Abstract

Human reaction delay significantly limits manual control of unstable systems. It is more difficult to balance a short stick on a fingertip than a long one, because a shorter stick falls faster and therefore requires faster reactions. In this study, a virtual stick balancing environment was developed where the reaction delay can be artificially modulated and the law of motion can be changed between second-order (Newtonian) and first-order (Aristotelian) dynamics. Twenty-four subjects were separated into two groups and asked to perform virtual stick balancing programmed according to either Newtonian or Aristotelian dynamics. The shortest stick length (critical length, Lc) was determined for different added delays in six sessions of balancing trials performed on different days. The observed relation between Lc and the overall reaction delay τ reflected the feature of the underlying mathematical models: (i) for the Newtonian dynamics Lc is proportional to τ2; (ii) for the Aristotelian dynamics Lc is proportional to τ. Deviation of the measured Lc(τ) function from the theoretical one was larger for the Newtonian dynamics for all sessions, which suggests that, at least in virtually controlled tasks, it is more difficult to adopt second-order dynamics than first-order dynamics.

Keywords: human balancing, dynamics order, reaction delay, delayed feedback, stabilizability, motor learning

1. Introduction

There are many situations in everyday human activities that require persistent attention and instantaneous control actions at the same time. Driving a car [1], holding and carrying a cup of coffee [2], recovery from perturbation during quiet standing [3] or a more challenging task, such as balancing on a balance board [4,5] or on a tightrope [6], can be mentioned as examples. From a dynamical systems point of view, these activities correspond to the feedback stabilization of unstable or marginally stable systems. Skill development in novel voluntary tasks requires sensory information and practice [7]. During practice, the variability of the outcome of repetitions generally decreases as skill increases [8]. Understanding the development of these motor control tasks has important implications in teaching various movement types, for example performing a sudden manoeuvre safely during driving a car or fine motor control during surgical operations.

Human motor control is constrained by reaction time delay and sensory and motor uncertainties [9]. The disparity between novice and expert motor performance lies at the level of the organization of the neural networks that are involved in motor planning [10,11]. Reaction time of human subjects can be readily estimated using reaction time tests [12–15]. The reaction time delay has a crucial role in the stabilization of unstable systems [16]. A stabilizing control action should be fast enough to counteract the divergent dynamics. Studies have drawn attention to the importance of critical parameters that are determined by the divergence time constant [17]. In the paradigm of stabilizing an inverted pendulum in the presence of a reaction delay, such a critical parameter is the critical length: the length of the shortest pendulum that can be stabilized for a fixed reaction delay [9,14,16].

Investigation of motion control requires task-specific measurement set-ups. Virtual environments provide a convenient framework for such investigations by making it possible to program arbitrary tasks with arbitrary parameters within the employed software. Virtual set-ups are widely applied in bio-mechanical practice, such as the benchmark problem of stick balancing with visual [12,18–20] or combined visual–haptic feedback [21,22], visuomotor tracking [23–25] or the task of moving a cup filled with liquid [2].

In a previous work by the authors [20], virtual stick balancing trials were performed by 27 subjects with different stick lengths and by adding extra delays artificially in the visualization loop. The critical length was used as a measure of human balancing performance: the shorter the stick that a subject can balance for a given time duration, the more skilled the subject. It was shown that the critical length can be well approximated as a quadratic function of the reaction delay, which corresponds to a delayed proportional–derivative (PD) feedback mechanism based on control system theory. In other words, stick balancing performance decreases with added delays in the feedback loop [22]. In the present paper, similar virtual stick balancing trials were performed by 24 subjects such that the law of motion was altered. Subjects were separated into two groups. Subjects in the first group performed the task according to Newtonian dynamics, i.e. force is equal to mass times acceleration. This task corresponds to the real-world dynamics that subjects experience during their everyday activities in a gravitational environment. Subjects in the second group performed the balancing task governed by an artificial dynamics referred to as Aristotelian dynamics, where the force is proportional to the velocity. This latter case can also be interpreted as a stick moving in a highly viscous liquid. The developments of the relation between the experimentally determined critical lengths and the artificially increased reaction times were investigated by means of a series of sessions of balancing trials for both groups.

The paper is organized as follows. First, the mathematical model and the critical length are introduced for delayed PD feedback, and the virtual balancing environment and the measurement protocol are described in §2. Then, the relation between the critical length and the reaction delay is investigated based on a comparison of the model and the measurement results in §3. Finally, conclusions are discussed in §4.

2. Methods

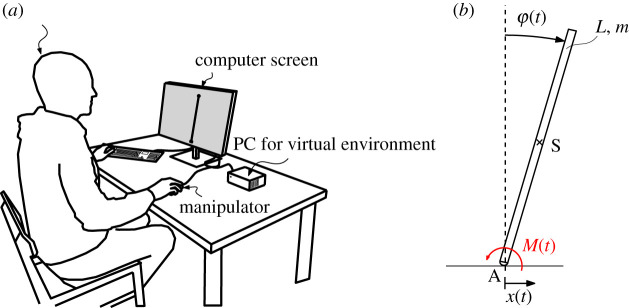

Virtual balancing tasks consist of an inverted pendulum rendered on a computer screen (figure 1). The pendulum’s pivot point was driven by human subjects through an optical computer mouse such that the displacement of the computer mouse in the medio-lateral direction corresponds to the horizontal position of the pivot point.

Figure 1.

A sketch of the virtual test environment (a) and the underlying mechanical model (b).

