Abstract

Present-day people from England and Wales harbour more ancestry derived from Early European Farmers (EEF) than people of the Early Bronze Age1. To understand this, we generated genome-wide data from 793 individuals, increasing data from the Middle to Late Bronze and Iron Age in Britain by 12-fold, and Western and Central Europe by 3.5-fold. Between 1000–875 BCE, EEF ancestry increased in southern Britain (England and Wales) but not northern Britain (Scotland) due to incorporation of migrants who arrived at this time and over previous centuries, and who were genetically most similar to ancient individuals from France. These migrants contributed about half the ancestry of Iron Age people of England and Wales, thereby creating a plausible vector for the spread of early Celtic languages into Britain. These patterns are part of a broader trend of EEF ancestry becoming more similar across Central and Western Europe in the Middle to Late Bronze Age, coincident with archaeological evidence of intensified cultural exchange2–6. There was comparatively less gene flow from continental Europe during the Iron Age, and Britain’s independent genetic trajectory is also reflected in the rise of the allele conferring lactase persistence to ~50% by this time compared to ~7% in Central Europe where it rose rapidly in frequency only a millennium later. This suggests that dairy products were used in qualitatively different ways in Britain and in Central Europe over this period.

Whole genome ancient DNA studies have shown that the first Neolithic farmers of the island of Great Britain (hereafter Britain) who lived 3950–2450 BCE derived roughly 80% of their ancestry from Early European Farmers (EEF) who originated in Anatolia more than two millennia earlier, and 20% from Mesolithic hunter-gatherers (Western European Hunter-Gatherers: WHG) with whom they mixed in continental Europe, indicating that local WHG in Britain contributed negligibly to later populations7–9. This ancestry profile remained stable for about a millennium and a half. From around 2450 BCE, there was another substantial migration (Box 1) into Britain (minimum 90% ancestry from the new migrants) coinciding with the spread of Bell Beaker traditions from continental Europe which brought a third major component: ‘Steppe ancestry’ derived originally from people living on the Pontic-Caspian Steppe ~3000 BCE8. In the original study8 reporting this ancestry shift in Britain, no significant average change in the proportion of EEF ancestry was detected from the Chalcolithic/Early Bronze Age (C/EBA; 2450–1550 BCE), through the Middle Bronze Age (MBA; 1550–1150 BCE) and Late Bronze Age (LBA; 1150–750 BCE), to the pre-Roman Iron Age (IA; 750 BCE-43 CE). However, that study contained little data after 1300 BCE (Fig. 1). Today, however, EEF ancestry is significantly higher on average in southern Britain than in northern Britain, raising the question of when this increase occurred1,8. The rise in EEF ancestry cannot be explained by migration from northern continental Europe in the early medieval period, as early medieval migrants harboured less EEF ancestry than in Bronze Age Britain10 and hence would have decreased EEF ancestry instead of increasing it as we observe1.

Box 1. Reconciling archaeological and genetic understandings of “migration”.

“Migration” is a central concept in both population genetics and archaeology, but its meaning has evolved in divergent ways in the course of the development of these disciplines27. Population geneticists use “migration” to refer to any movement of genetic material from one region to another which would see even low-level symmetrical exchanges of mates between adjacent communities as representing migration, while archaeologists restrict its use to processes that result in significant demographic change due to permanent translocation of people from one region to another28. In European archaeology, discussions of prehistoric migrations have become fraught due to the ways in which theories of migration were exploited politically in the early-mid twentieth century, when movement of large numbers of people over short times was sometimes argued to be a primary mechanism for the spread of ethnic groups and archaeological reconstructions of such events were used to justify claims on territory29. Because of this, some archaeologists prefer to set a high bar for theorizing migration, for example by restricting its use to cases where there is evidence for organized movements of people over a short time. However, this can make it difficult to recognize the important effects that large-scale movements of people had in prehistory28, such as the westward movement of people from the Steppe beginning in the third millennium BCE that genetic data have shown contributed much of the ancestry of later Europeans8,30. We use the term “migration” here with intention, because the movement of people into Britain we document was demographically transformative. We emphasize that our findings are not sufficient to prove mass movement over a short time; indeed our radiocarbon dating and isotopic evidence shows that at least some of the migration was drawn out over hundreds of years.

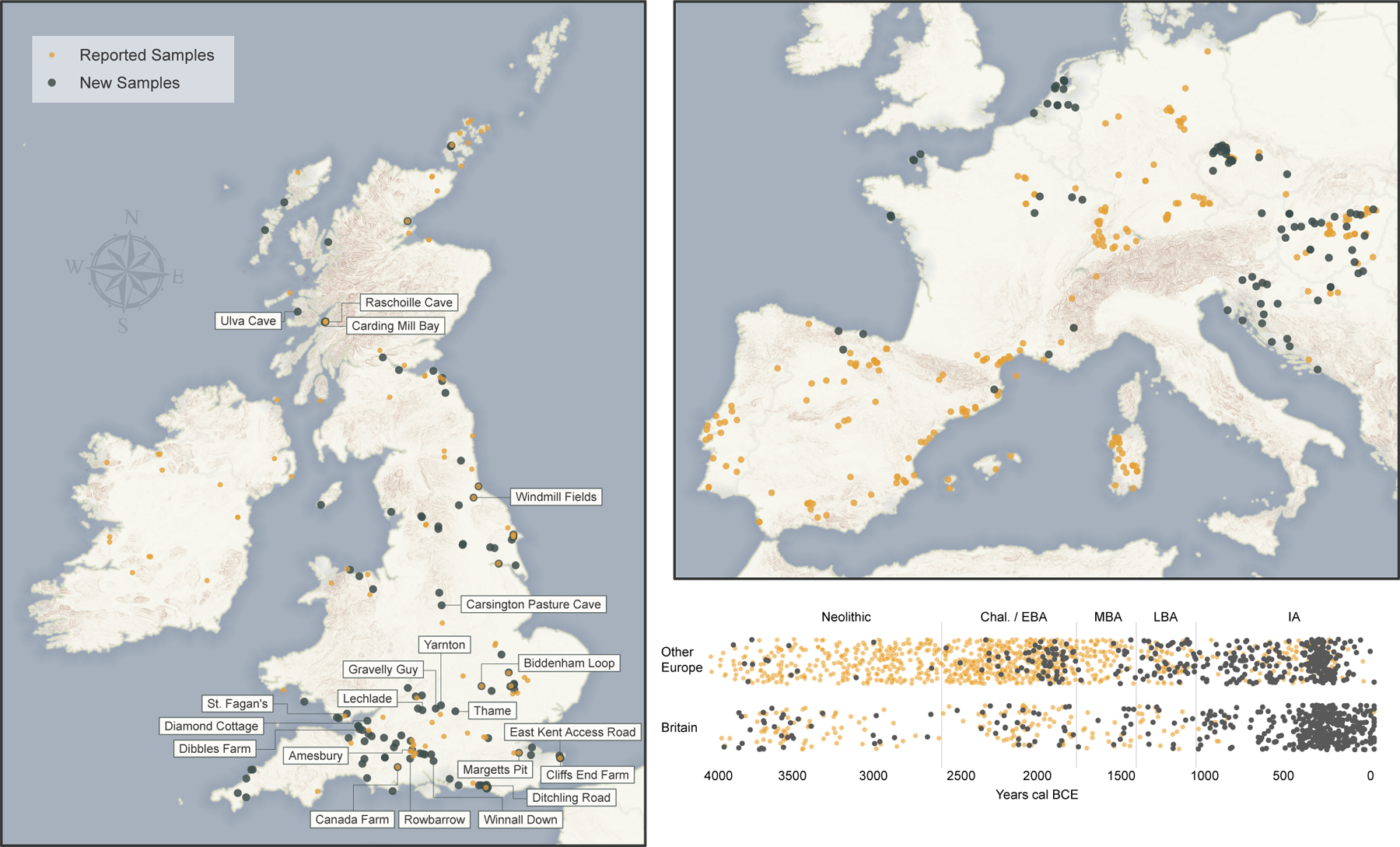

Fig. 1: Ancient DNA Dataset.

Geographic distribution of sites and temporal distribution of individuals 4000 BCE-43 CE. Newly reported in black; published in orange. Base maps made with Natural Earth; elevation data Copernicus, European Digital Elevation Model v1.1. The Britain map labels sites harbouring ancestry outliers relative to others of the same period. The timeline shows archaeological periods in the British chronology: Neolithic (3950–2450 BCE), Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Age (C/EBA, 2450–1550 BCE), Middle Bronze Age (MBA, 1550–1150 BCE), Late Bronze Age (LBA, 1150–750 BCE), and pre-Roman Iron Age (IA, 750 BCE-43 CE). We add jitter on the Y axis and sample dates from their probability distributions (Supplementary Table 1).

We generated genome-wide ancient DNA data from 416 previously unanalysed individuals from Britain, increasing the number of pre-Roman individuals to 598 and multiplying by 28-fold the number from the combined period of the LBA and IA (from 13 to 365) (Fig. 1, Supplementary Information section 1, Supplementary Table 1, Methods). We also report data from ancient individuals mostly dating to the LBA and IA from the Czech Republic (n=160), Hungary (n=54), France (n=52), the Netherlands (n=28), Slovakia (n=25), Croatia (n=21), Slovenia (n=14), Spain (n=10), Serbia (n=8) and Austria (n=3). We increased data quality on 33 previously published individuals (Supplementary Table 1). To generate these data (Methods), we prepared powder from bones and teeth, extracted DNA, and generated 1020 sequencing libraries all pretreated with uracil-DNA glycosylase to reduce characteristic cytosine-to-thymine errors of ancient DNA (Supplementary Table 2). We enriched libraries in solution for a targeted set of more than 1.2 million single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), sequenced them, then co-analysed with previously reported data (Supplementary Table 3). We clustered by time and geography aided by 123 newly reported radiocarbon dates (Supplementary Table 4). We separately labelled individuals that were significantly different in ancestry from the majority cluster from each time period and region (Supplementary Information section 2, Supplementary Table 5). Although we report data from all individuals, we removed a subset from the main analysis: those with evidence of contamination, those with a rate of damage in the final nucleotide lower than the typical range for authentic ancient DNA, those that were first degree relatives of other higher coverage individuals in the dataset, or those with too little data for accurate ancestry inference (<30,000 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) covered at least once) (Supplementary Table 5, Methods). Fig. 1 shows a map of analysed individuals. We identified 123 individuals from 48 families as related (within the third degree) to at least one other newly reported individual in the dataset (Supplementary Table 6).

British ancient DNA time transect

We computed f4-statistics with Block Jackknife standard errors11 between all pairs of temporal groupings of individuals in Britain, testing for differences in the rate of allele sharing (genetic drift) with the two major source populations (Steppe and EEF). We document a significant increase in the degree of allele sharing with EEF populations in England and Wales over the M-LBA and into the IA (Extended Data Table 1). To estimate the proportions of EEF, Steppe, and WHG ancestry, we used qpAdm12, which takes advantage of the fact that if a “Target” population is a mixture of “Source” populations for which we have close surrogates in our dataset, we can compute all possible f4-statistics relating the “Targets” and “Sources” to a set of chosen outgroups, and then use qpAdm to find the values of the mixture coefficients , and that fit all the statistics, while also providing a p-value for whether the “Target” population can in fact be modelled as a mixture of close relatives of the “Sources”. We carefully chose our set of “Sources” and “Outgroups” to provide much more accurate inferences than previous qpAdm setups due to their large sample sizes and the high degree of leverage they provide for teasing apart the three major components of European ancestry (Supplementary Information section 2). Our proxies for the “Sources” are 22 early Balkan Neolithic farmers with minimal hunter-gatherer admixture (EEF), 20 Yamnaya and Poltavka pastoralists (Steppe), and 18 Mesolithic hunter-gatherers from across Western Europe (WHG). Our “Outgroups” are close genetic cousins of the three Sources—24 Anatolian Neolithic individuals related to EEF, 19 Afanasievo individuals related to Yamnaya Steppe pastoralists, and 41 hunter-gatherers largely from the Danubian Iron Gates related to WHG—and a pool of 9 ancient sub-Saharan Africans processed using the same in-solution enrichment technology and without evidence of West Eurasian-related admixture.

