Abstract

Coincidence detection and cortical rhythmicity are both greatly influenced by neurons’ propensity to fire bursts of action potentials. In the neocortex, repetitive burst firing can also initiate abnormal neocortical rhythmicity (including epilepsy). Bursts are generated by inward currents that underlie a fast afterdepolarization (fADP) but less is known about outward currents that regulate bursting. We tested whether Kv2 channels regulate the fADP and burst firing in labeled layer 5 PNs from motor cortex of the Thy1-h mouse. Kv2 block with guangxitoxin-1E (GTx) converted single spike responses evoked by dendritic stimulation into multispike bursts riding on an enhanced fADP. Immunohistochemistry revealed that Thy1-h PNs expressed Kv2.1 (not Kv2.2) channels perisomatically (not in the dendrites). In somatic macropatches, GTx-sensitive current was the largest component of outward current with biophysical properties well-suited for regulating bursting. GTx drove ~40% of Thy1 PNs stimulated with noisy somatic current steps to repetitive burst firing and shifted the maximal frequency-dependent gain. A network model showed that reduction of Kv2-like conductance in a small subset of neurons resulted in repetitive bursting and entrainment of the circuit to seizure-like rhythmic activity. Kv2 channels play a dominant role in regulating onset bursts and preventing repetitive bursting in Thy1 PNs.

Keywords: afterdepolarization, cortical rhythm, epilepsy, guangxitoxin, Thy1-h neuron

Introduction

Numerous studies suggest that there are two broad classes of pyramidal neurons (PNs) in neocortex, separated by their projection targets into those that project only within the telencephalon (intratelencephalic projecting: IT-type) and those that project beyond the telencephalon (pyramidal tract- or PT-type: Reiner et al. 2003, 2010; Anderson et al. 2010; Suter et al. 2013). We favor the more descriptive and inclusive term extrapyramidal (ET-type) for the latter, since not all areas of neocortex project within the pyramidal tract (Baker et al. 2018). Layer 2/3 PNs are IT-type. Layer 5 PNs include both IT- and ET-type (Reiner et al. 2003, 2010; Anderson et al. 2010; Dembrow et al. 2010; Groh et al. 2010; Suter et al. 2013; Guan et al. 2015). Besides differences in projections, numerous studies have shown that IT- versus ET-type PNs differ in morphology (Chagnac-Amitai et al. 1990; Mason and Larkman 1990; Agmon and Connors 1992; Tseng and Prince 1993), sublaminar localization (Mason and Larkman 1990; Reiner et al. 2003; Suter et al. 2013), synaptic inputs (de Kock et al. 2007; Brown and Hestrin 2009; Anderson et al. 2010; Suter et al. 2013), and physiological properties (Connors et al. 1982; McCormick et al. 1985; Mason and Larkman 1990; Hattox and Nelson 2007; Dembrow et al. 2010; Groh et al. 2010; Suter et al. 2013; Guan et al. 2015). These PN subtypes have distinct functions: For example, anesthetics elicit burst firing in ET but not IT PNs (Christophe et al. 2005) and IT but not ET PNs mediate responses to antidepressants (Schmidt et al. 2012).

Early work from the Prince lab (Connors et al. 1982; McCormick et al. 1985) showed that while most neocortical PNs fired repetitively and regularly in response to a DC current injection, a subset of PNs in layers 4 and 5 responds to such stimuli with an initial burst of high-frequency action potentials (APs) riding on a slow depolarization, with a subsequent return to the regular spiking pattern. Despite differences between labs and species in the frequency of occurrence of such intrinsic burst firing neurons, depending upon recording conditions (e.g., internal anion, degree of chelation, temperature, extracellular K+ or Ca2+ concentration, amount of dendrites or axon that survives the slicing procedure, DC vs. rapidly fluctuating inputs), there is general agreement that a subset of layer 5 PNs with somas in deep layer 5 and with prominent apical dendrites that extend all the way to the pia is the most likely to show onset burst firing (Mason and Larkman 1990; Larkman and Mason 1990; Tseng and Prince 1993; Larkum et al. 1999, 2004; Williams and Stuart 1999). These PNs correspond to ET-type PNs, although under the right conditions, virtually all PNs can fire with an onset burst (e.g., Larkum et al. 2007). ET-type PNs provide the main output from cortex and they project beyond the telencephalon (Reiner et al. 2003; Anderson et al. 2010; Dembrow et al. 2010; Reiner et al. 2010). Consistent with onset bursting being most common in ET-type PNs that provide cortical output and have long horizontal projections (Telfeian and Connors 1998), this cell type is implicated in the initiation and spread of seizure activity of neocortical origin (Connors 1984; Wong et al. 1986; Chagnac-Amitai and Connors 1989; Silva et al. 1991; Telfeian and Connors 2003; Pinto et al. 2005; Traub et al. 2005).

Two main mechanisms have been proposed to underlie onset burst firing in PNs. One model suggests that bursting occurs when back propagating Na+ action potentials depolarize an apical dendritic site of Ca2+ electrogenesis, resulting in a dendritic Ca2+ AP that propagates to the soma, where it elicits a slow depolarization that summates with Na+ currents at the axonal initial segment (AIS), resulting in a burst of Na+ APs (Larkum et al. 1999, 2004; Williams and Stuart 1999; Oakley et al. 2001a, 2001b). Another model emphasizes the role of an intact axon for burst firing and proposed that the inward current underlying the burst comes from back propagation of axonal persistent Na+ current to the soma (Guatteo et al. 1996; Debanne 2011; Kole 2011). These two mechanisms are not mutually exclusive.

Less is known about what controls these inward currents to regulate burst firing. In general, the filtering by potassium (K+) channels of the transform from synaptic input to spike output shapes neuronal computation. Our previous work has identified many voltage- and Ca2+-gated K+ channels in neocortical PNs that could potentially regulate burst firing. These include Kv1, Kv2, Kv4, Kv7, SK, and sAHP currents (Guan et al. 2006, 2013, 2015; Guan, Armstrong, et al. 2007a; Guan, Lee, et al. 2007b; Higgs and Spain 2009, 2011; Guan, Higgs, et al. 2011a; Guan, Horton, et al. 2011b; Bishop et al. 2015; see also: Schwindt et al. 1988; Lorenzon and Foehring 1992; Foehring and Surmeier 1993; Pineda et al. 1998, 1999; Bekkers 2000; Korngreen and Sakmann 2000; Abel et al. 2004; Norris and Nerbonne 2010). In particular, the perisomatic localization, large amplitude, moderately fast kinetics of activation, and slow inactivation of Kv2 currents suggest that these channels might be important in regulating burst firing (Murakoshi and Trimmer 1999; Guan, Armstrong, et al. 2007a; Guan et al. 2013; Liu and Bean 2014; Bishop et al. 2015). In addition, three recent studies have reported that pharmacological block of Kv2 channels in CA3 PNs, substantia nigra neurons, or entorhinal cortex stellate neurons resulted in some form of bursting to a limited set of inputs (e.g., large phasic stimuli in CA3, small tonic stimuli in stellate neurons; Kimm et al. 2015; Hönigsperger et al. 2017; Raus Balind et al. 2019).

In order to reliably target ET neurons in layer 5 of motor cortex, we studied the function of Kv2 channels in the Thy1-h mouse line (hereafter referred to as Thy1 PNs: Feng et al. 2000), a genetically and physiologically distinct subset of ET PNs that express yellow-fluorescent protein (EYFP) in deep layer 5. Thy1 PNs are large and have extratelencephalic (ET) projecting axons. Our main finding is that the dominant function of Kv2 channels in Thy1 PNs is to regulate high-frequency bursts of action potentials. In addition, because burst firing is associated with rhythmic activity in neocortex (Rodriguez et al. 1999; Fries et al. 2001; Siegel et al. 2008; Womelsdorf et al. 2014; Sacchet et al. 2015) and mutations affecting Kv2 function are associated with (and likely cause) some forms of familial epilepsy (D’Adamo et al. 2013; Speca et al. 2014), we used our experimental results to model whether suppression of Kv2 channel activity in this subset of neurons could result in rhythmic oscillations in a local cortical circuit, which could in turn facilitate seizures.

Materials and Methods

All experiments were performed in accordance with institutional and national guidelines for animal care and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at the University of Washington and the University of Tennessee Health Science Center.

Slice Preparation

Both female and male 4–8 weeks old mice from Thy1 EYFP lines were anesthetized using either an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (130 mg/kg)/xylazine (8.8 mg/kg) mixture or after exposure to isoflurane. Some mice were then perfused through the heart with ice-cold saline containing the following (in mM): 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3, 0.5 CaCl2, 7 MgCl2, 7 dextrose, 205 sucrose, 0.4 to1.3 ascorbate, and 1 to 3 sodium pyruvate bubbled with 95% O2/5% CO2 (carbogen) to maintain the pH at 7.4 (others were not perfused). Brains were removed and a coronal blocking cut containing the motor cortex was attached to a vibrating tissue slicer (Leica, Germany or Vibroslice: Cambridge). The 300-μm-thick coronal sections were collected in ice-cold saline identical to perfusion solutions and subsequently stored in holding solution containing the following (in mM): 125 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3, 2 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, 12.5 dextrose, and 3 sodium pyruvate (bubbled with carbogen) at 35 °C for 30 min and then at room temperature.

Methods for Dissociated Cells

For details on cell dissociation procedures, solutions, and voltage protocols for isolation of the A-current, please refer to Guan, Higgs, et al. (2011a); Guan, Horton, et al. (2011b). In brief, 5–8 weeks old Thy1 mice were used. The brain was removed after decapitation under isoflurane anesthesia and cut into 300-μm-thick coronal slices in ice-cold high sucrose solution. Area of motor cortex was further dissected from slices as to 1–2 mm2 squared blocks. Four to six such cortical blocks were treated in enzyme solution (Protease IV, 0.7 mg/mL in aCSF) at 34 °C for 35 min. After three rounds of gradually size-confining trituration, the supernatant of dissociated neurons was placed in a 35-mm petri dish and observed under Nikon inverted microscope (DIAPHOT 300).

