Abstract

Objectives

To compare the clinical effectiveness of Hawley retainers (HRs) and modified vacuum-formed retainers (mVFRs) with palatal coverage in maintaining transverse expansion during a 12-month retention period.

Materials and Methods

Data were collected from postorthodontic treatment patients who met the inclusion criteria. A total of 35 patients were randomly allocated using a centralized randomization technique into either mVFR (n = 18) or HR group (n = 17). The outcome assessor and data analyst were blinded to the retention method. Dental casts of patients were evaluated at debond, 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months of retention. Intercanine width (ICW), interpremolar width (IPMW), interfirst molar mesiobuccal cusp width 1 (IFMW1), and interfirst molar distobuccal cusp width 2 (IFMW2) were compared between groups over time using mixed analysis of variance.

Results

No statistically significant differences were found between the two groups for ICW (P = .76), IPMW (P = .63), IFMW1 (P = .16), and IFMW2 (P = .40) during the 12-month retention period.

Conclusions

The null hypothesis could not be rejected. HR and mVFR had similar clinical effectiveness in the retention of transverse expansion cases during a 12-month retention period.

Keywords: Orthodontic retainers, Dentoalveolar expansion, Recurrence, Treatment outcome, Controlled clinical trial

INTRODUCTION

Expansion of the arches is considered very unstable and prone to 40% relapse regardless of the type of expansion, mostly as a result of the posttreatment growth pattern of the patient.1,2 For retention, Hawley retainers (HRs) were indicated to have greater stability than vacuum-formed retainers (VFRs) for transverse expansion because of their rigidity.3 Although there were many advantages of VFRs over HRs for being more esthetic,4 cheaper,5 and easier to fabricate,6 no studies compared the effectiveness of these retainers for transverse expansion cases. Standard VFRs in a U-shape configuration are made up of vacuum-formed polyurethane material that, in theory, would be less durable compared with methyl methacrylate in HRs. Therefore, VFRs may have inadequate transarch stability for maintaining upper arch expansion.3,7

Modified vacuum-formed retainers (mVFRs) have been described to be effective in maintaining palatal expansion,8 similar to other retention methods.9,10 However, the majority of the studies compared mVFRs to a fixed bonded retainer but did not compare mVFRs with HRs.10 The cases selected were Class I with normal anteroposterior and transverse skeletal dimensions. The mVFRs prescribed require an extra wire outlining the cementoenamel junction of the teeth palatally,8 which demands extra expertise, cost, and time. Hence, a simpler version of mVFRs was proposed in the present trial, where the only difference compared with the conventional VFR was extended palatal coverage that, in theory, would be more durable to maintain transverse expansion compared with the conventional U-shaped VFR, as the palatal coverage would prevent flexion.

Specific Objectives and Hypotheses

The main aim of the current randomized clinical trial was to compare the clinical effectiveness of mVFRs and HRs in expansion cases by measuring maxillary arch width changes during a 12-month retention period. The null hypothesis tested in this trial was that there would be no significant difference in the effectiveness of mVFRs and HRs to maintain transarch stability.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Trial Design

This trial was a two-arm parallel prospective multicenter randomized controlled trial with a 1:1 allocation ratio conducted in the Orthodontic Specialist Unit of Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM), Klinik Pergigian Bandar Botanik Klang, and Klinik Pergigian Sungai Chua Kajang. The orthodontists had more than 5 years of experience. The study was approved by UKM Research and Ethics Committee (UKMPPI/111/8/JEP-2018-724) and the National Medical Research and Ethics Committee (NMRR-18-3639-44877) and was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04237298). There were no changes to the methods after trial commencement.

Participants, Eligibility Criteria, and Settings

Recruitment was carried out from August 2019 to July 2020. All orthodontic patients were screened on debond day. An information sheet and explanation regarding the trial were given by the researcher. Subsequently, informed consent was obtained.

