Summary

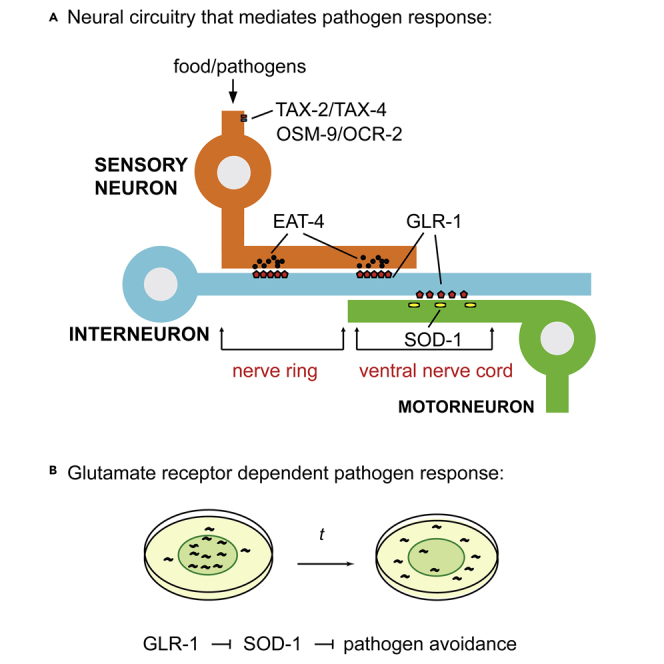

In Caenorhabditis elegans, sensory neurons mediate behavioral response to pathogens. However, how C. elegans intergrades these sensory signals via downstream neuronal and molecular networks remains largely unknown. Here, we report that glutamate transmission mediates behavioral plasticity to Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Deletion in VGLUT/eat-4 renders the mutant animals unable to elicit either an attractive or an aversive preference to a lawn of P. aeruginosa. AMPA-type glutamate receptor GLR-1 promotes the avoidance response to P. aeruginosa. SOD-1 acts downstream of GLR-1 in the cholinergic motor neurons. SOD-1 forms a punctate structure and is localized next to GLR-1 at the ventral nerve cord. Finally, single-copy ALS-causative sod-1 point mutation acts as a loss-of-function allele in both pathogen avoidance and glr-1 dependent phenotypes. Our data showed a link between glutamate signaling and redox homeostasis in C. elegans pathogen response and may provide potential insights into the pathology triggered by oxidative stress in the nervous system.

Subject areas: Cellular neuroscience, Microbiology parasite, Molecular microbiology, Molecular neuroscience

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

OSM-9/OCR-2 and TAX-2/TAX-4 mediate pathogen-induced behavioral response

-

•

Eat-4 mutant cannot distinguish whether Pseudomonas aeruginosa is attractive or repulsive

-

•

Glutamate receptor GLR-1 acts upstream of SOD-1 to promote pathogen avoidance

-

•

Single copy SOD-1(G85R) mutation elicits loss-of-function behavioral phenotypes

Cellular neuroscience; Microbiology parasite; Molecular microbiology; Molecular neuroscience

Introduction

Animals recognize and respond to chemical cues in their environment that represent food. The ability to distinguish hazardous food and to avoid pathogen infection confers survival (Reddy et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2005).

In the laboratory, Caenorhabditis elegans is often grown in a Petri dish that contains nonpathogenic bacteria, such as Escherichia coli OP50. When C. elegans is switched from a diet of E. coli to a diet of pathogenic P. aeruginosa, the animals will initially ingest P. aeruginosa but will start to avoid the P. aeruginosa lawn after several hours (Chang et al., 2011; Horspool and Chang, 2017, 2018; Meisel et al., 2014; Reddy et al., 2009). Sensory modalities, such as olfactory, chemosensory, and mechanosensory, are shown to play a role in regulating the host response (Chang et al., 2011; Foster et al., 2020; Horspool and Chang, 2017, 2018; Liu et al., 2016; Meisel et al., 2014; Sun et al., 2011). By ablating a specific neuron class, it has been shown that different sensory neurons may elicit opposite P. aeruginosa phenotypes. For example, mechanosensory neuron OLL inhibits, whereas chemosensory neuron ASJ promotes P. aeruginosa avoidance (Chang et al., 2011; Meisel et al., 2014). However, the downstream molecular and neuronal mechanisms to integrate these various sensory modalities triggered by P. aeruginosa remain largely unknown.

Glutamate is a key excitatory neurotransmitter in the vertebrate and invertebrate nervous systems (Curtis and Watkins, 1960; Wolstenholme, 1997). The glutamate vesicular transporter VGLUT confers the glutamatergic cell fate of a neuron (Serrano-Saiz et al., 2013, 2020). In C. elegans, eat-4 encodes a mammalian homolog of VGLUT (Lee et al., 1999). EAT-4 mediates glutamatergic transmission and controls distinct behaviors (Chalasani et al., 2007; Hart et al., 1999; Lee et al., 1999). Using EAT-4 as a reporter, a recent study identified 38 glutamatergic neuron classes (Serrano-Saiz et al., 2013). Sensory neurons that have been shown to mediate C. elegans response to pathogens, such as ADL, ASE, ASH, AWC, and OLL, are among those glutamatergic neuron classes identified (Chang et al., 2011; Foster et al., 2020; Horspool and Chang, 2017; Liu et al., 2016; Sun et al., 2011).

AMPA-type glutamate receptor subunits GluR1 and GluR2 contribute to synaptic plasticity and play a role in learning and memory (Lee et al., 2010). C. elegans GLR-1 and GLR-2 are the ortholog for mammalian GluR1 and GluR2 subunits (Brockie et al., 2001a). C. elegans AMPA receptors consist of a mixture of GLR-1 homomers and GLR-1/GLR-2 heteromers (Chang and Rongo, 2005). C. elegans glutamate receptor subunits are present in the command interneurons and fluorescently tagged versions of GLR-1 are localized to synapses along the ventral nerve cord (Brockie et al., 2001a; Rongo et al., 1998). GLR-1 mediates C. elegans locomotion (Brockie et al., 2001a; Hart et al., 1995; Maricq et al., 1995). A decrease in synaptic GLR-1 causes a reduction in spontaneous reversals (Brockie et al., 2001b; Maricq et al., 1995). Because many sensory neurons that detect pathogens also innervate GLR-1 interneurons, we speculate that GLR-1 may mediate C. elegans behavioral response to the pathogen P. aeruginosa.

Exposure to P. aeruginosa causes elevation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in C. elegans (Hoeven et al., 2011; Horspool and Chang, 2017). The ROS activates antioxidant enzyme expression, including superoxide dismutase SOD-1 (Horspool and Chang, 2017). SOD-1 is an enzyme that converts superoxide into less toxic hydrogen peroxide and oxygen (Muller et al., 2006; Oeda et al., 2001; Valentine et al., 2005). Animals carrying a sod-1 deletion elicit a hyper-avoidance response to P. aeruginosa (Horspool and Chang, 2017, 2018). It has been shown that SOD-1 functions in the gustatory neuron ASER to mediate pathogen avoidance. Based on an expression profile analysis, additional fluorescence signals of a SOD-1 reporter are present at the ventral nerve cord (Horspool and Chang, 2017). This suggests SOD-1 may be expressed in the motor and/or interneurons in C. elegans.

Since the discovery of SOD-1 as the first genetic link to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) (Rosen et al., 1993; Siddique et al., 1991), the analyses using patient-derived SOD-1 mutant overexpression animal models have shown that the disease causative alleles, such as sod-1(G85R) and sod-1(G93A), are dominant gain-of-function mutations (Bruijn et al., 1997, 1998; Tu et al., 1996). These overexpression models can recapitulate the motor neuron degenerative aspect in ALS pathogenesis. This suggests that SOD-1 is critical to cholinergic motor neuron's physiological function.

In addition, excitatory glutamatergic transmission plays a key role in regulating neural oxidative stress (Carriedo et al., 2000; Sattler and Tymianski, 2001). In a murine model, blockade of the AMPA-type glutamate receptor prevented death of the motor neurons which contain heterologous expression of an ALS SOD-1 mutation (Roy et al., 1998). In C. elegans, mutations in endogenous sod-1 loci trigger the death of glutamatergic neurons (Baskoylu et al., 2018). These aforementioned results prompted us to investigate the interactions of GLR-1 and SOD-1 in the context of pathogen-induced neuronal and behavioral mechanisms in C. elegans.

