Abstract

We previously show that fatty acid-binding protein 3 (FABP3) triggers α-synuclein (Syn) accumulation and induces dopamine neuronal cell death in Parkinson disease mouse model. But the role of fatty acid-binding protein 7 (FABP7) in the brain remains unclear. In this study we investigated whether FABP7 was involved in synucleinopathies. We showed that FABP7 was co-localized and formed a complex with Syn in Syn-transfected U251 human glioblastoma cells, and treatment with arachidonic acid (100 M) significantly promoted FABP7-induced Syn aggregation, which was associated with cell death. We demonstrated that synthetic FABP7 ligand 6 displayed a high affinity against FABP7 with Kd value of 209 nM assessed in 8-anilinonaphthalene-1-sulfonic acid (ANS) assay; ligand 6 improved U251 cell survival via disrupting the FABP7–Syn interaction. We showed that activation of phospholipase A2 (PLA2) by psychosine (10 M) triggered oligomerization of endogenous Syn and FABP7, and induced cell death in both KG-1C human oligodendroglia cells and oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs). FABP7 ligand 6 (1 M) significantly decreased Syn oligomerization and aggregation thereby prevented KG-1C and OPC cell death. This study demonstrates that FABP7 triggers α-synuclein oligomerization through oxidative stress, while FABP7 ligand 6 can inhibit FABP7-induced Syn oligomerization and aggregation, thereby rescuing glial cells and oligodendrocytes from cell death.

Keywords: synucleinopathies, α-synuclein oligomerization, fatty acid binding protein 7, arachidonic acid, psychosine, cell death

Introduction

Synucleinopathies, which include Parkinson’s disease (PD), diffuse Lewy body disease (DLBD), and multiple system atrophy (MSA), are attributed to abnormal accumulation and abundant deposition of the protein alpha-synuclein (ɑSyn), which contains 140 amino acids, in the presynaptic terminals of neurons [1, 2]. In patients with PD, ɑSyn misfolded and aggregated type in neurons form Lewy bodies (LBs) and Lewy neurites (LNs), which are closely associated with neurodegenerative cell death [2]. However, in patients with MSA, ɑSyn predominantly accumulates in oligodendrocytes (OLGs) and form glial cytoplasmic inclusions (GCIs). These observations are the definitive neuropathological diagnostic hallmark of MSA [3]. Such changes induce oligodendroglial degeneration and demyelination, and damages trophic support of glial cells to neurons [4–7]. It has previously been proposed that the oligomeric forms of ɑSyn are more toxic rather than their monomeric and fibrils forms in vivo [8]. However, ɑSyn fibrils injection into rats’ substantia nigra (SN) induces the formation and spread of similar inclusions to that of the oligomeric form and results in dopaminergic neurodegeneration [9]. Moreover, intracellular fibrils seed Lewy body-like inclusions in cultured SH-SY5Y cells [10]. This suggests that ɑSyn oligomeric and fibrotic formation are the primary toxic species in PD and other synucleinopathies.

The mechanism underlying ɑSyn oligomers or fibrils formation remains unclear, although protein misfold and aggregation are triggered by cellular oxidative stress [11]. In addition, cellular exposure to polyunsaturated fatty acids such as arachidonic acid (AA) increases reactive oxygen species (ROS) in ovarian cancer cells [12] and neurons [13]. Fatty acid-binding proteins (FABPs), a family of transporter proteins, bind with high affinity to long-chain fatty acids, bile acids, or retinoids, and have a pivotal role in intracellular lipid trafficking and cell growth [14]. Among them, three species—fatty acid-binding protein 3 (FABP3), fatty acid-binding protein 5 (FABP5), and fatty acid-binding protein 7 (FABP7)—have been identified in rodents’ brains [15]. In the mouse brain, FABP3 is primarily expressed in mature neurons; by contrast, in the developing brain, FABP5 and FABP7 are primarily expressed in radial glial cells and neural stem cells [16]. FABP7 regulates cell proliferation during hippocampal neurogenesis in mice [17]. In the serum and cerebrospinal fluid of patients with neurodegenerative disorders, such as PD, Alzheimer’s disease, and other neurological disorders, previous studies have reported elevated levels of ɑSyn oligomers levels, rather than total ɑSyn [18, 19], while other studies have reported elevated levels of FABP3 and FABP7 [20, 21]. We have previously reported that FABP3 knockout abolished 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP)-induced ɑSyn oligomerization and dopamine neuronal death in mice [22]. Furthermore, FABP3 forms complexes with ɑSyn and AA treatment promotes ɑSyn oligomerization in PC12 [22] and neuron2A cells [23]. FABP3 ligands inhibit ɑSyn oligomerization in neuro2A cells and MPTP-induced parkinsonism mouse brain [24]. Based on this, we hypothesize that FABP7 triggers ɑSyn oligomerization and aggregation in glial cells.

ɑSyn is normally expressed in neurons [25], however, it is abnormally upregulated and aggregated in OLGs. No evidence has yet demonstrated the increase in ɑSyn expression in the MSA brain’s OLGs [25, 26], although in postmortem MSA brain OLGs, ɑSyn messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) levels have been shown to increase approximately threefold [27]. However, the mechanism by which ɑSyn expression is induced in OLGs and whether it is sufficient to trigger ɑSyn aggregation in GCIs remain unclear.

Herein, we investigate how ɑSyn oligomerization, by FABP7, is triggered along with its associated toxicity in the human glioblastoma cell line, U251, the OLG cell line, KG-1C, and oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs) primary culture.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

U251 human glioblastoma cells were purchased from European Collection of Authenticated Cell Cultures (ECACC; Porton Down, Wiltshire, UK). KG-1C human oligodendroglial cells were obtained from RIKEN BRC Cell Bank (Tsukuba, Japan). Both cell types were cultured in Dulbecco’s Minimal Essential Medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), and penicillin/streptomycin (100 U/mL and 100 µg/mL) at 37 °C under 5% carbon dioxide (CO2). The BSA-AA complexes were prepared, as described previously [20]. Transfection was achieved using lipofectamine LTX and Plus Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and Opti-MEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), based on the manufacturer’s protocol.

Animals

Eight-week-old male C57BL/6J mice were obtained from Clea Japan, Inc. (Tokyo, Japan), and housed together in polypropylene cages (temperature: 23 ± 2 °C; humidity: 55% ± 5%; lights on between 9 a.m. and 9 p.m.). All animal experiments were approved by the Committee on Animal Experiments at Tohoku University.

Oligodendrocyte precursor cells culture

OPCs were cultured as previously described [28]. Briefly, P1–2 mouse pups were decapitated and the cortex from brains was dissected and digested in digestion solution [13.6 mL PBS, 0.8 mL DNase I stock solution (0.2 mg/mL) and 0.6 mL trypsin stock solution (0.25%)]. Cells were then diced using a sterilized razor blade into ~1 mm3 chunks, centrifuged at 100 × g for 5 min, and resuspended with DMEM20S medium (DMEM, 4 mM L-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 20% FBS, 50 U/mL penicillin, and 50 µg/mL streptomycin). The tissue suspension was strained using a 70 µm nylon cell strainer and seeded in poly-L-lysine-coated tissue culture flasks and cultured in DMEM20S medium. After 10 days, the flasks were shaken for 1 h at 200 rpm at 37 °C to remove microglial cells, and for an additional 20 h to detach OPCs, and then seeded on poly-D-lysine-coated plates and cultured in OPC medium (DMEM, 4 mM L-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 0.1% BSA, 50 µg/mL Apo-transferrin, 5 µg/mL insulin, 30 nM sodium selenite, 10 nM D-biotin and 10 nM hydrocortisone 10 ng/mL PDGF-AA and 10 ng/mL bFGF).

Plasmid construction and purification

Human αSyn plasmid was purchased from Abgent (San Diego, CA, USA). Plasmid was purified using GenEluteTM HP Plasmid Maxiprep Kit (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), as described previously.

Protein purification

GST-FABP7 was purified using the GST-Tagged Protein Purification Kit (Clontech), according to the manufacturer’s instructions, while His-hFABP7 was purified using the His-Tagged Protein Purification Kit (Clontech), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Cell counting kit assay

Cell viability was measured using cell counting kit (CCK) (Dojindo), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. This assay is based on the clearance of water-soluble tetrazolium salt, WST-8, which is reduced by dehydrogenase activity in cells to create a yellow formazan dye. This dye is soluble in the tissue culture media. Its absorbance by viable cells was measured with a test wavelength of 400 nm and a reference wavelength of 450 nm.

