Abstract

Background and Objectives

To expand the phenotype and genotype associated with PCYT2-related disorder.

Methods

Exome sequencing data from a patient with molecularly undiagnosed complex spastic paraplegia and axonal motor and sensory polyneuropathy were analyzed. Clinical data and nerve conduction studies of the patient and his affected brother were collected, and their phenotype and genotype were compared with previously reported patients with PCYT2-related disorder.

Results

A novel homozygous missense variant in PCYT2 (NM_001184917.2) c.88T>G; p.(Cys30Gly) was identified. This variant is located in a highly conserved tyrosine kinase site and is predicted damaging by several variant annotation tools. Both patients reported here and the previously published patients share several phenotypic features, including short stature, spastic tetraparesis, cerebellar ataxia, epilepsy, and cognitive decline. Axonal polyneuropathy, diagnosed in both brothers, was not previously reported.

Discussion

This family with a novel PCYT2 variant expands the clinical spectrum of PCYT2-related disorder to include axonal motor and sensory polyneuropathy and the genetic spectrum to include the variant located in the first catalytic domain, whereas all previously reported variants are located in the second catalytic domain. Further research is required to disentangle the underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms, leading to the complex phenotype of PCYT2-related disorder.

Lipid metabolic pathways play an important role in the etiology of the motor neuron diseases, a group of clinically and genetically heterogeneous disorders characterized by the progressive degeneration of upper and/or lower motor neurons.1 Biallelic pathogenic variants in PCYT2 encoding CTP:phosphoethanolamine cytidylyltransferase (ET), the rate-limiting enzyme in phosphoethanolamine biosynthesis, have recently been associated with a clinical spectrum ranging from pure to complex spastic paraplegia syndrome, characterized by spastic tetraparesis, intellectual disability, short stature, progressive cerebral and cerebellar atrophy, epilepsy, and ophthalmologic abnormalities.2-6

Here, we report 2 patients, adult brothers, with a homozygous missense variant in PCYT2 who had axonal motor and sensory polyneuropathy in addition to a mild form of complex hereditary spastic paraplegia.

Methods

Clinical Investigations

The index patient was referred to the neurology department because of complex spastic paraplegia syndrome. Physical and neurologic examination and motor and sensory nerve conduction studies were performed. For neuropsychological assessment, we used the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status Update, which includes 12 tests across 5 domains of cognition, including immediate memory, visuospatial/constitutional, language, attention, and delayed memory.7

Genetic Analyses

Exome sequencing (ES) was performed on genomic DNA of the index patient using the Illumina Nextera Rapid Capture Expanded Exome Kit for exome enrichment and sequenced on the Illumina NextSeq 550 sequencer and the data analyzed as previously described.8 Briefly, ES data were analyzed in accordance with Genome Analysis Toolkit best practice guidelines, using the bwa 0.7.2 algorithm for the alignment of short sequencing reads and Genome Analysis Toolkit 3.5 toolkit for the detection of short sequence variation. The variants were annotated and their impact predicted using snpEff v4.3 software. Precomputed predictions of pathogenicity were obtained from the dbNSFP v2.0 database. A variety of predictors were used to predict the anticipated effect of the identified variants, including classical predictors (SIFT, PolyPhen2, and MutationTaster) and meta-predictors (MetaSVM, CADD, and REVEL). Sanger sequencing was performed to confirm the PCYT2 variant in the index patient and his affected brother and to test the carrier status in the parents.

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

Genetic studies were performed in a diagnostic context after written informed consent. Written informed consent including consent to publish photographs was obtained.

Data Availability

Anonymized data not published within this article will be made available by request from any qualified investigator.

