Abstract

Objectives

To assess the psychological well-being of pregnant women at increased risk of spontaneous preterm birth, and the impact of care from a preterm birth clinic.

Design

Single-centre longitudinal cohort study over 1 year, 2018–2019.

Setting

Tertiary maternity hospital in Auckland, New Zealand.

Participants

Pregnant women at increased risk of spontaneous preterm birth receiving care in a preterm birth clinic.

Intervention

Participants completed three sets of questionnaires (State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale, and 36-Item Short Form Survey)—prior to their first, after their second, and after their last clinic appointments. Study-specific questionnaires explored pregnancy-related anxiety and perceptions of care.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The primary outcome was the mean State-Anxiety score. Secondary outcomes included depression and quality of life measures.

Results

73/97 (75.3%) eligible women participated; 41.1% had a previous preterm birth, 31.5% a second trimester loss and 28.8% cervical surgery; 20.6% had a prior mental health condition. 63/73 (86.3%) women completed all questionnaires. The adjusted mean state-anxiety score was 39.0 at baseline, which decreased to 36.5 after the second visit (difference −2.5, 95% CI −5.5 to 0.5, p=0.1) and to 32.6 after the last visit (difference −3.9 from second visit, 95% CI −6.4 to −1.5, p=0.002). Rates of anxiety (state-anxiety score >40) and depression (Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale score >12) were 38.4%, 34.8%, 19.0% and 13.7%, 8.7%, 9.5% respectively, at the same time periods. Perceptions of care were favourable; 88.9% stated the preterm birth clinic made them significantly or somewhat less anxious and 87.3% wanted to be seen again in a future pregnancy.

Conclusions

Women at increased risk of spontaneous preterm birth have high levels of anxiety. Psychological well-being improved during the second trimester; women perceived that preterm birth clinic care reduced pregnancy-related anxiety. These findings support the ongoing use and development of preterm birth clinics.

Keywords: maternal medicine, fetal medicine, depression & mood disorders

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to assess the psychological well-being of women at high risk of spontaneous preterm birth who are cared for in a specialised preterm birth clinic.

Strengths of the study include the prospective study design, and high rates of recruitment and participant retention in an ethnically diverse group of women.

Limitations of the study are the modest sample size, lack of a comparison group and the use of screening tools rather than diagnostic criteria for anxiety and depression.

Although this study demonstrates improved psychological well-being of women at high risk of spontaneous preterm birth, further research is required to more directly quantify the impact of a preterm birth clinic on this.

Introduction

Psychological disorders are common in pregnancy.1 2 Women with high-risk pregnancies are more likely to suffer psychological distress with higher rates of anxiety and depression than the general pregnant population.3–5 Few studies have assessed the psychological well-being of women who are at high risk of spontaneous preterm birth, and in particular, the potential impact of care from a specialised preterm birth clinic. Preterm birth clinics provide a package of care to asymptomatic women identified to be at increased risk based on their obstetric and gynaecological history. This care includes regular visits through the second trimester for ultrasound surveillance of cervical length and provision of treatments to prevent preterm birth such as cervical cerclage and vaginal progesterone therapy when indicated.6–8 Close monitoring and reassurance provided through a preterm birth clinic may reduce pregnancy-related anxiety, however, it is also possible that being labelled ‘high risk’ may increase psychological distress and anxiety.9–11 Further research in this area has been recommended.12

There is increasing recognition of the importance of psychological well-being in pregnancy. Meta-analyses show that antenatal depression is associated with a modestly increased risk of preterm birth and fetal growth restriction, and decreased rates of breastfeeding initiation.13 14 The effect of anxiety is less well evaluated, but is associated with increased pregnancy-related hypertension, increased rates of caesarean section, decreased rates of exclusive breastfeeding and increased anxiety in the offspring.15 Antenatal anxiety and depression are also strong predictors of postnatal depression.16 Strategies for prevention, along with improvements in the recognition and treatment of psychological disorders in pregnancy, are likely to improve outcomes for women and children.17

This study aims to assess rates of anxiety, depression and health-related quality of life in pregnant women at high risk of spontaneous preterm birth who are cared for in a preterm birth clinic. The primary hypothesis is that women will have less anxiety after their second consultation in a preterm birth clinic compared with before their first (baseline), and this improvement will be sustained at the end of the second trimester. Secondary hypotheses are that women will have fewer symptoms of depression, improved quality of life, and less pregnancy-related anxiety over the same period.

Material and methods

This longitudinal cohort study was carried out in a large tertiary maternity hospital in Auckland, New Zealand. All eligible women attending the preterm birth clinic over a 12-month period from August 2018 to August 2019 were invited to participate prior to their first appointment. This preterm birth clinic provides care to pregnant women perceived to be at high risk of spontaneous preterm birth and accepts local and regional referrals. Eligibility criteria for the preterm birth clinic include women with a previous spontaneous preterm birth, previous second trimester loss, history of extensive cervical surgery, or congenital uterine anomaly. Care through the preterm birth clinic includes initial assessment, risk factor modification, serial surveillance of cervical length until 24 weeks, and interventions such as vaginal progesterone and cervical cerclage when indicated (online supplemental table 1). Care in the preterm birth clinic is provided by a specialist obstetric and midwifery team on a weekly basis, and is in addition to routine antenatal care.

