Abstract

The emergence of double mutation delta (B.1.617.2) variants has dropped vaccine effectiveness against SARS-CoV-2 infection. Although COVID-19 is responsible for more than 5.4 M deaths till now, more than 40% of infected individuals are asymptomatic carriers as the immune system of the human body can control the SARS-CoV-2 infection. Herein, we report for the first time that human host defense neutrophil α-defensin HNP1 and human cathelicidin LL-37 peptide-conjugated graphene quantum dots (GQDs) have the capability to prevent the delta variant virus entry into the host cells via blocking SARS-CoV-2 delta variant (B.1.617.2) spike protein receptor-binding domain (RBD) binding with host cells’ angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2). Experimental data shows that due to the binding between the delta variant spike protein RBD and bioconjugate GQDs, in the presence of the delta variant spike protein, the fluorescence signal from GQDs quenched abruptly. Experimental quenching data shows a nonlinear Stern–Volmer quenching profile, which indicates multiple binding sites. Using the modified Hill equation, we have determined n = 2.6 and the effective binding affinity 9 nM, which is comparable with the ACE2–spike protein binding affinity (8 nM). Using the alpha, beta, and gamma variant spike-RBD, experimental data shows that the binding affinity for the delta B.1.617.2 variant is higher than those for the other variants. Further investigation using the HEK293T-human ACE2 cell line indicates that peptide-conjugated GQDs have the capability for completely inhibiting the entry of delta variant SARS-CoV-2 pseudovirions into host cells via blocking the ACE2–spike protein binding. Experimental data shows that the inhibition efficiency for LL-37 peptide- and HNP1 peptide-attached GQDs are much higher than that of only one type of peptide-attached GQDs.

1. Introduction

The current global pandemic caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is responsible for over 5.4 million death till now.1−4 It is now well understood that during COVID-19 infection, the spike protein S1 unit containing the receptor-binding domain (S-RBD) facilitates the virus attachment to humans by binding to the angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor in the nasal epithelial mucosal cells, which is the key path for SARS-CoV-2 entry into human host cells.5−9 Therefore, the SARS-CoV-2 S protein became the target for COVID-19 vaccines available in the market, which can generate neutralizing antibodies against the S-RBD upon immunization.9−14 The emergence of double mutant delta (B.1.617.2) variants, which contain the L452R and T478K mutations on the S-RBD, has enhanced the binding affinity with ACE2.1−6 Recent reports also indicate that mutations on the S-RBD lead to a prominent decline in neutralizing antibody levels against the delta variant by antibodies generated during previous infection or vaccination.7−12 Due to the above fact, designing a new strategy to block the spike protein–ACE interaction is very important for preventing mutate variant infection.

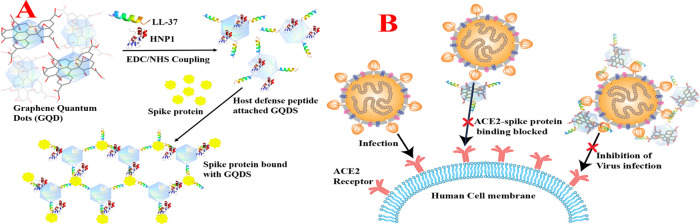

Although the mortality rate is very high for COVID-19, reported data also indicates that around 42% of infected individuals are asymptomatic carriers, which indicates that SARS-CoV-2 can be effectively controlled by the human’s innate immune system.1−9 α-Defensin human neutrophil peptides (HNP1, HNP2, HNP3, and HNP4) and human β-defensins (HBD1, HBD2, and HBD3) as well as LL-37 (leucine-leucine-37) cathelicidin family peptides are members of the innate immune system.11,15−17 Defensins and cathelicidin peptides play a crucial role in the human body for viral inhibition via binding and destabilizing.11,15−17 Driven by the need to block the delta variant infection, herein we report the design of HNP1 and LL-37 peptide-conjugated graphene quantum dots (GQDs), which have the capability to bind to the SARS-CoV-2 delta variant (B.1.617.2) spike protein RBD and block the S-RBD interaction with ACE2, which prevents the virus entry into the host cells, as shown in Figure 1.

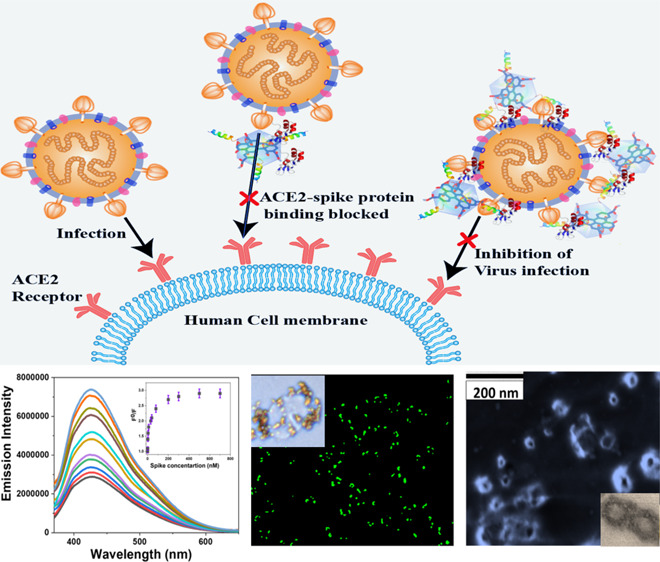

Figure 1.

