Abstract

As women in many countries still fail to give birth in facilities due to financial barriers, many see the abolition of user fees as a key step on the path towards universal coverage. We exploited the staggered removal of user charges in Zambia from 2006 to estimate the effect of user fee removal up to five years after the policy change. We used data from the birth histories of two nationally representative Demographic and Health Surveys to implement a difference-in-differences analysis and identify the causal impact of removing user charges on institutional and assisted deliveries, caesarean sections and neonatal deaths. We also explored heterogeneous effects of the policy. Removing fees had little effect in the short term but large positive effects appeared about two years after the policy change. Institutional deliveries in treated areas increased by 10 and 15 percentage points in peri-urban and rural districts respectively (corresponding to a 25 and 35 percent change), driven entirely by a reduction in home births. However, there was no evidence that the reform changed the behaviours of women with lower education, the proportion of caesarean sections or reduced neonatal mortality. Institutional deliveries increased where care quality was high, but not where it was low. While abolishing user charges may reduce financial hardship from healthcare payments, it does not necessarily improve equitable access to care or health outcomes. Shifting away from user fees is a necessary but insufficient step towards universal health coverage, and concurrent reforms are needed to target vulnerable populations and improve quality of care.

Keywords: User fees, Care-seeking, Maternal care, Neonatal mortality, Zambia

Highlights

-

•

Removing user charges increased healthcare use of pregnant women 2 years after the policy change.

-

•

The proportion of women delivering in facilities increased by 25–35% where care was free.

-

•

Women with lower educations did not benefit from the reform.

-

•

We find no change in C-section rates or neonatal mortality.

1. Introduction

In 2017, an estimated 300,000 women died during or following pregnancy and child birth, while 2.5 million children died in the first month of life in 2018, mostly due to issues arising at birth or immediately after (WHO, 2020). The vast majority of these deaths could be avoided with better access to cost-effective interventions and skilled care (Horton & Levin, 2016), but many women still fail to deliver in facilities. Yet modern healthcare technologies can help to avoid many cases of neonatal deaths caused by pregnancy complications (e.g. haemorrhage, hypertensive disorder, obstructed labour, and pre-existing conditions) (Bates, Chapotera, McKew, & Van DenBroek, 2008). Evidence indicates that giving birth assisted by skilled staff (doctors, midwives) can not only effectively reduce the risk of maternal death (Stephenson, 2006, Say et al., 2014), but clean and skilled care at delivery (including newborn resuscitation, umbilical cord care and management of infections in newborns) does also reduce neonatal mortality (Khan, Zahidie, & Rabbani, 2013). Although low use of modern healthcare services is caused by a range of factors, such as limited accessibility, poor quality or cultural barriers (Gage, 2007), lack of money remains one of the most significant barriers to accessing care, especially when health facilities charge for providing care at the point of delivery, which still occur in many low- and middle-income countries (Saksena, Xu et al., 2010). As a result, many see the abolition of user fees as a key step on the path towards universal coverage – defined as ensuring timely access to quality healthcare without financial hardship (WHO,2010).

Assuming that the demand for health is price-elastic, user fees removal should lead to an increase in health care utilisation. Randomised trials in Mali and Ghana have confirmed benefits of free care on health service use, and even some improvement in health outcomes (Ansah, Narh-Bana et al., 2009, Powell-Jackson, Hanson, Whitty, & Ansah, 2014; Sautmann, Brown, & Dean, 2020). Yet the narrow scope of these trials, either focused on specific products or a few facilities, limits the extent to which one can generalise lessons to system-wide health financing reforms. In practice, the positive effects of free care can be thwarted by issues that often plague complex health system reforms. First, if the abolition of user fees is imperfect (i.e. fees are still charged), individuals have no reason to change their behaviours. Second, if removing fees fuels a deterioration of quality of care, through drug stock-outs or increased absenteeism of demotivated staff, individuals may be discouraged to use health services. If they still decide to use services, poor quality of care may limit the extent to which increased use translates into improved health outcomes.

Despite the high policy relevance of this reform, and the heated debate on user fees more generally, there has been a relative dearth of rigorous empirical evidence on the impact of user charges. Some studies conducted during the 1980s have shown that the demand for health is influenced more by factors such as quality of care than medical prices. Heller (1982) and Akin, Griffin et al. (1986) studies have been particularly influential in guiding the introduction of user-fee policy and to the adoption of the Bamako Initiative in 1987 by African health ministers. However, the effects of user fees introduction were mitigated in Africa; and in some countries user fee policy was a failure. Nolan and Turbat (1995) concluded that failures occurred for two reasons. Firstly, user fees had negative effects on utilisation and equity in health care access. Secondly, revenue-raising was well below expectations. The reasons given by Vogel (1991) for low revenue-raising were the pricing structure of health services, administrative problems and collection costs. Other reasons found in the literature are described in Sepehri and Chernomas (2001) and include revenue seasonality, lack of credit system, weakness of institutions and legal framework and limited community participation. This observation led several African countries to remove user fees. In 1994, South Africa removed user fees for children and pregnant and lactating women. Uganda abolished user fees in 2001, Madagascar in 2003, Kenya reduced user fees in 2004. Burundi abolished user fees for maternal and child services in 2006 and other countries only removed fees for deliveries (Senegal and Kenya in 2007, Ghana in 2003, Sierra Leone in 2010).

