Abstract

Background

The Montreal classification categorizes patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) based on their macroscopic disease extent. Independent of endoscopic extent, biopsies through all colonic segments should be retrieved during index colonoscopy. However, the prognostic value of histological inflammation at diagnosis in the inflamed and uninflamed regions of the colon has never been assessed.

Methods

This was a multicenter retrospective cohort study of newly diagnosed patients with treatment-naïve proctitis and left-sided UC. Biopsies from at least 2 colonic segments (endoscopically inflamed and uninflamed mucosa) were retrieved and reviewed by 2 pathologists. Histological features in the endoscopically inflamed and uninflamed mucosa were scored using the Nancy score. The primary outcomes were disease complications (proximal disease extension, need for hospitalization or colectomy) and higher therapeutic requirements (need for steroids or for therapy escalation).

Results

Overall, 93 treatment-naïve patients were included, with a median follow-up of 44 months (range, 2-329). The prevalence of any histological inflammation above the endoscopic margin was 71%. Proximal disease extension was more frequent in patients with histological inflammation in the endoscopically uninflamed mucosa at diagnosis (21.5% vs 3.4%, P = 0.04). Histological involvement above the endoscopic margin was the only predictor associated with an earlier need for therapy escalation (adjusted hazard ratio, 3.69; 95% confidence interval, 1.05-13.0); P = 0.04) and disease complications (adjusted hazard ratio, 4.79; 95% confidence interval, 1.10-20.9; P = 0.04).

Conclusions

The presence of histological inflammation in the endoscopically uninflamed mucosa at the time of diagnosis was associated with worse outcomes in limited UC.

Keywords: histology, Nancy score, prognosis, diagnosis, limited ulcerative colitis

Introduction

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is an idiopathic chronic inflammatory bowel disease characterized by periods of remission, acute exacerbations and an unpredictable disease course.1 Despite recent strides in understanding disease pathogenesis and the availability of new drugs, there is still a considerable proportion of patients who are refractory to therapy, need colectomy, or develop complications, highlighting the need for better predictive markers of disease course.2 The Montreal classification is used to stratify patients with UC according to the endoscopic extent of disease.3 Patients are divided into 3 major subgroups: proctitis with inflammation limited to the rectum (E1), left-sided colitis with inflammation distal to the splenic flexure (E2), and extensive colitis with involvement proximal to the splenic flexure (E3).3, 4 This classification system has prognostic and therapeutic value5 because more extensive disease is usually associated with higher rates of hospitalization, colectomy, and colorectal cancer6, 7 and higher therapeutic requirements than more limited disease.8 Current guidelines recommend that a minimum of 2 biopsies from at least 5 segments are obtained during colonoscopy and collected in separate vials for confirming the diagnosis of UC, even when disease is endoscopically limited to the rectum or left colon.9 However, and despite the emerging importance of histology during follow-up, no study has assessed the predictive role of histological inflammation at diagnosis in disease-related outcomes.10-12 Likewise, no studies have formally assessed the prevalence of histological inflammation proximal to the endoscopically inflamed margin or the clinical implications of these findings.

Herein, we performed a multicenter retrospective study to evaluate the association of histological features in patients with treatment-naïve proctitis and left-sided UC with disease course. We aimed to assess the predictive value of histological inflammation in the endoscopically inflamed and uninflamed mucosa at the time of UC diagnosis.

Methods

Patient Population

This was a multicenter retrospective cohort study. Patients with proctitis (E1) or left-sided (E2) UC were identified at each of the participating centers. All patients except for 1, whose diagnosis was made in 1991, had their incident diagnosis between 2004 and 2019. Overall, 9 centers from 3 countries (Portugal, Denmark, and Malta) participated. Inclusion criteria were newly diagnosed and therapy-naïve patients with an available index colonoscopy with biopsies. Only those patients from whom hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) slides were available from at least 2 different colonic segments (including inflamed and uninflamed mucosa) were included. Patients without a formal diagnosis of UC, those with pancolitis at diagnosis, or those whose biopsies were performed after starting therapy (including topical mesalamine, steroids, or antibiotics) were excluded.