Results

Clinical Findings

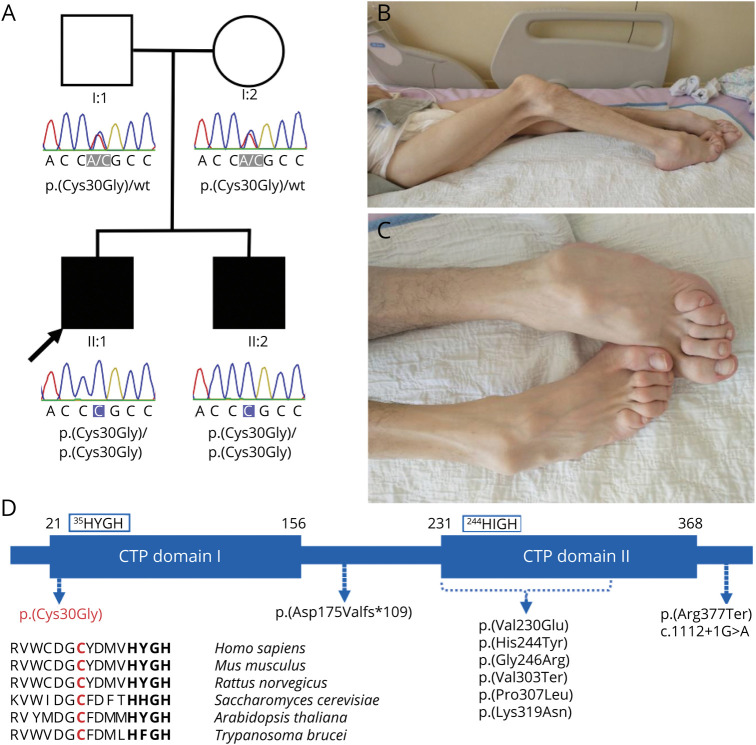

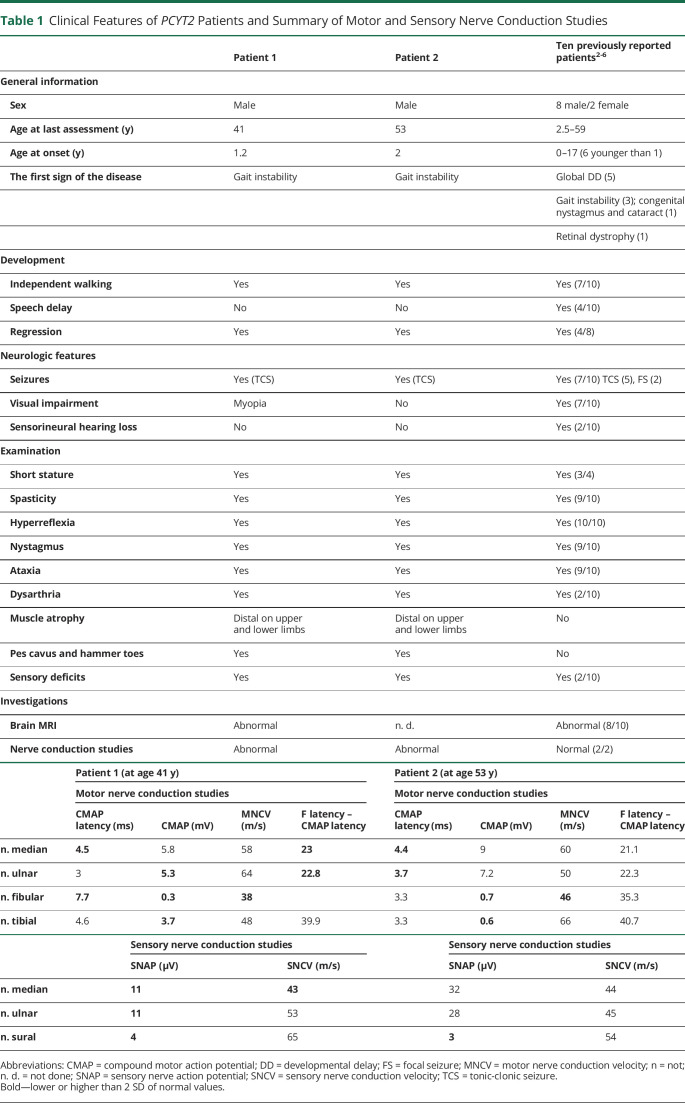

The patients are the only children of healthy, nonconsanguineous parents. There is no family history of neurologic disease. Patient 1 (II:1) is a 41-year-old man (Figure 1A). He first presented with balance problems at age 14 months when he started walking. At 19 months, his gait was unsteady and wide based, and he was diagnosed with spastic paraparesis. At age 12 years, he was diagnosed with epilepsy. His seizures were mostly tonic-clonic and well controlled with carbamazepine. In his teens, he was diagnosed with myopia. He attended mainstream school, finished secondary school, and got a job. At age 25 years, he was retired due to gait instability and inability to walk. He had dysarthria and urinary urge incontinence. At the initial examination at our clinic, at age 25 years, he was dysarthric and had horizontal nystagmus, marked intention tremor, spasticity in the upper and lower limbs, and polykinetic patellar and Achilles reflexes. In addition, he showed signs of neuropathy on lower limbs. He had muscle atrophy and weakness distal to the knees (feet dorsiflexion 3/5; plantar flexion 4/5), high-arched feet, and hammertoes, and he reported poor vibration and position perception in the distal parts of the lower limbs. By age 41 years, his condition deteriorated significantly. He was completely wheelchair dependent and cachectic and had cognitive decline with psychosis. He complained of chronic generalized pain, which was unresponsive to pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatment. The pain worsened after some analgesics, such as piritramide, and after food intake, causing him to refuse it. On examination, he was 150 cm tall (−4.1 SD), weighed 38 kg (body mass index 16.89 kg/m2), and had a head circumference of 54.5 cm (−0.7 SD). He had pendular nystagmus in all directions. In the upper limbs, the interosseous muscles were bilaterally hypotrophic and weak, muscle tone was increased, and myotatic reflexes were brisk. In the lower limbs, hip and knee flexion