Abstract

BACKGROUND:

A sense of purpose in life has been associated with healthier cognitive outcomes across adulthood, including risk of dementia. The robustness and replicability of this association, however, has yet to be evaluated systematically.

OBJECTIVE:

To test whether a greater sense of purpose in life is associated with lower risk of dementia in four population-based cohorts and combined with the published literature.

METHODS:

Random-effect meta-analysis of prospective studies (individual participant data and from the published literature identified through a systematic review) that examined sense of purpose and risk of incident dementia.

RESULTS:

In six samples followed up to 17 years (four primary data and two published; total N=53,499; n=5,862 incident dementia), greater sense of purpose in life was associated with lower dementia risk (HR=.77, 95% CI=.73–.81, p<.001). The association was generally consistent across cohorts (I2=47%), remained significant controlling for clinical (e.g., depression) and behavioral (e.g., physical inactivity) risk factors, and was not moderated by age, gender, or education.

DISCUSSION:

Sense of purpose is a replicable and robust predictor of lower risk of incident dementia and is a promising target of intervention for cognitive health outcomes.

Keywords: Sense of purpose, dementia risk, meta-analysis, cognitive health, well-being

Effective prevention of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD) starts with a better understanding of risk and protective factors for cognitive impairment. There are established, modifiable risk factors for ADRD, including hypertension, diabetes, obesity, depression, smoking, and physical inactivity [1]. One psychological characteristic of individuals who avoid these risk factors—and thus have a low-risk profile—is that they live their life with purpose. A sense of purpose in life is the feeling that one’s life is goal-oriented and driven [2] and is one component of a meaningful life [3]. Initial work on purpose and Alzheimer’s disease indicated it is protective against poor cognitive outcomes [4]. Subsequent work has found that a sense of purpose is associated with a range of healthier cognitive outcomes across adulthood: Individuals who report more purpose perform better on cognitive tasks [5], show less age-related cognitive decline over time [6], are at lower risk of developing motoric cognitive risk syndrome [7], and, ultimately, have lower risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease [4] or dementia [8]. Sense of purpose is thus emerging as a robust modifiable factor that promotes healthier cognition. There has not, however, yet been a systematic attempt to quantify this implied robustness. The present research addressed this gap.

With four samples that use participant-level data from the United States, the United Kingdom, and Ireland, the present research tests the association between sense of purpose in life and risk of incident cognitive impairment, whether the association varies by sociodemographic characteristics (age, gender, education), and evaluates whether it is robust to clinical (e.g., diabetes) and behavioral (e.g., physical inactivity) risk factors associated with both purpose and dementia risk. We combine these results with the published literature identified through a systematic search to provide a comprehensive assessment of the replicability and generalizability of sense of purpose in life as a protective factor against ADRD.

Method

Participants and procedure

Data for the present research came from four cohorts: the Health and Retirement Study (HRS)[9], the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA)[10], The Irish LongituDinal study on Ageing (TILDA)[11], and the National Health Trends and Aging Study (NHATS)[12]. The HRS (https://hrs.isr.umich.edu/) is a longitudinal study of aging of Americans aged 50 years and older and their spouses (regardless of age). Purpose in life was first assessed on a random half of the sample in 2006; the other half completed the measure in 2008. These two assessments were combined as baseline. Cognitive status was assessed at every two-year wave from baseline through 2018 (the most recent wave with data available). We previously published the association between purpose and dementia risk in the HRS through 2014 [8]. Since the preparation of that publication, two additional waves of cognitive data in HRS have been released. We thus included the HRS to update the analysis with an additional four years of follow-up. The ELSA (https://www.elsa-project.ac.uk/) is a study of aging of individuals over the age of 50 in England and their spouses (regardless of age). Purpose was first assessed at the baseline wave in 2002. Participants were free of cognitive impairment when recruited into the initial ELSA sample in 2002. Cognitive status was assessed at every two-year wave through 2018 (the most recent wave with data available). The TILDA (https://tilda.tcd.ie/) is a longitudinal study of aging of individuals over the age of 50 and their spouses (regardless of age) in Ireland. Purpose was first assessed at the baseline wave in 2009–2010. Cognitive status was measured at baseline and at every two-year wave through 2016 (the most recent wave with data available). The NHATS (https://www.nhatsdata.org/) is a longitudinal study of Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 years and older [12]. Purpose was first assessed at the baseline wave in 2011. Cognitive status was measured at baseline and at every annual wave through 2019 (the most recent wave with data available). Across studies, participants had to be at least 50 years old, have complete data on purpose and the sociodemographic covariates at baseline and have at least one follow-up assessment of cognitive status to be included in the analytic sample. Participants with missing data were not included in the analysis. Preregistration of this study can be found at https://osf.io/6hsnf.

Measures

Purpose in life.

A 7-item version of the Purpose in Life scale from the Ryff Measures of Psychological Well-being [13] was administered in the HRS. Items (e.g., “I have a sense of direction and purpose in my life.”) were rated on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree), reverse scored when necessary, and the mean taken across items in the direction of greater purpose. A single-item (“How often do you feel that your life has meaning?”) taken from the Pleasure scale of the control-autonomy-pleasure-self-realization scale (CASP-19) of quality of life in older adulthood [14] was used to measure purpose in ELSA and TILDA. This item was measured on a 4-point scale in both studies and reverse scored when necessary to be on a scale from 1 (never) to 4 (often). In the NHATS, purpose in life was measured with the item, “My life has meaning and purpose” rated from 1 (agree a lot) to 3 (agree not at all), which was reverse scored in the direction of greater purpose. Previous research has found that purpose in life assessed either with the Ryff measure or as meaning in life, measured with either single or multiple items, is associated significantly with physical health outcomes [15]. In addition, measures of purpose in life and meaning in life are associated equally with performance on episodic memory and verbal fluency tasks [16] and have similar protective associations with motoric cognitive risk syndrome [7]. This evidence suggests that the different measures across the studies capture a similar aspect of purpose that is relevant to cognitive health.

