Abstract

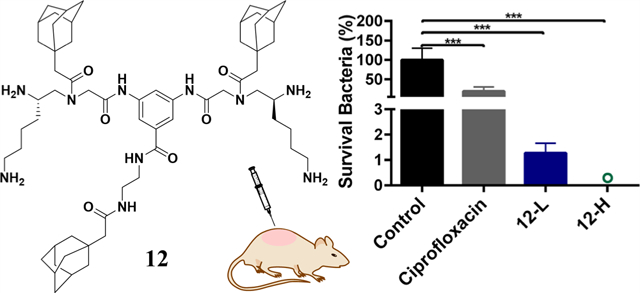

Infections caused by multidrug-resistant bacteria have emerged in recent decades, leading to escalating interest in host defense peptides (HDPs) to reverse this dangerous trend. Inspired by the modular design in bioengineering, herein we report a new class of small amphiphilic scorpionlike peptidomimetics based on this strategy. These HDP mimics show potent antimicrobial activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria without drug resistance but with a high therapeutic index. The membrane-compromising action mode was suggested to be their potential bactericidal mechanism. Pharmacodynamic experiments were conducted using a murine abscess model of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections. The lead compound 12 showed impressive in vivo therapeutic efficacy with ~99.998% (4.7log) reduction in skin MRSA burden, a significantly higher bactericidal efficiency than ciprofloxacin, and good biocompatibility. These results highlight the potential of these HDP mimics as novel antibiotic therapeutics.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

According to the 2019 Antibiotic Resistance Threats report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, antibiotic resistance posed an ever-increasing threat to global health and caused more than 35,000 deaths in the United States annually.1 Serious human health threatening strains including multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa) and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) account for substantial morbidity and mortality worldwide.1 In addition to these strains, other pandrug-resistance bacteria such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis (MRSE), Escherichia coli (E. coli), vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis (VREF), and Klebsiella pneumoniae (K. pneumoniae) are all making substantial contribution to lethal infections.2 Against this background, antimicrobial peptides, sometimes termed host defense peptides (HDPs), have been developed as a promising alternative to conventional antibiotics because of their broad antibacterial spectrum, low resistance rates, and unique antibacterial mechanism.3,4

HDPs usually exert microbial killing activity through direct membrane-disruptive effects against cells in a phospholipid-dependent manner based on their cationic and amphipathic structures.5,6 A membranous environment can induce folding of HDPs into a secondary structure, such as α-helix or β-sheet, with global segregation of cationic and lipophilic side chains (or segregation of hydrophilic and hydrophobic faces).7–11 Unfortunately, most well-known HDPs are natural macromolecular products with complex structures, and their applications are limited owing to their high cost, poor efficacy, low in vivo stability, and nonspecific toxicity to mammalian cells.12

Recently, many synthesized amphiphilic polymers with HDP-mimicking designs have been reported to have great potential in antibacterial applications.7,8,13–23 However, due to the large molecular weight, large steric hindrance induced by bulky side chains, and lack of a well-defined structure, the synthesized macromolecular antimicrobials usually depend on uncontrolled polymeric self-aggregation to achieve irregular facial amphiphilicity without helical structures. This conformation would be difficult to manipulate, suffers from a very high entropic penalty from a whole macromolecule, and is unfavorable for adequate interactions with bacterial cell membranes.7 Therefore, synthesized macromolecular antimicrobials had more difficulty in achieving good antimicrobial performance compared with small-molecular amphiphilic antimicrobials.

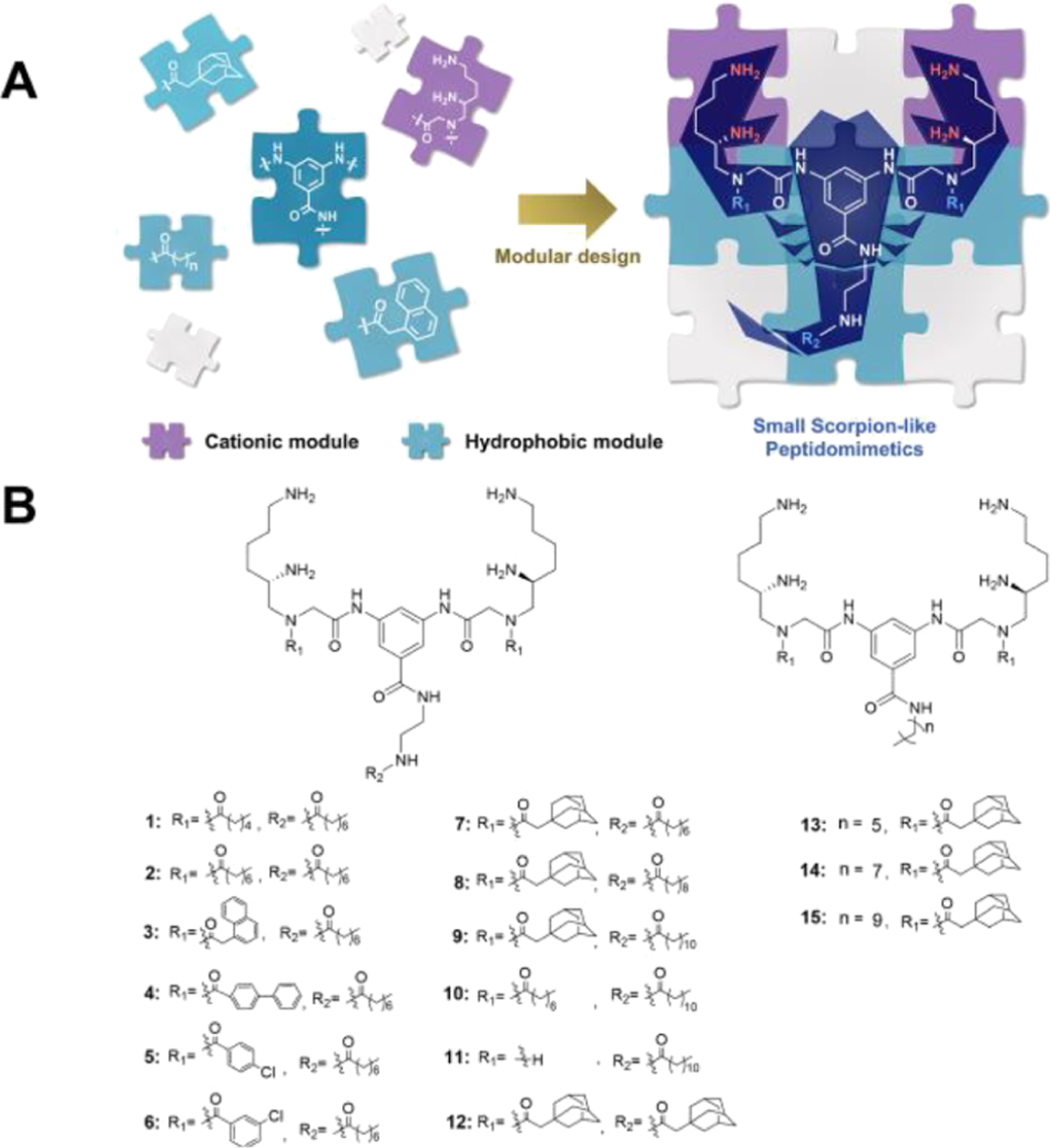

In this research study, we hypothesized that small-molecular amphiphilic peptidomimetics, which have low molecular weight, reduced steric hindrance, and thus improved conformational flexibility, could mediate enhanced interactions with bacterial cell membranes. Therefore, a new class of HDP-mimetic amphiphilic compounds based on a small-molecular scorpionlike skeleton was established (Figure 1A) using biomimetic and modular design strategies: (1) the positively charged domain of HDP mimics can electrostatically interact with anionic charges on the surfaces of bacteria, while their hydrophobic segments are helpful to insert into the hydrophobic core of the lipid bilayer.24 We found that the modes of action of HDP or HDP mimics have great similarity to the dual modes of attack of a scorpion, which seizes its prey by a pair of grasping pincers and/or stings it by a tail tipped with a venomous stinger. We predicted that HDP-mimetic amphiphilic compounds with a scorpionlike skeleton may be a promising method to simulate the predation ability of scorpion. (2) To achieve facial amphiphilicity, a modular design strategy was applied to combine hydrophobic and hydrophilic modules to obtain HDP mimics. Due to the convenience of replacing each module by groups with similar physicochemical properties, the modular design strategy could accelerate the development of antimicrobial compounds and facilitate their structure–activity relationship (SAR) studies.25

Figure 1.

Design of the peptidomimetics. (A) Schematic illustrations for the structure of small scorpionlike HDP mimics, where their cationic modules acted as the grasping pincers of the scorpionlike skeleton to seize bacterial membranes and their hydrophobic modules constituted the body and tail of the scorpionlike molecule to facilitate membrane insertion. (B) General structures of peptidomimetics.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Design and Antimicrobial Activity of Peptidomimetics.

As our previous studies demonstrated that cationic γ-AApeptide building blocks can efficiently bind to bacterial membranes,26–28 we have designed the framework of a dimeric positively charged γ-AApeptide building block (cationic module shown in Figure 1A)29 conjugated with 3,5-diaminobenzoic acid, providing four cationic amines as the “grasping pincers of scorpion” and three alkyl lipophilic moieties as the “tail” (Figure 1B). Our recent dimeric design has led to potent antibiotic agents that mimic HDPs.2,12 However, the modification of the molecular scaffold for the adjustment of amphiphilicity is not straightforward. In the current study, we believe that dimeric γ-AApeptides bearing a hydrophobic portion in the center of the molecular scaffold could lead to manipulation of amphiphilicity at ease, thereby resulting in more potent and selective HDP-mimicking agents. In these derivatives, the modification was made with various alkyl substitutions, while cationic groups were not changed. Briefly, bulky alkyl groups with different sizes and linear alkyl groups with diverse lengths were explored to optimize for the best activity.

To evaluate the antibiotic activity of the compounds against Gram-positive bacteria and Gram-negative bacteria, a panel of six strains, including MRSA, MRSE, VREF, E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and P. aeruginosa, was selected to determine the minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs). Ciprofloxacin, a common marketed antibiotic, was tested at the same time as a positive control. Hemolysis, which represents the degree of human blood being lysed by candidates, was also evaluated using HC50 values. To our delight, many compounds were active against these strains and most of the compounds had HC50 values exceeding the tested concentration, 250 μg/mL. Since the cationic groups have not been changed in compounds 1–15, it was quite straightforward to establish the SAR. To begin with, compounds 1 and 2, which only have linear hydrophobic groups, were synthesized and tested. Compound 1 did not show activity up to 25 μg/mL against MRSA and E. coli. After an increase in the length of fatty acids on the R1 position from hexanoic acid to octanoic acid, compound 2 started to exhibit potent activity against all strains except for K. pneumoniae. This result indicated that when keeping octanoic acid unchanged on the R2 position, the R1 position should have at least eight carbons to provide sufficient hydrophobic interaction with the bacterial cell membranes. We also explored a few other hydrophobic groups on R1 through acylation with 2-naphthoic acid (compound 3), [1,1′-biphenyl]-4-carboxylic acid (compound 4), 4-chlorobenzoic acid (compound 5), 3-chlorobenzoic acid (compound 6), and 1-adamantaneacetic acid (compound 7). It is interesting to note that compound 3 had less potent activity toward most bacterial strains than 2 bearing a linear hydrophobic group. However, 3 has a MIC of 4.5 μg/mL against K. pneumoniae, while 2 showed no inhibitory activity, which may imply that both hydrophobicity and the nature of the group are all important for antimicrobial activity. Subsequent exploration showed that a more flexible and longer biphenyl group (4) led to a better activity than 3 for most of the strains, as seen for the MICs against three Gram-positive bacterial strains being decreased twofold or more, albeit its activity against K. pneumoniae was lost. Then, we considered chlorobenzoic acid to assess the effect of using smaller bulky lipophilic groups on R1. Small hydrophobic groups on R1 (5 and 6) completely abolished the antibiotic activity, demonstrating once again that groups of sufficient hydrophobicity and bulkiness are necessary for the maximum broad antibacterial activity. It is known that adamantanyl group is a commonly used alkyl substitute to improve the antibacterial activity.12,30 As such, compound 7 was designed and synthesized. As expected, 7 turned out to be the best compound among 1–7. Thus, 7 was chosen as the lead compound for further modification. Switching octanoic acid to decanoic acid and dodecanoic acid on position R2 led to compounds 8 and 9, respectively. However, both compounds were less active in contrast to 7. This result suggested that increasing the carbon number of alkyl chain on the R2 position was not helpful in improving the activity. Indeed, a similar trend was observed when comparing the activity of 2 to 10. Also, it is expected that 11, without a R1 group, exhibited a worse activity than 10, again demonstrating the importance of R1 being a hydrophobic group. Interestingly, when replacing the linear lipophilic chain with a bulky adamantanyl group (compound 12), the best activity against all strains was reached.

