Abstract

N 6-Threonylcarbamoyladenosine (t6A) is a universal and pivotal tRNA modification. KEOPS in eukaryotes participates in its biogenesis, whose mutations are connected with Galloway-Mowat syndrome. However, the tRNA substrate selection mechanism by KEOPS and t6A modification function in mammalian cells remain unclear. Here, we confirmed that all ANN-decoding human cytoplasmic tRNAs harbor a t6A moiety. Using t6A modification systems from various eukaryotes, we proposed the possible coevolution of position 33 of initiator tRNAMet and modification enzymes. The role of the universal CCA end in t6A biogenesis varied among species. However, all KEOPSs critically depended on C32 and two base pairs in the D-stem. Knockdown of the catalytic subunit OSGEP in HEK293T cells had no effect on the steady-state abundance of cytoplasmic tRNAs but selectively inhibited tRNAIle aminoacylation. Combined with in vitro aminoacylation assays, we revealed that t6A functions as a tRNAIle isoacceptor-specific positive determinant for human cytoplasmic isoleucyl-tRNA synthetase (IARS1). t6A deficiency had divergent effects on decoding efficiency at ANN codons and promoted +1 frameshifting. Altogether, our results shed light on the tRNA recognition mechanism, revealing both commonality and diversity in substrate recognition by eukaryotic KEOPSs, and elucidated the critical role of t6A in tRNAIle aminoacylation and codon decoding in human cells.

INTRODUCTION

tRNAs are the most heavily modified RNA species in the cell, considering localizations of modified positions and modification diversity. tRNA modification plays critical functions in genome decoding by either guaranteeing the unique structure and stability of tRNA architectures or regulating translation fidelity and efficiency during ribosomal decoding (1,2).

Among all positions of a given tRNA molecule, those in the anticodon loop, in particular positions 34 and 37, are the most extensively modified due to their critical roles in codon-anticodon base pairing strength and accuracy (3,4). N6-Threonylcarbamoyladenosine (t6A) is a modified nucleotide found exclusively at position 37 adjacent to the anticodon in ANN-decoding tRNAs across all three domains of life (5,6). Enzymes for t6A biogenesis have been studied in bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes and in organelles. t6A modification occurs in two consecutive steps: YRDC/Sua5 family proteins catalyze the formation of the L-threonylcarbamoyladenylate intermediate (TC-AMP) from threonine, bicarbonate and ATP (7), and subsequently, TsaD/Kae1/Qri7 family proteins transfer the L-threonylcarbamoyl moiety of the TC-AMP intermediate to A37 (8–13). Despite the conservation of catalytic subunits, the components of t6A modification machinery, specifically that performing the second step, differ significantly among various species/organelles. In bacteria, TsaC (in the YRDC/Sua5 family), TsaD, TsaB and TsaE jointly mediate t6A biogenesis (10), while in archaea and eukaryotic cytoplasm, YRDC/Sua5 and a four- or five-subunit KEOPS (Kinase, Endopeptidase, and Other Proteins of Small size) complex cooperatively generate t6A (11,12,14). Eukaryotic mitochondria seemingly use the minimalistic enzymes Sua5 and Qri7 in yeast or YRDC and OSGEPL1 in mammals (15–17) (Supplementary Table S1). In the KEOPS complex, Gon7 (GON7), Pcc1 (LAGE3), Kae1 (OSGEP), Bud32 (TP53RK) and Cgi121 (TPRKB) are arranged linearly (14,18). In addition to the catalytic subunit Kae1 (OSGEP), Bud32 (TP53RK) is an ATPase that catalyzes the hydrolysis of ATP to ADP and Pi (19); however, the exact role of this subunit in t6A biogenesis remains unclear. Furthermore, the function of both Gon7 (GON7) and Pcc1 (LAGE3) remains unknown (5). TsaC has been reported to interact with the TsaD-TsaB-TsaE complex (10); however, Sua5/YRDC seems to be independent of the KEOPS complex in the cytoplasm or of OSGEPL1 in mitochondria (15,19).

Substrate selection and binding during the second step have long been unknown. Only recently the binding mode of TC-AMP analog by bacterial TsaD-TsaB has been clarified (20). However, only limited reports have described tRNA recognition by t6A modification enzymes, in part owing to difficulties in reconstituting t6A modification activity in vitro in earlier studies. Based on a Xenopus laevis oocyte in vivo modification system, only U36 was absolutely required for effective t6A modification (21). Our two recent works have revealed that (C/A>U>G)32-N33-(U/G>A)34-N35-U36-A37-A38 was the nucleotide sequence requirements in the anticodon loop for human mitochondrial tRNAThr to be efficiently modified by Sua5-Qri7 (22) or YRDC-OSGEPL1, and Lys203 in OSGEPL1 seems to be a critical tRNA-binding element (15). Our initial finding of A38 being a critical element has been confirmed by others (17). Using the archaeal KEOPS complex as a model, it has been recently found that Cgi121 in an archaeal KEOPS complex (human TPRKB homolog) binds the CCA terminus of substrate tRNAs and that this interaction is essential for t6A biogenesis by the archaeal KEOPS complex (18).

t6A modification in bacteria and yeast stabilizes the anticodon loop architecture by preventing intraloop interactions, facilitates codon-anticodon pairing by mediating base-stacking interactions at the ribosomal decoding site to prevent +1 frameshifting and promotes downstream modification at other sites (6,23). In addition, reduced tRNAIle aminoacylation levels by isoleucyl-tRNA synthetase (IleRS) have been observed in Escherichia coli cells lacking the TsaC or TsaD gene (24). However, yeast IleRS does not use the t6A moiety as a positive determinant in tRNA charging (12,24). These observations likely explain why the t6A modification apparatus is essential in some bacteria but not in yeast. In mammalian cells, knockdown of OSGEP or TP53RK leads to impaired protein synthesis, endoplasmic reticulum stress, signaling in response to DNA damage, and apoptosis (25). Owing to the pivotal role of t6A modification in mRNA translation and protein homeostasis, it is not surprising that deletions or mutations in t6A modification enzymes in yeast or in humans lead to cellular dysfunctions and disorders in humans (25,26). Yeast cells in which the Sua5 gene is deleted exhibit delayed growth and sensitivity to various stresses, including heat, ethanol and salt (27). Deletion of the Kae1 gene in yeast also causes severe growth retardation (16). Several independent studies have shown that genetic mutations in each gene of the human t6A biogenesis pathway (YRDC, OSGEP, TP53RK, TPRKB, GON7 and LAGE3) cause severe effects associated with Galloway–Mowat syndrome (GAMOS), characterized by the combination of early onset nephrotic syndrome and microcephaly with brain anomalies (25,28). Effects of OSGEP mutations on other phenotypes, such as neurodegeneration, have also been observed (29). Despite obvious advances in the mechanism and significance of t6A in bacteria, yeast and archaea, however, in mammalian cells, the basic understanding of the molecular mechanism of t6A biogenesis, including tRNA selection and recognition by the eukaryotic cytoplasmic KEOPS complex, the potential contribution of t6A modification to tRNA abundance and the aminoacylation level of ANN-decoding tRNAs, codon-anticodon decoding, and +1 frameshifting restriction, has thus far been very limited.

In the present work, using several KEOPS complexes and bacterial, yeast and human tRNAs, we clarified how eukaryotic KEOPS complexes select tRNA substrates, highlighting the critical role of the anticodon loop and two base pairs in the D-stem in determining the t6A modification level. Furthermore, we revealed the important or determinative role of t6A modification in tRNA aminoacylation and in preventing +1 frameshifting. Our results help to understand the basic knowledge of the t6A modification mechanism and function in human cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Anti-FLAG (F7425) and horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies were purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). Anti-GAPDH (60004-1-Ig) and anti-OSGEP (15033-1-AP) antibodies were purchased from Proteintech (Wuhan, China). Anti-TP53RK (A14952) antibody was purchased from ABclonal Technology Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China). [14C]Thr was obtained from American Radiolabeled Chemicals, Inc. (St. Louis, MO, USA), and [3H]Ile was obtained from PerkinElmer, Inc. (Hopkinton, MA, USA). KOD-plus mutagenesis kits were obtained from TOYOBO (Osaka, Japan). Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent, puromycin and SuperSignal West were obtained from Thermo Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). Anti-digoxigenin-AP (11093274910), 10% blocking reagent (11096176001) and CDP-Star were purchased from Roche (Basel, Switzerland). 50× Denhardt solution (B548209-0050), 20× saline sodium citrate (SSC) (B548109) and fish sperm DNA (B548210) were purchased from Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Primer synthesis, biotin- or digoxin-DNA probe synthesis and DNA sequencing were performed by Tsingke Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China) and Biosune (Shanghai, China).

Plasmid construction, mutagenesis and gene expression

Genes encoding human KEOPS (hKEOPS) subunits OSGEP (UniProt No. Q9NPF4), TP53RK (UniProt No. Q96S44), TPRKB (UniProt No. Q9Y3C4), LAGE3 (UniProt No. Q14657) and GON7 (UniProt No. Q9BXV9) were amplified from cDNA obtained by reverse transcription of total RNA from human HEK293T cells. Ribosomal recognition sites (RBSs) were inserted between two adjacent coding genes into a pJ241 vector (30) with a His6-tag at its C-terminus via a Seamless Cloning Kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China). The resulting polycistronic plasmid pJ241-hKEOPS expressed five recombinant proteins, OSGEP, TP53RK, TPRKB, LAGE3 and GON7-His6, under the control of the T7 promoter. Escherichia coli codon-optimized DNA encoding Caenorhabditis elegans PCC1 (F59A2.5), KAE1 (Y71H2AM.1) plus a His6-tag at the C-terminus, BUD32 (F52C12.6), CGI121 (W03F8.4) (GON7 homolog in C. elegans not yet identified) and a ribosomal binding site sequence between two adjacent genes was chemically synthesized and inserted into a pET24a vector between NdeI and XhoI sites. The resulting polycistronic plasmid pET24a-CeKEOPS (C. elegans KEOPS) expressed four recombinant proteins, PCC1, KAE1-His6, BUD32 and CGI121, under the control of the T7 promoter (8). The plasmid encoding Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Sc) KEOPS (pJ241-ScKEOPS) expressed five recombinant proteins, KAE1, BUD32, CGI121, PCC1 and GON7-His6, under the control of the T7 promoter (30). Human YRDC (hYRDC) and yeast Sua5 expression plasmids were constructed as reported previously (15,22). The construction of expression plasmids for E. coli TsaC (UniProt No. P45748), TsaD (UniProt No. P05852) and TsaB (UniProt No. P76256) was as described in a previous report (31). The gene encoding E. coli TsaE (UniProt No. P0AF67) was subcloned from pET28a-yjeE into a pET21a vector via NdeI and XhoI, yielding a pET21a-TsaE expression plasmid in which a His6 tag is introduced at the C-terminus (31). The gene encoding truncated human cytoplasmic isoleucyl-tRNA synthetase (hIleRS) (Met1-Ser1073) (UniProt No. P41252) was obtained by amplifying the cDNA obtained by reverse transcription of the total RNA of human HEK293T cells and inserted into a pJ241 vector with a His6-tag at its C-terminus by a Seamless Cloning Kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China). The OSGEP gene was inserted between the EcoRI and HindIII sites of pCMV-3Tag-3A and the HindIII and EcoRI sites of pEGFP-N2. Similarly, TP53RK was inserted between the HindIII and XhoI sites of pCMV-3Tag-3A and the HindIII and BamHI sites of pEGFP-N2 and TPRKB was inserted between the XhoI and HindIII sites of pEGFP-N2. GON7 was inserted between the HindIII and BamHI sites of pEGFP-N2, and LAGE3 was inserted between the HindIII and EcoRI sites of pEGFP-N2.

