Abstract

Background

Older women’s mental health may be disproportionally affected by the COVID-19 pandemic due to differences in gender roles and living circumstances associating with aging.

Methods

We administered an online cross-sectional nationwide survey between May 1st and June 30th, 2020 to a convenience sample of older adults aged ≥55 years. Our outcomes were symptoms of depression, anxiety, and loneliness measured by three standardized scales: the eight-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale, the five-item Beck Anxiety Inventory, and the Three-Item Loneliness Scale. Multivariable logistic regression was used to compare the odds of depression, anxiety and loneliness between men and women, adjusting for relevant confounders.

Results

There were 1,541 respondents (67.8% women, mean age 69.3 ± 7.8). 23.3% reported symptoms of depression (29.4% women, 17.0% men), 23.2% reported symptoms of anxiety (26.0% women, 19.0% men), and 28.0% were lonely (31.5% women, 20.9% men). After adjustment for confounders, the odds of reporting depressive symptoms were 2.07 times higher in women compared to men (OR 2.07 [95%CI 1.50–2.87] p < .0001). The odds of reporting anxiety and loneliness were also higher.

Conclusions

Older women had twice the odds of reporting depressive symptoms compared to men, an important mental health need that should be considered as the COVID-19 pandemic unfolds.

Keywords: mental health, older adults, COVID-19, gender roles, women’s health, cross-sectional survey

INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 (coronavirus) pandemic is an unprecedented crisis with the potential for dire immediate and long-term consequences to older adults’ health and well-being. Older adults are not only at higher risk for severe morbidity and mortality from COVID-19,(1–3) but may also suffer greater emotional harms associated with the pandemic.(4) During the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak in 2003, there were increases in loneliness, anxiety, and depression resulting from social isolation under quarantine measures,(5) and rates of suicide among older adults increased in high-outbreak jurisdictions such as Taipei and Hong Kong.(6,7) In Canada, the current physical distancing measures have limited social interactions and curtailed many activities for older adults. The World Health Organization (WHO) has emphasized specific concerns for older adults who, because of isolation, could become more anxious during the COVID-19 pandemic.(8) Social isolation may disproportionally affect older women, who are more likely to live alone and more likely to rely on a caregiver for support.(9) These findings highlight the urgency to study the mental health impact of COVID-19 among older women in particular, so that any adverse impacts can be anticipated and minimized.

Several observational studies related to mental health experiences among older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic have been reported. Longitudinal studies from the UK and The Netherlands demonstrated increased mental distress and/or loneliness compared to pre-pandemic estimates.(10,11) When compared to younger age groups, older adults have been less likely to report anxiety, depression, and stress-related mental health disorders during the initial phase of the pandemic, possibly suggesting higher resilience among this age group.(12,13) Although useful to our understanding, the existing studies have not directly examined differences between older women and men, and the unique experiences and needs of older women during the COVID-19 pandemic are largely unknown.(14)

The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of Canadian older adults, particularly women, are not well characterized, limiting the development of targeted strategies to support their needs in the wake of this crisis. Our objective was to describe the mental health symptoms and concerns of Canadian older adults during the outset of the pandemic, and to examine whether older women experienced greater mental distress compared to older men.

METHODS

Study Design and Population

This was a cross-sectional study based on the analysis of national survey data collected under the “Canadian COVID-19 Coping Study: A longitudinal online survey of older adults’ health and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic”. The survey was designed by researchers at the University of Michigan Institute for Social Research(15) and adapted with permission for the Canadian context. The survey comprised of 53 questions and collected information regarding socio-demographic data (e.g., age, gender, education), COVID-19–related experiences, perspectives and impacts on daily life, and self-reported mental health symptoms. We followed the guidelines described in the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES).(16)

Data Collection

The survey was administered between May 1st, 2020 and June 30th, 2020. At this time, physical distancing measures in most of Canada had been in place since March and most provinces started lifting restrictions as cases started to decline after a peak in late April. We administered the survey online using Qualtrics software (QualticsXM, Provo, UT; www.qualtrics.com). We provided the survey and recruitment materials in both English and French. The questionnaire was pretested in both languages for usability, technical functionality, clarity and timing. Written consent was collected from all participants through the online platform prior to administering the survey. No monetary incentives were provided, but respondents could email the investigator if they wanted to know about the survey results. The results of the pretesting were not included in the final analysis.

