Abstract

Purpose

The study objective is to investigate the relationship between workplace ostracism, workplace incivility, and knowledge hiding behavior (evasive hiding, playing dumb, rationalized hiding) while considering the mediating role of job anxiety.

Methods

The study collected data through structured questionnaires from 275 participants (ie, employees) working in the small to medium-sized enterprise of five big cities of Pakistan. The study adopted a structured equation modeling technique for data analysis.

Results

Significantly, the study results suggest a positive effect of workplace ostracism and workplace incivility on employees’ knowledge hiding behavior, and job anxiety significantly mediates the relationship between workplace ostracism, workplace incivility, and knowledge hiding behavior of employees.

Conclusion

The present study highlights the need to examine the personality disposition for understanding the relationship between the variables (eg, workplace ostracism, workplace incivility, knowledge hiding behavior). Employees’ inappropriate behavior had suppressed by initiating a campaign for a realistic job preview, setting an exceptional example. The study significantly contributes to the current literature on knowledge hiding behavior by presenting valuable insight into organizational and individual variables, subsequently influencing the knowledge hiding behavior of individuals. Indeed, this study is the first to investigate the predictive effect of the proposed variables.

Keywords: workplace ostracism, workplace incivility, job anxiety, knowledge hiding behavior, SMEs

Introduction

To thrive in an economy, knowledge offers a competitive advantage.1 Knowledge sharing can improve organizational performance and innovation abilities while lowering costs. By deploying software to share knowledge, implementing incentive systems, building a long-term employee relationship, and fostering an environment that encourages knowledge sharing among employees are a few ways that companies start behaviors that enhance knowledge sharing. Even with such efforts, employee sharing remains low. They purposely conceal this information from their colleagues.2 They have proven that the key to organizational success is the effective sharing of knowledge. Many scholars regard such a phenomenon as crucial in promoting innovation and improving performance in production companies. The studies suggested sharing knowledge. Han et al3 concluded that employees chose not to share their knowledge, hence the term “knowledge hiding.” An individual intentionally conceals or withholds requested information. Research has regarded secretive behavior as a negative factor that deters organizational performance, but studies examining its causes are often not comprehensive.4

Knowledge sharing receives more attention than knowledge concealment. They are conceptually different concepts. Sharing information does not happen accidentally in knowledge hiding; instead, sharing is withheld or concealed intentionally to withhold requested information.4 Since the motives for these acts are different, sharing information is simply absent. To foster knowledge transfer and sharing, organizations must understand the motivations behind employees’ behavior at work. Irum et al5 study was associated with mutual understanding and reciprocity, which explains the tendency for members at work to respond negatively if mistreated.6 Positive workplace relationships are crucial for employees to interact socially.1 Workplace ostracism (WO) and workplace incivility (WI) play an essential role in eradicating social exchange behaviors in workplace ostracism.7 Workplace ostracism is a factor that brings with its stressful behavior, emotional, physical, and mental exhaustion, and less productive behavior.8 Currently, a study is exploring the impact of workplace disrespect on work performance and employee contributions.6 The pervasive nature of workplace incivility and workplace ostracism may negatively impact an organization’s performance and employee engagement.2 Workplace ostracism can stop people from helping in the workplace and promote counterproductive work behavior (CWB). Zhao et al9 asserted that workplace incivility and workplace ostracism affect employees’ socialization. As a result, work stress may correlate with knowledge hiding as a predictor.

The motivation for hiding knowledge also pertains to the surrounding environment.3 For example, the way employees interrelate will affect behavior since they share a workplace.10 Thus, workplace incivility and workplace ostracism may be a situational factor that promotes evasive hiding between coworkers. Organizational behavior research explores the concept of workplace incivility and ostracism as an emerging phenomenon.11 However, this study intends to examine how knowledge is hidden within teams, despite many studies examining the causes, consequences, and nature of knowledge hiding. Thus, the study adopts the social exchange theory (SET) and negative reciprocity as theoretical foundations to analyze and clarify workplace incivility and ostracism’s prediction impact on the concealment of information and job anxiety with this construct. Since individual differences influence how one thinks and behaves, the information is relevant.12

According to research, workplace incivility and workplace ostracism lead to employees’ hiding knowledge, negatively affecting the organization’s performance.13 Workplace incivility and workplace ostracism affected the performance of organizations and the organizations’ stakeholders, resulting in researchers investigating and addressing this issue. They wished to discover the causes and origins of workplace incivility and workplace ostracism.14 People who work for Pakistani SMEs change their behavior based on workplace incivility and workplace ostracism. According to previous research, we should associate workplace incivility and workplace ostracism with job anxiety.15 However, it is unknown whether workplace incivility, workplace ostracism, job anxiety, or a tendency to hide information are connected. Researchers need to investigate the role of job anxiety, particularly as a mitigating factor. Many workers deal with workplace incivility and workplace ostracism, yet they keep their fears to themselves out of fear of discrimination.16 As a result, they are less productive, which adversely affects their motivation for work and loyalty to the organization. The damage they do to a company’s reputation creates a hostile work environment, resulting in poor performance. It is an attempt to help entrepreneurs of Pakistani SMEs as well as in the Asian context to reduce job anxiety and workplace ostracism/ workplace incivility that inhibit knowledge hiding by using this research.5 It reveals the impact of working away from home on a worker’s work life, personal relationships, and home life. Working away from home disrupts a worker’s work-life balance and can create confusion, stress, and distress for the worker.

Based on the background literature, studying the effects of workplace factors and job anxiety and interdisciplinary approaches to work is the purpose of this study. Therefore, a discussion is included about workplace ostracism, workplace incivility, job anxiety, and knowledge hiding behavior. The following RQ (research questions) were derived from the literature discussed above:

RQ1: To what extent can workplace ostracism affect the concealment of knowledge?

RQ2: How does workplace incivility determine knowledge hiding?

RQ3: Do job anxiety behaviors interrelate with workplace incivility, workplace ostracism, and knowledge concealment?

Literature Review

Knowledge Hiding Behavior

Besides increasing the overall performance of an organization and making it more innovative, employees exchange knowledge implicitly and explicitly with co-workers.17 The intentional hiding of knowledge is inherently selfish, but employees might be unwilling to impart it to others. Knowledge includes things like information about the job or information related to specific tasks.18 Knowing that sharing knowledge is not welcomed distinguishes between holding on to knowledge. This is detrimental to the flow of knowledge within an organization. As Ma et al19 pointed out, it differs from counterproductive behavior (CWB), since knowledge concealment, while malicious, of course, is not aimed at harming people or organizations, while CWB should do so. There are a few positive motives behind knowledge hiding. Rationalized hiding has the purpose of shielding another’s feelings or safeguarding confidential information (eg, refusing to share personal documents). A CWB can hurt the interests of both the organization and the stakeholder, whereas information hiding is dualistic and, therefore, cannot be viewed as equally harmful.20

It is essential to keep in mind that different methods are used by employees with concealing information, according to what question is being asked. In complex environments, employees may hide their knowledge evasively.14 A person who uses evasive hiding provides inaccurate information or promises that they will provide sufficient information later. Thus, although the individual is not in the Business of providing information, deception is involved. In contrast, an alternative strategy is conceptualized as “failing to pretend ignorance of relevant information”.15

A typical example is pretending not to know what the management is after. Last, rationalized hiding refers to “making an excuse for giving a reason or blaming another party.” Keeping confidential information secret and protecting coworkers’ feelings are important reasons for using confidentiality.21 The consequences of intentionally hiding information are detrimental for organizational performance, corporations, and development, even though individuals may think of them as positive. This is true even for the likelihood of concealing information, but the research has not considered this, despite efforts to ensure knowledge sharing through organizational practices.22