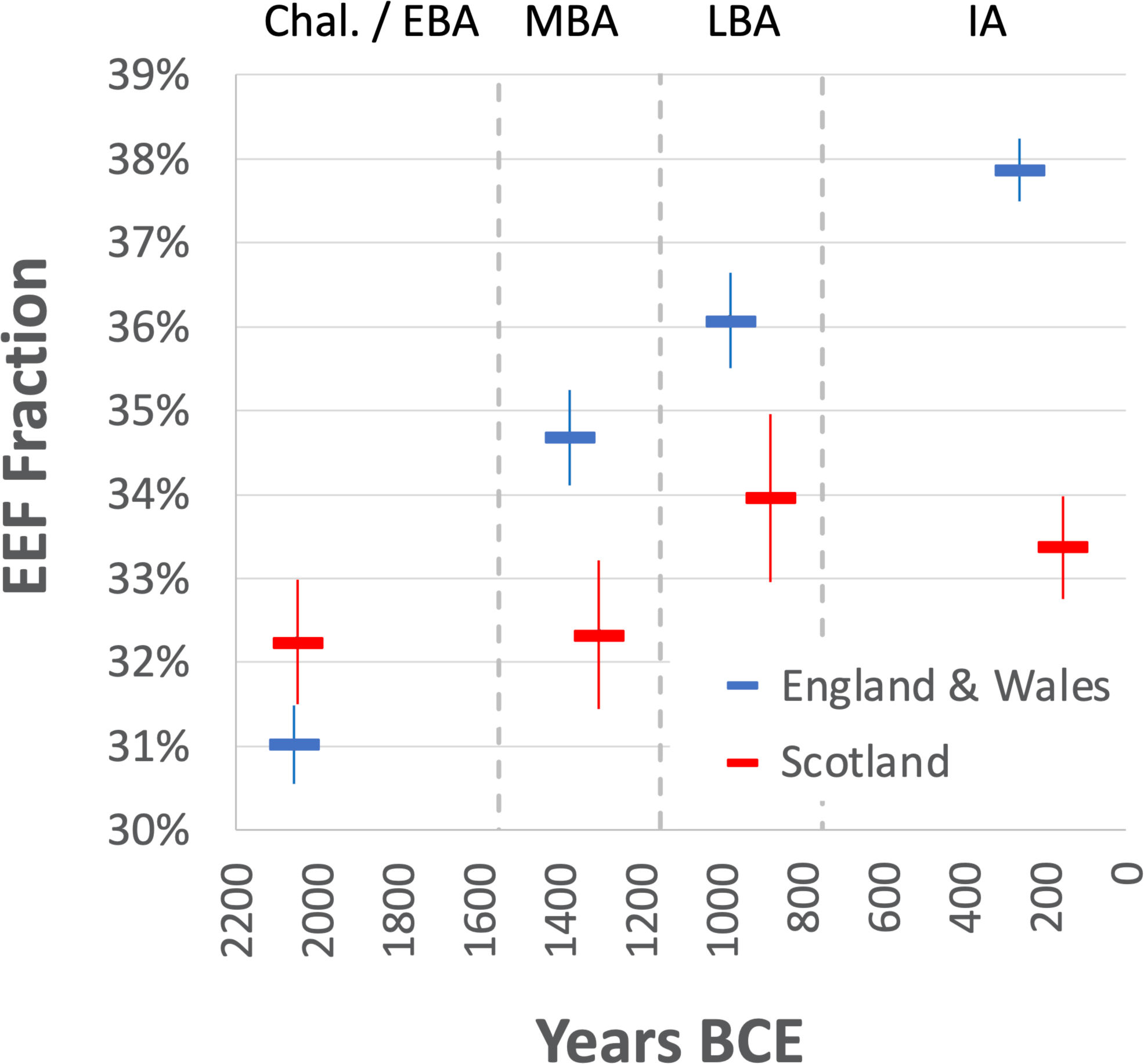

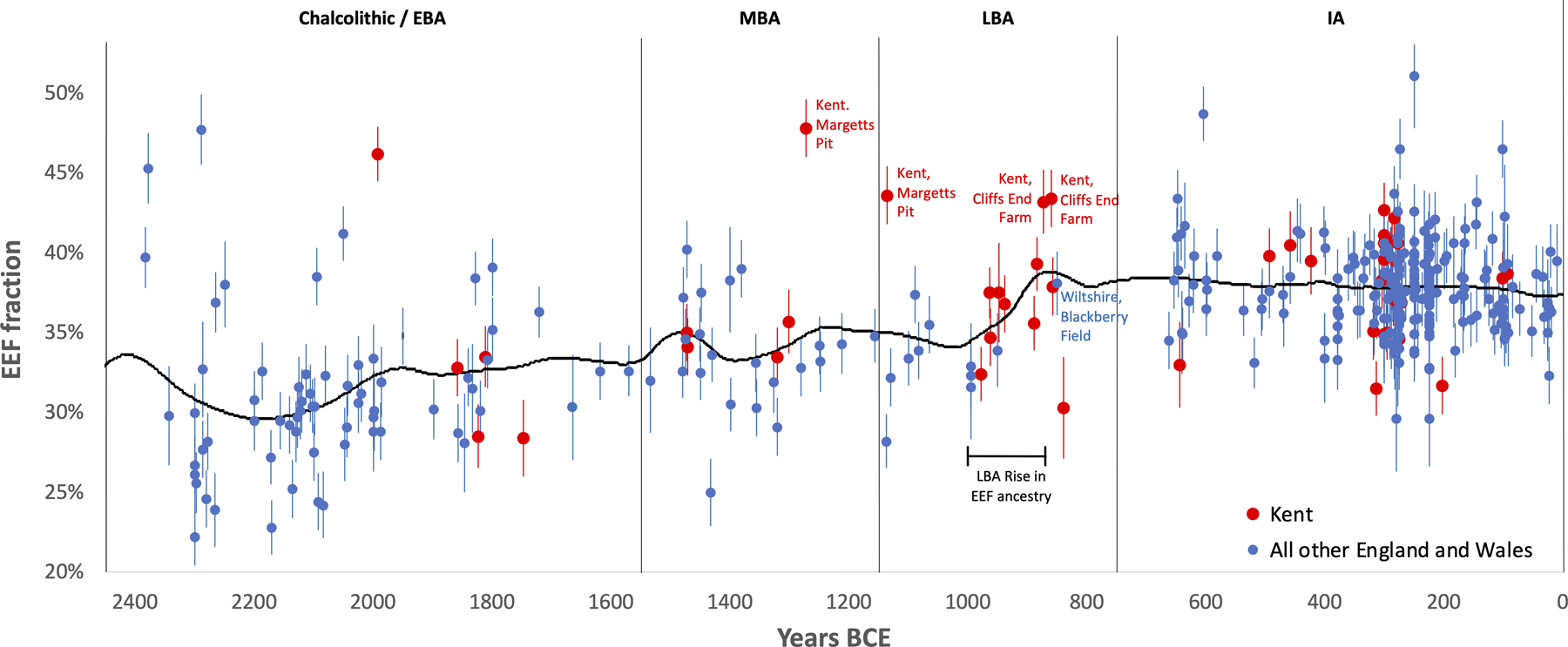

EEF-related ancestry increased in England and Wales from 31.0±0.5% in the C/EBA (n=69), to 34.7±0.6% in the MBA (n=26), to 36.1±0.6% in the LBA (n=23), and stabilized at 37.9±0.4% in the IA (n=273) (here and below, we quote one standard error). There was no significant change in Scotland (Fig. 2 and Extended Data Table 1). Increased EEF ancestry was widespread in southern Britain by the IA, with point estimates ranging from 36.0–38.8% across eight regions of England (Wales sample sizes are too small to provide accurate inference) (Table 1, Extended Data Table 2). We considered the possibility that the rise in EEF ancestry in southern Britain was due to a resurgence of archaeologically less visible populations with more ancestry from people living in Britain in the Neolithic, which we missed either due to geographic biases in sampling, or variation across cultural contexts in the way groups treated their dead for example through cremation. However, models of IA people of England and Wales as a mixture of groups in Neolithic and C/EBA Britain failed at high significance (Extended Data Fig. 1). This is due to IA populations in Britain sharing alleles with some Neolithic populations in continental Europe that was not present in early Neolithic or C/EBA groups in Britain (Supplementary Information section 3). The most plausible explanation for these patterns is migration of people carrying this distinctive ancestry into southern Britain in the M-LBA.

Fig. 2: Increase in EEF ancestry during the Middle to Late Bronze Age.

EEF ancestry increased in southern Britain beginning with the Margetts Pit MBA outliers but hardly in the north. Estimates from qpAdm are binned into four archaeological periods. We plot means and one standard error from a Block Jackknife. Sample sizes in the C-EBA/MBA/LBA/IA are 69/26/23/273 in England and Wales and 10/5/4/18 in Scotland.

Table 1:

Regional variation in ancestry in Iron Age Britain

| Latitude | Modeling Ancestry With Pre-Bronze Age Sources | With Middle to Late Bronze Age Sources | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region | N | P | WHG | EEF | Steppe | P | Continental | |

|

| ||||||||

| Scotland | ||||||||

| Orkney | 2 | 59 | 0.22 | 14.2±1.1% | 34.1±1.2% | 51.6±1.6% | 0.10 | 20±9% |

| West | 4 | 58 | 0.12 | 13.0±.8% | 32.3±1.0% | 54.7±1.2% | 0.19 | 8±7% |

| Southeast | 12 | 56 | 0.67 | 12.1±.6% | 33.9±.7% | 54.0±.9% | 0.39 | 16±5% |

|

| ||||||||

| England | ||||||||

| North | 10 | 54 | 0.35 | 13.4±.6% | 36.3±.8% | 50.3±1.0% | 0.76 | 35±5% |

| E. Yorkshire | 47 | 54 | 0.61 | 13.2±.4% | 37.0±.5% | 49.8±.6% | 0.86 | 44±4% |

| Midlands | 18 | 53 | 0.66 | 12.6±.5% | 36.0±.6% | 51.4±.8% | 0.77 | 36±4% |

| Southwest | 84 | 53 | 0.30 | 13.7±.4% | 38.7±.4% | 47.6±.6% | 0.56 | 55±5% |

| East Anglia | 21 | 52 | 0.44 | 13.5±.5% | 37.0±.5% | 49.5±.7% | 0.52 | 44±4% |

| Southcentral | 38 | 52 | 0.32 | 13.9±.4% | 38.8±.5% | 47.2±.6% | 0.35 | 56±5% |

| Southeast | 3 | 51 | 0.13 | 13.9±.5% | 38.3±.5% | 47.8±.6% | 0.40 | 52±5% |

| Cornwall | 16 | 50 | 0.40 | 13.5±.5% | 36.4±.7% | 50.1±.8% | 0.64 | 39±5% |

|

| ||||||||

| Wales | ||||||||

| North | 1 | 53 | 0.20 | 12.1±1.6% | 34.7±2.0% | 53.2±2.5% | 0.53 | 22±14% |

| South | 2 | 51 | 0.66 | 14.2±1.2% | 38.6±1.5% | 47.2±1.8% | 0.57 | 53±11% |

Notes: Regions are ordered first by large grouping (Scotland-England-Wales), then latitude. We separate “England East Yorkshire” from “England North” because of distinctive cultural context in the IA (Arras). For the final two columns, we use as the Britain source Britain_C.EBA and as the continental source Margetts Pit / Cliffs End Farm pool.

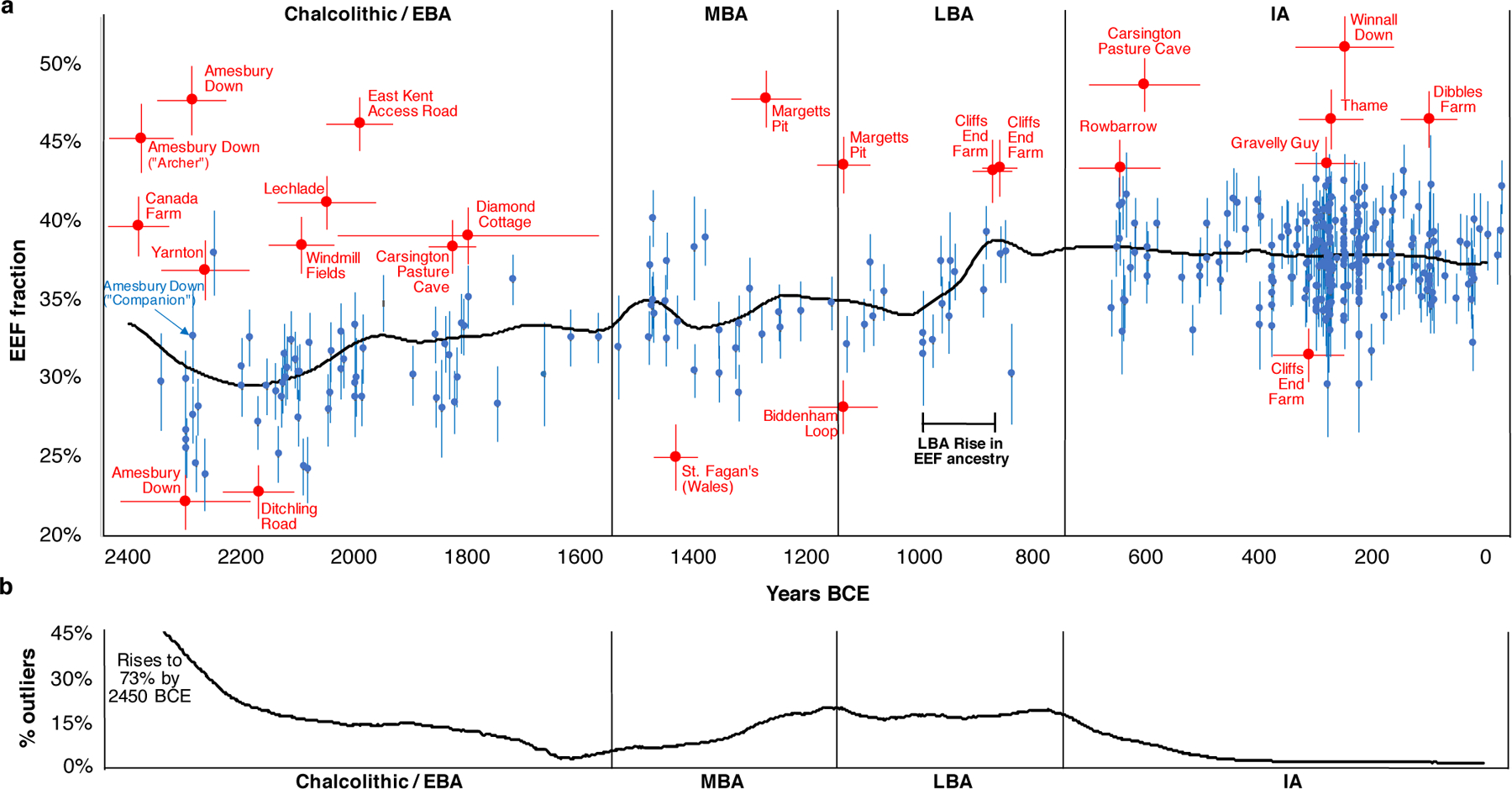

We modelled ancestry in each individual, labelling significant ancestry outliers relative to most individuals of their period. We highlight key observations (Fig. 3, Extended Data Fig. 2).

