Abstract

Background

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a progressive, debilitating illness characterized by exacerbations that require timely intervention. COPD patients often rely on informal caregivers—relatives or friends—for assistance with functioning and support. Caregivers perform roles that may be particularly important during acute exacerbations in monitoring symptoms and seeking medical intervention. However, little is known about caregivers’ roles and experiences as they support their patients during exacerbations.

Purpose

To explore the experiences, roles in care seeking, and needs of caregivers during COPD exacerbations.

Methods

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 24 caregivers of Veterans with COPD who experienced a recent exacerbation. Interviews were recorded, transcribed, and analyzed using inductive content analysis.

Results

Five themes arose: (a) caregivers reported continuously monitoring changes in patients symptom severity to identify exacerbations; (b) caregivers described emotional reactions evoked by exacerbations and constant vigilance; (c) caregivers described disagreements with their patient in interpreting symptoms and determining the need for care seeking; (d) caregivers noted uncertainty regarding their roles and responsibilities in pursuing care and their approaches to promote care varied; and (e) expressed their need for additional information and support. Caregivers of patients with COPD often influence whether and when patients seek care during exacerbations. Discrepancies in symptom evaluations between patients and caregivers paired with the lack of information and support available to caregivers are related to delays in care seeking. Clinical practice should foster self-management support to patient–caregiver dyads to increase caregiver confidence and patient openness to their input during exacerbations.

Keywords: Caregiver, COPD, Veteran, Acute exacerbation

Caregivers of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients report challenges with COPD self-management and anxiety related to care seeking during acute exacerbations, and desire additional support and information

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is characterized by persistent airflow obstruction in the lungs, with symptoms of breathlessness upon exertion during daily activities or at rest, as well as fatigue, weakness, cough, and sputum production [1]. More than half of patients with severe COPD report that their morning symptoms limit their activities of daily living (ADLs) [2, 3]. In the USA, approximately one in 20 adults will develop COPD and approximately half of patients with severe COPD will die within 10 years of diagnosis [4, 5]. Patients with COPD frequently experience acute events characterized by worsening respiratory symptoms that often require hospitalizations [1, 6]. Healthcare utilization among patients with COPD is high, including emergency room visits, hospitalizations, outpatient visits, and long hospital stays, and in the USA alone, COPD is estimated to cost $38 billion annually [7, 8].

While COPD cannot be cured, it can be effectively managed. Typical treatment recommendations include smoking cessation, medications, oxygen therapy, and pulmonary rehabilitation [9]. Early detection and prompt treatment of exacerbations can facilitate symptom relief, improve quality of life, decrease morbidity and mortality, and reduce hospitalizations [10]. Yet, many patients with COPD do not seek timely care leading to hospitalizations and rehospitalizations [6]. A key challenge for patients with COPD is that care seeking relies on symptom monitoring and they vary in recognizing and appreciating symptom trajectories [11]. Indeed, the gradual worsening of respiratory symptoms as the disease progresses introduces further challenges in symptom identification and subsequent care seeking. Misidentification of respiratory symptoms or misperceptions about the severity of symptoms could delay care seeking and impair the efficacy of the treatment plan [12]. Progression of symptoms and disability and limitations in self-care abilities may lead patients with COPD to become more care dependent as their disease progresses.

When knowledgeable and prepared, informal caregivers may assist patients in monitoring and interpreting symptoms, thereby enhancing identification of exacerbations. Up to 70% of patients with COPD have one or more informal caregivers, such as relatives or friends, who assist the individual with the complex management and monitoring of COPD and provide both practical and emotional support [13]. These patients, particularly those with severe COPD, depend on informal caregivers for emotional support, assistance with ADLs, facilitating treatment adherence, tracking worsening symptoms, and navigating hospitalizations. Having an informal caregiver, hereafter called caregiver, is associated with better treatment adherence, better capacity for physical activity, and less frequent emergency room visits [14, 15]. The course of COPD is unpredictable, requiring flexibility and timely response to exacerbations from both patients and caregivers [16].

Given the unpredictable, progressive, chronic trajectory of COPD, the role of a caregiver can be lengthy and ever-changing. Caregivers need to adapt to shifting needs and navigate the unpredictability associated with COPD and potentially, their patient’s changing perceptions of the disease. While the challenges of being a caregiver for people with chronic illnesses are well documented [17, 18], the specific role of caregivers in helping patients respond to and manage COPD exacerbations is not well understood. Caregivers of patients with COPD report ambiguity regarding their role and responsibilities, ambivalence in their willingness to be involved in the patient’s medical treatment, and hypervigilance [19]. A few studies suggest that caregivers of patients with COPD experience burden, depression, anxiety, and role confusion similar to caregivers of people with other chronic illnesses [17, 18, 20, 21]. Caregivers report experiencing severe anxiety both in anticipation of and during their patients’ exacerbations [16]. In addition, uncertainty about the trajectory of the illness contributes to caregiver stress [15].

Despite the significant caregiver burden associated with COPD coupled with the anxiety and distress related to its management experienced by patient–caregiver dyads, caregiver perceptions and influence on care-seeking behavior have received little attention in the literature.

Patients and caregivers may have discordant perceptions of the patient’s symptoms, severity, health status, and satisfaction with medical treatment plans, which could influence management of COPD and care-seeking decisions during exacerbations [15]. As with other serious and chronic conditions, caregivers may play critical roles in decisions to seek care and in symptom management during COPD exacerbations. Therefore, the current study aimed to understand caregiver roles and experiences related to patients’ COPD exacerbations, including the perceived need for care and influence on care seeking.

Methods

This study represents an analysis of caregiver data collected as part of a larger mixed-methods study aimed at understanding COPD exacerbations and delays in care seeking among Veterans enrolled at two major Veteran Affairs (VA) medical centers in the USA. The current study sought to answer the question, “What do caregivers report as their role in Veterans’ COPD exacerbations and decisions to seek care?” We utilized a qualitative descriptive design [22]. In order to gain insight into the experiences, care-seeking roles, and needs of caregivers in Veterans’ COPD exacerbations. The study was approved by the local Institutional Review Board (masked for review).