While several studies have sought to shed a light on the effects of abolishing user fees at scale, few have considered the long-term effects on maternal care-seeking or health outcomes. Observational studies have often failed to identify the causal effects of abolishing user fees, or have been limited by the use of data from facility registers – that can be unreliable and restrict what researchers can study (Lagarde & Palmer, 2008, Dzakpasu et al., 2014). Studies that have used more robust data and statistical approaches have pointed to mixed effects of removing fees on care-seeking for acute illnesses (Hangoma, Robberstad et al., 2018, Lepine, Lagarde, & LeNestour, 2018). Recent studies have tried to shed a light on the benefits of removing fees on maternal care seeking, by comparing areas (or countries) that removed fees to others that did not (McKinnon, Harper, Kaufman, & Bergevin, 2015; Chama-Chiliba & Koch, 2016, Leone, Cetorelli, Neal, & Matthews, 2016). The evidence of effects is mixed, and a previous analysis of the reform in Zambia looking at the effect of the policy 1-year post reform showed no change in facility-based deliveries (Chama-Chiliba & Koch, 2016). With the exception of Burkina Faso, where Zombré, De Allegri et al. (2019) analysed the effect at four years, there is hardly any evidence on the effects of free care once the policy has matured, even though beneficial effects may take time to appear due to teething problems to implement the policy effectively in the short-term or slow behavioural change (Carasso, Lagarde et al., 2012). As a result, the null effects observed in studies evaluating the short-term effects of policy change can either be explained by a true lack of effectiveness of user fee removal or the challenges associated with the introduction of the policy.

In this study, we aimed to examine whether removing user charges increased the rate of institutional deliveries and improved birth outcomes in the long-run. Using the staggered implementation of the policy change in 2006 and 2007, and data from two nationally representative surveys, we implemented a difference-in-differences strategy to evaluate the impact of removing fees up to five years after the policy reform on the place and type of delivery, as well as neonatal mortality. We explore heterogenous effect depending on wealth, the level of mother education, quality of care in the health facility in the local area and distance to health facility. Our results indicate that the policy led to an increase in the likelihood of delivering in an institutional health facility and of benefitting from assisted delivery at birth. However, we provide evidence that this effect only exists in the medium term and not immediately after the policy introduction. In addition, we show that the effect is stronger for the poorest, educated mothers and in areas where quality of care is good. We do not find however any impact of the policy on health outcomes.

2. Study setting

When Zambia initially introduced user fees in 1991, its objectives were similar to many other sub-Saharan African countries: raising additional income to improve the quality of services, and improving staff motivation and accountability through community participation and salary top-ups (Government of the Republic of Zambia, 1991). In theory, exemptions were in place for certain groups of the population (e.g. children under 5 year old, indigents) or services (antenatal services) (Chama-Chiliba & Koch, 2016). In practice, fee exemptions were poorly enforced, leading to inequitable access to health services (Cheelo, Chama et al., 2010). In light of such negative aspects, user fees were removed from April 2006 in the 54 rural districts of the country. The policy change applied to publicly-funded facilities, which included both government-run facilities as well as mission facilities, largely subsidized by the government. Fees remained in place in the other 18 districts, until the free care policy was extended to the peri-urban parts of these districts in June 2007, and then to the entire country in 2012. The early implementation of the policy was marked by several problems. Confusion about the remits of the policy (Carasso, Palmer et al., 2010), erratic compensation of facilities for the loss of revenues from user fees (Government of the Republic of Zambia, 2006), and a reduction in funding to district primary health care in 2006–2007 (Government of the Republic of Zambia, 2007) meant that user fees were not effectively abolished for everyone in rural districts in the short term (Lepine, Lagarde et al., 2018), justifying the need for evaluations conducted once these initial health system challenges had subsided.

Around the time of the policy change, Zambia was one of the poorest countries in the world, with 64% of the country's population living with less than US$1 a day (Central Statistical Office, 2008). Reflecting its poor access to basic social services and low life expectancy at birth, Zambia's 2006 Human Development Index was ranked 165th out of 177 (UNDP, 2006). The health system was grappling with a high burden of communicable diseases, in particular TB, HIV-AIDS and Malaria. Despite low quality of services fuelled by shortages of drugs and staff, government-run facilities would provide access to about 80% of the population, the rest using faith-based ‘mission’ facilities under the Christian Health Association of Zambia (CHAZ) while a wealthy minority accessed care in use private-for-profit services (Central Statistical Office, 2008). Most patients would access services first through health centres, the lowest level facilities providing primary care services to up to 5,000 households in rural areas and 20,000 in urban ones. When necessary, patients would be referred to hospitals (district or regional).

3. Methods

3.1. Data

We used information contained in the 2007 and the 2013–2014 Zambia Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) for all the births that women had in the five years before the interview. These 5-year birth histories allowed us to construct a dataset containing detailed information on births over a ten-year period spanning over the two policy changes (see the timeline of policy reforms and data used in Figure B1 in Online appendix).

Given the staggered rollout of the policy, we defined three groups in our datasets: (1) individuals living in rural districts where care was free from April 1st, 2006; (2) peri-urban areas in urban districts where fees are removed on June 1st, 2007 and (3) urban areas of urban districts where fees remained in place until January 2012. For the purpose of our analysis we excluded any birth that occurred after January 2012, so that urban areas remain a control group where user charges apply throughout the analysis period.

For each birth, we considered the effect of the policy on four outcomes.

In this paper we extend the work of Chama-Chiliba and Koch (2016) and look at the effect of user fee removal for another five years post reform. Firstly, we considered the place of delivery, and constructed a binary indicator equal to 1 if the woman gave birth in a public or mission healthcare facility where the policy change occurred, and 0 otherwise. Secondly, we considered if the woman was assisted by a skilled birth attendant (doctor, nurse or midwife) during a delivery. This is relevant because maternal and neonatal health outcomes are likely to be better in the presence of a qualified staff. In addition, if the policy change fuelled staff shortages, the proportion of assisted deliveries could have fallen.

Thirdly, we considered whether the delivery was done by caesarean section for two reasons. On the one hand, it is generally recognised that low rates of c-sections, such as the one observed in Zambia before the policy change, are insufficient to cover all the life-threatening events that can occur at birth (Belizán, Minckas et al., 2018). Any increase in the C-section rate resulting from the policy change could therefore be interpreted as an increase in access to life-saving procedures for mothers or babies. On the other hand, one could worry about the capacity of the health system to absorb a sharp increase in the volume of institutional deliveries. Without an adequate response on the supply-side, notably through the provision of adequate medical supplies and staff, one could see a reduction in the proportion of c-sections undertaken.

Finally, we considered neonatal mortality, specifically whether the child dies on the day of the delivery or within the first 28 days. Both are strongly linked to the conditions in which women deliver and can be seen as potential indicators of the effectiveness of care received.

