Abstract

The harvesting of visible light is a powerful strategy for the synthesis of weak chemical bonds involving hydrogen that are below the thermodynamic threshold for spontaneous H2 evolution. Piano-stool iridium hydride complexes are effective for the blue-light-driven hydrogenation of organic substrates and contra-thermodynamic dearomative isomerization. In this work, a combination of spectroscopic measurements, isotopic labeling, structure–reactivity relationships, and computational studies has been used to explore the mechanism of these stoichiometric and catalytic reactions. Photophysical measurements on the iridium hydride catalysts demonstrated the generation of long-lived excited states with principally metal-to-ligand charge transfer (MLCT) character. Transient absorption spectroscopic studies with a representative substrate, anthracene revealed a diffusion-controlled dynamic quenching of the MLCT state. The triplet state of anthracene was detected immediately after the quenching events, suggesting that triplet–triplet energy transfer initiated the photocatalytic process. The key role of triplet anthracene on the post-energy transfer step was further demonstrated by employing photocatalytic hydrogenation with a triplet photosensitizer and a HAT agent, hydroquinone. DFT calculations support a concerted hydrogen atom transfer mechanism in lieu of stepwise electron/proton or proton/electron transfer pathways. Kinetic monitoring of the deactivation channel established an inverse kinetic isotope effect, supporting reversible C(sp2)–H reductive coupling followed by rate-limiting ligand dissociation. Mechanistic insights enabled design of a piano-stool iridium hydride catalyst with a rationally modified supporting ligand that exhibited improved photostability under blue light irradiation. The complex also provided improved catalytic performance toward photoinduced hydrogenation with H2 and contra-thermodynamic isomerization.

Keywords: proton coupled electron transfer, iridium, catalysis, photoreduction, ultrafast spectroscopy, weak bonds, kinetic isotope effect

Introduction

The concerted transfer of protons and electrons, also referred to as net hydrogen atom transfer (HAT), is a fundamental chemical transformation with widespread applications in biological processes,1,2 catalysis directed toward organic synthesis,3,4 and energy science.5,6 In many instances, weak element–hydrogen bonds with bond dissociation free energies (BDFEs) below the thermodynamic threshold for spontaneous dihydrogen evolution are formed as intermediates.7,8 Often, external energy sources are required to provide sufficient driving force for endergonic steps. Classic strategies include the addition of strong reducing agents such as alkali metals,9,10 metallocenes,11 and SmI2.12,13 The use of these reagents generates stoichiometric waste, induces functional group incompatibility, and provides driving force in excess of the thermodynamic potential of the desired reaction, termed “chemical overpotential”.6

Harvesting of visible light by chromophoric materials14,15 or direct electrolysis16,17 has been explored to circumvent these limitations. Absorption of photons enables access to long-lived excited states with beneficial energetics compared to the ground state18 that can be translated into chemical driving force and utilized to mediate challenging bond formations. With the photonic energy, milder reductants, such as alkylamines,19,20 Hantzsch esters,21 and organic thiols,22,23 have been successfully applied to expand functional group compatibility.

For reactions involving element–hydrogen bond formation, molecular hydrogen is the ideal reductant, as it obviates stoichiometric waste and allows catalytic reactions at or near thermodynamic potential. In this context, Norton and co-workers have pioneered the synthesis of metal hydrides that promote hydrogen atom transfer and can be regenerated from H2 activation, which were successfully applied to the reduction of alkenes.24−28 Our laboratory has expanded this concept to the synthesis of weak N–H bonds in the context of ammonia synthesis, demonstrating the ability to release free amines from otherwise inert M–N bonds in amide29,30 and nitride31,32 complexes. Although successful in certain instances, intrinsic thermodynamic limitations were identified as isolable metal hydrides typically have M–H BDFEs on the order of 55 kcal/mol or stronger.33 Subsequently, synthesis of N–H or other element–hydrogen bonds significantly weaker than this value becomes challenging with H2 as the hydrogen atom source.

Harnessing photonic energy in conjunction with HAT is an attractive strategy for the synthesis of element–hydrogen bonds with BDFEs less than 55 kcal/mol using H2. Recently, our laboratories reported the application of piano-stool type iridium hydrides34 to the photodriven hydrogenation of unsaturated organic compounds titanium-amido29 and cobalt-imido35 complexes. Although catalytic hydrogenation activity was minimal under dark thermal conditions likely due to strong ground-state Ir–H BDFEs (∼61 kcal/mol), visible light absorption enabled access to reactive excited states and initiated stoichiometric and catalytic reductions (Scheme 1). Element–hydrogen bonds as low as 31 kcal/mol were synthesized using H2, the iridium catalyst, and blue light. Wenger and co-workers recently described a related hydrogen atom transfer of cationic iridium–hydride complexes in the presence of sacrificial primary amines as electron and proton sources,36 whereas proton and hydride transfer reactivity has been observed by Fukuzumi37 and Miller,38,39 respectively. Detailed elementary steps of these processes, however, have been difficult to study mainly because of the metastable and transient nature of key intermediates.

Scheme 1. Visible-Light-Driven Hydrogen Atom Transfer Using H2: (a) General Reaction Scheme and Mechanistic Hypothesis; (b) Comprehensive Mechanistic Study of Iridium-Catalyzed Hydrogen Atom Transfer Reactions.

Here, we describe a comprehensive mechanistic study of the photodriven hydrogenation of anthracene with piano-stool iridium−hydride complexes. The photophysical properties of the iridium hydride catalysts and their long-lived excited states were investigated with various spectroscopic techniques. Experimental and computational findings supported the generation of a long-lived metal-to-ligand charge transfer (MLCT)-based excited state with a nanosecond lifetime at room temperature. Transient absorption spectroscopic analyses provided direct evidence for triplet–triplet energy transfer (EnT) between the excited-state iridium complex and an anthracene substrate. The resulting triplet excited anthracene undergoes concerted proton and electron transfer to form the weak C–H bonds. A photoinduced catalyst deactivation pathway coupled with an understanding of the C–H bond-forming event resulted in the design of next-generation catalysts with improved photostability and reactivity for photodriven hydrogenation reactions and contra-thermodynamic dearomative isomerization.

Results and Discussion

Consideration of Possible Photochemical Pathways During Catalysis

Possible pathways for the photocatalytic hydrogenation of anthracene were considered and are presented in Scheme 2. In our previous report on the development of the catalytic reactions,34 the neutral iridium hydrides were effective for stoichiometric C–H bond formation under N2 and catalytic hydrogenation under H2. These observations indicated that the nature of the photocatalytic process was independent of the atmosphere and study of the stoichiometric reaction would inform the mechanism of the catalytic process.

Scheme 2. Possible Mechanisms upon Photoirradiation of a Solution of a Substrate and a Neutral Iridium Hydride Complex and Key Distinctions from Previously Studied Cationic Complexes.

Sub = substrate.

Irradiation of the iridium(III) hydride with blue light leads to a photoexcited state. Key to the observed reactivity is the nature of this excited state and its lifetime; is it sufficiently long-lived to engage in productive C–H bond formation? Previous studies on cationic iridium-hydrides have measured a value of 80 ns,40 but the related values on neutral complexes used in this work are unknown. Importantly, understanding the nature of the photoexcited state is key to understanding the preferred mode of reactivity for the iridium hydride. Possibilities include energy, hydride, proton, and hydrogen atom transfer (Scheme 2c–f). Although photoexcitation of cationic iridium hydrides is known to promote catalytic hydride transfer with sacrificial sodium formate that generates CO2 as a byproduct,39 the hydrogenation of a range of substrates including Co=N bonds in imido complexes suggests that distinct reactivity is operative with the neutral examples.