bmjopen-2021-056999supp001.pdf (159KB, pdf)

Inclusion criteria for the study were gestational age <24+0 weeks at first visit; live fetus; eligible for preterm birth clinic review due to ≥1 risk factor for spontaneous preterm birth (online supplemental table 1); written consent obtained; and sufficient English to independently complete questionnaires. Participants completed three sets of questionnaires: prior to their first clinic appointment (baseline, set 1), after their second appointment (usually 2–3 weeks later, set 2), and after their last appointment (usually at 23–24 weeks of gestation, Set 3). Three women were seen for only two appointments and returned the Set 3 questionnaires by post 2 weeks after their last visit. Each set of questionnaires contained three validated measures: the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), used under licence from Mind Garden Incorporated18 which contains two subscales to allow differentiation between temporary ‘state-anxiety’ and the relatively stable and long-standing aspects of anxiety proneness in ‘trait-anxiety’19; the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) which is validated for antenatal depression20; and the RAND 36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36) to assess health-related quality of life.21 22 Set 1 and 3 also included a study-specific questionnaire to assess mental health history, social support, pregnancy-related anxiety and perceptions of care. This included free text responses on pregnancy-related anxiety triggers and what helped to relieve it (online supplemental tables 2 and 3). The study-specific questionnaires were developed by the research team and piloted for the first five women and minor changes made based on feedback.

For the purposes of this study, state-anxiety was considered the most relevant assessment for current levels of anxiety. A screen positive result was defined as a score of >40 on the STAI state-anxiety score. Pregnancy-related anxiety was also assessed using a ten-point visual analogue scale and reported separately. In the assessment of depression, a screen positive result was defined as a score of >12 on the EPDS.

Participants were contacted by telephone prior to their first appointment and invited to participate, and participant information and consent forms were provided in advance to interested women. After consenting, participants completed hard copy questionnaires independently using a private room, just prior to their first clinic consultation. The EPDS self-harm question was reviewed at completion and for any women answering ‘yes, quite often’ or ‘sometimes’, further assessment of safety was made and referral to maternal mental health services offered. No other changes were made to clinical care. All other responses were seen only by a single investigator not responsible for decisions about referral for psychological support, until completion of the study. Standard clinic practice is described in online supplemental table 1. At the last visit, the discharging obstetrician used pre-defined criteria developed for the purposes of this study to classify ongoing preterm birth risk. Women were considered low risk if cervical length was >25 mm with fetal fibronectin <50 ng/mL (if performed), and no intervention with vaginal progesterone or cerclage required; intermediate risk if cervical length was 11–25 mm, and/or fetal fibronectin 50–199 ng/mL, and/or there was need for progesterone or cerclage; or high risk if cervical length was <10 mm, and/or fetal fibronectin ≥200 ng/mL (online supplemental table 4).

Demographic details, pregnancy characteristics, medical history and pregnancy outcomes were obtained from electronic medical records. These data, along with questionnaire responses were entered into a password-protected Excel spreadsheet by a single investigator.

The primary outcome was the STAI state-anxiety score. Secondary outcomes were the EPDS score, SF-36 summary quality of life scores, and pregnancy-related anxiety (as continuous measures).

Statistical analyses

A pragmatic sample size was used. We aimed to invite all eligible women over a 1-year period to participate. Using data from medically high-risk women,23 we estimated a sample size of 60 would provide 80% power, with alpha of 0.05, two-sided test and an estimated within subject correlation of 0.75 to detect a decrease in the mean state-anxiety score from 40.0 (SD 12.0) to 36.9.

Descriptive statistics were calculated using SPSS (V.25.0) and R software (V.3.5.3).24 25 Thematic analysis was carried out on free-text responses using Braun and Clarke methodology by a single investigator.26 The mixed model for repeated measures analyses (MMRM) was used to analyse repeatedly measured continuous outcomes and conducted using SAS software (V.9.4).27 These analyses were used to test for time effect adjusting for prior diagnosis of a mental health condition, gestational age at first visit and obstetric history (categorised by no previous pregnancy beyond 12 weeks; loss/preterm birth at 12–28 weeks; loss/preterm birth at 28–37 weeks or term birth only), and subject was included as a random effect. Kenward-Roger method was used to estimate the denominator degrees of freedom for fixed effects. Two-sided p<0.05 determined statistical significance. All CI are given at a two-sided 95% level.

Patient and public involvement

The study-specific questionnaire was piloted among the first five participants, who were asked for feedback on the clarity and importance of the questions. There was no other patient involvement in the study development.