Participants

We recruited a convenience sample of caregivers of Veterans participating in a mixed-methods study on care seeking during COPD exacerbations. Veterans enrolled in the parent study had a diagnosis of COPD confirmed by spirometry (FEV1/FVC <0.70) and at least one treated COPD exacerbation in the 12 months prior to enrollment. Nursing home residents and those with a diagnosis of dementia or Alzheimer’s disease were excluded. The study did not require the Veteran to have a caregiver in order to participate in the study. For 12 months following enrollment, Veteran participants received a phone call every 2 weeks to screen for COPD exacerbations, defined as worsening breathing symptoms that lasted more than 48 h. Veterans who experienced an exacerbation during the follow-up period were invited to participate in a qualitative interview about their experiences during the exacerbation.

Veterans who completed an interview were asked if they had a caregiver (defined as a family member or close friend involved in their COPD care). If so, the Veteran was asked for verbal permission for study staff to invite the caregivers for an interview. Of the 60 Veterans who participated in qualitative interviews, 26 provided names of caregivers. Caregivers were eligible if they were English-speaking, 18 years of age or older, had access to a telephone, and were able to give consent. Study staff contacted the caregivers, described the study, and obtained verbal informed consent; a waiver of documentation was obtained. Of the 26 caregivers identified, 24 were eligible and agreed to be interviewed. One caregiver was ineligible and one did not respond to phone calls.

Procedure

Caregivers participated in telephone-based, semi-structured qualitative interviews between February 2017 and February 2018. Interviews lasted 32–58 min, were digitally recorded, and professionally transcribed. Interviews were conducted by one master’s level researcher (J.Y.) and one bachelor’s level researcher (C.S.), both with extensive experience in qualitative research and data collection with Veteran populations.

The interview guide was structured to begin with broad, open-ended questions, followed by more specific questions and probes to elicit thorough, detailed descriptions of caregivers’ experiences with and involvement in Veterans’ COPD exacerbations. The caregiver interview guide mirrored the parent study’s Veteran interview guide, which was informed by Fortney’s Access to Care model [23] and the Leventhal Common Sense model [24] and included questions related to model domains such as coping, environmental and contextual factors, and symptom representation. Caregivers were asked to describe the patient’s recent and past exacerbations including care seeking and treatment received, caregiver involvement in exacerbations, caregiver coping, healthcare communication, and suggestions for supporting caregivers of Veterans with COPD (see Table A1 for an abbreviated Interview Guide. The complete guide is available upon request to study authors). Caregivers were provided $40 compensation for their participation in the study.

Data Analysis

Caregiver interviews were analyzed using inductive content analysis, an approach in which categories and themes are derived from the data through open coding, code grouping or categorization consistent with the steps outlined by Elo and Kyngäs [25]. Transcripts were closely reviewed by two experienced qualitative analysts (J.Y. and C.S.) in order to create an initial code list based on meaning units identified in the data. The analysts each applied the codebook to the same transcript then met to assess coding consistency, refine codes, and add new codes to the codebook. Discrepancies, such as inconsistent code application, were resolved through discussion and consensus building. This process was repeated until coding consistency was established, at which point remaining transcripts were coded independently. Analysts met regularly to review and refine the definition and application of codes. Codes and their attached data were sorted into categories based on similarities and differences within and across interviews and themes were identified based on patterns in the data. Analysis continued until saturation occurred at which point no new concepts were identified [26]. All data were coded using Atlas.ti qualitative software (Version 8) [27].

Strategies to enhance analytic rigor followed criteria suggested by Elo et al. [28] and Morse et al. [29], including going back and forth between the interview data, codes, themes, and categories to refine themes, ensure findings were grounded in the data, and validate results. Additionally, preliminary results, including code reports and themes, were reviewed by the entire study team at four time points during the analytic process to further refine themes, confirm face validity and credibility, and identify representative quotes for presentation. The study team included clinicians (pulmonology, nursing, and psychology) and health services researchers with expertise in COPD and family-centered management of chronic illnesses.

Results

We interviewed 24 caregivers; almost all were female (96%) and in a spousal/significant other relationship with the care recipient (92%). Two participants were adult children caring for a parent. All but one caregiver (an adult child) cohabitated with the care recipient. Care recipients were male with mean age 70.9 (±7.17), mean FEV1 1.58 (±0.64), and a mean mMRC dyspnea of 2.8 (±0.92) (Table A2).

Five primary themes and seven related subthemes related to the caregiver’s role during acute COPD exacerbations were derived through the analytic process (see Table A2). Results are presented by theme and include selected representative quotes.

Theme 1: Determining “What Is Happening” and “How Bad Will It Get”

Caregivers were able to provide significant detail regarding the onset, symptoms, course, and outcome of acute COPD exacerbations or “worse breathing episodes.” Caregivers reported consistently recognizing and being aware of changes to patients’ baseline functioning and identifying the onset of new symptoms: “I always can tell when something bad [exacerbation] might be coming on” (CG19).

Subtheme A: identifying and monitoring observable symptoms

Caregivers described identifying and monitoring observable symptoms or those “you can see, hear and measure,” such as difficulty breathing, coughing, sputum color, activity level, and temperature in order to assess symptom severity and predict the course of an exacerbation or “how bad it will get.” One caregiver (CG22) reported using temperature as an indication of episode progression, “I just keep taking his temperature to see if things are getting worse” while another (CG15) listened to the frequency and severity of coughing, “I listen to his cough, how rough it is, how often it is…that’s how I know what we’re up against.”

Subtheme B: being vigilant and on alert for changes

Many caregivers described a heightened vigilance that accompanied the onset of an exacerbation or a change in a patient’s observable symptoms. The course of an exacerbation was often unpredictable with some resolving without incident and others developing into “full blown” episodes that resulted in lung infections, visits to the ED, and/or hospitalization. Caregivers often reported being worried about how early symptoms would progress and described using frequent symptom assessment and intense watchfulness to determine, “what is really going on here?…Is it a blip or something we should really be worried about?” (CG18). Being alert for changes in symptoms and patient functioning allowed caregivers to identify when symptoms worsened to the point that action, such as medical care seeking, was needed. As one caregiver (CG8) explained, “I watch him all the time…when I see something coming on I watch him even closer, how he is breathing, how he is moving, to see where is this going…how bad is it going to get…when is it bad enough to do something and what should we do.”

