This paper presents exploratory data on occupational stress in restaurants prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic. In-depth interviews, biomarker data, and questionnaire responses identified salient factors to occupational stress. Findings highlight structures of the restaurant industry that contribute most to ill health and can inform more healthful and equitable practices.

Keywords: COVID-19, food service, occupational stress, restaurant

Objective:

This exploratory study investigated occupational stress in restaurant work prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods:

The study was a mixed methods design conducted in two phases with biomarker data for stress, questionnaire data, and semi-structured interviews.

Results:

Results indicated elevated stressors elevated stress during normal shift conditions (P < 0.05), low job satisfaction, an effort to reward imbalance (P < 0.05), and the majority (72%, n = 28) of participants reporting discrimination at least a “few times a year.” Interview data revealed four interrelated occupational stressors including: (1) financial hardships; (2) increased exposure to occupational health risks during the reopening phases; (3) increased workloads due to inadequate staffing and fewer hours; and (4) social and psychological pressures and ill treatment.

Conclusion:

These elements were reported prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and have persisted throughout with heightened impacts.

In the United States there were over one million restaurants with nearly 13.5 million jobs, making food service one of the largest workforce sectors in the nation prior to the COVID-19 pandemic.1,2 Since the pandemic, the food service industry has lost nearly 3.1 million jobs, expected revenues are down by over 36%, and more than 110,000 restaurants have or are projected to permanently close due to the economic fallout.3,4

Even without the economic stress of a global pandemic, the food service industry has been a difficult place to work with long hours in cramped, hot, and loud environments in which people earn low salaries, have high turnover, and their hours and salary vary significantly from week to week.5 Considerably diverse, the restaurant industry is among the largest employers of low-wage workers with well over 50% of its employees from historically marginalized groups including people of color, undocumented immigrants, refugees, women, and the formally incarcerated.6,7 For these reasons, the economic fallout of the global pandemic has impacted restaurant workers disproportionately leading to higher rates of financial insatiability and poor mental health.8,9

Occupational health risks due to lacking safety measures and regulatory oversight have also for a long time characterized the restaurant industry which is ranked third overall for injuries and fifth for injuries resulting in time away from work.10 These relatively high rates need to be examined against the backdrop of the United States economy which has been characteristically described as neoliberal. Neoliberal policies emerged as a set of guidelines controlled by the private sector and as a political ideology, neoliberalism stresses the deregulation of worker protections.11,12 In the restaurant industry, stressing individual accountability and the privatization of publicly managed assets, individuals are held responsible for their sense of well-being and security and customers or “the market” control of workers’ wages and livelihood.13 The restaurant industry has played an important role in the expansion of neoliberalism overall, as the growth in precarious work schedules and multiple job holders has coincided with a steady increase in the percentage of the family food budget spent on food prepared outside the home.14

The problems with policies and environments based in these economic structures have been laid bare during the COVID-19 pandemic as vulnerable worker populations have suffered disproportionately.15 The lack of the basic health protections such as employer sponsored health insurance and paid time off has complicated the industry's response to the pandemic and contributed to the existing inequities in occupational health.16 Furthermore, the minimal health and safety guidance from the federal government has led to the reliance on individual owners, workers, and customers to design, implement, and enforce protective reopening plans which has exacerbated the existing occupational health hazards.17,18

The pandemic's impact on restaurant worker is evident from worsening mental health, elevated exposure to COVID-19, and lack of safety protections.8,19,20 However, the extent to which working in the food service industry will exacerbate the experience of the pandemic and in returning to work remains unclear. This study examines the factors associated with occupational stress in the restaurant industry and how they have changed during the COVID-19 pandemic.

METHODS

Study Design

The objective of this study was to explore occupational stress in the restaurant industry and identify potential contributing factors. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent shutdown of restaurants, the initial study was halted, and research efforts were redirected to assess occupational stress during the pandemic. This resulted in a study with two phases—Phase 1 was a mixed methods design followed by Phase 2 which was a qualitative design the results of which were combined at analysis.21 Phase 1 captured quantitative and qualitative data on occupational stress during typical restaurant work and Phase 2 was designed to give voice to stressors experienced by workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. This study was conducted in collaboration with the Restaurant Opportunities Centers-United, a nonprofit organization advocating for improved working conditions for restaurant workers, who supported recruitment and provided oversight on the project development and implementation (Restaurant Opportunities Centers United, 2021).

Data Collection

Both phases of this study targeted individuals who worked in the restaurant industry in Chicago, Illinois that were at least 18 years or older, English or Spanish speaking, and employed or recently employed in the food service industry. The sample populations were unique to each phase with no participants included in both phases. The original design of Phase 1 had a target population of 120 individuals but was stopped at a sample size of 39 in March of 2020 due to the shelter in place orders resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic that closed all restaurants in Illinois. Phase 2 was designed to conduct interviews until data saturation was reached. Phase 1 employed convenience and snowball sampling to recruit through social media and the local restaurant industry with a screener survey used to recruit a representative distribution of participants. Purposive sampling was used for Phase 2 and participants were recruited primarily through membership in the Restaurant Opportunities Center of Chicago. Both Phase 1 and Phase 2 were approved by the Internal Review Board of the researchers’ academic institution.

