Abstract

Background

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a prevalent and disabling disorder. Evidence that PTSD is characterised by specific psychobiological dysfunctions has contributed to a growing interest in the use of medication in its treatment.

Objectives

To assess the effects of medication for reducing PTSD symptoms in adults with PTSD.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; Issue 11, November 2020); MEDLINE (1946‐), Embase (1974‐), PsycINFO (1967‐) and PTSDPubs (all available years) either directly or via the Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Controlled Trials Register (CCMDCTR). We also searched international trial registers. The date of the latest search was 13 November 2020.

Selection criteria

All randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of pharmacotherapy for adults with PTSD.

Data collection and analysis

Three review authors (TW, JI, and NP) independently assessed RCTs for inclusion in the review, collated trial data, and assessed trial quality. We contacted investigators to obtain missing data. We stratified summary statistics by medication class, and by medication agent for all medications. We calculated dichotomous and continuous measures using a random‐effects model, and assessed heterogeneity.

Main results

We include 66 RCTs in the review (range: 13 days to 28 weeks; 7442 participants; age range 18 to 85 years) and 54 in the meta‐analysis.

For the primary outcome of treatment response, we found evidence of beneficial effect for selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) compared with placebo (risk ratio (RR) 0.66, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.59 to 0.74; 8 studies, 1078 participants), which improved PTSD symptoms in 58% of SSRI participants compared with 35% of placebo participants, based on moderate‐certainty evidence.

For this outcome we also found evidence of beneficial effect for the noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressant (NaSSA) mirtazapine: (RR 0.45, 95% CI 0.22 to 0.94; 1 study, 26 participants) in 65% of people on mirtazapine compared with 22% of placebo participants, and for the tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) amitriptyline (RR 0.60, 95% CI 0.38 to 0.96; 1 study, 40 participants) in 50% of amitriptyline participants compared with 17% of placebo participants, which improved PTSD symptoms. These outcomes are based on low‐certainty evidence. There was however no evidence of beneficial effect for the number of participants who improved with the antipsychotics (RR 0.51, 95% CI 0.16 to 1.67; 2 studies, 43 participants) compared to placebo, based on very low‐certainty evidence.

For the outcome of treatment withdrawal, we found evidence of a harm for the individual SSRI agents compared with placebo (RR 1.41, 95% CI 1.07 to 1.87; 14 studies, 2399 participants). Withdrawals were also higher for the separate SSRI paroxetine group compared to the placebo group (RR 1.55, 95% CI 1.05 to 2.29; 5 studies, 1101 participants). Nonetheless, the absolute proportion of individuals dropping out from treatment due to adverse events in the SSRI groups was low (9%), based on moderate‐certainty evidence. For the rest of the medications compared to placebo, we did not find evidence of harm for individuals dropping out from treatment due to adverse events.

Authors' conclusions

The findings of this review support the conclusion that SSRIs improve PTSD symptoms; they are first‐line agents for the pharmacotherapy of PTSD, based on moderate‐certainty evidence. The NaSSA mirtazapine and the TCA amitriptyline may also improve PTSD symptoms, but this is based on low‐certainty evidence. In addition, we found no evidence of benefit for the number of participants who improved following treatment with the antipsychotic group compared to placebo, based on very low‐certainty evidence. There remain important gaps in the evidence base, and a continued need for more effective agents in the management of PTSD.

Plain language summary

Medication for posttraumatic stress disorder

Why is this review important?

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) occurs after exposure to significant trauma and results in enormous personal and societal costs. Although it has traditionally been treated with psychotherapy, medication treatments have proven effective in PTSD treatment.

Who will be interested in this review?

‐ People with PTSD. ‐ Families and friends of people who suffer from PTSD. ‐ General practitioners, psychiatrists, psychologists, and pharmacists.

What question does this review aim to answer?

‐ Is pharmacotherapy effective for reducing PTSD symptoms in adults with PTSD?

Which studies were included in the review?

We included studies comparing medication with placebo or a control, or both, for the treatment of PTSD in adults. We included 66 trials in the review, with a total of 7442 participants.

What does the evidence from the review tell us?

There was evidence of a beneficial effect that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) improve PTSD symptoms compared to placebo, based on moderate‐certainty evidence. There was also evidence of a benefit for the noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressant (NaSSA) mirtazapine and the tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) amitriptyline, in improving PTSD symptoms, based on low‐certainty evidence. We also found no evidence of benefit for the number of participants who improved following treatment with the antipsychotic group compared to placebo, based on very low‐certainty evidence. For the remaining medication classes, we did not observe evidence of a benefit for improving PTSD symptoms.

There was evidence of a harm that more people taking individual SSRI agents dropped out due to side effects than did those taking placebo, but absolute withdrawal rates were low for the SSRI groups.

What should happen next?

Most evidence for pharmacotherapy efficacy is related to SSRIs for acute treatment. There is an ongoing need to develop new pharmacotherapeutic treatments of PTSD.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Comparison 1: Alpha‐blockers versus placebo for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

| Comparison 1: Alpha‐blockers versus placebo for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) | ||||||

|

Population: adults (aged 18‐85)

Settings: multi‐centre trials

Intervention: alpha‐blocker

Comparison: placebo Follow‐up: not specified | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| With placebo | With alpha‐blockers | |||||

| Treatment efficacy ‐ treatment response, as measured by the Global Impressions scale change item (CGI‐I or similar): no. of responders (acute phase) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | We found no studies that looked at the number of participants who responded to prazosin compared to placebo. |

| Treatment tolerability, as measured by Dropouts due to adverse events (acute phase) | Study population | RR 0.99 (0.91 to 1.08) | 304 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatea | No evidence of a difference in dropout rates were found in the alpha‐blocker group (13%) and placebo group (12%) | |

| 118 per 1000 | 117 per 1000 (108 to 128) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 118 per 1000 | 117 per 1000 (107 to 127) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval;RR: risk ratio. N/A: Not applicable. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aDowngraded by one level due to serious risk of bias (concerns with randomisation procedures).

Summary of findings 2. Comparison 2: Antipsychotics versus placebo for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

| Comparison 2: Antipsychotics versus placebo for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) | ||||||

|

Population: adults (aged 18‐85)

Settings: single and multi‐centre trials

Intervention: antipsychotics

Comparison: placebo Follow‐up: not specified | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| With placebo | With antipsychotics | |||||

| Treatment efficacy ‐ treatment response, as measured by the Global Impressions scale change item (CGI‐I or similar): no. of responders (acute phase) | Study population | RR 0.51 (0.16 to 1.67) | 43 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b,c | There was no evidence of a benefit of the number of participants in the antipsychotic groups (71%) compared to the placebo groups (37%) who responded and improved on the CGI‐I scale | |

| 368 per 1000 | 188 per 1000 (59 to 615) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 443 per 1000 | 226 per 1000 (71 to 740) | |||||

| Treatment tolerability, as measured by Dropouts due to adverse events (acute phase) | Study population | RR 0.98 (0.92 to 1.05) | 348 (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa,b | Twice as many participants withdrew from the antipsychotic groups (16%) compared to the placebo groups (7%), but no important difference in dropout rates was found | |

| 71 per 1000 | 66 per 1000 (60 to 73) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; CGI‐I: Clinical Global Impressions Improvement scale;RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aDowngraded by one level due to serious risk of bias (concerns with randomisation procedures). bDowngraded by one level due to serious imprecision (wide confidence intervals). cDowngraded by one level due to moderate heterogeneity (I2 of 50%).

