related dementias.

Baseline characteristic comparison for patients with or without ADRD living in nursing homes is provided in eAppendix 4 in the Supplement.

Other race or ethnicity includes all races or ethnicities other than those given.

Algorithms for determining chronic conditions were based on the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse algorithm for that calendar year.

Excess mortality for the Medicare enrollees without ADRD adjusted for age and sex was 1.124, or 12.4% higher in 2020 than in 2019 (95% CI, 12.1%-12.6%); for patients with ADRD, mortality was 25.7% higher (95% CI, 25.3%-26.2%). Thus, patients with ADRD experienced a 13.3% greater mortality risk than patients without ADRD from March through December 2020 (Table 2). Among nursing home residents without ADRD, adjusted excess mortality was 1.242, or 24.2% higher (95% CI, 23.4%-25.0%) in 2020 than in 2019. For nursing home residents with ADRD, excess mortality was 1.334, or 33.4% (95% CI, 32.8%-34.0%) higher in 2020 than in 2019.

Table 2. Crude and Risk-Adjusted Mortality for Medicare Enrollees With or Without ADRD Between March and December 2019 and March and December 2020.

| Variable | With ADRD, % | 2020/2019 ADRD excess mortality (95% CI)a | Without ADRD, % | 2020/2019 Without ADRD excess mortality (95% CI)a | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 2020 | 2019 | 2020 | |||

| Overall crude and adjusted mortality rates | ||||||

| Crude mortality | 19.2 | 24.2 | 1.26 (1.25-1.26) | 2.3 | 2.6 | 1.14 (1.13-1.14) |

| Adjusted mortality | 19.6 | 24.6 | 1.26 (1.25-1.26) | 4.2 | 4.7 | 1.12 (1.12-1.13) |

| Nursing home residents crude and adjusted mortality rates | ||||||

| Crude mortality | 24.8 | 32.9 | 1.33 (1.32-1.33) | 15.6 | 19.5 | 1.25 (1.24-1.26) |

| Adjusted mortality | 24.8 | 33.0 | 1.33 (1.33-1.34) | 16.6 | 20.6 | 1.24 (1.23-1.25) |

| Demographic subgroups adjusted mortality rates | ||||||

| Men | 21.6 | 27.2 | 1.26 (1.25-1.26) | 4.6 | 5.3 | 1.15 (1.14-1.13) |

| Women | 18.4 | 23.1 | 1.26 (1.25-1.26) | 4.0 | 4.4 | 1.11 (1.10-1.11) |

| Asian population | 14.2 | 19.4 | 1.36 (1.33-1.39) | 3.1 | 3.8 | 1.21 (1.19-1.23) |

| Black population | 19.4 | 26.6 | 1.37 (1.35-1.38) | 4.0 | 5.3 | 1.31 (1.30-1.32) |

| Hispanic population | 16.4 | 23.0 | 1.40 (1.38-1.42) | 3.8 | 5.0 | 1.32 (1.30-1.34) |

Abbreviation: ADRD, Alzheimer disease and related dementias.

Excess mortality is the ratio of the mortality rate in 2020 divided by the mortality rate in 2019 for a given group.

In stratified analysis, excess mortality in the population with ADRD was similar for women (25.9% excess mortality; 95% CI, 25.2%-26.3%) and men (25.9%; 95% CI, 25.2%-26.5%). Excess mortality was larger in magnitude for Asian (36.0% excess mortality; 95% CI, 32.6%-39.3%), Black (36.7% excess mortality; 95% CI, 35.2%-38.2%), and Hispanic (40.1% excess mortality; 95% CI, 37.9%-42.3%) populations; a similar pattern of elevated mortality risk was observed among enrollees without ADRD.