2.1. Mathematical model

The transition between Aristotelian and Newtonian dynamics of an inverted pendulum is given by

| 2.1 |

where φ is the angle of the pendulum with respect to the vertical axis, and indicate the angular velocity and acceleration, respectively, g = 9.81 m s−2 is the gravitational acceleration, m and L are the mass and the length of the pendulum, is the moment of inertia of the pendulum with respect to the normal line via the pivot point A and M(t) is the virtual control torque (figure 1b). The transition parameter q ∈ [0, 1] creates the connection between Aristotelian and Newtonian dynamics. The case q = 1 gives the Newtonian formulations (i.e. force equal to mass times acceleration, second-order dynamics). The case q = 0 corresponds to the Aristotelian physics (force proportional to velocity, first-order dynamics). The case 0 < q < 1 actually corresponds to a damped inverted pendulum. The parameter k = 1 s−1 is used to set the dimension of the coefficient of .

The virtual torque M(t) is computed from the movement of the pivot point, which is driven by the human subjects. The control input is determined as a linear combination of the pivot point’s velocity and acceleration as

| 2.2 |

where and are the velocity and the acceleration of point A, respectively. Then the virtual torque can be formulated as

| 2.3 |

If q = 1 then and the pendulum’s motion is governed by Newtonian dynamics. If q = 0 then , which corresponds to Aristotelian dynamics.

2.2. Proportional–derivative feedback and critical length

In bio-mechanical and robotic practice, a widely used control technique is PD feedback. In virtual balancing tasks, only visual feedback of the pendulum’s motion is available. This may question the viability of the derivative term in the human control mechanism. Admittedly, there are structures of receptors in the human retina that have evolved to sense only quick movements in the field of view [16,24,26,27]. This suggests that the feedback of the velocity of moving objects is a possible mechanism.

The feedback loop in human motion control naturally involves a dead time, which is often referred to as the reaction time or reaction delay. Thus, a possible model for the control action is

| 2.4 |

where p and d are the proportional and derivative control gains and τ is a lumped reaction time delay, which models all the latencies during the feedback mechanism. Linearized stability of (2.1) with (2.4) depends on the relation between the length of the pendulum and the reaction delay. It is more difficult to balance short sticks than long ones, since short sticks fall faster and require faster reactions from the subjects. In the case of delayed PD feedback, a theoretical limit can be derived for the length of the shortest stick that can still be stabilized [14,16,28]. For (2.1)–(2.4) with a fixed delay τ, the critical stick length can be given as

| 2.5 |

where c1 = 3g/4 is the regression parameter. If L > Lc then there exist a pair (p, d) of control gains that stabilize the stick in the vertical position. However, if L < Lc then the stick cannot be stabilized by PD feedback with any gains. It is important to highlight that when the transition parameter is q = 1 then Lc is a quadratic function of τ, while for q = 0 the relation between Lc and τ is linear, i.e.

| 2.6 |

and

| 2.7 |

where c0 = c1/k is the regression parameter for the Aristotelian dynamics. This observation suggests that the tendency between the critical length for different reaction delays obtained by virtual balancing tasks for q = 0 and q = 1 can be used to validate a possible underlying delayed PD feedback mechanism.

When parameter uncertainties are present, then the relation between Lc and τ remains quadratic for q = 1 and linear for q = 0, but the regression parameters become larger depending on the size and type of uncertainties [29]. In this sense, the parameters c1 and c0 can be considered a measure of robustness against uncertainties.

2.3. Virtual test environment

The virtual stick balancing task was implemented by software developed in the JAVA environment. The source code is readily available at (https://github.com/koviub/VirtualBalancing). The governing equation (2.1) was used to create a virtual copy of a balancing task. The nonlinear ordinary differential equation was solved using a fourth-order Runge–Kutta method with an adaptive time step Δt, such that the simulation was running in real time with an average of Δt = 16.67 ms. This time step was required because of the refresh rate of the screen, which is typically around 60 Hz and introduces an average sampling delay of . The input device was a conventional optical computer mouse. According to (2.2), the actuation is determined by the acceleration and velocity of the input device. Both the velocity and the acceleration of the subject’s hand movement were determined by a numerical derivation scheme based on the pixel position of the cursor on the screen [20,30]. Owing to the finite size of the pixels, the numerical derivation results in a noisy signal, which was compensated by a re-sampling filter. Signal filtering also introduced an artificial delay in the control loop, which was approximately τf = 50 ms. The signal processing and the calculation of the pendulum’s state were performed within a single sampling period. Thus, the overall machine delay during the virtual balancing tests was

| 2.8 |

where Δτ is an artificially added delay, which can be set in the program by the user.

The inverted pendulum was visualized as follows. The vertical dimension was scaled such that all sticks of different lengths appeared to be 90% of the screen height. However, the displacements in the horizontal direction were not scaled and matched the real deviation of the underlying dynamical model. Thus, the horizontal displacement between the top and the bottom of the stick appeared in its real size. Subjects were instructed to concentrate on the top of the stick during the stick balancing trials.

The main advantages of the virtual environment are the ability to modify (i) the reaction time of the subjects by setting Δτ; (ii) the physics of the underlying model by changing the value of the transition parameter q, and (iii) the length L of the virtual stick. In this way, the subjects' behaviour can easily be tested under different conditions.

