Abstract

An 82-year-old man presented to the emergency department with delirium, vomiting and an initial hyponatraemia of 112 mmol/L the day after successful transurethral vaporisation of the prostate. He had a tonic-clonic seizure in the acute surgical unit and was managed subsequently in the intensive care unit with a controlled rate of hypertonic saline. Initial work-up for the cause of hyponatraemia revealed a low urine osmolality, suggestive of relative excess water intake. Detailed examination of the operation notes revealed no discrepancy between intraoperative irrigating fluid input and output. Careful collateral history revealed that the patient had drunk 8 L of water in the 24 hours following the operation, after taking advice to ‘drink plenty of water’ literally. This case highlights the importance of conveying specific advice to patient, the lower incidence of transurethral resection syndrome in resections using saline as an irrigation fluid and outlines the pathway for investigation and management for hyponatraemia.

Keywords: prostate, urological surgery, epilepsy and seizures, adult intensive care, endocrinology

Background

Hyponatraemia is the most commonly encountered electrolyte abnormality in hospitalised patients and can lead to severe clinical manifestations. The symptoms range from impaired concentration, nausea and gait disturbances in mild hyponatraemia; delirium, confusion and headache in moderate hyponatraemia; and vomiting, seizures and coma in severe hyponatraemia.1 However, the causes of hyponatraemia are heterogeneous in nature, due to the wide-ranging mechanisms and pathways involved in water and sodium homeostasis. The approach to the patient with hyponatraemia is, therefore, based around identifying true hyponatraemia, determining whether the onset is acute or chronic, determining the severity by correlating with symptoms, then identifying the cause. This is because management is guided by these factors (table 1).2

Table 1.

Management of the correction of hyponatraemia based on symptoms, time of onset and volume status. Information from the UK National Institute of Clinical Excellence Guidelines.2

| Management of hyponatraemia | |

| Acute hyponatraemia and no/mild symptoms | Stop non-essential parenteral fluids and medications which provoke hyponatraemia |

| Acute hyponatraemia and moderate to severe symptoms | Hypertonic saline to correct any cerebral oedema |

| Chronic hyponatraemia (>48 hours) and no/mild symptoms | Usually can be managed in an outpatient setting |

| Chronic hyponatraemia (>48 hours) and moderate to severe symptoms | Stop non-essential parenteral fluids and medications that provoke hyponatraemia |

| Plus the following management based on fluid status | |

| Hypovolaemia | Restore extracellular volume with 0.9% saline |

| Hypervolaemia | Fluid restrict |

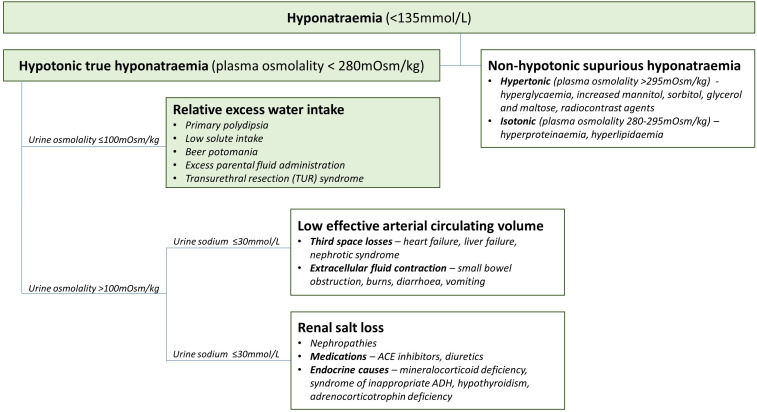

The first step is identifying whether the hyponatraemia is hypotonic or non-hypotonic. Non-hypotonic hyponatraemia is spurious hyponatraemia due to the nature of laboratory assays. Hypertonic (plasma osmolality >295 mOsm/kg) pseudohyponatraemia is from redistribution of sodium due to osmotically active solutes in the plasma, including hyperglycaemia, increased mannitol, sorbitol, glycerol and maltose, or radiocontrast agents. Isotonic (280–295 mOsm/kg) pseudohyponatraemia is due to reduced plasma water fraction from hyperproteinaemia or hyperlipidaemia.3