Clinical Features and Outcomes

The baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of patients were recorded. Patients were observed from the date of diagnosis until the last consultation available at each hospital. Severe acute UC was defined according to Truelove and Witts criteria.9 The Montreal classification (based on endoscopic mucosal involvement in the index colonoscopy) was used to evaluate disease extent at diagnosis and during follow-up. Index colonoscopies were reviewed by investigators to confirm limited macroscopic extent (E1 or E2) at diagnosis. Endoscopic severity at diagnosis was classified using the Mayo score and was obtained retrospectively from consulting the colonoscopy reports. Therapies started after diagnosis were recorded. Patient charts were consulted to assess the following outcomes: (1) disease proximal extension (defined as any greater extent of endoscopic inflammation than the one observed in the index colonoscopy); (2) need for UC-related hospitalization; (3) need for therapy escalation (defined as a need to start immunomodulators or biologics after the first 3 months from diagnosis); (4) need for steroids (defined as any need to undergo a steroids course after the first 3 months postdiagnosis); (5) episode of acute severe ulcerative colitis (ASUC), according to Truelove and Witts criteria9; and (6) colectomy. The primary outcomes for this study were any disease complication (proximal disease extension, need for hospitalization or colectomy) and higher therapeutic requirements (need for steroids or for therapy escalation). When several outcomes occurred, the first was considered for analysis. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at Sociedade Portuguesa de Gastrenterologia—CEREGA.13, 14

Histology

Two independent gastrointestinal pathologists (PB and CC) reviewed all the H&E slides, blinded to the clinical and endoscopic data. Each slide was classified according to the Nancy score, which is a validated score in patients with UC.15 The score evaluates histological inflammation through a grading system, where grade 0 is defined as no or mild chronic inflammation, grade 1 as moderate to marked chronic inflammatory infiltrate, grade 2 as mild acute inflammatory cells, grade 3 as moderate to severe acute inflammatory cells, and grade 4 as ulcers.15

Inflammation in endoscopically inflamed mucosa (Mayo score ≥ 1) was classified according to the Nancy score. Since all patients had rectal involvement, the rectal slides were used to assess the histological features in the inflamed mucosa because this was the location with the most severe findings. Patients were categorized into 2 groups to assess the histological severity of the inflamed mucosa: Mild histological inflammation was defined as having a Nancy score ranging from 0 to 2, whereas moderate to severe histological inflammation was defined as a Nancy score ≥ 3.

Histological inflammation in the endoscopically uninvolved mucosa was also ranked using the Nancy score. Histological inflammation was considered to be present if any sign of histological inflammation was present (any Nancy score > 0, with at least mild chronic inflammation). The most inflamed slide was chosen for analysis. Patients were categorized into 2 groups, based on the presence or absence of any of these findings: with or without histological inflammation.

Study Oversight

This study was approved by the institutional review board of each hospital and by the Portuguese National Data Protection Committee.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were generated for patients meeting the inclusion criteria. Chi-square and Fisher exact tests were used to compare categorical variables and dichotomous outcomes, and the Student t test and Mann-Whitney U test were used for analyzing continuous data. The impact of histological severity at diagnosis (in endoscopically inflamed and uninflamed mucosa), along with other well-described prognostic factors in UC (age at diagnosis, disease extent, and endoscopic severity at diagnosis), was studied for each of the primary outcomes using univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis. Each of the recorded outcomes (proximal disease extension, need for hospitalization, ASUC, therapy escalation, steroids, and colectomy) was also studied separately. Follow-up data were censored at the last date of follow-up or at the date of first occurring outcome. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were generated to compare cumulative incidence rates. Multivariate models included age at diagnosis, disease extent (E1 vs E2), Mayo endoscopic score (Mayo < 2 vs ≥ 2), histological severity in the endoscopically inflamed mucosa (Nancy score < 3 vs ≥ 3), and histological inflammation above the endoscopic margin (presence vs absence). Finally, we performed a sensitivity analysis to assess whether histological severity in the inflamed mucosa influenced the outcomes in patients with concomitant histological involvement beyond the endoscopic margin. For this analysis, we looked at patients with severe histological features in the inflamed mucosa (Nancy score ≥ 3) and simultaneous histological inflammation in endoscopically uninflamed mucosa. All data analyses were performed using R studio version 1.2.5033.