External Solutions

Current-clamp external solutions contained the following (in mM): 125 NaCl, 3 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 26 NaHCO3, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 17 dextrose, 3 sodium pyruvate (bubbled with carbogen). In all experiments using only injected current stimuli, the aCSF also contained 6,7- dinitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (DNQX, 20 μM), D-(−)-2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid (D-AP5, 20 μM), picrotoxin (100 μM), and CGP66845 (2 μM) to block synaptic input mediated by AMPA/kainate, NMDA, GABAA, and GABAB receptors, respectively (DNQX and D-AP5 were omitted in the experiments using 2p-glu stimulation). The Kv2 channel blocker Guangxytoxin-1E (GTx; Alomone Labs, Jerusalem, Israel) was bath applied at 100 nM together with 0.25% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (recirculating bath system with constant flow of ~2 mL/min). In experiments using the Kv4 channel blocker, AmmTx3 (200 nM, Smartox Biotechnology, Saint-Egrève, France) recording conditions were consistent with GTx application. Recordings were performed at 33–35 °C.

The external solution for outside-out macropatches contained the following (in mM): 125 NaCl, 3 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 26 NaHCO3, and 20 glucose (pH 7.4, 310 mOsm; bubbled with carbogen). For dissociated cell experiments, a HEPES buffered solution was used that contained (in mM): 140 sodium isethionate, 3 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 12 glucose, 10 HEPES, and 1.6 CaCl2. To isolate potassium channels in voltage clamp (slice, macropatch, and dissociated cells), external solutions contained 1 μM tetrodotoxin (TTX; Tocris) and 100–400 μM CdCl2 for blocking Na+ and Ca2+ channels, respectively. Recordings were performed at 33–35 °C, except for dissociated cells (RT).

Internal Solutions

In current-clamp configuration, recording pipettes were filled with an internal solution containing (in mM): 140 K gluconate, 14 KCl, 10 HEPES, 4 Mg adenosine 5-triphosphate (ATP), 0.3 NaGTP, 7 2 K phosphocreatine, and 4 2Na phosphocreatine (pH 7.42 with KOH) and Neurobiotin (0.1–0.2%). Alexa 594 (40 μM) and Oregon Green BAPTA-6F (100 μM) were added for two-photon imaging and uncaging experiments (see below). The liquid junction potential (8–9 mV) was uncorrected for current-clamp experiments.

For macropatch experiments, electrodes were filled with an internal solution containing (in mM): 130.5 KMeSO4, 10 KCl, 7.5 NaCl, 2 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 2 Na2ATP, 0.2 guanosine 5-triphosphate (GTP: sodium salt), and 5 mM EGTA to prevent activation of Ca2+-dependent conductances.

For dissociated cells, the internal solution consisted of (in mM): 86 KMeSO4, 54 KOH, 2 MgCl2, 40 HEPES, 2 Na2ATP, 0.2 NaGTP, 9 creatine phosphate, 0.1 leupeptin, 10 BAPTA (pH 7.2; 270 mOsm). The liquid junction potential (8 mV) was corrected for voltage-clamp experiments.

Recordings

Layer 5 PNs in the motor cortex that expressed EYFP (Thy1) were targeted for somatic recording using epifluorescence combined with IR-DIC. Recordings were performed in current-clamp configuration from whole-cell patch pipettes made from borosilicate glass (Sutter, Novato, CA, USA) with tip openings of about 1 μm and resistances of 4–6 MΩ following coating of the taper with Sylgard to reduce capacitance. Recordings were performed using an Axopatch 2B or Multiclamp 2A amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) in bridge balance mode, either with 10 kHz low-pass filtering and 20 kHz data sampling through an ITC-18 digital board (HEKA, Holliston, MA, USA) and controlled using custom protocols written in Igor Pro (Wavemetrics, OR, USA) or using PClamp 9. Reported voltages were not corrected for the measured liquid junction potential (8–9 mV). Recordings with >25 MΩ series resistance or < 0 mV spike overshoot were discarded.

Voltage-clamp recordings were performed using an Axon Multiclamp 700A amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) and PClamp 9 software digitized at 10 kHz and filtered at 4 kHz. Some voltage-clamp experiments to test for selectivity of GTx or AmmTx were performed as whole-cell recordings in the slice preparation. This preparation allowed us to record from cell types identified by EGFP/YGFP. To allow accurate biophysical measurements of outward K+ currents in dendritic neurons where space-clamp is a serious issue for whole-cell recording, we used outside-out macropatches for all of the detailed biophysics. These macropatches were obtained by forming a 1-GΩ or tighter seal and slowly withdrawing the pipette following break-in to whole-cell mode. Macropatch capacitance in this configuration was typically 2–4 pF and Rseries was 5–9 MΩ. All reported voltages were corrected by subtracting the measured liquid junction potential (8 mV). For dissociated cell recordings, electrode resistances were 1.4–2.2 M. Series resistance was compensated by 70–90%. Cells with calculated series resistance errors of >5 mV were discarded (series resistance error = series resistance after compensation (G) multiplied by peak current (pA)).

Stimulation in Current-Clamp Experiments

Glutamate Uncaging

Precise focal activation of individual dendritic spines was performed using a two-photon laser-based scanning system from Bruker Technologies (Middleton, WI). Pulsed laser light (80 MHz; Chameleon Ultra II; Coherent; Santa Clara, CA) at 810 nm was guided by galvanometer-controlled (6 mm, Cambridge) mirrors through a 40× objective on a Zeiss microscope for imaging. Reflected fluorescent light was separated using two dichroic mirrors and through green (ET525/70 m-2P; Chroma) and red (ET650/75 m-2P; Chroma) emission filters and collected using gallium arsenide phosphide (GaAsP) detectors. The 2048 × 2048 pixel images were collected of the 300 × 300 μm (1×) or 75 × 75 μm (4×) field of view using PrairieView (v4.3.2.6) software. To photolyze caged glutamate, a second two-photon laser (Chameleon Ultra II; Coherent) at 720 nm was used and guided by a separate set of galvanometer-controlled (3 mm, Cambridge) mirrors into the light path. The intensity of each laser beam reaching the sample was independently attenuated using an electro-optical modulator (Pockels cell). In addition, the uncaging pathway passed through a homemade passive 8× pulse splitter to reduce photodamage (Ji et al. 2008). 4-Methoxy-7-nitroindolinyl-caged-L-glutamate (MNI-glu; Tocris, Bio-Techne, Minneapolis, MN) was bath applied at 4 mM and recirculated using an oxygenated reservoir (5 mL). PrarieView and TriggerSync (v2.0.5) software was utilized in conjunction with custom-written acquisition code in MATLAB (R2012b; Mathworks, Natick, MA) to 1) control laser intensity, 2) control the galvanometer-controlled beam location within the field of view, and 3) to collect imaging, stimulation parameters and electrophysiological data. Spines that were within an optical depth (z-section) were targeted for focal caged glutamate photolysis adjacent to the spine head using 0.2 ms exposure times. Spines on a specific dendrite segment were stimulated in random order with a 0.3 ms interspine-stimulus interval.

Noisy Current Stimulation

We determined the effect of Kv2 channel blockade on neuron resonant firing properties during noisy somatic current injection. Noise stimulations consisted of a noisy current and a DC offset that was adjusted after each 10-s trial to maintain a targeted firing rate. The noisy portion of the current was set to have a standard deviation (SD) to give a 2 mV SD membrane potential (Vm) fluctuation when the neuron was held at a mean Vm of −70 mV (i.e., close to resting membrane potential: RMP) in control solution. The noise was created using an Ornstein–Uhlenbeck process as in Higgs and Spain (2011), and was filtered with a 5-ms time constant. For frequency-current curves, this noisy portion of current was added to DC steps. For gain–frequency analysis, the mean firing rate was then set to 20 Hz by adding DC current to the noise. The mean rate was maintained at 20 Hz after bath application of GTx by adjusting the DC current while maintaining the SD of the noise at its original setting. We collected 2000 spikes for analysis, by 10 repeats of 10-second trials of 20-Hz firing. The noise added to the traces was varied between trials, but frozen between control and GTx experiments.

Immunocytochemistry and Histology

Thy1 mice (n = 4, P26–P42) were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg i.p.). The anesthetized animals were transcardially perfused with 0.01 m sodium phosphate buffer plus 0.89% NaCl (PBS) followed by PBS-buffered 4% paraformaldehyde and 0.2% picric acid. Brains were removed, postfixed for ~12 h at 4 °C, then blocked, and placed in a solution of fixative containing sucrose (30% w/v) for cryoprotection. Sections through the cortex were taken at 50 μm on a freezing microtome (VT1000 Leica, Bannockburn, IL, USA), rinsed several times in PBS containing 0.5% Triton X-100 (PBST), and incubated in 10% normal goat serum for 1 h to block nonspecific binding. The sections were subsequently incubated in NeuroMab monoclonal antibodies to Kv2.1 (K89/34; 10 μg/mL; NeuroMab #73-014) and Kv2.2 (N372B/1: NeuroMab #73-369; N372B/60: NeuroMab #73-360; N372C/51: NeuroMab #73-358). After three rinses in PBST, the sections were incubated in the secondary antibody: Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated goat antimouse IgG1 (1:200, Vector Labs) for 4 h at room temperature. The sections were rinsed several times in PBST, mounted on a glass slide, and cover-slipped with polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) solution containing 6 g/25 mL glycerol, 2.4 g/25 mL PVA, 0.625 g/25 mL of the antifade reagent 1,4 diazabicyclo[2.2.2]octane, brought to 25 mL with 6 mL dH2O, and 12 mL PBS (all reagents, Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA). These sections were viewed with a Zeiss 710 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). Positive transgenic EYFP neurons were examined with a laser excitation wavelength of 488 nm, whereas neurons immunostained for Kv2.1 or Kv2.2 with Alexa Fluor 568-labeled secondary antibody were examined with a 568-nm laser line. The optical section thickness was 2 μm. Sections were viewed singly or in stack sections using ×20 (NA 0.8) or ×40 oil immersion objectives (NA 1.3). Confocal images (1024 × 1024 pixels) were viewed with Zen (Carl Zeiss) or ImageJ (NIH) software. The final confocal figures were made in Adobe Illustrator, with minimal alteration in dynamic range.

