Key Points

Question

Among recipients of opioid agonist therapy (OAT) in Ontario, Canada, early in the COVID-19 pandemic, was there an association between dispensing of increased take-home doses and treatment retention or opioid-related harm?

Findings

In this retrospective propensity-weighted cohort study of 21 297 OAT recipients stratified by baseline dosing and type of OAT, dispensing of increased take-home doses of OAT, compared with no change in take-home doses, was significantly associated with lower rates of OAT interruption and discontinuation in most subsets, with no statistically significant increases in opioid overdoses over 6 months of follow-up.

Meaning

In Ontario, Canada, during the COVID-19 pandemic, dispensing of increased take-home doses of OAT was significantly associated with lower rates of treatment interruption and discontinuation among some subsets of patients, and there were no statistically significant increases in opioid-related overdoses, although the findings may be susceptible to residual confounding and should be interpreted cautiously.

Abstract

Importance

During the COVID-19 pandemic, modified guidance for opioid agonist therapy (OAT) allowed prescribers to increase the number of take-home doses to promote treatment retention. Whether this was associated with an increased risk of overdose is unclear.

Objective

To evaluate whether increased take-home doses of OAT early in the COVID-19 pandemic was associated with treatment retention and opioid-related harm.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A retrospective propensity-weighted cohort study of 21 297 people actively receiving OAT on March 21, 2020, in Ontario, Canada. Changes in OAT take-home dose frequency were assessed between March 22, 2020, and April 21, 2020, and individuals were observed for up to 180 days to assess outcomes (last date of follow-up, October 18, 2020).

Exposures

Exposure was defined as extended take-home doses in the first month of the pandemic within each of 4 cohorts based on OAT type and baseline take-home dose frequency (daily dispensed methadone, 5-6 take-home doses of methadone, daily dispensed buprenorphine/naloxone, and 5-6 take-home doses of buprenorphine/naloxone).

Main Outcomes and Measures

Primary outcomes were opioid overdose, interruption in OAT, and OAT discontinuation.

Results

Among 16 862 methadone and 4435 buprenorphine/naloxone recipients, the median age ranged between 38 and 42 years, and 29.1% to 38.2% were women. Among individuals receiving daily dispensed methadone (n = 5852), initiation of take-home doses was significantly associated with lower risks of opioid overdose (6.9% vs 9.5%/person-year; weighted hazard ratio [HR], 0.73 [95% CI, 0.56-0.96]), treatment discontinuation (51.0% vs 63.6%/person-year; weighted HR, 0.80 [95% CI, 0.72-0.90]), and treatment interruption (19.0% vs 23.9%/person-year; weighted HR, 0.80 [95% CI, 0.67-0.95]) compared with no change in take-home doses. Among individuals receiving daily dispensed buprenorphine/naloxone (n = 662), there was no significant difference in any outcomes between exposure groups. Among individuals receiving weekly dispensed OAT (n = 11 010 for methadone; n = 3773 for buprenorphine/naloxone), extended take-home methadone doses were significantly associated with lower risks of OAT discontinuation (14.1% vs 19.6%/person-year; weighted HR, 0.72 [95% CI, 0.62-0.84]) and interruption in therapy (5.1% vs 7.4%/person-year; weighted HR, 0.69 [95% CI, 0.53-0.90]), and extended take-home doses of buprenorphine/naloxone were significantly associated with lower risk of interruption in therapy (9.5% vs 12.9%/person-year; weighted HR, 0.74 [95% CI, 0.56-0.99]) compared with no change in take-home doses. Other primary outcomes were not significantly different between groups.

Conclusions and Relevance

In Ontario, Canada, during the COVID-19 pandemic, dispensing of increased take-home doses of opioid agonist therapy was significantly associated with lower rates of treatment interruption and discontinuation among some subsets of patients receiving opioid agonist therapy, and there were no statistically significant increases in opioid-related overdoses over 6 months of follow-up. These findings may be susceptible to residual confounding and should be interpreted cautiously.

This cohort study compared rates of therapy discontinuation and interruption among 21 297 people who received increased take-home doses of opioid agonist therapy during the early COVID-19 pandemic.

Introduction

Opioid agonist therapy (OAT) with methadone or buprenorphine/naloxone reduces the risks of relapse and death among patients with opioid use disorder.1,2,3 Yet, 6-month treatment retention rates range from 30% to 50%.4,5,6,7 One significant barrier to treatment retention is the requirement for prolonged daily observed dosing at pharmacies or opioid treatment programs until strict criteria are met to allow take-home doses.7,8 Historically, patients have been deemed eligible for graduated numbers of take-home doses after completing a minimum of 60 to 90 days in treatment with consistently negative urine toxicology tests. These criteria are due to concerns about the risks of OAT diversion or misuse leading to overdose.9 Although OAT delivery differs slightly between Canada and the US,10 the timing and frequency of take-home dose provision is similar.2,9

Treatment retention is a critical goal of OAT because it is associated with a lowered risk of overdose.11 Therefore, in light of concerns about pandemic-associated health care disruptions and the need for physical distancing during an ongoing overdose crisis, measures to support continued access to OAT were rapidly implemented in many countries.12,13 In the US, federal authority gave states permission to request up to 28 days of take-home medication for stable patients and up to 14 days for less stable patients.12 In Ontario, new guidance released on March 22, 2020, also allowed the provision of extended take-home doses based on clinicians’ assessment of social stability and ability to store doses safely.13

With this new guidance, it was anticipated that there would be increased use of OAT take-home doses, including for patients previously deemed ineligible for this type of dispensing. The objective of this study was to evaluate whether increased access to take-home doses of OAT related to pandemic-specific guidance was associated with changes in treatment retention and opioid-related harms among individuals receiving OAT in Ontario, Canada.