Eligibility criteria included patients aged 13 years or older at the time of debond who had existing pretreatment dental casts and had undergone more than 3 mm of maxillary dentoalveolar expansion. Initially, the amount of arch width expansion was measured intraorally at debond and compared with the respective pretreatment dental casts. To ensure accuracy, the measurements were repeated on debond and pretreatment dental casts. The following linear arch width measurements were made: intercanine width (ICW; the distance between the canine cusp tips), interpremolar width (IPMW; the distance between the premolar cusp tips), interfirst molar width 1 (IFMW1; the distance between the mesiobuccal cusps), and interfirst molar width 2 (IFMW2; the distance between the distobuccal cusps). At least two or more points were expanded more than 3 mm to be included in the trial.

Patients were randomly allocated into two groups: either an upper removable HR or mVFR covering the palate. The type of lower retainer was decided by the orthodontists.

Interventions and Outcomes

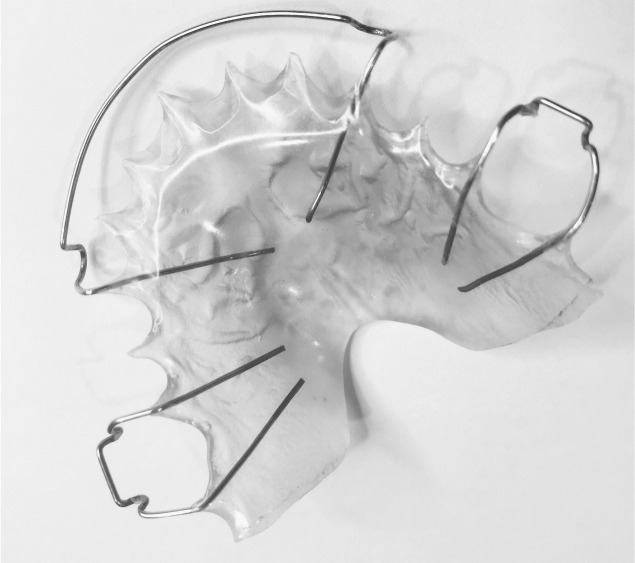

The materials used for the impressions and dental casts were alginate (Major Prodotti Dentari S.p.A., Moncalieri, Italy) and yellow stone (Samwoo Co Ltd, Ulsan, Korea), respectively. The fabrication of mVFRs (Figure 1) was accomplished using the 0.040-inch (1 mm) Essix plastic sheet (Dentsply Raintree Essix, Sarasota, Fla). HRs (Figure 2) were fabricated using acrylic resin (Scheu-Dental, Iserlohn, Germany) and a 0.70-mm stainless steel chromium coil wire (Scheu-Dental, Iserlohn, Germany).

Figure 1.

The HR used in the trial.

Figure 2.

The mVFR with palatal coverage used in the trial.

The technicians were trained to standardize retainer design. Retainers were fitted within 24 hours of debond. Patients were instructed to wear the retainers full time for the first 6 months, followed by nighttime wear for the next 6 months. For the first 6 months, they were asked to remove their retainers only when cleaning, drinking, or eating. Verbal instructions about the possible consequences of not complying with retainers were explained upon fitting. Text reminders were sent once a month.

Impressions were taken for dental cast construction on four occasions and later were measured at debond when retainers were fitted (T0) and at 3 months (T1), 6 months (T2), and 12 months (T3) of retention.

Data collection was performed by an independent researcher (L. Xian) with a Tuten electronic digital caliper (CSM Engineering Hardware (Malaysian) Sendirian Berhad, Malaysia) to a precision of .01mm. Linear measurements were made on each dental cast as specified. The average of three measurements was used for every point of measurement.

Method Errors

Intrarater reliability (L. Xian) was determined on 20 randomly selected dental casts 1 month after initial measurements. Interrater reliability (L. Xian, Dr Ashari) was determined on another 20 randomly selected dental casts. There was excellent intrarater reliability (1.00) and interrater reliability (0.98) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Reliability of Arch Width Measurements

| ICC |

n |

Coefficient |

95% Confidence Interval |

P Value |

|

| Lower Bound |

Upper Bound |

||||

| Intrarater reliability | 20 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | <.001a |

| Interrater reliability | 20 | 0.98 | 0.53 | 1.00 | <.001a |

Statistically significant.