Cognitive status.

In the HRS, cognitive function was measured with the modified Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status (TICSm[17]. The TICSm is the sum of performance on three cognitive tasks: memory, serial 7s, and backward counting; scores ≤6 (out of a possible 27) is indicative of dementia [17]. In ELSA, dementia was defined as report of a physician diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease or dementia or an average score of ≥3.38 on the shortened version of the Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE), as reported by a knowledgeable proxy [18]. In TILDA, cognitive status was measured at each wave with the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)[19]. The MMSE measured cognitive function across a number of domains, including orientation, attention, memory, language and visual-spatial skills. An MMSE score <24 is indicative of dementia [20]. In the NHATS, cognitive function was measured as the sum of three tasks that measured memory (immediate and delayed word recall), orientation (date, month, year, day of the week, President and Vice President), and executive function (clock drawing)[12]. Dementia in NHATS was defined as doctor diagnosis of dementia/Alzheimer’s disease, a score of ≥2 on the AD8 Dementia Screening interview, or a score of ≤1.5 SD below the mean in at least two of three tasks [12].

Sociodemographic covariates.

Sociodemographic covariates were age in years, gender (male=0, female=1), race/ethnicity, and education. Race in HRS and NHATS was coded as African American and other versus white. Ethnicity in ELSA was coded as not white versus white (information on specific races/ethnicities in ELSA is not made public). TILDA does not report race/ethnicity. Education was reported in years in HRS, on a scale from 0 (no qualification) to 7 (degree) in ELSA, on a scale from 1 (some primary, not complete) to 7 (postgraduate/higher degree) in TILDA, and on a scale from 1 (no schooling) to 9 (graduate degree) in NHATS.

Clinical and behavioral covariates.

All clinical and behavioral covariates were scored as the presence of the risk factor (=1) versus its absence (=0). In all cohorts, participants reported a physician diagnosis of diabetes and hypertension and whether a current smoker. Obesity was defined as a body mass index ≥30. Depression was measured with an 8-item version of the Centers for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale in the HRS and ELSA, a 20-item version in TILDA, and with the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 in the NHATS. Scores of 3 and 16 were used in HRS/ELSA and TILDA, respectively, as the threshold for severe depressive symptoms for the CESD [21, 22]; a score of 3 was used as the threshold for the PHQ2 in the NHATS [23]. Two items measured the frequency of moderate and vigorous activity in HRS and ELSA; the mean was taken across the items and recoded such that the response “never or almost never” was contrasted as the risk group against the other frequencies. In TILDA, participants completed the International Physical Activity Questionnaire [24]. Low physical activity was contrasted against moderate and high physical activity. In NHATS, one item (yes/no) measured engagement in physical activity in the last month.

Literature Search

We conducted a systematic review of the literature to include the published studies in a meta-analysis with the primary data. We followed MOOSE guidelines for meta-analyses of observational studies [25]. We included studies published in an English language, peer-reviewed journal, that measured purpose in life or meaning in life at baseline, and prospectively followed participants to identify new cases of cognitive impairment. Studies based on cross-sectional or retrospective designs were excluded. All studies had to have a measure of purpose in life on a cognitively healthy sample at baseline and at least one subsequent follow-up measure of cognitive status. PubMed and Web of Science were used for a systematic literature search that covered all years from inception up to February 2021. Search terms were “purpose in life” OR “meaning in life” OR “life purpose” OR “life meaning” AND “dementia” OR “Alzheimer*” OR “cognitive impairment.” The literature search was conducted independently by two researchers (ARS and DA). Discrepancies were discussed and resolved at the end of the search. Titles and abstracts of each article were screened for eligibility. Full-text articles were assessed for inclusion, and data extracted from studies that met eligibility criteria. Google Scholar was used to conduct a similar search to identify additional studies through forward searches. The reference lists of studies that met eligibility criteria were also screened for additional studies. Eligible published studies were included in the meta-analysis.

Analytic Strategy

Cox regression was used to examine the risk of incident dementia over the follow-up in the primary samples. Time was coded as time-to-incidence from baseline to the first instance of dementia over the follow-up. Participants who did not develop dementia were censored at their last available assessment. In Model 1, purpose was used to predict risk of incident dementia over the follow-up, controlling for sociodemographic covariates. In Model 2, the clinical and behavioral risk factors were included as additional covariates. Moderation analyses tested whether the association between purpose and dementia risk varied by age, gender, or education in each sample. Finally, we did a random-effects meta-analysis to summarize the association between sense of purpose and risk of dementia across the four samples and the published studies identified through the literature search. A random effects meta-analysis was used because it is possible that the true effect size might differ across studies, especially because the samples were drawn from different populations. Q, tau, and I2 were used as measures of heterogeneity. Leave-one-out analyses were conducted to examine whether heterogeneity was driven by one specific study. Potential publication bias was examined by inspecting funnel plot asymmetry and the Egger’s test [26]. We applied a trim and fill procedure to obtain a bias-corrected estimate of the overall effect [27]. In supplemental analyses, we also used the precision-effect test and precision-effect estimate with standard errors (PET-PEESE)[28] to estimate the effect size expected in a study in which the standard error is zero but caution its interpretation because of the small number of samples included in the meta-analysis. We likewise summarized the moderation analyses with a random effects meta-analysis.