2.4. Participants

In the framework of a student project 24 subjects were recruited (aged between 19 and 24; 22 on average). None of the subjects had a previous record of neurological or musculoskeletal impairment that could affect the study. The sport or e-sport background of the participants was not considered as a factor to analyse. Subjects performed the virtual balancing task with their dominant hand, which they used to manipulate a computer mouse in everyday activities. All the participants provided consent for all research testing and were given the opportunity to withdraw from the study at any time. The research was carried out according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.5. Instant reaction test

The software involves a module that can be used to measure instant reaction time of the test subjects directly. Subjects had to react by pushing the mouse button as fast as they could in response to 10 randomly occurring visual stimuli (red flashes on the screen). The reaction time measured this way involves the human reaction time and the input-to-output lag of the screen. The human reaction time from visual stimuli to force response at the hand is estimated to be in the range of 140–230 ms [12,14,22,24,25]. The input-to-output lag is the time it takes an input (e.g. a mouse click) to be displayed on the screen, which is in the range of 50–100 ms for different configurations [30]. The instant reaction time measurement data were recorded for every session and for each subject and were used for later analysis. The measured reaction time does not involve the sampling and the filtering delays; therefore, during virtual balancing trials, the overall delay was

| 2.9 |

2.6. Blank-out test

In order to get a better picture of the reaction time during the balancing trials, a so-called blank-out test module was implemented in the software [14]. The blank-out test was performed as a normal balancing task, but the visual perception was disturbed: the screen was turned off at a random time instant for a short period of time (for 500 ms). During the blank-out period, subjects did not have any visual feedback, and they lost intentional control of the stick. After the return of visual feedback (screen turned on), subjects typically initiated a large corrective motion. The duration between the end of the blank-out period and the corrective movement gives the reaction delay (figure 2). Note that the reaction times obtained by the blank-out tests also involve the input-to-output lag of the screen.

Figure 2.

Example of time signals during blank-out tests and their evaluation: (a) corrective acceleration, a; (b) stick angular velocity, ω; and (c) indicator function, . The corrective action takes place when reaches a maximum. The time scale was shifted, such that the start of the blank-out period is at t = 0 s.

In order to get the reaction time delays objectively for all blank-out tests, a sweeping window technique was constructed using two time windows, W−(tj) = [tj − Δw, tj] and W+(tj) = [tj, tj + Δw], before and after the time instant tj, with a length Δw = 300 ms. An objective function,

| 2.10 |

was defined to indicate the change in the corrective acceleration (a) and the effect on the angular velocity of the rod (ω), where

| 2.11 |

are the absolute mean values of the measured time signals a(t) and ω(t) over the time windows W−(tj) and W+(tj) with N = Δw/Δt, where wa = 0.1 s4 m−2, wω = 50 s2 are the specific weights. The peak in indicates the time instant, where the changes in a and in ω were the largest, i.e. the largest corrective movement takes place. An example of the measured time signals and the corresponding objective function is shown in figure 2.

2.7. Balancing protocol

The participants were divided into two groups randomly. In group 1, the transition parameter was set to q = 1 (Newtonian dynamics). In group 2, q = 0 was set (Aristotelian dynamics). The goal of the virtual balancing trials was to determine the shortest pendulum that a subject can balance for a given added delay Δ. The pendulum was considered to have fallen if the angle |φ| exceeded 20° [14]. Each subject had to perform a series of sessions, where each session is constructed as follows.

-

1.

At the beginning of each session, a simple reaction time measurement was performed using the built-in function of the software. The reaction time τr is determined as the average of the measured response times to 10 random visual stimuli.

-

2.

The added time delay Δτ was set to zero.

-

3.

The critical pendulum length Lc(0) was determined as follows. Subjects started with an initial length L1, which they were able to safely balance for 10 s during preliminary practice. The minimum and the maximum initial lengths were 4.0 m and 33.8 m and the average was 11.3 m. During the first balancing trial, the length of the pendulum was gradually decreased by a given step value ΔL1 = 0.2 m in every second. This results in increasing difficulty in the task. If the pendulum has fallen after 10 s of continuous balancing with shortening length, then the falling length L1,fall was recorded as the length at the time instant when |φ| exceeded 20°. If the duration of the trial was less than 10 s, then the trial was restarted with the same parameters L1 and ΔL1. Subjects were allowed to repeat the trial for a maximum of five times. If none of the five trials lasted at least 10 s, then the falling length was set to L1,fall = L1. After the first round of trials, the initial length of the pendulum was set to L2 = L1,fall + 10ΔL1 and the second balancing trial was started with a shorter length step ΔL2 = ΔL1/2; again, with five possible repeats if the duration was less than 10 s. In the second round, the fall length was recorded as L2,fall. The process was repeated with Li+1 = Li,fall + 10ΔLi with ΔLi+1 = ΔLi/2 for i = 2, 3, 4, 5. In the sixth round, the change in the stick length was ΔL6 = 0.00625 m s–1. The resulting change in the dynamics of 1 ∼ 2 m long sticks was found to be negligible during the 20 s trial periods. This way, the critical length was determined with resolution ΔL6 = 0.00625 m. The length where the pendulum fell in the sixth round of trials was recorded as the critical length Lc(0) = L6,fall associated with Δτ = 0.

-

4.

Step 3 was repeated six times for added delays Δτ = (j − 1)50 ms, j = 2, …, 7. This way, the critical length Lc(Δτ) was obtained for added delays Δτ = 50, 100, 150, 200, 250 and 300 ms.

-

5.

Finally, the subjects were instructed to perform 10 blank-out tests.

The overall session took approximately 30 min to complete.

The above session was repeated five times with 1–7 days difference between each session. The time differences between the sessions were on average 4.6 days with s.d. 1.2 days for group 1, and on average 4.2 days with s.d. 1.1 days for group 2. This way, the improvement in the performance of the balancing trials was monitored. Between 1 and 7 days after the sixth session, subjects performed an extra session with different transition parameters: those who did the first six sessions with q = 1 did the seventh one with q = 0 and vice versa. This last session was used to cross-check between the two groups.

3. Results

Recorded time histories (pendulum angle, cart acceleration) during the blank-out tests were evaluated and the estimated reaction times were compared with the results of the instant reaction test. The recorded critical lengths during the 6 + 1 balancing sessions were analysed as a function of the overall delays.