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics for the analytical sample of mothers and births, spanning the period 2002–2011. A few salient facts should be noted between the two sets of ‘treated’ areas where fees were removed (rural districts and peri-urban areas) and the control (urban) areas. In treated areas, women were from less wealthy households, had more children and were more likely to have a lower education level. There were also fewer institutional deliveries in these treated areas compared to urban areas, although the overwhelming majority of these deliveries were assisted by a qualified staff. Only a small proportions of births were done by caesarean sections (from 3% in rural and peri-urban areas to 7% in urban areas), and less than 3% of babies born died within the first 28 days.

Table 1.

Sample description.

| Rural districts (n = 9507) | Peri-urban areas (n = 1642) | Urban areas (n = 3502) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mothers | |||

| Age (years) | 29.52 (7.17) | 29.03 (7.12) | 28.53 (6.63) |

| Wealth index | −0.21 (0.79) | −0.25 (0.74) | 0.83 (1.30) |

| Number of children | 4.30 (2.52) | 4.26 (2.57) | 3.37 (2.20) |

| Has no education or incomplete primary | 4269 (59%) | 711 (60%) | 810 (29%) |

| Births | |||

| Institutional deliveries | 4974 (53%) | 742 (45%) | 2839 (81%) |

| Home births | 4430 (47%) | 887 (54%) | 639 (18%) |

| Assisted deliveries | 4649 (49%) | 677 (41%) | 2795 (80%) |

| Caesarean sections | 252 (3%) | 50 (3%) | 246 (7%) |

| Neonatal deaths | 260 (3%) | 38 (2%) | 103 (3%) |

Data are n (%) or mean (SD).

3.2. Statistical analysis

We use a Difference-in-difference (DiD) approach to identify the intention-to-treat (ITT) effect of the policy. For a given birth event occurring at time t for individual i living in district d, we estimated a specification of the form:

where the variable is coded 1 if the child was delivered after user fees were removed and 0 otherwise and is a dummy variable coded 1 if the woman currently lives in a treated area, and 0 if she lives in a control area. We also include district () and year () fixed effects, allowing us to capture respectively, any time-invariant district characteristics and any changes that would have occurred over the study period (e.g. increase in income). The ITT effect of user fees removal on outcome is given by on the interaction term. Although all outcomes are binary, we estimated linear regressions for ease of interpretation so that can be interpreted as the (percentage point) increase in the outcome in the treated group, compared to its pre-reform level. We also present results from logistic regressions in the online Appendix. We undertook two separate analyses. First, to identify the effect of the policy of the first phase of the policy roll out occurring in April 2006, we restricted the sample to rural districts (treated areas) and urban areas of urban districts (control areas). This analysis estimated the effect of the policy in rural districts. Second, we identified the effect of the policy in peri-urban areas, and restricted the sample to peri-urban (treated) and urban (control) areas of urban districts, with the policy change occurring from June 2007.

We used the location of the DHS sampling cluster in which a woman lived at the time of the interview to infer which policy has applied to her during her entire birth history. As DHS data include the name of the district in which the household lives, determining which women lived in one of the 54 districts in which the 2006 policy change occurred was straightforward. To determine whether a woman lived in peri-urban areas of urban districts, we used the GIS coordinates of her sampling cluster and calculated the distance to the administrative centre of the district, the criteria used by health authorities to identify peri-urban areas – see Appendix C in the Online appendix for further details. Note that the assignment to treatment status makes two assumptions. First, we assumed that a woman has always resided in the same area in the last five years. Second, we assumed that the random displacement of the DHS sampling clusters does not interfere with assignment with the treatment status (Perez-Heydrich, Warren, Burgert, & Emch, 2013). We discuss these assumptions later.

A key identifying assumption for a valid DiD estimation is that outcomes in the treatment and control group were following a similar path before the policy change. We provide graphical evidence to check this assumption in Figures B2–B4 in the online appendix. The data support the assumption for most outcomes, except neonatal mortality, where trends are only parallel from 2003. Hence, we excluded data from 2002 for this outcome.

Beyond the analysis of the main effects of the policy change, we performed three sub-group analyses. To avoid performing an under-powered analysis, we do not perform this analysis on the two outcomes linked to more rare events (caesarean sections and neonatal deaths). First, we considered whether the policy benefitted differently women coming from the poorest and richest households (see supplementary material for the definition of the wealth quintiles). Second, we looked at the effects for women with low education (no or incomplete primary education) and others. Another important policy question, less frequently studied in the literature on fee removal is whether the quality of care provided in a facility contributed to women's decisions to give birth in a facility, and to changes in health outcomes. We looked at the effects of the policy in areas with low or high quality care at the time of the delivery, based on a proxy indicator for care quality defined based on the average quality of antenatal care received by women in the area (see section D of the online Appendix for more details).

We ran separate difference-in-difference models for each group and we report the policy effect for each sub-group in a graph. To test whether differences across groups were statistically significant, we ran triple-difference models on the relevant analytical sample (i.e. including two groups of interest only),

where the coefficient on the triple interaction term () provides the differential effect between the two groups.

4. Results

Table 2 presents the main results of the difference-in-difference analysis, which can be interpreted as the average effect of the policy change (results from logistic regressions are in Table A1 in the online Appendix). Looking at the first panel of the table, the results indicate an increase in the probability to deliver in a facility by 15 percentage points in rural districts over the 2006–2011 period (95%CI: 0.11 to 0.19, p < 0.0001), and 10 percentage points in peri-urban areas between 2007 and 2011 (0.04–0.17, p = 0.001). Compared to a pre-reform proportion of 39.9% in rural districts and 37.6% in peri-urban areas, this corresponds to an increase in institutional deliveries of 35% and 25% respectively. In a complementary analysis (see Table A2 in online appendix), we show that this increase is entirely driven by a substantial reduction in home births, and not to a substitution away from deliveries in private facilities, which are relatively rare. Results from the second panel provide reassuring evidence that the increased utilisation did not reduce the proportion of assisted deliveries, as increases in this outcome are of the same magnitude as the increase in institutional delivery. There was an increase by 12 percentage points (0.07–0.16, p < 0.0001) in rural districts and 8 percentage points in peri-urban areas (0.02–0.14, p = 0.012). A key question is whether institutional deliveries improved health outcomes for new-borns. We find no evidence that the increase in institutional deliveries translated into a reduction in neonatal deaths (p = 0.570 in rural districts and p = 0.821 in peri-urban areas). Similarly, there is no evidence that the policy had an effect on the proportion of deliveries by caesarean sections (p = 0.457 in rural districts and p = 0.570 in peri-urban areas).