Protein extraction

Cultured cells were frozen using liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C. Collected cells were homogenized with 50 µL Triton X-100 buffer containing 0.5% Triton-X-100, pH 7.4, 4 mM ethylene glycol (EGTA), 50 mM Tris-HCl, 10 mM ethylenediaminetetra-acetic acid (EDTA), 1 mM sodium orthovanadate (Na3VO4), 50 mM sodium fluoride (NaF), 40 mM Na4P2O7·10H2O, 0.15 M sodium chloride (NaCl), 50 µg/mL leupeptin, 25 µg/mL pepstatin A, 50 µg/mL trypsin inhibitor, 100 nM calyculin A, and 1 mM dithiothreitol for each 35 mm dish. Supernatant protein was collected as Triton-soluble fraction and concentrations were normalized using Bradford’s assay. The pellets were homogenized again with 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) buffer and stored at 4 °C (i.e., the SDS-soluble fraction). Samples were mixed with 6× Laemmli’s sample buffer without β-mercaptoethanol and boiling.

Immunoblotting analysis

The extracts (30 µg) were separated by using SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) with a ready-made gel (Cosmo Bio Co., Ltd) and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. The membranes were incubated with primary antibody against αSyn (1:1000; 4B12, GTX21904; GeneTex, Zeeland, MI, USA), FABP7 (1:200; R&D Systems, AF3166), FABP5 (1:200; AF3077; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), ubiquitin (1:1000; MAB1510; Sigma-Aldrich), β-tubulin (1:4000; T0198; Sigma-Aldrich), RIPK1 (1:500; ab72139; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), followed by treatment with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody (SouthernBiotech, Birmingham, AL, USA: 1:5000, anti-mouse [1031–05], anti-rabbit [4050-05]; Rockland Immunochemicals, Pottstown, PA, USA: 1:5000, anti-goat [605–4302]), and following incubation using an ECL detection system (Amersham Biosciences, NJ, USA). Intensity quantification was conducted using Image Gauge software version 3.41 (Fuji Film, Tokyo, Japan).

Immunoprecipitation analysis

Immunoprecipitation analysis was conducted, as described previously [29]. In brief, 50 µL of protein A-Sepharose CL-4B (50%, v/v) was suspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) buffer in a total volume of 500 µL. Cell extracts containing 200 µg of proteins were incubated for 2 h at 4 °C with 10 µg of anti-FABP7 antibody (R&D Systems, AF3166) or 5 µg of anti-αSyn antibody (GTX21904, GeneTex). The mixture was then incubated at 4 °C for 4 h. Samples were separated using SDS-PAGE with a ready-made gel (Cosmo Bio Co., Ltd) and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes.

Immunofluorescent staining

Immunofluorescent staining was conducted, as described previously [30]. The culture cells were grown on 0.01% poly-L-lysine-coated (Sigma) glass slides in 12-well dishes and fixed in 4% PFA overnight at 4 °C. Glass slides were permeabilized using 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 15 min. The cells were then washed and blocked with PBS/1% BSA for three times (10 min each time) and 1 h, respectively. The glass slides were incubated with primary antibodies against αSyn (1:1000, 4B12, GeneTex, GTX21904; 1:1000, Abcam, ab138501), FABP7 (1:200, R&D Systems, AF3166), FABP5 (1:200, R&D Systems, AF3077), in a blocking solution at room temperature overnight. Fluorescein (1:500, Alexa 405-labeled anti-mouse IgG [A-21203], Thermo Fisher Scientific; Alexa 488-labeled anti-goat IgG [A-11055], Thermo Fisher Scientific; Alexa 594-labeled anti-mouse IgG [21203], Thermo Fisher Scientific; Alexa 594-labeled anti-rabbit IgG [A-212017], Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used for detection. Immunofluorescent images were analyzed using a confocal laser scanning microscope (DMi8; Leica, Wetzlar, Germany).

PLA2 activity assay

PLA2 activity assay was conducted using a PLA2 activity assay kit (Bio Vison) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Fluorescence intensity was measured at excitation/emission of 388/513 nm, in kinetic mode for 45 min at 37 °C, using FlexStation 3 Multi-Mode Microplate Reader (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA).

The ANS assay

The ANS assay was conducted as previously described [31, 32]. In this study, 4 µM ANS, 0.4 µM GST-FABP7 and FABPs ligands [23, 33, 34] in concentrations ranging from 0 to 4 µM were mixed in 10 mM potassium dihydrogen phosphate (KH2PO4)/40 mM potassium chloride buffer. Two minutes following incubation at 25 °C, the fluorescence intensity was measured at excitation/emission of 355/460 nm using FlexStation 3 Multi-Mode Microplate Reader (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA).

Quartz crystal microbalance (QCM) assay

The QCM assay was conducted as previously described [35]. In this study, QCM (Affinix QN µ, ULVAC, Kanagawa, Japan) was used to directly detect interactions between His-hFABP7 and α-synuclein. The sensor cell was initialized using 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate and piranha solution (H2SO4:H2O2 = 3:1), and the interactions between His-hFABP7 and ligand or α-synuclein were detected using the NTA/Ni2+ approach. Following equilibration of the sensor cell with Tris buffer (25 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.7 at 25 °C), His-hFABP7 was added; after the removal of unbound His-hFABP7 and frequency stabilization, α-synuclein or ligand was added and measured. Between sample measurements, the sensor cell was incubated and washed with imidazole buffer (0.4 M imidazole, 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), and 150 mM NaCl) for 20 min. Importantly, for determining ligand 6’s ability to block the FABP7-ɑSyn interaction, ligand 6 (1000 nM) was initially added to sensor cell, and after it has fully bound to His-hFABP7 (frequency stabilization), sensor cell was washed 3 times with Tris buffer (25 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.7 at 25 °C). Then, ɑSyn was added in various concentrations. AQUA analysis software version 2.0 (ULVAC, Kanagawa, Japan) was used to calculate Kd values.

Thioflavin-T (ThT) fluorescence assays

α-Synuclein samples (1 mg/mL) were incubated with or without His-hFABP7 and ligand 6 at 37 °C in 25 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4 at 37 °C) containing 150 mM NaCl and 10 µM ThT (FUJIFILM). Each plate (200 mL) was incubated at 37 °C and was measured at 15 min intervals in kinetic mode for 1500 min with FlexStation 3 Multi-Mode Microplate Reader (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA). The fluorescence was excited at 450 nm and detected at 486 nm.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical comparisons were evaluated using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, as required. A value of P < 0.05 was statistically significant.

Results

Fatty acid-binding protein 7 forms a complex and colocalizes with ɑSyn in U251 cells

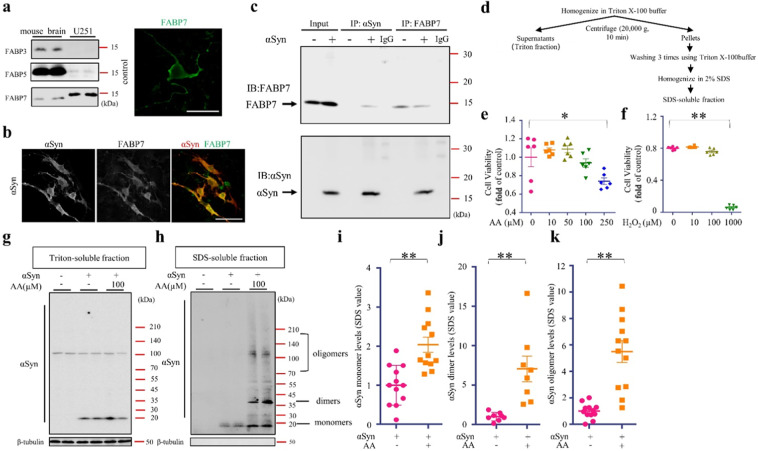

We have previously demonstrated that FABP3 forms complexes with ɑSyn in the SN of mice [22]. To confirm the interaction of FABP7 and ɑSyn in glial cells, we overexpressed ɑSyn in U251 cells, which express endogenous FABP7 in high levels (Fig. 1a). We found that FABP7 and ɑSyn were double-stained in ɑSyn-overexpressed U251 cells showing FABP7/αSyn-double positivity (Fig. 1b). Furthermore, we then conducted immunoprecipitation of the U251 cell extracts using an ɑSyn antibody, followed by immunoblotting with anti-FABP7 antibody and found that the immunoreactive FABP7 was bond to the extracts ɑSyn-transfected U251 cells (Fig. 1c). After conducting FABP7 immunoprecipitation from U251 cell extracts, the immunocomplexes were immunoblotted with an anti-ɑSyn antibody (Fig. 1c), where we observed FABP7–ɑSyn complex in ɑSyn-overexpressed U251 cells (Fig. 1c).