Results

Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

Overall, 107 patients were included; of these, 14 were excluded because of incomplete data in medical charts or because biopsies were only performed after starting therapy. Eventually, 93 treatment-naïve patients with limited UC were included. Outcome data were available over a median 44 months of follow-up (range, 2-329). Overall, 54.8% were male, with a mean age at diagnosis of 44 years. At the time of diagnosis, 65.6% of patients had proctitis (E1) and 34.4% had left-sided colitis (E2). The majority were never smokers (60%), 31% were ex-smokers, and 9% were smokers at the time of diagnosis. Most patients (84%) received topical 5-aminosalicylates as their first treatment after diagnosis, with concomitant oral 5-aminosalicylates in 60% of patients. Immunosuppressive therapy was started in 3 patients (2 thiopurines, 1 infliximab). The use of oral or intravenous steroids to induce remission occurred in 13.9% and 2% of all patients, respectively. Baseline characteristics of the study patients are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Study Population

| UC (n = 93) | Inflammation Above Endoscopic Margin (%) | No Inflammation Above Endoscopic Margin (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male (%) | 51 (54.8) | 36 (69) | 16 (31) |

| Age at study inclusion, y, median (range) | 44 (17-88) | 43 (17-88) | 40 (19-75) |

| Disease extent, n (%) | |||

| Proctitis (E1) | 61 (65.6) | 45 (74) | 16 (26) |

| Left-sided colitis (E2) | 32 (34.4) | 21 (66) | 11 (34) |

| Clinical disease activity, n (%) | |||

| Mild | 65 (70) | 43 (65) | 22 (35) |

| Moderate | 27 (29) | 23 (85) | 4 (15) |

| Severe | 1 (1) | 1 (100) | 0 (0) |

| Endoscopic disease activity at baseline, n (%) | |||

| Mayo endoscopic score 1 | 35 (37.9) | 29 (83) | 6 (17) |

| Mayo endoscopic score 2 | 44 (47.8) | 27 (61) | 17 (39) |

| Mayo endoscopic score 3 | 14 (15.2) | 10 (71) | 4 (29) |

| Medication use at baseline | |||

| Topical 5-ASA | 78 (84) | 58 (74) | 20 (26) |

| Oral 5-ASA | 56 (60) | 39 (85) | 17 (15) |

| Thiopurines | 2 (2.2) | 2 (100) | 0 (0) |

| Biologics | 1 (1.1) | 1 (100) | 0 (0) |

| Outcomes during follow-up, n (%) | |||

| Steroids | 20 (21.5) | 17 (85) | 3 (15) |

| Hospitalization | 12 (12.9) | 10 (83) | 2 (13) |

| Therapy escalation | 15 (16.1) | 11 (73) | 4 (27) |

| Proximal extension | 15 (16.1) | 13 (87) | 2 (13) |

| ASUC | 5 (5.4) | 5 (100) | 0 (0) |

| Colectomy | 1 (1.1) | 1 (100) | 0 (0) |

ASUC indicates acute severe ulcerative colitis; 5-ASA, aminosalicylates.

Histological Features in Uninflamed and Inflamed Mucosa at Time of Diagnosis

The distribution of H&E slides is described in Supplementary Table 1. A total of 378 biopsy slides were reviewed. There were an average of 4 slides per patient (range, 2-7). In the endoscopically uninflamed mucosa, 71% (66/93) of patients presented with some degree of histological inflammation at diagnosis. Most patients had mild inflammation (n = 52, 80%), characterized by mild but unequivocal chronic inflammatory infiltrate, because of an increased number of lymphocytes and plasmocytes. The remaining patients had moderate to severe chronic inflammation (5%), with concomitant acute inflammatory infiltrate in 15%. Inflammation above the endoscopic margin occurred most frequently in the right colon (n = 45, 68%), defined as the ascending colon (n = 34), transverse colon (n = 9), or cecum (n = 2). When stratified by disease extent, 68% (30/44) of E1 patients and 71.4% (15/22) of E2 patients had histological inflammation in the right colon. Histological features above the endoscopic margin are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Type and Location of Inflammation Above the Endoscopic Margin

| Nancy Score | n, % | |

|---|---|---|

| Type of microscopic inflammation | ||

| Mild chronic inflammation | 0 | 52 (80) |

| Moderate to severe chronic inflammation | 1 | 3 (5) |

| Chronic infiltrate with mild acute inflammatory infiltrate | 2 | 9 (13) |

| Chronic infiltrate with moderate to severe acute inflammatory infiltrate | 3 | 2 (2) |

| Ulcers | 4 | 0 |

| Location of microscopic inflammation | ||

| Right colon | — | 45 (68) |

| Left colon | — | 21 (32) |

In the endoscopically inflamed mucosa, most patients had severe histological features, defined by a Nancy score of 3 (59.1%) or 4 (18.3%). The histological features in the inflamed (rectal) mucosa are summarized in (Supplementary Figure 1).

