Abstract

The biological functions of cholesterol are diverse, ranging from cell membrane integrity, cell membrane signaling, and immunity to the synthesis of steroid and sex hormones, vitamin D, bile acids, and oxysterols. Multiple studies have demonstrated hypocholesterolemia in sepsis, the degree of which is an excellent prognosticator of poor outcomes. However, the clinical significance of hypocholesterolemia has been largely unrecognized. We undertook a detailed review of the biological roles of cholesterol, the impact of sepsis, its reliability as a prognosticator in sepsis, and the potential utility of cholesterol as a treatment. Sepsis affects cholesterol synthesis, transport, and metabolism. This likely impacts its biological functions, including immunity, hormone and vitamin production, and cell membrane receptor sensitivity. Early preclinical studies show promise for cholesterol as a pleiotropic therapeutic agent. Hypocholesterolemia is a frequent condition in sepsis and an important early prognosticator. Low plasma concentrations are associated with wider changes in cholesterol metabolism and its functional roles, and these appear to play a significant role in sepsis pathophysiology. The therapeutic impact of cholesterol elevation warrants further investigation.

Keywords: sepsis, cholesterol, hypocholesterolemia, lipid metabolism

Sepsis, the dysregulated host response to infection resulting in organ dysfunction (1), is a major worldwide cause of mortality (2) and morbidity. Current management focuses on adequate fluid resuscitation, organ support, and treating the infection with antibiotics and source control. To date, no available treatments that directly target underlying pathophysiological mechanisms have been clearly demonstrated to improve outcomes.

Cholesterol, a sterol lipid, plays an integral role in multiple body functions, including maintenance of cellular membrane processes, immunity, signaling, and pathway regulation, and acts as a precursor for the synthesis of steroid hormones, vitamin D, bile acids, and oxysterols. Sepsis-induced hypocholesterolemia was first recognized a century ago (3); multiple studies demonstrate a worse prognosis being associated with the magnitude of decline. However, the mechanisms by which plasma concentrations fall, the impact on organ functionality, the relationship of plasma cholesterol to intracellular concentrations, and the potential role of cholesterol as a therapeutic all require elucidation.

There is increasing interest in the therapeutic possibilities of lipoproteins and modulation of cholesterol transport in sepsis, particularly in immunoinflammatory modulation and pathogen scavenging. There has, however, been little focus on cholesterol itself rather than on its carriers. In this article, we provide an overview of the biology of cholesterol, its possible roles in sepsis pathophysiology, and its potential utility as a specific adjunctive treatment.

Cholesterol Synthesis, Structure, Metabolism, and Functional Roles

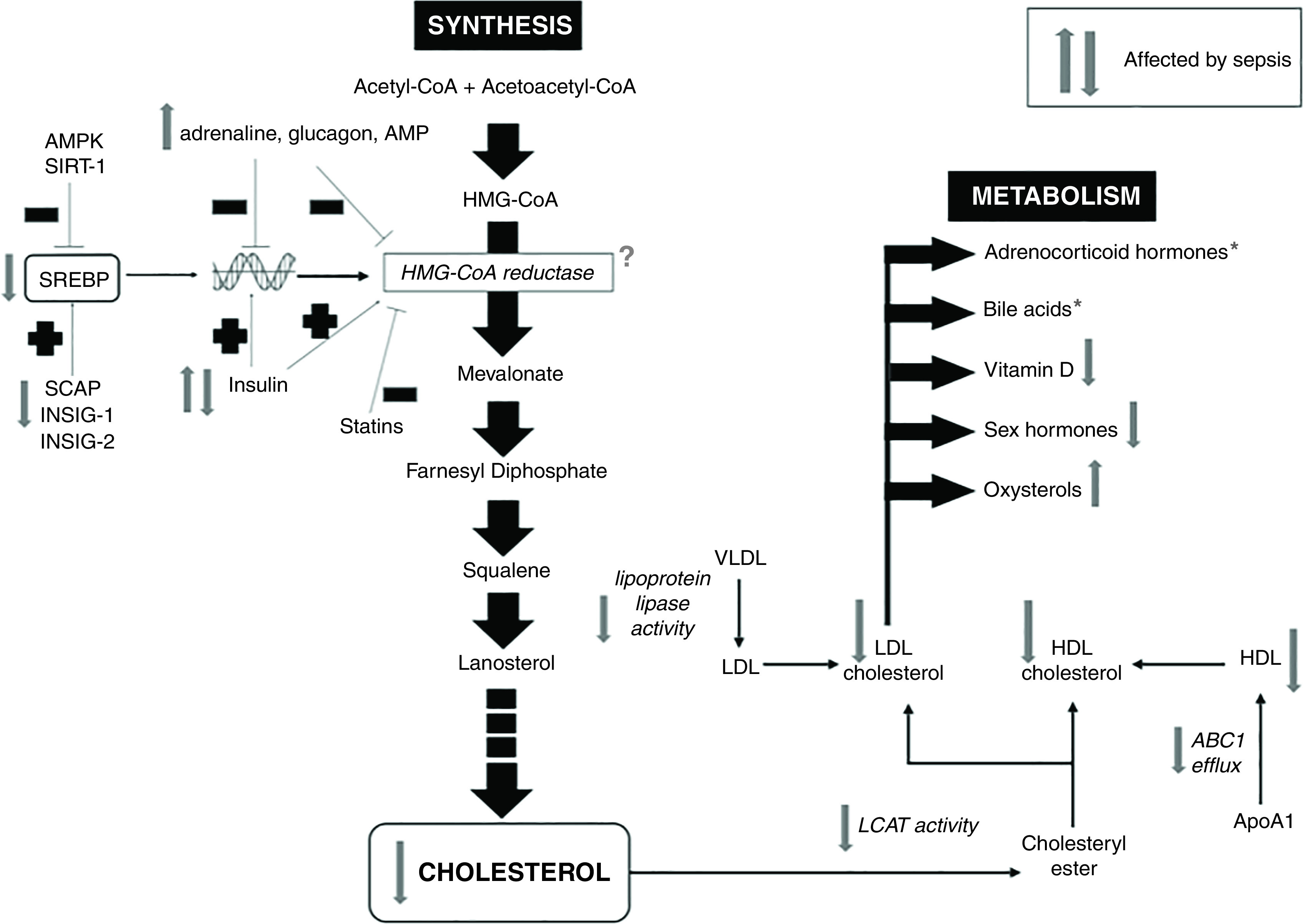

Cholesterol consists of four linked aromatic hydrophobic rings, a small hydrophilic hydroxyl group, and a hydrophobic chain. Because of its high hydrophobicity, cholesterol is only present within cells predominantly as a component of lipid membranes or bound to lipid-binding proteins (4) (Figure 1). Animals obtain cholesterol through diet and, primarily, by endogenous synthesis. Cholesterol synthesis is a multistep (∼30-reaction) process that is highly energy consuming; synthesis of one cholesterol molecule requires 18 acetyl-CoA, 36 ATP, 16 NADPH, and 11 oxygen molecules. Endogenous cholesterol synthesis is tightly regulated by negative feedback (Figure 2). HMG-CoA (hydroxymethylglutaryl–coenzyme A) reductase, the target of statin therapy, is the rate-limiting enzyme within the pathway and the predominant mechanism by which cells adapt to changes in cholesterol bioavailability.