Results

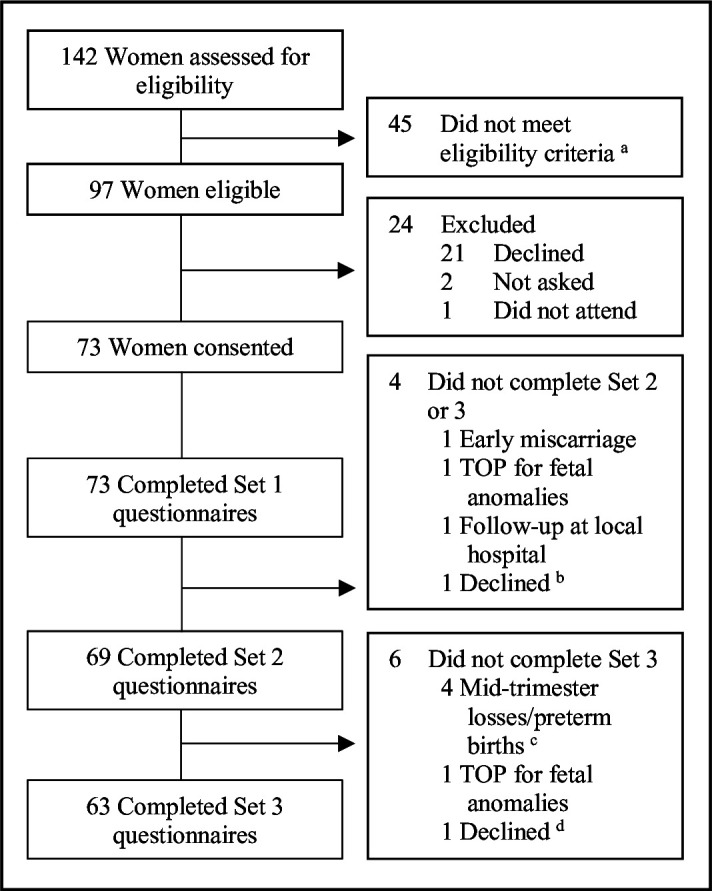

The recruitment rate was 75.3% (73/97), participation is described in figure 1. Demographics, obstetric characteristics and risk factors for preterm birth are detailed in table 1. Some women had been seen in the clinic in a previous pregnancy (17/73, 23.3%) and/or for prepregnancy review (12/73, 16.4%).

Figure 1.

Participant recruitment and study flow diagramTOP, termination of pregnancy. aReasons not eligible: 19 were prepregnancy consultations, 2 had previously participated in study (both with pregnancy losses), 9 had insufficient English (including one who provided consent but was then identified to have insufficient written English when attempted first set of questionnaires and was withdrawn from the study), 3 were >24 weeks at first visit and 12 had a single visit planned only. bDistressed with new diagnosis of severe hypertension and fetal growth restriction, subsequently had fetal demise before last visit. cGestational ages at delivery 16+1, 22+3, 23+4 and 24+4 weeks. dRecent diagnosis of severe depression with acute distress.

Table 1.

Demographic details, obstetric characteristics and risk factors for preterm birth

| Characteristic | No (%) or mean (SD), n=73 |

| Ethnicity | |

| European | 36 (49.3) |

| Māori | 7 (9.6) |

| Pacific | 5 (6.8) |

| Asian | 11 (15.1) |

| Indian | 9 (12.3) |

| Other | 5 (6.8) |

| Age (years) | |

| Mean | 34.0 (5.1) |

| Range | 22–45 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2)* | |

| Mean | 26.3 (6.4) |

| Range | 19–57 |

| Current smoker | 5 (6.8) |

| Has a current partner | 72 (98.6) |

| Previous diagnosis of a mental health condition (non-exclusive)† | |

| Depression | 10 (13.7) |

| Postnatal depression | 4 (5.5) |

| Generalised anxiety disorder | 2 (2.7) |

| Panic disorder | 1 (1.4) |

| Social anxiety disorder | 1 (1.4) |

| Post-traumatic spectrum disorder | 3 (4.1) |

| None | 58 (79.4) |

| Currently taking medication for a mental health condition | 4 (5.5) |

| Currently under the care of a psychiatrist/psychologist | 1 (1.4) |

| Nulliparous | 16 (21.9) |

| Previous stillbirth or neonatal death ≥20+0 weeks | 22 (30.1) |

| Current twin pregnancy | 1 (1.4) |

| Reasons for preterm birth clinic referral (non-exclusive) | |

| Previous spontaneous preterm birth/PPROM (24+0 to 36+0 weeks)‡ | 30 (41.1) |

| Previous second trimester loss (16+0 to 23+6 weeks) | 23 (31.5) |

| Previous extensive cervical surgery§ | 21 (28.8) |

| Congenital uterine anomaly | 1 (1.4) |

| Short cervix in current pregnancy <25 mm | 5 (6.8) |

| ≥2 surgical terminations and/or other uterine instrumentations | 14 (19.2) |

| Other risk factors for spontaneous preterm birth | 4 (5.5) |

| Multiple reasons for referral to the preterm birth clinic | 23 (31.5) |

*Missing data n=2.

†Self-reported.

‡Includes survivors born at 23 weeks of gestation.

§LLETZ with depth of excision ≥10 mm or >1 procedure, or knife cone biopsy.

LLETZ, large loop excision of the transformation zone; PPROM, prelabour premature rupture of membranes.

The mean gestational ages at questionnaire completion were 13+4 weeks (SD 3+3), 16+2 weeks (SD 3+2) and 23+6 weeks (SD 1+2). Anxiety, depression and quality of life scores and proportion of screen positive results (defined as >40 on the STAI state-anxiety scale and >12 on the EPDS) are shown in table 2. MMRM analyses, adjusting for gestation at first visit, prior mental health condition and obstetric history (fixed effects), are described in table 3. The primary outcome of the adjusted mean state-anxiety score was 39.0 at baseline and decreased to 36.5 after the second visit (least square means difference −2.5, 95% CI −5.5 to 0.5, p=0.1), with a further reduction to 32.6 after the last visit (least squares means difference −3.9 from the second visit, 95% CI −6.4 to −1.5, p=0.002). Adjusted secondary outcomes are reported in table 3.