Photophysical Properties of Piano-Stool Iridium–Hydride Complexes

Our studies commenced with comprehensive evaluation of the photophysical properties of piano-stool iridium hydride complexes bearing “L-X” type supporting ligands.34 Electronic absorption spectra of Ir1–Ir4 exhibit absorption features in the visible region, which are red-shifted with increased π-conjugation on the bidentate ligand from Ir1 to Ir3 in tetrahydrofuran (THF) (Figure 1). Absorptions at vertical excitations over 400 nm were tentatively assigned to metal-to-ligand charge transfer (MLCT) transitions, as examined by time-dependent density functional theory (TD-DFT) calculations, followed by natural transition orbital analysis at the cPCM (THF) ZORA/B3LYP/{ZORA-def2-TZVP, SARC-ZORA-TZVP (Ir)} level of theory (Figure S118–S126).

Figure 1.

Photophysical properties of piano-stool iridium hydride complexes. Electronic absorption, emission, and excitation spectra (left) are shown in blue, red, and gray colors, respectively. Absorption spectra were recorded at 23 °C in THF. Time-correlated single photon counting (TCSPC, right) and emission spectra were recorded at 77 K in 2-MeTHF glass with λexc = 406 or 400 nm. Excitation spectra at 77 K were recorded with λems = 570, 670, 660, and 620 nm for Ir1, Ir2, Ir3, and Ir4, respectively.

Although all four iridium compounds provided no evidence for emission at room temperature, emission features were observed in 2-methyltetrahydrofuran (2-MeTHF) glasses at 77 K upon photoexcitation with 400 nm light. As shown in Figure 1, broad and featureless emission bands were detected between 570 and 670 nm that are strong indicators of charge transfer (CT) states in comparison to distinctive vibronic progressions resulted from local excitation of the ligands themselves.40 Restoration of emission at low temperature is commonly acknowledged because of the suppression of nonradiative decay channels resulting from the cooling of certain critical molecular or bath vibrational modes.41 Triplet energies were estimated by the tangent method (Figures S12–15), with Ir1 giving the highest value of 2.46 eV. Increasing the π-conjugation of bidentate ligands resulted in a decrease in the triplet energy (Ir2 and Ir3, Table 1). Excited-state lifetimes at 77 K were measured with the TCSPC technique, where the longest lifetime of 15.7 μs was obtained with Ir2. The others featured relatively short excited-state lifetimes of 1–4 μs.

Table 1. Extinction Coefficients (ε), Triplet Energies (E00), and Excited-State Lifetimes (τ) of Iridium Hydride Complexesa.

| Ir compounds | ε at 465 nm (M–1 cm–1) | E00 (eV) | τ (μs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ir1 | 2087 | 2.46 | 4.20 |

| Ir2 | 4124 | 2.20 | 15.7 |

| Ir3 | 6526 | 2.10 | 2.05 |

| Ir4 | 1525 | 2.27 | 1.02 |

Excited-state lifetimes at 77 K were measured using TCSPC in 2-MeTHF glass with λexc = 406 nm.

Transient Absorption Spectroscopic Analysis

Femtosecond transient absorption (TA) spectroscopy was applied to the study of the time-dependent excited-state properties at room temperature. Among the iridium hydride complexes, the transient absorption studies were focused on the dynamics between Ir2 and the anthracene (Ant) substrate. This catalyst–substrate combination was targeted because the hydrogenation reactivity with Ir2 outperformed the other three iridium catalysts under both stoichiometric and catalytic conditions (Scheme 3). For example, Ir1, Ir3, and Ir4 gave 19%, <5%, and 9% yields under otherwise identical catalytic conditions, respectively.34

Scheme 3. Photodriven Stoichiometric and Catalytic Hydrogenation of Ant with Ir2.

Conditions and yields were previously reported in ref (34) .

At the outset, the excited-state dynamics of Ir2 were probed by TA spectroscopy with 450 nm photoexcitation in THF at room temperature. Although toluene and THF solvents were both effective for the catalytic reduction reactions (Scheme 3),34 THF was ideal for photophysical studies due to high solubility of the reaction components. The TA spectra displayed a ground-state bleaching (GSB) signal centered at 460 nm and two excited-state absorption (ESA) signals at 390 and 540 nm (Figure 2a and Figure S37), with the baseline recovered on a nanosecond time scale. The observed ESA at 540 nm was assigned as the reduced bidentate ligand, benzo[h]quinoline (Bq). In situ electrochemical reduction of free Bq generated a distinctive absorption feature at 520 nm, which matches appropriately with the aforementioned ESA of Ir2 (Figure 2b and Figure S23). These results indicated that the excited state of Ir2 bears CT character with the negative charge located at the Bq•– ligand (Figure 2c). Computational spin state calculations of the triplet excited state of Ir2 also supported this CT assignment, best described as a triplet excited state with metal-to-ligand (ML) and partial ligand-to-ligand (LL) CT character.34 Castellano, Miller, and co-workers assigned similar MLCT/LLCT character with cartionic iridium methyl complexes bearing neutral bipyridine donors,40 compounds distinct from those reported here.

Figure 2.

Transient absorption (TA) spectroscopic studies. (a) TA spectra of photoexcited Ir2 at 23 °C in THF with λexc = 450 nm and pump power = 100 μW at 1 ps, 500 ps, 1.5 ns, and 6 ns. (b) Differential absorption spectrum of free Bq radical anion at 23 °C in THF collected by electrolysis at −2.3 V against Ag/AgCl electrode. Inset: absorption spectra of Bq•– in THF after 10, 20, 30, and 40 s of electrolysis. (c) DFT-computed spin density of Bq radical anion. (d) TA spectra of a mixture of 0.89 mM Ir2 and 74 mM Ant at 23 °C in THF with λexc = 450 nm and pump power = 100 μW at 1 ps, 100 ps, 300 ps, 500 ps, 1 ns, and 6 ns. Inset: kinetic traces of the same mixture at 425 (orange) and 530 nm (navy). (e) Stern–Volmer plot of Ir2 and Ant at 23 °C in THF. ktot = 1/τrise, kq, Ant = 6.8(3) × 109 M–1 s–1. (f) Comparison of TA spectrum of the mixture of 0.89 mM Ir2 and 74 mM Ant (black) with λexc = 450 nm at 2 ns delay and those of 112 mM Ant (orange) with λexc = 355 nm at 1 ns, 20 ns, 40 ns, 100 ns, 500 ns, 1 μs, 3 μs, 6 μs, 20 μs, and 80 μs at 23 °C in THF. Pump power = 100 μW. (g) Schematic description of the triplet–triplet EnT process between photoexcited Ir2 and Ant.

On the basis of the relatively long lifetime of photoexcited Ir2, this excited state was tentatively assigned to be a spin triplet with a lifetime of 1.01 ns, which is the only time constant obtained from global analysis (Figure S41). Therefore, intersystem crossing (ISC) from the singlet to the triplet state likely occurs within the instrument response period with a pump pulse of ∼200 fs. The ultrafast ISC is common especially with molecules containing heavy metal atoms such as iridium as a result of their large spin–orbital coupling constants.42 Increasing the concentration of Ir2 had minimal impact on the lifetime, suggesting that the self-quenching mechanism is not operative (Figure S45).43 As the system was cooled from room temperature to 77 K, the lifetime increases monotonically from 1.01 ns to 15.7 μs (Figure S46−48). A similar temperature dependence was reported by Castellano, Miller, and co-workers for another structurally related iridium hydride complex,40 whose excited state was assigned to be a ML/LLCT state. In addition, TA signals were linearly proportional to the pump power (Figure S44), suggesting that the described photophysics are initiated by single-photon absorption. Given the spectroscopic and computational results in conjunction with previous studies, photoexcitation of Ir2 with 450 nm light results in ultrafast ISC and yields a long-lived triplet ML/LLCT state for initiating the photocatalysis of interest.