Slice recordings contained Neurobiotin in the internal solution for preservation of cell localization and structure using a diaminobenzidine (DAB)-based processing (described in detail in Marx et al. 2012). Following withdrawal of the pipette after recordings, slices were transferred to 3% glutaraldehyde in phosphate buffer (PB) and stored at 4 °C for several days. The cells were then incubated in 0.5% Triton-X PB and 1% hydrogen peroxide for 3 h, followed by an overnight incubation in Avidin-DH and Biotinylated horseradish peroxidase. The slices were then incubated for 1 h in the DAB stock, which was oxidized by dilutions of 3% hydrogen peroxide in water. The slices are mounted on slides for light microscopy with a Eukitt (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) embedding. Kole (2011) has shown that a longer preserved axon in layer 5 PNs studied in vitro was associated with burst firing occurring. We tested if a longer axon length was related to the likelihood of repetitive bursting after Kv2 channel block during the noisy current injections in the 17 neurons included in Figure 8. Neurobiotin fills were obtained for 14 of the 17 neurons and we measured the axon length that was clearly traceable (axon length measurements were not corrected for tissue shrinkage). The mean axon length ± SD was 154 ± 181 μm in the group without repetitive bursting (n = 7) compared with 64 ± 37 μm in the repetitive bursting group (n = 7), P = 0.22 (two-tailed students t-test). For neurons tested with DC current steps, we recovered neurobiotin fills in 34 neurons. The mean ± SD axon length was 92 ± 62 μm in 23 neurons that had only an initial burst (in GTx) and was 93 + 87 μm in 11 neurons that had repetitive bursting (nsd; P = 0.97, two-tailed students t-test).

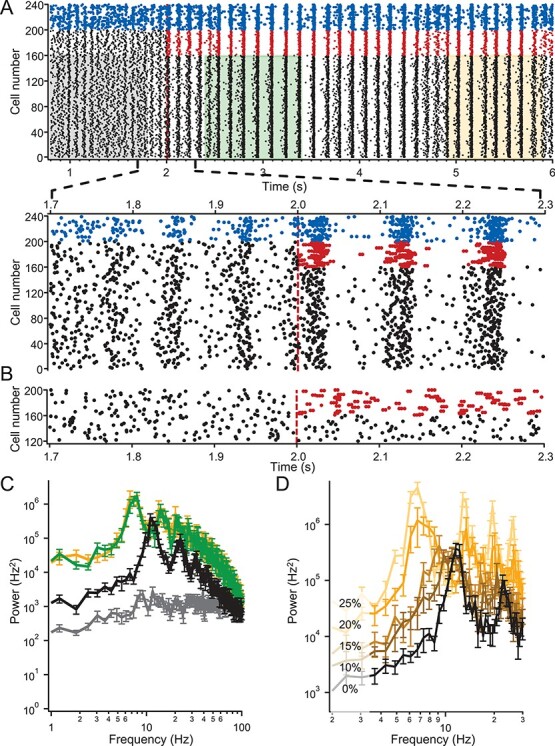

Figure 8 .

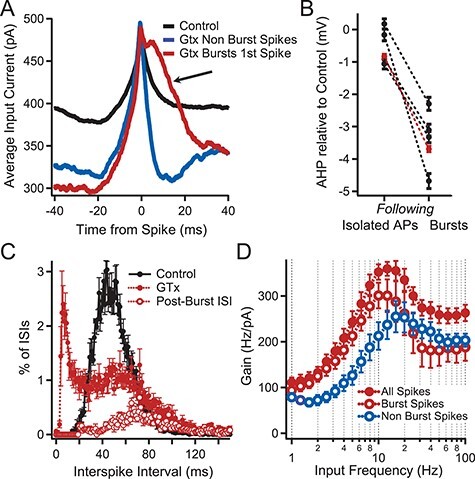

Effect of repetitive bursting on firing resonance. (A) Spike triggered average (STA) of the injected current that evoked APs from the subset of neurons in Figure 7E in which ≥40% of their APs were contained in bursts during noisy current injection (n = 4). STAs were determined from 1) all APs in the four neurons in control solution (black), 2) from APs not contained in bursts during GTx application (blue), and 3) from the first AP in a GTx-induced burst (red). Note the enhanced amplitude of the average stimulus current following the first AP contained in a burst (arrow). (B) Comparison of the mean mAHP amplitude following isolated APs to the mAHPs following bursts. Connected black circles represent values from the same cell. Red circles represent the mean of all mAHP measurements from the four cells with mean ± SEM at −0.83 ± 0.08 mV following isolated spikes and −3.69 ± 0.09 mV following bursts (7563 mAHPs after isolated APs vs. 4263 mAHPs after bursts; P < 0.001 unpaired Student’s t-test). Values are relative to the mean size of the mAHPs from the same cell in control solution. (C) Plot of the ISI histograms for the four neurons of A in control (black) and GTx (red). Also plotted is the distribution of intervals between the end of a burst and the beginning of the next postburst AP (postburst ISI, open red circles). Error bars indicate SEM in B—D. Note that the postburst ISIs comprise the majority of the ISIs longer than 70 ms after GTx with mean = 89 ± 5.4 ms. (D) Superimposed plots of gain versus input frequency in GTx for the four neurons of A. The solid red circles show all APs for these cells. The open red circles show the subset of APs contained in bursts. The open blue circles indicate the subset of APs not contained in bursts. Note the peak gain shifts to a lower frequency for APs contained in bursts compared with APs not contained in bursts.

Analysis

Analysis of Voltage Clamp (Outside-Out Macropatch) Experiments

Data were obtained at 10 kHz and filtered at 4 kHz. To determine steady-state voltage-dependence, a family of 500 ms voltage steps were made from a holding potential of −80 mV to voltages between −50 and +50 mV in 20 mV increments (20s between sweeps). This protocol was run in control solution and repeated after application of 100 nM GTx. The GTx-sensitive current was obtained by subtracting traces in GTx from control traces. Current at 500 ms was converted to conductance by dividing current by driving force (E-EK+; EK+ was calculated as −102 mV from the internal and external K+ concentrations). Conductances were normalized by the maximum conductance and the normalized conductance was plotted as a function of test voltage. These data were fit with a single Boltzmann relationship (equation (1)).

|

(1) |

where G is the calculated conductance, Gmax is the maximal conductance, V is the step potential, Vh is the half-activation or half-inactivation voltage, and Vslope is the slope. Data were well fit by a single Boltzmann equation.

To determine activation and inactivation kinetics, we fit the rising phase and decay phase of currents, each with a single exponential (first order: equation (2)). A 500-ms step from −75 to 0 mV was used (20 s between steps). GTx-sensitive currents without a readily observable A-current component (identified as a fast peak in the first 2 ms after step onset in a few recordings) were used to fit the following activation–inactivation equation:

|

(2) |

where I(t) represents the GTx-sensitive current, τ0 is the activation time constant, and τ1 is the inactivation time constant.

Spike Detection and Threshold

Current-clamp recordings were digitized and action potentials were detected when the spike overshoot was greater than 0 mV. Spike threshold was calculated by giving the cell a series of identical pulses where the current elicited an action potential on approximately 50% of the trials. Trials that did not induce an action potential were averaged and the voltage level at the end of the trajectory was collected and reported. We found this to be a more consistent and precise measurement of threshold compared with the dV/dt > 20 mV/ms that we used for spike timing.

Normalization of Interspike Interval Histograms

The interspike interval histograms in Figures 7C and 6E,F were all performed the same way. The interspike interval was calculated from the time difference in measured threshold (the point where dV/dt > 20 mV/ms) between spikes. The interspike intervals for a given cell was plotted with a bin size of 0.5 ms and a maximum bin of 150 ms. Each cell was then normalized by dividing the histogram by the number of total spikes analyzed for that cell to convert spike count to “percentage of total spikes.” We then were able to average histograms across cells and apply statistics to the results.

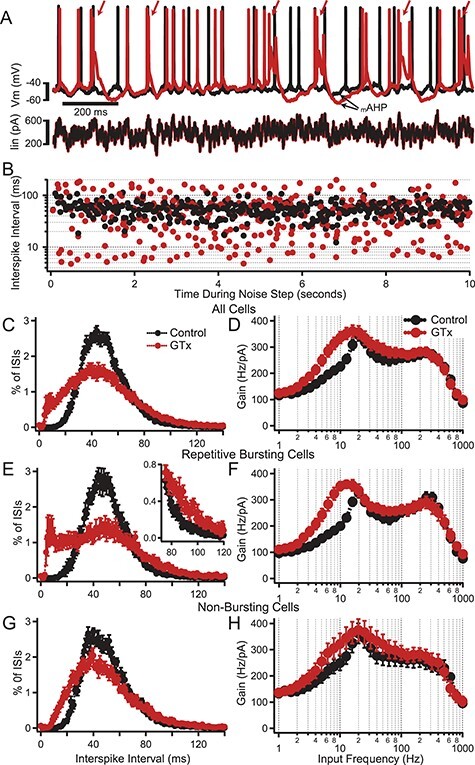

Figure 7 .