Results

Descriptive statistics for the four samples are in Table 1. Across the four cohorts (total N=30,034), follow up ranged from 1 to 17 years, with an average survival time of 7.08 years, and 4,824 participants developed incident dementia. The results of the Cox regressions in the four cohorts are in Table 2. Sense of purpose was protective against dementia in all cohorts, controlling for the sociodemographic covariates (Model 1). The association was slightly attenuated (by an average of <10%) but remained similar and statistically significant when the clinical and behavioral covariates were in the model (Model 2), which indicated that the association between purpose and dementia risk was not due entirely to these factors. There was one significant interaction between purpose and age in HRS (the association was apparent across age but slightly stronger among relatively younger than relatively older participants) that did not replicate in the other three samples (Table 3). None of the other interactions was significant (Table 3; additional information can be found in Supplemental Material). The lack of moderation indicated that purpose was similarly protective across age, gender, and level of education.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for All Study Variables in Each Cohort

| Variable | HRS | ELSA | TILDA | NHATS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline age (years) | 67.85 (9.49) | 64.10 (9.75) | 61.88 (8.82) | 76.84 (7.67) |

| Age range | 50–99 | 50–90+ | 50–80 | 65–105 |

| Gender (female) | 59.7% (7090) | 55.1 (4767) | 55.9 (2808) | 59.2% (2647) |

| Race (African American) | 11.6% (1378) | -- | -- | 20.1% (900) |

| Race (Other) | 4.1% (482) | 1.9% (163) | -- | 7.4% (331) |

| Educationa | 12.87 (2.88) | 3.30 (2.24) | 3.92 (1.56) | 5.27 (2.22) |

| Dementia (yes) | 15.3% (1816) | 6.6% (572) | 3.0% (152) | 51.1% (2284) |

| Survival time (years) | 8.58 (3.31) | 10.99 (5.34) | 5.47 (1.22) | 3.29 (2.27) |

| Survival time range | 1–13 | 1–17 | 2–6 | 1–7 |

| Purpose in lifeb | 4.64 (.92) | 3.58 (.70) | 3.74 (.57) | 2.86 (.35) |

| Risk Factors | ||||

| Hypertension (yes) | 57.7% (6647) | 37.1% (2883) | 34.2 (1682) | 66.6% (2899) |

| Diabetes (yes) | 19.2% (2213) | 6.4% (499) | 6.8% (334) | 24.1% (1051) |

| Obesity (yes) | 31.7% (3654) | 25.3 (1970) | 33.7 (1658) | 28.0% (1221) |

| Depression (yes) | 18.1% (2082) | 21.4% (1666) | 8.4% (412) | 12.9% (563) |

| Current smoker (yes) | 12.5% (1442) | 18.4% (1435) | 14.6 (719) | 7.4% (322) |

| Physically inactive (yes) | 16.1% (1858) | 14.1 (1096) | 28.5 (1403) | 60.8% (2648) |

| N c/d | 11,877/11,520 | 8,657/7,781 | 5,027/4,917 | 4,473/4,354 |

Note. HRS=Health and Retirement Study. ELSA=English Longitudinal Study of Aging. TILDA= The Irish LongituDinal study on Ageing. NHATS= National Health Trends and Aging Study.

Education was reported in years in HRS and reported on a scale from 0 (no qualification) to 7 (degree) in ELSA, on a scale from 1 (some primary, not complete) to 7 (postgraduate/higher degree) in TILDA, and on a scale from 1 (no schooling) to 9 (graduate degree) in NHATS.

Reported on a 6-point scale in HRS, on a 4-point scale in ELSA and TILDA, and on a 3-point scale in NHATS.

Sample size.

Sample size with complete information on the clinical and behavioral risk factors.

Table 2.

Survival Analysis Predicting Incident Dementia from Purpose in Life in Four Samples

| Variable | HRS | ELSA | TILDA | NHATS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | ||||

| Age (years) | 1.09 (1.08–1.10)** | 1.14 (1.13–1.15)** | 1.11 (1.09–1.13)** | 1.04 (1.03–1.04)** |

| Gender (female) | .95 (.87–1.05) | .88 (.74–1.04) | .76 (.55–1.05) | .76 (.70–.82)** |

| Race (African American) | 2.09 (1.85–2.37)** | -- | -- | 1.42 (1.29–1.58)** |

| Race (Other) | 1.43 (1.14–1.80)** | 1.51 (.83–2.75) | -- | 1.38 (1.18–1.61)** |

| Education | .89 (.88–.90)** | .94 (.90–.98)** | .66 (.58–.74)** | .92 (.90–.94)** |

| Purpose in life | .77 (.74–.81)** | .77 (.69–.85)** | .70 (.57–.85)** | .77 (.69–.86)** |

| Model 2 | ||||

| Age (years) | 1.09 (1.08–1.10)** | 1.14 (1.13–1.15)** | 1.11 (1.08–1.13)** | 1.04 (1.03–1.05)** |

| Gender (female) | .90 (.82–.99)* | .85 (.71–1.02) | .68 (.49–.95)* | .68 (.68–.80)** |

| Race (African American) | 2.04 (1.79–2.32)** | -- | -- | 1.36 (1.22–1.51)** |

| Race (Other) | 1.38 (1.08–1.76)** | 1.03 (.49–2.19) | -- | 1.38 (1.18–1.62)** |

| Education | .90 (.89–.91)** | .95 (.91–.99)* | .68 (.60–.78)** | .93 (.91–.95)** |

| Hypertension (yes) | 1.04 (.94–1.16) | 1.07 (.89–1.28) | 1.03 (.73–1.45) | 1.08 (.98–1.18) |

| Diabetes (yes) | 1.17 (1.04–1.32)** | 1.65 (1.22–2.22)** | 1.49 (.94–2.36) | 1.06 (.96–1.17) |

| Obesity (yes) | .83 (.74–.92)** | 1.07 (.88–1.31) | .98 (.70–1.38) | 1.12 (1.02–1.23)* |

| Depression (yes) | 1.49 (1.33–1.67)** | 1.26 (1.02–1.56)* | 1.55 (.94–2.58) | 1.27 (1.12–1.43)** |

| Current smoker (yes) | 1.39 (1.19–1.61)** | 1.36 (1.05–1.76)* | 1.54 (1.01–2.37)* | 1.08 (.92–1.27) |

| Physically inactive (yes) | 1.22 (1.08–1.37)** | 1.32 (1.05–1.65)* | 1.71 (1.22–2.39)** | 1.03 (.94–1.13) |

| Purpose in life | .82 (.78–.87)** | .81 (.72–.90)** | .75 (.61–.92)** | .80 (.71–.90)** |