Table 2.

Effects of user fee removal.

| Policy change in rural districts |

Policy change in peri-urban areas |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient (95%CI) | p-value | Coefficient (95%CI) | p-value | |

| Delivered in afacility(institutional delivery) | ||||

| Policy effect | 0.15 (0.11–0.19) | <0.0001 | 0.10 (0.04–0.17) | 0.001 |

| Mean pre-reform in ‘treated’ group | 0.40 | 0.38 | ||

| N | 12927 | 5126 | ||

| R2 | 0.19 | 0.24 | ||

| Deliverywas assisted by qualified health professional(assisted delivery) | ||||

| Policy effect | 0.12 (0.07–0.16) | <0.0001 | 0.08 (0.02–0.14) | 0.012 |

| Mean pre-reform in ‘treated’ group | 0.39 | 0.34 | ||

| N | 12910 | 5119 | ||

| R2 | 0.19 | 0.25 | ||

| Deliveredby Caesarean section | ||||

| Policy effect | 0.01 (−0.02 to 0.04) | 0.457 | 0.01 (−0.02 to 0.04) | 0.570 |

| Mean pre-reform in ‘treated’ group | 0.01 | 0.02 | ||

| N | 12948 | 5132 | ||

| R2 | 0.03 | 0.02 | ||

| Neonataldeaths | ||||

| Policy effect | 0.00 (−0.01 to 0.02) | 0.570 | −0.00 (−0.02 to 0.02) | 0.821 |

| Mean pre-reform in ‘treated’ group | 0.03 | 0.03 | ||

| N | 12,980 | 5144 | ||

| R2 | 0.01 | 0.01 | ||

Notes: Each coefficient comes from an OLS regression that includes year and district fixed effects. Standard errors are clustered at mother level, sampling weights included. The first panel looks at the probability that a woman delivered in a facility. The second panel looks at the probability that the woman delivered assisted by a qualified healthcare professional. The third panel looks at the probability that the delivery was done by C-section. The last panel looks at the probability that the baby died within four weeks of birth (neonatal death).

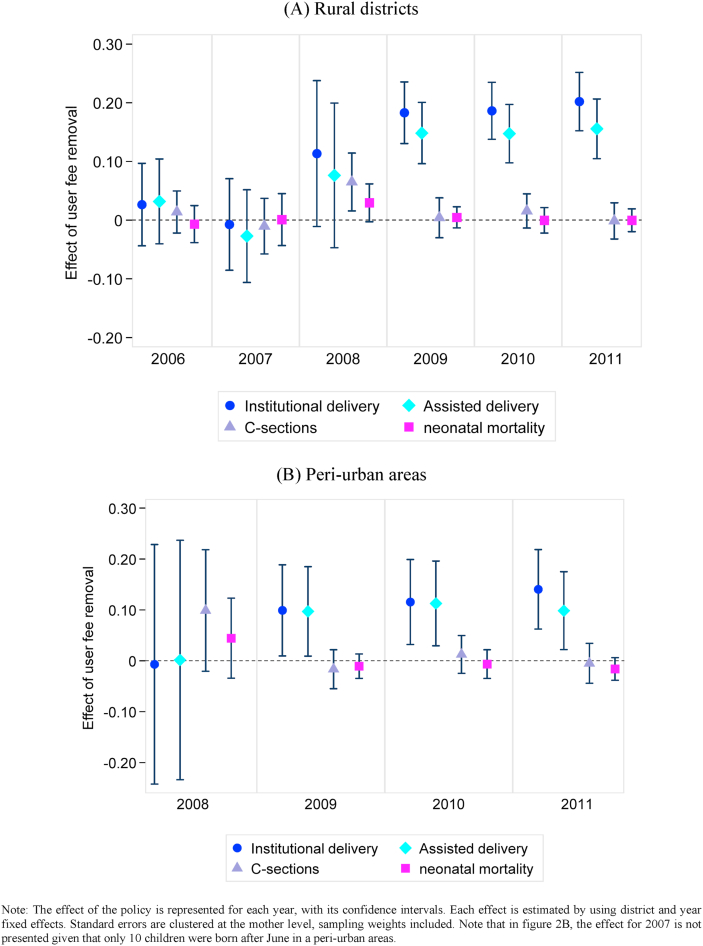

Fig. 1 presents the effects of removing fees over the years following the policy change, for the four main outcomes. Fig. 1A shows the gradual effects of the policy in rural districts while Fig. 1B shows the results for peri-urban areas. The results in both settings are consistent with the idea that it takes some time for women to change their behaviour and start giving birth in facilities. In rural districts, the positive effects of the policy on institutional and assisted deliveries only start to kick off three years after its implementation (the confidence intervals in 2008 are quite large probably due to the limited number of observations, but the point estimate suggests a positive effect). In peri-urban areas, the positive effect appears more quickly, one and a half years after the initial roll-out in June 2017, possibly due to the early lessons gained from the implementation in rural areas. The findings also confirm the absence of effect on caesarean sections and neonatal deaths, except for a small increase in C-sections in 2008 in rural areas, which appears to be a fluke as it does not persist after.

Fig. 1.

Effect of user fees removal on delivery outcomes and neonatal mortality over time.

Note: The effect of the policy is represented for each year, with its confidence intervals. Each effect is estimated by using district and year fixed effects. Standard errors are clustered at the mother level, sampling weights included. Note that in Fig. 2B, the effect for 2007 is not presented given that only 10 children were born after June in a peri-urban areas. Outcomes are defined in the same was as those presented in Table 2.

