Abstract

The study was conducted to investigate the effect of spatial variation, alkali treatment and the volume of extractant on yield and gel strength of agar for three Gracilaria species (G. salicornia, G. edulis and G. corticata) collected from the Tanzanian coast (Dar es Salaam, Tanga and Zanzibar). Treated and untreated G. corticata showed the highest yield (27 ± 0.7 % and 26.2 ± 1.3 % for treated and untreated, respectively), followed by G. salicornia then G. edulis. G. salicornia collected from Zanzibar showed the highest mass yield (22.9 ± 4.3 % for treated) followed by those collected from Tanga. Varying the volume for extraction showed no significant difference in mass yield where the p-value was >0.05. The highest gel strength was recorded from treated G. salicornia collected from Tanga (495 ± 29.5 gcm−2). Gel strength varied significantly between species. Spatial variability showed a significant difference in gel strength; the sample collected from Tanga showed the highest gel strength, followed by Zanzibar then Dar es Salaam. The variation due to the volume of distilled water used for extraction showed no significant difference in gel strength at a p-value >0.05. The highest gel strength was recorded at the volume of 1500 mL (467.5 ± 98.4 gcm−2), and the smallest gel strength was recorded at 500 mL. In all cases, there was a significant difference in mass yield and gel strength between treated and untreated samples. G. salicornia showed promising results as a local source of agar as it showed the highest gel strength though it produced an intermediate amount of agar. Based on the finding of this study, the volume of extraction of agar should be maintained as 1000 mL because by increasing the volume of extraction from 1000 mL to 1500 mL, the agar yield and gel strength don't change significantly. Agar yield and gel strength of Gracilaria species (G. salicornia, G. edulis and G. corticata) can be improved by alkali treatment, but further study is needed to determine the optimum amount and concentration of alkali to be used that will produce maximum yield and gel strength.

Keywords: Agar, Gel strength, G. salicornia, G. edulis, G. corticata, Alkali treatment, Seaweed

Agar; Gel strength; G. salicornia; G. edulis; G. corticata; Alkali treatment; Seaweed.

1. Introduction

Currently, the demand for agar in Africa, including Tanzania, is growing rapidly due to the increasing number of biotechnology and microbiology laboratories. However, the supply system depends wholly on importation. In Tanzania, the problem remains big despite being a home of several species of seaweeds, which are the major raw material for agar production.

The genus Gracilaria is of considerable economic importance as an agarophyte, and it is the most abundant and promising resource of agar production. It has more than 150 species, distributed mainly in the temperate and subtropical zones (Radiah et al., 2011). The value of Gracilaria has increased with demand because of the high production cost of the agar from the genus Gelidium and insufficient wild stock of this genus. Therefore, more than half of the world agarophyte tonnage consists of Gracilaria (McHugh, 1991). Different species of Gracilaria include G. edulis, G. corticata, G. millardetii, G. debilis (formally G. fergusonii) and G. salicornia have been reported to be potential sources of agar along the Indian Ocean water, including Tanzania (Jaasund, 1976; Kappanna and Rao 1963; Guiry and Guiry, 2021).

The yield and physical properties of agar such as gel strength, gelling and melting temperature define its value to industries. The gel-forming properties of agar are widely used in the pharmaceutical, cosmetics, and food industries (Marinho-Soriano, 2001). The structure of agar consists of alternating β-1,3 and α-1,4 linked D and L galactose residues, respectively. The charged residues are present on the polysaccharide chain, of which the most frequent substituents are sulfate esters and pyruvate ketal groups (Lahaye and Rochas 1991). The gel properties are highly dependent on the amount and position of sulfate groups and the amount of 3,6-anhydrogalactose fraction of the phycocolloid (Duckworth and Yaphe, 1971). However, Gracilaria spp. contain several structures with different substitutes such as sulfate esters, methoxyl and pyruvic acids (Andriamanantoanina et al., 2007). The amount of these substituents affects the physical properties of the gel. Craigie (1990) stated that the molecular structure of agar polysaccharides from the genus Gracilaria appears as species-specific, particularly the type and location of sulfate esters.

Species is not the only factor of variance in yield and quality of agar but factors such as environmental conditions and seasonal variations (Bird, 1988), physiological factors (Craigie et al., 1984) and extraction methods (Freile-Pelegrin and Robledo, 1997) affects the relative proportion of algal constituents. Generally, Gracilaria species produce agars with low quality due to high sulfate content, and therefore, they are called agaroides. However, transformations of agaroides into real agar can be done by alkali treatment, which converts L-galactose- 6-sulfate to 3,6-anhydro-L-galactose by the treatment of Gracilaria with sodium hydroxide (Armisen, 1995).

