Key Points

Question

Does the addition of recombinant human (rh) insulin to human milk and preterm formula reduce feeding intolerance in preterm infants?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial that included 303 preterm infants, 2 different rh-insulin dosages significantly reduced the time to full enteral feeding compared with placebo. The percentage of serious adverse events was 15% (16 of 108) in the low-dose group, 13% (11 of 88) in the high-dose group, and 20% (19 of 97) in the placebo group; none of the infants developed serum insulin antibodies.

Meaning

These findings support the use of rh insulin as a supplement to human milk and preterm formula.

This randomized clinical trial investigates whether feeding intolerance in preterm infants can be reduced with the addition of recombinant human insulin to human milk and preterm formula.

Abstract

Importance

Feeding intolerance is a common condition among preterm infants owing to immaturity of the gastrointestinal tract. Enteral insulin appears to promote intestinal maturation. The insulin concentration in human milk declines rapidly post partum and insulin is absent in formula; therefore, recombinant human (rh) insulin for enteral administration as a supplement to human milk and formula may reduce feeding intolerance in preterm infants.

Objective

To assess the efficacy and safety of 2 different dosages of rh insulin as a supplement to both human milk and preterm formula.

Design, Setting, and Participants

The FIT-04 multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial was conducted at 46 neonatal intensive care units throughout Europe, Israel, and the US. Preterm infants with a gestational age (GA) of 26 to 32 weeks and a birth weight of 500 g or more were enrolled between October 9, 2016, and April 25, 2018. Data were analyzed in January 2020.

Interventions

Preterm infants were randomly assigned to receive low-dose rh insulin (400-μIU/mL milk), high-dose rh insulin (2000-μIU/mL milk), or placebo for 28 days.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was time to achieve full enteral feeding (FEF) defined as an enteral intake of 150 mL/kg per day or more for 3 consecutive days.

Results

The final intention-to-treat analysis included 303 preterm infants (low-dose group: median [IQR] GA, 29.1 [28.1-30.4] weeks; 65 boys [59%]; median [IQR] birth weight, 1200 [976-1425] g; high-dose group: median [IQR] GA, 29.0 [27.7-30.5] weeks; 52 boys [55%]; median [IQR] birth weight, 1250 [1020-1445] g; placebo group: median [IQR] GA, 28.8 [27.6-30.4] weeks; 54 boys [55%]; median [IQR] birth weight, 1208 [1021-1430] g). The data safety monitoring board advised to discontinue the study early based on interim futility analysis (including the first 225 randomized infants), as the conditional power did not reach the prespecified threshold of 35% for both rh-insulin dosages. The study continued while the data safety monitoring board analyzed and discussed the data. In the final intention-to-treat analysis, the median (IQR) time to achieve FEF was significantly reduced in 94 infants receiving low-dose rh insulin (10.0 [7.0-21.8] days; P = .03) and in 82 infants receiving high-dose rh insulin (10.0 [6.0-15.0] days; P = .001) compared with 85 infants receiving placebo (14.0 [8.0-28.0] days). Compared with placebo, the difference in median (95% CI) time to FEF was 4.0 (1.0-8.0) days for the low-dose group and 4.0 (1.0-7.0) days for the high-dose group. Weight gain rates did not differ significantly between groups. Necrotizing enterocolitis (Bell stage 2 or 3) occurred in 7 of 108 infants (6%) in the low-dose group, 4 of 88 infants (5%) in the high-dose group, and 10 of 97 infants (10%) in the placebo group. None of the infants developed serum insulin antibodies.

Conclusions and Relevance

Results of this randomized clinical trial revealed that enteral administration of 2 different rh-insulin dosages was safe and compared with placebo, significantly reduced time to FEF in preterm infants with a GA of 26 to 32 weeks. These findings support the use of rh insulin as a supplement to human milk and preterm formula.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02510560

Introduction

Feeding intolerance is a common condition among preterm infants owing to immaturity of the gastrointestinal tract. Clinical symptoms consist of gastric residuals, vomiting, and/or abdominal distention.1 Feeding intolerance prolongs dependency on parenteral nutrition, which, in turn, is associated with an increased risk of complications (eg, late-onset sepsis and intestinal failure–associated liver disease).2,3,4 Thus, strategies to ameliorate feeding intolerance are necessary.

Preterm infants fed with mother’s own milk have a more rapid postnatal intestinal maturation, fewer clinical symptoms of feeding intolerance, and a lower risk of postnatal complications relative to preterm infants fed with formula.5,6,7,8 The intestinal stimulating effect of mother’s own milk appears attributed to its numerous nonnutritive bioactive factors, including the peptide hormone insulin.9 It has been shown that the natural insulin concentration in human milk peaks in the early postpartum period but declines to a basal level within the first 3 days post partum.10 To date, insulin is absent in formula.

Therefore, a recombinant human (rh) insulin formulation for enteral administration in preterm infants has been developed in order to combat feeding intolerance and thereby improve short- and long-term clinical outcomes. In a small phase 2 trial, time to achieve full enteral feeding (FEF) was significantly reduced in preterm infants treated with rh-insulin–supplemented formula (n = 16) compared with preterm infants treated with placebo-supplemented formula (n = 15).11

Accordingly, this international, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial was performed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of 2 different dosages of rh insulin as a supplement to human milk and preterm formula in preterm infants with a gestational age (GA) of 26 to 32 weeks at birth. We hypothesized that rh-insulin supplementation would reduce time to achieve FEF in this population.