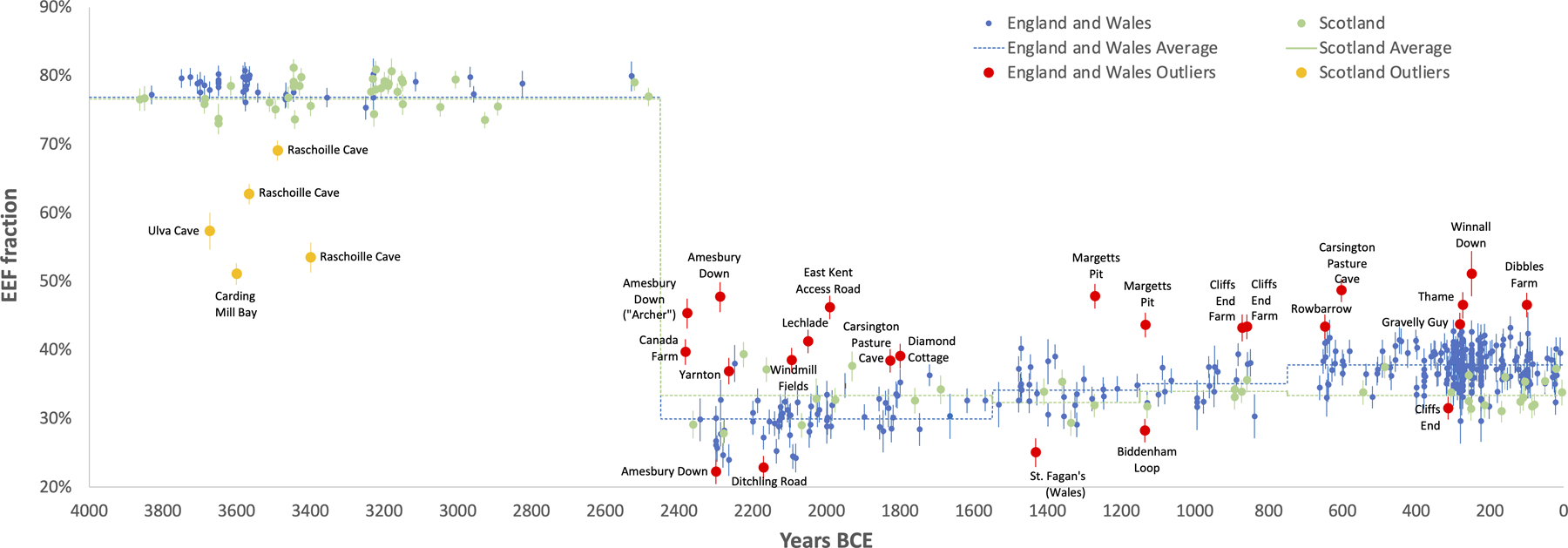

Fig. 3: By-individual analysis of the southern Britain time transect.

(A) Estimates of EEF ancestry and one standard error for all individuals fitting a three-way admixture model (EEF + WHG + Yamnaya) at p>0.01 using qpAdm; we restrict to 2450 BCE-43 CE using the best date estimate from Supplementary Table 5. Most individuals are in blue, while significant outliers at the ancestry tails are in red (outliers are identified as p<0.005 based on a qpWave test from the main cluster from their period and |Z|>3 for a difference in EEF proportion, or p<0.1 and |Z|>3.5). We use a horizontal bar to show one standard error for the date (Supplementary Table 5). The black line shows population-wide EEF ancestry at each time obtained by weighting each individual’s EEF estimate by the inverse square of their standard error and the probability that their date falls at that time (based on the mean and standard error in Supplementary Table 5 assuming normality; we filter out individuals with standard errors >120 years). The incorporation of increased EEF ancestry into the majority of individuals occurred ~1000–875 BCE. (B) Proportion of outliers over 300-year sliding windows centered on each point, based on randomly sampling dates of all individuals 100 times assuming normality and their mean and standard deviation in Supplementary Table 5 (removing individuals with EEF errors >0.022 and date errors >120 years). Major epochs of migration into Britain are periods with elevated proportions of outliers: between 2450–1800 BCE (17% outliers) and 1300–750 BCE (17% again). The fact that there was an elevated rate of outliers prior to the 1000–875 BCE population-wide rise in EEF ancestry may reflect a delay between the time of arrival of migrants and their full incorporation into the population.

First, replicating previous results8,9, we infer a cluster of Neolithic individuals from western Scotland with high WHG admixture, likely reflecting unions between recent migrants from Europe and descendants of local Mesolithic groups in Britain (Extended Data Fig. 2).

Second, we infer high variability in EEF ancestry in the C/EBA, before EEF ancestry became relatively homogeneous after ~2000 BCE8 (Fig. 3). This is apparent at Amesbury Down where EEF ancestry in some burials is significantly below the average of 29.9±0.4% (e.g. I2417 at 22.2±1.8%), plausibly reflecting Beaker-period migrants who mixed with local Neolithic farmers to produce the intermediate EEF ancestry that prevailed by the end of the EBA. Others are above the group average including individual I14200 at 45.3±2.2%, known as the “Amesbury Archer,” who was buried in the most well-furnished grave recovered from the Stonehenge mortuary landscape and had an isotopic profile indicating that he spent parts of his childhood outside Britain, possibly in the Alps13. The fact that the Archer was a migrant but had too little Steppe ancestry to be from the population that drove Steppe ancestry to the level observed in C/EBA Britain, shows that Beaker-associated migrants to Britain were not genetically homogeneous. The ‘Companion’ (I2565), a burial found next to the Archer whose isotopic profile like most others at the site was consistent with a local upbringing, was not an ancestry outlier (32.7±3.0% EEF; Fig. 3). The Archer and the Companion shared a rare tarsal morphology and similar grave goods, hypothesized to reflect close genetic relationship (Supplementary Information section 4)14, but our results rule out first- or second-degree relatedness.

Third, we observe four outliers with high EEF ancestry in the late MBA and LBA who are candidates for being first generation migrants or the offspring of recent migrants, all of whom were buried in Kent in the southeasternmost part of Britain. The earlier two are from Margetts Pit: 47.8±1.8% in individual I13716 (1391–1129 calBCE) and 43.6±1.8% in I13617 (1214–1052 calBCE). The latter two are from Cliffs End Farm: 43.2±2.0% in individual I14865 (967–811 calBCE) and 43.4±1.8% in I14861 (912–808 calBCE). We considered the possibility that we are observing the effect of a short burst of migration in the MBA which included the Margetts Pit outliers, followed by co-existence of separate communities with different EEF ancestry for at least a couple of hundred years, including the Cliffs End Farm outliers. However, strontium and oxygen isotope analyses identify multiple individuals of non-local origin at Cliffs End Farm15, including outlier I14861, suggesting that this was not a single mass migration but instead a stream of migrants over hundreds of years (Supplementary Information section 5).

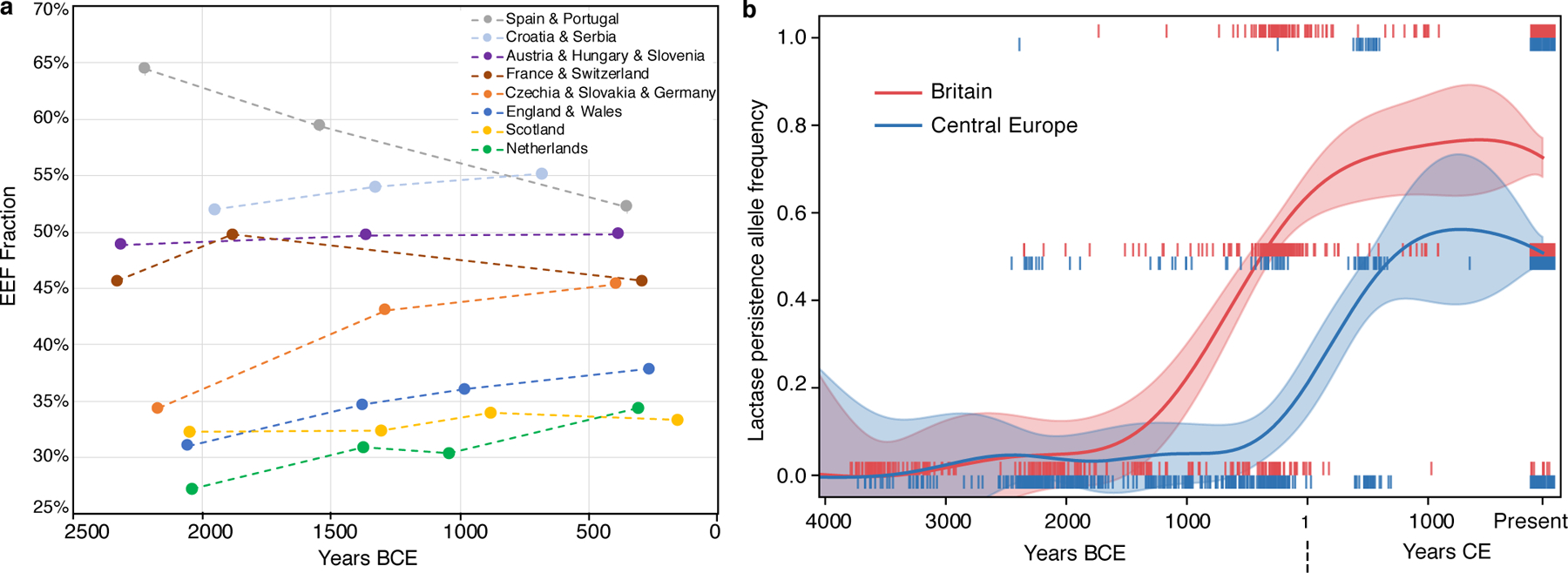

Fourth, the fraction of individuals whose ancestry is significantly different from the main group is 17% over the first part of the C/EBA (2450–1800 BCE), 4% from the end of the EBA through the beginning of the MBA (1800–1300 BCE), 17% from the end of the MBA through the LBA (1300–750 BCE), and 3% through the IA (Fig. 3). This is consistent with two periods of relatively high rates of migration into southern Britain in the Chalcolithic and then again in the M-LBA. We considered the possibility that our failure to observe a high rate of outliers in the IA compared with the preceding period was because ancestry had, by this time, homogenized to some extent between Britain and continental regions, which could make outliers more difficult to detect. However, average EEF ancestry in Britain in the IA was 37.9±0.4%, substantially different from much of contemporary Western and Central Europe—52.6±0.6% in Iberia, 49.8±0.4% in Austria, Hungary, and Slovenia, 45.4±0.5% in the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Germany, 45.6±0.5% in France and Switzerland, and 34.4±1.2% in the Netherlands (Fig. 4A)—which would have made the majority of migrants from these regions detectable given the <2% standard errors in most of our ancestry estimates (Supplementary Table 5). Our sampling from western France and Belgium is poor, and it is possible that EEF ancestry proportions there were similar to Britain, so we cannot rule out migration from this region in the IA. Nevertheless, our results are consistent with reduced migration from continental Europe and suggest a substantial degree of genetic isolation of Britain from much of continental Europe during the IA16.

Fig. 4: Genetic change in Britain in the context of Europe-wide trends.

(A) Eight ancient DNA time transects for up to four periods, plotting the mean of the EEF inference on the y-axis and on the x-axis using the average of dates of individuals in periods defined for each region as in Supplementary Table 5. Sample sizes used to compute each point are given in Supplementary Table 7. Dotted lines connecting points should not be interpreted as implying a smooth change over time and instead are meant to help in visual discernment of which groups of points come from the same time transects. (B) The allele conferring lactase persistence experienced its major rise about a frequency millennium earlier in Britain than in Central Europe suggesting different selection regimes and possibly cultural differences in the use of dairy products in the two regions in the IA. This analysis based on imputed data includes 459 ancient individuals from Britain and 468 from Central Europe (Czech Republic, Slovakia, Croatia, Hungary, Austria, Germany and Slovenia) (we then co-analyzed with present-day individuals; Methods). Each vertical bar represents the derived allele frequency for each individual with values [0, 0.5, 1]; we use jitter on the x-axis, and show in shading the inferred 95% confidence interval for the allele frequency at each time point.

