Keywords: functional dyspepsia, gastric accommodation, gastrointestinal motility, vagal nerve stimulation, visceral pain

Abstract

This study was designed to investigate whether transcutaneous auricular vagal nerve stimulation (taVNS) would be able to improve major pathophysiologies of functional dyspepsia (FD) in patients with FD. Thirty-six patients with FD (21 F) were studied in two sessions (taVNS and sham-ES). Physiological measurements, including gastric slow waves, gastric accommodation, and autonomic functions, were assessed by the electrogastrogram (EGG), a nutrient drink test and the spectral analysis of heart rate variability derived from the electrocardiogram (ECG), respectively. Thirty-six patients with FD (25 F) were randomized to receive 2-wk taVNS or sham-ES. The dyspeptic symptom scales, anxiety and depression scores, and the same physiological measurements were assessed at the beginning and the end of the 2-wk treatment. In comparison with sham-ES, acute taVNS improved gastric accommodation (P = 0.008), increased the percentage of normal gastric slow waves (%NSW, fasting: P = 0.010; fed: P = 0.007) and vagal activity (fasting: P = 0.056; fed: P = 0.026). In comparison with baseline, 2-wk taVNS but not sham-ES reduced symptoms of dyspepsia (P = 0.010), decreased the scores of anxiety (P = 0.002) and depression (P < 0.001), and improved gastric accommodation (P < 0.001) and the %NSW (fasting: P < 0.05; fed: P < 0.05) by enhancing vagal efferent activity (fasting: P = 0.015; fed: P = 0.048). Compared with the HC, the patients showed increased anxiety (P < 0.001) and depression (P < 0.001), and decreased gastric accommodation (P < 0.001) and %NSW (P < 0.001) as well as decreased vagal activity (fasting: P = 0.047). The noninvasive taVNS has a therapeutic potential for treating nonsevere FD by improving gastric accommodation and gastric pace-making activity via enhancing vagal activity.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Treatment of functional dyspepsia is difficult due to various pathophysiological factors. The proposed method of transcutaneous auricular vagal nerve stimulation improves symptoms of both dyspepsia and depression/anxiety, and gastric functions (accommodation and slow waves), possibly mediated via the enhancement of vagal efferent activity. This noninvasive and easy-to-implement neuromodulation method will be well received by patients and healthcare providers.

INTRODUCTION

Functional dyspepsia (FD) is a common functional gastrointestinal (GI) disease and impacts on the quality of life among affected patients. The prevalence of FD has been reported to be 10%–30% worldwide (1). According to the Rome IV criteria, functional dyspepsia is originated from the gastroduodenum but is not secondary to organic, systemic, or metabolic diseases, with one or more of the following symptoms: postprandial fullness, early satiation, epigastric pain, and epigastric burning (2). Rome IV classification of FD involves postprandial distress syndrome (PDS), epigastric pain syndrome (EPS), and PDS-EPS overlap (3). Major pathophysiological mechanisms of FD include reduced gastric accommodation, visceral hypersensitivity, delayed gastric emptying, gastric dysrhythmia, and sympathetic/vagal dysfunctions (4).

Current treatment options for FD include antacids, prokinetic agents, fundus-relaxing drugs, anxiolytics, and antidepressants. Anti-acid drugs are more likely to be effective in the presence of epigastric burning and pain. Prokinetic agents may be used for treating early satiation and postprandial fullness but often impair gastric accommodation. Fundus-relaxing drugs can improve gastric accommodation, but these drugs may delay gastric emptying and have vascular side effects (5, 6). In general, targeted treatment for potential pathophysiological mechanisms can often achieve satisfactory results. However, the efficacy is usually limited due to the diversity of individual symptoms and various pathophysiologies. In addition, patients with dyspepsia have concerns on the growing healthcare expenditures and side effects of drugs. Consequently, complementary and alternative therapies are being increasingly explored and of great clinical significance for FD (7).

Acupuncture is a traditional Chinese medicine treatment that involves the insertion of the tip of a thin needle through the skin into a specific point and the delivery of stimulation manually or electrically (8). Transcutaneous electrical acustimulation (TEA) is a modified form of acupuncture by delivering electrical current with cutaneous electrodes instead of electronic needles. The noninvasiveness and safety profile of TEA has gained progressive acceptance from patients and clinicians (9). Acupuncture and TEA have been applied for treating a variety of GI diseases such as functional dyspepsia, gastroparesis, and constipation (10–12).

In recent years, transcutaneous auricular vagal nerve stimulation (taVNS) or auricular electroacupuncture (AEA) has been introduced in both scientific research and clinical settings (13, 14). Previously, taVNS has been used for treating depression (15), epilepsy (16), and other neurological disorders (17). Our animal experiments showed that AEA could improve visceral hypersensitivity (18), gastric myoelectrical dysrhythmia (19), and delayed gastric emptying (20) by regulating the imbalance of autonomic nervous system. However, it is unclear whether such a method is also effective in treating patients with FD. Since patients with FD are reported to exhibit reduced vagal tone and increased sympathetic activity, autonomic function may play an important role in gastric function of FD (4). The auricular branches of vagus nerve are located in the auricular concha area that is the only afferent vagus nerve distribution place on the surface of the human body (21). Conceptually, taVNS is a new method known to enhance vagal activity. Therefore, we hypothesize that the noninvasive taVNS method would improve dyspeptic symptoms in patients with FD via enhancing vagal activity.

Accordingly, the aim of our clinical study was to investigate the effects of taVNS on symptoms and gastric functions (gastric slow waves and accommodation) in patients with FD and explore the possible mechanisms involving autonomic functions. In addition to the noninvasive application of the electrical stimulation, the gastric and autonomic functions were also assessed using noninvasive methods.

METHODS

Subjects

Patient inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) age: 18–65 yr old, 2) meeting the ROME IV criteria of FD, and 3) willing to sign the informed consent. Exclusion criteria for patients were as follows: 1) taking medications affecting GI motility within 1 wk before the recruitment or could not quit these medications, 2) pregnancy and planning to conceive a baby, 3) history of GI surgery, 4) allergic to skin preparation or adhesive tapes, and 5) familiar with acupuncture points and their functions. Inclusion criteria for healthy controls (HCs) include the following: 1) age: 18–65 yr old; 2) willing to sign the informed consent; 3) no previous GI disease, including peptic ulcer, FD, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and hepatobiliary or pancreatic diseases; 4) no history of abdominal surgery; and 5) no systemic illness and endocrine diseases.

Study Approval

For this randomized, double-blinded, sham-controlled study, patients with FD and HC were enrolled from July 2018 to December 2018 in the outpatient gastroenterology clinic of Yinzhou People’s Hospital. The experimental protocol was approved by the Ethical Review Committee of Yinzhou People’s Hospital (No. 2018018) and was carried out in accordance with CONSORT guidelines and regulations. All subjects signed an informed consent form before participation in the study.

Randomization and Blinding

Eligible patients were randomized into two groups with a 1:1 ratio according to a SPSS random digital table. All randomization assignments were prepacked in envelopes and consecutively numbered for each participant according to the randomization schedule. The sample size was estimated using previous data and power analysis (10, 22, 23).

As a double-blinded trial, both physicians and patients were blinded to treatment modality (taVNS versus sham-ES) and received the randomly assigned intervention in the envelope. Once enrolled, patients were trained how to put the electrodes and how to set intensity and turn on/off the machine by caregivers. Patients did not meet each other during the entire experiment and did not know personal experience of different treatment modality they received. The clinical outcomes including demographic data, symptom questionnaires, and physiological measurements performed according to the nutrient satiety test (see below) were assessed by blinded investigators.

Experimental Protocol

This study consisted of an acute experiment and a chronic experiment.

Acute experiment.