Methods

Study Design

This multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial was conducted at 46 neonatal intensive care units throughout Europe, Israel, and the United States from October 9, 2016, to April 25, 2018. The trial protocol can be found in Supplement 1, and the statistical analysis plan can be found in Supplement 2. The FIT-04 site collaborators are listed in eTable 1 in Supplement 3. An international steering committee had final responsibility for the design and conduct of the trial (eTable 2 in Supplement 3). Clinical research organizations covered regulatory aspects and verification of the data. The study was approved by the ethical review committee at each participating center, and written informed consent was obtained from all parents. This study followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guidelines.

Participants

Preterm infants born between 26 weeks and 0 days and 32 weeks and 0 days of gestation and with a birth weight of 500 g or more were eligible if they were clinically stable, able to tolerate enteral feeding, and expected to wean off parenteral nutrition during their stay in the primary hospital. Infant race and ethnicity were self-identified by the infants’ parents as Asian, Black or African American, White, multiracial (which indicates that the parents of the infant were each of a different race and ethnicity), and unknown. The exclusion criteria comprised major congenital malformations, suspected infection (ie, positive blood culture, leukocytosis with a white blood cell count >30 000 μL, or leukopenia with a white blood cell count <4000 μL), fraction of inspired oxygen of 0.60 or more at randomization, intrauterine growth restriction (defined as weight for GA <3rd percentile according to the Fenton growth chart or <10th percentile in combination with abnormal Doppler velocimetry), confirmed necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC; Bell stage 2 or 312), FEF at randomization, postnatal age older than 5 days at randomization, hyperinsulinemia requiring greater than 12 mg/kg per minute glucose administration, any systemic insulin administration, maternal diabetes (type I, II, or gestational) requiring insulin, nothing administered by mouth for any reason, and chest compressions or resuscitation drugs given directly after birth.

Randomization and Intervention

Participants were randomly assigned to receive either low-dose rh insulin (400-μIU/mL milk), high-dose rh insulin (2000-μIU/mL milk), or placebo in an allocation ratio of 1:1:1 using a central-controlled computer program. The central-controlled computer program generated a randomization number and an investigational medical product (IMP) pack number for each infant. The dosage of 400 μIU/mL is comparable with the natural physiological peak insulin concentration in human colostrum, and the dosage of 2000 μIU/mL is supraphysiological relative to the natural insulin concentration in human colostrum.10

Randomization was blocked and stratified per center according to GA at birth (stratum A: 26 weeks and 0 days to 28 weeks and 6 days; stratum B: 29 weeks and 0 days to 32 weeks and 0 days). The sponsor, the parents, and all members of the medical team, including investigators, remained blinded to group assignment throughout the study.

The trial began within 5 days post partum (up to 120 hours). If the infant was exclusively fed mother’s own milk, treatment was not initiated until 72 hours post partum. The standard duration of the intervention was 28 days, but treatment was discontinued earlier in cases where a unit or hospital transfer was required. Daily enteral and parenteral nutrition amount and composition were determined by the attending physician, who was blinded to group assignment. All sites selected for this study followed the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition guidelines13 as their standard of care (eTables 3 and 4 in Supplement 3) to reduce site-to-site variations.

Investigational Medicinal Product

The IMP was an rh-insulin formulation (powder) developed for enteral administration. The IMP contained either 0.04 IU/g of rh insulin or 0.2 IU/g of rh insulin for the low- and high-dose group, respectively (ELGAN Pharma). The placebo was manufactured identically but without the inclusion of rh insulin. The IMP was packaged into sachets each containing 0.5 g of the IMP. Then, 200 sachets with an identical pack number were packaged into sealed boxes.

For each participating infant, a standard stock solution was prepared daily by the researcher, physician, or neonatal nurse using 1 sachet per 1.8-mL solvent (mother’s own milk, donor human milk, or preterm formula). Subsequently, a dosage of 0.04 mL stock solution per planned milliliter of enteral feeding was prescribed daily for all participating infants to obtain the target rh-insulin concentration (400-μIU/mL milk in the low-dose group; 2000-μIU/mL milk in the high-dose group; and placebo). The total daily prescribed amount of stock solution was administered throughout the day in at least 4 administrations either directly through the nasogastric tube before feeding or added to the enteral feeding, depending on hospital preferences. The minimum of 4 administrations was to ensure intestinal rh-insulin exposure throughout the day.

Study Outcomes

The primary outcome was time to achieve FEF, which was defined as an enteral intake of at least 150 mL/kg per day for 3 consecutive days. Secondary outcomes were the number and percentage of infants reaching FEF within 6, 8, and 10 days of intervention, time to achieve an enteral intake of 120 mL/kg per day or more for 3 consecutive days, the number of days receiving parenteral nutrition, growth velocity (body weight, body length, and head circumference), body weight on study day 28, body weight z score on study day 28, and change in body weight z score.

Safety outcomes included serious adverse events (SAEs) and suspected unexpected serious adverse reactions. Blood glucose tests were performed twice daily in the first 4 study days and thereafter on alternate days between 7 am and 10 am before enteral feeding. An extra blood sample was collected at study day 28 or, if earlier, was collected on the day of hospital transfer, transfer to another unit within the hospital, or discharge to home for insulin antibody assessment. In addition, a blood sample was collected at 3 months’ corrected age for insulin antibody assessment.