Note. Coefficients are hazards ratios (95% confidence interval) from Cox regression. HRS=Health and Retirement Study. ELSA=English Longitudinal Study of Aging. TILDA= The Irish LongituDinal study on Ageing. NHATS= National Health Trends and Aging Study. N (Model 1/Model 2)=11,877/11,520 for HRS; 8.657/7,781 for ELSA; 5,027/4,917 for TILDA; 4,473–4,354 for NHATS.

p<.05.

p<.01.

Table 3.

Risk of incident dementia associated with life purpose reported in each study, meta-analytical effect sizes, and heterogeneity

| Study | N | HR (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main Model | Clinical/Behavioral Covariates | Age | Gender | Education | ||

| Rush MAP | 951 | 0.480 (0.330 – 0.690) | – | – | – | – |

| SHARE | 22,514 | 0.806 (0.763 – 0.855) | – | – | – | – |

| HRS | 11,877 | 0.773 (0.735 – 0.813) | 0.825 (0.782 – 0.871) | 1.011 (1.006 – 1.016) | 0.974 (0.880 – 1.077) | 0.992 (0.977 – 1.007) |

| ELSA | 8,657 | 0.768 (0.694 – 0.850) | 0.807 (0.721 – 0.904) | 1.003 (0.994 – 1.013) | 0.841 (0.683 – 1.034) | 0.996 (0.947 – 1.048) |

| TILDA | 5,027 | 0.696 (0.570 – 0.850) | 0.750 (0.607 – 0.925) | 1.009 (0.987 – 1.032) | 0.872 (0.583 – 1.304) | 1.106 (0.929 – 1.316) |

| NHATS | 4,473 | 0.773 (0.692 – 0.864) | 0.798 (0.711 – 0.895) | 1.008 (0.884 – 1.023) | 1.029 (0.822 – 1.289) | 0.999 (0.948 – 1.054) |

| Meta-analytic results | ||||||

| k | 6 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | |

| random model (95% CI) | 0.768 (0.727 – 0.812) | 0.815 (0.780 – 0.851) | 1.008 (1.002 – 1.013) | 0.954 (0.878 – 1.036) | 0.993 (0.980 – 1.007) | |

| z (p-value) | −9.48 (<.001) | −9.15 (<.001) | 2.84 (<.010) | −1.11 (.266) | −0.92 (.357) | |

| tau2 | .043 | 0.00 | 0.003 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| I2 (in %) | 46.81 | 0.00 | 19.04 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Q (p-value); df | 9.40 (.094); 5 | 0.95 (.813); 3 | 3.70 (0.295); 3 | 2.21 (0.530); 3 | 1.55 (0.671); 3 | |

Note. Rush MAP = Rush Memory and Aging Project; SHARE = Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe; HRS = Health Retirement Study; ELSA = English Longitudinal Study of Aging; TILDA = Irish Longitudinal Study on Aging; NHATS = National Health and Aging Trends Study; N = number of participants; HR = hazard ratio; 95% CI = 95% confidence intervals; k = number of studies. Between-study heterogeneity was quantified using tau2, Q and I2 values, however, these statistics tend to be underpowered in view of the small numbers of studies and inference about heterogeneity should be made with caution. N refers to the main model, with varying N’s for the model that included clinical/behavioral covariates (HRS = 11,520; ELSA = 7,778; TILDA = 4,917; NHATS = 4,354) and the models that included the moderators (HRS = 11,877; ELSA = 8,657; TILDA = 5,027; NHATS = 4,473).