Subtheme C: probing for more information

Monitoring a patient’s observable symptoms did not always provide enough information for caregivers to adequately evaluate symptom severity and determine next steps. Some caregivers reported needing to understand the patient’s internal experience during an exacerbation or “how he is feeling inside…how it feels to him, is it getting better or worse?” (CG17). However, caregivers explained that patients often failed to share how they were feeling or minimized exacerbation symptoms. This lack of disclosure often led caregivers to probe patients for additional information so that they would “not be in the dark” and would “have the whole picture” of the exacerbation. As one caregiver (CG16) described, “he’s not going to tell me what’s going on with him…so I’ve got to keep at him to tell me what is really going on…how he’s really feeling.”

Theme 2: “Watching” and “Witnessing” Elicits Fear, Distress, and Helplessness

Almost all caregivers reported intense emotional responses to observing patients’ symptom-related distress and often described feelings of fear and helplessness, especially when witnessing a patient’s struggle for breath and intense bouts of coughing: “When he has these horrible coughing spells, I don’t even know how to describe them, they are just terrible…and I almost can’t stand to listen to it…it’s so scary” (CG24). Fears most often focused on the possible outcomes of an episode, such as hospitalization or death, while helplessness was primarily related to not knowing what to do to ease symptoms and when, or if, to seek care. A few caregivers specifically described being afraid of being put in the position of calling emergency services if a patient collapsed or passed out. “He’s coughing to where it looks like he’s not taking in air, and he’s not able to breathe. It’s like he’s choking on something, his face gets so red. And I feel helpless in what I can do to help it, not knowing exactly what the best course of action is to do. That’s why it scares me, because if he passes out, I’d have to call 911” (CG23).

Caregivers also frequently described the ways in which watchfulness or vigilance during COPD exacerbations negatively impacted their quality of life. Needing to “watch him all the time” caused disruption to normal patterns of living such as work and other daily activities, necessitated being homebound with the patient, and often affected caregivers’ sleep. As one caregiver (CG20) explained, “When he’s like that [having problems with his breathing] I can’t really leave him alone so I’m at home all the time watching him…and I’m not getting much sleep ‘cause I’m checking on him at night.”

Theme 3: “We Don’t Always See Eye to Eye”: Caregiver–Patient Discrepancies

Caregivers commonly reported differences or discrepancies in how they and the patient perceived an exacerbation, including interpretation and evaluation of symptoms and if and when to seek care.

Subtheme A: evaluating symptoms more seriously than patients

Caregivers reported evaluating symptoms as more serious and concerning than patients. Although both caregivers and patients recognized observable symptoms like coughing or breathlessness, caregivers explained that they often viewed them differently than patients in two key ways: (a) assessing greater symptom severity and (b) interpreting symptoms to be evidence of worsening illness, underlying infection, or “bigger health problems.” Here a caregiver (CG19) compares her assessment of an episode of coughing with that of the patient: “Yeah, we both know he’s coughing, you can’t miss that. But it’s just that he doesn’t see it as bad as I do…Like the coughing, he’ll say ‘It’s just a cough’ but I think ‘that’s a really bad cough, that cough worries me that something worse is going on.’” Another caregiver (CG4) described differences in evaluation of sputum color as an indicator of need for medical care: “He’s coughing up sputum. Lately it’s been brown…if it’s anything other than clear I have the feeling that we need to do something about it, should go to the doctor, but that’s not his feeling.”

A few caregivers attributed these discrepancies to the gradual, progressive nature of COPD and suggested that as patients normalize increasingly poor breathing, they may be unable to accurately judge symptom or episode severity. As one caregiver (CG1) described, “What you and I think of as normal breathing, he doesn’t have that anymore…he no longer can recognize how bad he is getting. Often times he doesn’t realize it until he’s at the extreme end of things. That’s basically the difference between the two of us, I am outside of it and can see it more clearly than he does.”

Subtheme B: caregivers want to act but patients want to delay

Caregivers commonly described disagreeing with patients about when, or if, to seek care during an exacerbation. Caregivers consistently reported wanting their patients to seek care, such as going to the doctor, an urgent care center or the emergency room during exacerbations while patients often wanted to delay care or avoid care all together. This created a common dynamic of patients wanting to “wait it out” in the hope that symptoms would improve and caregivers wanting to seek care much earlier in the progression of an exacerbation. Caregivers attributed patients’ desire to delay or avoid care to psychosocial reasons such as stubbornness, gender norms (“typical male”), not wanting to recognize episode severity, and reluctance to ask for help or rely on others. As one caregiver (CG2) described, “He will get the onset of it and be struggling. I’ll offer several times ‘do you want to go in, do you want to go in?’ and his responses usually are ‘no I’m going to try this first, I’m going to do that, you have to work tonight and I don’t want to bother you.’” Another participant (CG7) explained, “[Patient] is just like any other male, he wants to put if off because he don’t want to see how bad it is…like just stick my head in the sand and it will be better…typical male.”

Conversely, caregivers described wanting to act or seek care earlier in order to “catch [the exacerbation] early,” thus avoiding “waiting too long” and allowing the episode to progress and symptoms to worsen. Many caregivers described encouraging care seeking in order to avoid worse outcomes, such as advanced illness, hospitalization, and death, or “crisis mode” which involved calling 911. Here, one participant (CG6) described her attempts to anticipate and identify worsening symptoms in order to encourage the patient to seek care before the episode worsens: “What I try to do is see it coming. I will try to catch it, and I encourage him to go in…so it doesn’t get into crisis mode.” Other caregivers described how their past experience with “worse outcomes” influenced their desire for earlier care seeking, “We’ve been down that road of pneumonia before and it’s never good…I always say, why don’t you just go into the doctor and get the medicine so that doesn’t happen again” (CG12). Some caregivers also described wanting to seek care to reduce their own fear, anxiety, and frustration during an exacerbation, “I just want him to get it taken care of so I can stop holding my breath at what will happen” (CG10).