Table 2.

Anxiety, depression and quality of life scores (unadjusted)

| Set 1 (baseline), n=73* | Set 2, n=69* | Set 3, n=63* | ||||

| Mean (SD) or proportion (%) | 95% CI | Mean (SD) or proportion (%) | 95% CI | Mean (SD) or proportion (%) | 95% CI | |

| STAI state-anxiety score | 38.6 (11.9) | 36.8 to 41.3 | 36.2 (11.6) | 33.5 to 38.9 | 32.0 (9.8) | 29.6 to 34.4 |

| STAI state-anxiety positive screen† | 28/73 (38.4) | 27.2 to 49.5 | 24/69 (34.8) | 23.5 to 46.0 | 12/63 (19.0) | 9.4 to 28.7 |

| STAI trait-anxiety score | 37.3 (10.1) | 35.0 to 39.6 | 36.5 (9.6)‡ | 34.2 to 38.8 | 34.9 (10.8) | 32.2 to 37.6 |

| STAI trait-anxiety positive screen† | 28/73 (38.4) | 27.2 to 49.5 | 23/68 (33.8)‡ | 22.6 to 45.1 | 15/63 (23.8) | 13.3 to 34.3 |

| EPDS score | 7.3 (4.6) | 6.2 to 8.4 | 6.0 (4.5) | 4.9 to 7.1 | 5.4 (5.1) | 4.1 to 6.6 |

| EPDS positive screen§ | 10/73 (13.7) | 5.8 to 21.6 | 6/69 (8.7) | 2.0 to 15.3 | 6/63 (9.5) | 2.3 to 16.8 |

| Summary mental health score¶ | 63.8 (15.9), †† | 60.0 to 67.8 | 65.7 (17.0)** | 61.5 to 69.9 | 72.4 (17.9), ¶¶ | 67.8 to 77.0 |

| Summary physical health score¶ | 69.3 (21.5)‡ | 64.3 to 74.3 | 66.0 (24.1)‡‡ | 60.2 to 71.8 | 71.3 (22.7)‡ | 65.6 to 77.0 |

| Pregnancy-related anxiety§§ | 4.9 (2.5) ‡ | 4.3 to 5.5 | – | – | 2.7 (2.5) | 2.1 to 3.3 |

*Set 1 questionnaires were completed prior to the women’s first clinic appointment (baseline); set 2 after their second appointment (usually 2–3 weeks later); set 3 after their last appointment (usually at 23–24 weeks of gestation).

†Positive screen defined as STAI score >40.

‡Missing score for one woman as one incomplete question.

§Positive screen defined as EPDS >12.

¶Using the RAND 36-Item Short Form Survey. Higher scores associated with better quality of life.

**Missing scores for five women as one or more incomplete questions.

††Missing scores for nine women as one or more incomplete questions.

‡‡Missing scores for three women as one or more incomplete questions.

§§Visual Analogue Scale, 0=not at all anxious, 10=extremely anxious.

¶¶Missing scores for four women as one or more incomplete questions.

EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; STAI, State Trait Anxiety Inventory.

Table 3.

Mixed model for repeated measures analyses for anxiety, depression and quality of life scores

| STAI state-anxiety score | EPDS score | Summary physical health score* | Summary mental health score* | |||||||||

| Fixed effect | P value† | P value† | P value† | P value† | ||||||||

| Questionnaire set no | <0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.3 | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| Gestation at first visit‡ | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.2 | ||||||||

| Prior mental health condition‡ | 0.7 | 0.09 | 0.6 | 0.006 | ||||||||

| Obstetric history ‡ ¶ | 0.4 | 0.04 | 0.8 | 0.3 | ||||||||

| Least squares means | Estimate | 95% CI | Estimate | 95% CI | Estimate | 95% CI | Estimate | 95% CI | ||||

| Set 1 | 39.0 | 35.6 to 42.4 | 7.5 | 6.1 to 8.9 | 70.9 | 63.9 to 77.8 | 60.7 | 55.8 to 65.6 | ||||

| Set 2 | 36.5 | 33.0 to 40.0 | 6.3 | 4.9 to 7.7 | 67.2 | 60.1 to 74.4 | 62.5 | 57.5 to 67.4 | ||||

| Set 3 | 32.6 | 29.1 to 36.1 | 5.7 | 4.3 to 7.1 | 71.5 | 64.3 to 78.6 | 69.5 | 64.6 to 74.5 | ||||

| Least squares means difference | Estimate | 95% CI | P value§ | Estimate | 95% CI | P value§ | Estimate | 95% CI | P value§ | Estimate | 95% CI | P value§ |

| Set 2–1 | −2.5 | −5.5 to 0.5 | 0.1 | −1.2 | −2.3 to 0.2 | 0.02 | −3.7 | −10.1 to 2.8 | 0.3 | 1.8 | −3.1 to 6.6 | 0.5 |

| Set 3–1 | −6.4 | −8.8 to 4.0 | <0.0001 | −1.8 | −2.6 to 1.0 | <0.0001 | 0.6 | −4.6 to 5.8 | 0.8 | 8.9 | 4.7 to 13.0 | <0.0001 |

| Set 3–2 | −3.9 | −6.4 to 1.5 | 0.002 | −0.6 | −1.4 to 0.2 | 0.2 | 4.2 | −1.1–9.6 | 0.1 | 7.1 | −3.0 to −11.2 | 0.001 |

*RAND 36-Item Short Form Survey. Higher scores associated with better quality of life.