contractures (Figure 1B-C) and minimal movement of the toes were noted in addition to the abnormalities already reported. He wore glasses for myopia but had no additional vision problems. Nerve conduction studies showed evidence of axonal motor and sensory polyneuropathy (Table). Neuropsychological assessment revealed cognitive deficits in the domain of verbal memory, executive functions, and construction skills. The patient's global score was in the impaired range. His construction skills, semantic fluency, and delayed recall of verbal information were impaired, and perseveration errors were noted. List learning was in the lower average range, whereas story memory was borderline impaired. Visuospatial abilities, attention span, and delayed memory were below average, whereas language ability was in the average range. A brain MRI scan showed subtle, nonspecific T2 hyperintense, punctiform, frontoparietal white matter lesions and mild parietal and cerebellar brain atrophy. In the last 2 years, the number of generalized tonic-clonic seizures increased despite treatment with topiramate and lacosamide. His EEG was abnormal with short periods of theta between alpha background activity and with high-amplitude spike wave paroxysms, sometimes with frequencies of 4–5 Hz and paroxysms of polyspikes, frontally or generalized.

Figure. Genetic and Clinical Findings of the Investigated Individuals.

(A) Family tree and electropherograms of the identified PCYT2 variants. (B and C) Clinical photographs of patient 1 at age 41 years. Muscle wasting and hip and knee flexion contractures (B). High-arched feet and hammertoes (C). (D) Schematic representation of the protein isoform PCYT2α and location of variants. PCYT2 protein is predicted to have 2 cytidylyltransferase (CTP) catalytic domains. The homozygous missense variant (in red) identified in this study is located in the first CTP domain. Amino acid sequence alignments across multiple species reveal the well-conserved nature of the affected amino acid residue. All previously reported missense variants (in black) are located in the second CTP domain.

Table 1.