Summary of findings 3. Comparison 3: MAOIs versus placebo for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

| Comparison 3: MAOIs versus placebo for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) | ||||||

|

Population: adults (aged 18‐85)

Settings: multi‐centre trial

Intervention: MAOI

Comparison: placebo Follow‐up: not specified | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| With placebo | With MAOIs | |||||

| Treatment efficacy ‐ treatment response, as measured by the Global Impressions scale change item (CGI‐I or similar): no. of responders (acute phase) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | We found no studies that looked at the number of participants who responded to phenelzine versus placebo. |

| Treatment tolerability, as measured by Dropouts due to adverse events (acute phase) | Study population | RR 1.14 (0.90 to 1.43) | 37 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa,b | More participants dropped out from the placebo group (17%) compared to the MAOI group (5%), but we found no difference in dropout rates | |

| 167 per 1000 | 190 per 1000 (150 to 238) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 167 per 1000 | 190 per 1000 (150 to 239) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval;RR: risk ratio. N/A: Not applicable. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aDowngraded by one level due to serious risk of bias (concerns with randomisation procedures). bDowngraded by one level due to serious imprecision (wide confidence intervals).

Summary of findings 4. Comparison 4: NaSSAs versus placebo for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

| Comparison 4: NaSSAs versus placebo for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) | ||||||

|

Population: adults (aged 18‐85)

Settings: single‐centre trial

Intervention: NaSSA

Comparison: placebo Follow‐up: not specified | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| With placebo | With NaSSAs | |||||

| Treatment efficacy ‐ Treatment response, as measured by the Global Impressions scale change item (CGI‐I or similar): no. of responders (acute phase) | Study population | RR 0.45 (0.22 to 0.94) | 26 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa,b | There was evidence of a benefit for the number of participants with PTSD who responded to treatment (65%) compared to placebo (22%). This is also indicated by the Risk Ratio of 0.45 which indicates that there is a statistically significantly greater number of people in the NaSSA group compared to the placebo group who improved on the CGI‐I scale | |

| 222 per 1000 | 100 per 1000 (49 to 209) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 222 per 1000 | 100 per 1000 (49 to 209) | |||||

| Treatment tolerability, as measured by Dropouts due to adverse events (acute phase) | Study population | RR 0.87 (0.68 to 1.11) | 36 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa,b | The proportion of dropouts due to adverse events was high in participants receiving the NaSSA (18%) relative to placebo (5%), but there was no evidence of a harm between the numbers of participants that dropped out due to adverse events |

|

| 53 per 1000 | 176 per 1000 (20 to 1000) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 53 per 1000 | 178 per 1000 (20 to 1000) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; CGI‐I: Clinical Global Impressions Improvement scale; CAPS: Clinically Administered PTSD Scale;RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aDowngraded by one level due to serious risk of bias (concerns with randomisation procedures). bDowngraded by one level due to serious imprecision (wide confidence intervals).

Summary of findings 5. Comparison 5: SNRIs versus placebo for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

| Comparison 5: SNRIs versus placebo for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) | ||||||

|

Population: adults (aged 18‐85)

Settings: multi‐centre trials

Intervention: SNRIs

Comparison: placebo Follow‐up: for one study at week 24 or at the time of discontinuation if before week 24; the remaining study did not specify follow‐up | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| With placebo | With SNRIs | |||||

| Treatment efficacy ‐ treatment response, as measured by the Global Impressions scale change item (CGI‐I or similar): no. of responders (acute phase) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | We found no studies that looked at the number of participants who responded to venlafaxine versus placebo. |

| Treatment tolerability, as measured by Dropouts due to adverse events (acute phase) | Study population | RR 0.98 (0.88 to 1.10) | 687 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b | Dropout rates due to adverse events were low in the SNRI (4%) and placebo groups (3%) | |

| 26 per 1000 | 25 per 1000 (23 to 29) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 27 per 1000 | 26 per 1000 (24 to 30) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval;RR: risk ratio. N/A: Not applicable. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aDowngraded by one level due to serious risk of bias (concerns with randomisation procedures). bDowngraded by two levels due to considerable heterogeneity (I2 of 92%).

Summary of findings 6. Comparison 6: SSRIs versus placebo for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

| Comparison 6: SSRIs versus placebo for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) | ||||||

|

Population: adults (aged 18‐85)

Settings: single and multi‐centre trials

Intervention: SSRIs

Comparison: placebo Follow‐up: for 1 study at week 10 and for another study 14 days after the last dose of study drug; the remaining studies did not specify follow‐up | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| With placebo | With SSRIs | |||||

| Treatment efficacy ‐ treatment response, as measured by the Global Impressions scale change item (CGI‐I or similar): no. of responders (acute phase) | Study population | RR 0.66 (0.59 to 0.74) | 1078 (8 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatea | There was evidence of a benefit for the number of participants with PTSD who responded to treatment for the SSRI group (58%) compared to the placebo group (35%). This is also indicated by the Risk Ratio of 0.66 which indicates that there is a statistically significantly greater number of people in the SSRI group compared to the placebo group who improved on the CGI‐I scale | |

| 348 per 1000 | 229 per 1000 (205 to 257) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 328 per 1000 | 216 per 1000 (194 to 243) | |||||

| Treatment tolerability, as measured by Dropouts due to adverse events (acute phase) | Study population | RR 0.98 (0.96 to 1.00) | 2399 (14 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatea | A similar proportion withdrew due to treatment adverse events (9% versus 7%) | |

| 66 per 1000 | 65 per 1000 (64 to 66) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 50 per 1000 | 49 per 1000 (48 to 50) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; CGI‐I: Clinical Global Impressions Improvement scale;RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aDowngraded by one level due to serious risk of bias (concerns with randomisation procedures).

Summary of findings 7. Comparison 7: TCAs versus placebo for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

| Comparison 7: TCAs versus placebo for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) | ||||||

|

Population: adults (aged 18‐85)

Settings: single and multi‐centre trials

Intervention: TCAs

Comparison: placebo Follow‐up: not specified | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| With placebo | With TCAs | |||||

| Treatment efficacy ‐ treatment response, as measured by the Global Impressions scale change item (CGI‐I or similar): no. of responders (acute phase) | Study population | RR 0.60 (0.38 to 0.96) | 40 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa,b | There was evidence of a benefit for the number of participants with PTSD who responded to treatment in the TCA group (50%) compared to the placebo group (17%). This is also indicated by the Risk Ratio of 0.60, which indicates that there is a statistically significantly greater number of people in the TCA group compared to the placebo group who improved on the CGI‐I scale | |

| 167 per 1000 | 100 per 1000 (63 to 160) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 167 per 1000 | 100 per 1000 (63 to 160) | |||||

| Treatment tolerability, as measured by Dropouts due to adverse events (acute phase) | Study population | RR 0.92 (0.81 to 1.05) | 141 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatea | We found no evidence of a difference in dropout rates between the TCA groups (23%) and placebo groups (18%) | |

| 182 per 1000 | 167 per 1000 (147 to 191) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; CGI‐I: Clinical Global Impressions Improvement scale;RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aDowngraded by one level due to serious risk of bias (concerns with randomisation procedures). bDowngraded by one level due to serious imprecision (wide confidence intervals).

Background

Description of the condition

Although the phenomenon of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) has long been recognised (for example as "shell shock" or "combat neurosis"), this disorder was only officially recognised in the psychiatric nomenclature in 1980 (APA 1980). Diagnostic criteria for PTSD provided by the 3rd edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM‐III) encouraged research on the epidemiology, psychobiology, and treatment of PTSD. The latest version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (i.e. DSM‐5) has made a number of notable revisions. First, PTSD is now classified in a new category, Trauma‐ and Stressor‐Related Disorders, in which the onset of every disorder has been preceded by exposure to a traumatic or otherwise adverse environmental event (Friedman 2016). Second, a fourth cluster of symptoms has been included (i.e. negative cognitions and mood) (APA 2013).