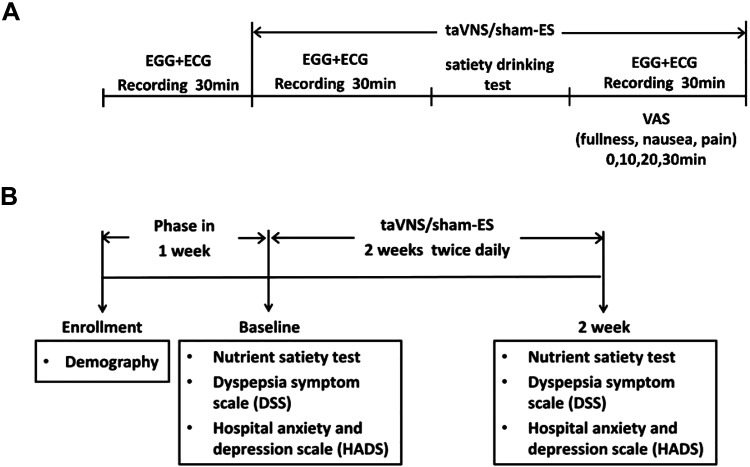

Patients (n = 36) were studied in two sessions in a randomized order on two separate days with an interval of 1 wk in the morning: a taVNS session and a sham-ES session. The protocol was as follows: 30-min baseline recording, 30-min taVNS/sham-ES treatment in the fasting state, a satiety drinking test conducted with a liquid meal (100 g milk powder, 50 g chocolate powder (Cola Coa, Idilia Foods), and 1,120 mL water; 0.6 Cal/mL, fat: 19%, protein: 18%, carbohydrate: 63%) with taVNS/sham-ES stimulation, and then a 30-min postprandial period with taVNS/sham-ES. Immediately after the drink, symptoms of fullness, nausea, and pain were assessed using the visual analog scale (0–100 in steps of 5 with 100 for most severe symptom) at time points 0, 10, 20, and 30 min. The electrogastrogram (EGG for assessing gastric slow waves) and electrocardiogram (ECG for assessing autonomic function) were recorded during the entire experimental period except during the satiety drinking test (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

Experimental protocol. A: acute experimental protocol. The electrogastrogram (EGG for assessing gastric slow waves) and electrocardiogram (ECG for assessing autonomic function) were recorded during the entire experimental period except during the satiety drinking test. B: chronic experimental protocol. The dyspeptic symptom scale, anxiety, and depression score were assessed and physiological measurements (EGG and ECG) were also taken via the nutrient satiety test before and after the treatment. ECG, electrocardiogram; EGG, electrogastrogram.

Chronic experiment.

Thirty-six patients and thirty-nine healthy controls (only for baseline recordings without the treatment) were enrolled. The patients (n = 36) were randomized to receive 2-wk taVNS (n = 18) or 2-wk sham-ES (n = 18). taVNS or sham-ES was performed 1 h twice daily (30 min after breakfast and dinner) for 2 wk. The dyspeptic symptom scales, anxiety, and depression scores were assessed at the beginning and the end of 2-wk treatment. Physiological measurements (EGG and ECG) were also taken via the nutrient satiety test (see Nutrient Satiety Test) before and after the treatment approximately at the same time in the morning to assess the effect of taVNS/sham-ES (Fig. 1B). In addition, a total of 39 HC (23 females; mean age: 43.8 yr) were recruited and subjected to a one-time nutrient satiety test (the same as stated above) together with the recordings of ECG and EGG.

taVNS and Sham-ES

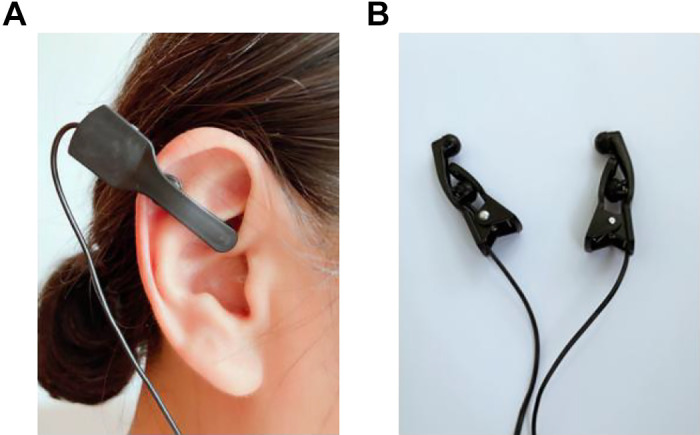

Both taVNS and sham-ES were performed using a watch-sized stimulator (SNM-FDC01, Ningbo Maida Medical Device, Inc., Ningbo, China). The stimulation points for taVNS were located in the bilateral auricular cymba concha areas that are richly innervated with the vagus nerve. After the auricular skin was cleaned with alcohol, one electrode clip was attached to one ear as shown in Fig. 2A and the other electrode on the other ear. The electrode tip made of carbon (see Fig. 2B) was placed in the cymba concha (Fig. 2A). The selection of bilateral stimulation was based on our previous animal studies (18, 20). The stimulation point for sham-ES was ∼15 cm up (to the elbow) and lateral to the arm wrist. These points were used in previous studies for sham stimulation (24–26). Both taVNS and sham-ES were performed using following stimulation parameters previously known to enhance vagal efferent activity: a train on-time of 2 s and off-time of 3 s, pulse width of 0.5 s, pulse frequency of 25 Hz, and pulse amplitude of 0.5 mA to 1.5 mA (the exact value was determined based on the tolerance of the patient) (18, 23).

Figure 2.

Method of transcutaneous auricular vagal nerve stimulation. A: one electrode clip was attached to one ear in the cymba concha and the other electrode on the other ear. B: the electrode tip made of carbon was placed in the cymba concha.

Dyspepsia Symptom Scale

A questionnaire with nine dyspeptic symptoms (10, 27) was completed by the patients, including upper abdominal pain, upper abdominal burning, postprandial fullness, early satiety, nausea, bloating, excessive belching, retching, and loss of appetite. Each symptom was graded based on severity (0–3: none-severe) and frequency (0–3: none-continuous all day).

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

A previously validated Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) questionnaire was used to assess effects of chronic taVNS on anxiety and depression. It included 14 questions about anxiety and depression (28). Anxiety and depression scores were assessed using the method (28) at the beginning and the end of the 2-wk treatment. The higher the score, the more anxiety and depression the patient had.

Assessment of Gastric Pace-Making Activity by Electrogastrogram

A four-channel electrogastrogram (EGG) device (MEGG-04A, Ningbo Maida Medical Device, Ningbo, Zhejiang, China) was used to record gastric slow waves noninvasively with a filtering setting of 0.0083–1 Hz. Patients were in a supine position and asked not to talk or read during the test. First, the abdominal skin was cleaned with a special gel (Nuprep, Weaver and Company, Aurora, CO). Then, conductive gel (Ten20, Weaver and Company, Aurora, CO) was applied to reduce skin-electrode impedance. Lastly, six cutaneous electrodes were placed on the abdominal skin surface (a reference electrode: at the xiphoid process, a grounding electrode: the lower edge of the left rib arch, electrode 3: at the midpoint of the xiphoid and the umbilicus, electrode 4: 4–6 cm on the right to the horizontal right of electrode 3, electrode 2: 5 cm to the upper-left of electrode 3, and electrode 1: 5 cm to the upper-left of electrode 2) (29, 30). The four-channel EGG signals were recorded, and the validated spectrum analysis method was used to obtain the following parameters: 1) percentage of normal slow waves [2.0–4.0 cycles/min (cpm)], representing the regularity of gastric slow waves; and 2) dominant power (DP) and dominant frequent (DF), representing the amplitude and frequency of gastric slow waves, respectively (31, 32). All values presented in this manuscript represented the means across the 4 channels.

Assessment of Autonomic Functions

The electrocardiogram (ECG) was performed at baseline and at the end of the treatment by a special amplifier (ECG-201, Ningbo Maida Medical Device, Ningbo, China). It was recorded simultaneously with the EGG via three surface electrodes placed as follows: one active electrode on the right manubrium of the sternum, the other active electrode on the fifth interspace in the left medio-clavicular line and the ground electrode on the right chest (33, 34). A heart rate variability (HRV) signal was derived from the ECG using software developed and validated in our laboratory by identifying R peaks and calculating R-R intervals. The HRV signal was subjected to power spectrum analysis, and the power in different bands was calculated by our previous validated method (33–35): Low frequency (LF, 0.05–0.15 Hz) is known to reflect mainly sympathetic activity, while high frequency (HF, 0.15–0.5 Hz) only reflects vagal activity; the sympathovagal balance was defined by the ratio LF/HF.