All the primers used for cloning were listed in Supplementary Table S2. Gene mutations were obtained through KOD-plus mutagenesis kits (TOYOBO, Osaka, Japan) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Gene expression vectors were expressed in E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells. The genes encoding hYRDC and Sua5 were expressed as described in a previous report (15). The overexpression of the hKEOPS complex and ScKEOPS was carried out when the initial cell culture reached an absorbance at 600 nm (A600) of 0.6–0.8, isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added at a final concentration of 0.5 mM, and the cells were induced overnight at 16°C. CeKEOPS gene expression was induced with 200 μM IPTG, and transformants were cultured for 3–5 h at 37°C. Expression of the hIleRS (Met1-Ser1073) gene was induced with 50 μM IPTG overnight at 18°C. Protein purification was initially performed according to a previously described method (32). After initial purification via Ni-NTA affinity chromatography, hKEOPS, hYRDC and CeKEOPS were further purified by gel filtration on a Superdex S200 column with 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) and 150 mM NaCl at the rate of 0.5 ml/min. ScKEOPS and hIleRS (Met1-Ser1073) were further purified via ion exchange chromatography (Mono Q column), which was first pre-equilibrated with buffer A (containing 25 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.8), 50 mM NaCl and 1 mM DTT). The proteins were eluted by a linear gradient from buffer A to buffer B (containing 25 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.8), 1 M NaCl and 1 mM DTT) at the rate of 1.0 ml/min. Fractions containing ScKEOPS and hIleRS protein were concentrated in 30 kDa molecular mass cut-off Amicon. The protein concentration was determined via a Protein Quantification Kit (Beyotime) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

tRNA gene cloning and transcription

Genes encoding human cytoplasmic (hc) tRNAThr(AGU, CGU, UGU), tRNASer(GCU), tRNAArg(CCU, UCU), tRNAAsn(GUU), tRNAMet(e), initiator tRNAMet (tRNAMet(i)), tRNALys(UUU), tRNALys(CUU), tRNAIle(AAU), tRNAIle(UAU), tRNAIle(GAU), E. coli (Ec) tRNAMet(i) and S. cerevisiae (Sc) tRNAMet(i) were incorporated into a pTrc99b plasmid. tRNA transcripts were obtained by in vitro T7 RNA polymerase transcription as described previously (33,34). The primers used for template preparation were listed in Supplementary Table S2.

Determination of in vitro t6A modification and aminoacylation activities

The t6A modification reaction was performed at 37°C in a 40 μl reaction mixture containing 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0), 200 mM NaCl, 15 mM MgCl2, 5 mM MnCl2, 50 mM NaHCO3, 5 mM DTT, 4 mM ATP, 100 μM [14C]Thr, 10 μM transcribed hctRNAs (or its variants) and 2 μM Sua5 and ScKEOPS or hYRDC and hKEOPS or hYRDC and CeKEOPS. The aminoacylation reaction was performed at 37°C in a 40 μl reaction mixture containing 60 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 5 mM DTT, 4 mM ATP, 20 μM [3H]Ile, and 5 μM t6A unmodified or modified hctRNAIle (AAU) or hctRNAIle (UAU) or hctRNAIle (GAU) transcript and 1 μM hIleRS (Met1-Ser1073). Aliquots (9 μl) of the reaction solution were added to filter pads at various time points and quenched with cold 5% TCA. The pads were washed three times for 15 min each with cold 5% TCA and then three times for 10 min each with 100% ethanol. Finally, the pads were dried under a heat lamp, and the radioactivity of the precipitates was quantified using a scintillation counter (Beckman Coulter, Atlanta, GA, USA).

Melting temperature (Tm) assays of tRNAs

The specific tRNA was dissolved in a buffer containing 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), 10 μM EDTA and 100 mM NaCl. The initial absorbance of the tRNA at 260 nm was diluted to between 0.2 and 0.3. The melting temperature curve was determined at 260 nm using an Agilent Cary 100 spectrophotometer at a heating rate of 1°C per minute from 25°C to 95°C.

Cell culture, transfection, nucleocytoplasmic separation and immunofluorescence assays

HEK293T cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum in a 37°C incubator with 5% CO2. Transfection was performed using Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent. At 24 h after transfection, the cells were harvested and washed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) three times. Nucleocytoplasmic separation was performed by a Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Protein Extraction Kit (P0027, Beyotime) according to the manufacturer's protocol. For immunofluorescence assays, the cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min and then permeated in 0.2% Triton X-100 for 10 min at RT. After washing with PBS, the fixed cells were blocked in PBS containing 4% BSA and then incubated with rabbit anti-OSGEP or anti-TP53RK antibodies at a 1:200 dilution overnight at 4°C. The cells were then immunolabeled with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG in PBS at a 1:1000 dilution for 2 h and the nuclear counterstain DAPI for 5 min at RT. Fluorescent images were taken and analyzed using a Leica TCS SP8 STED confocal microscope (Leica).

Construction of OSGEP knockdown (KD) cell lines

shRNA sequences (Supplementary Table S3) were inserted into the lentiviral vector pLKO.1 between AgeI and EcoRI sites. The lentiviral vectors were cotransfected with the packaging vector pCMVDR8.9 and enveloped vector pCMV-VSVG into HEK293T cells using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent for lentivirus production. After 48 h, viruses were collected for 48 h of infection of HEK293T cells. Stably infected cells were selected via puromycin (2.5 μg/ml) for 48 h. Finally, the surviving cells were identified by western blotting using anti-OSGEP antibody.

Dual-luciferase reporter assays

6× ANN codons were inserted into a pmirGLO plasmid after the firefly luciferase (F-luc) gene ATG start codon. For the frameshifting assay, a specific nucleotide (see the RESULTS section) was inserted at a specific codon of the F-luc gene. Subsequently, the plasmids were transfected into WT and OSGEP KD cells in a 24-well plate using Lipofectamine 2000. After cultivating 24 h, the cells were harvested and assayed by a Dual-Glo Luciferase Assay System (Promega). Renilla luciferase (R-luc) was used to normalize F-Luc activity to evaluate the translation efficiency of the reporter.

tRNA isolation and ultra-performance liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry/mass spectrometry (UPLC–MS/MS) analysis

Total RNA was extracted from WT and KD cells using TRIzol reagent. The fourteen endogenous ANN-decoding tRNAs and two other tRNAs (tRNALeu(CAA) and tRNASer(CGA)) were isolated from total RNAs using tRNA fishing by their own solid-phage complementary biotinylated DNA probes (Supplementary Table S4) using streptavidin agarose resin (20361, Thermo Scientific). The biotinylated DNA probes were designed to complement the 5′ or 3′ sequences of the tRNAs. In brief, the specific biotinylated DNA probes were incubated with total RNA at 65°C for approximately 1.5 h in annealing buffer (1.2 M NaCl, 30 mM HEPES–KOH (pH 7.5), 15 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM DTT). Streptavidin agarose beads were then added to the mixture, which was subsequently incubated for 30 min at 65°C. After binding, the agarose beads were washed three times with washing buffer (0.1 M NaCl, 2.5 mM HEPES–KOH (pH 7.5), 1.25 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM DTT). tRNAs on the agarose beads were extracted using TRIzol reagent and precipitated by ethanol. Purified tRNAs were identified via 8 M urea polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

Before subjected to UPLC–MS/MS, 500 ng of tRNA transcripts or specific endogenous tRNAs were digested with 1 μl of nuclease P1, 0.2 μl of benzonase, 0.5 μl of phosphodiesterase I, and 0.5 μl of bacterial alkaline phosphatase in a 20 μl solution including 4 mM NH4OAc (pH 5.2) at 37°C overnight. After complete hydrolysis, 1 μl of the solution of products was subjected to UPLC–MS/MS.

Western blotting

Cells were lysed using RIPA (Radio Immunoprecipitation Assay) buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS) and proteins separated on a 10% separating gel via SDS-PAGE. Western blotting was performed as described in a previous report (35).

Northern blotting

For tRNA abundance determination, 3 μg of total RNA was loaded on a 10% polyacrylamide–8 M urea gel in Tris-borate EDTA (TBE) buffer at RT under 150 V for 1.5 h. For the aminoacylation assays, 5 μg of total RNA dissolved in 0.1 M NaAc (pH 5.2) was electrophoresed through an acidic (0.1 M NaAc (pH 5.2)) 10% polyacrylamide 8 M urea gel at 4°C under 18 W for 16 h. The RNAs were then transferred onto a positively charged nylon membrane (Merck) at 4°C under 250 mA for 40 min. After UV crosslinking (8000 × 100 J/cm2), the membrane was preblocked with prehybridization solution (4 × SSC (containing 0.6 M NaCl and 0.06 M Na-Citrate), 20 mMNa2HPO4, 7% SDS, 1.5× Denhardt solution, 0.4 mg/l fish sperm DNA) at 55°C for 1 h. The membrane was subsequently hybridized with digoxin (DIG)-labeled probes (Supplementary Table S4) for specific tRNAs and 5S rRNA at 55°C overnight. The membrane was then washed with 2 × SSC buffer (containing 0.1% SDS) followed by washing buffer (0.1 M maleic acid and 0.15 M NaCl (pH 7.5)) twice for 5 min and then blocked with 1× blocking reagent (0.1 M maleic acid, 0.15 M NaCl, 1% blocking reagent (pH 7.5)) for 30 min at RT. Then, the membrane was incubated with anti-digoxigenin-AP buffer (1× blocking reagent, 1:10 000 anti-digoxigenin-AP) for 1 h and washed twice every 10 min. Finally, the membrane was treated with CDP-Star and imaged via an Amersham Imager 680 system (GE, CA, USA).