Statistical Analysis

A reduction in time to achieve FEF, from 8.0 days in the placebo group to 6.6 days in both active-treatment groups, was deemed clinically relevant. A similar reduction was observed in the phase 2 trial.11 To detect this difference with a power of 80% (α = .05, 2-sided, SD of 3.5 days for both groups), 115 infants were required for each group. To account for dropouts and the inclusion of twins (only the first sibling was randomized, and the second sibling was allocated to the same treatment group), the estimated total sample size required was 460 infants.

The primary and secondary efficacy analyses were performed according to intention-to-treat principles, regardless of protocol deviations. Parents of infants who withdrew consent to participate in the study were included up to the date of withdrawal. The primary outcome was analyzed as an ordinal variable. Infants not reaching FEF within the intervention period owing to slow enteral nutrition advancement were allocated to study day 28. Infants with NEC (Bell stage 2 or 3) within the intervention period were allocated to study day 29 (primary outcome), and infants who died within the intervention period were allocated to study day 30 (primary outcome), as prespecified in the statistical analysis plan (Supplement 2). Body weight z score was calculated by using the Fenton growth chart.14 In addition, we performed prespecified subgroup analysis based on GA at birth (26 weeks and 0 days to 28 weeks and 6 days and 29 weeks and 0 days to 32 weeks and 0 days) and sensitivity analysis (ie, analysis excluding the second-born sibling of a twin and imputation to account for missing data). The safety analysis included all infants that received the IMP.

An independent data safety monitoring board (DSMB) conducted 2 interim analyses for safety outcomes after randomization of the first 50 to 70 infants and 175 to 195 infants. The interim analysis for futility was performed by an unblinded statistician (contracted clinical research organization). The results of the data analysis by the statistician were presented in a blinded manner to the DSMB. The DSMB provided recommendations on study continuation or termination according to the criteria in the prespecified statistical analysis plan. The conditional power used for the interim analysis for futility was defined as the reevaluated power estimation based on data of the first 225 randomized preterm infants. The threshold was set at a conditional power of 35%, meaning that a conditional power less than 35% in either dose was considered futile.

Efficacy and safety outcomes were assessed from initiation of study treatment. Groups were compared by using the van Elteren test for numerical variables. The van Elteren test is an extension of the Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test that allows for the stratification of patients. Patients were stratified by GA at birth (stratum A: 26 weeks and 0 days to 28 weeks and 6 days; stratum B: 29 weeks and 0 days to 32 weeks and 0 days). The 95% CI of the median difference was calculated by using bootstrapping as the data was not normally distributed. The χ2 test was used for categorical variables. A gatekeeping procedure was performed to adjust for multiple testing.15 Data were analyzed in January 2020 using R statistical software, version 4.0.2 (R Core Team). A 2-sided P value < .05 was considered significant.

Results

Enrollment

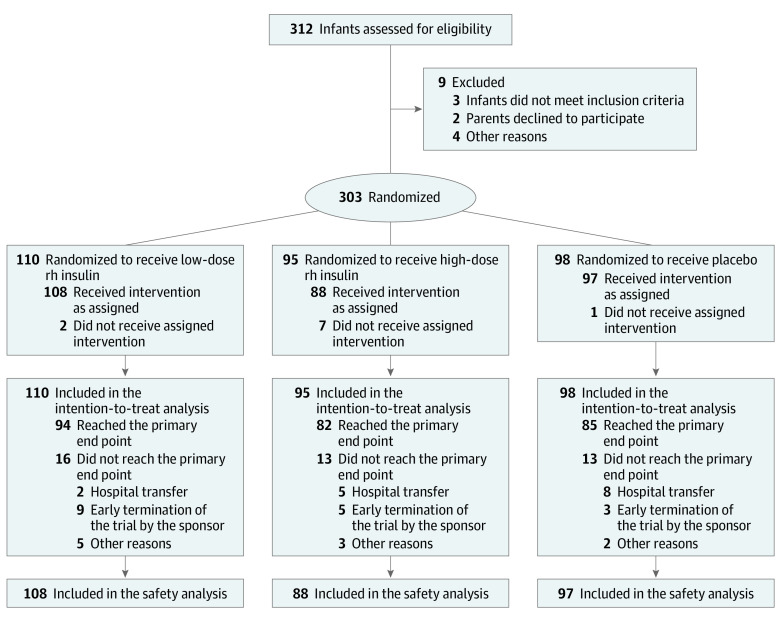

Study enrollment occurred between October 9, 2016, and April 25, 2018. A total of 312 infants were screened; of these, 303 met the eligibility criteria and underwent randomization. Ultimately, 110 infants were allocated to low-dose rh insulin (median [IQR] GA, 29.1 [28.1-30.4] weeks; 65 boys [59%]; 45 girls [41%]; median [IQR] birth weight, 1200 [976-1425] g; 2 [2%] Asian, 6 [5%] Black or African American, 93 [85%] White, 4 [4%] multiracial, 5 [5%] unknown race and ethnicity), 95 infants to high-dose rh insulin (median [IQR] GA, 29.0 [27.7-30.5] weeks; 52 boys [55%]; 43 girls [45%]; median [IQR] birth weight, 1250 [1020-1445] g; 1 [1%] Asian, 5 [5%] Black or African American, 88 [93%] White, 1 [1%] unknown race and ethnicity), and 98 infants to placebo (median [IQR] GA, 28.8 [27.6-30.4] weeks; 54 boys [55%]; 44 girls [45%]; median [IQR] birth weight, 1208 [1021-1430] g; 1 [1%] Asian, 6 [6%] Black or African American, 86 [88%] White, 3 [3%] multiracial, 2 [2%] unknown race and ethnicity) (Figure 1). Baseline characteristics were similar between the 3 groups (Table 1).