Nutrient Satiety Test

A nutrient satiety test was combined with the EGG (gastric function) and the ECG (autonomic function) tests in the following sequence: 1) a 30-min recordings of the EGG and ECG after an overnight fast, 2) the subject was asked to drink [100 g milk powder, 50 g chocolate powder (Cola Coa, Idilia Foods), and 1,120 mL water (0.6 Cal/mL, fat: 19%, protein: 18%, carbohydrate: 63%)] at a speed of 60 mL/min until reaching the maximum tolerable volume (MTV), and 3) another 30-min EGG and ECG recordings after the drink. Immediately after the drink, symptoms of fullness, nausea, and pain were assessed using the visual analog scale (0–100 in steps of 5 with 100 for most severe symptom) at time points 0, 10, 20, and 30 min after the drink (24, 29).

Safety

Patients were also instructed to complete a patient diary booklet each day to describe any side effects corresponding with treatment. The investigators checked all data to ensure the compliance. Participants who had side effects would be withdrawn from the study and referred for appropriate treatment immediately.

Statistical Analysis

The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to assess the distribution of parameters. Quantitative variables were presented as means ± standard error (SE) or median and range. χ2 analysis was performed to study the categorical variables. The paired Student’s t test and Wilcoxon test were applied to evaluate the differences between taVNS and sham-ES session or before and after 2-wk treatment. Independent sample t test or Mann–Whitney U test was used to analyze the differences between two groups. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare the difference among different groups or different recording channels. Post hoc analysis was performed using Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons when significant interactions were found. Correlation analysis was performed to assess the correlation between two different parameters. To assess the risk factors for predicting the improvement of dyspeptic symptoms, the logistic regression analysis was performed using the forward stepwise method. All variables, which showed significance (P < 0.05) in the univariate analysis, were considered as potential candidates for the multivariate analysis. Data were analyzed by statistical software SPSS 18.0. Statistical significance was assigned for P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Effects and Autonomic Mechanisms of Acute taVNS

Characteristics of patients.

A total of 36 eligible patients [female: 21 (58.3%); mean age: 45.9 yr; body mass index (BMI): 20.7 kg/m2] were enrolled in the acute study. The mean duration of disease was 18.0 (10.0, 48.0) months.

Effects of acute taVNS on gastric accommodation.

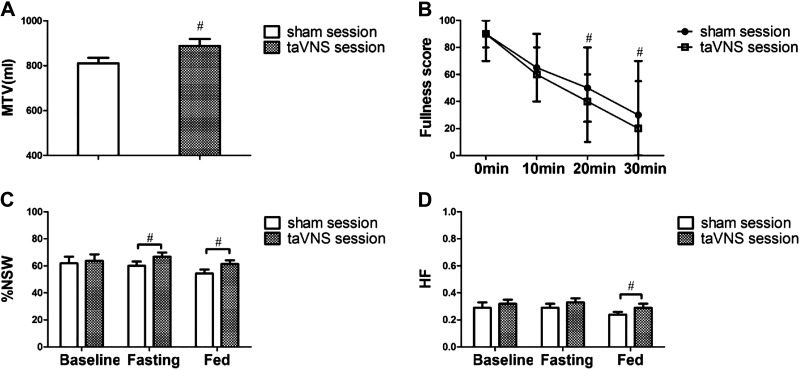

Acute taVNS enhanced gastric accommodation. Compared with sham-electrical stimulation (sham-ES), taVNS increased the maximum tolerable volume (MTV) of nutrient drink (874.2 ± 30.6 mL vs. 810.6 ± 24.8 mL, P = 0.008, Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

Effects and autonomic mechanisms of acute taVNS (n = 36). A: gastric accommodation after the maximum intake of nutrient drink. B: fullness score after the maximum intake of nutrient drink. C: percentage of normal gastric slow waves (%NSW) in average four channels of EGG at baseline, fasting (during taVNS and sham-ES), and fed (after the nutrient drink) states during the sham-ES and taVNS session. D: effects of taVNS on vagal efferent nerve activity. #P < 0.05 vs. sham session. EGG, electrogastrogram; taVNS, transcutaneous auricular vagal nerve stimulation.

Effects of acute taVNS on postprandial dyspeptic symptoms.

Acute taVNS reduced the postdrink fullness. Although the patients had a significantly higher intake of the liquid nutrient drink in the taVNS session, the fullness score at 20 min and 30 min after the drink in the taVNS session was lower than that in the sham-ES session [20 min: 40 (10, 60) vs. 50 (25, 80), P = 0.036; 30 min: 20 (0, 55) vs. 30 (0, 70), P = 0.046, Fig. 3B]. Overall, 10 patients in the sham-ES session had postprandial nausea compared with five patients in the taVNS session. Similarly, one patient in the sham-ES session had postprandial pain compared with none in the taVNS session. There was no difference between the taVNS and sham-ES session for the proportion of patients in nausea [5 (13.9%) vs. 10 (27.8%); P = 0.251] or pain [0 (0.0%) vs. 1 (2.8%); P = 0.4].

Effects of acute taVNS on gastric slow waves.

Acute taVNS improved the mean percentage of normal slow waves in both fasting (66.8% ± 3.1% vs. 60.0% ± 3.2%, P = 0.010) and fed states (61.3% ± 2.7% vs. 54.4 ± 2.9%, P = 0.007) compared with sham-ES (see Fig. 3C). It also increased the dominant power of EGG in the fed state (41.2 ± 0.7 dB with taVNS vs. 39.9 ± 0.7 dB with sham-ES, P = 0.031).

Acute taVNS mechanisms involving autonomic functions.

Acute taVNS, rather than sham-ES, increased the vagal activity (HF) and decreased the sympathetic activity (LF) during the 30-min postprandial period. Compared with the sham-ES session, the HF was significantly increased (0.29 ± 0.03 vs. 0.24 ± 0.02, P = 0.026, Fig. 3D) and the LF was significantly reduced (0.71 ± 0.03 vs. 0.76 ± 0.02, P = 0.026) after acute taVNS in the 30-min postprandial period.

Effects and Autonomic Mechanisms of Chronic taVNS

Characteristics of patients.

A total of 40 patients were consecutively screened for the chronic taVNS study. After exclusion of patients who did not meet the inclusion criteria (n = 2) and those who declined to participate (n = 2), 36 patients were enrolled and randomized into the 2-wk taVNS (n = 18) or 2-wk sham-ES (n = 18) group. The demographic and disease characteristics were matched including age, gender, body mass index, disease duration, and subtype between the two groups (Table 1). Thirty-nine age- and sex-matched healthy controls were also included in the study for a baseline recording session with the following information: 23 females and 16 males; mean age: 43.8 yr; and BMI: 23.1 kg/m2.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients treated with taVNS and sham-ES

| Sham-ES (n = 18) | taVNS (n = 18) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 43.9 ± 3.4 | 44.5 ± 3.7 | 0.916 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 22.3 ± 0.6 | 21.6 ± 0.7 | 0.844 |

| Sex, female % | 14 (77.8) | 11 (61.1) | 0.347 |

| Duration, mo | 15.0 (10.0, 48.0) | 12.0 (10.0, 48.0) | 0.729 |

| FD subtype (n, %) | |||

| PDS | 12 (66.7) | 11 (61.1) | 0.768 |

| EPS | 1 (5.6) | 0 (0) | |

| PDS-EPS Overlap | 5 (27.8) | 7 (38.9) |

n, Number of patients. BMI, body mass index; EPS, epigastric pain syndrome; FD, functional dyspepsia; PDS, postprandial distress syndrome.