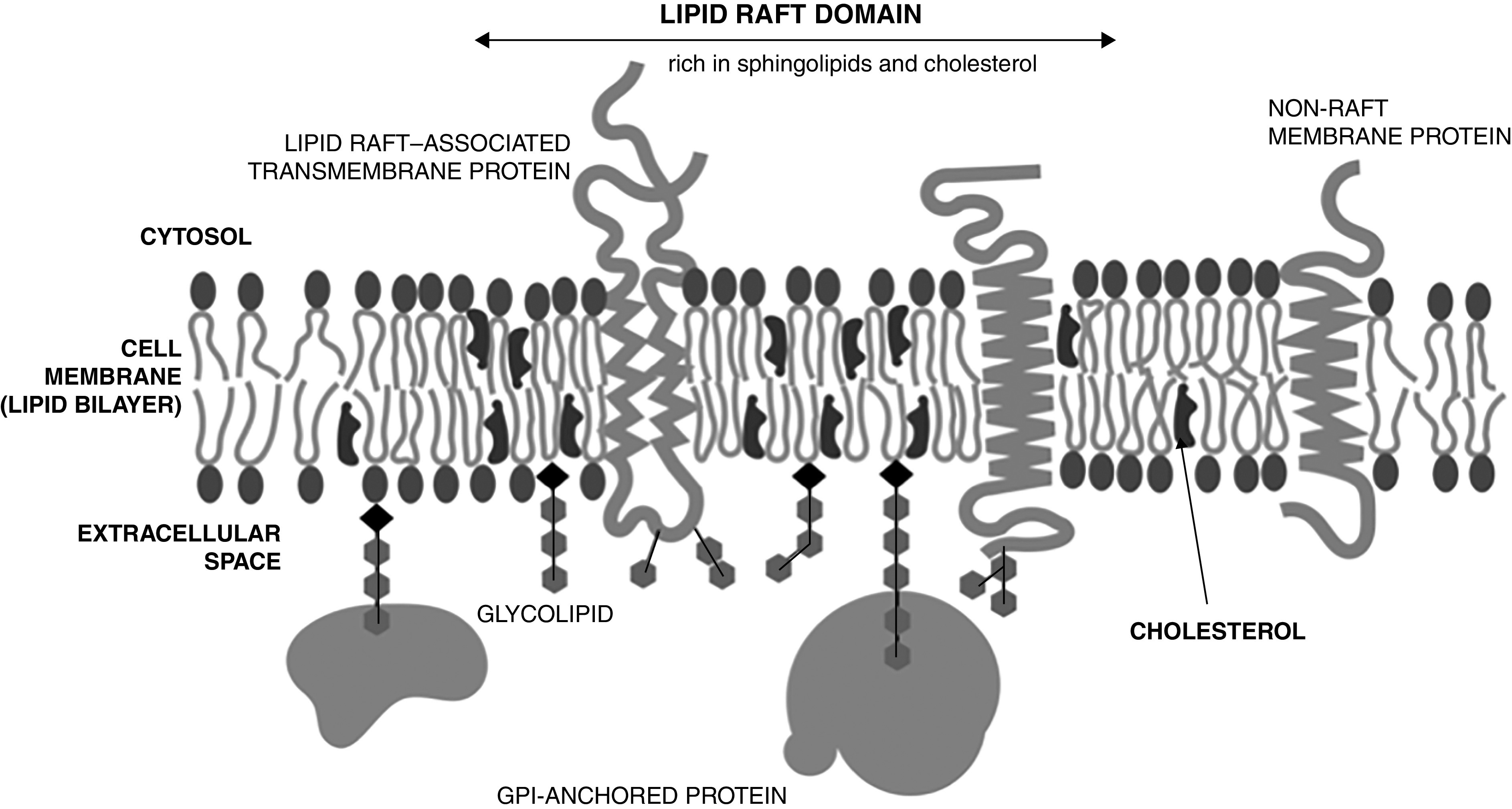

Figure 1.

Cholesterol structure and location within cell membranes. GPI = glycosylphosphatidylinositol.

Figure 2.

Cholesterol synthesis and metabolism pathways and impact of sepsis. *Plasma concentrations may be normal or raised for adrenocorticoid hormones and bile acids, but this may relate to decreased metabolism and/or excretion rather than to increased production. Cortisol concentrations frequently fail to augment with exogenous ACTH (adrenocorticotropic hormone) stimulation. The question mark represents uncertain effect. ABC1 = ATP-binding cassette transporter 1; AMPK = AMP-activated protein kinase; ApoA1 = apolipoprotein A1; HDL = high-density lipoprotein; HMG-CoA = hydroxymethylglutaryl–coenzyme A; INSIG = insulin-induced gene 1 protein; LCAT = lecithin–cholesterol acyltransferase; LDL = low-density lipoprotein; SCAP = SREBP cleavage–activating protein; SIRT-1 = sirtuin 1; SREBP = sterol regulatory element–binding protein; VLDL = very-low-density lipoprotein.

To enable transport in plasma, cholesterol must be bound to lipoproteins or albumin. Lipoproteins are categorized into chylomicrons, chylomicron remnants, VLDL (very-low-density lipoprotein), LDL (low-density lipoprotein), and HDL (high-density lipoprotein) by density, size, and the types of particle-forming proteins and other associated proteins. Cholesterol bound to LDL is transported from the liver to peripheral tissues, whereas HDL carries cholesterol to the liver and steroidogenic tissues—“reverse cholesterol transport” (4). Mammalian cells lack an enzyme system to catabolize and recycle cholesterol and its derivates. The liver clears cholesterol from the circulation via LDL and HDL receptors (5). It is then metabolized or excreted either unmodified or as bile acids, a large proportion of which are reabsorbed.

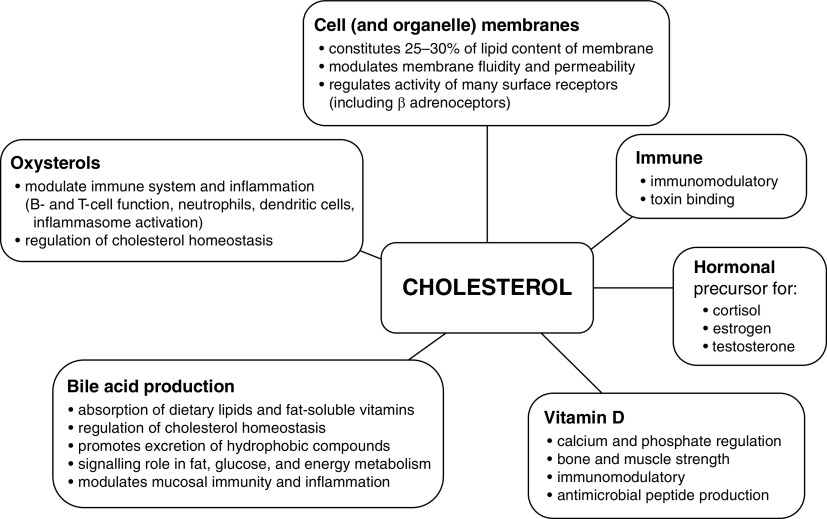

Cholesterol and its metabolites provide multiple biological functions (Figure 3):

Figure 3.

Functional roles of cholesterol.

-

1.

Cholesterol is an integral part of cell membranes and plays a crucial role in modulating membrane thickness, permeability, fluidity, and functionality (6, 7). Within the membrane, cholesterol distributes nonhomogeneously, accumulating within lipid rafts. These small, highly dynamic, sterol- and sphingolipid-enriched membrane microdomains attract many transmembrane proteins, such as ion channels, transporters, and receptors, including GPCRs (G-protein–coupled receptors) (7). Alterations in membrane cholesterol affect the membrane’s physical properties and influence the presence and activity of transmembrane proteins, such as the sodium–potassium–ATPase and β-adrenergic receptors (7).