It should be noted, two caregivers in spousal roles reported always “being on the same page” as their patient when it came to interpreting symptoms and the need for care seeking. These participants described their patients as accurately identifying serious or concerning symptoms and being proactive in symptom management and care seeking.

Theme 4: Caregivers Attempt to Influence Care Seeking But Must Maintain a “Delicate Balance”

When caregivers experienced a mismatch or discrepancy with patients, they described utilizing a range of approaches to influence earlier care seeking. Although caregivers most often reported the decision to seek care as the patient’s decision (“he decided”) or a collaborative decision (“we decided”), they commonly described their role as trying to influence earlier care seeking. This role involved a continuum of approaches increasing in how forcefully the caregiver attempted to insert themselves into the care-seeking decision—from minimal influencing behaviors (asking or suggesting care), to repeated or increased attempts to influence (pushing, nagging, or hounding), to “taking charge” of the decision to seek care (insisting, delivering ultimatums, making appointments, or calling clinicians). However, caregivers often acknowledged the limitations of their influence on patient behavior and described balancing their desire for care seeking with respect for patient autonomy and the potential negative ramifications of “pushing too hard.”

Subtheme A: utilizing a range of approaches: suggesting, nagging, and insisting

Caregivers commonly described suggesting care seeking in response to identifying concerning or worrisome exacerbation symptoms. In this approach, a caregiver’s influence was minimal and the patient was clearly responsible for the decision regarding when and if to seek care. As one participant (CG21) explained, “All I can do is make a suggestion…it’s up to him if he goes to the ER or not.” Another caregiver (CG5) described conveying her desire for care seeking by asking the patient, “Don’t you think it’s time to go to urgent care?” Typically a suggestion did not result in immediate care seeking and caregivers frequently described suggesting as “setting the stage” for care seeking rather than moving patients to care: “When I say, how about we go to the doctor, he almost always says no, but it puts it in his mind and gets him ready for the idea of going” (CG12). Caregivers also explained how time and exacerbation progression, combined with suggesting, ultimately motivated care seeking behaviors. “Well it’s not that I make him go [to the ER], I suggest that he go and then wait for him to come around to the idea…it takes a little time…he’s gotta see that it’s getting worse first” (CG3).

A second, more active approach involved repeatedly suggesting or asking the patient to seek care. Caregivers commonly referred to this approach as “nagging” or “wearing him down” with the goal of getting the patient to agree with caregiver’s assessment of the need for care. As one participant (CG14) described, “Well I am the wife. And I have opinions. And I have been known to nag. So I do sometimes nag him and say ‘look this has been going on too long, you need to do something about this…usually he’ll agree with me.’”

Finally, some caregivers described “driving” or “taking charge” of care seeking, by forcefully encouraging care seeking (insisting on care or delivering an ultimatum) or initiating care seeking by calling the doctor or making an appointment. This approach was the least commonly described and was typically employed only when the caregiver evaluated symptoms as potentially life threatening, believed the episode had persisted for too long, and/or their anxiety and fear pushed them to action. As one caregiver (CG9) explained, “His coughing got worse and worse and I was up all night worried about him. In the morning I said, ‘we’re going to the ER, I’m just not willing to take that risk.’ It wasn’t a choice anymore.”

Caregivers commonly described changing their approach over the course of a worsening exacerbation. As symptoms progressed and the duration of the exacerbation lengthened, caregivers reported utilizing increasingly influential or forceful approaches to affect care seeking. As one caregiver (CG1) explained, “At first it’s just, ‘don’t you think you should go?’ but if it isn’t getting any better, if I don’t see him starting to improve…then I start to push back and push harder.” Caregivers also described fears of negative outcomes, such as hospitalization and death, and past experiences of “waiting too long” as driving them to insist on or initiate care seeking: “If it’s not too bad yet, I may just say ‘Don’t you think it’s time to go to the doctor about this’…but as time goes on and his breathing gets worse I often will end up saying ‘it’s time, let’s not wait around any longer… I know what happens when we wait too long’” (CG5).

Subtheme B: balancing influence with patient role and reaction

Caregivers acknowledged that they faced limitations to their influence on patients’ decisions and described negative consequences of excessively urging patients to seek care. Many described trying to maintain a “delicate balance” between pushing care seeking and respecting patients’ autonomy, acknowledging that ultimately the patient was the one living with the illness. As one caregiver (CG4) explained, “I would have more visits to the ER, but I have to cool my jets to some extent too and say, ‘hey, not my circus, not my monkeys.’” Other caregivers described “choosing [their] battles” in order to avoid negative responses and interpersonal conflict that could occur as a result of disagreements about when to seek care. As CG13 explained, “It’s not worth a big fight and getting his breathing even worse” while another (CG3) shared, “If I keep on him too much [about going to the doctor] then it causes problems and he gets real mad with me….so I pick and choose.”

Theme 5: Caregivers Desire Information and Support

Participants commonly described wanting and needing information and support to help navigate and clarify their role as caregivers. Some caregivers had never talked to a clinician about the patient’s illness outside of an emergency situation and lacked basic knowledge about COPD, typical illness progression, prognosis, and how to manage exacerbation symptoms. Even caregivers who did have contact with their patient’s doctors often expressed that their role was “just to be a second set of ears” and that they did not feel they could ask questions openly and honestly. Many caregivers described themselves as lacking confidence during exacerbations and wanted instruction and guidance in “what can I do to help him…what should I do and not do and when is the right time to get help” (CG21). When asked what would improve the caregiver experience, many described wanting a resource they could contact during an exacerbation for information and support, “Somewhere that I could talk to a knowledgeable person, telling them the symptoms of what is transpiring and get their input as to what I should do at that time” (CG9). A few caregivers also underscored the importance of clinicians in clarifying and reinforcing when and where to seek care explaining, “If he could hear the doctor say it, that he needs to go when he gets coughing like that…maybe he’d listen to him” (CG8). One caregiver also described wanting her husband’s doctor to initiate a care-planning discussion with both of them together, so that “we can all be on the same page about when we should act and what we should do” (CG11).

