Abstract

Rationale

South African adolescents carry a high tuberculosis disease burden. It is not known if schools are high-risk settings for Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB) transmission.

Objectives

To detect airborne MTB genomic DNA in classrooms.

Methods

We studied 72 classrooms occupied by 2,262 students in two South African schools. High-volume air filtration was performed for median 40 (interquartile range [IQR], 35–54) minutes and assayed by droplet digital PCR (ddPCR)-targeting MTB region of difference 9 (RD9), with concurrent CO2 concentration measurement. Classroom data were benchmarked against public health clinics. Students who consented to individual tuberculosis screening completed a questionnaire and sputum collection (Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra) if symptom positive. Poisson statistics were used for MTB RD9 copy quantification.

Measurements and Main Results

ddPCR assays were positive in 13/72 (18.1%) classrooms and 4/39 (10.3%) clinic measurements (P = 0.276). Median ambient CO2 concentration was 886 (IQR, 747–1223) ppm in classrooms versus 490 (IQR, 405–587) ppm in clinics (P < 0.001). Average airborne concentration of MTB RD9 was 3.61 copies per 180,000 liters in classrooms versus 1.74 copies per 180,000 liters in clinics (P = 0.280). Across all classrooms, the average risk of an occupant inhaling one MTB RD9 copy was estimated as 0.71% during one standard lesson of 35 minutes. Among 1,836/2,262 (81.2%) students who consented to screening, 21/90 (23.3%) symptomatic students produced a sputum sample, of which one was Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra positive.

Conclusions

Airborne MTB genomic DNA was detected frequently in high school classrooms. Instantaneous risk of classroom exposure was similar to the risk in public health clinics.

Keywords: air sampling, adolescent, school, ddPCR, tuberculosis

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

South African adolescents carry a high burden of tuberculosis, but it is not known if schools are high-risk settings for transmission.

What This Study Adds to the Field

Mycobacterium tuberculosis genomic DNA was detected frequently in air sampled from high school classrooms. Instantaneous risk of classroom exposure to M. tuberculosis genomic DNA was similar to, or even greater than, that of health clinics. Cumulative exposure to undiagnosed subclinical and active tuberculosis among adolescents may contribute to school-based transmission. Implementation of school-based infection control measures, including measures to limit pandemic respiratory viral infections, may help reduce tuberculosis risk among adolescents in high-incidence settings.

Approximately 47% of tuberculosis (TB) cases in South Africa are either undiagnosed or not successfully treated (1). Adolescents in Cape Town had an annualized force of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection of 14% in 2015 (2). School-based tuberculosis (TB) surveillance measures may be useful in detection of previously undiagnosed TB cases for early therapeutic intervention to reduce TB transmission.

Air sampling for M. tuberculosis genomic DNA assayed by quantitative PCR has been hampered by limited assay sensitivity on filtrate samples (3), likely owing to the small copy number in ambient air (3), and the presence of inhibitors of PCR amplification (4–7). Droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) offers superior sensitivity to traditional quantitative PCR methods if genomic DNA quantities are low (8).

South African studies show that a significant proportion of adolescents acquire M. tuberculosis infection outside of the household (9–12). ddPCR testing of air filtrate samples for M. tuberculosis DNA may inform our understanding of TB transmission risk in other congregate settings (9). Sampling for airborne M. tuberculosis DNA should ideally be performed in tandem with measures of ventilation, as suboptimal ventilation in the school setting could expose adolescents to increased risk of infection in the event of undiagnosed TB cases. Ambient indoor CO2 concentration is frequently used as a proxy for indoor ventilation (13).

We conducted air sampling of M. tuberculosis genomic DNA, in tandem with measurement of ambient CO2 concentration and voluntary TB symptom screening, to quantify risk of exposure to airborne M. tuberculosis genomic DNA in school classrooms. Some results have been reported previously in abstract form at the American Thoracic Society 2020 conference, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (14).

Methods

Study Design

Between September 1, 2017, and September 30, 2018, we conducted a cross-sectional study of air sampling for M. tuberculosis DNA, in conjunction with measurement of ambient CO2 concentration, in 72 classrooms occupied by 2,262 students from two high schools. Voluntary TB screening and symptom-triggered investigation were offered to consenting students. To benchmark classroom data against a setting with putative risk of M. tuberculosis exposure, multiple air samples and measurements of ambient CO2 concentration were performed in three outpatient TB clinics.

Study Setting

The study was conducted in Worcester, South Africa, a region with approximately 33,370 adolescents (15), where the adolescent TB disease case notification rate was 361 cases per 100,000 in 2015 (16). The two high schools (school A, 32 classrooms, and school B, 40 classrooms) were selected based on high risk for M. tuberculosis infection, with IFN-γ release assay (IGRA) positivity rates of 60% and 51%, respectively, in 2015 (17).

Ethical Approval

The study protocol was approved by the University of Cape Town Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC REF 163/2016). The HREC waived the need for individual assent/consent for ambient air sampling by all classroom occupants owing to minimal risk. Students provided written informed assent/consent for individual TB symptom screening, for which the HREC waived the need for parental consent owing to minimal risk and potential health benefit.