Fig. 1. FABP7 forms a complex and colocalizes with αSyn and AA induces αSyn oligomerization in αSyn-transfected U251 cells.

a Western blot (WB) analysis of FABP7 in mouse brain and U251 cells. The U251 cells express endogenous FABP7. b Confocal images show the colocalization of FABP7 (green) and αSyn (red) in U251 cells. FABP7 is co-localized with αSyn in the cytoplasm (scale bar, 50 µm). c Co-immunoprecipitation of FABP7 and αSyn U251 cell extracts. Extracts were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-FABP7 or anti-αSyn antibody. The immunoprecipitates were then immunoblotted (IB) with anti-FABP7 antibody (top) or with anti-αSyn (bottom) antibody. As the control, FABP7 and αSyn immunoreactive bands, cell extracts (Input) are shown on the left. d Scheme of the αSyn extraction procedure. e, f Cell viability analysis of U251 cells, based on a CCK assay. Cells cultured treated with AA and H2O2 at concentrations of 250 and 1000 µM, respectively, for 24 h significantly induced cell death (n = 6). g, h Western blot analysis showed that 48-h incubation with AA (100 µM) induces αSyn oligomerization in SDS-soluble fractions. i Quantification of αSyn monomers in SDS-soluble fractions, based on WB analysis, is illustrated. The αSyn monomers are significantly increased in AA-treated cells (n > 8). j Quantification of αSyn dimers in SDS-soluble fractions, based on WB analysis, is illustrated. The αSyn dimers are significantly increased in AA-treated cells (n > 8). k Quantification of αSyn oligomers in SDS-soluble fractions, based on WB analysis, is illustrated. The αSyn oligomers are significantly increased in AA-treated cells (n > 8). The data are presented as the mean ± the standard error of the mean, and were obtained using and one-way analysis of variance. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01. αSyn alpha-synuclein, AA arachidonic acid, CCK cell counting kit-8, FABP7 fatty acid-binding protein 7, H202 hydrogen peroxide, WB Western blot.

Arachidonic acid induced αSyn oligomerization in U251 cells

We, and other previous studies [23, 36] have reported that AA promotes αSyn oligomerization in cultured neuronal cells. However, whether ɑSyn oligomerization can be induced in glial cells remains unclear. Since ɑSyn protein expression in glial cells is low, we have overexpressed it in U251 cells to mimic MSA pathology. We first overexpressed ɑSyn in U251 cells, unlike to neuro2A cells overexpressing αSyn [23], αSyn could not be solubilized in Triton X-100. The insoluble αSyn was solubilized in sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) buffer [37, 38]. Thus, in the present study, the Triton X-100-insoluble fractions were solubilized in 2% SDS buffer (Fig. 1d). To induce oxidative stress, U251 cells were treated with 100 µM AA or 100 µM hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). We confirmed that these treatments do not affect the cell survival (Fig. 1e, f). Following treatment with 100 µM AA for 48 h, no significant increase in the oligomers was observed in the Triton-soluble fractions (Fig. 1g). However, the formation of ɑSyn dimers or trimers of 35–55 kDa and oligomers of 70–140 kDa were significantly elevated in the SDS-soluble fractions (Fig. 1h). As we expected, AA treatment significantly promoted αSyn dimer/trimer and oligomer formation in SDS-soluble fractions (P < 0.01) (Fig. 1j, k). Unexpectedly, AA treatment also increased αSyn monomer levels in SDS-soluble fractions (P < 0.01) (Fig. 1i). The monomer levels were unchanged in the Triton X-100 fraction; therefore, the elevated monomer levels in SDS-soluble fraction were monomers dissociated from oligomer fractions during SDS preparation. Taken together, AA promoted ɑSyn dimer/trimer and oligomer formation in U251 cells.

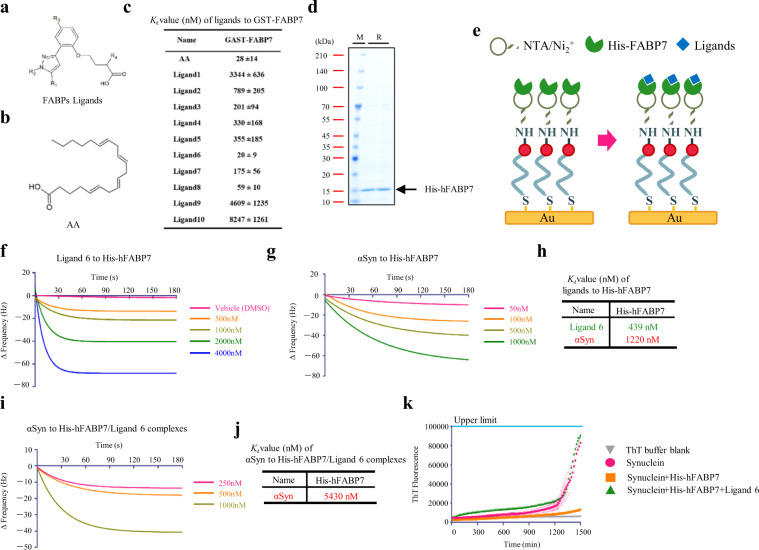

Selection of synthetic FABP7 ligands

Our findings suggested that FABP7 forms complexes with ɑSyn in U251 cells and that FABP7 may participate in ɑSyn dimer/trimer and oligomer formation in U251 cells. Therefore, we developed FABP7-specific ligands, using ANS assay (structures had been described previously [23]). Among these ligands (Fig. 2a, b), ligand 6 (Kd = 20 ± 9) appeared to have the highest affinity against GST-FABP7 and the affinity was comparable for AA (Kd = 28 ± 14 nM) against GST-FABP7. In addition, ligand 8 (Kd = 59 ± 10) may also have high affinity against GST-FABP7 (Fig. 2c). Meanwhile, we also measured the affinity between ɑSyn and His-hFABP7 (Fig. 2d) using QCM assay (Fig. 2e). In this assay, ligand 6 (Kd = 439 nM) showed much higher affinity with His-hFABP7 than that of ɑSyn (Kd = 1220 nM) (Fig. 2f–h).

Fig. 2. In vitro evaluation of FABP7 ligands in disrupting αSyn/FABP7 interaction.

a Chemical structures of the FABPs ligands. b Chemical structure of the FABP7 endogenous ligand, arachidonic acid (AA). c The Kd value of FABPs ligand, measured with an ANS assay. d Coomassie brilliant blue (CBB) stain of His-hFABP7. e Schematic diagram of QCM assay. f, g Binding of ligand 6 (f) or αSyn (g) to immobilized His-hFABP7. Changes in frequency of the His-hFABP7-immobilized QCM sensor upon addition of various concentrations of ligands. h The Kd value of ligand 6 and αSyn. i binding of αSyn to immobilized His-hFABP7/ligand 6 complexes. j the Kd value of αSyn to His-hFABP7/ligand 6 complexes. k Thioflavin-T (ThT) fluorescence changes upon incubation of αSyn in the absence (pink) and presence of a onefold (orange) concentration of His-hFABP7 or with ligand 6 (green). ANS assay. ANS 8-anilinonaphthalene-1-sulfonic acid, FABPs fatty acid-binding proteins, FABP3 fatty acid-binding protein 3, FABP7 fatty acid-binding protein 7. M marker, R recombinant protein.

Synthetic FABP7 ligands disrupt the αSyn–FABP7 interaction in vitro

Based on the higher affinity of ligand 6 with His-hFABP7, we investigated whether ligand 6 can disrupt the FABP7–αSyn interaction in vitro using QCM assay. Herein, ligand 6 was added firstly to bind to His-hFABP7 thus forming ligand 6/His-hFABP7 complex, followed by ɑSyn addition. We found that ɑSyn had a low affinity (Kd = 5430 nM) to ligand 6/His-hFABP7 complex (Fig. 2i, j), indicating that ligand 6 can indeed disrupt the FABP7–αSyn interaction. For further evaluation, we conducted ThT Fluorescence Assays; ThT emits a strong fluorescence when bound to β-sheets in amyloid fibrils. ɑSyn was incubated at 37 °C to form fibrils, which resulted in a 1:1 molar ratio of His-hFABP7 to αSyn; the final ThT fluorescence intensity was significantly decreased. However, when treating the incubation buffer with ligand 6, His-hFABP7 is completely blocked causing the fluorescence signal not to be suppressed (Fig. 2k).