(A) Scheme showing the design of HNP1 and LL-37 human host defense peptide-conjugated GQDs and binding of HNP1 and LL-37 peptide-conjugated GQDs in the presence of the SARS-CoV-2 delta variant (B.1.617.2) spike protein RBD. (B) Scheme showing the blocking of the S-RBD interaction with ACE2 on a human cell membrane and preventing the SARS-CoV-2 virus entry.

Graphene quantum dots (GQDs) consisting of a graphene lattice and containing single or few sheets of graphene fragments exhibit size-dependent luminescence properties originating from the quantum confinement effects and edge effects.18−23 GQDs containing different surface groups such as carboxy, epoxy, and hydroxyl exhibit a high water solubility, high surface area, excellent photostability, and biocompatibility.18−23 Due to their unique optical and other properties, GQDs became a very good choice for use in bioimaging, biosensing, and other biotechnology applications.18−23 In our design, bioconjugated GQD fluorescence has been used to monitor the SARS-CoV-2 delta variant (B.1.617.2) spike protein RBD–host cells’ angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) interaction to determine the effective binding affinity. Also, the functional groups on the surface and edge of GQDs have been used for the inactivation of the virus via decomposition of the lipid membrane of the virus and for the removal of spike proteins that are attached on the lipid membrane.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis and Characterization of HNP1 and LL-37 Human Host Defense Peptide-Attached Graphene Quantum Dots (GQDs)

GQDs were developed in a two-step process, as shown in Scheme S1 in the Supporting Information. Initially, graphene oxide (GO) nanosheets were synthesized from natural graphite powder using the modified Hummer’s method as we and others have reported before.18−23 In the next step, GQDs were synthesized using a hydrothermal method in the presence of dimethyl formamide (DMF).18−23 The transmission electron microscopy (TEM) image reported in Figure S2A in the Supporting Information shows the two-dimensional (2D) morphology of the freshly prepared GO with 5 ± 2 μm size. On the other hand, the TEM image reported in Figure S2B shows the zero-dimensional (0D) morphology of the freshly prepared GQDs whose sizes are 4 ± 2 nm. Table S1 shows the dynamic light scattering (DLS) measurement data, which matches well with the TEM data. As shown in Figure 1A, for the development of HNP1 and LL-37 human host defense peptide-attached GQDs, we used carbodiimide coupling chemistry between the carboxy group of graphene oxides and the amine group of peptides.

The FTIR data from peptide-attached GQDs, as reported in Figure S2G, shows the presence of the −OH stretch, −CH stretch, −amide-I, −amide-II, and −amide-III bands, which indicates that the peptides are attached on the GQD surfaces. The DLS data indicates the ζ-potential changes from −14 ± 2 mV to 3 ± 1 mV after peptide binding, which also indicates that the peptides are on the surface of GQDs. The TEM data reported in Figure 2A indicates that the size of peptide-conjugated GQDs are 6 ± 2 nm, which matches very well with the DLS data reported in Table S1. The inset in Figure 2A shows the high-resolution TEM for peptide-conjugated GQDs, which shows the graphite structure with a stripe distance of ∼0.24 nm.18−23 Similarly, Figure S2C in the Supporting Information shows the powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern, which indicates a broad peak at 26.5° due to the (002) reflection of graphite.18−23Figure S2D shows the Raman spectra of peptide-attached GQDs, which indicate the presence of the D band at ∼1350 cm–1 and the G band at ∼1590 cm–1 due to the graphene structure.18−23

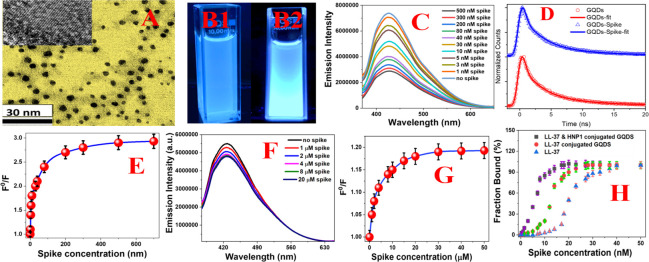

Figure 2.

(A) TEM image of freshly prepared peptide-conjugated GQDs. The high-resolution TEM image in the inset demonstrates the crystal lattice fringe for peptide-conjugated GQDs. (B) Photograph showing the fluorescence image from HNP1 and LL-37 peptide-conjugated GQDs in the presence (B2) and absence (B1) of the SARS-CoV-2 delta variant (B.1.617.2) spike protein. (C) Fluorescence spectra from peptide-conjugated GQDs in the presence of the spike protein at different concentrations. (D) Time-resolved photoluminescence decay curve from peptide-conjugated GQDs in the absence and presence of the spike protein at different concentrations. (E) Plot of log[F0/F] versus log[spike concentration, in nM] for HNP1 and LL-37 peptide-conjugated GQDs, which indicates the nonlinear fluorescence quenching process. (F) Fluorescence spectra from HNP1 human host defense peptide-conjugated GQDs in the presence of the SARS-CoV-2 delta variant (B.1.617.2) spike protein at different concentrations. (G) Plot of log[F0/F] versus log[spike concentration, in μM] for HNP1 peptide-conjugated GQDs, which indicates the nonlinear fluorescence quenching process. (H) Plot showing the binding curve between the peptide-conjugated GQDs and SARS-CoV-2 delta variant (B.1.617.2) spike protein in the ELISA plate-based assay.