Compounds 13, 14, and 15 with alkyl amines directly conjugated with 3,5-diaminobenzoic acid were also prepared. With the tail length increasing from 6 carbons to 10 carbons, the overall activity against six bacterial strains decreased. It is worth noting that compounds 14 and 15 were not as active as compounds 7 and 8, although 14 and 15 bear the same alkyl tails as compounds 7 and 8. This phenomenon provided the evidence that the linker, ethane-1,2-diamine, coupled between 3,5-diaminobenzoic acid and the R2 group, benefited the antibacterial effect. Compound 12 had a HC50 value of 250 μg/mL, whereas the therapeutic index (HC50/MIC against MRSA) was 125. This result indicated that these compounds were unlikely to lyse human blood cells when being used at MIC concentrations. Interestingly, the compounds without the ethane-1,2-diamine linker, compounds 14 and 15, had lower therapeutic index than 7 and 8. As known, increasing the hydrophobicity will lead to an increased hemolytic activity. Compounds 7 and 14 showed retention times of 21 mins and 23.5 mins on a high-performance liquid chromatograph (HPLC), respectively. Compounds 8 and 15 showed retention times of 22.5 mins and 25 mins, respectively. Therefore, ethane-1,2-diamine was an effective linker that decreased the hemolytic activity of a compound while increasing its antibiotic activity.

The salt tolerance of antibiotics is a critical parameter that maintains the antimicrobial activity of peptides for biological applications.31 To investigate whether the antimicrobial activity of compounds is impacted by salt or not, MICs of the lead compound 12 against all six strains were determined in a tryptic soy broth (TSB) in the presence of different salts. As shown in Table 2, monovalent (Na+ and K+) and divalent (Ca2+) cations were added into the TSB medium. All MIC values remained the same or increased slightly twofold. It is therefore concluded that the antimicrobial activity of compound 12 did not change significantly in the presence of some physiological salts, indicating its high salt tolerance.

Table 2.

MICs of Compound 12 in the Presence of Physiological Salts

| MIC (μg/mL) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gram-positive | Gram-negative | |||||

| compound # | MRSA | MRSE | VREF | E. coli | P. aeruginosa | K. pneumoniae |

| 12 (Na+ and K+) | 4.5 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| 12 (Ca2+) | 2 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 19 | 9 |

Time-Kill Kinetics Study.

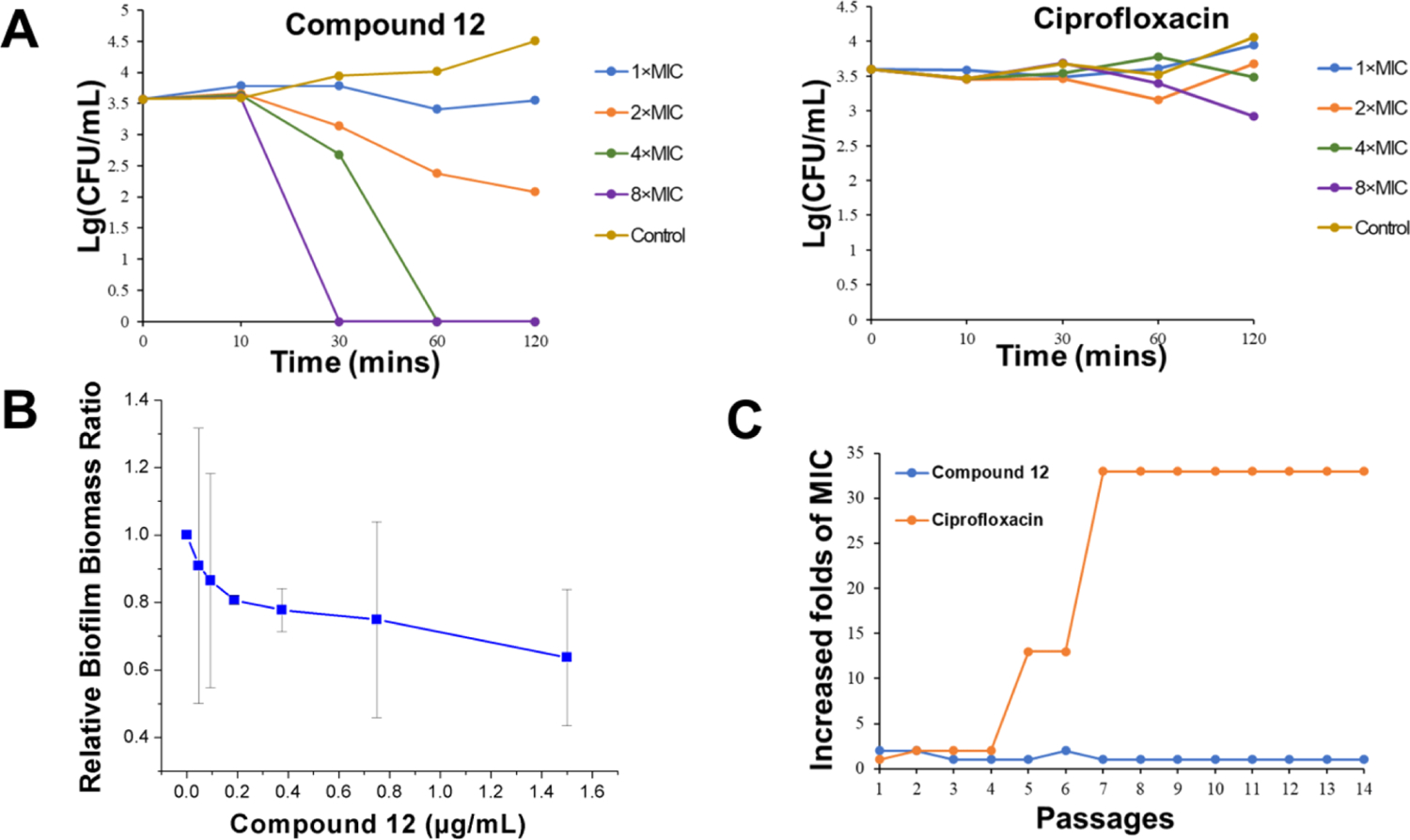

The lead compound 12 was studied regarding its efficacy of eradicating MRSA by measuring the time-kill kinetics. Ciprofloxacin was tested at the same time. As shown in Figure 2A, at a concentration of 8 μg/mL (4 × MIC), compound 12 could eliminate all MRSA cells within 60 mins. Increasing the concentration to 16 μg/mL (8 × MIC) reduced the time to as short as 30 mins. Although bacteria were not totally eradicated at 1 × MIC and 2 × MIC concentrations, the decreasing tendency was obvious when compared with a negative control. However, ciprofloxacin did not show a noticeable MRSA eliminating trend even at an 8 × MIC concentration within 2 h, delineating its different mechanism in contrast to 12, which is analogous to HDPs. However, the time-kill kinetics of compound 12 against E. coli were not as efficient as ciprofloxacin (Figure S1).

Figure 2.

Time-kill kinetics study, biofilm inhibition, and drug resistance of compound 12. (A) Time-kill kinetic curves of compound 12 and ciprofloxacin. Controls were untreated MRSA. (B) MRSA biofilm inhibition by compound 12. (C) Propensity of developing drug resistance of compound 12 and ciprofloxacin against MRSA.

Biofilm Inhibition.

A bacterial biofilm plays an active role in producing drug resistance and is strongly associated with the majority of bacterial infections.32 Therefore, the inhibitory effect of compound 12 on MRSA biofilm formation was evaluated. As shown in Figure 2B, with the increase of the compound concentration, a decreasing trend of biofilm formation was observed. Nearly 40% biofilm was inhibited at 1.5 μg/mL of compound 12. The E. coli biofilm inhibition effect of compound 12 could also be observed at low concentrations (Figure S2).

Drug Resistance Study.

Since the emergence of penicillin-resistant bacteria after only few years of penicillin discovery, it has been widely acknowledged that drug resistance is becoming a global threat.33 Therefore, it is significant to assess the potential resistance development of new biocides. Figure 2C shows that the MIC values of compound 12 for MRSA did not change after 14 passages, whereas a 33-fold increase was observed in the case of ciprofloxacin. Similar results were also observed for E. coli (Figure S3). Thus, this result indicated that this type of antibiotic made it hard for bacteria to develop drug resistance.

Antimicrobial Mechanism.

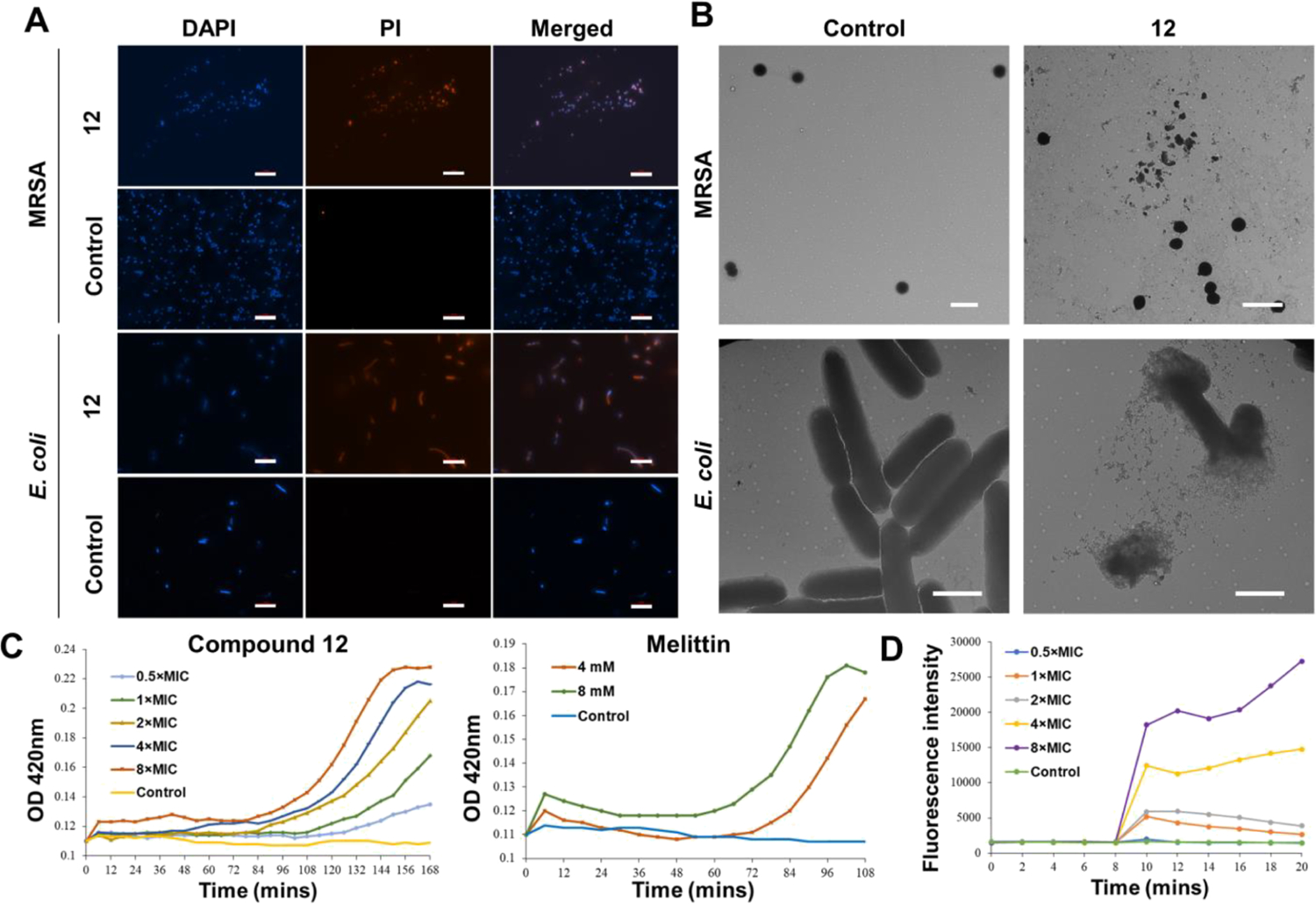

To confirm that the designed HDP mimics also act through a membrane-interrupting mechanism, we conducted a few experiments. Two dyes, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) and propidium iodide (PI), were first applied to carry out fluorescence microscopy. PI is not membrane-permeable. Therefore, it is commonly used to stain dead or injured cells. In contrast, DAPI can pass through the bacterial membrane regardless of its integrity. MRSA and E. coli were stained with both dyes after being treated or untreated with compound 12. As shown in Figure 3A, the negative control of MRSA and E. coli had blue color in the DAPI channel, while no fluorescence was observed in the PI channel. This result indicates that bacteria were alive in the negative control. For bacteria treated with compound 12, not only blue fluorescence was observed in the DAPI channel but red fluorescence was also observed in the PI channel, demonstrating that the bacterial membranes have been compromised by compound 12.