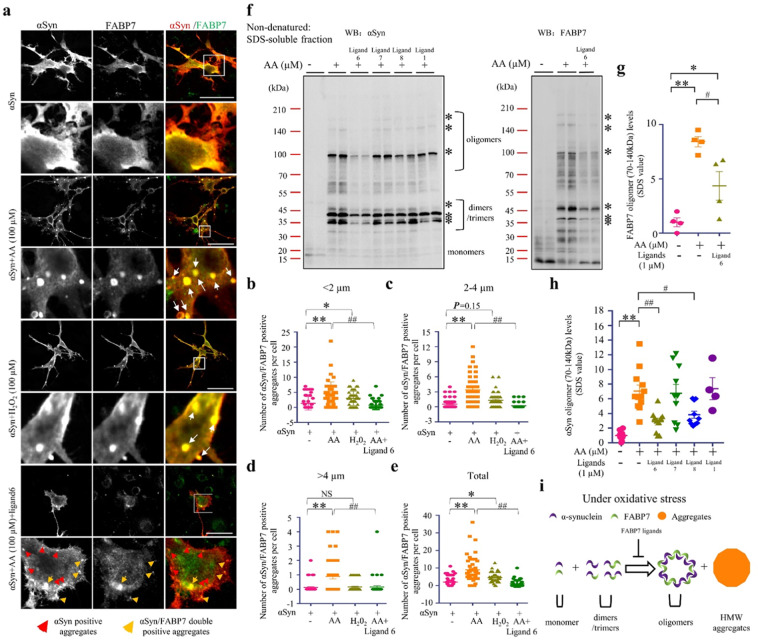

Synthetic FABP7 ligands inhibit FABP7-dependent αSyn oligomerization and aggregation

When ɑSyn was overexpressed in U251 cells, ɑSyn and FABP7 were expressed in the cytoplasm. The overexpressed ɑSyn was co-localized with FABP7 without aggregation in the vehicle group (Fig. 3a). By contrast, numerous ɑSyn- and FABP7-positive aggregates were in the cytoplasm following treatment with AA or H2O2 in U251 cells (Fig. 3a). When we classified the aggregates as “small” (<2 µm), “middle” (2–4 µm), or “large” (>4 µm), and quantified the number of aggregates of each cell, we found that the number of small aggregates was significantly increased with AA treatment (P < 0.01) and with H2O2 treatment (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3b). However, AA treatment significantly increased the number of middle and large aggregates (P < 0.01) (Fig. 3c, d). Thus, the aggregates were significantly increased with AA treatment (P < 0.01) or H2O2 treatment (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3e). Interestingly, in the FABP7 ligand 6-treated cells, we observed a significant reduction of ɑSyn/FABP7 double-positive aggregation (P < 0.01) and found numerous ɑSyn single-positive small aggregates (<2 µm) (Fig. 3a). FABP7 ligand 6 may have partially blocked FABP7/ɑSyn interaction and inhibited the formation of ɑSyn/FABP7 double-positive large aggregates. On the other hand, we also evaluated the effects of FABP7 ligands on αSyn oligomerization induced by AA. Ligands 6 and 8 significantly reduced the formation of αSyn oligomers (70–140 kDa) induced by AA (P < 0.01). However, ligand 1, which has been reported as an FABP3 inhibitor [23], had no effects on αSyn oligomer formation in U251 cells (Fig. 3f). After stripping the αSyn antibody, we incubated the same membrane with FABP7 antibody. Western blotting showed that FABP7 forms a heterodimer or trimer with αSyn. In addition, with AA treatment, FABP7 formed oligomers with a high molecular weight (P < 0.01). When summarizing the quantification, FABP7 oligomers weighing 70–140 kDa significantly decreased following treatment with ligands 6 (P < 0.01) (Fig. 3g). Taken together, FABP7 was included in the ɑSyn aggregates and oligomers under oxidative stress such as AA or H2O2 treatment, and FABP7 ligand 6 inhibited FABP7 participation in the ɑSyn aggregation and oligomerization (Fig. 3i).

Fig. 3. Synthetic FABP7 ligands reduce αSyn oligomerization and aggregation.

a Confocal microscopy of immunofluorescence staining of αSyn (red) and FABP7 (green) in U251 cells. The αSyn-overexpressed U251 cells were incubated with the vehicle, AA (100 µM), and H2O2 (100 µM), for 48 h. The FABP7-positive and αSyn-positive aggregates in AA- and H2O2-treated cells were increased. In addition, ligand 6 disrupted the FABP7/αSyn interaction and decreased the number of FABP7-/αSyn-positive aggregates in each cell. b–e Quantification of FABP7- and αSyn-positive aggregates in U251 cells, based on immunofluorescent staining, is illustrated. Small aggregates (<2 µm) were significantly increased in the AA-treated cells (n = 48) and H2O2-treated cells (n = 43), and normal sized aggregates (2–4 µm) and large aggregates (>4 µm) are significantly increased only in the AA-treated cells (n = 48). Ligand 6 treatment significantly decreased FABP7-/αSyn-positive aggregates in each size (n = 44). The data are shown as mean ± standard error of the mean and were obtained using one-way analysis of variance. The scale bar represents 50 µm. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ##P < 0.01. f Western blot (WB) analysis of αSyn (left) and FABP7 (right) reveals that 48 h incubation with FABP7 ligand 6 and ligand 8 significantly reduced the formation of αSyn oligomers weighing 70–140 kDa. g, h Quantification of αSyn (h) and FABP7 (g) oligomers in SDS-soluble fractions, based on WB analysis, is illustrated. FABP7 ligand 6 (n = 10) and ligand 8 (n = 10) significantly reduced αSyn oligomerization, and ligand 1 (n = 4) fails to inhibit αSyn oligomerization (left). Ligand 6 (n = 4) also disrupts FABP7-αSyn interaction and significantly reduced FABP7 oligomerization (right). i Schematic draft of FABP7 ligands inhibition of αSyn oligomerization. The data are shown as mean ± standard error of the mean and were obtained using one-way analysis of variance. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; #P < 0.05; ##P < 0.01. αSyn alpha-synuclein, AA arachidonic acid, FABP7 fatty acid-binding protein 7, H202 hydrogen peroxide, NS not statistically significant.