Sample Size Calculation

Sample size was calculated based on a significance level of .05 and 80% power to detect a clinically meaningful difference for contact point displacement with a standard deviation (SD) of 2.0 mm.10 The power analysis gave a total of 16 participants for each arm. The sample size accounted for attrition by 10% for any loss to follow-up or noncompliance. Because there were two groups, a total of 35 participants were needed.

Interim Analysis and Stopping Guidelines

There were no interim analysis or stopping guidelines.

Randomization (Sequence Generation, Allocation Concealment, Implementation)

The generation of a randomization sequence was performed in blocks of 18 to ensure that an equal number of participants were allocated to each group. A centralized randomization technique that incorporated external involvement was employed. The computer-generated randomization sequence was performed by an independent researcher (Dr Kuppusamy) who also acted as a trial coordinator. To prevent selection bias and protect the assignment sequence until allocation, coresearchers at-site recruited eligible patients and contacted the center by phone after patients agreed to participate.

Blinding

To achieve blinding, each dental cast with an identity document was measured by a calibrated researcher (L. Xian) who was blinded to the retention regime provided to each patient. Patient identity numbers on dental casts were covered with opaque tape by the technicians and were randomized once they were ready for measurement. Only one dental cast at a time was selected for measuring without showing any previous measurements or retainer being assigned. Blinding of clinicians, assistants, and patients was not feasible in this trial.

Statistical Methods

Descriptive and inferential statistics were calculated using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS version 24.0; International Business Machines Corp, Armonk, N.Y.). Intracorrelation coefficient (ICC) was used to assess intrarater and interrater reliability. Normal distribution of data was confirmed by the Shapiro-Wilk test (P > .05). Hence, parametric statistics were used. The mean arch width change differences between retention groups during the follow-up period were evaluated using mixed analysis of variance (ANOVA). The significance level was set at .05. Intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis was performed for missing outcomes by calculating the mean difference between two consecutive time points. The mean difference was added to the data obtained at the time points before the points of missing data or to estimate the missing outcome.

