Abstract

Unlike many other aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases, alanyl-tRNA synthetase (AlaRS) retains a conserved prototype structure throughout biology. While Caenorhabditis elegans cytoplasmic AlaRS (CeAlaRSc) retains the prototype structure, its mitochondrial counterpart (CeAlaRSm) contains only a residual C-terminal domain (C-Ala). We demonstrated herein that the C-Ala domain from CeAlaRSc robustly binds both tRNA and DNA. It bound different tRNAs but preferred tRNAAla. Deletion of this domain from CeAlaRSc sharply reduced its aminoacylation activity, while fusion of this domain to CeAlaRSm selectively and distinctly enhanced its aminoacylation activity toward the elbow-containing (or L-shaped) tRNAAla. Phylogenetic analysis showed that CeAlaRSm once possessed the C-Ala domain but later lost most of it during evolution, perhaps in response to the deletion of the T-arm (part of the elbow) from its cognate tRNA. This study underscores the evolutionary gain of C-Ala for docking AlaRS to the L-shaped tRNAAla.

INTRODUCTION

Eukaryotes contain two sets of aaRSs

Aminoacylation of tRNA by aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase (aaRS) establishes the universal genetic code (1). The accuracy of tRNA aminoacylation is crucial for maintaining the fidelity of protein synthesis. AaRSs verify a tRNA’s identity by recognizing certain identity elements present on the tRNA, which can be single nucleotides, base pairs or even post-transcriptional modifications (1–3). Identity elements often reside in the acceptor stem or the anticodon loop of a tRNA, and they are normally conserved across a wide range of species. In eukaryotic cells, the nuclear genome normally encodes two distinct sets of aaRSs, one functioning in the cytoplasm and the other functioning in the mitochondria. For example, Vanderwaltozyma polyspora, Homo sapiens and Caenorhabditis elegans each possess two distinct nuclear alanyl-tRNA synthetase (AlaRS) genes, one encoding the cytoplasmic form and the other encoding its mitochondrial counterpart (4–6). Nevertheless, in some cases, both isoforms of a given aaRS are produced from a single gene through alternative transcription and translation, examples of which include the histidyl-tRNA synthetase genes of C. elegans and Saccharomyces cerevisiae (7,8).

AlaRS retains an evolutionarily conserved modular structure

Most aaRSs expanded by recruiting novel noncatalytic appended domains during evolution. Conversely, almost all AlaRSs retained the same prototype structure across all three domains of life (Figure 1). The prototype structure consists of four functional domains that are responsible for catalysis, tRNA recognition, editing and oligomerization (9). Prokaryotic AlaRSs are normally α4 tetramers, while those from eukaryotes are monomers (10). The catalytic and tRNA recognition domains are often referred to collectively as the aminoacylation domain. The editing domain is responsible for hydrolysis of the mischarged Ser- or Gly-tRNAAla and is therefore critical for maintaining translational fidelity and preventing cytotoxicity. In mice, even a mild defect in editing activity leads to neural degeneration (11). The C-terminal domain (C-Ala) is highly diverse across species and plays an important role in both aminoacylation and editing (12). A prokaryotic C-Ala domain consists of an N-terminal helical subdomain, which mediates dimer formation, and a C-terminal globular subdomain, which binds tRNA (Supplementary Figure S1) (13,14). Recent studies further showed that C-Ala has been repurposed from tRNA binding in prokaryotes to DNA binding in humans (14). Exceptions to this four-domain rule have been recovered. For example, Leishmania major AlaRS contains an extra insertion domain upstream of the editing domain (15), while Nanoarchaeum equitans AlaRS is split into two parts (16).

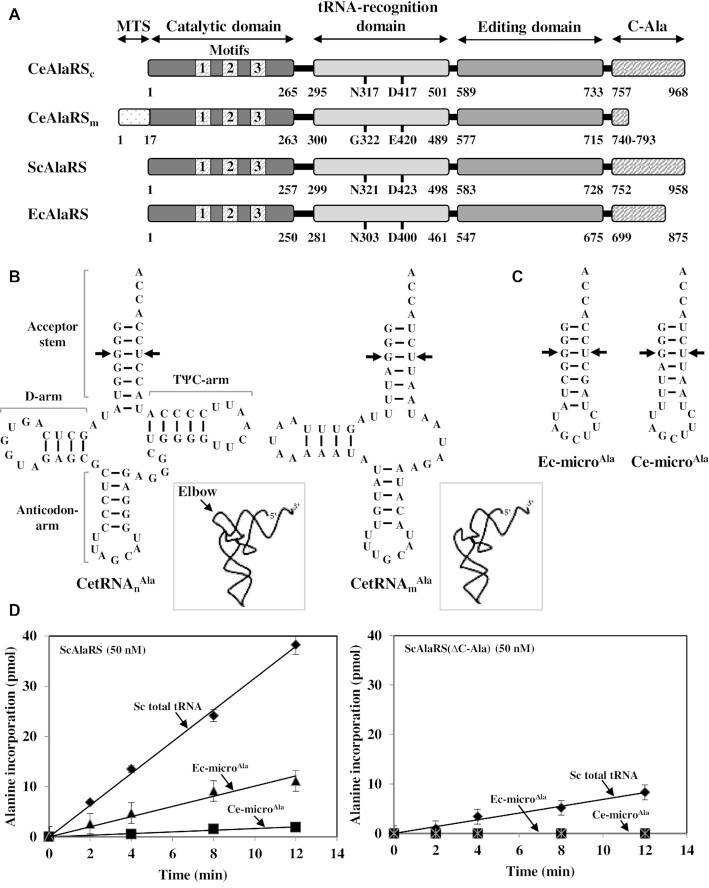

Figure 1.

Caenorhabditis elegans AlaRS and tRNAAla. (A) Modular organization of CeAlaRSc, CeAlaRSm, ScAlaRS and EcAlaRS. Relative positions of the functional domains and motifs in CeAlaRSs are labeled. The amino acid residues that presumably make contacts with G3:U70 are labeled. (B) CetRNAnAla and CetRNAmAla. The identity elements G3:U70 are marked with an arrow for clarity. Additionally, the representative three-dimensional structures of CetRNAsAla (boxed) are shown, with an emphasis on the elbow. (C) Ec-microAla and Ce-microAla. (D) Aminoacylation of tRNA by ScAlaRS and ScAlaRS(ΔC-Ala).