Methods

Study Design and Setting

We conducted a retrospective, population-based propensity-weighted cohort study to examine the relationship between the clinical decision to increase numbers of take-home doses of OAT and patient outcomes among residents of Ontario, Canada, actively being treated with either methadone or buprenorphine/naloxone for OAT on March 21, 2020. We used an accrual window of February 22, 2020, to March 21, 2020, to establish ongoing OAT and take-home dose patterns at the time of the OAT guidance change and an exposure window of March 22, 2020, to April 21, 2020, to establish increases in number of take-home doses. All individuals were observed for 180 days to establish outcomes of interest. The reporting of this study followed the STROBE reporting guidelines. The use of data in this project was authorized under section 45 of Ontario’s Personal Health Information Protection Act, which did not require informed consent or review by a research ethics board.14

Data Sources

We used data housed at ICES, an independent, nonprofit research institute in Ontario with legal status that allows for the collection and analysis of administrative health care and demographic data without consent, for health system evaluation and improvement. Main data sources included the Narcotics Monitoring System and the Drug and Drug-Alcohol Related Death database. OAT prescriptions were identified using the Narcotics Monitoring System database, which successfully links 97.7% of all prescription claims for controlled substances in Ontario to other databases within the ICES repository. More details on databases used can be found in eTable 1 (Supplement). These data sets were linked using unique encoded identifiers and analyzed at ICES.

Cohort Definition

We constructed 4 cohorts of individuals actively treated with OAT on March 21, 2020, (the day before the release of the new guidance) based on OAT type and take-home dose frequency at baseline. Each cohort included individuals dispensed OAT (methadone or buprenorphine/naloxone) with a prescription duration that overlapped March 21, 2020, who had at least 14 of the 28 days prior to March 21, 2020, covered with the same OAT. Each cohort was further stratified according to their take-home dose status in the week prior to March 21, 2020. Specifically, the 4 cohorts were those receiving OAT under 1 of the following regimens: (1) daily dispensed methadone (maximum day supply of 1 for all prescriptions in the prior week), (2) daily dispensed buprenorphine/naloxone (maximum day supply of 1 for all prescriptions in the prior week), (3) approximately weekly dispensed methadone (at least 1 day when 5 or 6 take-home doses were dispensed in the prior week), and (4) approximately weekly dispensed buprenorphine/naloxone (at least 1 day when 5 or 6 take-home doses were dispensed in the prior week) (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). Within all cohorts, we excluded individuals with missing patient identifiers, non-Ontario residents (because ICES only captures complete health data for Ontario residents), those with missing age or sex, those with a recorded death date prior to their index date, those aged younger than 18 or older than 105 years, those diagnosed with COVID-19 prior to the index date (to ensure no prior COVID-19 when studying this diagnosis as an outcome), and those not meeting inclusion criteria for any of the 4 cohorts. In addition, to ensure that each included individual had a physician encounter during their exposure window during which a change in take-home dose frequency could have occurred, individuals with no physician claim related to OAT or addiction medicine (Ontario Health Insurance Plan fee codes A957, K680, K682, K683) during our exposure window were excluded.

Exposure Definition

Within each cohort, we identified all prescriptions for OAT dispensed during the exposure window (March 22, 2020, to April 21, 2020) and determined the number of take-home doses on each prescription. In this analysis, we did not include any dispenses occurring between April 10, 2020, and April 13, 2020, as this was the Easter weekend, during which brief, extended take-home doses may have been provided on account of reduced pharmacy hours. Using these data, we classified people in each cohort into 2 exposure groups according to whether a clinical decision was made to increase their take-home dose status during the exposure window in alignment with revised pandemic guidance. Among the methadone-treated cohort, those previously receiving daily dispensed methadone were defined as exposed if they began receiving any number of take-home doses over the exposure window (ie, any dispense with duration >1 day). Among methadone-treated individuals previously receiving 5 to 6 take-home doses, exposure was defined as an increase to at least 13 take-home doses (ie, a 2-week supply including the observed dose). In each methadone cohort, unexposed individuals were those whose take-home dose level did not change throughout the exposure window (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). In the buprenorphine/naloxone-treated cohort, exposure status was defined similarly for both the daily dispensed cohort and those previously receiving 5 to 6 take-home doses. In each of these cohorts, exposure was defined as a clinical decision to increase to at least 13 take-home doses (ie, a 2-week supply including the observed dose), and unexposed individuals were those whose take-home dose level did not change (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). We excluded individuals whose take-home dose frequency changed but did not meet the threshold required by our exposure definition (eg, buprenorphine/naloxone recipients receiving 7 to 12 take-home doses during the exposure window).

In all cohorts, the index date was defined as the first date of an increase in take-home dose level among exposed individuals. Among those unexposed, the index date was defined as the first date of a physician visit related to OAT or addictions medicine (defined above) during the exposure window. All unexposed individuals were also required to still be actively treated with OAT on this assigned index date. We analyzed patients based on their take-home dose levels during the exposure window, regardless of whether there were additional changes in dispensing patterns over the study follow-up. Therefore, an individual’s take-home dose levels could continue to change during follow-up, yet they were still analyzed based on their exposure status as defined during the exposure window.

Outcomes

Our primary outcomes were fatal or nonfatal opioid overdose, interruption in OAT, and OAT discontinuation. We identified coroner-confirmed fatal opioid overdoses using the Drug and Drug-Alcohol Related Death database, and defined nonfatal opioid overdoses as any emergency department visit or inpatient hospitalization with a diagnosis of opioid toxicity (International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision diagnosis codes T40.0, T40.1, T40.2, T40.3, T40.4, T40.6). We defined an interruption in OAT as a gap in therapy of 5 to 14 days, and an OAT discontinuation was defined as a gap in therapy exceeding 14 days. Gaps in therapy were defined as the period of time between the completion of a prior OAT dispense (ie, dispense date plus day supply) and a subsequent OAT dispensing. In secondary analyses, we modeled fatal opioid overdoses separately and investigated all-cause mortality and COVID-19 diagnosis.

Within each of the 4 cohorts, we observed individuals for a maximum of 180 days from their index date until the outcome of interest or death, whichever occurred first. Opioid overdose-related outcomes were censored at non-opioid-related death (instead of all-cause death), and outcomes related to OAT interruption or discontinuation were also censored at switch to a different type of OAT (ie, from methadone to buprenorphine/naloxone or vice versa) or hospital admission (eTable 2 in the Supplement).