Discussion

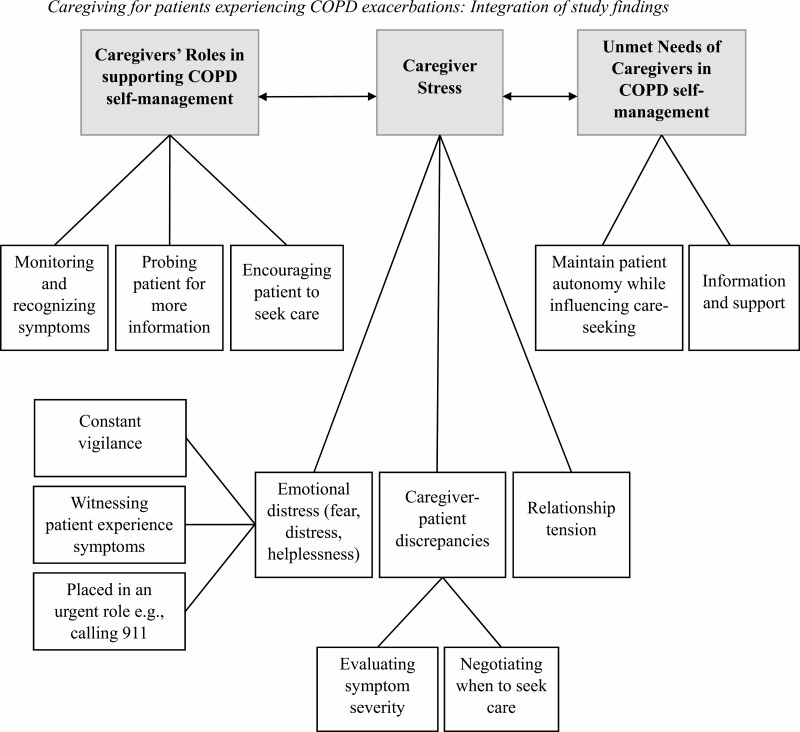

The significant caregiver burden associated with COPD coupled with the unpredictability of exacerbations highlight the importance of understanding caregivers’ roles and experiences during COPD exacerbation management. While there is growing attention to caregiving in COPD [30–32], less is known about the roles caregivers play in helping patients with COPD manage their illness and it is not sufficiently appreciated how the complex and unique challenges related to the caregiver role may result in delays in care during exacerbations. Our findings are illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Caregiving for patients experiencing COPD exacerbations: integration of study findings. COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Our study found that caregivers are attuned to and involved in COPD exacerbations. Through observation and probing patients for information about their symptom distress, caregivers are continuously alert for changes in symptomology. Our findings build upon other published study findings that caregivers of patients with COPD monitor patients’ symptoms and severity in order to facilitate adherence to COPD management and timely treatment [33]. Caregivers in our study often needed to probe patients for more information as monitoring observable symptoms was not always adequate in evaluating symptom severity. However, they reported that patients were often not forthcoming with their symptom experiences, which was challenging for caregivers’ attempts to determine symptom severity and evaluate the need for care. Patients not openly disclosing their symptoms has been found in other serious illnesses, such as cancer, and may be particularly related to patient–caregiver discrepancies in symptom evaluation or need for seeking care [34]. To the best of our knowledge, established programs assisting caregivers are not widely available in not only identifying COPD exacerbation symptoms early and evaluating the need for care, but also in learning approaches for negotiating the need for care with the patient. The caregivers in our study reported no knowledge or use of such programs.

Caregivers in our study noted caregiver vigilance as important to avoid missing crucial changes in patient’s symptoms, but it also carried with it perceived negative impacts on caregivers’ quality of life. The unpredictable nature of COPD exacerbations may be associated with the need for constant vigilance on the part of the caregiver. Prior studies have highlighted the significant effects of caregiving in COPD on quality of life, particularly identifying the caregiver–patient relationship as a primary predictor [35, 36]. However, our findings highlight a nuanced contributor to caregiver quality of life. Constant symptom surveillance may increase feelings of anxiety, stress, and uncertainty in the caregiver, and in conjunction with a decline in patients’ ADLs and independence as the disease progresses, may negatively affect caregiver quality of life and the relationship between the patient and caregiver.

Observing care recipient symptom distress evoked intense negative emotions, such as fear, anxiety, distress, and helplessness in the caregivers in our study, which they were sometimes reluctant to disclose to the patient. Emotional distress in caregivers of patients with COPD could be expected due to the constant threat of exacerbations, overt severity of symptoms, and negative outcomes associated with advancing illness, such as frequent hospitalization and death. One study that found that caregivers of patients with COPD feel helpless when witnessing the patient experience symptoms of acute exacerbation, such as severe breathlessness [33]. Our study similarly found that caregivers experienced fear and helplessness during acute COPD exacerbations and anxiety around knowing the best course of action. Caregivers may also experience emotional distress related to the possibility of needing to contact emergency services, fearing the patient would feel upset that 911 was called, or fearing they waited too long. A review by Grant et al. [37] found a need for further research pertaining to the psychological wellbeing of caregivers of patients with COPD due to a limited evidence-base in this area. Our findings elucidate contributors to such caregivers’ emotional experiences and a need for providing emotional support to minimize the anxiety, fear, and helplessness associated with caregiving during COPD exacerbations. Caregiver models of stress (e.g., Pearlin) [38] typically present intrapersonal factors or at best, the level of support needed by patients as key contributors to emotional distress and mental health problems in caregivers. However, we and others (e.g., Trivedi) [39] highlight that interpersonal factors are also important in co-managing serious illnesses, such as COPD.

The current study suggests that the role the caregiver plays in care seeking for COPD exacerbations is complex and caregivers may experience tension between their desire for action and the patient’s desire for waiting and monitoring. Caregivers in our study commonly reported evaluating symptoms more seriously than patients, which contributed to discrepancies in the perceived need for care seeking, such that caregivers often desired earlier care seeking than patients. Caregivers perceived positive benefit from action involving receipt of care, including improved patient health outcomes and reducing their own anxiety, but also wanted to respect the patient’s own agency. Caregivers in our study also reported concerns about the negative outcomes of waiting to seek care, such as hospitalization or death, and a desire to avoid these outcomes. Our study findings regarding discrepant perceptions of the need for care seeking are consistent with the evidence-base, which suggests that in caregiving of seriously ill patients, surrogate decision making by the caregiver regarding treatment seeking may not wholly represent patients’ preferences [40].