DSM‐5 criteria for PTSD are as follows. The "A" criterion states that a person must be exposed to a catastrophic event involving actual or threatened death or injury, or a threat to the physical integrity of him/herself or others (for example, sexual violence) for the event to be regarded as a trauma. The "B" criterion (i.e. intrusive recollection) includes symptoms that are distinctive and readily identifiable, like panic, terror, dread, grief, or despair. These symptoms manifest during the daytime as intrusive images, traumatic nightmares, and flashbacks. The "C" criterion (i.e. avoidance criterion) consists of behavioural strategies used by people with PTSD to reduce trauma‐related events. Symptoms included in the "D" criterion reflect negative cognitions and moods that have developed after exposure to the traumatic event (i.e. blame, anger, guilt, or shame). Symptoms included in the "E" criterion are from alterations in arousal or reactivity such as hypervigilance or paranoia. The "F" or duration criterion stipulates that symptoms must persist for at least one month before PTSD may be diagnosed. Within the "G" criterion (i.e. functional significance criterion) the survivor must experience significant social, occupational, or other distress as a result of these symptoms, and in the "H" criterion (or exclusion criterion), these symptoms cannot be due to medication use, substance use, or other illnesses (APA 2013).

Further, epidemiological research using DSM criteria for PTSD has determined that the disorder is highly prevalent in a wide range of settings, particularly in those people who have been exposed to significant traumas (Breslau 1991; Kessler 1995; Koenen 2017). Estimates from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication indicate lifetime PTSD prevalence rates of 3.6% and 9.7%, among men and women in the USA, respectively (Kessler 2005). In the World Mental Health Survey (WMHS), prevalence rates are high in low‐, middle‐, and high‐income countries, with differences in gender prevalence again seen (Koenen 2017). Higher rates of PTSD have been reported in post‐conflict settings (De Jong 2001).

There is growing evidence that PTSD results in enormous personal and societal costs; this is based on chronicity of symptoms, high comorbidity of psychiatric and medical disorders, marked functional impairment, and estimations of economic costs (Brunello 2001; Koenen 2017; Solomon 1997). Furthermore, PTSD may be characterised by specific psychobiological dysfunctions mediated by neurobiological mechanisms, which may in turn be targeted by specific preventive and therapeutic pharmacological interventions (Amos 2014; Bernardy 2017; Charney 1993). There is certainly growing evidence in PTSD for specific dysregulations of neurotransmitter systems (including the serotonin, noradrenaline, and dopamine systems) and neuroendocrine systems (including the hypothalamus‐pituitary‐adrenal axis), as well as for structural and functional neuroanatomical abnormalities (Bremner 2004; Canive 1997; Charney 1993; Connor 1998; Sherin 2011; Yehuda 1995).

Prior psychological trauma plays a causal role in PTSD, and psychotherapy has been widely deployed in its management. Although psychodynamic psychotherapy has long been the mainstay of treatment, there have been few controlled studies of this modality (Brom 1989; Gersons 2000; Gilboa‐Schechtman 2010). The value of so‐called psychological debriefing in the immediate aftermath of trauma remains to be proven (Rose 1998; Rose 2002). Indeed, there is evidence that acute post‐trauma debriefing may worsen PTSD symptoms, prompting guidelines to advise against its use (Gist 2015). Nevertheless, there is a growing body of evidence demonstrating that cognitive‐behavioural and similar psychotherapies are indeed effective in the treatment of PTSD (Bisson 2007; Bradley 2005; Harvey 2003; NICE 2018; Watkins 2018).

Whereas in older models medications might be valuable primarily as an adjunct to psychotherapy techniques in post‐traumatic reactions (Sargent 1940), contemporary psychobiological theory speculates that comorbid substance use in PTSD may represent an attempt at 'self‐medication' and that prescribed medication may be able to play a primary role in preventing or reversing the dysfunctions of PTSD (Charney 1993; Charney 2004; Ressler 2018). PTSD frequently includes comorbid disorders such as major affective disorders, dysthymia, alcohol or substance abuse disorders, anxiety disorders, or personality disorders (Friedman 2016). Certain of these comorbid conditions are known to respond to medication (Kessler 1995; Kessler 2005). Indeed, the position that medication treatment may be useful in PTSD seems to have gained gradually increasing acceptance (Asnis 2004; Baldwin 2014; Connor 1998; Cyr 2000; Davidson 2000; Foa 1999; Marshall 1996; Marshall 1998a; Marshall 2000; Ursano 2004; Shalev 1996).

Description of the intervention

Early reports of the pharmacotherapy of PTSD focused on the tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and the irreversible monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) (Basoglu 1992; Bleich 1986; Burstein 1984; Chen 1991; Davidson 1987; Davidson 1989; Falcon 1985; Frank 1988; Hogben 1981; Irwin 1989; Kosten 1991; Lerer 1987; Olivera 1990; Milanes 1984; Reist 1989; Rubin 1993; Shestatzky 1988; White 1983). More recent work has focused on the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (Brady 2000; Davidson 2001b; Hertzberg 2000; Marshall 1998b; Martenyi 2002a; Smajkic 2001; Tucker 2001; Tucker 2003; Zohar 2002), selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) (Davidson 2006a; Davidson 2006b) and the serotonin antagonists and reuptake inhibitors (SARIs) (Davis 2004; Hertzberg 1996; Hertzberg 1998; Hidalgo 1999; Liebowitz 1989).

Several other antidepressants have also been studied (Baker 1995; Canive 1998; Connor 1999b; Davidson 1998; Davidson 2003; Davis 2000; Davis 2008; Hamner 1998; Katz 1994; Neal 1997). In addition, benzodiazepines (Braun 1990; Dunner 1985; Lowenstein 1988), beta‐blockers (Famularo 1988; Kolb 1984), buspirone (Duffy 1992; Duffy 1994; LaPorta 1992; Fichtner 1994; Simpson 1991; Wells 1991), clonidine (Harmon 1996; Kolb 1984; Kinzie 1989), guanfacine (Davis 2008; Horrigan 1996), cyprohepadine (Brophy 1991; Gupta 1998), d‐cycloserine (Heresco‐Levy 2002), inositol (Kaplan 1996), mood‐stabilisers (Fesler 1991; Fichtner 1990; Ford 1996; Forster 1994; Hertzberg 1999; Keck 1992; Looff 1995; Szymanski 1991), typical (Bleich 1986; Dillard 1993) and atypical neuroleptics (Butterfield 2001; Burton 1999; Hamner 1996; Izrayelit 1998; Leyba 1998), opioids (Glover 1993), and the alpha‐blocker prazosin (Raskind 2018) have also received attention.

How the intervention might work

SSRIs and SNRIs are considered first‐line agents for the treatment of PTSD (Baldwin 2014; Bandelow 2008; Ipser 2012). These antidepressants increase serotonin output by blocking the serotonin transporter (SERT) and are effective in reducing symptoms of anxiety and fear (Stahl 2013). There are currently six SSRIs globally available for the treatment of PTSD symptoms: namely, sertraline, paroxetine, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, citalopram, and escitalopram. Only two (sertraline and paroxetine) are FDA‐approved (Ravindran 2009). Similarly, the serotonin 1A (5HT1A) partial agonist, buspirone, has potential anxiolytic actions. These could theoretically be due to this agent's 5HT1A partial agonist actions at both presynaptic and postsynaptic 5HT1A receptors, with actions at both sites resulting in enhanced serotonergic activity in projections to the amygdala, prefrontal cortex, striatum, and thalamus. SSRIs and SNRIs theoretically operate using similar mechanisms. Since the onset of anxiolytic action for buspirone is delayed, this has led to the belief that 5HT1A agonists exert their therapeutic effects by adaptive neuronal events and receptor events, rather than simply by the acute occupancy of 5HT1A receptors. In this way, the presumed mechanism of action of 5HT1A partial agonists is analogous to the SSRIs, which also demonstrate delayed onset of action, and are also presumed to act by adaptations in neurotransmitter receptors. These delayed medication effects can be compared to the relatively rapid effect of the benzodiazepine anxiolytics, which act relatively acutely by occupying benzodiazepine receptors (Stahl 2013). The serotonin antagonist and reuptake inhibitor, nefazodone, is an older antidepressant that is thought to work through post‐synaptic 5‐HT2A receptor antagonism, inhibition of presynaptic serotonin and norepinephrine (NE) reuptake, and through blocking α1 receptors. Nefazodone is now rarely used, due to concerns of hepatotoxicity (Ravindran 2009). Liebowitz 1989 reviewed the clinical efficacy of trazodone (50 – 250 mg/day) in treating 22 patients with a dual diagnosis of substance abuse and anxiety symptoms. A substantial number of people suffered from symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Improvement was noted in all participants within the first month of treatment, and most reported symptomatic improvement after each dose of trazodone, resulting in an as‐needed pattern of usage.