Statistical Analysis

Within each of the 4 cohorts, we fit a propensity-score model to estimate the probability of change in take-home doses conditional on demographic (age, sex, neighborhood income quintile, and urban location of residence), clinical (concurrent benzodiazepine prescription, alcohol use disorder, mental health diagnoses, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, HIV, OAT dose, proportion of previous 28 days covered with OAT), and health service use (recent opioid overdose, recent indication of stimulant-related harm or dependence, recent indication of sedative/hypnotic harm or dependence, number of opioid use disorder–related physician visits, number of non-opioid use disorder–related physician visits, ≥1 emergency department visit, ≥1 hospitalization) variables selected, based on past literature and clinical judgement (eTable 3 in the Supplement). Stabilized inverse probability of treatment weights (sIPTW) were derived based on the propensity score for each cohort to reduce the influence of individuals with large weights. Baseline characteristics were summarized using descriptive statistics, and we used absolute standardized differences, weighted by sIPTW, to test for meaningful differences between groups, with a value greater than 0.10 suggesting imbalance between groups.15 Missing values for categorical data were grouped separately. There were no missing data for any continuous variables. Cox proportional hazards models were fit for each cohort to compare outcomes between exposed and unexposed individuals, weighted on the sIPTW, and the proportional hazards assumptions were confirmed using time-varying exposure status and by visually inspecting log-negative-log survival curves. Although the original plan was to examine the relationship between changes in take-home doses of OAT and COVID-19 diagnosis, the small number of these events prevented these analyses. A 2-sided type I error rate of .05 was used for all comparisons. Because of the potential for type I error due to multiple comparisons, findings for the analyses should be interpreted as exploratory. All analyses were conducted at ICES using SAS Enterprise Guide 7.1.

Post Hoc Sensitivity Analyses

We conducted several post hoc sensitivity analyses. First, models for each primary outcome were stratified according to the proportion of patients prescribed extended take-home doses for each prescriber, defined as the proportion of their patients in the cohort who were exposed. Methadone cohorts were categorized as people treated by physicians with low (≤25th percentile), moderate (middle 50th percentile), or high (>75th percentile) proportions of their patients receiving extended take-home doses. Buprenorphine/naloxone cohorts, which were smaller, were categorized as people treated by physicians with low (lowest 50th percentile) and high (highest 50th percentile) proportions of patients receiving extended take-home doses. Second, models were stratified according to prescriber practice size, defined as the total number of patients who were prescribed OAT by each provider during the accrual and exposure windows. Categories of practice volume were defined as low volume (≤149 patients), moderate volume (150-349 patients), and high volume (≥350 patients), based on distribution of the data (lowest 50th percentile, 51st to 80th percentile, and top 20th percentile). Due to its small size, the buprenorphine/naloxone daily dispensed cohort was stratified into low/moderate–volume (≤349 patients) and high-volume (≥350 patients) prescribers. Third, a post hoc within-person analysis was conducted that compared the prevalence of nonfatal opioid overdose in the 180 days prior to and following the index date. Exact McNemar tests were used to evaluate differences separately among exposed and unexposed individuals in each cohort. Fourth, the proportion of overdoses that occurred during follow-up while the individual was still receiving OAT was compared with the proportion that occurred after individuals discontinued treatment.

