Abstract

Objectives:

To examine how people living with dementia at home engage in meaningful activities, a critical component of quality of life.

Design:

Ethnographic study design using semistructured interviews, participant-observation, and ethnographic analysis.

Setting and Participants:

Home setting. People living with dementia were recruited through 3 geriatrics programs in the San Francisco Bay Area, along with 1 primary live-in care partner for each. Participants were purposively sampled to maximize heterogeneity of dementia severity and life experience.

Measurements:

We asked participants to self-identify and report meaningful activity engagement prior to dementia onset and during the study period using a structured questionnaire, semistructured dyadic interviews, and observed engagement in activities. Home visits were audio-recorded, transcribed, and inductively analyzed using thematic analysis.

Results:

Twenty-one people living with dementia (mean age 84 years, 38% women) and 20 care partners (59 years, 85% women), including 40% professionals, 35% spouse/partners, and 15% adult children. Overarching theme: specific activities changed over time but underlying sources of meaning and identity remained stable. As dementia progressed, meaningful activity engagement took 3 pathways. Pathway 1: Activities continued with minimal adaptation when engagement demanded little functional or cognitive ability (eg, watching football on TV). Pathway 2: care partners adapted or replaced activities when engagement required greater functional or cognitive abilities (eg, traveling overseas). This pathway was associated with caregiving experience, nursing training, and strong social support structures. Pathway 3: care partners discontinued meaningful activity engagement. Discontinuation was associated with severe caregiver burden, coupled with illness, injury, or competing caregiving demands severe enough to impact their ability to facilitate activities.

Conclusions and Implications:

For people living with dementia at home, underlying sources of meaning and identity remains stable despite changes in meaningful activity engagement. Many of the factors associated with adaptation vs discontinuation over time are modifiable and can serve as targets for intervention.

Keywords: Meaningful activities, dementia, caregiving relationships, personhood, ethnography

Quality of life is a priority for dementia care,1,2 and support of the identity or personhood of someone living with dementia is a key to maintaining quality of life.3 Meaningful activities—enjoyable activities related to personal interests and values4,5—offer an opportunity for people living with dementia to invoke and express their identity, yet we know little about meaningful activity engagement in the home. In the US, the majority of people living with dementia reside in the community,1 yet research on activities has been conducted almost entirely in nursing homes. In nursing homes, activities improve quality of life for people living with dementia by reducing behavioral symptoms thought to be manifestation of unmet need.6–9 Quality of life in nursing homes involves activities that are not merely scheduled, but that are meaningful to the people engaging in them and to their care partners.10,11 Although most community-dwelling people living with dementia continue to engage in meaningful activities,12 we do not know what activities are meaningful to people living with dementia and their primary care partners (dementia caregiving dyads), or how meaningful activities relate to identity or personhood for people living with dementia.

To develop an understanding of meaningful activity engagement among community-dwelling dementia caregiving dyads, we designed a qualitative study that examines the following research questions: In the home setting, what do dementia caregiving dyads identify as meaningful activities for people living with dementia, and how does engagement in these activities change as functional and cognitive status decline?

Methods

Study Design

This ethnographic, qualitative study13,14 used multiple in-home data collection methods, including a structured questionnaire, semistructured interviews, and participant observation to closely examine daily life for dementia caregiving dyads. This article reports on those portions of the study focused on meaningful activities for participants living with dementia; other portions of the study focused on the role of music in the caregiving relationship and the interplay of between functional status and relationships (manuscripts in preparation). The study adhered to the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) guidelines,15 and the 32-item checklist can be viewed as Supplementary Table 1.

Study Procedures

People living with dementia were purposively recruited through 1 Veterans Affairs home based primary care program, 1 university-based home medical care program, and 1 university-based geriatrics clinic in the San Francisco Bay Area. People living with dementia were included at all stages and types of dementia if they spoke English and had an identified care partner, unpaid or paid. Care partners were included if they resided with a person living with dementia, spoke English, and functioned as a primary care partner. We obtained written consent for all participants. Surrogates provided written consent for people living with dementia lacking decisional capacity. People living with dementia were free to assent or dissent during the study. Research approval was obtained through the University of California, San Francisco Institutional Review Board (Protocol 18–25894).