Phase 1 data were collected in January through March of 2020 prior to the COVID-19 pandemic reaching the United States. In this portion, saliva samples were collected to measure participant cortisol levels during a typical work experience, which is a commonly used biomarker of stress.22 Two samples of saliva were collected through a self-administered cotton swab and taken before and after the participant's shift working at the restaurant. The shift length and start and end times varied depending on the participant. Participants met with research staff prior to sampling during which sampling protocol was explained and participants were given instructions including visual depictions of how to administer the swabs for collection. Sampling instructions can be found in Appendix A. Samples were analyzed for cortisol concentration by a third-party laboratory in duplicate, the average of which is reported in nanomole (nmol) per liter (L) of saliva (Salimetrics, State College, PA).

Also, during Phase 1, an occupational stress questionnaire was self-administered prior to the saliva sample collection. The questionnaire was comprised of three validated surveys on occupational stress, job satisfaction, and stress related to discrimination as well as basic demographic questions including race, income, and gender and sexual identity, health status information, and work-related questions such as position in the restaurant, pay structure, and benefits information. More detailed information about the validated surveys used in the questionnaire can be found in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Validated Scale Measures of Stress

| Variable | Facet | Questions∗ | Possible Score† | Cronbach's α‡ |

| Job Descriptive Index§ | Coworkers | 6 | 0 to 18 | 0.731 |

| A measure of job satisfaction with six facets including coworkers, the work itself, pay, promotion potential, coworkers, and supervision. Responses were limited to Yes, No, or Cannot Decide. The higher the score, the more positive the work experience. | Job in General | 8 | 0 to 24 | 0.818 |

| Work | 6 | 0 to 18 | 0.793 | |

| Pay | 6 | 0 to 18 | 0.850 | |

| Promotion Potential | 6 | 0 to 18 | 0.784 | |

| Supervision | 6 | 0 to 18 | 0.703 | |

| Effort Reward Imbalance|| | Effort | 6 | 4 to 24 | 0.568 |

| A measure of how the rewards such as promotion, job security, and respect compare to the efforts put into the work such as responsibility, overtime, and pressure. Responses were a four level likert scale: Strongly Agree, Agree, Disagree, Strongly Disagree. Ratio value with Effort over Reward and a score above one indicates that effort exceeds the rewards. | Reward | 11 | 11 to 44 | 0.816 |

| Everyday Discrimination Scale¶ | Experiences | 9 | 9 to 45 | 0.856 |

| A measure of experiences of discrimination as perceived by the respondents. Responses were a five level likert scale from Never to Almost Everyday. The higher value the more frequent the discrimination. |

Correction factors were applied when necessary to equally weight each facet of the questionnaire.

Scale responses were coded to numeric values and reverse coded when appropriate.

Scores above 0.50 are considered acceptable.

Brodke et al.25

Siegrist J, Starke D, Chandola T, et al. The measurement of effort–reward imbalance at work: European comparisons. Soc Sci Med 2004, 58:1483–1499.

Williams DR, Yan Yu, Jackson JS, Anderson NB. Racial differences in physical and mental health: socio-economic status, stress and discrimination. J Health Psychol. 1997; 2(3):335–351.

Phase 2 data were collected in February of 2021 in the beginning of the second year of the pandemic. Semi-structured interviews were administered using open-ended questions about employment experiences, potential biases at work, and the treatment of restaurant workers prior to and since the pandemic. There was a total of 50 questions with broad open-ended questions followed by probes for more specific information as part of a larger qualitative assessment of restaurant work. The interviews were conducted by university student researchers as part of a community-based practice course who were trained in qualitative methods of data collection. All interviews were conducted with the aid of zoom technology in English or Spanish. The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed to ensure accuracy. Only pseudonyms were used in order to protect participant identities and their privacy.

Data Analysis

In analysis of Phase 1 data, average salivary cortisol levels were analyzed for normality and outliers. Sensitivity analysis showed no significant outliers. Data were not normally distributed as indicated by the Shapiro-Wilk test and therefore log transformed to achieve normality (P > 0.05). Statistical analysis was run using SPSS (Version 27, IBM, Armonk, NY). Descriptive statistics were calculated for sample demographics and summary data of the outcome measures. Pearson correlation was used to determine association between various measures. To test for differences in the mean outcome measures, a series of General Linear Models were computed along with independent and paired t tests as well as Chi-squared tests for independence.