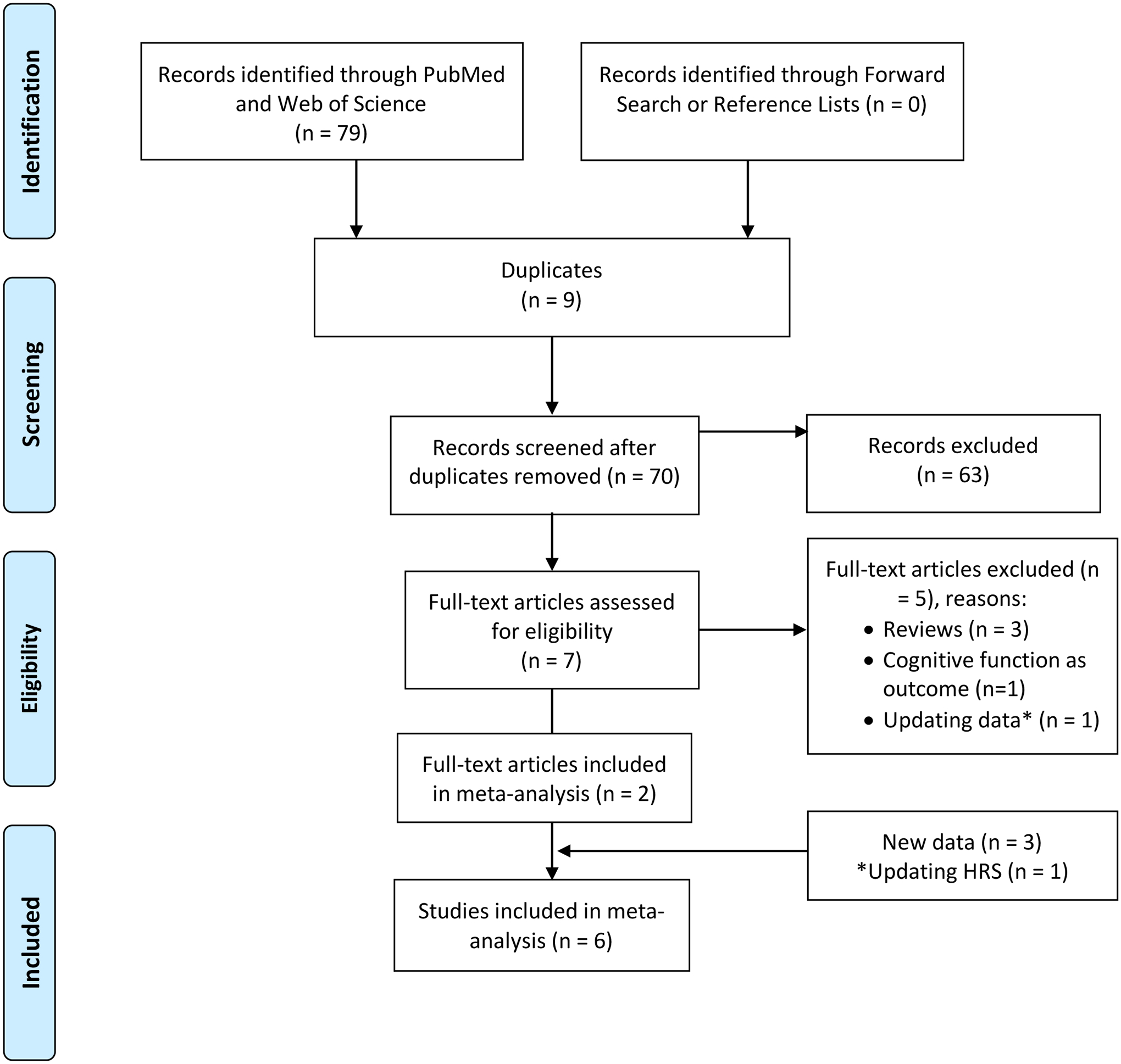

The systematic review of the literature (Figure 1) identified three published studies on purpose and incident dementia risk [4, 8, 29]. We excluded one of these studies [8] because it overlapped with the current HRS sample. The two identified studies used data from the Rush Memory and Aging Project (Rush MAP) [4] and the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) [8]. Rush MAP is a longitudinal study of older adults in the Chicago, IL area. Most participants were women (74.9%) and white (91.85) and at the baseline assessment had a mean age of 80.4 (SD=7.4) years old. The mean follow-up time was 4 years, with a range of 1–7 years. SHARE is a multinational longitudinal study of the health of individuals over the age of 50 years old and their spouses in Europe. Samples were available from Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland. Participants were 55.7% female with an average age of 63.88 (SD=9.01) years old at baseline. The mean follow-up time was 7 years, with a range from 3–9 years.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram.