Results

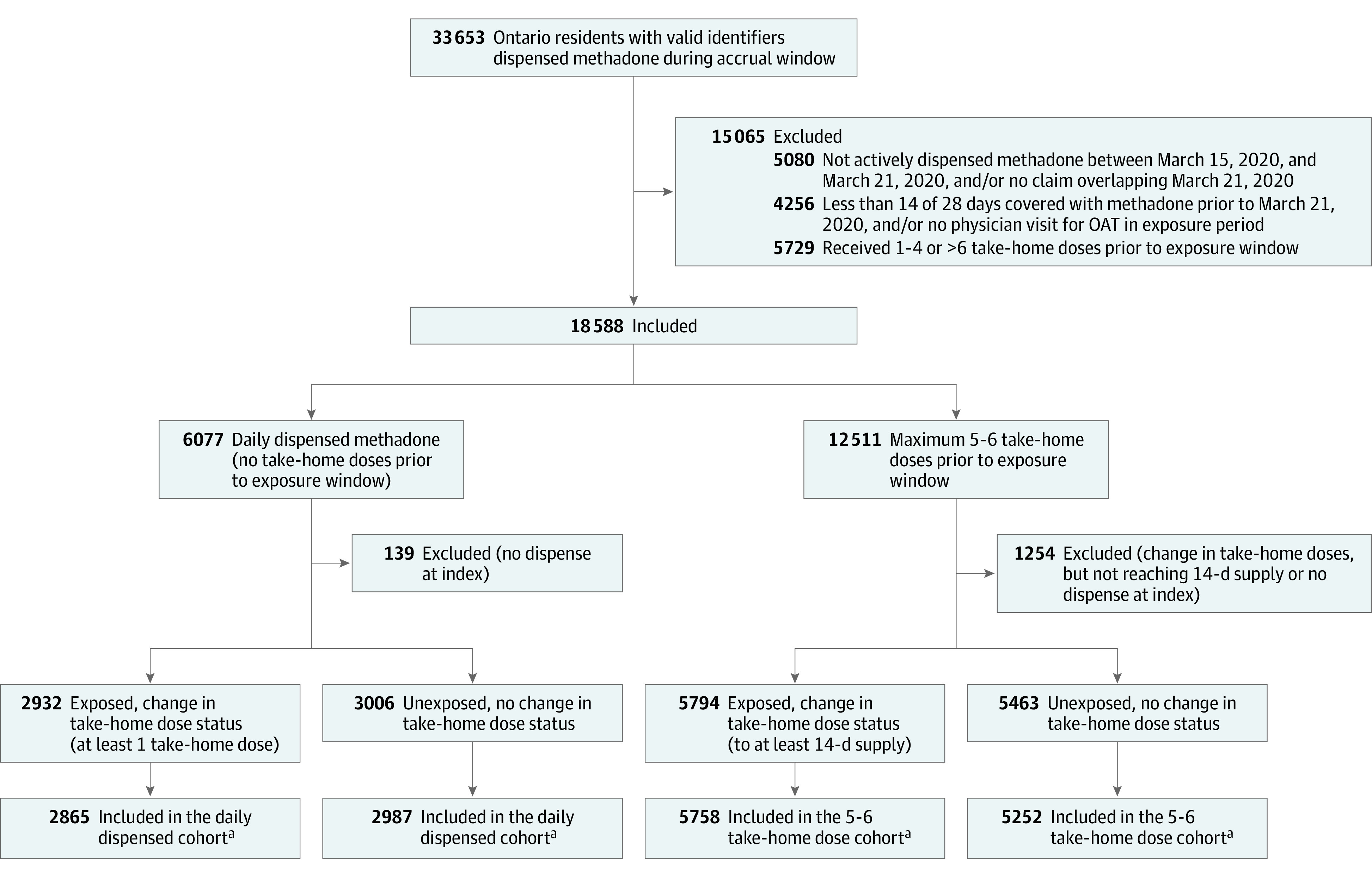

The numbers of individuals meeting inclusion criteria were 5852 methadone recipients and 662 buprenorphine/naloxone recipients in the 2 daily dispensed cohorts, and for the 2 cohorts of individuals receiving 5 to 6 take-home doses prior to the exposure window, 11 010 methadone recipients and 3773 buprenorphine/naloxone recipients met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1 and Figure 2). The median age of included individuals ranged between 38 and 42 years, approximately one-third (29.1%-38.2%) of patients were women, and most (80.9%-89.9%) resided in urban centers (Table 1). Hospitalization for opioid overdose prior to the index date was more common among patients receiving daily dispensed OAT prior to the pandemic (range, 3.7%-7.5%) compared with patients dispensed 5 or 6 take-home doses (range, 0.9%-1.4%). Health service use was high in all cohorts, with approximately half of all patients having an ED visit in the prior year (range across all groups, 35.1%-55.6%). After propensity-score weighting, all baseline characteristics were balanced between exposure groups in each cohort studied (eFigure 2 and eTable 4 in the Supplement).

Figure 1. Cohort Selection Among Methadone Recipients.

aIndicates the number of individuals included after excluding those with missing demographics, age younger than 18 years or older than 105 years, prior COVID-19 diagnosis, and no active treatment on the index date. OAT indicates opioid agonist therapy.

Figure 2. Cohort Selection Among Buprenorphine/Naloxone Recipients.

OAT indicates opioid agonist therapy.

aInstitutional policy requires suppression of counts less than 6. Therefore, some numbers have been suppressed to avoid disclosure of small cells related to exclusion criteria.

bIndicates the number of individuals included after excluding those with missing demographics, age younger than 18 years or older than 105 years, prior COVID-19 diagnosis, and no active treatment on the index date.

Table 1. Unweighted Baseline Characteristics by OAT Type, Cohort, and Exposure Statusa.

| Dispensed prior to COVID-19, No. (%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methadone | Buprenorphine/naloxone | |||||||

| Daily | Weekly | Daily | Weekly | |||||

| Change in take-home dose status | No change in take-home dose status | Change in take-home dose status | No change in take-home dose status | Change in take-home dose status | No change in take-home dose status | Change in take-home dose status | No change in take-home dose status | |

| No. of individuals | 2865 | 2987 | 5758 | 5252 | 230 | 432 | 2138 | 1635 |

| Age, median (IQR), y | 38 (32-47) | 38 (32-47) | 42 (34-52) | 40 (33-51) | 38 (32-49) | 38 (33-45) | 41 (34-50) | 40 (33-50) |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Women | 1037 (36.2) | 1012 (33.9) | 2096 (36.4) | 1890 (36.0) | 67 (29.1) | 151 (35.0) | 813 (38.0) | 625 (38.2) |

| Men | 1828 (63.8) | 1975 (66.1) | 3662 (63.6) | 3362 (64.0) | 163 (70.9) | 281 (65.0) | 1325 (62.0) | 1010 (61.8) |

| Urban location of residenceb | 2560/2848 (89.9) | 2617/2952 (88.7) | 5056/5739 (88.1) | 4479/5236 (85.5) | 202/229 (88.2) | 348/430 (80.9) | 1848/2136 (86.5) | 1415/1633 (86.7) |

| Neighborhood income quintileb | ||||||||

| 1 (lowest) | 1120/2845 (39.4) | 1420/2948 (48.2) | 2173/5723 (38.0) | 2160/5229 (41.3) | 90/228 (39.5) | 210/430 (48.8) | 743/2132 (34.8) | 556/1633 (34.0) |

| 2 | 677/2845 (23.8) | 633/2948 (21.5) | 1395/5723 (24.4) | 1154/5229 (22.1) | 55/228 (24.1) | 70/430 (16.3) | 521/2132 (24.4) | 374/1633 (22.9) |

| 3 | 456/2845 (16.0) | 395/2948 (13.4) | 992/5723 (17.3) | 837/5229 (16.0) | 34/228 (14.9) | 67/430 (15.6) | 381/2132 (17.9) | 304/1633 (18.6) |

| 4 | 370/2845 (13.0) | 301/2948 (10.2) | 703/5723 (12.3) | 604/5229 (11.6) | 27/228 (11.8) | 51/430 (11.9) | 268/2132 (12.6) | 233/1633 (14.3) |

| 5 (highest) | 222/2845 (7.8) | 199/2948 (6.8) | 460/5723 (8.0) | 474/5229 (9.1) | 22/228 (9.6) | 32/430 (7.4) | 219/2132 (10.3) | 166/1633 (10.2) |

| Concurrent benzodiazepine prescription | 333 (11.6) | 309 (10.3) | 762 (13.2) | 704 (13.4) | 32 (13.9) | 54 (12.5) | 297 (13.9) | 204 (12.5) |

| Health care encounter for alcohol use disorder (≤3 y) | 226 (7.9) | 336 (11.2) | 196 (3.4) | 269 (5.1) | 20 (8.7) | 71 (16.4) | 139 (6.5) | 135 (8.3) |

| ED visits or hospitalization for mental health or substance use disorders (≤3 y) | ||||||||

| Anxiety disorders | 105 (3.7) | 118 (4.0) | 120 (2.1) | 153 (2.9) | 10 (4.3) | 19 (4.4) | 68 (3.2) | 59 (3.6) |

| Deliberate self-harm | 125 (4.4) | 174 (5.8) | 48 (0.8) | 99 (1.9) | 8 (3.5) | 23 (5.3) | 39 (1.8) | 35 (2.1) |