3.1. Reaction time measurements

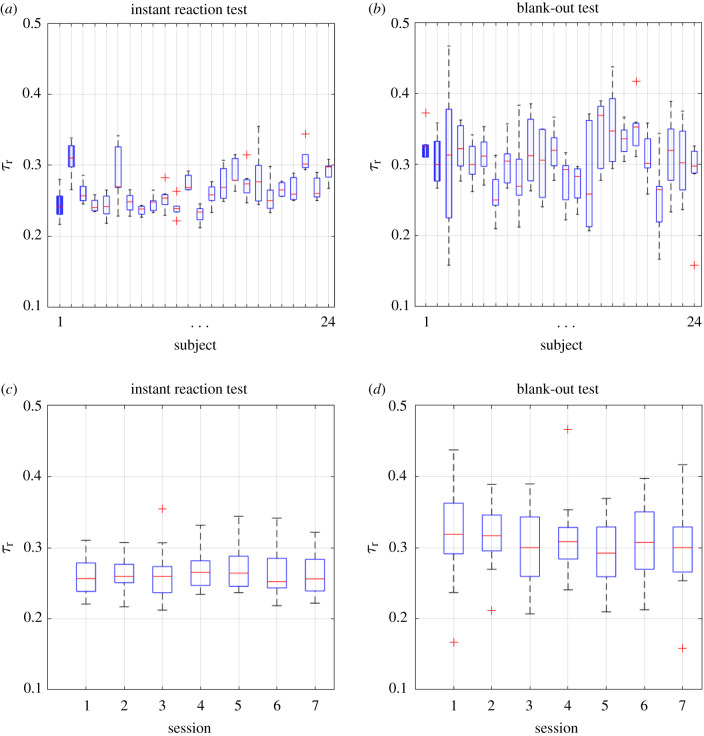

Reaction times were estimated by two different methods. In the instant reaction tests, the time between a visual stimulus and a simple reaction (button press) was measured. The task during the blank-out tests was more complicated, since the subjects had to make a decision about in which direction and to what extent to move the computer mouse after the blank-out period. Therefore, as expected, the reaction time delays during the instant reaction tests are smaller than those obtained from the blank-out data. Figure 3a,b shows the reaction times for all the subjects obtained by instant reaction tests and by blank-out tests, respectively. The average reaction time with a 95% confidence interval was 265 ± 56 ms for the instant reaction tests and 306 ± 101 ms for the blank-out tests. Note that both types of reaction times involve the input-to-output lag of the screen as well. The ‘pure’ human reaction time is therefore smaller and, based on [30], is in the range 160 –210 ms as reported in the literature for real and virtual stick balancing [12,14,20]; this is slightly larger than the delay in visual tracking [22,24,25].

Figure 3.

Comparison of the reaction tests for the 24 subjects over the course of testing: instant reaction tests (a) and blank-out tests (b), where box diagrams show the statistics of the 7 × 10 tests for each subject. Comparison of the change in the reaction time over the sessions: instant reaction tests (c) and blank-out tests (d), where box diagrams show the statistics for the 24 subjects for each session.

Figure 3c,d shows the variation in the measured reaction times for all subjects over the sessions. As expected, the variation in the result of the instant reaction tests is smaller than that in the blank-out tests. Based on the above observations, the instant reaction test was found to be more reliable; therefore, the human reaction time τr was set to be the reaction time obtained from the instant reaction tests.

3.2. Recorded time signals

Samples of the recorded time signals are shown in figure 4 for two different stick lengths without any added delay. The irregular oscillations in both φ and ξ (or in ) reflect the chaotic nature of the human control mechanism that can be attributed to unmodelled dynamics such as sensory uncertainties and motor noise. As can be seen in figure 4c,g, there are certain short time periods indicated by grey shading where the pivot point’s velocity is zero. There might be different explanations for this observation. First, zero velocity can be the result of a stick–slip motion caused by friction between the desk’s surface and the computer mouse. Second, it is also a plausible concept that in these periods the input signal (the stick’s angular position) is not big enough to trigger any control action by the subject. A third scenario is that, for certain combinations of φ and , the two terms in (2.4) might cancel each other to give approximately zero control torque. The ratio of the time duration where and the total signal length is larger (7.75%) for the longer stick than for the shorter one (4.92%). This suggest that for the duration of the periods where is related to the dynamics of the stick, that is, for longer sticks, subjects might wait longer to trigger the next control action owing to its slower dynamics. Overall, it is assumed that the periods where do not significantly affect the measured critical lengths. Nevertheless, the effect of dry friction can be the topic of further investigations.

Figure 4.

Typical time series recorded during virtual stick balancing of a long stick (L = 5.63 m, a–d) and a short stick (L = 2.75 m, e–h); angular position of the pendulum (a,e), position (b,f), velocity (c,g) and acceleration (d,h) of the pivot point A. Grey shading indicates the intervals where .

3.3. Relation between critical length and reaction delay

As shown in §2.2, the theoretical critical length Lc for the case q = 1 is a quadratic function of the reaction delay τ, while for q = 0 it is a linear function. The changes of the relation between Lc and τ during the six sessions for two subjects from the two groups are shown in figure 5. It can be observed that, for the case q = 1, the function Lc(τ) is initially linear and tends to be a ‘more’ quadratic function over the sessions. For q = 0, the function Lc(τ) remains more or less linear. This demonstrates that the critical length is fitted in the form

| 3.1 |

where c is the regression parameter and κ is an exponent. The dimension of c is m/sκ. The special cases κ = 2 and κ = 1 give (2.6) and (2.7), respectively. As mentioned in §2.2, exponent κ is related to the order of the dynamics and the regression coefficient c reflects robustness against sensory and motor uncertainties. Therefore, we consider c to be a performance measure [20] for a dynamics of given order and κ to be a model-matching measure. Note that a change in κ results is a larger change in Lc than the same relative change in c does.