In Phase 2 analysis, participant narratives were organized using the Grounded Theory to identify categories of meaning derived from raw data.23 A shortened process was used including data gathering, creation of categories, and their subsequent relationships to one another, data coding, and development of a tentative explanatory framework through cultural analysis. There were 12 coders who reviewed the interview data to identify patterns which were further analyzed by the research team. Analysis broadly examined responses to questions about employment experiences, potential biases at work, the treatment of restaurant workers prior to and since the pandemic.

Phase 1 and Phase 2 data were analyzed jointly to identify the most salient themes within the two different time frames and used to explore which factors of occupational stress were present before the pandemic and persisted after. The data are presented jointly to support this combined understanding of the overall data results and is exploratory in nature.

RESULTS

Participant Overview

All participants worked in the restaurant industry in Chicago before the COVID-19 pandemic and some had been working throughout the pandemic. The specific demographics are identified in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Frequency Distribution of Participant Work Characteristics

| Variable | Phase 1 (n = 39) Frequency (%) | Phase 2 (n = 24) Frequency (%) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 24 (62%) | 9 (38%) |

| Female | 14 (36%) | 14 (58%) |

| Non-binary | 1 (3%) | 1 (4%) |

| Identify as LGBTQ | ||

| Yes | 7 (18%) | 2 (8%) |

| No | 31 (80%) | 22 (92%) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White | 13 (33%) | 15 (68%) |

| Black/African American | 9 (23%) | 1 (5%) |

| Hispanic/LatinX | 6 (15%) | 6 (27%) |

| Asian | 3 (8%) | 0 (0%) |

| Multiracial | 8 (21%) | 0 (0%) |

| Annual income | ||

| Low income (<$40,000 annually) | 20 (53%) | N/A |

| Mid-high income (<$40,000 annually) | 18 (47%) | N/A |

| Position in the restaurant | ||

| Front of house | 26 (67%) | N/A |

| Back of house | 7 (18%) | N/A |

| Management | 5 (13%) | N/A |

| Received a portion of wage through tips | ||

| Yes | 8 (21%) | N/A |

| No | 30 (79%) | N/A |

Overview of Occupational Stress

Phase 1 data indicate that restaurant workers often have relatively high levels of stress associated with work. The average cortisol measurement was 6.13 nmol/L (CI95%: 4.80, 7.47 nmol/L) which was higher than the non-stressed adult baseline of 1.8 nmol/L (one sample t test: P < 0.05).24 Due to variability in cortisol levels with some participants increasing in measured stress during the shift while others decreased, it was not possible to analyze the change in cortisol during the shift. Average cortisol levels were used in subsequent analysis as an overall measurement of stress during a typical work shift.

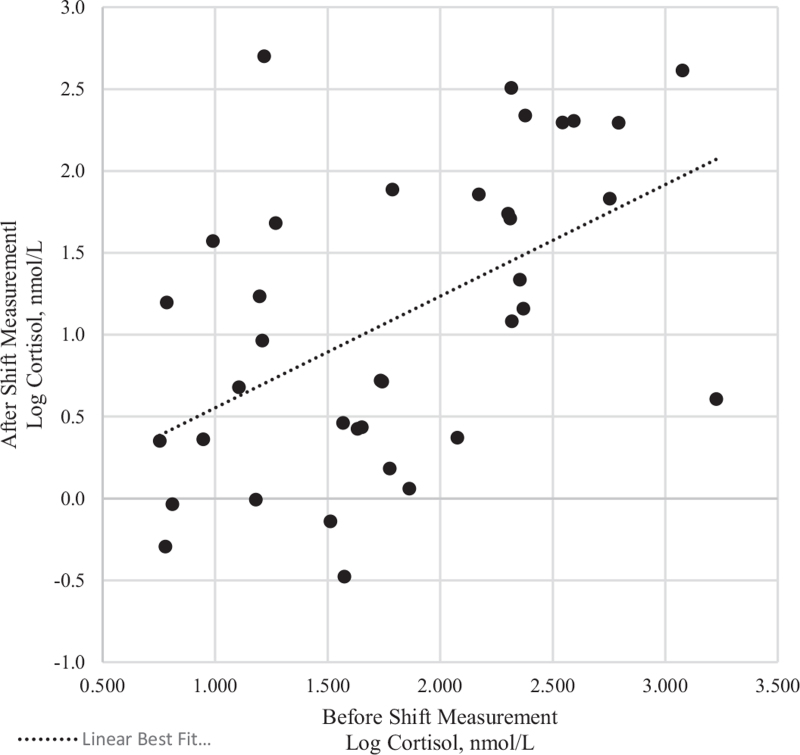

As seen in Fig. 1, response patterns are constant across individuals as participants with lower before shift response tended to have lower after shift responses and vice versa. There was a significant difference between participants with average cortisol levels below and above the mean confirming the observed clustering within the lower left and upper right quadrants in Fig. 1 (independent sample t test: P < 0.05). This difference was not associated with race, sex, or income (χ2 > 0.05). Due to the small sample size, it was not possible to assess the impact of the tipped wage or position in the restaurant on average stress levels.