Survey Dissemination

We recruited eligible participants aged 55 and older using convenience and snowball sampling through social media internet platforms such as Facebook and Twitter, and through targeted email recruitment to societies with older adult membership. Various organizations with older adult membership (see Acknowledgments) circulated the survey link online. Although age 65 is typically used to define older persons in western countries, we chose an age cutoff of 55, recognizing that ageing is both a biological and social construct and some individuals, such as those enduring poverty, may experience aging earlier than others.(17)

Survey Completion

We excluded surveys if fewer than five questions were answered, if age was missing, if gender was missing, if respondents were younger than 55, or if respondents did not go beyond providing demographic information. The survey completion rate was calculated as the number of respondents who answered the last question, divided by the number of respondents who consented to participate. We used adaptive questioning for certain items (i.e., some questions conditionally displayed based on earlier responses) to reduce the number and complexity of the questions. Qualtrics software did not allow for completeness checks prior survey submission, and there were no mandatory items due to REB specifications. Respondents were able to review and change their answers through a back button function before submitting the survey.

Study Variables

Gender was measured by asking participants “what is your gender” with the option to choose male, female, other, or prefer not to answer. We collected information regarding COVID-19 symptoms and testing, extent of practicing physical distancing, and communication with others in the previous seven days. We used Likert scale questions to collect measures of concern and attitudes towards COVID-19–related experiences hypothesized to contribute to mental distress. Our outcomes were symptoms of depression, anxiety, and loneliness as measured by three standardized scales: the eight-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), the five-item Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), and the Three-Item Loneliness Scale. Symptoms were based on self-reported feelings and experiences within the previous week. The eight-item CES-D has been used in the US Health and Retirement Study and has high internal consistency and reliability.(18,19) We used a score ≥ 3 to define meaningful depressive symptoms, which was determined to be similar to the cut point of ≥ 16 on the full CES-D(19) and has been used in prior research with older adults.(20) The five-item BAI has been used in other studies of older adults with good internal consistency.(21) We defined meaningful anxiety symptoms as scores ≥ 10 on the five-item BAI, as that corresponded the highest quartile of the distribution in our sample, which is a similar justification of cut-off scores used by Gould et al.(22) Loneliness was measured using the Three-Item Loneliness Scale, a validated, self-rated tool with illustrated reliability and correlation to the full 20-item revised UCLA loneliness scale.(23) A total score of ≥ 6 was considered lonely, similar to other epidemiologic survey-based studies of older adults.(24,25)

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were presented and stratified by gender. Categorical variables were compared using chi-square tests for independence, and continuous data were compared using t-tests. Psychometric properties of each mental health scale were assessed using the Chronbach coefficient alpha. Multivariable logistic regression was used to compare the odds of reporting symptoms of depression, anxiety, and loneliness between men and women. Two models were created to test this association, adjusting for 1) age (continuous), race, education, employment status, relationship status, living alone, self-reported health, number of self-reported comorbidities (continuous); and 2) all the variables in model 1 plus self-reported history of anxiety and self-reported history of depression. Confounders were selected based on the literature and known predictors of mental health symptoms that did not fall along the causal pathway.(26,27) Model fit for each was evaluated using the Hosmer-Lemeshow test and p value.

This study received health ethics research board approval through the Women’s College Hospital Research Ethics Board (REB # 2020-0045-E).