Clinical Features of PCYT2 Patients and Summary of Motor and Sensory Nerve Conduction Studies

Patient 2 (II:2) is a 53-year-old man, an older brother of patient 1, with milder clinical presentation. He presented with gait instability at age 2 years and began using crutches at age 14 years. At age 15 years, he had his first generalized tonic-clonic seizure. The seizures were well controlled with methylphenobarbital. His condition slowly deteriorated and by age 39 years, he was wheelchair dependent. He did not complain of vision problems. At age 53 years, he had a short stature (150 cm; −4.1 SD) and weighed 50 kg, and his head circumference was 57 cm (+0.7 SD). Neurologic examination showed dysarthria, mild saccadic eye movements, and nystagmus. Spasticity, distal muscle atrophy, and weakness were noted in the upper and lower limbs. Patellar reflexes were brisk, and Achilles reflexes were weak. The feet were high arched, and hammertoes were present. He could not feel vibration even on the crista iliaca; otherwise, sensory impairment was noted distal to the forearms and knees. He could not perform active movements with the lower limbs. Signs of cerebellar dysfunction (intension tremor, dysmetria, dysdiadochokinesia, and mild truncal ataxia) were present. He denied problems with urine retention. Cognitive impairment was similar as in patient 1, although of milder degree. His EMG was also consistent with axonal motor and sensory neuropathy (Table).

Genetic Analyses

Analysis of ES data identified a novel homozygous missense variant in PCYT2 (NM_001184917.2):c.88T>G p.(Cys30Gly) (Figure 1A). No significant homozygosity blocks were identified in the ES data, and we did not detect pathogenic variants in other polyneuropathy-related genes in the exome. Sanger sequencing confirmed the homozygous state of the same PCYT2 variant in the index patient and his affected brother. Both unaffected parents were found to be heterozygous carriers of the variant (Figure 1A). The identified variant was absent in databases (gnomAD and our internal database). The nucleotide and amino acid position are well conserved (Figure 1D), and theoretical predictors of pathogenicity consistently predicted a deleterious effect on protein function for this amino acid substitution. MutationTaster, PolyPhen2, SIFT, and MetaSVM anticipated a likely or probably damaging effect, and CADD and REVEL reported high pathogenicity scores of 27.3 and 0.93, respectively. In addition, the variant substitutes a cysteine residue that can form disulfide bonds and thus may be important for maintaining protein structure. The substitution is located in a highly conserved tyrosine kinase site (RVWCDGCY; 24–31 amino acids) 5 residues N-terminal to the HYGH catalytic motif (35–38 amino acids) in the first cytidylyltransferase (CTP) catalytic domain (Figure 1D).9

Discussion

Recently, biallelic pathogenic variants in PCYT2 have been reported in 10 members of 9 independent families.2-6 Two patients, a 32-year-old and a 59-year-old man, had a pure form of spastic paraparesis4,6; all the others presented with a complex spastic paraplegia syndrome. The individuals reported here share several phenotypic features, including short stature, spastic tetraparesis, cerebellar ataxia, epilepsy, and cognitive decline (Table). In addition, they showed progressive axonal motor and sensory polyneuropathy, evident in the third decade of life, a feature not previously observed in PCYT2-related disorders. Of 5 previously reported adult patients (age range of 20–59 years),2-6 nerve conduction studies were performed in 2 of them and reported as normal.3,4 Clinically, one of them had hypopallesthesia of the ankles,4 and the other had loss of vibration sense in the lower limbs and mild loss of proprioception in the feet.3

A wide phenotypic spectrum has been reported in patients with PCYT2-related disorders with varying time of onset, from birth to the second decade of life, different initial presenting symptoms, and varying severity, ranging from normal development to severe developmental delay and intellectual disability. The phenotypic variability is partly associated with the classical phenotypic variability in inborn errors of metabolism but could also be due to the type and location of the PCYT2 variant.

Ten variants in PCYT2 have been associated with PCYT2-related disorders, and all were located in the second CTP catalytic domain.2-6 Six of these were missense (Figure 1D). The variant detected in this study is located in the first CTP catalytic domain. No pathogenic variant has yet been described in this domain, but there are several lines of reasoning supporting its importance: (1) both CTP domains are important for enzyme activity,10 (2) the first CTP domain is thought to contribute mainly to the catalytic reaction of ET,11 and (3) the first CTP domain is part of all 3 known isoforms, whereas the second CTP domain, the hotspot of previously reported variants, is present in 2 of them.10

In summary, we presented a family with biallelic variants in PCYT2 and showed that not only missense variants in the second CPT domain but also variants in the first CPT domain lead to the PCYT2-related disorders. In addition, the patients exhibited axonal motor and sensory polyneuropathy, which represents a new phenotypic entity of PCYT2-related disorders and expands the spectrum of the disease. Although polyneuropathy has not been previously reported in patients with PCYT2-related disorder, it has been associated with pathogenic variants in genes involved in phosphatidylethanolamine biosynthesis such as PNPLA6.1,12 Further reports and studies are needed to clarify whether polyneuropathy is a low penetrant sign in PCYT2-related disorders or is related to a specific location of variants in PCYT2.