RESULTS

Participant Flow

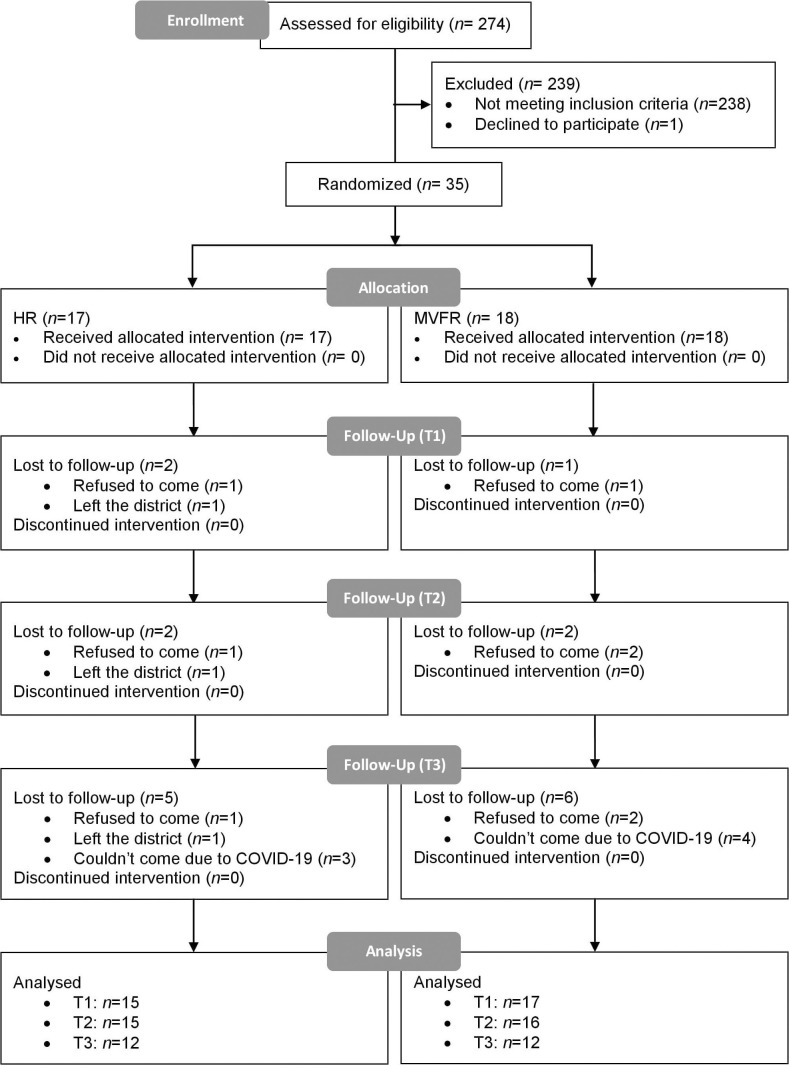

A total of 274 patients with planned maxillary expansion were screened for eligibility, of whom 239 were excluded from the study for the following reasons: 225 had less than 3 mm of expansion, 10 had missing pretreatment dental casts, 3 for whom the clinicians decided not to randomize the retainers, and one patient declined to participate in the study. Thus, 35 patients were randomly assigned for the trial. There were additional dropouts at different time points of analysis (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Consolidated Standards for Reporting of Trials participant flow diagram.

Baseline Data

The groups were well matched in terms of age and sex and showed no significant differences between groups (P > .05; Table 2).

Table 2.

Age and Sex Distribution of Patients in the Groupsa

| Variable |

HR Group, n = 17 |

mVFR Group, n = 18 |

Total, n = 35 |

P Value |

| Age at debond, y | 21.88 ± 4.12 | 22.06 ± 5.88 | 21.97 ± 5.03 | .92 |

| Sex | .56 | |||

| Male | 5 (29) | 7 (39) | 12 (34) | |

| Female | 12 (71) | 11 (61) | 23 (66) |

Data are provided as mean ± SD or n (%).

Numbers Analyzed, Outcomes, and Estimation

Table 3 shows the mean and SDs of arch width changes in the HR and mVFR groups at four time points. There were no statistically significant differences (P > .05) for width values between the two groups during the retention period. Generally, all mean values for the arch widths in both groups tended to decrease during the trial period. Although IFMW1 and IFMW2 values for the HR group showed an increase between T0 and T1, they showed a decrease afterward. The largest decreased mean between baseline (T0) and final (T4) analysis was observed for IPMW in the mVFR group (47.10 mm to 46.40 mm).

Table 3.