Caregivers in our study adjusted their approach to influence care seeking based on perceived symptom severity, anxiety, and perceived urgency, and approaches ranged from providing active encouragement to insisting the patient sought care. However, caregivers also perceived limitations to their influence on patient decisions to seek care and reported wanting to avoid possible negative emotional reactions and interpersonal conflict. Tension or conflict between the caregiver and patient may be expected due to well-documented discrepancies between caregiver and patient ratings of disease severity, where caregivers tend to perceive symptoms more severely than patients both in COPD and other medical illnesses [15, 41]. However, these studies do not explicate the relational impact of differing views between patient and caregivers. Our study findings elucidate how differing perceptions of COPD severity and the need for care may lead to relationship tension between patient and caregiver and how this tension may play out in whether the caregiver encourages the patient to seek care or is reluctant to do so.

Caregivers in our study consistently desired more information, specifically about what they can and should do during an acute exacerbation, and resources to contact for information and support during an exacerbation. Despite caregivers identifying support as integral to their care support system, unmet needs persist in gathering relevant information and emotional and practical support among caregivers of people with COPD [33, 42, 43]. These study findings suggest that caregivers are often in a position to influence earlier care seeking but may lack the necessary agency, knowledge, and support. Some caregivers in our study highlighted the role that clinicians can play not only in providing education, but also in reinforcing and directing care seeking, particularly with patients who are hesitant to seek timely care. Therefore, clinician-directed approaches that incorporate caregivers to address patient reluctance to seek care may be helpful.

Clinical programs advocating for a shared management approach are necessary to educate both the caregivers and patients on symptom recognition and when to seek care in order to foster more congruence between caregivers and patients. Supporting caregivers in defining their role about how and when they would be involved during exacerbations and involving patient–caregiver dyads in care-seeking decisions could help them develop more effective approaches to promoting care seeking with patients during acute exacerbations. In addition, supporting patient–caregiver dyads in setting collaborative care plans, including when and where to seek care would be beneficial to caregivers and could serve to influence earlier care seeking. Providing support to caregivers in defining their role and involvement in managing symptoms and seeking care could help reduce caregiver anxiety, increase confidence, and lead to timely care seeking [44, 45]. Given that some caregivers may not have contact with clinicians outside of emergency situations, caregivers may benefit from joining their patients during early care-planning discussions conducted by clinicians. Caregivers in other studies have reported that a lack of direct communication with patients’ healthcare providers have impeded their caregiving efforts [46]. Therefore, integrating caregivers in care plans earlier in illness progression may help increase their knowledge, perceived support, and confidence during acute exacerbations and reduce relational tension between caregiver and patient pertinent to when to seek care. Providing caregivers the same instructions and information that patients receive from providers could facilitate co-monitoring of symptoms from the same vantage point and developing a collaborative action plan that is communicated among the patient, caregiver, and healthcare providers. RAND describe a framework [47] for integrating caregivers into their patient’s healthcare team, including barriers and care coordination initiatives, that could be applied to caregiving in COPD. Such dyadic disease management coaching could also lead to patients being more open to input on care seeking from their caregivers, potentially resulting in earlier treatment during exacerbations, lower caregiver anxiety, and better relationship functioning. In addition to caregiver education, clinicians may also provide remote monitoring, decision support, or clinical consultation during an acute exacerbation to help patients and caregivers make more medically informed decisions about care seeking.

Existing pulmonology support programs are primarily aimed toward patients and do not involve or support caregivers. For example, certain VA settings offer both hospital- and home-based pulmonary rehabilitation programs for patients with COPD, where they receive education for self-management and medically supervised physical activity [48]. Such programs may consider involving the caregiver as part of the educational process to foster collaborative dyadic illness management. Caregiver-focused programs aimed at other medical illnesses may also be tailored for caregivers of COPD patients. For example, the Resources for Enhancing All Caregivers Health (REACH) program [49] is aimed at reducing caregiver stress and improving self-management of patient’s health through education, support, and skill-building interventions. The program currently offers disease-specific interventions for patients with dementia, spinal cord injury, multiple sclerosis, post-traumatic stress disorder, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, but currently does not have a COPD-focused intervention. Trivedi et al. [39] developed a couples-based self-management program for patients with heart failure, an illness that, like COPD, is characterized by frequent symptom exacerbations. Their study found improvements in patient–caregiver communication, relationship quality, self-management of heart failure, and caregiver psychological wellbeing and quality of life following participation in the program. A similar collaborative self-management program may be effective for those caring for COPD patients due to the analogous illness trajectory. Learning the nuanced roles and needs of caregivers of patients with COPD through qualitative studies such as ours could inform the development of focused caregiver support and education programs to navigate COPD exacerbations in a collaborative manner. Caregivers in our study did not know of or use caregiver support programs. Therefore, community outreach is also necessary to inform caregivers of available programs and facilitate their access to supportive programs and services.

This study has several limitations that may influence the interpretation and transferability of results. First, caregiver sociodemographic data, such as age, education, race, or ethnicity, were not collected so we were unable to fully characterize our sample. Our sample was based on convenience of caregivers identified by Veterans in the parent study which may have led to selection and inclusion bias. More purposive sampling of caregivers may have led to a wider variety of experiences and, ultimately, different findings. Also, our sample was largely homogenous in gender, spousal relationship, and cohabitant status and only included caregivers of Veterans, all of which may affect the variability of experiences that were captured. Future studies may study the interactions between gender, relationship, perceived and actual health status in COPD patients and their caregivers. Future work would also benefit from research with more diverse, purposeful samples. We were unable to obtain feedback on our findings from study participants via member checking or a similar respondent validation process. Future studies may benefit from working more actively with caregivers to follow up on results.