With a detailed understanding of the photophysics of Ir2, the interaction between the photoexcited iridium catalyst Ir2 and a representative substrate Ant was studied. Ant did not have visible absorption features under the conditions of the measurements. Control TA experiments with a THF solution of Ant showed that neither singlet nor triplet excited states of Ant were accessed with 450 nm photoexcitation (Figures S65 and S66). Consequently, only Ir2 underwent photoexcitation when a mixture of Ir2 and Ant was subjected with 450 nm photoexcitation, and diagnostic ESA and GSB signals of photoexcited Ir2 were observed. These signals gradually decayed and subsequently evolved into two distinctive absorption features centered at 400 and 425 nm with a lifetime of ∼14 μs (Figure 2d and Figures S53–S60). Increasing the concentration of Ant induced more rapid decay of the photoexcited Ir2 and a Stern–Volmer relationship was established with a quenching rate constant of 6.8(3) × 109 M–1 s–1 (Figure 2e, Table 2). The gas chromatography-quadrupole time-of-flight (GC-Q-TOF) analysis of the mixture of Ir2 and Ant after 100 μW laser irradiation confirmed gradual generation of DHA albeit with low efficiency (Figure S144). The observed diminished reactivity compared to LED irradiation conditions is due to the significant difference in the power of the light sources, as the power of the LED (30 W) is 5 orders of magnitude higher than that of the laser source (100 μW). Otherwise identical quenching experiments of the photoexcited Ir2 in the presence of 78 mM DHA revealed minimal changes in the lifetime from 1.01(1) ns to 930(2) ps, suggesting that Ant is the dominant quencher throughout the course of the reaction (Figures S97–S100).

Table 2. Deuterium Kinetic Isotope Effect for Excited State Quenching of Ir2 and Ir2-d with Ant at 23 °Ca.

| entry | Ir compound | [Ant] (mM) | τrise (ns) | kq (× 109 M–1 s–1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ir2 | 0 | 1.01 | 6.8 (3) |

| 2 | 24 | 0.871 | ||

| 3 | 48 | 0.749 | ||

| 4 | 74 | 0.647 | ||

| 5 | 112 | 0.587 | ||

| 6 | Ir2-d | 0 | 1.23 | 6.0 (2) |

| 7 | 24 | 1.09 | ||

| 8 | 48 | 0.888 | ||

| 9 | 74 | 0.796 | ||

| 10 | 112 | 0.676 |

KIE = (kq with Ir2)/(kq with Ir2 – d) = 1.13 (6).

To further explore the nature of the quenching mechanism, deuterium kinetic isotope effects (KIE) were determined with the iridium deuteride Ir2-d in place of Ir2. A primary KIE value44 would be expected if the cleavage of the Ir–H bond is involved in the quenching step,45 whereas a KIE near unity would be anticipated if the quenching process is mainly electronic in nature, Ir–H cleavage is post rate determining, or contributions from excited-state vibrational states and proton tunneling become significant.46 A series of Stern–Volmer experiments with Ir2-d produced a quenching rate constant of 6.0(2) × 109 M–1 s–1 (Table 2), establishing a KIE value of 1.13(6) at ambient temperature, consistent with a photoinduced electronic process, such as electron transfer (ET) or EnT.

On the basis of the observed KIE near unity, the newly generated absorption features at 400 and 425 nm are likely due to the formation of either anionic/cationic Ant radicals47−49 arising from ET (Scheme 2a, b) or triplet excited Ant (3Ant*) from EnT (Scheme 2f).50,51 Difference absorption spectra of cationic47,49 and anionic48,52Ant radicals were obtained by spectroelectrochemistry (Figures S24–27) showing features in the visible range from 390 to 700 nm. None of these features were observed in the transient dynamics of the mixture of Ir2 and Ant (Figure S28). Because 3Ant* can be readily generated by irradiating Ant with ultraviolet light,53,54 a THF solution of Ant without Ir2 was subjected to the TA measurement with 355 nm photoexcitation (Figures S67−S74). Two prominent absorption features at 400 and 425 nm were observed that are consistent with the previous reports,50,51,55,56 including the pioneering pulse radiolysis studies of Porter and co-workers,50 which also matched the TA signals in the mixture of Ir2 and Ant (Figure 2f). These results confirmed the formation of 3Ant* as a consequence of the quenching of Ir2 with Ant. Therefore, triplet–triplet EnT between Ir2 and Ant is most likely responsible for initiating the photoactivation process (Figure 2g). Switching the solvent from THF to toluene produced the same diagnostic peaks of 3Ant*, confirming the commonality of the triplet–triplet EnT mechanism in different solvents (Figures S61–S64).

Global analysis of the excited-state dynamics of Ant upon photoexcitation with 355 nm light yielded fast and slow components of 1.8 and 17.3 μs, respectively (Figures S71–S74). The former is attributed to triplet–triplet annihilation (TTA) among 3Ant* molecules, where the rate of the TTA is proportional to the square of the triplet concentration.57−59 Because direct photoexcitation produced a solution of concentrated triplets due to the large extinction coefficient of the Ant at 355 nm, the TTA was observed as evidenced by the appearance of the fast component. The high-lying singlet excited Ant, produced by TTA, evolved to another 3Ant* that decayed on a longer time scale with a lifetime of 17.3 μs.

To compare the different illumination conditions between the TA pulsed laser and the blue Kessil LED source, the excitation power densities of two light sources were experimentally measured. The excitation power density of the blue LED lamp is 1328.6 μmol photons m–2 s–1, whereas the peak power density of the pulsed 450 nm laser was estimated to be 3975.0 μmol photons m–2 s–1, based on a combination of beam size measurement and Gaussian pulse fitting (Figure S37). On the basis of the aforementioned single-photon absorption behavior of the substrate under the laser conditions (Figure S44), it was concluded that the photoactivation of Ant under the LED conditions should be initiated by single photon absorption of Ir2, with no interference from multiphoton absorption. Consequently, it is likely that a triplet–triplet EnT mechanism likely operates under both illumination conditions in promoting the first HAT event.

Mechanistic Pathways of Post-EnT Process

Direct spectroscopic detection of 3Ant* raised questions on how hydrogenation occurs following the triplet–triplet EnT process. Potential mechanisms of HAT to Ant include a stepwise or concerted process, as shown in Scheme 4. The stepwise electron transfer-proton transfer (ET-PT) mechanism refers to the case where the reduction of Ant by Ir2 precedes proton transfer (PT) from cationic Ir2+, affording anionic Ant radical (Ant–•) as an intermediate. In a similar manner, a stepwise PT-ET mechanism would generate the same final products, AntH• and 17-electron Ir2′ compounds, through protonated AntH+ intermediates. A concerted mechanism bypasses intermediate formation by traversing a HAT transition state where proton and electron are transferred simultaneously. Our experimental efforts to examine the thermodynamics of these mechanisms were unsuccessful mainly because of the inaccessibility of reliable redox potentials of reaction components. For example, electrochemical anodic oxidation of Ir2 showed irreversible behavior at near 0 V of peak potential (vs ferrocenium/ferrocene redox couple), which prevented determination of half-wave oxidation potential (Figure S131).60 The electrochemical irreversibility likely arises from the instability of the corresponding Ir(IV) intermediate, which is susceptible to oxidatively induced reductive elimination.61,62 Attempts to detect Ir2′ by pump–probe ultrafast spectroscopy was unsuccessful, likely because of the low quantum yield of the formal HAT process under the conditions of the laser experiment (Figures S57–S60). Likewise, attempts to independently synthesize Ir2′ from addition of (2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidin-1-yl)oxyl (TEMPO) radical to Ir2 generated an intractable mixture,26 highlighting the challenges associated with independent synthesis of Ir2′.

Scheme 4. Stepwise and Concerted Mechanisms of the First Hydrogen Atom Transfer Process Following the Dexter Triplet–Triplet EnT.