In this study, we examined the role of the TRPV channel (OSM-9/OCR-2) and the nucleotide-gated channel (TAX-2/TAX-4) in the pathogen-induced behavioral response. The TRPV channel (OSM-9/OCR-2) and the nucleotide-gated channel (TAX-2/TAX-4) are the key players in sensory signal transduction (Bargmann and Kaplan, 1998). We found the TRPV channel and the cyclic nucleotide-gated channel play opposite roles to mediate the pathogen-induced behavioral response. Animals that lack the vesicular glutamate transporter VGLUT EAT-4 elicit a prolonged 50% P. aeruginosa lawn occupancy phenotype. This is presumably because of the elimination of both attractive and aversive signals originating from the sensory system. The AMPA-type ionotropic glutamate receptor GLR-1 promotes C. elegans avoidance response to P. aeruginosa. SOD-1 is found at the synapses and in the cell body of cholinergic motor neurons. Motor neuron-specific SOD-1 is localized next to interneuron-derived GLR-1 at the ventral nerve cord. Our genetic and neuron circuitry analyses suggest that SOD-1 functions downstream of GLR-1. Finally, we hypothesize that SOD-1 may regulate synaptic GLR-1 via a possible feedback loop.

Results

The TRPV channel and the cyclic nucleotide-gated channel mediate opposite behavioral responses to P. aeruginosa

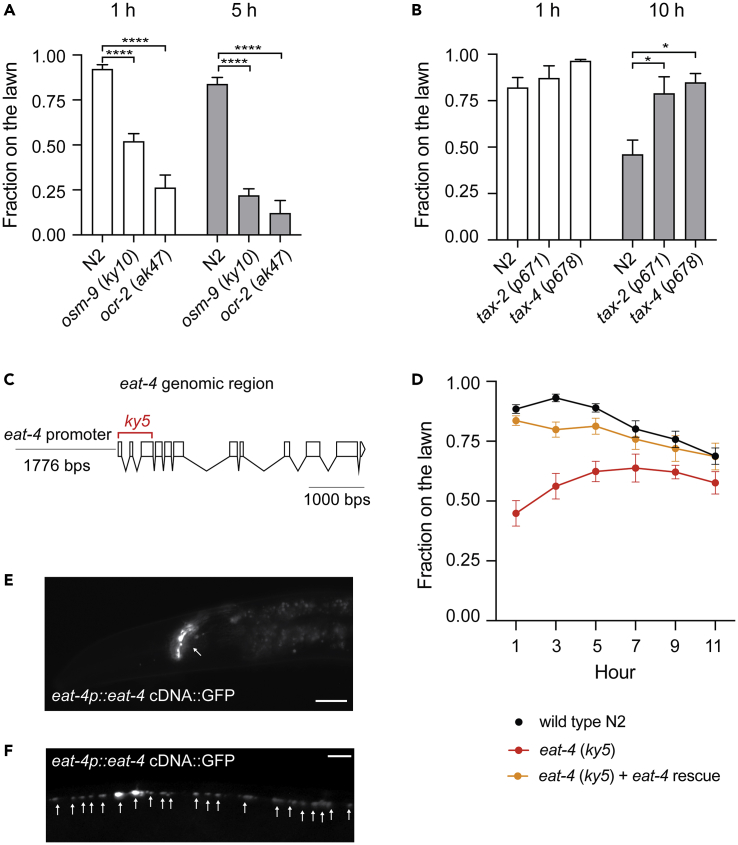

We began our study by testing the loss of function mutants of osm-9 (ky10), ocr-2 (ak47), tax-2 (p671), and tax-4 (p678). OSM-9 and OCR-2 are transient receptor potential (TRP) channels in C. elegans and act in chemosensation, osmosensation, and mechanosensation. TAX-2 and TAX-4 form the cyclic nucleotide-gated channel and are required for olfaction, taste, and thermosensation (Mori, 1999). We transferred the aforementioned mutant animals to a Petri dish that contained a lawn of P. aeruginosa. Initially, osm-9(ky10), ocr-2(ak47), tax-2(p671), and tax-4(p678) were attracted to the lawn of P. aeruginosa like wild-type. Within the first 15 min, most of the mutant and wild-type animals found the P. aeruginosa lawn (data not shown). At 1 and 5 h, osm-9(ky10) and ocr-2(ak47) mutant animals displayed heightened P. aeruginosa lawn avoidance phenotypes compared to wild-type N2 (Figure 1A). In contrast, tax-2(p671) and tax-4(p678) animals showed delayed pathogen lawn avoidance phenotypes (Figure 1B). These results suggest the TRPV channel OSM-9/OCR-2 inhibits, whereas the cyclic nucleotide-gated channel TAX-2/TAX-4 promotes C. elegans avoidance of P. aeruginosa. This also indicates that different sensory inputs play antagonistic roles in modulating C. elegans response to P. aeruginosa.

Figure 1.

Glutamate transmission mediates C. elegans behavioral response to P. aeruginosa PA14

(A–B) Sensory signal transduction plays antagonistic roles in regulating C. elegans behavioral response to P. aeruginosa PA14. (A) osm-9 (ky10) and ocr-2 (ak47) mutants elicit heightened avoidance responses to a lawn of P. aeruginosa PA14, (B) tax-2 (p671) and tax-4(p678) mutants elicit delayed avoidance responses to a lawn of P. aeruginosa PA14. (A–B) Error bar represents SEM ∗ represents p < 0.05. ∗∗∗∗ represents p < 0.0001. As determined by one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison analysis. N = 10.

(C) Scheme of the eat-4 genomic region. The deleted region in eat-4(ky5) mutant is indicated in red.

(D) Time course experiments of pathogen avoidance response of wild type N2, eat-4(ky5) and eat-4(ky5) + eat-4 rescue. At 5h, N2 verses eat-4(ky5) is p < 0.0001. At 7h, N2 verses eat-4(ky5) is p < 0.001. Both at 5 and 7h, N2 verses eat-4(ky5) + eat-4 rescue is not significant, as determined by one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison analysis. N = 12.

(E–F) Fluorescence micrographs of eat-4p:eat-4:GFP in eat-4 (ky5) background. Punctate GFP signals are present in the nerve ring (E) and along the ventral nerve cord (F). Scale bar indicates 10 μm in (E) and 20 μm in (F)

Glutamate transmission mediates the behavioral response to P. aeruginosa

Previous works have shown that osm-9, ocr-2, tax-2, and tax-4 are expressed in overlapping sensory neurons, including AWA, AWB, AWC, ASE, ASH, ASI, ASJ, and ADL (Coburn and Bargmann, 1996; Colbert et al., 1997; Komatsu et al., 1996; Tobin et al., 2002). In addition, vesicular glutamate transporter VGLUT EAT-4 is expressed in ADL, ASE, ASH, AWC, and OLL sensory neurons (Serrano-Saiz et al., 2013). These aforementioned sensory neurons regulate nematode's responses to commensal and pathogenic microbes (Chang et al., 2011; Foster et al., 2020; Horspool and Chang, 2017; Horspool and Chang, 2018; Liu et al., 2016, O'donnell et al., 2020). To explore whether glutamate signaling mediates the behavioral response to pathogenic microbes, we exposed eat-4(ky5) mutant animals to a lawn of P. aeruginosa and observed their behavior over time. Based on DNA sequence analysis, the eat-4(ky5) deletion allele eliminates the first three exons of eat-4 (Figure 1C). Therefore, eat-4(ky5) is likely acting as a null mutation. We found eat-4(ky5) animals displayed ∼50% pathogen lawn occupancy throughout the duration of our experiments (Figure 1D red). In comparison, wild-type animals initially remained inside the bacterial lawn, fed on P. aeruginosa, and started to vacate the lawn at 7 h (Figure 1D black). We could rescue the eat-4(ky5) phenotype by introducing a transgene that contains eat-4p:EAT-4:GFP (Figure 1D orange). A lack of change in the proportions of the experimental animals that move onto versus out of the P. aeruginosa lawn over time suggests that eat-4(ky5) animals were unable to distinguish whether the P. aeruginosa lawn was attractive or repulsive. This indicates that glutamatergic transmission plays a key role in regulating C. elegans response to P. aeruginosa.