Outcomes

During the follow-up, 22.5% (21/93) of patients presented with a disease-related complication, including proximal disease extension, hospitalization, or colectomy, and 22.5% (21/93) needed therapy escalation defined as the need for steroid course or escalation to immunomodulators or biologics. The median time to disease complication and therapy escalation was 36.4 and 38.4 months, respectively. Specifically, 12.9% (12/93) of patients were hospitalized because of acute disease exacerbation; of these 12 patients, 5 (5.4%) required hospitalization for an ASUC episode and 1 eventually required colectomy. Overall, 21.5 % (20/93) of patients needed steroids, with 45% (9/20) of these patients requiring more than 1 course, and 16.1% (15/93) of all patients escalated therapy to immunomodulators (12/93) or biologics (3/93). Regarding disease complications, 16.1% (15/93) of patients had proximal disease extension (Table 1). The frequency of the primary outcomes according to Nancy score and histological inflammation above the endoscopic margin is summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Comparison of the Prevalence of Different Outcomes According to Nancy Score and Microscopic Involvement Above the Endoscopic Margin.

| Variable | Nancy Score | Involvement Above the Endoscopic Margin | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 3 | ≥ 3 | P | Yes | No | P | |

| Therapy requirements | 14% (3/21) | 25% (18/72) | 0.27 | 27% (18/66) | 11% (3/27) | 0.09 |

| Disease complication | 19% (4/21) | 24% (17/72) | 0.99 | 29% (19/66) | 7% (2/27) | 0.03 |

Therapy requirements were defined as a need for therapy escalation or steroids. Disease complication was based on the need for hospitalization, proximal extension, or colectomy.

Inflammation Above the Endoscopic Margin Was the Best Predictor of Outcomes

The results from the univariate and multivariate analysis are presented in Table 4. Patients with histological involvement above the endoscopic margin had a higher prevalence of disease complications (29% vs 7%, respectively; P = 0.03), with a trend toward a higher need for therapy escalation (27% vs 11%, respectively; P = 0.09). Regarding individual outcomes, a higher prevalence of proximal disease extension (21.5% vs 3.4%, respectively, P = 0.04) was observed (Supplementary Table 2). In the univariate analysis, inflammation above the endoscopic margin was associated with a numerically and marginally significantly higher risk of having a disease complication (hazard ratio [HR], 4.2; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.99-18; P = 0.052) and a trend toward a higher need for therapy escalation (HR, 2.8; 95% CI, 0.82-9.4; P = 0.10). In the multivariate analysis, inflammation above the endoscopic margin was associated with an earlier need for therapy escalation (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 3.69; 95% CI, 1.05-13; P = 0.04) and disease complications (aHR, 4.79; 95% CI, 1.10-20.9; P = 0.04; Figs. 1 and 2), even after adjusting for country (therapy escalation: aHR, 4.47; 95% CI, 1.25-15.99; P = 0.03; disease complications: aHR, 5.48; 95% CI, 1.24-24.33; P = 0.03; Supplementary Table 3). Univariate and multivariate analysis for the overall risk of any disease complication is shown in Supplementary Table 4.

Table 4.

Uni- and Multivariate Cox Regression Analysis for the Overall Risk of Therapy Requirements (therapy escalation or need for steroids) and Disease Complications (Hospitalization, Disease Extension, or Colectomy)

| Therapy Requirements | Disease complications | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | P | Multivariate | P | Univariate | P | Multivariate | P | |

| Age at diagnosis | 0.99 (0.96-1.0) | P = 0.33 | 0.98 (0.96-1.0) | P = 0.25 | 0.98 (0.95-1.0) | P = 0.11 | 0.97 (0.95-1.0) | P = 0.07 |

| Endoscopic inflammation at diagnosis (Mayo score < 2 vs ≥ 2) | 1.8 (0.69-4.7) | P = 0.23 | 1.98 (0.71-5.5) | P = 0.19 | 0.98 (0.41-2.4) | P = 0.96 | 1.01 (0.39-2.6) | P = 0.98 |