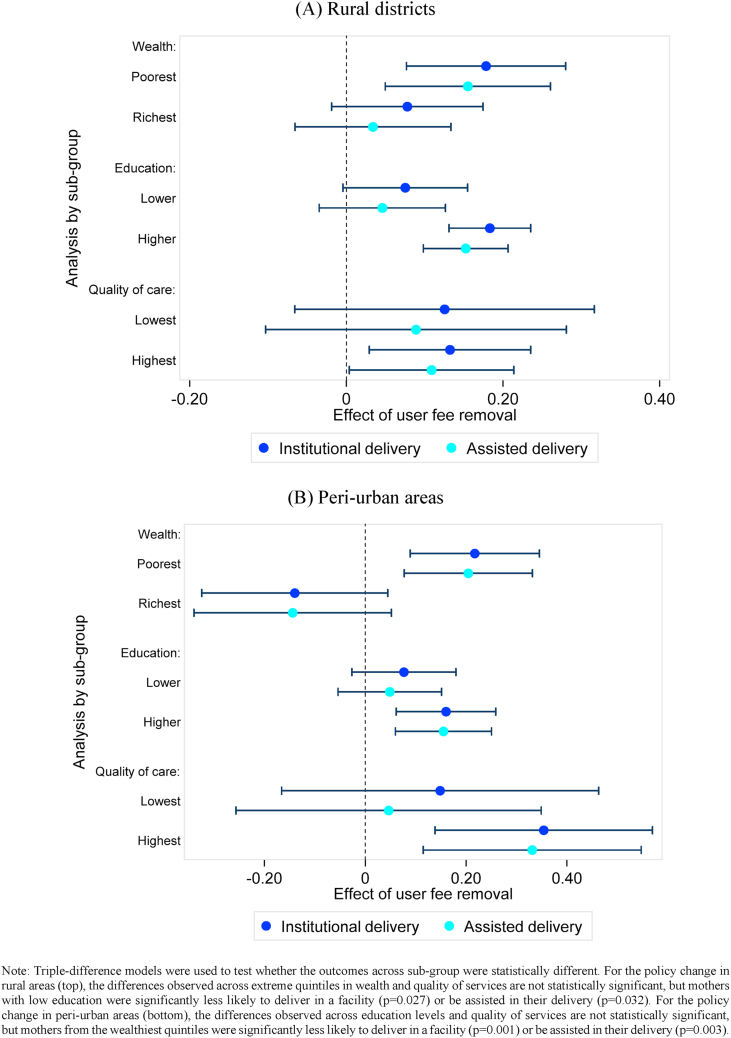

Results of the sub-group analyses are presented in Fig. 2A (rural districts) and 2B (peri-urban areas), while the corresponding results are in the online Appendix (Table A3). Three results emerge. First, women from the poorest quintiles benefited directly from user fee removal, with an 18 percentage points increase in institutional deliveries in rural districts and 22 percentage points in peri-urban areas. By contrast, there was no change in the choices of women from the richest quintile in either group, as most women in these groups were already delivering in facilities before the policy change (76% in rural districts and 80% in peri-urban areas). The difference in effects observed was statistically different in peri-urban areas. Second, despite these encouraging effects about the benefits for women from the poorest quintiles, women with lower education did not deliver more in facilities after the policy chance. In both rural and peri-urban areas, user fee removal led to a large increase in the likelihood of delivery in facilities (assisted and not) for women completing at least primary education, but not for those with no or incomplete primary education. This higher benefit for more educated mothers was statistically different for the rural and peri-urban rollout of the free care policy. Third, the policy change had no statistically significant effect on the proportion of institutional deliveries in areas with the lowest quality of care, while the impact of positive in areas with the highest quality care. This last result could hide some differences across types of providers or facilities (hospitals and mission facilities could be the high-quality places where most of the increase is seen). In some additional analysis presented in Appendix Table A4, we explored whether the policy led to differential changes in deliveries rates in mission facilities, public hospitals and public health centres. We find no evidence that the effect of the policy was stronger in hospitals or mission facilities, compared to health centres. If anything, there was a larger increase in the probability of delivering in health centres, perhaps logically since this is often the closest facility for most people.

Fig. 2.

Heterogeneous effects of user fee removal on the proportion of institutional and assisted deliveries.

Note: Triple-difference models were used to test whether the outcomes across sub-group were statistically different. For the policy change in rural areas (top), the differences observed across extreme quintiles in wealth and quality of services are not statistically significant, but mothers with low education were significantly less likely to deliver in a facility (p = 0.027) or be assisted in their delivery (p = 0.032). For the policy change in peri-urban areas (bottom), the differences observed across education levels and quality of services are not statistically significant, but mothers from the wealthiest quintiles were significantly less likely to deliver in a facility (p = 0.001) or be assisted in their delivery (p = 0.003).

5. Discussion

We analysed the effect of abolishing user fees on birth outcomes in Zambia up to six years after the policy change. Our analysis yielded four key results.

First, we found that within five to six years after the policy implementation, there was a large increase in institutional deliveries, by 25–35% compared to pre-reform levels. These results echo those of similar reforms where free care led to sizeable increase in institutional deliveries (Leone et al., 2016; Fitzpatrick, 2018). They also confirm the key role of financial barriers in accessing needed care.

A second key result was that the positive effects of the reform took time to appear. Consistent with other studies that explored the immediate effects of the policy in Zambia (Chama-Chiliba & Koch, 2016, Lepine et al., 2018), there was no evidence of impact on maternal care-seeking up to two years after the policy change. This absence of short-term effect can be linked to implementation issues that have been documented: confusion about the definition of the policy, and lack of funding to replace lost revenue leading facilities to continue to charge fees (Carasso, Palmer et al., 2010). Our contribution is to show that positive and large effects eventually emerged, suggesting that when those implementation hurdles were overcome, behaviours changed. It is also possible that adoption of new behaviours took time to spread (i.e. delivering in a facility rather than at home). More research would be needed to tease out the relative importance of speed and quality of implementation, against behavioural change.

