Abstract

Background and Objectives

Recovery from severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection appears exponential, leaving a tail of patients reporting various long COVID symptoms including unexplained fatigue/exertional intolerance and dysautonomic and sensory concerns. Indirect evidence links long COVID to incident polyneuropathy affecting the small-fiber (sensory/autonomic) axons.

Methods

We analyzed cross-sectional and longitudinal data from patients with World Health Organization (WHO)-defined long COVID without prior neuropathy history or risks who were referred for peripheral neuropathy evaluations. We captured standardized symptoms, examinations, objective neurodiagnostic test results, and outcomes, tracking participants for 1.4 years on average.

Results

Among 17 patients (mean age 43.3 years, 69% female, 94% Caucasian, and 19% Latino), 59% had ≥1 test interpretation confirming neuropathy. These included 63% (10/16) of skin biopsies, 17% (2/12) of electrodiagnostic tests and 50% (4/8) of autonomic function tests. One patient was diagnosed with critical illness axonal neuropathy and another with multifocal demyelinating neuropathy 3 weeks after mild COVID, and ≥10 received small-fiber neuropathy diagnoses. Longitudinal improvement averaged 52%, although none reported complete resolution. For treatment, 65% (11/17) received immunotherapies (corticosteroids and/or IV immunoglobulins).

Discussion

Among evaluated patients with long COVID, prolonged, often disabling, small-fiber neuropathy after mild SARS-CoV-2 was most common, beginning within 1 month of COVID-19 onset. Various evidence suggested infection-triggered immune dysregulation as a common mechanism.

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) can cause long-term disability (long COVID) with new neurologic manifestations after even mild infections.1 Reports of peripheral neuropathy include Guillain-Barré syndrome, mononeuritis multiplex, brachial plexitis, cranial neuropathies, and orthostatic intolerance, although some studies included patients with potentially contributory conditions. Various long COVID symptoms overlap with those of small-fiber polyneuropathy (SFN).2,3 Hence, we prospectively analyzed a cross-section of patients with long COVID evaluated for incident neuropathy.

Methods

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

This retrospective analysis was approved by the hospitals' ethical review committee (1999P009042). Although participant consent was not required, all 17 provided verbal consent and 16 signed agreements for participation and publication of anonymized results.

Study Design

Inclusion required no known prior neuropathy or risks plus confirmation of SARS-CoV-2 infection according to guidelines of the World Health Organization (WHO). COVID severity classification followed WHO guidelines. Inclusion required meeting the WHO definition of long COVID (onset of symptoms within 90 days of the first day of COVID symptoms that last for >2 months).1 Participants were enrolled upon COVID confirmation and neuromuscular referral before record review or most testing and treatment. Participants documented neuropathy symptoms via online REDCap surveys, and their neurologists documented standardized in-person and occasional telehealth neuropathy examinations.4,5 Because most participants had received symptom-relieving medications at varying doses, we analyzed only potentially preventive treatments, all of which were immunotherapies. Parametric analyses were used with variability represented by standard errors.

Data Availability

Any anonymized data not published within the article will be shared by request from any qualified investigator.

Results

Among 17 patients with SARS-CoV-2 onset between February 21, 2020, and January 19, 2021, treated in 10 states/territories (Table 1), 16 had mild COVID. The one (#9) with severe COVID (1 month stay in intensive care with ventilatory support) had electrodiagnostically confirmed sensorimotor polyneuropathy ascribed to critical care illness in addition to SFN. Medical histories and comprehensive blood screening (not shown) identified none with conventional neuropathy risks nor evidence of systemic dysimmunity. Imaging of the brain or spine, if performed, was unrevealing.