Benzodiazepines, as a class, work on the central nervous system (CNS) through their effects on the GABAA receptors. Activation at the special benzodiazepine receptor site on the GABAA receptor promotes enhanced activity of the inhibitory neurotransmitter γ‐aminobutyric acid (GABA), thus resulting in various effects including: anxiolysis, sedation, muscle relaxation, cognitive effects, and anticonvulsant actions. These functions, and particularly the first two, would seem to have benefits for PTSD (Ravindran 2009).

Anti‐adrenergic agents or beta‐blockers or both target putative noradrenergic alterations seen in PTSD. Clonidine, for example, is commonly used as an antihypertensive agent, and is a centrally‐acting α2 adrenergic agonist that works to decrease sympathetic tone. As such, it was theorised to have potential effects on the hyperarousal symptoms seen in PTSD. Guanfacine, another α2 adrenergic agonist with a similar mechanism of action, has also been investigated, but no benefit has been reported (Davis 2008; Neylan 2006). The use of β‐adrenergic antagonists has also been investigated in PTSD, but primarily for a role in the secondary prevention of this disorder. Cahill 1994 demonstrated that a single dose of propranolol administered to healthy humans impaired subsequent recall of an emotionally‐arousing story but not for an emotionally‐neutral one, thus lending support for the theory that memory for emotional experiences involved the β‐ adrenergic system. Based on this, it was theorised that administration of a β‐adrenergic antagonist in the peritraumatic period might have a beneficial effect in blocking consolidation of the traumatic memory and thus prevent development of PTSD (Ravindran 2009).

Anticonvulsant medications, with their putative anti‐kindling effects, have been investigated for PTSD, although most of the evidence for use of these agents (e.g. carbamazepine and divalproex) is not well researched (Ravindran 2009; Ressler 2018).

TCAs are non‐specific in their actions on specific neurotransmitters, with their primary mechanism of action involving varying degrees of serotonin and NE reuptake inhibition. MAOIs, on the other hand, work by irreversibly inhibiting the enzyme monoamine oxidase, normally involved in metabolism of serotonin and NE. Both medication classes are generally considered second‐ or third‐line treatments due to their adverse event profile and need for dietary restriction (i.e. MAOIs) (Ravindran 2009).

Only a small number of controlled trials have investigated the adjunctive use of antipsychotic agents (which include olanzapine, risperidone, quetiapine, ziprasidone, and aripiprazole) in PTSD, and even fewer have explored their use as monotherapy (Ravindran 2009). Other agents like D‐cycloserine (DCS), a partial agonist at the NMDA receptor, have also been investigated as a potential treatment for PTSD. Arguing that the presence of flashbacks and intrusive memories in PTSD may be a function of extinction failure, and that learning and memory are both glutamate‐dependent processes, Heresco‐Levy 2002 and colleagues argued that enhancing glutamate transmission could facilitate the learning of new memories to replace the traumatic ones (as cited in Ravindran 2009). The addition of cyproheptadine, taken orally at night, has also been shown to control and decrease the intensity and frequency of nightmares (Brophy 1991; Gupta 1998). Similarly, 18 chronic posttraumatic stress disorder combat veterans who received the opioid nalmefene showed a favourable response, with a marked decrease of emotional numbing and other symptoms of PTSD, including startle response, nightmares, flashbacks, intrusive thoughts, rage and vulnerability as the dosage increased (Glover 1993). There was also evidence reported by studies assessing the mood‐stabilisers carbamazepine (Lipper 1986), valproate (Fesler 1991), lithium (Forster 1994), lamotrigine (Hertzberg 1999), and prazosin (Raskind 2018). There was, however, no significant difference found in the improvement score for inositol compared to placebo (Kaplan 1996).

Why it is important to do this review

A systematic review of studies of pharmacotherapy for PTSD is useful in tackling several questions for the field. First, is pharmacotherapy in fact an effective form of treatment in PTSD? Given the preponderance of psychological models and evidence for the efficacy of certain forms of psychotherapy in PTSD (Bisson 2013), the role of pharmacotherapy remains debatable for many. In a recently‐published guideline for the treatment of PTSD, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends that preference be given to trauma‐focused psychological therapy over pharmacotherapy as a routine first‐line treatment for this disorder (NICE 2018).

Second, are certain medication classes more effective in the treatment of symptoms and/or more acceptable to the patient in terms of adverse events than others? The use of novel agents (such as prazosin) for PTSD in recent years raises the question of how these compare with older agents. Early recommendations, such as the expert consensus guideline series for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (Foa 1999), suggested that the SSRIs, the serotonin modulator nefazodone, and the SNRI venlafaxine are first‐line medications for the treatment of PTSD, with benzodiazepines and mood‐stabilisers having a role in people with certain kinds of symptoms. More recent recommendations have highlighted paroxetine, mirtazapine, amitriptyline and phenelzine (NICE 2018). Support for such recommendations requires ongoing assessment of the literature on RCTs.

Third, can a systematic review of RCTs provide information about the most important factors affecting pharmacotherapy response? Clinical factors, such as the kind of pre‐existing trauma (e.g. combat‐related or not) and the presence of comorbid depression have all been suggested to play a role (Davidson 1993; Davidson 2000; Marshall 1998b; Van der Kolk 1994). It is possible that the database of RCTs in PTSD may include information about these variables.

Several reviews of the pharmacotherapy of PTSD have indeed been published in recent years (Albucher 2002; Asnis 2004; Hoskins 2015; Ipser 2012). These reviews have been useful in summarising the existing research, pointing to methodological flaws, and outlining areas for future research. Nevertheless, not all reviews have employed a systematic search strategy, and it has been suggested that even MEDLINE searches may miss over half of all RCTs in specialised health care journals (Hopewell 2002). Furthermore, not all studies have provided estimates of the effects of medication (Davidson 1997a; Penava 1996). Finally, not all reviews in this area have adhered to Cochrane Collaboration (Mulrow 1997) or similar (Moher 1999) guidelines for systematic identification of trials, investigation of sources of heterogeneity, measurement of methodological quality, and estimation of the effects of intervention.

The authors therefore updated a systematic review of RCTs of the pharmacotherapy of PTSD in adults, previously published in 2000 and 2006 (Stein 2000; Stein 2006), following Cochrane guidelines and software (Higgins 2011; RevMan 2020).

Objectives

To assess the effects of medication for reducing PTSD symptoms in adults with PTSD.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We considered randomised controlled trials (placebo‐controlled and comparative trials) for inclusion. We also considered unpublished reports, abstracts, and brief and preliminary reports. We did not use differences between trials (for example, sample size, trial duration or language) to exclude studies. We also included cluster‐randomised controlled trials, cross‐over trials and multiple treatment trials in the analyses.

