Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Uterine fibroids are common in premenopausal women, yet comparative effectiveness research on uterine fibroid treatments is rare.

OBJECTIVE:

The purpose of this study was to design and establish a uterine fibroid registry based in the United States to provide comparative effectiveness data regarding uterine fibroid treatment.

STUDY DESIGN:

We report here the design and initial recruitment for the Comparing Options for Management: Patient-centered REsults for Uterine Fibroids (COMPARE-UF) registry (Clinicaltrials.gov, NCT02260752), funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality in collaboration with the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. COMPARE-UF was designed to help answer critical questions about treatment options for women with symptomatic uterine fibroids. Women who undergo a procedure for uterine fibroids (hysterectomy, myomectomy [abdominal, hysteroscopic, vaginal, and laparoscopic/robotic], endometrial ablation, radiofrequency fibroid ablation, uterine artery embolization, magnetic resonance–guided focused ultrasound, or progestin-releasing intrauterine device insertion) at 1 of the COMPARE-UF sites are invited to participate in a prospective registry with 3 years follow up for postprocedural outcomes. Enrolled participants provide annual follow-up evaluation through an online portal or through traditional phone contact. A central data abstraction center provides information obtained from imaging, operative or procedural notes, and pathology reports. Women with uterine fibroids and other stakeholders are a key part of the COMPARE-UF registry and participate at all points from study design to dissemination of results.

RESULTS:

We built a network of 9 clinical sites across the United States with expertise in the care of women with uterine fibroids to capture geographic, racial, ethnic, and procedural diversity. Of the initial 2031 women who were enrolled in COMPARE-UF, 42% are self-identified as black or African American, and 40% are ≤40 years old, with 16% of participants <35 years old. Women who undergo myomectomy comprise the largest treatment group at 46% of all procedures, with laparoscopic or robotic myomectomy comprising the largest subset of myomectomies at 19% of all procedures. Hysterectomy is the second most common treatment within the registry at 38%.

CONCLUSION:

In response to priorities that were identified by our patient stakeholders, the initial aims within COMPARE-UF will address how different procedures that are used to treat uterine fibroids compare in terms of long-lasting symptom relief, potential for recurrence, medical complications, improvement in quality of life and sexual function, age at menopause, and fertility and pregnancy outcomes. COMPARE-UF will generate evidence on the comparative effectiveness of different procedural options for uterine fibroids and help patients and their caregivers make informed decisions that best meet an individual patient’s short- and long-term preferences. Building on this infrastructure, the COMPARE-UF team of investigators and stakeholders, including patients, collaborate to identify future priorities for expanding the registry, such as assessing the efficacy of medical therapies for uterine fibroids. COMPARE-UF results will be disseminated directly to patients, providers, and other stakeholders by traditional academic pathways and by innovative methods that include a variety of social media platforms. Given demographic differences among women who undergo different uterine fibroid treatments, the assessment of comparative effectiveness for this disease through clinical trials will remain difficult. Therefore, this registry provides optimized evidence to help patients and their providers better understand the pros and cons of different treatment options so that they can make more informed decisions.

Keywords: comparative effectiveness research, uterine fibroid, uterine leiomyoma

Uterine leiomyomas (fibroid; UFs) are a leading cause of morbidity among premenopausal women. UFs also represent a significant health disparity with greater frequency and severity in women of African descent.1,2 By age 50 years, almost 70% of white women and >80% of African American women have had at least 1 UF detectable by imaging.3,4 Although many UFs are asymptomatic, a substantial proportion cause symptoms, most commonly heavy menstrual bleeding and/or pelvic pressure and pain, with a peak incidence for symptoms between the ages of 35 and 45 years.5 Not surprisingly, such symptoms are associated with impairment in health-related quality of life (HR-QOL),6,7 as measured by both global and disease-specific validated scales. Additionally, UFs are by far the most common cause of hospitalization for benign gynecologic conditions in the United States, with hysterectomy accounting for approximately 75% of all procedures.8,9

There is a paucity of high-quality evidence regarding UF therapies to help inform women who are facing treatment. Reports produced for the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) in 2002 and 2007 found almost no evidence on comparative effectiveness (CE) of UF treatment options.5,10 A recently released updated AHRQ systematic review on UF reached similar conclusions.11

There are distinct clinical challenges in obtaining high-quality CE data for UFs. The physical extent of disease of UF is more substantial and heterogeneous than in many other diseases. Symptomatic uterine fibroids frequently range from 1–20 cm in diameter and produce a volume difference of >1000-fold. Thus, clinically significant fibroids can weigh anywhere from a few milligrams to several kilograms. The number of fibroids in a uterus can vary from 1 to >100; the position of UF within the uterus varies widely. Similarly, symptomatic disease can vary substantially by its age of onset, symptom profile, and patient race and ethnicity. The same symptoms that drive 1 woman to surgery will be treated expectantly by another. Finally, patient demographics vary substantially across treatment type. Thus, individualizing information for a specific woman is very complex. Adding to this complexity is practice variability among different healthcare providers with resultant differences in treatment plans.