Our third result relates to the role of quality of care. On the one hand, we found that a reduction in price was not sufficient to increase the demand for institutional deliveries in areas that were plagued by the worst levels of quality of care. On the other hand, we found that despite a large increase in institutional delivery, there was no increase in the proportion of caesarean sections and no reduction in neonatal deaths. Both results point to key deficiencies in access to high quality care that is necessary to turn higher use of care into better health outcomes (Lohela, Campbell et al., 2012, Lohela, Nesbitt, Pekkanen, & Gabrysch, 2019). While it is possible that the reform itself led to deterioration of the quality of care, for example through shortages of essential supplies or drugs (Picazo & Zhao, 2009), other studies have recently underlined key deficiencies in staff skills that may require more structural reforms (Das, Woskie, Rajbhandari, Abbasi, & Jha, 2018; Kruk et al., 2018).

Our final result was that, despite the large improvement in institutional deliveries, some groups remain left out. Our finding that women with lower education did not benefit from the positive effects of the policy reform are consistent with results from other settings (McKinnon, Harper, & Kaufman, 2015) which suggest that this happened either because these women had limited information about the policy or because they were facing higher barriers than other groups (Sochas, 2019; Spangler, 2011; Spangler & Bloom, 2010).

Overall, despite the increase in institutional deliveries following the policy change, about 40% of women still choose to deliver at home. Could this choice be explained by the fact that women are still assisted at home by a skilled birth attendant (i.e. an accredited health professional such as a midwife, doctor, or nurse)? Unfortunately, this is not the case in Zambia, where 44% of deliveries at home were assisted by a traditional birth attendant, 46% by a relative or a friend, 11% were on their own. Together with the lower effect in less educated women, this persistent high proportion of home deliveries point to the role of three other barriers that have been shown to play a role in maternal care-seeking in Zambia. First, despite the removal of fees, economic barriers persist through indirect costs. In particular, distance to facilities and lack or cost of transport, are the most cited reason explaining the choice of home deliveries in the DHS data. 45% of women who delivered at home say the facility was too far or there was no transport, and 4% that it would cost too much. Detailed information collected in the 1998 national Living Conditions and Monitoring Survey (LCMS) suggests that indirect and non-medical costs (transport costs, drugs bought outside the facility, and food and caregiver costs) could still be a key financial obstacle, as they used to represent 35% of all expenses related to care-seeking for the richest quintile, and as much as 50% for the poorest quintile (see Appendix Figure B6). Second, home deliveries have been shown to be driven by women's lack of agency in decision-making regarding childbirth, and their dependence on their family and their husbands (Sialubanje, Massar et al., 2015). As a result, women may not be able to plan ahead of time and get organised to deliver in a facility – 21% of women in the DHS data reported an “emergency labour” as a reason to remain at home. Finally, the prevalence of traditional beliefs, likely to be more entrenched in women with lower education, have also been shown to contribute to under-estimate risk factors, which can lead to lack of or delays in care-seeking (Ashraf, Field, Rusconi, Voena, & Ziparo, 2017). In the DHS sample, 15% of women reported that they had given birth at home because it was “not necessary” to go to a health facility.

This study has several strengths. We used nationally representative survey data to establish the systemic effects of a national reform over a long period of time. We were able to evaluate two policy changes on a range of key maternal health related outcomes. Additionally, we were able to explore the effects of the policy for groups and in different environments, allowing us to examine the distributional effects of the policy and its potential limitations.

Some limitations of the study should be noted. Firstly, because the location of sampling clusters is randomly displaced in the DHS for confidentiality reasons, by up to 2 km for urban clusters and 5 km for rural clusters, we may have assigned some clusters to the wrong treatment status. Yet this problem is unlikely to be widespread, and the measurement errors and bias created by this issue are unlikely to compromise our main results given that random measurement error leads to an attenuated-biased toward zero OLS point estimate (Wooldridge, 2015). In addition, there could have been migration of mothers leading to a misclassification of the treatment and control groups. Plus, some households in urban areas may have sought care where care was free (Lepine, Lagarde et al., 2018). These issues would have led to under-estimating the true effect of the policy and does not challenge our conclusion that the policy increase in institutional deliveries. Our results are also robust to excluding three districts where such health seeking patterns were particularly prevalent (See Online Appendix E). Thirdly, the fact that C-sections and neonatal deaths are relatively rare events means that we had few observations and coefficients should be interpreted with caution. However, at least for the probability to deliver by a C-section, the study should have been able to detect increases by 1–2 percentage points, which did not occur.

The study makes an important contribution to the literature on the effects of user fees, and more broadly to the current debates on how to achieve universal health coverage. Results highlight that the benefits of health financing reforms can be slow to emerge, do not always materialise for the most vulnerable populations, and will not automatically translate into better health outcomes. The concomitant introduction of supporting policies may be necessary to encourage behavioural change, especially for disadvantaged groups. Incentives to deliver in facilities that cover expenses linked to transport have been shown to be effective in some countries (Powell-Jackson & Hanson, 2012). Encouraging women at risk to go to maternal waiting homes (MWH) located next to facilities providing emergency obstetric care has shown promising results (Dadi, Bekele et al., 2018), although acceptability and maintenance of MWH remain a challenge (Penn-Kekana et al., 2017). Engaging marginalised women through collective action in small local groups has also shown promising results in Asian countries (Prost et al., 2013), although strategies engaging husbands and the broader communities may also be necessary to empower women and change social norms (Tokhi, Comrie-Thomson et al., 2018, Gram et al., 2019). Beyond studies testing the feasibility and effectiveness of such strategies in Zambia, research is also needed to unpack the complex impact of health financing reforms on the provision of care, especially on quality of care, and its interplay with the demand for health services.

Ethical statement

All the authors mentioned in the manuscript have agreed for authorship, read and approved the manuscript, and given consent for submission and subsequent publication of the manuscript.

The order of authorship has been agreed by all named authors.

The manuscript in part or in full has not been submitted anywhere. However, following the practice of disseminating pre-print publications, a previous version of the manuscript has been posted on medRxiv: https://medrxiv.org/cgi/content/short/2021.05.18.21257410v1

No ethical approval was needed as this study consists of a secondary analysis of DHS data that are publicly available to all. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants in the DHS surveys.