-

2.

Both cholesterol and its lipoprotein carriers have immunomodulatory properties, including binding of endotoxin and other toxins (8, 9). This scavenging mechanism may play an important role in neutralizing toxins as part of the innate immune system response, preventing activation of TLRs (Toll-like receptors) by pathogen-associated molecular patterns. Of note, key receptors regulating the immune response such as TLRs and T- and B-cell receptors are localized within lipid rafts (10).

-

3.

Cholesterol is the only steroidogenic substrate used to synthesize adrenocortical hormones (glucocorticoids, aldosterone), sex hormones (e.g., estrogen, progesterone, testosterone), and vitamin D through multistep processes (11). During a triggered stress response, ∼80% of circulating cortisol may be derived from plasma cholesterol (12). The impact of vitamin D on multiple diseases, including musculoskeletal disorders, insulin resistance, and metabolic syndrome, and on cardiovascular and immunological dysfunction has been studied extensively (13).

-

4.

Conversion of cholesterol to bile acids involves 17 distinct enzymatic steps within hepatocytes and is the principal route of cholesterol metabolism. Bile acids undergo enterohepatic recirculation, allowing recycling, with de novo hepatocyte synthesis compensating for physiological intestinal losses. Bile acids aid metabolite excretion by the liver; aid the absorption of lipids, hydrophobic nutrients, and fat-soluble vitamins; and prevent bacterial overgrowth within the small bowel and biliary tree. They also regulate multiple functions within various liver cell types (e.g., cell differentiation and regeneration) (14).

-

5.

Oxysterols represent a large family of oxidized derivatives of cholesterol with multiple biological actions, including immunomodulation (15). Cholesterol can be oxidized either enzymatically or nonenzymatically by reactive oxygen species. Oxysterols can exert their functions through GPCRs, nuclear receptors, and other molecular pathways, regulating many processes, ranging from cytokine production to virus entry into cells (16, 17). Oxysterols modulate neutrophil, B-cell, and T-cell functionality, enhance innate immunity, and regulate production of the antiinflammatory cytokine IL-10 (17, 18).

Cholesterol Concentrations Fall during Sepsis, in Line with Severity and Outcome

Reductions in total plasma cholesterol, HDL cholesterol (HDL-C), and LDL cholesterol (LDL-C) are well recognized in sepsis (19–28). Concentrations are decreased at the time of diagnosis (21) and often decline further during the disease course (25). Serum HDL-C concentrations reach a nadir around Day 3 after admission, whereas LDL-C is lowest at the time of diagnosis (21). Variable recovery in serum concentrations occurs over subsequent days (25). The kinetics of VLDL cholesterol (VLDL-C) in sepsis are poorly characterized in human sepsis.

Multiple studies report a greater mortality risk in patients with lower concentrations of total cholesterol, HDL-C, and LDL-C (23–28). Of note, a recent genetic study suggested that low LDL concentrations in sepsis may be associative with rather than causal of an increased mortality risk (27), whereas low HDL-C may be a causal factor (29). Increased LDL clearance may contribute to a lower sepsis mortality via enhanced pathogen lipid clearance (27).

Survivors show a slow return to almost normal values over the disease course. The magnitude of falling is associated with a higher incidence of multiorgan dysfunction, an increased-duration ICU stay, and more nosocomial infection (23, 26). Elevated serum markers of inflammation correlate negatively with cholesterol concentrations (20, 24, 28).

Infusion of recombinant TNF-α or IL-6 into patients with cancer also produced large falls in plasma cholesterol in inverse correlation with markers of inflammation (30, 31). Animal experiments can replicate these findings and can be used as a therapeutic test bed. However, this is model dependent, as some rodent models injected with endotoxin or TNF-α actually demonstrate hypercholesterolemia (32). However, we and others have found large falls in total cholesterol and HDL-C concentrations in rats given a more realistic peritonitis insult (33–35). Hypocholesterolemia has also been demonstrated in septic models by using primates, sheep, and dogs (36–38).

Why Does Serum Cholesterol Fall in Sepsis?

Biological mechanisms leading to hypocholesterolemia in sepsis remain incompletely understood. Apart from decreased intake and impaired intestinal absorption of fat in critical illness (39), decreased synthesis, impaired cholesterol transport, increased metabolism, and depletion through toxin scavenging may be implicated.

Data on the impact of sepsis on cholesterol synthesis are limited and conflicting. Older studies in rodent models reported increased hepatic cholesterogenesis (32, 40) and concurrent hypercholesterolemia (32). Vasconcelos and colleagues (40), however, noted a decrease in HMG-CoA reductase activity in septic rats compared with healthy, fed rats. Our currently unpublished data (A. Kleyman and colleagues, unpublished results) reveal decreased mRNA expression of transcriptional regulators (SREBP-1 [sterol regulatory element–binding protein], SREBP-2, INSIG [insulin-induced gene 1 protein]) and enzymes (HMG-CoA reductase) within the hepatic cholesterol synthesis pathway in our rat peritonitis model.