| Mood disorders | 76 (2.7) | 95 (3.2) | 80 (1.4) | 90 (1.7) | 12 (5.2) | 27 (6.3) | 56 (2.6) | 44 (2.7) |

| Substance-related disorders | 481 (16.8) | 619 (20.7) | 222 (3.9) | 385 (7.3) | 45 (19.6) | 107 (24.8) | 197 (9.2) | 163 (10.0) |

| Trauma/stressor-related disorders | 103 (3.6) | 134 (4.5) | 63 (1.1) | 115 (2.2) | 12 (5.2) | 31 (7.2) | 53 (2.5) | 42 (2.6) |

| Other mental health disorders | 98 (3.4) | 102 (3.4) | 58 (1.0) | 122 (2.3) | 8 (3.5) | 29 (6.7) | 39 (1.8) | 32 (2.0) |

| ED visit or hospitalization | ||||||||

| For opioid-related overdose (≤1 y) | 136 (4.7) | 225 (7.5) | 54 (0.9) | 76 (1.4) | 11 (4.8) | 16 (3.7) | 19 (0.9) | 20 (1.2) |

| For stimulant-related harmful use/dependence (≤2 y) | 239 (8.3) | 315 (10.5) | 73 (1.3) | 145 (2.8) | 28 (12.2) | 57 (13.2) | 52 (2.4) | 57 (3.5) |

| For sedative/hypnotic-related harmful use/dependence (≤2 y) | 69 (2.4) | 79 (2.6) | 37 (0.6) | 62 (1.2) | ≤5 | 16 (3.7) | 21 (1.0) | 26 (1.6) |

| Diagnosis | ||||||||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 306 (10.7) | 297 (9.9) | 895 (15.5) | 658 (12.5) | 27 (11.7) | 39 (9.0) | 271 (12.7) | 193 (11.8) |

| Diabetes | 169 (5.9) | 148 (5.0) | 616 (10.7) | 454 (8.6) | 16 (7.0) | 31 (7.2) | 195 (9.1) | 162 (9.9) |

| HIV | 28 (1.0) | 29 (1.0) | 39 (0.7) | 27 (0.5) | 0 | ≤5 | ≤5 | 7 (0.4) |

| OAT daily dose, median (IQR), mgc | 75 (50-100) | 77 (50-100) | 70 (39-100) | 75 (44-105) | 12 (6-18) | 12 (8-18) | 10 (6-16) | 12 (6-18) |

| Health system utilization (≤1 y) | ||||||||

| No. of outpatient visits for OUD, median (IQR) | 24 (12-38) | 22 (12-39) | 14 (12-23) | 15 (12-28) | 16 (6-27) | 16 (7-32) | 14 (12-22) | 16 (12-29) |

| No. of non–OUD-related outpatient visits, median (IQR) | 5 (1-15) | 5 (1-16) | 4 (1-12) | 4 (1-13) | 4 (1-12) | 5 (1-14) | 5 (2-12) | 4 (1-11) |

| ≥1 ED visitd | 1394 (48.7) | 1581 (52.9) | 2021 (35.1) | 1965 (37.4) | 113 (49.1) | 240 (55.6) | 850 (39.8) | 633 (38.7) |

| ≥1 Inpatient hospitalizationd | 299 (10.4) | 388 (13.0) | 430 (7.5) | 450 (8.6) | 32 (13.9) | 58 (13.4) | 162 (7.6) | 136 (8.3) |

| History of alternate OAT use (≤2 y)e | 491 (17.1) | 505 (16.9) | 245 (4.3) | 290 (5.5) | 50 (21.7) | 105 (24.3) | 253 (11.8) | 202 (12.4) |

| Proportion of days covered in 28 d prior, mean (SD) | 0.93 (0.10) | 0.91 (0.12) | 0.91 (0.11) | 0.92 (0.10) | 0.92 (0.13) | 0.93 (0.12) | 0.87 (0.10) | 0.86 (0.10) |

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; OAT, opioid agonist therapy; OUD, opioid use disorder.

After weighting, all standardized differences were <0.10 (see eFigure 2 and eTable 4 in the Supplement). All statistics reported as No. (%) unless otherwise specified. Institutional policy requires suppression of counts <6.

For this category, individuals with missing data were removed so denominators may differ from values shown for the No. of individuals.

Reported as milligrams of methadone and milligrams of buprenorphine/naloxone, as appropriate.

All ED visits and inpatient hospitalizations were included, regardless of diagnosis.

Indicates prior buprenorphine/naloxone use among individuals in the methadone cohorts and prior methadone use among individuals in the buprenorphine/naloxone cohorts.

Individuals Receiving Daily Dispensed OAT Prior to the COVID-19 Pandemic

Among methadone-treated individuals previously receiving daily dispensed OAT, transitioning to take-home doses was significantly associated with a lower risk of opioid-related overdose (6.9% vs 9.5%/person-year; weighted hazard ratio [HR], 0.73 [95% CI, 0.56-0.96]), OAT discontinuation (51.0% vs 63.6%/person-year; weighted HR, 0.80 [95% CI, 0.72-0.90]), and treatment interruption (19.0% vs 23.9%/person-year; weighted HR, 0.80 [95% CI, 0.67-0.95]) compared with individuals who had no change in take-home dose (Figure 3, Table 2). There was no significant association between initiating take-home doses and risk of all-cause death (1.5% vs 1.3%/person-year; weighted HR, 1.16 [95% CI, 0.62-2.16]) or opioid-related death (0.6% vs 0.5%/person-year; weighted HR, 1.26 [95% CI, 0.48-3.33]).

Figure 3. Six-Month Outcomes Among People Treated With Opioid Agonist Therapy Prior to the COVID-19 Pandemic, Weighted on Propensity Score.

Hazard ratios and accompanying 95% CIs are presented for the crude, unweighted analysis, and after propensity-score weighting (data markers indicate weighted analysis).

aSome outcomes are not reported in buprenorphine/naloxone cohorts due to small event rates preventing model fit.