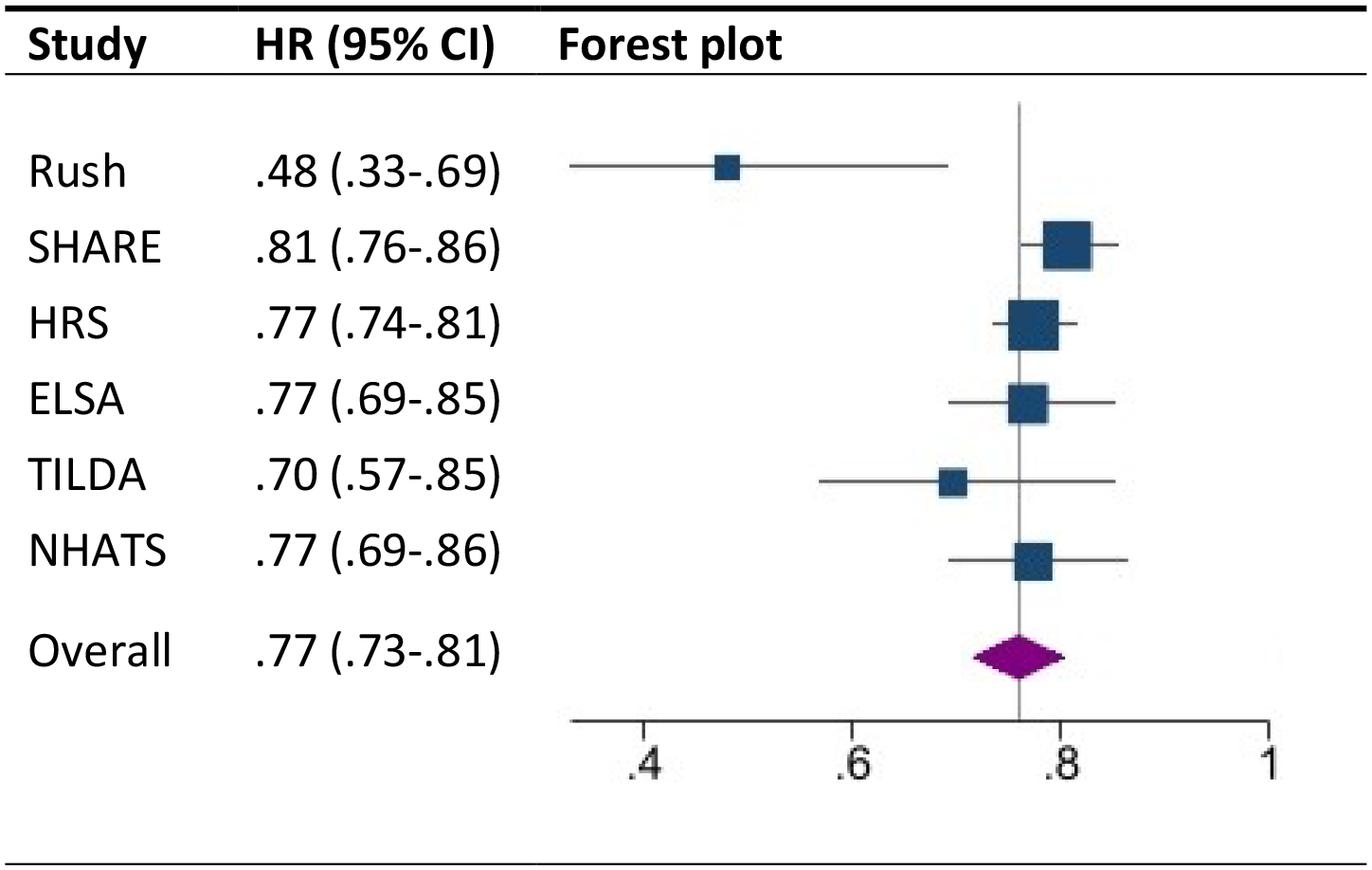

The six studies (2 previously published and the 4 current samples) included 53,499 participants at baseline and 5,862 incident ADRD cases over the follow-up. The meta-analysis of the six studies indicated that a higher sense of life purpose was associated with decreased dementia risk (HR = 0.77, 95% CI [0.73, 0.81], p < .001). Of these six studies, all had a significant hazard ratio and were similar in the two published studies and the new four cohorts (Figure 2). The leave one out analysis confirmed that the meta-analytic effect was not dependent on any single study. The measures of heterogeneity suggested modest (Q = 9.40, df = 5, p = .094; tau = .043) to moderate (I2 = 47%) heterogeneity.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the association between purpose and the risk of incident dementia

Note. The plot summarizes the individual study estimates and the average effect of the random effects model. Effect sizes are displayed in hazard ratios (HR) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Rush MAP = Rush Memory and Aging Project; SHARE = Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe; HRS = Health Retirement Study; ELSA = English Longitudinal Study of Aging; TILDA = The Irish Longitudinal Study on Aging; NHATS = National Health and Aging Trends Study.

There was some evidence of publication bias as indicated by the Egger’s test (t = −2.86, p=.046), which suggested that small-study effects exist (small studies predominately in direction of larger effect sizes). The smallest study with the largest effect was the only one with a clinical diagnosis of dementia, and thus the small-study effects may reflect methodological differences more than selective reporting. The bias-corrected trim and fill estimate of effect size, however, was essentially identical to that obtained in the primary model (HR = 0.78, 95% CI [0.76, 0.81]). See supplemental material for the results of the PET-PEESE analyses, which should be interpreted with caution given the small number of studies included in the meta-analysis.

Discussion

Across four samples and the published literature, a sense of purpose in life was associated with reduced risk of dementia over a span of up to 17 years. Across these six studies, purpose was associated consistently with an average of nearly 30% decreased risk of incident dementia. This association was apparent across demographic groups and was robust to behavioral and clinical risk factors associated with both purpose and dementia risk. The present research thus indicates a replicable and robust association between a sense of life purpose and lower risk of developing a significant cognitive impairment.

A sense of purpose in life helps organize and motivate behavior, relationships, and day-to-day strivings that form a clear sense of direction for the individual to achieve longer-term goals [30]. Such goals typically reflect the individual’s core values and are central to their identity [31]. A sense of purpose is considered one component of a meaningful life [3]. And, although conceptually distinct, the relation between purpose in life and meaning in life and health outcomes are similar [15] including for cognitive outcomes [16]. The beneficial effects of a purposeful and meaningful life thus extend far beyond the ability to motivate one’s behaviors to achieve distal goals, including to cognitive health.

There are a number of mechanisms that may explain why purpose is associated with lower dementia risk. The clinical and behavioral factors in the current study are robust predictors of dementia risk [1]. These risk factors have also been associated with purpose: individuals with more purposeful lives tend to be less likely to develop diabetes [32] and have fewer cardiovascular events [33], are more likely to fall in the normal category of body weight [34], are less prone to depression [35] and have healthier behavioral patterns, including less smoking [36] and more physical activity [37]. It is of note, then, that accounting for these factors slightly attenuated but did not account for all of the association between purpose and dementia risk.

This pattern suggests that there are other pathways through which purpose may promote healthier cognitive outcomes. Greater daily engagement might be one key mechanism that protects cognition. Individuals higher in purpose experience more positive affect and less negative affect [38]. They also have more attention and concentration and greater persistence [30]. Individuals higher in purpose engage in more cognitively demanding activities in their daily lives [39] that promote healthier cognitive aging [40]. These various forms of engagement may help keep the brain active and protect it from decline with age. Social mechanisms associated with purpose may also help protect cognitive function in older adulthood. Individuals who feel their lives are purposeful are less likely to feel lonely [41] and are more likely to engage in social activities, such as volunteering [42]. Greater social integration promotes healthier cognitive function [43] and protects against the development of cognitive impairments [44]. A sense of purpose in life may thus be a higher-order factor that contributes to better cognitive health via numerous forms of engagement and lifestyle choices.