| Disease extent at diagnosis (Montreal classification E1 vs E2) | 1.5 (0.62-3.5) | P = 0.38 | 1.2 (0.46-3.1) | P = 0.71 | 1.1 (0.45-2.6) | P = 0.84 | 1.11 (0.40-3.1) | P = 0.83 |

| Nancy score (< 3 vs ≥ 3) | 2.0 (0.58-6.8) | P = 0.27 | 2.09 (0.56-7.8) | P = 0.27 | 1.5 (0.5-4.5) | P = 0.47 | 1.86 (0.57-5.6) | P = 0.31 |

| Histologic involvement above the endoscopic margin (yes vs no) | 2.8 (0.82-9.4) | P = 0.10 | 3.69 (1.05-13) | P = 0.04 | 4.2 (0.99-18) | P = 0.052 | 4.79 (1.1-20.9) | P = 0.04 |

Figure 1.

Cox regression multivariate analysis showing time to therapy escalation (steroids, immunomodulators, or biologics) according to the presence of microscopic inflammation above the endoscopic margin (left panel) and histological severity in the endoscopically inflamed mucosa (Nancy score < 3 vs ≥ 3) (right panel).

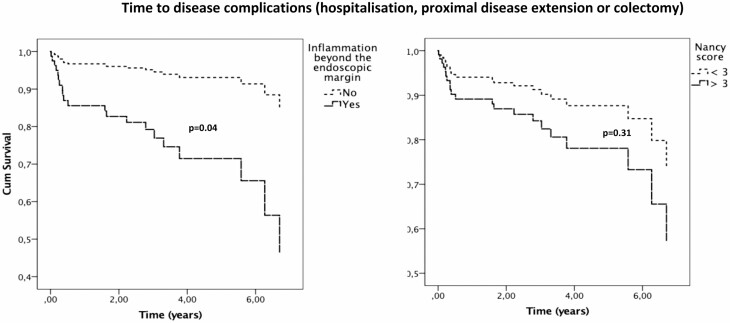

Figure 2.

Cox regression multivariate analysis showing time to disease complication (hospitalization, proximal disease extension, or colectomy) according to the presence of microscopic inflammation above the endoscopic margin (left panel) and histological severity in the endoscopically inflamed mucosa (Nancy score < 3 vs ≥ 3) (right panel).

A higher Nancy score in the endoscopically inflamed mucosa was not associated with higher rates of adverse events. In both the univariate and multivariate analysis, severe histological inflammation (Nancy score ≥ 3) was not associated with any of the primary outcomes during follow-up (disease complications: aHR, 1.86; 95% CI, 0.57-5.61; P = 0.31; therapy requirements: aHR, 2.09; 95% CI, 0.56-7.8; P = 0.27; Figs. 1 and 2).

Finally, age was associated with a trend toward disease complication (aHR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.95-1.0; P = 0.07), without influencing therapy requirements (aHR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.96-1.0; P = 0.25). Disease extent (E1 vs E2) and Mayo endoscopic score (Mayo < 2 vs ≥ 2) were not associated with any of the primary outcomes.

Sensitivity Analysis

We looked at the subgroup of patients who presented with severe rectal inflammation (Nancy score ≥ 3) and concomitant histological involvement above the endoscopic margin. This subgroup of patients (50/93) had a higher prevalence of disease complications (30% vs 14%, P = 0.03). In the multivariate analysis, these patients presented with an earlier need of therapy requirements (aHR, 2.93; 95% CI, 1.10-7.8; P = 0.03) and disease complication (aHR, 2.77; 95% CI, 1.03-7.4; P = 0.04; Supplementary Tables 5 and 6).

Discussion

In this study, we have assessed the predictive role of histological inflammation, in both the endoscopically inflamed and uninflamed mucosa in patients with newly diagnosed limited UC. We observed that the presence of histological inflammation in the endoscopically uninflamed mucosa was associated with higher therapy requirements and a higher incidence of disease-related complications. The Nancy score in the endoscopically inflamed mucosa did not influence the outcomes during follow-up. However, those patients who presented with concomitant severe histological inflammation in the rectum and histological inflammation in the normal-appearing mucosa also had a higher rate of progressing to complications or having greater therapy needs.