Workplace Ostracism

Workers become less engaged and disengaged once they are exposed to work ostracism and dissatisfied with their work when considered outsiders. When a person experiences workplace ostracism, unproductive work behavior ensues.23 Having this problem leads to less productive behavior, physical, mental, and emotional exhaustion psychological and physical harm resulting from workplace ostracism, which affects job anxiety and innovative behavior at work. An organization or firm’s efficiency decreases because of poorly motivated employees who cope with workplace ostracism.24,25

An increasing number of organizations have become interested in social exclusion, mistreatment, and workplace ostracism. Because it creates social pain, it has many negative consequences, both at the individual and organizational levels.26 With workplace ostracism, it is “the feeling that one is overlooked at work.” By threatening self-esteem, belonging, control, and a sense of meaning, a sense of purpose in one’s life is threatened. The first study investigating workplace ostracism concluded that it could be ostracized by any part of the workplace, including supervisors, co-workers, or clients within or outside the organization.27 Perceptions of workplace ostracism are subjective.8 When a coworker experiences workplace ostracism, they engage in hostile behavior toward colleagues. It can be subtle and overt, depending on the situation.28 As well as affecting an individual’s capacity to start and maintain healthy behaviors, these consequences result in decreased work motivation, civic engagement, and health problems.29,30 The organization’s efficiency has recently attracted more attention from researchers.21 The result was deviant behavior between coworkers, incompetence, and counterproductive behavior because of increased social interactions. Other organizations display similar behavior.31

Workplace Incivility

According to Liu et al,32 workplace incivility is characterized by disrespecting others to lead to a sense of disconnection, a break in interpersonal relations, as well as an underdeveloped empathy.33 Studies of workplace incivility have examined incidents involving individual workers, including checking email during meetings, sending text messages during meetings, and expressing disrespectful remarks.34 Two factors explain why scholars are paying more attention to these once-disregarded isolated incidents. First, it is irresponsible to ignore the costs related to workplace incivility.35 According to researchers, workplace incivility takes a toll on both individuals and organizations. According to previous research, workplace incivility negatively influences employees’ well-being, turnover intentions, and commitment to their jobs. Second, workplace incivility affects the entire world as well. Even though many investigations of workplace incivility have been conducted in American settings. Liu et al32 demonstrates workplace incivility is not uncommon in Asian workplaces. In Asian workplaces, workplace incivility has a similar negative impact on the organization and the individual, although little empirical research has examined outcomes of workplace incivility in the Asian workforce.36

Samma et al37 discussed workplace incivility and knowledge hiding based on social exchange and reciprocal norm theories. When individuals exchange socially, benefits motivate them to expect and participate in the discussion.38 Therefore, interactions exchanging goods and services require adherence to a reciprocity principle related to social rules governing how people respond to one another.39 In this way, laws will govern exchanges. Negative and positive reciprocity are two ways we view reciprocity.40 For example, when a manager treats another negatively, it is natural to return the kindness in kind; positive reciprocity produces favorable treatment.41,42 Therefore, when a party feels they have been treated favorably, they will reciprocate in the same manner.

Job Anxiety

As described in the APA Handbook of Occupational Health, job anxiety includes “a worrying, frightened, and restless state associated with perceived emotional or physical danger” occurring while resources are under threat.43 An employee’s desire to be hired may also contribute to job anxiety.44 The treatment one receives at work affects someone’s well-being.45 We relate an underlying sense of injustice induced by undermining to aggressive and depressive behavior.46 Job anxiety causes employees to feel less satisfied with their jobs, perceive less support from their employer, and leave more often. We associate job anxiety with poor work performance.47 Saquib et al48 found it a surrogate that encourages defensive behavior and reduces aligning its goals with employees. Low job anxiety can be predicted by observing how the workplace changes or becomes unsettling.49

The Conservation of Resources Theory (COR)

As a basis for making theoretical predictions, the COR model was employed in this study. Compared to a cooperative workplace environment, people working in an uncooperative work environment have a negative attitude toward their jobs and show little interest in their assigned work.50 The depletion of resources is also associated with destructive behavior. In the context of working, it suggests a subsequent motivation to conserve resources.51 Because of the conflict between work and family and dysfunctional politics in the workplace, employees are not interested in improving their performance. In addition, work-related illness and workplace injury can cause resource loss through exposure to these health problems.52,53 Usually, these losses are experienced through self-esteem damage or absorption in the workplace activities, so that they no longer care for or respect the people around them and conserve their resources to make up lost time. Toxic environments in the workplace can harm employees if they cannot regain resources that have been lost or keep the resources they still have safe.54

Evidence suggests that an employee’s perception of workplace obstacles and difficulties can lead to significant negative consequences.12 The perception that employees have about workplace challenges can negatively affect them. As a result of exposure to such circumstances, employees under such conditions may develop harmful perceptions that can alter their personalities or cause them to feel more overwhelmed. An unjust provision of information can reduce an employee’s job performance because of a political or organizational climate.55 We believe that the level of work-related stress is higher for male workers than for their female colleagues. As a result of the depersonalization among employees caused by WI, anxiety among them has increased. The anxiety level of high-educated employees is higher than non-highly educated ones.56,57 As the study of male employees in Pakistan shows, individuals with high levels of education are treated disrespectfully; they often experience more significant losses in dignity. The male is more dominant in Pakistani education because of a strict culture.58 This results in employees having high levels of job anxiety and indiscriminate treatment.

Workplace Ostracism and Knowledge Hiding Behavior

COR theory states that individuals have resources to satisfy their requirements. Therefore, people aim to maintain and gain valuable resources to decrease the likelihood of losing help from them or the environment (physical, social, cognitive). This perspective, grounded in COR theory, explains the impact of workplace ostracism on draining individuals’ valuable resources required in the workplace.37 The response under such circumstances may be activation of the individuals’ protection mechanisms, with continuous stress in response to ongoing resource dwindling contributing to a negative outcome.59 Workplace ostracism has been shown to hide knowledge and feelings during the workday, as predicted by the COR theory. Attempts to hide valuable information are more likely to occur when employees are unaware that they may be punished for withholding sensitive data. Therefore, knowing when to hide and when not to hide can have significant effects. Hence, we proposed the following hypotheses:

H1(a): Workplace ostracism is positively associated with evasive hiding.

H1(b): Workplace ostracism is positively associated with playing dumb.

H1(c): Workplace ostracism is positively associated with rationalized hiding.

Workplace Incivility and Knowledge Hiding

Members of an organization perform tasks that require knowledge, expertise, and ideas. The concept behind knowledge hiding refers to persons intentionally withholding or concealing information regarding a request for information.32 Although employees are expected to share information, they frequently find reasons to keep information to themselves. Afraid to lose power or status, with upset colleagues and a system that emphasizes individualized performance instead of pooled results.34 This is an example of three strategies used by employees to conceal knowledge. As an example, employees could play dumb, even though they already know the answers. In addition, it hides through evasive hiding tactics, offering to provide knowledge, but refuses to comply. The final form of rationalized hiding involves giving reasons ability cannot be shared or blaming third parties for preventing knowledge sharing.35

To better understand reciprocity and social exchange in the workplace,28 implement the concept of reciprocation. With workplace incivility expressed by one party to another, the process of social exchange allows these two parties to interact detrimentally. Using the “tit-for-tat” pattern, the authors establish signs of reciprocity and escalation in uncivil behavior. The association between workplace incivility and workplace withdrawal has been empirically shown.33 We hypothesize that employees who have been treated uncivilly conceal any knowledge they may have of such treatment is a request made on their behalf by those who have dealt with them in such a manner. Hence, we proposed the following hypotheses:

H2(a): Workplace incivility is positively associated evasive hiding.