The present research indicates that the protective relation between sense of purpose and dementia risk is similar across demographic populations. Specifically, the associations were similar across relatively younger versus relatively older adults, males and females, and across level of education. The only interaction that emerged (with age) in one sample did not replicate in the other three samples. This consistency across demographic groups indicates that the protective effect is generalizable and not limited to individuals with the most resources. In fact, there is evidence that purpose is more protective of cognition in environments with fewer resources [16]. Purpose in life may thus be a psychological resource that benefits a broad swath of society, and even more so for those with the fewest financial resources.

A sense of purpose is modifiable and thus may be an effective target of intervention to improve cognitive outcomes. In particular, there is consistent evidence that purpose in life can be increased through intervention [45]. These interventions were developed with psychological outcomes in mind (e.g., improved well-being). Such interventions may also benefit cognitive health. Purpose-based interventions could be adapted for cognitive health and are likely to have broad benefits also for other healthier aging-related outcomes.

There are a number of limitations that could be addressed in future research. First, there are relatively few longitudinal studies with relevant data to address this association. This issue is a particular limitation for assessing heterogeneity and publication bias because there were fewer studies than the minimum 10 recommended samples for these statistics. The small number of samples may bias the estimates because they are based on few studies. Still, the consistency across studies gives some confidence that there is an association between sense of purpose and dementia, even if more studies are needed to better identify the magnitude of the association. Second, all of the samples come from higher income, Western countries. More longitudinal research, especially in middle- and lower-income countries and from Eastern cultures is needed to assess the generalizability of the associations. Purpose may be particularly relevant to help partly compensate for lower financial status when it comes to cognitive health [16]. Third, only one study from the published literature had a clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease; all of the other studies relied on performance-based and reported assessments of dementia. Future research would benefit from more samples based on a clinical diagnosis. It is of note, however, that the pattern of association was similar across the various assessments of cognitive impairment. It is also of note that the largest effect was in the study that used a clinical diagnosis, which suggests that the meta-analysis slightly underestimates the actual effect because it is based primarily on performance-based measures. Despite these limitations, the present research demonstrated the robustness of the association between a sense of purpose in life and risk of incident dementia: The meta-analysis indicated that sense of purpose was associated with a nearly 30% reduced risk of dementia. Purpose in life may thus be a worthwhile target of intervention to promote healthier cognitive aging across adulthood.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

We gratefully acknowledge the parent studies whose public data made this work possible: Health and Retirement Study (HRS): The Health and Retirement Study is sponsored by the National Institute on Aging (NIA-U01AG009740) and conducted by the University of Michigan. English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA): Funding for the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing is provided by the National Institute of Aging [grants 2RO1AG7644-01A1 and 2RO1AG017644] and a consortium of UK government departments coordinated by the Office for National Statistics. The Irish LongituDinal Study on Ageing (TILDA): We thank TILDA participants and the Irish Social Science Data Archive (ISSDA) at University College Dublin http://www.ucd.ie/issda/data/tilda/ for making the data available. The National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS) is sponsored by the National Institute on Aging (grant number U01AG032947) through a cooperative agreement with the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the parent studies or funders. Data can be downloaded or access requested from parent studies (urls provided in the Method).

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers R01AG053297 (ARS) and R01AG068093 (AT). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to report.