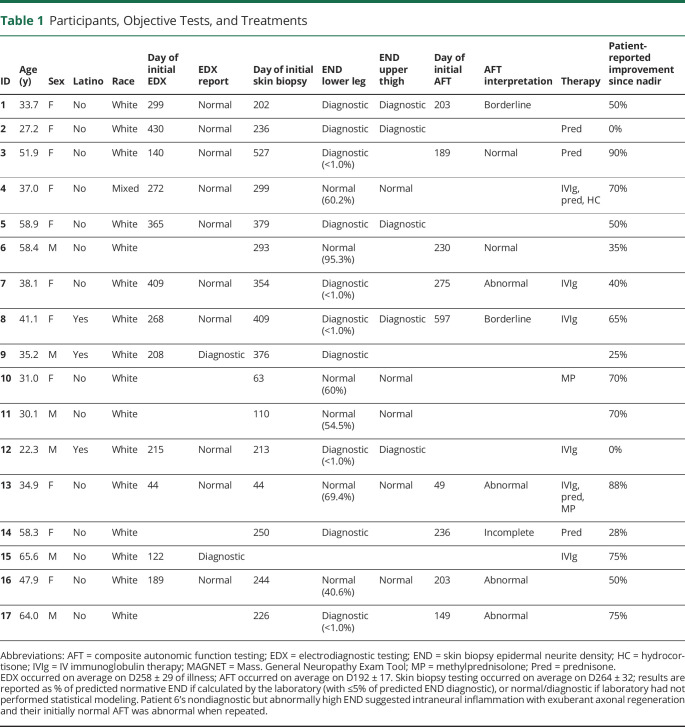

Table 1.

