Abstract

Objective

To determine the prevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis (CT) and Neisseria gonorrhoeae (NG) in the homeless population in Medellín, Colombia, using molecular diagnostic methods. It also intended to develop a demographic profile, exploring associated factors and the dynamics of the social and sexual interactions of this community.

Design

Cross-sectional study.

Setting

Two homeless care centres in Medellín, Colombia.

Participants

Homeless individuals that assisted to the main homeless care centres of Medellín, Colombia from 2017 to 2019.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The prevalence of CT and NG in this population using qPCR detection, factors associated with CT and NG infection, and the sociodemographic profile of the community.

Results

The prevalence of CT infection was 19.2%, while that of NG was 22.6%. Furthermore, being a female was significantly correlated to CT infection p<0.05 (adjusted OR, AOR 2.42, 95% CI 1.31 to 4.47). NG infection was significantly associated with factors such as: sexual intercourse while having a sexually transmitted infection p<0.05 (AOR 3.19, 95% CI 1.48 to 6.85), having more than 11 sexual partners in the last 6 months p=0.04 (AOR 2.91, 95% CI 1.04 to 8.09) and having daily intercourse p=0.05 (AOR 3.15, 95% CI 1.02 to 9.74).

Conclusions

The prevalence of CT and NG was higher than that reported in the general population. Additionally, females had a higher percentage of infection compared with males.

Keywords: epidemiology, molecular diagnostics, public health, infectious diseases

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This research uses molecular techniques (qPCR) to evaluate urine samples to establish the prevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis (CT) and Neisseria gonorrhoeae (NG) in homeless populations of Medellín, Colombia.

Risk factors associated with infection from CT and NG bacteria were established, and a demographic profile was developed with dynamics of social and sexual interaction.

This is the first study that has used a sample of 500 homeless individuals in order to determine the prevalence of NG and CT in Colombia.

Every piece of data regarding sociodemographic profiles and sexual behaviours was collected through a primary source.

The main limitation was that the recruitment of the sample was carried out solely in homeless shelters of Medellín by the mayor’s office, accommodations that cover roughly 70% of the target population.

Introduction

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) have proven to be a global public health problem, as they are one of the most common acute conditions that affect populations around the world. Moreover, they are known to afflict people of any socio-economic level, age, and sex who have had contact with an infected person’s fluids via unprotected intercourse, blood transfusions or vertical transmission.1

In that matter, Chlamydia trachomatis (CT) and Neisseria gonorrhoeae (NG) are the second and third causes of STIs in the world, with an estimated prevalence of 4.2% in women and 2.7% in men for CT1 and 0.9% in women and 0.7% in men for NG.2 CT is asymptomatic in 70% of women and 50% of men, and it is responsible in many cases for pelvic inflammatory disease, ectopic pregnancy, endometritis and infertility. NG infection is highly symptomatic in men, causing dysuria and purulent discharge, epididymitis, prostatitis and infertility.3

Regarding Latin America, STIs caused by CT and NG have proven to be a serious public health problem, given the lack of resources in different clinical settings for diagnosis and treatment, and the scarce epidemiological research in this region. All of this combined with the high prevalence of both diseases (CT infection prevalence is 7.6% in women and 1.8% in men, and NG infection prevalence is 0.8% in women and 0.7% in men).1

Moreover, CT is a big concern in Colombia, since it is the most reported STI in the country, with a prevalence of 2% in asymptomatic people and 7% to 9.8% in the general population with lower genital tract symptoms. Meanwhile, even though NG prevalence is lower (1.5% to 3%), chlamydial coinfection with NG has been reported in 10%–40% of NG infection cases, and it has been showing increased antibiotic resistance.4 However, since these infections are not notifiable diseases, there is little data on the prevalence of these infections stratified in high-risk populations in Latin America, such as homeless persons.5

A homeless person is defined as someone whose life takes place mainly on the street, as a physicalsocial space, where they solve their vital needs, builds affective relationships and sociocultural mediations, structuring a lifestyle.6 The last census of homeless persons in Medellín, Colombia, was carried out in 2019 by the National Administrative Department of Statistics where 3214 people were reported to live in this situation of which 14.8% were women and 85.2% were men.7

Additionally, the homeless population is especially vulnerable to STIs, as their prevalence reaches up to 52.5%.8 This is due to various known high-risk behaviours that are common in this community (unprotected sexual intercourse, multiple sexual partners, sex work and the use of psychoactive substances while engaging in intercourse.8–11 Currently, there is no in-depth research regarding CT and NG in the homeless population of Colombia. Therefore, this study aimed to determine the prevalence of CT and NG in this community in Medellín, Colombia, using molecular diagnostic methods. It also intended to develop a demographic profile exploring associated factors and the dynamics of the social and sexual interactions of this community.

Materials and methods

This is a cross-sectional quantitative study, which primarily used information from a survey of a homeless population between 15 and 88 years of age, who attended different institutions of the mayor’s office in Medellín, Colombia. It also used laboratory testing in urine samples provided by the study subjects to detect CT and NG.