There is a pressing need to use prognostic markers that can guide disease monitoring and disease management in patients with UC. Histology is emerging as a new therapeutic target. The presence of acute inflammatory cell infiltrate, crypt abscesses, mucin depletion, and breaches in the surface epithelium have been shown to associate with an increased risk of relapse over a 12-month follow-up.11 Geboes et al10 found a good correlation between the location of the neutrophils and the presence of crypt destruction, erosions, and ulcers, which were associated with clinical relapse. Basal plasmacytosis is a reliable histological feature in UC diagnosis.16 Focal basal plasmacytosis can be seen in the first 15 days of symptoms and becomes more extensive and prevalent with time.16 Therefore, it is usually considered an early sign of UC and can precede architectural changes, such as crypt distortion. Furthermore, basal plasmacytosis in patients with quiescent UC may also have a prognostic value. Its presence in rectal biopsies taken during remission has been associated with disease relapse,17, 18 even though this association has not been consistent.19 The combination of endoscopy and histology seems to provide a better indication of disease activity than endoscopy alone.10 In fact, patients with histological and endoscopic remission seem to have better outcomes compared to those who only achieve endoscopic remission.12

Despite the increasing role of histology as a potential prognostic factor in therapeutic outcomes and disease course, the extent of histological inflammation at the time of diagnosis on UC-related outcomes has never been formally studied. We found that the prevalence of histological inflammation above the endoscopic margin was 71% in our cohort. Because there is no validated histological score to define endoscopic inflammation above the endoscopic margin, we arbitrarily considered histological inflammation in the endoscopically uninvolved mucosa if any sign of histological inflammation was present (any Nancy score > 0). Most patients had mild chronic inflammatory infiltrate, most frequently located in the right colon. The presence of histological inflammation above the endoscopic margin was associated with an earlier need for therapy escalation (aHR, 3.69; 95% CI, 1.05-13.0; P = 0.04) and disease complications (aHR, 4.79; 95% CI, 1.10-20.9; P = 0.04), even after adjusting for other established predictors, including the severity of histological or endoscopic inflammation in the endoscopically inflamed mucosa. These findings are partly in agreement with data showing that the persistence of histological inflammation in quiescent UC is associated with worse outcomes. In a 12-month period retrospective study, Bessissow et al20 showed that 40% of patients with endoscopically quiescent UC had histological inflammatory activity. However, the absence of histological inflammation in quiescent UC was also associated with lower corticosteroid use (HR, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.2-0.9; P = 0.02) and a decreased hospitalization rate (HR, 0.21; 95% CI, 0.1-0.7; P = 0.02) during a 6-year follow-up.21 Therefore, our data suggest that histological inflammation above the endoscopic margin in treatment-naïve patients with limited UC is associated with a higher risk of disease complications and increased therapy requirements.

Unexpectedly, the severity of histological inflammation in the endoscopically inflamed mucosa did not affect therapy requirements (aHR, 2.09; 95% CI, 0.56-7.8; P = 0.27) or disease complications (aHR, 1.86; 95% CI, 0.57-5.61; P = 0.31). There may be several explanations for these findings. In early-stage disease, some histological features may be absent. Histological quantification of the degree of inflammation may be a rough estimate because of sampling error and may lack reproducibility.22 Furthermore, one of the most important histological markers for clinical relapse in quiescent UC is basal plasmacytosis,20, 23 which is not considered in the Nancy score. We hypothesize that the response and histological healing promoted by therapy may have more impact on disease course than the pretreatment severity of inflammation. Notably, many patients received topical therapy during follow-up, which may have been enough to heal the inflamed mucosa but not the inflammation above the endoscopic margin, suggesting that it may be prudent to use oral mesalamine at least in those patients with UC presenting with some inflammation above the endoscopic margin. In our cohort, severe inflammation of the rectum was only associated with worse prognosis when patients also presented with concomitant inflammation above the endoscopic margin. Therefore, inflammation above the endoscopic margin may have a higher impact in proctitis and left-sided UC outcomes, compared to the histological inflammation severity of the endoscopic inflamed mucosa alone.