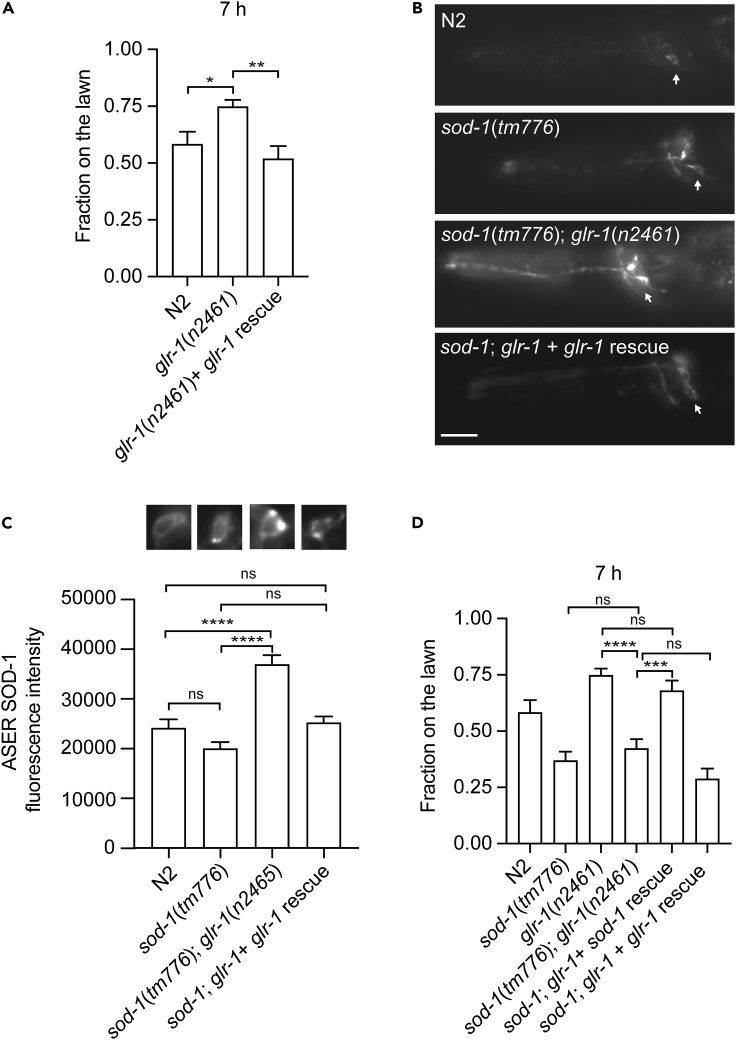

AMPA-type ionotropic glutamate receptor GLR-1 promotes avoidance of P. aeruginosa

Because GFP-labeled EAT-4 forms a punctate structure at the nerve ring and ventral nerve cord (Figures 1E–1F) and EAT-4 mediates the behavioral response to P. aeruginosa, we decided to test whether the AMPA-type ionotropic glutamate receptor GLR-1 regulates C. elegans behavioral response to P. aeruginosa. The AMPA-type ionotropic glutamate receptor GLR-1 is the mammalian homolog of GluR1 in C. elegans (Hart et al., 1995; Maricq et al., 1995) and is expressed in a subset of command interneurons (Brockie et al., 2001a; Rongo et al., 1998). We exposed loss-of-function glr-1(n2461) to P. aeruginosa and found that glr-1(n2461) elicited a delayed response to P. aeruginosa compared to wild-type N2. This delayed response of glr-1(n2461) could be rescued by a glr-1 genomic fragment (Figure 2A). This suggests that the AMPA-type ionotropic glutamate receptor GLR-1 promotes C. elegans avoidance response to P. aeruginosa.

Figure 2.

AMPA-type glutamate receptor promotes C. elegans avoidance response to P. aeruginosa PA14

(A) glr-1(n2461) mutant animals elicit delayed avoidance responses to a lawn of P. aeruginosa PA14. The delayed behavioral response of glr-1(n2461) can be rescued by a construct that contains glr-1p:glr-1:GFP. Error bar represents SEM ∗ represents p < 0.05. ∗∗ represents p < 0.01 As determined by one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison analysis. N = 12.

(B) Fluorescence micrographs of sod-1p:sod-1:mRFP transgenic animals in wild type N2, sod-1(tm776), sod-1(tm776); glr-1(n2461), and sod-1(tm776); glr-1(n2461) + glr-1 rescue backgrounds. Arrow indicates ASER neuron. Anterior is to the left. Dorsal is at the top. Scale bar indicates 10 μm.

(C) SOD-1 expression is elevated in the ASER neuron in glr-1(n2461) background. Error bar represents SEM ∗∗∗∗ represents p < 0.0001. ns represents not significant. As determined by one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey's multiple comparison analysis. N = 34.

(D) sod-1(tm776); glr-1(n2461) mutant animals show a similar pathogen avoidance response to sod-1(tm776) single mutant. The avoidance response of sod-1(tm776); glr-1(n2461) double mutant can be rescued by the sod-1p::sod-1::GFP but not by the glr-1p:glr-1:GFP. Error bar represents SEM ∗∗∗ represents p < 0.001. ∗∗∗∗ represents p < 0.0001. ns represents not significant. As determined by one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey's multiple comparison analysis. N = 9.

GLR-1 inhibits superoxide dismutase SOD-1 expression

Previous work has shown that superoxide dismutase is expressed in the gustatory neuron ASER. An increase in ASER SOD-1 expression inhibits P. aeruginosa lawn leaving behavior (Horspool and Chang, 2017, 2018). We introduced glr-1(n2461) into the sod-1(tm776), sod-1p:SOD-1:mRFP background. We found that the overall fluorescence signals of SOD-1:mRFP were elevated in the glr-1(n2461) background (Figure 2B). In addition, the average fluorescence signals of SOD-1:mRFP in the ASER neuron were elevated in glr-1(n2461) mutant (Figure 2C). We were able to rescue the elevation of fluorescence signals of SOD-1:mRFP in glr-1(n2461) mutant back to the wild type level via a transgene that contains glr-1p:GLR-1:GFP (Figures 2B–2C). Together, this suggests that GLR-1 inhibits SOD-1 expression in C. elegans.

SOD-1 acts downstream of GLR-1 to inhibit the pathogen avoidance response

Data from recent studies suggest that SOD-1 inhibits the pathogen avoidance response (Horspool and Chang, 2017, 2018). In contrast, GLR-1 promotes the behavioral response to P. aeruginosa (Figure 2A). We further tested if sod-1 mutation can reverse the delayed behavioral phenotype of glr-1(n2461) or vice versa. At 7 h, we found that sod-1(tm776); glr-1(n2461) double mutant animals displayed a heightened pathogen avoidance phenotype that was similar to the sod-1(tm776) single mutant. The pathogen avoidance phenotype of sod-1(tm776); glr-1(n2461) double mutant animals could be rescued back to glr-1(n2461) single mutant level by a transgene that contained sod-1p:SOD-1:mRFP (Figure 2D). Our results suggest that GLR-1 functions upstream of SOD-1 to mediate P. aeruginosa avoidance.

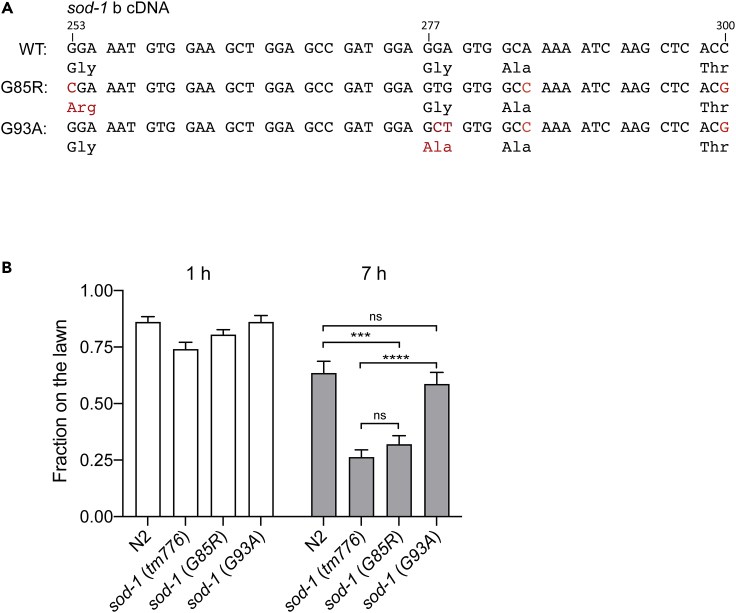

ALS-related point mutation sod-1 (G85R) elicits the loss-of-function phenotype in pathogen avoidance

Mutations in SOD-1 are linked to the familial form of ALS. Based on studies in mammalian systems, many of the common ALS disease causative alleles such as sod-1(G85R) and sod-1(G93A) are dominant gain-of-function mutations (Bruijn et al., 1997; Tu et al., 1996). In C. elegans, the loss-of-function sod-1(tm776) deletion allele elicits a heightened pathogen avoidance phenotype (Figure 2D). Therefore, we hypothesize that sod-1(G85R) and sod-1(G93A) mutants may have a delayed pathogen avoidance phenotype that is similar to glr-1(n2461). We obtained C. elegans single-copy sod-1(G85R) and single-copy sod-1(G93A) mutations generated via the CRISPR/CAS9 technique (Figure 3A) and performed the pathogen avoidance assay. Intriguingly, neither sod-1(G85R) nor sod-1(G93A) elicited delayed P. aeruginosa avoidance. In contrast, sod-1(G85R) has a P. aeruginosa avoidance phenotype that is similar to sod-1(tm776) deletion. In addition, sod-1(G93A) has a P. aeruginosa avoidance response that is similar to wild-type (Figure 3B). These results suggest that in the context of P. aeruginosa avoidance, neither sod-1(G85R) nor sod-1(G93A) is the dominant gain-of-function allele.