2.2. Binding Studies between the SARS-CoV-2 Delta Variant (B.1.617.2) Spike Protein RBD and HNP1 and LL-37 Human Host Defense Peptide-Attached GQDs Using Peptide-Attached GQD-Based Luminescence

For the binding between the SARS-CoV-2 delta variant (B.1.617.2) spike protein RBD and HNP1 and LL-37 human host defense peptide-attached GQDs, we used a binding buffer. The experimental details are reported in the Supporting Information. For the detection of luminescence from HNP1 and LL-37 human host defense peptide-attached GQDs, in the presence and absence of the SARS-CoV-2 delta variant (B.1.617.2) spike protein RBD, we used a portable fluorescence spectrometer developed by us with a laser excitation of 360 nm from a diode laser.13,14,21,22 For emission signal collection, we used a miniaturized QE65000 spectrometer from Ocean Optics.13,14,21,22 All measurements were performed with 5 ms integration time with five spectra averaging using the software.13,14,21,22

2.3. ELISA-like Assay for Determining the Binding between the Delta Variant (B.1.617.2) Spike Protein and Peptide-Attached GQDs

For this purpose, we used an ELISA-like assay using His-tag delta variant SARS-CoV-2 S1 proteins, which were adsorbed to a 96-well plate overnight at 4 °C. For comparison with fluorescence assay data, we kept the concentrations of GQDs and spike proteins the same for both the measurements. After that, the plate was blocked using a blocking buffer and then different concentrations of peptide-attached GQDs were incubated on the plate. In the next step, we used a streptavidin protein that is covalently conjugated to a horseradish peroxidase (HRP) enzyme to determine the binding.11−15 We also used TMB (3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine) for colorimetric assay detection.11−15 Signal intensity was recorded using a plate reader. After that, data were graphed in GraphPad Prism. From the binding curve, we estimated the binding constants (KD) using the Hill equation, as reported before.7,8,11,12

2.4. In Vitro Experiments for Blocking ACE2 Binding with Baculovirus Pseudotyped with a SARS-CoV-2 Delta Variant (B.1.617.2) Spike Protein Using Fluorescence Imaging

For this experiment, we used human embryonic kidney-239T cells with a high expression of ACE2 (HEK-293T).11−15,26,27 Since delta variant SARS-CoV-2 is a biosafety-level-3 virus, for our experiment, we used a GFP (green fluorescent protein)-tagged Baculovirus pseudotyped with a SARS-CoV-2 delta variant (B.1.617.2) spike protein (catalog number #C1123G).11−15,26,27 The experimental details are reported in the Supporting Information.

2.5. Virus Inhibition Experiments for HNP1 and LL-37 Human Host Defense Peptide-Attached GQDs

For this experiment, we used HEK293T cells. Dilutions of test HNP1 and LL-37 human host defense peptide-attached GQDs were made in DMEM.13,14,26,27 The GFP-tagged Baculovirus pseudotyped with a SARS-CoV-2 delta variant (B.1.617.2) spike protein stock was mixed with the HNP1 and LL-37 human host defense peptide-attached GQDs at different concentrations and incubated for 1 h. The experimental details are reported in the Supporting Information.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Determining the Photoluminescence Quantum Yield and Lifetime from HNP1 and LL-37 Human Host Defense Peptide-Attached GQDs

The UV–vis spectra from HNP1 and LL-37 human host defense peptide-attached GQDs, as reported in Figure S2E, show two peaks. The first absorption peak is observed at ∼270 nm, which can be due to the π–π* transition, and the second peak is at ∼306 nm, which can be due to the n−π* transition.18−23Figure S2F and Figure 2C show the luminescence spectra of peptide-attached GQDs at 360 nm excitation, where the strong emission maximum at 416 nm can be due to the electron–hole recombination and quantum size effect.18−23Figure 2B shows that peptide-attached GQDs exhibit a strong blue fluorescence under UV light. The photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) was determined to be ∼0.28 for peptide-attached GQDs. The photoluminescence decay profiles for peptide-attached GQDs are reported in Figure 2D, which fit very well with the triple exponential function with τ1 = 0.32 ns, τ2 = 2.2 ns, and τ3 = 7.3 ns.

3.2. Determining the Biocompatibility and Cytotoxicity

To determine the biocompatibility and cytotoxicity of the LL-37 and HNP1 peptide-attached GQDs, we used normal skin HaCaT cells, lung cancer A549 cells, and human embryonic kidney-239T cells with a high expression of ACE2 (HEK-293T).11−15,26,27 All cells were treated with 60 μg/mL GQDs + 4 μg/mL LL-37 + 4 μg/mL HNP1 for 48 h.11−15,26,27 As reported in Figures S3A,B in the Supporting Information, after treatment with LL-37 and HNP1 peptide-attached GQDs or only GQDs or only peptides, the cell viability was hardly changed for all the cell lines. The reported experimental data clearly indicate that the LL-37 and HNP1 peptide-attached GQDs do not exhibit any detectable cytotoxicity after 48 h of treatment.