Data Collection

In-home interviews and observations were conducted by a PhD-trained ethnomusicologist (music anthropologist), an MD geriatrician/PhD ethnomusicologist, and a researcher with a master’s degree in psychology. We collected descriptive demographics (age, sex, race/ethnicity), data for both members of the dyads about chronic illnesses, favorite activities, functional assessment stage for dementia severity,16 and Katz functional status.17 For care partners, we also administered the 4-item Zarit caregiver burden screening tool.18 We conducted in-depth, semistructured dyadic interviews focused on everyday life and participant-observation focused on meaningful activities. Visits took place at the convenience of participants, occurring over a period of 2 weeks to 2 1/2 months. The combination of interview and observation enabled dyads to reflect on the meaning attached to activities and changes in activities over time and to demonstrate the activities themselves. Interviews and participant-observation were audio-recorded, professionally transcribed, and deidentified. Ethnographic field notes were written for each visit.13

Ethnographic Qualitative Data Analysis

Ethnographic analysis required multiple steps. Field notes and transcripts were inductively coded by 2 members of the research team involved in data collection. Concurrent data analysis was conducted throughout the study, and new transcripts were compared with prior data to enrich emerging themes and generate new codes. Open codes and emerging themes were interrogated through team discussion and the development of analytical memos, methods common to both ethnographic analysis13,14 and grounded theory.19,20 As themes emerged, a codebook was developed and used to refine interview and participant-observation guides. Once we reached a point of sufficient data for identification of key themes, additional dyads were purposively sampled to challenge and enrich the data. Triangulation and validation involved the purposive selection of additional dyads with differing perspectives in order to challenge themes and seek alternative explanations.19,20 Once no new themes emerged during triangulation and validation, data collection was ended.19 The codebook was applied to the 1452 pages of transcripts was using ATLAS.ti software to facilitate more nuanced examination of research questions through computer-assisted data analysis.

Results

Participants

Participants included 21 dyads that completed the structured interview, including baseline questions about favorite activities, 19 of whom completed the study. Participant characteristics are listed in Table 1. Data were collected between December 2018 and January 2020. People living with dementia were successfully recruited to achieve gender balance (38% women) and racial/ethnic/cultural diversity (57% people of color), but care partners were overwhelmingly women (85%) and people of color (85%). Dementia severity ranged from mild, defined as unable to manage any instrumental activities of daily living and with at least 1 impairment in activities of daily living, equivalent to Functional Assessment Staging category 3, to end-stage, with complete instrumental activities of daily living/activities of daily living dependence or Functional Assessment Staging category 7c (hospice-eligible severity).16 People living with dementia had multiple serious chronic illnesses: 11 died within 1 year of completing participation. The majority of the people living with dementia were enrolled in home-based primary care programs, and all but 1 of them were nursing home eligible at time of study.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| Participants (n = 41) | People Living with Dementia (n = 21) | Care partners (n = 20) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD) | 84 (8) y | 59 (16) y |

| Women | 8 (38%) | 17 (85%) |

| Self-identified people of color* | 12 (57%) | 17 (85%) |

| Dependent 3+ ADLs† | 15 (71%) | 0 |

| 3+ Chronic illnesses‡ | 14 (67%) | 1 (5%) |

| Zarit Caregiver Burden screen§ (mean ± SD) | - | 5 (6) |

| Dementia stage‖ | ||

| Mild | 5 (24%) | 1 (5%) |

| Moderate | 13 (62%) | - |

| End-stage (hospice eligible) | 3 (14%) | - |

| Care partner relationship | ||

| Live-in professional | - | 7 (35%) |

| Spouse | - | 8 (40%) |

| Adult child | - | 3 (15%) |

| Friend | - | 2 (10%) |

| Sibling | - | 1 (5%) |

ADL, activities of daily living; FAST, Functional Assessment Staging; IADL, instrumental activities of daily living.

People of color self-identified as Black/African American (4 people living with dementia, 3 care partners), Asian (3 people living with dementia, 3 care partners), white Hispanic (1 care partners), Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander (1 people living with dementia, 5 care partners), or other (3 care partners; Mexican, Creole, Filipino) in the demographic questionnaire. Ten participants self-categorized by country of origin in the interviews.

Katz ADLs.17

Chronic illnesses per self-report included hypertension, diabetes, arthritis, cerebrovascular disease including stroke, coronary artery disease with or without myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease/emphysema, depression, HIV/AIDS, cancer (not specified), dementia (not specified).