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

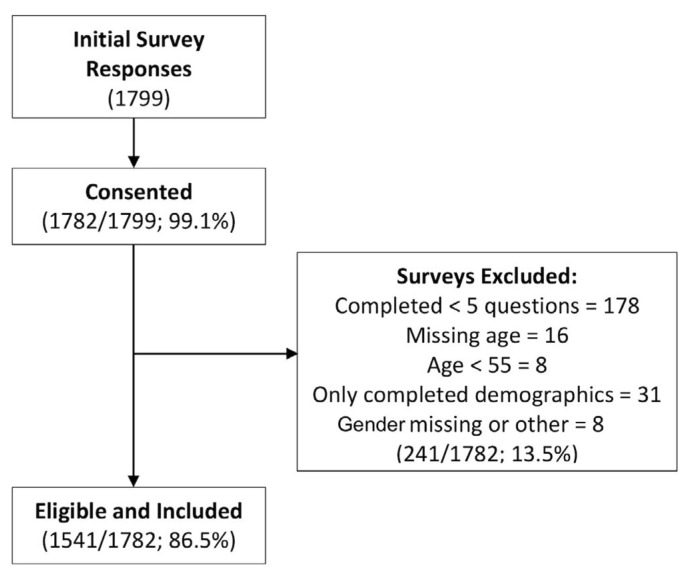

There were 1,799 survey respondents, of which 1,782 provided consent and 1,541 submitted a response to the final question for a completion rate of 86.5%. After exclusions, the final sample of respondents included in the analysis was 1,541 (Figure 1). Most respondents resided in Ontario (52.3%), followed by British Columbia (17.5%) and Quebec (10.8%), with 10.3% in the western provinces (AB, SK, MB) and 9.0% in the Atlantic Provinces. For complete socio-demographic characteristics of respondents, see Table 1. Overall, most respondents were women (67.8%), between the ages of 65–74 years (46.9%), were retired (78.0%), were white (95.8%), had attained some post-secondary education (84.1%), and completed the survey in English (91.8%). The majority of respondents were in good self-reported health (88.5% men, 87.9% women), and less than half reported more than one chronic condition (41.9% men, 37.5% women). Women were more likely to be single (38.0% vs. 16.5%, p < .0001) and more likely to live alone (33.2% vs. 14.1%, p < .0001) compared to men. Women were more likely than men to report pre-existing anxiety (18.3% vs. 12.5%, p < .004) and depression (20.3% vs. 13.3%, p < .0009).

FIGURE 1.

Study recruitment flow chart

TABLE 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of survey respondents

| Characteristics | Men (n=496) | Women (n=1,045) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average age years (SD) | 71.2 (8.2) | 68.4 (7.4) | <.0001 |

|

| |||

| Age categories in years (n, %) | <.0001 | ||

| 55–64 | 117 (23.6) | 339 (32.4) | |

| 65–74 | 215 (43.4) | 507 (48.5) | |

| 75–84 | 134 (27.0) | 170 (16.3) | |

| 85+ | 30 (6.1) | 29 (2.8) | |

|

| |||

| Language | .36 | ||

| English | 460 (92.7) | 955 (91.4) | |

| French | 36 (7.3) | 90 (8.6) | |

|

| |||

| Race/ethnicity (%)a | |||

| White | 1005 (96.2) | 472 (95.2) | .35 |

|

| |||

| Current relationship status (n, %)b | |||

| Single/Divorced/Widowed | 81 (16.5) | 394 (38.0) | <.0001 |

| Married or in a relationship | 410 (83.5) | 644 (62.0) | |

|

| |||

| Education (n, %)c | .38 | ||

| High school/less than high school | 81 (16.3) | 163 (15.6) | |

| Some university | 110 (22.2) | 229 (21.9) | |

| Trade or college diploma/certificate | 119 (24.0) | 275 (26.3) | |

| Bachelor degree | 165 (33.3) | 313 (30.0) | |

| Graduate degree | 21 (4.2) | 64 (6.1) | |

|

| |||

| Pre-COVID Employment Status (n, %)d | .16 | ||

| Employed | 95 (19.2) | 220 (21.1) | |

| Retired | 397 (80.2) | 805 (77.3) | |

| Unemployed | 3 (0.61) | 17 (1.6) | |

|

| |||

| Living Alone (n, %)e | 69 (14.1) | 344 (33.2) | <.0001 |

|

| |||

| Self-reported health (n, %)f | .94 | ||

| Excellent | 88 (17.9) | 202 (19.5) | |

| Very Good | 207 (42.2) | 422 (40.8) | |

| Good | 144 (29.3) | 295 (28.5) | |

| Fair | 46 (9.4) | 103 (10.0) | |

| Poor | 6 (1.2) | 13 (1.3) | |

|

| |||

| Mobility Aid Use (n, %) | 54 (10.9) | 102 (9.8) | .49 |

|

| |||

| Caregiving Responsibilities (n, %)g | 102 (20.6) | 252 (24.2) | .12 |

|

| |||

| Chronic Conditions | |||

| Anxiety | 62 (12.5) | 191 (18.3) | .004 |

| Asthma | 31 (6.3) | 123 (11.8) | .0007 |

| Cancer | 73 (14.7) | 120 (11.5) | .07 |

| COPD | 24 (4.8) | 40 (3.8) | .35 |

| Depression | 66 (13.3) | 212 (20.3) | .0009 |

| Diabetes | 83 (16.7) | 90 (8.6) | <.0001 |

| Heart disease | 86 (17.3) | 69 (6.6) | <.0001 |

| High blood pressure | 237 (47.8) | 360 (34.5) | <.0001 |

| Other long-standing condition | 76 (15.3) | 194 (18.6) | .12 |

|

| |||

| Multi-morbidity (>1 reported condition) | 208 (41.9) | 392 (37.5) | .09 |

Missing = 2;

Missing = 12;

Missing = 1;

Missing = 5;

Missing = 14;

Missing = 15;

Missing = 2.