G3:U70 are the universal identity elements of tRNAAla

AlaRS identifies its cognate tRNA through a single GU base pair, G3:U70, in the acceptor stem without making contact with the anticodon. Three aaRSs, alanyl-, leucyl- and seryl-tRNA synthetases, have been shown to lack an anticodon-binding domain (17). G3:U70 is absent from all other tRNAs but is strictly conserved in tRNAAla ranging from Escherichia coli to human cytoplasm (18–20). Transferring G3:U70 into a nonalanine tRNA also converts it into an alanine acceptor both in vitro and in vivo (21). In a sense, AlaRS exemplifies an ancient aaRS, which identifies its tRNA through recognition of an operational RNA code (a specific sequence or structure) embedded in the acceptor stem (22). A structural study on AlaRS of the archaea Archaeoglobus fulgidus in complex with tRNAAla revealed that two amino acid residues—N359 and D450—in the tRNA recognition domain make specific hydrogen bonds with G3:U70, and thereby establish it as an alanine acceptor (13). These two amino acid residues are highly conserved in AlaRS, regardless of its evolutionary origin. Nevertheless, noncanonical AlaRSs that deviate from the conserved features have been found. For example, human mitochondrial AlaRS recognizes the variable loop in its cognate tRNAAla (5), and Drosophila melanogaster mitochondrial AlaRS recognizes a shifted GU base pair, G2:U71, in its cognate tRNAAla (23).

Caenorhabditis elegans mitochondrial AlaRS lost most of its C-Ala

In contrast to canonical AlaRSs, C. elegans mitochondrial AlaRS (CeAlaRSm) lost almost all of its C-Ala (6), and its cognate tRNA (CetRNAmAla) lacks the T-arm, which together with the D-arm forms the elbow of the L-shaped tRNA. As all the mitochondrial tRNAs in this nematode are defective in either the D- or T-arm (24), they cannot fold into the typical L form. An earlier study reported that CeAlaRSm still retains G3:U70 specificity (6). However, little is known about the evolutionary significance of gaining or losing C-Ala and its true impact on enzyme activity. We showed herein that C-Ala of the nematode cytoplasmic AlaRS (CeAlaRSc) is both a tRNA- and a DNA-binding domain. Removal of C-Ala from CeAlaRSc sharply reduced its aminoacylation activity, while fusion of this domain to CeAlaRSm selectively and distinctly enhanced its activity toward the elbow-containing tRNAAla. This study highlights the evolution and function of the C-Ala domain.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of plasmids

Cloning of the gene encoding CeAlaRSc or CeAlaRSm into pADH (a high-copy-number yeast vector with an ADH promoter) and pTEF1 (a high-copy-number yeast vector with a TEF1 promoter) followed a standard protocol. In brief, a set of gene-specific primers was designed to amplify the open reading frame of the gene via polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using C. elegans complementary DNA as the template. The forward primer with an NdeI site was annealed to the 5′-end sequence of the open reading frame, while the reverse primer with an XhoI site was annealed to the 3′-end sequence immediately upstream of the stop codon. Note that the native MTS (mitochondrial targeting signal) sequence of CeAlaRSm was not included in the construct. The PCR-amplified DNA fragment was treated with NdeI and XhoI before cloning into the aforementioned vectors. Fusion of a heterologous MTS to CeAlaRSm followed a strategy described earlier (25). To fuse C-Ala to the N- or C-terminus of CeAlaRSm, an NdeI–NdeI or XhoI–XhoI fragment (containing bp +2269 to +2904 of CeAlaRSc) was PCR amplified and cloned into the 5′ NdeI or 3′ XhoI site of the open reading frame encoding CeAlaRSm, yielding (C-Ala)-CeAlaRSm or CeAlaRSm-(C-Ala). To delete C-Ala from CeAlaRSc, an NdeI–XhoI fragment (containing bp +1 to +2268 of CeAlaRSc) was PCR amplified and cloned into appropriate vectors. Cloning of the genes encoding ScAlaRS and its C-Ala deletion mutant followed a similar strategy.

For protein purification, the target genes were individually cloned into pET21b (an E. coli expression vector), and the resultant plasmids were transformed into BL21-CodonPlus(DE3) for protein expression. His6-tagged proteins were purified to homogeneity through Ni-NTA column chromatography as previously described (25). Western blotting was carried out using an HRP-conjugated anti-His6 tag antibody as the probe (26). Protein–RNA or protein–DNA binding affinities were determined by electrophoretic mobility shift assay as described previously (27). GFP microscopy followed a protocol described earlier (28).

Rescue assay for cytoplasmic activity on 5-FOA

Construction of a yeast haploid ALA1 knockout (KO) strain (MATα, ala1::kanMX4, his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 lyS3Δ0 ura3Δ0) was reported earlier (29,30). Note that ALA1 is a dual-functional gene that encodes cytoplasmic and mitochondrial forms of AlaRS through alternative initiation of translation from two in-frame initiator codons (30). To test whether a heterologous AlaRS gene can functionally substitute for the cytoplasmic activity of ALA1, a test plasmid carrying the target gene and a LEU2 marker was transformed into the KO strain, and the resultant transformant was tested for its ability to grow on 5-fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA, 1 mg/ml) plates. Because 5-FOA can be metabolized by yeast to a toxic compound in the presence of URA3, the transformant must evict the maintenance plasmid [with a wild-type (WT) ALA1 gene and a URA3 marker] on 5-FOA to survive. Thus, the transformant cannot grow on 5-FOA unless the test plasmid encodes a functional cytoplasmic AlaRS.

Rescue assay for mitochondrial activity on YPG

To test whether a heterologous AlaRS gene can functionally substitute for the mitochondrial activity of ALA1, a test plasmid (with the target gene and a LEU2 marker) and a second maintenance plasmid (with an initiator mutant of ALA1 that encodes only cytoplasmic AlaRS and a HIS3 marker) were cotransformed into the yeast KO strain (30). The first maintenance plasmid (with a URA3 marker) was evicted from the cotransformant on 5-FOA. Following 5-FOA selection, the cotransformant (with the second maintenance plasmid and test plasmid) was further tested on YPG plates. Because glycerol (a nonfermentable carbohydrate) is the sole carbon source in YPG, yeast cells must retain functional mitochondria to metabolize glycerol and survive in this medium. Thus, the cotransformant cannot grow on YPG unless the test plasmid encodes a functional mitochondrial AlaRS.

In vitro transcription of tRNA

Preparation of the CetRNAnAla, CetRNAmAla, Ce-microAla and Ec-microAla transcripts followed a standard protocol. Briefly, a DNA duplex containing a T7 promoter followed by a sequence encoding the tRNA or microhelix was cloned into the SmaI site of pUC18. The transcription template was enriched by PCR amplification of the insert. In vitro transcription was performed at 37°C for 3 h with 0.3 μM T7 RNA polymerase in 20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM MgCl2, 5 mM DTT, 1 mM spermidine and 2 mM of each NTP. The transcript was purified using a 15% denaturing urea–polyacrylamide gel. After ethanol precipitation and vacuum drying, the RNA pellet was dissolved in 1× TE buffer [20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0) and 1 mM EDTA], refolded by heating to 65°C and gradually cooled to room temperature in the absence of MgCl2. In vitro transcription of CetRNAnAla followed a similar protocol.