Figure 1. Flow Diagram.

Abbreviation: rh, recombinant human.

Table 1. Infant Characteristicsa.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Low dose (400 μIU/mL) | High dose (2000 μIU/mL) | Placebo | |

| Total, No. | 110 | 95 | 98 |

| Gestational age at birth, median (IQR), wk | 29.1 (28.1-30.4) | 29.0 (27.7-30.5) | 28.8 (27.6-30.4) |

| Birth weight, median (IQR), g | 1200 (976-1425) | 1250 (1020-1445) | 1208 (1021-1430) |

| Birth weight <1000 g | 31 (28) | 21 (22) | 22 (22) |

| Head circumference at birth, median (IQR), cm | 26.8 (25.0-28.0) | 26.5 (25.0-28.0) | 27.0 (25.5-28.5) |

| Infant sex | |||

| Male | 65 (59) | 52 (55) | 54 (55) |

| Female | 45 (41) | 43 (45) | 44 (45) |

| Multiple birth | 35 (32) | 29 (31) | 26 (27) |

| Infant race and ethnicity | |||

| Asian | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Black or African American | 6 (5) | 5 (5) | 6 (6) |

| White | 93 (85) | 88 (93) | 86 (88) |

| Multiracialb | 4 (4) | 0 | 3 (3) |

| Unknown | 5 (5) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) |

| Apgar score at 5 min, median (IQR) | 8.0 (8.0-9.0) | 9.0 (8.0-9.0) | 8.0 (7.0-9.0) |

| Cesarean delivery | 80 (73) | 55 (58) | 65 (66) |

| Antenatal steroids | 54 (49) | 45 (47) | 37 (38) |

| Age at randomization, median (IQR), d | 4 (4-5) | 4 (4-5) | 4 (3-5) |

| Age at first enteral feeding, median (IQR), dc | 2 (1-2) | 1 (1-2) | 2 (1-2) |

| Type of nutritiond | |||

| Mother’s own milk | 37 (34) | 30 (32) | 29 (30) |

| Donor human milk | 2 (2) | 3 (3) | 4 (4) |

| Preterm formula | 8 (7) | 3 (3) | 5 (5) |

| Mixede | 61 (55) | 56 (59) | 60 (61) |

| Unknown | 2 (2) | 3 (3) | 0 |

| Country | |||

| Europe | |||

| Belgium | 14 (13) | 5 (5) | 8 (8) |

| Bulgaria | 3 (3) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) |

| France | 4 (4) | 10 (11) | 12 (12) |

| Germany | 3 (3) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) |

| Hungary | 7 (6) | 6 (6) | 5 (5) |

| Italy | 16 (15) | 13 (14) | 15 (15) |

| The Netherlands | 25 (23) | 24 (25) | 25 (26) |

| Spain | 17 (15) | 20 (21) | 11 (11) |

| UK | 5 (5) | 3 (3) | 5 (5) |

| Israel | 10 (9) | 6 (6) | 8 (8) |

| US | 6 (5) | 5 (5) | 5 (5) |

No significant differences were found between the 3 groups in the listed categories.

Multiracial indicates that the parents of the infant were each of a different race and ethnicity.

Date of birth was considered as day 1.

Type of nutrition during the intervention period.

Mixed feeding was defined as the total enteral nutrition intake consisting of mother’s own milk and donor human milk, donor human milk and preterm formula, or mother’s own milk and preterm formula.

Interim Futility Analysis

The DSMB advised to discontinue the study early based on interim futility analysis (including the first 225 randomized infants), as the conditional power was below the prespecified threshold of 35% for both rh-insulin dosages. The international steering committee and sponsor accepted this recommendation, and the trial was terminated on April 25, 2018. Infants continued to be enrolled while the DSMB analyzed and discussed the data. Therefore, the final intention-to-treat analysis was based on a higher number of infants (303) than that used in the interim futility analysis.