Sampling methods and recruitment

The sample size was calculated using the finite population method,12 and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention software, Epi info. This was performed using information from the census of homeless persons living Medellín in 2010,13 considering a total homeless population of 3381 persons. The sampling error was set at 5% and the CI was set at 97%. The result of this calculation was n=413, but it was rounded up to 500.

The information in this study was gathered from November 2017 to May 2019 in the Medellín homeless care centres, which are frequented by about 1836 persons each day,7 from which participants were randomly selected. In order to ensure unbiased randomisation, we used the systematic sampling method, in which the sampling interval was one selected case every seven persons, with weekly visits over the span of 18 months. The sample interval was calculated by dividing the total homeless population in Medellín (N=3381),13 by the calculated sample size (n=500).

The criteria for eligible participants were: (1) having ever engaged in sexual activity and (2) being a homeless individual. They signed an informed consent form; those under 18 years of age signed an assent form and were accompanied by the family defender from the institutions where they were being cared for. The subjects were excluded from the study if they had visible clinical signs of inebriation or an altered mental state.

Data collection

A structured electronic survey was administered to each participant by a member of the research team. It contained 89 questions pertaining to sociodemographics, sexual behaviours, previous STI infection and treatment, consumption of psychoactive substances, educational aspects and general knowledge of sexual health and STIs. This survey aimed to identify different risk factors and to establish the population profile. The questions can be found in online supplemental material 1.

bmjopen-2021-054966supp001.pdf (33.5KB, pdf)

Sample collection

Urine samples were obtained by self-collection. The first day that the patients were recruited, they received instructions and 30 mL sample bottles to collect the first urination of the next day or after 4 hour retention. The staff of the homeless care centres were aware of the patient’s participation in the study and made sure that the patients did not forget the instructions and ensured a correct urine sample collection. The staff also refrigerated the samples, which were then shipped by the researchers early that same morning to the laboratory that is located less than 2 km away from the centre (<5 min by car).

Laboratory testing

In the laboratory, each sample was tested for CT and NG infection. The urine was processed for DNA extraction, using the commercial QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Handbook (Qiagen, Germany). Nested PCR was performed to detect the cryptic plasmid and the MOMP gene from CT. This procedure was also used to detect the porin protein gene (por) and transferrin binding protein β subunit gene from NG. Each PCR run was performed using positive and negative controls. PCR was considered positive when at least one of the amplicons was detected. In negative cases, qPCR was performed with the same primers, using the Luna Universal qPCR Mix kit (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, Massachusetts, USA).

The molecular sensitivity of both PCRs was established with logarithmic dilutions from 10 ng/µL to 1.0 fg/μL of the cloned CT and NG DNA fragment and was defined as the minimum DNA concentration detected by the nested PCR. Analytical specificity was defined as the ability of the different CT and NG primers to exclusively identify the gene from the microorganism of interest with 100% identity and was determined in silico using the National Center for Biotechnology Information database.14

Statistical analyses

The data obtained in the questionnaire as well as the results of the qPCR for each participant were transferred to the statistical package SPSS version 24 (licensed by the University of Antioquia—Colombia).

First, a general descriptive analysis was carried out, then the polytomous variables were recategorised, and a bivariate analysis was performed, in order to calculate the association between variables with χ2, contemplating a p<0.05 as a statistically significant association. The OR was calculated with 95% CIs for both CT and NG infections.

Finally, to calculate the adjusted OR (AOR), a binary logistic regression model was carried out, using the variables that previously had a p<0.05 in the bivariate analysis.

Patient and public involvement

Informative sessions were held in the homeless care centres of the mayor’s office in Medellín, Colombia, to present the problem, raise awareness among the population, and explain the objectives of the study. Patients were not compensated monetarily for their participation in the study, but they were given their PCR results free of charge and were also directed to governmental healthcare programmes that prescribed medicine and provided their infections at no cost. Additionally, symptomatic and clinical follow-up after treatment was performed by a medical doctor of the institution for every subject in order to ensure the eradication of the infection.

Results

Study population characteristics

Between November 2017 and May 2019, 500 individuals that met the inclusion criteria completed the survey conducted by a professional and provided urine samples for the detection of CT and NG. The characteristics of all subjects are shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of all participants

| Variables | n (%) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 352 (70.4) |

| Female | 148 (29.6) |

| Age | |

| 13–22 | 50 (10.0) |

| 23–32 | 162 (32.4) |

| 33–42 | 146 (29.2) |

| 43–52 | 75 (15.0) |

| 53–62 | 59 (11.8) |

| 63–72 | 7 (1.4) |

| >73 | 1 (0.2) |

| Gender identity | |

| Heterosexual | 422 (84.4) |

| Lesbian | 16 (3.2) |

| Gay | 9 (1.8) |

| Bisexual | 43 (8.6) |

| Transgender | 10 (2.0) |

| Birthplace | |

| Medellín | 279 (55.8) |

| Other | 221 (44.2) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 341 (68.2) |