Figure 3.

Evidence for the membrane-interrupting antimicrobial mechanism. (A) Fluorescence microscopy of MRSA and E. coli treated or untreated with 6 μg/mL of compound 12 for 2 h. Scale bar =10 μm. Controls were bacteria without treatment. (B) Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of MRSA and E. coli treated or untreated with 6 μg/mL of compound 12. Controls were bacteria without treatment. Scale bar is 2 μm. (C) Inner membrane permeability of compound 12 and melittin against E. coli. The control was untreated E. coli. (D) Cytoplasmic membrane potential variation of MRSA. The control was untreated MRSA.

As TEM microscopy is a direct way to visualize the bacterial membrane,2 imaging of MRSA and E. coli after being incubated with compound 12 was further conducted (Figure 3B). Obviously, without the treatment of compound 12, MRSA and E. coli had an intact membrane. After incubation with compound 12 at a concentration of 6 μg/mL, both MRSA and E. coli lost their membrane integrity (Figure 3B).

It is known that the o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (ONPG) hydrolysis assay is also a common method to detect whether the inner membrane of Gram-negative bacteria is intact or not. After membrane destabilization, ONPG interacts with the cytoplasmic enzyme β-galactosidase to form o-nitrophenol, which can be measured at 420 nm.34 Therefore, this assay was performed on E. coli to further explore the inner membrane interruption effect of compound 12, with melittin being included as the positive control. As shown in Figure 3C, compound 12 exhibited effective concentration- and time-dependent inner membrane interruption. Interestingly, the OD420 value also showed an increasing trend when E. coli was treated with compound 12 at a 0.5 × MIC concentration, which indicated the effective inner membrane-interrupting ability of compound 12.

The integrity of the cytoplasmic membrane of Gram-positive bacteria was evaluated using a dye, 3,3′-dipropylthiadicarbocyanine iodide [DiSC3(5)].35 Generally, this dye enters into the bacterial cells and aggregates as a nonfluorescent conjugation. Once the cytoplasmic membrane is disturbed by biocides, the increasing fluorescence will be detected due to the formation of a dye monomer.36 As shown in Figure 3D, MRSA treated with compound 12 was observed at different concentrations. Bacteria mixed with 0.5 × MIC showed a similar fluorescence intensity trend as the negative control, which was untreated MRSA. However, when the concentration changed from 1 × MIC to 8 × MIC, the increase of the fluorescence intensity was dose-dependent.

Effectiveness Evaluation Using a Mouse Model.

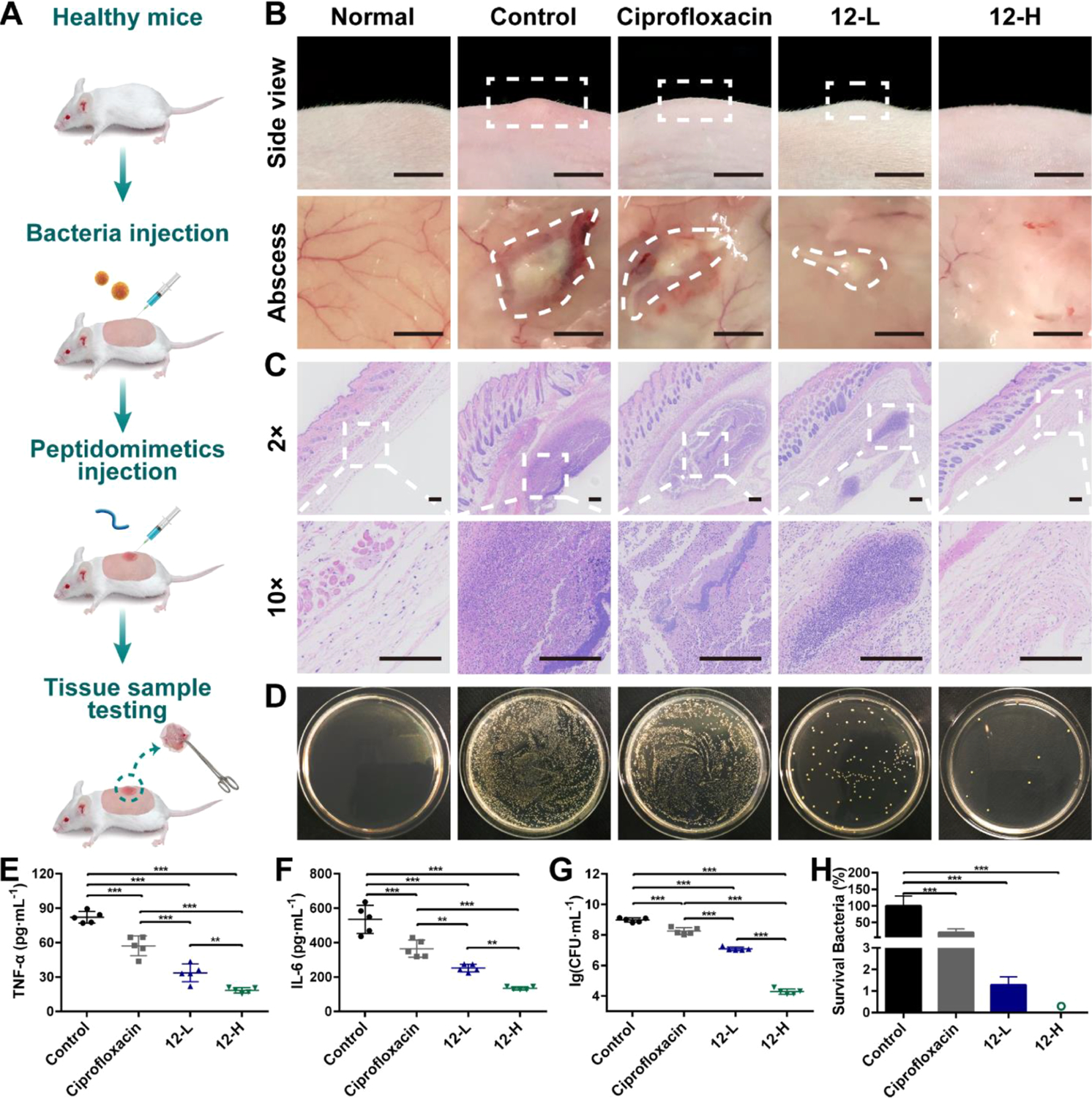

As compound 12 demonstrated the most potent and broad-spectrum activity in vitro, its in vivo performance was next assessed using a murine abscess model of MRSA infections following a reported method.37,38 Ciprofloxacin (5 mg/mL) was used as the positive control. Low-dose groups (12-L) were administered with 100 μL of 0.5 mg/mL compound 12 solution, while high-dose groups (12-H) were administered with 100 μL of 5 mg/mL compound 12 solution. As shown in Figure 4B, there is a marked swelling on the dorsal skin surface and skin abscess in the subcutaneous tissues of the control mice, indicating the formation of skin abscess after 48 h. Notably, no visual lesions were observed in the mice that were treated with high doses of compound 12, whereas visible abscess or erythema still can be observed in the subcutaneous tissues of mice treated with ciprofloxacin or low doses of compound 12. As shown in Figure 4C, hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) histological examinations showed massive infiltration with acute and chronic inflammatory cells, primarily neutrophils, in the subcutaneous connective tissues of control mice. Encouragingly, the inflammatory cells were reduced after being treated with ciprofloxacin and even a low dose of compound 12. Moreover, the skin sections of mice treated with a high dose of compound 12 were nearly identical to those of healthy mice.

Figure 4.

Effectiveness evaluation using a mouse model. (A) Schematic of the experiment protocol for the murine abscess model of MRSA infections. (B) Digital photographs of MRSA infection sites with various treatments 48 h after infection. Scale bar is 0.5 cm. (C) Histological photographs of infected skin that received various treatments. Scale bar is 200 μm. (D) Images of MRSA colonies cultured from the homogenate of infected skin after appropriate dilution. Levels of (E) tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) in the infected skin and (F) interleukin-6 (IL-6) in the infected skin. (G) Microbial burden of each group after 48 h of MRSA injection. (H) Bacterial survival of each group after 48 h of MRSA injection. “o” represents 0.002%. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. 12-L represents compound 12 at a low concentration (100 μL, 0.5 mg/mL). 12-H represents compound 12 at a high concentration (100 μL, 5 mg/mL). The concentration of ciprofloxacin is 5 mg/mL.

Compared with the control group, treatment with both ciprofloxacin and compound 12 had significantly decreased MRSA-induced production of proinflammatory cytokines including TNF-α (p < 0.001) and IL-6 (p < 0.001) and a high dose of compound 12 exhibited the best therapeutic effect (p < 0.001 vs compound 12 and p < 0.001 vs ciprofloxacin) (Figure 4E,F). This result may explain the better in vivo performance of compound 12 than that of ciprofloxacin. The quantitative assessment of microbial burden in tissues revealed that ciprofloxacin and compound 12-L groups achieved, respectively, 81.1 and 98.7% (0.7 and 1.9log) reduction of MRSA, while compound 12-H treatment groups achieved 99.998% (4.7log) reduction of bacteria (Figure 4D,G,H). To the best of our knowledge, there are few studies demonstrating that HDPs or HDP mimics can achieve a ~99.998% reduction in skin bacterial load after a single treatment.39,40 Furthermore, the number of bacteria remaining on the skin of compound 12 group was ~9100 times lower than those remaining on ciprofloxacin-treated mice (p < 0.001). The impressive antimicrobial activities make compound 12 a promising alternative to conventional antibiotics in clinical applications.