Glossary

- CTP

cytidylyltransferase

- ES

exome sequencing

- ET

CTP:phosphoethanolamine cytidylyltransferase

Appendix. Authors

Contributor Information

Lea Leonardis, Email: lea.leonardis@kclj.si.

Marusa Skrjanec Pusenjak, Email: marusa.skrjanec@kclj.si.

Ales Maver, Email: ales.maver@kclj.si.

Helena Jaklic, Email: helena.jaklic@kclj.si.

Ana Ozura Brecko, Email: ana.ozura@kclj.si.

Blaz Koritnik, Email: blaz.koritnik@kclj.si.

Borut Peterlin, Email: borut.peterlin@guest.arnes.si.

Study Funding

Slovenian Research Agency (ARRS), grant number J3-9280.

Disclosure

The authors report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org/NG for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Rickman OJ, Baple EL, Crosby AH. Lipid metabolic pathways converge in motor neuron degenerative diseases. Brain. 2020;143(4):1073-1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vaz FM, McDermott JH, Alders M, et al. Mutations in PCYT2 disrupt etherlipid biosynthesis and cause a complex hereditary spastic paraplegia. Brain. 2019;142(11):3382-3397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Winter J, Beijer D, De Ridder W, et al. PCYT2 mutations disrupting etherlipid biosynthesis: phenotypes converging on the CDP-ethanolamine pathway. Brain. 2021;144(2):e17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vélez-Santamaría V, Verdura E, Macmurdo C, et al. Expanding the clinical and genetic spectrum of PCYT2-related disorders. Brain. 2020;143:e76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaiyrzhanov R, Wortmann S, Reid T, et al. Defective phosphatidylethanolamine biosynthesis leads to a broad ataxia-spasticity spectrum [published correction appears in Brain. 2021. Jun 22;144(5):e52]. Brain. 2021;144(3):e30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wei Q, Luo WJ, Yu H, et al. A novel PCYT2 mutation identified in a Chinese consanguineous family with hereditary spastic paraplegia. J Genet Genomics. 2021;48(8):751-754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Randolph C, Tierney MC, Mohr E, Chase TN. The repeatable battery for the assessment of neuropsychological status (RBANS): preliminary clinical validity. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1998;20(3):310-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bergant G, Maver A, Lovrecic L, et al. Comprehensive use of extended exome analysis improves diagnostic yield in rare disease: a retrospective survey in 1,059 cases. Genet Med. 2018;20(3):303-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bakovic M, Fullerton MD, Michel V. Metabolic and molecular aspects of ethanolamine phospholipid biosynthesis: the role of CTP:phosphoethanolamine cytidylyltransferase (Pcyt2). Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;85(3):283-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pavlovic Z, Singh RK, Bakovic M. A novel murine CTP:phosphoethanolamine cytidylyltransferase splice variant is a post-translational repressor and an indicator that both cytidylyltransferase domains are required for activity. Gene. 2014;543:58-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tian S, Ohtsuka J, Wang S, et al. Human CTP:phosphoethanolamine cytidylyltransferase: enzymatic properties and unequal catalytic roles of CTP-binding motifs in two cytidylyltransferase domains. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;449(1):26-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Synofzik M, Gonzalez MA, Lourenco CM, et al. PNPLA6 mutations cause Boucher-Neuhauser and Gordon Holmes syndromes as part of a broad neurodegenerative spectrum. Brain. 2014;137:69-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized data not published within this article will be made available by request from any qualified investigator.