Zarit score of 8 or greater indicates a positive screen on the 4-item version.

FAST16 was used to define the following broad functional categories of dementia: Mild dementia was operationally defined as FAST stages 4 and 5, including dependence in IADLs and at need for oversight of some ADLs. Moderate dementia was operationally defined as all FAST stage 6 subcategories, including dependence in all IADLs and at least 1 ADL. End-stage dementia was defined as FAST category 7c, including total IADL/ADL dependence, limited language capability and limited life-expectancy (hospice eligible).16 None of the PLWD were in FAST stages 1, 2, 3, 7a, or 7b.

Meaningful Activities

People living with dementia were purposefully recruited for heterogeneity of age, stage of dementia, race/ethnicity/culture, gender, sexual orientation, housing setting, family structure, and caregiving relationship, so it was not surprising to discover heterogeneity in terms of the activities identified as meaningful. Prior to onset of dementia, participants identified over 50 activities that they considered to be favorite or meaningful activities. Activities included creative outlets such as sewing, quilting, gardening, writing, baking, and making music; exercise and outdoor activities including running, fishing, skiing, walking the dog, hiking, and tennis; deep-seated passions for sports, travel, going to shows, and local road trips; pleasure in everyday activities including cooking, eating, taking a bath, sleeping, getting a manicure-pedicure, or working in a meaningful vocation; and spiritual engagement, including worship services, singing hymns or other praise songs, prayer, and communal gatherings. Some people identified time spent with family and friends as most important, with activities involved in visits considered to be secondary.