Two indirect ways were therefore devised to evaluate the mechanisms using a combination of computational and experimental measurements. First, in silico calculations of thermodynamic relationships were performed at the CPCM(THF) B3LYP/{6-311+G**, LANL2TZ(-f)}//{6-31G**, LANL2DZ} level of theory, with the energetic requirements to access each species illustrated in Scheme 4. Computationally derived redox potentials of organic and organometallic species have been extensively studied with a similar level of theory with a continuum solvation model, and benchmark studies indicated quantitative correlation with experimentally measured values.63,64 The first processes of stepwise ET-PT and PT-ET pathways were computed to be thermodynamically uphill by +39.7 and +56.0 kcal/mol, respectively, while the following processes were both highly exergonic. By contrast, concerted HAT was estimated to be spontaneous with ΔG ° of −13.6 kcal/mol. Transition state calculation further confirmed that the HAT is kinetically facile under ambient conditions (ΔG‡ of 19.7 kcal/mol, vide infra). Potential pathways by direct photoinduced electron transfers from the iridium MLCT state were ruled out based on the unfavorable thermodynamics computed by DFT (Figure S129).

With computational support for a HAT mechanism, proof-of-concept experiments were designed to further elucidate the key roles of 3Ant* during the hydrogenation process (Figure 3). Of particular interest was to evaluate whether 3Ant* can undergo successful hydrogenation with a HAT donor with similar or stronger E–H BDFEs compared to that of the Ir–H bond of Ir2 (61 kcal/mol, Figure 3a). Hydroquinone (H2Q) was selected as a representative hydrogen atom donor because of its relatively low BDFEs (66 kcal/mol)65 and negligible absorption of visible light. fac-Ir(ppy)3 (ppy = 2-phenylpyridinato) was chosen as a triplet photosensitizer because of its efficient ISC to the triplet manifolds and high triplet energy (E00 = 53.6 kcal/mol)66 suited for efficient triplet–triplet EnT with Ant.

Figure 3.

Mechanistic probes of post-EnT processes. (a) Reaction design consisting of photosensitizer fac-Ir(ppy)3, Ant, and HAT reagents. (b) Steady-state emission spectra of fac-Ir(ppy)3 with 0.606, 0.303, and 0.097 M of H2Q (blue) and 440, 220, 110, and 55 μM of Ant (orange) in THF with λexc = 400 nm. (c) Stern–Volmer plots of fac-Ir(ppy)3 with H2Q (blue) and Ant (orange) from Figure 3b. (d) TA spectra of a mixture of 220 μM fac-Ir(ppy)3 and 440 μM Ant in THF with λexc = 450 nm and pump power = 100 μW at 1 ns, 10 ns, 20 ns, 50 ns, 100 ns, 500 ns, and 1 μs. Inset depicts a kinetic trace of the same mixture at 425 nm showing the rise and decay of 3Ant* signals. (e) Photosensitization-induced hydrogenation with H2Q as a HAT reagent.

A series of photoluminescence quenching experiments was initially conducted using steady-state emission spectroscopy to identify the primary quencher for photoexcited fac-Ir(ppy)3 (Figure 3b). Although emission of fac-Ir(ppy)3 was effectively quenched by introducing a relatively low concentration of Ant (55–440 μM), only minimal quenching was observed with a much higher concentration of H2Q (97–610 mM). The quenching rate constant with Ant was calculated to be 4 orders of magnitude (1 × 104 times) larger than that with H2Q (Figure 3c), suggesting that the triplet state of fac-Ir(ppy)3 would be dominantly quenched by Ant in a catalytic reaction.

TA spectroscopy was used to further probe the nature of the quenching with Ant. After photoexcitation of a mixture of fac-Ir(ppy)3 and Ant with 450 nm light, diagnostic signals of ESA at 500 nm and GSB at 400 nm from photoexcited fac-Ir(ppy)3 were observed, which evolved into two features at 400 and 425 nm similar to the ones identified in the previous mixture of Ir2 and Ant (Figures 2d and 3d, and Figure S79–S83), confirming the generation of 3Ant*. Hence the function of fac-Ir(ppy)3 as a triplet photosensitizer was demonstrated and the system dominantly sensitized Ant to 3Ant* upon photoexcitation with 450 nm light. Of note, the lifetime of 3Ant* did not vary significantly with and without the addition of the H atom donor H2Q under the TA conditions (Figure S92), suggesting the HAT reaction between two reaction components is likely a slow, low-quantum-yield process.

Importantly, irradiation of a mixture of Ant, H2Q, and 2 mol % fac-Ir(ppy)3 with blue LEDs generated the desired dihydroanthracene product albeit in low yield (Figure 3e). Control reactions clearly demonstrated that the iridium photosensitizer was necessary for the observed reactivity. The poor reaction efficiency was attributed to a stronger O–H BDFE of H2Q (first O–H BDFE of 80 kcal/mol,2 and average BDFE of 66 kcal/mol65) than that of Ir2 (61 kcal/mol) and inevitable photodimerization of Ant that is insoluble, decreasing the effective concentration of Ant.67 Of note, anthracene dimer formation was also observed under prolonged irradiation (24 h) with Ir2, further confirming the mechanistic relevance. The slow photodimerization rate is consistent with the unfavorable energetics dimerizing from a T1 state and with the reactive state being a singlet excited state of Ant.59

Given the combined computational, spectroscopic, and stoichiometric results, 3Ant* was proposed to abstract a hydrogen atom from HAT reagents including Ir2 and H2Q, completing the hydrogenation process following triplet–triplet EnT. Notably, König and co-workers reported that Birch-type reduction of Ant could be achieved by reductive quenching of excited Ir(III) photosensitizer with electron-rich alkylamines as a reductant.68,69 A sensitization-initiated electron transfer to generate Ant–• was proposed,69−73 which is an inaccessible intermediate under our reaction conditions due to the lack of strong, stoichiometric electron donor (vide supra). In a related example, anthracene reduction was observed as a side product during photochemical amination with amines under high-pressure Hg lamp irradiation,74 further corroborating the critical role of 3Ant*.

Computational Analysis on the Overall Reaction Pathway

Combining the experimental and computational data, a potential energy surface of photoinduced Ant hydrogenation was constructed using the results of DFT calculations with transition state analysis (Figure 4). The reaction was initiated by vertical excitation of Ir2 upon 450 nm irradiation to generate a short-lived singlet excited state, followed by ISC to afford a longer-lived triplet ML/LLCT state 3Ir2*, which was defined as ES in Figure 4. The triplet energy was estimated to be 2.2 eV based on the 77 K emission measurement (Table 1) and subsequent triplet–triplet EnT with Ant (ES → A) is a diffusion-controlled process with an experimentally measured quenching constant of 6.8(3) × 109 M–1 s–1 (Table 1). State A can either undergo relaxation to the ground state (A → GS) or productive hydrogen atom abstraction from the Ir–H bond of Ir2 (A → A-TS). The kinetic barrier of the HAT process was estimated to 19.7 kcal/mol, suggesting that the that overall reaction rate is likely limited by a slow HAT processes. A spin density plot of A-TS clearly illustrates the newly generated radical character on the iridium metal center as well as the Ant substrate. Although equilibrium between state B and its adduct form B′ was computationally expected, the hydroanthracene radical AntH• from B is able to abstract the Ir–H bond from another ground-state Ir2 with an activation barrier of 22.7 kcal/mol (B → B-TS), producing dihydroanthracene (DHA). The regeneration of Ir2 arises from the reaction between Ir2′ and H2, rendering overall transformation exergonic. It should be noted that the detailed mechanism of H2 activation is not elucidated at present, but bimolecular homolysis has been widely proposed in the related complexes with a single coordination site.26

Figure 4.

Computed reaction energy surface of photodriven catalytic hydrogenation of Ant at the CPCM(THF) B3LYP/{6-311+G**, LANL2TZ(-f)}//{6-31G**, LANL2DZ} level of theory. Triplet energy of 3Ir2* and the quenching rate of the triplet–triplet EnT process were experimentally obtained (see Tables 1 and 2, respectively).