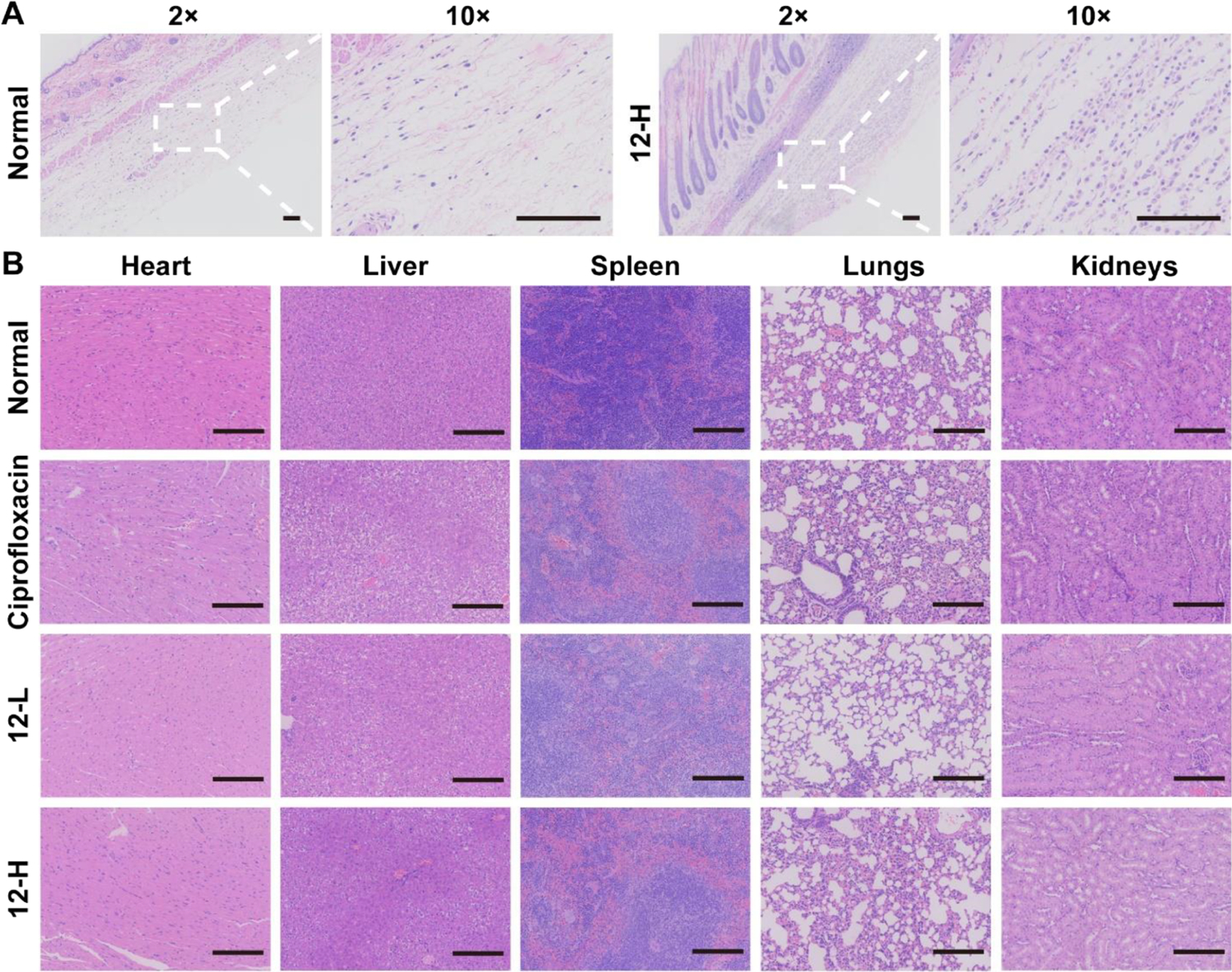

Biocompatibility Evaluation Using a Mouse Model.

To demonstrate the in vivo biocompatibility, the local and systemic toxicity of compound 12 was evaluated by examining the pathological changes of the mice in the skin, heart, liver, spleen, lungs, and kidneys. As shown in Figure 5A, topical application of compound 12 showed a good skin compatibility profile in mice. It is worth noting that ciprofloxacin treatment induced liver injury characterized by moderate cellular degeneration, but no obvious histopathological abnormalities or lesions to major organs were observed in the compound 12 treatment group under the same experimental conditions (Figure 5B). Hence, compound 12 may be a promising candidate to be investigated as a safe antimicrobial agent.

Figure 5.

Biocompatibility evaluation using a mouse model. (A) Representative H&E-stained sections from mouse skin. (B) Representative H&E-stained sections from major organs after various treatments. Scale bar is 200 μm. 12-L represents compound 12 at a low concentration (100 μL, 0.5 mg/mL). 12-H represents compound 12 at a high concentration (100 μL, 5 mg/mL). The concentration of ciprofloxacin is 5 mg/mL.

CONCLUSIONS

Battle against antibiotic resistance that we are facing is still uphill currently. Many macromolecular antimicrobials, based on the HDP-mimicking design, have already been developed with high activity and low potential of inducing drug resistance against multidrug-resistance bacteria. These compounds act via compromising the bacterial membrane by their facial amphiphilicity, which is difficult to control due to the unpredictable self-aggregation.7,41 Cytotoxicity and hemolysis of human blood cells remain another issue for these antimicrobials. Considering the many advantages of small-molecular drug development, such as lower molecular weight and easier administration, small-molecular antimicrobials could be an alternative solution to the drug resistance threat.

In this work, a new class of small scorpionlike peptidomimetics with excellent antimicrobial activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria was developed via biomimetic and modular design strategies. These molecules also exhibited persistent bacterial killing activity in the presence of physiological salts. Biofilm formation could be inhibited by these molecules at a low concentration. Eradicating bacteria with low concentrations in a short time without developing drug resistance and hemolysis is another advantage of these peptidomimetics. Mechanism studies revealed their potential membrane-interrupting action mode. Significantly, the lead compound exhibited a highly impressive in vivo anti-infection activity and high in vivo biocompatibility, which made it a potential candidate for clinical applications. On the basis of the efficacy of the lead compound 12, the antimicrobial peptidomimetics based on the small-molecular scorpionlike skeleton are expected to serve as promising broad-spectrum antimicrobial agents in the treatment of drug-resistant infections. It should be noted that although the small scorpionlike peptidomimetic design is successful, only a limited number of hydrophobic R1 and R2 groups and γ-AApeptide building blocks were explored to demonstrate the design strategy. The comprehensive study and exploration of other R1 and R2 groups, although out of the scope of the current report, could lead to antibiotic agents with a better potent antimicrobial activity and a higher therapeutic index to combat drug resistance.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

General Information.

Solvents and other reagents were purchased from Fisher Scientific, Sigma-Aldrich, TCI America, or Chem-Impex and were used directly. All final products were purified using a Waters Breeze 2 HPLC system and lyophilized using a Labconco lyophilizer. Analytical HPLC (1 mL/min flow, 5–100% linear gradient of acetonitrile with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and water with 0.1% TFA in water over 40 min) was conducted. The nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra were obtained using a Bruker Avance NEO 400 instrument. High-resolution mass spectra of compounds were obtained using an Agilent Technologies 6540 UHD accurate-mass Q-TOF LC/MS spectrometer. A BioTek multimode microplate reader Synergy H4 was used in antimicrobial assays and mechanism of action studies. MRSA (ATCC 33591), MRSE (RP62A), VREF (ATCC 700802), E. coli (ATCC 25922), K. pneumoniae (ATCC 13383), and P. aeruginosa (ATCC 27853) were applied in antimicrobial assays. Animal experiments were performed according to the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Sun Yat-Sen University (approved protocol number SYSU-IACUC-2019-000203), and all animal care procedures were performed according to the Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Healthy female ICR mice were obtained from the Animal Center of Sun Yat-Sen University. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits were purchased from Dakewe in Shenzhen, China.

Synthesis of the Compounds.

Synthesis of 3,5-bis((((9H-fluoren-9-yl)methoxy)carbonyl)amino)benzoic acid. A volume of 1 g (6.58 mmol) of 3,5-diaminobenzoic acid was suspended in 50 mL of THF/H2O = 1:1 solution. With stirring, 3.49 g (32.9 mmol) of Na2CO3 and 3.75 g (14.48 mmol) of Fmoc-Cl were added into the above solution and then the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight. A 1 M HCl solution was added to quench the reaction, and the product was extracted with ethyl acetate (EA, 100 mL × 3 times). After being dried with sodium sulfate, the EA solution was evaporated, and a solid crude product was left. To purify the crude product, dichloromethane (DCM) was added to it and then sonicated. The product (3.52 g) was obtained after filtering and washing with DCM. The yield was 90%. Then, 500 mg (0.84 mmol) of 3,5-bis((((9H-fluoren-9-yl)methoxy)carbonyl)amino)benzoic acid was dissolved in 50 mL of dimethylformamide (DMF) solution. A volume of 382 mg (1.00 mmol) of 1-[bis(dimethylamino)methylene]-1H-1,2,3-triazolo-[4,5-b]pyridinium 3-oxide hexafluorophosphate (HATU) and 173 μL (1.00 mmol) of N,N-diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA) was then added into the above solution separately. Following this, 177 mg (1.00 mmol) of tert-butyl (2-aminoethyl)carbamate was added into the mixture. After the completion of addition, the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 2 h. 1 M HCl (150 mL) was added into the reaction and then EA was used to extract the product. Silica gel chromatography was employed to purify this product. An intermediate (506 mg) was obtained with a yield of 82%. Then, at room temperature, 15 mL of DCM:TFA = 1:1 mixture was added into the intermediate to cleave the Boc protection group. The reaction lasted for 1.5 h. After the reaction was complete, TFA and DCM were evaporated and the crude product was directly used for the next step without purification. HATU (312 mg, 0.82 mmol) and DIPEA (141 μL, 0.82 mmol) were applied as coupling reagents to conjugate them with 118 mg (0.82 mmol) of octanoic acid following the same conjugation reaction conditions in the first step. After chromatography purification, 461 mg of product was obtained. The yield was 88%. Finally, 20 mL of diethanolamine (DEA):CH3CN = 1:1 was used to cleave the Fmoc protection group to obtain 3,5-diamino-N-octylbenzamide. 3,5-diamino-N-(2-aminoethyl)benzamide conjugated with other fatty acids was obtained following the same procedure.

γ-AApeptide building blocks (cationic module shown in Figure 1) with different R1 groups were synthesized using a method reported before.29 For compound 1, a γ-AApeptide building block (195 mg, 0.32 mmol) with a side chain of hexanoic acid in 20 mL of DMF solution was added to HATU (150 mg, 0.40 mmol) and DIPEA (69 μL, 0.4 mmol) followed by the addition of 51 mg (0.16 mmol) of 3,5-diamino-N-(2-octanamidoethyl)benzamide for a 2 h reaction at room temperature. After being quenched by 1 M HCl, EA was used to extract the product (50 mL× 3 times), and the organic layer was dried with sodium sulfate. The product (143 mg) with a yield of 59% was obtained after column purification. Then, the product was treated with DEA:CH3CN = 1:1 and TFA:DCM = 1:1, respectively, to cleave all protection groups. An HPLC was used to purify compound 1, and 55 mg was obtained. Other compounds were prepared using the same method. All compounds have purity >95%.

tert-Butyl(S)-(2-((((9H-Fluoren-9-yl)Methoxy)Carbonyl)Amino)-6-((tert-Butoxycarbonyl)Amino)Hexyl) Glycinate.

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 7.88–7.90 (d, J = 8 Hz, 2H), δ 7.69–7.71 (d, J = 8 Hz, 2H), δ 7.40–7.44 (t, J = 16 Hz, 2H), δ 7.31–7.35 (t, J = 16 Hz, 2H), δ 7.05–7.07 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), δ 6.73–6.76 (t, J = 12 Hz, 1H), δ 4.28–4.30 (d, J = 8 Hz, 2H), δ 4.20–4.23 (t, J = 12 Hz, 1H), δ 3.42–3.47 (q, J = 20 Hz, 1H), δ 3.19 (s, 2H), δ 2.86–2.91 (q, J = 20 Hz, 2H), δ 1.43–1.49 (m, 1H), δ 1.41 (s, 9H), δ 1.37 (s, 9H), δ 1.25–1.29 (m, 2H), δ 1.16–1.20 (t, J = 16 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 172.00, 156.44, 156.03, 144.45, 141.21, 128.05, 127.49, 125.69, 120.57, 80.51, 77.75, 65.58, 53.11, 51.57, 51.23, 47.30, 32.38, 29.92, 28.74, 28.24, 23.31. HRMS (ESI) C32H45N3O6 [M + Na]+ calcd = 590.3206; found [M + Na]+ = 590.3218.

Di(9H-Fluoren-9-yl)(5-((2-((tert-Butoxycarbonyl) Amino)Ethyl)-Carbamoyl)-1,3-Phenylene)Dicarbamate.