Primary Outcome

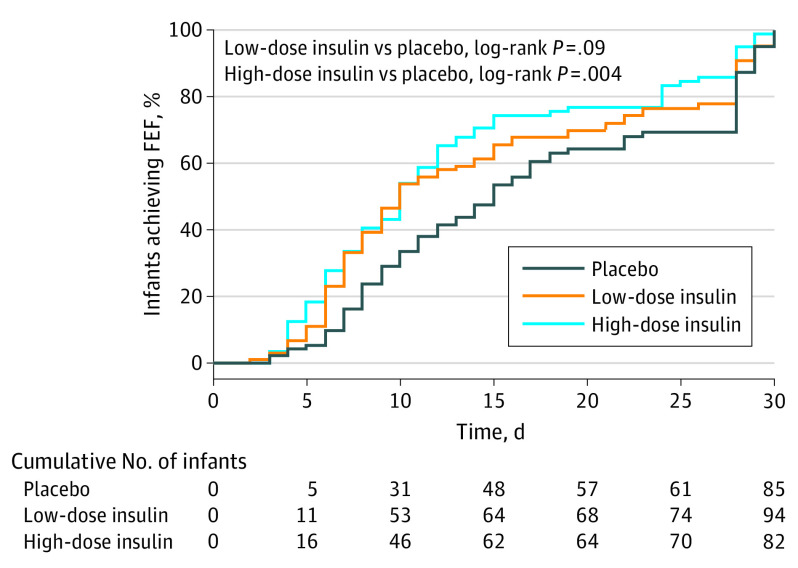

Of the 303 included infants, 261 (86%) reached the primary outcome. The major reasons for failing to reach the outcome were early study termination owing to hospital transfer and early termination of the trial by the sponsor. In the final intention-to-treat analysis, median (IQR) time to achieve FEF (at least 150 mL/kg per day for 3 consecutive days) was significantly reduced in 94 infants receiving low-dose rh insulin (10.0 [7.0-21.8] days; P = .03) and in 82 infants receiving high-dose rh insulin (10.0 [6.0-15.0] days; P = .001) compared with 85 infants receiving placebo (14.0 [8.0-28.0] days). Compared with placebo, the difference in median (95% CI) time to FEF was 4.0 (1.0-8.0) days for the low-dose group and 4.0 (1.0-7.0) days for the high-dose group. The Kaplan-Meier curve of the primary outcome is shown in Figure 2, and the sensitivity analysis is shown in eTable 5 in Supplement 3. The primary outcome remained significant for both rh-insulin dosages after adjustment for multiple testing.

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier Curve of the Primary Outcome (Intention to Treat).

The primary outcome was the time to achieve full enteral feeding (FEF), which was defined as an enteral intake of 150 mL/kg per day or more for 3 consecutive days.

Secondary Outcomes

The proportion of infants who achieved FEF in the first 6, 8, and 10 days of intervention was significantly higher in both active-treatment groups compared with the placebo group (day 6: low dose, 23 infants [21%]; P = .02; high dose, 24 infants [25%]; P = .003; placebo, 9 infants [9%]; day 8: low dose, 39 infants [35%]; P = .04; high dose, 35 infants [37%]; P = .03; placebo, 22 infants [22%]; day 10: low dose, 53 infants [48%]; P = .02; high dose, 46 infants [48%]; P = .02; placebo, 31 infants [32%]) (Table 2). In addition, time to achieve an enteral intake of 120 mL/kg per day or more for 3 consecutive days was significantly reduced in both active-treatment groups compared with the placebo group (median [IQR] time: low dose, 6.0 [4.0-11.0] days; P = .049; high dose, 6.0 [4.0-11.0] days; P = .01; placebo, 8.0 [6.0-12.0] days). The number of days receiving parenteral nutrition was significantly reduced in the high-dose group compared with the placebo group. Weight gain rates did not differ significantly between groups.

Table 2. Efficacy Outcomes (Intention to Treat).

| Outcome | Recombinant human insulin | Placebo | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low dose (400-μIU/mL milk) | High dose (2000-μIU/mL milk) | ||

| Primary outcome | |||

| Time to achieve full enteral feeding (≥150 mL/kg/d for 3 consecutive days) | |||

| Total, No. | 94 | 82 | 85 |

| Median (IQR) | 10.0 (7.0 to 21.8) | 10.0 (6.0 to 15.0) | 14.0 (8.0 to 28.0) |

| P valuea | .03 | .001 | NA |

| Difference in medians (95% CI)b | 4.0 (1.0 to 8.0) | 4.0 (1.0 to 7.0) | NA |

| Secondary outcomes | |||

| Infants achieving full enteral feeding (≥150 mL/kg/d for 3 consecutive days) | |||

| Study day 6 | |||

| No. (%) | 23 (21) | 24 (25) | 9 (9) |

| P valuea | .02 | .003 | NA |

| Study day 8 | |||

| No. (%) | 39 (35) | 35 (37) | 22 (22) |

| P valuea | .04 | .03 | NA |

| Study day 10 | |||

| No. (%) | 53 (48) | 46 (48) | 31 (32) |

| P valuea | .02 | .02 | NA |

| Time to achieve an enteral intake of ≥120 mL/kg/d for 3 consecutive days | |||

| No. | 95 | 85 | 91 |

| Median (IQR), d | 6.0 (4.0 to 11.0) | 6.0 (4.0 to 11.0) | 8.0 (6.0 to 12.0) |

| P valuea | .049 | .01 | NA |

| Days receiving parenteral nutrition | |||

| No. | 101 | 86 | 92 |

| Median (IQR), d | 6.0 (4.0 to 10.0) | 6.0 (3.0 to 10.0) | 7.5 (5.0 to 11.0) |

| P valuea | .25 | .03 | NA |

| Weight gain | |||

| No. | 104 | 91 | 95 |

| Median (IQR), g/kg/d | 17.4 (14.0 to 20.1) | 17.2 (15.0 to 19.2) | 17.9 (15.2 to 19.6) |

| P valuea | .64 | .37 | NA |

| Body weight on study day 28 | |||

| No. | 71 | 63 | 70 |

| Median (IQR), g | 1740 (1430 to 2150) | 1830 (1468 to 2112) | 1770 (1566 to 2160) |

| P valuea | .99 | .31 | NA |

| Body weight z score on study day 28 | |||

| No. | 71 | 63 | 70 |

| Median (IQR) | −0.7 (−1.1 to −0.3) | −0.8 (−1.2 to −0.4) | −0.6 (−1.1 to −0.2) |

| P valuea | .28 | .25 | NA |

| Change in body weight z score | |||

| No. | 71 | 63 | 70 |

| Median (IQR) | −0.1 (−0.3 to 0.2) | −0.1 (−0.4 to 0) | 0 (−0.3 to 0.2) |

| P valuea | .85 | .09 | NA |

| Head circumference | |||

| No. | 98 | 86 | 88 |

| Median (IQR), cm/wk | 0.8 (0.5 to 0.9) | 0.8 (0.5 to 0.9) | 0.7 (0.5 to 0.9) |

| P valuea | .34 | .34 | NA |

| Body length | |||

| No. | 80 | 72 | 76 |

| Median (IQR), cm/wk | 1.0 (0.6 to 1.4) | 1.0 (0.6 to 1.3) | 1.0 (0.5 to 1.4) |

| P valuea | .67 | .85 | NA |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