Study Procedures

Air sampling for M. tuberculosis DNA and measurement of ambient CO2 concentration was performed in all classrooms and in three clinics. Voluntary TB symptom screening was offered to student occupants of classrooms.

Each classroom was sampled only once for a median 40 minutes, starting before the first lesson of the day, between April and May 2018 (autumn) for school A and August and September 2018 (winter–spring) for school B. Each clinic was sampled on multiple occasions for a median 82 minutes, during the morning on different days, between November 2017 and February 2018 (spring–summer). Additional sampling was performed in an open-air space to provide a negative control for M. tuberculosis DNA ddPCR and a benchmark for outdoor CO2 concentration.

ddPCR Assay

Sampling for airborne M. tuberculosis DNA was conducted using a portable Dry Filter Unit (DFU) device (American Felt and Filter Co., Lockheed Martin) (18) through a removable polyester felt filter with 47-mm diameter and 1.0-μm pore size (Sterlitech Corporation). The DFU, which samples approximately 1,000 L of air per minute, was placed on the floor at the back of the classroom or clinic (19).

The ddPCR assay was performed using a previously published protocol (20). The ddPCR assay targets the region of difference 9 (RD9) region of the M. tuberculosis genome to distinguish M. tuberculosis from other members of the M. tuberculosis complex (3). Briefly, filters from the DFU were processed by vortexing in 10-ml sterile phosphate-buffered saline + 0.5% Tween80 and centrifuged at 4,500 rpm for 15 minutes. The pellet obtained from centrifugation was lysed for DNA extraction and purification. We used the 2× Supermix for Probes (Bio-Rad Laboratories) (21). Positive control samples were M. tuberculosis H37Rv genomic DNA, whereas negative template control samples comprised only the mastermix (20). Thermal cycler parameters used for DNA amplification were as follows: 50°C for 2 minutes (incubation for Amperase); 95°C for 10 minutes; 94°C for 30 seconds; 60°C for 1 minute, and repeat 94°C for 30 seconds (40 cycles); 98°C for 10 minutes; holding at 4°C for between 5 and 24 hours before plate reading using fluorescent reporter dyes (FAM dye or VIC dye [Applera Corporation]) using channel 1 (QX100 Bio-Rad Droplet Reader; BioRad Laboratories) (21). PCR confirmation targeted RD91R (5′–gatggcgttcggaaagaaac–3′) and RD91F (5′–tgagtggcgatggtcaacac–3′). The probe was the Taqman MGB probe labeled with FAM fluorescent reporter dye (5′–famactacgcggcttagtg–3′). Poisson distribution statistics was used for M. tuberculosis RD9 copy quantification in QuantaSoft software (22).

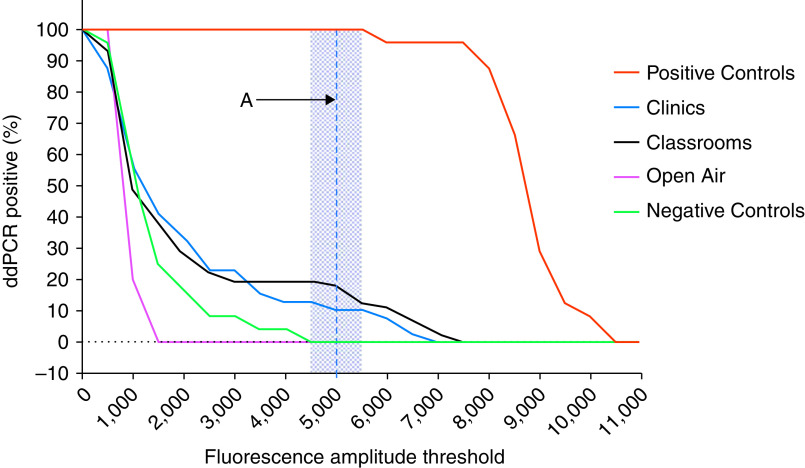

The range of fluorescence amplitude intensity that provided optimal (100%) ddPCR assay discrimination between negative control samples and positive control samples was 4,500–5,500 (Figure 1). The midpoint of this optimal range for fluorescence amplitude intensity (5,000) was selected as the positive threshold for all subsequent analyses. The proportion of positive M. tuberculosis ddPCR assays using this threshold was 24/24 (100%) for positive control samples; 0/24 (0%) for negative template control samples; and 0/5 (0%) for DFU samples collected from open-air spaces.

Figure 1.

Percentage of positive Mycobacterium tuberculosis droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) assays by fluorescence amplitude intensity threshold. The shaded region is the fluorescence amplitude intensity cutoff that provided 100% discrimination between negative control samples and positive control samples (i.e., 4,500–5,500). Dashed Line A represents the optimal fluorescence amplitude intensity cutoff (5,000) selected for all subsequent M. tuberculosis droplet digital PCR analyses.