Table 2. Six-Month Outcome Rates Among People Treated With Methadone and Buprenorphine/Naloxone Prior to the COVID-19 Pandemic.

| Outcome | No. of individuals (weighted % per person-year)a | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methadone cohorts | Buprenorphine/naloxone cohorts | |||||||

| Daily dispensed cohort | 5-6 Take-home dose cohort | Daily dispensed cohort | 5-6 Take-home dose cohort | |||||

| Increased | No change | Increased | No change | Increased | No change | Increased | No change | |

| Total cohort size | 2865 | 2987 | 5758 | 5252 | 230 | 432 | 2138 | 1635 |

| Opioid overdose | 87 (6.9) | 150 (9.5) | 35 (1.4) | 51 (1.8) | 9 (6.5) | 8 (3.5) | 17 (1.7) | 12 (1.4) |

| Discontinuation of therapy | 574 (51.0) | 806 (63.6) | 370 (14.1) | 456 (19.6) | 74 (85.1) | 151 (93.2) | 255 (26.0) | 230 (30.8) |

| Interruption in therapy | 215 (19.0) | 332 (23.9) | 133 (5.1) | 165 (7.4) | 25 (25.3) | 54 (29.3) | 93 (9.5) | 101 (12.9) |

| All-cause mortality | 20 (1.5) | 21 (1.3) | 27 (0.8) | 28 (1.1) | ≤5b | ≤5b | 8 (0.8) | 7 (0.8) |

| Opioid-related death | 9 (0.6) | 8 (0.5) | ≤5b | 9 (0.3) | ≤5b | ≤5b | ≤5b | ≤5b |

| COVID-19 diagnosis | ≤5b | ≤5b | ≤5b | ≤5b | 0 | ≤5b | 6 (0.5) | ≤5b |

Weighted by inverse probability of treatment weights.

Institutional policy requires suppression of counts less than 6.

Among buprenorphine/naloxone-treated individuals receiving daily dispensed OAT, initiating take-home doses was not significantly associated with opioid overdose risk (6.5% vs 3.5%/person-year; weighted HR, 1.86 [95% CI, 0.70-4.92]), treatment discontinuation (85.1% vs 93.2%/person-year; weighted HR, 0.91 [95% CI, 0.68-1.22]), or interruption in therapy (25.3% vs 29.3%/person-year; weighted HR, 0.86 [95% CI, 0.52-1.41]) compared with individuals who received no increase in take-home doses (Figure 3). The small number of deaths in this cohort (≤5) precluded analysis of all-cause or opioid-related mortality.

Individuals Receiving Weekly Dispensed OAT Prior to the COVID-19 Pandemic

Among methadone-treated individuals previously receiving weekly dispensed OAT, extending to 13 or more take-home doses was significantly associated with a lower risk of OAT discontinuation (14.1% vs 19.6%/person-year; weighted HR, 0.72 [95% CI, 0.62-0.84]), and interruption in therapy (5.1% vs 7.4% per person-year; weighted HR, 0.69 [95% CI, 0.53-0.90]) compared with individuals remaining on weekly dispensed OAT (Figure 3, Table 2). No statistically significant association was observed between extended take-home doses and the risk of opioid-related overdose (1.4% vs 1.8%/person-year; weighted HR, 0.80 [95% CI, 0.50-1.28]), all-cause mortality (1.3% vs 0.8%/person-year; weighted HR, 0.74 [95% CI, 0.43-1.27]) and opioid-related death (≤5 vs 0.3%/person-year; weighted HR, 0.48 [95% CI, 0.16-1.45]) in this population.

Among individuals previously receiving weekly dispensed buprenorphine/naloxone, extended take-home doses were not significantly associated with a change in risk of opioid overdose (1.7% vs 1.4%/person-year; weighted HR, 1.23 [95% CI, 0.58-2.63]), discontinuation of therapy (26.0% vs 30.8%/person-year; weighted HR, 0.85 [95% CI, 0.70-1.01]), or all-cause mortality (0.8% vs 0.8%/person-year; weighted HR, 1.01 [95% CI, 0.36-2.81]), but were significantly associated with a lower risk of interruption in therapy (9.5% vs 12.9%/person-year; weighted HR, 0.74 [95% CI, 0.56-0.99]) compared with individuals who remained on weekly dispensed OAT (Figure 3). The small number of opioid-related deaths (≤5) in this cohort precluded analysis of this outcome.

Sensitivity Analyses

There was considerable variation in the proportion of patients receiving extended take-home doses among physicians in all cohorts (eFigure 3 in the Supplement). In the analyses stratified by the proportion of prescribers’ patients who were exposed, results among methadone recipients were consistent with the main findings for each stratum, although the only comparisons that remained statistically significant in weighted models were for treatment discontinuation and interruption outcomes in some strata (eTable 5 in the Supplement). Among buprenorphine/naloxone recipients, models could not be fit among physicians with a low proportion of their patients receiving extended take-home doses due to small event rates. However, results among physicians with a high proportion of their patients exposed were similar to the main findings. There was also wide variation in practice size among OAT prescribers in the cohorts, ranging from 5 or less to 1105 patients receiving OAT. In analyses stratified by practice size, results within each cohort were consistent with the main findings, although many comparisons were no longer statistically significant due to smaller cohort sizes within each practice size category (eTable 6 in the Supplement).

In the within-person analysis, buprenorphine/naloxone recipients transitioning from weekly take-home doses to extended doses had a small but statistically significant increase in the prevalence of nonfatal opioid overdose in the 180 days following the index date compared with the same period prior to the index date. No statistically significant difference was observed among remaining groups (eTable 7 in the Supplement). However, these findings were based on very low event rates, and overdose rates in the subgroup of individuals who were dispensed weekly take-home doses of buprenorphine/naloxone were the lowest of any group studied; therefore, this finding should be interpreted cautiously. In the analysis of overdose timing during follow-up, overdoses were found to be more common while on treatment with OAT (eTable 8 in the Supplement). For example, among individuals receiving daily dispensed methadone prior to the pandemic who experienced an opioid overdose in the first 6 months of follow-up, 77.0% (67 of 87) of those who started take-home doses and 69.3% (104 of 150) of those maintained on daily dispensed treatment experienced an overdose while still on treatment.