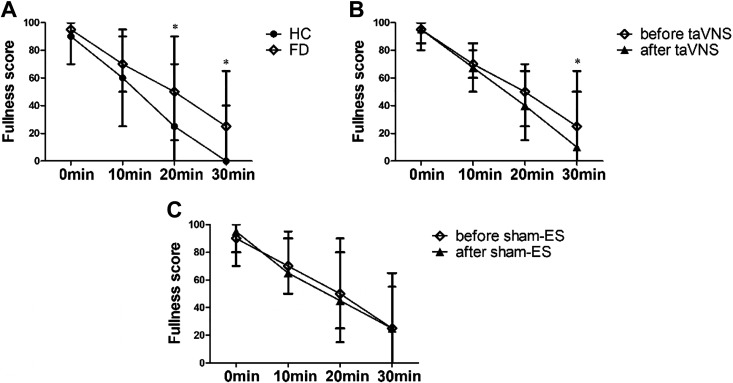

Effects of FD and chronic taVNS on gastric accommodation.

The patients showed a decreased gastric accommodation compared with the healthy controls and 2-wk taVNS but not sham-ES improved gastric accommodation. Compared with the HC, the MTV was substantially lower in the patients with FD (783.0 ± 24.1 mL vs. 950.8 ± 30.1 mL, P < 0.001, Fig. 4A). The 2-wk taVNS treatment increased the MTV significantly (901.2 ± 39.6 mL vs. 797.1 ± 40.3 mL, P < 0.001, Fig. 4B). This increase was, however, not noted in the sham-ES group (791.2 ± 47.4 mL vs. 771.9 ± 46.1 mL, P = 0.7, Fig. 4B). After the 2-wk treatment, the MTV of the taVNS group was higher than the sham-ES group (901.2 ± 39.6 mL vs. 791.2 ± 47.4 mL, P < 0.001) and comparable to the HC (901.2 ± 39.6 mL vs. 950.8 ± 30.1 mL, P = 0.8), whereas the MTV of the sham-ES group was still lower than the HC (791.2 ± 47.4 mL vs. 950.8 ± 30.1 mL, P < 0.001).

Figure 4.

Effects of chronic taVNS on gastric accommodation. A: the maximum tolerance volume (MTV, a surrogate of gastric accommodation) between HC (n = 39) and FD groups (n = 36). B: before and after the 2-wk treatment of sham-ES (n = 18) and taVNS (n = 18). taVNS not sham-ES group improved MTV significantly. *P < 0.001 vs. HC (A) or *P < 0.001 vs. before (B). FD, functional dyspepsia; HC, healthy control; MTV, maximum tolerance volume; taVNS, transcutaneous auricular vagal nerve stimulation.

Effects of FD and chronic taVNS on postprandial dyspeptic symptoms.

The patients with FD showed an increased fullness score 20–30 min after the maximum drink in comparison with the HC, and 2-wk taVNS but not sham-ES reduced the fullness score from 20 to 30 min after the drink. As shown in Fig. 5A, the fullness score in the patients with FD was higher than that in the HC after the drink at 10 min [70 (40, 95) vs. 60.0 (25, 90), P = 0.052], 20 min [50 (15, 90) vs. 25 (0, 70), P < 0.001], and 30 min [25 (0, 65) vs. 0 (0, 40), P < 0.001]. There was no difference between patients with FD and HC for the proportion of patients in nausea [8 (22.2%) vs. 7 (17.9%), P = 0.514] and pain [2 (5.6%) vs. 1 (2.6%), P = 0.813]. After the 2-wk treatment, the fullness score was significantly reduced at 30 min after the drink [10 (0, 50) vs. 25 (0, 65), P = 0.033] in the taVNS group (Fig. 5B) but not in the sham-ES group [25 (0, 65) vs. 25 (0, 55), P > 0.05, Fig. 5C]. Moreover, the proportion of nausea and pain after the maximum intake of nutrient drink showed no difference compared with the baseline in two groups.

Figure 5.

Effects of chronic taVNS on postprandial fullness score. A: comparison of fullness score between FD (n = 36) and HC (n = 39). B: effects of taVNS on 30-min postprandial fullness score (n = 18). C: effects of sham-ES on 30-min postprandial fullness score (n = 18). The 2-wk taVNS but not sham-ES reduced the fullness score at 30 min after the drink. *P < 0.05 vs. HC (A) or *P < 0.05 vs. before (B and C). FD, functional dyspepsia; HC, healthy control; taVNS, transcutaneous auricular vagal nerve stimulation.

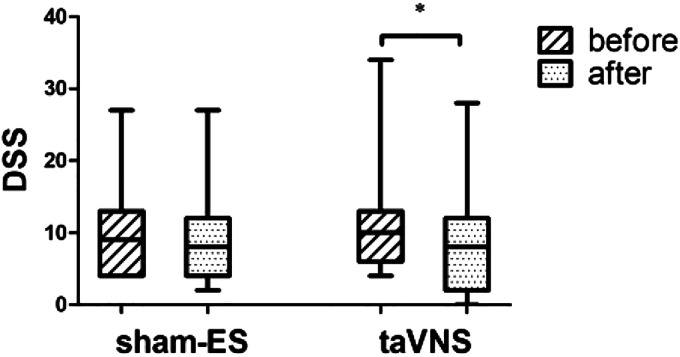

Effects of chronic taVNS on dyspeptic symptom scale.

As shown in Fig. 6, taVNS was effective in reducing the dyspeptic symptom assessed by questionnaire compared with the baseline [8.0 (0.0, 28.0) vs. 10.0 (4.0, 34.0), P = 0.010, n = 18]. The result was primarily attributed to the amelioration in bloating [2.0 (0.0, 5.0) vs. 5.0 (0.0, 5.0), P = 0.003, n = 18] and pain [2.0 (0.0, 2.0) vs. 2.0 (2.0, 4.0), P = 0.046, n = 6]. However, no significant differences were noted with sham-ES group in comparison with the baseline [8.5 (2.0, 27.0) vs. 9.5 (4.0, 27.0), P > 0.05, n = 18].

Figure 6.

Effects of chronic taVNS (n = 18) and sham-ES (n = 18) on dyspeptic symptom score taVNS not sham-ES group improved dyspeptic symptom significantly. *P < 0.05 vs. before. taVNS, transcutaneous auricular vagal nerve stimulation.

Effects of FD and chronic taVNS on anxiety and depression.

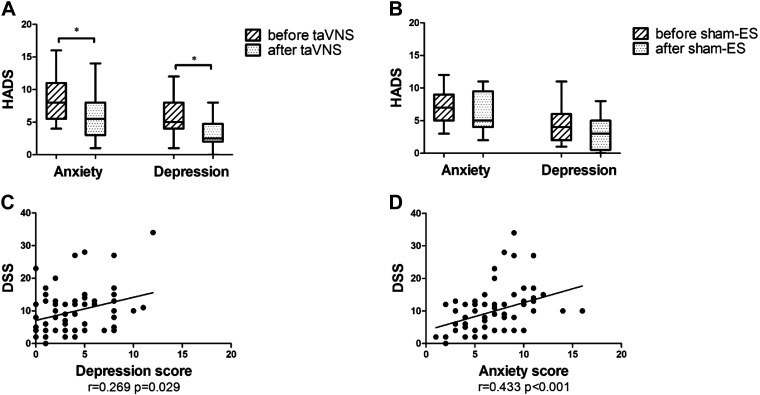

Compared with the HC, anxiety and depression scores were substantially increased in the FD [anxiety: 7.0 (3.0, 16.0) vs. 2.0 (0.0, 9.0), P < 0.001; depression: 4.0 (1.0, 12.0) vs. 1.0 (0.0, 12.0), P < 0.001]. The 2-wk taVNS treatment significantly reduced both anxiety [5.5 (1.0, 14.0) vs. 8.0 (4.0, 16.0), P = 0.002, Fig. 7A] and depression scores [2.5 (0.0, 8.0) vs. 5.0 (1.0, 12.0), P < 0.001, Fig. 7A]. However, no improvement was noted with sham-ES [anxiety: 5.0 (2.0, 11.0) vs. 7.0 (3.0, 12.0), P > 0.05; depression: 3.0 (0.0, 8.0) vs. 4.0 (1.0, 11.0), P > 0.05, Fig. 7B]. The depression and anxiety scores were weakly but positively correlated with DSS (r = 0.269, P < 0.05, n = 36, Fig. 7C; r = 0.433, P < 0.001, n = 36, Fig. 7D).

Figure 7.