Ambient CO2 Concentration

Ambient CO2 concentrations were recorded at 1-minute intervals, using a portable CO2 detector (Ethernet Multilogger thermo-hygro-CO2 meter) (23). CO2 detectors were placed 50 cm from the floor at the back of the classroom or clinic. We previously demonstrated that CO2 concentrations are not sensitive to height of CO2 detector in a room (24). The number of occupants in each room was recorded at the start of testing. Median CO2 concentration was used to define ventilation in rooms as “high” or “low” risk (high risk if median CO2 ⩾ 1,000 ppm and low risk if <1,000 ppm) (13, 25, 26). Rebreathed fraction of air, defined as the fraction of inhaled air previously exhaled by another person in the same space, was calculated using the Rudnick and Milton equation (27). The online supplement describes the calculation of rebreathed fraction of air (27), volume of rebreathed air (24), and ventilation rate (28).

Risk of Inhalation of M. tuberculosis DNA

The concentration of M. tuberculosis RD9 was standardized to 180,000 L of air (180 m3), based on the average volume of classrooms, calculated as:

Copy number of M. tuberculosis RD9 per 180,000 L of air = (Equation 1):

| (1) |

The rate of inhalation of M. tuberculosis RD9 copies per sampling episode (i.e., “r”) was estimated by (Equation 2):

| (2) |

Note: 8 L/min is the respiratory minute volume (29, 30).

The risk of an individual occupant inhaling at least one M. tuberculosis RD9 copy was estimated by (Equation 3):

| (3) |

Note: exp = exponent; r = the rate of inhalation of M. tuberculosis RD9 copies per sampling episode obtained from Equation 2 above.

The risk of an individual occupant inhaling at least one M. tuberculosis RD9 copy during a 35-minute lesson was obtained by (Equation 4):

| (4) |

The estimated average risk of inhaling M. tuberculosis RD9 in classrooms or clinics was obtained by summing classroom or clinic risk of inhaling one RD9 copy, divided by the number of classrooms or clinics.

Symptom Screening

Voluntary TB symptom screening was offered to consenting classroom occupants during classroom CO2 measurement and air sampling. These students completed a self-administered TB symptom questionnaire, which included cough for at least 2 weeks; haemoptysis; weight loss for at least 2 months; fever of unknown cause for at least 2 weeks; or night sweats for at least 2 weeks. Students who reported any of these symptoms, and who were willing to provide a spontaneously expectorated sputum sample, were requested to provide one early morning sputum for Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra (Cepheid) testing and were referred to the outpatient clinic for further management.

Statistical Analysis

Poisson distribution statistics was used for M. tuberculosis RD9 copy quantification, and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to compare CO2 concentrations between clinics or schools. The chi-square test was used to assess statistically significant differences between number of ddPCR-positive and high-risk ventilation spaces across clinics or schools.

Results

Air sampling yielded a positive M. tuberculosis RD9 ddPCR assay in 13/72 (18.1%) classrooms, including 5/40 (12.5%) in school A and 8/32 (25.0%) in school B (P = 0.171), and 4/39 (10.3%) clinic rooms (P = 0.276).

The estimated average concentration of M. tuberculosis RD9 was 3.61 copies (range, 0–82) per 180,000 L for all classrooms versus 1.74 copies per 180,000 L (range, 0–27) for all clinic rooms (P = 0.280).

Ventilation Parameters

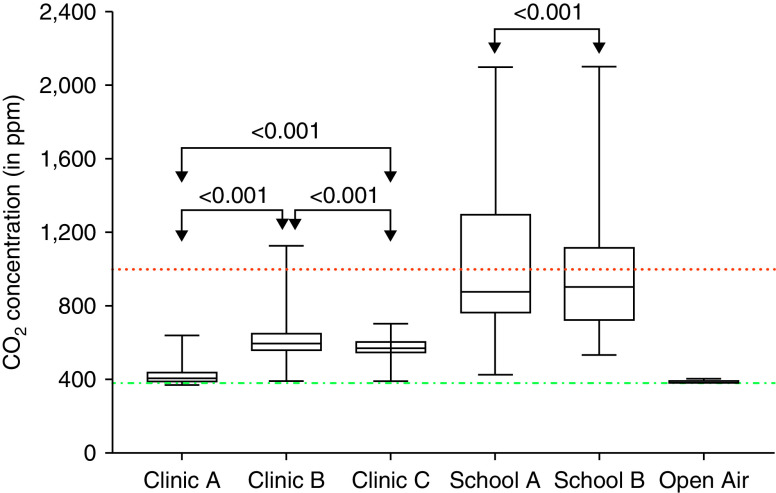

The median ambient CO2 concentration was 886 (IQR, 747–1223) ppm in classrooms versus 490 (IQR, 405–587) ppm in clinic rooms (P < 0.001) (Figure 2). Overall, 25/63 (40%) classrooms, but 0 clinic rooms, were classified as high-risk spaces with median CO2 concentration at least 1,000 ppm (Table 1). A total of 39/63 (62%) classrooms had peak CO2 of at least 1,000 ppm, indicating transient periods of high-risk ventilation.

Figure 2.