| Civil union | 94 (18.8) |

| Married | 25 (5.0) |

| Other | 40 (8.0) |

| Highest educational level (grades) | |

| No education | 33 (6.6) |

| Basic primary (1–5) | 177 (35.4) |

| Basic Secondary (6–9) | 158 (31.6) |

| Secondary (10–11) | 100 (20.0) |

| Technical/technological level | 21 (4.2) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 10 (2.0) |

| Master’s degree | 1 (0.2) |

| Children, n | |

| None | 197 (39.4) |

| <3 | 208 (41.6) |

| 3–4 | 64 (12.8) |

| >4 | 31 (6.2) |

| Source of income* | |

| Street sales | 217 (43.4) |

| Recycling | 126 (25.2) |

| Panhandling | 114 (22.8) |

| Running errands | 78 (15.6) |

| Sex work | 54 (10.8) |

| Selling drugs | 54 (10.8) |

| Assistance from family or friends | 46 (9.2) |

| Government assistance | 11 (2.2) |

| Other | 38 (7.6) |

| Daily psychoactive substance consumption* | |

| Tobacco | 300 (60.0) |

| Marijuana | 234 (46.8) |

| Cocaine/cocaine derivatives | 312 (62.4) |

| Alcohol | 122 (25.6) |

| Pills (unspecified) | 57 (11.4) |

| Inhalant abuse | 55 (11.0) |

| MDMA (ecstasy, molly)† | 11 (2.2) |

| Other substances | 42 (8.4) |

| No daily consumption | 48 (9.6) |

| Sexual partners in lifetime | |

| No Answer | 20 (4.0) |

| <50 | 381 (76.2) |

| 50–100 | 45 (9.0) |

| >100 | 54 (10.8) |

| Sexual partners in the last 6 months | |

| No answer | 22 (4.4) |

| <11 | 426 (85.2) |

| 11–50 | 35 (7.0) |

| >50 | 17 (3.4) |

| Age of first sexual activity | |

| No answer | 5 (1.0) |

| <10 | 58 (11.6) |

| 10–14 | 253 (50.6) |

| >14 | 184 (36.8) |

| Use of contraception* | |

| Females | |

| Condoms | 56 (37.8) |

| Tubal ligation | 55 (37.2) |

| Implants | 42 (28.4) |

| Injections | 8 (5.4) |

| Pills | 4 (2.7) |

| Others | 2 (1.4) |

| None | 28 (18.9) |

| Males | |

| Condoms | 260 (73.9) |

| None | 92 (26.1) |

| Condom use in the last 3 months* | |

| Yes | 204 (40.8) |

| No | 296 (59.2) |

| Committed partner* | 173 (58.4) |

| Casual partner(s)* | 203 (68.6) |

| Consent in past sexual encounters | |

| Females | |

| Non-consensual | 64 (43.2) |

| Consensual | 67 (45.3) |

| No answer | 17 (11.5) |

| Males | |

| Non-consensual | 41 (11.6) |

| Consensual | 284 (80.7) |

| No answer | 27 (7.7) |

| Frequency of intercourse | |

| No answer | 44 (8.8) |

| Daily | 37 (7.4) |

| 2–3 times a week | 115 (23.0) |

| 2–3 times a month | 187 (37.4) |

| At least once in the last 3 months | 73 (14.6) |

| At least once in the last 6 months | 44 (8.8) |

*Survey respondents could choose more than one option.

†Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA), commonly known as ecstasy or molly.

Additionally, 41.9% of the females and 38.9% of the males surveyed reported having an STI during their lifetime (p=0.535). Of these past self-reported STIs, gonorrhoea was the most common among men (23.3%), and syphilis among women (33.8%). Furthermore, 37.9% of heterosexuals, 55.8% of bisexuals, 33.3% of gay men, 37.5% of lesbians and 60% of transgender persons reported having a past STI in their lifetime. Among the latter group, 50% reported past syphilis infections.

Sex work was performed by 24.3% of women and 5.1% of men (p<0.001). A statistically significant difference was also observed between sexual orientation and sex work (p<0.001), finding that it was performed by 5.7% of the heterosexual population, 6.3% of lesbian, 44.4% of gay men, 34.9% of the bisexual population and 100% of transgender people. In addition, 25.9% of those who performed sex work reported an STI in their lifetime. It was found that 13.1% of men and 0.7% of women paid for sexual services (p<0.001).