Types of participants

Participant characteristics

We included all studies of adult participants (aged 18 to 85 years) diagnosed with PTSD (as determined by the study author), irrespective of diagnostic criteria and measure, duration and severity of PTSD symptoms, and gender. These descriptors were, however, tabulated in order to address the question of their possible impact on the effects of medication.

We included adults on concomitant medications in the review, but we excluded adults on concomitant psychotherapy.

Comorbidities

We placed no restrictions on the presence of comorbid disorders secondary to PTSD.

Setting

We placed no restrictions by setting.

Subsets of participants

We excluded studies that reported a subset of participants that met the review inclusion criteria, to preserve randomisation.

Types of interventions

The review focuses only on medication treatments, in which the comparator was a placebo (active or non‐active) or other medication (i.e. control group). A parallel review of the psychotherapy of PTSD has been completed by a Cochrane team (Bisson 2007; Bisson 2013). More recently, a Cochrane review of RCTs of medication prophylaxis for PTSD has been published (Amos 2014).

This review classifies medications based on their putative mechanisms of action (taken from CCMD antidepressant classification map) (Davies 2015), and they do not necessarily map onto the drug classification schemes used in other reviews.

Experimental interventions

We grouped specific pharmacological interventions by medication class, listed below:

Alpha‐blockers (e.g. prazosin)

Anticonvulsants (e.g. tiagabine, divalproex, lamotrigine, and topiramate)

Antihistamines (e.g. hydroxyzine)

Antipsychotics (e.g. olanzapine, risperidone and quetiapine)

Benzodiazepines (e.g. alprazolam)

Dopamine beta‐hydroxylase inhibitors (e.g. nepicastat)

Hypnotics (e.g. eszopiclone)

Mono‐amine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs, e.g. phenelzine)

NK‐1 receptor antagonists (e.g. orvepitant)

NMDA receptor antagonists (e.g. ketamine)

Norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitors (NDRIs, bupropion SR)

Noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (NARs, e.g. reboxetine)

Noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressants (NaSSAs, e.g. mirtazapine)

Other medications (e.g. ganaxolone, GR205171, GSK561679)

Reversible inhibitor of monoamine oxidase A (RIMA, e.g. brofaromine)

Second messenger system precursors (e.g. inositol)

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs, e.g. paroxetine, fluvoxamine, sertraline, fluoxetine, and citalopram)

Serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI, e.g. venlafaxine)

Serotonin antagonist and reuptake inhibitors (SARI, e.g. nefazodone)

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs, e.g. amitriptyline, desipramine and imipramine)

Comparator interventions

Placebo (active or non‐active)

Medication (control)

We placed no restrictions on timing, dosage, duration, or co‐interventions.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

-

Treatment efficacy

Treatment response (responders versus non‐responders) was determined from the Clinical Global Impressions Scale ‐ Improvement Item (CGI‐I). The CGI‐I ranges from 1 (normal, not at all ill) to 7 (among the most extremely ill patients). In this review, responders were defined on the CGI‐I as those with a score of 1 = "very much" or 2 = "much" improved (Guy 1976). Given that the CGI‐I is a widely‐used global outcome measure in RCTs of PTSD, this instrument served as a robust measure of the clinical value of treatment in PTSD (Davidson 1997b).

-

Treatment tolerability ‐ dropouts due to treatment‐emergent adverse events

The total proportion of participants who withdrew from the RCTs due to treatment‐emergent adverse events was included in the analysis as a surrogate measure of medication acceptability, in the absence of other more direct indicators of acceptability.

Secondary outcomes

-

Reduction of PTSD symptoms

Reduction in PTSD symptoms was determined from the total score on the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) (Blake 1990), a symptom‐severity measure that is increasingly used in RCTs of PTSD. The CAPS is designed to make a categorical PTSD diagnosis which corresponds to the DSM‐IV criteria. A "1, 2" rule is used to determine a diagnosis, whereby a frequency score of 1 (scale 0 = "none of the time" to 4 = "most or all of the time") and an intensity score of 2 (scale 0 = "none" to 4 = "extreme") is required in order to meet specific symptom criteria (Weathers 1999, as cited in the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies).

PTSD symptom reduction was assessed for those trials which used other continuous measures of symptom severity besides the CAPS, as well as from summary statistics from self‐rated scales such as the Impact of Events Scale (IES) (Horowitz 1979), and the Davidson Trauma Scale (DTS) (Davidson 1997c). The IES evaluates the distress that is caused by traumatic events and is centred around two subscales (i.e. intrusion and avoidance). The IES is a 22‐item self‐report scale in which respondents choose options from 1 to 5. The DTS is a 17‐item self‐report measure that assesses the 17 DSM‐IV symptoms of PTSD. Items are rated on a 5‐point frequency (0 = "not at all" to 4 = "every day") and severity scale (0 = "not at all distressing" to 4 = "extremely distressing"). The scores range from 0 to 136.

Self‐rated scales were frequently the only outcome measures used in older trials and may continue to have a role in clinical practice. The efficacy of medication in alleviating symptoms within the three symptom clusters characteristic of PTSD (re‐experiencing/intrusion, avoidance/numbing, and hyperarousal) was determined using the CAPS‐B, CAPS‐C, and CAPS‐D subscales of the CAPS, as well as the relevant subscales of the self‐rated outcome measures.

-

Reduction in depressive symptoms

The reduction of comorbid symptoms was measured by depression scales, such as the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (Beck 1961), the Hamilton Depression scale (HAM‐D) (Hamilton 1960), and the Montgomery‐Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) (Montgomery 1979).

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) is a 21‐question multiple‐choice self‐report, one of the most widely used psychometric tests for measuring the severity of depression. A score of 0 to 9 indicates minimal depression, 10 to 18 mild depression, 19 to 29 moderate depression, and 30 to 63 severe depression. The Hamilton Depression scale (HAM‐D) is a multiple‐item questionnaire with 17 to 29 items (depending on the version). Patients are rated on a 3‐ or 5‐point scale. A score of 0 to 7 is normal and a score of 20 or higher moderate, severe, or very severe. The MADRS is a 10‐item diagnostic questionnaire which psychiatrists use to measure the severity of depressive episodes in patients with mood disorders. A higher MADRS score indicates more severe depression, and each item yields a score of 0 to 6. The overall scores range from 0 to 60. Usual cut‐off points are 0 to 6 ‐ normal/symptom absent; 7 to 19 ‐ mild depression; 20 to 34 ‐ moderate depression; and more than 34 ‐ severe depression.

-

Reduction in anxiety symptoms

The reduction of comorbid symptoms was measured by anxiety scales, such as the Covi Anxiety Scale (CAS) (Covi 1984) and the Hamilton Anxiety scale (HAM‐A) (Hamilton 1959).

The Covi Anxiety Scale is a three‐item scale along with three separate dimensions: verbal report, behaviour, and somatic symptoms of anxiety, and each dimension is rated on a 1‐to‐5 spectrum (1 = “not at all” to 5 = “very much”). The HAM‐A consists of 14 items and measures both psychic anxiety (mental agitation and psychological distress) and somatic anxiety (physical complaints related to anxiety). Each item is scored on a scale of 0 (not present) to 4 (severe), with a total score range of 0 to 56, where less than 17 indicates mild severity, 18 to 24 mild‐to‐moderate severity, and 25 to 30 moderate‐to‐severe.