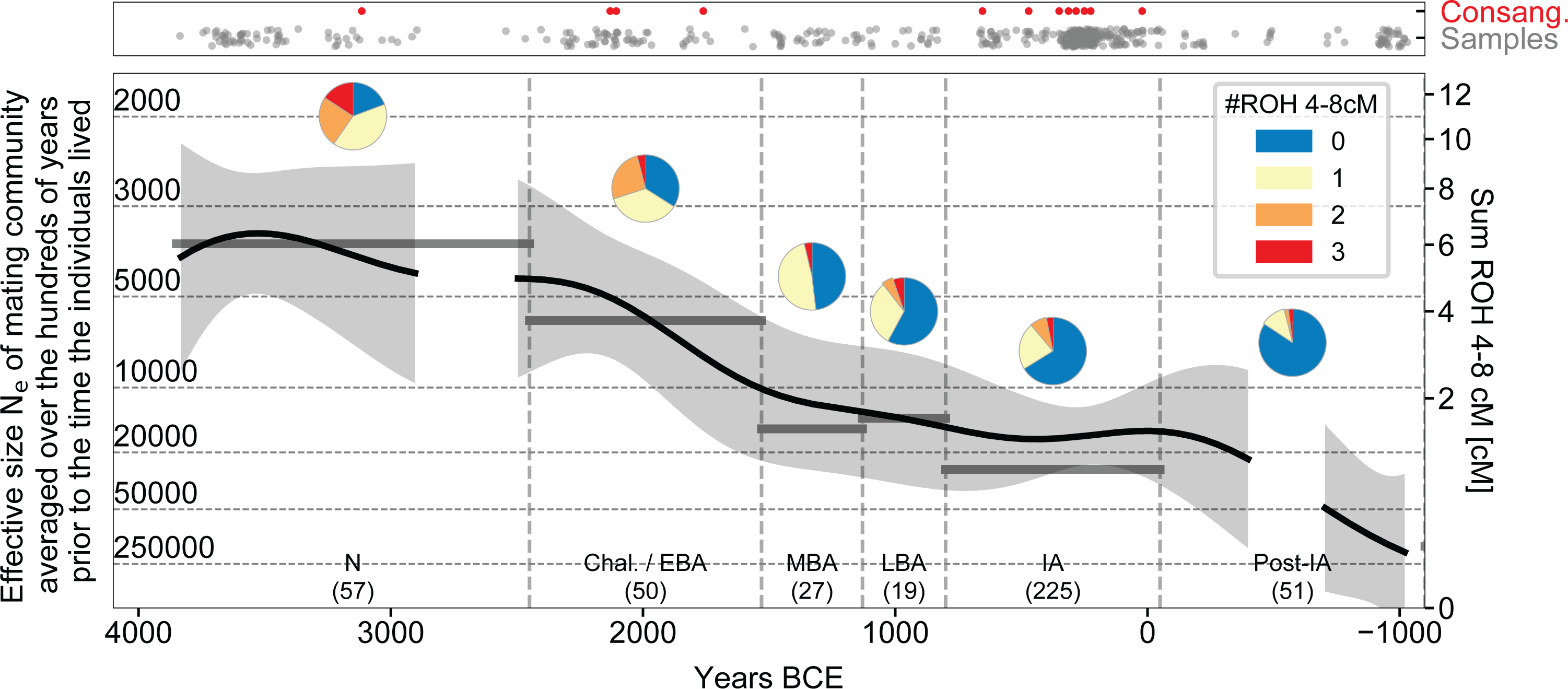

Demographic change in Britain is also evident from another aspect of the data: the rate of runs of homozygosity (ROH), which can occur when a person’s parents are closely related. The larger the pool of people from which individuals draw their mates, the less likely it is for parents to be closely related, and thus we can average the number of 4–8 centimorgan (cM) ROH segments to estimate the effective size of the pool of people within which people were mating in the ~600 year period prior to the time when the analysed individuals lived17. We find that the size of the mating pool increased by roughly four-fold from the Neolithic to the IA (Extended Data Fig. 3), but this should not be interpreted as an estimate of census population size changes over this period as mating pool sizes are also affected by changing social customs. First, if the distance over which people ranged to find their mates was higher in some cultural contexts than in others, it would cause mating pool sizes to be different even if there was no difference in population densities; for example, mating pool size may have been less than the island-wide population size if members of communities mixed little with their neighbours16, or larger if individuals mated not only with people outside their local communities but also outside Britain. Second, we have gaps in sampling, especially at the end of the Neolithic (roughly 3000–2450 BCE), which means that demographic processes in such periods may be obscured. Third, due to the method effectively averaging mating pool size over centuries, this analysis may also fail to detect population declines over the space of a few decades.

British change in European context

We co-analysed our ancient DNA time transect in Britain alongside European transects (Fig. 4A, Supplementary Tables 5 and 7). Average EEF ancestry increased in North-Central Europe (Czech Republic/Slovakia/Germany) just as in Britain, with the first individuals with greatly increased EEF ancestry associated with artefacts traditionally classified as part of the Knoviz culture, a component of the broader Urnfield cultural complex (1300–800 BCE) that spread across much of Central Europe. This is particularly striking as the Knoviz individuals are from a population that is genetically similar to the Margetts Pit and Cliffs End Farm outliers (Supplementary Information section 6). Later individuals in North-Central Europe have similar EEF proportions, consistent with substantial continuity through the LBA-IA. In MBA and LBA France/Switzerland and South-Central Europe (Austria/Hungary/Slovenia) there was little change in average EEF ancestry, while EEF ancestry decreased in MBA and LBA Iberia (Spain/Portugal). There are two exceptions to this broad pattern of ancestry convergence in Europe—Scotland in the far north, and Sardinia in the far south—both of which have extreme and relatively unchanging proportions of EEF ancestry in this period (Supplementary Table 7).

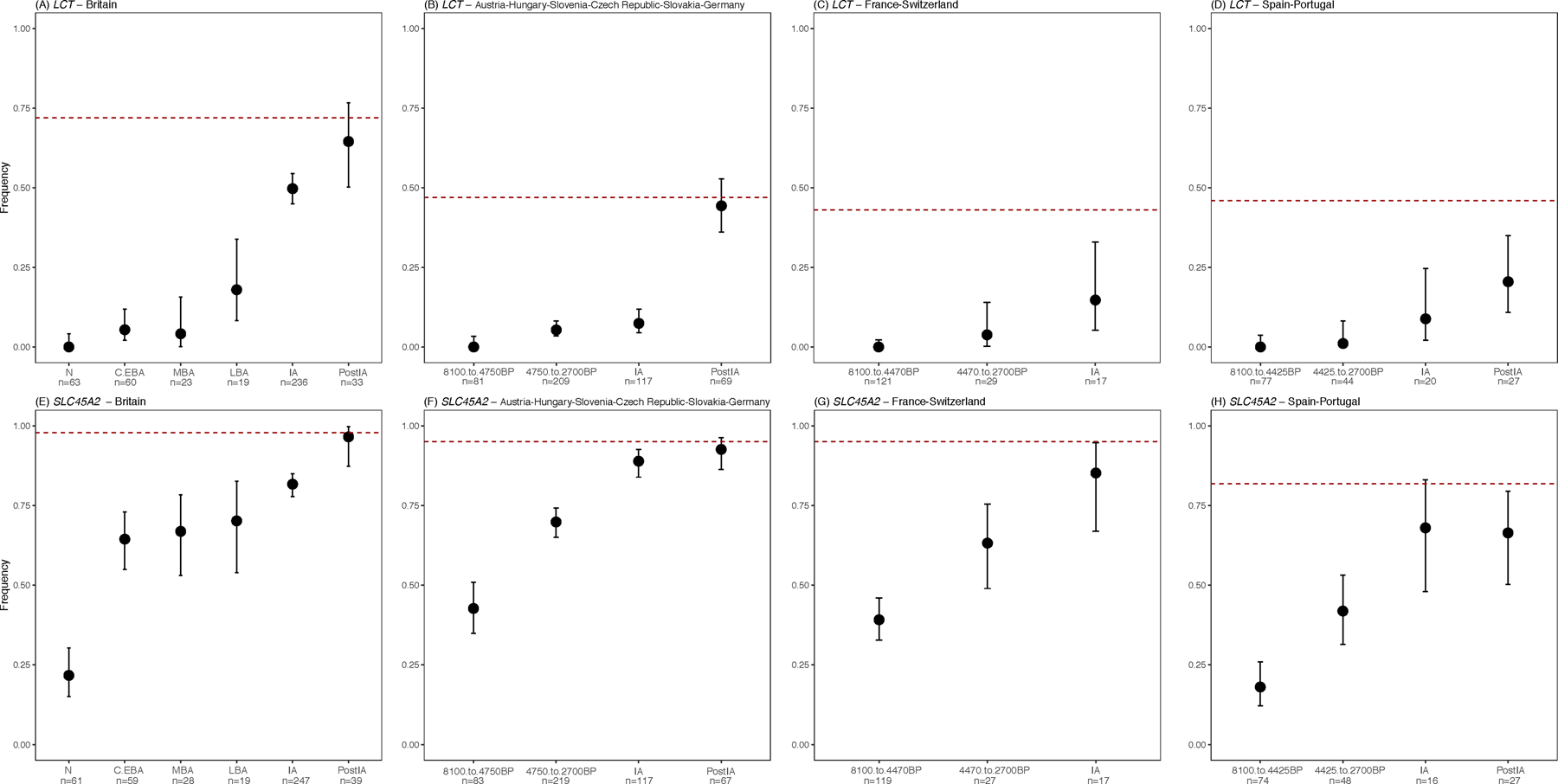

This study multiplies by almost eight-fold the number of IA individuals with genome-wide data from Western and Central Europe (from 80 to 624; Supplementary Table 5), making it possible to accurately track the frequency change of genetic variants into the IA (Supplementary Table 8). Variants associated with light skin pigmentation at SLC45A2 became substantially more common throughout Europe in the IA. We obtain an unexpected result for the derived allele at MCM6-LCT rs4988235 which is associated with lactase persistence into adulthood (Extended Data Fig. 4). Previous analyses found that its frequency in the IA in sampled parts of continental Europe was a small fraction of its present-day incidence18. We document this at high precision in our dataset in Iberia where it was ~9% compared to ~40% today, and in Central Europe (Austria, Hungary, Slovenia, Czech Republic, Slovakia and Germany) where it was ~7% compared to ~48% today. However, in IA Britain its frequency was 50% compared to the current 73%, showing that intense selection to increase the frequency of this allele acted roughly a millennium earlier in Britain than it did in multiple parts of continental Europe (Fig. 4B, Extended Data Fig. 4). We find no evidence that the frequency rise in Britain was due to M-LBA migration: the Margetts Pit and Cliffs End Farm outliers did not carry the allele, and most of the rise in Britain occurred after the M-LBA (Fig. 4B, Supplementary Table 8). This suggests that dairy products were consumed in a qualitatively different way or were economically more important in LBA-IA Britain than in Central Europe.

Continental sources of M-LBA migration

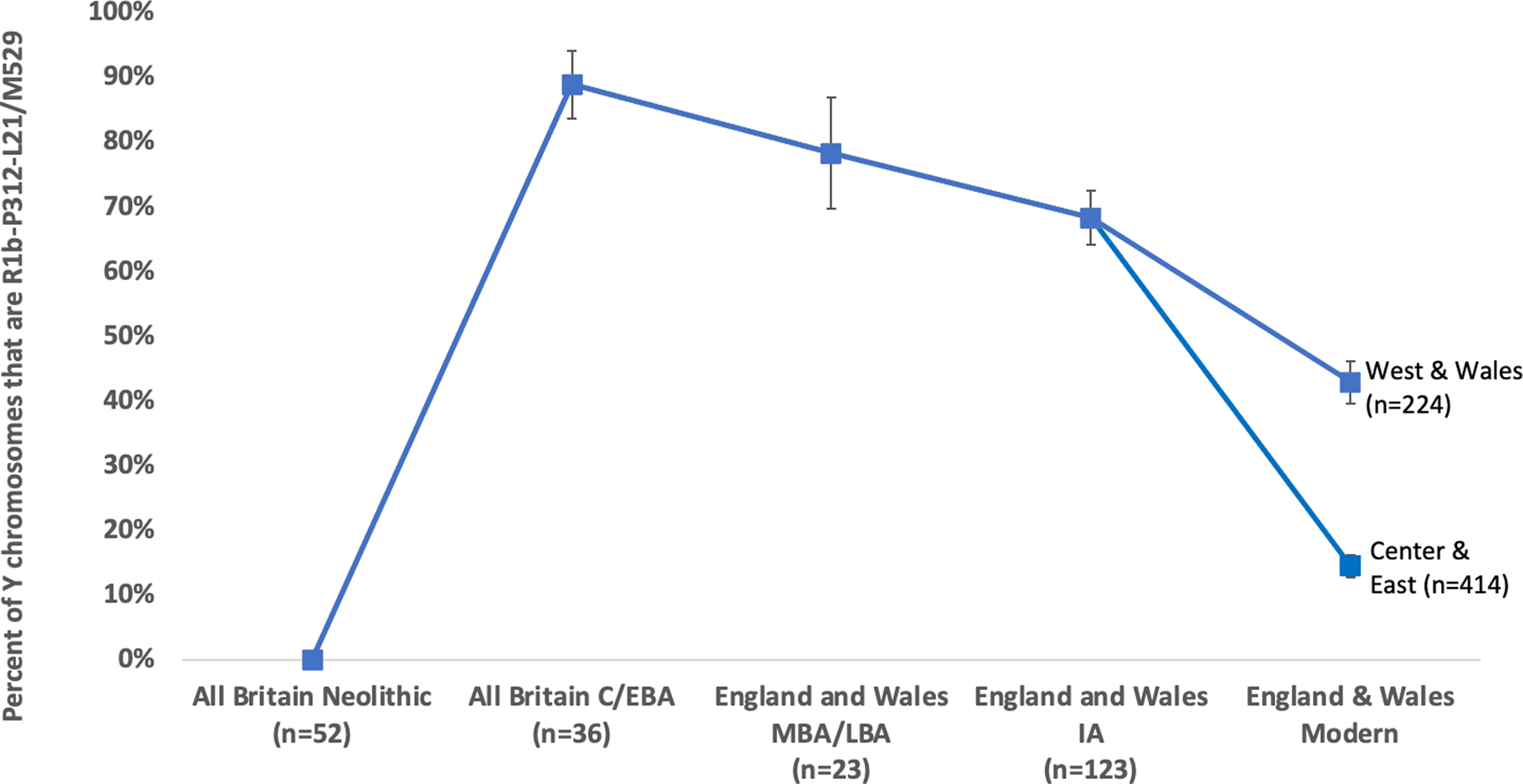

The ancestry change in Britain during the M-LBA was more subtle than those associated with the Neolithic and Beaker-period migrations. In England and Wales, allele frequency differentiation between the Neolithic and C/EBA was FST~0.02, but between the C/EBA and the IA it was an order of magnitude smaller at FST~0.002 (Extended Data Table 1). The pre-LBA population in Britain also made a substantial genetic contribution to the IA population, in contrast to the two earlier major Holocene ancestry shifts8,9. Evidence for a substantial contribution from the C/EBA population to later populations also comes from Y chromosome haplogroup R1b-P312/L21/M529 (R1b1a1a2a1a2c1), which is present at 89±5% in sampled individuals from C/EBA Britain and is nearly absent in available ancient DNA data from C/EBA Europe (Supplementary Table 9). The haplogroup remained more common in Britain than in continental Europe in every later period, and continues to be a distinctive feature of the British isles as its frequency in Britain and Ireland today (14–71% depending on region19) is far higher than anywhere else in continental Europe (Extended Data Fig. 5).