Consistent with prior observations, we found that advanced age at diagnosis was associated with a trend toward longer intervals to disease complications (aHR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.95-1.0; P = 0.07). Younger age at diagnosis has been consistently considered a risk factor for shorter time to clinical relapse, increased risk for colectomy, poorer response to treatment, and greater disease extension.2 In addition to age at diagnosis (< 40 years) and disease extension, deep ulcers at index colonoscopy and a higher Mayo score are also associated with worse outcomes.24 In univariate and multivariate analysis in our study, Mayo score was not a predictive factor for disease complications or therapy requirements, likely because of a low frequency of patients with a higher Mayo subscore level (only 15.2% of the cohort with Mayo 3 disease). Notably, in a prior work, the severity of endoscopic lesions at diagnosis was not associated with a higher risk for immunosuppressive therapy (multivariate analysis),25 which is in line with our findings with histology, suggesting overall that the pretreatment severity of inflammation may not be as predictive as the initial response to therapy. Finally, there was a male predominance in the group with histological inflammation above the endoscopic margin (69%; Table 1). We performed multivariate analysis including this confounding factor (Supplementary Table 3). Sex was not associated with worse outcomes.

Our study has several strengths. This is the first study to evaluate the prevalence and assess the prognostic value of histological features at the time of diagnosis in treatment-naïve patients with limited UC. This was a multicenter study, including 9 centers with a total of 93 patients and 378 histological slides that were retrieved and centrally reviewed by 2 independent pathologists blinded to clinical outcomes and endoscopic features. Moreover, we used the Nancy score to evaluate the severity of inflammation, which is a validated score in UC.

The limitations of our study include its retrospective design and that therapies that patients were exposed to were not controlled. We included patients diagnosed between 2004 and 2019, which is a long period for inclusion with different technology, endoscopic image quality, and treatment standards. Even though a large number of therapy-naïve patients and H&E slides were analyzed, the strict inclusion criteria yielded a relatively low number of patients to be included per center. After adjusting for country, histologic inflammation above the endoscopic margin remained associated with therapy requirements and disease complications (Supplementary Table 3). Thus, although we cannot fully exclude it, we believe that systematic bias in the generation of the study population may not have occurred. We only had a small proportion of patients with a Mayo 3 endoscopic score at diagnosis, which may have contributed to the lack of its prognostic value during follow-up. We only included E1 and E2 patients, and therefore our findings do not apply to patients with extensive colitis (E3). In addition, some outcomes were relatively rare, in particular colectomy, which may suggest a milder phenotype in our cohort. Because there was no predefined protocol for sampling, we cannot exclude that this may have affected our findings. Nevertheless, for assessing the prognostic value of histology in the inflamed areas we always used biopsies from the rectum, because usually the inflammation in UC is more severe distally. Finally, the Nancy score was not developed to evaluate areas of uninflamed mucosa in UC. However, using a validated score provided us the chance to standardize the assessment of histological findings.

Conclusions

In summary, we found that in treatment-naïve limited UC, histological involvement above the endoscopic margin was associated with a higher risk of adverse outcomes including proximal extension, earlier need for therapy requirements, and disease complications. The severity of histological inflammation in endoscopically inflamed mucosa was not a prognostic factor alone. Our findings support the practice to collect biopsies from uninflamed areas in E1 and E2 patients during index colonoscopy, not only for diagnostic purposes but also for prognostic information. Therefore, patients with histological involvement above the endoscopic margin, especially if associated with severe rectal inflammation, may benefit from a more intensive follow-up and treatment. Prospective studies are needed to confirm our findings.

Supplementary Material

Author contributions: CFG, PB, and JT contributed to the manuscript concept and design. Each center independently extracted clinical data and provided unidentified slides. PB and CC centrally reviewed the pathology slides from all the included patients. AA and MA performed the statistical analysis. CFG and JT wrote the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript and have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Supported by: This work was supported by a research grant by the Núcleo de Gastrenterologia dos Hospitais Distritais—Grants 2018. The RedCap eCRF development was supported by the Portuguese Society of Gastroenterology through its platform for multicenter studies, CEREGA. RCU is supported by a National Institutes of Health K23 Career Development Award (K23KD111995-01A1).

Conflicts of interest: JT received speaker fees from Janssen and consulting fees from Arena Pharmaceuticals, Gilead, and Galapagos. JB reports personal fees from AbbVie, Janssen-Cilag, Celgene, MSD, Pfizer, Takeda, Tillots Pharma, and Samsung Bioepis, and grants from MSD, Takeda, Tillots Pharma, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Novo Nordisk, outside the submitted work. PB received speaker fees from Roche, MSD, AstraZeneca, Novartis, and Bayer, outside the submitted work. RCU has served as an advisory board member or consultant for Eli Lilly, Janssen, Pfizer, and Takeda and has received research support from AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Pfizer.