Overview of Qualitative Findings

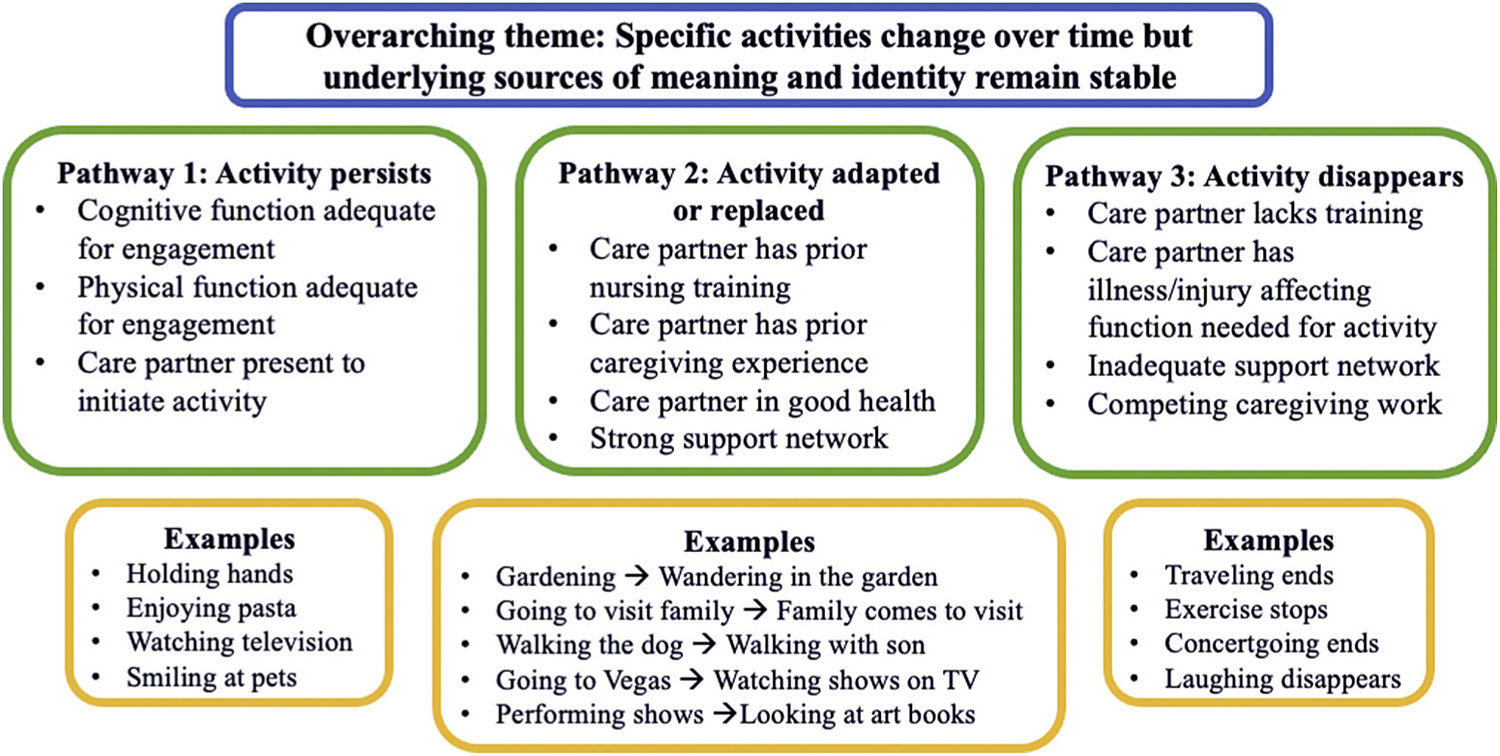

One overarching theme emerged: specific activities changed over time but the underlying sources of meaning and identity remained stable. Despite heterogeneity of activities and consistency of sources of meaning and identity, meaningful activity engagement followed one of three pathways as dementia progressed. Pathway 1: Activities were maintained with minimal adaptation when engagement was independent of functional or cognitive status. Pathway 2: Activities were adapted or replaced with new activities when engagement was dependent on functional or cognitive status. Adaptation and replacement were associated with care partner experience, nursing training and strong family support structures. Pathway 3: Activities were completely discontinued. Discontinuation was associated with care partner illness or injury, competing demands or other severe stressors impacting care partner functional or cognitive status (Figure 1).

Fig. 1.

Characteristics and examples of meaningful activity pathways.

Overarching Theme: Specific Activities Changed over Time but the Underlying Sources of Meaning and Identity Remained Stable

Dementia caregiving dyads engaged in a wide variety of meaningful activities before dementia onset and as dementia progressed (Table 2). Dyads framed activities in the context of identity and personhood, explaining how activities related to strongly held beliefs, values, passions, and favorite things to do. For one man with end-stage dementia, meaningful activities included watching TV, but only televised sermons reflective of his deeply religious identity and long-held faith. His friend/care partner explained how, over time, it had become more difficult for him to sit comfortably during worship services and how, years earlier, he had been able to articulate the importance of watching televised services at home. A patriarch with mild vascular dementia and hemiparesis had grown up in a Pacific island village in a family of male political leaders. Serving as head of the family was core to his identity. He took great joy in supporting the education of his children and grandchildren. At each research visit, he proudly pointed out the framed college and graduate school diplomas. Table 2 provides additional examples.

Table 2.

Themes, Pathways, and Examples of Engagement in Meaningful Activities

| Themes and Pathways | Examples from Transcripts and Field Notes |

|---|---|

| Overarching theme: Activities may change, but underlying meaning and identity remain stable | A wife care partner recalled important dinner rituals prior to spouse’s dementia diagnosis, “Every evening I made sure that we all sit down, no matter how busy we are…. we say our prayers and we eat Chinese food… because he loved the Chinese food,” Researchers then watched the care partner feed her husband with advanced Parkinson’s dementia a specially prepared drink, gently and lovingly, one teaspoon at a time. |

| A woman with moderate dementia, who had once been offered a professional backup singing gig, always loved to go to concerts. Over time, she became unable to leave the house. When her brother played music recordings on their TV, he found that “She seems to be smiling again, there were a lot of positive things… we watched [the film] ‘Pitch Perfect’ one, two, and three!” | |

| Pathway 1: Meaningful activities persist | A woman with dementia grew up eating Italian food. When researchers asked how her care partner helped her to engage in meaningful activities, the woman responded, “cooking some pasta!” |

| Car rides served as a meaningful activity in 4 homes. One care partner provided care for a husband and wife who both had dementia, and car trips were central to their everyday life. She reported using the opportunity to get them out of the house, explaining “we stopped at the coffee shop, their coffee shop, and then we get out, have a coffee, donut or cookie, whatever and after that we go to [a town 40 minutes away from the home]” | |

| Pathway 2: Meaningful activities are adapted | A man with dementia blurted, “Jaguar!” repeatedly, adding “I’m not too buzzed about it.” and asking when they could go for a ride. His professional care partner explained that he used to love racing around the back roads in his Jaguar, but that his family had to take away his keys. Now he engages in his passion for the road by riding in the back seat of her Prius, shouting “This, this and this! Make a left! Make a right!” |