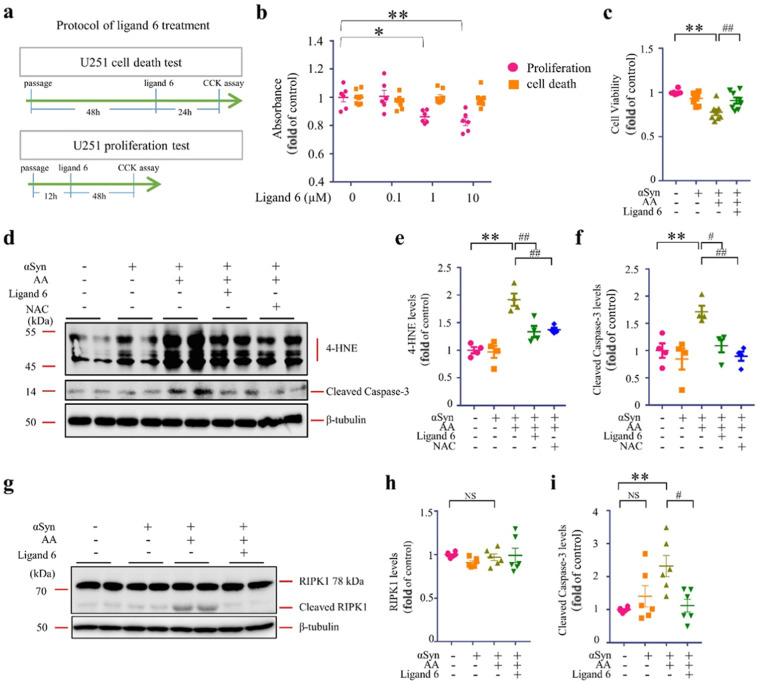

Synthetic FABP7 ligands improved U251 cell survival

Since FABP7 ligand 6 inhibited αSyn oligomerization/aggregation and partly rescued from cell deah, FABP7 ligand 6 may improve cell survival by inhibiting αSyn oligomer toxicity. We firstly measured the effects of Ligand 6 on cell viability and proliferation using two different culture protocols (Fig. 4a). As results, we observed no significant toxicity in ligand 6-treated U251 cells even at high concentration (10 μM). However, unfortunately, ligand 6 markedly interfered the proliferation of U251 cells at the concentration of 1 μM (P < 0.01) due to FABP7 inhibition (Fig. 4b). Despite the inhibition effect in proliferation of ligand 6 in high concentration, we also observed the increased cell viability in ligand 6-treated cells (P < 0.01) (Fig. 4c). We next analyzed with oxidative stress marker, 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE), cell apoptosis marker, cleaved caspase-3, and cell necroptosis marker receptor-interacting protein kinase 1 (RIPK1) [39]. The 4-HNE levels decreased in ligand 6-treated cells (P < 0.01) (Fig. 4d, e). More importantly, the cleaved caspase-3 levels increased in AA/αSyn treated cells (P < 0.01) and ligand 6 treatment significantly inhibited the apoptosis pathway (P < 0.01) (Fig. 4f). However, the total RIPK1 levels were unchanged after AA treatment (Fig. 4g, h). Whereas the cleaved RIPK1 levels increased after αSyn overexpression with AA treatment (P < 0.01) and ligand 6 treatment significantly decreased the cleaved RIPK1 levels at the concentration of 1 µM (P < 0.01) (Fig. 4i). Taken together, ligand 6 also elicits an antioxidant and inhibitory effect in cell death, especially in the apoptosis progress induced by αSyn oligomers.

Fig. 4. Synthetic FABP7 ligands improve U251 cell survival.

a Experimental protocol of cell death test and proliferation test. b Cell viability analysis of U251 cells in cell death and proliferation, U251 cells were treated with ligand 6 in various concentration (0, 0.1, 1, 10 μΜ). c Cell viability analysis of U251 cells, based on CCK assay. d Western blot (WB) analysis against anti-4HNE and cleaved caspase-3 reveals that ligand 6 (1 µM) and antioxidant, NAC (1 µM), treatment for 48 h reduces oxidative stress levels, and apoptosis triggered by AA (100 µM) in αSyn-overexpressing U251 cells. e Quantification of 4-HNE in Triton-soluble fractions, based on WB analysis, is illustrated (n = 4). f Quantification of cleaved caspase-3 in Triton-soluble fractions, based on WB analysis, is illustrated (n = 4). g Western blot (WB) analysis against anti-RIPK1 reveals that ligand 6 treatment for 48 h reduces RIPK1 cleaving triggered by AA (100 µM) in αSyn-overexpressing U251 cells. h The quantification of total RIPK1 in Triton-soluble fractions, based on WB analysis, is illustrated (n = 6). i The quantification of cleaved RIPK1 in Triton-soluble fractions, based on WB analysis, is illustrated (n = 6). The data are shown as mean ± standard error of the mean and were obtained using one-way analysis of variance. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; #P < 0.05; ##P < 0.01. αSyn alpha-synuclein, AA arachidonic acid, NS not statistically significant, NAC N-acetyl-L-cysteine, 4-HNE 4-Hydroxynonenal, RIPK1, receptor-interacting protein kinase 1.

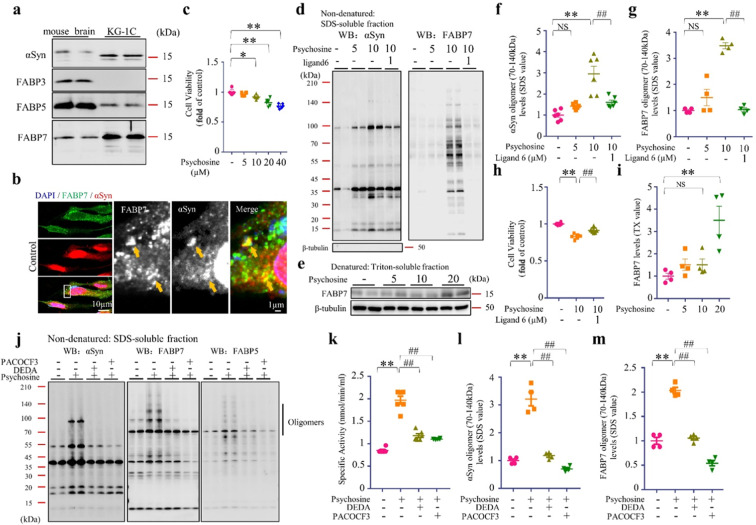

Psychosine exacerbated FABP7-dependent αSyn oligomerization and cell death in KG-1C human oligodendroglial cells

Investigating the effect of endogenous AA production on αSyn oligomerization and toxicity is critical. We used KG-1C human oligodendroglial cells and psychosine [40] to produce AA by activating endogenous PLA2. FABP7 and FABP5 were predominantly expressed in KG-1C cells (Fig. 5a). FABP7 normally colocalizes with αSyn (Fig. 5b). To treat cells with the PLA2 agonist psychosine, we first assessed psychosine toxicity on KG-1C cells (Fig. 5c). The 48-h treatment with 5 µM psychosine did not affect cell viability yet induced the oligomerization of endogenous αSyn in KG-1C cells. Moreover, psychosine treatment with 10 µM significantly enhanced oligomerization in endogenous αSyn and FABP7 (P < 0.01) (Fig. 5d), The psychosine effects were more pronounced in FABP7 oligomerization. FABP7 ligand 6 significantly inhibited the oligomerization of both αSyn and FABP7 (P < 0.01) (Fig. 5d, f, g) and improved cell viability (Fig. 5h). In addition, we also noticed an increased level of endogenous FABP7 in Triton-soluble fractions post-psychosine treatment (Fig. 5e, i). On the other hand, we further investigated whether psychosine can activate PLA2 in KG-1C cells using PLA2 activity assay. Our results showed that psychosine significantly enhanced the PLA2 activity in KG-1C cells (P < 0.01), which was inhibited by two potent PLA2 inhibitors, PACOCF3 (P < 0.01) and DEDA (P < 0.01) (Fig. 5k). Moreover, PACOCF3 and DEDA also blocked psychosine-mediated PLA2 activation and inhibited αSyn and FABP7 oligomerization (Fig. 5j, l, m). In conclusion, PLA2 activation by psychosine triggered oligomerization of endogenous αSyn and FABP7 in OLGs. As for the induction of FABP7, the oligomer was more pronounced in OLGs, while ligand 6 significantly inhibited the oligomerization of αSyn and FABP7 and the formation of αSyn/FABP7 heterocomplexes in OLGs.

Fig. 5. Functions of FABP7 in OLGs.

a Western blot (WB) analysis of FABP3, FABP5, FABP7, and αSyn in the mouse brain and in KG-1C human oligodendroglial cells. The KG-1C cells endogenously express αSyn, FABP5, and FABP7. b Confocal microscopy of immunofluorescence staining for αSyn (red) and FABP7 (green) in KG-1C cells. In normal condition, FABP7 colocalizes with αSyn. c Cell viability analysis of KG-1C cells, based on CCK assay. Cells were cultured with psychosine for 24 h. Induced cell death was observed at a concentration of 10 µM (n = 6). d WB analysis of SDS-soluble fractions against αSyn (left) and FABP7 (right) reveals that 48-h incubation with FABP7 ligand 6 (1 µM) significantly reduced αSyn oligomer formation induced by psychosine (10 µM) in KG-1C cells. e WB analysis of Triton-soluble fractions against FABP7. f, g Quantification of αSyn and FABP7 oligomers in SDS-soluble fractions, based on WB analysis, is illustrated. FABP7 ligand 6 significantly reduced αSyn oligomer (n = 6) and FABP7 oligomer formation (n = 4). h Cell viability analysis of KG-1C cells, based on CCK assay. Cells were treated with ligand 6 (1 µM) which significantly improved KG-1C survival (n = 6). i Quantification of FABP7 monomer in Triton-soluble fractions, based on WB analysis, is illustrated. Endogenous FABP7 was significantly increased in the psychosine (20 µM) treatment group (n = 4). j Western blot (WB) analysis of αSyn, FABP7, and FABP5 showed that incubation with psychosine significantly enhanced αSyn formation, and treatment with PLA2 inhibitor blocked this effect (n = 4). k PLA2 activities of KG-1C cells following psychosine treatment (10 µM), with and without PLA2 inhibitors (10 µM) using PLA2 activity assay (n = 4). l, m The quantification of αSyn and FABP7 oligomers in SDS-soluble fractions, based on WB analysis, is illustrated. The data are shown as mean ± standard error of the mean and were obtained using one-way analysis of variance. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; #P < 0.05; ##P < 0.01. ɑSyn alpha-synuclein, CCK cell counting kit-8, FABP3, 5, and 7 fatty acid-binding protein 3, 5, and 7, NS not statistically significant, SDS sodium dodecyl sulfate.