Effect of GTx on the frequency dependence of AP firing gain. (A) Superimposed voltage traces (upper) showing the initial AP firing response to a noise plus DC current step (lower) in control solution (black) and in GTx 100 nM (red). Mean firing rate during the 20-s step was maintained at 20 Hz by adjustment of the DC component of current injection. Note that in this neuron, GTx caused repetitive bursts of AP firing (arrows). (B) Semilog plots of ISI versus time (control and GTx) for the neuron shown in A. GTx caused at shift from a uniform distribution of ISIs centered around the mean firing rate (control, black) to a bimodal distribution with a subset of much shorter ISIs (GTx, red). (C) Normalized ISI histogram for all neurons receiving a 2 mV standard deviation noisy current input and driven to spike at 20 Hz with DC current injection in control (black) and GTx (red), n = 17. Error bars in C—H are mean ± SEM. (D) Plots of gain of AP firing as a function of frequency component of the input noise for the neurons in C. (E) Plots of ISI histograms as in C but for the subset of neurons that showed repetitive bursting in GTx (n = 8). Neurons were selected as repetitive busters (in GTx) if the ISI histogram showed a clear bimodal distribution of ISIs with a second peak <20 ms. Note the approximate doubling of the percent of 90 ms ISIs in GTx (inset). (F) Gain versus frequency plots for neurons showing repetitive bursting in GTx. (G) Plots of ISI histograms for the subset of neurons in which GTx did not cause repetitive bursting (n = 9). (H) Gain versus frequency plots for nonrepetitive bursting neurons.

Figure 6 .

Effect of GTx on repetitive firing. (A) Superimposed voltage traces of AP firing in control (black) and GTx 100 nM (red) evoked by a long 600 pA current step from −70 mV. Note the enhanced duration and amplitude of the mAHP following a burst of APs. (B, C). Firing rates (in Hz) for the initial three interspike intervals (ISIs) evoked by long current steps plotted as a function of the current step amplitude in control (B) and in GTx (C), (n = 23, error bars = SEM). The spike rate is calculated from 1/ISI for each of the first three ISIs. (D) Histogram of number of onset short-interval APs (i.e., single-onset APs, doublets, or bursts) before (control) and after GTx. Each cell was counted once in the column representing the most onset APs seen at any level of DC current ≤1.8 nA (n = 43). (E) Plot of AP firing frequency as a function of the mean current step amplitude for DC-only steps and DC plus noise steps (exponentially filtered noise, τ = 5 ms: the amplitude of the noise current fluctuation was set to give a 2 mV standard deviation of membrane potential when the mean Vm was maintained at −70 mV). Spike rate was calculated for the final second of a 3-s current step (i.e., after repetitive bursting had stopped). DC current only, filled circles; DC current plus noise, open circles; control, black; GTx, red; n = 4.

STA Analysis

The spike-triggered average (STA) was calculated using the following: For n spikes, ISTA was calculated as the mean Inoise at a time delay τ with respect to each spike time, t:

|

(3) |

Gain–Frequency Analysis

The frequency-dependence of the gain was quantified by correlation analysis of responses to noisy current where the target firing rate was set to 20 Hz and adjusted by DC input. The stimulus–response correlation and stimulus autocorrelation were combined with time differences and stimulus to obtain Fourier components that were used to calculate the frequency-dependent gain as described in depth in Higgs and Spain (2009). The gain–frequency plot shows the relative efficacy of each frequency component of the noisy current input to modulating firing rate and as such it is a measure of suprathreshold resonance. Note that the gain–frequency analysis provides the local linear response for a given firing rate and set of noise statistics (e.g., time constant, SD). Any change in those variables can (and does) cause some shift of the neurons’ resonant firing properties (Higgs and Spain 2009).

Spectral Analysis of In Silico Neuron Network

To analyze the spectral components of the collective network output, all of the spike times were collapsed into a single train and convolved with a Gaussian function with an SD of 10 ms to generate an instantaneous network firing rate. From this estimate of the network firing rate, we performed a fast Fourier analysis and calculated the power density spectrum as the square of the frequency components.

Statistics

Prism (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) software was used to perform statistical tests on the data obtained from the PNs. For CV measurements, a one-way randomized block ANOVA (experiments were treated as matched sets to account for experiment-to-experiment variability) with post-hoc Tukey’s multiple comparisons test was used to determine which individual CV means differed, and summary data are presented as across-replicate means ± SEM. Paired t-tests were used to compare control versus drug effects. For all tests, P values <0.05 were considered to be significantly different. Sample population data and error bars in plots are represented as mean ± SEM unless otherwise specified.

The In Silico Simplified Neuron Network

Simulations were performed using MATLAB (Mathworks, Nattick, MA), with each voltage integration calculated by first-order Euler integration with a time increment of 0.05 ms.

The network model contained interconnected excitatory (E) and inhibitory (I) neurons. For E neurons, we used a single-compartment, leaky integrate-and-fire (LIF) neuron with conductances (g) for the fADP, mAHP, and a Kv2-like conductance designed to capture experimentally measured features of Thy1 neuron-firing properties under normal conditions and after block of Kv2 channels with GTx. The I neurons were single-compartment LIF neurons without added conductances. The parameters for the E and I neurons are shown in Table 1 (for E neurons in GTx, gKv2 was set to zero and the post-AP reset was −58 mV instead of −60 mV).

Table 1.

Parameter settings for the model neurons.

| LIF neuron parameters | E | I |

|---|---|---|

| Membrane capacitance, Cm | 500 pF | 400 pF |

| Leak conductance, gLeak | 20 nS | 15 nS |

| Initial Vm | −70 mV | −80 mV |

| Spike threshold, Vthreshold | −55 mV | −56 mV |

| Postspike reset potential, Vreset | −60 mV | −60 mV |

| Absolute refractory period | 2 ms | 2 ms |

| fADP conductance increment, ΔgfADP | 18 nS/spike | n/a |

| fADP decay time constant, τfADP | 1.4 ms | n/a |

| fADP reversal potential, EfADP | 70 mV | n/a |

| mAHP conductance increment, ΔgmAHP | 9 nS/spike | n/a |

| mAHP decay time constant, τAHP | 50 ms | n/a |

| mAHP reversal potential, EmAHP | −100 mV | n/a |

| Kv2 conductance increment, ΔgKv2 | {0, 30} nS/spike | n/a |

| Kv2 decay time constant, τKv2 | 5 ms | n/a |

| Kv2 reversal potential, EKv2 | −100 mV | n/a |

When Vm was negative to Vthreshold, the model behaved according to the following (see Table 1 for the E and I LIF neuron parameters):

|

(4) |

where Vm is membrane voltage, t is time, Cm is membrane capacitance, and Im is membrane current.

|

(5) |

and

|

(6) |

where Ioffset was the level of DC current and the noisy current component, Inoise, was created by convolving pseudorandom points chosen from a Gaussian distribution from −1 to 1 for each time interval, t, with an exponential filter, exp(−t/τ), where τ = 3 ms for inhibitory neurons and τ = 5 ms in excitatory neurons. This pseudorandom series was multiplied by a specified amount of current to get the desired SD (the DC level and SD of the noise are specified for each experiment in results).

To generate a randomly connected network, pseudorandom numbers between 0 and 1 were selected for every connection (regardless of type). Any random number greater than the probability of connection was made zero (unconnected). Subsequently, all autapses were removed. Random connections between neurons were set to 10% of the total possible, with autapses removed (e.g., a network of 100 neurons had ~1000 connections out of a possible 9900).

Individual excitatory and inhibitory synaptic conductances (gEsyn and gIsyn) were each calculated as the sum of two exponentials (fast rise and slow decay):

|

(7) |

where  was the conductance of

was the conductance of  or

or

was their maximum conductance, which was set to 4 nS for both; τrise and τdecay were rise and decay time constants: τrise = 0.2 ms and τdecay = 2 ms for excitatory conductances and τrise = 0.5 ms and τdecay = 5 ms for inhibitory conductances. To ensure the amplitude equaled

was their maximum conductance, which was set to 4 nS for both; τrise and τdecay were rise and decay time constants: τrise = 0.2 ms and τdecay = 2 ms for excitatory conductances and τrise = 0.5 ms and τdecay = 5 ms for inhibitory conductances. To ensure the amplitude equaled  , a normalization factor for the amplitude f was included, which was the inverse of the sum of the two exponentials at the peak of their sum in time. The start time for each conductance t0 was set by a synaptic delay of 1.5 ms after the presynaptic spike. Reversal potentials for these conductances were EEsyn = 0 mV and EIsyn = −70 mV.

, a normalization factor for the amplitude f was included, which was the inverse of the sum of the two exponentials at the peak of their sum in time. The start time for each conductance t0 was set by a synaptic delay of 1.5 ms after the presynaptic spike. Reversal potentials for these conductances were EEsyn = 0 mV and EIsyn = −70 mV.

For every neuron, the total excitatory synaptic conductance (gEtotalsyn) was the summed value of each of the individual excitatory synaptic conductances (gEsyn) impinging onto that neuron at that time step and the total inhibitory synaptic conductance (gItotalsyn) was the sum of the individual inhibitory synaptic conductances (gIsyn). The resultant synaptic currents were added with the other membrane currents to make Im (as in equation (5)), which was in turn summed with the “external” current (Istimulus).

After reaching Vthreshold, Vm was set to Vreset for an absolute refractory period of 2 ms. Whenever threshold was reached, gfADP, gmAHP, and gKv2 were increased at the next time point by the Δg amounts and decayed on subsequent time steps with the time constants listed in Table 1.