H2(b): Workplace incivility is positively associated playing dumb.

H2(c): Workplace incivility is positively associated rationalized hiding.

The Mediating Role of Job Anxiety

Those not using coping resources during stressful times are likely to exhibit behaviors that lead to turnover intentions and workplace ostracism. Hence the theory of conservation of resources predicts detrimental consequences for individuals.38 A psychologically stressful atmosphere at the workplace raises job tensions that interfere with individuals’ ability to perform their duties and fulfill their organizations’ expectations. Workplace incivility and workplace ostracism at work can increase job anxiety among workers who feel attached to their careers or feel satisfied with their monetary benefits because workers are linked to their employment or feel satisfied with their economic benefits. However, these factors may also be viewed as essential, especially with knowing how to ostracize. In this light, it is necessary to examine whether job anxiety affects knowledge hiding of different types (evasive, rational, and playing dumb).

Several studies have shown that there is a correlation between job anxiety and work ostracism, and incivility. As COR theories, fear arises from a perceived or actual threat to a group or organization’s valuable resources. A study shows that it adversely affects factors, including self-esteem and confidence.43 It has been studied how job anxiety is related to workplace ostracism, incivility, and concealment of knowledge. In these situations, employees in entrepreneur SMEs are taken advantage of losing their ability to share knowledge. It is further believed the COR theory contends that rude behavior among co-workers can cause employees to become frustrated, stressed, and anxious, which will cause decreased productivity.44

By treating employees disrespectfully, supervisors and managers drain energy from employees and affect their performance.41 In addition, their colleague’s disrespect may cause the employee’s job anxiety for their emotions, causing them to become more stressed than they would otherwise. Besides workplace incivility, workplace ostracism, and knowledge hiding, they also suggested that employees’ anxiety about their jobs contributes to job insecurity. Therefore, based on the previous hypothesis, we suggest job anxiety could mediate workplace incivility. Based on our proposed hypothesis, we also state:

H3(a): Job Anxiety mediates the positive relationship between workplace ostracism and evasive hiding.

H3(b): Job Anxiety mediates the positive relationship between workplace ostracism and playing dumb.

H3(c): Job Anxiety mediates the positive relationship between workplace ostracism and rationalized hiding.

H4(a): Job Anxiety mediates the positive relationship between workplace incivility and evasive hiding.

H4(b): Job Anxiety mediates the positive relationship between workplace incivility and playing dumb.

H4(c): Job Anxiety mediates the positive relationship between workplace incivility and rationalized hiding.

Research Methodology

We gathered data from small and medium enterprises (SMEs) employees in five major Pakistan cities. According to the Small and Medium Enterprises Development Authority (SMEDA), SMEs account for almost 90% of all enterprises in the country; they hire 80% of nonagricultural employees, and their contribution of annual GDP is approximately 40%. For the purpose of data collection convenient sampling was applied.60 530 questionnaires were delivered to the enterprises through personal visits, and at the 315 filled questionnaires were received back from enterprises and rest of the enterprises were unable to fill the questionnaire. After screening it was found that some questionnaires were incomplete and we have to exclude 45 incomplete questionnaires from final sample. Now, 275 accurate questionnaires were available for data analysis. So, we considered 275 the final sample size with the response rate of 51.9%.

Measures

This study adapted questions items from previously published studies. All items are evaluated through five-point Likert-type scales where “1” (strongly disagree), “3” (neutral), and “5” (strongly agree). Three dimensions of knowledge hiding (evasive hiding, playing dumb, rationalized hiding) were the dependent variables of this study. Four items were used to measure each dimension of knowledge hiding and these were adapted from the study of Connelly et al,61 Thornton et al,62 Demirkasimoglu.63 This study used WO and WI as independent variables and used six items each for these two variables adapted from the studies of Zhao et al9 and Chen et al.64 Moreover, job anxiety was the mediating variable which was measured with five items adapted from the study of Allam.65

Study Results

Significantly, the study had adopted the PLS-SEM approach for data analysis. The PLS-SEM technique determines the dependent variables for ensuring maximum variance. PLS-SEM is the most effective prediction-orientated technique used for estimating study outcomes.66 Simultaneously, PLS-SEM can manage both the measurement (outer) and structural (inner) models. Perhaps, due to its colossal advantages, this approach is massively used for the data analysis of complex path models.67 Moreover, it also considers the small sample size, thus providing accurate results. Hence, for the present study PLS-SEM approach seems to be the best guide for conducting the study analysis.

Furthermore, the usage of the PLS-SEM methodology is on the increase, as Cepeda-Carrion et al68 recently pointed out, owing to its possible benefits in KM science.69 Taking these arguments into consideration, PLS-SEM appears to be beneficial for this study.

Common Method Bias

In a survey sample, common method variance (CMV) bias is a significant concern. This problem occurs when data are gathered from a common source.70 A single-factor test was used to evaluate the existence of CMV among constructs, as recommended by Harman.71 The results revealed that all the model’s items were classified into six constructs, with the first one accounting for 22.113% of overall variation, which is less than the 50% estimated.67 In addition, we used Smart PLS to run a complete collinearity evaluation test. According to Kock72 and Zafar et al,73 it is a relatively efficient and accurate method. The VIF values of the inner model for all latent constructs are smaller than the predefined threshold of 5, indicating that typical process bias is not a major concern in our study.

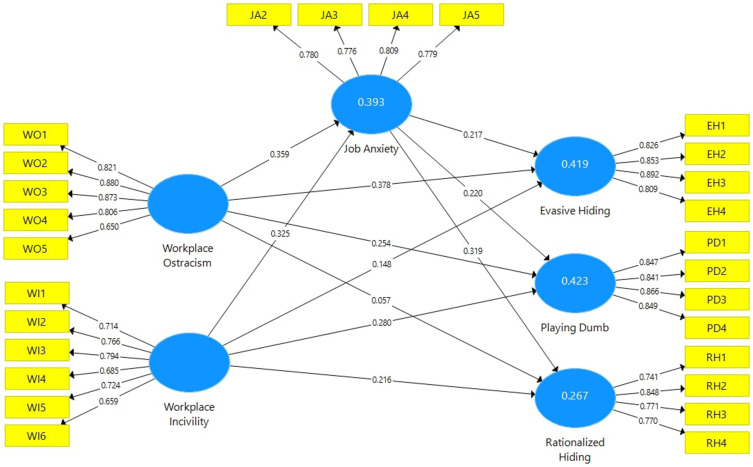

Measurement Model

The current research model is based on six latent constructs, as demonstrated in Figure 1. The instrument’s Reliability and Validity are evaluated using the measurement model. Hair et al67 suggested that measurement model assessment is based on the reliability of the indicator and construct, s convergent and discriminant validity. Cronbach’s Alpha (Cα) and indicator loading were employed to evaluate the instrument’s reliability. The indicators of the constructs were tested for convergent Validity to determine whether they accurately assess the study variables.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework.

The total sum of variance used in the indicators is replaced by the latent construct (ie, AVE), with CR depicting the consistency of the variables. In particular, the reliability of individual items is significantly reported in Table 1 and evaluated through items of factor loadings. The items containing a factor loading value equal to or greater than 0.6 are potentially reported and retained in the model.74 Indeed, all the variables having Cronbach’s alpha value greater than 0.7 had considerably been acceptable.75

Table 1.