Comparison of ambient CO2 concentration in clinics measured in ppm. The figure shows that CO2 concentration varied by type of space. The dotted and dashed green line is the median measured CO2 concentration of open-air environmental space of 387 ppm (67 CO2 readings; interquartile range [IQR], 384–403 ppm). The dotted red line is the threshold (ceiling) for recommended median CO2 concentration in indoor spaces of 1,000 ppm. The median classroom CO2 concentration for school A was 877 ppm (5,852 CO2 readings from 40 rooms; IQR, 761–1297 ppm) and for school B was 904 ppm (4,186 CO2 readings from 32 rooms; IQR, 719–1114 ppm). The median clinic CO2 concentration for clinic A was 405 ppm (1,320 CO2 readings from 3 rooms; IQR, 387–440 ppm), for clinic B was 595 ppm (857 CO2 readings from 2 rooms; IQR, 555–651 ppm), and for clinic C was 571 ppm (521 CO2 readings from 2 rooms; IQR, 544–605 ppm).

Table 1.

Classification of Ventilation Risk Status in Classrooms and Clinic Rooms

| Setting | Total Duration of Sampling, h | Duration with Ambient CO2 ⩾ 1,000 ppm, h (% of Total Duration) | Proportion of Rooms with Median CO2 ⩾ 1,000 ppm, n/N (%) | Proportion of Rooms with Peak CO2 ⩾ 1,000 ppm, n/N (%) | Proportion of Rebreathed Air, Median (IQR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| School A | 24.4 | 9.5 (38.9%) | 14/31 (45.2%) | 19/31 (61.3%) | 1.26% (1.15–2.42) |

| School B | 17.4 | 6.2 (35.6%) | 11/32 (34.4%) | 20/32 (62.5%) | 1.40% (1.02–1.81) |

| All schools | 41.8 | 15.7 (37.6%) | 25/63 (39.7%) | 39/63 (61.9%) | 1.30% (1.06–2.28) |

| Clinic A | 22.0 | 0 (0%) | 0/9 (0%) | 0/9 (0%) | 0.03% (0.02–0.10) |

| Clinic B | 14.3 | 0.15 (1.0%) | 0/7 (0%) | 3/7 (42.9%) | 0.58% (0.47–0.63) |

| Clinic C | 8.7 | 0 (0%) | 0/5 (0%) | 0/5 (0%) | 0.43% (0.33–0.52) |

| All clinics | 45 | 0.15 (0.3%) | 0/21 (0%) | 3/21 (14.3%) | 0.33% (0.04–0.52) |

| Open air | 1.1 | 0 (0%) | 0/3 (0%) | 0/3 (0%) | NA |

Definition of abbreviations: IQR = interquartile range; NA = not applicable.

Median classroom ventilation rate was 6.3 (IQR, 3.9–8.3) air changes per hour, and median proportion of rebreathed air was 1.30% for all classrooms. The median volume of rebreathed air per student per 35-minute lesson was 3.40 (IQR, 2.25–5.12) L.

A steady-state CO2 concentration was rarely observed in classrooms despite peak concentrations reaching more than 1,000 ppm (Figure E1 in the online supplement). Classrooms in schools A and B had median CO2 concentrations of 904 (IQR, 719–1114) ppm and 877 (IQR, 761–1297) ppm, respectively (Figure 2). The distribution and dynamics of ambient CO2 concentrations in individual classrooms were variable. Representative examples are shown in online supplement (Figure E1).

The distribution of ambient CO2 concentrations was also variable in clinics, but all clinics had median CO2 concentrations below 1,000 ppm. Representative examples are shown in the online supplement (Figure E2). Clinics A, B, and C had median ambient CO2 concentrations of 405 (IQR, 387–440) ppm, 595 (IQR, 555–651) ppm, and 571 (IQR, 544–605) ppm, respectively (see Figure E2).

The median CO2 concentration in M. tuberculosis RD9 ddPCR-positive and -negative classrooms was 829 (IQR, 700–1114) and 914 (IQR, 761–1243), respectively. The median CO2 concentration in M. tuberculosis RD9 ddPCR-positive and -negative clinics was 582 (IQR, 475–645) and 469 (IQR, 402–577), respectively. There was no statistically significant association between classroom M. tuberculosis RD9 ddPCR result and CO2 concentration (P = 0.284).

Across all classrooms, the average risk of an occupant inhaling one M. tuberculosis RD9 copy was estimated as 0.71% during one standard lesson of 35 minutes.

Symptom Screening for TB

A total of 1,836 out of 2,262 students (81.2%) in the classrooms selected for air sampling were enrolled. Among those with self-reported racial ancestry data, school A included 1,073 (96.6%) African, 36 (3.2%) mixed racial ancestry, and 1 (0.1%) Indian participants; school B included 10 (1.6%) African, 608 (96.1%) mixed racial ancestry, 1 (0.2%) Indian, and 14 (2.2%) White participants. Median age was 16.2 (IQR, 15.1–17.5) years, and 779 (45.8%) participants were male. Median age of study participants in school A was 16.6 (IQR, 15.2–17.8; range 11.8–23.6) years, and in school B, 15.7 (IQR, 14.8–16.8; range 13.3–21.1) years.