RESULTS

All ANN-decoding tRNAs in human cells contain t6A modification

The human genome encodes >400 high-confidence tRNA genes (2); however, the modification atlas of full sets of human cytoplasmic tRNAs has not been fully established. In the human cytoplasm, ANN codons encode seven amino acids: Arg, Asn, Ile, Lys, Met, Ser and Thr. Accordingly, fourteen ANN-decoding tRNA isoacceptors, i.e., tRNAThr(AGU, CGU, UGU), tRNAIle(AAU, UAU, GAU), tRNASer(GCU), tRNALys(CUU, UUU), tRNAArg(CCU, UCU), initiator tRNAMet (tRNAMet(i)), elongator tRNAMet (tRNAMet(e)) and tRNAAsn(GUU), were found to be potential modification substrates for the hKEOPS. Thus far, some ANN-decoding tRNAs such as tRNAMet(i) (36), tRNAMet(e) (37) and tRNALys(UUU) (38) have been experimentally demonstrated to contain t6A moieties. To understand whether all the above tRNA isoacceptors harbor t6A modifications, we purified all these tRNA species from HEK293T cells via tRNA fishing in conjunction with a solid-phase complementary biotinylated DNA probe (Supplementary Figure S1A and B; Supplementary Table S4). UPLC-MS/MS confirmed that all fourteen ANN-decoding tRNAs harbored t6A modifications (Supplementary Figure S1C). Because the non-ANN-decoding tRNA samples, including tRNALeu(CAA) and tRNASer(CGA), showed little evidence of t6A (Supplementary Figure S1C), suggesting that samples were not cross-contaminated with other tRNA species. Thus, the above results showed that the hKEOPS was able to introduce t6A modifications to all ANN-decoding tRNAs.

C33 acts as an anti-determinant in t6A biogenesis by the yeast modifying machinery but not the human or nematode

To understand the molecular mechanism of t6A biogenesis by the hKEOPS complex, we cloned the open reading frames (ORFs) of all five human genes (OSGEP, TP53RK, TPRKB, LAGE3, GON7) into the bacterial expression vector pJ241 (pJ241-hKEOPS), with each ORF having an independent ribosome-binding site (RBS) and start and stop codons, in a polycistronic gene organization, as was done for expression vector construction with respect to ScKEOPS (30). Because all human ANN-decoding tRNAs harbored t6A modifications in vivo, we also constructed all the necessary tRNA clones and obtained all fourteen tRNA transcripts via T7 in vitro transcription.

We overexpressed pJ241-hKEOPS in bacteria; however, in our system, the integrity of the hKEOPS complex was always disrupted (disassociation of GON7) during the subsequent purification step (size exclusion or ion exchange chromatography) following His-tag affinity chromatography (Supplementary Figure S2A). In contrast, the ScKEOPS complex was well expressed and purified with an intact composition with all subunits, as shown in a previous report (Supplementary Figure S2B) (30). Indeed, the t6A synthesis activity of the purified stoichiometrically inhomogeneous hKEOPS was much lower than that of ScKEOPS under the same conditions (Supplementary Figure S2C). Based on the homogeneity, purity and activity, we preferentially used the ScKEOPS complex as a eukaryotic KEOPS model to modify human cytoplasmic tRNAs to understand tRNA recognition and selection mechanism. We understand some limitations of modifying human tRNAs using a yeast complex; therefore, for modifying some key tRNA mutants, hKEOPS was also used for comparison. Furthermore, KEOPS from another multicellular organism, C. elegans (CeKEOPS), was also cloned and purified (Supplementary Figure S2D). Fortunately, such a combination in determining the activity (modification of the same set of human tRNAs by different KEOPS complexes) provided some unexpected insights, which revealed both similarity and some undetected striking differences between KEOPS complexes from yeasts, humans and nematodes (see below).

We found that all fourteen human tRNAs (except tRNAMet(i)) were effectively modified by ScKEOPS, despite varying modification levels (Supplementary Figure S3). tRNAThr(UGU), tRNALys(CUU), tRNAArg(UCU) and tRNASer(GCU) were among the best substrates (Supplementary Table S5). The inability (or inefficiency) of tRNAMet(i) modification by ScKEOPS was unanticipated and puzzling because it readily harbored a t6A modification based on our UPLC–MS/MS data (albeit with the lowest detection scale among fourteen ANN-decoding tRNAs) (Supplementary Figure S1C) and previous data obtained by others (36).

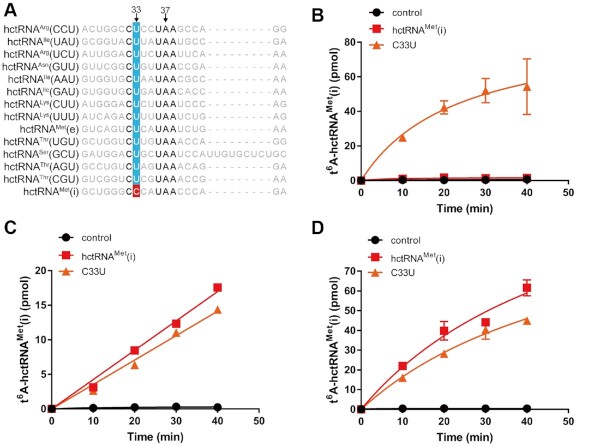

We then compared the tRNAMet(i) sequence with thirteen other tRNA sequences, especially the anticodon sequence, which is in proximity to the modification site A37. Indeed, we noticed that only tRNAMet(i) contains C33, which is otherwise U33 in other tRNAs (Figure 1A), suggesting that C33 is a potential anti-determinant for t6A modification by ScKEOPS. To explore this possibility, C33 of tRNAMet(i) was mutated to U33. The modification assay indeed showed robust modification of tRNAMet(i)-C33U by ScKEOPS (Figure 1B). Therefore, these data suggested that C33 prevents tRNAMet(i) from being efficiently modified by ScKEOPS.

Figure 1.

C33 is an anti-determinant for t6A biogenesis in yeast but not humans or nematodes. (A) Sequence alignment of anticodon stem and loop regions of 14 ANN-decoding hctRNAs. hctRNAMet(i) contains C33, while the other tRNAs contain U33. Absolute conserved nucleotides are shown in bold. Time course curves of the t6A modification of hctRNAMet(i) (red filled squares) and hctRNAMet(i)-C33U (orange filled triangles) by Sua5 and ScKEOPS (B); by hYRDC and hKEOPS (C) or by hYRDC and CeKEOPS (D). The controls (black filled circles) represent assays in which no tRNAs were added. The data represent the averages of three independent experiments and the corresponding standard deviations. The error bars were masked by the symbols in (C).

Considering that tRNAMet(i) harbors t6A modification in vivo, it also implies that C33 is no longer an anti-determinant for hKEOPS. To answer this question, both tRNAMet(i) and tRNAMet(i)-C33U were modified by hKEOPS. In contrast to ScKEOPS, hKEOPS introduced t6A modifications to both tRNAs with similar efficiency (Figure 1C). Moreover, comparable t6A modifications of tRNAMet(i) and tRNAMet(i)-C33U were observed using CeKEOPS, with a higher efficiency (Figure 1D).

Above all, these data suggested that C33 functions as an anti-determinant in t6A biogenesis by the yeast modifying machinery but not the human or nematode.

Possible coevolution of position 33 of tRNAMet(i) and the t6A modification machinery

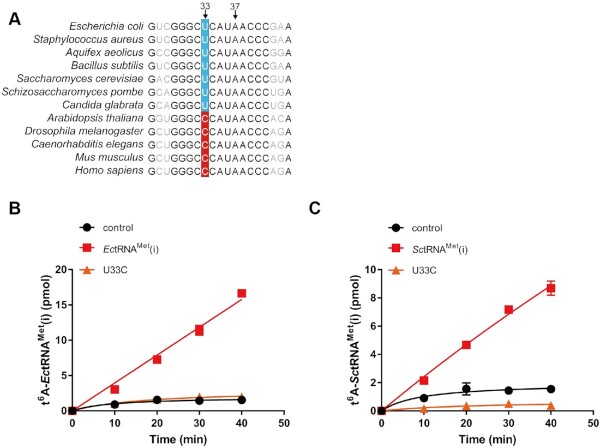

We further checked position 33 of tRNAMet(i) from other species in addition to humans, including representative model species. Interestingly, those from either prokaryotes (e.g. E. coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Aquifex aeolicus, Bacillus subtilis) or single-cellular organisms (e.g. S. cerevisiae, Schizosaccharomyces pombe, Candida glabrata) contain U33, while those from multicellular organisms (e.g. humans, mice, C. elegans, Drosophila melanogaster and even Arabidopsis thaliana) all contain C33 (Figure 2A) (39). Considering that the hKEOPS and CeKEOPS complexes but not the ScKEOPS complex could modify human tRNAMet(i) with C33, these observations raise the question of whether the t6A modification apparatus from species with U33-containing tRNAMet(i) uses C33 as an anti-determinant.

Figure 2.

Possible coevolution of position 33 of the initiator tRNAMet and the t6A modification machinery. (A) Sequence alignment of anticodon stem and loop regions of tRNAMet(i) from different species. Absolute conserved nucleotides are shown in bold. Time course curves of the t6A modification of EctRNAMet(i) (red filled squares) and EctRNAMet(i)-U33C (orange filled triangles) by EcTsaBCDE (B) and of SctRNAMet(i) (red filled squares) and SctRNAMet(i)-U33C (orange filled triangles) by Sua5 and ScKEOPS (C). The controls (black filled circles) represent assays in which no tRNAs were added. The data represent the averages of three independent experiments and the corresponding standard deviations. The error bars were masked by the symbols in (B).

To explore this possibility, we cloned four genes (encoding TsaC, TsaB, TsaD and TsaE) of E. coli t6A modification enzymes and purified individual subunit from E. coli expression system (Supplementary Figure S4). Using E. coli tRNAMet(i) (EctRNAMet(i)), t6A modification activity was reconstituted using four E. coli proteins (designated EcTsaBCDE). We found that after mutation of U33 to C33 in EctRNAMet(i), EcTsaBCDE was indeed unable to modify EctRNAMet(i)-U33C (Figure 2B). Furthermore, we also transcribed S. cerevisiae tRNAMet(i) (SctRNAMet(i)) and the SctRNAMet(i)-U33C mutant. Consistently, the ScKEOPS complex modified SctRNAMet(i) with a t6A moiety but not SctRNAMet(i)-U33C (Figure 2C).

In combination with modification capacities of U33- and C33-containing homogeneous and/or heterogeneous tRNAMet(i) by four t6A modification complexes (EcTsaBCDE, ScKEOPS, hKEOPS and CeKEOPS), we proposed that coevolution of position 33 of tRNAMet(i) and t6A modification apparatuses likely occurred; that is, bacteria and yeast (with U33-containing tRNAMet(i)) t6A modification enzymes employed C33 as an anti-determinant, while those from higher eukaryotes (with C33-containing tRNAMet(i)), including humans and nematodes, displayed a relaxed specificity for position 33.