Catalyst Decomposition Pathway: Photodriven C–H Reductive Coupling

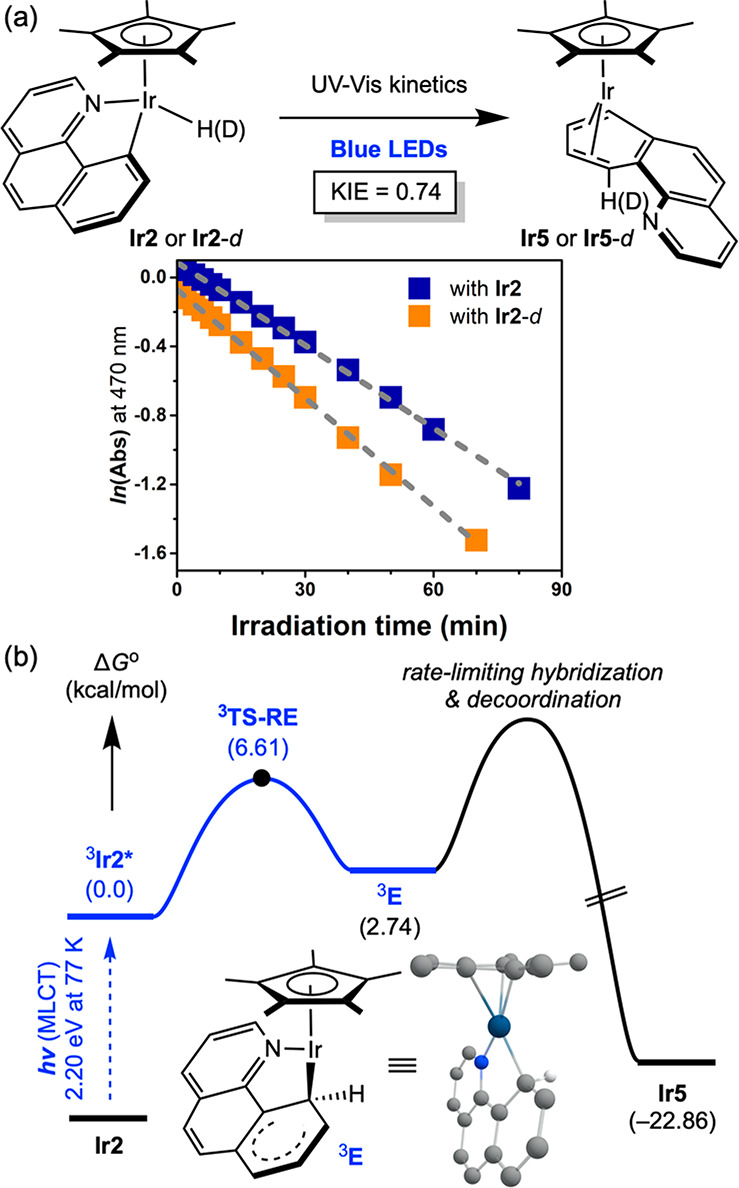

One of the principal limitations of Ir2 as a catalyst for photodriven hydrogenation is competing decomposition upon irradiation. The η4-anthracene complex, Ir5 was identified in previous studies34 as a catalyst deactivation pathway arising from C–H reductive coupling in the absence of H2. To gain further insights into the mechanism of this competing process, reaction kinetic monitoring was performed with Ir2 along with its deuterated isotoplogue, Ir2-d, by electronic absorption spectroscopy (Figure 5a). The time evolution of absorption changes at 470 nm under blue LED irradiation followed clean first-order kinetics and afforded rate constants of 2.6 × 10–4 and 3.5 × 10–4 s–1 for Ir2 and Ir2-d, respectively, at room temperature, establishing an inverse KIE (KIE = kIr2/kIr2-d) of 0.74 for photoinduced C–H reductive elimination.

Figure 5.

Mechanistic study of catalyst deactivation pathways. (a) Deuterium kinetic isotope effect observed by UV–vis kinetic experiments at 23 °C. Spectroscopic data of Ir2 were obtained from ref (34). (b) Computed energy profile of photodriven C–H reductive elimination pathway.

Inverse deuterium kinetic isotopic effects have been frequently observed in processes involving C–H reductive coupling.75,76 The difference in zero-point energy (ZPE) between the deuterated and protio isotopologues in the ground state is overcome by a large difference in ZPE upon accessing the transition state en route to the C–H coupled intermediate. With the iridium complex, photoinduced reductive coupling generates intermediate 3E, whose geometry was successfully optimized by DFT. The geometry of 3E is best described as a Wheland-type σ-adduct77 that undergoes subsequent haptotropic rearrangement en route to Ir5. The experimentally observed inverse KIE in Figure 5a is consistent with the computationally proposed, sp3-hybridized Wheland-type intermediate 3E, which undergoes additional rate-limiting rearomatization and dissociation.75,76,78 Notably, the computed energy of Ir5 is higher than that of isomeric Ir2, demonstrating that the photodriven deactivation process is uphill thermodynamically.

Photostability of Piano-Stool Iridium Hydride Complexes and Improved Catalyst Design

The combined mechanistic data and insights into catalyst deactivation inspired preparation of next generation iridium catalysts for photodriven hydrogenation reactions. Initially, the stoichiometric and catalytic reactivities of the four catalysts shown in Figure 1 were reevaluated. As reported previously,34Ir1, Ir2, and Ir4 exhibited variable reactivity toward Ant hydrogenation, with Ir3 containing an 2-phenylisoquinoline (PIQ) ligand being the notable exception, as no hydrogenation products were observed.

Interestingly, irradiating the reaction mixture containing Ir3 with blue LEDs resulted in a color change from the intense red color diagnostic of the starting iridium hydride that rapidly converted to pale yellow over the course of 2 min. Subsequent analysis by 1H NMR spectroscopy confirmed complete disappearance of iridium-hydride resonance at −14.9 ppm in benzene-d6, implying the photodegradation of the iridium hydride by a C–H reductive coupling process analogous to that forming Ir6 (Figure 5). Additional 2D-NMR spectroscopic analyses suggested the formation of η4-iridium(I) complex Ir6 in analogy to Ir5, further confirming the role of photoinduced C–H reductive elimination as the primary deactivation pathway (Figures S132−S136). Monitoring the reaction by electronic absorption spectroscopy revealed smooth disappearance of the absorption features at 470 nm with a first-order decay constant of 3.0 × 10–2 s–1 at 23 °C (Figure 6a), 2-fold larger than that with Ir2 (Figure 5a), highlighting the decreased stability of Ir3 under irradiation.

Figure 6.

Catalyst design principles. (a) UV–vis kinetic measurements of photodecomposition of Ir3 under blue LED in THF. See the Supporting Information for experimental details. (b) DFT-optimized structure of Ir3 and improved catalyst design.

The relative photoinstability of Ir3 as compared to Ir2 raised the question as to the features of the supporting L–X ligand that facilitated photoinduced C–H reductive coupling. Suppression of this pathway would likely give rise to longer lived and more active photodriven hydrogenation catalysts. Geometry optimizations of Ir2 and Ir3 revealed distinctive structural features on bidentate supporting ligands. Although the idealized aromatic plane was found on the Bq moiety of Ir2, the planes defined by isoquinoline and phenyl moieties of Ir3 exhibited a notable distortion (Figure 6b). In particular, a dihedral angle between the isoquinolinyl and phenyl groups was measured to be 11.3°, significantly deviated from idealized coplanar. The observed tilting relieved strain between a phenyl ortho-C–H bond and an isoquinoline C(8)–H bond of PIQ. Such a deviation from a coplanar geometry was observed in the solid-state structure of (η5-C5Me5)Ir(PIQ)Cl (Figure S150), and this feature has been generally observed in various transition metal complexes having cyclometalated PIQ moieties.79,80

The structural analysis provided useful insight for improved catalyst design. It was hypothesized that release of steric hindrance might lead to a longer-lived photocatalyst that is less susceptible to photodecomposition by C–H reductive coupling. A new iridium complex, Ir7, was targeted whereby the benzo-fused moiety on the PIQ ligand was relocated and replaced by 3-phenylisoquinoline (PIQ2). Computational geometry optimization of Ir7 confirmed the idealized aromatic plane between isoquinoline and phenyl moieties of the PIQ2 ligand suggesting a more photostable iridium hydride.