Figure 3.

sod-1(G85R) mutant elicits pathogen avoidance response similar to sod-1(tm776) deletion

(A) Sequences of ALS-related mutations sod-1(G85R) and sod-1(G93A) in C. elegans. sod-1(G85R) and sod-1(G93A) are generated via the CRISPR/CAS9 technique. The corresponding DNA sequence is based on the cDNA isoform b of sod-1.

(B) Pathogen avoidance phenotypes of sod-1(G85R) and sod-1(G93A). Error bar represents SEM ∗∗∗ represents p < 0.001. ∗∗∗∗ represents p < 0.0001. ns represents not significant. As determined by one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey's multiple comparison analysis. N = 12.

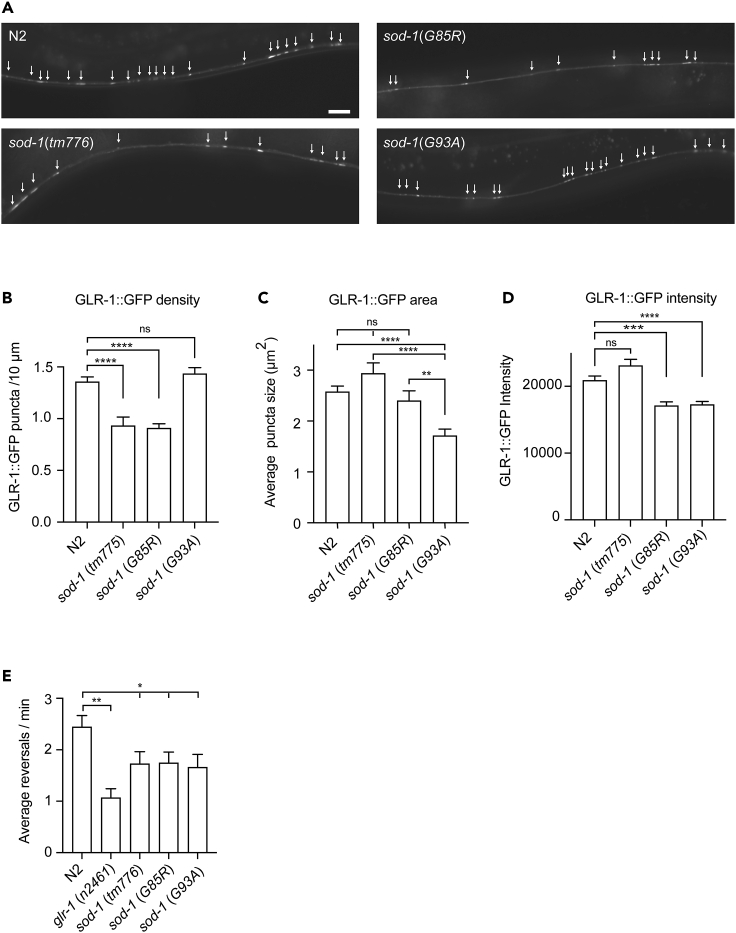

SOD-1 regulates the AMPA-type ionotropic glutamate receptor GLR-1 at the ventral nerve cord

The GFP-labeled AMPA-type glutamate receptor GLR-1 is located at the synapses along the ventral nerve cord (Rongo et al., 1998). To determine whether SOD-1 plays a role in regulating synaptic GLR-1, we crossed sod-1(tm776), sod-1(G85R), and sod-1 (G93A) mutants with animals that contained the integrated glr-1p:GLR-1:GFP transgene. We then measured the density, area, and intensity of GLR-1:GFP at the ventral nerve cord (Figures 4A–4D). We found that in sod-1(tm776) and sod-1 (G85R) backgrounds, the density of tagged GLR-1 along the ventral nerve cord was reduced (Figure 4B). In addition, the sod-1(G93A) mutant allele elicited a reduction of GLR-1:GFP size (Figure 4C). Both ALS causative sod-1(G85R) and sod-1(G93A) mutant alleles elicited reduced fluorescence intensity (Figure 4D). These results indicate that SOD-1 regulates glutamate receptor GLR-1 synaptic localization at the ventral nerve cord.

Figure 4.

SOD-1 plays a role in regulating synaptic GLR-1 at the ventral nerve cord

(A) Fluorescence micrographs of glr-1p:glr-1:GFP in wild-type N2, sod-1(tm776), sod-1(G85R) and sod-1(G93A) backgrounds. Arrow indicates GLR-1:GFP puncta. Scale bar indicates 10 μm.

(B) sod-1(tm776) and sod-1(G85R) mutant animals have reduced GLR-1:GFP density as compared to wild type.

(C) sod-1(G93A) mutant animals have reduced GLR-1:GFP area as compared to wild type.

(D) sod-1(G85R) and sod-1(G93A) mutant animals have reduced GLR-1:GFP fluorescence intensity as compared to wild type. (B–D) Error bar represents SEM ∗∗∗ represents p < 0.001. ∗∗∗∗ represents p < 0.0001. ns represents not significant. As determined by one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey's multiple comparison analysis. N = 24.

(E) sod-1(tm776), sod-1(G85R) and sod-1(G93A) mutants elicit reduced spontaneous reversal phenotypes. Error bar represents SEM ∗ represents p < 0.05, ∗∗ represents p < 0.01, as determined by Student’s t test. N = 12.

Glutamate receptor GLR-1 mediates spontaneous reversal movement when food is present (Brockie et al., 2001b; Maricq et al., 1995). The reduction in GFP-labeled GLR-1 in sod-1(tm776), sod-1 (G85R), and sod-1(G93A) backgrounds prompted us to further examine whether these mutant alleles may elicit spontaneous reversal defects. Indeed, after being transferred to a Petri dish with a thin layer of E. coli OP50, sod-1(tm776), sod-1 (G85R), and sod-1(G93A) mutant animals showed a reduction in spontaneous reversal frequency (Figure 4E). Because sod-1(G85R) and sod-1(G93A) elicited phenotypes that are similar to sod-1(tm776) deletion, this suggests that ALS causative point mutations sod-1(G85R) and sod-1(G93A) are likely loss-of-function alleles of sod-1.

SOD-1 is found adjacent to GLR-1 at the ventral nerve cord

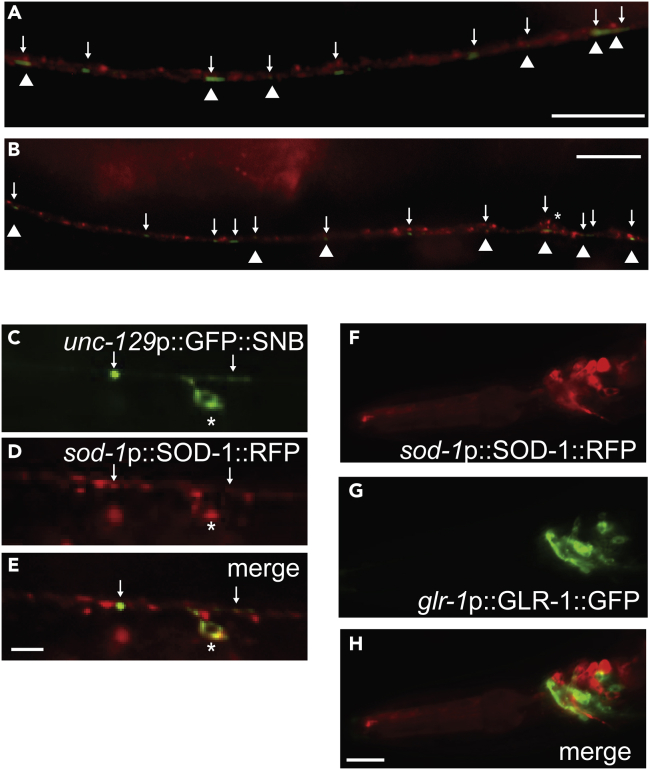

Because SOD-1 plays a role in regulating synaptic GLR-1 (Figures 4A–4D), we decided to test whether SOD-1 is localized near GLR-1 at the ventral nerve cord. We introduced the sod-1p:SOD-1:mRFP transgene into the glr-1p:GLR-1:GFP background and observed the fluorescence signals of GFP and RFP. We found that SOD-1:mRFP forms distinct puncta along the ventral nerve cord (Figures 5A–5B red). Some of these SOD-1:mRFP puncta are adjacent to GLR-1:GFP (Figures 5A–5B triangle). In addition, signals of SOD-1:mRFP were present in neuron cell bodies near the ventral nerve cord (Figure 5B star). These results indicate that SOD-1 is partially localized next to GLR-1 at the ventral nerve cord.