Effects of chronic taVNS on anxiety and depression. A: effects of taVNS on anxiety and depression score (n = 18). B: effects of sham-ES on anxiety and depression score (n = 18). C: correlation of depression with DSS (n = 36). D: correlation of anxiety with DSS (n = 36). After 2-wk taVNS treatment, both anxiety and depression score were decreased than before. The depression and anxiety scores were weakly but positively correlated with DSS. *P < 0.05 vs. before (A and B). DSS, dyspeptic symptom scale; HADS, hospital anxiety and depression scale; taVNS, transcutaneous auricular vagal nerve stimulation.

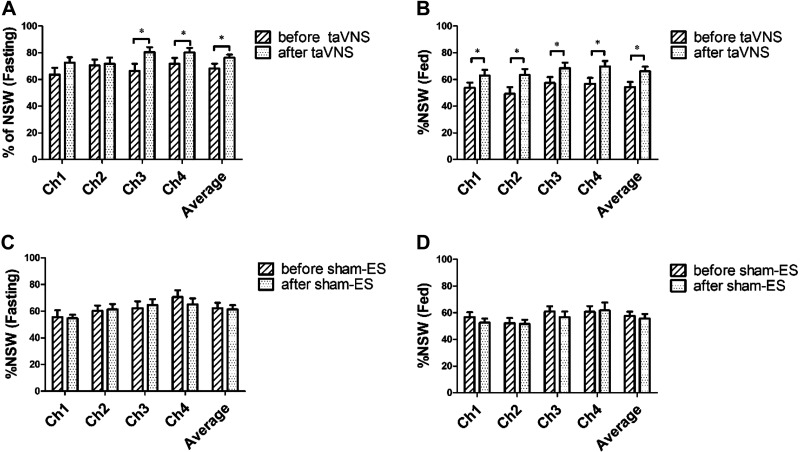

Effects of FD and chronic taVNS on normal gastric slow waves.

The percentage of normal gastric slow waves (%NSW) was reduced significantly in the FD in comparison with the HC, and 2-wk taVNS but not sham-ES increased the %NSW in both fasting and fed states. A significant difference was found between the patients with FD and the HC in the %NSW in both fasting (average of four channels: 61.9% ± 2.6% vs. 81.7% ± 1.7%, P < 0.001) and fed state (55.9% ± 2.3% vs. 72.5% ± 2.1%, P < 0.001). The 2-wk taVNS treatment increased the %NSW in both fasting and fed states (P < 0.05, Fig. 8A–B); however, the sham-ES treatment did not show any significant effect on gastric slow waves (P > 0.05, Fig. 8C–D). At the end of the 2-wk treatment, taVNS, in comparison with sham-ES, increased the %NSW in both fasting (average of four channels: 76.3% ± 2.4% vs. 61.5% ± 3.1%, P < 0.001) and fed state (average of four channels: 66.1% ± 3.6% vs. 55.6% ± 3.5%, P < 0.05). The %NSW in fasting state was weakly but positively correlated with MTV (r = 0.231, P = 0.048, n = 36) and negatively correlated with fullness score in 30 min fed state (r = −0.253, P = 0.035, n = 36).

Figure 8.

Effects of chronic taVNS on %NSW. A: effects of taVNS on %NSW in fasting state (n = 18). B: effects of taVNS on %NSW in fed state (n = 18). C: effects of sham-ES on %NSW in fasting state (n = 18). D: effects of sham-ES on %NSW in fed state (n = 18). The 2-wk taVNS group but not sham-ES group increased the %NSW in both fasting and fed state. *P < 0.05 vs. before. NSW, normal gastric slow waves; taVNS, transcutaneous auricular vagal nerve stimulation.

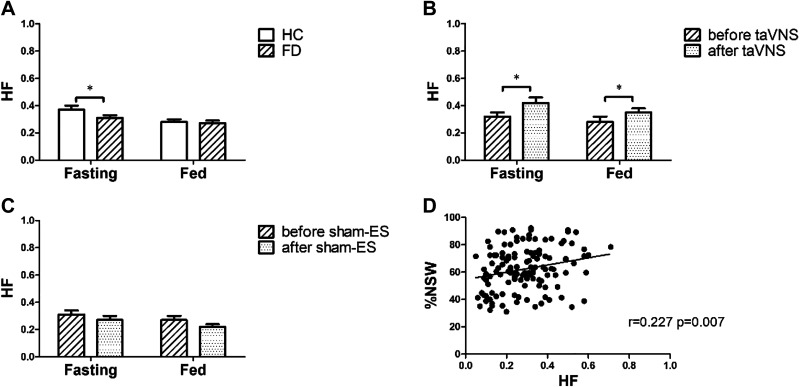

Chronic taVNS mechanisms involving autonomic functions.

Vagal activity (HF) was lower in the patients with FD in comparison with the HC in fasting state, and the 2-wk taVNS but not the sham-ES increased HF in both fasting and postprandial states. As shown in Fig. 9A, HF in the patients with FD was lower than that in the HC in fasting state (0.31 ± 0.02 vs. 0.37 ± 0.03, P = 0.047). After the 2-wk taVNS treatment, HF was increased in both fasting (0.42 ± 0.04 vs. 0.32 ± 0.03, P = 0.015) and postprandial state (0.35 ± 0.03 vs. 0.28 ± 0.04, P = 0.048) (Fig. 9B); these increases were not noted in the sham-ES group (Fig. 9C). HF was weakly but positively correlated with the %NSW (r = 0.227, P = 0.007, n = 36, Fig. 9D).

Figure 9.

Effects of chronic taVNS mechanisms involving autonomic functions. A: comparison of autonomic function between FD (n = 36) and HC (n = 39). B: effects of taVNS on autonomic function (n = 18). C: effects of sham-ES on autonomic function (n = 18). D: correlation of vagal nerve activity (HF) with %NSW (n = 36). The 2-wk taVNS group but not sham-ES group increased HF in both fasting and fed state. HF was weakly but positively correlated with the %NSW. *P < 0.05 vs. HC (A) or *P < 0.05 vs. before (B and C). HF, high frequency; NSW, normal gastric slow waves; taVNS, transcutaneous auricular vagal nerve stimulation.

Predictor for the improvement of dyspeptic symptom.

To assess the risk factors for the improvement of dyspeptic symptom (dyspeptic symptom scale reduced than before), we performed a multivariate logistic regression analysis. Patients with the improvement of dyspeptic symptom (n = 20) were assigned to taVNS (n = 13) and sham-ES groups (n = 7). Candidates for the multivariate analysis derived from the univariate analysis included three variables that showed a significant change: 1) anxiety score, 2) the LF/HF in fed state, and 3) the %NSW in fed state (Table 2). It was found that the anxiety score and %NSW in fed state were independent risk factors in predicting the improvement of dyspeptic symptom (Table 3).

Table 2.

Comparison between two groups with or without improvement of dyspeptic symptom after 2-wk treatment

| No Improvement (n = 16) | Improvement(n = 20) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | |||

| Age, yr | 43.2 ± 3.7 | 44.4 ± 3.8 | 0.831 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 21.3 ± 0.5 | 22.2 ± 0.7 | 0.748 |

| Sex, female % | 12 (75.0) | 13 (65.0) | 0.495 |

| Duration, mo | 18.0 (10.0, 48.0) | 12.0 (10.0, 48.0) | 0.330 |

| FD subtype (PDS/EPS/Overlap) | 10/1/5 | 13/0/7 | 0.479 |

| Treatment (taVNS %) | 5 (31.3) | 13 (65.0) | 0.092 |

| Autonomic function | |||

| LF/HF (fasting) | 3.73 ± 0.69 | 2.51 ± 0.37 | 0.105 |

| LF/HF (fed) | 5.27 ± 0.86 | 3.24 ± 0.47 | 0.033 |

| HF (fasting) | 0.28 ± 0.04 | 0.35 ± 0.04 | 0.231 |

| HF (fed) | 0.21 ± 0.03 | 0.29 ± 0.03 | 0.094 |

| Gastric pace-making activity | |||

| %NSW (fasting) | 67.1 ± 4.6 | 70.3 ± 2.5 | 0.513 |

| %NSW (fed) | 51.6 ± 3.7 | 64.3 ± 3.3 | 0.018 |

| Psychological state | |||

| Anxiety score | 8.0 (2.0, 14.0) | 5.0 (1.0, 11.0) | 0.028 |

| Depression score | 3.0 (0.0, 8.0) | 2.0 (0.0, 8.0) | 0.096 |

BMI, body mass index; HF, high frequency; LF/HF, low frequency/high frequency; %NSW, percentage of normal gastric slow waves.