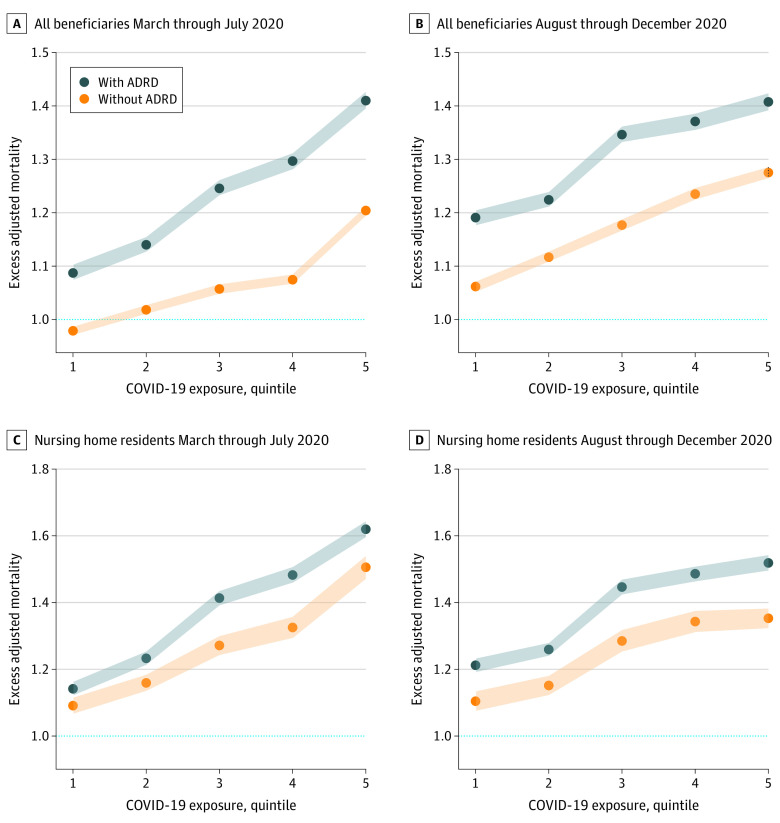

We next considered excess mortality in populations with or without ADRD stratified by quintiles of COVID-19 infection rates for early (March-July) and later (August-December) periods of 2020. Figure 1 shows the monotonicity of increasing excess mortality across increasing quintiles of COVID-19 infection during both the first (March-July) and second waves (August-December) of the pandemic. In each quintile, excess mortality was higher in the population with ADRD than in the population without ADRD. Between March and July 2020, in the lowest quintile for COVID-19 infections, excess mortality was estimated to be −2.1% (95% CI, −2.9% to −1.4%) (Figure 1A). The magnitude of this decrease is roughly similar to the mean annual mortality decrease from 2012 through 2018 (eAppendix 2 in the Supplement). By contrast, for patients with ADRD in the same lowest quintile regions, mortality was 8.8% higher (95% CI, 7.5%-10.2%) (Figure 1A), and for nursing home residents with ADRD also in the lowest quintile regions, mortality was 14.2% higher (95% CI, 12.2%-16.2%) (Figure 1C).

Figure 1. Excess Deaths for Medicare Enrollees With or Without Alzheimer Disease and Related Dementias (ADRD) Between March and July and Between August and December 2020, by Quintile of Community COVID-19 Exposure.

A and B, Excess adjusted mortality for all enrollees. C and D, Excess adjusted mortality for nursing home residents. Excess mortality rates higher than 1.0 (horizontal line) indicate mortality higher in 2020 relative to 2019. Quintile 1 includes hospital referral regions with the lowest rates of COVID-19 infection; quintile 5, the highest rates of COVID-19 infection. All excess death rates are adjusted for age and sex. Quintiles of regional COVID-19 exposure are based on county-level data aggregated to hospital referral regions obtained from The New York Times.17 The shaded areas indicate 95% CIs.

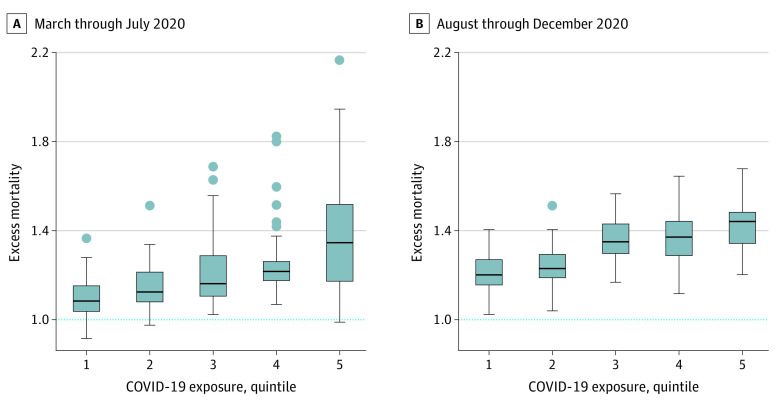

The variability in excess mortality among patients with ADRD across quintiles of COVID-19 exposure is shown in Figure 2. Mortality rates for patients with ADRD in Ridgewood, New Jersey, increased by 104.4%, whereas in the Bronx, New York, mortality was 110.1% higher; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (62% increase in mortality), was also an outlier for high excess mortality, even though the Philadelphia HRR overall was just in the third quintile for COVID-19 infections. Although in general, there was a 3-fold or more increase in the rates of COVID-19 diagnosis between the early and later periods of 2020 across all quintiles (eAppendix 3 in the Supplement), rates of excess mortality in the population with ADRD did not increase for all quintiles of COVID-19 exposure.