3.3. Determining the Binding Affinity between the SARS-CoV-2 Delta Variant (B.1.617.2) Spike Protein RBD and HNP1 and LL-37 Human Host Defense Peptide-Attached GQDs

Next, we have determined whether the SARS-CoV-2 delta variant (B.1.617.2) spike protein RBD can bind with HNP1 and LL-37 human host defense peptide-attached GQDs, which is a very important parameter for the inhibition of virus infection. The experimental details are reported in the Supporting Information. The luminescence signals from GQDs in the presence and absence of the spike protein were recorded with a laser excitation of 360 nm from a diode laser.11−15,26,27 The reported photograph in Figure 2B also shows that the intense fluorescence from peptide-conjugated GQDs decreases in the presence of the spike protein.

In the case of peptide-attached GQDs, the graphene quantum dots can bind with the spike protein via hydrophobic interaction, hydrogen bonding, and charge transfer interaction.18,19 On the other hand, LL-37 and HNP1 peptides can bind with the spike protein via hydrogen bonding, electrostatic interaction, and hydrophobic interaction.11,12,15 The observed huge fluorescence quenching clearly indicates the strong interaction between peptide-attached GQDs and the spike protein. The reported fluorescence quenching can be the result of the static quenching due to the formation of a nonfluorescent complex in the ground state. On the other hand, the observed quenching can be due to the dynamic quenching, which is based on the Förster resonance energy transfer from the donor peptide-attached GQDs to the acceptor spike protein. As reported in Figure 2D, the photoluminescence decay curve remains almost the same in the presence or absence of the delta variant (B.1.617.2) spike protein, which indicates that the fluorescence lifetime (τ1 = 0.30 ns, τ2 = 2.2 ns, and τ3 = 7.1 ns) in the presence of the spike protein is very similar to the data in the absence of the protein. The experimental lifetime data clearly indicates that the observed quenching is a static quenching process.

Similarly, as reported in Figure S1E in the Supporting Information, the UV–vis absorption maximum from peptide-attached GQDs is ∼10 nm shifted to a higher wavelength in the presence of the spike protein, which also indicates the formation of a complex in the ground state between the peptide-attached GQDs and spike protein. Often, the static quenching process can be described by the Stern–Volmer equation20,22,24,25 as described below

| 1 |

| 2 |

where F0 is the fluorescence intensity from the peptide-conjugated GQDs in the absence of the spike protein, F is the fluorescence intensity in the presence of the spike protein, and [spike] is the protein concentration. KSV is the Stern–Volmer constant, which depends on quencher rate coefficients (Kq) and the lifetime τ0 of the GQDs’ excited state in the absence of spike. As shown in Figure 2E, the plot of log[F0/F] versus log[spike concentration, in nM] for HNP1 and LL-37 peptide-conjugated GQDs indicates the nonlinear fluorescence quenching process, which may be due to the multiple binding sites.

Since we have observed a nonlinear Stern–Volmer quenching profile, we have used the modified Hill equation24,25

| 3 |

where Kb is the dissociation constant, [S]t is the concentration of the spike protein at any given time, [G]t is the concentration of peptide-conjugated GQDs at any given time, and n is the Hill coefficient. We have determined the binding affinity, which is the inverse of the dissociation constant, by fitting the curve with eq 3, as reported in Figures 2E,G. As shown in Table 1, we have determined the binding affinity as 8 ± 1 nM and n = 2.6.

Table 1. Binding Affinity Measured by Fluorescence Quenching and ELISA Assays.

| system | GQD-based fluorescence quenching | ELISA-like assay |

|---|---|---|

| LL-37 & HNP1-attached GQDs | 8 ± 1 nM | 9 ± 1 nM |

| LL-37-attached GQDs | 12 ± 1 nM | 13 ± 1 nM |

| HNP1-attached GQDs | 120 ± 20 nM | 116 ± 20 nM |

| LL-37 peptide | 16 ± 1 nM | |

| HNP1 peptide | 160 ± 40 nM | |

| ACE2 | 8 ± 1 nM | |

| GQDs | 3.8 ± 0.6 μM | 3.2 ± 0.5 μM |

As shown in Figures 2F,G, the luminescence signal from HNP1 human host defense peptide-attached GQDs decreases slowly as the concentration of the spike protein increases. By fitting the curve using eq 3, we have determined the binding affinity as 120 ± 20 nM in this case, as reported in Table 1.

To verify our data with a well-documented assay, we used the ELISA-like assay using the His-tag delta variant SARS-CoV-2 S1 protein.26,27 The experimental details are reported in the Supporting Information. As reported in Figure 2H, the plot shows the binding curve between the peptide-conjugated GQDs and spike protein in an ELISA plate-based assay. From the binding curve, we have estimated the binding affinity as 9 ± 1 nm for the delta variant spike with LL-37 and HNP1 peptide-conjugated GQDs, which matches very well with the fluorescence quenching data. Similarly, we have estimated the binding affinity for the delta variant spike with different peptide-conjugated GQDs, LL-37 and HNP1 peptides and ACE2, as reported in Table 1.

From the experimental data, we can conclude that the binding affinities for the delta variant spike with LL-37 peptide- and HNP1 peptide-attached GQDs are comparable with that for ACE2-delta variant spike binding. Also, the binding affinities for LL-37 peptide- and HNP1 peptide-attached GQDs are better than only one type of peptide-attached GQDs. The observed higher binding affinity of GQDs conjugated with both the peptides (HNP and LL-37) than GQDs conjugated with a single type of peptide can be due to the presence of multiple binding sites in the spike protein in the case of two peptide-attached GQDs. The reported theoretical modeling indicates that LL37 can bind to the spike-RBD in eight sites (LYS417, GLN493, THR500, ASN501, TYR505, THR500, ASN501, and GLY502).7,11 On the other hand, HNP1 can bind to the spike-RBD in six sites (LYS417, ALA475, PHE486, ASN487, TYR489, and GLN493).7,11 The observed higher binding may be due to the multiple binding site interaction.