Results

Guangxitoxin-1E (GTx) Causes Action Potential Bursting in Thy1 Neurons

We focused on identifying the potassium conductance that regulates the occurrence of burst firing in ET-type PNs. We concentrated our studies on Thy1 PNs in acute brain slices from motor cortex because that region contains a particularly high density of L5-ET neurons. In initial experiments, we measured membrane voltage responses under conditions designed to mimic synaptic input onto the spines of the Thy1 proximal dendrites using two-photon glutamate (2p-glu) uncaging. Somatically recorded postsynaptic potentials evoked by 2p-glu at individual spines had an average amplitude of 0.3 ± 0.02 mV and a half duration of 14.1 ± 1.0 ms (n = 4 cells and 113 spines). Stimulating a group of 21 to 31 nearby spines on one dendrite nearly simultaneously (Fig. 1A,B) evoked a large EPSP (7.3 ± 2.0 mV measured at the soma, n = 4; Fig. 1E). When this dendritic stimulation was combined with somatic DC current injection to depolarize the membrane potential, one or two APs were triggered, followed by a fast afterdepolarization (fADP) that decayed over ~15 ms. We hypothesized that Kv2 channels might play a key role in shaping how dendritically evoked events are integrated in Thy1 PNs.

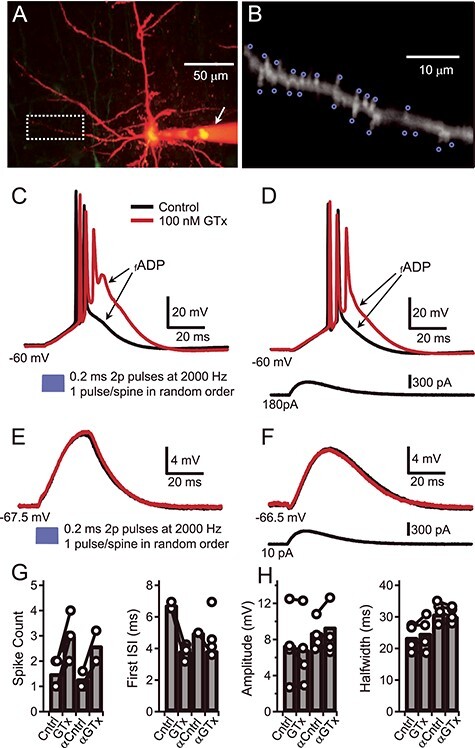

Figure 1 .

Block of Kv2 by GTx induces burst firing in Thy1 PNs. (A) Composite maximum projection from a Z-stack of two-photon images of a Thy1 PN in layer V of motor cortex filled with Alexa 594 (20 uM). The arrow indicates the Alexa containing microelectrode that was used for somatic current injection. Background florescence has been digitally reduced. (B) Magnification of the basal dendrite shown in A (white box) with blue circles to indicate the target areas adjacent to individual spines that were used to photolyze MNI-glu (bath applied, 4 mM; see Materials and Methods). (C) Voltage traces show suprathreshold dendritic branch activation after photolysis of MNI-Glu. The soma was depolarized to −60 mV via positive somatic current injection and glutamate was uncaged at each of the 19 foci indicated in B in random order (blue trace: the 2P laser light was on for 0.2 ms at each spine, wavelength, 720 nm; the repositioning interval, light off, was 0.3 ms). The somatically recorded voltage responses are shown before (black trace) and during bath application of GTx 100 nM (red trace). (D) Suprathreshold voltage responses before and during GTx in response to somatic injection of an alpha-EPSP waveform during somatic depolarization to −60 mV. (E) Subthreshold membrane voltage responses (at RMP) before and during GTx to 2P-uncaged glutamate (as in C). (F) Subthreshold voltage responses evoked by an alpha-wave current injection (near RMP). (G) Plots of spike count (left), and first ISI (right) for suprathreshold responses before (Cntrl) and during GTx to uncaged glutamate and to an alpha-wave (αCntrl, αGTx). Connected circles indicate values from the same cell; bars indicate mean of four cells. (H) Plots for subthreshold voltage response amplitudes (left) and half-widths of the same four cells in G.

To study the filtering effects of Kv2 channels on the 2p-glu evoked responses we used the selective Kv2 channel blocker GTx (Herrington et al. 2006; Liu and Bean 2014; Bishop et al. 2015; Hönigsperger et al. 2017; Pathak et al. 2016). Extracellular bath perfusion with GTx (100 nM) enhanced the fADP amplitude and increased the number of short-interval APs (i.e., a burst of spikes, as in Fig. 1C) driven by the dendritic stimulation. These data suggest that current through Kv2 channels dampens the fADP in Thy1 PNs and limits bursting. When the holding current was reduced to allow baseline membrane potential to return to resting membrane potential (RMP), 2p-glu uncaging resulted in a subthreshold EPSP that was unaffected by GTx (Fig. 1E). Additionally, GTx had the same effect on supra- and subthreshold voltage responses in response to injection of an alpha function–shaped depolarizing current at the soma (Fig. 1D,F). Combined, these data suggest that Kv2 is minimally active at subthreshold voltages in the absence of spiking. Further, these data suggest that the Kv2 channels are located near the soma and exert their effects on the 2p-glu-induced depolarization at or near the soma, rather than locally in the dendrites. We set out to test these suggestions.

Functional Kv2.1 Channels Are Expressed on the Soma and Proximal Dendrites of Thy1 PNs

Previous work by our lab and others have shown that Kv2 channels have a perisomatic localization in PNs, including soma, proximal dendrites, and the AIS (Trimmer 1991; Misonou et al. 2005; Guan, Armstrong, et al. 2007a; Guan et al. 2013; Sarmiere et al. 2008; Bishop et al. 2015), but the distribution of Kv2 channels in Thy1 PNs in the motor cortex had not been characterized. The Bishop et al. (2015) study showed that Kv2.1 channels were present on the soma and proximal dendrites (~first 50 μm) of both IT-type (etv1) and ET-type PNs (glt25). In contrast, Kv2.2 channels were expressed in the same subcellular locations in etv1 PNs but were not found in glt25 PNs. Based upon this work, we hypothesized that the ET-type Thy1 PNs would show a similar expression pattern to glt25 PNs: that is, no Kv2.2 expression and perisomatic Kv2.1 expression. We tested this hypothesis on Thy1 PNs by immunocytochemistry (Fig. 2A,B). Briefly, Kv2.1 and Kv2.2 expression was characterized using the K89/34 (for Kv2.1) and N372B/1 or N372B/60 (for Kv2.2) antibodies (both from NeuroMab) in 4 Thy1 mice (P26–P42) (see Materials and Methods). Consistent with previous work on neocortical PNs, we found that Kv2.1 subunits were ubiquitously expressed in clusters on the membrane of the soma, AIS (Sarmiere et al. 2008), and proximal apical and basal dendrites (first 50–100 μm) of Thy1 (EYFP-positive) and EYFP-negative PNs throughout layer 5 (and also ~all PNs in the other layers). We observed Kv2.1 expression in the proximal dendrites (apical and basal) and in the AIS, but as shown before (Trimmer 1991; Bishop et al. 2015), there was little evidence for expression in distal dendrites. Kv2.2 expression was nearly absent on the Thy1 neurons, although it was clearly expressed in EYFP-negative PNs in layer 5. These data show that Thy1 PNs express Kv2.1 in perisomatic compartments and generally do not express Kv2.2 channels (similar to glt25 PNs). The dominant somatic location strategically places Kv2.1 channels for regulating the effects of inward currents reaching the soma from either the dendrites or the AIS.

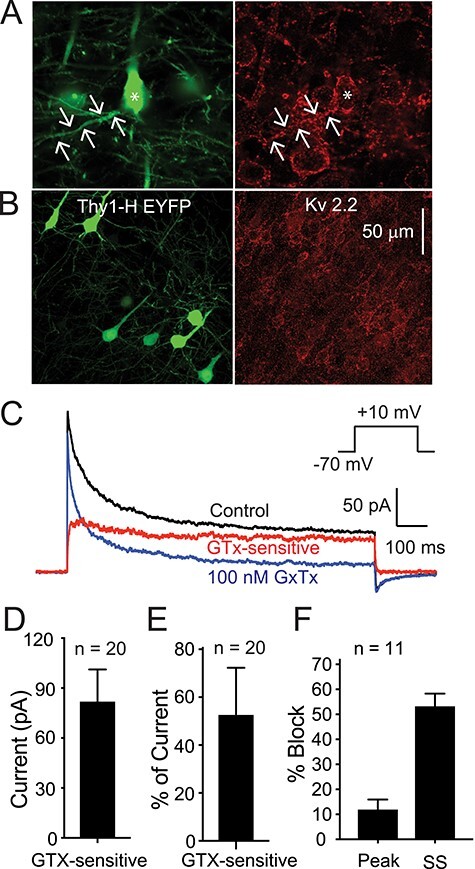

Figure 2 .

Kv2 channel expression on Thy1 PNs in neocortex. (A) Photomicrographs showing Thy1 (EYFP positive) L5 PNs from motor cortex (left panel) and immunocytochemistry for Kv2.1 (Neuromab K89/34: right panel). Scale bar applies to both images. Arrows indicate a basal dendrite. Note Kv2.1 is expressed on all PNs (EYFP positive and EYFP negative) on the soma and first 50–100 μm of the apical and basal dendrites. (B) Similar images showing EYFP (to indicate Thy1 PN: left) and immunostaining for Kv2.2 (Neuromab N372B/1: right). Note that there is very little Kv2.2 expression on the EYFP-positive (green) PNs. Most of the Kv2.2 staining is on EYFP-negative (non-Thy1) PNs. (C) Current traces obtained from an outside-out macropatch from the soma of a Thy1 PN from layer 5 of motor cortex (voltage protocol in inset). The black trace is in control solution, the blue trace is in the presence of 100 nM GTx), and the red trace is the GTx-sensitive current. In this cell, there is a clear fast transient component to the current in control solution (black). 100 nM GTx (blue) blocks a large percentage of the sustained current with only a small effect on the fast, transient current. (D, E) Summary data for voltage-clamp data from 20 macropatches that did not have an obvious “A” current component (from 20 Thy1 PNs). (D) Summary data for 20 macropatches for absolute current blocked by 100 nM GTx. (E) Summary data for percentage of the current that was GTx-sensitive (measured at 500 ms). (F) Summary data for percentage of peak current versus steady-state current (SS: at 500 ms) blocked by 100 nM GTx in 11 macropatches with a clear transient “A” component to the control current (see text for further explanation).

