Abstract

During the COVID-19 pandemic, media accounts emerged describing faith-based organizations (FBOs) working alongside health departments to support the COVID-19 response. In May 2021, the Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (ASTHO) sent an electronic survey to the 59 ASTHO member jurisdictions and four major US cities to assess state and territorial engagement with FBOs. Findings suggest that public health officials in many jurisdictions were able to work effectively with FBOs during the COVID-19 pandemic to provide essential education and mitigation tools to diverse communities. (Am J Public Health. 2022;112(3):397–400. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2021.306620)

Vaccination is an important tool to help stop the COVID-19 pandemic. During the COVID-19 response, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Center for Faith-Based and Neighborhood Partnerships, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (ASTHO) encouraged health departments’ engagement with faith-based organizations (FBOs) to help groups disproportionately affected.1 We sought to assess the ability of health departments to work with FBOs to reach those in greatest need.

INTERVENTION

ASTHO developed a 13-question, mixed methods electronic survey with CDC and HHS to assess state and territorial engagement with FBOs to promote COVID-19 vaccination, other response efforts, and non‒COVID-19 health collaboration.

PLACE AND TIME

From May 13 to 19, 2021, with support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, ASTHO sent the survey to all 59 ASTHO jurisdictions and four major US cities.

PERSONS

Directors of public health preparedness were encouraged to enlist agency colleagues, such as immunization managers and minority or health equity directors, to complete the questionnaire.

PURPOSE

We sought to determine (1) the frequency of state and territorial health department partnerships with FBOs to promote COVID-19 vaccination and other response efforts and (2) factors supporting and hindering such partnerships.

IMPLEMENTATION

Twenty-six of 63 jurisdictions surveyed responded, for a response rate of 41%. We used descriptive epidemiology to assess frequencies of responses and identified common themes and meaningful patterns in the data by repeated examination and sorting of answers and comments (i.e., a data-driven qualitative process).

EVALUATION

During the COVID-19 pandemic, 24 of 26 respondents (92%) reported that their department or agency engaged with FBOs to promote COVID-19 vaccination. Of the two that reported that FBOs had not been engaged, one shared that engaging FBOs was addressed at the local level. The other shared that lack of established relationships with FBOs, staff and resource limitations, and FBO distrust of government prevented FBO involvement.

Promotion of Health Equity

Of the 24 respondents whose health department or agency worked with FBOs, 100% viewed these partnerships as valuable for reaching racial and ethnic minority groups. In free text, a respondent explained that working with FBOs “was particularly valuable in outreach with racial and ethnic minority groups.” Another described the “development of an equity plan, [establishment of] an equity task force to advance outreach, and [provision] of mobile vaccination specifically for partners, such as FBOs and NGOs, to take vaccines to the neighborhoods.”

Inclusion of Diverse Religious Communities

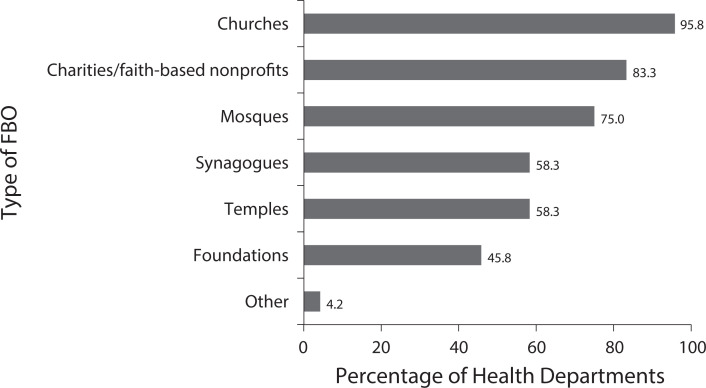

Many respondents attempted to be inclusive in their faith-based outreach: 23 (96%) described working with churches, 18 (75%) with mosques, 14 (58%) with synagogues, and 14 (58%) with temples (Figure 1). In free text, respondents wrote of “reaching out to mosques prior to Ramadan,” and “vaccine clinics at three mosques, which helped with vaccine rates in immigrant [groups].”