†Pr >F. Type 3 tests of fixed effects.

‡Analysis adjusted for these factors.

§Pr > |t|.

¶Categorised by no previous pregnancy beyond 12 weeks; loss/preterm birth at 12–28 weeks; loss/preterm birth at 28–37 weeks; or term birth only.

STAI, State Trait Anxiety Inventory; EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale.;

One woman was referred to maternal mental health services following review of the EPDS self-harm question. Preterm birth clinic clinicians referred six women to the women’s health social work for psychological support and two to maternal mental health services as part of routine practice. None of the women who completed the set 3 questionnaires reported having a new diagnosis of a mental health condition made by a health practitioner during the study period. One woman declined to complete the last set of questionnaires after a diagnosis of severe depression.

Women had mixed feelings about referral to the clinic prior to review, but following their last visit 56/63 (88.9%) reported care in the preterm birth clinic made them significantly or somewhat less anxious. The majority (55/63, 87.3%) would want to be cared for in a preterm birth clinic again in another pregnancy. The seven women who did not, had already had a term birth since their prior early birth, or were referred for cervical surgery or multiple uterine instrumentations only (and only one required an intervention greater than surveillance in their current pregnancy) (online supplemental table 5).

The predominant themes causing pregnancy-related anxiety at baseline were preterm birth, pregnancy loss, and concern for the baby’s health. Many women were anxious about extremely early birth—‘being born too early to do anything about it,’ and were worried about reaching milestones—‘getting to 24 weeks to be deemed to have a ‘viable’ pregnancy.’ Women were worried about history repeating itself —‘I am scared that it might happen again,’ and how they would cope if it did —‘my ability to manage emotions associated with neonatal intensive care unit if this baby is early.’ Fewer women were anxious about the risks of chromosomal or fetal anomalies.

When asked at clinic discharge what they found most helpful to relieve pregnancy-related anxiety, the main theme was medical support, including close monitoring, the preterm birth clinic, regular ultrasound scans and support and communication from doctors—‘the fortnightly visits have really helped me! Lots of reassurance,’ ‘follow-up from the preterm birth clinic,’ ‘the weekly check-ups and reassurance from the doctors and how quickly they acted when there was an issue,’ and ‘the support of specialists who are willing to listen.’ Other themes included support from family and friends, distraction, relaxation techniques and prayer.

The mean number of clinic visits was 5.4 (SD 2.1), range 1–11. Clinic interventions and pregnancy outcomes are reported in table 4. Elective cervical cerclage is reserved for the highest risk women, and was performed in 17/72 cases (23.6%, excludes one women with local follow-up after the first visit as no further data collected), usually at 12–14 weeks gestation. The remaining women had ultrasound surveillance of cervical length as their primary management. The overall rate of birth <37 weeks was 17/72 (23.6%), including two spontaneous second trimester losses. One extremely early preterm birth followed prelabour fetal demise, all other preterm births occurred following spontaneous labour or preterm prelabour rupture of membranes. Of pregnancies that reached ≥20+0 weeks 67/69 (97.1%) babies were alive at hospital discharge.

Table 4.

Preterm birth clinic interventions and pregnancy outcomes*

| Characteristics | Proportion (%) or mean (SD) |

| Shortest transvaginal cervical length measurement | |

| Mean (SD) (in mm) | 27.0 (9.1) |

| Range (in mm) | 0–39 |

| No <25 mm (threshold for intervention) | 21/72 (29.2) |

| Treatments given to reduce the risk of preterm birth | |

| Cervical cerclage only | 16/72 (22.2) |

| Vaginal progesterone only | 4/72 (5.6) |

| Both cervical cerclage and vaginal progesterone | 10/72 (13.9) |

| No treatment | 40/72 (55.6) |

| Antenatal hospital admission from clinic due to preterm birth risk | 2/72 (2.8) |

| Risk of preterm birth for those who had an exit visit† | |

| Low | 45/66 (68.2) |

| Intermediate | 18/66 (27.3) |

| High | 3/66 (4.5) |

| Pregnancy outcome | |

| Termination of pregnancy for fetal anomalies | 2/72 (2.8) |

| First trimester miscarriage (<13+0 weeks) | 1/72 (1.4) |

| Second trimester loss (13+1 to 22+6 weeks) | 2/72 (2.8) |

| Extremely early preterm birth (23+0 to 27+6 weeks)‡ | 3/72 (4.2) |

| Very early preterm birth (28+0 to 31+6 weeks) | 1/72 (1.4) |

| Moderate to late preterm birth (32+0 to 36+6 weeks) | 11/72 (15.3) |

| Term birth (≥37+0 weeks) | 52/72 (72.2) |

| Mode of birth for pregnancies that reached ≥20+0 weeks§ | |

| Normal vaginal birth | 44/68 (64.7) |

| Instrumental birth | 7/68 (10.3) |

| Caesarean section | 17/68 (25.0) |

| Neonatal outcome for pregnancies that reached ≥20+0 weeks§¶ | |

| Alive at hospital discharge | 67/69 (97.1) |

| Early neonatal death | 1/69 (1.4) |

| Stillbirth | 1/69 (1.4) |

*Excluding one with all follow-up at local hospital after first visit as no further data collected.