Kv2 channels are one of several potassium channels that contribute to the sustained outward current in pyramidal neurons in response to long-lasting depolarization. We next used outside-out macropatch voltage clamp (VC) recordings pulled from the somas of Thy1 PNs (capacitance of ~2–4 pF; see Bishop et al. 2015) to test for functional expression of Kv2 channel current and to determine its biophysical properties.

We first examined the affinity and selectivity of GTx for Kv2 channels in PNs. Preliminary experiments in acutely dissociated Thy1 PNs revealed that the EC50 for GTx was ~14 nM (n = 4 cells, data not shown). We then examined selectivity in macropatches, using 0.5–1 s steps from a holding potential of −70 mV to a test potential of +10 mV (Fig. 2C). Not all somatic macropatches exhibited an obvious fast, transient “A-type” component to the current, consistent with the underlying Kv4 channels being in much higher density in the dendrites and the fact that the macropatches do not include the entire somatic membrane. In 11 macropatches that did have a clear initial A-type peak current followed by steady-state current (Fig. 2F), we found that 100 nM GTx blocked 65.6 ± 7.8% of the steady-state current (measured at 500 ms) but only 12.2 ± 3.8% of the peak current (or 6.6 ± 2.9% of A-type current, defined as peak–steady state). In 20 macropatches without a clear “A” component, GTx blocked 53.3 ± 4.1% of the steady-state current versus 58.8 ± 4.9% of the peak current. Collectively, these data suggest that 100 nM GTx blocks most of the putative Kv2-mediated current but only ~6% of transient, A-type current. Thus, GTx is selective for the sustained K+ current (putative Kv2 current; see also Liu and Bean 2014; Bishop et al. 2015; Hönigsperger et al. 2017), comprising ~55% of total slowly inactivating K+ current (Fig. 2C,D). The average Kv2 current amplitude in the macropatches was 216.3 ± 34.3 pA at the peak and 74.8 ± 16.3 pA at 500 ms (n = 20 patches; Fig. 2D). Our data show that Kv2 currents are the largest component of the sustained Kv currents in Thy1 PNs.

AmmTx3 has been shown to selectively block Kv4 channels in association with dipeptidyl peptidase–like proteins (Maffie et al. 2013) and we previously found it to be selective for the A-type current in two other layer 5 PN subtypes, etv1 and glt25 (Pathak et al. 2016). As a further test of selectivity of GTx for Kv2 versus Kv4 channels, we used whole-cell voltage clamp in brain slices to compare current blocked by 100 nM GTx to that blocked by 400 nM AmmTx3. We used a protocol designed to isolate Kv4 current by subtraction (Supplementary Fig. 1). With a test step to −30 mV (a potential where it is easier to separate A-type vs. sustained K+ current), GTx blocked 31 ± 6% of the steady-state current (at 500 ms) but only 3.7 ± 3.4% of the early peak “A” current (n = 4 cells). In contrast, AmmTx3 blocked 54.3 ± 7.6% of the early peak A current versus 0.4 ± 0.8% of the steady-state current. Thus, GTx is selective for the largest component of the sustained current and AmmTx3 is selective for A-type current in Thy1 PNs.

Characteristics of Kv2 Currents from Thy1 Somas

We next used outside-out macropatches from Thy1 PN somas and standard activation and inactivation VC protocols (see Materials and Methods) to determine steady-state activation and inactivation properties for the GTx-sensitive current. Previous work has found that in many PN types, Kv2 channels activate at relatively depolarized potentials compared with Kv1 or Kv7 (Murakoshi and Trimmer 1999; Guan,, Armstrong, et al. 2007a; Guan et al. 2013; Liu and Bean 2014; Bishop et al. 2015). In IT-type etv1 PNs however, both Kv2.1 and Kv2.2 are expressed and the presence of Kv2.2 shifts activation to more negative potentials (including subthreshold voltages: Bishop et al. 2015). In contrast, in ET-type glt25 PNs, only Kv2.1 is expressed and the voltage range for activation is more depolarized. We therefore hypothesized that the ET-type Thy1 PNs would have a positive activation range for Kv2 current, since only Kv2.1 is expressed in these cells (Fig. 2A,B).

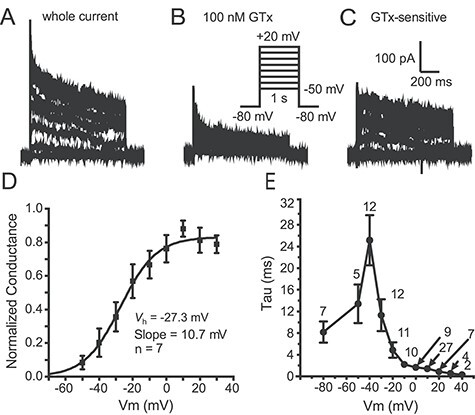

We tested activation kinetics and voltage-dependence with a family of 1 s steps to various potentials between −50 and +20 mV (10 mV increment). Putative Kv2-mediated current was isolated by subtraction of records in 100 nM GTx from control currents (Fig. 3A–C). Figure 3D shows an average steady-state activation curve obtained from 7 cells. In contrast to our hypothesis, the GTx-sensitive current in Thy1 PNs activates at relatively negative potentials, with an average half-activation voltage (V0.5) of −27.3 mV and slope of 10.7 mV (Fig. 3D). Despite the absence of Kv2.2 channels, this is similar to activation of Kv2 in etv1 PNs but negative to that in glt25 PNS (Bishop et al. 2015). Figure 3E shows the voltage dependence of the activation time constant, τ, measured by fitting the rising phase of the current at various test potentials (exception: the −80 mV point is the deactivation τ at the holding potential). Figure 3E includes the data obtained at +10 mV for the seven cells tested at multiple potentials to determine the steady-state activation curve (Fig. 3A–D) plus 20 macropatches tested at +10 mV only. For the 20 macropatches tested with a single step to +10 mV, the τ was well fit with a single exponential with activation τ = 1.45 ± 0.22 ms and deactivation τ = 8.4 ± 1.8 ms (at −80 mV). Thus, these currents activate moderately rapidly and at subthreshold potentials and could influence AP threshold and postspike potentials (although they may activate too slowly to greatly influence AP properties: e.g., Pathak et al. 2016).

Figure 3 .

Characteristics of Kv2 current in Thy1 neurons. (A) Example traces from a somatic outside-out macropatch in control solution (voltage protocol in inset in B). (B) Traces from the same macropatch during application of 100 nM GTx. (C) The GTx-sensitive current was obtained by subtraction. It activated relatively rapidly and inactivated slowly. (D) Summary activation voltage-dependence data for seven macropatches (mean ± SEM). The half-activation voltage (V0.5) and slope are indicated on the graph. (E) Summary data for time constant (Tau) for activation and deactivation as a function of voltage (Data include 7 macropatches where we stepped to all voltages, as in D. At +10 mV, we had an additional 20 patches so n = 27). We fit the rising phase of the GTx-sensitive traces to obtain the time constants from above −50 mV, and we fit to the tail currents from the +10 mV step to voltages below −30 mV.

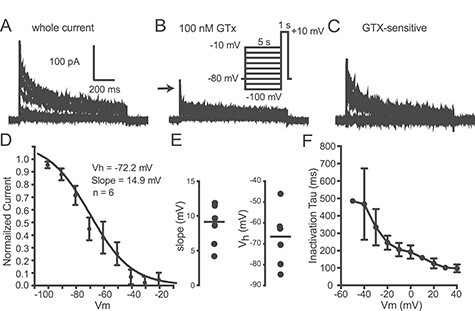

We also studied steady-state inactivation using outside-out macropatches from Thy1 PN somas. The macropatches were held at −80 mV and then stepped to various potentials for 5 s before a test step to +10 mV (for 1 s) (Fig. 4). Currents were obtained before and during bath application of 100 nM GTx and the GTx-sensitive current obtained by subtraction (Fig. 4A–C). The currents were normalized to the largest current and plotted as a function of prepulse voltage (Fig. 4D). The data were well fit by a single Boltzmann equation (see Materials and Methods) with a half inactivation voltage (Vh) of −72.2 mV and slope of 14.9 mV (n = 6 macropatches; Fig. 4D,E). This is a fairly hyperpolarized inactivation Vh (e.g., more negative than Kv1 currents in layer 5 PNs: Guan et al. 2018). The kinetics of inactivation were obtained by fitting the decay of currents elicited by the activation protocol (Fig. 3) and are relatively slow (n = 6 macropatches; Fig. 4F). At +10 mV, the inactivation τ = 148.3 ± 25.3 ms. The slow inactivation and deactivation of Kv2 channels would facilitate regulation of afterpotentials and repetitive firing.

Figure 4 .

Steady-state inactivation. (A) Representative current traces from an outside-out macropatch in control solution in response to voltage protocol shown as inset in B. (B) Traces from the same macropatch in the presence of 100 nM GTx. Inset: voltage protocol for A–C. (C) GTx-sensitive currents for same macropatch as A and B. (D) Plot of peak current normalized to maximum current. The mean data from six cells were well fit by a single Boltzmann function with the half-inactivation voltage (Vh) of −72 mV and slope of 14.9 mV. (E) Scatter plots (mean indicated by horizontal line) showing the slope and half-inactivation voltage (Vh) for the same six cells. (F) Summary data for the same six cells for the inactivation time constant, (t) as a function of voltage (taken from the activation protocol in Fig. 3). Data were fit by a single exponential.