A total of 215 of the 1,836 (11.7%) students reported one or more TB-related symptoms: 90 reported cough for at least 2 weeks (4.9%); 14 reported haemoptysis (0.8%); 79 reported weight loss for more than 2 months (4.3%); 68 reported fever of unknown cause for more than 2 weeks (3.7%); and 48 reported night sweats for more than 2 weeks (2.6%). A total of 58/90 (64.4%) students reporting cough for at least 2 weeks agreed to provide a sputum sample, but only 21/58 (36.2%) submitted sputum for Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra testing, 1 (4.8%) of which was positive, giving an estimated TB disease prevalence of 55 (confidence interval [CI], 0–341) per 100,000 among students screened for symptoms. There was no statistically significant association between classroom M. tuberculosis RD9 ddPCR result and presence of a student with any TB-related symptoms (P = 0.864), or presence of a student with microbiologically-confirmed TB disease (P = 0.105).

The single classroom with a microbiologically-confirmed case of TB disease identified through symptom screening was occupied by 41 students (median age, 18.4 [IQR, 17.8–19.6] years), 29 (71%) of whom consented to symptom screening. Three male students in the classroom reported at least one TB symptom, including the single student with microbiologically confirmed TB disease, who reported cough for at least 2 weeks. One other student reported cough for at least 2 weeks, and one student reported weight loss and fever, but both were unable to produce sputum for testing.

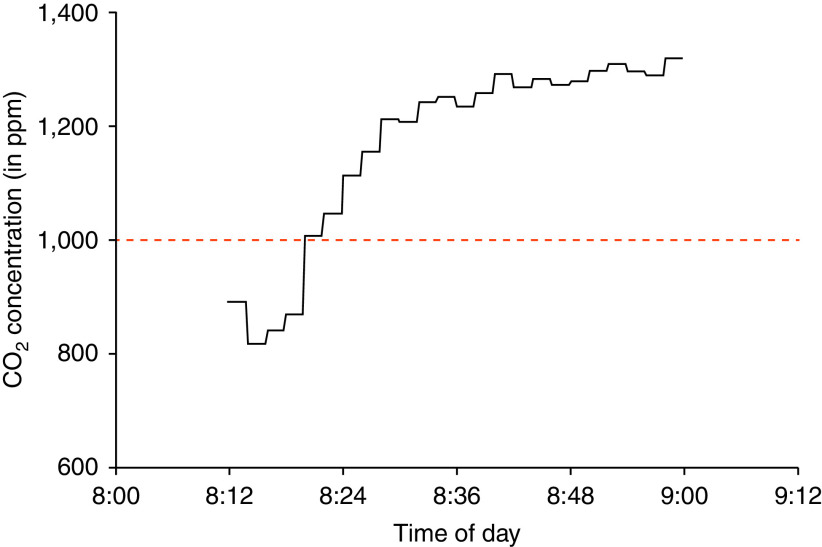

Students in this classroom spent 40 of the 58-minute sampling period (83%) with indoor ambient CO2 concentrations above 1,000 ppm. Median CO2 concentration was 1,242 ppm (IQR: 1,046–1,283 ppm; Figure 3). Air sampling of this classroom yielded a positive M. tuberculosis RD9 ddPCR assay.

Figure 3.

Indoor ambient CO2 concentration monitoring of a classroom with a confirmed tuberculosis disease case, measured in ppm. Students spent 40 minutes exposed to indoor ambient CO2 concentrations above the recommended median CO2 concentration of 1,000 ppm (dashed red line).

Discussion

We have demonstrated that airborne M. tuberculosis genomic DNA was detected frequently in high school classrooms in this high-TB-burden area of South Africa (16, 17). Classroom ventilation, measured in air changes per hour, was approximately half the WHO-recommended 12 air changes per hour (13). Instantaneous risk of classroom exposure to one M. tuberculosis RD9 copy was similar to that observed in outpatient clinics managing patients with TB. The diagnostic yield of voluntary symptom screening among students was low, consistent with the presence of undiagnosed subclinical and active tuberculosis cases, which may contribute to increased risk of transmission among adolescents in the school setting. This possibility is supported by a recent South African national TB prevalence survey that reported 58% of TB cases among individuals aged at least 15 years did not report any TB symptoms yet had bacteriological confirmation of TB (31).

We studied health clinics as comparator spaces with high a priori risk of exposure to patients with TB. All clinic rooms studied were adequately ventilated, possibly owing to sampling during spring and summer months, whereas underventilated classrooms were studied during the autumn–winter–spring months. It is notable that a positive M. tuberculosis RD9 ddPCR assay was obtained in 18% of classrooms and 10% of clinic rooms. Although we acknowledge the potential impact of seasonal factors, we infer that risk of exposure to airborne M. tuberculosis DNA in underventilated classrooms is similar to that in better-ventilated health facilities treating patients with known TB.