Discussion

In this population-based study of individuals receiving OAT upon the enactment of the COVID-19-related state of emergency in Ontario, Canada, some subsets of patients who were transitioned to take-home doses or who received extended take-home doses in alignment with pandemic-related clinical guidance had lower risks of treatment interruption or discontinuation, and they had a similar or lower risk of opioid overdose in the subsequent 6 months compared with individuals whose take-home doses remained unchanged. These findings were consistent among methadone recipients regardless of previous take-home dose level. Among those prescribed buprenorphine/naloxone, new or extended take-home doses were not associated with any outcomes, with the exception of a significant reduction in the risk of treatment interruption among individuals transitioning from weekly to extended take-home doses.

A key finding of this study was that physician decision-making to expand access to take-home doses among people who would not historically have been eligible during the pandemic supported ongoing retention in OAT without being significantly associated with an increased risk of overdose.13 Prior to the pandemic, Canadian national guidelines limited take-home doses of OAT to patients who met strict criteria,2 and although provincial standards varied slightly, eligibility for take-home doses was predicated on perceived social stability and sustained abstinence from all substance use.2 The revised pandemic guidance recommended de-emphasizing abstinence and contingency management. Patients were considered unsuitable for take-home doses if they had recently experienced an overdose, had an unstable psychiatric comorbidity, or were using illicit substances in ways considered high risk.13 It appears that these criteria were applied by many physicians when selecting OAT patients for increased take-home doses during the pandemic period, as the crude baseline comparisons indicated that those whose take-home dose levels were not changed tended to have higher rates of mental health diagnoses and health care contact related to alcohol use disorders. However, because physicians in Ontario were not mandated to follow this guidance, there was considerable variability in its uptake among OAT prescribers in the first month of the pandemic. Despite this variation in practice, the consistency of the findings stratified by the proportion of prescribers’ patients receiving extended take-home doses suggest that physicians in this study were able to successfully identify patients at low risk of overdose to receive new or extended take-home doses. While reassuring, inconsistent application of the COVID-19 OAT guidance may have prevented access to extended take-home doses among otherwise eligible patients, a practice that was associated in this study with sustained treatment and no increased risk of overdose in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Similar to Ontario, the COVID-19 pandemic led to changes in OAT prescribing guidance in other jurisdictions, with recommendations consistently emphasizing the use of telemedicine and provision of longer take-home doses.12,16,17 In the United States, although OAT is delivered slightly differently than in Canada, with more centralized prescribing and distribution through large opioid treatment programs,10 the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s (SAMHSA) guidelines for take-home doses of methadone were historically similar to those in Canada.2,9 In March 2020, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, SAMHSA relaxed these guidelines in a manner similar to the Ontario guidance, recommending up to 28 days of take-home doses among stable patients and up to 14 days among less stable patients.12 Preliminary evaluations of this change in small samples in the US are consistent with the findings of this study, suggesting shifts toward longer take-home doses in some but not all opioid treatment programs,18 and also suggesting that these changes were not associated with worse treatment outcomes.19 Therefore, because flexibility in take-home doses of OAT has been shown to be strongly valued by patients and associated with improvements in quality of life, ability to maintain employment, and treatment retention,8,20 these findings have important implications for national regulators as they consider extending or permanently implementing more flexible provision of OAT.21

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the clinical decision to provide patients with new or increased take-home doses is complex and can be related to sociodemographic and structural characteristics that cannot be captured in administrative data. Therefore, residual confounding of this analysis is possible.

Second, overdoses that are treated in the community and are not transferred to a hospital setting could not be captured in the data. Therefore, the findings underestimate the overall opioid overdose rate in this population.

Third, low event rates for some of the primary and sensitivity analyses resulted in wide CIs or precluded analysis in some cohorts. However, the low rate of mortality overall and of opioid-related death is reassuring, and it aligns with evidence surrounding the benefits of OAT in this population.1,22,23

Fourth, adherence to dispensed therapy among individuals prescribed take-home doses of OAT was assumed, which could slightly overestimate treatment duration among these individuals if they discontinue therapy abruptly without completing their take-home doses. However, due to strict requirements for OAT prescription refills in Ontario, it is unlikely that this has a large influence on the findings.

Fifth, patients’ exposure to extended take-home doses was measured in the first month following the introduction of the guidance, and the analysis did not account for changes in OAT take-home dose frequency after the completion of the exposure window. Therefore, take-home dose dispensing patterns may have changed during follow-up without being accounted in the analysis.

Sixth, there were several limitations to the generalizability of the findings. To align with common OAT treatment patterns, the study populations were restricted to individuals with distinct patterns of take-home doses during the pandemic and did not include individuals with smaller increases in take-home doses during this period or those already receiving longer-duration take-home doses prior to the pandemic. This study was also conducted during the unique circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic, and although OAT clinics in Ontario have remained open throughout the pandemic, the findings cannot be completely disentangled from the context of changes in health services delivery and public health measures implemented during the pandemic. For example, availability of telemedicine services and reduced reliance on in-person visits may have also improved continuity of care overall. Furthermore, while OAT delivery is generally delivered through large clinics in both Canada and the US, Canada has more expansive access to treatment through smaller clinics and individual physicians (including primary care), with a median OAT patient volume of approximately 150 (range, ≤5 to 1105) in the cohorts in this study.10 As a result, the degree to which these findings would apply outside of a pandemic setting or to settings outside of Canada cannot be ascertained.

Conclusions

In Ontario, Canada, during the COVID-19 pandemic, dispensing of increased take-home doses of OAT was significantly associated with lower rates of treatment interruption and discontinuation among some subsets of patients receiving OAT, and there were no statistically significant increases in opioid-related overdoses over 6 months of follow-up. These findings may be susceptible to residual confounding and should be interpreted cautiously.

eTable 1. Descriptions of All Linked Administrative Databases Used in the Study

eFigure 1. Definition of Study Cohorts and Exposure Status: (A) Methadone-Treated Individuals; (B) Buprenorphine-Treated Individuals

eTable 1. Descriptions of All Linked Administrative Databases Used in the Study

eTable 2. Censoring Criteria for Discontinuation Outcome for Each Cohort

eTable 3. Covariate Definitions

eFigure 2. Absolute Standardized Differences Before and After Propensity Score Weighting

eFigure 3. Distribution of Prescribers of Opioid Agonist Therapy (OAT) by Degree of Implementation of COVID OAT Guidance in Ontario

eTable 4. Weighted Characteristics for Each Cohort After Propensity Score Weighting

eTable 5. Six-Month Outcomes Among People Treated With OAT, Stratified on Degree of Physician Implementation of COVID-19 Guidance

eTable 6. Six-Month Outcomes Among People Treated With OAT, Stratified on Size of Physician Practice

eTable 7. Results of Within-Person Analysis of Nonfatal Opioid Overdoses

eTable 8. Distribution of Opioid Overdoses During Follow-up by Treatment Retention

eReferences.