Measurement Model Results

| Items | Loadings | Cα | CR | AVE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Workplace Ostracism | 0.867 | 0.904 | 0.657 | ||

| WO1 | 0.821 | ||||

| WO2 | 0.880 | ||||

| WO3 | 0.873 | ||||

| WO4 | 0.806 | ||||

| WO5 | 0.650 | ||||

| Workplace Incivility | 0.818 | 0.869 | 0.525 | ||

| WI1 | 0.714 | ||||

| WI2 | 0.766 | ||||

| WI3 | 0.794 | ||||

| WI4 | 0.685 | ||||

| WI5 | 0.724 | ||||

| WI6 | 0.659 | ||||

| Job Anxiety | |||||

| JA2 | 0.780 | 0.794 | 0.866 | 0.618 | |

| JA3 | 0.776 | ||||

| JA4 | 0.809 | ||||

| JA5 | 0.779 | ||||

| Evasive Hiding | 0.867 | 0.909 | 0.715 | ||

| EH1 | 0.826 | ||||

| EH2 | 0.853 | ||||

| EH3 | 0.892 | ||||

| EH4 | 0.809 | ||||

| Playing Dumb | 0.872 | 0.913 | 0.723 | ||

| PD1 | 0.847 | ||||

| PD2 | 0.841 | ||||

| PD3 | 0.866 | ||||

| PD4 | 0.849 | ||||

| Rationalized Hiding | RH1 | 0.741 | 0.790 | 0.864 | 0.614 |

| RH2 | 0.848 | ||||

| RH3 | 0.771 | ||||

| RH4 | 0.770 |

Notes: Ca> 0.7; CR>0.7; AVE>0.5; loadings>0.6. According to Hair et al, the discriminant validity of the measurement model shows the extent to which a particular measure is differentiated from the other ones. We followed the Fornell and Larcker and HTMT ratio to test the discriminant validity among the latent constructs (Table 2).

Furthermore, to enhance the reliability of the given construct, the composite reliability is also determined during the analysis as it is the most efficient tool for predicting the reliability compared to Cronbach’s alpha.75 The value of composite reliability greater than 0.7 fosters the reliability of all the items. In particular, convergent validity determines whether the construct properly measures the variables. Accordingly, convergent validity had assessed by estimating the average –variance- extracted (AVE). AVE examines whether the construct variance had appropriately explained from the chosen items.76 Consistent with Bagozzi and Yi,77 the cut-off value for the average variance had found to be 0.5, with all the constructs having the AVE value higher than the suggested threshold (ie, referred to Table 1). Figure 2 demonstrates the convergent validity of the adopted measurement model.

Figure 2.

Measurement Model.

In addition, two methods are included to validate the proposed model’s discriminant validity, namely the Fornell-Larcker criteria and Heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) ratios.67 Table 2 indicates that discriminant validity is confirmed based on the Fornell-Larcker criteria since each column’s top value of the association of measures is maximum.76 In addition, Henseler et al proposed a novel method for determining discriminant validity. They argued that although the Fornell-Larcker criterion can efficiently assess discriminant validity; however, it could not identify the absence of discriminant validity. Therefore, we also evaluated discriminant validity using the HTMT ratio. The values of HTMT for the variables used in this study are seen in Table 3. According to the criteria, all variables’ HTMT values must be smaller than 0.90.67 As seen in Table 2, the HTMT values for all measures are less than 0.90, indicating that all variables under analysis have discriminant validity.

Table 2.

Discriminant Validity

| Fornell-Larcker Criterion | Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EH | JA | PD | RH | WI | WO | EH | JA | PD | RH | WI | WO | ||

| EH | 0.846 | EH | |||||||||||

| JA | 0.520 | 0.786 | JA | 0.624 | |||||||||

| PD | 0.553 | 0.527 | 0.851 | PD | 0.634 | 0.627 | |||||||

| RH | 0.534 | 0.475 | 0.471 | 0.783 | RH | 0.633 | 0.595 | 0.560 | |||||

| WI | 0.529 | 0.570 | 0.579 | 0.436 | 0.725 | WI | 0.622 | 0.696 | 0.683 | 0.533 | |||

| WO | 0.604 | 0.580 | 0.573 | 0.389 | 0.682 | 0.810 | WO | 0.683 | 0.688 | 0.655 | 0.450 | 0.805 | |

Abbreviations: EH, Evasive Hiding; JA, Job Anxiety; PD, Playing Dumb; RH, Rationalized Hiding; WI, Workplace Incivility; WO, Workplace Ostracism.

Table 3.

Effect Size, Coefficient of Determination and Predictive Relevance

| VIF | R Square | Q Square | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evasive Hiding | Job Anxiety | Playing Dumb | Rationalized Hiding | Endogenous Construct | Endogenous Construct | |

| Evasive Hiding | 0.419 | 0.288 | ||||

| Playing Dumb | 0.423 | 0.300 | ||||

| Rationalized Hiding | 0.267 | 0.152 | ||||

| Job Anxiety | 1.649 | 1.649 | 1.649 | 0.393 | 0.234 | |

| Workplace Incivility | 2.043 | 1.869 | 2.043 | 2.043 | ||

| Workplace Ostracism | 2.081 | 1.869 | 2.081 | 2.081 | ||

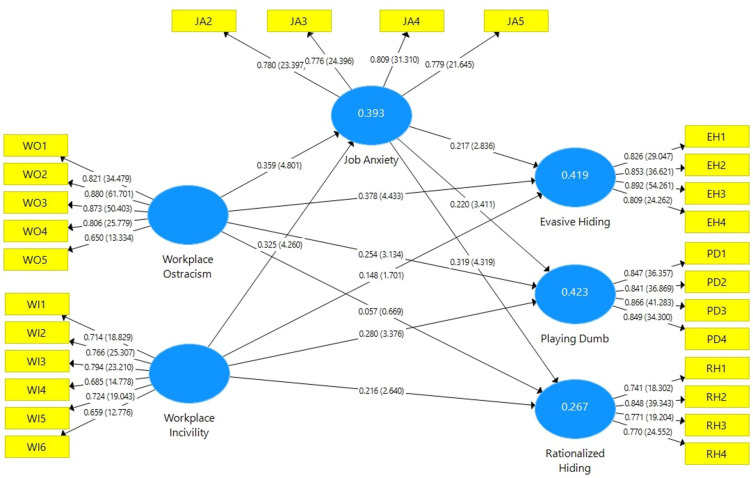

Structural Model Assessment

The second phase in PLS-SEM evaluation is structural model assessment. The assessment of the structural path model involves assessing the multicollinearity, model’s predictive relevance and empirical significance of path coefficients, and the confidence level.79 The present study employed general recommendations for evaluating the structural model and interpreting findings from Ringle et al.80 However, specific recommendations from Preacher and Hayes81 were also considered for mediation analysis.

The variance inflation factor (VIF) values were examined in this study to verify the model’s collinearity concerns. Experts believe that if the inner VIF values are below 5, data has no collinearity problems.74 The current study’s findings illustrate that the values of the inner VIF are lower than the cut-off criteria. It demonstrates no collinearity in the data used in this analysis and confirms the model fitness. Furthermore, we have four endogenous constructs in our model (see Figure 2). The R2 for Evasive Hiding 0.419 (Q2 = 0.288), Playing Dumb was 0.423 (Q2 = 0.300), Rationalized Hiding was 0.267 (Q2 = 0.152) and Job Anxiety was 0.393 (Q2 = 0.234) which indicates that 41.9%, 42.3%,26.7% and 39.3% of the variance in the respective constructs can be explained by their predictors. Q2 values greater than 0 indicate sufficient predictive relevance (see Table 4). Furthermore, the effect size (f2) results are presented in Table 4. The finding reveals that the values for f2 of the relationships are lower to higher levels, confirming model fitness.