Indoor environment and ventilation are key determinants of transmission for airborne infections (32, 33). Our finding that 40% of classrooms were inadequately ventilated is similar to that of another South African study (60%) (13). Inadequate classroom ventilation is not limited to schools in developing countries. A study of 62 classrooms in Greece found 52% to be inadequately ventilated (34). A systematic review of ambient CO2 concentration in European schools also found 52% of classrooms inadequately ventilated (34). However, the potential risk of school-based M. tuberculosis transmission would be greater in high-burden than low-burden settings, given similar suboptimal ventilation conditions. Inadequate ventilation of classrooms is likely associated with few open windows (27%) during the cooler months. However, the mean rebreathed air volume (5.0 L) for one classroom session in this study is lower than the 6.7 L of fresh atmospheric air reported for an equivalent period in another study of South African adolescents (24).

A South African study previously reported an average concentration of 40 M. tuberculosis colony-forming units on culture per GeneXpert sputum-positive patient with TB from 1-hour confinement in a custom-built respiratory aerosol-sampling chamber (20). In this study, the average risk of a classroom occupant inhaling one M. tuberculosis RD9 copy per standard lesson of 35 minutes was 0.7%. The RD9 genomic locus distinguishes M. tuberculosis from other members of the M. tuberculosis complex and is present as a single copy. This permits use of this assay for the specific identification of M. tuberculosis bacilli. Therefore, as one RD9 copy indicates a single M. tuberculosis bacillus, the number of inhaled bacilli was deemed equal to the RD9 copy number. Students in South African high schools spend approximately 1,155 hours congregated in classrooms each calendar year (35). We estimate that each student would have inhaled on average 11 M. tuberculosis bacilli per year if conditions remained constant.

These findings suggest that air sampling for M. tuberculosis DNA is a useful tool for TB transmission research in endemic countries, including schools and other congregate settings. Prospective serial measurement of IGRA in a fixed, continuously monitored population of susceptible individuals would be required to establish the relationship between M. tuberculosis RD9 ddPCR data and rates of M. tuberculosis infection.

To complement classroom air sampling data, we set out to identify undiagnosed TB cases in those classrooms with a positive M. tuberculosis RD9 ddPCR signal. Owing to mixing of students before and after each sampling session, and potential transmission outside of the school setting, it is not possible to link classroom-level M. tuberculosis ddPCR results directly to the single TB case observed in this study. Our study was designed to mimic school-based symptom screening programs in resource-limited countries, which would be unlikely to incorporate IGRA, chest radiography, or sputum induction for all students owing to feasibility and cost considerations. It is acknowledged that voluntary, self-reported symptom screening and spontaneous sputum sample production is likely to underestimate the true rate of TB in school surveys. However, the CI of the TB prevalence estimate in this study overlaps that of a 2005–2007 study (prevalence, 300 per 100,000; CI, 100–400 per 100,000 population) in the same community (36) and that of two other South African studies (476 cases per 100,000; CI, 0–1,305 [37] [2002], and 274 cases per 100,000; CI, 263–284 [38] [2013]). It is also possible that students with subclinical TB, who would not have been detected by symptom screening, contributed to aerosolization of M. tuberculosis DNA detected in this study.

Additional limitations of this study include factors that might impact indoor air quality, including light intensity, wind direction and speed (39), desiccation rate (40), size of windows, relative humidity, and temperature (34), which were not measured systematically. We also acknowledge that in the absence of repeated sampling, the lack of longitudinal data from individual classrooms precludes estimation of variance in risk of exposure to M. tuberculosis DNA over time. We concede that respiratory minute ventilation of high school students is dependent upon individual height, weight, and physical activity, and therefore estimates are uncertain. Other important parameters that impact M. tuberculosis infectivity that cannot be deduced from ddPCR include natural decay of microbes, aerosolization-induced damage, biologic variability, and host immunologic defenses, among others. Our estimates of M. tuberculosis RD9 concentration assume 100% recovery of M. tuberculosis DNA from intact bacilli with no losses during filtration and processing. As this is almost certainly not the case, it implies that our estimates of M. tuberculosis DNA concentration and risk of TB exposure likely represent lower bounds. An important potential limitation for the use of DNA-based technologies for TB disease surveillance is that the PCR assay is based on amplification of the target DNA sequence. As PCR does not distinguish between living or dead organisms, and thus between infectious and noninfectious quanta (41), not all detectable DNA indicates viable microbes able to establish an infection. Thus, it is acknowledged that the risk of inhaling an M. tuberculosis DNA copy cannot be extrapolated directly to the risk of sustained M. tuberculosis infection with potential for progression to TB disease.

Others have postulated that quantitative airborne sampling of M. tuberculosis DNA might be a clinically relevant measure of infectivity to target high-risk spaces for intensified surveillance (20). Periodic classroom air sampling to identify M. tuberculosis RD9 ddPCR-positive classrooms, followed by intensive TB symptom screening and Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra testing and chest radiography of classroom occupants, might be feasible and cost-effective even in resource-limited settings like South Africa. Studies using a longitudinal design that includes air sampling, coupled with intensive TB case detection supported by sputum induction and liquid culture, would help determine the potential role of air sampling for targeted tuberculosis screening in classrooms and other congregate settings (20). Further research into approaches that use air sampling in conjunction with ddPCR testing and genotyping is needed to evaluate the potential of this tool to increase the efficiency of mass tuberculosis screening among adolescents and to reduce the risk of TB transmission in schools. Implementation of school-based infection control measures, including measures to limit pandemic respiratory viral infections such as the coronavirus disease (COVID-19), may help reduce tuberculosis risk among adolescents in high-incidence settings.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the study team from the South African Tuberculosis Vaccine Initiative (SATVI), including Gloria Khomba, Cynthia Gwintsa, Xoliswa Kelepu, Nambitha Nqakala, and Marwou de Kock; the study participants; and the Western Cape Provincial Departments of Health and Education.