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 9.91 (s, 2H), δ 8.33–8.36 (t, J = 14 Hz, 1H), δ 7.91–7.93 (d, J = 8 Hz, 4H), δ 7.88 (s, 1H), δ 7.77–7.78 (d, J = 4 Hz, 4H), δ 7.56 (s, 2H), δ 7.42–7.46 (t, J = 16 Hz, 4H), δ 7.34–7.38 (t, J = 16 Hz, 4H), δ 6.86–6.88 (t, J = 8 Hz, 1H), δ 4.44–4.45 (d, J = 4 Hz, 4H), δ 4.30–4.34 (t, J = 16 Hz, 2H), δ 3.25–3.29 (q, J = 16 Hz, 2H), δ 3.06–3.11 (q, J = 20 Hz, 2H), δ 1.38 (s, 9H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 167.18, 156.14, 153.87, 144.22, 141.25, 139.88, 136.59, 128.20, 127.61, 125.70, 120.68, 112.47, 78.17, 66.25, 47.03, 28.69. HRMS (ESI) C44H42N4O7 [M + H]+ calcd = 739.3132; found [M + H]+ = 739.3147.

N,N′-(((5-((2-Octanamidoethyl)Carbamoyl)-1,3-Phenylene)Bis-(Azanediyl))Bis(2-Oxoethane-2,1-Diyl))Bis(N-((S)-2,6-Diaminohexyl)Hexanamide) (1).

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 10.52–10.55 (m, 2H), δ 8.47–8.49 (m, 1H), δ 8.06–8.17 (m, 3H), δ 7.75–7.94 (m, 13H), δ 4.22–4.33 (dd, J = 20 Hz, 2H), δ 4.02–4.18 (dd, J = 16 Hz, 2H), δ 3.35–3.38 (m, 3H), δ 3.26–3.29 (m, 2H), δ 3.17–3.21 (m, 2H), δ 2.75–2.80 (d, J = 20 Hz, 4H), δ 2.34–2.46 (m, 1H), δ 2.19–2.22 (t, J = 12 Hz, 2H), δ 2.03–2.07 (t, J = 12 Hz, 2H), δ 1.41–1.54 (m, 18H), δ 1.21–1.28 (m, 16H), δ 0.82–0.87 (m, 9H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 174.99, 173.73, 173.01, 169.79, 168.44, 166.86, 166.72, 159.03, 158.70, 139.31, 136.51, 136.43, 114.12, 113.20, 52.12, 51.14, 50.46, 49.85, 49.70, 36.55, 31.37, 30.26, 29.06, 28.92, 27.20, 26.10, 24.70, 24.43, 23.03, 21.97, 15.05, 13.78, 12.88. HRMS (ESI) C45H82N10O6 [M + H]+ calcd = 859.6497; found [M + H]+ = 859.6491.

N,N′-(((5-((2-Octanamidoethyl)Carbamoyl)-1,3-Phenylene)Bis-(Azanediyl))Bis(2-Oxoethane-2,1-Diyl))Bis(N-((S)-2,6-Diaminohexyl)Octanamide) (2).

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 10.51–10.54 (m, 2H), δ 8.46–8.49 (m, 1H), δ 8.05–8.15 (3H), δ 7.71–7.95 (m, 13H), δ 4.21–4.32 (dd, J = 16 Hz, 2H), δ 4.02–4.18 (dd, J = 16 Hz, 1H), δ 3.36–3.46 (m, 3H), δ 3.26–3.29 (m, 2H), δ 3.18–3.20 (m, 2H), δ 2.73–2.8 (m, 4H), δ 2.36–2.44 (m, 1H), δ 2.18–2.22 (t, J = 16 Hz, 4H), δ 2.03–2.07 (t, J = 16 Hz, 2H), δ 1.39–1.52 (m, 18H), δ 1.20–1.26 (m, 24H), δ 0.79–0.86 (m, 9H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 174.99, 173.73, 173.01, 169.79, 168.44, 166.86, 166.72, 159.03, 158.70, 139.31, 136.51, 136.43, 114.12, 113.20, 52.12, 51.14, 50.46, 49.85, 35.89, 32.63, 32.36, 31.62, 31.37, 31.32, 30.26, 29.91, 29.06, 28.92, 27.20, 25.69, 24.70, 24.43, 22.53, 22.46, 21.97, 14.41, 14.37, 14.32. HRMS (ESI) C49H90N10O6 [M + H]+ calcd = 915.7123; found [M + H]+ = 915.7115.

N,N′-(((5-((2-Octanamidoethyl)Carbamoyl)-1,3-Phenylene)Bis-(Azanediyl))Bis(2-Oxoethane-2,1-Diyl))Bis(N-((S)-2,6-Diaminohexyl)-2-(Naphthalen-1-yl)Acetamide) (3).

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 10.64–10.69 (d, J = 20 Hz, 1H), δ 10.51–10.56 (d, J = 20 Hz, 1H), δ 8.50–8.52 (m, 1H), δ 8.24–8.33 (m, 2H), δ 7.92–8.07 (m, 9H), δ 7.76–7.84 (m, 10H), δ 7.41–7.53 (m, 6H), δ 7.29–7.31 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), δ 4.48–4.61 (m, 2H), δ 4.23–4.37 (m, 2H), δ 4.06–4.18 (m, 3H), δ 3.72–3.81 (m, 2H), δ 3.38–3.41 (m, 2H), δ 3.17–3.32 (m, 5H), δ 2.73–2.77 (m, 4H), δ 2.03–2.07 (t, J = 16 Hz, 2H), δ 1.38–1.67 (m, 14H), δ 1.15–1.24 (m, 8H), δ 0.81–0.84 (t, J = 12 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 173.13, 171.97, 169.74, 168.45, 166.93, 159.00, 158.67, 139.38, 136.59, 133.74, 132.90, 132.76, 132.69, 132.61, 128.76, 128.45, 127.72, 126.35, 126.13, 126.01, 125.82, 125.04, 118.68, 114.34, 52.55, 51.66, 50.75, 50.07, 49.74, 35.89, 31.61, 30.30, 30.04, 29.06, 28.91, 27.25, 27.17, 25.69, 22.52, 22.03, 21.97, 14.41. HRMS (ESI) C57H78N10O6 [M + H]+ calcd = 999.6184; found [M + H]+ = 999.6175.

N,N′-(((5-((2-Octanamidoethyl)Carbamoyl)-1,3-Phenylene)Bis-(Azanediyl))Bis(2-Oxoethane-2,1-Diyl))Bis(N-((S)-2,6-Diaminohexyl)-[1,1′-Biphenyl]-4-Carboxamide) (4).

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 10.25 (s, 1H), δ 8.41–8.49 (m, 1H), δ 7.93–8.06 (m, 7H), δ 7.78–7.81 (m, 6H), δ 7.71–7.73 (d, J = 8 Hz, 4H), δ 7.65–7.67 (d, J = 8 Hz, 4H), δ 7.36–7.55 (m, 9H), δ 4.15–4.44 (m, 4H), δ 3.67–3.70 (m, 4H), δ 3.17–3.26 (m, 5H), δ 2.79–2.83 (m, 3H), δ 2.02–2.09 (m, 2H), δ 1.54–1.64 (m, 6H), δ 1.43–1.49 (m, 7H), δ 1.18–1.21 (m, 9H), δ 0.75–0.82 (t, J = 28 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 173.31, 173.04, 168.14, 158.57, 141.81, 139.55, 139.18, 135.27, 129.50, 128.75, 128.46, 127.91, 127.34, 127.22, 126.95, 113.91, 112.94, 53.95, 49.68, 35.89, 31.60, 30.47, 29.05, 28.91, 27.25, 25.69, 22.52, 22.00, 14.40. HRMS (ESI) C59H78N10O6 [M + H]+ calcd = 1023.6184; found [M + H]+ = 1023.6175.

N,N′-(((5-((2-Octanamidoethyl)Carbamoyl)-1,3-Phenylene)Bis-(Azanediyl))Bis(2-Oxoethane-2,1-Diyl))Bis(4-Chloro-N-((S)-2,6-Diaminohexyl)Benzamide) (5).

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 10.15 (s, 1H), δ 8.36–8.46 (m, 1H), δ 7.94–7.98 (m, 5H), δ 7.85–7.88 (d, J = 12 Hz, 2H), δ 7.72–7.74 (m, 6H), δ 7.57–7.58 (d, J = 4 Hz, 1H), δ 7.50–7.53 (t, J = 12 Hz, 1H), δ 7.39–7.45 (m, 6H), δ 4.18–4.30 (dd, J = 20 Hz, 1H), δ 4.01–4.13 (q, J = 48 Hz, 3H), δ 3.56–3.57 (m, 4H), δ 3.18–3.22 (m, 3H), δ 3.10–3.13 (m, 2H), δ 2.59–2.75 (m, 4H), δ 1.96–2.00 (t, J = 16 Hz, 2H), δ 1.46–1.57 (m, 6H), δ 1.13–1.41 (m, 7H), δ 1.12–1.14 (m, 9H), δ 0.73–0.77 (t, J = 16 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 173.06, 172.56, 167.96, 166.33, 163.76, 158.94, 158.61, 139.11, 137.13, 135.18, 134.87, 131.15, 129.99, 129.13, 128.89, 113.96, 110.68, 53.82, 49.61, 35.90, 31.61, 30.42, 29.85, 29.07, 28.92, 27.23, 25.70, 22.52, 21.99, 21.76, 14.41. HRMS (ESI) C47H68Cl2N10O6 [M + H]+ calcd = 939.4779; found [M + H]+ = 939.4768.

N,N′-(((5-((2-Octanamidoethyl)Carbamoyl)-1,3-Phenylene)Bis-(Azanediyl))Bis(2-Oxoethane-2,1-Diyl))Bis(3-Chloro-N-((S)-2,6-Diaminohexyl)Benzamide) (6).

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 10.23 (s, 1H), δ 8.42–8.48 (m, 1H), δ 8.01–8.09 (m, 5H), δ 7.93–7.96 (d, J = 12 Hz, 2H), δ 7.84–7.88 (m, 6H), δ 7.64 (s, 1H), δ 7.56 (s, 2H), δ 7.51–7.53 (d, J = 8 Hz, 2H), δ 7.42–7.46 (t, J = 16 Hz, 2H), δ 7.36–7.37 (d, J = 4 Hz, 2H), δ 4.30–4.37 (t, J = 28 Hz, 1H), δ 4.08–4.21 (dd, J = 16 Hz, 3H), δ 3.50–3.54 (m, 4H), δ 3.26–3.27 (m, 3H), δ 3.17–3.19 (m, 2H), δ 2.66–2.82 (m, 4H), δ 2.23–2.26 (t, J = 12 Hz, 2H), δ 1.57–1.63 (m, 6H), δ 1.32–1.48 (m, 7H), δ 1.20–1.25 (m, 9H), δ 0.82–0.84 (t, J = 8 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 173.02, 171.95, 167.89, 166.66, 159.04, 158.71, 139.10, 138.36, 136.62, 136.43, 133.46, 130.87, 130.72, 130.09, 127.79, 126.98, 125.70, 113.95, 112.91, 53.76, 49.60, 35.89, 31.61, 30.41, 29.07, 28.91, 27.23, 25.69, 22.52, 21.99, 14.40. HRMS (ESI) C47H68Cl2N10O6 [M + H]+ calcd = 939.4779; found [M + H]+ = 939.4769.

N,N′-(((5-((2-Octanamidoethyl)Carbamoyl)-1,3-Phenylene)Bis-(Azanediyl))Bis(2-Oxoethane-2,1-Diyl))Bis(2-((3S,5S,7S)-Adamantan-1-yl)-N-((S)-2,6-Diaminohexyl)Acetamide) (7).

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 10.55–10.56 (d, J = 4 Hz, 1H), δ 10.50 (s, 1H), δ 8.48–8.51 (t, J = 12 Hz, 1H), δ 8.01–8.11 (m, 3H), δ 7.88–7.95 (m, 4H), δ 7.72–7.81 (m, 8H), δ 4.24–4.36 (dd, J = 20 Hz, 2H), δ 4.01–4.17 (dd, J = 16 Hz, 2H), δ 3.65–6.71 (m, 2H), δ 3.25–3.27 (m, 2H), δ 3.17–3.20 (m, 3H), δ 2.76–2.78 (m, 4H), δ 2.33–2.38 (m, 1H), δ 1.98–2.06 (m, 5H), δ 1.89–1.92 (m, 6H), δ 1.37–1.66 (m, 38H), δ 1.18–1.24 (m, 8H), δ 0.83–0.85 (t, J = 8 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 173.18, 173.03, 171.77, 169.77, 168.65, 165.34, 158.84, 158.52, 139.30, 137.41, 113.74, 112.42, 52.90, 50.41, 49.93, 49.78, 45.42, 45.15, 36.89, 36.85, 35.89, 33.78, 33.20, 31.63, 30.37, 29.84, 29.07, 28.93, 28.49, 28.46, 27.25, 25.70, 22.54, 22.09, 21.97, 14.44. HRMS (ESI) C57H94N10O6 [M + H]+ calcd = 1015.7436; found [M + H]+ = 1015.7425.