Figure 5.

The change in the critical length over the six balancing sessions as a function of the overall delay for subject S6 from group 1 with q = 1 (a) and subject S24 from group 2 with q = 0 (b). The fitted curve (3.1) is shown by thin solid lines. Dashed lines indicate the theoretical critical lengths (2.6) and (2.7).

Linear regression analyses have been performed for each balancing session for each measured delay for each subject (overall (6 + 1) × 10 × 24 sessions) to obtain coefficient c and exponent κ (figures 6 and 7). The coefficient of determination for the fitting was over R2 = 0.511 in all cases with an average of R2 = 0.965. The results for the subjects from the two different groups are discussed below.

Figure 6.

Parameter fitting results for the subjects from group 1 with q = 1 in the first six sessions and q = 0 in the seventh session. Each panel corresponds to a subject, the blue markers (see left axis) show the fitted exponent κ and the red markers (see right axis) show the ratio c/c1 of fitted and reference regression coefficients. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals for fitting for all the 10 available delays measured for each subject. Dashed and dotted blue lines indicate the theoretical values κ = 2 and κ = 1 for the Newtonian dynamics and the Aristotelian dynamics, respectively. Red dashed lines indicate the theoretical value c/c1 = 1.

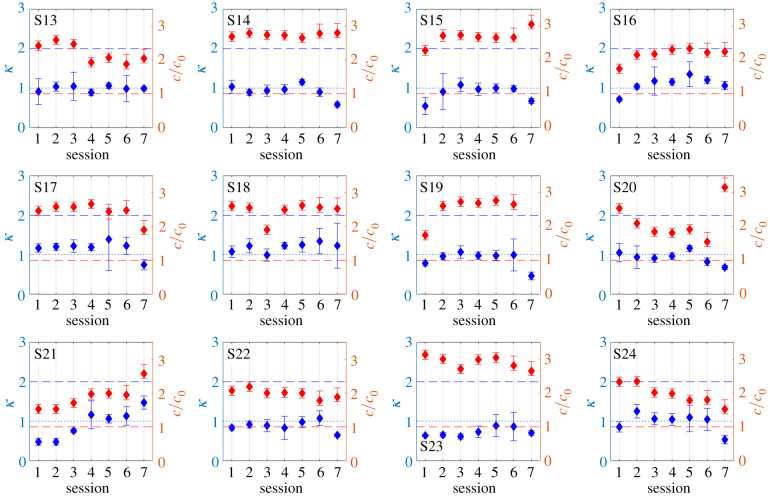

Figure 7.

Parameter fitting results for the subjects from group 2 with q = 0 in the first six sessions and q = 1 in the seventh session. Each panel corresponds to a subject, the blue markers (see left axis) show the fitted exponent κ and the red markers (see right axis) show the ratio c/c0 of fitted and reference regression coefficients. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Dashed and dotted blue lines indicate the theoretical values κ = 2 and κ = 1 for the Newtonian dynamics and the Aristotelian dynamics, respectively. Red dashed lines indicate the theoretical value c/c0 = 1. Note that c0 = c1/k, where k = 1 s−1, that is, the numerical values c/c0 and c/c1 in figures 6 and 7 can be directly compared.

We need to mention that the measured reaction times and the measured critical lengths involve uncertainties that originate partially from non-uniform human behaviour (e.g. different physiological state on different days, possible temporary loss of attention) and from the finite resolution of the measured quantities (e.g. the critical length was determined with resolution 0.00625 m, the added delay was multiples of 50 ms). These uncertainties are transferred to the estimation of parameters c and κ, which are indicated by error bars in figures 6 and 7.

Subjects from group 1 started the tests programmed according to Newtonian dynamics. Each member performed six sessions with q = 1. In the seventh session, the transition parameter was set to q = 0. Figure 6 shows the results of the parameter fitting for the 12 subjects from this group.

A clear increasing trend in the fitted exponent κ can be observed for almost all the subjects. For some subjects (e.g. S1, S4, S5, S6, S10, S11), the value of κ changed from ≈1 to ≈2 during the first six sessions. This suggests that subjects initially did not employ an optimal PD feedback that would result in (2.6). The measured critical length was found to be larger than the theoretical one, which is reflected by the average ratio c/c1 being 2.852 (see the red scale on the right axis in the panels). Over the first six sessions, all 12 subjects showed improvement, i.e. the value of c/c1 was decreasing and/or the value of κ was increasing (see the blue scale on the left axis in the panels). However, there were two subjects (S8, S9), who seemingly did not show any improvement and there was one subject (S3) whose performance did not change noticeably after the second session. In the seventh session, the subjects performed the trials with q = 0. In this session, the subjects’ performance reflected that of the theoretical model in the sense that the fitted exponent was κ ≈ 1, i.e. the relation between Lc and τ was found to be proportional, as expected from (2.7).

Group 2 started the tests with Aristotelian dynamics: they performed the first six sessions with q = 0 and the seventh session with q = 1. The results are shown in figure 7. In this group, no significant change was observed in the fitted parameters during the first six sessions. The fitted exponent κ was already ≈1 in the first and/or second sessions, which corresponds to the theoretical model given by (2.7). The change in the fitted ratio c/c1 also did not change significantly after the second session. This suggests that subjects were readily able to adopt Aristotelian dynamics. Nevertheless, similarly to group 1, the measured critical length was found to be larger than the theoretical one: the average ratio c/c0 was 2.293. During the seventh session with q = 1, however, the subjects’ performance was poor, similarly to the result of group 1 in session 1.