Targeted Ir7 was synthesized through base-mediated C–H activation/cyclometalation from [(η5-C5Me5)IrCl2]2 and PIQ2, followed by treating with Red-Al (Figure 7a).60 Recrystallization from a saturated THF solution at −30 °C afforded yellow-orange crystals suitable for single-crystal X-ray diffraction. Expectedly, the solid-state structure showed π-conjugation between isoquinolinyl and 3-phenyl groups. Electronic absorption measurements established an extinction coefficient of 2472 M–1 cm–1 (Figure S5). A triplet energy of 2.18 eV was obtained from the glass state supported by 2-MeTHF at 77 K with an excited-state lifetime of 4.96 μs, and transient absorption measurements revealed room temperature excited-state lifetime of 3.7 ns in THF (Figures S16 and S53–S56).

Figure 7.

Synthesis and photostability of Ir7. (a) Synthetic route and the solid-state structure of Ir7 at 30% probability ellipsoids. Hydrogen atoms except for the iridium hydride bond were omitted for clarity. (b) Evaluation of photostability by time-resolved electronic absorption spectroscopy in THF at 23 °C. See the Supporting Information for experimental details.

Irradiation of Ir7 with blue LEDs demonstrated remarkably improved photostability (Figure 7b). In contrast to Ir3, absorption features were minimally changed upon irradiation with blue light over the course of minutes. The absorbance gradually decreased over the course of several hours of irradiation (Figure S117). Time evolution of the absorption changes at 390 nm deviated from first-order decay kinetics, but Ir7 was clearly the longest-lived iridium hydride compound compared to Ir2 and Ir3 under otherwise identical irradiation conditions.

Intrigued by the improved photostability the excited state lifetime of the new iridium compound, the performance of Ir7 for the photocatalytic hydrogenation reactions with Ant were tested (Scheme 5). The improved photostability of Ir7 translated onto higher yields for photodriven anthracene hydrogenation. Blue light irradiation afforded DHA product in 81% yield under 4 atm of H2, a notable increase when compared to that with the first generation catalyst Ir2, which produced 61% yield under identical conditions (Scheme 5a). In addition, improvements were also observed for the photodriven contra-thermodynamic dearomative isomerization of 9,10-dimethylanthracene (Me2Ant, Scheme 5b). Ir2 produced a turnover number (TON) of 1.9, while identical reactions with Ir7 afforded 5.0 TON that corresponds to 50% yield for the dearomatized product. Although the mechanism of the dearomatization process remains under investigation, HAT from Ir–H moiety to the substrate followed by reverse HAT from methyl C(sp3)–H to putative iridium metalloradical species was proposed previously.34 Initial TA experiments with a solution of Ir2 and 37 mM Me2Ant at 450 nm excitation displayed evolution of strong ESA signal at 425 nm (Figures S101–S108), which was assigned as a triplet state of Me2Ant based on direct UV excitation of a pure Me2Ant solution (Figures S109–113). Spectrometric data unequivocally confirmed the generation of 3Me2Ant* by TT-EnT process under visible light irradiation. A DFT-computed thermodynamic square scheme supported a concerted mechanism involving initial HAT from Ir2, followed by back HAT from Me2AntH• radical to afford the observed isomerization product (Figure S130).

Scheme 5. Improved Catalytic Reactivity with Ir7. (a) Catalytic Hydrogenation of Ant. (b) Contra-thermodynamic Dearomative Isomerization.

Conditions and yields were described in ref (34).

Conclusions

The mechanism of photodriven iridium-catalyzed hydrogenation of anthracene has been studied. This reaction involves the formation of weak C–H bonds without the generation of stoichiometric waste. Studies into the photophysical properties of the bifunctional iridium catalyst coupled with studies on the photochemistry of anthracene support a pathway involving photogeneration of an iridium triplet excited state that undergoes triplet–triplet EnT to the substrate. Triplet anthracene then engages in concerted proton coupled electron transfer with the ground state iridium hydride promoting weak C–H bond formation. Identification of a photoinduced catalytic deactivation pathway and associated inverse deuterium KIE support deleterious C–H reductive coupling followed by haptotropic rearrangement. These insights guided synthesis of a next-generation catalyst with improved performance in anthracene hydrogenation and contra-thermodynamic dearomative isomerization.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Catalysis Science program, under Award DE-SC0006498. S.K. acknowledges Samsung Scholarship for partial financial support. G.D.S. is a fellow of the CIFAR BSE Program. L.T. and G. D. S. acknowledge support from BioLEC, an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences, under Award DE-SC0019370.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacsau.1c00460.

General considerations, full experimental sections on preparations of catalysts and spectroscopic measurements, and spectroscopic and computational data (PDF)

Accession Codes

CCDC 2089917 and 2089923 contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif, or by emailing data_request@ccdc.cam.ac.uk, or by contacting The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK; fax: + 44 1223 336033.