Recognizing the profound evidence gap that is specific to UF treatment, AHRQ and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) agreed in 2013 to collaborate on UF research. The resultant registry, Comparing Options for Management: PAtient-centered REsults for Uterine Fibroids (COMPARE-UF), is a jointly supported collaboration. It is designed to generate evidence about the CE and safety of different management options for UF to help patients, clinicians, and other stakeholders make informed decisions to best meet an individual patient’s short- and long-term preferences.

Materials and Methods

Overview and objectives

The COMPARE-UF registry (NCT02260752, clinicaltrials.gov) enrolls and follows women who elect procedural therapy for symptomatic fibroids. Neither the women nor their healthcare providers have limitations on their choice of therapy within the study. Baseline, postprocedural, and annual follow-up data are self-reported. Centralized data abstraction takes place for the baseline imaging report, any operative or procedural note, and pathology reports, where relevant. The registry also has a dedicated statistician, who will monitor ongoing recruitment and data analysis issues.

COMPARE-UF has 3 initial CE objectives for procedural interventions: (1) to compare safety and efficacy in terms of durability of symptom relief and the need for additional treatment for UF, (2) to compare the impact of UF procedures on ovarian function (including ovarian reserve and time to menopause), ability to become pregnant, and maternal and neonatal outcomes of pregnancy, and (3) to compare the effectiveness of UF treatment options within key demographic subpopulations.

Registry organization

The registry is funded by AHRQ, in collaboration with PCORI, with administrative and scientific oversight provided by AHRQ. The Duke Clinical Research Institute serves as the Research Data and Coordinating Center. Initially, a Registry Steering Committee oversaw all governance and scientific aspects of COMPARE-UF and advised the Executive Committee on issues including protocols, recruitment and retention, and strategies for sustainability. The Registry Steering Committee is comprised of the Principal Investigators of the Research Data and Coordinating Center, the participating Clinical Centers, and the Center for Medical Technology Policy, which coordinates all stakeholder activities, project officers from AHRQ and PCORI, a patient stakeholder, and 2 external advisors.

At the start of funding year 3, the Executive Committee was given final governance authority, and the Registry Steering Committee shifted to an advisory role. The Executive Committee is comprised of the Principal Investigator and a coinvestigator of the Registry and Data Coordinating Center plus a representative clinical site Principal Investigator. Finally, much work of the registry is done within key committees, which includes protocol, publications, bio-specimens, and conflict of interest committees.

Stakeholder advisory group

The Stakeholder Advisory Group is an independent body comprised of approximately 30 members, which includes patient and consumer representatives, clinicians representing relevant professional societies, representatives of Federal agencies that are involved in women’s health, healthcare insurers/payers, health system administrators, and manufacturers of devices and pharmaceuticals for the treatment of UF. The diverse perspectives of these advisors are important to ensure that COMPARE-UF is relevant to the broader fibroid and healthcare community. In addition to providing input on study design and protocol development (thereby, helping to ensure that the outcomes selected, population being studied, and comparators selected are patient-centered), this group advises on strategies and mechanisms to reach vulnerable and underrepresented racial and ethnic groups and effective dissemination and translation of study findings to both clinicians and the lay community. Stakeholders are and will continue to be engaged through annual face-to-face meetings, quarterly web conferences, online surveys at critical junctures for decision-making, and targeted key informant interviews with a subset of relevant experts both before and after meeting.

Patient engagement

Patient engagement is essential to the design and conduct of COMPARE-UF. Patients have contributed to the prioritization of research questions and selection of outcomes. Continuing this philosophy, the COMPARE-UF website (http://www.compare-uf.org/) keeps participants updated about the progress and results of COMPARE-UF. An additional online portal provides a platform through which patients can enter follow-up information directly. The patient reporting of outcomes is not only efficient, in terms of minimizing resources, but also is a natural approach to collecting outcomes that are patient centered.

Study population, screening, and enrollment

Investigators recruit consecutive eligible patients who are scheduled to undergo procedural interventions for UF at a COMPARE-UF Clinical Center or affiliated site. Initial Institutional Review Board approval was received at Duke University on October 30, 2014, and the protocol was then approved by each participating institutions’ Institutional Review Board. Recruitment for COMPARE-UF began in November 2015. Eligible women are at least 18 years old, premenopausal, defined as having had at least 1 menstrual period in the preceding year, and have documented uterine fibroids. Data are collected on the following interventions: (1) hysterectomy, (2) myomectomy (abdominal, hysteroscopic, vaginal and laparoscopic/robotic), (3) endometrial ablation, (4) radiofrequency fibroid ablation, (5) uterine artery embolization, and (6) magnetic resonance guided focused ultrasound (Table 1). In early 2017, some centers observed that progestin-releasing intrauterine devices were being used increasingly at their institutions as a UF treatment instead of endometrial ablation. Therefore, in September of 2017, therapeutic use intrauterine devices were added to the list of COMPARE-UF interventions (Table 1). Previous fibroid treatment is not an exclusion criterion. Full enrollment criteria are detailed in Table 1. Depending on local regulatory approvals, eligible women may be consented and complete the baseline survey in person, via telephone, or through the electronic COMPARE-UF online portal.