Credit author statement

Mylene Lagarde: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Formal Analysis, Data curation, Writing- Original draft preparation, Writing- Review and Editing. Aurelia Lepine: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Data curation, Writing- Review and Editing. Collins Chansa: Conceptualization, Validation.

Declaration of interest statement

Collins Chansa was working in the Ministry of Health of the Government of Zambia at the time of the health financing reform evaluated in this paper.

Acknowledgment

AL acknowledges funding from the UK Medical Research Council (grant ref. MR/L012057/1). The funder was not involved in any aspect of the research.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2022.101051.

Contributor Information

Mylene Lagarde, Email: M.Lagarde@lse.ac.uk.

Aurélia Lépine, Email: a.lepine@ucl.ac.uk.

Collins Chansa, Email: cchansa@worldbank.org.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data to this article:

References

- Akin J.S., Griffin C.C., Guilkey D.K., Popkin B.M. The demand for primary health care services in the Bicol region of the Philippines. Economic Development and Cultural Change. 1986:755–782. [Google Scholar]

- Ansah E.K., Narh-Bana S., Asiamah S., Dzordzordzi V., Biantey K., Dickson K., Gyapong J.O., Koram K.A., Greenwood B.M., Mills A., Whitty C.J.M. Effect of removing direct payment for health care on utilisation and health outcomes in Ghanaian children: A randomised controlled trial. PLoS Medicine. 2009;6(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashraf N., Field E., Rusconi G., Voena A., Ziparo R. Traditional beliefs and learning about maternal risk in Zambia. The American Economic Review. 2017;107(5):511–515. doi: 10.1257/aer.p20171106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates I., Chapotera G., McKew S., Van Den Broek N. Maternal mortality in sub‐Saharan Africa: The contribution of ineffective blood transfusion services. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2008;115(11):1331–1339. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belizán J.M., Minckas N., McClure E.M., Saleem S., Moore J.L., Goudar S.S., Esamai F., Patel A., Chomba E., Garces A.L., Althabe F., Harrison M.S., Krebs N.F., Derman R.J., Carlo W.A., Liechty E.A., Hibberd P.L., Buekens P.M., Goldenberg R.L. An approach to identify a minimum and rational proportion of caesarean sections in resource-poor settings: A global network study. Lancet Global Health. 2018;6(8) doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30241-9. e894–e901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carasso B.S., Lagarde M., Cheelo C., Chansa C., Palmer N. Health worker perspectives on user fee removal in Zambia. Human Resources for Health. 2012;10(1):40. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-10-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carasso B., Palmer N., Gilson L. London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine; London: 2010. A policy analysis of the removal of user fees in Zambia. [Google Scholar]

- Central Statistical Office . Lusaka, Central Statistical Office; 2008. The 2006 Zambia living conditions monitoring survey. [Google Scholar]

- Chama-Chiliba C.M., Koch S.F. An assessment of the effect of user fee policy reform on facility-based deliveries in rural Zambia. BMC Research Notes. 2016;9(1):504. doi: 10.1186/s13104-016-2316-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheelo C., Chama C., Pollen G., Carasso B., Palmer N., Jonsson D., Lagarde M., Chansa C. University of Zambia; Lusaka: 2010. Do user fee revenues matter? Assessing the influences of the removal of user fees on health financial resources in Zambia. Department of economics, working paper No. 2010/1. [Google Scholar]

- Dadi T.L., Bekele B.B., Kasaye H.K., Nigussie T. Role of maternity waiting homes in the reduction of maternal death and stillbirth in developing countries and its contribution for maternal death reduction in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Health Services Research. 2018;18 doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3559-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das J., Woskie L., Rajbhandari R., Abbasi K., Jha A. Rethinking assumptions about delivery of healthcare: Implications for universal health coverage. BMJ. 2018;361 doi: 10.1136/bmj.k1716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzakpasu S., Powell-Jackson T., Campbell O.M.R. Impact of user fees on maternal health service utilization and related health outcomes: A systematic review. Health Policy and Planning. 2014;29(2):137–150. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czs142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick A. The price of labor: Evaluating the impact of eliminating user fees on maternal and infant health outcomes. AEA Papers and Proceedings. 2018;108:412–415. [Google Scholar]

- Gage A.J. Barriers to the utilization of maternal health care in rural Mali. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;65(8):1666–1682. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Government of the Republic of Zambia . 1991. National health policies and strategies. [Google Scholar]

- Government of the Republic of Zambia . Ministry of Health; Lusaka, Zambia: 2006. Update on the implementation of the user fee removal policy. [Google Scholar]