FIGURE 1.

Scatterplot of cortisol measures before and after a shift at the restaurant.

Results of the questionnaire measures of occupational satisfaction, effort and reward, and discrimination can be found in Table 3. The job descriptive index (JDI) is comprised of five facets of the job and compares respondent satisfaction with each facet. As seen in Table 3, respondents ranked coworkers as having the most positive impact on job satisfaction whereas pay and promotion potential were ranked the lowest. In comparison to the general public, all of the facet scores were below the 50th percentile indicating a low positive experience in restaurant work as compared with other occupations.25

TABLE 3.

Results of Stress Outcome Measures from Job Descriptive Index, Effort Reward Imbalance, and Everyday Discrimination Scale (n = 38)

| Measure | Mean | 95% Confidence Interval |

| Job descriptive index | 53.9 | 46.3–61.5 |

| Coworkers facet | 12.3 | 10.9–13.8 |

| Job in general facet∗ | 10.5 | 8.83–12.2 |

| Supervision facet | 9.29 | 7.48–11.1 |

| Work facet | 8.76 | 6.85–10.7 |

| Pay facet | 7.45 | 5.39–9.50 |

| Promotion potential facet | 5.53 | 3.78–7.27 |

| Effort reward imbalance | 1.18 | 1.07–1.29 |

| Effort facet∗ | 31.4 | 29.8–33.0 |

| Reward facet | 28.1 | 26.6–29.7 |

| Everyday discrimination scale | 25.5 | 23.0–28.0 |

Values were multiplied by a correction factor to equally weight the responses.

Phase 2 data revealed several trends in restaurant work that had been amplified during the pandemic. Broadly, these structural factors were related to pay, benefits and paid time off, and the interpersonal dynamics of the industry. Interview data showed that these factors exaggerated the health risk and occupational stress of the workers interviewed. There was also a distinct workplace hierarchy between workers in different positions in the restaurant and between customers and service staff. This hierarchy, both perceived and tangible, influenced pay differentials and experiences of abuse which were again, heightened during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lastly, the interviews showed that work environment was paramount to the work experience especially during the COVID-19 pandemic with safety protocols influencing mental and physical health and support from management and a sense of community within the industry alleviating some of these pressures.

Thematic Analysis

Together Phase 1 and Phase 2 data uncovered increased stressors that either sustained or were heightened during the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, our findings revealed interrelated occupation stressors including: (1) financial hardships; (2) increased exposure to occupational health risks; (3) increased workloads due to inadequate restaurant staffing; and (4) social and psychological pressures and ill treatment of restaurant employees by management and customers.

Financial Hardships

Even before the pandemic, many of the participants reported financial hardships that impacted stress differentially. In Cook County, Illinois a family of four is considered very low income if they earn less than $46,600.26 Over half of the participants reported household earnings less than $40,000 per year (52.6%, n = 20) with a quarter of participants making between $30,000 and $39,999 annually (26.3%, n = 10). Job satisfaction levels as measured through the JDI were lower in low-income workers with an average JDI score of 46.8 (CI95%: 35.8, 57.7) as compared with mid and high-income workers at 61.5 (CI95%: 50.8, 72.2). There was a significant difference in measured stress between workers identified as low income and those with mid or high income above $40,000 per year (independent t test: P < 0.05) and a marginally significant difference in job satisfaction (independent t test: P = 0.053). Biological stress levels were lower for low-income workers at 4.73 nmol/L (CI95%: 3.29, 6.17 nmol/L) as compared with mid or high-income workers (CI95%: 5.37, 10.2 nmol/L).

In interviews, most of the participants (n = 22) discussed financial hardships. Some of the financial difficulties where due to layoffs and some individuals in receiving unemployment for the first time in their lives. Other financial hardships were due to receiving fewer tips as there were fewer customers during the pandemic. Although unemployment was associated with shame for some, undocumented workers were not eligible for unemployment. Furthermore, laid-off employees who were able to return to work often had reduced hours resulting in less financial stability. Another common response from former salaried employees who were able to return to work part-time was frustration of being demoted to sub-minimum tip-wages.

Layoffs did not only effect individuals but entire families, especially those with dependents. A 25-year-old college graduate explained:

I’ve been on furlough for majority of this year, my boyfriend he is a chef at the … group as well, so he was furloughed for a long time but then he was brought back and he isn’t making nearly as much money so he's been affected financially, I’ve been affected financially … [we are all] making less money because we’re not there as much as we normally would and it's all hourly pay, so.

Layoffs of undocumented workers presented even greater financial risks. As one interviewee explained:

I think they [undocumented workers] have been affected negatively. I think a lot of people in general struggled with getting unemployment.