During the past three years of pandemic, several new viral lineages such as alpha (B.1.1.7), beta (B.1.351), gamma (P1), delta (B.1.617.2), and omicron (B.1.1.529) variants had risen.1−6 To understand how the binding affinity between LL-37 & HNP1-attached GQDs and the SARS-CoV-2 S1 protein RBD of different variants varies, we have determined the effects of RBD mutations on the binding capability with peptide-attached GQDs. As reported in Table 2, our experimental data indicate that the binding affinity for the delta B.1.617.2 variant spike-RBD is higher than those for the alpha, beta, and gamma variant spike-RBD.

Table 2. Binding Affinity between the LL-37 & HNP1-Attached GQDs and SARS-CoV-2 S1 Protein RBD (Different Variants) Measured by Fluorescence Quenching and ELISA Assays.

| system | GQD-based fluorescence quenching | ELISA-like assay |

|---|---|---|

| alpha B.1.1.7 variant spike-RBD | 13 ± 1 nM | 14 ± 1 nM |

| beta B.1.351 variant spike-RBD | 11 ± 1 nM | 11 ± 1 nM |

| gamma P.1 variant spike-RBD | 12 ± 1 nM | 12 ± 1 nM |

| delta B.1.617.2 variant spike-RBD | 8 ± 1 nM | 9 ± 1 nM |

3.4. Demonstrating ACE2–Spike Protein Binding Blocking Using the B Pseudotyped SARS-CoV-2 Delta Variant (B.1.617.2) Virus

Next, to find out whether LL-37 peptide- and HNP1 peptide-attached GQDs can bind with delta variant SARS-CoV-2, we have performed an experiment using Baculovirus pseudotyped with a SARS-CoV-2 delta variant (B.1.617.2) spike protein. As shown in Figure 3A, the luminescence intensity from peptide-attached GQDs decreases abruptly in the presence of 1000 virus, which indicates that LL-37 peptide- and HNP1 peptide-attached GQDs can bind with Baculovirus pseudotyped SARS-CoV-2.

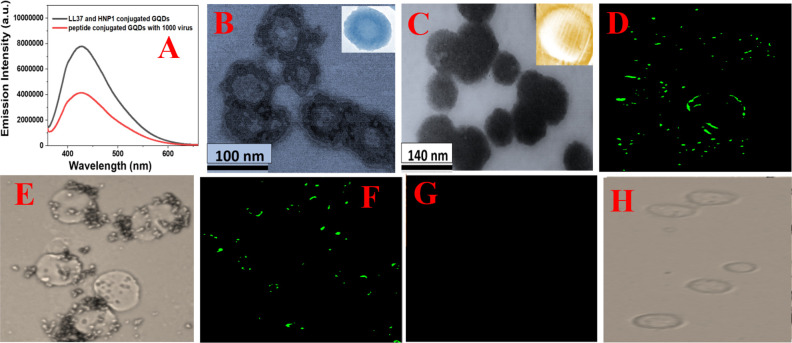

Figure 3.

(A) Fluorescence spectra from HNP1 and LL-37 peptide-conjugated GQDs in the presence and absence of GFP-tagged Baculovirus pseudotyped with a SARS-CoV-2 delta variant (B.1.617.2) spike protein. (B) TEM image of Baculovirus pseudotyped after they are treated with HNP1 human host defense peptide-attached GQDs for 30 min. (C) TEM image of Baculovirus pseudotyped after they are treated with HNP1 and LL-37 human host defense peptide-attached GQDs for 30 min. (D–H) Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein binding to the surface of HEK-293T cells expressing ACE2. The green fluorescence is due to the presence of GFP-tagged Baculovirus pseudotyped with a SARS-CoV-2 delta variant (B.1.617.2) spike protein on the surface of HEK-293T cells expressing ACE2. (D) Fluorescence image of HEK-293T cells in the presence of GFP-tagged pseudotyped delta virus without GQDs. (E) Bright-field image of HEK-293T cells in the presence of GFP-tagged Baculovirus pseudotyped without GQDs. (F) Fluorescence image of HEK-293T cells in the presence of GFP-tagged virus bound with LL-37 human host defense peptide-attached GQDs. (G) Fluorescence image of HEK-293T cells in the presence of GFP-tagged virus bound with LL-37 & HNP1 human host defense peptide-attached GQDs. (H) Bright-field image of HEK-293T cells in the presence of GFP-tagged virus bound with LL-37 & HNP1 human host defense peptide-attached GQDs.