| One couple was deeply invested in family and travel, but the partner with dementia became homebound. “So,” his partner explained, “if we’re celebrating Father’s Day or a birthday or something, usually everybody just comes here, and that’s usually fun.” | |

| Pathway 2: Meaningful activities are replaced | Prior to dementia onset, a woman had been involved in finance. She reflected, “Oh, it was fun to make money. I sat at a desk at home, and I bought and sold stocks.” Her daughter whispered, “She did very well actually.” By the time of the study, she was unable to manage money, so her daughter kept her well-supplied with novels and history books in an attempt to fill her time with other favorite activities. |

| Pathway 3: Meaningful activities disappear | A man living with mild dementia, unilateral low vision, and hearing loss had become increasingly isolated, “I don’t even hardly go out into the backyard anymore… That was my mainstay. I used to work in the backyard. It was a beautiful place.” When asked why he no longer went out, his wife/care partner said, “It’s just a hassle for him to leave the house” and he replied “Oh. Well, I slowed way down.” |

| A wife/care partner explained how her spouse used to be active before his dementia, “We used to love to travel [in the truck] with the dog… he used to work on his motorcycle a lot” When asked what he likes now she replied, “A cigarette. I mean, that’s it.” She described being totally exhausted, overwhelmed and unable to adapt his other favorite activities. |

Pathway 1: Meaningful Activities with Few Cognitive or Functional Requirements Persist as Dementia Progresses

Care partners maintained activities with minimal adaptation among all people living with dementia, regardless of dementia progression, when engagement demanded little functional or cognitive ability. For example, a man with mild Alzheimer’s disease loved to go for walks with a neighbor each day. A woman with moderate vascular dementia still loved to go on road trips with her sibling (care partner), to see their out-of-state relatives. Even in end-stage dementia, care partners identified activities that were still enjoyed and demonstrated examples. For one man with low vision and end-stage mixed dementia, eating favorite foods and visiting with his friends remained lifelong pleasures. His close friend/care partner, who had extensive caregiving experience, attended to his nonverbal cues to figure out what he wanted to drink before offering milk rather than water, pointing out how he smiled back after quenching his thirst and saying “no” to the offer of more. Table 2 provides additional examples.

Pathway 2: Meaningful Activities Are Adapted or Replaced with New Activities

Dementia progression involves both cognitive and functional decline, making some activities insurmountably difficult over time. In some homes, care partners adapted or replaced activities when engagement exceeded the functional or cognitive abilities of people living with dementia. For example, a professional musician with mild dementia who specialized in contemporary orchestral music had a highly cerebral relationship to music. As his episodic memory declined, live music concert attendance became impossible. To maintain his lifelong engagement with the arts, his family created and curated a website for his recordings. His spouse/care partner bought him books on the visual arts, which became his new source of fascination. He summed up his activity engagement by saying, “The life that I have is just so incredibly rich.”

When activities could not be adapted, care partners replaced them with other activities enjoyed by the person living with dementia. In one case, a woman with moderate dementia had always been very social but became afraid to leave the apartment as her Alzheimer’s disease progressed. “She had quite a bit of friends, you know. She had a large family,” her spouse/care partner explained, “She’s got a big heart, loves kids.” To provide an outlet for her “big heart,” he bought her dozens of stuffed animals, which she treated as children, conversing with them constantly in brief phrases like “My baby!” All but one of the care partners in these homes reported adequate support structures. Many reported professional caregiving training, including nursing training, and only 2 had positive Zarit caregiver burden screens. All professional care partners provided care on this pathway. Table 2 provides additional examples.

Pathway 3: Meaningful Activities Disappear

In other homes, dementia caregiving dyads discontinued meaningful activities as dementia progressed. Discontinuation was associated with severe caregiver burden: all care partners who discontinued activities had a positive Zarit caregiver burden screen. These care partners reported that they no longer had the energy needed to facilitate creative adaptation of meaningful activities, even when issues were as minor as a broken Bluetooth connection. These care partners all reported inadequate social support structures, personal illness and injury, or competing caregiving demands on top of the daily stress of dementia caregiving. None had caregiving or nursing training. One spouse/care partner gave examples of the increase in daily work: “He did all the cooking. I never cooked. Never. He was the cook. So, I really miss that part, too, a lot. He was a lot of help. Honestly, he did everything; very good man, very good man; very good provider.” She described her worsening depression, how she was so overwhelmed that she could not figure out a way to bring their beloved dog in from the yard to visit her spouse who had moderate dementia. In another dyad, one man had mild vascular dementia, diabetes and vision loss and his husband/care partner had developed a rotator cuff tear from overuse of his crutches. They previously loved to cook romantic dinners together and both reported disliking the food that could be delivered, yet neither was able to cook anymore. Table 2 provides additional examples.