These lived experiences are in contrast to the experiences of those workers with greater financial security and support networks. Some even saw their lay-off as an opportunity to decompress, a testament about how the stress that marks the industry is intersectional. A White US citizen in his 30s explained:

I would say, just strictly speaking about my habits and my way of life, I would say COVID was probably pretty good for me. Working in restaurants is really hard on your mental health and has a really big like drinking and hanging out after a really stressful shift is a really common occurrence. […] I think, even though everything is strange, and I don’t always know if I’m going to have enough money for this month or whatever, I would say that mentally, I’m in a much better place not working in a restaurant.

Another interviewee further explained that for many people in her community earnings are not only their own but financial contribution to, as in her case, the multi-generational household in which she resides leaving her little choice in her return to work.

Health Risks

Prior to the pandemic, respondents reported relatively good physical and mental health. Fifteen percent (n = 3) of respondents did not report good physical health and 25% (n = 8) of respondents did not report good mental health. The majority of respondents (72%, n = 26) were non-smokers, however 78% (n = 28) reported binge drinking 5 or more days a month which is considered excessive.27

During the pandemic, there was a marked increase in health concerns. Even still, many participants (n = 20) reported needing to remain at their job despite the greater risks posed by the COVID-19 virus. All 24 workers interviewed expressed concern about occupational risks associated with working during the pandemic.

Participants were asked how safe they felt continuing to work. One female Latina interviewee responded:

Not indoors, not with people sitting at tables without masks, chatting and eating, like, everyone that I know doesn’t feel ready to go out and eat, they’re also not hanging out with friends very much, so the people that are going out to eat are the ones who are already taking the most risks, like you know that inherently, so it doesn’t feel good on any level to me.

Restaurant owners typically decided how close the COVID safety precautions were followed or if at all. Yet owners, as one interviewee put it, “…don’t really work anyway, they just like own, … so they just telling others what to do.” This power imbalance coupled with the ambiguity in health and safety protocols added to the stressors experienced during the pandemic. Another interviewee explained:

… the owners normally they don’t know what's going on and they have a different treatment of the worker. Last fall the owner kind of cared, but they really don’t give a shit, they just want to make money. And I think as long as there's owners out there who don’t care nothing's going to change. They don’t want it to change, they want you to work for as cheap as possible and do as much work as possible for that amount of money.

Increased Workloads

Phase 1 showed an imbalance between effort and rewards with elevated ERI values (CI95%: 1.07, 1.29) prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. The effort reward imbalance (ERI) results showed that the reported efforts were higher than the reported rewards (paired sample t test; P < 0.05) with all participants reporting ERI values above 1.0, the baseline for acceptable working conditions with low effort relative to rewards. Although ERI scores were not significantly associated with the average stress levels (P > 0.05), they were inversely correlated with job satisfaction (Pearson correlation: r = –0.64, P < 0.01). As the effort and workload increased, workers reported less job satisfaction.

This imbalance was reportedly worsened during the pandemic as added responsibilities were placed on employees due to inadequate staffing. This led to employees having fewer work breaks and having to manage more responsibilities which in turn led to greater health risks. Here is an example of stressors associated with increased workload:

I had fewer hours. Only because we had less need, less capacity, which ended up making the people who were working work way harder, but that's a different story. And yeah then there were people who were kinda totally just cut from the staff for a time, and for so long they were like, I’m not even sure I still have a position at work anymore.

Interpersonal Interactions

The majority of the participants surveyed prior to the COVID-19 pandemic received some tips as part of their wage (78.9%, n = 30) with a median base wage of $6.40. Of these workers, 80% (n = 24) said that having the tipped wage always or usually increased their stress. Ninety-three percent (n = 28) of these workers reported that the variability in tips from day to day and customer to customer always or usually increased their stress. Seventy-seven percent (n = 23) of respondents said tips lead to discrimination or harassment seldomly or about half the time. None of these variables had a significant impact on cortisol levels (P > 0.05).

During the pandemic stressors related to interpersonal relationships were magnified. Respondents lamented about the need to monitor customer behaviors and impose mask and social distancing rules and regulations. As a result, customers were withholding tips because they didn’t like being told what to do.

One interviewee recounted a fairly common sentiment expressed by customers in the beginning of the pandemic when asked if she witnessed customers disregarding safety regulations:

Yeah, definitely. There were people who refused to wear a mask. And when they were told to wear one, they fought it as much as they could. We were taking temperature at the time. I am not sure how much of a precaution that was, but a lot of people refused to take that. A lot of people refused to stay seated and would try to mingle with other groups, which was not allowed. A lot of people had big parties, which we didn’t allow at first. By the end of my time there, we were allowing because a lot of people were threatening to cancel their memberships and other stuff. People definitely didn’t follow the regulations.