Footnotes

Supported by the South African Agency for Science and Technology Advancement (Innovation Doctoral Scholarship, National Research Foundation [NRF] grant UID: 95084). Opinions expressed, and conclusions arrived at, are those of the authors and are not necessarily attributed to the NRF. This research is not done on behalf of or commissioned by the NRF. The NRF funding is not specific to this work. Also supported by National Institutes of Health (U.S.A.) (NIH Clinical Center grant number DP2 AI131082 to J.R.A. via Stanford University). The authors also acknowledge the support of the Strategic Health Innovations Partnerships initiative of the South African Medical Research Council (to D.F.W.) and the Carnegie Corporation of New York (via sub-award from the University of Cape Town to A.K.).

Author Contributions: Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work: E.W.B., D.F.W., R.W., J.R.A., and M.H.; acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: E.W.B., K.M., A.K., Z.H., H.M., A.K.K.L., J.S., S.C.M., M.T., T.J.S., D.F.W., R.W., J.R.A., and M.H.; writing the first draft: E.W.B. and M.H.; revision of the work for important intellectual content and final approval of the version to be published: E.W.B., K.M., A.K., Z.H., H.M., A.K.K.L., J.S., S.C.M., M.T., T.J.S., D.F.W., R.W., J.R.A., and M.H.; agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work and ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved: E.W.B., K.M., A.K., Z.H., H.M., A.K.K.L., J.S., S.C.M., M.T., T.J.S., D.F.W., R.W., J.R.A., and M.H.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.202102-0405OC on November 9, 2021

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1. Naidoo P, Theron G, Rangaka MX, Chihota VN, Vaughan L, Brey ZO, et al. The South African tuberculosis care cascade: estimated losses and methodological challenges. J Infect Dis . 2017;216:S702–S713. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Andrews JR, Hatherill M, Mahomed H, Hanekom WA, Campo M, Hawn TR, et al. The dynamics of QuantiFERON-TB gold in-tube conversion and reversion in a cohort of South African adolescents. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2015;191:584–591. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201409-1704OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schafer MP. Detection and characterization of airborne Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Ra particles, a surrogate for airborne pathogenic M. tuberculosis. Aerosol Sci Technol . 1999;30:161–173. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mastorides SM, Oehler RL, Greene JN, Sinnott JT, IV, Kranik M, Sandin RL. The detection of airborne Mycobacterium tuberculosis using micropore membrane air sampling and polymerase chain reaction. Chest . 1999;115:19–25. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chen P, Li C. Quantification of airborne Mycobacterium tuberculosis in health care setting using real-time qPCR coupled to an air-sampling filter method. Aerosol Sci Technol . 2005;39:371–376. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wan GH, Lu SC, Tsai YH. Polymerase chain reaction used for the detection of airborne Mycobacterium tuberculosis in health care settings. Am J Infect Control . 2004;32:17–22. doi: 10.1016/s0196-6553(03)00090-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Matuka O, Singh TS, Bryce E, Yassi A, Kgasha O, Zungu M, et al. Pilot study to detect airborne Mycobacterium tuberculosis exposure in a South African public healthcare facility outpatient clinic. J Hosp Infect . 2015;89:192–196. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2014.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.RainDance Digital PCR reagents and consumables. 2015. http://raindancetech.com/digital-pcr-tech/

- 9. Middelkoop K, Bekker LG, Morrow C, Lee N, Wood R. Decreasing household contribution to TB transmission with age: a retrospective geographic analysis of young people in a South African township. BMC Infect Dis . 2014;14:221. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-14-221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mossong J, Hens N, Jit M, Beutels P, Auranen K, Mikolajczyk R, et al. Social contacts and mixing patterns relevant to the spread of infectious diseases. PLoS Med . 2008;5:e74. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wood R, Racow K, Bekker LG, Morrow C, Middelkoop K, Mark D, et al. Indoor social networks in a South African township: potential contribution of location to tuberculosis transmission. PLoS One . 2012;7:e39246. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Middelkoop K, Mathema B, Myer L, Shashkina E, Whitelaw A, Kaplan G, et al. Transmission of tuberculosis in a South African community with a high prevalence of HIV infection. J Infect Dis . 2015;211:53–61. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Richardson ET, Morrow CD, Kalil DB, Ginsberg S, Bekker LG, Wood R. Shared air: a renewed focus on ventilation for the prevention of tuberculosis transmission. PLoS One . 2014;9:e96334. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bunyasi E, Middelkoop K, Koch A, et al. Indoor air quality and tuberculosis risk in two South African Schools [abstract] Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2020;201:A6381. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Provincial profile. 2014. http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/Report-03-01-70/Report-03-01-702011.pdf

- 16. Bunyasi EW, Mulenga H, Luabeya AKK, Shenje J, Mendelsohn SC, Nemes E, et al. Regional changes in tuberculosis disease burden among adolescents in South Africa (2005-2015) PLoS One . 2020;15:e0235206. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0235206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bunyasi EW, Geldenhuys H, Mulenga H, Shenje J, Luabeya AKK, Tameris M, et al. Temporal trends in the prevalence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in South African adolescents. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis . 2019;23:571–578. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.18.0283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fatah A, Arcilesi R, Chekol T, Lattin CH, Sadik OA, Aluoch A.2007https://tsapps.nist.gov/publication/get_pdf.cfm?pub_id=32499.