Despite these limitations, this qualitative analysis allowed for a deeper understanding of caregivers’ experiences and roles during acute COPD exacerbations and care-seeking decisions. Additional research is needed to understand how to provide necessary support and education for caregivers during acute exacerbations. Future studies with more diverse samples should examine how patient or caregiver gender may play a role in the caregiving experience for patients with COPD. Future research may explore ways to help caregivers promote care seeking with patients during exacerbations while respecting patient autonomy could increase caregiver confidence, improve caregiver quality of life and emotional wellbeing, and facilitate more timely treatment. Further, relational tension between caregiver’s needs and patient’s needs calls for interventions that focus on improving communication, goal setting, and collaborative treatment planning, including identifying serious symptoms, and planning when, where and how to seek care. Additional research is needed to understand the role of clinicians in working with patient–caregiver dyads to promote shared understanding of COPD, symptoms, and when to seek care. Clinicians may use evidence-based tools in palliative care to facilitate development of a care plan that is agreed upon by the patient, caregiver, and clinician in order to foster shared decision making, reduce uncertainty, and instill confidence in caregivers ahead of acute exacerbations [50]. Educating, supporting, and involving caregivers in the management of COPD exacerbations has the potential to decrease their fear and anxiety, increase their confidence in encouraging care seeking, and ultimately reduce delays of care.

Funding

This study was funded by a grant IIR 14-060-3 awarded to Dr. Fan from the Veteran Affairs Health Services Research and Development Service (VA HSR&D). Dr. Trivedi was partially supported by a CDA-09-206 from the VA HSR&D.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the participants of this study for sharing and permitting us to report on their experiences. Views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the US Government, Department of Veterans Affairs, or Palo Alto University.

Appendix

Table A1.

Interview guide questions

| Main questions |

| Tell me about [patient’s] most recent exacerbation. |

| Please describe, in as much detail as you can, what happened during the exacerbation |

| Tell me about any emotions you may have had during the exacerbation. |

| Tell me about deciding to seek (or not seek) care. |

| Tell me about [patient’s] past exacerbations, if any. |

| How does the patient communicate with you about his COPD or COPD symptoms? |

| What suggestions do you have for [patient]? |

| Follow-up questions and probes |

| Tell me about how the exacerbation started. |

| What symptoms did you notice? |

| How long did the exacerbation last? |

| What happened next? |

| How were you involved? |

| What were you thinking? |

| What were you feeling? |

| What did you think would happen? |

| What do you mean by… |

| Give me an example of… |

| Walk me through… |

| Tell me more about… |

Note. This list is not exhaustive but highlights questions most germane to this study and analysis. Complete interview guides are available through correspondence with the author. COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Table A2.

Demographics of Veteran care recipients (n = 24)

| N (%) | M (SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Age | 70.9 (7.17) | |

| Male gender | 24 (100.0) | |

| COPD severity | ||

| FEV1 (liters) | 1.58 (0.64) | |

| FEV1 % predicted | 49.9 (20.1) | |

| FEV1 % predicted by severity category | ||

| ≥80% (mild) | 3 (12.5) | |

| 50–79% (moderate) | 8 (33.3) | |

| 30–49% (severe) | 10 (41.7) | |

| 0–29% (very severe) | 3 (12.5) | |

| mMRC | 2.8 (0.92) | |

| Reported moderate or severe exacerbations in year prior to enrollment | 2.8 (2.11) |

COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Authors’ Statement of Conf lict of Interest and Adherence to Ethical Standards Dr. Trivedi is an associate editor for ABM. Dr. Fan has received grants from Veterans Affairs, National Institutes of Health, Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), Firland Foundation, Washington State Life Sciences Discovery Fund Authority, and the National Center for Palliative Care Research. No other conflicts of interest to declare.

Authors’ Contributions

M.S. took the lead in writing the manuscript. J.Y. was responsible for data collection, analysis and interpretation, and assisted with writing and reviewing the manuscript. V.F. was the principal investigator for the study; he conceptualized the study, oversaw data collection, analyses and regulatory issues. C.B., T.L.S. and J.C.F. were co-investigators for the study and provided feedback on the conceptualization of the study question and the manuscript. C.S. and E.R.L. assisted with data collection and reviewing the manuscript. R.T. was a co-investigator for the study and assisted with writing and reviewing the manuscript.

Ethical Approval All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- 1. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Published online 2018. Available at https://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/GOLD-2018-v6.0-FINAL-revised-20-Nov_WMS.pdf. Accessibility verified June 25, 2020.

- 2. Annegarn J, Meijer K, Passos VL, et al. ; Ciro+ Rehabilitation Network . Problematic activities of daily life are weakly associated with clinical characteristics in COPD. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13(3):284–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kim YJ, Lee BK, Jung CY, et al. Patient’s perception of symptoms related to morning activity in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the SYMBOL Study. Korean J Intern Med. 2012;27(4):426–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wise R. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Merck Manual Professional Version. Published online 2020. Available at https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/pulmonary-disorders/chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-and-related-disorders/chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-copd. Accessibility verified July 20, 2020.

- 5. Villarroel MA, Blackwell DL, Jen A. Tables of summary health statistics for U.S. adults: 2018 National Health Interview Survey.National Center for Health Statistics. Published online 2019. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/SHS/tables.htm. Accessibility verified July 20, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 6. World Health Organization. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Published online 2017. Available at https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-(copd). Accessibility verified July 1, 2020.

- 7. Mannino DM, Higuchi K, Yu T-C, et al. Economic burden of COPD in the presence of comorbidities. Chest. 2015;148(1):138–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Foster TS, Miller JD, Marton JP, Caloyeras JP, Russell MW, Menzin J. Assessment of the economic burden of COPD in the U.S.: a review and synthesis of the literature. COPD. 2006;3(4):211–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. NHLBI. COPD. Published online 2019. Available at https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/copd. Accessibility verified July 20, 2020.