The present research aimed to study the influence of spatial variation, alkali treatment and the volume of extractant on the characteristics of agar (Mass yield and gel strength) produced from three Gracilaria species G. edulis, G. corticata and G. salicornia collected along the coast of Tanzania.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Sample collection and preparation

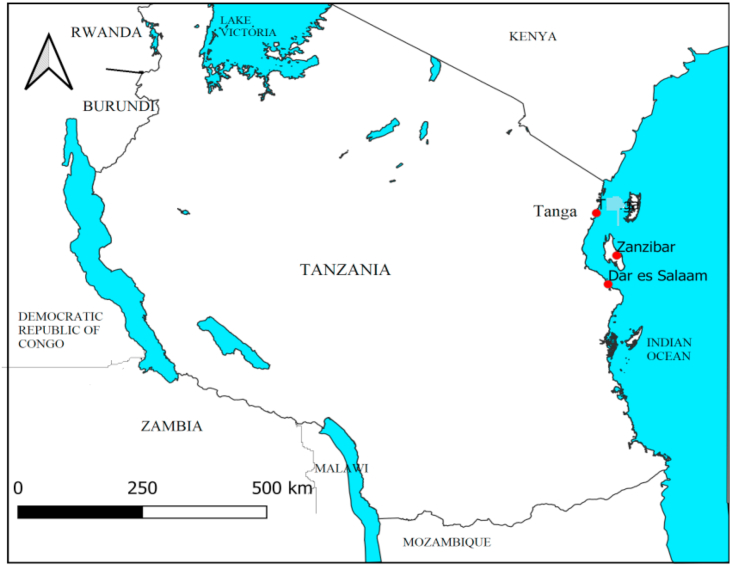

Specimens of G. salicornia, G. edulis and G. corticata were collected from natural stocks from three different locations along the coast of Tanzania (Zanzibar, Tanga and Dar es Salaam) as shown in Figure 1. The collected samples were washed using seawater to remove sands and other contaminants then washed thoroughly with tap water and exposed to sunlight for bleaching. The bleaching procedures were repeated for two weeks. Finally, the bleached samples were stored in plastic bags until the time for agar extraction.

Figure 1.

Map of Tanzania showing sampling location.

2.2. Alkali treatment

Bleached samples were soaked in 350 mL of 20 % aqueous NaOH for three days at room temperature, then washed with water until the pH ranged between 7-8. The samples were then sun dried for 2 h before being mixed with 1000 mL of distilled water. The pH of the mixture was adjusted to 5.6 by adding acetic acid and allowed to dry for 30 min.

2.3. Agar extraction

A portion of 25 g of bleached samples of G. salicornia, G. corticata and G. edulis from three different sites (Tanga, Zanzibar and Dar es Salaam) were used for agar extraction with and without alkali treatment. Different portions of samples (25 g) were mixed with 1000 mL of distilled water and then placed in a water bath at 95 °C for 1 h. Another set of experiments was conducted by extracting 25 g of samples using three different volumes (1500 mL, 1000 mL and 500 mL) of distilled water. The resulted samples were homogenized in a blender and immediately put in a filter cloth (nylon) with the addition of 100 mL of hot distilled water and squeezed to allow the filtration to take place. The agar solution obtained was poured in an aluminium pan. The solution was cooled and allowed to gel at room temperature. The gel was cut into square bars and then frozen for 24 h in a deep freezer. The frozen gel was thawed, washed with distilled water, and dried in the sun for 1 day and then in an oven at 60 °C to a constant weight. Agar was then weighed and ground in a Micro Hammer Mill "Culatti" to a 100-mesh powder. The percentage yield of agar was calculated using the formula below:

| Agar Yield (%) = [(Dry weight of agar (g)/ Dry weight of seaweed (g))] × 100 |

Gel strength (gcm−2) was measured by taking a portion of 50 mL of 1.5 % w/v solution of extracted and standard agars, each one separately and autoclaved at 120 °C for 30 min. After the gel formation at room temperature, the gel was stabilized at 5 °C for overnight in a refrigerator. The gel strength of agar was then measured at 20 °C by Brookfield CT3 Texture Analyzer (Brookfield Engineering Labs., Inc) using a cylindrical probe (TA10 Cylinder 12.7 mm diameter, 35 mm long). Sulfate was determined using the infrared (IR) spectrophotometry method using a Perkin–Elmer 983G. The relative absorbance ratio was calculated at 930/2920 and 1250/2920 cm−1 for 3,6-anhydrogalactose and total sulfates, respectively (Lahaye and Yaphe, 1988). All data were analyzed using Statistica 7 and Origin Pro 8.5.