- 19.Naval Surface Warfare Center Dahlgren Division 2015. [accessed 9 Dec 2015]. Available from: https://www.powershow.com/view/3c9412-YTg2Y/Naval_Surface_Warfare_Center_Dahlgren_Division_Dry_Filter_powerpoint_ppt_presentation?varnishcache=1

- 20. Patterson B, Morrow C, Singh V, et al. Detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacilli in bio-aerosols from untreated TB patients. Gates Open Research . 2017 doi: 10.12688/gatesopenres.12758.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc. 2019. www.bio-rad.com

- 22.Bio-Rad 2019. [accessed 2021 Feb 1]. Available from: https://www.bio-rad.com/webroot/web/pdf/lsr/literature/Bulletin_6407.pdf.

- 23.Ethernet Multilogger-thermo-hygro-CO2 meter with 2 MiniDin and 2 terminals. 2015. https://www.cometsystem.com/products/ethernet-multilogger-thermo-hygro-co2-meter-with-2-minidin-and-2-terminals/reg-m1322

- 24. Wood R, Morrow C, Ginsberg S, Piccoli E, Kalil D, Sassi A, et al. Quantification of shared air: a social and environmental determinant of airborne disease transmission. PLoS One . 2014;9:e106622. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.WHO policy on TB infection control in health-care facilities, congregate settings and households World Health Organization 2009https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44148/9789241598323_eng.pdf;sequence=1. [PubMed]

- 26.Bhatia A.2019. https://www.cedengineering.com/courses/hvac-design-for-healthcare-facilities

- 27. Rudnick SN, Milton DK. Risk of indoor airborne infection transmission estimated from carbon dioxide concentration. Indoor Air . 2003;13:237–245. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0668.2003.00189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Persily AK.1997. https://www.aivc.org/sites/default/files/airbase_10530.pdf

- 29. Douglas NJ, White DP, Pickett CK, Weil JV, Zwillich CW. Respiration during sleep in normal man. Thorax . 1982;37:840–844. doi: 10.1136/thx.37.11.840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Krieger J, Maglasiu N, Sforza E, Kurtz D. Breathing during sleep in normal middle-aged subjects. Sleep . 1990;13:143–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moyo S, Walt M.2021. https://www.knowledgehub.org.za/elibrary/first-national-tb-prevalence-survey-south-africa-2018

- 32. Riley RL, Wells WF, Mills CC, Nyka W, Mclean RL. Air hygiene in tuberculosis: quantitative studies of infectivity and control in a pilot ward. Am Rev Tuberc . 1957;75:420–431. doi: 10.1164/artpd.1957.75.3.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wells WF. Airborne contagion and air hygiene. an ecological study of droplet infections. JAMA . 1955;159:90. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Santamouris M, Synnefa A, Asssimakopoulos M, et al. Experimental investigation of the air flow and indoor carbon dioxide concentration in classrooms with intermittent natural ventilation. Energy Build . 2008;40:1833–1843. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Department of Basic Education. 2019. https://www.gov.za/about-sa/school-calendar

- 36. Mahomed H, Ehrlich R, Hawkridge T, Hatherill M, Geiter L, Kafaar F, et al. Screening for TB in high school adolescents in a high burden setting in South Africa. Tuberculosis (Edinb) . 2013;93:357–362. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2013.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Marais BJ, Obihara CC, Gie RP, Schaaf HS, Hesseling AC, Lombard C, et al. The prevalence of symptoms associated with pulmonary tuberculosis in randomly selected children from a high burden community. Arch Dis Child . 2005;90:1166–1170. doi: 10.1136/adc.2004.060640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Snow K, Hesseling AC, Naidoo P, Graham SM, Denholm J, du Preez K. Tuberculosis in adolescents and young adults: epidemiology and treatment outcomes in the Western Cape. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis . 2017;21:651–657. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.16.0866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lighthart B, Shaffer B. Bacterial flux from chaparral into the atmosphere in mid-summer at a high desert location. Atmos Environ . 1994;28:1267–1274. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cole EC, Cook CE. Characterization of infectious aerosols in health care facilities: an aid to effective engineering controls and preventive strategies. Am J Infect Control . 1998;26:453–464. doi: 10.1016/S0196-6553(98)70046-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. West JS, Atkins SD, Emberlin J, Fitt BD. PCR to predict risk of airborne disease. Trends Microbiol . 2008;16:380–387. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]