Racism played a role in abusive interactions with customers before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. The range of Everyday Discrimination Scale (EDS) scores was 9 to 40 out of a possible 45 with only two participants (5%) reporting no discrimination (Table 3). Seventy-two percent (n = 28) of participants reported occurrences of discrimination a few times a year and 25% (n = 11) reported discrimination ranging from a few times a month to almost every day. The EDS results did not show significant variation of frequency within racial or gender identity presumably due to the uneven distribution of demographics within the sample population. Of the participants that reported discrimination, most reported multiple reasons for experiencing discrimination (69.2%, n = 18) with gender, race and ethnicity, and shade of skin color most commonly reported.

During the interviews, one interviewee expressed the stressful atmosphere at work, especially in the spring of 2020 when there were many unknowns and when Asian Americans, who were targeted for abuse during the pandemic, were overtly harassed. She explained:

The race discrimination came from customers quite a bit. There was one time that didn’t have to do with the employees. There was this one guy making racist comments to an Asian man and they almost got into a fist fight, which is pretty insane. He got thrown out thankfully.

Although our interviewees did report that the majority of customers were respectful in keeping social distance and keeping their masks on and following other safety regulations, the interviewees also reported that many customers had a disrespectful demeanor:

So like there's still the people like ‘I’m not wearing this mask’ and will throw hissy fit and so it's just the risk of being verbally assaulted which I have, over someone putting something on their face, so it's just like the risk of getting sick, the risk of having to confront a b∗∗∗∗ about a mask, and like a risk of just like having to deal with constant confrontation that is unnecessary, so.

One interviewee commented that customers might ‘tip passive-aggressively’ to express how they feel about being reprimanded about not following health safety protocols:

The dynamic has to change. There's already been a power imbalance where the person being served dictates whether the person serving them is making minimum wage or not … the fact that that person who's paying you, you also are policing their behavior…that's too out of balance… and then…the additional element where it's like you don’t know what risks they’re taking, they are kind of disregarding your health by coming in and needing to be served by you, on some level…it kind of feels like the social contract has been broken there.

DISCUSSION

There are several structural elements of the restaurant industry that contributed to occupational stress including financial hardships, elevated health impacts, relatively high workloads, and a pay structure where individual discretion and scheduling dictate wages. These elements were present before the COVID-19 pandemic and have persisted throughout with heightened impacts. Our findings indicate that workers in the restaurant industry experience and continue to experience occupational stress disproportionately due to imbalances inherent to their work which warrants further investigation. These include an effort to reward imbalance with higher workloads and less job security and growth, a power imbalance between workers and the customers they serve with reported discrimination and abuse rooted in the tipped wage, and a financial imbalance between a living wage and an industry that lacks consistent and sufficient pay.

Occupational stress factors were reported to be exasperated since the COVID-19 pandemic. Indeed, the restaurant industry was an already “labor-intensive and stressful work environment” whose workers, when put through the additional stress of the pandemic, experienced higher mental health impacts, and occupational stress.8,28 Participants attributed stress to excessive workloads, staff shortages, and a general lack of control over the work environment which is consistent with the main contributing factors to occupational stress reported in the literature as high job demands and low control work.29–31 Furthermore, our data indicate a link between high workloads and less job satisfaction and more occupational stress. This is also borne out in the literature which shows an inverse correlation between job satisfaction and occupational stress.32 The unequal power structures brought out by differences in race, ethnicity, and citizenship seen in our findings has also been reported in the literature.33,34

Our results showed a range of inequities that mark the lives of restaurant workers. Power inequities which are not only tied to differences in race, ethnicity, or citizenship but rather are an interaction of a number of different social identity markers. Cultural and social capital which describe how non-material resources such as knowledge and access to social networks also correlate to one's earning potential and occupation opportunities.35 Social capital is particularly useful for understanding the differential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on restaurant workers. Namely, those with strong social networks have had a very different experience of being laid off than those without and a person's ability to manage financial crises often depends on the level of their cultural capital.36,37 As we have pointed out, restaurant employees worked in stress-producing environments prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and in 2020, restaurant workers experienced additional stressors in the workplace. The fact that few supports existed for these workers, their occupational health and well-being were further placed in jeopardy.

Limitations and Strengths

There are notable limitations to this study. Phase 1 data collection was halted due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent shutdown of the restaurant industry. This impacted the sample size and make-up which diminished the generalizability and statistical power of the study. Furthermore, these studies were originally designed as two separate studies and combined at analysis. This affected the integrity of the mixed-method design and analysis. Lastly, the time of saliva collection was not recorded which due to the circadian rhythm of stress biomarkers, made it difficult to determine an individual baseline. In follow-up studies of this kind, it is recommended that self-administered sampling is enhanced through mobile app technology with reminders and features to input sampling time.