C32 is absolutely required for t6A modification by various KEOPS complexes

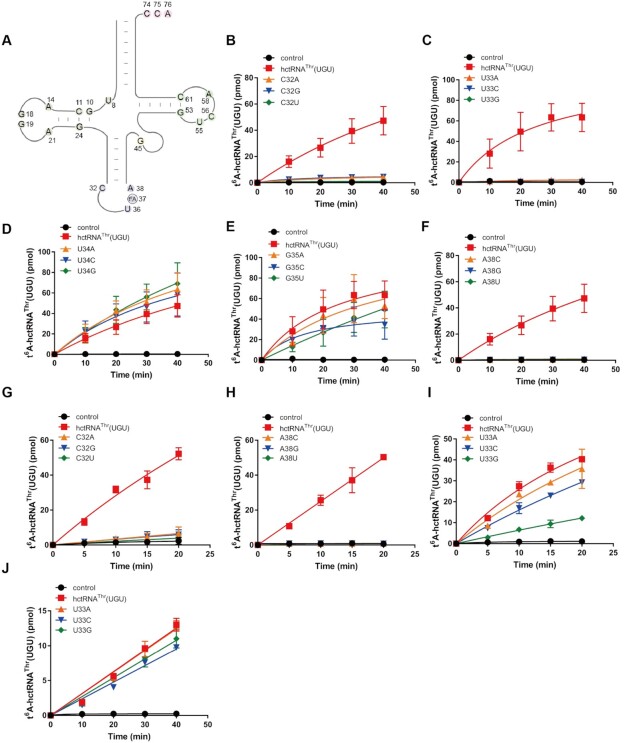

Subsequently, we compared all fourteen ANN-decoding tRNAs in the context of their cloverleaf structure. The consensus positions were mainly located in four regions: the anticodon loop, D-arm, TψC-arm and CCA terminus (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

C32 is absolutely required for t6A modification by various KEOPS complexes. (A) Secondary structure showing conserved nucleotides of 14 ANN-decoding hctRNAs. Time course curves of the t6A modification of hctRNAThr(UGU) (red filled squares) together with hctRNAThr(UGU)-C32A (orange filled triangles), -C32G (blue filled inverted triangles) and -C32U (green filled diamonds) by Sua5 and ScKEOPS (B); of hctRNAThr(UGU) (red filled squares) together with hctRNAThr(UGU)-U33A (orange filled triangles), -U33C (blue filled inverted triangles) and -U33G (green filled diamonds) by Sua5 and ScKEOPS (C); of hctRNAThr(UGU) (red filled squares) together with hctRNAThr(UGU)-U34A (orange filled triangles), -U34C (blue filled inverted triangles) and -U34G (green filled diamonds) by Sua5 and ScKEOPS (D); of hctRNAThr(UGU) (red filled squares) together with hctRNAThr(UGU)-G35A (orange filled triangles), -G35C (blue filled inverted triangles) and -G35U (green filled diamonds) by Sua5 and ScKEOPS (E); and of hctRNAThr(UGU) (red filled squares) together with hctRNAThr(UGU)-A38C (orange filled triangles), -A38G (blue filled inverted triangles) and -A38U (green filled diamonds) by Sua5 and ScKEOPS (F). t6A modification levels of hctRNAThr(UGU) (red filled squares), hctRNAThr(UGU)-C32A (orange filled triangles), -C32G (blue filled inverted triangles) and -C32U (green filled diamonds) by hYRDC and CeKEOPS (G); of hctRNAThr(UGU) (red filled squares), hctRNAThr(UGU)-A38C (orange filled triangles), -A38G (blue filled inverted triangles) and -A38U (green filled diamonds) by hYRDC and CeKEOPS (H); and of hctRNAThr(UGU) (red filled squares), hctRNAThr(UGU)-U33A (orange filled triangles), -U33C (blue filled inverted triangles) and -U33G (green filled diamonds) by hYRDC and CeKEOPS (I). t6A modification levels of hctRNAThr(UGU) (red filled squares), hctRNAThr(UGU)-U33A (orange filled triangles), -U33G (blue filled inverted triangles) and -U33G (green filled diamonds) by hYRDC and hKEOPS (J). The controls (black filled circles) represent assays in which no tRNAs were added. The data represent the averages of three independent experiments and the corresponding standard deviations.

We initially targeted the anticodon loop considering its proximity to the modification site A37. tRNAThr(UGU) was one of the best substrates for ScKEOPS (Supplementary Figure S3; Supplementary Table S5). In addition, tRNAThr(UGU) harbors no other modification in the anticodon loop besides t6A37 and m3C32, which requires t6A37 as a prerequisite (33,40); however, in the anticodon loop, tRNAThr(AGU) contains I34 (41), and tRNALys(UUU) contains mcm5s2U34 (42). Therefore, tRNAThr(UGU) was selected for studying the recognition mechanism at the anticodon loop. Previously, U36 was shown to be a determinant for t6A modification in Xenopus laevis oocytes (21). Its importance in modification was further confirmed using the human mitochondrial t6A modification enzyme OSGEPL1 (15). Thus, U36 and modification site A37 were not included in the present assays. For other positions in the anticodon loop, each was mutated to the other three nucleotides. We found that ScKEOPS was unable to modify all C32 mutants of tRNAThr (UGU) (Figure 3B). Consistent with the failure to modify tRNAMet(i) with C33, tRNAThr(UGU)-U33A, -U33C and -U33G were not modified by ScKEOPS (Figure 3C). However, mutations at positions U34 and G35 had little effect on t6A biogenesis (Figure 3D, E). Last, ScKEOPS was unable to introduce t6A37 in all mutants at A38 (tRNAThr(UGU)-A38C, -A38G and -A38U) (Figure 3F). Therefore, these results clearly showed that C32, U33 and A38 constitute essential determinants for t6A37 biogenesis catalyzed by ScKEOPS.

To reveal potential conservation across species, we also performed modifications of all the mutants by CeKEOPS. Failure to modify all the mutants of C32 and A38 by CeKEOPS was consistently observed (Figure 3G, H). Furthermore, the modification levels of all the mutants of U34 and G35 were comparable to that of wild-type tRNAThr(UGU) by CeKEOPS (Supplementary Figure S5A, B). In sharp contrast, tRNAThr(UGU)-U33A, -U33C and -U33G were readily modified by CeKEOPS despite variable efficiencies, suggesting that position 33 is not a critical base for CeKEOPS (Figure 3I). We also determined the modification of tRNAThr(UGU)-U33A, -U33C and -U33G by hKEOPS. Again, all the U33 mutants were modified by hKEOPS with variable efficiency (Figure 3J), suggesting that mutations at position 33 have little effect on the recognition and catalytic activity of hKEOPS.

Altogether, these results showed that ScKEOPS has a stricter substrate recognition mechanism at the anticodon loop region, requiring both the presence of C32 and U33, than do the CeKEOPS and hKEOPS complexes (in which U33 is nonessential), highlighting the critical role of C32 in t6A37 biogenesis across all eukaryotic KEOPS complexes.

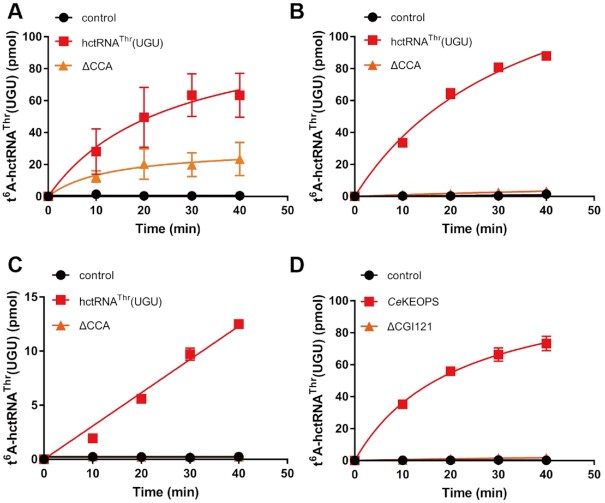

Different requirements of the CCA end in t6A37 biogenesis among KEOPS complexes

All tRNAs have a CCA end for amino acid attachment. A recent report revealed that the CCA end is essential for t6A modification by the archaeal Methanocaldococcus jannaschii KEOPS complex for binding to the Cgi121 subunit (18). However, yeast genetic data from a Cgi121 gene knockout strain showed that tRNAIle(AAU) readily harbors t6A37 (12). In addition, Pyrococcus abyssi Pcc1, Kae1 and Bud32 form a minimal functional unit that can generate t6A modification (19). These seemingly contradictory observations suggest possible divergence in the role of the CCA end in t6A modification. To precisely understand the role of the CCA end in t6A modification by eukaryotic KEOPS complexes, we transcribed a CCA end-truncated tRNAThr(UGU) mutant (tRNAThr(UGU)-ΔCCA). Modification by ScKEOPS showed that tRNAThr(UGU)-ΔCCA could be t6A modified; however, the efficiency decreased to approximately 30% of that of wild-type tRNAThr(UGU) (Figure 4A), suggesting that the CCA end is important but not essential for t6A modification. However, CeKEOPS was completely inactive in catalyzing t6A modification at tRNAThr(UGU)-ΔCCA (Figure 4B). Furthermore, we found that tRNAThr(UGU)-ΔCCA was similarly hypomodified by hKEOPS (Figure 4C), suggesting consistency between hKEOPS and CeKEOPS.

Figure 4.

Different requirements of the CCA end in t6A37 biogenesis among KEOPS complexes. Time course curves of the t6A modification of hctRNAThr(UGU) (red filled squares) and hctRNAThr(UGU)-ΔCCA (orange filled triangles) by Sua5 and ScKEOPS (A); of hctRNAThr(UGU) (red filled squares) and hctRNAThr(UGU)-ΔCCA (orange filled triangles) by hYRDC and CeKEOPS (B); of hctRNAThr(UGU) (red filled squares) and hctRNAThr(UGU)-ΔCCA (orange filled triangles) by hYRDC and hKEOPS (C); and of hctRNAThr(UGU) by hYRDC and CeKEOPS (red filled squares) or by hYRDC and CeKEOPS-ΔCGI121 (orange filled triangles) (D). The controls (black filled circles) represent assays in which no tRNAs were added (A–C) or in which no enzymes were added (D). The data represent averages of three independent experiments (A, B, D) or two independent experiments (C) and the corresponding standard deviations. The error bars were masked by the symbols in (B).

Because the CCA end is bound by Cgi121 subunit in the archaeal KEOPS complex, to further investigate the role of Cgi121 in modification, a CGI121-deleted CeKEOPS complex (CeKEOPS-ΔCGI121) was purified (Supplementary Figure S2E). In line with the lack of t6A modification of tRNAThr(UGU)-ΔCCA, biogenesis of t6A by CeKEOPS-ΔCGI121 with wild-type tRNAThr(UGU) was not observed (Figure 4C), suggesting a crucial role of the interaction between CGI121 and the CCA end in CeKEOPS.