Table 4.

Direct Effects

| Proposal Effect | Beta | St. Dev. | T Values | f2 | Confirmed | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Workplace Ostracism -> Evasive Hiding | H1a | 0.378*** | 0.085 | 4.452 | 0.118 | Yes |

| Workplace Ostracism -> Playing Dumb | H1b | 0.254*** | 0.082 | 3.112 | 0.054 | Yes |

| Workplace Ostracism -> Rationalized Hiding | H1c | 0.057NS | 0.084 | 0.676 | 0.002 | No |

| Workplace Incivility -> Evasive Hiding | H2a | 0.148NS | 0.087 | 1.699 | 0.018 | No |

| Workplace Incivility -> Playing Dumb | H2b | 0.280*** | 0.082 | 3.402 | 0.067 | Yes |

| Workplace Incivility -> Rationalized Hiding | H2c | 0.216** | 0.080 | 2.684 | 0.031 | Yes |

Notes: ***p< 0.001; **p< 0.01.

Next, to analyze the developed hypothesis, we ran a bootstrapping of 5000 subsamples. First, we assessed the direct relationships before looking at the mediation effects. The results of direct effects are presented in Table 4 and Figure 3. For H1(a) to H1(c), findings reveal that Workplace Ostracism was significantly associated with Evasive Hiding (β=0.378; p< 0.001) and Playing Dumb (β=0.254; p< 0.001) but was not significantly related to Rationalized Hiding (0.057; p> 0.05) which supports H1a and H1(b) while H1(c) is not supported. Moreover, For H2(a) to H2(c), Study findings show that Workplace Incivility was insignificantly associated with Evasive Hiding (0.148; p>0.05) but significantly related to Playing Dumb (β=0.280; p< 0.001) Rationalized Hiding (β=0.216; p< 0.001), which support H2(a) and H2 (c) while H1(a) is not supported.

Figure 3.

Structural Model.

We performed the mediation analysis in Smart-PLS using the Preacher & Hayes bias-corrected bootstrapping approach at a 95% confidence interval to test the six mediating hypotheses. The rationale for employing the bootstrapping technique of Hayes and Preacher is that it is a nonparametric test that assesses the indirect effects by sampling the data set repeatedly (Table 5).

Table 5.

Direct, Indirect and Total Effects

| Β | T Statistics | Β | T Statistics | β | T Statistics | Conclusion | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H3a | WO-> JA-> EH | 0.378*** | 4.433 | 0.078* | 2.198 | 0.455*** | 5.968 | Partial Mediation |

| LLCI | 0.200 | 0.021 | 0.294 | |||||

| ULCI | 0.534 | 0.161 | 0.591 | |||||

| H3b | WO-> JA-> PD | 0.254*** | 3.134 | 0.079** | 2.682 | 0.333*** | 4.557 | Partial Mediation |

| LLCI | 0.087 | 0.030 | 0.182 | |||||

| ULCI | 0.402 | 0.142 | 0.470 | |||||

| H3c | WO-> JA-> RH | 0.057NS | 0.669 | 0.114** | 2.841 | 0.171* | 2.185 | Full Mediation |

| LLCI | −0.120 | 0.049 | 0.013 | |||||

| ULCI | 0.213 | 0.207 | 0.320 | |||||

| H4a | WI-> JA-> EH | 0.148NS | 1.701 | 0.070* | 2.478 | 0.218* | 2.591 | Full Mediation |

| LLCI | −0.016 | 0.020 | 0.058 | |||||

| ULCI | 0.327 | 0.132 | 0.393 | |||||

| H4b | WI-> JA-> PD | 0.280*** | 3.376 | 0.071** | 2.588 | 0.352*** | 4.178 | Partial Mediation |

| LLCI | 0.113 | 0.026 | 0.182 | |||||

| ULCI | 0.437 | 0.133 | 0.515 | |||||

| H4c | WI-> JA-> RH | 0.216** | 2.640 | 0.104*** | 3.162 | 0.319*** | 3.945 | Partial Mediation |

| LLCI | 0.057 | 0.047 | 0.163 | |||||

| ULCI | 0.381 | 0.175 | 0.481 | |||||

Notes: ***p< 0.001; **p< 0.01; *p< 0.05.

Abbreviations: LLCI, lower limit confidence interval; ULCI, upper limit confidence interval.

H3(a), H3(b), and H3(c) the mediating role of job anxiety in the relationship between Workplace Ostracism and three dimensions of knowledge hiding (Evasive hiding, playing dumb, and Rationalized Hiding) was proposed. Results reveal that sources of knowledge significantly mediate the relationship between Workplace Ostracism and Evasive hiding (β=0.078; t< 2.198), playing dumb (β=0.079; t=2.682) and Rationalized Hiding (β=0.114; t=2.841) which supports H3(a), H3(b), and H3(c). Additionally, it can be observed that job anxiety partially mediates the relationship between Workplace Ostracism and evasive hiding, and playing dumb, while fully mediates Workplace Ostracism and its relationship with Rationalized Hiding, As seen in Table 5, Moreover, For H4(a), H4(b), and H4(c) the mediating role of job anxiety in the relationship between Workplace Incivility and three dimensions of knowledge hiding (Evasive hiding, playing dumb and Rationalized Hiding) was proposed. Results reveal that sources of knowledge significantly mediate the relationship between Workplace Incivility and Evasive hiding (β=0.070; t=2.478), playing dumb (β=0.071; t=2.588) and Rationalized Hiding (β=0.104; t=3.162) which supports H4a, H4b, and H4c. Additionally, it can be observed that job anxiety partly mediates the association between Workplace Incivility and playing dumb, and Rationalized Hiding while fully mediates Workplace Incivility and its relationship with evasive hiding (see Table 5).

Discussion

Researchers have focused their attention on workplace ostracism and workplace incivility, affecting individuals’ refusal to reveal information. An environment with coworkers encourages employee confidence and relaxes the mind to maximize their effectiveness. As a basis for making theoretical predictions, the COR theory was employed in this study. Compared to a cooperative workplace environment, people working in an uncooperative work environment have a negative attitude toward their jobs and show little interest in their assigned work.50 The depletion of resources is also associated with destructive behavior. In the context of working, it suggests a subsequent motivation to conserve resources.51 Because of the conflict between work and family and dysfunctional politics in the workplace, employees are not interested in improving their performance. In contrast, a work environment without coworkers and a work environment without welfare contribute to job anxiety. The primary cause of job anxiety for employees is when their organization suffers from WO or WI. The model was tested on four hypotheses.

It is hypothesized that workplace ostracism positively influences evasive hiding, rationalized hiding and playing dumb. Furthermore, WO appear to be positively influenced knowledge hiding, as shown by the results. In effect, hypotheses 1(a), 1(b) are supported and 1(c) is not supported, where workplace ostracism results in more knowledge being concealed. WO is not influenced on rationalized hiding because organization may use some advanced technology to observe employee behavior or some employees ethically consider it as bad habit in different settings. COR theory also supports this result and these results are also in line with the previous study.58 Organizations, employees, and key stakeholder groups cooperate when trust and honesty are present; however, workplace ostracism can damage the relationships. Therefore, workplace anxiety, insomnia, and depression contribute to the concealment of information by workers.