The balancing trials in the two groups clearly highlighted the difference between the two virtual balancing tasks. For both groups, the initial sessions showed that the control mechanism employed by the subjects fits better to the Aristotelian dynamics (i.e. κ ≈ 1). Subjects in group 2 were able to accommodate the linear relation between the critical length and the delay seemingly faster and better than subjects in group 1 were able to for the quadratic relation. These observations suggest that Aristotelian dynamics was easier to adopt by the subjects than Newtonian dynamics.

The results for all subjects are summarized in figure 8. Two main observations can be made with respect to the parameter variation in the first six sessions. First, it can be seen that the fitted exponent averaged over the subjects converges rapidly to the theoretical value κ = 1 for group 2. Already at the first session (±0.228 s.d.) and by the third session (±0.184 s.d.). In group 1, although there is a slow tendency in the average value of the fitted exponent towards κ = 2, it does not reach κ = 2 even after six sessions. Second, changes in the regression coefficients show that subjects in group 1 improved over the six sessions ( was decreased by 17%), while subjects in group 2 did not show any significant change in . We can attribute the change of κ to the accommodation of the control strategy to the underlying dynamics (either Newtonian or Aristotelian), while the change in c reflects the fine-tuning of the controller to increase robustness [20]. It shall be noted that an increase in κ and a decrease in c both result in a decrease in Lc; hence, in an improvement in balancing performance. Indeed, the critical lengths during the six sessions have generally decreased for all subjects (as shown by the sample in figure 5).

Figure 8.

Variation of the average fitted exponent (a,c) and regression ratios (b) and (d) over the course of study for group 1 (a,b) and group 2 (c,d). Error bars indicate average ± s.d. Blue markers correspond to sessions taken with transition parameter q = 1, while red markers show the result of sessions with q = 0.

Figure 8 also shows fitted parameters for the seventh session, where the transition parameter was changed to the other dynamics. An interesting observation is that, in group 1, the standard deviation of the fitted exponent in the seventh session is smaller than those in any sessions in group 2.

4. Discussion

Adding extra time delay to identify the dynamics of motion control is a frequently used technique in physiology [22,31–33]. In this study, a virtual balancing task was used to measure the dependency of the minimal length Lc that a subject can balance on the overall reaction delay τ during an approximately 30 min balancing session. This balancing session was repeated six times with overnight consolidation by each subject in order to analyse the improvement of the balancing performance due to adaptive learning. Subjects were separated into two groups based on whether the transition parameter q was 1 (Newtonian dynamics) or 0 (Aristotelian dynamics). The effect of q is manifested in the relation between Lc and τ; namely, Lc is proportional to τ1+q. Based on the evaluation of the systematic sessions of balancing trials, the following observations were made.

For group 1, the fitted exponent was initially and this slowly increased on average up to over the six sessions. This shows that there is a tendency towards the theoretical critical length Lc, but the exponent does not reach the theoretical value κ = 2 after six sessions. The learning mechanism is also reflected in the decreasing values of the regression parameter c (hence a more-and-more flattened quadratic curve).

For group 2, the fitted exponents and the regression parameters do not show any large deviation: and over the six sessions. This suggests that subjects can either readily apply or agilely adopt Aristotelian dynamics in terms of the critical length.

In the seventh session, the critical length was determined for a different transition parameter. In group 1, the fitted parameters and were about the same as the ones for group 2 in the first six sessions. This also confirms that subjects inherently possess the ability to control Aristotelian dynamics. Furthermore, standard deviation for was significantly smaller than that for group 1 in the first six sessions. This suggests that subjects can control Aristotelian dynamics more safely after practising with Newtonian dynamics. In group 2, Aristotelian dynamics was replaced by Newtonian dynamics in the seventh session. In this case, the fitted parameters correspond to the parameters of subjects in group 1 in the first session. This supports the overall observation that the Newtonian dynamics is more difficult to control and is more difficult to acquire than the Aristotelian dynamics, at least in virtually controlled balancing tasks.

An interesting observation is that, in the first session, the fitted exponent was about the same for both groups: (s.d. 0.199) for group 1 and (s.d. 0.228) for group 2. However, the regression coefficient is larger for group 1; namely, it is (s.d. 0.257), while it is (s.d. 0.461) for group 2. This is also an indirect argument for the conclusion that Newtonian dynamics is more difficult to control than Aristotelian.

From a dynamical point of view, the main difference between the two tasks is that Newtonian dynamics (q = 1) is governed by a second-order differential equation, while Aristotelian dynamics (q = 0) is governed by a first-order differential equation. On the other hand, the control action was modelled as a delayed PD feedback, i.e. as a first-order dynamic controller, for both cases. In the case of Aristotelian dynamics, a simple proportional (P) feedback without any velocity (derivative) term can stabilize the system, while for the Newtonian dynamics stabilization is not possible without a derivative feedback [9,16]. This attribute highlights the importance of receptors that perceive velocity during Newtonian motion control [34].

The change from P to PD feedback in Aristotelian dynamics corresponds to a change from PD to proportional–derivative–acceleration (PDA) feedback in Newtonian dynamics. Although the feedback from the acceleration signal may have beneficial effects with respect to robust stability [29,35], there is no physiological evidence that the human visual system is capable of precisely detecting acceleration [36,37]. Nevertheless, the relation between Lc and τ is linear for both P and PD feedback in Aristotelian dynamics and is quadratic for both PD and PDA feedback in Newtonian dynamics.

Systematic exercises of a motor control task are known to lead to the development of an internal-model-based feedforward mechanism, which is capable of compensating the neural delays by predicting the motion of the stick by means of integrating efference copies [12,14,38,39]. Based on control system theory, the corresponding control mechanism is called predictor feedback or finite spectrum assignment [9]. It shall be noted that the relation between Lc and depends only on the order of the open-loop system and does not depend on the type of feedback. When predictor feedback is applied in the model with parameter uncertainties, Lc remains proportional to for Newtonian dynamics [29] and it remains proportional to τ for Aristotelian dynamics. This means that one might end up with similar conclusions if the control mechanism is modelled by predictor feedback instead of delayed PD feedback.