Table 3.

Multivariate logistic regression on the improvement of dyspeptic symptom

| Variable | OR | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Anxiety score | 0.669 | 0.020 |

| LF/HF | 0.749 | 0.134 |

| %NSW | 1.078 | 0.040 |

LF/HF, low frequency/high frequency; %NSW, percentage of normal gastric slow waves.

Safety and side effects.

We found that only one patient reported mild tinnitus and insomnia with the taVNS treatment. However, the patient completed the 2-wk treatment and recovered fully from the adverse events after stopping the treatment. No other severe side effects, such as dizziness, tachycardia, red rashes, or swelling, were reported in any of the patients.

DISCUSSION

In the current study, we found that 1) patients with FD showed reduced gastric accommodation, impaired gastric slow waves and sympathovagal dysfunctions in comparison with health controls; 2) acute taVNS improved gastric accommodation, reduced postprandial fullness scores, and increased the percentage of normal gastric slow waves possibly by enhancing vagal activity in patients with FD; 3) the 2-wk taVNS treatment reduced the scores of dyspeptic symptoms, anxiety, and depression; in addition, the chronic taVNS also increased gastric accommodation and the percentage of normal gastric slow waves, but decreased postprandial fullness scores. These ameliorating effects were accompanied with the enhancement of vagal activity, suggesting an autonomic mechanism; and 4) chronic application of taVNS was noninvasive and safe.

The method of taVNS was needleless and well accepted by patients, which greatly facilitated the successful completion of the study. The device consisted of a watch-sized microstimulator and clip-shape electrodes. This self-administrative method provided direct evidence toward the feasibility of a widespread application of taVNS, substantially reduced treatment expenses, and greatly increased patient compliance. To make the study more feasible and practical, we chose noninvasive methods for the pathophysiological measurements: the use of the satiety nutrient drink as a surrogate of gastric accommodation and the use of noninvasive EGG for the assessment of gastric pacing-making activity. With these practical methods, all patients followed the protocol and completed the entire study.

Previous studies have investigated the effects of electrical stimulation of the auricular concha via needles (auricular electroacupuncture, AEA) and auricular acupressure on GI motility in animals and humans. Li et al. (36) reported a positive clinical outcome with auricular acupressure using magnetic pellets in managing constipation symptoms and disease-specific health-related quality of life among elderly residential care home patients. Feng et al. (37) found that auricular acupressure significantly decreased nausea and emesis in postoperative patients. Go et al. (38) demonstrated that auricular acupressure was effective in addressing loose stools, diarrhea, abdominal pain, abdominal discomfort, stress, and HRV in patients with IBS; however, it was a nonrandomized controlled study that made the results undermined. Li et al. (39) reported that AEA was effective in accelerating GI transit in rats and the effect was mediated via the vagal nerve, whereas further studies with sham acupuncture stimulation were needed to provide more conclusive results. Sukasem et al. (40) found that taVNS had significant effects on the characteristics of gastric slow waves in normal pigs; the shortcoming of the study was that gastric motility was observed under anesthesia instead of under conscious conditions.

To the best of our knowledge, this was the first study to investigate the ameliorating effects of taVNS on dyspeptic symptoms, and pathophysiological and autonomic mechanisms in patients with FD. Symptomatically, acute taVNS reduced the fullness score at 20 min and 30 min after the maximum drink and this effect could be attributed to acceleration in gastric emptying with taVNS. Although gastric emptying was not performed, previous animal studies reported acceleration of gastric emptying with auricular electrical stimulation of the same parameters in rats (20, 39). Chronic taVNS improved overall dyspeptic symptoms and substantially reduced the bloating and pain scores. These ameliorating effects were believed to be attributed to improvement in gastric accommodation and gastric motility. Weak but significant correlations were noted between the improvement in symptoms and certain gastric functions. The weak correlations were attributed to the multiple pathophysiologies involved in FD. Interestingly, the chronic taVNS treatment was also noted to substantially reduce the anxiety and depression scores. These effects were believed to be attributed to the central effect of taVNS as previously reported in patients with depressive disorders (41) and other neurological disorders (42).

Physiologically, we used the EGG to measure gastric slow waves as it was correlated with gastric contraction and gastric emptying, and noninvasive, and thus feasible for this clinical study (32). In this study, the percentage of normal gastric slow waves was found to be lower in FD compared with HC, which was consistent with previous findings (43–45). Both acute and chronic taVNS increased the percentage of normal gastric slow waves assessed by the EGG. Previously, one of our animal studies showed an ameliorating effect of AEA on rectal distention-induced gastric dysrhythmia mediated via the vagal mechanism, which was in accordance with the present findings (19). In particular, transcutaneous electrical acustimulation (TEA) at acupoints ST36 and PC6 showed similar results with taVNS (10, 22). Second, the satiety nutrient drinking test (46) was used to assess gastric accommodation, which reflects relaxation of the proximal stomach. Impaired gastric accommodation has been associated with bloating and early satiety (47). Although gastric barostat remains the gold standard, it is an invasive procedure with poor patient compliance, especially for repetitive sessions. Using the maximum tolerable volume in the satiety drinking test as a surrogate of gastric accommodation, we found a reduced gastric accommodation in patients with FD and improvement in gastric accommodation with both acute and chronic taVNS, which were in agreement with previous studies with TEA at acupoints ST36 and PC6 (10, 23). Ji et al. (10) reported that TEA at ST36 and PC6 significantly improved dyspeptic symptoms, gastric accommodation, and gastric slow waves in patients with FD by balancing sympathovagal activities. The similarities in the improvement in gastric accommodation and gastric slow waves between transcutaneous electrical stimulation at the auricular concha and transcutaneous electrical stimulation at the acupoints ST36 and PC6 are interesting and suggestive of similar autonomic mechanisms.

Spectral analysis of HRV is a noninvasive and simple method for the quantitative evaluation of cardiac autonomic functions (48–50). In this study, we found that the autonomic dysfunction was featured by a decline of vagal activity in patients with FD compared with healthy controls. Both acute and chronic taVNS significantly increased the vagal efferent activity in patients with FD. The result is explicable: It is well known that the parasympathetic nerve stimulates, whereas the sympathetic nerve inhibits GI motility. We speculated that taVNS promoted GI tract motility via the autonomic mechanisms, which had been widely reported in other TEA/acupuncture studies (25, 33, 34). In this study, the vagal activity was found to be weakly but significantly correlated with gastric pace-making activity (slow wave). The weak correlations were attributed to the multiple pathophysiologies involved in FD, such as visceral hypersensitivity, delayed gastric emptying, gastric dysrhythmia. The enhancement of vagal activity with taVNS might improve some of these factors but not all pathophysiologies. In addition, the weak correlation could also be more likely attributed to the different vagal pathways to the heart and the stomach, respectively. The cardioinhibitory fibers originate in the external formation of the nucleus ambiguous, whereas neurons in the dorsal motor nucleus innervate the stomach (51). Although there are some dorsal motor nucleus neurons that project to the heart, they most likely do not affect heart rate (51).