†Risk assessment defined in online supplemental table 4. Quantitative fetal fibronectin was included in 29/66 (44%) cases. Excludes six women who did not have an exit appointment. Includes three women who did not complete Set 3 questionnaires—for two the exit visit was their second visit, both were high risk and delivered prior to planned completion of the set 3 questionnaires by post; and one who declined.

‡Includes one prelabour fetal demise.

§Excluding one termination of pregnancy >20 weeks.

¶Includes one set of twins.

Discussion

This is the first study to assess the psychological well-being of women receiving care in a specialised preterm birth clinic. It identifies high rates of psychological distress, with 38.4% and 13.7% of women having significant symptoms of anxiety and depression, respectively, at the beginning of the second trimester. While the change in mean state-anxiety scores after two clinic visits did not reach statistical significance, improvement may still be clinically important. Adjusted mean state-anxiety scores were significantly improved by clinic discharge, with rates of anxiety half that of baseline. Although depression was less common than anxiety, the adjusted mean EPDS score improved by the second clinic visit and this was sustained to the end of the second trimester. Quality of life improved with regard to mental health, but not physical health. Pregnancy-related anxiety scores also improved and women perceived care in the preterm birth clinic to be a significant factor in relieving anxiety.

A number of studies have reported rates of anxiety and depression in pregnancy, with a wide range of estimates.1 2 In systematic review, the overall prevalence of a clinical diagnosis of an anxiety disorder in pregnancy was 15.2%, with rates of self-reported anxiety of 18.2%, 19.1% and 24.6% in the first, second and third trimesters respectively.2 Women with high-risk pregnancies have higher rates of anxiety than low risk women; 45.0% vs 16.7% in one study.23 Rates of depression were 7.4%, 12.8% and 12.0% in the general pregnant population in the first, second and third trimesters,1 and ranged from 11% to 28% in studies on high-risk pregnancies.3 4 23 28 29 The higher rates of anxiety seen in our study are consistent with published literature for high-risk pregnancies with rates of depression in the lower range of those previously reported.

Although we do not have data for the whole pregnancy, it seems that gestational changes in rates of anxiety in women at high risk of spontaneous preterm birth may not follow the same trends as in the general pregnant population in which rates rise throughout pregnancy.2 In our study, anxiety was highest at the beginning of the second trimester and then decreased to levels similar to those seen in general pregnant populations by the end of the second trimester. This may be due to reduced anxiety over second trimester loss once this gestational time period is complete (31.5% of our cohort had experienced a second trimester loss previously). However, advancing gestation is unlikely to be the sole factor in anxiety levels returning to those of the general pregnant population, as the risk of early preterm birth was still ongoing at the time of last clinic visit. This, along with women’s perception of care, suggests that preterm birth clinic care may have had a role in improving psychological well-being. The provision of an overall ongoing risk assessment at the final clinic visit is likely to be beneficial; the majority of women were considered to have a relatively low ongoing risk of preterm birth and encouraged to return to a low risk model of maternity care.

While there is some evidence that simply labelling a pregnancy ‘high risk’ may increase anxiety and fear, other studies identified that women embrace this label in a positive way.10 11 A qualitative study has assessed women’s perceptions of care in a preterm birth clinic in the UK, with all women viewing their high-risk status positively.11 These women reported that regular reassurance from the clinic was a helpful coping strategy and that other health professionals were not always sensitive to their worries about having another preterm birth.11 Our results are consistent with these findings.

Preterm birth clinics offer individualised, coordinated and evidence-based care with the aim of reducing spontaneous preterm birth and improving perinatal outcome. Any potential to reduce psychological distress is an additional benefit. Further research should aim to include a comparison group to more directly quantify the effect of preterm birth clinics in improving psychological well-being. A larger sample size would also be required to direct practice change if considering the psychological, as well as clinical, benefit of preterm birth clinics. However, the new knowledge from our study should reassure clinicians and policy makers that preterm birth clinics do not seem to cause psychological harm.

Symptoms of anxiety and depression were under-recognised by clinicians in this study, with low referral rates for psychological support or maternal mental health review based on usual indications. Early recognition of anxiety and depression with provision of support or referral for other interventions may reduce maternal morbidity and improve pregnancy outcomes, and is likely to reduce the risk of postnatal depression.30 Our findings suggest there are currently missed opportunities for care and preterm birth clinics should ensure they have referral pathways and access to psychological assessment and support, or should incorporate this into part of standard care within the clinic.

The main limitations of our study are the lack of a comparison group and modest sample size. The most appropriate comparison is with women of similar preterm birth risk who do not receive care in a preterm birth clinic; however, withholding clinic care is not possible when a clinic is well established within an area and available to all. Use of the general population or a medically high-risk group as a comparator is not appropriate as background anxiety levels for these women may increase over gestation due to increasing risk of other pregnancy complications, whereas the risk of preterm birth decreases with advancing gestation. Sample size was directed by the duration of the study and the number of women referred to the preterm birth clinic over the 12-month period. We are aware that not all women eligible for the clinic (and therefore for the study) were referred during this time period, and the women seen may have a higher risk profile than those who were eligible but not referred.