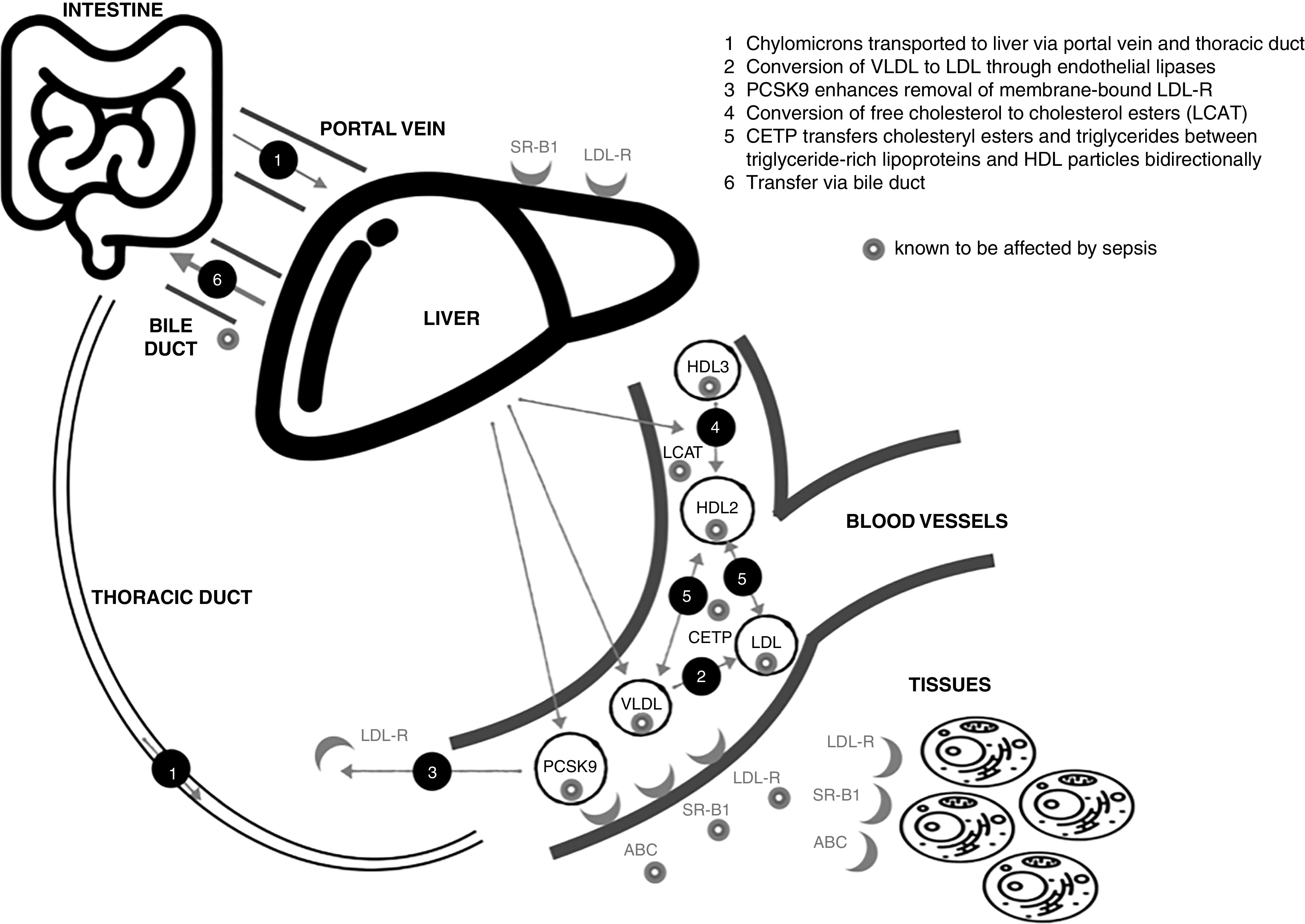

Proinflammatory cytokines may contribute to hypocholesterolemia by reducing hepatic synthesis of apolipoproteins that bind cholesterol to form lipoproteins (41). Falls in plasma LDL-C are commonly but variably reported, whereas low HDL-C is a consistent finding. Those changes suggest that reverse cholesterol transport (i.e., transfer of cholesterol from peripheral tissues to the liver) may be more affected (19). Figure 4 illustrates different cholesterol metabolic and transfer pathways affected by sepsis. Transporters (e.g., the ABC [ATP-binding cassette transporter] superfamily, which transforms lipid-poor apoA-1 [apolipoprotein A1] particles into mature HDL particles) and enzymes such as LCAT (lecithin–cholesterol acyltransferase), which converts free cholesterol to more hydrophobic cholesterol esters, enabling incorporation into HDL, are affected by sepsis (22, 41). The binding capacity of HDL is also affected by alterations in its structure and protein composition and by the accumulation of oxidized lipids (42).

Figure 4.

Impact of sepsis on cholesterol transport. ABC = ATP-binding cassette transporter; CETP = cholesteryl ester transfer protein; HDL = high-density lipoprotein; LCAT = lecithin–cholesterol acyltransferase; LDL = low-density lipoprotein; LDL-R = LDL receptor; PCSK9 = proprotein convertase subtilisin kexin 9; SR-BI = scavenger receptor B type 1; VLDL = very-low-density lipoprotein.

CETP (cholesteryl ester transfer protein) mediates triglyceride and cholesteryl ester transfer between triglyceride-rich lipoproteins and HDL particles, with lower plasma CETP concentrations increasing the proportion of HDL-C. However, total circulating cholesterol concentrations are unaffected (43). The literature on the relevance of changes in plasma CETP concentrations in sepsis and their relationship to outcomes is conflicting (29, 44–46).

Similarly, conflicting patient data are seen with regard to alterations in plasma concentrations of PCSK9 (proprotein convertase subtilisin kexin 9), an enzyme that degrades hepatic LDL and adipocyte VLDL receptors, resulting in hypercholesterolemia (47–49).

Cholesterol metabolism can be increased in sepsis by enzymatic and nonenzymatic oxidation. Cholesterol-25-hydroxylase is strongly induced by inflammation and its product, 25-hydroxycholesterol (50). The acute-phase protein PLA2 (phospholipase A2) activity rises during inflammation and promotes increased metabolism of cholesterol esters and apolipoproteins, thereby reducing serum cholesterol (51). PLA2 activity is enhanced by another acute-phase reactant, SAA (serum amyloid A), which also affects cholesterol transport (52). Sepsis, however, decreases bile flow (53). Impaired biotransformation and hepatobiliary transport of bile acids occur within hours of the induction of polymicrobial sepsis (54). As a consequence, bile acids can be elevated in the blood compartment.

Impact of Sepsis on the Biological Roles of Cholesterol

As described earlier, cholesterol and its various metabolites exert many complex biological functions, many of which are disrupted during sepsis. The specific contribution of cholesterol deficiency to these abnormalities requires further elucidation, but there is sufficient direct and circumstantial evidence to suggest that cholesterol deficiency may play an important role.

Cell Membrane Function

The cholesterol composition within lipid rafts modifies intrinsic function and downstream signaling, such as within the adrenergic receptor pathway. Cholesterol depletion in human neutrophil cell membranes induced a more proinflammatory phenotype that included priming, enhanced activation, increased adhesion, and oxidant production (55, 56). Raft-dependent signaling of multiple cell types may be altered because of changes in membrane cholesterol concentrations affecting, for example, GPCR density and activity (6, 7). This may be of particular relevance in septic shock, for which myocardial and vascular hyporeactivity to exogenous catecholamines is a defining characteristic, with the magnitude of hyporesponsiveness being associated with increased mortality (57).

Immunomodulatory and Antibacterial Properties of Cholesterol

Notwithstanding the scavenging and immunosuppressive roles of HDL and other lipoproteins, low cholesterol may itself negatively impact innate and adaptive immune cells (58). Intracellular cholesterol plays a pivotal role in TLR signaling in macrophages (59). The cholesterol concentration within membrane lipid rafts significantly impacts the raft concentrations of TLR-4 and TLR-9 (59). Depletion of the ABC-A1 transporter in knockout macrophages, impacting intracellular cholesterol transport, was associated with enlarged, cholesterol-containing lipid rafts that were rich in TLR-4 and hyperresponsive to LPS (59). In lymphocytes, enrichment of cholesterol in lipid rafts was associated with increased formation of an immune synapse between signaling complexes and T-cell receptors. Low serum and low membrane cholesterol concentrations also influence natural-killer-cell function (60).

Steroid, Sex Hormone, and Vitamin D Deficiency

Adrenal insufficiency is a recognized complication in patients with sepsis and septic shock and is associated with increased mortality (61). Even though plasma cortisol concentrations are frequently raised, there is decreased responsiveness to ACTH stimulation, particularly in eventual nonsurvivors (62), suggesting the possibility of diminished reserves. As mentioned earlier, some 80% of circulating cortisol during stress is derived from plasma cholesterol (12). The contribution of hypocholesterolemia in sepsis is uncertain, as the downstream cortisol production pathway may also be compromised because of, for example the expression of StAR (steroidogenic acute regulatory protein), the rate-limiting step in steroidogenesis, which orchestrates transport of cholesterol from outer to inner mitochondrial membranes (63). Pharmacological suppression of HDL-C does, however, disrupt adrenal steroidogenesis (64). Nonetheless, human data are conflicting (65–67).

Falls in sex hormone (68) and vitamin D concentrations (69) are also well recognized in sepsis and carry prognostic and potential therapeutic implications. Pharmacological activation of the estrogen receptor β improved survival in pneumonia and peritonitis models of sepsis (70). Administration of high-dose vitamin D to critically ill patients with severe vitamin D deficiency has produced conflicting outcomes (71, 72). An association has been described between low cholesterol and low testosterone in male patients with septic shock (73); however, the causation remains unclear. Low LDL-C concentrations have also been linked to low testosterone concentrations in chronically ill patients (68).