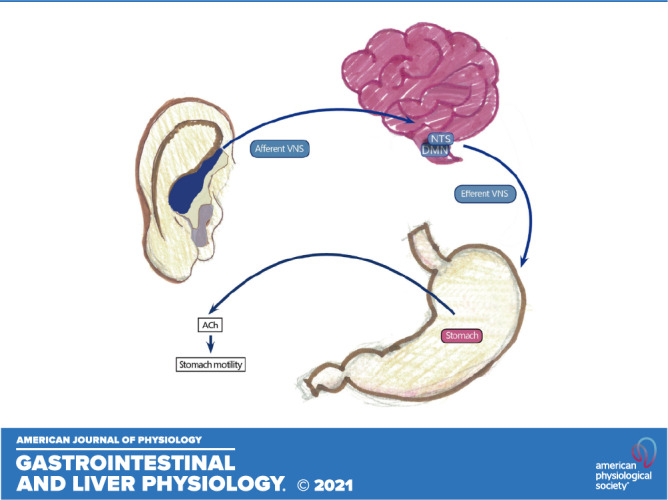

Mechanistically, the vagus nerve has a branch of afferent projections at the auricular concha that is the only afferent vagus nerve distribution place on the surface of the human body (21). It has been reported that auricular vagus afferent fibers project to nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS) from a primary relay in the spinal trigeminal nucleus or paratrigeminal nucleus, then connecting to brain structures such as dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus, hypothalamus, amygdala, and frontal brain cortex involving autonomic control, pain, and emotional response (21, 52, 53). The activation of the NTS with taVNS has recently been documented in healthy controls (54). Moreover, the other nerves of the auricle also project to the NTS (55). Therefore, it is important to exactly locate the position of the stimulating electrodes. Since the gastric vagal efferent shares the same central origin with the cardiac vagal efferent, the increased vagal efferent outflow assessed by the spectral analysis of HRV is indicative of enhanced gastric vagal efferent activity. We speculated the increased gastric vagal efferent activity resulted in enhanced gastric accommodation and improved gastric pace-making activity (slow wave) and thus leading to improvement in dyspeptic symptoms. However, further studies would be needed to investigate the effects and more systematic mechanisms, and to promote the application of taVNS for treating GI motility disease.

Interestingly, the anxiety score and %NSW were found to be independent risk factors for predicting the improvement of dyspeptic symptom in our study. If the patient had a higher value of anxiety score and a lower value of %NSW, he or she would be more difficult to gain symptom improvement.

There were limitations in this pilot clinical study. First, the symptoms of patients enrolled in this study were not severe (median DSS 10.0) that might not be representative of patients with FD seen in tertiary medical centers. The lack of patients with severe dyspeptic symptoms could be attributed to two factors: 1) The hospital where the study was performed was not a tertiary medical center, and therefore, not many patients with severe symptoms would come to the hospital; and 2) the exclusion criterion of “taking medications affecting GI motility within one week before the recruitment or could not quit these medications.” Second, due to a lack of agreement in the literature on the duration of electrical stimulation, the treatment duration in this study was chosen to be 2 wk based on our previous study. Whether the effect was sustainable after the 2-wk treatment was unclear and still warranted follow-up period evaluation. Third, the results of the study would be more reliable or less biased if the trial was performed in multiple centers with a larger population. Last, we chose the sham stimulation point on the arms that was also used in our previous studies because we speculated that electrical stimulation at a sham point in the ear might actually activate vagal afferent due to dissemination of electrical current.

In conclusion, transcutaneous auricular vagal nerve stimulation is effective in treating major dyspeptic symptoms in patients with nonsevere functional dyspepsia; the ameliorating effects are believed to be attributed to the improvement in gastric accommodation and motility mediated via the vagal efferent mechanism.