Aminoacylation assay

Aminoacylation was performed at ambient temperature in a buffer containing 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 50 mM KCl, 15 mM MgCl2, 5 mM dithiothreitol, 10 mM ATP, 0.1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin, 100 μM yeast total tRNA or 5 μM tRNA (or microhelix), 20 μM alanine (1.34 μM 3H-alanine; PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA), and 50 or 100 nM AlaRS. Reactions were quenched at various time points by spotting 10 μl aliquots of the reaction mixture onto Whatman filters (Maidstone, Kent, UK) that had been presoaked in 5% trichloroacetic acid and 2 mM alanine. The filters were washed three times for 15 min each in ice-cold 5% trichloroacetic acid before liquid scintillation counting. Active protein concentrations were determined by active site titration as previously described (31). Aminoacylation data were obtained from three independent experiments and averaged.

RESULTS

Caenorhabditis elegans contains a canonical and a noncanonical AlaRS

Caenorhabditis elegans possesses two distinct nuclear AlaRS genes, one encoding the cytoplasmic form (CeAlaRSc) and the other encoding its mitochondrial counterpart. CeAlaRSm contains a residual C-Ala (with ∼54 amino acid residues) and an extra cleavable N-terminal MTS. Upon post-translational processing, the most distinct difference between the two isoforms is C-Ala (Figure 1A). The nematode nuclear-encoded cytoplasmic tRNAAla (CetRNAnAla) retained a cloverleaf structure and is predicted to fold into an L form, while its mitochondrial isoacceptor (CetRNAmAla) lacked the T-arm and is predicted to fold into an elbowless crescent-shaped structure (Figure 1B). To determine the tRNA preferences of AlaRSc and its C-Ala deletion construct, three tRNA substrates, yeast total or unfractionated tRNA (that contains all 20 different tRNAs), Ec-microAla (an acceptor-stem microhelix derived from EctRNAAla) and Ce-microAla (an acceptor-stem microhelix derived from CetRNAmAla) (Figure 1C), were used as the substrates for aminoacylation. It is worth mentioning that the G1:U72 base pair in the acceptor stem of Ce-microAla has been shown to act as an anti-determinant for aminoacylation by EcAlaRS (6). The cloverleaf structures of SctRNAnAla, SctRNAmAla and EctRNAAla are shown in Supplementary Figure S2.

For comparison, we first checked the tRNA preferences of S. cerevisiae AlaRS (ScAlaRS) and its C-Ala deletion construct. Figure 1D showed that ScAlaRS prefers SctRNAnAla over Ec-microAla (4-fold) and Ec-microAla over Ce-microAla (8-fold). Deletion of C-Ala drastically reduced its aminoacylation activity toward SctRNAnAla (5-fold) and abolished its aminoacylation activity toward both microhelices (Figure 1D). No detectable aminoacylation activity toward the microhelices was observed even when the concentration of the deletion construct was increased 4-fold (Supplementary Figure S3). Complementation assay on 5-FOA using a yeast ALA1 KO strain showed that deletion of C-Ala from ScAlaRS completely eliminates its rescue activity (Supplementary Figure S4). As expected, E. coli AlaRS exhibited a similar preference for these three tRNA substrates (Supplementary Figure S5). Conceivably, canonical AlaRSs prefer the L-shaped tRNAAla, and G1:U72 blocked the aminoacylation of Ce-microAla by noncognate enzymes.

Deletion of C-Ala impairs the aminoacylation activity of CeAlaRSc

We next determined the aminoacylation activity of CeAlaRSc under similar conditions, but with the inclusion of two more tRNAs, CetRNAnAla and CetRNAmAla. As shown in Figure 2A, CeAlaRSc exhibited a tRNA preference similar to those of ScAlaRS and EcAlaRS. It strongly preferred SctRNAAla over Ec-microAla (∼4-fold) and failed to charge Ce-microAla to a detectable level. Like SctRNAnAla, CetRNAnAla, but not CetRNAmAla, was a preferable substrate for CeAlaRS. Deletion of C-Ala from this enzyme drastically impaired its aminoacylation activity toward all tRNA substrates used (Figure 2A). Notably, the deletion mutant failed to charge CetRNAmAla, Ec-microAla and Ce-microAla to a detectable level even when its concentration was increased 5-fold (Supplementary Figure S6). This result indicates that C-Ala plays an important role in the aminoacylation of tRNAAla by CeAlaRSc.

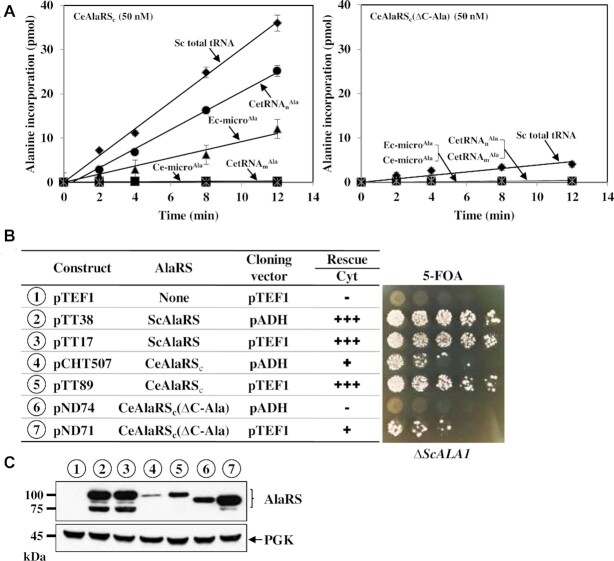

Figure 2.

C-Ala is important for the aminoacylation activity of CeAlaRSc. (A) Aminoacylation assay. The aminoacylation activities of CeAlaRSc and CeAlaRSc(ΔC-Ala) were determined using various tRNAs as substrates. (B) Complementation assay. The rescue activities of CeAlaRSc and its C-terminal deletion construct were determined by transforming the test plasmid into a yeast ALA1 KO strain and plating the resultant transformants on 5-FOA. The symbols ‘+’ and ‘−’ denote positive and negative complementation, respectively. (C) Western blotting. The protein expression levels of these constructs were determined by western blotting using an anti-His6-tagged antibody as the probe. Constructs used in (B) and (C) are numbered for clarity.

We next examined whether CeAlaRSc and its C-terminal deletion mutant can rescue the growth defect of a yeast ALA1 KO strain on 5-FOA (summarized in Figure 2B). The cDNA encoding CeAlaRSc or its derivative was cloned into two high-copy-number yeast shuttle vectors, pADH and pTEF1, with one having a strong ADH promoter and the other having a superstrong TEF1 promoter (32). As expected, ScAlaRS cloned in either vector (as a positive control) robustly supported the growth of the KO strain on 5-FOA. In contrast, CeAlaRSc cloned in pADH only weakly rescued the KO strain. Its rescue activity was markedly increased when it was cloned into pTEF1. The C-terminal deletion construct showed a negative and a weak positive phenotype when cloned in pADH and pTEF1, respectively. Therefore, deletion of C-Ala from CeAlaRSc substantially reduced its ability to rescue ALA1-dependent growth defects.