True hyponatraemia is characterised by a reduction in serum osmolality (<280 mOsm). In the correction of true hypotonic hyponatraemia in secondary care, patients with acute hyponatraemia and moderate to severe symptoms are treated with hypertonic saline to correct any cerebral oedema and reduce the risk of sequelae of severe hyponatraemia. Rapid overcorrection is also a risk in this case and may lead to central pontine myelinolysis.4 Other patients with chronic hyponatraemia or with mild symptoms do not require such an extreme correction. Additional correction of fluid balance is given depending on clinical fluid status, and patients with hypovolaemia should be resuscitated with 0.9% saline and patients with hypovolaemia should be fluid restricted to 1–1.5 L/day.2

The second stage is the identification of the cause of hyponatraemia and the management of the underlying disorder if reversible. The European Guidelines on approach of hyponatraemia recommend the measurement of urine osmolality from a spot urine sample. If urine osmolality is low (≤100 mOsm), the cause of hyponatraemia is likely relative excess water intake such as primary polydipsia, low solute intake, beer potomania, excess parental fluid administration and transurethral resection (TUR) syndrome.5 If urine osmolality is high (>100 mOsm), then a paired urine and plasma sodium is needed to elucidate whether the electrolyte derangement is from low effective arterial circulating volume (urine sodium ≤30 mmol/L) or from renal salt loss (urine sodium >30 mmol/L).5 The first is from third space losses such as heart failure, liver failure, nephrotic syndrome or extracellular fluid contraction from small bowel obstruction, burns, diarrhoea and vomiting.6 This can be further elucidated from careful history taking and clinical examination. The second is from nephropathies, medications such as ACE inhibitors and diuretics and endocrine causes such as mineralocorticoid deficiency, syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone, hypothyroidism and adrenocorticotropin deficiency.6 This can be further elucidated by examining medication history and measuring cortisol and thyroid function.

Case presentation

A man in his 80s presented to the emergency department with delirium and vomiting 1 day after GreenLight laser transurethral vaporisation of the prostate (TUVP). TUVP had been conducted for bladder outflow obstruction and severe lower urinary tract symptoms. Prior to TUVP, all his blood tests had been unconcerning, with plasma sodium within normal reference ranges. The laser time was 24 min, with 8 L of irrigating saline in and an equal volume out. A 22Ch catheter had been inserted, and he was discharged the same day. He had been given advice regarding hydration and drank plenty of water after the operation and had an appointment to remove his catheter in 5 days. No concerns had been raised on discharge.

His previous medical history comprised type 2 diabetes mellitus, ischaemic heart disease and hypertension. Previous surgical history comprised a previous transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) which was performed in 2015 with no complications.

He appeared clinically euvolaemic on physical examination. Initial blood tests in the emergency department revealed an acute hyponatraemia of 112 mmol/L and hypochloraemia of 80 mmol/L. His renal function appeared to be normal, with a potassium of 4.1 mmol/L, urea 4.4 mmol/L, creatinine 70 µmol/L and an estimated glomerular filtration rate of over 60 mL/min/1.73 m2. Inflammatory markers were mildly raised with C reactive protein of 12.0 mg/dL and white cell count of 10.5×109/L. He had a slight dilutional anaemia of haemoglobin 122 g/L, which was proportional to haematocrit.

He was initially treated as urosepsis with gentamicin, and his hyponatraemia was managed with intravenous normal saline. As he was considered stable, he was transferred to the acute surgical unit, where he became unresponsive and had a tonic-clinic seizure, which self-terminated after 2 min. He was therefore transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) and treated with hypertonic saline.