References

- 1. Ungaro R, Mehandru S, Allen PB, et al. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 2017;389:1756–1770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Reinisch W, Reinink AR, Higgins PD. Factors associated with poor outcomes in adults with newly diagnosed ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:635–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Silverberg MS, Satsangi J, Ahmad T, et al. Toward an integrated clinical, molecular and serological classification of inflammatory bowel disease: report of a Working Party of the 2005 Montreal World Congress of Gastroenterology. Can J Gastroenterol. 2005;19 Suppl A:5A–36A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Monstad I, Hovde O, Solberg IC, et al. Clinical course and prognosis in ulcerative colitis: results from population-based and observational studies. Ann Gastroenterol. 2014;27:95–104. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Torres J, Caprioli F, Katsanos KH, et al. Predicting outcomes to optimize disease management in inflammatory bowel diseases. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10:1385–1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wanderås MH, Moum BA, Høivik ML, et al. Predictive factors for a severe clinical course in ulcerative colitis: results from population-based studies. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther. 2016;7:235–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dias CC, Rodrigues PP, da Costa-Pereira A, et al. Clinical predictors of colectomy in patients with ulcerative colitis: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9:156–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dignass A, Eliakim R, Magro F, et al. Second European evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis part 1: definitions and diagnosis. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6:965–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Magro F, Gionchetti P, Eliakim R, et al. ; European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation [ECCO] . Third European evidence-based consensus on diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis. Part 1: definitions, diagnosis, extra-intestinal manifestations, pregnancy, cancer surveillance, surgery, and ileo-anal pouch disorders. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:649–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Geboes K, Riddell R, Ost A, et al. A reproducible grading scale for histological assessment of inflammation in ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2000;47:404–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Riley SA, Mani V, Goodman MJ, et al. Microscopic activity in ulcerative colitis: what does it mean? Gut. 1991;32:174–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Park S, Abdi T, Gentry M, et al. Histological disease activity as a predictor of clinical relapse among patients with ulcerative colitis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:1692–1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Harris P, Taylor R, Minor B, et al. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software partners. J Biomed Inf. 2019;95:103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Harris P, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inf. 2009;42:377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Marchal-Bressenot A, Salleron J, Boulagnon-Rombi C, et al. Development and validation of the Nancy histological index for UC. Gut. 2017;66:43–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Feakins RM; British Society of Gastroenterology . Inflammatory bowel disease biopsies: updated British Society of Gastroenterology reporting guidelines. J Clin Pathol. 2013;66:1005–1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bitton A, Peppercorn MA, Antonioli DA, et al. Clinical, biological, and histologic parameters as predictors of relapse in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:13–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Popp C, Stăniceanu F, Micu G, et al. Evaluation of histologic features with potential prognostic value in ulcerative colitis. Rom J Intern Med. 2014;52:256–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jauregui-Amezaga A, López-Cerón M, Aceituno M, et al. Accuracy of advanced endoscopy and fecal calprotectin for prediction of relapse in ulcerative colitis: a prospective study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:1187–1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bessissow T, Lemmens B, Ferrante M, et al. Prognostic value of serologic and histologic markers on clinical relapse in ulcerative colitis patients with mucosal healing. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1684–1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bryant RV, Burger DC, Delo J, et al. Beyond endoscopic mucosal healing in UC: histological remission better predicts corticosteroid use and hospitalisation over 6 years of follow-up. Gut. 2016;65:408–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. DeRoche TC, Xiao SY, Liu X. Review: histological evaluation in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2014;2:178–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Popp C, Mateescu RB. Histologic features with predictive value for outcome of patients with ulcerative colitis. In: New Concepts in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. 2017. https://www.intechopen.com/books/new-concepts-in-inflammatory-bowel-disease/histologic-features-with-predictive-value-for-outcome-of-patients-with-ulcerative-colitis. Accessed March 12, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Carbonnel F, Lavergne A, Lémann M, et al. Colonoscopy of acute colitis. A safe and reliable tool for assessment of severity. Dig Dis Sci. 1994;39:1550–1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lau A, Chande N, Ponich T, et al. Predictive factors associated with immunosuppressive agent use in ulcerative colitis: a case-control study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28:606–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.