Despite these limitations, this is one of the first studies that reported on occupational stress in the COVID-19 pandemic. We provided an exploratory comparison of the contributing factors to stress before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, through in-depth interviews, biomarker data, and questionnaire responses. Because these factors were documented throughout our findings and remained largely the same during these unprecedented times, our findings highlight the structural factors of restaurant work that contribute most to ill health. Our findings can inform policy makers and industry stakeholders on ways to reopen restaurants in a more healthful and equitable manner.

Our recommendations include repairing these imbalances that were formed at the inception of the restaurant industry.13 In order to decrease the power struggles that exist in the industry especially those between employees and customers, and to ensure that all employees are able to make a living wage, less reliance on customer goodwill is needed. It is most effective for public health action to address structures that are at the foundation of these inequities through elimination of hazards whenever possible.38,39 This can be done by increasing benefits and wages which are policies that can reduce the documented occupational health disparities particularly within vulnerable worker populations that make up a large segment of the restaurant industry.40 Increasing wages has a marked impact on worker health and in turn the societal health inequities which are dependent on work.41 Dismantling the tipped-wage system is equally important to ensure a fair and equitable work environment free of tip-related harassment and with greater financial benefit to both workers and employers.14 Addressing these and other factors related to the restaurant worker's sense of well-being is even more necessary since the COVID-19 pandemic when measures to protect worker health through personal protective equipment have fallen short and restaurant worker have become frontline essential workers.42

CONCLUSION

Since the contributing factors to stress were found in the pre-pandemic workplace, rather than building the case for the pandemic as the major cause of stress, we argue that the structural components to restaurant work need reform in order for restaurant workers to be protected from occupational stress. Our study is one among many that points to a necessary change in the neoliberal structure of the restaurant industry including strengthening policies which protect the rights of workers and to undo practices such as the tipped-waged which act counter to those that optimize occupational health.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support of the DePaul University Steans Center for Community-based Service Learning for providing renumerations for the study participants and the Executive Director, Howard Rosing, for connecting researchers and the Restaurant Opportunity Center-Chicago. They also acknowledge the support of Jose Oliva at the HEAL Food Alliance and Osvaldo Valenzuela from ROC-Chicago for assistance in study conceptualization, participant recruitment, and data collection. Lastly, they acknowledge our student researcher assistants who collected and analyzed this data.

Footnotes

Funding sources: The results reported herein correspond to specific aims of funding given in support of Julia F. Lippert, PhD and Nila Ginger Hofman, PhD from DePaul University's College of Science and Health and the Steans Center for Community-based Service Learning.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Ethical considerations & disclosures: Study was approved by the DePaul University's Internal Review Board (JL121919CSH). Patient consent was obtained verbally and in written form for the different phases of the research.

Supplemental digital contents are available for this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Desilver D. 10 facts about American workers [Internet]. Pew Research Center; 2016. (Fact Tank: News in the Numbers). Available at: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/09/01/8-facts-about-american-workers/. Accessed April 2, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. May 2019 National Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates [Internet]. Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics; 2019. Available at: https://www.bls.gov/oes/2019/may/oes_nat.htm#35-0000. Accessed June 28, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bureau of Labor Statistics. The employment situation-March 2021. News Release; 2021: 41. [Google Scholar]