Bile Acids

Impaired biotransformation and hepatobiliary transport of bile acids occur within hours after the induction of polymicrobial sepsis (54). In septic patients, bile acids are significantly elevated and predictive of poor outcomes (74). This appears to relate to diminished or even obstructed bile flow from the liver rather than to increased synthesis. To what extent changes in cholesterol concentrations in different body compartments during sepsis alter the complex mechanisms of bile acid metabolism remains to be elucidated.

Cholesterol Supplementation and Lipoprotein Therapies

The idea of a lipid treatment for infection is not new, whether this be cholesterol, HDL or analogs, oxysterols, or phospholipid emulsions. Indeed, Bayer took out a patent for cholesterol therapy for blackwater fever (malaria) in 1910. The possible impact of cholesterol therapy on a wide range of infectious diseases was suggested soon after (75).

Published studies remain relatively scanty and are often based on model systems. What benefit derives from the lipoprotein itself or from elevation of cholesterol concentrations is unclear.

Cholesterol nanoparticles elevated intracellular concentrations and prevented the cytotoxic effect of the pneumococcal antigen, pneumolysin, on hepatocytes (76). Administration of 25-hydroxycholesterol decreased the viral load and improved outcomes in a porcine viral pneumonitis model (77). In terms of carriers of cholesterol, intravenous application of reconstituted HDL or HDL mimetics (based on apoA-1) reduced organ damage and improved hemodynamics and survival in a variety of septic or endotoxemic rodent models (35, 78–83). Inhibition of CETP with anacetrapib preserved HDL-C concentrations and improved survival in septic mice (46). Pharmacological inhibition of PCSK9 has, however, delivered variable results. Whereas improved survival was noted in a murine polymicrobial peritonitis model (47), no protection was afforded in a murine endotoxin model (84).

Human studies are limited. Reconstituted HDL decreased proinflammatory cytokine release in human volunteers with endotoxemia (85). A multicenter study enrolling nearly 1,400 patients with presumed Gram-negative sepsis (86) reported that a 10% phospholipid–lipoprotein emulsion that contained no cholesterol, given with the aim of neutralizing endotoxin, failed to deliver any benefit. A two-center phase I/II clinical protocol in which an antiinflammatory lipid emulsion containing fish oil is being administered intravenously to septic patients with the objective of raising plasma cholesterol concentrations has been recently published (87). The impact of cholesterol infusions on lipoprotein concentrations (HDL-C, LDL-C, and VLDL-C) remains unknown. More experimental in vitro and in vivo studies are needed to address mechanisms, feasibility, dose-finding, and possible adverse events.

Statin Therapy for Sepsis—Is There a Paradox?

How can the above arguments related to cholesterol therapy be reconciled with the putative benefits of treating critical illness with statins, agents that are conventionally used to treat hypercholesterolemia? Statins inhibit HMG-CoA reductase, the rate-limiting enzyme in the mevalonate pathway that commences with acetyl-CoA. This pathway later splits into branches that synthesize cholesterol, heme A, ubiquinone, dolichol, and other isoprenoids. Statins also affect other pathways that are either directly related to or are not related to mevalonate, such as endothelial NO synthase activation (88). Thus, other than lowering cholesterol, statins have multiple other immunomodulatory, antinflammatory, and metabolic effects, such as activation of PPARs, increased production of endothelial NO, reduced synthesis of endothelin 1 and thromboxane A2, and NADPH oxidase inactivation (88–90). These may be both beneficial or harmful; for example, statin-induced myopathy has been linked to reductions in ubiquinone and thus mitochondrial functionality or to alterations in sarcolemma and/or membrane-binding proteins (91). The impact of statins on mortality in cardiovascular disease specifically related to cholesterol lowering is questioned (92).

With respect to sepsis, epidemiological studies reported an association with improved survival from sepsis in patients receiving preexisting statin treatment; however, this likely relates to population lifestyle differences (93–95). Two randomized, controlled, multicenter trials found no benefit from de novo statin therapy in sepsis (96, 97). Notably, plasma cholesterol concentrations were markedly subnormal in both the atorvastatin group and the control group (2.4 vs. 2.6 mmol/L, respectively) (96). The HARP-2 (Hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA Reductase Inhibition with Simvastatin in Acute Lung Injury to Reduce Pulmonary Dysfunction 2) trial of patients with ARDS, of whom 40% had sepsis, showed no outcome effect from simvastatin (98). Of note, a post hoc analysis suggested that patients with a hyperinflammatory phenotype could benefit (99), indicating that non–cholesterol-lowering effects may be more pertinent. On the basis of current evidence, we cannot recommend continuation or addition of statins in sepsis; prospective randomized studies are needed to clarify their potential utility in specific patient subsets.

Conclusions

Low cholesterol concentrations are a well-recognized manifestation of sepsis and septic shock. The magnitude of hypocholesterolemia relates to the disease severity and outcome and is an early prognostic marker. Several pathophysiological mechanisms can participate in the development of hypocholesterolemia in sepsis and its impact on multiple downstream biochemical pathways. Further studies are needed to extend our knowledge about the importance and interactions of these mechanisms and the role of cholesterol with or without lipoproteins as therapeutics.

Footnotes

Supported by the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine Established Investigator Award, the University College London Therapeutic Acceleration Support Fund, and the Medical Research Council Confidence in Concept Award.

Author Contributions: M.S. conceived the idea for the article. D.A.H. performed the initial literature search and drafted the first version of the manuscript. D.A.H., A.K., A.P., M.B., and M.S. revised subsequent drafts of the manuscript. All authors have approved the final version to be published.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.202105-1197TR on October 29, 2021