TABLE 1.

Key enrollment criteria for Comparing Options for Management: Patient-centered Results for Uterine Fibroids (COMPARE-UF)

| Inclusion criteria: |

| 1. Age of 18–54 years |

| 2. Premenopausal, defined as having had a menstrual period within the previous 3 months |

| 3. Documented uterine fibroids by: |

| A. An ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging, or pathology report within the last 12 months that documents at minimum: |

| a. Presence of at least 1 uterine fibroid |

| b. The 3 uterine dimensions |

| OR |

| B. Medical records documentation such as: |

| a. International Classification of Diseases-10 or Current Procedural Terminology codes that indicate the presence of fibroids |

| b. Documentation of fibroid, leiomyoma, leiomyomata on current problem list, procedure schedule, or other relevant medical or administrative record |

| c. Documentation on the imaging report of “fibroids observed” or similar language |

| 4. Able to give informed consent |

| 5. English-speaking |

| 6. Undergoing a relevant uterine fibroid procedure: |

| A. Hysterectomy |

| B. Abdominal, hysteroscopic, or laparoscopic/robotic myomectomy |

| C. Endometrial ablation |

| D. Radiofrequency fibroid ablation |

| E. Uterine artery embolization |

| F. Magnetic resonance guided focused ultrasound |

| G. Progestin-releasing intrauterine device insertion |

| Exclusion Criteria: |

| 1. Previous hysterectomy |

| 2. Suspected or known cancer at any pelvic site (eg, uterus, cervix, ovary, fallopian tube) |

To monitor data quality and enrollment trends, ensure generalizability of registry findings, and facilitate statistical procedures to address potential biases, site coordinators also collect deidentified aggregate data on all eligible subjects, which included age, race, insurance status, 3-digit zip code, procedure type, and procedure date within local institutional review board approval and guidelines.

Data collection and follow up

Table 2 provides an overview of the data collection for enrolled participants. We will collect patient-reported outcomes annually for a minimum of 24 months after the index treatment with a goal of extending follow up indefinitely, if additional funds are obtained. All data are entered into a secure, password-protected web-based data portal. Enrolled patients receive electronic reminders to complete the follow-up survey via the portal, unless they expressed preference for a telephone interview or paper forms. Trained interviewers from the Duke Clinical Research Institute can complete surveys if requested by patients. If a patient appears to be lost to follow up, the local Clinical Center is asked to try to follow up with the patients and to review local medical records to identify additional treatments or adverse events since last contact.

TABLE 2.

Comparing Options for Management: Patient-centered Results for Uterine Fibroids (COMPARE-UF) data collection summary

| Interval | Data source | Domains |

|---|---|---|

| Baselinea | Patient | Demographic information |

| Medical history | ||

| Uterine fibroid procedure history | ||

| Current medical therapies | ||

| Menstrual and fibroid history | ||

| Reproductive history | ||

| Health-related quality of life scales | ||

| Uterine fibroid symptom—quality of life (fibroid-specific outcomes) | ||

| Euro quality of life-5D (general health outcomes) | ||

| Patient health questionnaire-2 (depression) | ||

| Menopause rating scale | ||

| Imaging | Radiology report (within 12 mo before procedure) | Date of imaging |

| Central data abstraction | Type of imaging | |

| Fibroid description/measurement | ||

| Uterine description/measurement | ||

| Ovaries description | ||

| Suspicious findings | ||

| Procedure | Operative note | Date of procedure |

| Pathology note | Discharge date | |

| Discharge summary | Type of procedure | |

| Central data | Primary surgeon | |

| Abstraction | Procedural details | |

| Complications | ||

| Procedural findings | ||

| Short-term follow-up evaluation (6–8 wk after procedure) | Patient | 4 Health-related quality of life scales |

| Complications | ||

| Rehospitalization | ||

| Return to work | ||

| Annual follow-up evaluation (date of consent as anchor) | Patient | 4 Health-related quality of life scales |

| Interim uterine fibroid procedures and therapies | ||

| Menopausal status | ||

| Pregnancy outcomes |

If medical and procedural history data are missing, the local site coordinator will complete with the data from medical record.