To confirm the level of AlaRS expression in the KO strain, western blotting was carried out using an anti-His6-tagged antibody as the probe and phosphoglycerate kinase as the loading control (Figure 2C). As expected, CeAlaRSc cloned in pTEF1 had a protein expression level much higher than that of its pADH counterpart. The equivalent occurred with its C-terminal deletion derivative. Unexpectedly, the C-terminal deletion construct had a protein expression level much higher than that of its WT counterpart when cloned in the same vector. However, contrary to our expectations, ScAlaRS cloned in these two vectors had a similar level of protein expression. It thus appears that the expression of this gene is under autogenous translational repression, a scenario reminiscent of yeast histidyl-tRNA synthetase (33). The strong double bands shown in ScAlaRS are likely to result from partial degradation of the overexpressed protein. It is noteworthy that although WT CeAlaRSc had a protein expression level lower than that of its deletion counterpart cloned in the same vector (Figure 2C), it showed a stronger rescue activity (Figure 2B), further underlining the involvement of C-Ala in rescuing ALA1-dependent growth defects through aminoacylation (Figure 2).

Fusion of C-Ala to CeAlaRSm selectively enhances its aminoacylation activity toward the L-shaped tRNAAla

The elbow of the L-shaped tRNA is formed by interactions between the T- and D-arms. As CetRNAmAla lacks the T-arm, it is expected to fold into an elbowless crescent-like shape (Figure 1B). This raises the question of whether its cognate enzyme CeAlaRSm can still efficiently recognize the L-shaped tRNAAla. Figure 3A showed that CeAlaRSm can only charge SctRNAAla poorly, with an efficiency ∼15-fold lower than that of CeAlaRSc (compare Figures 2A and 3A). Unlike CeAlaRSc, which strongly preferred the L-shaped tRNAAla (Figure 2A), CeAlaRSm had no such preference. This mitochondrial enzyme charged SctRNAnAla, Ec-microAla and Ce-microAla to a similar level. Strikingly, fusion of C-Ala of CeAlaRSc to CeAlaRSm enhanced its aminoacylation activity up to ∼3-fold toward SctRNAAla but had little effect on its activity toward the microhelices and CetRNAmAla (Figure 3A). This result suggests that, like a prokaryotic C-Ala (13,14), the nematode C-Ala domain is an elbow-specific tRNA-binding domain. To further explore whether C-Ala can act via a trans-acting mechanism to promote the aminoacylation activity of CeAlaRSm, C-Ala was purified and added in different ratios to the reactions catalyzed by CeAlaRSm. As shown in Supplementary Figure S7, C-Ala failed to act via a trans-acting mechanism to promote the aminoacylation activity of CeAlaRSm, emphasizing the role of C-Ala in targeting the fusion enzyme to L-shaped tRNAAla.

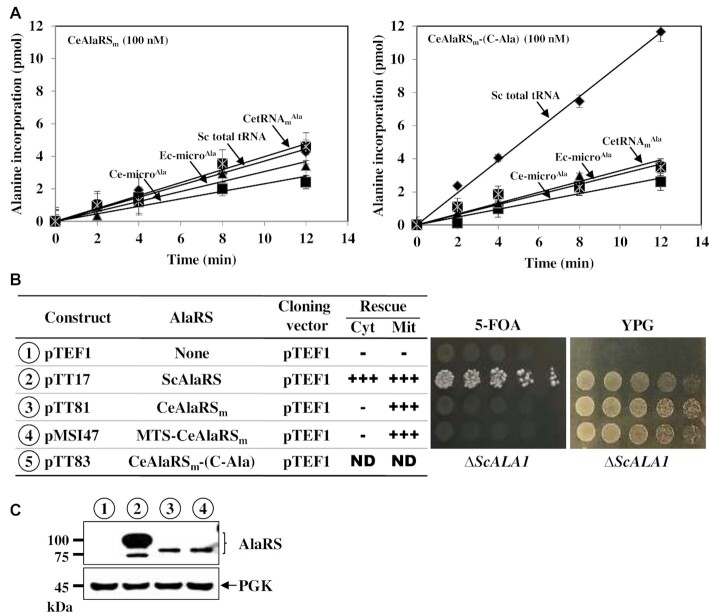

Figure 3.

C-Ala enhances the aminoacylation activity of CeAlaRSm toward the L-shaped tRNAAla. (A) Aminoacylation assay. The aminoacylation activities of CeAlaRSm and CeAlaRSm-(C-Ala) were determined using various tRNAs as substrates. (B) Complementation assay. The rescue activities of CeAlaRSm and its C-Ala fusion construct were determined by transforming the test plasmid into a yeast ALA1 KO strain and plating the resultant transformants on both 5-FOA and YPG. The symbols ‘+’ and ‘−’ denote positive and negative complementation, respectively. ND indicates not determined due to lack of transformants. (C) Western blotting. The protein expression levels of these constructs were determined by western blotting using an anti-His6-tagged antibody as the probe. Constructs used in (B) and (C) are numbered for clarity.

We next examined whether CeAlaRSm and its fusions cloned in pTEF1 can be substituted for the cytoplasmic (on 5-FOA) and mitochondrial (on YPG) functions of yeast ALA1 (summarized in Figure 3B). Note that ALA1 is a dual-functional gene that encodes both the cytoplasmic and mitochondrial forms of ScAlaRS through alternative initiation of translation (29). As expected, ScAlaRS cloned in pTEF1 rescued the growth defects of the KO strain on both 5-FOA and YPG. Unexpectedly, CeAlaRSm (lacking its native MTS) effectively rescued the mitochondrial defect, but not the cytoplasmic defect, of the KO strain, regardless of whether it was fused with a heterologous MTS. This result suggests that CeAlaRSm can charge the yeast mitochondrial tRNAAla and mitochondria require only a minimal AlaRS activity to maintain their normal function. In addition, it implies that the mature CeAlaRSm carries a cryptic MTS, which allows a portion of the enzyme to be imported into mitochondria to function there, a scenario often seen in aaRS rescue assays (7,30,34). Unfortunately, no transformants carrying the CeAlaRSm-(C-Ala) fusion were available for the rescue assays. As the editing activity of ScAlaRS is crucial for the survival of yeast (35), perhaps fusion of C-Ala to the C-terminus of CeAlaRSm disturbed the enzyme’s editing activity, leading to mistranslation and cellular toxicity.

Interestingly, fusion of C-Ala to the N-terminus of the enzyme yielded a fusion enzyme, (C-Ala)-CeAlaRSm, that conferred a weak positive growth phenotype on the KO strain and slightly enhanced (1.6-fold) its activity on tRNAAlain vitro (Supplementary Figure S8), lending further support to the observation that C-Ala enhances the aminoacylation activity of CeAlaRSm toward the L-shaped tRNAAla. Given the long distance between the N-terminus of the aminoacylation domain and the elbow of the bound tRNAAla (10), the fused C-Ala domain might act in cooperation with the aminoacylation and editing domains of CeAlaRSm to recruit tRNAAla, instead of being directly involved in mediating the formation of a productive enzyme/tRNA complex.