Prevalence of CT and NG by qPCR

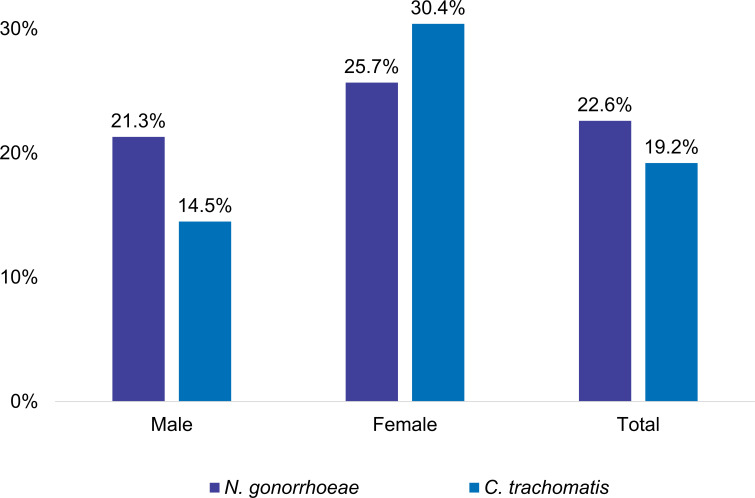

The diagnosis of CT and NG was done by qPCR (figure 1). The results show a 22.6% prevalence of NG infection (n=113), and a 19.2% prevalence of CT infection (n=96) for the general population. Moreover, infection caused by a single agent was 14.6% (n=73) for CT and 18.0% (n=90) for NG. Coinfection occurred in 4.6% (n=23).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of gonorrhoea and chlamydia infections by gender.

In males, the prevalence of CT and NG was 14.5% and 21.3% respectively, while in females it was 30.4% for CT and 25.7% for NG. A statistically significant difference in CT prevalence was found between men and women (p≤0.001). On the contrary, for NG, this difference was not significant (p=0.286).

Factors associated with CT and/or NG infection

Table 2 shows the results of different factors associated with CT infection. It is observed that the consumption of MDMA (ecstasy), toluene inhalants and cocaine while having sex increases the chances of infection 2.37, 2.49 and 3.30 times, respectively (p<0.05), in contrast with the people who did not consume these substances during intercourse.

Table 2.

Factors associated with Chlamydia trachomatis infection—OR

| Variable | C. trachomatis qPCR test | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) |

P value χ2 |

|||

| Positive | Negative | |||||

| n | % | n | % | |||

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 45 | 46.9 | 103 | 25.5 | 2.58 (1.63 to 4.08) | <0.001 |