P value represents comparison between the active-treatment group and the placebo group.

95% CI was calculated by bootstrapping as the data were not normally distributed.

Subgroup Analyses

Median (IQR) time to achieve FEF in infants with a GA of 26 weeks and 0 days to 28 weeks and 6 days was 15.0 (7.0-28.0) days in the low-dose group (n = 45), 12.0 (8.0-24.0) days in the high-dose group (n = 41), and 16.5 (10.0-28.0) days in the placebo group (n = 46). The difference between the high-dose and placebo group was statistically significant (P = .04). In the subgroup of infants with a GA of 29 weeks and 0 days to 32 weeks and 0 days, median (IQR) time to achieve FEF was significantly reduced in the high-dose group compared with the placebo group (high-dose group [n = 41]: 7.0 [5.0-12.0] days; placebo group [n = 39]: 11.0 [7.5-18.0] days; P = .01). Median (IQR) time to achieve FEF in this specific subgroup was 9.0 (6.0-14.0) days (n = 49) in the low-dose group (low-dose vs placebo; P = .05).

Safety Outcomes

The SAEs are shown in Table 3. A total of 16 of 108 infants (15%) in the low-dose group, 11 of 88 infants (13%) in the high-dose group, and 19 of 97 infants (20%) in the placebo group had 1 or more SAEs. Two of 108 infants (2%) in the low-dose group, 3 of 88 infants (3%) in the high-dose group, and 3 of 97 infants (3%) in the placebo group had 1 or more hypoglycemic event. NEC (Bell stage 2 or 3) occurred in 7 of 108 infants (6%) in the low-dose group, 4 of 88 infants (5%) in the high-dose group, and 10 of 97 infants (10%) in the placebo group. None of the infants developed serum insulin antibodies.

Table 3. Safety Outcomesa.

| Outcome | No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Recombinant human insulin | Placebo | ||

| Low dose (400-μIU/mL milk) | High dose (2000-μIU/mL milk) | ||

| Total No. of infants included in safety analysis | 108 | 88 | 97 |

| Infants with ≥1 SAE | 16 (15) | 11 (13) | 19 (20) |

| Total No. of reported SAEs | 32 | 18 | 34 |

| NEC (Bell stage 2 or 3)b | 7 (6) | 4 (5) | 10 (10) |

| Clinical- or culture-proved sepsis | 13 (12) | 10 (11) | 15 (15) |

| Mortality | 5 (5) | 1 (1) | 4 (4) |

Abbreviations: NEC, necrotizing enterocolitis; SAE, serious adverse event.

Reported until discharged to home.

Bell staging criteria, based on clinical and radiographic signs, are used to identify and classify NEC in infants.

Discussion

In this double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial, enteral administration of 2 different rh-insulin dosages was found to be safe and, compared with placebo, significantly reduced time to achieve FEF in preterm infants with a GA of 26 to 32 weeks.

The mechanism underlying the beneficial clinical effects of rh insulin as observed in our study has been investigated in animals. The small intestinal weight and intestinal disaccharidase activity (ie, lactase, sucrase, maltase) were significantly higher in both piglets and rats treated with either enteral rh insulin or enteral recombinant porcine insulin relative to controls, suggesting that insulin has a key role in promoting intestinal maturation.16,17,18,19 The effect of enteral insulin on the intestine seems to be mediated by insulin receptors, which have been observed on both the apical and basolateral enterocyte membrane of various animals.20,21,22,23,24 In humans, insulin receptor development on enterocyte membranes has been investigated in fetuses to a limited extent.25 Up to 19 weeks of gestation, insulin receptors were found solely on the basolateral membrane of the enterocytes. To our knowledge, insulin receptor expression, particularly on the apical enterocyte membrane, has never been investigated in fetuses in the third trimester of gestation nor on intestinal tissues of preterm infants obtained during surgery.

In agreement with animal studies, the intestinal lactase activity was significantly higher in 6 preterm infants (GA of 26-29 weeks) receiving enteral rh insulin (4 IU/kg per day) compared with a historical control group of 43 infants in a pilot study.26 However, this pilot study was limited by its study design and small sample size; thus, additional studies are needed to further investigate the effect of rh insulin on intestinal lactase activity in preterm infants.

The effect of enteral rh insulin on time to achieve FEF was greater in our study than expected based on the data of a small, phase 2, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial (31 preterm infants; GA of 26-33 weeks) used for the a priori sample calculation, resulting in an overestimation of the estimated sample size needed for adequate power.27 To illustrate, to demonstrate a reduction in time to achieve FEF of 4 days as observed in our study (α = .05; power = 80%), approximately 85 infants per group would be needed. Therefore, we were able to find significant results, even though our trial was discontinued after enrollment of 303 patients.