A further limitation is the use of screening tests rather than diagnostic criteria for anxiety and depression. While diagnostic interviews are the gold standard, they are time consuming, require special training and are expensive.31 Screening tests are reliable and have been validated for use in pregnancy.28 32–38 The STAI with a cut-off >40 has a sensitivity of 81% and specificity of 80% for diagnosis of an anxiety disorder in pregnancy when compared with DSM-IV (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) criteria.39 The EPDS is also accurate, with a cut-off of >12 used in pregnancy, giving a sensitivity of 83% and specificity of 90% for detection of major depression.40 Participant drop-out may have influenced the study outcome as the majority were due to pregnancy loss or extremely early preterm birth, and these women may have had the highest risk pregnancies and hence highest levels of psychological distress. However, unadjusted analysis of only the 63 women who completed all assessments showed similar results to those presented here.

Strengths of this study include longitudinal assessment of a high-risk cohort with a high recruitment rate in an ethnically diverse group of women. Although undertaken at a single site, referrals are accepted from the wider region, improving generalisability of results. There were multiple clinicians working in the clinic over the study period (two lead obstetricians, three senior obstetric trainees and three specialist midwives), so an individual clinician is unlikely to have had significant influence over outcomes. Variation in practice between preterm birth clinics has been recognised as an issue,41 42 however, the general principles of care identified by women as factors that reduced anxiety, that is, close surveillance and regular ultrasound scans, are similar across clinics globally.

Conclusion

Women at increased risk of spontaneous preterm birth are more likely to have higher levels of anxiety in early pregnancy. Improvements in psychological well-being were seen during the time these women were cared for in a specialised preterm birth clinic through the second trimester. Women’s perceptions of a preterm birth clinic were favourable and they attributed the care received as being a significant factor in reducing pregnancy-related anxiety. Findings of this study support the ongoing use and development of these specialised clinics.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the women who participated in this study and the midwifery and clerical staff at National Women’s Health who provided administrative support.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors fulfil the authorship requirements described by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. LD was the lead investigator and was responsible for writing the first draft of the study protocol, obtaining ethical approval, the majority of data collection and analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. KMG was the supervising investigator, she conceived the idea for the study and provided substantial contribution to the study protocol, ethical approvals, analysis and interpretation of results. AL made substantial contributions to the statistical analyses and interpretation of results. JJSW made substantial contributions to the study design and interpretation of results. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript submitted for publication. LD accepts full responsibility for the work and conduct of the study, had access to the data, and controlled the decision to publish.

Funding: This work was supported by the Auckland Medical Research Foundation Ruth Spencer Fellowship, Mercia Barnes Trust, and Hugo Charitable Trust (grant number 3715802).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

No data are available. Data are available on reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval was granted by the New Zealand Health and Disability Ethics Committees (18/NTA/103) and institutional approval by the Auckland District Health Board Research Review Committee (A+8127) in July 2018.

References

- 1.Bennett HA, Einarson A, Taddio A, et al. Prevalence of depression during pregnancy: systematic review. Obstet Gynecol 2004;103:698–709. 10.1097/01.AOG.0000116689.75396.5f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dennis C-L, Falah-Hassani K, Shiri R. Prevalence of antenatal and postnatal anxiety: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 2017;210:315–23. 10.1192/bjp.bp.116.187179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dagklis T, Tsakiridis I, Chouliara F, et al. Antenatal depression among women hospitalized due to threatened preterm labor in a high-risk pregnancy unit in Greece. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2018;31:919–25. 10.1080/14767058.2017.1301926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thiagayson P, Krishnaswamy G, Lim ML, et al. Depression and anxiety in Singaporean high-risk pregnancies - prevalence and screening. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2013;35:112–6. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fairbrother N, Young AH, Zhang A, et al. The prevalence and incidence of perinatal anxiety disorders among women experiencing a medically complicated pregnancy. Arch Womens Ment Health 2017;20:311–9. 10.1007/s00737-016-0704-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vernet G, Watson H, Ridout A, et al. The role of PTB clinics: a review of the screening methods, interventions and evidence for preterm birth surveillance clinics for high-risk asymptomatic women. Women Health Bull 2017;4:2–9. 10.5812/whb.12667 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . Preterm labour and birth, 2015. Available: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng25/resources/preterm-labour-and-birth-pdf-1837333576645 [PubMed]