GRANTS

This study was supported by Chinese Medicine Technology Project of Zhejiang Province (Grant No. 2019ZB119).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Y.Z., F.X., P.R., and J.D.Z.C. conceived and designed research; Y.Z., F.X., D.L., J.C., M.L., and W.W. performed experiments; Y.G. and C.S. analyzed data; Y.Z. interpreted results of experiments; Y.G. prepared figures; Y.Z. drafted manuscript; L.L. and J.D.Z.C. edited and revised manuscript; Y.Z., F.X., D.L., P.R., J.C., M.L., Y.G., C.S., W.W., L.L., and J.D.Z.C. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Talley NJ, Ford AC. Functional dyspepsia. N Engl J Med 373: 1853–1863, 2015. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1501505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marx M, Maye H, Abdelrahman K, Hessler R, Moschouri E, Aslan N, Godat S, Nichita C, Wiesel P, Perez L, Schoepfer AM. Functional gastrointestinal disorders: update on the Rome IV criteria. Rev Med Suisse 14: 1512–1516, 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Futagami S, Yamawaki H, Agawa S, Higuchi K, Ikeda G, Noda H, Kirita K, Akimoto T, Wakabayashi M, Sakasegawa N, Kodaka Y, Ueki N, Kawagoe T, Iwakiri K. New classification Rome IV functional dyspepsia and subtypes. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol 3: 70, 2018. doi: 10.21037/tgh.2018.09.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Futagami S, Shimpuku M, Yin Y, Shindo T, Kodaka Y, Nagoya H, Nakazawa S, Fujimoto M, Izumi N, Ohishi N, Kawagoe T, Horie A, Iwakiri K, Sakamoto C. Pathophysiology of functional dyspepsia. J Nippon Med Sch 78: 280–285, 2011. doi: 10.1272/jnms.78.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Camilleri M, Stanghellini V. Current management strategies and emerging treatments for functional dyspepsia. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 10: 187–194, 2013. [Erratum in Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 10: 320, 2013]. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Madisch A, Andresen V, Enck P, Labenz J, Frieling T, Schemann M. The diagnosis and treatment of functional dyspepsia. Dtsch Arztebl Int 115: 222–232, 2018. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2018.0222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Masuy I, Van Oudenhove L, Tack J. Review article: treatment options for functional dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 49: 1134–1172, 2019. doi: 10.1111/apt.15191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yin J, Chen JD. Gastrointestinal motility disorders and acupuncture. Auton Neurosci 157: 31–37, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2010.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen JDZ, Ni M, Yin J. Electroacupuncture treatments for gut motility disorders. Neurogastroenterol Motil 30: e13393, 2018. doi: 10.1111/nmo.13393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ji T, Li X, Lin L, Jiang L, Wang M, Zhou X, Zhang R, Chen J. An alternative to current therapies of functional dyspepsia: self-administrated transcutaneous electroacupuncture improves dyspeptic symptoms. Evid Based Complemen Alternat Med 2014: 832523, 2014. doi: 10.1155/2014/83252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee LA, Chen J, Yin J. Complementary and alternative medicine for gastroparesis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 44: 137–150, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2014.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang N, Huang Z, Xu F, Xu Y, Chen J, Yin J, Lin L, Chen JD. Transcutaneous neuromodulation at posterior tibial nerve and ST36 for chronic constipation. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2014: 1–7, 2014. doi: 10.1155/2014/560802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Badran BW, Yu AB, Adair D, Mappin G, DeVries WH, Jenkins DD, George MS, Bikson M. Laboratory administration of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation (taVNS): technique, targeting, and considerations. J Vis Exp 143: 10.3791/58984, 2019. doi: 10.3791/58984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kong J, Fang J, Park J, Li S, Rong P. Treating depression with transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation: state of the art and future perspectives. Front Psychiatry 9: 20, 2018. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rong P, Liu J, Wang L, Liu R, Fang J, Zhao J, Zhao Y, Wang H, Vangel M, Sun S, Ben H, Park J, Li S, Meng H, Zhu B, Kong J. Effect of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation on major depressive disorder: a nonrandomized controlled pilot study. J Affect Disord 195: 172–179, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.02.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rong P, Liu A, Zhang J, Wang Y, Yang A, Li L, Ben H, Li L, Liu R, He W, Liu H, Huang F, Li X, Wu P, Zhu B. An alternative therapy for drug-resistant epilepsy: transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation. Chin Med J (Engl) 127: 300–304, 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacobs HI, Riphagen JM, Razat CM, Wiese S, Sack AT. Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation boosts associative memory in older individuals. Neurobiol Aging 36: 1860–1867, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou J, Li S, Wang Y, Lei Y, Foreman RD, Yin J, Chen JD. Effects and mechanisms of auricular electroacupuncture on gastric hypersensitivity in a rodent model of functional dyspepsia. PLoS One 12: e0174568, 2017. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0174568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang Z, Yin J, Chen JD. Ameliorating effects of auricular electroacupuncture on rectal distention-induced gastric dysrhythmias in rats. PLoS One 10: e0114226, 2015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li H, Yin J, Zhang Z, Winston JH, Shi XZ, Chen JD. Auricular vagal nerve stimulation ameliorates burn-induced gastric dysmotility via sympathetic-COX-2 pathways in rats. Neurogastroenterol Motil 28: 36–42, 2016. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peuker ET, Filler TJ. The nerve supply of the human auricle. Clin Anat 15: 35–37, 2002. doi: 10.1002/ca.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu S, Peng S, Hou X, Ke M, Chen JD. Transcutaneous electroacupuncture improves dyspeptic symptoms and increases high frequency heart rate variability in patients with functional dyspepsia. Neurogastroenterol Motil 20: 1204–1211, 2008. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2008.01164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu F, Tan Y, Huang Z, Zhang N, Xu Y, Yin J. Ameliorating effect of transcutaneous electroacupuncture on impaired gastric accommodation in patients with postprandial distress syndrome-predominant functional dyspepsia: a pilot study. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2015: 168252, 2015. doi: 10.1155/2015/168252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ma G, Hu P, Zhang B, Xu F, Yin J, Yang X, Lin L, Chen JDZ. Transcutaneous electrical acustimulation synchronized with inspiration improves gastric accommodation impaired by cold stress in healthy subjects. Neurogastroenterol Motil 31: e13491, 2019. doi: 10.1111/nmo.13491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang B, Xu F, Hu P, Zhang M, Tong K, Ma G, Xu Y, Zhu L, Chen JDZ. Needleless transcutaneous electrical acustimulation: a pilot study evaluating improvement in post-operative recovery. Am J Gastroenterol 113: 1026–1035, 2018. doi: 10.1038/s41395-018-0156-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang B, Zhu K, Hu P, Xu F, Zhu L, Chen JDZ. Needleless transcutaneous neuromodulation accelerates postoperative recovery mediated via autonomic and immuno-cytokine mechanisms in patients with cholecystolithiasis. Neuromodulation 22: 546–554, 2019. doi: 10.1111/ner.12856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Revicki DA, Rentz AM, Dubois D, Kahrilas P, Stanghellini V, Talley NJ, Tack J. Gastroparesis Cardinal Symptom Index (GCSI): development and validation of a patient reported assessment of severity of gastroparesis symptoms. Qual Life Res 13: 833–844, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stern AF. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Occup Med (Lond) 64: 393–394, 2014. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqu024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang Z, Zhang N, Xu F, Yin J, Dai N, Chen JD. Ameliorating effect of transcutaneous electroacupuncture on impaired gastric accommodation induced by cold meal in healthy subjects. Gastroenterol Hepatol 31: 561–566, 2016. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li M, Xu F, Liu M, Li Y, Zheng J, Zhu Y, Lin L, Chen J. Effects and mechanisms of transcutaneous electrical acustimulation on postoperative recovery after elective cesarean section. Neuromodulation 23: 838–846, 2020. doi: 10.1111/ner.13178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen JD, Richards RD, McCallum RW. Identification of gastric contractions from the cutaneous electrogastrogram. Am J Gastroenterol 89: 79–85, 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yin J, Chen JD. Electrogastrography: methodology, validation and applications. Neurogastroenterol Motil 19: 5–17, 2013. doi: 10.5056/jnm.2013.19.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu Z, Lu D, Guo J, Liu Y, Shi Z, Xu F, Lin L, Chen JDZ. Elevation of lower esophageal sphincter pressure with acute transcutaneous electrical acustimulation synchronized with inspiration. Neuromodulation 22: 586–592, 2019. doi: 10.1111/ner.12967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu GJ, Xu F, Sun XM, Chen JDZ. Transcutaneous neuromodulation at ST36 (Zusanli) is more effective than transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation in treating constipation. J Clin Gastroenterol 54: 536–544, 2020. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sztajzel J. Heart rate variability: a noninvasive electrocardiographic method to measure the autonomic nervous system. Swiss Med Wkly 134: 514–522, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li MK, Lee TF, Suen KP. Complementary effects of auricular acupressure in relieving constipation symptoms and promoting disease-specific health-related quality of life: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Complement Ther Med 22: 266–277, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2014.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Feng C, Popovic J, Kline R, Kim J, Matos R, Lee S, Bosco J. Auricular acupressure in the prevention of postoperative nausea and emesis a randomized controlled trial. Bull Hosp Jt Dis 75: 114–118, 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Go GY, Park H. Effects of auricular acupressure on women with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterol Nurs 43: E24–E34, 2019. doi: 10.1097/SGA.0000000000000332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li H, Wang YP. Effect of auricular acupuncture on gastrointestinal motility and its relationship with vagal activity. Acupunct Med 31: 57–64, 2013. doi: 10.1136/acupmed-2012-010173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sukasem A, Cakmak YO, Khwaounjoo P, Gharibans A, Du P. The effects of low-and high-frequency non-invasive transcutaneous auricular vagal nerve stimulation (taVNS) on gastric slow waves evaluated using in vivo high-resolution mapping in porcine. Neurogastroenterol Motil 32: e13852, 2020. doi: 10.1111/nmo.13852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu C, Liu P, Fu H, Chen W, Cui S, Lu L, Tang C. Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation in treating major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 97: e13845, 2018. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000013845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Redgrave J, Day D, Leung H, Laud PJ, Ali A, Lindert R, Majid A. Safety and tolerability of transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation in humans: a systematic review. Brain Stimul 11: 1225–1238, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2018.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gharibans AA, Coleman TP, Mousa H, Kunkel DC. Spatial patterns from high-resolution electrogastrography correlate with severity of symptoms in patients with functional dyspepsia and gastroparesis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 17: 2668–2677, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lin X, Levanon D, Chen JD. Impaired postprandial gastric slow waves in patients with functional dyspepsia. Dig Dis Sci 43: 1678–1684, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sha W, Pasricha PJ, Chen JD. Rhythmic and spatial abnormalities of gastric slow waves in patients with functional dyspepsia. J Clin Gastroenterol 43: 123–129, 2009. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318157187a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mureşan A, Pop LL, Dumitraşcu DL. The drinking test: a current noninvasive technique to evaluate gastric accommodation and perception. Acta Gastroenterol Belg 77: 328–332, 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kindt S, Tack J. Impaired gastric accommodation and its role in dyspepsia. Gut 55: 1685–1691, 2006. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.085365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smarius L, van Eijsden M, Strieder TGA, Doreleijers TAH, Gemke R, Vrijkotte TGM, de Rooij SR. Effect of excessive infant crying on resting BP, HRV and cardiac autonomic control in childhood. PLoS One 13: e0197508, 2018. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0197508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vidigal GA, Tavares BS, Garner DM, Porto AA, Carlos de Abreu L, Ferreira C, Valenti VE. Slow breathing influences cardiac autonomic responses to postural maneuver: slow breathing and HRV. Complement Ther Clin Pract 23: 14–20, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2015.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yu Y, Wei R, Liu Z, Xu J, Xu C, Chen JDZ. Ameliorating effects of transcutaneous electrical acustimulation combined with deep breathing training on refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease mediated via the autonomic pathway. Neuromodulation 22: 751–757, 2019. doi: 10.1111/ner.13021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gourine AV, Machhada A, Trapp S, Spyer KM. Cardiac vagal preganglionic neurones: an update. Auton Neurosci 199: 24–28, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2016.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Henry TR. Therapeutic mechanisms of vagus nerve stimulation. Neurology 59: S3–S14, 2002. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.6_suppl_4.s3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nomura S, Mizuno N. Central distribution of primary afferent fibers in the Arnold's nerve (the auricular branch of the vagus nerve): a transganglionic HRP study in the cat. Brain Res 292: 199–205, 1984. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)90756-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sclocco R, Garcia RG, Kettner NW, Isenburg K, Fisher HP, Hubbard CS, Ay I, Polimeni JR, Goldstein J, Makris N, Toschi N, Barbieri R, Napadow V. The influence of respiration on brainstem and cardiovagal response to auricular vagus nerve stimulation: a multimodal ultrahigh-field (7T) fMRI study. Brain Stimul 12: 911–921, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2019.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Butt MF, Albusoda A, Farmer AD, Aziz Q. The anatomical basis for transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation. J Anat 236: 588–611, 2020. doi: 10.1111/joa.13122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]