Concerns/Experiences Related to COVID-19

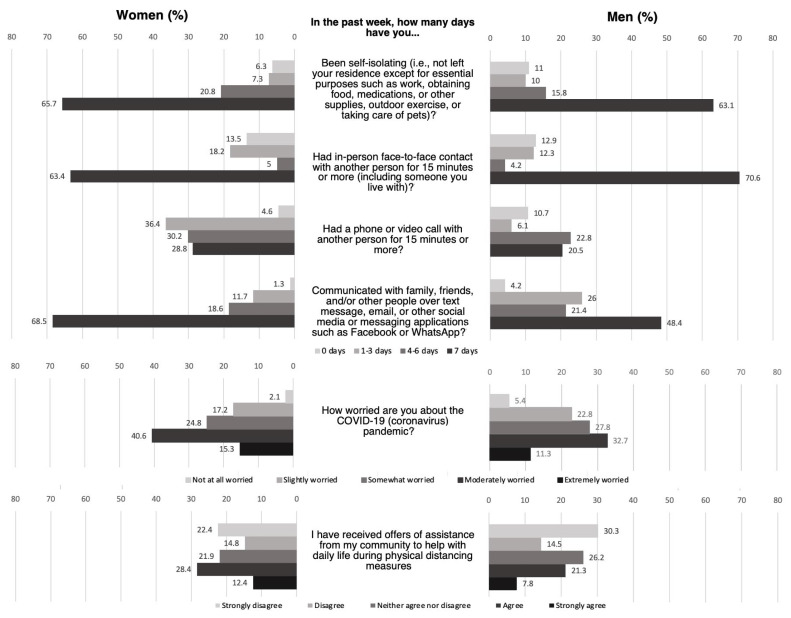

Just five of 1,541 respondents (0.3%) had tested positive for COVID-19, but 9.5% reported a flu-like illness since the start of the pandemic, 5.0% reported a family member of friend hospitalized due to COVID-19, and 4.1% had a family member or friend die as a result of COVID-19. Compared to men, women were more likely to report that they had been self-isolating at home over the previous seven days (65.7 vs. 63.1, p < .0001) (Figure 2). Women were more likely than men to report daily communication with others through phone/video (28.8% vs. 20.5%, p < .0001), or through texting or social media (68.5% vs. 48.4%, p < .0001). Women were also more likely to be extremely or moderately worried about the pandemic (55.9% vs. 44.0%, p < .0001), and more likely to report receiving offers of assistance from their community (40.8% vs. 29.1%, p < .0001), compared to men.

FIGURE 2.

COVID-related concerns and experiences

Reported Mental Health Symptoms

All three mental health scales had good internal consistency, with Chronbach’s alpha of 0.82 for the 8-item CES-D, 0.76 for the 5-item BAI, and 0.78 for the Three-Item Loneliness Scale. As outlined in Table 2, 23.3% of respondents reported depressive symptoms (29.4% women, 17.0% men), 23.2% reported symptoms of anxiety (26.0% women, 19.0% men), and 28.0% identified as lonely (31.5% women, 20.9% men). Almost half (45.3%) of all surveyed participants (34.7% men, 50.3% women) reported symptoms consistent with any one of the three mental health conditions, and 7.7% (5.2% men, 8.8% women) met symptom thresholds for all three. After adjustment for known confounders, the odds of reporting depressive symptoms were 2.07 times higher in women compared to men (OR 2.07 [95%CI 1.50–2.87] p < .0001). Women also had higher odds of reporting symptoms of anxiety (OR 1.63 [95% CI 1.21–2.21] p = .001) and loneliness (1.33 [95% CI 1.01–1.76] p = .001). When adjusted for previous diagnosis of anxiety and depression, these associations persisted for elevated anxiety and depressive symptoms, but not for loneliness.

TABLE 2.