To gain insight into the possible sources of the M-LBA migrants to southern Britain, we fit the pooled IA individuals from England and Wales in qpAdm as a mixture of the main C/EBA cluster, and a second source. We tested 65 second sources—63 from continental Europe and 2 from Britain (the Margetts Pit outlier pool, and the Cliffs End Farm outlier pool)—and found that 20 fit at p>0.05. We then pooled the genetically similar Margetts Pit and Cliffs End Farm individuals and performed further testing with more stringent qpAdm setups, leaving eight second sources that consistently fit well with modest standard errors (Table 2, Supplementary Information section 6). The Margetts Pit and Cliffs End Farm pool fit as contributing 49.4±3.0% of the ancestry of IA people from southern Britain. Even omitting representatives of the putative source population living in Britain itself, we infer large genetic turnovers, as the seven continental populations that fit as sources are estimated to contribute 24–69% ancestry. Although only 1/5th of the continental candidate populations we tested are from France, 6/7th’s of the fitting populations are: four from Occitanie in southern France (600–200 BCE), two from Grand Est in northeastern France (800–200 BCE), and one from Spain (a ~600 BCE group). These fitting second sources all significantly post-date the ancestry change in Britain and hence cannot be the true sources; however, they are plausibly descended from earlier local populations. An origin in France is also suggested by the fact that all of the high EEF outliers in Britain in the M-LBA, and all of the 1000–875 BCE individuals that track the ramp-up of EEF ancestry from MBA to IA levels, are from Kent in far southeastern Britain (Extended Data Fig. 6). The migrant stream began admixing more broadly through southern Britain by the second half of the LBA, as individual I12624 from Blackberry Field, Potterne in Wiltshire, dated to 950–750 BCE, had an EEF proportion of 38.1±2.0% consistent with the level that became ubiquitous in southern Britain by the beginning of the IA (Extended Data Fig. 3). However, as this is the only non-Kent datapoint from the second half of the LBA, more sampling is needed to understand the geographic and temporal course of the spread of this ancestry.

Table 2:

Fitting proxies for the new ancestry source in Iron Age southern Britain

| Proxies for source of the new ancestry | N | Mean date | p-value | Ancestry |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Margetts Pit and Cliffs End Farm M-LBA | 4 | 1036 BCE | 0.07 | 49.4 ± 3.0% |

| Spain IA Tartessian | 2 | 629 BCE | 0.16 | 23.7 ± 1.2% |

| France GrandEst IA1 (shotgun data) | 5 | 620 BCE | 1.00 | 48.9 ± 3.7% |

| France Occitanie IA2 (high EEF subgroup, shotgun data) | 1 | 450 BCE | 0.85 | 25.8 ± 1.7% |

| France Occitanie IA2 (high WHG subgroup, shotgun data) | 1 | 450 BCE | 0.39 | 33.5 ± 4.1% |

| France Occitanie IA2 (shotgun data) | 2 | 400 BCE | 0.25 | 53.3 ± 5.4% |

| France Occitanie IA2 (low Steppe subgroup, shotgun data) | 2 | 363 BCE | 0.33 | 36.5 ± 2.6% |

| France GrandEst IA2 | 12 | 250 BCE | 0.09 | 68.5 ± 3.3% |

Note: We fit the pooled IA individuals from England and Wales as a mixture of the pooled C/EBA individuals from England and Wales and a proxy for the new ancestry source. The p-value is from qpAdm’s test of fit of each population as a two-way admixture with no correction for multiple hypothesis testing. These results represent eight of the 65 lines in Supplementary Information section 6, Table S6.1

Regional variation in Iron Age Britain

Estimates of Margetts Pit and Cliffs End Farm-like ancestry in southern Britain range from 35±5% in northern England to 56±5% in south-central England (Table 1, Extended Data Table 2). The IA was a period when material culture was increasingly regional in character16, and our results show that this was accompanied by subtle genetic structure, although without southern Britain there is no clear correlation of these admixture proportions to latitude (Table 1). We highlight the case of East Yorkshire, where most individuals are from ‘Arras Culture’ contexts comprising square-ditched barrows and occasional chariot burials. Similarities to funerary traditions of IA societies in the Paris Basin and Ardennes/Champagne regions have led to suggestions that East Yorkshire was influenced by direct migration from continental Europe in the IA20. Our estimate of the Margetts Pit/Cliffs End Farm ancestry source for East Yorkshire burials is 44±4% (Table 1), typical for middle latitudes of Britain at this time (East Anglia is similar). However, the East Yorkshire burials are distinctive in another way: regional differentiation in IA Britain, as measured by FST, is higher between East Yorkshire and other groups than it is between any other pair of IA populations in England and Wales in our dataset (Extended Data Table 2). Comparative data from the continent could make it possible to determine if this is due to isolation of IA East Yorkshire from the rest of southern Britain, or later streams of migration specifically affecting East Yorkshire.

Archaeological and linguistic context

The period from 1500–1150 BCE has long been recognized as a time when cultural connections between Britain and regions of continental Europe intensified, and when societies on both sides of the Channel shared cultural features including domestic pottery, metalwork and ritual depositional practices2–6. From around 750 BCE there is more limited archaeological evidence of contact between Britain and the continent, and our genetic findings concur in showing that, by the beginning of the IA, there is little evidence of demographically significant migration into Britain2. Our findings do not establish whether the population movements we infer were a cause or consequence of M-LBA exchange networks, but they do suggest that interactions between local populations of Britain and new migrants bringing ideas from continental Europe could have been a vector for some of the cultural change we see in M-LBA England and Wales. Western and Central France are much more poorly represented by available genome-wide ancient DNA data than neighboring regions of Europe, and thus we cannot at present test if the gene flow between the two regions in this period was largely unidirectional.

Population movements are often a significant driver of cultural change, including in the languages people speak. While periods of intense migration such as the one we infer here do not always result in language shifts18, genetic evidence of significant migration is important because it documents demographic processes that are plausible conduits for language spread21. Several researchers have interpreted linguistic data as providing evidence for early Celtic languages spreading into Britain from France at the end of the Bronze Age or in the early IA22,23. Our identification of substantial migration into Britain from sources that best fit populations in France provides an independent line of evidence in support of this, and points to the M-LBA as a prime candidate for the period of this language spread. While the lack of evidence for M-LBA EEF ancestry change in Scotland could be interpreted as weakening the case that Celtic language spread into Britain at this time, a later arrival of Celtic languages in Scotland is consistent with evidence that non-Celtic and Celtic languages coexisted there into the first millennium CE24. Our finding of a decrease of EEF ancestry in Iberia, where the proportion was relatively high in the EBA, and a roughly simultaneous increase in Britain where the proportion was relatively low in the EBA (Fig. 4a), could, in theory, reflect a Celtic-speaking group of people with intermediate EEF ancestry spreading into both regions, although such a simple model cannot explain all the north-south ancestry convergence in Europe (Supplementary Information section 7). Nevertheless, the fact that the Margetts Pit and Cliffs End Farm outliers are genetically very similar to the Knoviz culture sample from Central Europe (Supplementary Information section 6) is striking in light of the fact that some scholars have hypothesized Central European Urnfield groups like Knoviz to have links to Celtic language spread25. Our failure to find evidence of large-scale migration into Britain from continental Europe in the IA suggests that, if Celtic language spread was driven by large-scale movement of people, it is unlikely to have occurred at this time. The adoption in IA Britain of cultural practices originating in continental Europe—particularly those linked to the La Tène tradition26—was also evidently independent of large-scale population movements, although there certainly were smaller movements, attested by individual IA outliers with high EEF ancestry such as those at Thame or Winnall Down (Fig. 3).

An important direction for future work is to generate new ancient DNA data from continental contexts especially in central and western France—and also Ireland—to test the alternative scenarios of population history consistent with the observations in this study, and to develop theories integrating the genetic findings within archaeological frameworks.

Methods

Ancient DNA laboratory work

All human skeletons analysed in this study were sampled with written permission of the stewards of the skeletons and every individual is represented by at least one co-author. Researchers who wish to obtain further information about specific individuals should write to the corresponding authors and/or the authors who provided the archaeological contextualization for those individuals given in Supplementary Information section 1). In dedicated clean rooms at Harvard Medical School, the University of Vienna, the Natural History Museum in London, and the University of Huddersfield, as well as during sampling trips, we obtained powder from ancient bones and teeth using methods including sandblasting, drilling and milling31,32. We extracted DNA using a variety of methods33–35, and prepared double- or single-stranded libraries treated with the enzyme Uracil DNA Glycosylase to reduce characteristic errors associated with ancient DNA degradation36–39. We enriched these sequences manually or in multiplex using automated liquid handlers for sequences overlapping the mitochondrial genome40,41 as well as about 1.24 million single nucleotide polymorphisms42. We pooled enriched libraries which we had marked with unique 7-base pair internal barcodes and/or 7- to 8-base pair indices and sequenced on Illumina NextSeq500 or HiSeqX10 instruments using paired-end reads of either 76 base pairs or 101 base pairs in length (Supplementary Table 2).

Bioinformatic analysis

After trimming barcodes and adapters30, we merged read pairs with at least 15 base pairs of overlap allowing no more than one mismatch if base quality was at least 20, or up to three mismatches if base qualities were <20; we chose the nucleotide of the higher quality in case of a conflict while setting the local base quality to the minimum of the two (for these steps we used a custom toolkit at https://github.com/DReichLab/ADNA-Tools). We aligned merged sequences to the mitochondrial genome RSRS43 or the human genome hg19 (GRCh37, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/assembly/GCF_000001405.13/) using the samse command44 of BWA version 0.7.15 with parameters -n 0.01, -o 2, and -l 16500. After identifying PCR duplicates by tagging all aligned sequences with the same start and stop positions and orientation and in some cases in-line barcodes using Picard MarkDuplicates (http://broadinstitute.Github.io/picard/), and restricting to sequences that spanned at least 30 base pairs, we selected a single copy of each such sequence that had the highest base quality score. For subsequent analysis, we trimmed the last 2 bases of each sequence for UDG-treated libraries and the last 5 for non-UDG-treated libraries to reduce the effects of characteristic errors associated with ancient DNA degradation. We built mitochondrial consensus sequences, determined haplogroups using HaploGrep2 version 2.1.1545 and Phylotree version 17, and estimated the match rate to the consensus sequence using contamMix version 1.0–1246 when coverage was at least two-fold. To represent the nuclear data, we randomly sampled a single sequence covering each of the 1.24 million SNP targets, and estimated coverage based on the subset of these targeted SNPs on the autosomes. We used ANGSD version 0.923 to estimate contamination based on polymorphism on the X chromosome in males with at least 200 SNPs covered twice (males should be non-polymorphic if their data are uncontaminated)47. We automatically determined Y chromosome haplogroups using both targeted SNPs and off-target sequences aligning to the Y chromosome based on comparisons to the Y chromosome phylogenetic tree from Yfull version 8.09 (https://www.yfull.com/), providing two alternative notations for Y chromosome haplogroups: the first using a label based on the terminal mutation, and the second describing all associated branches of the Y chromosome tree based on the notation of the International Society of Genetic Genealogy (ISOGG) database version 15.73. (http://www.isogg.org). We manually checked the Y chromosome haplogroups for the males in the Britain time transect.

Determination of ancient DNA authenticity

We determined ancient DNA authenticity based on five criteria. First, we required that the lower bound of the 95% confidence interval for contamination from ANGSD (if we were able to compute it) was <1%. Second, we required that the upper bound of the 95% confidence interval for match rate to mitochondrial consensus sequence (if we were able to compute it) was >95%. Third, we required that the average rate of cytosine-to-thymine errors at the terminal nucleotide for all sequences passing filters was >3% for double-stranded partially UDG-treated libraries39 and >10% for single-stranded USER-treated libraries and double-stranded non-UDG-treated libraries (the latter libraries are all from previously published data that we reanalysed here)48. Fourth, we required the ratio of sequences mapping to the Y chromosome to the sum of sequences mapping to the X and Y chromosome for the 1240K data to be less than 3% (consistent with a female) or >35% (consistent with a male). Fifth, to report an individual we required the number of SNPs covered at least once to be at least 5,000 (for most actual population genetic analyses, we required at least 30,000). For some individuals with evidence of contamination, we analysed only sequences with terminal damage to enrich for genuine ancient DNA, allowing us to study more individuals49. We do not include in our main analyses data from 71 individuals that failed our authenticity criteria (marked as “QUESTIONABLE” in Supplementary Table 1); however, we publish the data as part of this study as a resource.