N,N′-(((5-((2-Decanamidoethyl)Carbamoyl)-1,3-Phenylene)Bis-(Azanediyl))Bis(2-Oxoethane-2,1-Diyl))Bis(2-((3S,5S,7S)-Adamantan-1-yl)-N-((S)-2,6-Diaminohexyl)Acetamide) (8).

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 10.56–10.58 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), δ 10.50 (s, 1H), δ 8.47–8.50 (t, J = 12 Hz, 1H), δ 8.11–8.21 (m, 3H), δ 7.90–7.94 (m, 4H), δ 7.73–7.87 (m, 8H), δ 4.25–4.36 (dd, J = 20 Hz, 2H), δ 4.02–4.17 (dd, J = 16 Hz, 2H), δ 3.66–3.72 (m, 1H), δ 3.34–3.38 (m, 2H), δ 3.25–3.29 (m, 2H), δ 3.17–3.22 (m, 2H), δ 2.73–2.82 (m, 4H), δ 2.35–2.38 (d, J = 12 Hz, 1H), δ 1.98–2.07 (m, 5H), δ 1.90–1.94 (m, 6H), δ 1.37–1.67 (m, 38H), δ 1.16–1.26 (m, 12H), δ 0.83–0.87 (t, J = 12 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 173.17, 171.78, 169.75, 168.63, 165.68, 165.26, 158.97, 158.65, 139.46, 136.59, 114.18, 113.14, 52.91, 51.87, 50.40, 49.94, 49.78, 45.42, 45.14, 42.21, 36.89, 36.85, 35.88, 33.77, 33.20, 31.73, 30.35, 29.82, 29.36, 29.25, 29.13, 28.50, 28.46, 27.23, 25.69, 22.57, 22.08, 21.97, 14.44. HRMS (ESI) C59H98N10O6 [M + H]+ calcd = 1043.7749; found [M + H]+ = 1043.7739.

N,N′-(((5-((2-Dodecanamidoethyl)Carbamoyl)-1,3-Phenylene)-Bis(Azanediyl))Bis(2-Oxoethane-2,1-Diyl))Bis(2-((3S,5S,7S)-Adamantan-1-yl)-N-((S)-2,6-Diaminohexyl)Acetamide) (9).

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 10.50–10.51 (d, J = 4 Hz, 1H), δ 10.43 (s, 1H), δ 8.42–8.44 (t, J = 8 Hz, 1H), δ 8.08 (s, 2H), δ 7.83–7.88 (m, 3H), δ 7.74–7.76 (m, 4H), δ 4.18–4.29 (dd, J = 16 Hz, 2H), δ 3.95–4.10 (dd, J = 16 Hz, 2H), δ 3.59–3.63 (m, 1H), δ 3.48–3.49 (m, 2H) δ 3.26–3.28 (m, 2H), δ 3.18–3.21 (m, 2H), δ 3.11–3.12 (m, 2H), δ 2.69–2.71 (d, J = 8 Hz, 4H), δ 2.28–2.32 (dd, J = 4 Hz, 1H), δ 1.91–1.99 (m, 5H), δ 1.83–1.84 (t, J = 4 Hz, 6H), δ 1.37–1.60 (m, 39H), δ 1.16–1.21 (m, 17H), δ 0.76–0.8 (t, J = 16 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 173.13, 172.92, 171.75, 169.74, 168.61, 166.88, 158.88, 158.57, 139.31, 136.61, 114.18, 113.94, 113.09, 52.89, 51.87, 50.36, 49.90, 49.75, 45.41, 45.14, 42.21, 36.90, 36.85, 35.88, 33.77, 33.19, 31.78, 30.36, 29.82, 29.49, 29.41, 29.27, 29.21, 29.14, 28.50, 28.46, 27.24, 25.69, 22.59, 22.08, 21.97, 14.46. HRMS (ESI) C61H102N10O6 [M + H]+ calcd = 1071.8062; found [M + H]+ = 1071.8050.

N,N′-(((5-((2-Dodecanamidoethyl)Carbamoyl)-1,3-Phenylene)-Bis(Azanediyl))Bis(2-Oxoethane-2,1-Diyl))Bis(N-((S)-2,6-Diaminohexyl)Octanamide) (10).

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 10.50–10.51 (d, J = 4 Hz, 1H), δ 10.48 (s, 1H), δ 8.43–8.45 (m, 1H), δ 8.11–8.14 (m, 2H), δ 8.04 (s, 1H), δ 7.88–7.91 (m, 5H), δ 7.71–7.80 (m, 8H), δ 4.21–4.33 (dd, J = 20 Hz, 2H), δ 4.02–4.18 (dd, J = 16 Hz, 2H), δ 3.26–3.29 (m, 3H), δ 3.17–3.21 (m, 2H), δ 2.75–2.80 (q, J = 20 Hz, 4H), δ 3.26–3.46 (m, 1H), δ 2.19–2.22 (m, 2H), δ 2.03–2.07 (t, J = 16 Hz, 2H), δ 1.39–1.55 (m, 18H), δ 1.21–1.27 (m, 32H), δ 0.79–0.88 (m, 9H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 175.03, 173.73, 173.02, 169.80, 168.46, 166.87, 158.88, 158.56, 139.30, 136.56, 136.45, 114.13, 113.25, 52.19, 51.18, 50.54, 49.94, 35.91, 32.69, 32.44, 31.75, 31.68, 31.61, 30.28, 29.94, 29.45, 29.38, 29.23, 29.17, 29.10, 29.00, 27.21, 25.68, 25.04, 24.75, 22.55, 22.49, 21.98, 14.42, 14.35. HRMS (ESI) C53H98N10O6 [M + H]+ calcd = 971.7749; found [M + H]+ = 971.7755.

N,N′-(5-((2-Dodecanamidoethyl)Carbamoyl)-1,3-Phenylene)Bis-(2-(((S)-2,6-Diaminohexyl)Amino)Acetamide) (11).

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 10.15 (s, 1H), δ 8.46–8.50 (q, J = 16 Hz, 1H), δ 8.14–8.16 (q, J = 8 Hz, 1H), δ 7.93–7.96 (t, J = 12 Hz, 1H), δ 7.74–7.79 (m, 5H), δ 7.71–7.72 (d, J = 4 Hz, 2H), δ 4.21–4.23 (m, 2H), δ 4.01(s, 2H), δ 3.57–3.60 (m, 4H), δ 3.51–3.53 (m, 4H), δ 3.26–3.29 (m, 4H), δ 3.17–3.20 (m, 2H), δ 2.78 (s, 4H), δ 2.68–2.70 (m, 2H), δ 2.03–2.06 (t, J = 12 Hz, 2H), δ 1.61–1.69 (m, 4H), δ 1.53–1.60 (m, 4H), δ 1.45–1.48 (m, 2H), δ 1.36–1.39 (m, 4H), δ 1.16–1.27 (m, 16H), δ 0.83–0.87 (t, J = 12 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 172.99, 166.84, 158.84, 158.51, 139.19, 123.37, 123.19, 114.32, 112.51, 56.83, 55.73, 35.88, 31.77, 30.51, 29.48, 29.40, 29.26, 29.20, 29.12, 27.07, 25.69, 23.31, 22.58, 14.46. HRMS (ESI) C37H70N10O4 [M + H]+ calcd = 719.5660; found [M + H]+ = 719.5648.

N,N′-(((5-((2-(2-((1s,3s)-Adamantan-1-Yl)Acetamido)Ethyl)-Carbamoyl)-1,3-Phenylene)Bis(Azanediyl)) Bis(2-Oxoethane-2,1-Diyl))Bis(2-((3S,5S,7S)-Adamantan-1-yl)-N-((S)-2,6-Diaminohexyl)-Acetamide) (12).

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 10.60–10.61 (d, J = 4 Hz, 1H), δ 10.55 (s, 1H), δ 8.48–8.50 (m, 1H), δ 8.10–8.17 (m, 3H), δ 7.91–7.96 (m, 4H), δ 7.78–7.87 (m, 7H), δ 4.30–4.42 (dd, J = 20 Hz, 2H), δ 4.07–4.24 (dd, J = 16 Hz, 2H), δ 3.71–3.77 (m, 1H), δ 3.40–3.44 (m, 3H), δ 3.32–3.37 (m, 3H), δ 3.26–3.29 (m, 2H), δ 2.79–2.86 (m, 4H), δ 2.40–2.44 (m, 1H), δ 2.04–2.10 (m, 3H), δ 1.87–1.96 (m, 11H), δ 1.57–1.73 (m, 42H), δ 1.43–1.51 (m, 4H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 173.18, 171.78, 171.17, 169.77, 168.64, 158.65, 157.90, 139.30, 113.78, 112.84, 52.92, 51.89, 50.58, 49.95, 45.42, 45.15, 36.89, 36.84, 33.78, 33.19, 32.58, 30.37, 29.84, 28.50, 28.45, 27.24, 22.09, 21.97. HRMS (ESI) C61H96N10O6 [M + H]+ calcd = 1065.7593; found [M + H]+ = 1065.7583.

N,N′-(((5-(Hexylcarbamoyl)-1,3-Phenylene)Bis (Azanediyl))Bis(2-Oxoethane-2,1-Diyl))Bis(2-((3S,5S,7S)-Adamantan-1-yl)-N-((S)-2,6-Diaminohexyl)Acetamide) (13).

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 10.51–10.52 (d, J = 4 Hz, 1H), δ 10.45 (s, 1H), δ 8.39–8.42 (m, 1H), δ 8.10 (s, 3H), δ 7.89 (s, 3H), δ 7.72–7.83 (m, 8H), δ 4.24–4.35 (dd, J = 20 Hz, 2H), δ 4.10–4.18 (dd, J = 16 Hz, 2H), δ 3.65–3.76 (m, 2H), δ 3.14–3.23 (m, 2H), δ 2.75–2.84 (m, 4H), δ 2.34–2.38 (d, J = 20 Hz, 1H), δ 1.91–2.07 (m, 10H), δ 1.37–1.63 (m, 38H), δ 1.28–1.32 (m, 6H), δ 0.85–0.88 (t, J = 12 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 173.22, 171.79, 169.74, 168.65, 166.09, 157.95, 157.58, 139.22, 136.71, 114.24, 113.29, 52.97, 51.91, 50.47, 50.01, 49.85, 45.45, 45.17, 42.25, 36.89, 33.79, 33.22, 31.48, 30.38, 29.86, 29.49, 28.52, 28.48, 27.25, 26.59, 22.52, 22.08, 21.97, 14.40. HRMS (ESI) C53H87N9O5 [M + H]+ calcd = 930.6908; found [M + H]+ = 930.6900.

N,N′-(((5-(Octylcarbamoyl)-1,3-Phenylene)Bis (Azanediyl))Bis(2-Oxoethane-2,1-Diyl))Bis(2-((3S,5S,7S)-Adamantan-1-yl)-N-((S)-2,6-Diaminohexyl)Acetamide) (14).