Figure 2. Variation in Excess Mortality Among Enrollees With Alzheimer Disease and Related Dementias (ADRD) by COVID-19 Quintile in March Through July (First Wave) and in August Through December (Second Wave) 2020.

Box and whisker plots showing the wide variation in ADRD excess mortality across hospital referral regions, even in regions with similar levels of community infection. To reduce statistical noise, hospital referral regions are limited to those with at least 5000 beneficiaries with ADRD in 2019 and 2020. Variability is highest in the first wave of the pandemic, with the Bronx, New York (excess mortality, 2.17), Newark, New Jersey (1.95), and Ridgewood, New Jersey (1.91), exhibiting the highest rates in the ADRD population. The x-axis represents quintiles of COVID-19 infection rates. The lower border of the box represents the 25th percentile; the upper border, the 75th percentile. The lower and upper ends of the whiskers represent minimum and maximum rates for each quintile; dots represent outliers.

Discussion

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, it became clear that vulnerable and underserved populations were at particular risk of dying from the disease. In this cross-sectional study, we estimated excess mortality from March through December 2020 in a sample of more than 26.9 million older Medicare enrollees. We found that enrollees with ADRD were at higher risk of dying in 2020 compared with 2019, either directly of COVID-19 or because of premature death owing to disruptions in health care. These results hold both for patients with ADRD overall and for patients with ADRD residing in nursing homes. Higher rates of excess mortality were observed for patients with ADRD who identified as Asian, Black, and Hispanic. Furthermore, ADRD mortality rates were elevated even in regions with very low rates of community infection early in the pandemic.

Excess mortality among older adults with ADRD during the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic likely reflects many factors. First, some of the increase in mortality is due to COVID-19 itself. Prior work suggests that COVID-19 infections accounted for between 78% and 90% of the observed excess mortality in 2020.19 The higher COVID-19 mortality rate among older adults has been well documented,20,21,22,23,24 and there is some evidence suggesting that ADRD may be an age-independent risk factor for COVID-19 severity.14,25 In addition, higher COVID-19 mortality rates by race and ethnicity have also been well described.19,26,27,28,29,30 This study, however, is the first, to our knowledge, to describe the association between COVID-19 and excess mortality for older adults with or without ADRD and those living in nursing homes, including Asian, Black, and Hispanic populations.

To date, this study represents the largest examination of mortality trends among nursing home residents during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. The association between COVID-19 and mortality among nursing home residents, where COVID-19 is known to be prevalent,6 is complex. For example, Kosar et al5 found that COVID-19 mortality rates decreased among nursing home residents between March and November 2020. Other work noted that both regional infection rates and nursing home quality play important roles in determining COVID-19 mortality rates among nursing home residents.9

Unlike the Kosar et al5 study focusing on documented COVID-19 deaths, the present study found a general increase between the early and late periods of 2020 in excess mortality among nursing home residents with ADRD, suggesting that factors other than COVID-19 infection were playing a significant role in excess mortality among vulnerable populations. For example, even in HRRs with low rates of COVID-19, where excess mortality among community-dwelling patients without ADRD was slightly below that in 2019, excess mortality was 8.8% for patients with ADRD overall and 14.2% for nursing home residents with ADRD.

There are many potential explanations for this observed increase in excess mortality. For example, changes in health care delivery, including fewer inpatient admissions and the transition of outpatient visits to telehealth platforms, may disproportionately affect older adults with ADRD. Because older adults in general and older adults with cognitive impairments are less able to engage effectively with standard telehealth platforms,31,32 it is not difficult to imagine how the combination of less effective (or absent) outpatient care and lower inpatient admission rates led to higher mortality.

Although excess mortality among patients with ADRD in nursing homes may not have decreased, overall excess mortality rates for all patients with ADRD were equal to or somewhat reduced across quintiles of COVID-19 exposure from August through December 2020 compared with from March through July 2020, despite a 3-fold (or more) increase in the incidence of COVID-19. This relative stability was likely associated with better testing, “learning by doing” on the part of health care workers in reducing the risk of dying of the disease through evolving hospital procedures, and improved mask wearing and social distancing rates in geographic regions with higher infection rates.