Another interpretation of internal models are open-loop feedforward mechanisms, where the state of a moving object is predicted based on its actual position and velocity. The ball catching paradigm is an often cited example of such an open-loop prediction [40–42]. The evidence for an internal model capable of estimating the movement of an object in the gravitational field has been well established by experiments performed in 1g and 0g environments [41–43]. Our approach in this paper is different: we do apply gravitational force but modify the law of motion. Still, the concept of investigating the same motion in different environments (1g or 0g, Newtonian or Aristotelian) may help in discovering the adaptability of the human nervous system under different conditions.

It should be noted that the virtual task was performed without any haptic feedback, i.e. subjects did not perceive any reaction force from the stick but were left to rely on visual feedback only. This visual feedback concept corresponds to the delayed PD feedback assumption in (2.4). Furthermore, this mechanism is similar to actual stick balancing on the fingertip, which can be modelled as a pendulum–cart system. In this model, the mass of the cart involves the inertia of the moving limbs during balancing and is typically 20 ∼ 40 times larger than the mass of the balanced stick [14]. Therefore, the reaction force from the stick can be neglected compared with the actuation force acting on the cart.

Although the presented results are related to the task of a virtually controlled unstable system, the conclusions might be translated to other motor control tasks that involve sensory information feedback [2,12,19,23,44]. The underlying dynamics of the virtual tasks strongly affects the development of the balancing skill of human subjects during exercises. For most subjects, it is typically easier to readily adopt controlling first-order dynamics than second-order ones.

The virtual stick balancing application is compressed into an executable .jar file, while the evaluation of the tests were performed in a Matlab environment. The codes for the app and functions to generate the results can be downloaded from https://github.com/koviub/VirtualBalancing.

Ethics

The research was carried out following the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data accessibility

Data are available from https://github.com/koviub/VirtualBalancing.

Authors' contributions

B.A.K.: data curation, investigation, methodology, software, visualization, writing–original draft, writing–review and editing; T.I.: conceptualization, investigation, methodology, supervision, writing–original draft, writing–review and editing.

Both authors gave final approval for publication and agreed to be held accountable for the work performed herein.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

The research reported in this paper has been supported by the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund (TKP2020 NC, grant no. BME-NCS and TKP2021, project no. BME-NVA-02) under the auspices of the Ministry for Innovation and Technology and by the Hungarian National Research, Development and Innovation Office (grant no. NKFI-K138621).

References

- 1.Ge JI, Avedisov SS, He CR, Qin WB, Sadeghpour M, Orosz G. 2018. Experimental validation of connected automated vehicle design among human-driven vehicles. Transp. Res. Part C: Emerg. Technol. 91, 335-352. ( 10.1016/j.trc.2018.04.005) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bazzi S, Julia E, Hogan N, Sternad D. 2018. Stability and predictability in human control of complex objects. Chaos 28, 103103. ( 10.1063/1.5042090) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zelei A, Milton J, Stepan G, Insperger T. 2021. Response to perturbation during quiet standing resembles delayed state feedback optimized for performance and robustness. Sci. Rep. 11, 11392. ( 10.1038/s41598-021-90305-4) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cruise DR, Chagdes JR, Liddy JJ, Rietdyk S, Haddad JM, Zelaznik HN, Raman A. 2017. An active balance board system with real-time control of stiffness and time-delay to assess mechanisms of postural stability. J. Biomech. 60, 48-56. ( 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2017.06.018) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Molnar CA, Zelei A, Insperger T. 2021. Rolling balance board of adjustable geometry as a tool to assess balancing skill and to estimate reaction time delay. J. R. Soc. Interface 18, 20200956. ( 10.1098/rsif.2020.0956) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paoletti P, Mahadevan L. 2012. Balancing on tightropes and slacklines. J. R. Soc. Interface 9, 2097-2108. ( 10.1098/rsif.2012.0077) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mulder T, Hulstijn W. 1985. Sensory feedback in the learning of a novel motor task. J. Mot. Behav. 17, 110-128. ( 10.1080/00222895.1985.10735340) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Milton J, Small SS, Solodkin A. 2004. On the road to automatic: dynamic aspects in the development of expertise. J. Clin. Neurophysiol. 21, 134-143. ( 10.1097/00004691-200405000-00002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Insperger T, Milton J. 2021. Delay and uncertainty in human balancing tasks. Berlin, Germany: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bilalic M. 2017. The neuroscience of expertise. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Milton J, Solodkin A, Hlusik P, Small SL. 2007. The mind of expert motor performance is cool and focused. NeuroImage 35, 804-813. ( 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.01.003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mehta B, Schaal S. 2002. Forward models in visuomotor control. J. Neurophysiol. 88, 942-953. ( 10.1152/jn.2002.88.2.942) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Woods DL, Wyma JM, Yund EW, Herron TJ, Reed B. 2015. Factors influencing the latency of simple reaction time. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 9, 131. ( 10.3389/fnhum.2015.00131) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Milton J, Meyer R, Zhvanetsky M, Ridge S, Insperger T. 2016. Control at stability’s edge minimizes energetic costs: expert stick balancing. J. R. Soc. Interface 13, 20160212. ( 10.1098/rsif.2016.0212) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zana RR, Zelei A. 2020. Introduction of a complex reaction time tester instrument. Period. Polytech. Mech. Eng. 64, 20-30. ( 10.3311/PPme.13807) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stepan G. 2009. Delay effects in the human sensory system during balancing. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 367, 1195-1212. ( 10.1098/rsta.2008.0278) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Allen RW, Hogue JR, Parseghian Z. 1986. Manual control of unstable systems. In Proc. 21st Annu. Conf. on Manual Control, p. 32.1. San Jos, CA: NASA. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zgonnikov A, Lubashevsky I, Kanemoto S, Miyazawa T, Suzuki T. 2014. To react or not to react? Intrinsic stochasticity of human control in virtual stick balancing. J. R. Soc. Interface 11, 20140636. ( 10.1098/rsif.2014.0636) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lupu MF, Sun M, Wang F-Y, Mao Z-H. 2015. Information-transmission rates in manual control of unstable systems with time delays. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 62, 342-351. ( 10.1109/TBME.2014.2352173) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kovacs BA, Milton J, Insperger T. 2019. Virtual stick balancing: sensorimotor uncertainties related to angular displacement and velocity. R. Soc. Open Sci. 6, 191006. ( 10.1098/rsos.191006) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cesonis J, Franklin S, Franklin DW. 2018. A simulated inverted pendulum to investigate human sensorimotor control. In Proc. 2018 40th Annu. Int. Conf. of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC). IEEE.