Because patient-centered outcomes are a key mandate for COMPARE-UF, validated measures of HR-QOL are collected at each time point (Table 2). Specific instruments include (1) the uterine fibroid symptom quality of life questionnaire, the validated disease-specific HR-QOL measure;7,12–15 (2) the EuroQOL 5D 5L, an instrument for general HR-QOL;16 (3) the Patient Health Questionnaire–2, a screen for clinical depression;17,18 and (4) the Menopause Rating Scale, a measure of climacteric symptoms.19,20

Outcomes

Short-term outcomes

Short-term patient-reported outcomes include the time from procedure to resumption of usual activities, work days missed after the procedure, and the 4 validated measures of HR-QOL. Assessed clinical outcomes include procedural complications (pain, bleeding, infection, wound complications, neuropathy) and postprocedural hospitalization (reoperation, bleeding, infection, and thromboembolic events). Additionally, the incidental diagnosis of cancer is assessed.

Annual follow up

At the annual posttreatment follow-up evaluation, we will assess the appearance of new fibroid symptoms, additional medical or procedural fibroid treatments, and new medical illnesses. Finally, key reproductive outcomes that include menopausal status, infertility, recurrent pregnancy loss, and pregnancy outcomes (conception, live birth, gestational age) will be assessed.

Assessment of ovarian reserve

Impairment of ovarian reserve is both a possible complication of fibroid therapies and an additional mechanism of symptom relief. Therefore, a subset of COMPARE-UF subjects is enrolled in a substudy to assess ovarian reserve. Serum samples for assay of anti-Müllerian hormone, which is a proxy measure of ovarian reserve, are collected at baseline and 1 year after treatment. This substudy is open to all women who are <45 years old. However, because fertility impairment and reproductive outcomes are of primary importance to women who elect uterine sparing therapies, the study statistician tracks enrollment by age and treatment type to optimize the power to address reproductive outcomes.

Statistical analyses

Initial analyses will examine clinical characteristics and demographics of patients who receive specific UF terventions. Subsequently, comparative outcomes will be assessed. Although hysterectomy will be the primary comparator for fibroid symptom relief, myomectomy will also be used because many women with UF desire uterine conservation and/or future pregnancy.

The goal of the registry is to address multiple hypotheses that have differing power and that depend on the characteristics of the women who are enrolled in the registry. Therefore, sample sizes are not based on the power for a single prespecified comparison. The projected sample sizes by March 2019 are approximately 1200 myomectomies, 1000 hysterectomies, 200 endometrial ablations, and 200 uterine artery embolizations. Although COMPARE-UF will continue to enroll patients beyond this point, the study will have good power for many important comparisons by this time. For example, we estimate >90% power for comparisons that use the uterine fibroid symptom quality of life questionnaire at 12 months for the 4 in-procedures listed earlier.15

Because COMPARE-UF is an observational registry, we use propensity score methods to adjust for confounding, particularly confounding by indication. Propensity score methods have been favored for separating the design phase, where adjustment occurs, from analysis of outcomes.21 The propensity score is a summary measure of the differences in baseline characteristics for patients who undergo different UF treatments. It can be used to create balance or comparability through matching, stratification, or inverse weighting.22 In general, COMPARE-UF will use inverse propensity weighting,23 although large differences in the treatment groups can create extreme weights that may indicate alternatives such as matching, trimming, or overlap weighting.24,25 These specific options for data analysis will be determined by the context of the specific comparison. Deidentified data collected on all eligible subjects will evaluate and adjust for differences between participants and those lost to follow up and will be used to adjust for any differences between participants and nonparticipants (nonresponse bias) by inverse weighting.26

Dissemination of study findings

Because COMPARE-UF’s mission patient-centered, it is essential that results be accessible, generalizable, and useful to diverse stakeholders. Thus, in addition to traditional peer-reviewed publications and presentations, we plan to collaborate with our Stakeholder Advisory Group, to identify nonacademic routes of dissemination that include newspapers, magazines, radio, television, websites of advocacy groups and social media, to partner with specialty societies to formulate evidence-based guidelines and quality metrics, or to reassess research priorities given the results of COMPARE-UF.

Long-term vision

The vision is that COMPARE-UF will provide a framework for many studies of uterine fibroids beyond the initial funding period. Given expertise on fibroids in high-volume Clinical Centers, this network provides the infrastructure for other projects that include postmarketing surveillance for new drugs and devices and genetic studies of UF.