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1. Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3) JAMA . 2016;315:801–810. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rudd KE, Johnson SC, Agesa KM, Shackelford KA, Tsoi D, Kievlan DR, et al. Global, regional, and national sepsis incidence and mortality, 1990-2017: analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet . 2020;395:200–211. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32989-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Macadam W, Shiskin C. The cholesterol content of the blood in relation to genito-urinary sepsis. Proc R Soc Med . 1924;17:53–55. doi: 10.1177/003591572401702314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ikonen E. Cellular cholesterol trafficking and compartmentalization. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol . 2008;9:125–138. doi: 10.1038/nrm2336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shen WJ, Asthana S, Kraemer FB, Azhar S. Scavenger receptor B type 1: expression, molecular regulation, and cholesterol transport function. J Lipid Res . 2018;59:1114–1131. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R083121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jafurulla M, Chattopadhyay A. Membrane lipids in the function of serotonin and adrenergic receptors. Curr Med Chem . 2013;20:47–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Allen JA, Halverson-Tamboli RA, Rasenick MM. Lipid raft microdomains and neurotransmitter signalling. Nat Rev Neurosci . 2007;8:128–140. doi: 10.1038/nrn2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Morin EE, Guo L, Schwendeman A, Li XA. HDL in sepsis: risk factor and therapeutic approach. Front Pharmacol . 2015;6:244. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2015.00244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Guo L, Ai J, Zheng Z, Howatt DA, Daugherty A, Huang B, et al. High density lipoprotein protects against polymicrobe-induced sepsis in mice. J Biol Chem . 2013;288:17947–17953. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.442699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Varshney P, Yadav V, Saini N. Lipid rafts in immune signalling: current progress and future perspective. Immunology . 2016;149:13–24. doi: 10.1111/imm.12617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Payne AH, Hales DB. Overview of steroidogenic enzymes in the pathway from cholesterol to active steroid hormones. Endocr Rev . 2004;25:947–970. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Borkowski AJ, Levin S, Delcroix C, Mahler A, Verhas V. Blood cholesterol and hydrocortisone production in man: quantitative aspects of the utilization of circulating cholesterol by the adrenals at rest and under adrenocorticotropin stimulation. J Clin Invest . 1967;46:797–811. doi: 10.1172/JCI105580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bikle DD. Vitamin D metabolism, mechanism of action, and clinical applications. Chem Biol . 2014;21:319–329. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2013.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Marin JJ, Macias RI, Briz O, Banales JM, Monte MJ. Bile acids in physiology, pathology and pharmacology. Curr Drug Metab . 2015;17:4–29. doi: 10.2174/1389200216666151103115454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mutemberezi V, Guillemot-Legris O, Muccioli GG. Oxysterols: from cholesterol metabolites to key mediators. Prog Lipid Res . 2016;64:152–169. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2016.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Spann NJ, Glass CK. Sterols and oxysterols in immune cell function. Nat Immunol . 2013;14:893–900. doi: 10.1038/ni.2681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Abrams ME, Johnson KA, Perelman SS, Zhang LS, Endapally S, Mar KB, et al. Oxysterols provide innate immunity to bacterial infection by mobilizing cell surface accessible cholesterol. Nat Microbiol . 2020;5:929–942. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0701-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Perucha E, Melchiotti R, Bibby JA, Wu W, Frederiksen KS, Roberts CA, et al. The cholesterol biosynthesis pathway regulates IL-10 expression in human Th1 cells. Nat Commun . 2019;10:498. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-08332-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Golucci APBS, Marson FAL, Ribeiro AF, Nogueira RJN. Lipid profile associated with the systemic inflammatory response syndrome and sepsis in critically ill patients. Nutrition . 2018;55-56:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2018.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Levels JH, Lemaire LC, van den Ende AE, van Deventer SJ, van Lanschot JJ. Lipid composition and lipopolysaccharide binding capacity of lipoproteins in plasma and lymph of patients with systemic inflammatory response syndrome and multiple organ failure. Crit Care Med . 2003;31:1647–1653. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000063260.07222.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. van Leeuwen HJ, Heezius EC, Dallinga GM, van Strijp JA, Verhoef J, van Kessel KP. Lipoprotein metabolism in patients with severe sepsis. Crit Care Med . 2003;31:1359–1366. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000059724.08290.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Levels JH, Pajkrt D, Schultz M, Hoek FJ, van Tol A, Meijers JC, et al. Alterations in lipoprotein homeostasis during human experimental endotoxemia and clinical sepsis. Biochim Biophys Acta . 2007;1771:1429–1438. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cirstea M, Walley KR, Russell JA, Brunham LR, Genga KR, Boyd JH. Decreased high-density lipoprotein cholesterol level is an early prognostic marker for organ dysfunction and death in patients with suspected sepsis. J Crit Care . 2017;38:289–294. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2016.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lekkou A, Mouzaki A, Siagris D, Ravani I, Gogos CA. Serum lipid profile, cytokine production, and clinical outcome in patients with severe sepsis. J Crit Care . 2014;29:723–727. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2014.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lee SH, Park MS, Park BH, Jung WJ, Lee IS, Kim SY, et al. Prognostic implications of serum lipid metabolism over time during sepsis. BioMed Res Int . 2015;2015:789298. doi: 10.1155/2015/789298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chien JY, Jerng JS, Yu CJ, Yang PC. Low serum level of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol is a poor prognostic factor for severe sepsis. Crit Care Med . 2005;33:1688–1693. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000171183.79525.6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Walley KR, Boyd JH, Kong HJ, Russell JA. Low low-density lipoprotein levels are associated with, but do not causally contribute to, increased mortality in sepsis. Crit Care Med . 2019;47:463–466. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Vavrova L, Rychlikova J, Mrackova M, Novakova O, Zak A, Novak F. Increased inflammatory markers with altered antioxidant status persist after clinical recovery from severe sepsis: a correlation with low HDL cholesterol and albumin. Clin Exp Med . 2016;16:557–569. doi: 10.1007/s10238-015-0390-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Trinder M, Genga KR, Kong HJ, Blauw LL, Lo C, Li X, et al. Cholesteryl ester transfer protein influences high-density lipoprotein levels and survival in sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2019;199:854–862. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201806-1157OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Spriggs DR, Sherman ML, Michie H, Arthur KA, Imamura K, Wilmore D, et al. Recombinant human tumor necrosis factor administered as a 24-hour intravenous infusion: a phase I and pharmacologic study. J Natl Cancer Inst . 1988;80:1039–1044. doi: 10.1093/jnci/80.13.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. van Gameren MM, Willemse PH, Mulder NH, Limburg PC, Groen HJ, Vellenga E, et al. Effects of recombinant human interleukin-6 in cancer patients: a phase I-II study. Blood . 1994;84:1434–1441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Memon RA, Grunfeld C, Moser AH, Feingold KR. Tumor necrosis factor mediates the effects of endotoxin on cholesterol and triglyceride metabolism in mice. Endocrinology . 1993;132:2246–2253. doi: 10.1210/endo.132.5.8477669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hill NE, Saeed S, Phadke R, Ellis MJ, Chambers D, Wilson DR, et al. Detailed characterization of a long-term rodent model of critical illness and recovery. Crit Care Med . 2015;43:e84–e96. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Morel J, Hargreaves I, Brealey D, Neergheen V, Backman JT, Lindig S, et al. Simvastatin pre-treatment improves survival and mitochondrial function in a 3-day fluid-resuscitated rat model of sepsis. Clin Sci (Lond) . 2017;131:747–758. doi: 10.1042/CS20160802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Moreira RS, Irigoyen M, Sanches TR, Volpini RA, Camara NO, Malheiros DM, et al. Apolipoprotein A-I mimetic peptide 4F attenuates kidney injury, heart injury, and endothelial dysfunction in sepsis. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol . 2014;307:R514–R524. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00445.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ettinger WH, Miller LD, Albers JJ, Smith TK, Parks JS. Lipopolysaccharide and tumor necrosis factor cause a fall in plasma concentration of lecithin: cholesterol acyltransferase in cynomolgus monkeys. J Lipid Res . 1990;31:1099–1107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. El-Deeb WM, Tharwat M. Lipoproteins profile, acute phase proteins, proinflammatory cytokines and oxidative stress biomarkers in sheep with pneumonic pasteurellosis. Comp Clin Pathol . 2015;24:581–588. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hardy JP, Streeter EM, DeCook RR. Retrospective evaluation of plasma cholesterol concentration in septic dogs and its association with morbidity and mortality: 51 cases (2005-2015) J Vet Emerg Crit Care (San Antonio) . 2018;28:149–156. doi: 10.1111/vec.12705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ali Abdelhamid Y, Cousins CE, Sim JA, Bellon MS, Nguyen NQ, Horowitz M, et al. Effect of critical illness on triglyceride absorption. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr . 2015;39:966–972. doi: 10.1177/0148607114540214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. de Vasconcelos PR, Kettlewell MG, Gibbons GF, Williamson DH. Increased rates of hepatic cholesterogenesis and fatty acid synthesis in septic rats in vivo: evidence for the possible involvement of insulin. Clin Sci (Lond) . 1989;76:205–211. doi: 10.1042/cs0760205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. de la Llera Moya M, McGillicuddy FC, Hinkle CC, Byrne M, Joshi MR, Nguyen V, et al. Inflammation modulates human HDL composition and function in vivo. Atherosclerosis . 2012;222:390–394. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2012.02.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tall AR, Yvan-Charvet L. Cholesterol, inflammation and innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol . 2015;15:104–116. doi: 10.1038/nri3793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Brousseau ME, Schaefer EJ, Wolfe ML, Bloedon LT, Digenio AG, Clark RW, et al. Effects of an inhibitor of cholesteryl ester transfer protein on HDL cholesterol. N Engl J Med . 2004;350:1505–1515. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Dusuel A, Deckert V, Pais de Barros JP, van Dongen K, Choubley H, Charron É, et al. Human cholesteryl ester transfer protein lacks lipopolysaccharide transfer activity, but worsens inflammation and sepsis outcomes in mice. J Lipid Res . doi: 10.1194/jlr.RA120000704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Grion CM, Cardoso LT, Perazolo TF, Garcia AS, Barbosa DS, Morimoto HK, et al. Lipoproteins and CETP levels as risk factors for severe sepsis in hospitalized patients. Eur J Clin Invest . 2010;40:330–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2010.02269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Trinder M, Wang Y, Madsen CM, Ponomarev T, Bohunek L, Daisely BA, et al. Inhibition of cholesteryl ester transfer protein preserves high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and improves survival in sepsis. Circulation . 2021;143:921–934. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.048568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Walley KR, Thain KR, Russell JA, Reilly MP, Meyer NJ, Ferguson JF, et al. PCSK9 is a critical regulator of the innate immune response and septic shock outcome. Sci Transl Med . 2014;6:258ra143. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Feng Q, Wei WQ, Chaugai S, Carranza Leon BG, Kawai V, Carranza Leon DA, et al. A genetic approach to the association between PCSK9 and sepsis. JAMA Netw Open . 2019;2:e1911130. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.11130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Vecchié A, Bonaventura A, Meessen J, Novelli D, Minetti S, Elia E, et al. ALBIOS Biomarkers Study Investigators PCSK9 is associated with mortality in patients with septic shock: data from the ALBIOS study. J Intern Med . 2021;289:179–192. doi: 10.1111/joim.13150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Diczfalusy U, Olofsson KE, Carlsson AM, Gong M, Golenbock DT, Rooyackers O, et al. Marked upregulation of cholesterol 25-hydroxylase expression by lipopolysaccharide. J Lipid Res . 2009;50:2258–2264. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M900107-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tietge UJ, Maugeais C, Cain W, Grass D, Glick JM, de Beer FC, et al. Overexpression of secretory phospholipase A2 causes rapid catabolism and altered tissue uptake of high density lipoprotein cholesteryl ester and apolipoprotein A-I. J Biol Chem . 2000;275:10077–10084. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.14.10077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kisilevsky R, Subrahmanyan L. Serum amyloid A changes high density lipoprotein’s cellular affinity: a clue to serum amyloid A’s principal function. Lab Invest . 1992;66:778–785. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bhogal HK, Sanyal AJ. The molecular pathogenesis of cholestasis in sepsis. Front Biosci (Elite Ed) . 2013;5:87–96. doi: 10.2741/e598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Recknagel P, Gonnert FA, Westermann M, Lambeck S, Lupp A, Rudiger A, et al. Liver dysfunction and phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase signalling in early sepsis: experimental studies in rodent models of peritonitis. PLoS Med . 2012;9:e1001338. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Solomkin JS, Robinson CT, Cave CM, Ehmer B, Lentsch AB. Alterations in membrane cholesterol cause mobilization of lipid rafts from specific granules and prime human neutrophils for enhanced adherence-dependent oxidant production. Shock . 2007;28:334–338. doi: 10.1097/shk.0b013e318047b893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. White MM, Geraghty P, Hayes E, Cox S, Leitch W, Alfawaz B, et al. Neutrophil membrane cholesterol content is a key factor in cystic fibrosis lung disease. EBioMedicine . 2017;23:173–184. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Dünser MW, Ruokonen E, Pettilä V, Ulmer H, Torgersen C, Schmittinger CA, et al. Association of arterial blood pressure and vasopressor load with septic shock mortality: a post hoc analysis of a multicenter trial. Crit Care . 2009;13:R181. doi: 10.1186/cc8167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Catapano AL, Pirillo A, Bonacina F, Norata GD. HDL in innate and adaptive immunity. Cardiovasc Res . 2014;103:372–383. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvu150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Fessler MB, Parks JS. Intracellular lipid flux and membrane microdomains as organizing principles in inflammatory cell signaling. J Immunol . 2011;187:1529–1535. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Hillyard DZ, Nutt CD, Thomson J, McDonald KJ, Wan RK, Cameron AJ, et al. Statins inhibit NK cell cytotoxicity by membrane raft depletion rather than inhibition of isoprenylation. Atherosclerosis . 2007;191:319–325. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Marik PE, Pastores SM, Annane D, Meduri GU, Sprung CL, Arlt W, et al. American College of Critical Care Medicine Recommendations for the diagnosis and management of corticosteroid insufficiency in critically ill adult patients: consensus statements from an international task force by the American College of Critical Care Medicine. Crit Care Med . 2008;36:1937–1949. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31817603ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Annane D. The role of ACTH and corticosteroids for sepsis and septic shock: an update. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) . 2016;7:70. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2016.00070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Kanczkowski W, Tymoszuk P, Chavakis T, Janitzky V, Weirich T, Zacharowski K, et al. Upregulation of TLR2 and TLR4 in the human adrenocortical cells differentially modulates adrenal steroidogenesis. Mol Cell Endocrinol . 2011;336:41–46. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2010.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Haeno S, Maeda N, Yamaguchi K, Sato M, Uto A, Yokota H. Adrenal steroidogenesis disruption caused by HDL/cholesterol suppression in diethylstilbestrol-treated adult male rat. Endocrine . 2016;52:148–156. doi: 10.1007/s12020-015-0732-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Festti J, Grion CM, Festti L, Mazzuco TL, Lima-Valassi HP, Brito VN, et al. Adrenocorticotropic hormone but not high-density lipoprotein cholesterol or salivary cortisol was a predictor of adrenal insufficiency in patients with septic shock. Shock . 2014;42:16–21. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Molenaar N, Bijkerk RM, Beishuizen A, Hempen CM, de Jong MF, Vermes I, et al. Steroidogenesis in the adrenal dysfunction of critical illness: impact of etomidate. Crit Care . 2012;16:R121. doi: 10.1186/cc11415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Etogo-Asse FE, Vincent RP, Hughes SA, Auzinger G, Le Roux CW, Wendon J, et al. High density lipoprotein in patients with liver failure; relation to sepsis, adrenal function and outcome of illness. Liver Int . 2012;32:128–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Arem R, Ghusn H, Ellerhorst J, Comstock JP. Effect of decreased plasma low-density lipoprotein levels on adrenal and testicular function in man. Clin Biochem . 1997;30:419–424. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9120(97)00040-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. de Haan K, Groeneveld AB, de Geus HR, Egal M, Struijs A. Vitamin D deficiency as a risk factor for infection, sepsis and mortality in the critically ill: systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care . 2014;18:660. doi: 10.1186/s13054-014-0660-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Christaki E, Opal SM, Keith JC, Jr, Kessinian N, Palardy JE, Parejo NA, et al. Estrogen receptor β agonism increases survival in experimentally induced sepsis and ameliorates the genomic sepsis signature: a pharmacogenomic study. J Infect Dis . 2010;201:1250–1257. doi: 10.1086/651276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Amrein K, Schnedl C, Holl A, Riedl R, Christopher KB, Pachler C, et al. Effect of high-dose vitamin D3 on hospital length of stay in critically ill patients with vitamin D deficiency: the VITdAL-ICU randomized clinical trial. JAMA . 2014;312:1520–1530. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.13204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Ginde AA, Brower RG, Caterino JM, Finck L, Banner-Goodspeed VM, Grissom CK, et al. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute PETAL Clinical Trials Network Early high-dose vitamin D3 for critically ill, vitamin D-deficient patients. N Engl J Med . 2019;381:2529–2540. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1911124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Christeff N, Benassayag C, Carli-Vielle C, Carli A, Nunez EA. Elevated oestrogen and reduced testosterone levels in the serum of male septic shock patients. J Steroid Biochem . 1988;29:435–440. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(88)90254-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Horvatits T, Drolz A, Rutter K, Roedl K, Langouche L, Van den Berghe G, et al. Circulating bile acids predict outcome in critically ill patients. Ann Intensive Care . 2017;7:48. doi: 10.1186/s13613-017-0272-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Kipp HA. Variation in the cholesterol content of the serum in pneumonia. J Biol Chem . 1920;44:215–237. [Google Scholar]