In summary, the properties of Kv2 channels are well suited to shape how Thy1 PNs respond to strong synaptic activity. Based on their perisomatic location and the fact that they are the largest sustained K+ current, Kv2 channels would be expected to filter the summed synaptic input from all dendrites. Based on the biophysical properties, a substantial amount of Kv2 conductance would be activated during spiking and could contribute to postspike membrane potential trajectories that control onset bursts and repetitive burst firing, depending on its contribution relative to other conductance mechanisms.

Kv2 Conductance Raises AP Threshold and Dampens the fADP

We next tested the effect of blocking Kv2 channels on AP firing evoked by various somatically injected current waveforms. All experiments employed whole-cell current-clamp and measurement of the membrane voltage output before and during application of GTx. Consistent with the voltage dependence of Kv2 channels in the macropatch experiments, GTx had no significant effect on the subthreshold current versus voltage relationship with current pulses of up to 1-s duration (steady-state input resistance for 43 cells in control: 37.1 ± 2.2 MΩ; GTx: 35.3 ± 2.5 MΩ).

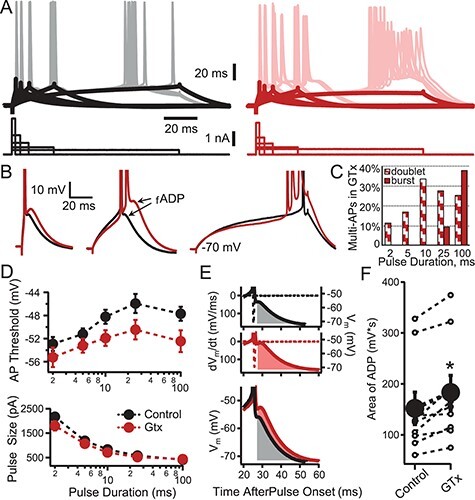

To study the effects of Kv2 conductance on the transform of somatic current into AP firing, we used brief current pulses (2 ms to 100 ms) whose amplitude was adjusted to evoke an AP on 50% of trials for a given duration pulse (Higgs and Spain 2011). This method allows attainment of spikes in response to different rates of depolarization and allowed us to measure the effect of blocking Kv2 channels on AP threshold, as well as threshold accommodation, AP time course, and the membrane voltage trajectories following an AP (Fig. 5A,B). Consistent with the activation of Kv2 current near AP threshold in Thy1 neurons, block of Kv2 resulted in a 2–4 mV negative shift in the voltage for AP threshold (for the first spike in response to a depolarizing current pulse). This effect was evident for all durations of current injections but only reached statistical significance for the 10 and 25 ms steps (P < 0.05, two-tailed Student’s t-test; Fig. 5). In contrast, GTx had only a minimal effect on spike threshold accommodation, defined as a change in threshold dependent on the rate of depolarization (i.e., in GTx, there was a parallel shift in voltage threshold as a function of duration of current injection; Fig. 5D, upper). This result differs from the strong contribution that Kv1 channels have on accommodation, presumably because of the more rapid activation kinetics of Kv1, as well as their dominant location near the spike initiation zone of the AIS compared with Kv2 (Kole et al. 2007; Ogawa et al. 2008; Higgs and Spain 2011).

Figure 5 .

Effect of GTx on action potential threshold and the fADP. (A) Representative somatic whole-cell current-clamp recording of a Thy1 PN in control (black, left) and in the presence of GTx 100 nM (red, right). Superimposed sweeps are shown of voltage responses (upper) evoked by current steps (lower) of varying duration (2, 5, 10, 25, and 100 ms). The amplitudes of the current steps were adjusted to elicit action potentials 50% of the time. The thick black and red lines denote the average voltage trajectory of nonspiking trials, which were used to facilitate measurement of spike threshold in traces when an AP was elicited. (B) Examples of suprathreshold voltage responses from 2, 25, and 100 ms current steps in control (black) and GTx (red). Note that GTx increases the size of the fADP and, in some cases, results in bursts of three or more APs. (C) Histogram showing the percent of cells that were converted in GTx to onset doublet or burst firing at each duration of current pulse. (D) The mean ± SEM for AP threshold (top) and current amplitude (bottom) is plotted as a function of the current step duration in control and GTx (black and red, respectively), n = 9. GTx caused a small decrease in AP threshold for all durations of current (significant for the 10- and 25-ms steps, P < 0.05, two-tailed Student’s t-test). (E) Example of the method used for quantification of the effect of GTx on fADP size during 25-ms current steps for control and GTx conditions. Only trials with a single AP during the 25-ms current step were used. The membrane voltage (solid lines) and dV/dt (dotted lines) are plotted versus time after current-step onset. The fADP size was calculated as the integral (shaded areas) of the postspike voltage after crossing dV/dt = 0 until the return of the baseline membrane voltage (−70 mV). The bottom panel shows the control and GTx conditions superimposed. (F) Comparison of fADP size (integrals of area after the AP as in D) in control and GTx (individual cells = open circles; mean ± SEM = closed circles, n = 9 cells; P < 0.0025 Student’s paired t-test).

Integrated rheobase was measured from the amplitude of the 100 ms current steps required to evoke an AP on ~50% of trials, multiplied by the time along the step when an AP first occurred (note APs often occurred before the end of the 100 ms current steps especially in GTx). Integrated rheobase was lower in GTx (mean ± SE = 31.3 ± 5.5 pA*s in control solution vs. 24.8 ± 4.0 pA*s in GTx, n = 8 cells, P = 0.03, two-tailed paired student’s T-test). We found small but significant effects of 100 nM GTx on AP amplitude (112 ± 2.7 mV control vs. 107 ± 2.95 mV GTx, n = 12. P < 0.02), and the rates of depolarization (dV/dt for upstroke of AP: 480 ± 26.5 V/s control vs. 452 ± 24.8 V/s GTx, n = 12, P < 0.04) and repolarization (dV/dt for downstroke of AP: 480 ± 26.5 V/s control vs. 452 ± 24.8 V/s GTx, n = 12, P < 0.04). There was no significant difference for AP half-width (for the initial evoked AP measured at one half the amplitude from RMP to the peak AP) in control (0.75 ± 0.04 ms) versus GTx (0.77 ± 0.03 ms, n = 12 cells, P < 0.13).

In control bath solution, Thy1 PNs respond to current injections with an initial single AP or a doublet (2 APs). As in the 2p-glu uncaging experiments, Kv2 block resulted in the conversion of the AP onset response to a burst of multiple spikes, especially for small and long current pulses that cause a shallow rise to the first AP. We define a burst as 3 or more APs generated at high frequency and arising from an fADP. Note that during such multispike bursts, the AP threshold becomes depolarized for APs subsequent to the first AP in the burst. The APs also become shorter and broader; thus, the depolarized voltage thresholds for APs occurring within the burst are likely due to accumulated inactivation of voltage-gated sodium channels. We found that under our recording conditions all neurons fired with a single AP at onset in control solution except for the 100 ms injections, where 1 of 9 responded with a doublet. In the presence of 100 nM GTx, onset firing was converted to doublet or burst firing in most cells when stimulated with a 100 ms pulse (Fig. 5B,C).

While the activation time constants measured from macropatches (~15 ms at membrane potential, Vm, near fADP occurrence and ~25 ms at −40 mV; Fig. 3E) are consistent with the minimal effect Kv2 block has on the AP waveform, Kv2 should activate rapidly enough to dampen the fADP following an AP. To examine this more closely, we measured the fADP as the integral of the area under the voltage trajectory following the AP until it crossed the resting potential and became an afterhyperpolarization (mAHP; Fig. 5E). We found that GTx caused a consistent and significant increase in the amplitude and area of the fADP (amplitude: −51.3 mV ± 1.1 in control vs. -48.34 mV ±1.3 in GTx, P < 0.0001; area: 152 ± 31.8 mV*ms in control vs. 183 ± 33.5 mV*ms in GTx, P < 0.0025; n-9, Student’s paired t-test).

Kv2 Conductance Limits both Onset and Repetitive Bursting in Thy1 Neurons

The experiments of Figure 5 suggested that Kv2 channel current decreases the likelihood of an onset burst by opposing the fADP. Conversely, reducing Kv2 current facilitates onset bursting. Repetitive bursting after stimulus onset is rarely observed in neocortical PNs under normal conditions (but see Agmon and Connors 1992), but repetitive bursting in deep L5 PNs is an important factor associated with the initiation of cortical seizures (Connors 1984; Chagnac-Amitai and Connors 1989; Pinto et al. 2005; Traub et al. 2005). We therefore tested the effect of blocking Kv2 channels on onset and repetitive firing in response to long current steps.

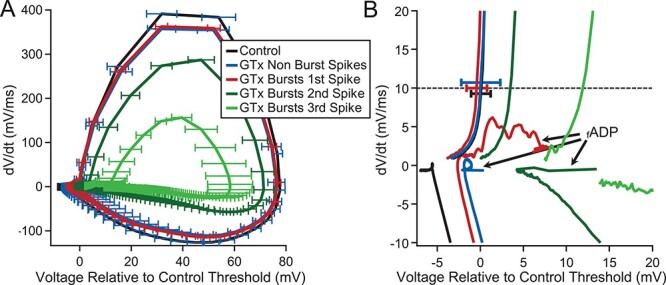

A majority of Thy1 PNs respond to DC current steps in control solution with an initial spike doublet or burst at the step onset that is followed by repetitive firing that does not adapt (e.g., Fig. 6A, black trace). As previously noted for motor cortex, most Thy1 PNs show an increase in firing rate with time during DC steps (38 of 44 neurons in this study; this is referred to as warm-up firing: Miller et al. 2008). Figure 6A shows the typical effect of GTx on AP firing during long DC steps. GTx converted the initial AP doublet into a multispike burst riding on an enhanced fADP (i.e., an onset burst). In addition, GTx converted the sustained regular firing pattern evoked by a current step in this cell into repetitive bursts, with the interburst interval set by the duration of an enhanced mAHP (see Fig. 8).