| Male | 51 | 53.1 | 301 | 74.5 | ||

| Children | ||||||

| Yes | 71 | 74 | 232 | 57.4 | 2.11 (1.28 to 3.46) | 0.003 |

| No | 25 | 26 | 172 | 42.6 | ||

| Has been taught how to use a condom | ||||||

| No | 20 | 20.8 | 44 | 10.9 | 2.15 (1.2 to 3.86) | 0.009 |

| Yes | 76 | 79.2 | 360 | 89.1 | ||

| Consumption of glue/inhalant during intercourse | ||||||

| Yes | 13 | 13.5 | 25 | 6.2 | 2.37 (1.17 to 4.84) | 0.015 |

| No | 83 | 86.5 | 379 | 93.8 | ||

| MDMA (ecstasy, molly) consumption during intercourse* | ||||||

| Yes | 10 | 10.4 | 18 | 4.5 | 2.49 (1.11 to 5.59) | 0.022 |

| No | 86 | 89.6 | 386 | 95.5 | ||

| Consumption of cocaine during intercourse | ||||||

| Yes | 6 | 6.3 | 8 | 2 | 3.30 (1.12 to 9.75) | 0.023 |

| No | 90 | 93.8 | 396 | 98 | ||

| Frequent irritation or discomfort symptoms | ||||||

| Yes | 9 | 9.4 | 16 | 4 | 2.51 (1.07 to 5.86) | 0.029 |

| No | 87 | 90.6 | 388 | 96 | ||

| Condom use with casual partner | ||||||

| No | 41 | 62.1 | 128 | 47.9 | 1.18 (1.03 to 3.09) | 0.039 |

| Yes | 25 | 37.9 | 139 | 52.1 | ||

| Domestic violence | ||||||

| Yes | 29 | 35.4 | 91 | 24.3 | 1.70 (1.02 to 2.84) | 0.040 |

| No | 53 | 64.6 | 283 | 75.7 | ||

| Number of sexual partners in lifetime | ||||||

| >100 | 16 | 17.2 | 38 | 9.8 | 1.91 (1.01 to 3.6) | 0.043 |

| <100 | 77 | 82.8 | 349 | 90.2 | ||

| Urethral discharge | ||||||

| Yes | 6 | 11.8 | 15 | 5 | 2.54 (0.94 to 6.89) | 0.059 |

| No | 45 | 88.2 | 286 | 95 | ||

| Consent in past sexual encounters | ||||||

| Non-consensual | 25 | 30.5 | 80 | 21.4 | 1.61 (0.95 to 2.74) | 0.076 |

| Consensual | 57 | 69.5 | 294 | 78.6 | ||

| Sleeping in a homeless care centre | ||||||

| Yes | 84 | 87.5 | 322 | 79.7 | 1.78 (0.93 to 3.42) | 0.079 |

| No | 12 | 12.5 | 82 | 20.3 | ||

| Heroin consumption | ||||||

| Yes | 9 | 9.4 | 19 | 4.7 | 2.10 (0.92 to 4.79) | 0.074 |

| No | 87 | 90.6 | 385 | 95.3 | ||

| Sexual partners in the last 6 months | ||||||

| >50 | 6 | 6.6 | 11 | 2.8 | 2.41 (0.87 to 6.71) | 0.082 |

| <50 | 85 | 93.4 | 376 | 97.2 | ||

| Condom use | ||||||

| No | 39 | 40.6 | 145 | 35.9 | 1.22 (0.78 to 1.93) | 0.387 |

| Yes | 57 | 59.4 | 259 | 64.1 | ||

| Has had Syphilis in their lifetime | ||||||

| Yes | 24 | 25 | 83 | 20.5 | 1.29 (0.77 to 2.17) | 0.339 |

| No | 72 | 75 | 321 | 79.5 | ||

| Sex work | ||||||

| Yes | 12 | 12.5 | 42 | 10.4 | 1.23 (0.62 to 2.44) | 0.550 |

| No | 84 | 87.5 | 362 | 89.6 | ||

| Cannabis consumption | ||||||

| Yes | 60 | 62.5 | 294 | 72.8 | 0.62 (0.39 to 1.00) | 0.047 |

| No | 36 | 37.5 | 110 | 27.2 | ||

*Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA), commonly known as ecstasy or molly.

Table 3 shows the results of different factors associated with an NG infection. Among the most relevant, it is observed that transgender people are 5.37 times more likely to contract the infection than the rest of the population, with a statistically significant difference (p=0.004). A binary logistic regression model was performed to adjust the OR of CT infection with the potential associated factors. Table 4 shows that being a woman significantly increased the chances of infection (AOR=2.42, 95% CI 1.31 to 4.47), (p=0.00).

Table 3.

Factors associated with Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection—OR

| Variable | Neisseria gonorrhoeae qPCR test | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) |

P value χ2 |

|||

| Positive | Negative | |||||

| N | % | N | % | |||

| Gender identity | ||||||

| Transgender | 6 | 5.3 | 4 | 1 | 5.37 (1.49 to 19.37) | 0.00 |

| Non-transgender people | 107 | 94.7 | 383 | 99 | ||

| Last Pap Smear test | ||||||

| >1 year ago | 30 | 81.1 | 64 | 61.5 | 2.68 (1.08 to 6.67) | 0.03 |

| <1 year ago | 7 | 18.9 | 40 | 38.5 | ||

| Place for personal hygiene | ||||||

| Public place | 107 | 94.7 | 341 | 88.1 | 2.41 (1.00 to 5.79) | 0.04 |

| House, apartment | 6 | 5.3 | 46 | 11.9 | ||

| Had sexual contact while having an STI | ||||||

| Yes | 24 | 57.1 | 57 | 36.3 | 2.34 (1.17 to 4.67) | 0.02 |

| No | 18 | 42.9 | 100 | 63.7 | ||

| Frequency of intercourse | ||||||

| Daily | 15 | 13.3 | 22 | 6.4 | 2.23 (1.12 to 4.47) | 0.02 |

| Once a week or less | 98 | 86.7 | 321 | 93.6 | ||

| Sexual partners in the last 6 months | ||||||

| >11 partners | 19 | 17.3 | 33 | 9 | 2.12 (1.15 to 3.90) | 0.01 |

| <10 partners | 91 | 82.7 | 335 | 91 | ||

| HIV | ||||||

| Positive | 6 | 5.3 | 10 | 2.6 | 2.11 (0.75 to 5.95) | 0.09 |

| Negative | 107 | 94.7 | 377 | 97.4 | ||

| Type of sexual intercourse (last time) | ||||||

| Oral and/or anal | 17 | 15 | 31 | 8 | 2.03 (1.08 to 3.83) | 0.03 |

| Vaginal | 96 | 85 | 356 | 92 | ||

| Sleeping in a homeless care centre | ||||||

| Yes | 99 | 87.6 | 307 | 79.3 | 1.84 (1.00 to 3.40) | 0.05 |

| No | 14 | 12.4 | 80 | 20.7 | ||

| Number of sexual partners in lifetime | ||||||

| >100 | 18 | 16.1 | 36 | 9.8 | 1.77 (0.96 to 3.25) | 0.07 |

| <100 | 94 | 83.9 | 332 | 90.2 | ||

| Sex work | ||||||

| Yes | 17 | 15 | 37 | 9.6 | 1.68 (0.90 to 3.11) | 0.10 |

| No | 96 | 85 | 350 | 90.4 | ||

| Last sexual contact | ||||||

| Commercial sex | 27 | 23.9 | 66 | 17.1 | 1.53 (0.92 to 2.54) | 0.10 |

| Stable or casual | 86 | 76.1 | 321 | 82.9 | ||

| Domestic violence | ||||||

| Yes | 35 | 31 | 85 | 24.8 | 1.36 (0.85 to 2.18) | 0.20 |

| No | 78 | 69 | 258 | 75.2 | ||

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 38 | 33.6 | 110 | 28.4 | 1.28 (0.82 to 2.00) | 0.29 |

| Male | 75 | 66.4 | 277 | 71.6 | ||

STI, sexually transmitted infection.