Mixed ANOVA Interaction Effect

| Variable |

Time Interval |

HR Group (mm), Mean ± SD |

95% Confidence Interval |

mVFR Group (mm), Mean ± SD |

95% Confidence Interval |

Mixed ANOVA P Value (Interaction Effect) |

| ICW | .76 | |||||

| T0 | 37.20 ± 2.46 | 36.09–38.30 | 38.04 ± 2.00 | 36.97–39.12 | ||

| T1 | 37.18 ± 2.55 | 36.05–38.31 | 37.93 ± 2.02 | 36.83–39.03 | ||

| T2 | 37.06 ± 2.53 | 35.96–38.17 | 37.80 ± 1.92 | 36.73–38.87 | ||

| T3 | 36.80 ± 2.78 | 35.61–37.99 | 37.69 ± 20.1 | 36.45–38.77 | ||

| IPMW | .63 | |||||

| T0 | 45.39 ± 1.88 | 44.33–46.45 | 47.10 ± 1.84 | 46.04–48.17 | ||

| T1 | 45.37 ± 1.88 | 44.29–46.46 | 46.87 ± 1.92 | 45.79–47.96 | ||

| T2 | 45.26 ± 1.94 | 44.10–46.41 | 46.77 ± 2.08 | 45.62–47.92 | ||

| T3 | 44.80 ± 1.92 | 43.62–45.97 | 46.40 ± 2.17 | 45.22–47.57 | ||

| IFMW1 | .16 | |||||

| T0 | 51.16 ± 1.73 | 50.12–52.21 | 53.35 ± 2.29 | 52.37–54.33 | ||

| T1 | 51.31 ± 1.66 | 50.26–52.36 | 53.15 ± 2.35 | 52.16–54.14 | ||

| T2 | 51.16 ± 1.79 | 50.07–52.26 | 53.01 ± 2.43 | 51.97–54.04 | ||

| T3 | 50.88 ± 1.82 | 49.78–51.98 | 52.93 ± 2.42 | 51.89–53.97 | ||

| IFMW2 | .40 | |||||

| T0 | 52.34 ± 2.09 | 51.14–53.54 | 54.26 ± 2.56 | 53.13–55.39 | ||

| T1 | 52.49 ± 2.17 | 51.23–53.75 | 54.20 ± 2.71 | 53.01–55.39 | ||

| T2 | 52.27 ± 2.15 | 51.00–53.54 | 54.11 ± 2.75 | 52.91–55.30 | ||

| T3 | 52.09 ± 2.29 | 50.78–53.40 | 54.04 ± 2.80 | 52.80–55.27 |

The reasons for retainer failure were loss (6%, HR only) and breakage (6%, HR; 22%, mVFR). Patients were given new retainers with the same design as soon as possible.

Harms

No harms were reported.

DISCUSSION

Findings and Interpretation

The present trial was designed to investigate the clinical effectiveness of HR and mVFR in maintaining maxillary arch expansion for up to 12 months of retention. The ICW, IPMW, and IFMW were selected as the outcome measures to evaluate transarch stability and thus indicate the clinical effectiveness of the retention methods in preventing relapse. Similar points of measurement have been used in many previous studies on retainer stability.11–14

The mean age in both groups was considered similar: HR, 21.88 years; mVFR, 22 years. There were more female patients than male patients in the trial, which is a normal occurrence in orthodontic studies.12,15–18 This could be attributed to the fact that the uptake of orthodontic treatment is greater among the female population.19–21

The greatest increase in arch width following dentoalveolar expansion was approximately 6.0 mm for ICW, IPMW, or IFMW. In the present trial, any changes in the arch widths from debond to the follow-up stage were considered as relapse. Apart from returning to the original malocclusion, relapse could also be considered as any unfavorable changes of tooth position after treatment away from the corrected malocclusion regardless of a positive or negative direction.22 When the changes of the mean ICW, IPMW, and IFMW were examined, they reduced during the trial period regardless of retention regime (Table 3). The reduction could have been attributed to relapse following expansion during orthodontic treatment.23,24 This could also have been the result of age-related changes.25–27 The changes were not significantly different between groups or among time points.

The main outcomes of the present trial showed that there were no statistically significant differences between HR and mVFR in any mean arch width changes during a 12-month retention period. This finding was consistent with past studies that compared the stability between HR and the normal version of VFR without palatal coverage in nonexpansion cases.12–14,28,29 The results indicated that HR and mVFR had similar clinical effectiveness in maintaining maxillary transverse expansion during a short-term period. With the extended palatal coverage and considerable hardness of the rugged thermoplastic material,30 this mVFR possibly possessed suitable physical properties to stabilize tooth position in an expanded arch, comparable with HRs that have previously been thought to be more rigid and better for transarch stability.3,23

There were more cases of retainer breakage reported in the mFVR group than in the HR group. The breakage might have been related to the resiliency and semi-elastic properties of the thermoplastic material in mVFR, making it more vulnerable to functional and parafunctional activities. This finding was consistent with the study by Saleh et al.31 but contradicted the study by Hichens et al.,30 which found that HRs were more likely to break.

Limitations

The main limitation of this trial was the relatively high dropout rate that increased throughout the trial (Figure 3). Studies have shown that participant dropout in a follow-up trial is highly anticipated.10,32 Consequently, more than 10% of the required sample size was recruited33 to account for dropouts. The dropout at T3 increased as a result of the emergence of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic outbreak in January 2020.34,35 Initially, a movement control order by the government resulted in closed borders and only emergency dental treatment was allowed. Therefore, some participants who were studying overseas could not come for the follow-up appointments. Once orthodontic treatment was allowed, a few refused to come as a result of COVID-19 concerns. Therefore, an ITT analysis was performed to minimize any risk of bias that may have been introduced by comparing groups that differed in prognostic variables.