Results

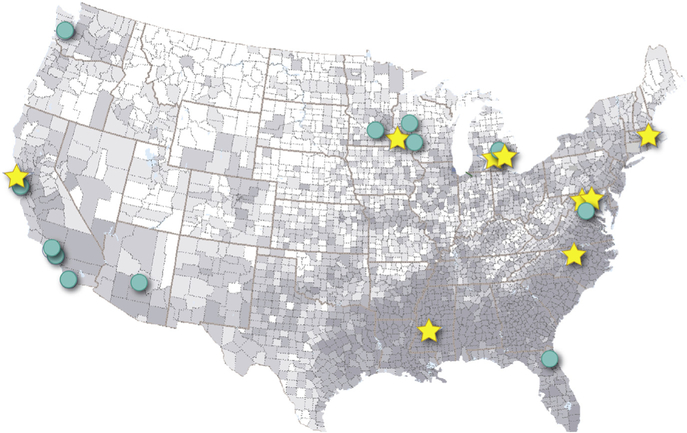

Nine Clinical Centers with expertise in UF care are collaborating institutions: Mayo Clinic Collaborative Network, University of California Fibroid Network, Henry Ford Health System, University of Mississippi Medical Center, the University of Michigan, University of North Carolina, Partners Healthcare/Harvard Medical School Collaboration, Inova Health Systems, and the Department of Defense Collaborative Sites (Table 3). These centers represent a mix of academic and community practice settings and were chosen, in part, to maximize geographic and demographic diversity of enrolled patients (Table 3). Both rural and urban populations are well represented, and most centers are affiliated with networks of community-based primary care. The Figure displays the location of core Clinical Centers and key collaborating affiliated subsites, along with the county-specific proportion of African American women among women aged 20–54 years by quintile (derived from 2012 US Census estimates).27 Five of the centers are located in counties in the highest quintile, with 2 of the others in the 4th quintile. Other racial/ethnic groups are well represented (Table 3). Initial COMPARE-UF recruitment began at 3 vanguard sites in November 2015 and will continue through at least March 2019. As of January 23, 2018, 2031 COMPARE-UF subjects have been enrolled.

TABLE 3.

Characteristics of the Comparing Options for Management: Patient-centered Results for Uterine Fibroids (COMPARE-UF) clinical centers and their affiliated recruiting sites

| Characteristic | COMPARE-UF clinical centers | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mayo Clinic (E.A Stewart, MD, PI) | University of California Fibroid Network (V. Jacoby, MD, MAS, PI) | Henry Ford Health System (G. Wegienka, PhD, PI) | University of Mississippi Medical Center (K. Wallace, PhD, PI) | University of Michigan (E.E. Marsh, MD, MSci, PI) | University of North Carolina (W.K. Nicholson, MD, MPH, MBA, PI) | Partners Healthcare/Harvard Medical School (R.M. Anchan, MD, PhD, PI) | Inova Health System (G.L. Maxwell, MD, PI) | Department of Defense (W.H. Catherino, MD, PhD, PI) | |

| Recruitment sites | Rochester and Mankato, MN; La Crosse and Eau Claire, WI; Phoenix, AZ; Jacksonville, FL | San Francisco, Los Angeles, San Diego, Davis, and Irvine, CA | Detroit, MI, and vicinity | Jackson, MS | Ann Arbor and Ypsilanti, MI, and vicinity | Chapel Hill, NC | Brigham and Women’s, Beth Israel, and Massachusetts General Hospitals Boston, MA | Alexandria and Fairfax, VA | Walter Reed, Madigan, and Tripler Army Medical Centers |

| Key patient populations | |||||||||

| African American women | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Other minoritiesa | AI, H | A, PI, H | H | H, A | A, H | A, H, PI | |||

| Obese women | X | X | X | ||||||

| Urban | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Rural | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Community-based care | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Key study infrastructure | |||||||||

| Electronic medical records | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Clinical Translational Science Award | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Biorepository | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Practice-based Research Network | X | X | |||||||

| Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute Clinical Data Research Network applicant | X | X | X | ||||||

| Specific less common procedures | |||||||||

| Uterine artery embolization | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Magnetic resonance guided focused ultrasound | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Radiofrequency ablation | X | ||||||||

American Indian, Alaskan Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian, Other Pacific Islander, Hispanic.

FIGURE. Clinical centers and affiliated sites map.

Comparing Options for Management: Patient-centered Results for Uterine Fibroids (COMPARE-UF) Clinical Centers (stars) and affiliated sites (circles) are overlaid on a map of the United States where the shading is a representation of the geographic racial diversity of African American women aged 20–54 years based on US county-based census data.27 Darker areas of the map have a greater proportion of African American women. Tripler Army Medical Center (Honolulu, HI) is not shown on this figure.