The interim futility analysis (including the first 225 randomized infants) showed a conditional power that was below the prespecified stopping threshold of 35% for both rh-insulin dosages, suggesting that both dosages were unlikely to reach significant efficacy. However, the final analysis (including all randomized preterm infants) showed a statistically significant effect of both rh-insulin dosages. The inaccurate futility prediction may be a consequence of suboptimal a priori selection of the stopping threshold, which was quite high in our study (35%).28,29,30 Therefore, a lower stopping threshold is recommended in further trials to reduce the likelihood of erroneous early termination of an effective intervention.

In the GA subgroups, only high-dose rh insulin significantly reduced the time to achieve FEF relative to placebo. In addition, the number of days receiving parenteral nutrition was significantly reduced only in the high-dose group relative to the placebo group. This suggests that high-dose rh insulin is the preferred dose for routine administration in clinical practice; however, further studies are needed to corroborate this effect before incorporating high-dose rh-insulin supplementation into enteral nutrition guidelines for preterm infants. Furthermore, the potential long-term benefits (eg, neurodevelopmental outcome) require additional investigation.

A considerable proportion of the participants (16%) had 1 or more SAE, which is consistent with the expected rate of events in a population of preterm infants with a GA of 26 to 32 weeks.31 Importantly, the SAEs were not ascribed to enteral rh-insulin treatment, and none of the infants developed insulin antibodies. The number of hypoglycemic events was similar in the active-treatment groups and placebo group, which suggests that enteral rh insulin is not absorbed into the systemic circulation despite the supraphysiological concentration of 2000 μIU/mL milk. These results are consistent with the safety data from the small preliminary studies on enteral rh-insulin supplementation in preterm infants.26,27,32

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, the primary outcome of 42 infants (14%) was not available mainly owing to hospital transfer before reaching the primary outcome and early termination of the trial by the sponsor. However, the percentage was similar among the 3 study groups, and an imputation of the missing data did not affect the outcome, suggesting that absence of data from these 42 infants did not influence the results. Second, an inherent risk associated with international multicenter studies is that differences in standards of care among the sites could affect outcomes. However, nutrition guidelines were incorporated into the study protocol to minimize site-to-site variations. In addition, randomization was stratified by center to ensure that variations were equally distributed across the 3 treatment groups. Third, infants with a GA younger than 26 weeks were excluded from the trial. We expect that the effect would be even more significant in infants with a lower GA given that time to achieve FEF is inversely related to GA; nevertheless, this hypothesis needs to be tested in additional trials. The fourth limitation of this trial was the selection of a high futility threshold (35%), resulting in erroneous early termination of the study.

Conclusions

In conclusion, results of this randomized clinical trial showed that enteral administration of 2 different rh-insulin dosages was safe and compared with placebo, significantly reduced time to achieve FEF in preterm infants with a GA of 26 to 32 weeks. These findings support the use of rh insulin as a supplement to human milk and preterm formula.

Trial Protocol

Statistical Analysis Plan

eTable 1. The FIT-04 Site Collaborators

eTable 2. Trial Steering Committee Members

eTable 3. Enteral Nutrition Recommendation in the Study Protocol (ESPGHAN guidelines)