Western blotting showed that CeAlaRSm or its fusions cloned in pTEF1 have a protein expression level much lower than that of ScAlaRS cloned in the same vector (Figure 3C). As CeAlaRSm can only poorly charge SctRNAAlain vitro (Figure 3A), it was incredible to find that this enzyme can rescue the mitochondrial defect of the KO strain with such a low level of protein expression (Figure 3B and C). GFP microscopy and fractionation assay further showed that CeAlaRSm (without an MTS) is predominantly localized in the cytoplasm, while MTS-CeAlaRSm is predominantly localized in the mitochondria. However, we also noticed that a minor fraction of CeAlaRSm is colocalized in the mitochondria (Supplementary Figure S9). Conceivably, a minimal level of CeAlaRSm is sufficient to maintain the normal mitochondrial function.

The nematode C-Ala is both a tRNA- and a DNA-binding domain

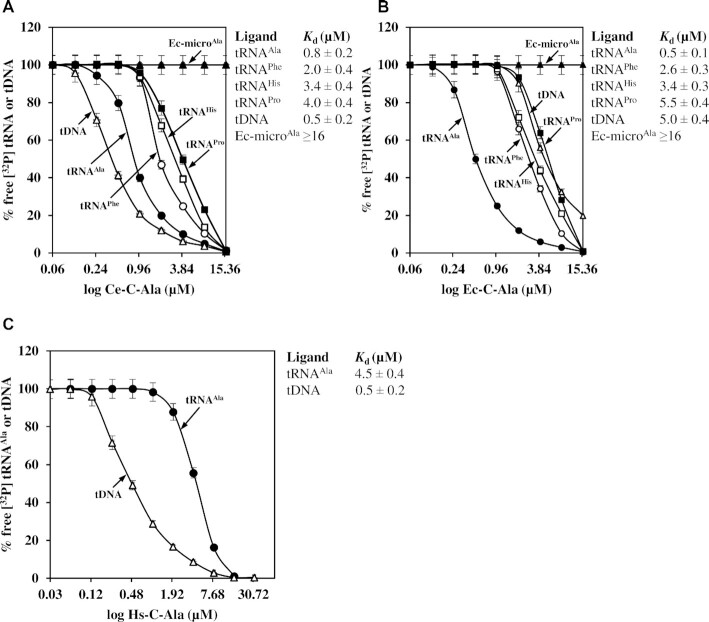

Although C. elegans C-Ala (Ce-C-Ala) has a protein sequence more closely related to human C-Ala than to prokaryotic C-Ala (14), our aminoacylation data suggested that this domain retains tRNA-binding activity (Figure 3). To provide direct evidence, Ce-C-Ala was cloned, purified and analyzed using an electrophoretic mobility shift assay. As a comparison, E. coli C-Ala (Ec-C-Ala) was also purified and analyzed. Six ligands were used in the assay, including CetRNAnAla, SctRNAnPhe, SctRNAnHis, Bacillus thuringiensis tRNAPro (BttRNAPro), Ec-microAla and CetDNAAla (which encodes CetRNAnAla). As shown in Figure 4A, Ce-C-Ala bound tRNAAla, tRNAPhe, tRNAHis and tRNAPro (with Kd values of 0.8, 2.0, 3.4 and 4.0 μM, respectively) but did not bind Ec-microAla to an appreciable level (with a Kd value of >16 μM). This result clearly indicates that the Ce-C-Ala domain is a structure-specific tRNA-binding domain, with a distinct preference for tRNAAla. Despite the high sequence divergence from Ce-C-Ala (∼34% identity), Ec-C-Ala retained a very similar tRNA preference, with Kd values of 0.5, 2.6, 3.4, 5.5 and >16 μM for tRNAAla, tRNAPhe, tRNAHis, tRNAPro and Ec-microAla, respectively (Figure 4B). Unexpectedly, these two C-Ala domains possessed quite different DNA-binding properties. Ec-C-Ala poorly bound to DNA (with a Kd value of 5.0 μM), while Ce-C-Ala bound to DNA robustly (with a Kd value of 0.5 μM). Thus, the Ce-C-Ala domain is both a tRNA-binding domain and a DNA-binding domain (Figures 3 and 4). For comparison, we also purified human C-Ala under normal (or reducing) conditions as previously described (14). Unexpectedly, monomeric human C-Ala robustly bound DNA (with a Kd value of 0.5 μM), but poorly bound tRNAAla (with a Kd value of 4.5 μM) (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

C-Ala of CeAlaRSc robustly binds both tRNA and DNA. Protein–RNA or protein–DNA binding affinities were determined by an electrophoretic mobility shift assay with protein concentrations ranging from 16 to 0.0625 or 32 to 0.03 μM. The 32P-labeled CetRNAnAla (•), SctRNAnPhe (○), SctRNAnHis (□), BttRNAPro (▪), Ec-microAla (▴) and CetDNAAla (Δ) are shown. The tRNA- and DNA-binding affinities of (A) Ce-C-Ala, (B) Ec-C-Ala and (C) Hs-C-Ala. The equilibrium response at each concentration was fitted to a single-site binding model. Error bars are standard deviations from triplicates.

To determine the oligomeric status of Ce-C-Ala in solution, a sedimentation velocity analytical ultracentrifugation experiment was carried out. As shown in Supplementary Figure S10, Ce-C-Ala formed a monomer and no homodimer was detected. To test whether DNA binding is a property that is exclusive to the stand-alone C-Ala domain, the full-length CeAlaRSc was purified and tested. Supplementary Figure S11 shows that CeAlaRSc bound DNA with a Kd value of 1.5 μM (3-fold higher than that of Ce-C-Ala).

Lack of an intact C-Ala domain in CeAlaRSm resulted from secondary loss of this domain