Differences in the odds of depressive, anxiety, or loneliness symptoms by gender

| Mental Health Symptoms | N (%) | OR (95% CI) | p value | AOR 1a (95% CI) | p-value | AOR 2b (95% CI) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | Men | 75 (17.0) | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Women | 281 (29.4) | 2.03 (1.53–2.70) | <0.0001 | 2.07 (1.50–2.87) | <0.0001 | 1.90 (1.37–2.66) | 0.0001 | |

|

| ||||||||

| Anxiety | Men | 92 (19.0) | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Women | 266 (26.0) | 1.50 (1.15–1.96) | 0.003 | 1.63 (1.21–2.21) | 0.001 | 1.51 (1.11–2.04) | 0.009 | |

|

| ||||||||

| Loneliness | Men | 103 (20.9) | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Women | 329 (31.5) | 1.77 (1.37–2.28) | <0.0001 | 1.33 (1.01–1.76) | 0.001 | 1.28 (0.97–1.70) | 0.09 | |

Ref = reference.

Adjusted for age, race, education, employment status, relationship status, living alone, self-reported health, number of comorbidities.

All variables in model 1 + pre-existing self-reported anxiety and depression. Model fit: checked on AOR1 → Depression: good fit (HL test p-value 0.62); Anxiety: good fit (HL test p value 0.91); Loneliness: good fit (HL test p value 0.32).

DISCUSSION

In a survey of older Canadian adults, elevated mental health symptoms were commonly reported during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Older women had twice the odds of reporting depressive symptoms and higher odds of reporting anxiety and loneliness, even after controlling for pre-existing depression and anxiety, as well as factors hypothesized to contribute to gender differences including level of education, relationship status, living alone, and health status. The majority of respondents had been self-isolating at home and maintaining physical distance from others during the prior seven days. Women were more likely than men to report daily communication with others and were more likely to report concern about the pandemic.

Older women in Canada may need additional mental health support throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly those who live alone or who have multiple health conditions.(28) This result is consistent with studies out of the United Kingdom, China, and Spain showing that women were more likely to experience mental distress including loneliness, anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder during the pandemic.(29–31) The differences in mental health impact from pandemic restrictions among older women are possibly due to greater likelihood of widowhood, lower income,(32) and increased likelihood of taking on caregiving roles.(33,12) Given the extended duration of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated restrictions, it’s possible that the mental health consequences for women will persist well beyond the end of the pandemic. Early interventions, such as social prescribing or connection to mental health services, should be employed to mitigate the long-term consequences of untreated mental distress. Clinicians should consider targeted screening for older women, with particular attention paid to caregivers who may benefit from virtual support groups and safe options for respite to replace the community programs that may have closed.

We observed higher prevalence rates of mental symptoms among older adults compared to what has been reported in Canada before the pandemic using similar survey measures.(34–36) Comparisons should be made cautiously as these differences could be due to factors unrelated to the COVID-19 pandemic, such as study populations, screening tools, and methodologies. Nevertheless, in our survey, 23.3% of respondents reported symptoms of depression compared to 15.3% of older Canadians in 2019.(36) In surveys conducted before the pandemic, 7.7% of Canadian older adults had self-reported anxiety symptoms(34) and 12.0% reported loneliness,(35) less than the 23.3% who reported symptoms of anxiety and 28.0% who identified as lonely in our survey. Almost half of all surveyed participants reported symptoms consistent with any one of the three mental health conditions and 7.7% reported symptoms of all three, suggesting a high burden of mental distress in this population during the early months of the pandemic. It’s possible that current levels of mental distress could be even higher after several waves of infection, ongoing restrictions and closures, and concern about emerging variants. As health authorities across Canada implement future public health measures to limit the spread of COVID-19 and other infectious diseases, the mental health needs of older adults should be considered. Improving access to digital technology for mental health support is an important step as many older adults currently lack access to internet-enabled devices.(37) While the use of technology may be helpful for older adults who are willing and able,(38) others may not feel ready or comfortable and it is imperative that other models of care, such as in-person visits with safety precautions, are still offered.(39)