Taken together, the above data clearly showed that the CCA end is an important but not critical motif in ScKEOPS; however, the CCA determines the t6A modification capacity of both the CeKEOPS and hKEOPS complexes, highlighting the evolutionary divergence of the CCA end in t6A modification among different KEOPS complexes.

10–25 and 11–24 base pairs are critical elements determining t6A modification levels across KEOPS complexes

In addition to the anticodon loop and CCA end, the consensus sequences among all fourteen ANN-decoding tRNAs were concentrated in the D-arm and TψC-arm (Figure 3A). Among these sites, U8 and A14 form base pairs to maintain a proper L-shaped tRNA scaffold in nearly all tRNAs. A58 functions a similar role by pairing with T54 to maintain the TψC-loop conformation (43). Therefore, the above three structural determinant sites were not included in the subsequent activity determination. The remaining elements include base pairs G18–U55, G19–C56, G10–C25 (only U25 in tRNAMet(i)), C11–G24, G53–C61, A21 and G45 (Figure 3A).

For the G18–U55 and G19–C56 base pairs, we induced single-point mutations, G18C, G19C, U55G and C56G, to disrupt the interdomain interaction between the D-loop and TψC-loop (Figure 3A). Furthermore, G18–U55 or G16–C56 was switched to C18–G55 or C16–G56, respectively, to maintain the interaction. We found that modification of all these mutants by ScKEOPS was only slightly (approximately <2-fold) decreased when compared with that of wild-type tRNAThr(UGU) (Supplementary Figure S6A), suggesting that an L-shaped tRNA tertiary structure was not required for efficient t6A biogenesis. For the G53–C61 in the TψC-stem, we changed it to C53–G61 or A53–U61. We also constructed A21C or G45A mutant (Figure 3A). Similarly, ScKEOPS introduced t6A modifications in these mutants with comparable efficiency (Supplementary Figure S6B). Thus, G53–C61, A21 and G45 seem not to be critical elements in determining t6A modification levels.

For the remaining G10–C25 and C11–G24 base pairs, we constructed C10–G25, A10–U25, G11–C24 and A11–U24 mutants. Remarkably, ScKEOPS was unable to introduce t6A modifications in the A10–U25, G11–C24, A11–U24 mutants; and the modification efficiency of C10–G25 was significantly decreased (by approximately one order of magnitude) (Figure 5A), suggesting that the G10-C25 and C11-G24 base pairs in the D-stem are crucial motifs for t6A modification. To confirm these results, C10–G25, A10–U25, G11–C24 and A11–U24 mutants were tested with hKEOPS. We found that hKEOPS was totally unable to introduce t6A modifications to all these mutants (Figure 5B), suggesting critical role of the G10–C25 and C11–G24 base pairs in t6A biogenesis. Consistently, CeKEOPS modified A10–U25, G11–C24, A11–U24 mutants with a very reduced efficiency but that of C10–G25 was only slightly decreased (Figure 5C). To explore whether C10–G25, A10–U25, G11–C24 and A11–U24 mutations induced potential structural folding defects, we compared the Tm values of wild-type tRNAThr(UGU) and the four mutants (Supplementary Table S6). A10–U25 mutant displayed a slight decrease in Tm, possible due to the weak interaction of A–U when compared with that of G10–C25 in wild-type tRNA. Tm value of G11–C24 was even higher than wild-type tRNA, suggesting more compact folding. Overall, no significant decrease in Tm values suggested little possibility of defective folding of these mutants.

Figure 5.

10–25 and 11–24 base pairs are critical elements determining t6A modification levels across KEOPS complexes. Time course curves of the t6A modification of hctRNAThr(UGU) (red filled squares), hctRNAThr(UGU)-G10C/C25G (orange filled triangles), -G10A/C25U (blue filled inverted triangles), -C11G/G24C (green filled diamonds) and -C11A/G24U (purple filled circles) by Sua5 and ScKEOPS (A), by hYRDC and hKEOPS (B) or by hYRDC and CeKEOPS (C). The controls (black filled circles) represent assays in which no tRNAs were added. The data represent the averages of three independent experiments and the corresponding standard deviations. The error bars were masked by the symbols in (B).

In summary, these results clearly showed that the two base pairs (G10–C25 and C11–G24) in the D-stem, especially the C11–G24 pair, were among the key determinants for t6A modification by various eukaryotic KEOPS complexes.

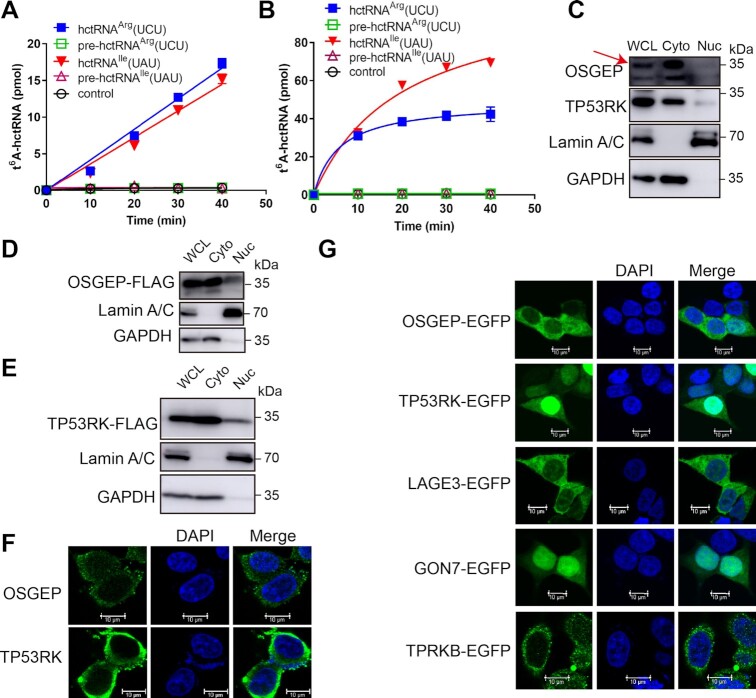

t6A is biosynthesized on mature tRNAs in cytoplasm

Notably, in human cells, two of the 14 ANN-decoding tRNAs (tRNAIle(UAU) and tRNAArg(UCU)) contain introns (39). The above data clearly showed that t6A modification enzymes require a well-organized tRNA anticodon loop for catalysis. Thus, we proposed that t6A modification likely occurs after the removal of introns. To explore this proposal, we transcribed tRNAIle(UAU) and tRNAArg(UCU) precursors (based on sequences of tRNAIle(UAU)-3-1 and tRNAArg(UCU)-3-1). Modification analyses using hKEOPS showed that t6A was only introduced to mature tRNAIle(UAU) and tRNAArg(UCU) but not their precursors (Figure 6A). We further performed similar t6A modifications using ScKEOPS with the same results (Figure 6B). Taken together, these data showed that t6A is biosynthesized on mature tRNAs.

Figure 6.

t6A is introduced to mature tRNAs in the cytoplasm. Time course curves of the t6A modification of four transcripts, tRNAArg(UCU) (blue filled squares), pre-tRNAArg(UCU) (green squares), hctRNAIle(UAU) (peach triangles), pre-hctRNAIle(UAU) (purplish red triangles), and controls (no tRNA addition, black circles), by YRDC and hKEOPS (A) or by Sua5 and ScKEOPS (B). The data represent the average of three independent replicates and the standard deviations. Subcellular localization of endogenous OSGEP and TP53RK (C) or overexpressed OSGEP-FLAG (D) and TP53RK-FLAG (E) analyzed by nucleocytoplasmic separation assays. The red arrow represents OSGEP in (C). Cytoplasmic (Cyto) and nuclear (Nuc) fractions were separated from HEK293T cells. GAPDH and Lamin A/C were used as markers of the Cyto and Nuc fractions, respectively. (F) Immunofluorescence determination of endogenous OSGEP and TP53RK in HEK293T cells. (G) Fluorescence determination of the localization of the five relevant subunits (OSGEP-EGFP, TPRKB-EGFP, GON7-EGFP, TP53RK-EGFP and LAGE3-EGFP). Thu nucleus was stained with DAPI in (F) and (G).

Due to mature human tRNAs are mainly localized in the cytoplasm under physiological conditions (38) (note that yeast intron-containing pre-tRNAs are also localized in the cytoplasm for splicing by the mitochondrial surface-localized tRNA splicing endonuclease) (44), the data suggested that t6A modification occurs in the cytoplasm. To further explore the localization of t6A biogenesis, we separated the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions of HEK293T cells. Western blot analyses involving OSGEP and TP53RK antibodies showed that most endogenous OSGEP and TP53RK proteins were localized in the cytoplasm (Figure 6C). Similar cytoplasmic distribution results were obtained by western blot analyses with cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions of cells overexpressing either FLAG-tagged OSGEP (OSGEP-FLAG) (Figure 6D) or TP53RK (TP53RK-FLAG) (Figure 6E). Cytoplasmic localization of both endogenous OSGEP and TP53RK was also confirmed by immunofluorescence analysis in which anti-OSGEP or anti-TP53RK antibodies were used (Figure 6F). Moreover, each component of the hKEOPS was fused with a C-terminal EGFP and overexpressed in HEK293T cells. Fluorescence determination showed that OSGEP-EGFP, TPRKB-EGFP and LAGE3-EGFP were almost localized in the cytoplasm, while GON7-EGFP and TP53RK-EGFP were distributed in both the cytoplasm and the nucleus (Figure 6G).

Altogether, these data showed that the hKEOPS complex is mainly localized in the cytoplasm and introduces t6A modification to mature tRNA species.