The research found that WI and the three-component strategies (playing dumb, evasive hiding, rationalized hiding) were positively correlated. Employees with high WI at work will probably hide knowledge. As a result, we associate WI with higher concealment of expertise, as Hypothesis 2(b), 2(c) suggests but surprisingly results of this study not supported 2(a). In some settings an employee may show incivility in the reaction of someone’s rude behavior but he does not want to hide its knowledge as a senior member of the team, finding is consistent with previous study of Khoreva and Wechtler.21 Rasool et al82 also examined 180 Chinese bank employees and discovered we positively related workplace incivility tension to knowledge hiding. This is consistent through the COR perspective and with the Resource-Based View theory (RBV). We have shown the correlation between WI and information concealment in previous studies.

These findings corroborate hypotheses 3(a), 3(b), and 3(c) and 4(a), 4(b), 4(c), showing that job anxiety arises from workplace incivility, ostracism, and knowledge hiding. The current study corroborates previous studies and is supported by COR theory. In a study of Pakistani public and private sector telecom organizations, Prem et al83 found that employees hide their expertise from their colleagues out of job anxiety. Our findings show that job anxiety plays a significant role in the phenomenon that workplace incivility and workplace ostracism cause those in the immediate workplace to separate from their colleagues to become dehumanized.

Theoretical Implications

The study findings advance our understanding in the area of psychology and organization behavior. The individual’s willingness is the primary obligation because knowledge is “intellectual property,” meaning that organizations cannot force employees to transfer knowledge. To understand why knowledge hiding occurs, it is essential to understand individual antecedents. Researchers in the field of knowledge hiding and traditional research in the area explained the well-known phenomenon by predicting many other factors, including interpersonal (peer relationships, supervisor relationships), cultural factors (culture and justice), and individual abilities (eg, political intelligence, interpersonal relations). Therefore, this study aims to add to the literature by examining the possibility that workplace ostracism can conceal information. This hostile work environment may cause individuals to alter their involvement in the social environment. As a result, we provide further insight into how workplace ostracism plays a significant role in stress management. According to our hypothesis, people conceal their knowledge in response to resources that are at risk.

According to this study finding, an exchange system based on the non-escalating tit-for-tat propositions was made. When employees are treated unprofessional or disrespectful, they will probably show no signs of retaliation. When workplace incivility lacks a rational purpose, it is not harmful. Retaliation will most likely be subtle and would not be seen by the perpetrators. It is prevalent for managers to reprimand employees for overt retaliation in team-oriented organizations. It is not unusual for perpetrators to ask their victims whether they are aware of workplace incivility in an attempt at revenge. A study examining workplace incivility and knowledge concealment has not been conducted to our knowledge. The first study to show conceptually and empirically that workplace incivility affects knowledge hiding was reported here. Future researchers can use it to explore whether it will link workplace incivility to information concealment.

This study contributes to understanding cognitive processes in non-participatory behaviors, such as knowledge hiding following the COR theory perspective. Increased job anxiety raises emotional disturbances and exacerbates behavioral responses, such as hiding knowledge. These studies contribute to the literature on knowledge hiding by challenging the notion of ignorance to explore how the practice is integrated with complaints of workplace incivility.35 Thus, these studies contribute to knowledge hiding literature. A study further pointed out that although financial rewards can increase commitment to a company, its environment is fundamental in enabling employees to achieve peak performance.

Managerial Implications

Even though prior research had deemed the risks associated with knowledge hiding higher, empirical research was relatively limited, making this study relevant. Workplace ostracism is a crucial factor influencing knowledge hiding behaviors in the workplace. Individuals who are ostracized experience more job strain and deplete their resources, which induces the knowledge-hiding mechanism and results in resource retention. Work ostracism at work is expensive for a company, and preventing it by cultivating a culture that encourages interpersonal relationships among coworkers is an excellent way to minimize the effects of stress. The encouragement of interdependent cooperative goals and a team-based reward system can prevent workplace ostracism.8 The use of decentralized reward systems helps to foster cooperation and to avoid ostracism.

Employers should consider these findings to reduce knowledge hiding behaviors at work. Focusing efforts on the people who already work there and those who will soon join them can effectively manage workplace incivility. To get existing employees to be civil at work, managers first need to create awareness among staff. Posters can be displayed in inaccessible areas, and communications can be made in meetings encouraging employees to practice civility and training sessions can be conducted. Leadership behaviors, including supervisors, need to be modelled by leaders.

Similarly, complaints should be taken seriously against any employees who display uncivilized behavior. Employees will feel comfortable with incivility in an organization if it tolerates small-scale incivility. These measures motivate employees to cooperate, build strong bonds, and create a positive work environment. By eliminating knowledge concealment, we are preventing knowledge leakage. A communication system that works effectively and coaching that reduces employed stress is an excellent strategy to detect such issues. A manager must also figure out what causes employed stress, aid as professional psychological counselling, and promote employee involvement.

Study Limitations and Future Research

There is much to be gained from the present study, but its interpretation also has limitations. We based these results on a single industry, making it harder to generalize because labor demands, cultural differences, and mobility vary across the sectors. Industry type and culture are two main elements which are most affected on behaviors of employees, so future researchers should test model in different industry type and in different cultural context. It may be helpful to test the model in organizations with various cultures and environments. Two reasons may contribute to the lack of a complete explanation for the perceived workplace ostracism and knowledge concealment, even though the time-lag analysis has established a causal link. A person’s strengths and weaknesses, including their psychological makeup and family dynamics, may also contribute to stress. Those with fewer years of experience likely feel more ostracized, while those with more tenure conceal knowledge more often. We, therefore, recommend that future research use longitudinal methods with specific demographic data.

Conclusion

Workplace ostracism and workplace incivility at work deplete employees’ resources, which leads to job anxiety, causing them to become exhausted. A vertically integrated business organization must pay more benefits than other companies if workers suffer from job anxiety. Job anxiety was predicted to mediate the relationship between workplace incivility, workplace ostracism, and information concealment. Having identified such associations, the present study aims to identify the factors that influence behavior towards knowledge hiding based on previous research. Workplace incivility plays a significant role in knowledge hiding by employees when they perceive uncivil behavior from their teammates.

Funding Statement

This work is supported by the construct program of applied characteristic discipline “Applied Economics” Hunan Province.

Data Sharing Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethical Approval