Figure 5.

SOD-1 is present in the cholinergic motor neurons and at the ventral nerve cord

(A–B) SOD-1:mRFP (red) and GLR-1:GFP (green and arrow) are found along the ventral nerve cord. SOD-1:mRFP and GLR-1:GFP localize adjacent to each other (triangle). In (B). ∗ represents SOD-1 positive neuron cell body near the ventral nerve cord. Scale bar indicates 10 μm. (C–E) SOD-1 is present in cholinergic motor neurons.

(C) unc-129p:GFP:SNB.

(D) sod-1p:SOD-1:mRFP.

(E) merge of (C) and (D). ∗ indicates neuron cell body. Arrow represents puncta of GFP:SNB that overlaps with SOD-1:mRFP. Bar: 2 μm.

(F–H) SOD-1 is present in the neuron cells that do not confer GLR-1 expression in the head region. (F) sod-1p:SOD-1:mRFP. (G) glr-1p:GLR-1:GFP. (H) Merge of (F) and (H). Bar: 5 μm.

SOD-1 is present in cholinergic motor neurons

To identify the SOD-1:mRFP positive neurons near the ventral nerve cord, we crossed sod-1p:SOD-1:mRFP into the cholinergic neuron reporter unc-129p:GFP:SNB. Reporter unc-129p:GFP:SNB confers expression of synaptobrevin in the cell body and at the synapses of DA and DB cholinergic neurons (Ch'ng et al., 2008). We found that SOD-1:mRFP signals overlap with GFP:SNB signals in the cell bodies of DA and DB neurons (Figures 5C–5E star). In addition, some of SOD-1:mRFP puncta were adjacent to the GFP:SNB puncta at the synapses along the ventral nerve cord (Figures 5C–5E arrow). This indicates that SOD-1 is present in DA and DB cholinergic motor neurons.

SOD-1 interacts with GLR-1 non-cell autonomously

GLR-1 is expressed in command interneurons, which include AVA, AVB, AVD, and AVE. These interneurons innervate DA and DB motor neurons with chemical synapses or gap junctions. The expression profile analysis of SOD-1 suggests that SOD-1 may function in the cholinergic motor neurons (Figures 5C–5E), which are downstream targets of GLR-1 interneurons. This correlates with our genetic epistasis analysis that sod-1 is acting downstream of glr-1 (Figure 2D). However, the aforementioned results do not rule out the possibility that SOD-1 and GLR-1 are present in the same neuron cells. Therefore, we performed co-localization analysis using animals that contained both sod-1p:SOD-1:mRFP and glr-1p:GLR-1:GFP transgenes with a focus on command interneurons in the head region. We found that, like in previous reports, SOD-1 is present in amphid sensory neurons ASK, ASI, ADL, and ASER. However, SOD-1:mRFP signals are not present in GLR-1:GFP positive interneurons (Figures 5F–5H). These neural expression profile analyses suggest that the interactions of SOD-1 and GLR-1 are non-cell autonomous.

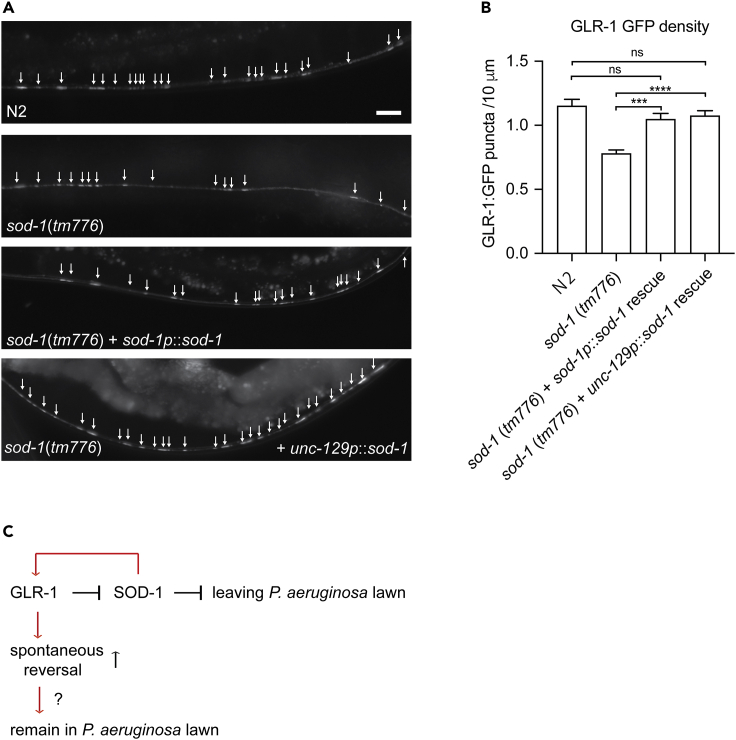

Motor neuron specific SOD-1 modulates synaptic GLR-1

To determine whether SOD-1 functions in cholinergic motor neurons to modulate glutamate receptors at the ventral nerve cord, we performed rescue experiments using cholinergic motor neuron promoter unc-129p to drive the expression of SOD-1. Expression of SOD-1 in DA and DB motor neurons rescues the GLR-1:GFP density phenotype in sod-1(tm776) deletion (Figures 6A–6B). This result suggests a possible motor neuron specific and SOD-1 dependent feedback mechanism to modulate glutamate receptor synaptic localization.

Figure 6.

Motor neuron-specific SOD-1 modulates the density of glutamate receptor at the ventral nerve cord

(A) Fluorescence micrographs of glr-1p:glr-1:GFP in wild-type N2, sod-1(tm776), sod-1(tm776) + sod-1p:sod-1:mRFP and sod-1(tm776) + unc-129p:sod-1:mRFP backgrounds. Arrow indicates GLR-1:GFP puncta. Scale bar indicates 10μm.

(B) Cholinergic motor neuron expression of SOD-1 rescues the GLR-1:GFP density phenotype of sod-1(tm776) deletion. Error bar represents SEM ∗∗∗ represents p < 0.001. ∗∗∗∗represents p < 0.0001. ns represents not significant. As determined by one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey's multiple comparison analysis. N = 20.

(C) AMPA-type glutamate receptor GLR-1 promotes C. elegans avoidance response to P. aeruginosa PA14 via inhibition to SOD-1. SOD-1 modulates synaptic GLR-1 density at the ventral nerve cord and plays a role in glr-1 dependent spontaneous reversal.

Together, our results showed that the TRPV channel (OSM-9/OCR-2) and the cyclic nucleotide-gated channel in the sensory system elicit antagonistic effects on C. elegans pathogen avoidance response. The lack of vesicular glutamate transporter EAT-4 renders the worm unable to distinguish the P. aeruginosa lawn. This demonstrates that glutamate transmission plays a key role in mediating behavioral plasticity to pathogens. We found that the AMPA-type ionotropic glutamate receptor GLR-1 promotes C. elegans avoidance response to P. aeruginosa via the inhibition of SOD-1. SOD-1 is expressed at the synapses and in the cell body of cholinergic motor neurons. SOD-1 is partially localized next to GLR-1 at the ventral nerve cord. Finally, SOD-1 modulates synaptic GLR-1 non-cell autonomously, possibly via a feedback loop to fine-tune the GLR-1 dependent response (Figure 6C).