2.4. FTIR spectroscopy of agar

Two grams powder of extracted agar was mixed with potassium bromide to prepare a solid disc and FTIR spectra were collected from 4000-500 cm−1 range in transmission mode with 2 cm−1 resolution over 10 scans by using spectrometer.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Variation of mass yield and Gel strength between Gracilaria species

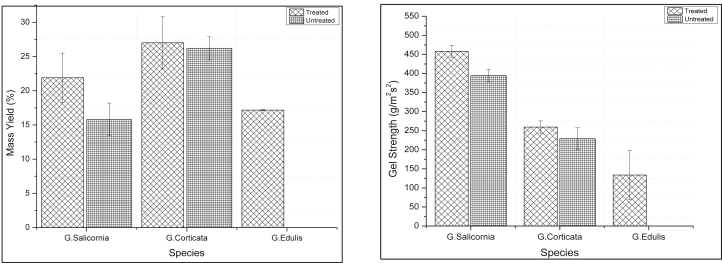

Table 1 summarizes the results of Two-Way ANOVA. The agar yield and gel strength from the three species varied significantly, where p-value was >0.05. For both treated and untreated experiments G. corticata specie showed highest mass yield 27 ± 0.7 % (treated) and 26.2 ± 1.3 % (untreated) followed by G. salicornia 21.9 ± 0.7 % (treated) and 15.8 ± 0.7 % (untreated), while G. edulis specie show smallest mass yield 17.2 ± 1.6 % (treated) as shown in Figure 2. It is well established that, agar yield of Gracilaria species varied among each other (Arminsen, 1995). The agar content of G. edulis specie recorded in this study differs from that observed from the study conducted by Ganesan and Subba Rao (2004). The agar content was higher in all conditions compared to what was observed in this study. They found that the agar content ranged from 18.5 to 50.3 % for untreated samples, acid-treated agar content ranged from 30.5 to 60.8 %, the agar content for 1 % KOH ranged from 30 to 60.6 % and for 0.5 % of acetic acid + 1 % of KOH agar content ranged from 55.3 to 69.2 %. The agar content for G. corticata species recorded in this study was higher compared to that recorded by Ramavatar et al., (2008) where they obtained values ranging from 16 ± 0.8 to 9.5 ± 0.1 %. These differences may be due to the difference in geographical location and extraction methods used, as reported by Kumar and Fotedar (2009). The agar yield for G. salicornia recorded in this study is closely similar to that recorded by Buriyo and Kivaisi in 2003 where the agar yield ranged from 13.7 to 30.2 %. The possible reasons for these similarities can be the similar geographical location of samples.

Table 1.

Summary of Variation of Mass yield and Gel strength among Gracilaria species.

| Effects | df | Mass Yield (%) |

F | P | Gel strength (gm−2s−2) |

F | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MS | SS | MS | SS | ||||||

| Species | 2 | 412.8 | 825.5 | 37.1 | <0.001 | 328175.83 | 656351.66 | 64.139 | <0.001 |

| Treatment | 1 | 272.5 | 272.5 | 24.5 | <0.001 | 62629.4 | 62629.4 | 14.19 | <0.001 |

| Error | 62 | 11.1 | 689.6 | 4413 | 269223.5 | ||||

| Total | 65 | 1936.7 | 983775.8 | ||||||

| Spatial | 2 | 39.3 | 78.6 | 5.0 | 0.012 | 20886.007 | 41772.014 | 10.126 | <0.001 |

| Treatment | 1 | 387.7 | 387.7 | 49.2 | <0.001 | 81700.694 | 81700.694 | 19.725 | <0.001 |

| Error | 34 | 7.9 | 267.9 | 2062.571 | 70127.431 | ||||

| Total | 37 | 703.5 | 192181.579 | ||||||

| Volume | 2 | 31.9 | 63.9 | 3.2 | 0.062 | 4929.1667 | 6858.33 | 1.427 | 0.26 |

| Treatments | 1 | 221.2 | 221.2 | 22.2 | <0.001 | 60501.042 | 60501.042 | 17.520 | <0.001 |

| Error | 20 | 10.0 | 191.6 | 3453.229 | 69064.583 | ||||

| Total | 23 | 484.3 | 139424.958 | ||||||

MS = Mean Squares, SS = Sum of Squares, df = Degree of Freedom.