- Government of the Republic of Zambia . Ministry of Health; Lusaka, Zambia: 2007. Health sector joint annual review report 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gram L., Morrison J., Saville N., Yadav S.S., Shrestha B., Manandhar D., Costello A., Skordis-Worrall J. Do participatory learning and action women's groups Alone or combined with cash or food transfers expand women's agency in rural Nepal? Journal of Development Studies. 2019;55(8):1670–1686. doi: 10.1080/00220388.2018.1448069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hangoma P., Robberstad B., Aakvik A. Does free public health care increase utilization and reduce Spending? Heterogeneity and long-term effects. World Development. 2018;101:334–350. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.05.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller P.S. A model of the demand for medical and health services in Peninsular Malaysia. Social Science & Medicine. 1982;16(3):267–284. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(82)90337-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton S., Levin C. 2016. Cost-effectiveness of interventions for reproductive, maternal, neonatal, and child health. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan A.A., Zahidie A., Rabbani F. Interventions to reduce neonatal mortality from neonatal tetanus in low and middle income countries - a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):1–7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruk M.E., Gage A.D., Arsenault C., Jordan K., Leslie H.H., Roder-DeWan S., Adeyi O., Barker P., Daelmans B., Doubova S.V., English M., Elorrio E.G., Guanais F., Gureje O., Hirschhorn L.R., Jiang L., Kelley E., Lemango E.T., Liljestrand J.…Pate M. High-quality health systems in the Sustainable development goals era: Time for a revolution. Lancet Global Health. 2018;6(11):e1196–e1252. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30386-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagarde M., Palmer N. The impact of user fees on utilisation of health services in low and middle income countries – how strong is the evidence? WHO Bulletin. 2008;86(11):839–848. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.049197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leone T., Cetorelli V., Neal S., Matthews Z. Financial accessibility and user fee reforms for maternal healthcare in five sub-Saharan countries: A quasi-experimental analysis. BMJ Open. 2016;6(1) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepine A., Lagarde M., Le Nestour A. How effective and fair is user fee removal? Evidence from Zambia using a pooled synthetic control. Health Economics. 2018;27(3):493–508. doi: 10.1002/hec.3589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohela T.J., Campbell O.M., Gabrysch S. Distance to care, facility delivery and early neonatal mortality in Malawi and Zambia. PLoS One. 2012;7(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohela T.J., Nesbitt R.C., Pekkanen J., Gabrysch S. Comparing socioeconomic inequalities between early neonatal mortality and facility delivery: Cross-sectional data from 72 low-and middle-income countries. Scientific Reports. 2019;9(1):1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-45148-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinnon B., Harper S., Kaufman J.S. Who benefits from removing user fees for facility-based delivery services? Evidence on socioeconomic differences from Ghana, Senegal and Sierra Leone. Social Science & Medicine. 2015;135:117–123. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinnon B., Harper S., Kaufman J.S., Bergevin Y. Removing user fees for facility-based delivery services: A difference-in-differences evaluation from ten sub-Saharan African countries. Health Policy and Planning. 2015;30(4):432–441. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czu027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan B., Turbat V. World Bank Publications; 1995. Cost recovery in public health services in sub-Saharan Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Penn-Kekana L., Pereira S., Hussein J., Bontogon H., Chersich M., Munjanja S., Portela A. Understanding the implementation of maternity waiting homes in low- and middle-income countries: A qualitative thematic synthesis. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2017;17(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1444-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Heydrich C., Warren J.L., Burgert C.R., Emch M.E. ICF International; Maryland, USA: 2013. Guidelines on the use of DHS GPS data. Spatial analysis reports No. 8. Calverton. [Google Scholar]

- Picazo O.F., Zhao F. World Bank Publications; 2009. Zambia health sector public expenditure review: Accounting for resources to improve effective service coverage. [Google Scholar]

- Powell-Jackson T., Hanson K. Financial incentives for maternal health: Impact of a national programme in Nepal. Journal of Health Economics. 2012;31(1):271–284. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2011.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell-Jackson T., Hanson K., Whitty C.J.M., Ansah E.K. Who benefits from free healthcare? Evidence from a randomized experiment in Ghana. Journal of Development Economics. 2014;107(Supplement C):305–319. [Google Scholar]

- Prost A., Colbourn T., Seward N., Azad K., Coomarasamy A., Copas A., Houweling T.A.J., Fottrell E., Kuddus A., Lewycka S., MacArthur C., Manandhar D., Morrison J., Mwansambo C., Nair N., Nambiar B., Osrin D., Pagel C., Phiri T.…Costello A. Women's groups practising participatory learning and action to improve maternal and newborn health in low-resource settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2013;381(9879):1736–1746. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60685-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saksena P., Xu K., Elovainio R., Perrot J. Health services utilization and out-of-pocket expenditure at public and private facilities in low-income countries. World Health Report. 2010;20:20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sautmann A., Brown S., Dean M. World Bank; Washington, DC: 2020. Subsidies, information, and the timing of Children's health care in Mali, policy research working paper;No. 9486. [Google Scholar]

- Say L., Chou D., Gemmill A., Tunçalp Ö., Moller A.-B., Daniels J., Gülmezoglu A.M., Temmerman M., Alkema L. Global causes of maternal death: A WHO systematic analysis. Lancet Global Health. 2014;2(6):e323–e333. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70227-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sepehri A., Chernomas R. Are user charges efficiency‐and equity‐enhancing? A critical review of economic literature with particular reference to experience from developing countries. Journal of International Development: Journal of Developments in Sustainable Agriculture. 2001;13(2):183–209. [Google Scholar]

- Sialubanje C., Massar K., van der Pijl M.S.G., Kirch E.M., Hamer D.H., Ruiter R.A.C. Improving access to skilled facility-based delivery services: Women's beliefs on facilitators and barriers to the utilisation of maternity waiting homes in rural Zambia. Reproductive Health. 2015;12 doi: 10.1186/s12978-015-0051-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sochas L. Women who break the rules: Social exclusion and inequities in pregnancy and childbirth experiences in Zambia. Social Science & Medicine. 2019;232:278–288. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spangler S.A. To open oneself is a poor woman's trouble”: Embodied inequality and childbirth in South–Central Tanzania. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 2011;25(4):479–498. doi: 10.1111/j.1548-1387.2011.01181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spangler S.A., Bloom S.S. Use of biomedical obstetric care in rural Tanzania: The role of social and material inequalities. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;71(4):760–768. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson J. Maternal death. JAMA. 2006;295(19) 2240-2240. [Google Scholar]

- Tokhi M., Comrie-Thomson L., Davis J., Portela A., Chersich M., Luchters S. Involving men to improve maternal and newborn health: A systematic review of the effectiveness of interventions. PLoS One. 2018;13(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0191620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNDP . United Nations Development Programme; New York, NY USA: 2006. Human development report. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel R.J. Cost recovery in the health‐care sector in Sub‐Saharan Africa. The International Journal of Health Planning and Management. 1991;6(3):167–191. [Google Scholar]

- WHO . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2010. The world health report: Health systems financing: The path to universal coverage. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2020. World health statistics 2020: Monitoring health for the SDGs, sustainable development goals. [Google Scholar]

- Wooldridge J.M. Cengage learning; 2015. Introductory econometrics: A modern approach. [Google Scholar]

- Zombré D., De Allegri M., Platt R.W., Ridde V., Zinszer K. An evaluation of healthcare use and child morbidity 4 Years after user fee removal in rural Burkina Faso. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2019;23(6):777–786. doi: 10.1007/s10995-018-02694-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.