Discussion

The data presented here established that glutamate transmission plays a key role in integrating sensory signals and mediating the pathogen response. Our results indicate that TRPV channel mutants (osm-9/ocr-2) and cyclic nucleotide-gated channel mutants (tax-2/tax-4) showed different behavioral responses to P. aeruginosa. Many sensory neurons that express OSM-9/OCR-2 and/or TAX-2/TAX-4 are glutamatergic (Figures 1A–1B). Therefore, we examined the role of vesicular glutamate transporter EAT-4 in C. elegans behavioral response to P. aeruginosa. A deletion in eat-4 completely abolished the nematode's ability to display an initial preference for P. aeruginosa, followed by the subsequent aversive response after prolonged pathogen exposure (Figure 1D). Our results suggest OSM-9 and OCR-2 play a role in the initial food attraction and/or in retention of animals on the bacterial food. In contrast, TAX-2 and TAX-4 may mediate signaling that is responsible for P. aeruginosa avoidance. We reasoned that the 50% P. aeruginosa lawn occupancy phenotype of eat-4 deletion is likely because of the elimination of sensory integration caused by a failure in glutamate transmission.

Glutamate receptor GLR-1 is present in command interneurons and is therefore hypothesized to act downstream of EAT-4 (Chalasani et al., 2007; Hart et al., 1999). GLR-1 mediates spontaneous reversal movement. We found that glr-1 mutant elicited a delayed response to P. aeruginosa (Figure 2A). Because sod-1 mutant animals showed a heightened behavioral response to P. aeruginosa, we introduced sod-1 into the glr-1 background and performed genetic epistasis experiments. The sod-1; glr-1 double mutant showed a phenotype that is similar to the sod-1 single mutant. Most importantly, we were able to rescue the sod-1; glr-1 double mutant phenotype back to the glr-1 single mutant level using a sod-1 fragment (Figure 2D). In addition, SOD-1 is present in the DA and DB cholinergic motor neurons (Figure 5). GLR-1 positive command interneurons innervate DA and DB motor neurons. We found that SOD-1 is localized adjacent to GLR-1 at the ventral nerve cord (Figures 5A–5B). Finally, the overall expression of SOD-1:mRFP is elevated in the glr-1 mutant background (Figures 2B–2C). Together, these aforementioned results suggest that glr-1 likely functions upstream of sod-1 by inhibiting SOD-1 to promote pathogen avoidance.

Mutations in sod-1 are linked to the familial form of ALS (Rosen et al., 1993; Gurney et al., 1994; Deng et al., 1993). Based on observations using transgenic SOD-1 overexpression models, ALS-causative alleles such as sod-1(G85R) and sod-1(G93A) are considered as dominant gain-of-function missense mutations.

We originally thought that sod-1(G85R) and sod-1(G93A) were the gain-of-function mutations of sod-1 in C. elegans. Instead, we discovered that sod-1(G85R) acts as a loss-of-function mutant in both pathogen avoidance and the glr-1-dependent behavioral response (Figures 3B and 4E). Although we did not find that sod-1(G93A) alters the pathogen avoidance response, animals carrying sod-1(G93A) also showed a loss of function in glr-1 dependent locomotion.

Based on the analyses of synaptic GLR-1:GFP, both sod-1(tm776) and sod-1(G85R) animals showed a reduction in GLR-1:GFP density at the ventral nerve cord (Figure 4B). In contrast, the density of GLR-1:GFP of sod-1(G93A) animals remains similar to wild type. This may explain the differences in pathogen avoidance response of ALS-causative sod-1(G85R) and sod-1(G93A) alleles.

Both sod-1(G85R) and sod-1 (G93A) elicited defects in GLR-1 synaptic targeting (Figures 4B–4D). One possible explanation is that the loss-of-function effects of sod-1(G85R) and sod-1(G93A) are masked by the overexpression in transgenic animal models. Because the sod-1(G85R) and sod-1(G93A) mutations were generated using the CRISPR/CAS9 technique by modifying the endogenous sod-1 coding sequence, this allows us to reveal the loss-of-function aspects of these ALS-causative sod-1 alleles.

Together, our results demonstrate that glutamate transmission integrates sensory cues and mediates the pathogen response. The genetic and neuronal circuitry analyses of GLR-1 and SOD-1 reveal a sophisticated mechanism for fine-tuning behavioral plasticity amid pathogen-induced oxidative stress. Our findings may provide conserved mechanisms across different species and insights into the nature of ALS-causative mutations.

Limitations of the study

Our genetic and neural circuitry analyses reveal that glutamate signaling modulates C. elegans behavioral plasticity to pathogens. Our results suggest superoxide dismutase SOD-1 acts in the motor neuron downstream of GLR-1 to inhibit P. aeruginosa avoidance. In addition, ALS causative alleles of SOD-1 act as loss-of-function mutations in C. elegans. Future studies designed to directly measure neural physiology may further corroborate our results.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14 | Ausubel Lab | WB Cat# WBStrain00041978 |

| Escherichia coli OP50 | CGC | WB Cat# WBStrain00041969 |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| C. elegans: Strain: N2 | CGC | WB Cat# WBStrain00000001 |

| C. elegans: Strain: GA187 sod-1(tm776) | CGC | WB Cat# WBStrain00007662 |

| C. elegans: Strain: KP3 glr-1(n2461) | CGC | WB Cat# WBStrain00023619 |

| C. elegans: Strain: MT6304 eat-4(ky5) | CGC | WB Cat# WBStrain00027259 |

| C. elegans: Strain: CX4544 ocr-2(ak47) | CGC | WB Cat# WBStrain00040166 |

| C. elegans: Strain: CX10 osm-9(ky10) | CGC | WB Cat# WBStrain00005214 |

| C. elegans: Strain: PR671 tax-2(p671) | CGC | WB Cat# WBStrain00030780 |

| C. elegans: Strain: PR678 tax-4(p678) | CGC | WB Cat# WBStrain00022726 |

| C. elegans: Strain: HCX1089 eat-4(ky5) bosEx1089[eat-4p::eat-4cDNA::eGFP, unc-122p::mcherry+] | This study | N/A |

| C. elegans: Strain: HCX1052 glr-1(n2461); nuIs25 | This study | N/A |

| C. elegans: Strain: HCX847 bosIs847[sod-1p::sod-1cDNA::mstrawberry, unc-122p::GFP+] 4x backcross | This study | N/A |

| C. elegans: Strain: HCX858 sod-1(tm776); bosIs847 [sod-1p::sod-1cDNA::mstrawberry, unc-122p::GFP+] | This study | N/A |

| C. elegans: Strain: HCX949 sod-1(tm776); glr-1(n2461); bosIs847[sod-1p::sod-1cDNA::mstrawberry, unc-122p::GFP+] | This study | N/A |

| C. elegans: Strain: HCX934 sod-1(tm776); glr-1(n2461) | This study | N/A |

| C. elegans: Strain: HCX1004 sod-1(tm776); glr-1(n2461); nuIs25 | This study | N/A |

| C. elegans: Strain: HCX978 sod-1(G85R) 6x backcross from HA3299 | This study | N/A |

| C. elegans: Strain: HCX942 sod-1(G93A) 6x backcross from HA2987 | This study | N/A |

| C. elegans: Strain: HCX404 sod-1(tm776); nuIs25 | This study | N/A |

| C. elegans: Strain: HCX916 sod-1(G85R); nuIs25 | This study | N/A |

| C. elegans: Strain: HCX919 sod-1(G93A); nuIs25 | This study | N/A |

| C. elegans: Strain: HCX923 nuIs25 [glr-1p::glr-1::GFP] 4x backcross from KP1148 | This study | N/A |

| C. elegans: Strain: HCX408 sod-1(tm776); nuIs25; bosIs847[sod-1p::sod-1cDNA::mstrawberry, unc-122p::GFP+] | This study | N/A |

| C. elegans: Strain: HCX1015 nuIs152 [unc-129p::GFP::SNB]; bosIs847[sod-1p:sod-1cDNA:mstrawberry, unc-122p::GFP+] | This study | N/A |

| C. elegans: Strain: HCX1371 sod-1(tm776); glr-1(n2461); nuIs25; bosIs847[sod-1p:sod-1cDNA:mstrawberry, unc-122p::GFP+] | This study | N/A |

| C. elegans: Strain: HCX1376 sod-1(tm776); nuIs25; Ex1376 [unc-129p::sod-1cDNA::mScarlet, unc-122p::mcherry+] | This study | N/A |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| eat-4 promoter PCR forward primer 5′- TGCCTGGCGCCCCC CATATCTC − 3′ |

IDT | N/A |

| eat-4 promoter PCR reverse primer 5′-GATGATGATGATGAT GGAGTTGTTGTAAGAGGAAGG − 3′ |

IDT | N/A |

| sod-1 promoter PCR forward primer 5′-GAACACCAAA CCGGACTGACCAAGT-3′ |

IDT | N/A |

| sod-1 promoter PCR reverse primer 5′-CAAAGTTGTA GATTCAGTATTTTAGATCGGTG-3′ |

IDT | N/A |

| unc-129 promoter PCR forward primer 5′-CATGTCTTT TTACCTCTTTTGGCATGTACCGTTCTTC-3′ |

IDT | N/A |

| unc-129 promoter PCR reverse primer 5′-GGGATCAAACAAATAAGATGCGGAGTTTCTCAAATAG-3′ | IDT | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pUC57 mini GFP | This study | N/A |

| pUC57 simple eat-4 cDNA | This study | N/A |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| GraphPad Prism 9.0 | GraphPad Prism Software, Inc | https://www.graphpad.com/ |

| MetaMorph | Molecular Devices | https://www.moleculardevices.com/ |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Howard C. Chang (changh@rowan.edu).