References

- [1].Norton S, Matthews FE, Barnes DE, Yaffe K, and Brayne C (2014) Potential for primary prevention of Alzheimer’s disease: an analysis of population-based data. Lancet Neurol 13, 788–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Ryff CD (2014) Psychological well-being revisited: advances in the science and practice of eudaimonia. Psychother Psychosom 83, 10–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Martela F, Steger MF (2016) The three meanings of meaning in life: Distinguishing coherence, purpose, and significance. J Pos Psychol 11, 531–545. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Boyle PA, Buchman AS, Barnes LL, Bennett DA (2010) Effect of a purpose in life on risk of incident Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment in community-dwelling older persons. Arch Gen Psychiatry 67, 304–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Lewis NA, Turiano NA, Payne BR, Hill PL (2017) Purpose in life and cognitive functioning in adulthood. Neuropsychol Dev Cogn B Aging Neuropsychol Cogn 24, 662–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Kim G, Shin SH, Scicolone MA, Parmelee P (2019) Purpose in life protects against cognitive decline among older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 27, 593–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Sutin AR, Luchetti M, Stephan Y, Terracciano A (2021) Purpose in life and motoric cognitive risk syndrome: Replicable evidence from two national samples. J Am Geriatr Soc 69, 381–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Sutin AR, Stephan Y, Terracciano A (2018) Psychological well-being and risk of dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 33, 743–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Sonnega A, Faul JD, Ofstedal MB, Langa KM, Phillips JW, Weir DR (2014) Cohort profile: the Health and Retirement Study (HRS). Int J Epidemiol 43, 576–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Steptoe A, Breeze E, Banks J, Nazroo J (2013) Cohort profile: the English longitudinal study of ageing. Int J Epidemiol, 42, 1640–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Kearney PM, Cronin H, O’Regan C, Kamiya Y, Savva GM, Whelan B, Kenny R (2011) Cohort profile: the Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing,” Int J Epidemiol, 40, 877–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Freedman VA Kasper JD (2019) Cohort profile: The National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS). Int J Epidemiol, 48, 1044–1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ryff CD (1989) Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol 57, 1069–1081. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Hyde M, Wiggins RD, Higgs P, Blane DB (2003) A measure of quality of life in early old age: the theory, development and properties of a needs satisfaction model (CASP-19). Aging Ment Health 7, 186–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Czekierda K, Banik A, Park CL, Luszczynska A (2017) Meaning in life and physical health: systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Psychol Rev 11, 387–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Sutin AR, Luchetti M, Stephan Y, Strickhouser JE, Terracciano A (2021) The association between purpose/meaning in life and verbal fluency and episodic memory: A meta-analysis of >140,000 participants from up to 32 countries. International Psychogeriatrics, doi: 10.1017/S1041610220004214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Crimmins EM, Kim JK, Langa KM, Weir DR (2011) Assessment of cognition using surveys and neuropsychological assessment: the Health and Retirement Study and the Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci, 66, i162–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Fancourt D, Steptoe A, Cadar D (2020) Community engagement and dementia risk: time-to-event analyses from a national cohort study. J Epidemiol Community Health 74, 71–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Folstein FM, Folstein SE, Fanjiang G (2001) Mini-Mental State Examination: Clinical Guide and User’s Guide. Lutz, FL. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Creavin ST, Wisniewski S, noel-Storr AH, Trevelyan CM, Hampton T, Rayment D, Thom VM, Nash KJE, Elhamoui H, Milligan R, Patel AS, Tsivos DV, Wing T, Phillips E, Kellman SM, Shackleton HL, Singleton GF, Neale BE, Watton ME, Cullum S (2016) Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) for the detection of dementia in clinically unevaluated people aged 65 and over in community and primary care populations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1, CD011145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Bergmans RS, Zivin K, Mezuk B (2019) Depression, food insecurity and diabetic morbidity: Evidence from the Health and Retirement Study. J Psychosom Res 117, 22–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Weissman MM, Sholomskas D, Pottenger M (1977) Assessing depressive symptoms in five psychiatric populations: A validation study. Am J Epidemiol 106, 203–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB (2003) The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care 41, 1284–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjostrom M, Bauman AE, Booth ML, Ainsworth BE, Pratt M, Ekelund U, Yngve A, Sallis JF, Oja P (2003) International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc 8, 1381–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson D, Drummond R, Moher D, Becker BJ, Sipe TA, Thacker SB, for the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiolgy (2000) Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA 283, 2008–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C (1997) Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 315, 629–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Duval S, Tweedie R (2000) Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics 56, 455–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Stanley TD, Doucouliagos H (2014) Meta-regression approximations to reduce publication selection bias. Res Synth Methods 5, 60–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Sutin AR, Luchetti M, Stephan Y, Terracciano A (2020) Meaning in life and risk of cognitive impairment: A 9-year prospective study in 14 countries. Arch Gerontol Geriatric 88, 104033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].McKnight PE, Kashdan TB (2009) Purpose in life as a system that creates and sustains health and well-being: An integrative, testable theory. Rev Gen Psychol 13, 242–251. [Google Scholar]

- [31].George LS, Park CL (2016) Meaning in life as comprehension, purpose, and mattering: Toward integration and new research questions. Rev Gen Psychol 20, 205–220. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Hafez D, Heisler M, Choi H, Ankuda CK, Winkelman T, Kullgren JT (2018) Association between purpose in life and glucose control among older adults. Ann Behav Med 52, 309–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Cohen R, Bavishi C, Rozanski A (2016) Purpose in life and its relationship to all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events: a meta-analysis. Psychosom Med 78, 122–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Sutin AR, Stephan Y, Luchetti M, Aschwanden D, Strickhouser JE, Lee JH, Sesker AA, Terracciano A (2021) Body mass index, weight discrimination, and the trajectory of distress and well-being across the coronavirus pandemic. Obesity 29, 38–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Wood AM, Joseph S (2010) The absence of positive psychological (eudemonic) well-being as a risk factor for depression: a ten year cohort study. J Affect Disord 122, 213–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Morimoto Y, Yamasaki S, Ando A, Koike S, Fujikawa S, Kanata S, Endo K, Nakanishi M, Hatch SL, Richards M, Kasai K, Hiraiwa-Hasegawa M, Nishida A (2018) Purpose in life and tobacco use among community-dwelling mothers of early adolescents. BMJ Open 8, e020586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Hooker SA, Masters KS (2016) Purpose in life is associated with physical activity measured by accelerometer. J Health Psychol 21, 962–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Scheier MF, Wrosch C, Baum A, Cohen S, Matire LM, Matthews KA, Schulz R, Zdaniuk B (2006) The Life Engagement Test: assessing purpose in life. J Behav Med 29, 291–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Mei Z, Lori A, Vattahil SM, Boyle PA, Bradley B, Jin P, Bennett DA, Wingoo TS, Wingo AP (2021) Important correlates of purpose in life identified through a machine learning approach. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 29, 488–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Verghese J, Lipton RB, Katz MJ, Hall CB, Derby CA, Kuslansky G, Ambrose AF, Sliwinski M, Buschke H (2003) Leisure activities and the risk of dementia in the elderly. N Engl J Med 348, 2508–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Mwilambwe-Tshilobo L, Ge T, Chong M, Ferguson MA, Misic B, Burrow AL, Leahy RM, Spreng RN (2019) Loneliness and meaning in life are reflected in the intrinsic network architecture of the brain. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 14, 423–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Jongenelis MI, Dana LM, Warburton J, Jackson B, Newton RU, Talati Z, Pettigrew S (2020) Factors associated with formal volunteering among retirees. Eur J Ageing 17, 229–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Proulx CM, Curl CL, Ermer AE (2018) Longitudinal associations between formal volunteering and cognitive functioning. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 73, 522–531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Sutin AR, Stephan Y, Luchetti M, Terracciano A. (2020) Loneliness and risk of dementia. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 75, 1414–1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Park CL, Pustejovsky JE, Trevino K, Sherman AC, Esposito C, Berendsen M, Salsman JM. (2019) Effects of psychosocial interventions on meaning and purpose in adults with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer 125, 2383–2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.