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 10.54–10.56 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), δ 10.47–10.48 (d, J = 4 Hz, 1H), δ 10.44–10.45 (m, 1H), δ 8.11–8.12 (m, 2H), δ 8.03 (s, 1H), δ 7.91 (s, 3H), δ 7.68–7.81 (m, 7H), δ 4.25–4.36 (dd, J = 16 Hz, 2H), δ 4.01–4.17 (dd, J = 16 Hz, 2H), δ 3.65–3.72 (m, 1H), δ 3.50–3.56 (m, 4H), δ 3.31–3.33 (m, 2H), δ 3.17–3.22 (m, 2H), δ 2.73–2.79 (m, 4H), δ 2.35–2.39 (m, 1H), δ 1.98–2.04 (m, 3H), δ 1.90–1.96 (m, 6H), δ 1.37–1.67 (m, 35H), δ 1.25–1.28 (m, 10H), δ 0.84–0.87 (t, J = 12 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 173.20, 171.79, 169.75, 168.66, 165.41, 159.90, 159.20, 139.25, 137.08, 116.29, 114.22, 52.93, 51.89, 50.42, 49.96, 49.79, 42.22, 36.89, 36.85, 33.79, 33.20, 31.74, 30.36, 29.83, 29.52, 29.23, 29.14, 28.50, 28.46, 27.24, 26.93, 22.57, 22.08, 21.96, 14.45. HRMS (ESI) C55H91N9O5 [M + H]+ calcd = 958.7221; found [M + H]+ = 958.7207.

N,N′-(((5-(Decylcarbamoyl)-1,3-Phenylene)Bis (Azanediyl))Bis(2-Oxoethane-2,1-Diyl))Bis(2-((3S,5S,7S)-Adamantan-1-yl)-N-((S)-2,6-Diaminohexyl)Acetamide) (15).

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 10.56–10.58 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), δ 4.48–4.49 (d, J = 4 Hz, 1H), δ 8.42–8.45 (t, J = 12 Hz, 1H), δ 8.12–8.17 (m, 3H), δ 7.91–7.95 (m, 3H), δ 7.82–7.85 (m, 5H), δ 7.69–7.77 (m, 2H), δ 4.26–4.36 (dd, J = 16 Hz, 2H), δ 4.02–4.17 (dd, J = 20 Hz, 2H), δ 3.66–3.73 (m, 1H), δ 3.17–3.22 (m, 2H), δ 2.89–2.97 (q, J = 32 Hz, 2H), δ 2.75–2.80 (m, 4H), δ 2.35–2.39 (d, J = 16 Hz, 1H), δ 1.98–2.05 (m, 3H), δ 1.90–1.95 (m, 6H), δ 1.34–1.67 (m, 37H), δ 1.24–1.27 (m, 14H), δ 1.14–1.18 (t, J = 16 Hz, 3H), δ 0.83–0.87 (t, J = 16 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 173.19, 171.79, 169.72, 168.64, 164.89, 158.88, 158.56, 139.25, 137.04, 114.20, 111.31, 52.91, 51.89, 49.93, 45.42, 45.16, 42.30, 42.21, 36.89, 36.85, 33.79, 33.20, 31.77, 30.35, 29.82, 29.49, 29.27, 29.18, 28.50, 28. HRMS (ESI) C57H95N9O5 [M + H]+ calcd = 986.7534; found [M + H]+ = 986.7537.

MIC.

Briefly, MRSA, MRSE, VREF, E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and P. aeruginosa were grown in a TSB medium at 37 °C for 16 h while shaking. Then, 100 μL of the bacterial solution was transferred into 4 mL of a fresh TSB medium and incubated for another 6 h to reach a mid-log phase. Following this, 50 μL of bacteria with a concentration of 106 CFU/mL was added into 50 μL of compounds with concentrations from 0.75 to 25 μg/mL in 96-well plates. The mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 16 h. A multimode microplate reader was used to determine the MICs.

Salt Sensitivity.

The same method of evaluating MICs was applied here to test the salt sensitivity. For salt sensitivity assay against Na+ and K+, the medium we applied to dilute bacteria and compounds was TSB powder in a phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) buffer. Similarly, for the salt sensitivity assay against Ca2+, the medium was TSB powder in deionized (DI) water with 2 mM CaCl2. Then, MICs were tested as normal.

Hemolytic Activity.

The fresh human red blood cells were washed with 1 × PBS buffer and centrifuged at 700 g for 10 min until the supernatant was clear. After removing the supernatant, the red blood cells were diluted into 5% suspension with 1 × PBS buffer. A volume of 50 μL of suspension was added into 50 μL of compounds with different concentrations from 250 to 1.95 μg/mL in 96-well plates, and then the mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. Following this, the plates were centrifuged at 3500 rpm for 10 min. A volume of 30 μL of supernatant was transferred into another well with 100 μL of 1 × PBS buffer. Subsequently, the absorbance at 540 nm was read using a microplate reader. 2% Triton-100 was used as a positive control. The hemolysis activity was calculated using the formula % hemolysis = [(Abssample − AbsPBS)/(AbsTriton − AbsPBS)] × 100.

Time-Kill Kinetics Study.

Mid-log phase MRSA and E. coli at a concentration of 106 CFU/mL in TSB solution were first obtained using the method mentioned in the MIC test. Compound 12 (300 μL) and ciprofloxacin with different concentrations were mixed with 300 μL of the bacterial solution. The mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 0, 10, 30 min, 1, and 2 h, respectively. At each time point, the solution was diluted 1000-fold for E. coli and 100-fold for MRSA, respectively, and then 100 μL was spread on TSB agar plates. After incubating at 37 °C for 16 h, colonies were enumerated and CFUs were calculated.

Biofilm Inhibition.

Bacteria at a concentration of 106 CFU/mL was added to compound 12 with different concentrations. The mixture was incubated for 48 h. Subsequently, the suspension was discarded, and the biofilm was washed gently. After drying in air, 0.1% crystal violet in DI water was applied to stain the biofilm for 15 min. The dye solution was discarded, and the biomass was washed with DI water for several times. A volume of 200 μL of 30% acetic acid was used to dissolve the colored biomass for 15 min after drying. The solution (125 μL) was transferred into another 96-well plate to be read under 595 nm. The relative biofilm biomass values were normalized by the biomass value of the control (no addition of compounds). The data were presented as mean ± STDEV.

Drug Resistance Study.

The first-generation MIC data of compound 12 and ciprofloxacin against MRSA were obtained as described in the MIC study mentioned above. Then, MRSA in the well next to the last clear well was diluted to 106 CFU/mL to determine the MICs again at 37 °C incubation for 12 h. The step was repeated until 14 passages. Drug resistance of compound 12 and ciprofloxacin against E. coli was conducted with the same method.

Fluorescence Microscopy.

After MRSA and E. coli were grown into the mid-log phase in the TSB medium, 30 μL of bacterial solution was diluted to 3 mL in the TSB medium with 6 μg/mL of compound 12. The mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. Negative controls were untreated bacteria. Subsequently, the bacterial cells were collected and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min. The cell pellets were washed with 1 × PBS buffer three times and incubated with PI (5 μg/mL) and DAPI (10 μg/mL) for 15 min sequentially on ice in the dark. The bacterial cells were washed with 1 × PBS three times after dying procedure with both PI and DAPI. Next, after the final wash, 100 μL of 1 × PBS was used to suspend the bacterial cells and 10 μL of solution was dropped on to the slides to be observed using a Zeiss Axiovert 200 inverted microscope.

TEM.

A volume of 30 μL of mid-log phase MRSA and E. coli was diluted to 3 mL in a fresh TSB medium with 6 μg/mL of compound 12 and was then incubated for 2 h, respectively. The bacterial pellets were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min. 1 × PBS was used to wash them for three times. The negative control was untreated bacterial cells. Then, resuspended bacterial samples were dropped on the surface of grids. The grids were dried in a vacuum oven at 45 °C for 30 s. TEM images were obtained using an FEI Morgagni 268D TEM with an Olympus MegaView III camera on the microscope. The microscope uses Analysis software to run the camera. The microscope was operated at 60 kV.

Inner Membrane Permeability.

E. coli was grown to the mid-log phase in a Mueller Hinton broth containing 2% lactose at 37 °C. Bacterial cells were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C and then were washed with 5 mM HEPES buffer containing 20 mM glucose and 1.5 mM ONPG once. Subsequently, the bacterial cells were diluted to OD600 = 0.1 using the buffer mentioned above. The diluted bacterial cells (50 μL) were added into 50 μL of compound 12 and melittin with different concentrations in the buffer, respectively. The OD420 measurements of the mixture were carried out every 6 min at 37 °C until the fluorescence reached the highest value. The experiment was conducted independently in duplicate with two biological replicates.

Cytoplasmic Membrane Assay.

Mid-log MRSA was collected and then washed with 5 mM HEPES:5 mM glucose = 1:1. Following this, MRSA cells were resuspended to OD600 = 0.1 in 5 mM HEPES/5 mM glucose/100 mM KCl (1:1:1) buffer with 2 μM DiSC3(5). The mixture was kept at room temperature for 30 min. The fluorescence of the suspension was then monitored at room temperature for 8 min with an interval of 2 min at an excitation wavelength of 622 nm and an emission wavelength of 670 nm. Compound 12 with different concentrations was added into the above suspension. The fluorescence was read continuously for 12 min. The negative control was untreated MRSA.

In Vivo Antibacterial Assessment and Biocompatibility Evaluation.

The experiments were performed according to IACUC of Sun Yat-Sen University (approved protocol number SYSU-IACUC-2019-000203), and all animal care procedures were performed according to the Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Healthy female ICR mice (16–20 g each), which were obtained from the Animal Center of Sun Yat-Sen University, were employed and randomly divided into five groups, including normal group, control group, ciprofloxacin group, low-dose compound 12 group (12-L), and high-dose compound 12 group (12-H). While a ciprofloxacin hydrochloride solution was prepared at a concentration of 5 mg/mL, compound 12 was dissolved in sterile PBS at concentrations of 0.5 and 5 mg/mL, respectively. The mice were anesthetized, and their back hair was removed with a shaving knife and depilation cream. Subsequently, a subcutaneous abscess was created by subcutaneously injecting MRSA (1 × 108 CFU/mL) with a dose of 100 μL into the middle dorsum of mice. After 30 min, 100 μL of sterile PBS, ciprofloxacin hydrochloride solution, or compound 12 solution was injected into the bacterial infection site. After 48 h, the mice were euthanized, and the infected skins were collected. To evaluate the antibacterial affect, the bacteria in the abscess were counted using the standard plate counting assays, and the visible bacterial colonies on the plates were imaged. The infected skins were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, and stained with H&E for assessing the antimicrobial effectiveness of various agents. IL-6 and TNF-α levels in the skin homogenate solutions were measured using commercial ELISA kits (Dakewe, Shenzhen, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The major organs of mice were also harvested and further analyzed by H&E staining for the systemic toxicity assessment. In a local toxicity study, the dorsal skin of ICR mice was injected subcutaneously with a peptide solution (100 μL, 5 mg/mL) and collected for histological analysis after 5 days postinjection.

Supplementary Material

Table 1.

MICs and Therapeutic Index of Compounds 1–15a

| MIC (μg/mL) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gram-positive | Gram-negative | |||||||

| compound # | MRSA | MRSE | VREF | E. coli | P. aeruginosa | K. pneumoniae | HC50 (μg/mL) | therapeutic index (HC50/MIC against MRSA) |

| 1 | >25 | NT | NT | >25 | NT | NT | >250 | |

| 2 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 4.5 | >25 | >250 | >55.5 |

| 3 | 9 | 9 | >25 | 4.5 | >25 | 4.5 | >250 | >27.8 |

| 4 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 9 | 4.5 | >25 | >250 | >55.5 |

| 5 | >25 | NT | NT | >25 | NT | NT | >250 | |

| 6 | >25 | NT | NT | >25 | NT | NT | >250 | |

| 7 | 2 | 2 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 4.5 | >250 | >125 |

| 8 | 1 | 2 | 4.5 | 19 | 2 | 4.5 | >250 | >250 |

| 9 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 4.5 | >25 | >25 | >25 | 250 | 55.5 |

| 10 | 4.5 | 9 | >25 | >25 | >25 | >25 | >250 | >55.5 |

| 11 | >25 | NT | NT | >25 | NT | NT | >250 | |

| 12 | 2 | 2 | 4.5 | 2 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 250 | 125 |

| 13 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 9 | 4.5 | 9 | 125 | 62.5 |

| 14 | 2 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 9 | 19 | 9 | 125 | 62.5 |

| 15 | 2 | 9 | 2 | >25 | >25 | >25 | 125 | 62.5 |

| ciprofloxacin | 0.24 | 0.45 | 0.9 | 0.12 | 0.45 | 0.9 | NT | |

NT: not tested.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The meaningful discussion of Dr. Laurent Calcul is acknowledged.