Approach to chronological uncertainty

We restricted individuals for which we newly report data to those whose date estimate (mean of the posterior distribution from radiocarbon carbon dating, or midpoint of the archaeological context date) is older than 43 CE based on information we had available as of July 1 2021. For the great majority of individuals, assignments to chronological periods did not change subsequently. However, there were 23 exceptions, and we study these as part of their original analysis groupings (Supplementary Information section 8).

Population genetic analyses

We detected Runs of Homozygosity (ROH) using hapROH version 0.317. We computed f4-statistics and FST and carried out qpWave and qpAdm analyses in ADMIXTOOLS version 7.0.2, computing standard errors with a Block Jackknife50. For modeling ancestry with pre-Bronze Age sources in qpAdm, we employ the outgroup populations (OldAfrica, WHGA, Balkan_N, OldSteppe) using the assignment of individuals to groups as in Supplementary Table 3. For modeling ancestry with M-LBA sources, we use the outgroups (OldAfrica, OldSteppe, Turkey_N, Netherlands_C.EBA, Poland_Globular_Amphora, Spain.Portugal_4425.to.3800BP, CzechRepublic.Slovakia.Germany_3800.to.2700BP, Sardinia_8100.to.4100BP, CzechRepublic.Slovakia.Germany_4465.to.3800.BP, Sardinia_4100.to.2700BP, and Spain.Portugal_6500.to.4425BP), using the assignment of individuals to groups specified in either Supplementary Table 3 or in Supplementary Table 5.

Relative detection

We inferred relatives up to the third degree as previously described51.

Allele frequency estimates of variants with functional importance

We clustered individuals into the temporal groupings specified in Supplementary Table 5. To estimate the allele frequency of a given SNP in a particular group for Supplementary Table 8, we used sequence counts at each SNP position in each individual and a maximum likelihood approach52. We obtained confidence intervals using the Agresti-Coull method implemented in the binom.confint function of the R-package binom. For the imputation-based methodology for studying the trajectory of the lactase persistence allele (Fig. 4B), we used GLIMPSE37 to impute diploid genotype posterior probabilities (GP) based on 1000 Genomes Projects haplotypes38, restricting to samples with max(GP)>0.9 for this SNP. To represent allele frequencies in modern Britain we use a pool of 190 CEU and GBR individuals from the 1000 Genomes Project38, and to represent modern Central Europe we used 288 individuals from the modern Czech Republic39. We visualise the frequency trajectory of the lactase persistence allele at SNP rs4988235 in Figure 4B using the GaussianProcessRegressor function from the Scikit-learn library in Python with parameter alpha=0.1 and 1*RationalQuadratic kernel with parameter length_scale_bounds=(1, 1000).

Radiocarbon dating

We carried out Accelerator Mass Spectrometry (AMS) dating at a variety of laboratories (n=81 at SUERC, n=40 at PSUAMS, n=1 at BRAMS, and n=1 at Poz); Supplementary Table 4 gives specifies the methods we and also gives the detailed measurements. We refer readers to the individual labs for the experimental protocols. We calibrated all dates using OxCal 4.4.253 and IntCal2054.

Extended Data

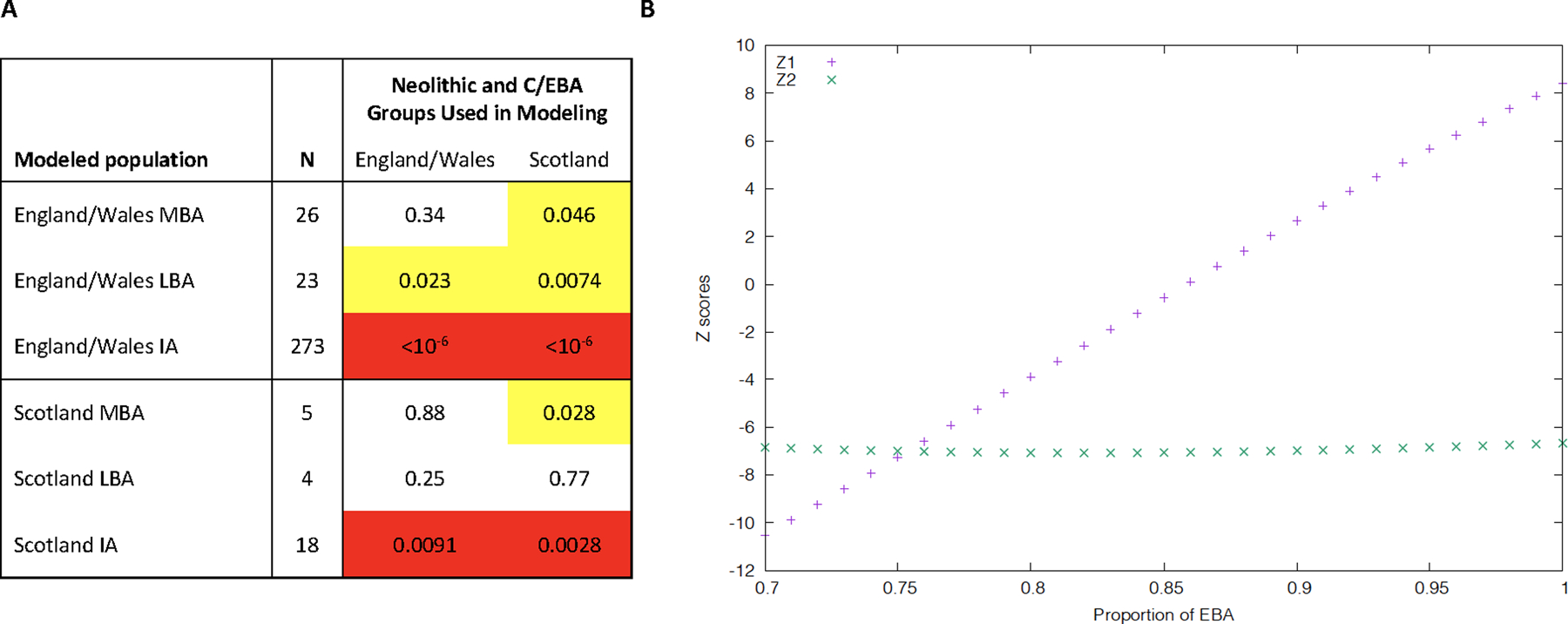

Extended Data Fig. 1 |. Post-MBA Britain was not a mix of earlier British populations.

(A) qpAdm p-values for modeling British groups as a mix of Neolithic and Chalcolithic/EBA populations from England and Wales or Scotland (outgroups OldAfrica, OldSteppe, Turkey_N, CzechRepublic.Slovakia.Germany_3800.to.2700BP, Netherlands_C.EBA, Poland_Globular_Amphora, Spain.Portugal_4425.to.3800BP, CzechRepublic.Slovakia.Germany_4465.to.3800.BP, Sardinia_4100.to.2700BP, Sardinia_8100.to.4100BP, Spain.Portugal_6500.to.4425BP). We highlight p<0.05 (yellow) or p<0.005 (red). Both sources and target populations in this analysis remove outlier individuals (“Filter 2” in Supplementary Table 5); we obtain qualitatively similar results when outlier individuals are not removed (not shown). (B) To obtain insight into the source of the new ancestry in Britain in the IA, we computed f4(England.and.Wales_IA, α(England.and.Wales_N) + (1-α)(England.Wales_C.EBA); R1, R2) for different (R1, R2) population pairs. If England.and.Wales_IA is a simple mixture of England.and.Wales_N and England.and.Wales_C.EBA without additional ancestry, then for some mixture proportion the statistic will be consistent with zero for all (R1, R2 pairs). When (R1, R2) = (OldAfrica, OldSteppe) feasible Z-scores (Z1 in the plot) are observed when α∼0.85, showing that ~85% ancestry from England.and.Wales_C.EBA ancestry is needed to contribute the observed proportion of Steppe ancestry in England.and.Wales_IA. However, when (R1, R2) is (Balkan_N, Sardinian_8100.to.4100BP), we get infeasible Z-scores (Z2) of <−6 across the range where Z1 is remotely feasible. Thus, Iron Age people from England and Wales must have ancestry from an additional population deeply related to Sardinian Early Neolithic groups.

Extended Data Fig. 2 |. By-individual analysis of the British time transect.

Version of Figure 3 with the time transect extended into the Neolithic, and adding in individuals from Scotland. We plot mean estimates of EEF ancestry and one standard error bars from a Block Jackknife for all individuals in the time transect that pass basic quality control, that fit to a three-way admixture model (EEF + WHG + Yamnaya) at p>0.01 using qpAdm, and for the Neolithic period that fit a two-way admixture model (EEF + WHG) at p>0.01. Individuals that fit the main cluster of their time are shown in blue (southern Britain) and green (Scotland), while red and orange respectively show outliers at the ancestry tails (identified either as p<0.005 based on a qpWave test from the main cluster of individuals from their period and |Z|>3 for a difference in their EEF ancestry proportion from the period, or alternatively p<0.1 and |Z|>3.5). The averages for the main clusters in both southern Britain and Scotland in each archaeological period (Neolithic, C/EBA, MBA, LBA and IA) are shown in dashed lines.

Extended Data Fig. 3 |. Changes in the size of the mate pool over time.

Close kin unions were rare at all periods as reflected in the paucity of individuals harbouring >50 centimorgans (cM) of their genome in runs of homozygosity (ROH) of >12 cM (red dots in top panel). The number of ROH of size 4–8 cM per individual (bottom panel) reflects the rate at which distant relatives have children, providing information about the sizes of mate pools (Ne) averaged over the hundreds of years prior to when individuals lived; thus, the broad trend of an approximately four-fold drop in Ne from the Neolithic to the IA is robust, but we may miss fluctuations on a time scale of centuries. The thick black lines represent the mean Ne obtained by fitting a mathematical model of Gaussian process with a 600-year smoothing kernel (gray area 95% confidence interval). The horizontal grey lines show period averages from maximum likelihood which can differ from the mean obtained through the mathematical modeling if the counts do not confirm well to a Gaussian process. We interrupt the fitted line for periods with too little data for accurate inference (<10 individuals in a 400-year interval centered on the point).

Extended Data Fig. 4 |. Frequency change over time at two phenotypically important alleles.

Present-day frequencies are shown by the red dashed lines; sample sizes for each epoch are labeled at the bottom of each plot; and we show means along with 95% confidence intervals (Supplementary Table 8). (A-D/Top) Lactase persistence allele at rs4988235. (E-H/Bottom) Light skin pigmentation allele at rs16891982. In Britain the rise in frequency of the lactase persistence allele occurred earlier than in Central Europe. This analysis is based on direct observation of alleles; imputation results are qualitatively consistent (Figure 4B).

Extended Data Fig. 5 |. Y chromosome haplogroup frequency changes over time.

Estimated frequency of the characteristically British Y chromosome haplogroup R1b-P312 L21/M529 in all individuals for which we are able to make a determination and which are not first-degree relatives of a higher coverage individual in the dataset. Sample sizes for each epoch are labeled at the bottom, and we show means and one standard error bars from a binominal distribution. The frequency increases significantly from ~0% in the whole island Neolithic, to 89±4% in the whole island C/EBA. It declines non-significantly to 79±9% in the MBA and LBA (from this time onward restricting to England and Wales because of the autosomal evidence of a change in EEF ancestry in the south but not the north). It further declines to 68±4% in the IA, a significant reduction relative to the C/EBA (P=0.014 by a two-sided chi-square contingency test). There is additional reduction from this time to the present, when the proportion is 43±3% in Wales and the west of England (P=5×10−6 for a reduction relative to the IA), and 14±2% in the center and east of England (P=3×10−32 for a reduction relative to the IA).

Extended Data Fig. 6 |. Version of Fig. 3A contrasting Kent to the rest of southern Britain.

We show the period 2450–1 BCE. Each point corresponds to a single individual and we show means and one standard error bars from a Block Jackknife. All the high EEF outliers at the M-LBA are from Kent—the part of the island closest to France—and in addition all the individuals from 1000–875 BCE from the group of samples showing the ramp-up from MBA to IA levels of EEF ancestry are from Kent (5 from Cliffs End Farm and 3 from East Kent Access Road). This suggests the possibility that this small region was the gateway for migration to Britain at the M-LBA. Further sampling from the rest of Britain at the M-LBA is critical in order to understand the dynamics of how this ancestry spread more broadly. However, the fact that only sample from the second half of the LBA that is not from Kent—I12624 from Blackberry Field in Potterne in Wiltshire at 950–750 BCE—already has a proportion of EEF ancestry typical of the IA in southern Britain—suggests that this ancestry began spreading more broadly by the second half of the LBA.

Extended Data Table 1 |. Ancestry change over time in Britain.