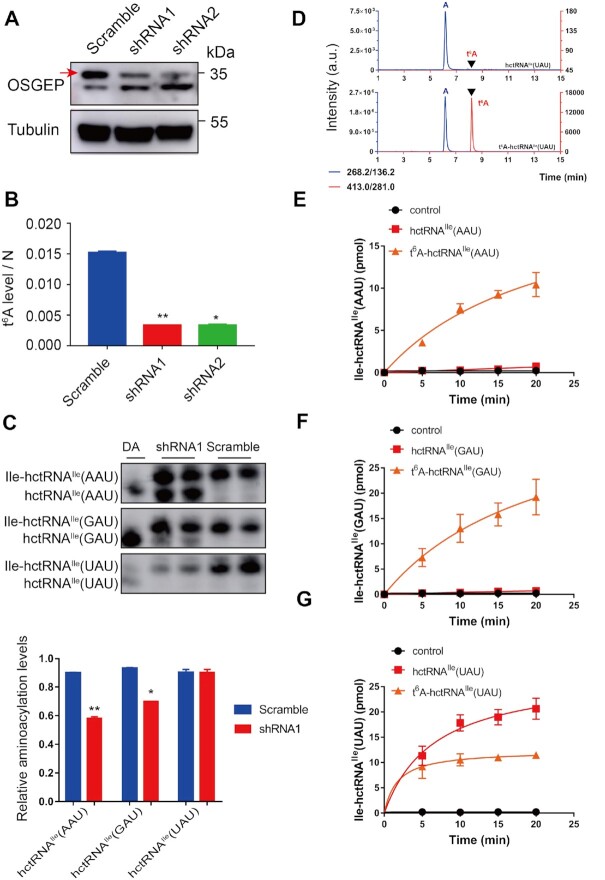

t6A is a critical positive determinant in aminoacylation of tRNAIle(AAU) and tRNAIle(GAU) but not tRNAIle(UAU) isoacceptors by human cytoplasmic IleRS

To understand the in vivo function of cytoplasmic t6A modification, we initially tried to delete the OSGEP gene in HEK293T cells by using CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing. However, despite extensive efforts, we failed to obtain a null allele of OSGEP, suggesting that t6A modification is essential to cell viability. We then constructed two HEK293T cell lines stably overexpressing two independent shRNAs targeting the OSGEP gene. The protein level of OSGEP was obviously downregulated by individual shRNAs, as evidenced via western blot analysis using anti-OSGEP antibody (Figure 7A). To confirm a decrease in t6A content in tRNAs due to OSGEP knockdown, tRNALys(UUU) was purified from WT and the two knockdown (KD) cells (shRNA1 and shRNA2) and then hydrolyzed to mononucleosides for UPLC–MS/MS analysis. Clearly, the t6A content of tRNALys(UUU) in KD cells was significantly lower than that in WT cells (Figure 7B), demonstrating a reduction in t6A modification levels.

Figure 7.

t6A is a critical positive determinant in aminoacylation of tRNAIle(AAU) and tRNAIle(GAU) but not tRNAIle(UAU) isoacceptors by human cytoplasmic IleRS. (A) Western blot results showing OSGEP protein levels in HEK293T cells infected with OSGEP-specific (shRNA1, shRNA2) or control (Scramble) shRNAs. The red arrow represents OSGEP. (B) UPLC-MS/MS quantification of t6A modification levels in tRNALys(UUU) purified from WT and two KD (shRNA1 and shRNA2) cells. The amounts of t6A and N (= A+C+G+U) were calculated based on the area under the t6A or N peaks in the UPLC-MS/MS chromatogram. The data were two independent replicates and the corresponding standard deviations. The P values were determined using two-tailed Student's t test for paired samples. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. (C) Determination of tRNA charging levels of three tRNAIle isoacceptors in wild-type (Scramble) and OSGEP knockdown HEK293T cell lines by acid northern blots. The relative aminoacylation levels were calculated based on two independent replicates and their corresponding standard deviations. DA, de-aminoacylated tRNA. The P values were determined using two-tailed Student's t test for paired samples. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. (D) UPLC-MS/MS analysis of the digested products of hypo- or modified tRNAIle(UAU). Aminoacylation of hctRNAIle(AAU) (red filled squares) and t6A-hctRNAIle(AAU) (orange filled triangles) (E); or hctRNAIle(GAU) (red filled squares) and t6A-hctRNAIle(GAU) (orange filled triangles) (F) or hctRNAIle(UAU) (red filled squares) and t6A-hctRNAIle(UAU) (orange filled triangles) (G) by hIleRS. Controls (black filled circles) represent assays in which no tRNAs were added. The data represent the averages of three independent experiments and the corresponding standard deviations.

We initially explored the effects of t6A biogenesis impairment on steady-state tRNA levels for all ANN-decoding tRNAs via northern blots. The results clearly showed that the amounts of all ANN-decoding tRNAs were comparable between WT and shRNA1 cells (Supplementary Figure S7A). Furthermore, aminoacylation assays via acid northern blot analysis, in which condition the amino acid moiety remained uncleaved on tRNAs, revealed that charging levels for most tRNAs were not influenced in shRNA1 cells (Supplementary Figure S7B). However, the aminoacylation levels of two tRNAIle isoacceptors (tRNAIle(AAU) and tRNAIle(GAU)) were obviously and significantly downregulated in repeated analyses (Figure 7C). Unexpectedly, alterations in the charging of tRNAIle (UAU) were not observed (Figure 7C). Taken together, these data suggested that t6A modification has little effect on determining tRNA charging levels of most ANN-decoding tRNAs but functions as a key element in charging tRNAIle (AAU) and tRNAIle (GAU) isoacceptors in vivo.

To further explore whether t6A biogenesis determines tRNAIle aminoacylation, we transcribed human cytoplasmic tRNAIle(AAU), tRNAIle(GAU) and tRNAIle(UAU). t6A-modified transcripts were then obtained by incubating transcribed tRNAs with Sua5-ScKEOPS in vitro. The modified tRNAIle(UAU) product was then subjected to hydrolysis to mononucleosides and subsequently analyzed via UPLC–MS/MS, confirming that the tRNA transcript was successfully loaded with the t6A moiety (Figure 7D). Full-length human cytoplasmic isoleucyl-tRNA synthetase (hIleRS, encoded by IARS1) forms a protein aggregate due to the presence of a C-terminal appended domain containing two repeats, which is not essential for tRNAIle aminoacylation (45) and probably mediates hIleRS into the cytoplasmic multiple tRNA synthetase complex (46). We overexpressed a gene encoding a truncated hIleRS (Met1-Ser1073) devoid of the C-terminal domain (Supplementary Figure S8). In vitro aminoacylation assays clearly showed that hIleRS was completely incapable of catalyzing aminoacylation of tRNAIle(AAU) and tRNAIle(GAU) transcription; however, charging of the tRNAIle(UAU) transcript was robust and obvious. In contrast, t6A modification readily afforded aminoacylation of tRNAIle(AAU) and tRNAIle(GAU) by hIleRS (Figure 7E, F); however, aminoacylation of tRNAIle(UAU) was obviously inhibited by the presence of a t6A moiety by ∼2-fold (Figure 7G). These in vitro data were consistent with those obtained from the acid northern blot analyses.

Taken together, these data showed that knockdown of OSGEP led to an obvious decrease in t6A modification levels in human tRNAs. t6A modification defects have no role in determining ANN-decoding tRNA abundance or the tRNA charging level of most tRNAs, excluding two tRNAIle isoacceptors. t6A modification is a critical determinant for tRNAIle isoacceptor-specific aminoacylation by hIleRS.

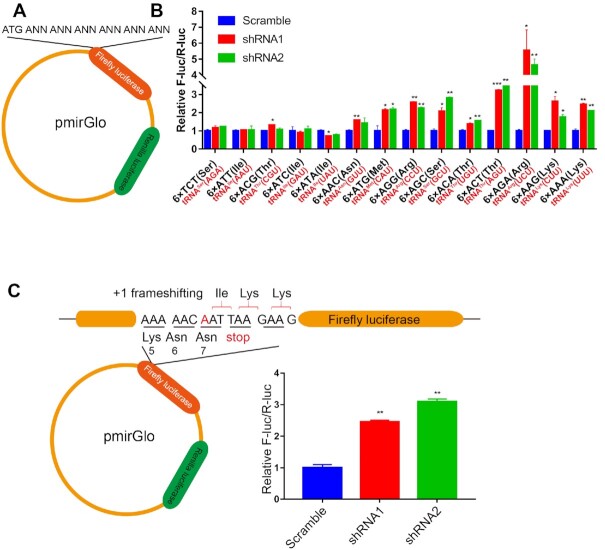

Role of t6A modification in the strength of codon-anticodon pairing and prevention of +1 frameshifting

We subsequently explored any potential contribution of t6A modification to codon decoding. We reasoned that if t6A modification is able to control A1 (of codon) and U36 base pairing in human cells, t6A deficiency would cause alteration in codon-anticodon base pairing strength and subsequent decoding efficiency. To this end, we designed a dual-luciferase reporter system in which 6× ANN codons were inserted downstream of the F-luc gene ATG start codon in a pmirGLO plasmid, which simultaneously contained a separate R-luc gene as a control (Figure 8A). By determining and comparing the fluorescence densities of F-luc and R-luc in WT and OSGEP KD cells, we quantified the decoding efficiency of each codon by a t6A-harboring tRNA. We initially observed no alteration in translational efficiency of 6× TCT (Ser), which is decoded by non-t6A-modified tRNASer(AGA), between WT and KD cells. Then, the results showed that the translational efficiency of 6× AGG or AGA (Arg), 6× AAA or AAG (Lys), 6× AGC (Ser), 6× ATG (Met) and 6× ACT or ACA (Thr) in KD cells was significantly higher than that in the WT cells. However, the decoding efficiency of 6× ACG (Thr) and 6× ATT or ATC (Ile) codons in the KD cells was comparable to that in the WT cells. Note that the charging level of all tRNAs except tRNAIle(AAU) (decoding ATT codon) and tRNAIle(GAU) (decoding ATC codon) remained unchanged in the KD cells. The decoding rate of 6× ATA (Ile) codons in KD cells decoded by tRNAIle(UAU) with unaltered aminoacylation levels was lower than that in the WT cells (Figure 8B). Thus, these data showed that t6A modification contributes distinctly to decoding efficiency at different codons. For most ANN codons, t6A modifications of tRNA seemed to restrict their decoding efficiency; however, t6A modification of tRNAIle(UAU) probably stimulated its capacity to decode ATA codons. These codon-specific differential effects of t6A modification on tRNA decoding capacities are similar to observations in yeast cells (27).

Figure 8.

Effects of t6A deficiency on codon-anticodon pairing and +1 frameshifting. (A) Schematic showing the dual-luciferase system, in which 6× ANN codons were inserted downstream of the F-luc gene ATG start codon in a pmirGLO plasmid, and a separate R-luc gene was used as a control. (B) Effects of t6A deficiency on ANN-codon (in black in the x-axis) decoding efficiency by various tRNAs (in red in the x-axis) in WT (Scramble) and two OSGEP KD cell lines. 6× TCT codons decoded by non-t6A-modified tRNASer(AGA) were included as controls. The data represent the average of two independent replicates and the standard deviations. The P values were determined using two-tailed Student's t test for paired samples. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001. (C) Schematic showing the +1 frameshifting assay at the ATT codon decoded by tRNAIle(AAU). An “A” nucleotide (indicated by red) was inserted upstream of the ATT codon at position 7 of the Ile codon of F-luc (AATT-F-Luc). The data represent the average of three independent replicates and the standard deviations. The P values were determined using two-tailed Student's t test for paired samples. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001.