In contrast to nationwide statistics where hysterectomy predominates,8,9 the COMPARE-UF sites have increased enrollment for women seeking alternatives to hysterectomy (Table 4). Hysterectomy was elected by 38% of participants; myomectomies comprised 46% of all procedures; laparoscopic or robotic myomectomies were performed most frequently and accounted for 19% of all procedures (Table 4). The sites have also recruited younger women where 16% of participants are <35 years old, and 40% are <40 years old (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Comparing Options for Management: Patient-centered Results for Uterine Fibroids (COMPARE-UF) enrollment to date by procedure and age

| Procedure | Age, n | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18–24 Y | 25–29 Y | 30–34 Y | 35–40 Y | 41–45 Y | 46–50 Y | ≥51 Y | Unknown | |

| Hysterectomy (n=764; 38%) | 1 | 3 | 17 | 115 | 238 | 289 | 101 | 14 |

| Myomectomy-abdominal (n=280; 14%) | 3 | 16 | 80 | 99 | 50 | 28 | 4 | 5 |

| Myomectomy-laparoscopic/robotic (n=386; 19%) | 4 | 31 | 84 | 152 | 78 | 29 | 8 | 5 |

| Myomectomy-hysteroscopic (n=255; 13%) | 1 | 12 | 32 | 64 | 74 | 50 | 22 | 3 |

| Myomectomy-vaginal (n=7; <1%) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Laparoscopic radiofrequency ablation (n=12; <1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 0 |

| Endometrial ablation (n=146; 7%) | 0 | 0 | 2 | 22 | 54 | 52 | 16 | 5 |

| Uterine artery embolization (n=125; 6%) | 0 | 0 | 5 | 21 | 28 | 58 | 13 | 8 |

| Magnetic resonance—guided focused ultrasound (n=15; <1%) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 6 | 1 | 1 |

| Progestin-releasing intrauterine device (n=0; 0%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Similarly, despite comprising only 13% of the US population, African American women comprise 42% of enrollment in COMPARE-UF (Table 5). Similar or greater numbers of African American women elected each type of myomectomy and uterine artery embolization compared with white women (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Comparing Options for Management: Patient-centered Results for Uterine Fibroids (COMPARE-UF) enrollment to date by procedure and race

| Procedure | Race, n | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| African American | Asian | Native American | Native Hawaiian | White | Other or unknown | |

| Hysterectomy | 301 | 47 | 10 | 0 | 339 | 81 |

| Myomectomy | ||||||

| Abdominal | 134 | 23 | 1 | 1 | 83 | 43 |

| Laparoscopic/robotic | 151 | 38 | 6 | 2 | 141 | 53 |

| Hysteroscopic | 106 | 11 | 2 | 1 | 105 | 33 |

| Vaginal | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Laparoscopic radiofrequency ablation | 5 | 38 | 6 | 2 | 141 | 53 |

| Endometrial ablation | 56 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 76 | 11 |

| Uterine artery embolization | 89 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 28 | 9 |

| Magnetic resonance—guided focused ultrasound | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 3 |

| Progestin-releasing intrauterine device | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total enrollment by race (%) | 849 (42) | 129 (6) | 24 (1) | 4 (<1) | 792 (39) | 233 (11) |

The COMPARE-UF Protocol Committee formulated both baseline and follow-up questionnaires to meet the key objectives of the study (Supplementary Figures 1, 2, and 3). These instruments may be useful for other CE studies of fibroids tumors.

Comments

Comparing the safety and effectiveness of UF treatment options is a major research priority that reflects the substantial burden of UF shared by patients, providers, insurers, and society.10,11,28 It is especially important to gain CE data regarding alternatives to hysterectomy that have been understudied because alternatives are much less commonly performed than hysterectomy but are sought strongly by many women and especially African American women.1,8,9

Early recruitment data for COMPARE-UF suggest that this registry is poised to answer some of these key CE questions. The fact that more than one-half of the enrolled women underwent an alternative to hysterectomy provides a much needed source of data for the examination of the safety and efficacy of these uterine-sparing treatment options. Similarly, the fact that a sizable proportion of women are <40 years old suggests that, with long-term follow up, data on reproductive outcomes can be obtained as these women seek pregnancy.

Most importantly, the fact that African American women comprise >40% of enrollees suggests that data for this most significant subpopulation can be obtained and that potential differences in outcomes by race can be studied. In contrast to studies in which outcomes are assessed from government or insurance databases that lack detailed clinical data, COMPARE-UF can determine whether outcomes are similar in women with similar baseline symptoms or equivalent uterine anatomy.

There are a number of specific factors that contribute to uncertainty about optimal treatment choices for UF, including the diverse clinical presentation of UF, the limited utility of administrative data (ie, most women with fibroid tumors are not covered by Medicaid, a common administrative data source for other conditions29), lack of sufficient relevant clinical detail,30 and treatments that frequently are either off-label, (such as surgical procedures), or involve the use of devices that typically require less rigorous preapproval research compared with drugs.31–33 Race and ethnicity also play a role with black and Hispanic women more often undergo inpatient, as opposed to ambulatory, surgeries, and black women both having higher rates of myomectomies than other women and prioritizing uterine sparing options.1,34,35 Additionally, recruitment into randomized trials for UF or abnormal menstrual bleeding, which typically is the goal standard, has been historically difficult, especially in the United States.36–38

COMPARE-UF will address this knowledge gap by enrolling a large, nationally representative sample of patients who undergo procedures for UF. The registry collects detailed information on UF characteristics, symptoms, and quality of life before the procedure, which allows for robust adjustment of CE analyses. This infrastructure and methods will provide a basis for expansion into other therapeutic treatments. Diverse patient data from women across the United States are being compiled to provide patient-centered analyses for UF treatment. Given the huge burden imposed on women by UF, these results are urgently needed.