FIGURE 1—

Diverse Religious Partners Involved in 24 State and Territorial Health Department COVID-19 Vaccination Efforts: United States, May 2021

Serving as COVID-19 Vaccination Sites

Twenty-one of 24 jurisdictions said FBOs served as vaccination sites. Success stories included, “we [implemented a state-based vaccine initiative], which [puts] vaccination clinics at places of worship, [with the goal of] vaccinating 25,000 more people in these communities.”

Health communication was key to COVID-19 vaccine promotion. Twenty-three respondents said that FBOs served as trusted messengers, and 22 said FBOs disseminated communication materials. Communication challenges included “reliable and secure Internet connections—faith organizations [are] not always connected digitally.”

Funding to Support Other COVID-19 Response

FBOs contributed to a variety of funded vaccination and other nonvaccination activities (Box 1). Fifteen respondents said FBOs supported vaccine registration and helped people in the community overcome other logistical issues related to getting a COVID-19 vaccine, and 11 provided transportation to vaccination sites.

Box 1.

Vaccination and Other Non‒Vaccination-Related COVID-19 Response Activities Conducted by Faith-Based Organizations (FBOs) Receiving Funding From State and Territorial Health Departments: United States, 2021

| 1. Community outreach and engagement: FBOs provided community coordinators and community health and outreach workers, supporting community education. |

| 2. Personal hygiene: COVID-19 minigrants were used to support personal protective equipment, hand sanitizer, and cleaning supply distribution, and COVID-19 safety kits for food pantries or other distribution efforts. |

| 3. COVID-19 testing: FBOs provided assistance to community members to access testing; health departments funded the development of COVID-19 testing materials for houses of worship, testing clinics, laboratory supplies, and analysis of test results. |

| 4. Quarantine and isolation: FBOs provided assistance to community members accessing safe quarantine or isolation facilities. |

| 5. Vaccine promotion: Health departments funded the development of COVID-19 vaccination materials for houses of worship and vaccination clinics. |

| 6. Training: Health departments funded trainings for FBOs on responding to a pandemic respiratory emergency. |

| 7. Health communications: FBOs amplified public health emergency messaging for houses of worship and assisted with translation of materials and public service announcements. |

Cultivation of Relationships

Findings suggest that both the health departments and FBOs were interested in collaboration. Most commonly, the department or agency reached out to FBOs for assistance with COVID-19 vaccination promotion efforts (21 of 24 respondents), but 16 respondents stated that FBOs had reached out to their health department. In free text, a respondent described how they had “built out a Community Engagement Branch in our incident command structure to integrate community and faith-based organizations into the COVID-19 response.”

When asked about challenges in working with FBOs, four health departments described a need for stronger relationships with FBOs and greater knowledge about how they operate. Another described difficulty connecting “to smaller houses of worship that do not participate in coalitions or larger judicatory bodies.” Two participants commented on communication challenges—for example, “We do all coordination with vaccine providers and community partnerships through e-mail. These FBOs prefer phone calls. That takes a lot of time.”

The role of FBOs continued to evolve over the COVID-19 response. One respondent noted:

Towards the beginning of the response, [we] had more FBOs interested in hosting a vaccination site than we had doses available. With vaccine available at many locations, there’s less of a need for host sites, so working with FBOs now is more likely to focus on addressing vaccine hesitancy and providing credible information.

Partnership Benefits for Future Activities

Partnerships were seen by some respondents as potentially beneficial for future efforts. Respondents commented: “[We are] partnering with a leader in the faith sector to help houses of worship and faith-based organizations prepare for emergencies,” and “increased relationships should be a platform for future collaboration.”

ADVERSE EFFECTS

Five respondents described vaccine hesitancy and government distrust within groups that have been marginalized. Participants noted, “the J&J pause had a [negative] effect on those communities, [as well as the] lack of vaccines early on [in the pandemic].” Others commented, “[There is] mixed support for vaccinations [in a] large number of churches in [our state],” and “some [houses of worship]/FBOs do not trust government or see that they have a role in emergency response.”