-

Functional disability

Functional disability as measured by the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS), which includes subscales to assess work, social and family‐related impairment (Sheehan 1996), was also included, when provided, to address the question of medication effectiveness. The Sheehan Disability Scale is a composite of three self‐rated items designed to measure the extent to which three major sectors in the patient’s life are impaired by panic, anxiety, phobic, or depressive symptoms. The patient rates the extent to which his or her 1) work, 2) social life or leisure activities, and 3) home life or family responsibilities are impaired by his or her symptoms on a 10‐point visual analogue scale. The numerical ratings of 0‐to‐10 can be translated into a percentage if desired. The three items may be summed into a single dimensional measure of global functional impairment that ranges from 0 (unimpaired) to 30 (highly impaired).

-

Treatment tolerability ‐ dropouts due to any cause

Dropout rates due to any cause were also compared in order to provide some indication of treatment effectiveness.

Main comparisons

We assessed the following outcomes and grouped them by specific pharmacological interventions according to medication class:

Comparison 1: Alpha‐blockers versus placebo.

Comparison 2: Anticonvulsants versus placebo.

Comparison 3: Antipsychotics versus placebo.

Comparison 4: Benzodiazepines versus placebo.

Comparison 5: Dopamine beta‐hydroxylase inhibitors versus placebo.

Comparison 6: Ganaxolone versus placebo.

Comparison 7: GR205171 versus placebo.

Comparison 8: GSK561679 versus placebo.

Comparison 9: Hypnotics versus placebo

Comparison 10: MAOIs versus placebo.

Comparison 11: NaSSAs versus placebo.

Comparison 12: NK‐1 receptor antagonists versus placebo.

Comparison 13: RIMAs versus placebo.

Comparison 14: SARIs versus placebo.

Comparison 15: SNRIs versus placebo.

Comparison 16: SSRIs versus placebo.

Comparison 17: TCAs versus placebo.

Comparison 18: Total effect of medication versus placebo.

Comparison 19: Head‐to‐head comparisons.

Comparison 20: Subgroup analyses ‐ Methodological criteria.

Comparison 21: Subgroup analyses ‐ Clinical criteria.

Comparison 22: Sensitivity analyses.

Comparison 23: Publication bias.

Search methods for identification of studies

Cochrane Specialised Register (CCMDCTR) The Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Group maintains a comprehensive, specialised register of randomised controlled trials, the CCMDCTR (to 13 November 2020). The register contains over 39,000 reference records (reports of RCTs) for anxiety disorders, depression, bipolar disorder, eating disorders, self‐harm and other mental disorders within the scope of this Group. The CCMDCTR is a partially studies‐based register with more than 50% of reference records tagged to about 12,500 individually PICO‐coded study records. Reports of trials for inclusion in the register were collated from (weekly) generic searches of MEDLINE (1950‐), Embase (1974‐) and PsycINFO (1967‐), quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and review‐specific searches of additional databases. Reports of trials were also sourced from international trial registries, drug companies, the handsearching of key journals, conference proceedings and other (non‐Cochrane) systematic reviews and meta‐analyses. Details of CCMD’s core search strategies (used to identify RCTs) can be found on the Group’s website with an example of the core MEDLINE search displayed in Appendix 1.

Electronic searches

An information specialist with the Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Group searched the following databases using keywords, subject headings and search syntax appropriate to each resource. The date of the latest, full search is 13 November 2020.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2020, issue 11) in the Cochrane Library (searched 13 November 2020);

Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Controlled Trials Register (CCMDCTR) (all years to June 2016);

Embase Ovid (1974 to 2020 Week 46);

MEDLINE ALL, Ovid (1946 to November 13, 2020);

PsycINFO Ovid (all years to November Week 46 2020);

PTSDPubs Proquest (previously PILOTS: Published International Literature On Traumatic Stress) (all years to 16 November 2020);

ClinicalTrials.gov (https://clinicaltrials.gov/);

WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/).

The searches have been through a number of iterations over the years, initially concentrating on terms for population and intervention (+ RCT filter), across the main bibliographic databases either directly or via the Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Controlled Trials Register (Appendix 1).

As the number of different pharmacological interventions used to treat PTSD expanded beyond the traditional psychotropic drugs, an information specialist ran searches for population only, RCTs (CCMDCTR, all available years; key bibliographic databases, 2014 onwards) (Appendix 2). The search results were pre‐sifted (in duplicate), to weed out the non‐RCTs, prior to passing on the records on to the author team. The population only search, was designed to capture studies for a number of reviews within the CCMD group, for the treatment or prevention of PTSD.

We (the author team) undertook our own searches, initially using a broad strategy to find not only RCTs, but also open‐label trials, as well as journal and chapter reviews of the pharmacotherapy of PTSD in adults (Appendix 3).

Searching other resources

Reference Lists

We sought additional RCTs in reference lists of the retrieved articles.

Personal communication

We also obtained published and unpublished trials from key researchers, who were identified by the frequency with which they were cited in the bibliographies of RCTs and open‐label studies.

Data collection and analysis

We used Review Manager 5 (RevMan 5) to perform all analyses reported in this review (RevMan 2020).

Selection of studies

RCTs identified from the search were independently assessed for inclusion by three review authors (TW, JI and NP), based on information included in the abstract or the main body of the trial report, or both. We collated RCTs which we regarded as satisfying the inclusion criteria specified in the Data extraction and management and Criteria for considering studies for this review. Studies for which additional information was required in order to determine their suitability for inclusion in the review have been listed in the Characteristics of studies awaiting classification table, pending the availability of this information. We resolved any disagreements in assessment and collation by discussion with a fourth review author (DS).

Data extraction and management

We designed spreadsheet forms to record descriptive information, summary statistics of the outcome measures, the quality scale ratings, and associated commentary.

We collated the following information from each trial (additional information can be found in the Characteristics of included studies tables, but not all extracted data are reported in this review):

Description of the trials, including the primary researcher, the year of publication, and the source of funding.

Characteristics of the interventions, including the number of participants randomised to the treatment and control groups, the number of total dropouts per group as well as the number that dropped out due to adverse effects, the dose of medication and the period over which it was administered, and the name and class of the medication (e.g. SSRIs, TCAs, MAOIs and 'other medication).

Characteristics of trial methodology, including the diagnostic (e.g. DSM‐IV (APA 1994)) and exclusion criteria used, the screening instrument used (e.g. the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM‐IV (SCID) (Spitzer 1996)) for both the primary and comorbid diagnoses, the presence of comorbid major depressive disorders (MDDs), the use of a placebo run‐in or of a minimal severity criterion, the number of centres involved, and the trial's methodological quality (see below).

Characteristics of participants, including gender distribution and mean and range of ages, mean length of time with PTSD symptoms, whether they had been treated with the medication in the past (treatment naïvety), the number of participants in the sample with MDD, the number who experienced combat trauma, and the baseline severity of PTSD, as assessed by the trial's primary outcome measure or another commonly‐used scale.

Outcome measures employed (primary and secondary), and summary continuous (means and standard deviations (SD)) and dichotomous (number of responders) data. Additional information included whether data reflected the intention‐to‐treat (ITT) with last observation carried forward (LOCF) or mixed methods (MM) sample, or whether a completer/observed cases (OC) sample was reported.

Where information was missing, the review authors contacted investigators by email to obtain this information.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed the risks of bias of each included study using the Cochrane risk of bias tool (Higgins 2011), based on consideration of the following six domains:

Random sequence generation: did investigators use a random‐number table or a computerised random‐number generator?

Allocation concealment: was the medication sequentially numbered, sealed, and placed in opaque envelopes?

Blinding of participants, personnel, and outcome assessors for each main outcome or class of outcomes: was knowledge of the allocated treatment or assessment adequately blinded during the study?

Incomplete outcome data for each main outcome or class of outcomes: were missing or excluded outcome data adequately addressed?

Selective outcome reporting: were the reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting? Such a judgement could only be made based on the availability of the protocol.

Other sources of bias: was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a high risk of bias?