Materials availability

The C. elegans strains and DNA plasmids generated in this study will be shared upon request or from the C. elegans Genetics Center. We may require a payment to cover shipping and a completed Materials Transfer Agreement if there is potential for commercial application.

Experimental model and subject details

C. elegans strains were maintained at 20 °C using standard methods (Brenner, 1974). Strains were maintained at 20 °C, then shifted to 22.5 °C for P. aeruginosa lawn avoidance assays. All mutant strains used in this study, including sod-1(tm776), sod-1(G85R), sod-1(G93A), eat-4(ky5), glr-1(n2461), osm-9 (ky10), ocr-2 (ak47), tax-2 (p671), and tax-4 (p678), were obtained from the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center and backcrossed six times to N2 prior to analysis. KP1148 nuIs25 glr-1p:GLR-1:GFP and KP3814 nuIs152 unc-129p:GFP:SNB were also obtained from the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center. KP1148 nuIs25 and HCX847 bosIs847 were backcrossed four times before being crossed into sod-1 and glr-1 mutant strains. Transgenic strains were isolated by microinjecting plasmids (typically at 100–150 μg/mL), together with one of the following co-injection markers—unc-122p::GFP or unc-122p::mcherry—in wild-type or mutant animals. UV integration of the extrachromosomal array was performed following the protocol originated by S. Mitani (Kage-Nakadai et al., 2014). The integrated lines were then backcrossed six times to N2 prior to the analysis.

Method details

P. aeruginosa avoidance assay

A 100 mL solution of LB was inoculated with a single colony of P. aeruginosa PA14 and grown overnight without shaking at 22.5 °C for 48 h until O.D. reached 0.2–0.3. 30 μL of this culture was used to seed the center of the 100 mm NGM plate. Seeded plates were incubated for 24 h at room temperature (22.5 °C) prior to the experiment. Approximately 30 animals (young adults) were transferred onto plates containing the P. aeruginosa PA14 lawn at 22.5 °C, and lawn occupancy was measured at the indicated times. Three plates of each genotype were used in each experiment, and all experiments were performed at least three times. Upon being transferred to the P. aeruginosa–containing plates, animals explored the plate for about 10–15 min until they found the bacterial lawn and then remained on the lawn. Subsequently, lawn occupancy was measured over time as the lawn avoidance behavior was observed (Chang et al., 2011).

Molecular cloning

The promoter region of eat-4 was amplified by PCR using primers 5′- TGCCTGGCGCCCCCCATATCTC −3′ and 5′-GATGATGATGATGATGGAGTTGTTGTAAGAGGAAGG − 3′. The cDNA of eat-4 was synthesized based on the sequence of eat-4 cDNA isoform a from WormBase. The eat-4 promoter and eat-4 cDNA were cloned using SphI/KpnI and KpnI/NheI cloning sites respectively onto a pUC57 mini vector that contains GFP. The rescue construct of sod-1 contains the sod-1 promoter region as previously described (Horspool and Chang, 2017). The cDNA in the sod-1 rescue construct is the sod-1 cDNA isoform a. Detailed primer sets and methods used for cloning are available upon request.

Spontaneous reversal assay

Roughly 25 animals were transferred to a Petri dish that contained a thin layer of OP50 food. After 15 min, each individual animal was traced for 5 min. The total number of reversal movements was recorded. After 5 min, the animal was killed and a new target was recorded for reversal movement, with the same duration and method.

Microscopy

Animals were mounted in M9 with levamisole (10 mM) onto slides with a 3% agarose pad. The slides were viewed using an AxioImager fluorescence microscope (Zeiss) with 10x/0.25, 40x/0.75, and 63x/1.4 (oil) objectives. The fluorescence signals were recorded by a CCD camera in a 16-bit format without saturation.

Quantification and statistical analysis

The images were captured and analyzed by MetaMorph imaging software. For all experiments, the significance of differences between conditions were evaluated with GraphPad Prism software. All datasets, except Figure 3E, are analyzed using one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test. In Figure 3E, the significance of differences between each two datasets were determined by Welsh's t-test.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (CGC), which is supported by the NIH P40 OD010440, for providing us with many strains. This work was supported by the NIH grant R01 GM131156 to H.C.C.

Author contributions

C.Y.Y. performed the experiments and wrote the draft of the manuscript. H.C.C. designed and performed the experiments, analyzed the results, and wrote the paper.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: March 18, 2022

Data and code availability

-

•

All data reported in this paper will be shared upon request.

-

•

Code: This paper does not include any datasets requiring accession numbers, DOIs, unique identifiers and original code.