- 10. Qureshi H, Sharafkhaneh A, Hanania NA. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations: latest evidence and clinical implications. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2014;5(5):212–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Calverley P, Pauwels Dagger R, Löfdahl CG, et al. Relationship between respiratory symptoms and medical treatment in exacerbations of COPD. Eur Respir J. 2005;26(3):406–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gysels M, Higginson IJ. Access to services for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the invisibility of breathlessness. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;36(5):451–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gautun H, Werner A, Lurås H. Care challenges for informal caregivers of chronically ill lung patients: results from a questionnaire survey. Scand J Public Health. 2012;40(1):18–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Trivedi RB, Bryson CL, Udris E, Au DH. The influence of informal caregivers on adherence in COPD patients. Ann Behav Med. 2012;44(1):66–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nakken N, Janssen DJ, van den Bogaart EH, et al. Informal caregivers of patients with COPD: Home Sweet Home? Eur Respir Rev. 2015;24(137):498–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Giacomini M, DeJean D, Simeonov D, Smith A. Experiences of living and dying with COPD: a systematic review and synthesis of the qualitative empirical literature. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2012;12(13):1–47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Adelman RD, Tmanova LL, Delgado D, Dion S, Lachs MS. Caregiver burden: a clinical review. JAMA. 2014;311(10):1052–1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dalton J, Thomas S, Harden M, Eastwood A, Parker G. Updated meta-review of evidence on support for carers. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2018;23(3):196–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bove DG, Zakrisson AB, Midtgaard J, Lomborg K, Overgaard D. Undefined and unpredictable responsibility: a focus group study of the experiences of informal caregiver spouses of patients with severe COPD. J Clin Nurs. 2016;25(3–4):483–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jácome C, Figueiredo D, Gabriel R, Cruz J, Marques A. Predicting anxiety and depression among family carers of people with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Int Psychogeriatr. 2014;26(7):1191–1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pinto RA, Holanda MA, Medeiros MM, Mota RM, Pereira ED. Assessment of the burden of caregiving for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med. 2007;101(11):2402–2408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Doyle L, McCabe C, Keogh B, Brady A, McCann M. An overview of the qualitative descriptive design within nursing research. J Res Nurs. 2020;25(5):443–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fortney JC, Burgess JF Jr, Bosworth HB, Booth BM, Kaboli PJ. A re-conceptualization of access for 21st century healthcare. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(suppl 2):639–647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Leventhal H, Phillips LA, Burns E. The Common-Sense Model of Self-Regulation (CSM): a dynamic framework for understanding illness self-management. J Behav Med. 2016;39(6):935–946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(1):107–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Saunders B, Sim J, Kingstone T, et al. Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual Quant. 2018;52(4):1893–1907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Muhr T. ATLAS.Ti (Version 8) [Computer Software]. Berlin, Germany: ATLAS.ti GmbH; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Elo S, Kääriäinen M, Kanste O, Pölkki T, Utriainen K, Kyngäs H. Qualitative content analysis. SAGE Open. 2014;4(1):215824401452263. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Morse JM, Barrett M, Mayan M, Olson K, Spiers J. Verification strategies for establishing reliability and validity in qualitative research. Int J Qual Methods. 2002;1(2):13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mansfield E, Bryant J, Regan T, Waller A, Boyes A, Sanson-Fisher R. Burden and unmet needs of caregivers of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients: a systematic review of the volume and focus of research output. COPD. 2016;13(5):662–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Miravitlles M, Peña-Longobardo LM, Oliva-Moreno J, Hidalgo-Vega A. Caregivers’ burden in patients with COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:347–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Noonan MC, Wingham J, Taylor RS. ‘Who Cares?’ The experiences of caregivers of adults living with heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and coronary artery disease: a mixed methods systematic review. BMJ Open. 2018;8(7):e020927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hynes G, Stokes A, McCarron M. Informal care-giving in advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: lay knowledge and experience. J Clin Nurs. 2012;21(7–8):1068–1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kurtz ME, Kurtz JC, Given CC, Given B. Concordance of cancer patient and caregiver symptom reports. Cancer Pract. 1996;4(4):185–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bergs D. “The Hidden Client”—women caring for husbands with COPD: their experience of quality of life. J Clin Nurs. 2002;11(5):613–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pinto RA, Holanda MA, Medeiros MM, Mota RM, Pereira ED. Assessment of the burden of caregiving for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med. 2007;101(11):2402–2408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Grant M, Cavanagh A, Yorke J. The impact of caring for those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) on carers’ psychological well-being: a narrative review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49(11):1459–1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pearlin LI, Mullan JT, Semple SJ, Skaff MM. Caregiving and the stress process: an overview of concepts and their measures. Gerontologist. 1990;30(5):583–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Trivedi R, Slightam C, Fan VS, et al. A couples’ based self-management program for heart failure: results of a feasibility study. Front Public Health. 2016;4:171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fried TR, Bradley EH, Towle VR. Valuing the outcomes of treatment: do patients and their caregivers agree? Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(17):2073–2078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Janssen DJ, Spruit MA, Wouters EF, Schols JM. Symptom distress in advanced chronic organ failure: disagreement among patients and family caregivers. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(4):447–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Burton AM, Sautter JM, Tulsky JA, et al. Burden and well-being among a diverse sample of cancer, congestive heart failure, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease caregivers. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012;44(3):410–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Currow D, Ward A, Clark K, Burns C, Abernethy A. Caregivers for people with end-stage lung disease: characteristics and unmet needs in the whole population. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2008;3(4):753–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Aasbø G, Rugkåsa J, Solbrække KN, Werner A. Negotiating the care-giving role: family members’ experience during critical exacerbation of COPD in Norway. Health Soc Care Community. 2017;25(2):612–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Figueiredo D, Gabriel R, Jácome C, Marques A. Caring for people with early and advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: how do family carers cope? J Clin Nurs. 2014;23(1–2):211–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Trivedi RB, Slightam C, Nevedal A, et al. Comparing the barriers and facilitators of heart failure management as perceived by patients, caregivers, and clinical providers. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2019;34(1):399–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Friedman EM, Tong PK.. A Framework for Integrating Family Caregivers into the Health Care Team. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 48. VA Boston Healthcare System. Cardiac and Pulmonary Rehabilitation. Washington, DC.: U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. [Google Scholar]

- 49. VA Caregiver Support. REACH VA Program. Washington, DC.: U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Published online May 19, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Austin CA, Mohottige D, Sudore RL, Smith AK, Hanson LC. Tools to promote shared decision making in serious illness: a systematic review. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(7):1213–1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]