Table 4.

Factors associated with Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection—Adjusted OR

| Bacteria | Risk factor | B | P value Wald |

Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

| N. gonorrhoeae | Sexual intercourse while having an STI | 1.16 | 0.00 | 3.19 (1.48 to 6.85) |

| >11 sexual partners in the last 6 months | 1.07 | 0.04 | 2.91 (1.04 to 8.09) | |

| Daily sexual relations | 1.15 | 0.05 | 3.15 (1.02 to 9.74) | |

| C. trachomatis | Being a woman | 0.88 | 0.00 | 2.42 (1.31 to 4.47) |

| No condom use with casual partners | 0.44 | 0.13 | 1.56 (0.87 to 2.77) | |

| Children | 0.42 | 0.17 | 1.52 (0.83 to 2.78) | |

| >100 sexual partners in lifetime | 0.42 | 0.26 | 1.52 (0.73 to 3.14) |

STI, sexually transmitted infection.

For NG, a binary logistic regression model was also performed (table 4), finding that having intercourse while having an STI confers 3.19 times more chances of having an NG infection than those who avoid them. Another associated factor was having more than 11 sexual partners during the last 6 months (AOR 2.91, 95% CI 1.04 to 8.09), (p=0.04) and having daily intercourse (AOR 3.15, 95% CI 1.02 to 9.74), (p=0.05).

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study, we determined the prevalence of CT and NG in the homeless population of Medellín, Colombia using molecular diagnostic methods. We also developed a demographic profile exploring associated factors and the dynamics of the social and sexual interactions of the population. This study identified that approximately one in five homeless individuals residing in Medellín, Colombia was infected with CT or NG. It also found that females had approximately double the prevalence of infection by CT compared with males.

The prevalence found for NG and CT in the study population was 22.6% and 19.2%, respectively; being higher than that reported in the general population (♀ CT: 4.2%, NG: 0.8%; ♂ CT: 2.7%, NG: 0.6%).1 Also, in the present research, the coinfection between CT and NG was 4.6%, which was higher compared with other papers, where the coinfection prevalence varied from 1.7% in juvenile detention centres in the USA15 to 2.9% in sex workers.16 All of this can be explained due to the fact that, unlike other studies, the researched sample was composed exclusively by homeless persons. This population presents multiple and simultaneous high-risk behaviours8–11 17 such as sex work, the lack of condom use, intercourse while consuming psychoactive substances, ignorance about STIs and multiple sexual partners. Also, another study performed in the USA, found a lower prevalence on both CT (6.4%–6.7%) and NG 0.3%–3.2% in homeless persons.8 This is due to the difference both in the quality of education in STI prevention and the government’s social assistance programmes focusing on preventive healthcare between Colombia (a low/middle-income country) and other highly developed nations.18

The prevalence of CT and NG infection was higher in women (CT: 30.4% in women and 14.5% in men; NG 25.7% in women and 21.3% in men). This is consistent with the results reported by the WHO and other researchers.1 19 20 Similar studies confirm that the CT prevalence between women and men presents significant differences, where it was reported in 31.7% of women and 9.2% of men.21 The higher prevalence in women is likely due to the predominance of asymptomatic infections which leads to an alarming rate of subdiagnosis, subsequently leaving a lot of untreated and chronic cases among females compared with males.22 On the other hand, infection by CT in males is more evident, as it is symptomatic to a greater extent (mainly dysuria, urethral discharge and testicular pain).23 Therefore, it is possible that a broader number of infected males had previously sought medical attention for genital irritative symptoms, which were then treated somewhat successfully. Regarding NG, there is a differential gene expression between men and women during the infection process, as well as differences in the pathogenic mechanisms used by this bacterium to infect the male and female epithelium, which define the evolution of the infection and the host’s presentation of symptoms.24 25

Regarding the demographic profile, some variables such as substance use, income source and the distribution by age groups and sex, behaved similarly in this study and in Colombia’s census of homeless persons performed in 2019.7 This study observed that the sample was predominantly composed of males (70.4%), and these results are comparable to those previously reported locally26 27 and in other countries such as the USA (66.4% homeless males)8 and Spain (90% homeless males).28

Furthermore, several studies determined risk factors associated with STIs, such as domestic violence, use of psychoactive substances, a history of incarceration, multiple sexual partners, non-use of condoms, lack of education about STIs, feelings of affection towards the partner and not prioritising the well-being of their own or others.8 10 11 Correspondingly, in this study, we found that 59.2% of the individuals indicated that they did not use a condom in the 3 months prior to the survey, which was encountered more frequently when people had intercourse with a committed partner. This can be explained because according to the participants, there was trust or affection with their partner.