Furthermore, we designed a reporter based on the above-described dual-luciferase system to assess whether t6A modification at a given tRNA is able to prevent +1 frameshifting. We initially selected tRNALys(UUU), tRNAIle(AAU) and tRNAAsn(GUU) because the codon-anticodon U-A base pairings may be more prone to +1 frameshifting due to their weak interaction strength. To measure +1 frameshifting at the ATT codon decoded by tRNAIle(AAU), an “A” nucleotide was inserted upstream of the ATT codon at position 7 of the Ile codon of F-luc (AATT-F-Luc) (Figure 8C). No F-luc was detected without +1 frameshifting due to premature translational termination; however, the occurrence of +1 frameshifting at this codon increased the F-luc activity in KD cells (the primary sequence of F-luc was unaltered). We detected slight expression of AATT-F-Luc in WT HEK293T cells, indicating that natural +1 frameshifting occurs at the ATT codon in human cells. Strikingly, F-luc activity was significantly elevated in KD cells compared with WT cells (by ∼2–3-fold) (Figure 8C), suggesting that a deficiency in t6A among tRNAIle(AAU) promotes +1 frameshifting at the AUU codon. Notably, comparable increases in +1 frameshifting due to Sua5 deletion has also been observed in yeast (26). Similar designs were applied to the AAA codon (decoded by tRNALys(UUU)) and AAC codon (decoded by tRNAAsn(GUU)) (Supplementary Figure S9); however, no expression of F-luc was observed in either WT or KD cells, indicating that t6A deficiency in tRNALys(UUU) and tRNAAsn(GUU) triggers no +1 frameshifting at AAA or AAC codons.

DISCUSSION

C32 and the D-stem are essential elements in t6A biogenesis by various KEOPSs

In this work, we studied in detail how representative KEOPS complexes from yeast, humans and nematodes accurately select tRNA substrates. We found that all three KEOPS complexes are critically dependent on common elements embedded in the anticodon loop and the D-stem. In particular, in addition to previously identified U36 and A38, C32 is a critical determinant for KEOPS complexes (21). An earlier study using the Xenopus laevis oocyte t6A modification system failed to determine the critical importance of C32, likely because double mutations of C32 and A38 were introduced; thus, the contribution of C32 was not definitively determined. However, C32 of human mitochondrial tRNAThr is not an essential element in mitochondrial t6A formation by hYRDC and OSGEPL1 (15), suggesting that divergence in the recognition of position 32 has occurred between cytoplasmic and mitochondrial t6A modification enzymes. It is also notable that in some archaea, such as Methanococcus jannaschii, the tRNAThr(GGU) isoacceptor, which is absent in eukaryotic genomes, contains a U32 and t6A-analogous hn6A modification (N6-hydroxynorvalylcarbamoyl adenosine) derived from hydroxy norvaline instead of threonine, although most t6A- or hn6A-containing tRNAs in M. jannaschii contain C32 (47,48). In fact, U32 is widespread in various archaeal tRNAThr(GGU) isoacceptors (49), probably because position 32 is more flexible in archaea than in eukaryotes because of the lack of m3C32 modification in the former (1,33,47). Moreover, hn6A is found in some thermophilic bacteria (48). It has been suggested that hn6A is likely synthesized by archaeal Sua5 and KEOPS, because archaeal Sua5 was proven to be active in hydrolyzing ATP to AMP in the presence of hydroxy norvaline (50). Indeed, a recent report also confirmed that bacterial TsaC is able to exhibit relaxed substrate specificity to produce a variety of TC-AMP analogs (51). These observations suggested that the archaeal KEOPS is likely not reliant on C32 as a key determinant for t6A or hn6A biogenesis and that dependence on C32 was likely a later event that occurred during KEOPS evolution. The C32-binding site of the KEOPS is unclear. According to a recent KEOPS-tRNA interaction model, LAGE3 and OSGEP (human Pcc1 and Kae1, respectively) constitute the binding surface for the tRNA anticodon loop (18). Pcc1 and Kae1 have been consistently proposed to be tRNA-binding sites (19). While A37-containing one site of the loop extends into the active site of OSGEP, another site with C32 is probably bound by LAGE3. Indeed, mutation of a potential tRNA-binding residue (Arg63 in the Pcc1 subunit of the archaeal KEOPS) abolishes the t6A modification activity of archaeal KEOPS (18). Gon7 subunit interacts with Pcc1 in an opposite side and is spatially far from tRNA anticodon loop (5); it is unlikely to be C32 binding partner. Nonetheless, the interaction between the tRNA anticodon loop and KEOPS need to be further explored in detail.

In addition, we identified here that two base pairs in the D-stem, G10–C25 and C11–G24, constitute the key elements determining efficient t6A biogenesis. Only G10-U25 is present in the human tRNAMet(i) isoacceptor, which is a comparably good substrate of KEOPS. Similarly, a previous report revealed the critical role of a conserved 10CU11 motif in the D-arm of archaeal tRNAs in both t6A modification and stimulation of the ATPase of archaeal Bud32 (18). This evidence highlights the conserved feature of the critical role of the D-arm in both eukaryotic and archaeal KEOPS complexes. The G10–C25 and C11–G24 motifs probably interact with OSGEP and/or TP53RK according to the archaeal KEOPS–tRNA interaction model (5,18).

Requirement of CCA end is divergent among various KEOPSs

A previous report has shown that tRNAIle from yeast cells deprived of Cgi121 harbors an abundance of t6A modification, implying that the CCA end of yeast tRNA is not a determinant (12). Indeed, we found that ScKEOPS is able to introduce t6A modification with CCA-truncated tRNA in vitro. However, both the hKEOPS and CeKEOPS complexes are completely incapable of catalyzing t6A biogenesis in the absence of the CCA end. Our data are consistent with the recent findings that CCA-truncated tRNA is a poor binding substrate of hKEOPS (18). Taken together, these data suggested that hKEOPS and CeKEOPS more resemble archaeal KEOPS in terms of the requirement for the CCA end than ScKEOPS.

Possible coevolution of position 33 of tRNAs and the t6A modification machinery

One of the unexpected findings is the sharp difference in the role of position 33 between the different t6A machineries. Both the hKEOPS and CeKEOPS complexes have relaxed requirements for position 33. Similar results were observed with OSGEPL1 (15). However, C33 is obviously an anti-determinant of both EcTsaBCDE and yeast Sua5-KEOPS. Only a single mutation of C33 to U33 makes human tRNAMet(i) a well-qualified substrate for yeast t6A modification machinery. Interestingly, nearly all ANN-decoding tRNAs contain U33; however, tRNAMet(i) from multicellular organisms is an exception by later evolving a C33, possibly to finetune initiation efficiency; but the exact evolutionary advantage needs to be further studied. On the other hand, accompanying a relaxed requirement at position 33 due to evolution of U33 to C33 in tRNAMet(i), the CCA end seems to play a critical role in modification by KEOPS complexes from higher eukaryotes (humans and nematodes). Based on the above observations and analyses, we proposed a hierarchal evolutionary scenario that occurred from bacteria and single-cellular lower eukaryotes to higher eukaryotes. In bacteria with all U33-containing ANN-decoding tRNAs, U33 is one of the key determinants; in accordance with the fact that there is no Cgi121 counterpart in EcTsaBCDE, the CCA end has little effect on t6A biogenesis; in yeast with all U33-containing ANN-decoding tRNAs, ScKEOPS still depends on U33 as a determinant, while the CCA end contributes to t6A formation by binding Cgi121, as evidenced by the lower modification of the CCA end-truncated tRNA mutant; in higher eukaryotes with both U33- and C33-containing tRNAs, the requirement of position 33 is negated, but CCA end functions as a determinant.

t6A is a critical positive determinant in aminoacylation of tRNAIle(AAU) and tRNAIle(GAU)

We determined that all cytosolic ANN-decoding tRNAs in human cells harbor a t6A moiety. Indeed, all these tRNAs contain all necessary determining elements (G10–C25, C11-G24, C32, U36, A37, A38, the CCA end), as revealed in this study and others, except G10-U25 in tRNAMet(i). Our data also clearly demonstrated that t6A modification contributes little to human tRNA abundance. However, the effect on aminoacylation levels varied and was tRNA isoacceptor specific. The charging levels of most ANN-decoding tRNAs were not altered upon knockdown of OSGEP and upon a decrease in t6A abundance; however, tRNAIle(AAU) and tRNAIle(GAU), but not tRNAIle(UAU) displayed obviously reduced tRNA aminoacylation levels in vivo due to OSGEP knockdown. Furthermore, the in vitro data clearly indicated that t6A is a critical determinant in the aminoacylation of tRNAIle(AAU) and tRNAIle(GAU) by hIleRS. Interestingly, the tRNAIle(UAU) transcript is strongly charged in the absence of t6A modification. t6A in bacterial tRNAIle has proven to be a strong positive determinant for aminoacylation by bacterial IleRS (24). However, in a bacterial IleRS-tRNAIle cocrystal structure (PDB No. 1QU3) (52), A37 was shown to be distant from the anticodon-binding domain of IleRS and did not interact directly with the enzyme. Thus, the rationale of the key role of t6A modification in aminoacylation is unclear. Yeast IleRS seems to be insensitive to t6A modification when total yeast tRNAs are used as substrates (24). Consistently, yeast cells devoid of t6A modification (in which the individual genes encoding components of KEOPS were removed), are still viable despite a reduced growth rate of the cells (12). The pivotal role of t6A modification of tRNAIle(AAU) and tRNAIle(GAU) in aminoacylation likely explains why the OSGEP gene cannot be deleted via CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing due to uncharged tRNAIle and abolished mRNA translation after deletion. However, the molecular basis for the tRNAIle isoacceptor-specific requirement of t6A biogenesis in tRNA charging by hIleRS needs to be further explored.

t6A modification finetunes translational elongation in human cells

Using a luciferase-based reporter system, we also explored the potential role of t6A modification in translation elongation. Interestingly, we found that, for most ANN codes, decreased t6A modification seems to stimulate translational elongation speed, as evidenced by the increased firefly luciferase signal. In contrast, for the Ile ATA codon, reduced amounts of firefly luciferase were observed, suggesting that the translational elongation speed at the ATA codon was downregulated due to impaired t6A modification. Overall, impaired t6A modification levels due to OSGEP knockdown led to various effects on translational efficiency at ANN codons. Various effects on the decoding of different codons by t6A were also observed in yeast in which the elongation rate at codons decoded by highly abundant tRNAs and I34:C3 pairs was suppressed, while that by rare tRNAs and G34:U3 pairs increased in response to t6A modification (27).

DATA AVAILABILITY

All data presented in this study are available within the figures and in the Supplementary data.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Drs Xinxin Chen and Lei Wang (Institute of Biophysics, CAS) for technical assistance. We thank the core facility of molecular biology of our institute for technical support in UPLC-MS/MS analysis. We also thank Drs Herman van Tilbeurgh (Institute for Integrative Biology of the Cell, CNRS) and Jin-Qiu Zhou in our institute for providing the plasmid expressing ScKEOPS.