Author Contributions

† Y.P. and L.T. contributed equally.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Stubbe J.; Nocera D. G.; Yee C. S.; Chang M. C. Y. Radical Initiation in the Class I Ribonucleotide Reductase: Long-Range Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer?. Chem. Rev. 2003, 103, 2167–2202. 10.1021/cr020421u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren J. J.; Tronic T. A.; Mayer J. M. Thermochemistry of Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer Reagents and its Implications. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 6961–7001. 10.1021/cr100085k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentry E. C.; Knowles R. R. Synthetic Applications of Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer. Acc. Chem. Res. 2016, 49, 1546–1556. 10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenvi R. A.; Matos J. L. M.; Green S. A. Hydrofunctionalization of Alkenes by Hydrogen-Atom Transfer. Organic Reactions 2019, 383–470. 10.1002/0471264180.or100.07. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Waidmann C. R.; Miller A. J. M.; Ng C.-W. A.; Scheuermann M. L.; Porter T. R.; Tronic T. A.; Mayer J. M. Using Combinations of Oxidants and Bases as PCET Reactants: Thermochemical and Practical Considerations. Energy Environ. Sci. 2012, 5, 7771–7780. 10.1039/c2ee03300c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bezdek M. J.; Chirik P. J. A Fresh Approach to Ammonia Synthesis. Nature 2019, 568, 464–466. 10.1038/d41586-019-01213-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezdek M. J.; Guo S.; Chirik P. J. Coordination-induced Weakening of Ammonia, Water, and Hydrazine X–H Bonds in a Molybdenum Complex. Science 2016, 354, 730–733. 10.1126/science.aag0246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalkley M. J.; Peters J. C. Relating N–H Bond Strengths to the Overpotential for Catalytic Nitrogen Fixation. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 2020, 1353–1357. 10.1002/ejic.202000232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch A. J. 117. Reduction by Dissolving Metals. Part I. J. Chem. Soc. 1944, 430–436. 10.1039/jr9440000430. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo B. I.; Kim Y. J.; You Y.; Yang J. W.; Kim S. W. Birch Reduction of Aromatic Compounds by Inorganic Electride [Ca2N]+•e– in an Alcoholic Solvent: An Analogue of Solvated Electrons. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 13847–13853. 10.1021/acs.joc.8b02094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yandulov D. V.; Schrock R. R. Catalytic Reduction of Dinitrogen to Ammonia at a Single Molybdenum Center. Science 2003, 301, 76–78. 10.1126/science.1085326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaou K. C.; Ellery S. P.; Chen J. S. Samarium Diiodide Mediated Reactions in Total Synthesis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 7140–7165. 10.1002/anie.200902151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chciuk T. V.; Flowers R. A. Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer in the Reduction of Arenes by SmI2-Water Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 11526–11531. 10.1021/jacs.5b07518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twilton J.; Le C.; Zhang P.; Shaw M. H.; Evans R. W.; MacMillan D. W. C. The Merger of Transition Metal and Photocatalysis. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2017, 1, 0052. 10.1038/s41570-017-0052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marzo L.; Pagire S. K.; Reiser O.; König B. Visible-Light Photocatalysis: Does It Make a Difference in Organic Synthesis?. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 10034–10072. 10.1002/anie.201709766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalkley M. J.; Garrido-Barros P.; Peters J. C. A Molecular Mediator for Reductive Concerted Proton-electron Transfers via Electrocatalysis. Science 2020, 369, 850–854. 10.1126/science.abc1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.; Kim H.; Lambert T. H.; Lin S. Reductive Electrophotocatalysis: Merging Electricity and Light To Achieve Extreme Reduction Potentials. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 2087–2092. 10.1021/jacs.9b10678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole J. P.; Chen D.-F.; Kudisch M.; Pearson R. M.; Lim C.-H.; Miyake G. M. Organocatalyzed Birch Reduction Driven by Visible Light. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 13573–13581. 10.1021/jacs.0c05899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condie A. G.; González-Gómez J. C.; Stephenson C. R. J. Visible-Light Photoredox Catalysis: Aza-Henry Reactions via C–H Functionalization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 1464–1465. 10.1021/ja909145y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ischay M. A.; Anzovino M. E.; Du J.; Yoon T. P. Efficient Visible Light Photocatalysis of [2 + 2] Enone Cycloadditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 12886–12887. 10.1021/ja805387f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P.-Z.; Chen J.-R.; Xiao W.-J. Hantzsch Esters: An Emerging Versatile Class of Reagents in Photoredox Catalyzed Organic Synthesis. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2019, 17, 6936–6951. 10.1039/C9OB01289C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loh Y. Y.; Nagao K.; Hoover A. J.; Hesk D.; Rivera N. R.; Colletti S. L.; Davies I. W.; MacMillan D. W. C. Photoredox-catalyzed Deuteration and Tritiation of Pharmaceutical Compounds. Science 2017, 358, 1182. 10.1126/science.aap9674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin N. Y.; Ryss J. M.; Zhang X.; Miller S. J.; Knowles R. R. Light-driven Deracemization Enabled by Excited-state Electron Transfer. Science 2019, 366, 364–369. 10.1126/science.aay2204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith D. M.; Pulling M. E.; Norton J. R. Tin-Free and Catalytic Radical Cyclizations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 770–771. 10.1021/ja0673276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estes D. P.; Norton J. R.; Jockusch S.; Sattler W. Mechanisms by Which Alkynes React with CpCr(CO)3H. Application to Radical Cyclization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 15512–15518. 10.1021/ja306120n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y.; Norton J. R. Kinetics and Thermodynamics of H–/H•/H+ Transfer from a Rhodium(III) Hydride. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 5938–5948. 10.1021/ja412309j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao C.; Dahmen T.; Gansäuer A.; Norton J. Anti-Markovnikov Alcohols via Epoxide Hydrogenation Through Cooperative Catalysis. Science 2019, 364, 764–767. 10.1126/science.aaw3913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y.; Norton J. R.; Salahi F.; Lisnyak V. G.; Zhou Z.; Snyder S. A. Highly Selective Hydrogenation of C=C Bonds Catalyzed by a Rhodium Hydride. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 9657–9663. 10.1021/jacs.1c04683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappas I.; Chirik P. J. Ammonia Synthesis by Hydrogenolysis of Titanium–Nitrogen Bonds Using Proton Coupled Electron Transfer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 3498–3501. 10.1021/jacs.5b01047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappas I.; Chirik P. J. Catalytic Proton Coupled Electron Transfer from Metal Hydrides to Titanocene Amides, Hydrazides and Imides: Determination of Thermodynamic Parameters Relevant to Nitrogen Fixation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 13379–13389. 10.1021/jacs.6b08009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D.; Loose F.; Chirik P. J.; Knowles R. R. N–H Bond Formation in a Manganese(V) Nitride Yields Ammonia by Light-Driven Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 4795–4799. 10.1021/jacs.8b12957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S.; Zhong H.; Park Y.; Loose F.; Chirik P. J. Catalytic Hydrogenation of a Manganese(V) Nitride to Ammonia. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 9518–9524. 10.1021/jacs.0c03346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J.; Pulling M. E.; Smith D. M.; Norton J. R. Unusually Weak Metal–Hydrogen Bonds in HV(CO)4(P–P) and Their Effectiveness as H• Donors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 4250–4252. 10.1021/ja710455c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park Y.; Kim S.; Tian L.; Zhong H.; Scholes G. D.; Chirik P. J. Visible Light Enables Catalytic Formation of Weak Chemical Bonds with Molecular Hydrogen. Nat. Chem. 2021, 13, 969–976. 10.1038/s41557-021-00732-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park Y.; Semproni S. P.; Zhong H.; Chirik P. J. Synthesis, Electronic Structure, and Reactivity of a Planar Four-Coordinate, Cobalt–Imido Complex. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 14376–14380. 10.1002/anie.202104320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreier M. R.; Pfund B.; Guo X.; Wenger O. S. Photo-triggered Hydrogen Atom Transfer From an Iridium Hydride Complex to Unactivated Olefins. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 8582–8594. 10.1039/D0SC01820A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suenobu T.; Guldi D. M.; Ogo S.; Fukuzumi S. Excited-State Deprotonation and H/D Exchange of an Iridium Hydride Complex. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2003, 42, 5492–5495. 10.1002/anie.200352061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett S. M.; Pitman C. L.; Walden A. G.; Miller A. J. M. Photoswitchable Hydride Transfer from Iridium to 1-Methylnicotinamide Rationalized by Thermochemical Cycles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 14718–14721. 10.1021/ja508762g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaphan D. M.; Brereton K. R.; Klet R. C.; Witzke R. J.; Miller A. J. M.; Mulfort K. L.; Delferro M.; Tiede D. M. Photocatalytic Transfer Hydrogenation in Water: Insight into Mechanism and Catalyst Speciation. Organometallics 2021, 40, 1482–1491. 10.1021/acs.organomet.1c00133. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deaton J. C.; Taliaferro C. M.; Pitman C. L.; Czerwieniec R.; Jakubikova E.; Miller A. J. M.; Castellano F. N. Excited-State Switching between Ligand-Centered and Charge Transfer Modulated by Metal–Carbon Bonds in Cyclopentadienyl Iridium Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57, 15445–15461. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.8b02753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claude J. P.; Meyer T. J. Temperature Dependence of Nonradiative Decay. J. Phys. Chem. 1995, 99, 51–54. 10.1021/j100001a010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hedley G. J.; Ruseckas A.; Samuel I. D. W. Ultrafast Intersystem Crossing in a Red Phosphorescent Iridium Complex. J. Phys. Chem. A 2009, 113, 2–4. 10.1021/jp808944n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers M. B.; Kurtz D. A.; Pitman C. L.; Brennaman M. K.; Miller A. J. M. Efficient Photochemical Dihydrogen Generation Initiated by a Bimetallic Self-Quenching Mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 13509–13512. 10.1021/jacs.6b08701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigeleisen J. The Relative Reaction Velocities of Isotopic Molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 1949, 17, 675–678. 10.1063/1.1747368. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morton C. M.; Zhu Q.; Ripberger H.; Troian-Gautier L.; Toa Z. S. D.; Knowles R. R.; Alexanian E. J. C–H Alkylation via Multisite-Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer of an Aliphatic C–H Bond. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 13253–13260. 10.1021/jacs.9b06834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyburski R.; Liu T.; Glover S. D.; Hammarström L. Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer Guidelines, Fair and Square. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 560–576. 10.1021/jacs.0c09106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto Y.; Ma X. H.; Hayashi K. Pulse radiolysis study of the formation of aromatic radical cations enhanced by diphenyliodonium salts. J. Phys. Chem. 1987, 91, 5343–5347. 10.1021/j100304a041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Das T. N.; Priyadarsini K. I. Transients Formed During Reduction of Polynuclear Aromatics: A Pulse Radiolysis Study. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2 1993, 733–739. 10.1039/p29930000733. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Naqvi K. R.; Melø T. B. Reduction of Tetranitromethane by Electronically Excited Aromatics in Acetonitrile: Spectra and Molar Absorption Coefficients of Radical Cations of Anthracene, Phenanthrene and Pyrene. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2006, 428, 83–87. 10.1016/j.cplett.2006.07.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Land E. J.; Porter G. Extinction Coefficients of Triplet-triplet Transitions. Proc. R. Soc. A 1968, 305, 457–471. [Google Scholar]