Discordant Findings

Even in cases of extreme caregiver stress, however, not every favorite activity disappeared. In the case of the man with delirium-associated dementia, his wife/care partner said he no longer engaged in meaningful activities, yet she hired a professional to help him with breakfast, his favorite meal, and she continued to provide him with cigarettes as his one remaining source of enjoyment. For the dyad who loved romantic dinners, the husband living with dementia spent most of his days in the kitchen, endlessly watching news on television. The husband with dementia expressed appreciation for the small television that his care partner had installed in the kitchen, explaining how important it was for him to watch the news during the current political climate (2019).

Discussion

We examined meaningful activity engagement among people living with dementia who, prior to dementia onset, had engaged in a heterogeneous set of self-identified meaningful activities. We found that specific activities changed, but the underlying sources of meaning and identity remained stable as dementia progressed. Meaningful activity engagement was tied to cognitive and physical function, support structures and caregiver burden. In pathway 1, activities with few cognitive or functional requirements were maintained as dementia progressed (eg, watching televised sermons, enjoying favorite foods). When dementia progression led to cognitive or functional decline, engagement took different pathways. In pathway 2, activities were adapted or replaced by care partners (eg, maintaining a love of driving by going on rides). These care partners reported adequate support structures, professional training, or prior caregiving experience. In pathway 3, meaningful activities disappeared. These care partners reported inadequate support structures and high levels of caregiver burden, compounded by issues of personal illness, injury, and competing caregiving obligations.

Community-dwelling dementia caregiving dyads demonstrated how meaningful activities reflected underlying sources of meaning and identity for people living with dementia. Our study reinforces the importance of supporting identity or personhood in dementia care.3 As with studies of play in the context of dementia caregiving, positive emotions emerged when participants engaged in meaningful activities during research visits.21

The disappearance of meaningful activities in the context of caregiver burden raises questions about causality. Three visits were inadequate to determine whether caregiver burden led to disappearance of meaningful activities and/or whether lack of meaningful activities exacerbated caregiver burden. Yet both family care partners and people living with dementia reflected on how many more activities they engaged in prior to dementia onset. The inability of people living with dementia to engage in prior meaningful activities was reported as a source of distress particularly by their family members. Simultaneously, family care partner health and social stressors created barriers to adaption or replacement of activities. Some of the sources of caregiver burden identified by the care partners may have been modifiable,22 and might be alleviated through engagement in existing, evidence-based programs to reduce caregiver burden such as REACH VA and the Paired Preventing Loss of Independence through Exercise (Paired PLIÉ) programs.23,24 Reducing burden and increasing support may provide opportunities for care partners to remain engaged in meaningful activities with people living with dementia. Social support networks can be modified through investments in long-term services and supports including in-home caregiving, gerontological case management, financial support and interprofessional geriatrics programs. Care partner support would be enhanced by the inclusion of recreation therapists or music therapists, professionals specialized in meaningful activity engagement, and development of treatment plans focused on adapted or new activities.

Conclusions and Implications

Overall, we found that nursing home-eligible, community-dwelling people living with dementia continued to engage in meaningful activities as long as their care partners remained fairly healthy and had adequate support and training. Underlying sources of meaning remained stable despite changes in activities as function and cognition declined. Clinically, this study raises questions for future research, because the small sample cannot be generalized. With this caveat in mind, meaningful activities only disappeared in homes with severely strained care partners. As home medical care and post-acute rehabilitation clinicians, we might consider asking care partners of people living with dementia if they still engage in meaningful activities, viewing the absence of activities as indication for further inquiry or caregiver burden screening. The findings provide foundational data prerequisite to the development of clinical screening tools and targets for intervention development to improve quality of life for people living with dementia and their care partners, and ideally to maintain them in their noncongregate home setting.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Our gratitude goes to Annette Rodriguez for her involvement in data collection, database management, and analysis, to Sarah Ngo for her unflagging support throughout this project, to the participants who have taught us so much, and to the clinical team members who care for them. Portions of this report were presented at the 2020 Gerontological Society of America Annual Meeting and the Presidential Poster Session at the 2021 American Geriatrics Society Annual Meeting. Sponsors had no role in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collection, analysis, or preparation of this paper. This article does not represent the views of the US Department of Veteran Affairs or the US government.