eTable 4. Total Fluid (Enteral and Parenteral) and Nutritive Components

eTable 5. Prespecified Sensitivity Analysis of the Primary Outcome

eReferences

FIT-04 Study Group

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Fanaro S. Feeding intolerance in the preterm infant. Early Hum Dev. 2013;89(suppl 2):S13-S20. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2013.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shah J, Jefferies AL, Yoon EW, Lee SK, Shah PS; Canadian Neonatal Network . Risk factors and outcomes of late-onset bacterial sepsis in preterm neonates born at < 32 weeks’ gestation. Am J Perinatol. 2015;32(7):675-682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El Manouni El Hassani S, Berkhout DJC, Niemarkt HJ, et al. Risk factors for late-onset sepsis in preterm infants: a multicenter case-control study. Neonatology. 2019;116(1):42-51. doi: 10.1159/000497781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calkins KL, Venick RS, Devaskar SU. Complications associated with parenteral nutrition in the neonate. Clin Perinatol. 2014;41(2):331-345. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2014.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taylor SN, Basile LA, Ebeling M, Wagner CL. Intestinal permeability in preterm infants by feeding type: mother’s milk versus formula. Breastfeed Med. 2009;4(1):11-15. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2008.0114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shulman RJ, Schanler RJ, Lau C, Heitkemper M, Ou CN, Smith EO. Early feeding, feeding tolerance, and lactase activity in preterm infants. J Pediatr. 1998;133(5):645-649. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(98)70105-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moore TA, Pickler RH. Feeding intolerance, inflammation, and neurobehaviors in preterm infants. J Neonatal Nurs. 2017;23(3):134-141. doi: 10.1016/j.jnn.2016.09.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corpeleijn WE, Kouwenhoven SM, Paap MC, et al. Intake of own mother’s milk during the first days of life is associated with decreased morbidity and mortality in very low birth weight infants during the first 60 days of life. Neonatology. 2012;102(4):276-281. doi: 10.1159/000341335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shehadeh N, Gelertner L, Blazer S, Perlman R, Solovachik L, Etzioni A. Importance of insulin content in infant diet: suggestion for a new infant formula. Acta Paediatr. 2001;90(1):93-95. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2001.tb00262.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mank E, van Toledo L, Heijboer AC, van den Akker CHP, van Goudoever JB. Insulin concentration in human milk in the first ten days post partum: course and associated factors. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2021;73(5):e115-e119. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000003214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shehadeh N, Simmonds A, Zangen S, Riskin A, Shamir R. Efficacy and safety of enteral recombinant human insulin for reduction of time-to-full enteral feeding in preterm infants: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Isr Med Assoc J. 2021;23(9):563-568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bell MJ, Ternberg JL, Feigin RD, et al. Neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. therapeutic decisions based upon clinical staging. Ann Surg. 1978;187(1):1-7. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197801000-00001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agostoni C, Buonocore G, Carnielli VP, et al. ; ESPGHAN Committee on Nutrition . Enteral nutrient supply for preterm infants: commentary from the European Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition Committee on Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;50(1):85-91. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181adaee0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fenton TR, Griffin IJ, Hoyos A, et al. Accuracy of preterm infant weight gain velocity calculations vary depending on method used and infant age at time of measurement. Pediatr Res. 2019;85(5):650-654. doi: 10.1038/s41390-019-0313-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yadav K, Lewis RJ. Gatekeeping strategies for avoiding false-positive results in clinical trials with many comparisons. JAMA. 2017;318(14):1385-1386. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.13276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buts JP, De Keyser N, Sokal EM, Marandi S. Oral insulin is biologically active on rat immature enterocytes. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1997;25(2):230-232. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199708000-00020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shulman RJ, Tivey DR, Sunitha I, Dudley MA, Henning SJ. Effect of oral insulin on lactase activity, mRNA, and posttranscriptional processing in the newborn pig. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1992;14(2):166-172. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199202000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shulman RJ. Oral insulin increases small intestinal mass and disaccharidase activity in the newborn miniature pig. Pediatr Res. 1990;28(2):171-175. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199008000-00018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shamir R, Muslach M, Sukhotnik I, et al. Intestinal and systemic effects of oral insulin supplementation in rats after weaning. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50(7):1239-1244. doi: 10.1007/s10620-005-2766-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buts JP, De Keyser N, Dive C. Intestinal development in the suckling rat: effect of insulin on the maturation of villus and crypt cell functions. Eur J Clin Invest. 1988;18(4):391-398. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1988.tb01029.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Forgue-Lafitte ME, Marescot MR, Chamblier MC, Rosselin G. Evidence for the presence of insulin binding sites in isolated rat intestinal epithelial cells. Diabetologia. 1980;19(4):373-378. doi: 10.1007/BF00280523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sodoyez-Goffaux F, Sodoyez JC, De Vos CJ. Insulin receptors in the gastrointestinal tract of the rat fetus: quantitative autoradiographic studies. Diabetologia. 1985;28(1):45-50. doi: 10.1007/BF00276999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zimmerman TW, Reinprecht JT, Binder HJ. Peptide binding to intestinal epithelium: distinct sites for insulin, EGF and VIP. Peptides. 1985;6(2):229-235. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(85)90045-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Georgiev IP, Georgieva TM, Pfaffl M, Hammon HM, Blum JW. Insulin-like growth factor and insulin receptors in intestinal mucosa of neonatal calves. J Endocrinol. 2003;176(1):121-132. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1760121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ménard D, Corriveau L, Beaulieu JF. Insulin modulates cellular proliferation in developing human jejunum and colon. Biol Neonate. 1999;75(3):143-151. doi: 10.1159/000014090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shulman RJ. Effect of enteral administration of insulin on intestinal development and feeding tolerance in preterm infants: a pilot study. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2002;86(2):F131-F133. doi: 10.1136/fn.86.2.F131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shehadeh N, Simmonds A, Zangen S, Riskin A, Shamir R. Efficacy and safety of enteral recombinant human insulin for reduction of time-to-full enteral feeding in preterm infants: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Isr Med Assoc J. 2021;23(9):563-568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hughes S, Cuffe RL, Lieftucht A, Garrett Nichols W. Informing the selection of futility stopping thresholds: case study from a late-phase clinical trial. Pharm Stat. 2009;8(1):25-37. doi: 10.1002/pst.323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jitlal M, Khan I, Lee SM, Hackshaw A. Stopping clinical trials early for futility: retrospective analysis of several randomised clinical studies. Br J Cancer. 2012;107(6):910-917. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lesaffre E, Edelman MJ, Hanna NH, et al. Statistical controversies in clinical research: futility analyses in oncology-lessons on potential pitfalls from a randomized controlled trial. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(7):1419-1426. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hamilton EF, Dyachenko A, Ciampi A, Maurel K, Warrick PA, Garite TJ. Estimating risk of severe neonatal morbidity in preterm births under 32 weeks of gestation. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020;33(1):73-80. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2018.1487395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shamir R, Shehadeh N. Insulin in human milk and the use of hormones in infant formulas. Nestle Nutr Inst Workshop Ser. 2013;77:57-64. doi: 10.1159/000351384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

Statistical Analysis Plan

eTable 1. The FIT-04 Site Collaborators

eTable 2. Trial Steering Committee Members

eTable 3. Enteral Nutrition Recommendation in the Study Protocol (ESPGHAN guidelines)

eTable 4. Total Fluid (Enteral and Parenteral) and Nutritive Components

eTable 5. Prespecified Sensitivity Analysis of the Primary Outcome

eReferences

FIT-04 Study Group

Data Sharing Statement