Bolded value show no significant difference.

Figure 2.

Percentage mass yield (Left) and gel strength (Right) of Gracilaria species.

G. salicornia specie show highest gel strength of 458 ± 15.5 gcm−2 (treated) and 394.4 ± 16.4 gcm−2 (untreated) followed by G. corticata 259.4 ± 16.4 gcm−2 (treated) and 229.2 ± 28.3 gcm−2 (untreated) while smallest gel strength was recorded from G. edulis specie 133.8 ± 64.4 gm−2s−2 (treated). The gel strength of G. edulis observed in this study is higher compare to that recorded by Ganesan and Subba Rao (2004), where they have recorded a maximum of 96.5 ± 2.9 gcm−2. Ramavatar et al., (2008) record a maximum of 490 ± 8.3 gcm−2 gel strength for G. edulis specie and 110 ± 8.9 gcm−2 for G. corticata species, which differs from the finding of the present study. These differences can be due to the difference in extraction processes, length of time of treatment and concentration of alkali.

3.2. Effect of spatial variation on mass yield and gel strength

Spatial variation showed a significant difference in mass yield and gel strength, where p-value >0.05. G. salicornia collected from Zanzibar showed highest mass yield 22.9 ± 4.3 % (treated), 16.8 ± 2.3 % (untreated) followed by those collected from Tanga 21.2 ± 0.3 % (treated), 13.7 ± 0.2 % (untreated) and Dar es salaam showed the smallest mass yield of 18.1 % (treated). Samples collected from Tanga showed the highest gel strength 495 ± 29.5 gcm−2 (treated), 453.3 ± 23.4 gcm−2 (untreated). In contrast, a sample from Dar es salaam showed smaller gel strength (442 ± 10.6 gcm−2) for treated compared to those which were collected from Zanzibar 467.7 ± 48.8 gcm−2 (treated), 342.5 ± 47.6 gcm−2 (untreated) as it shown in Figure 3. Buriyo and Kivaisi (2003) recorded the highest gel strength of 270 gcm−2 which is smaller than that recorded in this study. Different studies showed that, seaweed collected from different geographical locations differ in agar yield and gel strength. This is because they experience different environmental parameters like nutrients, which can affect seaweed's mass yield and gel strength. Buriyo and Kivaisi (2003) recorded different mass yield and gel strength between Dar es Salaam and Chwaka (Zanzibar), in contrast to the present study, they have recorded higher mass yield in Dar es salaam then in Zanzibar, but gel strength was higher in Zanzibar then Dar es Salaam similar to the present study.

Figure 3.

Spatial variation mass yield (Left) and gel strength (Right) of Gracilaria salicornia samples in three study sites.

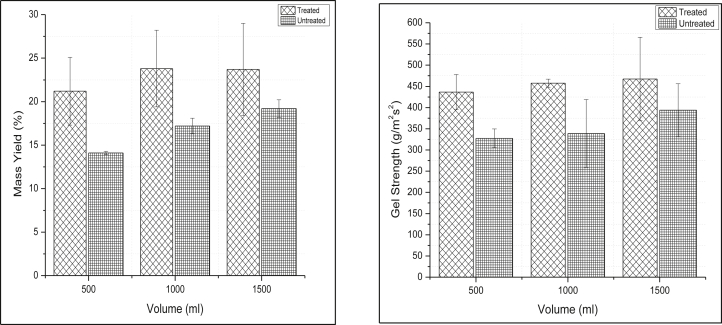

3.3. Effect of volume of extraction on mass yield and gel strength

Difference in the volume of extraction used showed no significant difference in mass yield and gel strength where the p-value is > 0.05 (Figure 4). For the treated experiment, the highest mass yield was recorded at both 1500 mL and 1000 mL where the yield was 23.7 ± 5.3 %, and 23.4 %, respectively and the smallest mass yield was recorded at 500 mL 21.2 ± 3.9 %. For untreated experiment, the yield was 19.2 ± 1 %, 17.2 ± 0.9 % and 14.1 ± 0.2 % for 1500 mL, 1000 mL and 500 mL respectively. The highest gel strength was recorded at 1500 mL 467.5 ± 98.4 gcm−2 (treated) and 393.8 ± 62.4 gcm−2 (untreated) and the smallest gel strength recorded at 500mL 436.3 ± 41.5 gcm−2 (treated) and 327.5 ± 22.2 gcm−2 (untreated).