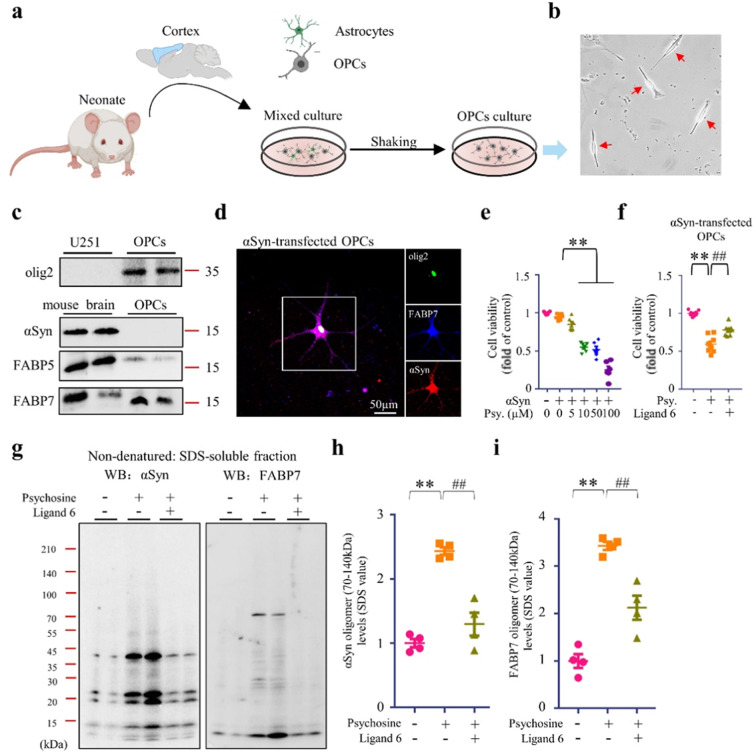

Synthetic FABP7 ligand inhibited αSyn oligomerization in oligodendrocyte precursor cells

We further investigated our hypothesis using OPCs primary culture (Fig. 6a, b). In this study, we found that OPCs expressed endogenous FABP7 and FABP5 but no endogenous αSyn was observed (Fig. 6c). To evaluate the relationship between αSyn and FABP7 we overexpressed αSyn in OPCs (Fig. 6d). Following psychosine treatment, OPCs death rate was significantly high at concentrations of 10, 50, and 100 µM (Fig. 6e). However, ligand 6 significantly improved OPCs survival (Fig. 6f). Meanwhile, consistent with our result in U251 and KG-1C cells, we also found that αSyn and FABP7 formed oligomers upon psychosine treatment, and that ligand 6 inhibited their interaction and oligomerization (Fig. 6g–i).

Fig. 6. FABP7 and αSyn interaction in OPCs primary culture.

a Schematic draft of OPCs primary culture protocol. b Microscopic image of OPCs (red arrows). c Western blot (WB) analysis of FABP5, FABP7, and αSyn in the U251 cells, mouse brain and in OPCs. d Confocal microscopy of immunofluorescence staining of olig2 (green), αSyn (red) and FABP7 (blue) in OPCs. e, f Cell viability analysis of OPCs, based on CCK assay. OPCs overexpressing αSyn, were treated with psychosine at various concentrations in the absence (e) (n = 6) or presence (f) (n = 8) of ligand 6. g WB analysis of FABP7 and αSyn in OPCs. OPCs, overexpressing αSyn, were treated with psychosine (10 µM) in the absence or presence of ligand 6 (1 µM). h, i Quantification of αSyn (h) and FABP7 (i) oligomers in SDS-soluble fractions, based on WB analysis, is illustrated. The data are shown as the mean ± standard error of the mean and were obtained using one-way analysis of variance. **P < 0.01 and ##P < 0.01. ɑSyn alpha-synuclein, FABP3, 5, and 7 fatty acid-binding protein 3, 5, and 7, Psy Psychosine.

Discussion

Our primary aim was to determine whether FABP7 interacts with αSyn forming αSyn oligomers in OLGs. We determined whether novel FABP7 ligands inhibit αSyn oligomerization and mitigate its associated toxicity. We used U251 human glioblastoma cells expressing FABP7 and KG-1C human oligodendroglial cells that endogenously express αSyn and FABP7 as well as OPCs primary culture.

In vitro, we verified the close interaction between recombinant human-αSyn and His-hFABP7 by QCM assay. Since we observed the dramatical changes of frequency when we treated human-αSyn into His-hFABP7 bound sensor cell, it indicated the direct binding and interaction between the two proteins. And consistently, in U251 cells, the result of immunoprecipitation analysis furthermore supported this finding. What’s more, the immunoblotting analyses also revealed heterodimer or hetero-trimer formation of αSyn and FABP7, which suggested that αSyn forms homo-oligomers and hetero-oligomers with FABP7 in glial cells. In KG-1C cells, αSyn similarly forms heterocomplexes with FABP7, following endogenous PLA2 activation. The molecular mass of the hetero-oligomer with αSyn/FABP7 was similar between U251 and KG-1C cells. In this context, FABP7 was a major causative FABP isoform that interacted with αSyn in glial cells.

In U251 cells, AA-induced αSyn oligomers were recovered in the SDS fractions. By contrast, these oligomers are recovered in Triton X-100 fractions in neuro2A cells [23], which suggested that αSyn oligomers are associated with cytoskeletal components. In particular, AA treatment resulted in the formation of large αSyn aggregate particles in U251 cells, compared to neuro2A cells. Conversely, in the brains of patients with MSA, αSyn in GCI fraction was similarly resistant to solubilization in high salt buffer [41]. The solubilization of αSyn is dependent on the size of aggregated particles and inclusion bodies. SDS-soluble αSyn oligomers or aggregates formed with FABP7 have similar properties as those of GCIs in glial cells.

The oligomer form of αSyn is more toxic compared with its monomer form, due to increase in solubility; lipid-dependent αSyn oligomers were observed in αSyn transgenic mice and PD and DLB patient brains compared to controls [36]. Meanwhile, αSyn fibrils promoted oligomerization in rats’ brain causing a more severe dopaminergic loss [8] while mutation of αSyn PD-linked A53T and A30P also accelerated oligomerization but not fibrilization [42]. Meanwhile, recent studies have also suggested that αSyn fibrils were 1000-fold more toxic than their precursors and that fibrils, rather than ribbons or oligomers, injection into rats’ substantia nigra pars compacta induced the greatest motor impairment and dopaminergic cell loss [43]. Injection of brain extracts from patients with MSA into transgenic mice induced neurodegeneration, suggesting that MSA-derived strains of αSyn might be more toxic [44]. αSyn strains of different structures have different toxicity levels. In the present study, we found that FABP7 formed complexes with αSyn and induced αSyn oligomerization in glial cells and OLGs and that large size oligomers, having αSyn/FABP7, were formed in αSyn-overexpressed U251 cells. To assess the toxicity levels of αSyn/FABP7 complexes, we develop FABP7 ligand 6 which disrupted the interaction between αSyn and FABP7. The inhibition of FABP7 by ligand 6 significantly reduced αSyn oligomerization and aggregation and inhibited glial cell death. Evidence proving the critical role of FABP7 in ɑSyn oligomerization and aggregation in MSA pathogenesis remains limited. FABP7 binds to ɑSyn and triggers ɑSyn oligomerization and aggregation in glial cells and OLGs.

In KG-1C cells, we found that endogenous FABP7 was co-localized with endogenous αSyn, whereas the AA or psychosine treatment did not trigger the formation of αSyn aggregates with a high molecular weight in KG-1C cells. This may be attributed to the low levels of endogenous αSyn in KG-1C cells not being sufficient to form αSyn aggregates as observed in αSyn-overexpressing U251 cells. Additionally, in OPCs primary culture, we found no endogenous αSyn expressed. Since αSyn is expressed almost exclusively in neurons, the origin of αSyn that composes GCIs in OLGs remains enigmatic. As described previously, in patients with MSA, ɑSyn mRNA levels are approximately threefold higher in OLGs but decreased approximately two-fold in neurons [27]. Furthermore, neuronal secretion of αSyn underlies its pathogenic accumulation in OLGs in A53T αSyn transgenic mice [45]. Moreover, ɑSyn accumulation in neurons is transmitted to OLGs causing GCIs in AAV-hua-syn-injected rats [46]. Thus, neuronal αSyn transferred to OLGs facilitates our understanding of how MSA begins and progresses. Previous reports have suggested that FABP7 controlled lipid raft function by regulating caveolin-1 expression in astrocyte [47], therefore FABP7 might also influence the regulation of ɑSyn neuron for OLGs propagation. This warrant further investigation using MSA model mice.