An important study limitation is that our data is based on a convenience sample of mostly white, retired, well-educated, healthy older adults living in urban Canadian centres with internet access, which limits the generalizability of our findings. Marginalized populations who are at greater risk of mental health distress (e.g., older adults with low income, those living in residential care settings) are under-represented. As such, our findings may be a conservative estimate of mental distress during the COVID-19 pandemic. Self-reported mental health symptoms should not be interpreted as prevalence rates for psychiatric disorders(40) as data may be subject to response bias, and the mental health screening tools used do not reflect a validated diagnostic interview. Finally, differences between women and men may be explained by unmeasured diagnoses, such as alcohol misuse, or the fact that men may be less likely to report mental health symptoms.(41)

CONCLUSION

Our findings underscore the importance of interventions to support mental well-being for older women throughout the course of the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. There should be adequately resourced services to screen for, and meet, the additional mental health needs of older women. Improving access to digital technologies for social connectivity and home delivery of essential items may be particularly good options, as our study suggests that older women are likely to use virtual communication and accept offers of assistance from their community. Given that the full duration of this pandemic remains unknown, it is imperative that older women are supported to mitigate long-term adverse mental health outcomes. It will be important to consistently measure how mental distress changes over time, especially for older women with pre-existing mental health diagnoses who may face additional challenges heightened by pandemic emergency responses.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the National Association of Federal Retirees, The Canadian Geriatrics Society, The Canadian Academy of Geriatric Psychiatry, The Canadian Coalition for Seniors Mental Health, and The Canadian Institute for Military and Veteran Health Research for their assistance with dissemination of the survey.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

We have read and understood the Canadian Geriatrics Journal’s policy on conflicts of interest disclosure and declare the following interests: Dr Paula Rochon holds the RTOERO Chair in Geriatric Medicine at the University of Toronto.

FUNDING

This research did not receive external funding.

REFERENCES

- 1.Onder G, Rezza G, Brusaferro S. Case-fatality rate and characteristics of patients dying in relation to COVID-19 in Italy. JAMA. 2020;323(18):1725–76. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054–62. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yanez ND, Weiss NS, Romand JA, Treggiari MM. COVID-19 mortality risk for older men and women. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1742. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09826-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Armitage R, Nellums LB. COVID-19 and the consequences of isolating the elderly. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(5):e256. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30061-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hawryluck L, Gold WL, Robinson S, Pogorski S, Galea S, Styra R. SARS control and psychological effects of quarantine, Toronto, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10(7):1206–12. doi: 10.3201/eid1007.030703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yip PS, Cheung YT, Chau PH, Law YW. The impact of epidemic outbreak: the case of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and suicide among older adults in Hong Kong. Crisis. 2010;31(2):86–92. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barbisch D, Koenig KL, Shih FY. Is there a case for quarantine? Perspectives from SARS to Ebola. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2015;9(5):547–53. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2015.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.WHO. Mental health and psychosocial considerations during the COVID-19 outbreak. Geneva: WHO; 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/mental-health-considerations.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gruneir A, Forrester J, Camacho X, Gill SS, Bronskill SE. Gender differences in home care clients and admission to long-term care in Ontario, Canada: a population-based retrospective cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 2013;13(1):48. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-13-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Tilburg TG, Steinmetz S, Stolte E, van der Roest H, de Vries DH. Loneliness and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: a study among Dutch older adults. J Gerontol B Phsychol Sci Soc Sci. 2021;76(7):e249–e255. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbaa111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pierce M, Hope H, Ford T, et al. Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(10):883–92. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30308-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Czeisler M, Lane RI, Petrosky E, et al. Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, June 24–30, 2020. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(32):1049–57. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6932a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vahia IV, Jeste DV, Reynolds CF. Older adults and the mental health effects of COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;324(22):2253–54. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.21753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rochon PA, Stall NM, Gurwitz JH. Making older women visible. The Lancet. 2021;397(10268):21. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32548-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kobayashi LC, O’Shea BQ, Kler JS, et al. The COVID-19 Coping Study: A longitudinal mixed-methods study of mental health and well-being among older US adults during the COVID-19 pandemic (social sciences open source website) 2020 doi: 10.31235/osf.io/f4p2a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eysenbach G. Improving the quality of Web surveys: the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES) J Med Internet Res. 2004;6(3):e132. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6.3.e34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organisation. Women, ageing and health: a framework for action. A focus on gender (report) 2007. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241563529.