Figure 4.

Effect of volume of extractant on mass yield (Left) and gel strength (Right) of Gracilaria species.

3.4. Effect of alkali treatment

Generally, there was a significant difference in mass yield between treated and untreated samples in all species, sites, and varying the volume of distilled water as shown in Table 1. In this study mass yield and gel strength were higher for alkali-treated then untreated samples. Based on the finding of this study, the highest mass yield observed was 27 ± 0.7 % (treated) for Gracilaria, which appears to be higher compared to that reported by Radiah et al., (2011) where the mass yield of both alkali-treated and untreated ranged from 7.1 % to 13.5 %. Radiah et al., (2011) also find that alkali-treated show low mass yield compared to untreated samples, which differ from the present study. This difference may be due to the difference in concentrations of alkali (NaOH) used, and the length of time of treatment. However, according to Ganesan and Subba Rao (2004) pre-extraction treatment using alkali or acid was observed to facilitate the retention of higher yield compared to untreated samples.

3.5. FT-IR spectra analysis of agar sample

The results of FT-Infra red spectra of agar samples were compared with that of standared Difco agar and the results reported by Balkan et al. (2005) as indicated below:

Sample agar: 650, 720, 780, 850, 1030, 1120, 1250, 1350, 1420, 1480, 1580, 1620, 2300, 2880, 3580, 3800 cm−1.

Difco agar: 650, 690, 713, 771, 869, 891, 931, 989, 1045, 1072, 1218, 1251, 1544, 1643, 2933 cm− 1 (Balkan et al., 2005).

The spectrum of agar from Gracilaria salicornia shows similarities with those of Standard Difco agar (Figure 5). Both show the characteristic bands at 650, 1030 and 1250 cm−1. Other bands which were found in G. salicornia with approximately the same values as in Difco agar were 720 (713), 780 (771, 778), 1350 (1362), 1420 (1434) cm−1. On the other hand, the bands at 850, 1120, 1480, 1620, 2300, 2880, 3580, 3800 cm−1 appear only in G. salicornia agar sample.

Figure 5.

FT-IR spectrum of A1- Standard Difco-agar and Z5 Gracilaria salicornia agar sample.

The absorbance between 720 -770 cm−1 indicates the existence of skeletal bending of the galactose ring. The band at 850 cm−1 also indicates the presence of D-galactose-4-sulphate. The absorbance at 1250 and 850 cm−1 indicates the presence of sulphate esters. This result is similar to earlier observations (Cabassi et al., 1978). The absence of IR bands at 705, 805 and 1070 cm−1 indicates low sulphate groups in extracted agar. The bands at 1420 and 1350 cm−1 are common to all spectra of polysaccharides associated with stretching of CH3/CH2 groups. The band at 890 cm−1 was found in Difco agar and absent in G. salicornia agar sample. This band is attributed to anomeric C–H of beta galactose residues. The absorbance at 930 and 1070 cm−1 found in Difco agar and absence in the sample agar is attributed to 3,6 anhydrogalactose. The absorbance at 1030 cm−1 present in sample agar and Difco agar, is assigned to C–C and C–O stretching vibrations of pyranose ring common to all polysaccharides. It was concluded that the analysis of sample IR-spectra confirm the extracted polysaccharides is an agar.

4. Conclusion

The amount of agar content (yield) and gel strength varied between species, sites, and extraction volume. G. salicornia showed some promising results as a local source of agar as it showed the highest gel strength though it produced an intermediate amount of agar. Based on the finding of this study, the volume of extraction of agar should be maintained as 1000 mL because increasing the volume of extraction from 1000 mL to 1500 mL doesn't change the agar yield and gel strength significantly. Agar yield and gel strength of Gracilaria species can be improved by alkali treatment but further study is needed to determine the optimum amount and concentration of alkali to be used to produce maximum yield and gel strength at a minimum cost. Based on the analysis of sample IR-spectra, the extracted polysaccharides is suggested to an agar.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Said Vuai: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This work was supported by Tanzania Commission for Science and Technology.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledges Prof. Elena Kalmykova and Lipetsk State University, the Institute of Physiology, Ural Branch of RAS (Syktyvkar) Russia for FT-IR analysis and the Sokoine University of Agriculture for gel strength analysis.