To elicit the pathological significance of AA production through PLA2 activation in αSyn oligomerization, psychosine [40] was used in KG-1C cells. Consistent with the previous report [40], we also identified that psychosine significantly activated PLA2 activities and induced prominent ɑSyn aggregation. Besides, psychosine accumulation in OLGs is attributed to the lysosomal enzyme galactosyl-ceramidase (GALC) mutation, which causes degeneration of white matter in the central nervous system [48]. Genome-wide association studies has recently identified that GALC as another risk factor for PD [49]. Psychosine forms hydrophilic clusters and binds the C-terminus of αSyn resulting in the accumulation of αSyn oligomers [50]. In the present study, PLA2 activities were significantly increased following psychosine treatment. Additionally, the oligomerization of FABP7 and αSyn was significantly enhanced in KG-1C cells and OPCs primary culture with the same concentration of psychosine.

Since the glial cell-derived FABP7 also exhibited the protective effect on blood–brain barrier integrity toward brain injury [51], the abnormal accumulation of ɑSyn interacted with FABP7 in glial cells may trigger the elevation of ROS levels thereby accelerating the pathological process of various neurodegeneration disease [52, 53]. Consistently, in the present study, AA treatment in αSyn-overexpressed U251 cells also triggered the upregulation of ROS levels. Most importantly, ligand 6 played a role as an antioxidant and eliminated ROS in cellular levels. Ligand 6 may exhibits the potnecy of neurovascular protection via targeting oxidative stress [54].

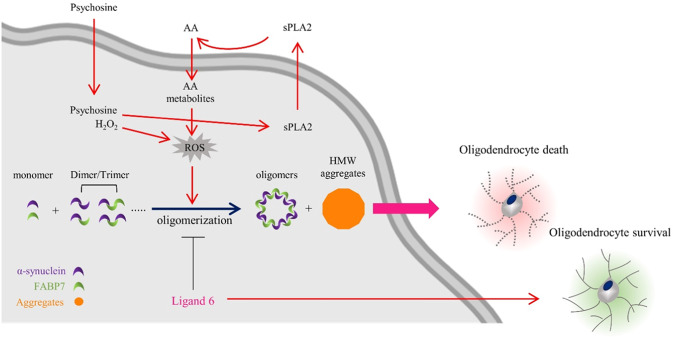

In summary, αSyn forms homo-oligomers or hetero-oligomers with FABP7 in OLGs under oxidative stress induced by psychosine or H2O2. AA can induce αSyn homo-oligomers or hetero-oligomers, while FABP7 ligand 6 inhibits the formation of homo-oligomers and hetero-oligomers by disrupting the interaction between αSyn and FABP7 (Fig. 7). Thus, FABP7 ligand 6 is a possible therapeutic candidate for treating α-synucleinopathies in glial cells and OLGs.

Fig. 7. Schematic representation of the pathways through which FABP7 triggers αSyn oligomerization associated with oxidative stress and induces oligodendrocyte loss.

During a pathological condition, such as reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation induced by hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) or the psychosine induced arachidonic acid (AA) accumulation, endogenous alpha-synuclein (αSyn), and fatty acid-binding protein 7 (FABP7) interact with each other and form FABP7-positive oligomers. This process may result in oligodendrocyte loss. In addition, ligand 6 disrupted the FABP7–αSyn interaction and inhibited αSyn oligomerization, thereby improving OLGs survival.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully thank The Uehara Memorial Foundation for financial support. This work was supported in part by the Strategic Research Program for Brain Sciences from Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (JP17dm0107071, JP18dm0107071, JP19dm0107071, and JP20dm0107071; awarded to KF).