Three independent review authors (TW, JI and NP) assessed and extracted the risks of bias for the included studies. We discussed any disagreements with a fourth review author (DS). Where necessary, we contacted the authors of the studies for further information. The review authors made a judgement on the risk of bias for each domain within and across studies, based on the following three categories: ’low’ risk of bias, ’unclear’ risk of bias, and ’high’ risk of bias. All risk of bias data are graphically presented and described in the text.

Measures of treatment effect

Categorical data

Relative risk (RR) of failure to respond to treatment was used as the summary statistic for the dichotomous outcome of interest (CGI‐I or related measure). We used the RR instead of the odds ratio, as odd ratios tend to underestimate the size of the treatment effect when the occurrence of the adverse outcome of interest is common (as was the case in this review, with an anticipated non‐response greater than 20%) (Deeks 2003; Deeks 2011), and because of the greater ease with which this statistic can be interpreted.

Continuous data

We calculated weighted mean differences (WMDs) for continuous summary data obtained from studies that used the CAPS. Alternatively, in cases in which a range of scales were used, such as in the assessment of symptom severity on the self‐rated IES and DTS scales, we determined the standardised mean difference (SMD). This method of analysis standardises the differences between the means of the treatment and control groups in terms of the variability observed in the trial.

In the case of data from trials using multiple fixed doses of medication, we avoided the bias introduced through comparing the summary statistics for multiple groups against the same placebo control by pooling the means and standard deviations across all the treatment arms as a function of the number of participants in each arm. In addition, when including summary statistics from the self‐rated scales, we preferred data from the DTS over the IES in trials which used both scales, given the inclusion in the former of a subscale assessing the hyperarousal symptom cluster (Weiss 1997), and concerns about the psychometric properties of the IES subscales (Creamer 2003).

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

In cluster‐randomised trials, groups of individuals, rather than individuals themselves, are randomised to different interventions. Analysing treatment response in cluster‐randomised trials without taking these groupings into account could be problematic, as participants within any one cluster often tend to respond in a similar manner, and thus analyses cannot assume that participants’ data are independent of the rest of the cluster. Cluster‐randomised trials also face additional risk‐of‐bias issues including recruitment bias, baseline imbalance, loss of clusters, and non‐comparability with trials randomising individuals (Higgins 2011). No cluster‐randomised trials were eligible for inclusion in this review.

Cross‐over trials

Cross‐over trials were only included in the calculation of summary statistics when it was (a) possible to extract medication and placebo/comparator data from the first treatment period alone, or (b) when the inclusion of data from both treatment periods was justified through a wash‐out period of sufficient duration as to minimise the risk of carry‐over effects (a minimum of two weeks or longer in the case of trials assessing the efficacy of agents with extended half‐lives, such as the SSRI, fluoxetine (Gury 1999)). In the latter case, data from both periods were only included when it was possible to determine the correlation between participants' responses to the interventions in the different phases (Elbourne 2002).

Multiple treatment groups

A few trials included in this review compared more than two intervention groups or multiple doses of the same medication against placebo. Including data from the same placebo group for these studies repeatedly in the same comparison would result in a unit‐of‐analysis error (Higgins 2011). To prevent these errors for trials comparing multiple dosages of the same agent to placebo, we averaged the mean and standard deviation of the outcome of interest across dosage groups. We included outcome data from multiple treatment arms in the same comparison if the agents tested were from different medication classes. We turned off the subtotals of the outcome if the placebo group appeared twice in the analysis to accommodate the second medication. In the case of trials testing multiple agents from the same classes, and in calculating the total effect across all medication classes, we restricted data from multi‐arm RCTs to the agent that was least represented in the database.

Dealing with missing data

All analyses of dichotomous data were intention‐to‐treat (ITT) and data from trials providing information on the original group size (prior to dropouts) were included in the analyses of treatment efficacy. We preferred within studies the inclusion of summary statistics for continuous outcome measures derived from mixed‐effects models, followed by last observation carried forward (LOCF) and observed cases (OC) summary statistics, in that order. This is in line with evidence that mixed‐effects methods are more robust to bias than LOCF analyses (Verbeke 2000).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed heterogeneity of treatment response, i.e. whether the differences between the results of trials were greater than would be expected by chance alone, visually from the forest plot of the RR. It was also determined by means of the Chi2 test of heterogeneity, with a significance level of less than 0.10 interpreted as evidence of heterogeneity, given the low power of the Chi2 statistic when the number of trials is small (Deeks 2003).

In addition, we used the I2 heterogeneity statistic reported by RevMan to test the robustness of the Chi2 statistic to differences in the number of trials included in the groups being compared within each subgroup analysis (Higgins 2003). Differences in treatment response on the CGI‐I were determined by whether the confidence intervals for the effect sizes of the subgroups overlapped. We chose this method in preference to the stratified test, due to inaccuracies in the calculation in RevMan of the Chi2 statistic for dichotomous measures (Deeks 2003; Deeks 2011).

Thresholds for the interpretation of I2 can be misleading, since the importance of inconsistency depends on several factors. The review follows a rough guide for interpretation:

0% to 40%: might not be important.

30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity.

50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity.

75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

Funnel plots provide a graphic illustration of the effect estimates of an intervention from individual studies against some measure of the precision of that estimate. We determined publication bias by visual inspection of a funnel plot of treatment response, with the consideration of confounding selection bias, poor methodological quality, true heterogeneity, artefact, and chance. Given that this calculation is dependent on having 10 trials per outcome, we could only calculate this for the SSRIs.

Data synthesis

We obtained summary statistics for categorical and continuous measures from a random‐effects model; this includes both within‐study sampling error and between‐studies variation in determining the precision of the confidence interval (CI) around the overall effect size, whereas the fixed‐effect model takes only within‐study variation into account. The summary statistics were expressed as an average effect size for each subgroup, as well as by means of 95% CIs.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We conducted subgroup analyses (Thomson 1994) in order to assess the degree to which methodological differences between trials might have systematically influenced differences observed in the primary treatment outcomes.

We grouped the trials according to the following methodological sources of heterogeneity:

The involvement of participants from a single centre or multiple centres. Single‐centre trials are more likely to be associated with lower sample size but with less variability in clinician ratings.

Whether or not trials were industry‐funded. In general, published trials which are sponsored by pharmaceutical companies appear more likely to report positive findings than trials which are not supported by for‐profit companies (Als‐Nielsen 2003; Baker 2003).

In addition, we used the following criteria to assess the extent of clinical sources of heterogeneity:

Whether or not the sample included combat veterans (this subgroup has been regarded as more resistant to treatment and is arguably more likely to have more chronic and severe symptoms, to have comorbid depression, and to be male). For the purposes of this review, those trials for which 10% or fewer of the sample consisted of war veterans were classified as non‐combat veteran RCTs.

Whether or not the sample included participants diagnosed with major depression. Such an analysis might assist in determining the extent to which the efficacy of a medication agent in treating PTSD is independent of its ability to reduce symptoms of depression, an important consideration given the classification of many of these medications as antidepressants.

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted sensitivity analyses, which determine the robustness of the review authors' conclusion and methodological assumptions made in conducting the meta‐analysis. Sensitivity analyses were conducted to determine whether treatment response on the CGI‐I differed as a result of:

Treatment response versus non‐response as the unit of comparison in determining medication efficacy. This comparison is regarded as necessary, given concerns that the former may result in less consistent summary statistics than the latter (Deeks 2002).