- 18.Hann D, Winter K, Jacobsen P. Measurement of depressive symptoms in cancer patients: evaluation of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) J Psychosom Res. 1999;46(5):437–43. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(99)00004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steffick D. Documentation of affective functioning measures in the Health and Retirement Study (HRS/AHEAD Documentation Report No. DR-005) Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Survey Research Center; 2000. Available at https://hrs.isr.umich.edu/publications/biblio/5411. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kobayashi LC, Steptoe A. Social isolation, loneliness, and health behaviors at older ages: longitudinal cohort study. Ann Behav Med. 2018;52(7):582–93. doi: 10.1093/abm/kax033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gould CE, O’Hara R, Goldstein MK, Beaudreau SA. Multimorbidity is associated with anxiety in older adults in the Health and Retirement Study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;31(10):1105–15. doi: 10.1002/gps.4532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gould CE, Rideaux T, Spira AP, Beaudreau SA. Depression and anxiety symptoms in male veterans and non-veterans: the Health and Retirement Study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;30(6):623–30. doi: 10.1002/gps.4193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hughes ME, Waite LJ, Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys: results from two population-based studies. Res Aging. 2004;26(6):655–72. doi: 10.1177/0164027504268574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steptoe A, Shankar A, Demakakos P, Wardle J. Social isolation, loneliness, and all-cause mortality in older men and women. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2013;110(15):5797–801. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219686110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perissinotto CM, Cenzer IS, Covinsky KE. Loneliness in older persons: a predictor of functional decline and death. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(14):1078–83. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen-Mansfield J, Hazan H, Lerman Y, Shalom V. Correlates and predictors of loneliness in older-adults: a review of quantitative results informed by qualitative insights. Int Psychogeriatr. 2016;28(4):557–76. doi: 10.1017/S1041610215001532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boehlen FH, Herzog W, Schellberg D, et al. Gender-specific predictors of generalized anxiety disorder symptoms in older adults: Results of a large population-based study. J Affect Disord. 2020;262:174–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Razai MS, Oakeshott P, Kankam H, Galea S, Stokes-Lampard H. Mitigating the psychological effects of social isolation during the covid-19 pandemic. BMJ. 2020:369. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li LZ, Wang S. Prevalence and predictors of general psychiatric disorders and loneliness during COVID-19 in the United Kingdom. Psychiatry Res. 2020;291:113267. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu N, Zhang F, Wei C, et al. Prevalence and predictors of PTSS during COVID-19 outbreak in China hardest-hit areas: gender differences matter. Psychiatry Res. 2020;287:112921. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.González-Sanguino C, Ausín B, Castellanos M, et al. Mental health consequences during the initial stage of the 2020 Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) in Spain. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:172–76. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O’Rand AM, Shuey KM. Gender and the devolution of pension risks in the US. Curr Sociol. 2007;55(2):287–304. doi: 10.1177/0011392107073315. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bott NT, Sheckter CC, Milstein AS. Dementia care, women’s health, and gender equity: the value of well-timed caregiver support. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74(7):757–58. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.0403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scott T, Mackenzie CS, Chipperfield JG, Sareen J. Mental health service use among Canadian older adults with anxiety disorders and clinically significant anxiety symptoms. Aging Mental Health. 2010;14(7):790–800. doi: 10.1080/13607861003713273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Statistics Canada. Social isolation and mortality among Canadian seniors. Report No. 82-003-X. Health Reports. 2020;31(3):27–38. doi: 10.25318/82-003-x202000300003-eng. Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu J, Son S, McIntyre J, Narushima M. Depression and cardiovascular diseases among Canadian older adults: a cross-sectional analysis of baseline data from the CLSA Comprehensive Cohort. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2019;16(12):847–54. doi: 10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2019.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roberts ET, Mehrotra A. Assessment of disparities in digital access among Medicare beneficiaries and implications for telemedicine. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(10):1386–89. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.2666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Malla A, Joober R. COVID-19 and the future with digital mental health: need for attention to complexities. Can J Psychiatry. 2021;66(1):14–16. doi: 10.1177/0706743720957824. Epub 2020 Sept 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lam K, Lu AD, Shi Y, Covinsky KE. Assessing telemedicine unreadiness among older adults in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(10):1389–91. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.2671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thombs BD, Kwakkenbos L, Levis AW, Benedetti A. Addressing overestimation of the prevalence of depression based on self-report screening questionnaires. Can Med Assoc J. 2018;190(2):E44–E49. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.170691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Choi NG, DiNitto DM. Heavy/binge drinking and depressive symptoms in older adults: gender differences. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;26(8):860–68. doi: 10.1002/gps.2616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]