Funding

This work is supported by 9R01AI152416 (J.C.) and 5R01AI149852 (J.C.).

ABBREVIATIONS

- γ-AA peptides

γ-substituted-N-acylated-N-aminoethyl peptides

- AMPs

antimicrobial peptides

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- DAPI

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- DEA

diethanolamine

- DiSC3(5)

3,3′-dipropylthiadicarbocyanine iodide

- E. coli

Escherichia coli

- HATU

1-[bis-(dimethylamino)methylene]-1H-1,2,3-triazolo[4,5-b]-pyridinium 3-oxide hexafluorophosphate

- HDPs

host defense peptides

- H&E

hematoxylin and eosin

- IL-6

interleukin-6

- K. pneumoniae

Klebsiella pneumoniae

- MRSE

multiresistance Staphylococcus epidermidis

- ONPG

o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside

- P. aeruginosa

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- PDR

pandrug resistance

- PI

propidium iodide

- PNA

peptide nucleic acid

- TEM

transmission electron microscopy

- TSB

tryptic soy broth

- VREF

vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis

Footnotes

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c00312

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c00312.

Time-kill kinetics of compound 12 and ciprofloxacin against E. coli; E. coli biofilm inhibition by compound 12; drug resistance study of compound 12 against E. coli; and 1H NMR, 13C NMR, and HPLC trace information (PDF) Molecular formula strings (CSV)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Contributor Information

Minghui Wang, Department of Chemistry, University of South Florida, Tampa, Florida 33620, United States.

Xiaoqian Feng, College of Pharmacy, Jinan University, Guangzhou, Guangdong 511443, China; Department of Pharmaceutics, Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou, Guangdong 510006, China.

Ruixuan Gao, Department of Chemistry, University of South Florida, Tampa, Florida 33620, United States.

Peng Sang, Department of Chemistry, University of South Florida, Tampa, Florida 33620, United States.

Xin Pan, Department of Pharmaceutics, Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou, Guangdong 510006, China;.

Lulu Wei, Department of Chemistry, University of South Florida, Tampa, Florida 33620, United States.

Chao Lu, College of Pharmacy, Jinan University, Guangzhou, Guangdong 511443, China;.

Chuanbin Wu, College of Pharmacy, Jinan University, Guangzhou, Guangdong 511443, China;.

Jianfeng Cai, Department of Chemistry, University of South Florida, Tampa, Florida 33620, United States;.

REFERENCES

- (1).Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/biggest-threats.html (accessed Mar 22, 2021).

- (2).Niu Y; Wang M; Cao Y; Nimmagadda A; Hu J; Wu Y; Cai J; Ye X Rational design of dimeric lysine N-alkylamides as potent and broad-spectrum antibacterial agents. J. Med. Chem 2018, 61, 2865–2874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Theuretzbacher U; Outterson K; Engel A; Karlén A The global preclinical antibacterial pipeline. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 2020, 18, 275–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Baker SJ; Payne DJ; Rappuoli R; De Gregorio E Technologies to address antimicrobial resistance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2018, 115, 12887–12895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Liu D; Choi S; Chen B; Doerksen RJ; Clements DJ; Winkler JD; Klein ML; DeGrado WF Nontoxic membrane-active antimicrobial arylamide oligomers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 2004, 43, 1158–1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Ling LL; Schneider T; Peoples AJ; Spoering AL; Engels I; Conlon BP; Mueller A; Schäberle TF; Hughes DE; Epstein S; Jones M; Lazarides L; Steadman VA; Cohen DR; Felix CR; Fetterman KA; Millett WP; Nitti AG; Zullo AM; Chen C; Lewis K A new antibiotic kills pathogens without detectable resistance. Nature 2015, 517, 455–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Rahman MA; Bam M; Luat E; Jui MS; Ganewatta MS; Shokfai T; Nagarkatti M; Decho AW; Tang C Macromolecular-clustered facial amphiphilic antimicrobials. Nat. Commun 2018, 9, 5231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Rahman MA; Jui MS; Bam M; Cha Y; Luat E; Alabresm A; Nagarkatti M; Decho AW; Tang C Facial amphiphilicity-induced polymer nanostructures for antimicrobial applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 21221–21230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Melo MN; Ferre R; Castanho M Antimicrobial peptides: linking partition, activity and high membrane-bound concentrations. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 2009, 7, 245–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Ong ZY; Wiradharma N; Yang YY Strategies employed in the design and optimization of synthetic antimicrobial peptide amphiphiles with enhanced therapeutic potentials. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev 2014, 78, 28–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Zheng M; Pan M; Zhang W; Lin H; Wu S; Lu C; Tang S; Liu D; Cai J Poly(α-l-lysine)-based nanomaterials for versatile biomedical applications: current advances and perspectives. Bioact. Mater 2021, 6, 1878–1909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Wang M; Gao R; Zheng M; Sang P; Li C; Zhang E; Li Q; Cai J Development of bis-cyclic imidazolidine-4-one derivatives as potent antibacterial agents. J. Med. Chem 2020, 63, 15591–15602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Mowery BP; Lee SE; Kissounko DA; Epand RF; Epand RM; Weisblum B; Stahl SS; Gellman SH Mimicry of antimicrobial host-defense peptides by random copolymers. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2007, 129, 15474–15476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Mowery BP; Lindner AH; Weisblum B; Stahl SS; Gellman SH Structure–activity relationships among random nylon-3 copolymers that mimic antibacterial host-defense peptides. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131, 9735–9745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Tew GN; Scott RW; Klein ML; DeGrado WF De novo design of antimicrobial polymers, foldamers, and small molecules: from discovery to practical applications. Acc. Chem. Res 2010, 43, 30–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Tew GN; Liu D; Chen B; Doerksen RJ; Kaplan J; Carroll PJ; Klein ML; DeGrado WF De novo design of biomimetic antimicrobial polymers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2002, 99, 5110–5114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Thaker HD; Cankaya A; Scott RW; Tew GN Role of amphiphilicity in the design of synthetic mimics of antimicrobial peptides with gram-negative activity. ACS Med. Chem. Lett 2013, 4, 481–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Lienkamp K; Madkour AE; Musante A; Nelson CF; Nüsslein K; Tew GN Antimicrobial polymers prepared by ROMP with unprecedented selectivity: a molecular construction kit approach. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 9836–9843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Nederberg F; Zhang Y; Tan J; Xu K; Wang H; Yang C; Gao S; Guo XD; Fukushima K; Li L; Hedrick JL; Yang YY Biodegradable nanostructures with selective lysis of microbial membranes. Nat. Chem 2011, 3, 409–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Ng V; Ke X; Lee A; Hedrick JL; Yang YY Synergistic co-delivery of membrane-disrupting polymers with commercial antibiotics against highly opportunistic bacteria. Adv. Mater 2013, 25, 6730–6736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Zhang K; Du Y; Si Z; Liu Y; Turvey ME; Raju C; Keogh D; Ruan L; Jothy SL; Reghu S; Marimuthu K; De PP; Ng OT; Mediavilla JR; Kreiswirth BN; Chi YR; Ren J; Tam KC; Liu XW; Duan H; Zhu Y; Mu Y; Hammond PT; Bazan GC; Pethe K; Chan-Park MB Enantiomeric glycosylated cationic block co-beta-peptides eradicate Staphylococcus aureus biofilms and antibiotic-tolerant persisters. Nat. Commun 2019, 10, 4792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Zhou C; Qi X; Li P; Chen WN; Mouad L; Chang MW; Leong SS; Chan-Park MB High potency and broad-spectrum antimicrobial peptides synthesized via ring-opening polymerization of alpha-aminoacid-N-carboxyanhydrides. Biomacromolecules 2010, 11, 60–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Zhou M; Xiao X; Cong Z; Wu Y; Zhang W; Ma P; Chen S; Zhang H; Zhang D; Zhang D; Luan X; Mai Y; Liu R Water-insensitive synthesis of poly-β-peptides with defined architecture. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2020, 59, 7240–7244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Fjell CD; Hiss JA; Hancock REW; Schneider G Designing antimicrobial peptides: form follows function. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 2012, 11, 37–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Garcia S; Trinh CT Modular design: implementing proven engineering principles in biotechnology. Biotechnol. Adv 2019, 37, 107403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Wang M; Gao R; Sang P; Odom T; Zheng M; Shi Y; Xu H; Cao C; Cai J Dimeric γ-AApeptides with potent and selective antibacterial activity. Front. Chem 2020, 8, 441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Wang M; Odom T; Cai J Challenges in the development of next-generation antibiotics: opportunities of small molecules mimicking mode of action of host-defense peptides. Exp. Opin. Ther. Pat 2020, 30, 303–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Zhou M; Zheng M; Cai J Small molecules with membrane-active antibacterial activity. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 21292–21299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Shi Y; Teng P; Sang P; She F; Wei L; Cai J γ-AApeptides: design, structure, and applications. Acc Chem. Res 2016, 49, 428–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Su M; Xia D; Teng P; Nimmagadda A; Zhang C; Odom T; Cao A; Hu Y; Cai J Membrane-active hydantoin derivatives as antibiotic agents. J. Med. Chem 2017, 60, 8456–8465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Yang Z; He S; Wang J; Yang Y; Zhang L; Li Y; Shan A Rational design of short peptide variants by using Kunitzin-RE, an amphibian-derived bioactivity peptide, for acquired potent broad-spectrum antimicrobial and improved therapeutic potential of commensalism coinfection of pathogens. J. Med. Chem 2019, 62, 4586–4605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Hoque J; Konai MM; Sequeira SS; Samaddar S; Haldar J Antibacterial and antibiofilm activity of cationic small molecules with spatial positioning of hydrophobicity: an in vitro and in vivo evaluation. J. Med. Chem 2016, 59, 10750–10762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Waclaw B Evolution of drug resistance in bacteria. In Biophysics of infection; Leake MC, Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Switzerland, 2016; 49–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Bucki R; Niemirowicz-Laskowska K; Deptuła P; Wilczewska AZ; Misiak P; Durnaś B; Fiedoruk K; Piktel E; Mystkowska J; Janmey PA Susceptibility of microbial cells to the modified PIP2-binding sequence of gelsolin anchored on the surface of magnetic nanoparticles. J. Nanobiotechnology 2019, 17, 81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Zasloff M Antimicrobial peptides of multicellular organisms. Nature 2002, 415, 389–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Yarlagadda V; Akkapeddi P; Manjunath GB; Haldar J Membrane active vancomycin analogues: a strategy to combat bacterial resistance. J. Med. Chem 2014, 57, 4558–4568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Wang J; Lu C; Shi Y; Feng X; Wu B; Zhou G; Quan G; Pan X; Cai J; Wu C Structural superiority of guanidinium-rich, four-armed copolypeptides: role of multiple peptide-membrane interactions in enhancing bacterial membrane perturbation and permeability. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 18363–18374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Lu C; Quan G; Su M; Nimmagadda A; Chen W; Pan M; Teng P; Yu F; Liu X; Jiang L; Du W; Hu W; Yao F; Pan X; Wu C; Liu D; Cai J Molecular architecture and charging effects enhance the in vitro and in vivo performance of multi-arm antimicrobial agents based on star-shaped poly(l-lysine). Adv. Ther 2019, 2, No. 1900147. [Google Scholar]

- (39).Engler AC; Wiradharma N; Ong ZY; Coady DJ; Hedrick JL; Yang YY Emerging trends in macromolecular antimicrobials to fight multi-drug-resistant infections. Nano Today 2012, 7, 201–222. [Google Scholar]

- (40).Tan J; Tay J; Hedrick J; Yang YY Synthetic macromolecules as therapeutics that overcome resistance in cancer and microbial infection. Biomaterials 2020, 252, No. 120078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Bai S; Wang J; Yang K; Zhou C; Xu Y; Song J; Gu Y; Chen Z; Wang M; Shoen C; Andrade B; Cynamon M; Zhou K; Wang H; Cai Q; Oldfield E; Zimmerman SC; Bai Y; Feng X A polymeric approach toward resistance-resistant antimicrobial agent with dual-selective mechanisms of action. Sci. Adv 2021, 7, No. eabc9917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.