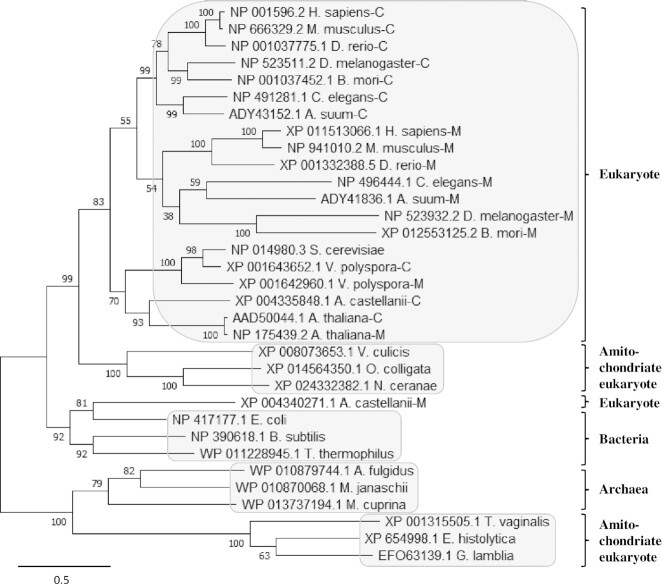

To track the evolutionary origin of CeAlaRSm and its relationship with CeAlaRSc, phylogenetic analysis was carried out using AlaRSs retrieved from all three domains of life, with a particular emphasis on eukaryotes (36,37). As illustrated in Figure 5, the majority of eukaryotic AlaRSs are clustered into a monophyletic group that is closer to bacteria, and therefore they should be regarded as having a mitochondrial origin (4). Nevertheless, amitochondriate (eukaryotes without mitochondria) AlaRSs are clustered into two independent monophyletic groups. One group, including V. culicis, N. ceranae and O. colligate, is closer to the major eukaryotic group (mitochondrial origin), while the other, including E. histolytica, G. lamblia and T. vaginalis, is closer to the archaeal group instead (Figure 5). Thus, not all eukaryotic AlaRSs are of the same evolutionary origin. It is also noteworthy that none of the contemporary eukaryotes retain both types of AlaRS (archaeal and mitochondrial types), suggesting that the functional substitution process between the two types of AlaRS occurred early in evolution.

Figure 5.

Phylogenetic tree of AlaRS. The evolutionary history was inferred by using the maximum likelihood method and JTT matrix-based model. Initial tree(s) for the heuristic search were obtained automatically by applying neighbor-joining and BioNJ algorithms to a matrix of pairwise distances estimated using the JTT model. This analysis involved 33 AlaRS sequences. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA X.

As all the cytoplasmic and mitochondrial AlaRSs in the major eukaryotic group are of mitochondrial origin, the original eukaryote-type AlaRS must have been lost before speciation of these eukaryotes. Moreover, the AlaRS paralogs existing in each of these organisms, including those for CeAlaRS isoforms, were descended from duplication of a mitochondrion-type predecessor (Figure 5). Therefore, both CeAlaRS isoforms should retain the same organization with four domains. We determined that the selective absence of most of C-Ala from CeAlaRSm most likely resulted from secondary loss of this domain. That is, CeAlaRSm once possessed a full-length C-Ala, but lost it later during evolution, perhaps as a response to deletion of the T-arm from its cognate tRNA (or the other way around) (Supplementary Figure S12). To date, such a scenario has only been found in C. elegans and some of its close relatives, such as Ascaris suum. It is still unclear whether C-Ala or TψC-arm was lost first during evolution.

DISCUSSION

Distinct features of the prokaryotic and eukaryotic C-Ala domains

Despite AlaRS retaining a prototype structure throughout biology, C-Ala is highly diverged in protein sequences (12,14). Deletion of C-Ala from AlaRS of E. coli or A. fulgidus sharply reduced its aminoacylation activities (12,14,38). In contrast, deletion of C-Ala from human cytoplasmic AlaRS had little effect on its aminoacylation activity (14). It is believed that human C-Ala has little contact with the bound tRNA. In the case of CeAlaRSc, deletion of C-Ala from this enzyme severely impaired its aminoacylation activity (Figure 2), suggesting that similar to prokaryotic C-Ala, the nematode C-Ala plays an important role in tRNA aminoacylation. A structural study further unveiled that C-Ala from prokaryotes folds into a homodimer with a parallel organization (10) and binds the elbow of the L-shaped tRNAAla (12). In contrast, human C-Ala forms a homodimer with an antiparallel organization (under oxidizing conditions) and binds DNA (14). In spite of this, human C-Ala, when fused to the editing domain of E. coli AlaRS, enhances its editing activity (12), suggesting that human C-Ala retains at least partial tRNA-binding activity. This might be true for all eukaryotic C-Ala domains, as the nematode C-Ala also retains tRNA-binding activity (Figures 3 and 4). It should be noted that like other eukaryotic C-Ala domains (39–41), human C-Ala folds into a monomer under reducing conditions, and the cysteine residues required for disulfide bridge formation (under oxidizing conditions) exist only in human C-Ala (14).

The nematode C-Ala is both a tRNA- and a DNA-binding domain

Previous studies showed that Ec-C-Ala binds the elbow of the L-shaped tRNAAla (12) but does not bind DNA (14). In contrast, dimeric human C-Ala binds DNA (14). We demonstrated that Ce-C-Ala robustly binds both DNA and tRNA (Figure 4). This domain binds different tRNAs, albeit with a distinct preference for tRNAAla (2.5–5.0-fold difference in the Kd values), but it does not bind an acceptor-stem microhelix to a discernible level (Figure 4). Consistent with this finding, fusion of Ce-C-Ala to CeAlaRSm selectively and distinctly enhances its aminoacylation activity toward the elbow-containing (or L-shaped) tRNAAla (Figure 3). Thus, like Ec-C-Ala, the Ce-C-Ala domain is an elbow-specific tRNA-binding domain. We also demonstrated that Ec-C-Ala exhibits a tRNA preference very similar to that of Ce-C-Ala (Figure 4), despite the low overall similarity between them. Ec-C-Ala is missing ∼34 amino acid residues in the helical subdomain (Supplementary Figure S1), with ∼34% identity in the remaining amino acid residues (14). The broad tRNA specificity of C-Ala might be attributed to the fact that the elbow of the L-shaped tRNA, formed by the D- and T-loops, is clustered with conserved invariant bases (42). In addition to the C-Ala domain of AlaRS, the C domain of LeuRS (43), the N domain of human LysRS (44) and two freestanding proteins, Trbp111 (45) and Arc1p (46), have also been shown to bind the elbow of the L-shaped tRNA.

Interestingly, Ce-C-Ala also robustly binds DNA, with an affinity almost equivalent to that of tRNAAla (Figure 4). To date, this is the only C-Ala domain known to possess high affinities (0.5–0.8 μM) to both DNA and tRNA. In contrast, Ec-C-Ala binds to DNA poorly (with a 10-fold lower affinity), while monomeric human C-Ala binds to tRNA poorly (with a 6-fold lower affinity) (Figure 4). Consistent with our finding, an earlier study showed that Ec-C-Ala fails to bind DNA cellulose to a significant level (14). Sequence and structural analyses revealed that all the amino acid residues that have been predicted to be involved in DNA binding by human C-Ala (such as R793, K812, R816, K820, K824, R831 and K846) are conserved in the helical subdomain of Ce-C-Ala, but not Ec-C-Ala (Supplementary Figure S1). It therefore appears that the helical subdomains of eukaryotic C-Ala domains have evolved DNA-binding activity. Paradoxically, the full-length human AlaRSc failed to bind DNA (14), while the full-length CeAlaRSc bound DNA with a Kd value of 1.5 μM (Supplementary Figure S11). An investigation is currently underway to find out whether Ce-C-Ala (or CeAlaRSc) plays a role in the nucleus. It is interesting to note in this regard that E. coli AlaRS binds to its own promoter in a site-specific manner to repress transcription (47).