- 8.Jin W, Hughes K, Sim S, et al. The contemporary value of dedicated preterm birth clinics for high-risk singleton pregnancies: 15-year outcomes from a leading maternal centre. J Perinat Med 2021;49:1048–57. 10.1515/jpm-2021-0020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stahl K, Hundley V. Risk and risk assessment in pregnancy - do we scare because we care? Midwifery 2003;19:298–309. 10.1016/S0266-6138(03)00041-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simmons HA, Goldberg LS. 'High-risk' pregnancy after perinatal loss: understanding the label. Midwifery 2011;27:452–7. 10.1016/j.midw.2010.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O'Brien ET, Quenby S, Lavender T. Women's views of high risk pregnancy under threat of preterm birth. Sex Reprod Healthc 2010;1:79–84. 10.1016/j.srhc.2010.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malouf R, Redshaw M. Specialist antenatal clinics for women at high risk of preterm birth: a systematic review of qualitative and quantitative research. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017;17:51. 10.1186/s12884-017-1232-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grigoriadis S, VonderPorten EH, Mamisashvili L, et al. The impact of maternal depression during pregnancy on perinatal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry 2013;74:e321–41. 10.4088/JCP.12r07968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grote NK, Bridge JA, Gavin AR, et al. A meta-analysis of depression during pregnancy and the risk of preterm birth, low birth weight, and intrauterine growth restriction. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2010;67:1012–24. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Field T. Prenatal anxiety effects: a review. Infant Behav Dev 2017;49:120–8. 10.1016/j.infbeh.2017.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robertson E, Grace S, Wallington T, et al. Antenatal risk factors for postpartum depression: a synthesis of recent literature. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2004;26:289–95. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2004.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giardinelli L, Innocenti A, Benni L, et al. Depression and anxiety in perinatal period: prevalence and risk factors in an Italian sample. Arch Womens Ment Health 2012;15:21–30. 10.1007/s00737-011-0249-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mind Garden . State-Trait anxiety inventory for adults, 2018. Available: https://www.mindgarden.com/145-state-trait-anxiety-inventory-for-adults

- 19.Spielberger C, Gorsuch R, Lushene R. Stai: manual for the State-Trait anxiety inventory (STAI. California: Consulting Psychologists Press, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. development of the 10-item Edinburgh postnatal depression scale. Br J Psychiatry 1987;150:782–6. 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The mos 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992;30:473–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.RAND Corporation . 36-Item short form survey (SF-36), 2018. Available: https://www.rand.org/health/surveys_tools/mos/36-item-short-form.html

- 23.King NMA, Chambers J, O'Donnell K, et al. Anxiety, depression and saliva cortisol in women with a medical disorder during pregnancy. Arch Womens Ment Health 2010;13:339–45. 10.1007/s00737-009-0139-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.IBM Corp . IBM SPSS statistics for windows 25.0. New York: IBM Corp, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 25.R Core Team . R: a language and environment for statistical computing. 3.5.3 edn. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.SAS Institute . SAS software. 9.4 edn. Cary, NC: SAS Institute, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adouard F, Glangeaud-Freudenthal NMC, Golse B. Validation of the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale (EPDS) in a sample of women with high-risk pregnancies in France. Arch Womens Ment Health 2005;8:89–95. 10.1007/s00737-005-0077-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brandon AR, Trivedi MH, Hynan LS, et al. Prenatal depression in women hospitalized for obstetric risk. J Clin Psychiatry 2008;69:635–43. 10.4088/JCP.v69n0417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Austin M-P. Antenatal screening and early intervention for "perinatal" distress, depression and anxiety: where to from here? Arch Womens Ment Health 2004;7:1–6. 10.1007/s00737-003-0034-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Evans K, Spiby H, Morrell CJ. A psychometric systematic review of self-report instruments to identify anxiety in pregnancy. J Adv Nurs 2015;71:1986–2001. 10.1111/jan.12649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gunning MD, Denison FC, Stockley CJ, et al. Assessing maternal anxiety in pregnancy with the State‐Trait anxiety inventory (STAI): issues of validity, location and participation. J Reprod Infant Psychol 2010;28:266–73. 10.1080/02646830903487300 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grant N, Raouf S. A prospective population-based study to investigate the effectiveness of interventions to prevent preterm birth. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol Conf 2016;123:96. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murray D, Cox JL. Screening for depression during pregnancy with the Edinburgh depression scale (EDDS). J Reprod Infant Psychol 1990;8:99–107. 10.1080/02646839008403615 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bunevicius A, Kusminskas L, Pop VJ, et al. Screening for antenatal depression with the Edinburgh depression scale. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol 2009;30:238–43. 10.3109/01674820903230708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gibson J, McKenzie-McHarg K, Shakespeare J, et al. A systematic review of studies validating the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale in antepartum and postpartum women. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2009;119:350–64. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01363.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Adewuya AO, Ola BA, Dada AO, et al. Validation of the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale as a screening tool for depression in late pregnancy among Nigerian women. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol 2006;27:267–72. 10.1080/01674820600915478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Felice E, Saliba J, Grech V, et al. Validation of the Maltese version of the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale. Arch Womens Ment Health 2006;9:75–80. 10.1007/s00737-005-0099-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grant K-A, McMahon C, Austin M-P. Maternal anxiety during the transition to parenthood: a prospective study. J Affect Disord 2008;108:101–11. 10.1016/j.jad.2007.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence . Antenatal and postnatal mental health: clinical management and service guidance, 2014. Available: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg192 [PubMed]

- 41.Care A, Ingleby L, Alfirevic Z, et al. The influence of the introduction of national guidelines on preterm birth prevention practice: UK experience. BJOG 2019;126:763–9. 10.1111/1471-0528.15549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dawes L, Groom K, Jordan V, et al. The use of specialised preterm birth clinics for women at high risk of spontaneous preterm birth: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020;20:58. 10.1186/s12884-020-2731-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-056999supp001.pdf (159KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

No data are available. Data are available on reasonable request.