We pool all individuals from each period and region removing those failing qpAdm modeling at p<0.01 according to Supplementary Table 5. In the left columns are qpAdm estimates of ancestry based on pre-Bronze Age source populations for each group. Below diagonal are Z-scores from f4(Row population, Column population; Turkey_N, OldSteppe) (highlighted in red if |Z|>3). Above diagonal are inbreeding-corrected FST values (highlighted in yellow if FST>0.005).

| qpAdm results (3-way model) | Tests for difference in ancxestry between row & column (below diagonal f4-statistic Z-score, above-diagonal FST) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | P-value | WHG | EEF | Steppe | WHG error | EEF error | Steppe | England.and.Wales_N | England.and.Wales_C.EBA | England.and.Wales_MBA | England.and.Wales_LBA | England.and.Wales_IA | England.and.Wales_PostIA | England.and.Wales_Modern | Scotland_N | Scotland_C.EBA | Scotland_MBA | Scotland_LBA | Scotland_IA | Scotland_PostIA | Scotland_Modern | Ireland_N | Ireland_C.EBA | Ireland_PostIA | Ireland_Modern | Channel.Islands_8100.to.5700BP | Channel.Islands_5700.to.4450BP | Channel.Islands_IA | |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| England.and.Wales_N | 37 | 0.7597 | 20.8% | 76.7% | 2.6% | 0.5% | 0.5% | 0.6% | 0.02 | 0.0176 | 0.0171 | 0.0161 | 0.0219 | 0.0226 | 0.0013 | 0.0192 | 0.0188 | 0.0188 | 0.0197 | 0.0206 | 0.0239 | 0.0046 | 0.0275 | 0.0233 | 0.0225 | 0.0177 | 0.0073 | 0.0153 | |

| England.and.Wales_C.EBA | 69 | 0.3840 | 12.6% | 31.0% | 56.4% | 0.4% | 0.5% | 0.6% | −65.7 | 0.0007 | 0.0012 | 0.0017 | 0.0084 | 0.0107 | 0.0204 | 0.0013 | 0.0002 | 0.0013 | 0.0019 | 0.006 | 0.0109 | 0.0259 | 0.0112 | 0.0091 | 0.0085 | 0.0357 | 0.0173 | 0.0055 | |

| England.and.Wales_MBA | 26 | 0.0918 | 13.5% | 34.7% | 51.8% | 0.5% | 0.6% | 0.7% | −58.2 | −7.3 | 0.0004 | 0.0008 | 0.0066 | 0.0088 | 0.0181 | 0.0011 | 0.0009 | 0.0013 | 0.0016 | 0.004 | 0.009 | 0.0227 | 0.0099 | 0.0064 | 0.0071 | 0.0333 | 0.0151 | 0.0043 | |

| England.and.Wales_LBA | 23 | 0.4609 | 13.6% | 36.1% | 50.4% | 0.5% | 0.6% | 0.7% | −52.3 | −9.9 | 2.9 | 0.0006 | 0.0056 | 0.007 | 0.0179 | 0.0028 | 0.0012 | 0.0017 | 0.0022 | 0.0037 | 0.0077 | 0.0209 | 0.0089 | 0.0065 | 0.0052 | 0.0319 | 0.0141 | 0.0037 | |

| England.and.Wales_IA | 273 | 0.3637 | 13.6% | 37.9% | 48.5% | 0.3% | 0.4% | 0.5% | −63.9 | −19.4 | 7 | 2.3 | 0.0053 | 0.0073 | 0.0175 | 0.0027 | 0.0011 | 0.0016 | 0.0018 | 0.0035 | 0.0076 | 0.0204 | 0.0099 | 0.0064 | 0.0049 | 0.0306 | 0.0136 | 0.0032 | |

| England.and.Wales_PostIA | 38 | 0.0002 | 15.0% | 36.6% | 48.3% | 0.4% | 0.5% | 0.6% | 61 | −11 | −2.5 | 1 | 5.8 | 0.003 | 0.0239 | 0.0085 | 0.0051 | 0.0074 | 0.0076 | 0.0014 | 0.0037 | 0.0188 | 0.0069 | 4E-05 | 0.0024 | 0.0333 | 0.017 | 0.0049 | |

| England.and.Wales_Modern | 62 | 0.6315 | 14.1% | 40.0% | 45.9% | 0.4% | 0.4% | 0.6% | −61.3 | −19.5 | −8.8 | −4 | −3.5 | 8.5 | 0.0243 | 0.0107 | 0.0071 | 0.0094 | 0.0097 | 0.0034 | 0.0016 | 0.0184 | 0.0083 | 0.0029 | 0.0021 | 0.034 | 0.0175 | 0.0072 | |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Scotland_N | 44 | 0.6642 | 23.1% | 74.3% | 2.5% | 0.4% | 0.5% | 0.6% | 2.7 | −65.1 | −55.5 | −51.3 | −64.4 | −61.3 | −61.6 | 0.0184 | 0.0186 | 0.0182 | 0.0197 | 0.0227 | 0.026 | 0.0079 | 0.0296 | 0.0243 | 0.0248 | 0.0196 | 0.0084 | 0.0164 | |

| Scotland_C.EBA | 10 | 0.1517 | 13.5% | 32.2% | 54.3% | 0.6% | 0.7% | 1.0% | 52 | −3 | 1.6 | 4.3 | 6.4 | 3.5 | 7.8 | −50.6 | 0.0011 | 0.002 | 0.0022 | 0.0064 | 0.0107 | 0.0243 | 0.0099 | 0.0079 | 0.0098 | 0.0338 | 0.0194 | 0.0067 | |

| Scotland_MBA | 5 | 0.5635 | 14.0% | 32.3% | 53.7% | 0.8% | 0.9% | 1.1% | 45.2 | −1.7 | 2 | 4.1 | 6.2 | 3.9 | 7.4 | −44.8 | 0.5 | 0.0009 | 0.0013 | 0.0032 | 0.0074 | 0.0216 | 0.0078 | 0.007 | 0.0061 | 0.032 | 0.0132 | 0.0036 | |

| Scotland_LBA | 4 | 0.8346 | 12.4% | 34.0% | 53.7% | 0.8% | 1.0% | 1.2% | 39.8 | −4 | −0.1 | 1.3 | 3.2 | 1 | 4.2 | −40.4 | −1.1 | 1.7 | 0.0002 | 0.0047 | 0.0098 | 0.0239 | 0.0101 | 0.0084 | 0.0074 | 0.0357 | 0.0152 | 0.007 | |

| Scotland_IA | 18 | 0.1850 | 12.7% | 33.4% | 54.0% | 0.6% | 0.6% | 0.8% | 56.1 | −3.8 | 1.7 | 4.1 | 8.4 | 4.3 | 10.2 | −56 | 0.2 | 1.1 | −1.4 | 0.0047 | 0.0095 | 0.0251 | 0.0108 | 0.0083 | 0.0069 | 0.035 | 0.0178 | 0.0044 | |

| Scotland_PostIA | 10 | 0.4713 | 12.9% | 36.4% | 50.7% | 0.6% | 0.7% | 0.9% | 50.4 | −7.4 | −1.5 | 1.2 | 3.7 | 0.3 | 5.1 | 48.3 | −2.5 | −3 | −0.6 | −2.9 | 0.0034 | 0.0189 | 0.0068 | 0.0021 | 0.0015 | 0.0331 | 0.0162 | 0.0037 | |

| Scotia nd_Modern | 78 | 0.7341 | 14.3% | 37.5% | 48.2% | 0.4% | 0.4% | 0.6% | 62.1 | −12.9 | −3.5 | 0.2 | 5.1 | −1.2 | 7.9 | −62.4 | −4.2 | −4.5 | −1.5 | −5.5 | 1 | 0.0201 | 0.0089 | 0.0032 | 0.001 | 0.0352 | 0.0179 | 0.0078 | |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ireland_N | 51 | 0.6505 | 21.6% | 77.9% | 0.5% | 0.4% | 0.5% | 0.5% | −0.5 | −69.3 | −59 | −54.9 | −69.3 | −65.8 | −65.9 | 3.3 | 51.4 | 45.4 | 40.9 | 57.2 | 52 | 67.2 | 0.0238 | 0.0189 | 0.019 | 0.0183 | 0.0081 | 0.0158 | |

| Ireland_C.EBA | 3 | 0.4166 | 13.6% | 30.5% | 55.9% | 0.9% | 1.2% | 1.5% | 37.9 | 1.5 | 4.7 | 6.4 | 8 | 5.9 | 9 | −38 | −3.3 | −2.8 | −4.3 | −3.9 | −5.4 | −6.6 | −38.8 | 0.0056 | 0.0068 | 0.0408 | 0.0256 | 0.0094 | |

| Ireland_PostIA | 3 | 0.0109 | 14.0% | 34.9% | 51.1% | 0.9% | 1.1% | 1.3% | 37.6 | −3.8 | −0.3 | 1.5 | 3.1 | 1.1 | 4.1 | −37.5 | 1.4 | 1.8 | 0 | 1.3 | −0.8 | −1.5 | 38.6 | −3.9 | 0.0027 | 0.0336 | 0.0166 | 0.0049 | |

| Ireland_Modern | 30 | 0.6461 | 12.9% | 36.8% | 50.3% | 0.4% | 0.5% | 0.7% | 57.6 | −8.7 | 0 | 3.2 | 7.3 | 1.3 | 10.6 | −56.8 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 0.5 | 3.6 | −1.2 | −3.7 | −61.1 | −5.5 | −0.5 | 0.0346 | 0.0161 | 0.005 | |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Channel.lslands_8100.to.5700BP | 3 | 0.7577 | 16.1% | 82.3% | 1.6% | 1.3% | 1.4% | 1.6% | 3.5 | 36.4 | 33.7 | 31.8 | 32.7 | 33.2 | 31.8 | 4.4 | 33.8 | 30.8 | 28.6 | 33.9 | 32 | 33 | 3.3 | 29.8 | 29.3 | 30.3 | 0.0126 | 0.0266 | |

| Channel.lslands_5700.to.4450BP | 3 | 0.4611 | 31.0% | 67.1% | 1.9% | 1.2% | 1.3% | 1.4% | −7.9 | 28.1 | 24.7 | 23.7 | 23.8 | 24.4 | 22.7 | −7 | 24.1 | 23.3 | 20.8 | 24.9 | 23.4 | 24.4 | −8.3 | 23 | 20.5 | 21.1 | −8.4 | 0.0099 | |

| Channel.Islands_IA | 4 | 0.8603 | 15.4% | 43.9% | 40.7% | 0.9% | 1.2% | 1.4% | −28.3 | 11.3 | 7.5 | 6 | 5.3 | 6.7 | 4.2 | −27.3 | 7.3 | 7.8 | 6.5 | 8.5 | 6.7 | 6.4 | −29.3 | 9.3 | 5.9 | 5.9 | 22.4 | 13.8 | |

Extended Data Table 2 |. Fine genetic structure in Iron Age Britain.

This is an expanded version of Table 1 including not just ancestry estimates for each group but also pairwise population comparisons. We pool all individuals from each period and region removing those failing qpAdm modeling at p<0.01 according to Supplementary Table 5. In the left columns are qpAdm estimates of ancestry for each group. Below diagonal are Z-scores from f4(Row population, Column population; Turkey_N, OldSteppe) (highlighted in red if |Z|>3). Above diagonal are inbreeding-corrected FST values (highlighted in yellow if FST>0.0025).

| qpAdm results (3-way model) | Tests for difference in ancestry between row & column (below diagonal f4-statistic Z-score, above-diagonal FST) | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | P-value for qpAdm (3-way model) | WHG (3-way model) | EEF (3-way model) | Steppe (3-way model) | WHG err. (3-way model) | EEF err. (3-way model) | Steppe err. (3-way model) | Scotland West | Scotland Southeast | Scotland Orkney | England Midlands | England North | England Cornwall | England East Anglia | England East Yorkshire | England Southeast | England Southwest | England Southcentral | Wales North | Wales South | |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Scotland West | 4 | 0.12 | 13.0% | 32.3% | 54.7% | 0.8% | 1.0% | 1.2% | 0.0007 | 0.0006 | 0.0032 | 0.0035 | 0.0052 | 0.0035 | 0.0046 | 0.0034 | 0.004 | 0.0034 | n/a | 0.0038 | |

| Scotland Southeast | 12 | 0.67 | 12.1% | 33.9% | 54.0% | 0.6% | 0.7% | 0.9% | 0.3 | 0.001 | 0.0012 | 0.0008 | 0.0028 | 0.0017 | 0.003 | 0.0014 | 0.0015 | 0.0019 | n/a | 0.0018 | |

| Scotland Orkney | 2 | 0.22 | 14.2% | 34.1% | 51.6% | 1.1% | 1.2% | 1.6% | 0.7 | 1.1 | 0.0018 | 0.0013 | 0.0037 | 0.0007 | 0.0029 | 0.0014 | 0.0021 | 0.0021 | n/a | 0.0074 | |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| England Midlands | 18 | 0.66 | 12.6% | 36.0% | 51.4% | 0.5% | 0.6% | 0.8% | 2.8 | 3.4 | 0.9 | 0.0001 | 0.0022 | 0.001 | 0.0028 | 0.0008 | 0.0009 | 0.0013 | n/a | 0.0016 | |

| England North | 10 | 0.35 | 13.4% | 36.3% | 50.3% | 0.6% | 0.8% | 1.0% | 2.4 | 2.6 | 0.9 | 0.1 | 0.0027 | 0.0005 | 0.0016 | 0.0002 | 0.0007 | 0.0009 | n/a | 0.0019 | |

| England Cornwall | 16 | 0.40 | 13.5% | 36.4% | 50.1% | 0.5% | 0.7% | 0.8% | 3.0 | 3.8 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.0025 | 0.0041 | 0.002 | 0.0021 | 0.0024 | n/a | 0.0024 | |

| England East Anglia | 21 | 0.44 | 13.5% | 37.0% | 49.5% | 0.5% | 0.5% | 0.7% | 3.7 | 4.8 | 1.7 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 0.1 | 0.002 | 0.0007 | 0.0011 | 0.0013 | n/a | 0.0012 | |

| England East Yorkshire | 47 | 0.61 | 13.2% | 37.0% | 49.8% | 0.4% | 0.5% | 0.6% | 4.1 | 5.4 | 2.1 | 1.5 | 1.7 | −0.6 | −0.5 | 0.0022 | 0.0026 | 0.0023 | n/a | 0.0028 | |

| England Southeast | 36 | 0.13 | 13.9% | 38.3% | 47.8% | 0.5% | 0.5% | 0.6% | 5.4 | 7.2 | 2.8 | −3.8 | −3.2 | −2.5 | −3.4 | −3.2 | 0.0008 | 0.0005 | n/a | 0.0008 | |

| England Southwest | 84 | 0.30 | 13.7% | 38.7% | 47.6% | 0.4% | 0.4% | 0.6% | 5.6 | 8.4 | 3.3 | −4.5 | −4.3 | −3.3 | −3.7 | −3.4 | 0.2 | 0.0009 | n/a | 0.0013 | |

| England Southcentral | 38 | 0.32 | 13.9% | 38.8% | 47.2% | 0.4% | 0.5% | 0.6% | 5.6 | 7.5 | 3.3 | −4.6 | −3.6 | −2.7 | −3.0 | −3.3 | 0.0 | −0.2 | n/a | 0.0013 | |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Wales North | 1 | 0.20 | 12.1% | 34.7% | 53.2% | 1.6% | 2.0% | 2.5% | 0.8 | 1.1 | 2.0 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 2.9 | 3.1 | 3.6 | 3.6 | 3.5 | n/a | |

| Wales South | 2 | 0.66 | 14.2% | 38.6% | 47.2% | 1.2% | 1.5% | 1.8% | −2.7 | −3.1 | −1.5 | −1.6 | −1.3 | −1.2 | −1.0 | −0.9 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.3 | −1.9 | |