All participants gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study. All procedures performed were by the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standard. The ethical committee approved all the procedures of Department of Commerce & Business, Government College University Faisalabad, Layyah Campus, Pakistan.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Singh SK. Territoriality, task performance, and workplace deviance: empirical evidence on role of knowledge hiding. J Bus Res. 2019;97:10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.12.034 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xiao M, Cooke FL. Why and when knowledge hiding in the workplace is harmful: a review of the literature and directions for future research in the Chinese context. Asia Pacific J Hum Resour. 2019;57(4):470–502. doi: 10.1111/1744-7941.12198 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Han MS, Masood K, Cudjoe D, Wang Y. Knowledge hiding as the dark side of competitive psychological climate. Leadersh Organ Dev J. 2021;42(2):195–207. doi: 10.1108/LODJ-03-2020-0090 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumar Jha J, Varkkey B. Are you a cistern or a channel? Exploring factors triggering knowledge-hiding behavior at the workplace: evidence from the Indian R&D professionals. J Knowl Manag. 2018;22(4):824–849. doi: 10.1108/JKM-02-2017-0048 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Irum A, Ghosh K, Pandey A. Workplace incivility and knowledge hiding: a research agenda. Benchmarking an Int J. 2020;27(3):958–980. doi: 10.1108/BIJ-05-2019-0213 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anand P, Hassan Y. Knowledge hiding in organizations: everything that managers need to know. Dev Learn Organ an Int J. 2019;33(6):12–15. doi: 10.1108/DLO-12-2018-0158 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Di Vaio A, Hasan S, Palladino R, Profita F, Mejri I. Understanding knowledge hiding in business organizations: a bibliometric analysis of research trends, 1988–2020. J Bus Res. 2021;134:560–573. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.05.040 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Clercq D, Haq IU, Azeem MU. Workplace ostracism and job performance: roles of self-efficacy and job level. Pers Rev. 2019;48(1):184–203. doi: 10.1108/PR-02-2017-0039 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao H, Xia Q, He P, Sheard G, Wan P. Workplace ostracism and knowledge hiding in service organizations. Int J Hosp Manag. 2016;59:84–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2016.09.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jahanzeb S, De Clercq D, Fatima T. Organizational injustice and knowledge hiding: the roles of organizational dis-identification and benevolence. Manag Decis. 2021;59(2):446–462. doi: 10.1108/MD-05-2019-0581 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mohsin M, Zhu Q, Wang X, Naseem S, Nazam M. The empirical investigation between ethical leadership and knowledge-hiding behavior in financial service sector: a moderated-mediated model. Front Psychol. 2021;12:798631. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.798631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo L, Cheng K, Luo J. The effect of exploitative leadership on knowledge hiding: a conservation of resources perspective. Leadersh Organ Dev J. 2021;42(1):83–98. doi: 10.1108/LODJ-03-2020-0085 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anser MK, Ali M, Usman M, Rana MLT, Yousaf Z. Ethical leadership and knowledge hiding: an intervening and interactional analysis. Serv Ind J. 2021;41(5–6):307–329. doi: 10.1080/02642069.2020.1739657 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin M, Zhang X, Ng BCS, Zhong L. To empower or not to empower? Multilevel effects of empowering leadership on knowledge hiding. Int J Hosp Manag. 2020;89:102540. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102540 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miminoshvili M, Černe M. Workplace inclusion–exclusion and knowledge-hiding behaviour of minority members. Knowl Manag Res Pract. 2021:1–14. doi: 10.1080/14778238.2021.1960914 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nguyen T-M, Malik A, Budhwar P. Knowledge hiding in organizational crisis: the moderating role of leadership. J Bus Res. 2022;139:161–172. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.09.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu Y, Zhu JNY, Lam LW. Obligations and feeling envied: a study of workplace status and knowledge hiding. J Manag Psychol. 2020;35(5):347–359. doi: 10.1108/JMP-05-2019-0276 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rasheed K, Mukhtar U, Anwar S, Hayat N. Workplace knowledge hiding among front line employees: moderation of felt obligation. VINE J Inf Knowl Manag Syst. 2020. doi: 10.1108/VJIKMS-04-2020-0073 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ma L, Zhang X, Ding X. Enterprise social media usage and knowledge hiding: a motivation theory perspective. J Knowl Manag. 2020;24(9):2149–2169. doi: 10.1108/JKM-03-2020-0234 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Issac AC, Baral R, Bednall TC. What is not hidden about knowledge hiding: deciphering the future research directions through a morphological analysis. Knowl Process Manag. 2021;28(1):40–55. doi: 10.1002/kpm.1657 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khoreva V, Wechtler H. Exploring the consequences of knowledge hiding: an agency theory perspective. J Manag Psychol. 2020;35(2):71–84. doi: 10.1108/JMP-11-2018-0514 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ghani U, Zhai X, Spector JM, et al. Knowledge hiding in higher education: role of interactional justice and professional commitment. High Educ. 2020;79(2):325–344. doi: 10.1007/s10734-019-00412-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Issac AC, Baral R, Bednall TC. Don’t play the odds, play the man. Eur Bus Rev. 2020;32(3):531–551. doi: 10.1108/EBR-06-2019-0130 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Riaz S, Xu Y, Hussain S. Workplace ostracism and knowledge hiding: the mediating role of job tension. Sustainability. 2019;11(20):5547. doi: 10.3390/su11205547 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Naseem S, Fu GL, Mohsin M, et al. Development of an inexpensive functional textile product by applying accounting cost benefit analysis. Ind Textila. 2020;71(1):17–22. doi: 10.35530/IT.071.01.1692 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gürlek M. Antecedents of knowledge hiding in organizations: a study on knowledge workers. Econ Bus Organ Res. 2020;2020:20–32. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao H, Xia Q. An examination of the curvilinear relationship between workplace ostracism and knowledge hoarding. Manag Decis. 2017;55(2):331–346. doi: 10.1108/MD-08-2016-0607 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aljawarneh NMS, Atan T. Linking tolerance to workplace incivility, service innovative, knowledge hiding, and job search behavior: the mediating role of employee cynicism. Negot Confl Manag Res. 2018;11(4):298–320. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chung YW. Workplace ostracism and workplace behaviors: a moderated mediation model of perceived stress and psychological empowerment. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2018;31(3):304–317. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2018.1424835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li N, Bao S, Naseem S, Sarfraz M, Mohsin M. Extending the association between leader-member exchange differentiation and safety performance: a moderated mediation model. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2021;14:1603. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S335199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Howard MC, Cogswell JE, Smith MB. The antecedents and outcomes of workplace ostracism: a meta-analysis. J Appl Psychol. 2020;105(6):577. doi: 10.1037/apl0000453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu W, Zhou ZE, Che XX. Effect of workplace incivility on OCB through burnout: the moderating role of affective commitment. J Bus Psychol. 2019;34(5):657–669. doi: 10.1007/s10869-018-9591-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hülsheger UR, van Gils S, Walkowiak A. The regulating role of mindfulness in enacted workplace incivility: an experience sampling study. J Appl Psychol. 2021;106(8):1250. doi: 10.1037/apl0000824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang C-H, Chen H-T. Relationships among workplace incivility, work engagement and job performance. J Hosp Tour Insights. 2020;3(4):415–429. doi: 10.1108/JHTI-09-2019-0105 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Armstrong N. Management of nursing workplace incivility in the health care settings: a systematic review. Workplace Health Saf. 2018;66(8):403–410. doi: 10.1177/2165079918771106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shi Y, Guo H, Zhang S, et al. Impact of workplace incivility against new nurses on job burn-out: a cross-sectional study in China. BMJ Open. 2018;8(4):e020461. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Samma M, Zhao Y, Rasool SF, Han X, Ali S. Exploring the relationship between innovative work behavior, job anxiety, workplace ostracism, and workplace incivility: empirical evidence from small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs). In: Healthcare. Vol. 8. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute; 2020:508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koon V-Y, Pun P-Y. The mediating role of emotional exhaustion and job satisfaction on the relationship between job demands and instigated workplace incivility. J Appl Behav Sci. 2018;54(2):187–207. doi: 10.1177/0021886317749163 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Walsh BM, Lee JJ, Jensen JM, McGonagle AK, Samnani A-K. Positive leader behaviors and workplace incivility: the mediating role of perceived norms for respect. J Bus Psychol. 2018;33(4):495–508. doi: 10.1007/s10869-017-9505-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marchiondo LA, Cortina LM, Kabat‐Farr D. Attributions and appraisals of workplace incivility: finding light on the dark side? Appl Psychol. 2018;67(3):369–400. doi: 10.1111/apps.12127 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jin D, Kim K, DiPietro RB. Workplace incivility in restaurants: who’s the real victim? Employee deviance and customer reciprocity. Int J Hosp Manag. 2020;86:102459. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102459 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gul RF, Liu D, Jamil K, Baig SA, Awan FH, Liu M. Linkages between market orientation and brand performance with positioning strategies of significant fashion apparels in Pakistan. Fash Text. 2021;8(1):1–19. doi: 10.1186/s40691-021-00254-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sauter SL, Hurrell JJ Jr. Occupational health contributions to the development and promise of occupational health psychology. J Occup Health Psychol. 2017;22(3):251. doi: 10.1037/ocp0000088 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Demir S. The relationship between psychological capital and stress, anxiety, burnout, job satisfaction, and job involvement. Eurasian J Educ Res. 2018;18(75):137–154. [Google Scholar]