Investigations

As the initial hyponatraemia was being treated, the second stage involved identifying the cause of the hyponatraemia. The following investigations were conducted in ICU:

arterial blood gas showed pH 7.398, pO2 10.4 kPa, pCO2 4.16 kPa, sodium 114 mmol/L, lactate 1.3 mmol/L and glucose 12.8 mmol/L.

Renal profile showed sodium 117 mmol/L, potassium 3.5 mmol/L, chloride 89 mmol/L, urea 3.8 mmol/L and creatinine 69 µmol/L.

Urine osmolality was 98 mOsm, urine sodium was 13 mmol/L and blood osmolality was 256 mOsm.

Differential diagnosis

The hyponatraemia was determined to be true hypotonic hyponatraemia, as plasma osmolality was 256 mOsm, arterial blood had shown a glucose of 12.8 mmol/L, his lipid level was well controlled with statins, and there was nothing in the history to suggest hyperproteinaemia or other osmotically active solutes.

Urine osmolality was decreased at 98 mOsm, which suggested relative excess water intake (figure 1). The causes of this include primary polydipsia, low solute intake, beer potomania, excess parental fluid administration and TUR syndrome. As the onset of hyponatraemia was acute, the history from the operation to his admission was examined more closely. TUR syndrome is a complication which may occur after TURP or transurethral resection of the bladder (TURBT).7 Traditionally, these operations use monopolar diathermy. This uses glycine as irrigation fluid, which is unpredictably absorbed by the venous sinus plexus and can cause dilution of circulating volume.7 The emergence of bipolar diathermy in TURP and TURBT, and laser in TUVP, enables the use of isotonic saline as irrigation fluid. This leads to a much lower risk of TUR syndrome as absorption of isotonic saline will not result in such profound electrolyte imbalances compared with glycine.8 The volume of intraoperative irrigating fluid is also monitored to assess if the patient has absorbed any. In this operation, input and output fluid were equal. Both of these factors make it more unlikely the cause was due to TUR syndrome.

Figure 1.

Differential diagnoses for hyponatraemia, including work-up pathway for this case report (green). Diagnostic pathway adapted from European guidelines (Spasovski et al5).

It emerged that the patient had taken the advice to ‘drink plenty of water’ after the operation literally and had drank almost 8 L in the first 24 hours following the operation. His symptoms were therefore linked to primary polydipsia.

Treatment

The symptoms of vomiting, delirium and tonic-clonic seizure were attributed to severe acute hyponatraemia. This is a medical emergency, and management of this acutely was through the use of hypertonic (2.7% or 3%) saline from ICU. Guidelines from the European Society of Endocrinology recommend prompt intravenous infusion of 150 mL 3% hypertonic saline over 20 min, followed by checking serum sodium and repeating the infusion. This should be repeated twice or until the serum sodium rises by 5 mmol/L.1

However, the speed of correction after this must be controlled to prevent the risk of central pontine myelinolysis. If the patient is still symptomatic, intravenous 3% hypertonic saline should be continued, with a rate of correction limited to 1 mmol/L/hour, to be stopped either once the serum sodium increases 10 mmol/L in total, until the serum sodium reaches 130 mmol/L or when the patient improves clinically. If the patient has an improvement in symptoms, then hypertonic saline should be stopped, and specific treatment started based on the type of hyponatraemia, aiming for a correction of no more than 10 mmol/L over the first 24 hours, and no more than 8 mmol/L during every 24 hours following this, until serum sodium reaches 130 mmol/L.1

His medications were also reviewed, and bendroflumethiazide was held to prevent renal sodium loss. He was also started on a fluid restriction regime during the infusion of hypertonic saline.

Outcome and follow-up

Plasma sodium was normalised to the reference range (135–145 mmol/L) after a 3-day ICU stay, and he was stepped down to the ward. He was not started on an antiepileptic agent, and he had no further seizures during his hospital course. His sodium was in a normal range after stepping down, and he had no neurological sequelae from the period of acute hyponatraemia. He was therefore discharged home with more specific advice of drinking 2 L of water a day. On follow-up, he has continued to follow this advice and has had no further seizures.