- 22.Franklin S, Cesonis J, Leib R, Franklin DW. 2019. Feedback delay changes the control of an inverted pendulum. In Proc. 2019 41st Annu. Int. Conf. of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC). IEEE.

- 23.Bormann R, Cabrera JL, Milton J, Eurich CW. 2004. Visuomotor tracking on a computer screen—an experimental paradigm to study the dynamics of motor control. Neurocomputing 58–60, 517-523. (( 10.1016/j.neucom.2004.01.089) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saunders JA. 2004. Visual feedback control of hand movements. J. Neurosci. 24, 3223-3234. ( 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4319-03.2004) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Franklin DW, Reichenbach A, Franklin S, Diedrichsen J. 2016. Temporal evolution of spatial computations for visuomotor control. J. Neurosci. 36, 2329-2341. ( 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0052-15.2016) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Snowden RJ, Freeman TCA. 2004. The visual perception of motion. Curr. Biol. 14, R828-R831. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2004.09.033) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nijhawan R. 2008. Visual prediction: psychophysics and neurophysiology of compensation for time delays. Behav. Brain Sci. 31, 179-198. ( 10.1017/S0140525X08003804) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boussaada I, Niculescu S-I. 2018. On the dominancy of multiple spectral values for time-delay systems with applications. IFAC-PapersOnLine 51, 55-60. ( 10.1016/j.ifacol.2018.07.198) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kovacs BA, Insperger T. 2021. Critical parameters for the robust stabilization of the inverted pendulum with reaction delay: state feedback versus predictor feedback. Int. J. Robust Nonlin. Control, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kovacs BA, Insperger T. 2020. Comparison of pixel-based position input and direct acceleration input for virtual stick balancing tests. Period. Polytech. Mech. Eng. 64, 120-127. ( 10.3311/PPme.13507) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Longobardo GS, Cherniack NS, Fishman AP. 1966. Cheyne-Stokes breathing produced by a model of the human respiratory system. J. Appl. Physiol. 21, 1839-1846. ( 10.1152/jappl.1966.21.6.1839) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Glass L, Beuter A, Larocque D. 1988. Time delays, oscillations, and chaos in physiological control systems. Math. Biosci. 90, 111-125. ( 10.1016/0025-5564(88)90060-0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Milton J, Longtin A, Beuter A, Mackey M, Glass L. 1989. Complex dynamics and bifurcations in neurology. J. Theor. Biol. 138, 129-147. ( 10.1016/S0022-5193(89)80135-3) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nijhawan R, Wu S. 2009. Compensating time delays with neural predictions: are predictions sensory or motor? Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 367, 1063-1078. ( 10.1098/rsta.2008.0270) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Insperger T, Milton J. 2014. Sensory uncertainty and stick balancing at the fingertip. Biol. Cybern. 108, 85-101. ( 10.1007/s00422-013-0582-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brouwer A-M, Brenner E, Smeets JBJ. 2002. Perception of acceleration with short presentation times: can acceleration be used in interception? Percept. Psychophys. 64, 1160-1168. ( 10.3758/BF03194764) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dessing JC, Craig CM. 2010. Bending it like Beckham: how to visually fool the goalkeeper. PLoS ONE 5, 1-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wolpert DM, Ghahramani Z, Jordan MI. 1995. An internal model for sensorimotor integration. Science 269, 1880-1882. ( 10.1126/science.7569931) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kawato M. 1999. Internal models for motor control and trajectory planning. Curr. Opin Neurobiol. 9, 718-727. ( 10.1016/S0959-4388(99)00028-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jordan MI. 1996. Computational aspects of motor control and motor learning. In Handbook of perception and action (eds Heuer H, Keele SW), pp. 71-120. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- 41.McIntyre J, Zago M, Berthoz A, Lacquaniti F. 2001. Does the brain model Newton’s laws? Nat. Neurosci. 4, 693-694. ( 10.1038/89477) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zago M, Lacquaniti F. 2005. Internal model of gravity for hand interception: parametric adaptation to zero-gravity visual targets on earth. J. Neurophysiol. 94, 1346-1357. ( 10.1152/jn.00215.2005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zago M, Lacquaniti F. 2005. Visual perception and interception of falling objects: a review of evidence for an internal model of gravity. J. Neural Eng. 2, S198-S208. ( 10.1088/1741-2560/2/3/S04) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Milton J, Fuerte A, Bélair C, Lippai J, Kamimura A, Ohira T. 2013. Delayed pursuit-escape as a model for virtual stick balancing. Nonlinear Theory Appl. IEICE 4, 129-137. ( 10.1587/nolta.4.129) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from https://github.com/koviub/VirtualBalancing.