Author contributions

AC, investigation and original draft writing; YS, investigation; YFW, investigation; IK, investigation and methodology; TY, methodology and validation; WBJ, methodology and validation; HY, methodology; TM, methodology; YK, methodology and validation; KF, supervision, review/editing, project administration and funding.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Roncevic D, Palma JA, Martinez J, Goulding N, Norcliffe-Kaufmann L, Kaufmann H. Cerebellar and parkinsonian phenotypes in multiple system atrophy: similarities, differences and survival. J Neural Transm. 2014;121:507–12. doi: 10.1007/s00702-013-1133-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spillantini MG, Schmidt ML, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ, Jakes R, Goedert M. Alpha-synuclein in Lewy bodies. Nature. 1997;388:839–40. doi: 10.1038/42166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palma JA, Norcliffe-Kaufmann L, Kaufmann H. Diagnosis of multiple system atrophy. Auton Neurosci. 2018;211:15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2017.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ettle B, Kerman BE, Valera E, Gillmann C, Schlachetzki JC, Reiprich S, et al. α-Synuclein-induced myelination deficit defines a novel interventional target for multiple system atrophy. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;132:59–75. doi: 10.1007/s00401-016-1572-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stefanova N, Bücke P, Duerr S, Wenning GK. Multiple system atrophy: an update. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:1172–8. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70288-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ubhi K, Low P, Masliah E. Multiple system atrophy: a clinical and neuropathological perspective. Trends Neurosci. 2011;34:581–90. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wong JH, Halliday GM, Kim WS. Exploring myelin dysfunction in multiple system atrophy. Exp Neurobiol. 2014;23:337–44. doi: 10.5607/en.2014.23.4.337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Winner B, Jappelli R, Maji SK, Desplats PA, Boyer L, Aigner S, et al. In vivo demonstration that alpha-synuclein oligomers are toxic. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:4194–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100976108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abdelmotilib H, Maltbie T, Delic V, Liu Z, Hu X, Fraser KB, et al. α-Synuclein fibril-induced inclusion spread in rats and mice correlates with dopaminergic neurodegeneration. Neurobiol Dis. 2017;105:84–98. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2017.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luk KC, Song C, O’Brien P, Stieber A, Branch JR, Brunden KR, et al. Exogenous alpha-synuclein fibrils seed the formation of Lewy body-like intracellular inclusions in cultured cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:20051–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908005106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Islam MT. Oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction-linked neurodegenerative disorders. Neurol Res. 2017;39:73–82. doi: 10.1080/01616412.2016.1251711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tanaka A, Yamamoto A, Murota K, Tsujiuchi T, Iwamori M, Fukushima N. Polyunsaturated fatty acids induce ovarian cancer cell death through ROS-dependent MAP kinase activation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;493:468–73. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.08.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.García-Krauss A, Ferrada L, Astuya A, Salazar K, Cisternas P, Martínez F, et al. Dehydroascorbic acid promotes cell death in neurons under oxidative stress: a protective role for astrocytes. Mol Neurobiol. 2016;53:5847–63. doi: 10.1007/s12035-015-9497-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Besnard P, Niot I, Poirier H, Clément L, Bernard A. New insights into the fatty acid-binding protein (FABP) family in the small intestine. Mol Cell Biochem. 2002;239:139–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Owada Y. Fatty acid binding protein: localization and functional significance in the brain. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2008;214:213–20. doi: 10.1620/tjem.214.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Owada Y, Yoshimoto T, Kondo H. Spatio-temporally differential expression of genes for three members of fatty acid binding proteins in developing and mature rat brains. J Chem Neuroanat. 1996;12:113–22. doi: 10.1016/s0891-0618(96)00192-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsumata M, Sakayori N, Maekawa M, Owada Y, Yoshikawa T, Osumi N. The effects of Fabp7 and Fabp5 on postnatal hippocampal neurogenesis in the mouse. Stem Cells. 2012;30:1532–43. doi: 10.1002/stem.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eusebi P, Giannandrea D, Biscetti L, Abraha I, Chiasserini D, Orso M, et al. Diagnostic utility of cerebrospinal fluid α-synuclein in Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mov Disord. 2017;32:1389–400. doi: 10.1002/mds.27110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou B, Wen M, Yu WF, Zhang CL, Jiao L. The diagnostic and differential diagnosis utility of cerebrospinal fluid α-synuclein levels in Parkinson’s disease: a meta-analysis. Parkinsons Dis. 2015;2015:567386. doi: 10.1155/2015/567386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Teunissen CE, Veerhuis R, De Vente J, Verhey FR, Vreeling F, van Boxtel MP, et al. Brain-specific fatty acid-binding protein is elevated in serum of patients with dementia-related diseases. Eur J Neurol. 2011;18:865–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mollenhauer B, Steinacker P, Bahn E, Bibl M, Brechlin P, Schlossmacher MG, et al. Serum heart-type fatty acid-binding protein and cerebrospinal fluid tau: marker candidates for dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurodegener Dis. 2007;4:366–75. doi: 10.1159/000105157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shioda N, Yabuki Y, Kobayashi Y, Onozato M, Owada Y, Fukunaga K. FABP3 protein promotes α-synuclein oligomerization associated with 1-methyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropiridine-induced neurotoxicity. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:18957–65. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.527341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheng A, Shinoda Y, Yamamoto T, Miyachi H, Fukunaga K. Development of FABP3 ligands that inhibit arachidonic acid-induced α-synuclein oligomerization. Brain Res. 2019;1707:190–7. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2018.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matsuo K, Cheng A, Yabuki Y, Takahata I, Miyachi H, Fukunaga K. Inhibition of MPTP-induced α-synuclein oligomerization by fatty acid-binding protein 3 ligand in MPTP-treated mice. Neuropharmacology. 2019;150:164–74. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2019.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.George JM, Jin H, Woods WS, Clayton DF. Characterization of a novel protein regulated during the critical period for song learning in the zebra finch. Neuron. 1995;15:361–72. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jin H, Ishikawa K, Tsunemi T, Ishiguro T, Amino T, Mizusawa H. Analyses of copy number and mRNA expression level of the alpha-synuclein gene in multiple system atrophy. J Med Dent Sci. 2008;55:145–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Asi YT, Simpson JE, Heath PR, Wharton SB, Lees AJ, Revesz T, et al. Alpha-synuclein mRNA expression in oligodendrocytes in MSA. Glia. 2014;62:964–70. doi: 10.1002/glia.22653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheng A, Kawahata I, Fukunaga K. Fatty acid binding protein 5 mediates cell death by psychosine exposure through mitochondrial macropores formation in oligodendrocytes. Biomedicines. 2020;8:635. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines8120635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shioda N, Han F, Moriguchi S, Fukunaga K. Constitutively active calcineurin mediates delayed neuronal death through Fas-ligand expression via activation of NFAT and FKHR transcriptional activities in mouse brain ischemia. J Neurochem. 2007;102:1506–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun M, Shinoda Y, Fukunaga K. KY-226 protects blood-brain barrier function through the Akt/FoxO1 signaling pathway in brain ischemia. Neuroscience. 2019;399:89–102. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2018.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu JW, Almaguel FG, Bu L, De Leon DD, De Leon M. Expression of E-FABP in PC12 cells increases neurite extension during differentiation: involvement of n-3 and n-6 fatty acids. J Neurochem. 2008;106:2015–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05507.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sulsky R, Magnin DR, Huang Y, Simpkins L, Taunk P, Patel M, et al. Potent and selective biphenyl azole inhibitors of adipocyte fatty acid binding protein (aFABP) Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2007;17:3511–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beniyama Y, Matsuno K, Miyachi H. Structure-guided design, synthesis and in vitro evaluation of a series of pyrazole-based fatty acid binding protein (FABP) 3 ligands. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2013;23:1662–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shinoda Y, Wang Y, Yamamoto T, Miyachi H, Fukunaga K. Analysis of binding affinity and docking of novel fatty acid-binding protein (FABP) ligands. J Pharmacol Sci. 2020;143:264–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jphs.2020.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yamamoto H, Fukui N, Adachi M, Saiki E, Yamasaki A, Matsumura R, et al. Human molecular chaperone Hsp60 and its apical domain suppress amyloid fibril formation of α-synuclein. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;21:47. doi: 10.3390/ijms21010047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sharon R, Bar-Joseph I, Frosch MP, Walsh DM, Hamilton JA, Selkoe DJ. The formation of highly soluble oligomers of alpha-synuclein is regulated by fatty acids and enhanced in Parkinson’s disease. Neuron. 2003;37:583–95. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ikeda M, Kawarabayashi T, Harigaya Y, Sasaki A, Yamada S, Matsubara E, et al. Motor impairment and aberrant production of neurochemicals in human alpha-synuclein A30P+A53T transgenic mice with alpha-synuclein pathology. Brain Res. 2009;1250:232–41. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bandopadhyay R. Sequential extraction of soluble and insoluble alpha-synuclein from Parkinsonian brains. J Vis Exp. 2016:53415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Zhang DW, Shao J, Lin J, Zhang N, Lu BJ, Lin SC, et al. RIP3, an energy metabolism regulator that switches TNF-induced cell death from apoptosis to necrosis. Science. 2009;325:332–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1172308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Giri S, Khan M, Rattan R, Singh I, Singh AK. Krabbe disease: psychosine-mediated activation of phospholipase A2 in oligodendrocyte cell death. J Lipid Res. 2006;47:1478–92. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600084-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tu PH, Galvin JE, Baba M, Giasson B, Tomita T, Leight S, et al. Glial cytoplasmic inclusions in white matter oligodendrocytes of multiple system atrophy brains contain insoluble alpha-synuclein. Ann Neurol. 1998;44:415–22. doi: 10.1002/ana.410440324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Conway KA, Lee SJ, Rochet JC, Ding TT, Williamson RE, Lansbury PT., Jr Acceleration of oligomerization, not fibrillization, is a shared property of both alpha-synuclein mutations linked to early-onset Parkinson’s disease: implications for pathogenesis and therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:571–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peelaerts W, Bousset L, Van der Perren A, Moskalyuk A, Pulizzi R, Giugliano M, et al. Synuclein strains cause distinct synucleinopathies after local and systemic administration. Nature. 2015;522:340–4. doi: 10.1038/nature14547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Prusiner SB, Woerman AL, Mordes DA, Watts JC, Rampersaud R, Berry DB, et al. Evidence for α-synuclein prions causing multiple system atrophy in humans with parkinsonism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:E5308–17. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1514475112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kisos H, Pukaß K, Ben-Hur T, Richter-Landsberg C, Sharon R. Increased neuronal α-synuclein pathology associates with its accumulation in oligodendrocytes in mice modeling α-synucleinopathies. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e46817. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reyes JF, Rey NL, Bousset L, Melki R, Brundin P, Angot E. Alpha-synuclein transfers from neurons to oligodendrocytes. Glia. 2014;62:387–98. doi: 10.1002/glia.22611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kagawa Y, Yasumoto Y, Sharifi K, Ebrahimi M, Islam A, Miyazaki H, et al. Fatty acid-binding protein 7 regulates function of caveolae in astrocytes through expression of caveolin-1. Glia. 2015;63:780–94. doi: 10.1002/glia.22784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Marshall MS, Jakubauskas B, Bogue W, Stoskute M, Hauck Z, Rue E, et al. Analysis of age-related changes in psychosine metabolism in the human brain. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0193438. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0193438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chang D, Nalls MA, Hallgrímsdóttir IB, Hunkapiller J, van der Brug M, Cai F, et al. A meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies identifies 17 new Parkinson’s disease risk loci. Nat Genet. 2017;49:1511–6. doi: 10.1038/ng.3955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Abdelkarim H, Marshall MS, Scesa G, Smith RA, Rue E, Marshall J, et al. α-Synuclein interacts directly but reversibly with psychosine: implications for α-synucleinopathies. Sci Rep. 2018;8:12462. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-30808-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rui Q, Ni H, Lin X, Zhu X, Li D, Liu H, et al. Astrocyte-derived fatty acid-binding protein 7 protects blood-brain barrier integrity through a caveolin-1/MMP signaling pathway following traumatic brain injury. Exp Neurol. 2019;322:113044. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2019.113044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liapounova N, Azar KH, Findlay JM, Lu JQ. Vanishing cerebral vasculitis in a patient with Lewy pathology. J Biomed Res. 2017;31:559–62. doi: 10.7555/JBR.31.20160119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ma LY, Gao LY, Li X, Ma HZ, Feng T. Nitrated alpha-synuclein in minor salivary gland biopsies in Parkinson’s disease. Neurosci Lett. 2019;704:45–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2019.03.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tao RR, Ji YL, Lu YM, Fukunaga K, Han F. Targeting nitrosative stress for neurovascular protection: new implications in brain diseases. Curr Drug Targets. 2012;13:272–84. doi: 10.2174/138945012799201649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]