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging (K23AG062613 to Allison, 3P30AG044281-06S1 to Covinsky, K01AG059831 to Harrison, and K24AG068312 to Smith), by the Medical Student Training in Aging Research program (T35AG026736 to KP), and in part through a grant from the Osher Center for Integrative Medicine at the University of California, San Francisco to Allison).

References

- 1.Alzheimer’s Association. Alzheimer’s Disease facts and figures, Alzheimer’s Dement, 17, 2021, Chicago: Alzheimer’s Association. Available at: https://www.alz.org/media/Documents/alzheimers-facts-and-figures.pdf. Accessed September 6, 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Global action plan on the public health response to dementia 2017‒2025. World Health Organization. 2017. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/259615/1/9789241513487-eng.pdf?ua=1. Accessed February 27, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kitwood T Dementia Reconsidered: The Person Comes First. Philadelphia, PA: Open University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rowe JW, Kahn RL. Successful aging. Gerontologist 1997;37:433–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Irving J, Davis S, Collier A. Aging with purpose: Systematic search and review of literature pertaining to older adults and purpose. J Aging Human Dev 2017;85: 403–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Volicer L, Simard J, Pupa JH, et al. Effects of continuous activity programming on behavioral symptoms of dementia. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2006;7:426–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGuinn KK, Mosher-Ashley PM. Participation in recreational activities and its effect on perception of life satisfaction in residential settings. Activities Adaptation Aging 2001;25:77–86. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hunter PV, Thorpe L, Hounjet C, Hadjistavropoulos T. Using normalization process theory to evaluate the implementation of montessori-based volunteer visits within a canadian long-term care home. Gerontologist 2018;60:182–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scales K, Zimmerman S, Miller SJ. Evidence-based nonpharmacological practices to address behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Gerontologist 2018;58:S88–S102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allison TA, Smith AK. “Now I Write Songs”: Growth and reciprocity after long-term nursing home placement. Gerontologist 2020;60:135–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Allison TA, Balbino RT, Covinsky KE. Caring community and relationship centred care on an end-stage dementia special care unit. Age Ageing 2019;48: 727–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oh A, Gan S, Boscardin WJ, et al. Engagement in meaningful activities among older adults with disability, dementia, and depression. JAMA Intern Med 2021; 181:560–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schensul JJ, LeCompte M. Essential Ethnographic Methods: A Mixed Methods Approach. Second ed. New York: Rowman and Littlefield; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldaña J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook. 4th Edition. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus group.s. Int J Qual Health Care 2007;19:349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sclan SG, Reisberg B. Functional Assessment Staging (FAST) in Alzheimer’s Disease: Reliability, validity, and ordinality. Int Psychogeriatr 1992;4:55–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katz S, Down T, Cash H, Grotz R. Progress in the development of the index of ADL. Gerontologist 1970;10:20–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bédard M, Molloy DW, Squire L, et al. The Zarit Burden Interview: A New Short Version and Screening Version. Gerontologist 2001;41:652–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Charmaz K Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. 3rd Ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Swinnen A, de Medeiros K. “Play” and people living with dementia: a humanities-based inquiry of timeslips and the Alzheimer’s poetry project. Gerontologist 2018;58:261–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hughes TB, Black BS, Albert M, et al. Correlates of objective and subjective measures of caregiver burden among dementia caregivers: Influence of unmet patient and caregiver dementia-related care needs. Int Psychogeriatr 2014;26: 1875–1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nichols LO, Martindale-Adams J, Burns R, et al. Translation of a dementia caregiver support program in a health care system—REACH VA. Arch Intern Med 2011;171:353–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Casey JA-O, Harrison KA-O, Ventura MI, et al. An integrative group movement program for people with dementia and care partners together (Paired PLIÉ): Initial process evaluation. Aging Ment Health 2020;24:971–977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.