References

- 1.Sordo L, Barrio G, Bravo MJ, et al. Mortality risk during and after opioid substitution treatment. BMJ. 2017;357:j1550. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j1550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bruneau J, Ahamad K, Goyer ME, et al. Management of opioid use disorders. CMAJ. 2018;190(9):E247-E257. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.170958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Proctor SL, Copeland AL, Kopak AM, Herschman PL, Polukhina N. A naturalistic comparison of the effectiveness of methadone and two sublingual formulations of buprenorphine on maintenance treatment outcomes. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;22(5):424-433. doi: 10.1037/a0037550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bell J, Strang J. Medication treatment of opioid use disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2020;87(1):82-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yarborough BJ, Stumbo SP, McCarty D, Mertens J, Weisner C, Green CA. Methadone, buprenorphine and preferences for opioid agonist treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;160:112-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams AR, Nunes EV, Bisaga A, et al. Developing an opioid use disorder treatment cascade. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2018;91:57-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Timko C, Schultz NR, Cucciare MA, Vittorio L, Garrison-Diehn C. Retention in medication-assisted treatment for opiate dependence. J Addict Dis. 2016;35(1):22-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frank D, Mateu-Gelabert P, Perlman DC, Walters SM, Curran L, Guarino H. “It’s like ‘liquid handcuffs”: the effects of take-home dosing policies on methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) patients’ lives. Harm Reduct J. 2021;18(1):88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . Federal guidelines for opioid treatment programs. Published 2015. Accessed January 11, 2022. https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/d7/priv/pep15-fedguideotp.pdf

- 10.Priest KC, Gorfinkel L, Klimas J, Jones AA, Fairbairn N, McCarty D. Comparing Canadian and United States opioid agonist therapy policies. Int J Drug Policy. 2019;74:257-265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stone AC, Carroll JJ, Rich JD, Green TC. One year of methadone maintenance treatment in a fentanyl endemic area. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2020;115:108031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . Opioid treatment program (OTP) guidance. Published 2020. Accessed January 11, 2022. https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/otp-guidance-20200316.pdf

- 13.Centre for Addiction and Mental Health . COVID-19 Opioid Agonist Treatment Guidance. Published 2020. Updated August 2021. Accessed October 20, 2021. https://www.camh.ca//-/media/files/covid-19-modifications-to-opioid-agonist-treatment-delivery-pdf.pdf?la=en&hash=261C3637119447097629A014996C3C422AD5DB05

- 14.Personal Health Information Protection Act, S.O. 2004, c. 3, Sched. A, §45 (2004).

- 15.Mamdani M, Sykora K, Li P, et al. Reader’s guide to critical appraisal of cohort studies: 2. assessing potential for confounding. BMJ. 2005;330(7497):960-962. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7497.960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nunes EV, Levin FR, Reilly MP, El-Bassel N. Medication treatment for opioid use disorder in the age of COVID-19. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2021;122:108196. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2020.108196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.British Columbia Centre on Substance Use . Risk mitigation in the context of dual public health emergencies. Published 2020. Accessed January 11, 2022. https://www.bccsu.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Risk-Mitigation-in-the-Context-of-Dual-Public-Health-Emergencies-v1.6.pdf

- 18.Levander XA, Pytell JD, Stoller KB, Korthuis PT, Chander G. COVID-19-related policy changes for methadone take-home dosing. Subst Abus. 2021;1-7. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2021.1986768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amram O, Amiri S, Panwala V, Lutz R, Joudrey PJ, Socias E. The impact of relaxation of methadone take-home protocols on treatment outcomes in the COVID-19 era. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2021;47(6):722-729. doi: 10.1080/00952990.2021.1979991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levander XA, Hoffman KA, McIlveen JW, McCarty D, Terashima JP, Korthuis PT. Rural opioid treatment program patient perspectives on take-home methadone policy changes during COVID-19. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2021;16(1):72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.SAMHSA extends the methadone take-home flexibility for one year while working toward a permanent solution [press release]. November 18, 2021. Accessed January 11, 2022. https://www.samhsa.gov/newsroom/press-announcements/202111181000#:~:text=The%20Substance%20Abuse%20and%20Mental,COVID%2D19%20Public%20Health%20Emergency

- 22.Pearce LA, Min JE, Piske M, et al. Opioid agonist treatment and risk of mortality during opioid overdose public health emergency. BMJ. 2020;368:m772. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hickman M, Steer C, Tilling K, et al. The impact of buprenorphine and methadone on mortality. Addiction. 2018;113(8):1461-1476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Descriptions of All Linked Administrative Databases Used in the Study

eFigure 1. Definition of Study Cohorts and Exposure Status: (A) Methadone-Treated Individuals; (B) Buprenorphine-Treated Individuals

eTable 1. Descriptions of All Linked Administrative Databases Used in the Study

eTable 2. Censoring Criteria for Discontinuation Outcome for Each Cohort

eTable 3. Covariate Definitions

eFigure 2. Absolute Standardized Differences Before and After Propensity Score Weighting

eFigure 3. Distribution of Prescribers of Opioid Agonist Therapy (OAT) by Degree of Implementation of COVID OAT Guidance in Ontario

eTable 4. Weighted Characteristics for Each Cohort After Propensity Score Weighting

eTable 5. Six-Month Outcomes Among People Treated With OAT, Stratified on Degree of Physician Implementation of COVID-19 Guidance

eTable 6. Six-Month Outcomes Among People Treated With OAT, Stratified on Size of Physician Practice

eTable 7. Results of Within-Person Analysis of Nonfatal Opioid Overdoses

eTable 8. Distribution of Opioid Overdoses During Follow-up by Treatment Retention

eReferences.