- 76. Press AT, Traeger A, Pietsch C, Mosig A, Wagner M, Clemens MG, et al. Cell type-specific delivery of short interfering RNAs by dye-functionalised theranostic nanoparticles. Nat Commun . 2014;5:5565. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Song Z, Bai J, Nauwynck H, Lin L, Liu X, Yu J, et al. 25-Hydroxycholesterol provides antiviral protection against highly pathogenic porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus in swine. Vet Microbiol . 2019;231:63–70. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2019.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. McDonald MC, Dhadly P, Cockerill GW, Cuzzocrea S, Mota-Filipe H, Hinds CJ, et al. Reconstituted high-density lipoprotein attenuates organ injury and adhesion molecule expression in a rodent model of endotoxic shock. Shock . 2003;20:551–557. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000097249.97298.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Zhang Z, Datta G, Zhang Y, Miller AP, Mochon P, Chen YF, et al. Apolipoprotein A-I mimetic peptide treatment inhibits inflammatory responses and improves survival in septic rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol . 2009;297:H866–H873. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01232.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Datta G, Gupta H, Zhang Z, Mayakonda P, Anantharamaiah GM, White CR. HDL mimetic peptide administration improves left ventricular filling and cardiac output in lipopolysaccharide-treated rats. J Clin Exp Cardiolog . 2011;2:1000172. doi: 10.4172/2155-9880.1000172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Kwon WY, Suh GJ, Kim KS, Kwak YH, Kim K. 4F, apolipoprotein AI mimetic peptide, attenuates acute lung injury and improves survival in endotoxemic rats. J Trauma Acute Care Surg . 2012;72:1576–1583. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182493ab4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Zhang X, Wang L, Chen B. Recombinant HDL (Milano) protects endotoxin-challenged rats from multiple organ injury and dysfunction. Biol Chem . 2015;396:53–60. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2014-0188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Tanaka S, Genève C, Zappella N, Yong-Sang J, Planesse C, Louedec L, et al. Reconstituted high-density lipoprotein therapy improves survival in mouse models of sepsis. Anesthesiology . 2020;132:825–838. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000003155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Berger JM, Loza Valdes A, Gromada J, Anderson N, Horton JD. Inhibition of PCSK9 does not improve lipopolysaccharide-induced mortality in mice. J Lipid Res . 2017;58:1661–1669. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M076844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Pajkrt D, Doran JE, Koster F, Lerch PG, Arnet B, van der Poll T, et al. Antiinflammatory effects of reconstituted high-density lipoprotein during human endotoxemia. J Exp Med . 1996;184:1601–1608. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.5.1601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Dellinger RP, Tomayko JF, Angus DC, Opal S, Cupo MA, McDermott S, et al. Lipid Infusion and Patient Outcomes in Sepsis (LIPOS) Investigators Efficacy and safety of a phospholipid emulsion (GR270773) in Gram-negative severe sepsis: results of a phase II multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-finding clinical trial. Crit Care Med . 2009;37:2929–2938. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181b0266c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Guirgis FW, Black LP, Rosenthal MD, Henson M, Ferreira J, Leeuwenburgh C, et al. Lipid Intensive Drug therapy for Sepsis Pilot (LIPIDS-P): phase I/II clinical trial protocol of lipid emulsion therapy for stabilising cholesterol levels in sepsis and septic shock. BMJ Open . 2019;9:e029348. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Oesterle A, Laufs U, Liao JK. Pleiotropic effects of statins on the cardiovascular system. Circ Res . 2017;120:229–243. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.308537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Zeiser R. Immune modulatory effects of statins. Immunology . 2018;154:69–75. doi: 10.1111/imm.12902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Durant R, Klouche K, Delbosc S, Morena M, Amigues L, Beraud JJ, et al. Superoxide anion overproduction in sepsis: effects of vitamin e and simvastatin. Shock . 2004;22:34–39. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000129197.46212.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Camerino GM, Tarantino N, Canfora I, De Bellis M, Musumeci O, Pierno S. Statin-induced myopathy: translational studies from preclinical to clinical evidence. Int J Mol Sci . 2021;22:2070. doi: 10.3390/ijms22042070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. DuBroff R, de Lorgeril M. Cholesterol confusion and statin controversy. World J Cardiol . 2015;7:404–409. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v7.i7.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Hackam DG, Mamdani M, Li P, Redelmeier DA. Statins and sepsis in patients with cardiovascular disease: a population-based cohort analysis. Lancet . 2006;367:413–418. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68041-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Kruger P, Fitzsimmons K, Cook D, Jones M, Nimmo G. Statin therapy is associated with fewer deaths in patients with bacteraemia. Intensive Care Med . 2006;32:75–79. doi: 10.1007/s00134-005-2859-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Liappis AP, Kan VL, Rochester CG, Simon GL. The effect of statins on mortality in patients with bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis . 2001;33:1352–1357. doi: 10.1086/323334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Kruger P, Bailey M, Bellomo R, Cooper DJ, Harward M, Higgins A, et al. ANZ-STATInS Investigators–ANZICS Clinical Trials Group A multicenter randomized trial of atorvastatin therapy in intensive care patients with severe sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2013;187:743–750. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201209-1718OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Truwit JD, Bernard GR, Steingrub J, Matthay MA, Liu KD, Albertson TE, et al. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute ARDS Clinical Trials Network Rosuvastatin for sepsis-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med . 2014;370:2191–2200. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1401520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. McAuley DF, Laffey JG, O’Kane CM, Perkins GD, Mullan B, Trinder TJ, et al. HARP-2 Investigators Irish Critical Care Trials Group. Simvastatin in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med . 2014;371:1695–1703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1403285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Calfee CS, Delucchi KL, Sinha P, Matthay MA, Hackett J, Shankar-Hari M, et al. Irish Critical Care Trials Group Acute respiratory distress syndrome subphenotypes and differential response to simvastatin: secondary analysis of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med . 2018;6:691–698. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30177-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]