The exclusion of participants who were lost to follow‐up (LTF). This was determined through a 'worst case/best case' scenario (Deeks 2003). In the worst case, all the missing data for the treatment group were recorded as non‐responders, whereas in the best case, all missing data in the control group were treated as non‐responders (In the case of the one SSRI (Marshall 2007) and MAOI trial (Baker 1995) which only reported total LTF, the ratio of participants who dropped out in the medication and placebo groups was determined from the average ratio between these groups for those RCTs in the respective classes which did provide this information). Should the conclusions about treatment efficacy not differ between these two comparisons, we can assume that missing data in trial reports do not have a significant influence on outcome.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

The review authors compiled summary of findings tables to present the evidence for the primary outcomes of the review (i.e. number of responders and dropouts due to treatment‐emergent side effects). In addition, the following comparisons were prioritised and are presented in the summary of findings tables:

Comparison 1: Alpha‐blockers versus placebo.

Comparison 2: Antipsychotics versus placebo.

Comparison 3: MAOIs versus placebo.

Comparison 4: NaSSAs versus placebo.

Comparison 5: SNRIs versus placebo.

Comparison 6: SSRIs versus placebo.

Comparison 7: TCAs versus placebo.

We used the following six elements (Higgins 2011) to report this:

A list of all important outcomes, both desirable and undesirable;

A measure of the typical burden of these outcomes (e.g. illustrative risk, or illustrative mean, on control intervention);

Absolute and relative magnitude of effect (if both are appropriate);

Numbers of participants and studies addressing these outcomes

A grade of the overall quality of the body of evidence for each outcome

Space for comments.

The downgrading of the evidence rating for outcomes was based on five factors. Reasons for downgrading the evidence were classified as ’serious’ (downgrading the quality rating by one level) or ’very serious’ (downgrading the quality grade by two levels).

Limitations in the design and implementation of the trial.

Indirectness of evidence.

Unexplained heterogeneity or inconsistency of results.

Imprecision of results.

High probability of publication bias.

The review authors classified the quality of evidence for each outcome according to the following categories:

High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect;

Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate;

Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate;

Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

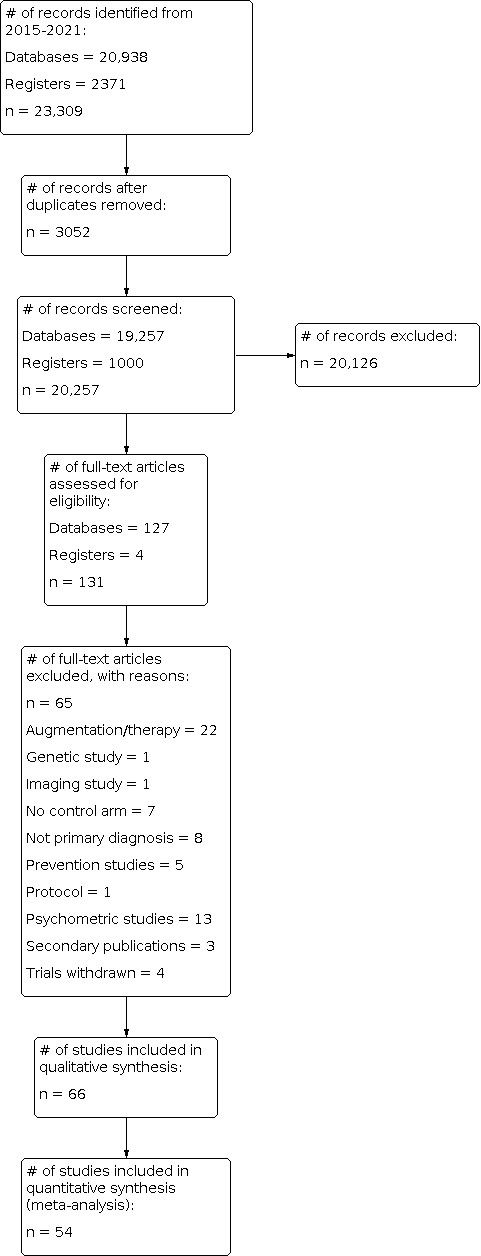

We found a total of 23,309 studies through the search process (CCMDCTR 3660; MEDLINE 2489; PsycINFO 6222; ClinicalTrials.org 2371; Embase 1984; PILOTS 792; Proquest PTSDpubs 194; PubMed 5597). After the removal of 3052 duplicates, we scanned 20,257 titles and abstracts (if provided) for eligibility, and of these, we ruled out 20,126 studies. One hundred and thirty one studies initially seemed relevant, but after independent review of the full‐text studies, 65 failed to meet our inclusion criteria (see Characteristics of excluded studies), leaving 66 RCTs eligible for inclusion in the review (see Characteristics of included studies and Figure 1). Of the 66 trials, the review included 54 RCTs in the meta‐analysis. Eighteen studies are awaiting classification, and one study is ongoing (see Characteristics of studies awaiting classification and Characteristics of ongoing studies).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

The review includes 66 RCTs of PTSD (7442 participants, age range: 18 to 82 years), four of which contained a maintenance component (Davidson 2001a, Marshall 2007, Martenyi 2002a, Van der Kolk 2007). Of the 66 trials, 58 were published, and all of these publications were in English. Pharmaceutical companies contributed funding for 35 of these trials. Twenty‐one studies were single‐centre trials, and 38 studies took place in multiple‐centres. There was insufficient information to determine the setting for the remaining seven trials. A placebo comparison group was used in all but six of the trials (McRae 2004 and Saygin 2002 compared nefazodone with the SSRI sertraline, while Smajkic 2001 compared the efficacy of the SSRIs sertraline, paroxetine and the SNRI venlafaxine). Chung 2004 assessed the efficacy and tolerability of mirtazapine against that of sertraline, Feder 2014 compared ketamine to midazolam (fixed 0.045 mg), and Spivak 2006 compared reboxetine (fixed 8 mg) to fluvoxamine (fixed 150 mg)). Of the remaining 60 RCTs, 26 of the trials included a SSRI treatment arm (one citalopram, dose range: 20 to 50 mg; eight fluoxetine, dose range: 10 to 80 mg; six paroxetine, dose range: 10 to 60 mg; 11 sertraline, dose range: 15 to 200 mg), two trials an alpha‐blocker intervention (prazosin, dose range: 1 to 15 mg; one of the trials included the antihistamine hydroxyzine, dose range: 10 to 100 mg), seven trials an anticonvulsant intervention (e.g. two tiagabine, dose range: 2 to 16 mg; two divalproex, dose range: 500 to 3000 mg; one lamotrigine, dose range: 25 to 500 mg; two topiramate, dose range: 25 to 400 mg), five trials an antipsychotic intervention (e.g. two olanzapine, dose range: 5 to 20 mg; two risperidone, dose range: 0.5 to 6 mg; one quetiapine, dose range: 25 to 800 mg), and three trials an experimental intervention (one ganaxolone, dose range: 200 to 600 mg; one GR205171, fixed 5 mg; one GSK561679, fixed 350 mg). The review also includes two trials with a MAOI intervention (phenelzine, dose range: 15 to 75 mg), one trial with a NaSSA intervention (mirtazapine, dose range: 15 to 50 mg); two trials with a RIMA intervention (brofaromine, dose range: 50 to 150 mg), one trial with a SNRI intervention (venlafaxine, dose range: 75 to 300 mg), and three trials with a TCA intervention (one amitriptyline, dose range: 50 to 200 mg; one desipramine, dose range: 50 to 200 mg; one imipramine, dose range: 50 to 300 mg). Single trials included a benzodiazepine (alprazolam, dose range: 1.5 to 6 mg) treatment arm, a dopamine beta‐hydroxylase inhibitor (nepicastat, dose range: 100 to 800 mg) treatment arm, a NK‐1 receptor antagonist (orvepitant, fixed 60 mg) treatment arm, a hypnotic (eszopiclone, dose 3 mg) treatment arm, and a second messenger system precursor (inositol, fixed 12 grams) treatment arm. The review also includes one trial investigating the norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitor bupropion SR (dose range: 100 to 300 mg).