-

•

Other items: Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

References

- Bargmann C.I., Kaplan J.M. Signal transduction in the Caenorhabditis elegans nervous system. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 1998;21:279–308. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.21.1.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baskoylu S.N., Yersak J., O'Hern P., Grosser S., Simon J., Kim S., Schuch K., Dimitriadi M., Yanagi K.S., Lins J., Hart A.C. Single copy/knock-in models of ALS SOD1 in C. elegans suggest loss and gain of function have different contributions to cholinergic and glutamatergic neurodegeneration. Plos Genet. 2018;14:e1007682. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner S. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1974;77:71–94. doi: 10.1093/genetics/77.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockie P.J., Madsen D.M., Zheng Y., Mellem J., Maricq A.V. Differential expression of glutamate receptor subunits in the nervous system of Caenorhabditis elegans and their regulation by the homeodomain protein UNC-42. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:1510–1522. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-05-01510.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockie P.J., Mellem J.E., Hills T., Madsen D.M., Maricq A.V. The C. elegans glutamate receptor subunit NMR-1 is required for slow NMDA-activated currents that regulate reversal frequency during locomotion. Neuron. 2001;31:617–630. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00394-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruijn L.I., Becher M.W., Lee M.K., Anderson K.L., Jenkins N.A., Copeland N.G., Sisodia S.S., Rothstein J.D., Borchelt D.R., Price D.L., Cleveland D.W. ALS-linked SOD1 mutant G85R mediates damage to astrocytes and promotes rapidly progressive disease with SOD1-containing inclusions. Neuron. 1997;18:327–338. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80272-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruijn L.I., Houseweart M.K., Kato S., Anderson K.L., Anderson S.D., Ohama E., Reaume A.G., Scott R.W., Cleveland D.W. Aggregation and motor neuron toxicity of an ALS-linked SOD1 mutant independent from wild-type SOD1. Science. 1998;281:1851–1854. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5384.1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carriedo S.G., Sensi S.L., Yin H.Z., Weiss J.H. AMPA exposures induce mitochondrial Ca(2+) overload and ROS generation in spinal motor neurons in vitro. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:240–250. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-01-00240.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ch'ng Q., Sieburth D., Kaplan J.M. Profiling synaptic proteins identifies regulators of insulin secretion and lifespan. Plos Genet. 2008;4:e1000283. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalasani S.H., Chronis N., Tsunozaki M., Gray J.M., Ramot D., Goodman M.B., Bargmann C.I. Dissecting a circuit for olfactory behaviour in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2007;450:63–70. doi: 10.1038/nature06292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang H.C., Paek J., Kim D.H. Natural polymorphisms in C. elegans HECW-1 E3 ligase affect pathogen avoidance behaviour. Nature. 2011;480:525–529. doi: 10.1038/nature10643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang H.C., Rongo C. Cytosolic tail sequences and subunit interactions are critical for synaptic localization of glutamate receptors. J. Cell Sci. 2005;118:1945–1956. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coburn C.M., Bargmann C.I. A putative cyclic nucleotide-gated channel is required for sensory development and function in C. elegans. Neuron. 1996;17:695–706. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80201-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colbert H.A., Smith T.L., Bargmann C.I. OSM-9, a novel protein with structural similarity to channels, is required for olfaction, mechanosensation, and olfactory adaptation in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:8259–8269. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-21-08259.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis D.R., Watkins J.C. The excitation and depression of spinal neurones by structurally related amino acids. J. Neurochem. 1960;6:117–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1960.tb13458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng H.X., Hentati A., Tainer J.A., Iqbal Z., Cayabyab A., Hung W.Y., Getzoff E.D., Hu P., Herzfeldt B., Roos R.P., et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and structural defects in Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase. Science. 1993;261:1047–1051. doi: 10.1126/science.8351519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster K.J., Cheesman H.K., Liu P., Peterson N.D., Anderson S.M., Pukkila-Worley R. Innate immunity in the C. elegans intestine is programmed by a neuronal regulator of AWC olfactory neuron development. Cell Rep. 2020;31:107478. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.03.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurney M.E., Pu H., Chiu A.Y., Dal Canto M.C., Polchow C.Y., Alexander D.D., Caliendo J., Hentati A., Kwon Y.W., Deng H.X., et al. Motor neuron degeneration in mice that express a human Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase mutation. Science. 1994;264:1772–1775. doi: 10.1126/science.8209258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart A.C., Kass J., Shapiro J.E., Kaplan J.M. Distinct signaling pathways mediate touch and osmosensory responses in a polymodal sensory neuron. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:1952–1958. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-06-01952.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart A.C., Sims S., Kaplan J.M. Synaptic code for sensory modalities revealed by C. elegans GLR-1 glutamate receptor. Nature. 1995;378:82–85. doi: 10.1038/378082a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeven R., Mccallum K.C., Cruz M.R., Garsin D.A. Ce-Duox1/BLI-3 generated reactive oxygen species trigger protective SKN-1 activity via p38 MAPK signaling during infection in C. elegans. Plos Pathog. 2011;7:e1002453. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horspool A.M., Chang H.C. Superoxide dismutase SOD-1 modulates C. elegans pathogen avoidance behavior. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:45128. doi: 10.1038/srep45128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horspool A.M., Chang H.C. Neuron-specific regulation of superoxide dismutase amid pathogen-induced gut dysbiosis. Redox Biol. 2018;17:377–385. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2018.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kage-Nakadai E., Imae R., Yoshina S., Mitani S. Methods for single/low-copy integration by ultraviolet and trimethylpsoralen treatment in Caenorhabditis elegans. Methods. 2014;68:397–402. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2014.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu H., Mori I., Rhee J.S., Akaike N., Ohshima Y. Mutations in a cyclic nucleotide-gated channel lead to abnormal thermosensation and chemosensation in C. elegans. Neuron. 1996;17:707–718. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80202-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H.K., Takamiya K., He K., Song L., Huganir R.L. Specific roles of AMPA receptor subunit GluR1 (GluA1) phosphorylation sites in regulating synaptic plasticity in the CA1 region of hippocampus. J. Neurophysiol. 2010;103:479–489. doi: 10.1152/jn.00835.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee R.Y., Sawin E.R., Chalfie M., Horvitz H.R., Avery L. EAT-4, a homolog of a mammalian sodium-dependent inorganic phosphate cotransporter, is necessary for glutamatergic neurotransmission in caenorhabditis elegans. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:159–167. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-01-00159.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Sellegounder D., Sun J. Neuronal GPCR OCTR-1 regulates innate immunity by controlling protein synthesis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:36832. doi: 10.1038/srep36832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maricq A.V., Peckol E., Driscoll M., Bargmann C.I. Mechanosensory signalling in C. elegans mediated by the GLR-1 glutamate receptor. Nature. 1995;378:78–81. doi: 10.1038/378078a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meisel J.D., Panda O., Mahanti P., Schroeder F.C., Kim D.H. Chemosensation of bacterial secondary metabolites modulates neuroendocrine signaling and behavior of C. elegans. Cell. 2014;159:267–280. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori I. Genetics of chemotaxis and thermotaxis in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Annu. Rev. Genet. 1999;33:399–422. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.33.1.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller F.L., Song W., Liu Y., Chaudhuri A., Pieke-Dahl S., Strong R., Huang T.T., Epstein C.J., Roberts L.J.,2N.D., Csete M., et al. Absence of CuZn superoxide dismutase leads to elevated oxidative stress and acceleration of age-dependent skeletal muscle atrophy. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2006;40:1993–2004. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'donnell M.P., Fox B.W., Chao P.H., Schroeder F.C., Sengupta P. A neurotransmitter produced by gut bacteria modulates host sensory behaviour. Nature. 2020;583:415–420. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2395-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oeda T., Shimohama S., Kitagawa N., Kohno R., Imura T., Shibasaki H., Ishii N. Oxidative stress causes abnormal accumulation of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-related mutant SOD1 in transgenic Caenorhabditis elegans. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001;10:2013–2023. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.19.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy K.C., Andersen E.C., Kruglyak L., Kim D.H. A polymorphism in npr-1 is a behavioral determinant of pathogen susceptibility in C. elegans. Science. 2009;323:382–384. doi: 10.1126/science.1166527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rongo C., Whitfield C.W., Rodal A., Kim S.K., Kaplan J.M. LIN-10 is a shared component of the polarized protein localization pathways in neurons and epithelia. Cell. 1998;94:751–759. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81734-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen D.R., Siddique T., Patterson D., Figlewicz D.A., Sapp P., Hentati A., Donaldson D., Goto J., O'regan J.P., Deng H.X., et al. Mutations in Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase gene are associated with familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nature. 1993;362:59–62. doi: 10.1038/362059a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy J., Minotti S., Dong L., Figlewicz D.A., Durham H.D. Glutamate potentiates the toxicity of mutant Cu/Zn-superoxide dismutase in motor neurons by postsynaptic calcium-dependent mechanisms. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:9673–9684. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-23-09673.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sattler R., Tymianski M. Molecular mechanisms of glutamate receptor-mediated excitotoxic neuronal cell death. Mol. Neurobiol. 2001;24:107–129. doi: 10.1385/MN:24:1-3:107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano-Saiz E., Poole R.J., Felton T., Zhang F., De La Cruz E.D., Hobert O. Modular control of glutamatergic neuronal identity in C. elegans by distinct homeodomain proteins. Cell. 2013;155:659–673. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano-Saiz E., Vogt M.C., Levy S., Wang Y., Kaczmarczyk K.K., Mei X., Bai G., Singson A., Grant B.D., Hobert O. SLC17A6/7/8 vesicular glutamate transporter homologs in nematodes. Genetics. 2020;214:163–178. doi: 10.1534/genetics.119.302855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddique T., Figlewicz D.A., Pericak-Vance M.A., Haines J.L., Rouleau G., Jeffers A.J., Sapp P., Hung W.Y., Bebout J., Mckenna-Yasek D., et al. Linkage of a gene causing familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis to chromosome 21 and evidence of genetic-locus heterogeneity. N. Engl. J. Med. 1991;324:1381–1384. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199105163242001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J., Singh V., Kajino-Sakamoto R., Aballay A. Neuronal GPCR controls innate immunity by regulating noncanonical unfolded protein response genes. Science. 2011;332:729–732. doi: 10.1126/science.1203411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobin D.M., Madsen D.M., Kahn-Kirby A., Peckol E.L., Moulder G., Barstead R., Maricq A.V., Bargmann C.I. Combinatorial expression of TRPV channel proteins defines their sensory functions and subcellular localization in C. elegans neurons. Neuron. 2002;35:307–318. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00757-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu P.H., Raju P., Robinson K.A., Gurney M.E., Trojanowski J.Q., Lee V.M. Transgenic mice carrying a human mutant superoxide dismutase transgene develop neuronal cytoskeletal pathology resembling human amyotrophic lateral sclerosis lesions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1996;93:3155–3160. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.7.3155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentine J.S., Doucette P.A., Zittin Potter S. Copper-zinc superoxide dismutase and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2005;74:563–593. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolstenholme A.J. Glutamate-gated Cl- channels in Caenorhabditis elegans and parasitic nematodes. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 1997;25:830–834. doi: 10.1042/bst0250830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Lu H., Bargmann C.I. Pathogenic bacteria induce aversive olfactory learning in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2005;438:179–184. doi: 10.1038/nature04216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

-

•

All data reported in this paper will be shared upon request.

-

•

Code: This paper does not include any datasets requiring accession numbers, DOIs, unique identifiers and original code.

-

•

Other items: Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.