The amino acid residues responsible for G3:U70 recognition diverge in CeAlaRSm

G3:U70, the universal identity element of tRNAAla found from E. coli to human cytoplasm, allows for the feasibility to perform cross-species and cross-compartmental rescue assays using a yeast ALA1 KO strain (4,30). This wobble base pair is recognized by two evolutionarily conserved amino acid residues—N and D—in the tRNA recognition domain (13). As a result, mutation at either of the two amino acid residues in the E. coli enzyme eliminates its aminoacylation activity. Surprisingly, a comparable mutation in human cytoplasmic AlaRS has little effect on its aminoacylation activity (20). Even more surprising was the finding that mitochondrial tRNAsAla in high eukaryotes, such as humans, mice, chickens, zebrafish and silkworms, lack the universal identity elements, as their AlaRSs lack the conserved N and D residues. Human mitochondrial AlaRS recognizes a short sequence—AGAU—in the variable loop, which is highly conserved in the abovementioned mitochondrial tRNAsAla (5). While CeAlaRSm still recognizes the canonical identity element G3:U70 (6), the conserved N and D residues responsible for recognition of this wobble base pair are diverged in this enzyme (Figure 1). It remains elusive as to how CeAlaRSm recognizes this wobble base pair.

AlaRS acquired (or lost) C-Ala to fit the new structure of its cognate tRNA

Except for the mitochondrial AlaRS in C. elegans (and its close relatives), all known AlaRSs possess an intact C-Ala domain (9). It is generally believed that the editing and C-Ala domains were acquired simultaneously, instead of successively, by an ancient AlaRS during evolution. An ancient freestanding editing factor, AlaXp-II, which possesses a sequence and function homologous to these two domains, was proposed to be fit for the purpose (12). Our phylogenetic analysis further indicated that the absence of most of the C-Ala domain from CeAlaRSm actually resulted from secondary loss of this domain (Figure 5). That is, CeAlaRSm used to possess a full-length C-Ala, but lost most of it later during evolution (Supplementary Figure S12). Upon deletion (or reduction) of C-Ala, this mitochondrial enzyme lost much of its capability to charge the elbow-containing tRNAAla while being readapted to a T-armless tRNAAla (or the other way around) (Supplementary Figure S12). Regardless of the detailed interpretation, our results highlight the functional diversity of a pre-existing appended domain. As prokaryotes evolved into eukaryotes, the C-Ala domain has been repurposed from tRNA binding to DNA binding, with Ce-C-Ala being an intermediate that robustly binds both ligands.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Titi Rindi Antika, Department of Life Sciences, National Central University, Zhongli District, Taoyuan 32001, Taiwan.

Dea Jolie Chrestella, Department of Life Sciences, National Central University, Zhongli District, Taoyuan 32001, Taiwan.

Indira Rizqita Ivanesthi, Department of Life Sciences, National Central University, Zhongli District, Taoyuan 32001, Taiwan.

Gita Riswana Nawung Rida, Department of Life Sciences, National Central University, Zhongli District, Taoyuan 32001, Taiwan.

Kuan-Yu Chen, Department of Life Sciences, National Central University, Zhongli District, Taoyuan 32001, Taiwan.

Fu-Guo Liu, Department of Life Sciences, National Central University, Zhongli District, Taoyuan 32001, Taiwan.

Yi-Chung Lee, Department of Neurology, Taipei Veterans General Hospital, Beitou District, Taipei 11217, Taiwan.

Yu-Wei Chen, Department of Neurology, Landseed International Hospital, Pingzhen District, Taoyuan 32449, Taiwan.

Yi-Kuan Tseng, Graduate Institute of Statistics, National Central University, Zhongli District, Taoyuan 32001, Taiwan.

Chien-Chia Wang, Department of Life Sciences, National Central University, Zhongli District, Taoyuan 32001, Taiwan.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan [109-2311-B-008-003]; Landseed Hospital [NCU-LSH-109-B-002]; Taipei Veterans General Hospital and University System of Taiwan Joint Research Program [108A1512-1]. Funding for open access charge: Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan [109-2311-B-008-001].