As reported in Figure 3B,C, the TEM images indicate that peptide-conjugated GQDs are bound on the virus. Since the binding affinity for LL-37 peptide- and HNP1 peptide-attached GQDs are much higher than only HNP1-attached GQDs, we observed that much higher amounts of GQDs are bound on the virus when both peptides are attached on GQDs. After that, to determine whether HNP1 and LL-37 peptide-conjugated GQDs have the capability to prevent the delta variant virus entry into the host cells via blocking the spike protein RBD–ACE2 binding, we have used human embryonic kidney-239T cells with a high expression of ACE2 (HEK-293T). For this experiment, we have used GFP-tagged Baculovirus pseudotyped with a SARS-CoV-2 delta variant (B.1.617.2) spike protein (catalog number #C1123G). The experimental details are reported in the Supporting Information.26,27 As shown in Figure 3D, in the absence of peptide-attached GQDs, the pseudotyped delta variant virus binds with ACE2 on HEK-293T cells. The observed green fluorescence is due to the presence of GFP-tagged pseudotyped virus particles on the surface of HEK-293T cells via binding with ACE2. Figure 3E shows the bright-field image of HEK-293T cells, which indicates the presence of the pseudotyped virus on the cell surface. As shown in Figure 3H, in the presence of LL-37 and HNP1 peptide-attached GQDs, the pseudotyped delta variant virus cannot bind with ACE2 on HEK-293 T cells, and as a result, we have not observed any green fluorescence.

Since LL-37 and HNP1 peptide-attached GQDs have high binding affinity with the delta variant spike protein, the data shown above indicates that they can be used to completely block the binding between ACE2 and the spike protein. Due to the above fact, LL-37 and HNP1 peptide-attached GQDs have the capability for completely inhibiting the entry of delta variant SARS-CoV-2 pseudovirions into host cells. On the other hand, as reported in Figures 3F,G, LL-37 peptide-attached GQDs and HNP1 peptide-attached GQDs cannot completely block the virus spike protein–ACE2 binding. As reported in Figure 4B, the blocking capability decreases from 100 to 8% when only GQDs have been used. Also, the blocking ability correlates very nicely with the spike binding affinity, as reported in Table 1.

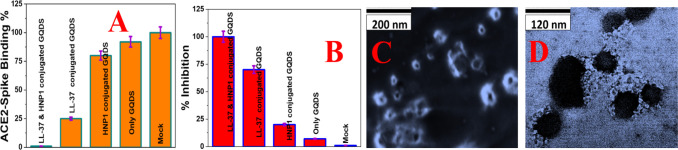

Figure 4.

(A) Interaction of Baculovirus pseudotyped with a SARS-CoV-2 delta variant (B.1.617.2) spike protein and ACE2 on HEK-293T cells, measured using fluorescence imaging. (B) Inhibition efficiency of Baculovirus pseudotyped with the delta variant spike protein in infected HEK293T cells in the presence of buffer (Mock), GQDs (30 μg/mL), HNP1 (4 μg/mL)-attached GQDs (30 μg/mL), LL-37 (4 μg/mL)-attached GQDs (30 μg/mL), and LL-37 (4 μg/mL) and HNP1 (4 μg/mL)-attached GQDs (30 μg/mL). (C) SEM image of Baculovirus pseudotyped with a SARS-CoV-2 delta variant (B.1.617.2) spike protein when they are treated with peptide-attached GQDs for 6 h. (D) TEM image of Baculovirus pseudotyped with a SARS-CoV-2 delta variant (B.1.617.2) spike protein when they are treated with peptide-attached GQDs for 12 h.

3.5. Determining the Inhibition Ability for LL-37 and HNP1 Peptide-Conjugated GQDs Using the B Pseudotyped SARS-CoV-2 Delta Variant (B.1.617.2) Virus

Next, we have estimated the inhibition ability for delta variant SARS-CoV-2 pseudovirions using peptide-conjugated GQDs. The experimental details are reported in the Supporting Information.13,14,26,27Figure 4B shows the % inhibition, which clearly shows that 100% inhibition was achieved in the case of LL-37 (4 μg/mL) and HNP1 (4 μg/mL)-attached GQDs (30 μg/mL). On the other hand, less than the 10% inhibition was achieved when only GQDs (30 μg/mL) were used.

The reported data in Table 3 and Figure 4B also indicate that 70% inhibition can be achieved when LL-37 (4 μg/mL) peptide-attached GQDs (30 μg/mL) were used. Similarly, using only the LL-37 (4 μg/mL) peptide, we have achieved 40% inhibition. From the reported inhibition data, we can conclude that the inhibition efficiencies for LL-37 and HNP1-attached GQDs are much higher than only one type of peptide-attached GQDs or only peptide or GQDs. To understand better about the above experimental observation, we have also performed TEM and SEM imaging experiments after LL-37 and HNP1-attached GQDs are exposed to the virus for 12 h. The SEM image in Figure 4C and the TEM image in Figure 4D clearly show that LL-37 and HNP1-attached GQDs can destroy the lipid membrane of Baculovirus pseudotyped with a SARS-CoV-2 delta variant (B.1.617.2) spike protein. Due to the above fact, the delta variant virus collapses and spike proteins that are attached on the lipid membrane are removed. The above process helps to stop the spread of the delta variant virus.