As telehealth takes on a larger role in health care delivery,33 it will be important to monitor the outcomes of older adults, including those with ADRD and those living in nursing homes, to best understand how to adapt telehealth platforms to their specific needs. In addition, decreased access to community support services and the negative effects of social isolation and loneliness in community-dwelling individuals and nursing home residents likely played a role in higher mortality rates.34,35 Similarly, increases in caregiver stress, burden, and isolation may have indirectly affected the health of people with ADRD and people living in nursing home settings. In sum, the consistently higher excess mortality within a given COVID-19 quintile underscored the vulnerability of patients with ADRD to abrupt changes in health care delivery, lockdowns, and social isolation,7,36 particularly for underserved groups, such as Asian, Black, and Hispanic populations.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, although we used a well-validated method for determining nursing home residence, with a sensitivity of 93%, there may have been patients in alternative institutional settings, such as memory care units or group homes, who were not captured using this method. Second, COVID-19 infection rates were likely understated by poor disease detection rates in early 2020. Third, nursing home occupancy rates decreased during the course of 202037 (Table 1); thus, changes in case mix may have occurred, although our assessment of demographic information and comorbidities suggested little change (eAppendix 4 in the Supplement). Fourth, the “waves” of the pandemic did not follow a uniform timeline across the country, meaning that just 2 periods were unlikely to capture the wide variation in the timing of local infection spikes. Still, the quintiles captured wide differences in infection rates: a nearly 6-fold difference between the highest and lowest quintile in the early period, and a nearly 3-fold difference in the later period. Fifth, we are unable to determine why some HRRs fared markedly better than others, even within the same COVID-19 infection quintile; this is an area for future research.

Conclusions

In this cross-sectional study of Medicare enrollees 65 years of age and older, COVID-19 was associated with excess mortality among enrollees with ADRD, with more pronounced relative risks among Asian, Black, and Hispanic populations and for enrollees in nursing homes. The elevated mortality risk was found early in the pandemic even in areas with very low COVID-19 infection rates, suggesting that older adults with ADRD, especially those in racial and ethnic minority groups and those living in nursing homes, may be particularly susceptible to changes in health care delivery and nursing home care during the “lockdowns” and other restrictions during the pandemic.

eAppendix 1. Data Description

eAppendix 2. Confidence Intervals and Testing for Trend and Underlying Differences in Regional Mortality Rates Prior to the COVID-19 Pandemic

eAppendix 3. Values and Ranges of Average Daily Cases per 100 000 for Quintiles of Community Exposure

eAppendix 4. Nursing Home Resident Demographic Characteristic Comparison, 2019-2020

References

- 1.Engelhart K. We are going to keep you safe, even if it kills your spirit. The New York Times. February 19, 2021. Accessed January 17, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/19/opinion/covid-dementia.html

- 2.Krumholz H. Where have all the heart attacks gone? The New York Times. April 6, 2020. Accessed January 17, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/06/well/live/coronavirus-doctors-hospitals-emergency-care-heart-attack-stroke.html

- 3.Birkmeyer JD, Barnato A, Birkmeyer N, Bessler R, Skinner J. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on hospital admissions in the United States. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(11):2010-2017. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The Commonwealth Fund. The impact of COVID-19 on outpatient visits in 2020: visits remained stable, despite a late surge in cases. Published February 22, 2021. Accessed January 17, 2022. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/2021/feb/impact-covid-19-outpatient-visits-2020-visits-stable-despite-late-surge

- 5.Kosar CM, White EM, Feifer RA, et al. COVID-19 mortality rates among nursing home residents declined from March to November 2020. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021;40(4):655-663. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.02191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bagchi S, Mak J, Li Q, et al. Rates of COVID-19 among residents and staff members in nursing homes—United States, May 25-November 22, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(2):52-55. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7002e2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burns A, Howard R. COVID-19 and dementia: a deadly combination. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2021;36(7):1120-1121. doi: 10.1002/gps.5551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weinberger DM, Chen J, Cohen T, et al. Estimation of excess deaths associated with the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, March to May 2020. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(10):1336-1344. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cronin CJ, Evans WN. Nursing Home Quality, COVID-19 Deaths, and Excess Mortality. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2020. doi: 10.3386/w28012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Filice CE, Joynt KE. Examining race and ethnicity information in Medicare administrative data. Med Care. 2017;55(12):e170-e176. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eicheldinger C, Bonito A. More accurate racial and ethnic codes for Medicare administrative data. Health Care Financ Rev. 2008;29(3):27-42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taylor DH Jr, Østbye T, Langa KM, Weir D, Plassman BL. The accuracy of Medicare claims as an epidemiological tool: the case of dementia revisited. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;17(4):807-815. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-1099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mueller AL, McNamara MS, Sinclair DA. Why does COVID-19 disproportionately affect older people? Aging (Albany NY). 2020;12(10):9959-9981. doi: 10.18632/aging.103344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang C, Wang Z, Wang G, Lau JY, Zhang K, Li W. COVID-19 in early 2021: current status and looking forward. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6(1):114. doi: 10.1038/s41392-021-00527-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yun H, Kilgore ML, Curtis JR. Identifying types of nursing facility stays using Medicare claims data: an algorithm and validation. Health Serv Outcomes Res Method. 2010;10:100-110. doi: 10.1007/s10742-010-0060-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bassett MT, Chen JT, Krieger N. Variation in racial/ethnic disparities in COVID-19 mortality by age in the United States: a cross-sectional study. PLoS Med. 2020;17(10):e1003402. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.GitHub. NYtimes/COVID-19 data by county. Published 2020. Accessed June 6, 2021. https://github.com/nytimes/covid-19-data