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Woese C.R., Olsen G.J., Ibba M., Söll D. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases, the genetic code, and the evolutionary process. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2000; 64:202–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Carter C.W. Jr Cognition, mechanism, and evolutionary relationships in aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1993; 62:715–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rubio Gomez M.A., Ibba M.. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. RNA. 2020; 26:910–936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chang C.P., Tseng Y.K., Ko C.Y., Wang C.C.. Alanyl-tRNA synthetase genes of Vanderwaltozyma polyspora arose from duplication of a dual-functional predecessor of mitochondrial origin. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012; 40:314–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kuhle B., Chihade J., Schimmel P.. Relaxed sequence constraints favor mutational freedom in idiosyncratic metazoan mitochondrial tRNAs. Nat. Commun. 2020; 11:969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chihade J.W., Hayashibara K., Shiba K., Schimmel P.. Strong selective pressure to use G:U to mark an RNA acceptor stem for alanine. Biochemistry. 1998; 37:9193–9202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lee Y.H., Lo Y.T., Chang C.P., Yeh C.S., Chang T.H., Chen Y.W., Tseng Y.K., Wang C.C.. Naturally occurring dual recognition of tRNAHis substrates with and without a universal identity element. RNA Biol. 2019; 16:1275–1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Natsoulis G., Hilger F., Fink G.R.. The HTS1 gene encodes both the cytoplasmic and mitochondrial histidine tRNA synthetases of S. cerevisiae. Cell. 1986; 46:235–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jasin M., Regan L., Schimmel P.. Modular arrangement of functional domains along the sequence of an aminoacyl tRNA synthetase. Nature. 1983; 306:441–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Naganuma M., Sekine S., Fukunaga R., Yokoyama S.. Unique protein architecture of alanyl-tRNA synthetase for aminoacylation, editing, and dimerization. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009; 106:8489–8494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lee J.W., Beebe K., Nangle L.A., Jang J., Longo-Guess C.M., Cook S.A., Davisson M.T., Sundberg J.P., Schimmel P., Ackerman S.L.. Editing-defective tRNA synthetase causes protein misfolding and neurodegeneration. Nature. 2006; 443:50–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Guo M., Chong Y.E., Beebe K., Shapiro R., Yang X.L., Schimmel P.. The C-Ala domain brings together editing and aminoacylation functions on one tRNA. Science. 2009; 325:744–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Naganuma M., Sekine S., Chong Y.E., Guo M., Yang X.L., Gamper H., Hou Y.M., Schimmel P., Yokoyama S.. The selective tRNA aminoacylation mechanism based on a single G·U pair. Nature. 2014; 510:507–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sun L., Song Y., Blocquel D., Yang X.L., Schimmel P.. Two crystal structures reveal design for repurposing the C-Ala domain of human AlaRS. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2016; 113:14300–14305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gowri V.S., Ghosh I., Sharma A., Madhubala R.. Unusual domain architecture of aminoacyl tRNA synthetases and their paralogs from Leishmania major. BMC Genomics. 2012; 13:621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Arutaki M., Kurihara R., Matsuoka T., Inami A., Tokunaga K., Ohno T., Takahashi H., Takano H., Ando T., Mutsuro-Aoki H.et al.. G:U-Independent RNA minihelix aminoacylation by Nanoarchaeum equitans alanyl-tRNA synthetase: an insight into the evolution of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. J. Mol. Evol. 2020; 88:501–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dock-Bregeon A.C., Garcia A., Giegé R., Moras D. The contacts of yeast tRNASer with seryl-tRNA synthetase studied by footprinting experiments. Eur. J. Biochem. 1990; 188:283–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Musier-Forsyth K., Usman N., Scaringe S., Doudna J., Green R., Schimmel P.. Specificity for aminoacylation of an RNA helix: an unpaired, exocyclic amino group in the minor groove. Science. 1991; 253:784–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hou Y.M., Schimmel P.. A simple structural feature is a major determinant of the identity of a transfer RNA. Nature. 1988; 333:140–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chong Y.E., Guo M., Yang X.L., Kuhle B., Naganuma M., Sekine S.I., Yokoyama S., Schimmel P.. Distinct ways of G:U recognition by conserved tRNA binding motifs. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2018; 115:7527–7532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. McClain W.H., Foss K.. Changing the identity of a tRNA by introducing a G–U wobble pair near the 3' acceptor end. Science. 1988; 240:793–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schimmel P., Giegé R., Moras D., Yokoyama S.. An operational RNA code for amino acids and possible relationship to genetic code. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1993; 90:8763–8768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lovato M.A., Chihade J.W., Schimmel P.. Translocation within the acceptor helix of a major tRNA identity determinant. EMBO J. 2001; 20:4846–4853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Okimoto R., Macfarlane J.L., Clary D.O., Wolstenholme D.R.. The mitochondrial genomes of two nematodes, Caenorhabditis elegans and Ascaris suum. Genetics. 1992; 130:471–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chang C.P., Lin G., Chen S.J., Chiu W.C., Chen W.H., Wang C.C.. Promoting the formation of an active synthetase/tRNA complex by a nonspecific tRNA-binding domain. J. Biol. Chem. 2008; 283:30699–30706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chang K.J., Lin G., Men L.C., Wang C.C.. Redundancy of non-AUG initiators. A clever mechanism to enhance the efficiency of translation in yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 2006; 281:7775–7783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hellman L.M., Fried M.G.. Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) for detecting protein–nucleic acid interactions. Nat. Protoc. 2007; 2:1849–1861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chien C.I., Chen Y.W., Wu Y.H., Chang C.Y., Wang T.L., Wang C.C.. Functional substitution of a eukaryotic glycyl-tRNA synthetase with an evolutionarily unrelated bacterial cognate enzyme. PLoS One. 2014; 9:e94659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chang K.J., Wang C.C.. Translation initiation from a naturally occurring non-AUG codon in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 2004; 279:13778–13785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tang H.L., Yeh L.S., Chen N.K., Ripmaster T., Schimmel P., Wang C.C.. Translation of a yeast mitochondrial tRNA synthetase initiated at redundant non-AUG codons. J. Biol. Chem. 2004; 279:49656–49663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fersht A.R., Ashford J.S., Bruton C.J., Jakes R., Koch G.L., Hartley B.S.. Active site titration and aminoacyl adenylate binding stoichiometry of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. Biochemistry. 1975; 14:1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chang C.Y., Chien C.I., Chang C.P., Lin B.C., Wang C.C.. A WHEP domain regulates the dynamic structure and activity of Caenorhabditis elegans glycyl-tRNA synthetase. J. Biol. Chem. 2016; 291:16567–16575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Levi O., Arava Y.. mRNA association by aminoacyl tRNA synthetase occurs at a putative anticodon mimic and autoregulates translation in response to tRNA levels. PLoS Biol. 2019; 17:e3000274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Huang H.Y., Kuei Y., Chao H.Y., Chen S.J., Yeh L.S., Wang C.C.. Cross-species and cross-compartmental aminoacylation of isoaccepting tRNAs by a class II tRNA synthetase. J. Biol. Chem. 2006; 281:31430–31439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zhang H., Wu J., Lyu Z., Ling J.. Impact of alanyl-tRNA synthetase editing deficiency in yeast. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021; 49:9953–9964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jones D.T., Taylor W.R., Thornton J.M.. The rapid generation of mutation data matrices from protein sequences. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 1992; 8:275–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kumar S., Stecher G., Li M., Knyaz C., Tamura K.. MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018; 35:1547–1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fukunaga R., Yokoyama S.. Crystallization and preliminary X-ray crystallographic study of alanyl-tRNA synthetase from the archaeon Archaeoglobus fulgidus. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F: Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 2007; 63:224–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Dignam J.D., Dignam S.S., Brumley L.L.. Alanyl-tRNA synthetase from Escherichia coli, Bombyx mori and Ratus ratus. Existence of common structural features. Eur. J. Biochem. 1991; 198:201–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Shiba K., Ripmaster T., Suzuki N., Nichols R., Plotz P., Noda T., Schimmel P.. Human alanyl-tRNA synthetase: conservation in evolution of catalytic core and microhelix recognition. Biochemistry. 1995; 34:10340–10349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zeng Q.Y., Peng G.X., Li G., Zhou J.B., Zheng W.Q., Xue M.Q., Wang E.D., Zhou X.L.. The G3-U70-independent tRNA recognition by human mitochondrial alanyl-tRNA synthetase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019; 47:3072–3085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lorenz C., Lünse C.E., Mörl M.. tRNA modifications: impact on structure and thermal adaptation. Biomolecules. 2017; 7:35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Palencia A., Crépin T., Vu M.T., Lincecum T.L. Jr, Martinis S.A., Cusack S. Structural dynamics of the aminoacylation and proofreading functional cycle of bacterial leucyl-tRNA synthetase. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2012; 19:677–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Francin M., Kaminska M., Kerjan P., Mirande M.. The N-terminal domain of mammalian lysyl-tRNA synthetase is a functional tRNA-binding domain. J. Biol. Chem. 2002; 277:1762–1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Morales A.J., Swairjo M.A., Schimmel P.. Structure-specific tRNA-binding protein from the extreme thermophile Aquifex aeolicus. EMBO J. 1999; 18:3475–3483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Simos G., Segref A., Fasiolo F., Hellmuth K., Shevchenko A., Mann M., Hurt E.C.. The yeast protein Arc1p binds to tRNA and functions as a cofactor for the methionyl- and glutamyl-tRNA synthetases. EMBO J. 1996; 15:5437–5448. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Putney S.D., Schimmel P.. An aminoacyl tRNA synthetase binds to a specific DNA sequence and regulates its gene transcription. Nature. 1981; 291:632–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.