Supplementary Material

AJOG at a Glance.

Why was this study conducted?

Despite the clinical importance of uterine fibroids tumors, there is little comparative efficacy research to guide treatment decisions.

Key Findings

Both African American women and younger women are overrepresented in enrollment in the Comparing Options for Management: Patient-centered Results for Uterine Fibroids (COMPARE-UF) fibroid registry.

What does this add to what is known?

The Comparing Options for Management: Patient-centered Results for Uterine Fibroids (COMPARE-UF) registry is poised to answer key questions about the comparative efficacy of uterine fibroid treatment options for women in the United States.

Acknowledgments

Supported by grant number P50HS023418 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (E.R.M.).

E.A.S. reports personal fees from AbbVie, Allergan, Astellas Pharma, Bayer, Gynesonics, and Myovant related to uterine fibroids, GlaxoSmithKline related to adenomyosis, and Welltwigs related to infertility outside the submitted work and an issued patent “Methods and Compounds for Treatment of Abnormal Uterine Bleeding” 6440445; V.J. reports grants from Acessa Health, outside the submitted work; M.P.D. reports grants from AbbVie, Bayer and ObsEva outside the submitted work; E.E.M. reports grants and personal fees from Allergan and personal fees from AbbVie outside the submitted work; B.J.B. reports grants from HalioDx outside the submitted work; E.R.M. reports personal fees from Allergan and Bayer outside the submitted work. The remaining authors report no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Contributor Information

Elizabeth A. Stewart, Division of Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN.

Barbara L. Lytle, Duke Clinical Research Institute, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC.

Laine Thomas, Duke Clinical Research Institute, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC; Department of Biostatistics & Bioinformatics, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, NC.

Ganesa R Wegienka, Department of Public Health Sciences, Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, MI.

Vanessa Jacoby, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Sciences, University of California, San Francisco, CA.

Michael P. Diamond, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Augusta University, Augusta GA.

Wanda K. Nicholson, Center for Women's Health Research, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, UNC School of Medicine, Center for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention, UNC School of Public Health, Chapel Hill, NC.

Raymond M. Anchan, Division of Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, MA.

Sateria Venable, Fibroid Foundation, Bethesda, MD.

Kedra Wallace, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS.

Erica E. Marsh, Division of Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, MI.

George L. Maxwell, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Inova Fairfax Hospital, Falls Church, VA.

Bijan J. Borah, Division of Health Care Policy and Research, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN.

William H. Catherino, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, MA.

Evan R. Myers, Duke Clinical Research Institute, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC; Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, NC.