Table 3. Half-Maximal Inhibitory Concentration (IC50) for the Peptide-Conjugated GQDs, Only Peptide, and GQDs Using HEK293T Cells Expressing the ACE2 Receptor.

| system | IC50 |

|---|---|

| LL-37 & HNP1-attached GQDs | 30 μg/mL GQDs + 2 μg/mL LL-37 + 2 μg/mL HNP1 |

| LL-37-attached GQDs | 30 μg/mL GQDs + 3 μg/mL LL-37 |

| HNP1-attached GQDs | 30 μg/mL GQDs + 11 μg/mL HNP1 |

| LL-37 peptide | 4.5 μg/mL |

| HNP1 peptide | 13.8 μg/mL |

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, in the current article, we show that HNP1 and LL-37 peptide-conjugated GQDs can be used to prevent the delta variant virus entry into the host cells by blocking spike protein RBD binding with ACE2. We have demonstrated that peptide-attached GQD-based fluorescence quenching can be used for determining the binding affinity of the delta variant (B.1.617.2) spike protein. The reported experimental data show that the effective binding affinity between the HNP1 and LL-37 peptide-conjugated GQDs and delta variant spike protein is comparable with the ACE2–spike protein binding affinity. Using the alpha, beta, and gamma variant spike-RBD, we have shown that the binding affinity for the delta B.1.617.2 variant is higher than those for other variants. Our experimental observation using the HEK293T-human ACE2 cell line demonstrated that LL-37 and HNP1 peptide-conjugated GQDs have the capability for completely inhibiting the entry of delta variant SARS-CoV-2 pseudovirions into host cells and the inhibition efficiency for two peptide-attached GQDs is much higher than those for only one type of peptide-attached GQDs or only peptides or GQDs.

Acknowledgments

P.C.R. thanks NSF-RAPID grant no. DMR-2030439 and NSF-PREM grant no. DMR-1826886 for their generous funding. We also thank NIH-NIMHD grant no. 1U54MD015929-01 for the bioimaging core facility. R.T. is supported by NASA award (80NSSC19K1603) and COVID-19 funds from the University of Mississippi Medical Center.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.2c00113.

Design and characterization of the LL-37 and HNP1-attached GQDs and other experiments such as binding affinity measurement and virus inhibition experiments (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Altmann D. M.; Boyton R. J.; Beale R. Immunity to Sars-Cov-2 Variants of Concern. Science 2021, 371, 1103–1104. 10.1126/science.abg7404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- V’kovski P.; Kratzel A.; Steiner S.; Stalder H.; Thiel V. Coronavirus biology and replication: implications for SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 155–170. 10.1038/s41579-020-00468-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller K.; Girl P.; Giebl A.; von Buttlar H.; Dobler G.; Bugert J. J.; Gruetzner S.; Wölfel R. Emerging SARS-CoV-2 variant B. 1.1.7 reduces neutralisation activity of antibodies against wildtype SARS-CoV-2. J Clin Virol 2021, 142, 104912. 10.1016/j.jcv.2021.104912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P.; Nair M. S.; Liu L.; Iketani S.; Luo Y.; Guo Y.; Wang M.; Yu J.; Zhang B.; Kwong P. D.; Graham B. S.; Mascola J. R.; Chang J. Y.; Yin M. T.; Sobieszczyk M.; Kyratsous C. A.; Shapiro L.; Sheng Z.; Huang Y.; Ho D. D.; Ho D. D. Antibody resistance of SARS-CoV-2 variants B. 1.351 and B. 1.1. 7. Nature 2021, 593, 130–135. 10.1038/s41586-021-03398-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starr T. N.; Greaney A. J.; Addetia A.; Hannon W. W.; Choudhary M. C.; Dingens A. S.; Li J. Z.; Bloom J. D. Prospective Mapping of Viral Mutations That Escape Antibodies Used to Treat Covid-19. Science 2021, 371, 850. 10.1126/science.abf9302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontanet A.; Autran B.; Lina B.; Kieny M. P.; Karim S. S. A.; Sridhar D. SARS-CoV-2 variants and ending the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 2021, 397, 952–954. 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00370-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomplun S.; Jbara M.; Quartararo A. J.; Zhang G.; Brown J. S.; Lee Y. C.; Ye X.; Hanna S.; Pentelute B. L. Novo Discovery of High-Affinity Peptide Binders for the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein. ACS Cent. Sci. 2021, 7, 156–163. 10.1021/acscentsci.0c01309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F.; Neuenschwander P. F.; Idell S.; Vankayalapati R.; Jain K. G.; Du K.; Ji H.; Yi G. Phage Display-Derived Peptide for the Specific Binding of SARS-CoV-2. ACS Omega 2021, 7, 3203. 10.1021/acsomega.1c04873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (ASAP Article)