Participants, Objective Tests, and Treatments

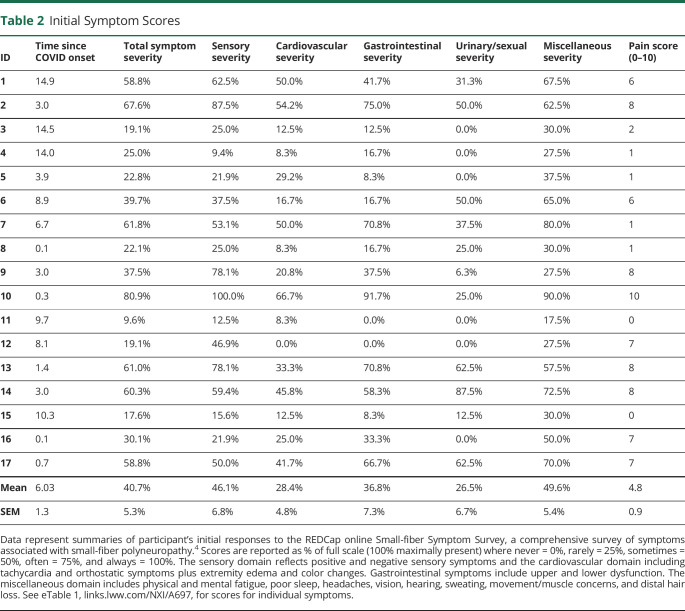

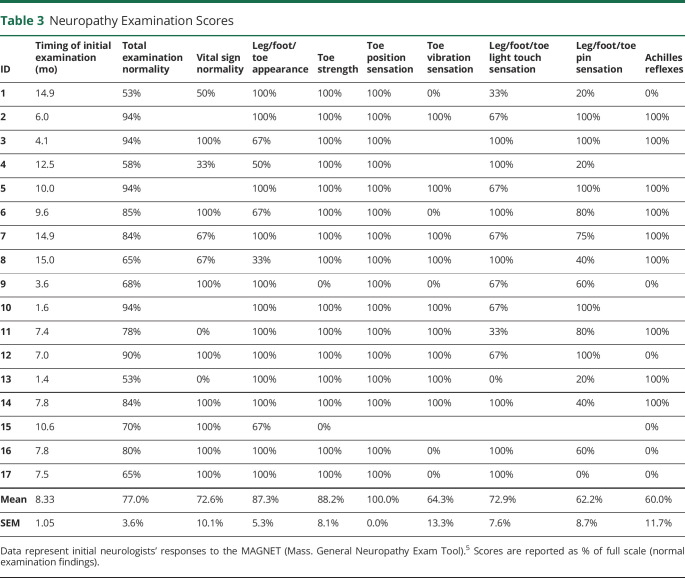

Participants' ages averaged 43.3 ± 3.3 years on COVID D1, and 68.8% were female; 18.8% were Latino, and 94.1% were Caucasian. Diagnostic tests for neuropathy (Table 1) revealed that 16.7% electrodiagnostic studies were abnormal, whereas 62.5% (10/16) of lower leg skin biopsies pathologically confirmed SFN, as corroborated by 50% of upper thigh biopsies and autonomic function tests.2 Initial SFN symptom scores (Table 2) were abnormal—reduced to 40.7% of ideal on average—with pain scores averaging 4.8/10. Initial neuromuscular examinations (Table 3) averaged 77.0% of ideal, with reduced/abnormal distal pin and vibration sensations and absent Achilles reflexes most prevalent.4,5 Participants 9 and 15 had distal muscle weakness and atrophy. Some patients were initially evaluated early in the course and others later, and investigations continued for months. Sixteen participants with 2020 onset had >1 year follow up, with the latest onset on 1/19/21. See Figure 1 (case 15) and eFigure 1, links.lww.com/NXI/A697, (case 13) for longitudinal details.

Table 2.

Initial Symptom Scores

Table 3.

Neuropathy Examination Scores

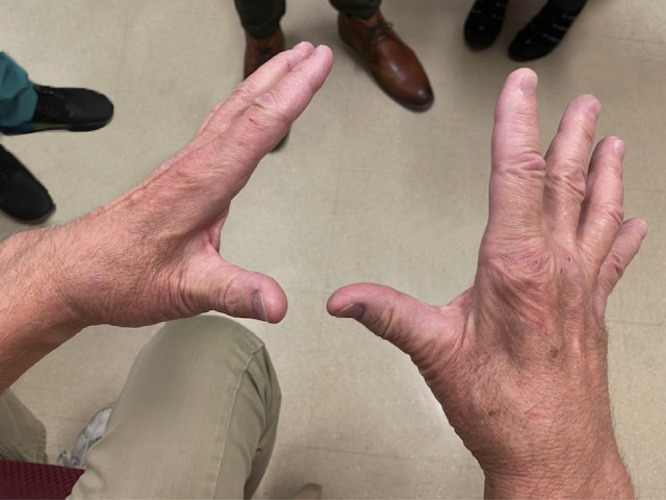

Figure 1. Case 15: Prolonged COVID-Incident Multifocal Motor Neuropathy.

CMAP = compound motor action potential; D = day; EDX = electrodiagnostic testing; IVIg = IV immunoglobulin therapy; MMN = multifocal motor neuropathy; SNAP = sensory nerve action potential. Three weeks after 12/04/1920 onset of mild COVID-19, this previously healthy 65-year-old developed progressive R > L hand weakness and atrophy. Three months later, he could not hold eating utensils or a pen and noted hand “limpness” tingling and pain, and finger cramps without lower limb symptoms. Neurosurgical referral prompted cervical MRI showing unrelated degenerative changes. A local neurologist's EDX suggesting MMN or lower motor neuron disease prompted our neuromuscular evaluation on post-COVID D67. This revealed weakness in the distal ulnar and median nerve distributions, 4/5 finger abduction strength, and R > L interosseus and thenar eminence atrophy. He could not make a fist or hold utensils; sensory self-examination was normal. EDX on D122 documented demyelinating neuropathy with conduction blocks in both ulnar nerves at the forearms and across the elbows and prolonged latencies and reduced conduction in both median nerves. F waves were prolonged in the upper and lower limbs, and the right peroneal CMAP was low amplitude. SNAP velocities were normal, with slightly diminished amplitude in the median, ulnar, and sural nerves. Serum immunoglobulins and immunofixation were normal, and GM1 antibodies were absent. He met the diagnostic criteria for MMN and began standard treatment, IVIg 2 g/kg/4 weeks, on D146. A few weeks later, he noticed improved hand dexterity with ability to fully open hands and use utensils and decreased hand cramps, with 90% improvement after the 3rd cycle. Then, expiration of IVIg orders caused regression. After 2 missed cycles, D292 evaluation documented R > L increasing difficulty opening his hands and return of hand and forearm tingling. He self-reported hair loss on legs, muscle difficulties, skin color changes, tingling, itching, and needing to move legs for comfort (eFigure 1, links.lww.com/NXI/A697). Same-dose IVIg was restarted, and after 2 cycles with improvement, clinic return on D341 documented 80% improved weakness, hand opening, finger dexterity, and hand cramps. He had bilateral 4/5 finger abduction strength, and this image documented significant remaining R > L interossei muscle atrophy. IVIg was continued, and he was referred for interosseus exercises.