References

- 1.Stewart EA, Nicholson WK, Bradley L, Borah BJ. The burden of uterine fibroids for african-american women: results of a national survey. J Womens Health 2013;22:807–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stewart EA, Laughlin-Tommaso SK, Catherino WH, Lalitkumar S, Gupta D, Vollenhoven B. Uterine fibroids. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2016;2:16043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baird DD, Dunson DB, Hill MC, Cousins D, Schectman JM. High cumulative incidence of uterine leiomyoma in black and white women: ultrasound evidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003;188:100–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holdsworth-Carson SJ, Zaitseva M, Vollenhoven BJ, Rogers PA. Clonality of smooth muscle and fibroblast cell populations isolated from human fibroid and myometrial tissues. Molecular Hum Reprod 2014;20:250–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Myers ER, Barber MD, Gustilo-Ashby T, Couchman G, Matchar DB, McCrory DC. Management of uterine leiomyomata: what do we really know? Obstet Gynecol 2002;100:8–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams VS, Jones G, Mauskopf J, Spalding J, DuChane J. Uterine fibroids: a review of health-related quality of life assessment. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2006;15:818–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spies JB, Coyne K, Guaou Guaou N, Boyle D, Skyrnarz-Murphy K, Gonzalves SM. The UFS-QOL, a new disease-specific symptom and health-related quality of life questionnaire for leiomyomata. Obstet Gynecol 2002;99:290–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whiteman MK, Hillis SD, Jamieson DJ, et al. Inpatient hysterectomy surveillance in the United States, 2000–2004. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2008;198:34.e1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borah BJ, Laughlin-Tommaso SK, Myers ER, Yao X, Stewart EA. Association between patient characteristics and treatment procedure among patients with uterine leiomyomas. Obstet Gynecol 2016;127:67–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Viswanathan M, Hartmann K, McKoy N, et al. Management of uterine fibroids: an update of the evidence. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep) 2007:1–122. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hartmann KE, Fonnesbeck C, Surawicz T, et al. Management of uterine fibroids: comparative effectiveness review no. 195. AHRQ Publication No. 17(18)-EHC028-EF. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Ressearch and Quality; 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harding G, Coyne KS, Thompson CL, Spies JB. The responsiveness of the uterine fibroid symptom and health-related quality of life questionnaire (UFS-QOL). Health Qual Life Outcomes 2008;6:99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coyne KS, Margolis MK, Murphy J, Spies J. Validation of the UFS-QOL-hysterectomy questionnaire: modifying an existing measure for comparative effectiveness research. Value Health 2012;15:674–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coyne KS, Margolis MK, Bradley LD, Guido R, Maxwell GL, Spies JB. Further validation of the uterine fibroid symptom and quality-of-life que tionnaire. Value Health 2012;15:135–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spies JB, Bradley LD, Guido R, Maxwell GL, Levine BA, Coyne K. Outcomes from leiomyoma therapies: comparison with normal controls. Obstet Gynecol 2010;116:641–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res 2011;20:1727–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary care evaluation of mental disorders. Patient health questionnaire. JAMA 1999;282:1737–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care 2003;41: 1284–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heinemann K, Ruebig A, Potthoff P, et al. The Menopause Rating Scale (MRS) scale: a methodological review. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2004;2:45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zollner YF, Acquadro C, Schaefer M. Literature review of instruments to assess health-related quality of life during and after menopause. Qual Life Res 2005;14:309–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. Observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika 1983;70: 41–55. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Austin PC. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivariate Behav Res 2011;46:399–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Horvitz DG, Thompson DJ. A generalization of sampling without replacement from a finite universe. J Am Stat Assoc 1952;47:663–85. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crump RK, Hotz VJ, Imbens GW, Mitnik OA. Dealing with limited overlap in estimation of average treatment effects. Biometrika 2009;96:187–99. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li F, Morgan KL, Zaslavsky AM. Balancing covariates via propensity score weighting. J Am Stat Assoc 2017;113:390–400. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robins JM, Finkelstein DM. Correcting for noncompliance and dependent censoring in an AIDS Clinical Trial with inverse probability of censoring weighted (IPCW) log-rank tests. Biometrics 2000;56:779–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.United States Census Bureau. Annual County Resident Population Estimates by Age, Sex, Race, and Hispanic Origin: April 1, 2010, to July 1, 2012. County Characteristics Datasets, 2012. Available at: https://www.census.gov/data/datasets/2016/demo/popest/counties-detail.html. Accessed May 21, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patient-Centered Outcomes Resesearch Institute. PCORI Convenes Workgroups to Refine Targeted Funding Announcements. Publisher GolinHarris, 2013. Available at: https://www.pcori.org/news-release/pcori-and-ahrq-partner-request-applications-study-treatments-uterine-fibroids. Accessed May 21, 2018.

- 29.Gliklich RE, Leavy MB, Velentgas P, et al. Identification of future needs in the comparative management of uterine fibroid disease: a report on the priority-setting process, preliminary data analysis, and research plan. Rockville (MD): es-Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Myers ER, Steege JF. Risk adjustment for complications of hysterectomy: limitations of routinely collected administrative data. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1999;181:567–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dhruva S, Bero L, Redberg R. Strength of study evidence examined by the FDA in premarket approval of cardiovascular devices. JAMA 2009;302:2679–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kramer D, Xu S, Kesselheim A. Regulation of medical devices in the United States and European Union. N Engl J Med 2012;366:848–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garber AM. Modernizing device regulation. N Engl J Med 2010;362:1161–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wechter ME, Stewart EA, Myers ER, Kho RM, Wu JM. Leiomyoma-related hospitalization and surgery: prevalence and predicted growth based on population trends. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2011;205:492.e1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barrett ML, Weiss AJ, Stocks C, Steiner CA, Myers ER. Procedures to treat benign uterine fibroids in hospital inpatinet and hospital-based ambulatory surgery settings, 2013Statistical Brief#200. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Ressearch and Quality; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kuppermann M, Varner RE, Summitt RL Jr, et al. Effect of hysterectomy vs medical treatment on health-related quality of life and sexual functioning: the medicine or surgery (Ms) randomized trial. JAMA 2004;291:1447–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rolnick S, Flores S, Fowler S, Derman R, Davidson B. Conducting randomized, controlled trials: experience with the dysfunctional uterine bleeding intervention trial. J Reprod Med 2001;46:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dickersin K, Munro MG, Clark M, et al. Hysterectomy compared with endometrial ablation for dysfunctional uterine bleeding: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 2007;110:1279–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.