- 4. National Restaurant Association. National Statistics: the size, scope, and impact of the U.S. restaurant industry [Internet]; 2021. Available at: https://restaurant.org/research/restaurant-statistics/restaurant-industry-facts-at-a-glance. Accessed August 16, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jeong BY. Cooking processes and occupational accidents in commercial restaurant kitchens. Saf Sci 2015; 80:87–93. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Restaurant Opportunities Center United. State of the Restaurant Workers [Internet]. State of Restaurant Workers; 2021. Available at: https://stateofrestaurantworkers.com/. Accessed April 16, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shigihara AM. Postmodern life, restaurants, and COVID-19. Contexts 2020; 19:26–31. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosemberg MS, Adams M, Polick C, Li WV, Dang J, Tsai JH. COVID-19 and mental health of food retail, food service, and hospitality workers. J Occup Environ Hyg 2021; 18:169–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sim MR. The COVID-19 pandemic: major risks to healthcare and other workers on the front line. Occup Environ Med 2020; 77:281–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational Employment Statistics [Internet]; 2018. Available at: https://www.bls.gov/oes/ Accessed February 20, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harvey D. A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ong A. Neoliberalism as Exception: Mutations in Citizenship and Sovereignty. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lippert JF, Rosing H, Tendick-Mantesanz F. The health of restaurant work: a historical and social context to the occupational health of food service. Am J Ind Med 2020; 63:563–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reyes T. One fair wage: supporting restaurant workers and industry growth. Invest Work 2018; 2:27–41. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allen JR, West DM. Reopening America: How to Save Lives and Livelihoods. 2020; Washington DC: Bookings Institution Press, 106. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sönmez S, Apostolopoulos Y, Lemke MK, Hsieh Y-C (Jerrie). Understanding the effects of COVID-19 on the health and safety of immigrant hospitality workers in the United States. Tour Manag Perspect 2020; 35:100717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Avdiu B, Nayyar G. When face-to-face interactions become an occupational hazard: jobs in the time of COVID-19 [Internet]. Brookings; 2020. Available at: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/future-development/2020/03/30/when-face-to-face-interactions-become-an-occupational-hazard-jobs-in-the-time-of-covid-19/. Accessed May 11, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tuzovic S, Kabadayi S, Paluch S. To dine or not to dine? Collective wellbeing in hospitality in the COVID-19 era. Int J Hosp Manag 2021; 95:102892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cubrich M. On the frontlines: protecting low-wage workers during COVID-19. Psychol Trauma 2020; 12:S186–S187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McAfee M, Park C, Rios K, Kapetaneas J, Rivas A. “Underlying crisis”: Foodservice workers protest lack of COVID-19 safety measures, hazard pay. ABC News [Internet]; 2020. Available at: https://abcnews.go.com/Business/underlying-crisis-foodservice-workers-protest-lack-covid-19/story?id=70195869. Accessed October 6, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tashakkori A, Teddue C. Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social and Behavioral Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dhama K, Latheef SK, Dadar M, Samad HA, Munjal A, Khandia R, et al. Biomarkers in Stress Related Diseases/Disorders: Diagnostic, Prognostic, and Therapeutic Values. Front Mol Biosci; 2019: 6. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6843074/. Accessed June 1, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holstein JA, Gubrium JF. Grounded theory methodology. Strategies for Qualitative Inquiry. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aardal E, Holm AC. Cortisol in saliva--reference ranges and relation to cortisol in serum. Eur J Clin Chem Clin Biochem 1995; 33:927–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brodke MR, Sliter MT, Balzer WK, et al. The Job Descriptive Index and Job in General (2009 Revision): Quick Reference Guide. Bowling Green, OH: Bowling Green State University; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 26. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. FY 2021 Income Limits Documentation System [Internet]. Income Limits; 2021. Available at: https://www.huduser.gov/portal/datasets/il.html. Accessed April 21, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 27. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Drinking Levels Defined [Internet]. Alcohol's Effects on Health: Overview of Alcohol Consumption; 2021. Available at: https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/overview-alcohol-consumption/moderate-binge-drinking. Accessed April 24, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bufquin D, Park J-Y, Back RM, de Souza Meira JV, Hight SK. Employee work status, mental health, substance use, and career turnover intentions: an examination of restaurant employees during COVID-19. Int J Hosp Manag 2021; 93:102764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chiang FFT, Birtch TA, Kwan HK. The moderating roles of job control and work-life balance practices on employee stress in the hotel and catering industry. Int J Hosp Manag 2010; 29:25–32. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murray-Gibbons R, Gibbons C. Occupational stress in the chef profession. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag 2007; 19:32–42. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Papadopoulou-Bayliss A, Ineson EM, Wilkie D. Control and role conflict in food service providers. Int J Hosp Manag 2001; 20:187–199. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boles JS, Babin BJ. On the front lines: stress, conflict, and the customer service provider. J Bus Res 1996; 37:41–50. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Crewshaw K. Crewshaw K. Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics and Violence Against Women of Color. Critical Race Theory: The Key Writings that Formed the Movement.. New York: New Press; 1995; 357-383. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith B. Combahee River Collective. The Combahee River Collective Statement. Home Girls: A Black Feminist Anthology.. New York: Kitchen Table Women of Color Press; 1983; 264-274. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bourdieu P. Distinction: a Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Boston, US: Harvard University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Villa L. Undocumented Immigrants Are Essential But Exposed In the Coronavirus Pandemic. Time [Internet]; 2020. Available at: https://time.com/5823491/undocumented-immigrants-essential-coronavirus/. Accessed June 1, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu C. Social capital and COVID-19: a multidimensional and multilevel approach. Chin Sociol Rev 2021; 53:27–54. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Frieden TR. A framework for public health action: the health impact pyramid. Am J Public Health 2010; 100:590–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Hierarchy of Controls [Internet]; 2020. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/hierarchy/default.html. Accessed May 13, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Siqueira CE, Gaydos M, Monforton C, et al. Effects of social, economic, and labor policies on occupational health disparities: effects of policies on occupational health disparities. Am J Ind Med 2014; 57:557–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ahonen EQ, Fujishiro K, Cunningham T, Flynn M. Work as an inclusive part of population health inequities research and prevention. Am J Public Health 2018; 108:306–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hecker S. Hazard pay for COVID-19? Yes, but it's not a substitute for a living wage and enforceable worker protections. NEW Solut 2020; 30:95–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.