Discussion

This case highlights the importance of careful investigation and history taking in the diagnostic work-up and treatment for a patient admitted with a hyponatraemic seizure. Following European Guidelines, plasma and urine osmolality elucidated relative excess water intake as the cause of his hyponatraemia.5 The nature of his presentation following recent urological surgery would have been initially suggestive of TUR syndrome, but closer examination of the operation notes and collateral history revealed the hyponatraemia was secondary to primary polydipsia.

Most cases of primary polydipsia are psychogenic in nature, with few cases of non-psychogenic primary polydipsia reported in the literature.9 Causes of non-psychogenic primary polydipsia include children fed excessive fluid by caretakers, patients voluntarily drinking excessive fluid and patients following the advice of medical staff to ‘drink plenty’.10 In these cases, acute water intoxication occurred within a few hours to days, similar to the time frame for our patient.10 Iatrogenic polydipsia following urological surgery has only been reported once before in the literature.11 We present this case due to the considerable morbidity associated with severe hyponatraemia secondary to primary polydipsia and the simple prevention of this with more specific advice.

Patient’s perspective.

My father was discharged from hospital the evening after his operation. I visited him at home around 18:00, he had been discharged and sent home in a taxi. He seemed to be reasonably well. He had been told to drink plenty of water, which he did, and he was fitted with a catheter.

I understand from my mother that he had a restless night and was vomiting and had diarrhoea and a leak from the catheter. I called to visit the next day and I made and had lunch with my parents. During the course of eating lunch, my father seemed to gulp while eating and I thought he was going to be sick. He was very tired and I left to let him rest. The district nurse called around lunch time and showed my father how to deal with his catheter.

At approximately 16:00, I received a message from my mother to go back and take my father to the hospital as he had continued to violently vomit. When I arrived he was worried that the catheter fitted on his leg was not working properly as it did not seem to be filling up. He did not feel sick at that time. He said instead of going to the hospital, could we take him to the emergency department at the local health centre, which was only 2 min’ drive from the house. We drove Dad to the health centre and we waited almost 30 min before he was seen. During the wait, he became very faint and hot and he said he felt like he was going to pass out. I got him a drink of water, and told the reception that he needed a doctor urgently as he was about to pass out. He was called to see the doctor at approximately 17:25, but he was violently sick as soon as he stood up to walk, about three times in a distance of about 50 m. The doctor rang for an ambulance to the hospital.

My mother waited with him until the ambulance came and I went to get an overnight bag, and to meet up at the hospital. He vomited a few further times while in the health centre. The ambulance arrived and carried out various tests before taking him to the hospital.

It was almost 19:00 before my father arrived at the hospital. He was in the queue to be attended to. He was very subdued but had stopped vomiting. He kept sipping water. At approximately 22.30, he was examined by a nurse and had tests taken. My mother and I were worried because he had not had any medication for his diabetes and because he had been sick so many times, he had little food inside him. His glucose level was checked I believe it was 15, and although much higher than his usual reading around 7, the doctor and nurse were not concerned. During his wait he was heaving as though to be sick, but was not sick. He called out for his cousin, who had recently passed away and seemed to be having a conversation with him. Dad was very scared because he thought he was going to pass away. I kept telling him he would be fine, that he had an infection and it would be sorted and not to worry. He became calm and started to concentrate on his false teeth which had been put into a cardboard bowl. He did not seem to know what they were and was pressing each tooth as though they were a remote control. Eventually he put one set in his mouth, but it seemed to take a great deal of time to work out which way round they fitted. There was also a raised joint on the railing on the bed which he kept pressing thinking it was a bell to call the nurse. At approximately 23.45, he was seen by a doctor.

The results of the tests the nurse had taken earlier had come through and the doctor immediately put him on a salt drip.

I asked the doctor if he would be kept in hospital over night as no one was able to tell us before if he would be discharged that night. The doctor said he would definitely not be leaving the hospital that night. Dad was very tired and was almost falling asleep while the doctor attended to him. We left the hospital at approximately 00.30 and I left my contact details.