- 18.Casella G, Berger RL. Statistical Inference. Cengage Learning; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ruhm CJ. Excess deaths in the United States during the first year of COVID-19. National Bureau of Economic Research working paper 29503. November 2021. Accessed January 18, 2022. https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w29503/w29503.pdf

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Risk for COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and death by age group. Updated November 22, 2021. Accessed April 12, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/hospitalization-death-by-age.html#footnote03

- 21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Provisional COVID-19 death counts by sex age. Updated January 12, 2022. Accessed April 12, 2021. https://data.cdc.gov/NCHS/Provisional-COVID-19-Death-Counts-by-Sex-Age-and-S/9bhg-hcku

- 22.Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, et al. ; the Northwell COVID-19 Research Consortium . Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City area. JAMA. 2020;323(20):2052-2059. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yanez ND, Weiss NS, Romand JA, Treggiari MM. COVID-19 mortality risk for older men and women. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1742. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09826-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054-1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tahira AC, Verjovski-Almeida S, Ferreira ST. Dementia is an age-independent risk factor for severity and death in COVID-19 inpatients. Alzheimers Dement. 2021;17(11):1818-1831. doi: 10.1002/alz.12352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gold JAW, Rossen LM, Ahmad FB, et al. Race, ethnicity, and age trends in persons who died from COVID-19—United States, May-August 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(42):1517-1521. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6942e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Webb Hooper M, Nápoles AM, Pérez-Stable EJ. COVID-19 and racial/ethnic disparities. JAMA. 2020;323(24):2466-2467. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cunningham TJ, Croft JB, Liu Y, Lu H, Eke PI, Giles WH. Vital signs: racial disparities in age-specific mortality among Blacks or African Americans—United States, 1999-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(17):444-456. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6617e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shiels MS, Haque AT, Haozous EA, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in excess deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic, March to December 2020. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(12):1693-1699. doi: 10.7326/M21-2134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cronin CJ, Evans WN. Excess mortality from COVID and non-COVID causes in minority populations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118(39):e2101386118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2101386118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Possin KL, Merrilees JJ, Dulaney S, et al. Effect of collaborative dementia care via telephone and internet on quality of life, caregiver well-being, and health care use: the Care Ecosystem Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(12):1658-1667. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.4101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schifeling CH, Shanbhag P, Johnson A, et al. Disparities in video and telephone visits among older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: cross-sectional analysis. JMIR Aging. 2020;3(2):e23176. doi: 10.2196/23176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.The Future of Telehealth: How Covid-19 Is Changing the Delivery of Virtual Care. American College of Physicians; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Giebel C, Hanna K, Rajagopal M, et al. The potential dangers of not understanding COVID-19 public health restrictions in dementia: “It’s a groundhog day—every single day she does not understand why she can’t go out for a walk.” BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):762. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10815-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kotwal AA, Holt-Lunstad J, Newmark RL, et al. Social isolation and loneliness among San Francisco Bay Area older adults during the COVID-19 shelter-in-place orders. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(1):20-29. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brown EE, Kumar S, Rajji TK, Pollock BG, Mulsant BH. Anticipating and mitigating the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020;28(7):712-721. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.04.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.National Investment Center. Occupancy at U.S. skilled nursing facilities hits new low. Updated November 2021. Accessed January 18, 2021. https://www.nic.org/news-press/occupancy-at-u-s-skilled-nursing-facilities-hits-new-low

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix 1. Data Description

eAppendix 2. Confidence Intervals and Testing for Trend and Underlying Differences in Regional Mortality Rates Prior to the COVID-19 Pandemic

eAppendix 3. Values and Ranges of Average Daily Cases per 100 000 for Quintiles of Community Exposure

eAppendix 4. Nursing Home Resident Demographic Characteristic Comparison, 2019-2020