While our findings suggest that belief systems can promote healthy behaviors, previous studies showed that some FBOs can be sources of misinformation, experience tensions over public health restrictions or guidance related to worship services, and, unfortunately, facilitate the transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2).2‒5

SUSTAINABILITY

Challenges included limited time and personnel to devote to maintaining relationships with FBOs. Understanding the value that FBOs add to preparedness and response efforts may help to justify the commitment and resources required to sustain such partnerships.

PUBLIC HEALTH SIGNIFICANCE

Our findings suggest that many jurisdictions were able to work effectively with FBOs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, countless other congregations supported COVID-19 vaccination and other public health efforts without formal relationships with their health departments.6,7

Our findings are subject to several limitations. Our survey was based on a small sample of respondents. However, respondents did represent eight of the 10 HHS regions. We do not know how the states or territories that did not complete the survey would have answered these questions. It is likely that respondents were those working with FBOs rather than those considering working with FBOs or facing challenges. Thus, findings should be interpreted as positive leaning. Our survey was limited to the domestic response in the United States. Future assessments might include public health partnerships with FBOs to respond to COVID-19 in international settings.8

During the COVID-19 pandemic, which has resulted in hundreds of thousands of deaths in the United States, one promising finding has been the ability of health departments to work with FBOs to reach those in greatest need. Health officials may consider ways to work with FBOs in future preparedness and response efforts.9

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Support for this publication was provided in part by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

The COVID-19 Faith-Based Organization Writing Group provided critical feedback and helped shape the writing. The Writing Group consists of Melissa Lewis, James S. Blumenstock, Ericka McGowan, Meredith Allen, Mary A. Cooney, James Harris, Craig Wilkins, and John Donovan. The authors also thank Neetu Abad, Kimberly Bonner, Elisabeth Wilhelm, Danielle Gilliard, Stephanie Griswold, Rachel Locke, LaVonne Ortega, Elizabeth Allen, Amanda Raziano, Todd Parker, Gaylyn Henderson, Leandris Liburd, Maggie Carlin, Emily Peterman, and Ben O’Dell for their helpful input and support, and the many dedicated public health staff and volunteers and staff representing faith-based organizations across the United States.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors do not have any potential or actual conflicts of interest to disclose.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

Consistent with applicable federal law and CDC policy, this activity was reviewed by CDC and was determined not to be research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/1005702021.

- 2.Johnson KA,, Baraldi AN, Moon JW, Okun MA, Cohen AB. Faith and science mindsets as predictors of COVID-19 concern: a three-wave longitudinal study. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2021;96:104186. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2021.104186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kasstan B. “If a rabbi did say ‘you have to vaccinate,’ we wouldn’t”: unveiling the secular logics of religious exemption and opposition to vaccination. Soc Sci Med. 2021;280:114052. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.James A, Eagle L, Phillips C, et al. High COVID-19 attack rate among attendees at events at a church—Arkansas, March 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(20):632–635. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6920e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ali H, Kondapally K, Pordell P, et al. COVID-19 outbreak in an Amish community—Ohio, May 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(45):1671–1674. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6945a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levin J. The faith community and the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak: part of the problem or part of the solution? J Relig Health. 2020;59(5):2215–2228. doi: 10.1007/s10943-020-01048-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Monson K, Oluyinka M, Negro D, et al. Congregational COVID-19 conversations: utilization of medical‒religious partnerships during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. J Relig Health. 2021;60(4):2353–2361. doi: 10.1007/s10943-021-01290-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barmania S, Reiss MJ. Health promotion perspectives on the COVID-19 pandemic: the importance of religion. Glob Health Promot. 2021;28(1):15–22. doi: 10.1177/1757975920972992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bruce MA. COVID-19 and African American religious institutions. Ethn Dis. 2020;30(3):425–428. doi: 10.18865/ed.30.3.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]