- 45.De Clercq D, Haq IU, Azeem MU. Self-efficacy to spur job performance. Manag Decis. 2018;56(4):891–907. doi: 10.1108/MD-03-2017-0187 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aguiar-Quintana T, Nguyen H, Araujo-Cabrera Y, Sanabria-Díaz JM. Do job insecurity, anxiety and depression caused by the COVID-19 pandemic influence hotel employees’ self-rated task performance? The moderating role of employee resilience. Int J Hosp Manag. 2021;94:102868. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2021.102868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Modaresnezhad M, Andrews MC, Mesmer‐Magnus J, Viswesvaran C, Deshpande S. Anxiety, job satisfaction, supervisor support and turnover intentions of mid‐career nurses: a structural equation model analysis. J Nurs Manag. 2021;29(5):931–942. doi: 10.1111/jonm.13229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saquib N, Zaghloul MS, Saquib J, Alhomaidan HT, Al‐Mohaimeed A, Al‐Mazrou A. Association of cumulative job dissatisfaction with depression, anxiety and stress among expatriate nurses in Saudi Arabia. J Nurs Manag. 2019;27(4):740–748. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhou J, Yang Y, Qiu X, et al. Serial multiple mediation of organizational commitment and job burnout in the relationship between psychological capital and anxiety in Chinese female nurses: a cross-sectional questionnaire survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2018;83:75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Prapanjaroensin A, Patrician PA, Vance DE. Conservation of resources theory in nurse burnout and patient safety. J Adv Nurs. 2017;73(11):2558–2565. doi: 10.1111/jan.13348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Holmgreen L, Tirone V, Gerhart J, Hobfoll SE. Conservation of resources theory. In: The Handbook Of Stress And Health: A Guide To Research And Practice. Sage; 2017:443–457. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Meng B, Choi K. Employees’ sabotage formation in upscale hotels based on conservation of resources theory (COR): antecedents and strategies of attachment intervention. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag. 2021;33(3):790–807. doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-08-2020-0859 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Awan FH, Dunnan L, Jamil K, Gul RF, Guangyu Q, Idrees M. Impact of role conflict on intention to leave job with the moderating role of job embeddedness in banking sector employees. Front Psychol. 2021; 12:4866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Debus ME, Unger D. The interactive effects of dual‐earner couples’ job insecurity: linking conservation of resources theory with crossover research. J Occup Organ Psychol. 2017;90(2):225–247. doi: 10.1111/joop.12169 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Modrzyński R. Conservation of resources theory by Stevan E. Hobfoll and prediction of alcohol dependent persons’ abstinence. Alcohol Drug Addict i Narkom. 2018;31(2):147–170. doi: 10.5114/ain.2018.79992 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lin S-H, Scott BA, Matta FK. The dark side of transformational leader behaviors for leaders themselves: a conservation of resources perspective. Acad Manag J. 2019;62(5):1556–1582. doi: 10.5465/amj.2016.1255 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gul RF, Dunnan L, Jamil K, Awan FH, Ali B, Abusive QA. supervision and its impact on knowledge hiding behavior among sales force. Front Psychol. 2021; 30:6138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhu H, Lyu Y, Deng X, Ye Y. Workplace ostracism and proactive customer service performance: a conservation of resources perspective. Int J Hosp Manag. 2017;64:62–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2017.04.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sepahvand R, Mofrad MM. Workplace ostracism and knowledge hiding: the mediating role of job tension (Case study of nurses of public hospitals employee’s in Lorestan). Iran J Ergon ISSN. 2021;2345:5365. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kothari CR. Research Methodology: Methods and Techniques. New Age International; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Connelly CE, Zweig D, Webster J, Trougakos JP. Knowledge hiding in organizations. J Organ Behav. 2012;33(1):64–88. doi: 10.1002/job.737 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Thornton B, Lovley A, M Ryckman R, Gold JA. Playing dumb and knowing it all: competitive orientation and impression management strategies. Individ Differ Res. 2009;7(4):265–271. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Demirkasimoglu N. Knowledge hiding in academia: is personality a key factor? Int J High Educ. 2016;5(1):128–140. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chen Y, Wang Z, Peng Y, Geimer J, Sharp O, Jex S. The multidimensionality of workplace incivility: cross-cultural evidence. Int J Stress Manag. 2019;26(4):356. doi: 10.1037/str0000116 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Allam Z. A study of relationship of job burnout and job anxiety with job involvement among Bank employees. Manag Labour Stud. 2007;32(1):136–145. doi: 10.1177/0258042X0703200109 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Roldán JL, Sánchez-Franco MJ. Variance-based structural equation modeling: guidelines for using partial least squares in information systems research. In: Research Methodologies, Innovations and Philosophies in Software Systems Engineering and Information Systems. IGI Global; 2012:193–221. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Henseler J, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J Acad Mark Sci. 2015;43(1):115–135. doi: 10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cepeda-Carrion G, Cegarra-Navarro J-G, Cillo V. Tips to use partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) in knowledge management. J Knowl Manag. 2019;23(1):67–89. doi: 10.1108/JKM-05-2018-0322 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Elrehail H, Emeagwali OL, Alsaad A, Alzghoul A. The impact of transformational and authentic leadership on innovation in higher education: the contingent role of knowledge sharing. Telemat Informatics. 2018;35(1):55–67. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2017.09.018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee J-Y, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88(5):879. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Harman HH. Modern Factor Analysis. University of Chicago press; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kock N. Common method bias in PLS-SEM: a full collinearity assessment approach. Int J e-Collab. 2015;11(4):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zafar AU, Qiu J, Shahzad M. Do digital celebrities’ relationships and social climate matter? Impulse buying in f-commerce. Internet Res. 2020;30(6):1731–1762. doi: 10.1108/INTR-04-2019-0142 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hair JJF, Sarstedt M, Hopkins L, Kuppelwieser VG. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Eur Bus Rev. 2014; 26:106–121. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Werts CE, Linn RL, Jöreskog KG. Intraclass reliability estimates: testing structural assumptions. Educ Psychol Meas. 2007;34(1):25–33. doi: 10.1177/001316447403400104 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fornell C, Larcker DF. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res. 1981;18(1):39–50. doi: 10.1177/002224378101800104 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bagozzi RP, Yi Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J Acad Mark Sci. 1988;16(1):74–94. doi: 10.1007/BF02723327 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hair JJF, Howard MC, Nitzl C. Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. J Bus Res. 2020;109:101–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.11.069 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ringle CM, Sarstedt M, Mitchell R, Gudergan SP. Partial least squares structural equation modeling in HRM research. Int J Hum Resour Manag. 2020;31(12):1617–1643. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2017.1416655 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods. 2008;40(3):879–891. doi: 10.3758/BRM.40.3.879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rasool SF, Wang M, Zhang Y, Samma M. Sustainable work performance: the roles of workplace violence and occupational stress. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(3):912. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17030912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Prem K, Cook AR, Jit M. Projecting social contact matrices in 152 countries using contact surveys and demographic data. PLoS Comput Biol. 2017;13(9):e1005697. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]