References

- Andriamanantoanina H., Chambat G., Rinaudo M. Fractionation of extracted Madagascan Gracilaria corticata polysaccharides: Structure and properties. Carbohydr. Polym. 2007;68:77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Armisen R. World-wide use and importance of Gracilaria. J. Appl. Phycol. 1995;7:231–243. [Google Scholar]

- Balkan G., Coban B., Güven K.C. Fractionation of agarose and Gracilaria verrucosa agar and comparison of their IR spectra with different agar. Acta Pharm. Turc. 2005;47:93–106. [Google Scholar]

- Bird K.T. Agar production and quality from Gracilaria sp. Strain G —16: effects of environmental factors. Bot. Mar. 1988;31:33–39. [Google Scholar]

- Buriyo A.S., Kivaisi A.K. Standing stock, Agar yield and properties of Gracilaria saliconia harvested along the Tanzanian coast: western Indian. Ocean J. Mar. Sci. 2003;2:171–178. [Google Scholar]

- Cabassi F., Casa B., Perlin A.S. Infrared absorption and Raman scattering of sulfate groups of heparin and related glycosaminoglycans in aqueous solution. Carbohydr. Res. 1978;63:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Craigie J.S. In: Biology of the Red Algae. Cole K.M., Sheath R.G., editors. 1990. Cell walls. [Google Scholar]

- Craigie J.S., Wen Z.-C., Van der Meer J.P. Interspecific, intraspecific and nutritionally determine variations in the composition of agar from Gracilaria spp. Bot. Mar. 1984;27:55–61. [Google Scholar]

- Duckworth M., Yaphe W. The structure of agar : Part I. Fractionation of a complex mixture of polysaccharides. Carbohydr. Res. 1971;16:189–197. [Google Scholar]

- Freil-pelegrin Y., Robledo D. Influence of alkali treatment on agar from gracilaria cornea from Yucatan, Mexico. J. Appl. Phycol. 1997;9:359–366. [Google Scholar]

- Ganesan M., Subba Rao P.V. Influence of post-harvest treatment on shelf life and agar quality in seaweeds Gracilaria edulis (Rhodophyta/Gigartinals) and Gelidiella acerosa (Rhophyta/Gelidiales) Indian J. Mar. Sci. 2004;33:269–275. [Google Scholar]

- Guiry M.D., Guiry G.M. National University of Ireland; Galway: 2021. AlgaeBase. World-wide Electronic Publication.http://www.algaebase.org searched on 16 November 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jaasund E. first ed. University of Tromsø; 1976. Intertidal Seaweeds in Tanzania. A Field Guide. [Google Scholar]

- Kappana A.N., Rao A.V. Preparation and properties of agar-agar from Indian seaweeds. Indian J. Technol. 1963;1:222–224. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V., Fotedar R. Agar extraction process for Gracilaria cliftonii (Withell, millar, & Kraft, 1994) Carbohydr. Polym. 2009;78:813–819. [Google Scholar]

- Lahaye M., Rochas C. Chemical structure and physico-chemical properties of agar. Hydrobiologia. 1991;221:137–148. [Google Scholar]

- Lahaye M., Yaphe W. Effect of season on the chemical structure and gel strength of Gracilaria pseudoverrucosa agar (Gracilariaceae, Rhodophyta) Carbohydr. Polym. 1988;8:285–301. [Google Scholar]

- Marinho-Soriano E. Agar polysaccharides from gracilaria species (Rhodophyta, gracilariaceae) J. Biotechnol. 2001;89:81–84. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1656(01)00255-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh D.J. Worldwide distribution of commercial resources of seaweeds including. Gelidium Hydrobiol. 1991;221:19–21. [Google Scholar]

- Radiah A., Misni S., Nazaruddin R., Norain Y., Adibi Rahiman M., Lyazzat B. A preliminary agar study on the agar content and agar gel strength of Gracilaria manilaensis using different extraction methods. World Appl. Sci. J. 2011;15:184–188. [Google Scholar]

- Ramavatar M., Kamalesh P., Ganesan M., Siddhanta A.K. Uperior quality agar from Gracilaria species (Gracilariales, Rhodophyta) collected from the gulf of Mannar, India. J. Appl. Phycol. 2008;20:397–402. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.