Another significant finding in this study was that methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) and cocaine use was significantly associated with CT infection (p=0.02). This can be attributed to the fact that being under the influence of psychoactive substances can lead homeless persons to engage in risky sexual behaviours.29 Additionally, the most frequent STIs in the survey of this study were syphilis (21.4%), gonorrhoea (19.4%) and HIV (3.2%). Similar results were found both by national11 27 and international8 30 31 studies performed in homeless populations.

This research had limitations related to the recruitment of the sample. This was mainly because the application of surveys and collection of urine samples was carried out solely in homeless shelters of Medellín by the mayor’s office, accommodations that cover roughly 70% of the target population, according to the 2019 Census.7 This was necessary because of the low-security conditions in other areas of the city where homeless persons reside.

Finally, it is imperative that governmental entities and policy-makers implement epidemiological surveillance programmes performing molecular techniques in non-invasive samples to improve the diagnosis of STIs in populations at risk, such as homeless persons. Additionally, future research should focus both on implementing molecular techniques in the detection of STIs and developing an ample sociodemographic profile, which allows the researcher to explore the risk factors more in depth. Also, future investigations should perform stratified analyses both in the general population and in high-risk groups, to have a broader view of the health situation and consequently implement more focused social assistance programmes that tackle these sexual health issues directly.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

To the Corporation for Biological Research (CIB), especially Dr. Óscar Gómez, to the Secretaría de Inclusión Social, Familia y Derechos Humanos of the mayor’s office of Medellín—Colombia and its institutions 'Centro de Diagnóstico y Derivación' and 'Centro Día', to Dr. Lucas Arias Vélez, leader of the 'Programa de atención al habitante de calle', to the religious community 'Carmelitas Misioneras' and the ASPERLA ONG, for their support and accompaniment in the development of this work. To the international advisor, Dr. John Wylie—University of Manitoba—Canada. We would also like to thank Mr. Cameron Hahn for consulting the translation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: DEV-G: guarantor, data collection, statistical data analysis, methodology design, database management, manuscript writing. NT-V: data collection, data analysis, manuscript writing. JCG-Z: data collection, laboratory tests, methodology design, manuscript writing. JGM-O: conceptualisation, methodology design, laboratory tests, manuscript writing. AM: conceptualisation, methodology design, project supervision, manuscript writing. VR-L: data collection, data analysis, manuscript writing. AV-C: conceptualisation, funds and resources management, methodology design, project administration and supervision, and manuscript writing.

Funding: This work was supported by MINCIENCIAS (Ministerio de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación—Colombia) and the University of Antioquia—Colombia. Grant number: 111574455752.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request. Raw data, the database and the survey without any identifiers are available on reasonable request, emailing diegovelezgomez@gmail.com (corresponding author).

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Consent obtained directly from patient(s)

Ethics approval

The consent, informed assent and survey were previously approved by the Bioethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Antioquia—Colombia (Ethics approval number: 2017-022). This study was endorsed by the 'Secretaría de Inclusión Social, Familia y Derechos Humanos' of the mayor’s office of Medellín—Colombia. Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1.Newman L, Rowley J, Vander Hoorn S, et al. Global estimates of the prevalence and incidence of four curable sexually transmitted infections in 2012 based on systematic review and global reporting. PLoS One 2015;10:e0143304. 10.1371/journal.pone.0143304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kirkcaldy RD, Weston E, Segurado AC, et al. Epidemiology of gonorrhoea: a global perspective. Sex Health 2019;16:401–11. 10.1071/SH19061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization WHO . Sexually transmitted diseases. Available: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/sexually-transmitted-infections-(stis) [Accessed 21 Jan 2020].

- 4.Pan American health organization (PAHO). Gonorrea, 2020. Available: https://www3.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=14872:sti-gonorrhea&Itemid=3670&lang=es [Accessed 28 Oct 2021].

- 5.Duarte H, Hernández A, Rodríguez I. Guía de Práctica Clínica para El abordaje sindrómico del diagnóstico Y tratamiento de Los pacientes Con infecciones de transmisión sexual Y otras infecciones del tracto genital.. Available: https://www.minsalud.gov.co/sites/rid/Lists/BibliotecaDigital/RIDE/INEC/IETS/GPC_Comple_ITS.pdf [Accessed 29 Aug 2020].

- 6.Correa ME. La otra ciudad - Otros sujetos: los habitantes de la calle. Trabajo Social 2007;0:37–56. [Google Scholar]

- 7.DANE . Censo Habitantes de la calle. Resultados Medellín Y Área Metropolitana, 2019. Available: https://www.dane.gov.co/index.php/estadisticas-por-tema/demografia-y-poblacion/censo-habitantes-de-la-calle [Accessed 29 Apr 2020].