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank P. Csengeri, T. de Rider, M. Giesen, E. Melis, A. Parkin, and A. Schmitt for their contribution to sample selection and collection of archaeological data. We thank R. Crellin, J. Koch, K. Kristiansen, and G. Kroonen for comments on the manuscript. We thank A. Williamson for manually revising Y chromosome haplogroup determinations and making corrections to nine. We thank M. Lee for assistance with data entry. This work was funded in part by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No. 834087; the COMMIOS Project to I.A.). M.N. was supported by the Croatian Science Fund grant (HRZZ IP-2016-06-1450). P.V., M.Dobe., and Z.V. were supported by the Ministry of Culture of the Czech Republic (DKRVO 2019-2023/7.I.c, 00023272). M.E. was supported by Czech Academy of Sciences award Praemium Academiae. M.Dob. and A.Da. were supported by the grant RVO 67985912 of the Institute of Archaeology of the Czech Academy of Sciences. M.G.B.F. was funded by The Leverhulme Trust via a Doctoral Scholarship scheme awarded to M.Pal. and M.B.R. Support to M.Leg. came from the South, West & Wales Doctoral Training Partnership. M.G.’s osteological analyses were funded by Culture Vannin. A.S-N. was supported by the János Bolyai Research Scholarship of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. T.H., T.S.Z. and K.K.’s work was supported by a grant from the Hungarian Research, Development and Innovation Office (project number: FK128013). We acknowledge support for radiocarbon dating and stable isotope analyses as well as access to skeletal material from Manx National Heritage and A. Fox. Dating analysis was funded by Leverhulme Trust grant RPG-388. M.G.T. and I.B. were supported by a Wellcome Trust Investigator Award (project 100713/Z/12/Z). I.O. was supported by a Ramón y Cajal grant from Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación, Spanish Government (RYC2019-027909-I). The research directed at Harvard was funded by NIH grant GM100233; by John Templeton Foundation grant 61220; by a gift from Jean-François Clin; and by the Allen Discovery Center program, a Paul G. Allen Frontiers Group advised program of the Paul G. Allen Family Foundation. D.R. is also an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this paper.

Competing interests The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Code availability This study uses publicly available software which we fully reference.

Supplementary information The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-04287-4.

Peer review information We thank Daniel Bradley, Daniel Lawson, Patrick Sims-Williams, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Data availability

The raw data are available as aligned sequences (bam files) through the European Nucleotide Archive under accession number PRJEB47891. The newly generated genotype data are available as a Supplementary data file. The previously published data co-analysed with our newly reported data can be obtained as described in the original publications, which are all referenced in Supplementary Table 3; a compiled dataset that includes the merged genotypes used in this paper is available as the Allen Ancient DNA Resource at https://reich.hms.harvard.edu/allen-ancient-dna-resourceaadr-downloadable-genotypes-present-day-and-ancient-dna-data. Any other relevant data are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Galinsky KJ, Loh PR, Mallick S, Patterson NJ & Price AL Population structure of UK Biobank and ancient Eurasians reveals adaptation at genes influencing blood pressure. Am J Hum Genet 99, 1130–1139, doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.09.014 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cunliffe B Britain Begins. (Oxford University Press, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koch JT, Cunliffe BW Celtic from the West 2: Rethinking the Bronze Age and the Arrival of Indo-European in Atlantic Europe. (Oxbow Books, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Needham S & Bowman S Flesh-hooks, technological complexity and the Atlantic Bronze Age feasting complex. European Journal of Archaeology 8, 93–136, doi: 10.1177/1461957105066936 (2005). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marcigny C, Bourgeois J & Talon M in Rythmes et contours de la geographie culturelle sur le littoral de la Manche entre le IIIe et le debut du Ier millenaire (chapter title: Movement, exchange and identity in Europe in the 2nd and 1st millennia BC: beyond frontiers (eds Lehoerff A & Talon M) 63–78 (Oxbow Books, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marcigny C in Les Anglais in Normandie (chapter title: Les relations transmanche durant l’age du Bronze entre 2300 et 800 avant notre ère) 47–54 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cassidy LM et al. Neolithic and Bronze Age migration to Ireland and establishment of the insular Atlantic genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113, 368–373, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1518445113 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olalde I et al. The Beaker phenomenon and the genomic transformation of northwest Europe. Nature 555, 190–196, doi: 10.1038/nature25738 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brace S et al. Ancient genomes indicate population replacement in Early Neolithic Britain. Nat Ecol Evol 3, 765–771, doi: 10.1038/s41559-019-0871-9 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schiffels S et al. Iron Age and Anglo-Saxon genomes from East England reveal British migration history. Nat Commun 7, 10408, doi: 10.1038/ncomms10408 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reich D, Thangaraj K, Patterson N, Price AL & Singh L Reconstructing Indian population history. Nature 461, 489–494, doi: 10.1038/nature08365 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lazaridis I et al. Ancient human genomes suggest three ancestral populations for present-day Europeans. Nature 513, 409–413, doi: 10.1038/nature13673 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Evans JA, Chenery CA & Montgomery J A summary of strontium and oxygen isotope variation in archaeological human tooth enamel excavated from Britain. Journal of Analytical Atomic Spectrometry 27, 754–764, doi: 10.1039/C2JA10362A (2012). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fitzpatrick AP The Amesbury Archer and the Boscombe Bowmen: Early Bell Beaker burials at Boscombe Down, Amesbury, Wiltshire, Great Britain: Excavations at Boscombe Down. Vol. 1 (Wessex Archaeology, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Millard AR in Cliffs End Farm, Isle of Thanet, Kent: A Mortuary and Ritual Site of the Bronze Age, Iron Age and Anglo-Saxon Period With Evidence for Long-Distance Maritime Mobility (eds McKinley JI et al. ) 135–146 (Wessex Archaeology, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Champion TC, Haselgrove C, Armit I, Creighton J & Gwilt A Understanding the British Iron Age: An Agenda for Action. A Report for the Iron Age Research Seminar and the Council of the Prehistoric Society. (Trust for Wessex Archaeology, 2001). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ringbauer H, Novembre J & Steinrucken M Parental relatedness through time revealed by runs of homozygosity in ancient DNA. Nat Commun 12, 5425, doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-25289-w (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olalde I et al. The genomic history of the Iberian Peninsula over the past 8000 years. Science 363, 1230–1234, doi: 10.1126/science.aav4040 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Busby GBJ et al. The peopling of Europe and the cautionary tale of Y chromosome lineage R-M269. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 279, 884–892, doi: 10.1098/rspb.2011.1044 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halkon P The Arras Culture of Eastern Yorkshire: Celebrating the Iron Age. (Oxbow Books, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bellwood PS & Renfrew C Examining the Farming/Language Dispersal Hypothesis. (McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, 2002). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sims-Williams P An Alternative to ‘Celtic from the East’ and ‘Celtic from the West’. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 30, 511–529, doi: 10.1017/S0959774320000098 (2020). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mallory JP The Origins of the Irish. (Thames & Hudson Inc., 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rodway S The Ogham inscriptions of Scotland and Brittonic Pictish. Journal of Celtic Linguistics 21, 173–234, doi: 10.16922/jcl.21.6 (2020). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herm G The Celts: The people who came out of the darkness. (Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1976). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guggisberg M in Oxford Handbook of the European Iron Age (ed Rebay-Sailsbury K, Haselgrove C, Wells P) (Oxford University Press, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Booth TJ A stranger in a strange land: a perspective on archaeological responses to the palaeogenetic revolution from an archaeologist working amongst palaeogeneticists. World Archaeology 51, 586–601, doi: 10.1080/00438243.2019.1627240 (2019). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anthony DW Migration in archeology: The baby and the bathwater. American Anthropologist 92, 895–914 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vander Linden M Population history in third-millennium-BC Europe: assessing the contribution of genetics. World Archaeology, doi: 10.1080/00438243.2016.1209124 (2016). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haak W et al. Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe. Nature 522, 207–211, doi: 10.1038/nature14317 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pinhasi R, Fernandes DM, Sirak K & Cheronet O Isolating the human cochlea to generate bone powder for ancient DNA analysis. Nature Protocols 14, 1194–1205, doi: 10.1038/s41596-019-0137-7 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sirak KA et al. A minimally-invasive method for sampling human petrous bones from the cranial base for ancient DNA analysis. Biotechniques 62, 283–289, doi: 10.2144/000114558 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dabney J et al. Complete mitochondrial genome sequence of a Middle Pleistocene cave bear reconstructed from ultrashort DNA fragments. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110, 15758–15763, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1314445110 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Korlevic P et al. Reducing microbial and human contamination in DNA extractions from ancient bones and teeth. Biotechniques 59, 87–93, doi: 10.2144/000114320 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rohland N, Glocke I, Aximu-Petri A & Meyer M Extraction of highly degraded DNA from ancient bones, teeth and sediments for high-throughput sequencing. Nat Protoc 13, 2447–2461, doi: 10.1038/s41596-018-0050-5 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gansauge MT et al. Single-stranded DNA library preparation from highly degraded DNA using T4 DNA ligase. Nucleic Acids Res 45, e79, doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx033 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gansauge M-T, Aximu-Petri A, Nagel S & Meyer M Manual and automated preparation of single-stranded DNA libraries for the sequencing of DNA from ancient biological remains and other sources of highly degraded DNA. Nature Protocols 15, 2279–2300, doi: 10.1038/s41596-020-0338-0 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Briggs A & Heyn P in Methods in Molecular Biology Vol. 840 143–154 (Springer, 2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rohland N, Harney E, Mallick S, Nordenfelt S & Reich D Partial uracil-DNA-glycosylase treatment for screening of ancient DNA. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 370, 20130624, doi: 10.1098/rstb.2013.0624 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fu Q et al. DNA analysis of an early modern human from Tianyuan Cave, China. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110, 2223–2227, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1221359110 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maricic T, Whitten M & Paabo S Multiplexed DNA sequence capture of mitochondrial genomes using PCR products. PLoS One 5, e14004, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014004 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fu Q et al. An early modern human from Romania with a recent Neanderthal ancestor. Nature 524, 216–219, doi: 10.1038/nature14558 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Behar DM et al. A “Copernican” reassessment of the human mitochondrial DNA tree from its root. Am J Hum Genet 90, 675–684, doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.03.002 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li H & Durbin R Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760, doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weissensteiner H et al. HaploGrep 2: mitochondrial haplogroup classification in the era of high-throughput sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res 44, W58–63, doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw233 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fu Q et al. A revised timescale for human evolution based on ancient mitochondrial genomes. Curr Biol 23, 553–559, doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.02.044 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Korneliussen TS, Albrechtsen A & Nielsen R ANGSD: Analysis of Next Generation Sequencing Data. BMC Bioinformatics 15, 356, doi: 10.1186/s12859-014-0356-4 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sawyer S, Krause J, Guschanski K, Savolainen V & Paabo S Temporal patterns of nucleotide misincorporations and DNA fragmentation in ancient DNA. PLoS One 7, e34131, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034131 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Skoglund P et al. Separating endogenous ancient DNA from modern day contamination in a Siberian Neandertal. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111, 2229–2234, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1318934111 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Patterson N et al. Ancient admixture in human history. Genetics 192, 1065–1093, doi: 10.1534/genetics.112.145037 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kennett DJ et al. Archaeogenomic evidence reveals prehistoric matrilineal dynasty. Nat Commun 8, 14115, doi: 10.1038/ncomms14115 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mathieson I et al. Genome-wide patterns of selection in 230 ancient Eurasians. Nature 528, 499–503, doi: 10.1038/nature16152 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bronk Ramsey C Bayesian Analysis of Radiocarbon Dates. Radiocarbon 51, 337–360, doi: 10.1017/S0033822200033865 (2009). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reimer PJ et al. The IntCal20 northern hemisphere radiocarbon age calibration curve (0–55 cal kBP). Radiocarbon 62, 725–757, doi: 10.1017/RDC.2020.41 (2020). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw data are available as aligned sequences (bam files) through the European Nucleotide Archive under accession number PRJEB47891. The newly generated genotype data are available as a Supplementary data file. The previously published data co-analysed with our newly reported data can be obtained as described in the original publications, which are all referenced in Supplementary Table 3; a compiled dataset that includes the merged genotypes used in this paper is available as the Allen Ancient DNA Resource at https://reich.hms.harvard.edu/allen-ancient-dna-resourceaadr-downloadable-genotypes-present-day-and-ancient-dna-data. Any other relevant data are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.