At approximately 02:30 I had a phone call from a nurse on the assessment ward to say that Dad had taken a turn for the worse and that he was a very sick man and was not responding and it may be helpful if me and my mother went back to the hospital in case the doctors needed to ask us questions. My mother and I went back to the hospital at approximately 03:00. At this point my father had been moved to intensive care. He did appear to look better than when we had left at 00:30.

We were told that he had a seizure and had passed out on the assessment ward and was not responding and the nurse had to bring him round which took about 10 min, as I understand it.

We left the ward while Dad was seen by the intensive care nurses and we were interviewed by a Doctor. We went back to the ward and Dad was comfortable and receiving the medication he needed. We left at approximately 04:15.

He received the treatment he needed at the doctor and was discharged 5 days later.

Talking to my father after his recovery he has no recollection of any of these above events.

Learning points.

Be specific in advice given to patients; they may interpret advice in a different manner than intended.

True hyponatraemia is a hypotonic state, and work-up includes serum and urine osmolality, urine and plasma sodium, and assessment of fluid balance.

Risk of transurethral resection syndrome is greatly reduced in transurethral vaporisation of the prostate (TUVP) compared with transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) due to the use of saline instead of glycine as an irrigating solution.

Acute severe hyponatraemia with neurological symptoms requires initial correction with hypertonic saline in an intensive care unit setting.

The rate of correction of hyponatraemia needs to be carefully monitored and controlled to prevent central pontine myelinolysis.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors were in the medical and surgical team managing the patient. JH wrote the manuscript and JD and MNE reviewed the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Case reports provide a valuable learning resource for the scientific community and can indicate areas of interest for future research. They should not be used in isolation to guide treatment choices or public health policy.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Obtained.

References

- 1.Spasovski G, Vanholder R, Allolio B, et al. Clinical practice guideline on diagnosis and treatment of hyponatraemia. Eur J Endocrinol 2014;170:G1–47. 10.1530/EJE-13-1020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.CKS NICE hyponatraemia: management. Available: https://cks.nice.org.uk/hyponatraemia [Accessed May 2020].

- 3.Hoorn EJ, Zietse R. Diagnosis and treatment of hyponatremia: compilation of the guidelines. J Am Soc Nephrol 2017;28:1340–9. 10.1681/ASN.2016101139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.George JC, Zafar W, Bucaloiu ID, et al. Risk factors and outcomes of rapid correction of severe hyponatremia. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2018;13:984–92. 10.2215/CJN.13061117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spasovski G, Vanholder R, Allolio B, et al. Clinical practice guideline on diagnosis and treatment of hyponatraemia. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2014;29 Suppl 2:i1–39. 10.1093/ndt/gfu040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adrogué HJ, Madias NE. Hyponatremia. N Engl J Med 2000;342:1581–9. 10.1056/NEJM200005253422107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okeke AA, Lodge R, Hinchliffe A, et al. Ethanol-glycine irrigating fluid for transurethral resection of the prostate in practice. BJU Int 2000;86:43–6. 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2000.00733.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Falahatkar S, Mokhtari G, Moghaddam KG, et al. Bipolar transurethral vaporization: a superior procedure in benign prostatic hyperplasia: a prospective randomized comparison with bipolar TURP. Int Braz J Urol 2014;40:346–55. 10.1590/S1677-5538.IBJU.2014.03.08 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dundas B, Harris M, Narasimhan M. Psychogenic polydipsia review: etiology, differential, and treatment. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2007;9:236–41. 10.1007/s11920-007-0025-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weiss G. Non-Psychogenic polydipsia with hyponatremia. The Internet Journal of Nephrology 2004;2. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olapade-Olaopa EO, Morley RN, Ahiaku EK, et al. Iatrogenic polydipsia: a rare cause of water intoxication in urology. Br J Urol 1997;79:488. 10.1046/j.1464-410X.1997.11538.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]