- 8.Williams SP, Bryant KL. Sexually transmitted infection prevalence among homeless adults in the United States: a systematic literature review. Sex Transm Dis 2018;45:494–504. 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chawla N, Sarkar S. Defining “High-risk Sexual Behavior” in the Context of Substance Use. Journal of Psychosexual Health 2019;1:26–31. 10.1177/2631831818822015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berbesí D, Á S-C, Caicedo B. Prevalence and factors associated with HIV among the street dwellers of medellin, Colombia. Revista Facultad Nacional de Salud Pública 2015;33:181–91. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blandón Buelvas M, Palacios Moya L, Berbesí Fernández D. Infección activa POR sífilis en habitantes de calle Y factores asociados. Revista de Salud Pública 2019;21:1–5. 10.15446/rsap.v21n3.61039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aguilar-Barojas S. Fórmulas para El cálculo de la muestra en investigaciones de salud. Salud en Tabasco 2005;11:333–8. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centro de Estudios de Opinión CEO, Secretaría de Bienestar Social Medellín . Censo de habitantes de calle Y en calle de la ciudad de Medellín Y Sus corregimientos, 2010. Available: https://aprendeenlinea.udea.edu.co/revistas/index.php/ceo/article/view/7073 [Accessed 28 Jul 2019].

- 14.Blast: basic local alignment search tool. Available: https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi [Accessed 18 Nov 2020].

- 15.van Veen MG, Koedijk FDH, van der Sande MAB, et al. Std coinfections in the Netherlands: specific sexual networks at highest risk. Sex Transm Dis 2010;37:416–22. 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181cfcb34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kahn RH, Mosure DJ, Blank S, et al. Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae prevalence and coinfection in adolescents entering selected us juvenile detention centers, 1997-2002. Sex Transm Dis 2005;32:255–9. 10.1097/01.olq.0000158496.00315.04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alvis N, Mattar S, Garcia J. Sexually-Transmitted infection in a high-risk group from Montería, Colombia. Revista de Salud Pública 2007;9:86–96. 10.1590/s0124-00642007000100009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Speak S, TIPPLE G. Perceptions, persecution and Pity: the limitations of interventions for homelessness in developing countries. Int J Urban Reg Res 2006;30:172–88. 10.1111/j.1468-2427.2006.00641.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization WHO . Report on global sexually transmitted infection surveillance, 2018. Available: http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/stis-surveillance-2018/en/ [Accessed 08 Apr 2019].

- 20.León SR, Konda KA, Klausner JD, et al. Chlamydia trachomatis infection and associated risk factors in a low-income marginalized urban population in coastal Peru. Rev Panam Salud Publica 2009;26:39–45. 10.1590/S1020-49892009000700006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Caccamo A, Kachur R, Williams SP. Narrative review: sexually transmitted diseases and homeless Youth-What do we know about sexually transmitted disease prevalence and risk? Sex Transm Dis 2017;44:466–76. 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Detels R, Green AM, Klausner JD, et al. The incidence and correlates of symptomatic and asymptomatic Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae infections in selected populations in five countries. Sex Transm Dis 2011;38:503–9. 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318206c288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huffam S, Chow EPF, Leeyaphan C, et al. Chlamydia infection between men and women: a cross-sectional study of heterosexual partnerships. Open Forum Infect Dis 2017;4:ofx160. 10.1093/ofid/ofx160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Edwards JL, Apicella MA. The molecular mechanisms used by Neisseria gonorrhoeae to initiate infection differ between men and women. Clin Microbiol Rev 2004;17:965–81. 10.1128/CMR.17.4.965-981.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nudel K, McClure R, Moreau M, et al. Transcriptome analysis of Neisseria gonorrhoeae during natural infection reveals differential expression of antibiotic resistance determinants between men and women. mSphere 2018;3:e00312. 10.1128/mSphereDirect.00312-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Otálvaro AF, Arango ME. Accesibilidad de la población habitante de calle a los programas de promoción y prevención establecidos por la resolución 412 de 2000. In: Investigaciones Andina. Vol 11, 2009: 23–35. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berbesi DY, Agudelo A, Segura A. Hiv among the street dwellers of Medellín. Revista Facultad Nacional de Salud Pública 2012;30:310–5. [Google Scholar]

- 28.López-Corbeto E, González V, Bascunyana E, et al. Tendencia Y determinantes de la infección genital POR Chlamydia trachomatis en menores de 25 años. Cataluña 2007-2014. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin 2016;34:499–504. 10.1016/j.eimc.2015.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Castaño Pérez G, Arango Tobón E, Morales Mesa S. Riesgos Y consecuencias de las prácticas sexuales en adolescentes bajo Los efectos de alcohol Y otras drogas. Revista Cubana de Pediatría 2013;85:36–50. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barros CVdeL, Galdino Júnior H, Rezza G, et al. Bio-behavioral survey of syphilis in homeless men in central Brazil: a cross-sectional study. Cad Saude Publica 2018;34:e00033317. 10.1590/0102-311x00033317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keizur EM, Goldbeck C, Vavala G, et al. Safety and effectiveness of same-day Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae screening and treatment among gay, bisexual, transgender, and homeless youth in Los Angeles, California, and new Orleans, Louisiana. Sex Transm Dis 2020;47:19–23. 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000001088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-054966supp001.pdf (33.5KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request. Raw data, the database and the survey without any identifiers are available on reasonable request, emailing diegovelezgomez@gmail.com (corresponding author).