The strength of this trial might have been affected by patient compliance in following instructions for use of the retainers. Monthly reminders were sent to each patient to remind him or her to wear the retainers as instructed. It was shown that text message reminder systems were effective for improving compliance with removable retainers and follow-up attendance.36 During each visit, retainers were also examined to ensure they fit well.

Recommendations

It is recommended that a greater than 10% dropout rate should be accounted for in sample size calculation for future studies. Patient-reported outcomes such as comfort, appearance, and resiliency to compare between retainer types should also be included.

CONCLUSIONS

There was no statistically significant difference found between the two retainer groups (HR and mVFR) during a 12-month retention period.

The null hypothesis could not be rejected: HR and mVFR had similar clinical effectiveness in the retention of transverse expansion during a 12-month retention period.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Dr Reuben How and the staff of all the orthodontic clinics involved.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (Grant GGPM 2018-049). The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Herold JS. Maxillary expansion: a retrospective study of three methods of expansion and their long-term sequelae. Br J Orthod . 1989;16:195–200. doi: 10.1179/bjo.16.3.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Melrose C, Millett DT. Toward a perspective on orthodontic retention? Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop . 1998;113:507–514. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(98)70261-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh P, Grammati S, Kirschen R. Orthodontic retention patterns in the United Kingdom. J Orthod . 2009;36:115–121. doi: 10.1179/14653120723040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manzon L, Fratto G, Rossi E, Buccheri A. Periodontal health and compliance: a comparison between Essix and Hawley retainers. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop . 2018;153:852–860. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2017.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindauer SJ, Shoff RC. Comparison of Essix and Hawley retainers. J Clin Orthod . 1998;32:95–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sheridan JJ, LeDoux W, McMinn R. Essix retainers: fabrication and supervision for permanent retention. J Clin Orthod . 1993;27:37–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gill DS, Naini FB, Jones A, Tredwin CJ. Part-time versus full-time retainer wear following fixed appliance therapy: a randomized prospective controlled trial. World J Orthod . 2007;8:300–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anbuselvan GJ, Senthil Kumar KP, Tamilzharasi S, Karthi M. Essix appliance revisited. Natl J Integr Res Med . 2012;3:125–138. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cope JF, Lamont T. Orthodontic retention: three methods trialed. Evid Based Dent . 2016;17:29–30. doi: 10.1038/sj.ebd.6401157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edman Tynelius G, Petrén S, Bondemark L, Lilja-Karlander E. Five-year postretention outcomes of three retention methods: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Orthod . 2015;37:345–353. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cju063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O'Rourke N, Albeedh H, Sharma P, Johal A. The effectiveness of bonded and vacuum formed retainers: a prospective randomized controlled clinical trial. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop . 2016;150:406–414. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2016.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barlin S, Smith R, Reed R, Sandy J, Ireland AJ. A retrospective randomized double-blind comparison study of the effectiveness of Hawley vs vacuum-formed retainers. Angle Orthod . 2011;81:404–409. doi: 10.2319/072610-437.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rowland H, Hichens L, Williams A, et al. The effectiveness of Hawley and vacuum-formed retainers: a single-center randomized controlled trial. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop . 2007;132:730–737. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2006.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Demir A, Babacan H, Nalcacı R, Topcuoglu T. Comparison of retention characteristics of Essix and Hawley retainers. Korean J Orthod . 2012;42:255–262. doi: 10.4041/kjod.2012.42.5.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Edman Tynelius G, Bondemark L, Lilja-Karlander E. Evaluation of orthodontic treatment after 1 year of retention—a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Orthod . 2010;32:542–547. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjp145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meade MJ, Millett DT, Cronin M. Social perceptions of orthodontic retainer wear. Eur J Orthod . 2014;36:649–656. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjt087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Renkema AM, Renkema A, Bronkhorst E, Katsaros C. Long-term effectiveness of canine-to-canine bonded flexible spiral wire lingual retainers. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop . 2011;139:614–621. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2009.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Valiathan M, Hughes E. Results of a survey-based study to identify common retention practices in the United States. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop . 2010;137:170–177. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2008.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eshky R, Althagafi N, Alsaati B, Alharbi R, Kassim S, Alsharif A. Self-perception of malocclusion and barriers to orthodontic care: a cross-sectional study in Al-Madinah, Saudi Arabia. Patient Prefer Adherence . 2019;13:1723–1732. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S219564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hamdan AM. The relationship between patient, parent and clinician perceived need and normative orthodontic treatment need. Eur J Orthod . 2004;26:265–271. doi: 10.1093/ejo/26.3.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Komazaki Y, Fujiwara T, Ogawa T, et al. Prevalence and gender comparison of malocclusion among Japanese adolescents: a population-based study. J World Fed Orthod . 2012;1:e67–e72. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Littlewood SJ, Kandasamy S, Huang G. Retention and relapse in clinical practice. Aust Dent J . 2017;62:51–57. doi: 10.1111/adj.12475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blake M, Garvey MT. Rationale for retention following orthodontic treatment. J Can Dent Assoc (Tor) . 1998;64:640–643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Little RM. Stability and relapse of dental arch alignment. Br J Orthod . 1990;17(3):235–241. doi: 10.1179/bjo.17.3.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bishara S, Treder J, Jakobsen J. Facial and dental changes in adulthood. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop . 1994;106:175–186. doi: 10.1016/S0889-5406(94)70036-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burke SP, Silveira AM, Jane Goldsmith L, Yancey JM, Van Stewart A, Scarfe WC. A meta-analysis of mandibular intercanine width in treatment and postretention. Angle Orthod . 1998;68:53–60. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1998)068<0053:AMAOMI>2.3.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sinclair P, Little R. Maturation of untreated normal occlusions. Am J Orthod . 1983;83(2):114–123. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9416(83)90296-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ledvinka J. Vacuum-formed retainers more effective than Hawley retainers. Evid Based Dent . 2009;10:47. doi: 10.1038/sj.ebd.6400650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramazanzadeh B, Ahrari F, Hosseini Z. The retention characteristics of Hawley and vacuum formed retainers with different retention protocols. J Clin Exp Dent . 2018;10:e224–e231. doi: 10.4317/jced.54511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hichens L, Rowland H, Williams A, et al. Cost-effectiveness and patient satisfaction: Hawley and vacuum-formed retainers. Eur J Orthod . 2007;29:372–378. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjm039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saleh M, Hajeer MY, Muessig D. Acceptability comparison between Hawley retainers and vacuum-formed retainers in orthodontic adult patients: a single-centre, randomized controlled trial. Eur J Orthod . 2017;39:453–461. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjx024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kristman V, Côté P, Manno M. Loss to follow-up in cohort studies: how much is too much? Eur J Epidemiol . 2004;19:751–760. doi: 10.1023/b:ejep.0000036568.02655.f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walters SJ, Dos Anjos Henriques-Cadby IB, Bortolami O, et al. Recruitment and retention of participants in randomised controlled trials: a review of trials funded and published by the United Kingdom Health Technology Assessment Programme. BMJ Open . 2017;7:1–10. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elengoe A. COVID-19 outbreak in Malaysia. Osong Public Heal Res Perspect . 2020;11:93–100. doi: 10.24171/j.phrp.2020.11.3.08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suri S, Vandersluis Y, Kochhar A, et al. Clinical orthodontic management during the COVID-19 pandemic. Angle Orthod . 2020;90:473–484. doi: 10.2319/033120-236.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zotti F, Zotti R, Albanese M, Nocini PF, Paganelli C. Implementing post-orthodontic compliance among adolescents wearing removable retainers through Whatsapp: a pilot study. Patient Prefer Adherence . 2019;13:609–615. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S200822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]