- Lang B.; Mosquera-Vázquez S.; Lovy D.; Sherin P.; Markovic V.; Vauthey E. Broadband Ultraviolet-visible Transient Absorption Spectroscopy in the Nanosecond to Microsecond Time Domain with Sub-nanosecond Time Resolution. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2013, 84, 073107. 10.1063/1.4812705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aruga T.; Ito O.; Matsuda M. Photoinduced electron transfer from anions. Part 2. Formation and decay of radical anions of aromatic compounds produced by photoinduced electron transfer from the triphenylstannyl anion. J. Phys. Chem. 1982, 86, 2950–2953. 10.1021/j100212a028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Birks J. B.; Cameron A. J. W.; Mitchell J. S. Crystal fluorescence of carcinogens and related organic compounds. Proc. R. Soc. A 1959, 249, 297–317. [Google Scholar]

- Jones P. F.; Nicol M. Excimer Fluorescence of Crystalline Anthracene and Naphthalene Produced by High Pressure. J. Chem. Phys. 1965, 43, 3759–3760. 10.1063/1.1696547. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Castellano F. N.; Ruthkosky M.; Meyer G. J. Photodriven Energy Transfer from Cuprous Phenanthroline Derivatives. Inorg. Chem. 1995, 34, 3–4. 10.1021/ic00105a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruthkosky M.; Castellano F. N.; Meyer G. J. Photodriven Electron and Energy Transfer from Copper Phenanthroline Excited States. Inorg. Chem. 1996, 35, 6406–6412. 10.1021/ic960503z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker C. A.; Joyce T. A. Delayed fluorescence of anthracene and some substituted anthracenes. Chem. Commun. (London) 1967, 744–745. 10.1039/c19670000744. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Birks J. B. The quintet state of the pyrene excimer. Phys. Lett. A 1967, 24, 479–480. 10.1016/0375-9601(67)90152-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Charlton J. L.; Dabestani R.; Saltiel J. Role of Triplet-triplet Annihilation in Anthracene Dimerization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983, 105, 3473–3476. 10.1021/ja00349a017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y.; Li L.; Shaw A. P.; Norton J. R.; Sattler W.; Rong Y. Synthesis, Electrochemistry, and Reactivity of New Iridium(III) and Rhodium(III) Hydrides. Organometallics 2012, 31, 5058–5064. 10.1021/om300398r. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shin K.; Park Y.; Baik M.-H.; Chang S. Iridium-catalysed Arylation of C–H Bonds Enabled by Oxidatively Induced Reductive Elimination. Nat. Chem. 2018, 10, 218–224. 10.1038/nchem.2900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.; Shin K.; Jin S.; Kim D.; Chang S. Oxidatively Induced Reductive Elimination: Exploring the Scope and Catalyst Systems with Ir, Rh, and Ru Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 4137–4146. 10.1021/jacs.9b00364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baik M.-H.; Friesner R. A. Computing Redox Potentials in Solution: Density Functional Theory as A Tool for Rational Design of Redox Agents. J. Phys. Chem. A 2002, 106, 7407–7412. 10.1021/jp025853n. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui T.; Kitagawa Y.; Shigeta Y.; Okumura M. A Density Functional Theory Based Protocol to Compute the Redox Potential of Transition Metal Complex with the Correction of Pseudo-Counterion: General Theory and Applications. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2013, 9, 2974–2980. 10.1021/ct4002653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal R. G.; Kim H.-J.; Mayer J. M. Nanoparticle O–H Bond Dissociation Free Energies from Equilibrium Measurements of Cerium Oxide Colloids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 2896–2907. 10.1021/jacs.0c12799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welin E. R.; Le C.; Arias-Rotondo D. M.; McCusker J. K.; MacMillan D. W. C. Photosensitized, Energy Transfer-mediated Organometallic Catalysis Through Electronically Excited Nickel(II). Science 2017, 355, 380–385. 10.1126/science.aal2490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene F. D.; Misrock S. L.; Wolfe J. R. The Structure of Anthracene Photodimers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1955, 77, 3852–3855. 10.1021/ja01619a051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh I.; Shaikh R. S.; König B. Sensitization-Initiated Electron Transfer for Photoredox Catalysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 8544–8549. 10.1002/anie.201703004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee A.; König B. Birch-Type Photoreduction of Arenes and Heteroarenes by Sensitized Electron Transfer. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 14289–14294. 10.1002/anie.201905485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchini M.; Bergamini G.; Cozzi P. G.; Ceroni P.; Balzani V. Photoredox Catalysis: The Need to Elucidate the Photochemical Mechanism. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 12820–12821. 10.1002/anie.201706217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh I.; Bardagi J. I.; König B. Reply to “Photoredox Catalysis: The Need to Elucidate the Photochemical Mechanism. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 12822–12824. 10.1002/anie.201707594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coles M. S.; Quach G.; Beves J. E.; Moore E. G. A Photophysical Study of Sensitization-Initiated Electron Transfer: Insights into the Mechanism of Photoredox Activity. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 9522–9526. 10.1002/anie.201916359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser F.; Kerzig C.; Wenger O. S. Sensitization-initiated electron transfer via upconversion: mechanism and photocatalytic applications. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 9922–9933. 10.1039/D1SC02085D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda M.; Matsuzaki Y.; Shima K.; Pac C. Photochemical reactions of aromatic compounds. Part 44. Mechanisms for direct photoamination of arenes with ammonia and amines in the presence of m-dicyanobenzene. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2 1988, 2, 745–751. 10.1039/p29880000745. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Periana R. A.; Bergman R. G. Isomerization of the Hydridoalkylrhodium Complexes Formed on Oxidative Addition of Rhodium to Alkane Carbon-hydrogen Bonds. Evidence for the Intermediacy of η2-Alkane Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986, 108, 7332–7346. 10.1021/ja00283a032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Churchill D. G.; Janak K. E.; Wittenberg J. S.; Parkin G. Normal and Inverse Primary Kinetic Deuterium Isotope Effects for C–H Bond Reductive Elimination and Oxidative Addition Reactions of Molybdenocene and Tungstenocene Complexes: Evidence for Benzene σ-Complex Intermediates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 1403–1420. 10.1021/ja027670k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury A. D.; Houben K.; Whiting G. T.; Chung S.-H.; Baldus M.; Weckhuysen B. M. Electrophilic Aromatic Substitution Over Zeolites Generates Wheland-type Reaction Intermediates. Nat. Catal. 2018, 1, 23–31. 10.1038/s41929-017-0002-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan J. M.; Stryker J. M.; Bergman R. G. A structural, kinetic and thermodynamic study of the reversible thermal carbon-hydrogen bond activation/reductive elimination of alkanes at iridium. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986, 108, 1537–1550. 10.1021/ja00267a025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Okada S.; Okinaka K.; Iwawaki H.; Furugori M.; Hashimoto M.; Mukaide T.; Kamatani J.; Igawa S.; Tsuboyama A.; Takiguchi T.; Ueno K. Substituent Effects of Iridium Complexes for Highly Efficient Red OLEDs. Dalton Trans. 2005, 1583–1590. 10.1039/b417058j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G.; Li P.; Zhuang X.; Ye K.; Liu Y.; Wang Y. Rational Design and Characterization of Heteroleptic Phosphorescent Complexes for Highly Efficient Deep-Red Organic Light-Emitting Devices. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 11749–11758. 10.1021/acsami.7b00348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.