Treatments comprised corticosteroids in 35.3% (6/17) and IV immunoglobulins (IVIg) in 35.3% (6/17). Five were initially dosed at 2.0 g/kg/4 weeks and 1 at 1.6 g/kg/4 weeks. The 5 patients who received repeated IVIg, and their neurologists, reported benefit (e.g., Figure 1, Table 1). eFigure 1 reports patient 13's graphed symptom and examination scores before and during IVIg. Patients' impressions of recovery varied (averaging 51.8 ± 6.7%), reflecting varying illness severity, treatment status, and assessment timing.

Discussion

Neuromuscular evaluations proved useful in most of these patients with long COVID. However some symptoms, exam changes and test results may have been false-negative, given that assessments were not often optimally timed (e.g., #6) and many patients reported care delays. This reported case of multifocal motor neuropathy (Figure 1) increases the spectrum of COVID-associated dysimmune neuropathies. Critical illness neuropathy—reported in approximately 10% of intubated patients with COVID—is attributed to various prolonged insults including intense inflammation and nerve compressions.6 Inherent study limitations include bias toward referrals for sensory neuropathy and underpowering. The initial evaluations reported occurred at varying times during the illness and treatment, whereas longitudinal assessments at standardized intervals are ideal for diagnostic and treatment decisions. Timing also complicates analysis of blood testing for immune markers (not shown). We screened patients with newly diagnosed neuropathy for all common established causes of distal sensory neuropathy, including routinely measuring ANA, ESR, IgG anti–SS-A/SS-B antibodies, and complement components C3 and C4, the most productive markers of dysimmunity in initially idiopathic SFN.7 We did not detect evidence of Sjögren syndrome, and other inflammatory markers were only occasionally elevated. Interpretation is complex as early elevations could be nonspecifically associated with acute COVID, and many months later, inflammation and markers might have subsided leaving residual axonopathy as the proximate cause of current symptoms. Regeneration can take up to 2 years or be incomplete.

These results identify small-fiber neuropathy as most prevalent in this small group of patients with long COVID, also known as post-acute sequelae of SARS CoV-2 infection.2 In SFN, the small-diameter unmyelinated and/or thinly myelinated sensory and autonomic fibers are predominantly affected, although most patients with severe or advanced polyneuropathy, e.g., case 9, develop large- and small-fiber damage. The small fibers are disproportionately vulnerable, with their lack of myelin exposing them to environmental stressors including immunity, while inability to use saltatory conduction increases metabolic demand, and cytoplasmic paucity limits axonal regeneration. However, small-fiber axons grow throughout life to reinnervate continuously dividing tissues such as the skin and to help repair injuries. If toxic conditions improve, axon elongation and sprouting accelerate to increase the probability of reinnervating enough target cells to resolve symptoms.