- Gangadevi S.; Badavath V. N.; Thakur A.; Yin N.; De Jonghe S.; Acevedo O.; Jochmans D.; Leyssen P.; Wang K.; Neyts J.; Yujie T.; Blum G. Kobophenol A Inhibits Binding of Host ACE2 Receptor with Spike RBD Domain of SARS-CoV-2, a Lead Compound for Blocking COVID-19. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2021, 12, 1793–1802. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.0c03119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ai X.; Wang D.; Honko A.; Duan Y.; Gavrish I.; Fangh R. H.; Griffiths A.; Gao W.; Zhnag L. Surface Glycan Modification of Cellular Nanosponges to Promote SARS-CoV-2 Inhibition. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 17615–17621. 10.1021/jacs.1c07798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C.; Wang S.; Li D.; Chen P.; Han S.; Zhao G.; Chen Y.; Zhao J.; Xiong J.; Qiu J.; Wei D. Q.; Zhao J.; Wang J. Human Cathelicidin Inhibits SARS-CoV-2 Infection: Killing Two Birds with One Stone. ACS Infect. Dis. 2021, 7, 1545–7,1554. 10.1021/acsinfecdis.1c00096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T.; Fang X.; Wen T.; Liu J.; Zhai Z.; Wang Z.; Meng J.; Yang Y.; Wang C.; Xu H. Synthetic Neutralizing Peptides Inhibit the Host Cell Binding of Spike Protein and Block Infection of SARS-CoV-2. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 14887–14894. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c01440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pramanik A.; Gao Y.; Patibandla S.; Mitra D.; McCandless M. G.; Fassero L. A.; Gates K.; Tandon R.; Ray P. C. Aptamer conjugated gold nanostar-based distance-dependent nanoparticle surface energy transfer spectroscopy for ultrasensitive detection and inactivation of corona virus. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2021, 12, 2166–2171. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.0c03570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pramanik A.; Gao Y.; Patibandla S.; Mitra D.; McCandless M. G.; Fassero L. A.; Gates K.; Tandon R.; Chandra Ray P. The rapid diagnosis and effective inhibition of coronavirus using spike antibody attached gold nanoparticles. Nanoscale Adv. 2021, 3, 1588–1596. 10.1039/D0NA01007C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C.; Wang S.; Li D.; Wei D. Q.; Zhao J.; Wang J. Human Intestinal Defensin 5 Inhibits SARS-CoV-2 Invasion by Cloaking ACE2. Gastroenterology 2020, 159, 1145–1147.e4. 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y.; Pramanik A.; Patibandla S.; Gates K.; Hill G.; Ignatius A.; Ray P. C. Development of Human Host Defense Antimicrobial Peptide-Conjugated Biochar Nanocomposites for Combating Broad-Spectrum Superbugs. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2020, 3, 7696–7705. 10.1021/acsabm.0c00880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock R. E. W.; Haney E. F.; Gill E. E. The immunology of host defence peptides: Beyond antimicrobial activity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 321–334. 10.1038/nri.2016.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unal M. A.; Bayrakdar F.; Nazir H.; Besbinar O.; Gurcan C.; Lozano N.; Arellano L. M.; Yalcin S.; Panatli O.; Celik D.; Alkaya D.; Agan A.; Fusco L.; Suzuk Yildiz S.; Delogu L. G.; Akcali K. C.; Kostarelos K.; Yilmazer A. Graphene Oxide Nanosheets Interact and Interfere with SARS-CoV-2 Surface Proteins and Cell Receptors to Inhibit Infectivity. Small 2021, 17, 2101483. 10.1002/smll.202101483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda M.; Islam S.; Shimizu R.; Nassar H.; Rabin N.; Takahashi Y.; Sekine Y.; Lindoy L.; Fukuda T.; Ikeda T.; Hayami S. Lethal Interactions of SARS-CoV-2 with Graphene Oxide: Implications for COVID-19 Treatment. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2021, 4, 11881. 10.1021/acsanm.1c02446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (ASAP Article)

- Li S.; Aphale A. N.; Macwan I. G.; Patra P. K.; Gonzalez W. G.; Miksovska J.; Leblanc R. M. Graphene Oxide as a Quencher for Fluorescent Assay of Amino Acids, Peptides, and Proteins. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2012, 4, 7069–7075. 10.1021/am302704a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pramanik A.; Jones S.; Pedraza F.; Vangara A.; Sweet C.; Williams M. S.; Ruppa-Kasani V.; Risher S. E.; Sardar D.; Ray P. C. Fluorescent, Magnetic Multifunctional Carbon Dots for Selective Separation, Identification, and Eradication of Drug-Resistant Superbugs. ACS Omega 2017, 2, 554–562. 10.1021/acsomega.6b00518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vangara A.; Pramanik A.; Gao Y.; Gates K.; Begum S.; Chandra Ray P. Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer Based Highly Efficient Theranostic Nanoplatform for Two-Photon Bioimaging and Two-Photon Excited Photodynamic Therapy of Multiple Drug Resistance Bacteria. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2018, 1, 298–309. 10.1021/acsabm.8b00071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacharias M.; Kelires P. C. Quantum Confinement of Electron–Phonon Coupling in Graphene Quantum Dots. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2021, 12, 9940–9946. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.1c02899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rostock L.; Driller R.; Grätz S.; Kerwat D.; von Eckardstein L.; Petras D.; Kunert M.; Alings C.; Schmitt F.-J.; Friedrich T.; Wahl M. C.; Loll B.; Mainz A.; Süssmuth R. D. Molecular insights into antibiotic resistance - how a binding protein traps albicidin. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3095. 10.1038/s41467-018-05551-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakar A. K.; Feroz R. S. A critical view on the analysis of fluorescence quenching data for determining ligand–protein binding affinity. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2019, 223, 117337. 10.1016/j.saa.2019.117337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tandon R.; Mitra D.; Sharma P.; McCandless M. G.; Stray S. J.; Bates J. T.; Marshall G. D. Effective screening of SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies in patient serum using lentivirus particles pseudotyped with SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 19076. 10.1038/s41598-020-76135-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tandon R.; Sharp J. S.; Zhang F.; Pomin V. H.; Ashpole N. M.; Mitra D.; McCandless M. G.; Jin W.; Liu H.; Sharma P.; Linhardt R. J. Effective Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 Entry by Heparin and Enoxaparin Derivatives. J. Virol. 2021, 95, e01987–e01920. 10.1128/JVI.01987-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.