Contributor Information

Jin-Tao Wang, State Key Laboratory of Molecular Biology, CAS Center for Excellence in Molecular Cell Science, Shanghai Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, 320 Yue Yang Road, Shanghai 200031, China.

Jing-Bo Zhou, State Key Laboratory of Molecular Biology, CAS Center for Excellence in Molecular Cell Science, Shanghai Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, 320 Yue Yang Road, Shanghai 200031, China.

Xue-Ling Mao, State Key Laboratory of Molecular Biology, CAS Center for Excellence in Molecular Cell Science, Shanghai Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, 320 Yue Yang Road, Shanghai 200031, China.

Li Zhou, School of Life Sciences, Lanzhou University, 222 South Tianshui Road, Lanzhou 730000, Gansu.

Meirong Chen, School of Pharmacy, China Pharmaceutical University, 639 Longmian Avenue, Nanjing 211198, Jiangsu.

Wenhua Zhang, School of Life Sciences, Lanzhou University, 222 South Tianshui Road, Lanzhou 730000, Gansu.

En-Duo Wang, State Key Laboratory of Molecular Biology, CAS Center for Excellence in Molecular Cell Science, Shanghai Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, 320 Yue Yang Road, Shanghai 200031, China; School of Life Science and Technology, ShanghaiTech University, 393 Middle Hua Xia Road, Shanghai 201210, China.

Xiao-Long Zhou, State Key Laboratory of Molecular Biology, CAS Center for Excellence in Molecular Cell Science, Shanghai Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, 320 Yue Yang Road, Shanghai 200031, China.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

National Key Research and Development Program of China [2017YFA0504000, 2021YFA1300800, 2021YFC2700903]; Natural Science Foundation of China [91940302, 31870811, 31670801, 31822015, 81870896, 32000889, 32000847]; Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences [XDB19010203]; Shanghai Key Laboratory of Embryo Original Diseases [Shelab201904]; Key Laboratory of Reproductive Genetics, Ministry of Education, Zhejiang University [ZDFY2020-RG-0003]. Funding for open access charge: Natural Science Foundation of China.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Wolff P., Villette C., Zumsteg J., Heintz D., Antoine L., Chane-Woon-Ming B., Droogmans L., Grosjean H., Westhof E.. Comparative patterns of modified nucleotides in individual tRNA species from a mesophilic and two thermophilic archaea. RNA. 2020; 26:1957–1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Suzuki T. The expanding world of tRNA modifications and their disease relevance. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2021; 22:375–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhou J.B., Wang E.D., Zhou X.L.. Modifications of the human tRNA anticodon loop and their associations with genetic diseases. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2021; 78:7087–7105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. de Crecy-Lagard V., Boccaletto P., Mangleburg C.G., Sharma P., Lowe T.M., Leidel S.A., Bujnicki J.M.. Matching tRNA modifications in humans to their known and predicted enzymes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019; 47:2143–2159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Beenstock J., Sicheri F.. The structural and functional workings of KEOPS. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021; 49:10818–10834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Thiaville P.C., Iwata-Reuyl D., de Crecy-Lagard V.. Diversity of the biosynthesis pathway for threonylcarbamoyladenosine (t(6)A), a universal modification of tRNA. RNA Biol. 2014; 11:1529–1539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. El Yacoubi B., Lyons B., Cruz Y., Reddy R., Nordin B., Agnelli F., Williamson J.R., Schimmel P., Swairjo M.A., de Crecy-Lagard V.. The universal YrdC/Sua5 family is required for the formation of threonylcarbamoyladenosine in tRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009; 37:2894–2909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Missoury S., Plancqueel S., Li de la Sierra-Gallay I., Zhang W., Liger D., Durand D., Dammak R., Collinet B., van Tilbeurgh H.. The structure of the TsaB/TsaD/TsaE complex reveals an unexpected mechanism for the bacterial t6A tRNA-modification. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018; 46:5850–5860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Luthra A., Swinehart W., Bayooz S., Phan P., Stec B., Iwata-Reuyl D., Swairjo M.A.. Structure and mechanism of a bacterial t6A biosynthesis system. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018; 46:1395–1411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Deutsch C., El Yacoubi B., de Crecy-Lagard V., Iwata-Reuyl D.. Biosynthesis of threonylcarbamoyl adenosine (t6A), a universal tRNA nucleoside. J. Biol. Chem. 2012; 287:13666–13673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. El Yacoubi B., Hatin I., Deutsch C., Kahveci T., Rousset J.P., Iwata-Reuyl D., Murzin A.G., de Crecy-Lagard V.. A role for the universal Kae1/Qri7/YgjD (COG0533) family in tRNA modification. EMBO J. 2011; 30:882–893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Srinivasan M., Mehta P., Yu Y., Prugar E., Koonin E.V., Karzai A.W., Sternglanz R.. The highly conserved KEOPS/EKC complex is essential for a universal tRNA modification, t6A. EMBO J. 2011; 30:873–881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Luthra A., Paranagama N., Swinehart W., Bayooz S., Phan P., Quach V., Schiffer J.M., Stec B., Iwata-Reuyl D., Swairjo M.A.. Conformational communication mediates the reset step in t6A biosynthesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019; 47:6551–6567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mao D.Y., Neculai D., Downey M., Orlicky S., Haffani Y.Z., Ceccarelli D.F., Ho J.S., Szilard R.K., Zhang W., Ho C.S.et al.. Atomic structure of the KEOPS complex: an ancient protein kinase-containing molecular machine. Mol. Cell. 2008; 32:259–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhou J.B., Wang Y., Zeng Q.Y., Meng S.X., Wang E.D., Zhou X.L.. Molecular basis for t6A modification in human mitochondria. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020; 48:3181–3194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wan L.C., Mao D.Y., Neculai D., Strecker J., Chiovitti D., Kurinov I., Poda G., Thevakumaran N., Yuan F., Szilard R.K.et al.. Reconstitution and characterization of eukaryotic N6-threonylcarbamoylation of tRNA using a minimal enzyme system. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013; 41:6332–6346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lin H., Miyauchi K., Harada T., Okita R., Takeshita E., Komaki H., Fujioka K., Yagasaki H., Goto Y.I., Yanaka K.et al.. CO2-sensitive tRNA modification associated with human mitochondrial disease. Nat. Commun. 2018; 9:1875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Beenstock J., Ona S.M., Porat J., Orlicky S., Wan L.C.K., Ceccarelli D.F., Maisonneuve P., Szilard R.K., Yin Z., Setiaputra D.et al.. A substrate binding model for the KEOPS tRNA modifying complex. Nat. Commun. 2020; 11:6233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Perrochia L., Guetta D., Hecker A., Forterre P., Basta T.. Functional assignment of KEOPS/EKC complex subunits in the biosynthesis of the universal t6A tRNA modification. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013; 41:9484–9499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kopina B.J., Missoury S., Collinet B., Fulton M.G., Cirio C., van Tilbeurgh H., Lauhon C.T.. Structure of a reaction intermediate mimic in t6A biosynthesis bound in the active site of the TsaBD heterodimer from Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021; 49:2141–2160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Morin A., Auxilien S., Senger B., Tewari R., Grosjean H.. Structural requirements for enzymatic formation of threonylcarbamoyladenosine (t6A) in tRNA: an in vivo study with Xenopus laevis oocytes. RNA. 1998; 4:24–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wang Y., Zeng Q.Y., Zheng W.Q., Ji Q.Q., Zhou X.L., Wang E.D.. A natural non-Watson-Crick base pair in human mitochondrial tRNAThr causes structural and functional susceptibility to local mutations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018; 46:4662–4676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Murphy F.V.t., Ramakrishnan V., Malkiewicz A., Agris P.F.. The role of modifications in codon discrimination by tRNA(Lys)UUU. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2004; 11:1186–1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Thiaville P.C., El Yacoubi B., Kohrer C., Thiaville J.J., Deutsch C., Iwata-Reuyl D., Bacusmo J.M., Armengaud J., Bessho Y., Wetzel C.et al.. Essentiality of threonylcarbamoyladenosine (t(6)A), a universal tRNA modification, in bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 2015; 98:1199–1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Braun D.A., Rao J., Mollet G., Schapiro D., Daugeron M.C., Tan W., Gribouval O., Boyer O., Revy P., Jobst-Schwan T.et al.. Mutations in KEOPS-complex genes cause nephrotic syndrome with primary microcephaly. Nat. Genet. 2017; 49:1529–1538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lin C.A., Ellis S.R., True H.L.. The Sua5 protein is essential for normal translational regulation in yeast. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010; 30:354–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Thiaville P.C., Legendre R., Rojas-Benitez D., Baudin-Baillieu A., Hatin I., Chalancon G., Glavic A., Namy O., de Crecy-Lagard V.. Global translational impacts of the loss of the tRNA modification t(6)A in yeast. Microb. Cell. 2016; 3:29–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Arrondel C., Missoury S., Snoek R., Patat J., Menara G., Collinet B., Liger D., Durand D., Gribouval O., Boyer O.et al.. Defects in t(6)A tRNA modification due to GON7 and YRDC mutations lead to Galloway-Mowat syndrome. Nat. Commun. 2019; 10:3967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Edvardson S., Prunetti L., Arraf A., Haas D., Bacusmo J.M., Hu J.F., Ta-Shma A., Dedon P.C., de Crecy-Lagard V., Elpeleg O.. tRNA N6-adenosine threonylcarbamoyltransferase defect due to KAE1/TCS3 (OSGEP) mutation manifest by neurodegeneration and renal tubulopathy. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2017; 25:545–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Collinet B., Friberg A., Brooks M.A., van den Elzen T., Henriot V., Dziembowski A., Graille M., Durand D., Leulliot N., Saint Andre C.et al.. Strategies for the structural analysis of multi-protein complexes: lessons from the 3D-Repertoire project. J. Struct. Biol. 2011; 175:147–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhang W., Collinet B., Perrochia L., Durand D., van Tilbeurgh H.. The ATP-mediated formation of the YgjD-YeaZ-YjeE complex is required for the biosynthesis of tRNA t6A in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015; 43:1804–1817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zhou X.L., Zhu B., Wang E.D.. The CP2 domain of leucyl-tRNA synthetase is crucial for amino acid activation and post-transfer editing. J. Biol. Chem. 2008; 283:36608–36616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mao X.L., Li Z.H., Huang M.H., Wang J.T., Zhou J.B., Li Q.R., Xu H., Wang X.J., Zhou X.L.. Mutually exclusive substrate selection strategy by human m3C RNA transferases METTL2A and METTL6. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021; 49:8309–8323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zeng Q.Y., Peng G.X., Li G., Zhou J.B., Zheng W.Q., Xue M.Q., Wang E.D., Zhou X.L.. The G3-U70-independent tRNA recognition by human mitochondrial alanyl-tRNA synthetase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019; 47:3072–3085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]