Here, most patients treated with sustained IVIg, the primary treatment for inflammatory neuropathy, with preliminary evidence of effectiveness for dysimmune SFN,8 perceived improvement (e.g., Figure 1, eFigure 1, links.lww.com/NXI/A697). Some treated only with corticosteroids did as well; participant 3 reported that prednisone helped her toward 90% improvement and was discontinued only because of adverse effects. Others improved substantially without immunotherapy (e.g., case 17), documenting spontaneous recovery and need to individualize treatment decisions.

The hypothesis that some long COVID symptoms reflect underlying small-fiber pathology is supported by research observation of small-fiber loss applying in vivo corneal confocal microscopy to patients with long COVID.9 As with other post-COVID neurologic illnesses, susceptibility to inflammatory mediators appears essential. Autopsy study of post-COVID patients identified neuritis with perivascular macrophage infiltrates but no viral antigens, implicating inflammatory immune responses rather than direct infection. In addition, 1/4th of human DRG neurons express mRNA for SARS-CoV-2–associated receptors and deploy ACE2 protein. Thus, virus or spike protein fragments may attach to them, promoting formation of antibodies that can also target adjacent neural epitopes. Here, the slightly delayed onsets, prolonged postinfectious courses, and apparent responses to continued immunotherapy suggested dysimmune mechanisms.

This report strengthens evidence linking several idiopathic multisymptom conditions—including SFN and fibromyalgia—with dysimmunity, sometimes incident to infections or vaccinations.2 As with COVID-incident Guillain-Barré syndrome and all referral-based case series, the current cases neither confirm causality nor the clinical significance or magnitude of any association. However, identifying small-fiber neuropathy and multifocal motor neuropathy in 1 small sample of patients with WHO-defined long COVID provides rationale and preliminary data for larger investigations and may influence interim medical evaluations of similar patients.

Acknowledgment

The authors gratefully acknowledge patient contributions including details from medical personnel. They also thank many colleagues who referred patients, facilitated studies, or contributed data including Heather M. Downs, BS, Lisa Paul, NP, Shibani Mukerji, MD, PhD, Khosro Farhad, MD, Pedro Steven Buarque de Macedo, MD, Yancy Seamans, FNP, Joseph Tornabene, MD, Matthew P. Wicklund, MD, Jennifer Curtin, MD, Yair Mina, MD, Sara Dehbashi, MD, and Madeleine C. Klein, BS.

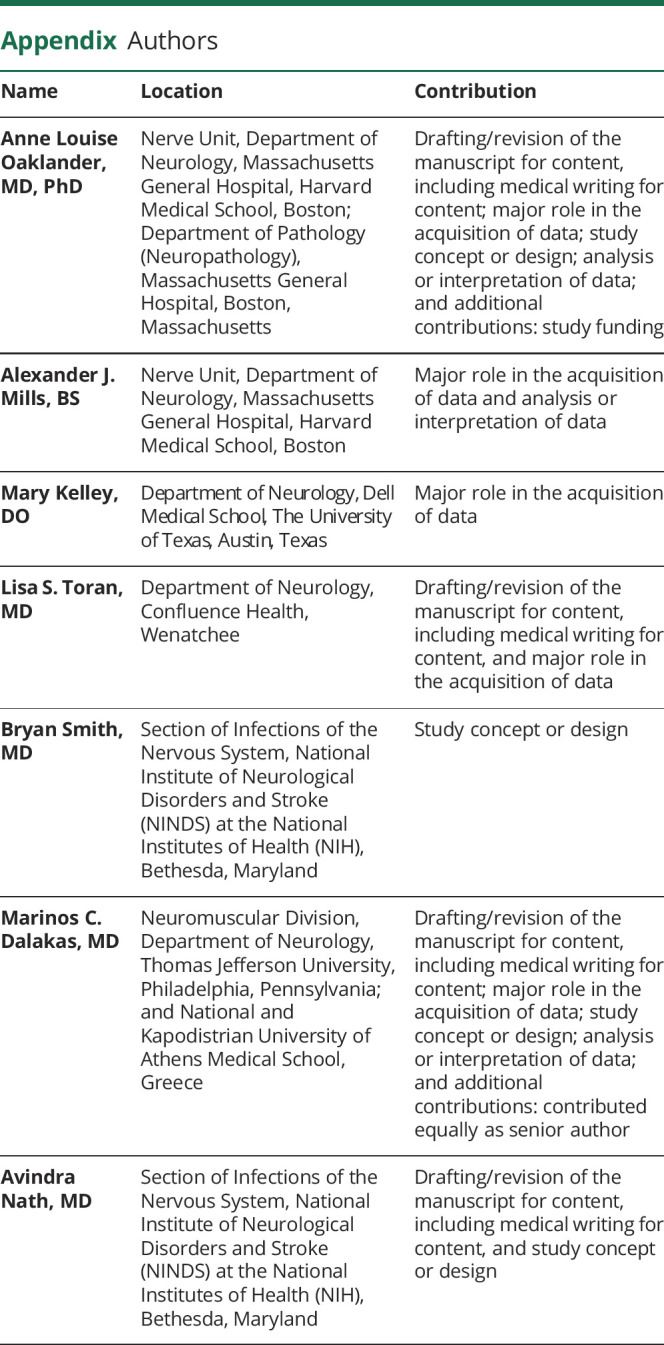

Appendix. Authors

Contributor Information

Alexander J. Mills, Email: amills8@mgh.harvard.edu.

Mary Kelley, Email: mary.kelley@ascension.org.

Lisa S. Toran, Email: ltoranca@gmail.com.

Bryan Smith, Email: bryan.smith2@nih.gov.

Marinos C. Dalakas, Email: marinos.dalakas@jefferson.edu.

Avindra Nath, Email: natha@ninds.nih.gov.

Study Funding

Supported in part by the National Institutes of Health; R01NS093653 (ALO). Division of Intramural Research, NINDS (AN) and the Department of Neurology of Thomas Jefferson University (MCD).

Disclosure

The authors report no disclosures. Go to Neurology.org/NN for full disclosures.

References

- 1.World Health Organization A Clinical Case Definition of Post COVID-19 Condition by a Delphi Consensus. 2021. Accessed October 1, 2021. WHO/2019-nCoV/Post_COVID-19_condition/Clinical_case_definition/2021.1. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oaklander AL, Nolano M. Scientific advances in and clinical approaches to small-fiber polyneuropathy: a review. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(10):1240-1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis HE, Assaf GS, McCorkell L, et al. Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;38:101019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Treister R, Lodahl M, Lang M, Tworoger SS, Sawilowsky S, Oaklander AL. Initial development and validation of a patient-reported symptom survey for small-fiber polyneuropathy. J Pain. 2017;18(5):556-563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zirpoli G, Downs S, Farhad K, Oaklander AL. Initial validation of the Mass General neuropathy exam tool (MAGNET) for diagnosing small-fiber polyneuropathy. Ann Neurol. 2018. Proccedings of the 2018 meeting of the American Neurological Association. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bocci T, Campiglio L, Zardoni M, et al. Critical illness neuropathy in severe COVID-19: a case series. Neurol Sci. 2021;42(12):4893-4898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lang M, Treister R, Oaklander AL. Diagnostic value of blood tests for occult causes of initially idiopathic small-fiber polyneuropathy. J Neurol. 2016;263(12):2515-2527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu X, Treister R, Lang M, Oaklander AL. IVIg for apparently autoimmune small-fiber polyneuropathy: first analysis of efficacy and safety. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2018;11:1756285617744484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bitirgen G, Korkmaz C, Zamani A, et al. Corneal confocal microscopy identifies corneal nerve fibre loss and increased dendritic cells in patients with long COVID. Br J Ophthalmol. 2021. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2021-319450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Any anonymized data not published within the article will be shared by request from any qualified investigator.