We quantified the effect of blocking Kv2 channels on onset firing by comparing the firing (spike) rate for the first three interspike intervals (ISIs) before and after GTx. This allowed us to test for the presence of onset singlet, doublet, or burst firing (APs within a burst or doublets are indicated by much higher spike rates (Hz: determined as 1/ISI) than subsequent APs: Fig. 6B,C). Under control conditions, the firing rate for the first ISI was higher at the onset of all current steps above 400 pA, indicating that it is normal for Thy1 neurons to fire with an initial doublet (see also Guan et al. 2018). In GTx, firing rates for all three ISIs were higher (the instantaneous frequencies increased Fig. 6B,C) at all current intensities. In addition, at the lowest current steps, GTx converted onset single spiking to doublets and at 600 pA or greater, doublets into ≥3-spike bursts. Figure 6D summarizes the distribution of onset APs into singlets, doublets, or bursts in control bath and in GTx. After application of GTx, most Thy1 neurons had an initial three-spike burst (especially for larger current steps, not shown). These data highlight the important role of Kv2 channels in regulating the onset burst firing pattern. It should be noted that bursting in PNs can be enhanced at lower extracellular calcium concentrations both in the slice and in vivo (Su et al. 2001; Boucetta et al. 2013). Our slice experiments were performed using extracellular calcium concentration (2 mM) that may be higher than those estimated in cerebrospinal fluid (1.1–1.5 mM: Jones and Keep 1988; Massimini and Amzica 2001; Crochet et al. 2005; Forsberg et al. 2019). Thus, it is possible that our ex vivo measurements might underestimate the role of Kv2 in controlling bursting in vivo.

Repetitive bursting was identified by visual inspection as the presence of two or more bursts during a current step (i.e., at least one burst after the onset burst). GTx caused repetitive bursting for at least one level of DC current injection in ~40% of Thy1 PNs (20 of 51 cells). We also tested the firing of 15 etv1 PNs in response to GTx, as an example of an L5 IT-type PN (Groh et al. 2010; Guan et al. 2013; Bishop et al. 2015) (data not shown). In contrast to the ET-type Thy1 PNs, etv1 PNs rarely showed repetitive bursting after Kv2 block. While all of the cells were able to fire with an initial doublet in response to higher current injections (cf. Guan et al. 2018), none of the 15 etv1 cells fired with onset or repetitive bursts in control solution. In GTx, only 3 of 15 cells fired with an onset burst (20%) and none of them fired with repetitive bursts.

During constant current steps, GTx-induced repetitive bursting typically only lasted for the first half second of the step and then firing returned to a regular pattern. Plots of firing frequency at the end of long current steps (i.e., when there was no bursting: from 2 s to 3 s after stimulus onset) versus mean injected current (F-I relationship) showed that GTx caused very little change in firing rate to any current (Fig. 6E). This was also true when the F-I relationship was analyzed for the time interval 500–1000 ms after stimulus onset (data not shown). The lack of effect of GTx on the F-I relation in Thy1 neurons contrasts with the decrease in firing rate caused by GTx previously reported as the dominant effect in CA1 (Du et al. 2000; Liu and Bean 2014), entorhinal cortex (Hönigsperger et al. 2017), and rat neocortical PNs from layers 2–3 and 5 (Guan et al. 2013). This decrease in firing rate was attributed to accumulated inactivation of voltage-dependent sodium channels secondary to depolarized interspike membrane voltage trajectories after block of Kv2 and suggests that Kv2 expression may be permissive for high rates of firing in PNs. The lack of a preferential decrease in firing to large stimuli after GTx in Thy1 PNs is consistent with the hyperpolarized activation range for Kv2 channels in these cells making them available at all rates of firing. The overall lack of a significant effect of GTx on firing rate is consistent with inactivation of Na+ channels not being a limiting factor for firing rate in Thy1 PNs. As a test of this, we used stimuli including rapid current fluctuations that remove sodium channel inactivation and found that firing rates were insignificantly affected compared with DC steps in Thy1 PNs under control conditions (Fig. 6E). The level of noise used in this example (see legend for Fig. 6E) induced an onset burst in the presence of GTx for all four cells tested (compared with none in control solution). Further, GTx had little effect on firing to noisy stimuli that did not cause repetitive bursting (2 mV SD noise response at RMP in Fig. 6E).

To rule out that repetitive bursting might have resulted from a partial block of Kv4-type channels by GTx, we tested the effect of the selective Kv4 blocker AmmTx3 (200 nM) on firing during 1.5 s long depolarizing current steps. No cells showed burst firing in control solutions for this sample of 13 Thy1 PNs. In the presence of AmmTx3, we only observed an onset burst in 2/13 (15%) of Thy1 PNs (the initial doublet firing was converted to a three-spike initial burst) and none of these cells showed repetitive bursting. Thus, the Kv2 current that is normally activated during firing is sufficient to suppress onset bursting and prevent repetitive bursting in Thy1 neurons, even when Kv4 channels are blocked. Similarly, repetitive firing was tested in 20 cells before and in the presence of the selective Kv1 channel blocker 100 nM α-dendrotoxin (DTx). In control solution, 19 of 20 cells (95%) fired with an initial doublet followed by regular spiking (the remaining cell had an onset burst). In the presence of DTx, doublets were obtained in all cells with smaller stimuli and six cells (30%) showed an initial onset burst (no cells showed repetitive bursting). Thus, the block of Kv2 channels had a much more powerful effect on burst firing in Thy1 PNs compared with block of Kv1 or Kv4 channels.

Repetitive Bursting Alters AP Firing Resonance to Low-Frequency Inputs

In order to determine the role of Kv2 channels in the regulation of bursting during more natural patterns of input, we evoked repetitive firing in response to current steps composed of a DC level with added noisy current fluctuations (as used in Fig. 6E). The filtered noise has statistics similar to synaptic current fluctuations arriving at the soma of neocortical PNs, as previously measured from in vivo recordings in awake behaving animals (Pare et al. 1998). In previous work, we determined that layer 2/3 neocortical pyramidal neurons that fire with a regular spiking pattern to DC input will exhibit repetitive doublet firing when driven with rapid and large amplitude current fluctuations (we previously termed this “conditional bursting”: Higgs and Spain 2011). Low-amplitude input fluctuations make the ISIs irregular but do not cause this repetitive doublet firing. Since we wanted to test the role of Kv2 channels in suppressing repetitive, multispike bursting during these more naturalistic fluctuating inputs, we first kept the amplitude of the fluctuations low (noise response at RMP = 2 mV SD) so as to prevent “conditional bursting” under control conditions.

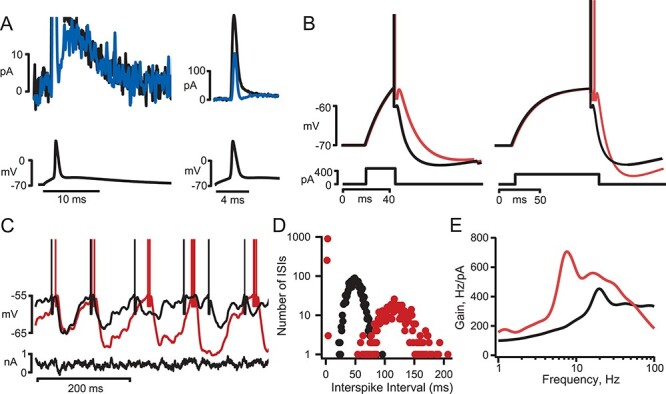

In control solution, repetitive bursts were never seen in neurons driven with the low amplitude of noise we employed. In contrast, block of Kv2 channels with GTx resulted in repetitive bursting to noisy stimuli in 47% of Thy1 neurons (8 of 17 cells). Figure 7A shows a typical trace of a Thy1 PN in which GTx resulted in repetitive bursting during the naturalistic (noisy) current injection. Note that unlike the response to DC steps without noise (where repetitive bursting only lasted for the first few hundred milliseconds of the current step), the bursts in response to noisy stimuli persisted throughout the 10-s stimulus (Fig. 7A,B). Injecting higher amplitude noise (noise that caused 6 mV SD at RMP) in control conditions was capable of driving repetitive doublets (not bursts), and GTx application increased the occurrence of both repetitive doublets and bursts (data not shown). As previously noted, following each burst, there was an enhanced mAHP that limited and regularized the rate of repetitive bursting (quantified in Fig. 8B). Thus, Kv2 channels normally suppress sustained repetitive bursting during natural patterns of somatic current input.

We previously showed for layer 2/3 PNs (Higgs and Spain 2009) that the relative efficacy of the various frequency components of a noisy stimulus to modulate firing rate can be calculated and represented as a gain–frequency relation and we refer to the frequency components that most robustly modulate AP firing as the suprathreshold resonance frequency. We employed this strategy to calculate the suprathreshold resonance of Thy1 neurons under control and GTx conditions, while keeping the mean firing rate constant at ~20 Hz (a midrange firing rate during activity of PNs in motor cortex) by adjusting the DC level of the current steps while maintaining a constant standard deviation of the amplitude of the noisy component of the current (Fig. 7).

Figure 7C (black circles) shows that in control solutions, ISIs in Thy1 PNs were distributed with a single peak at ~50 ms (20 Hz) with short ISIs related to doublets or bursts rarely occurring. In regular spiking neurons, the frequency components of the input current that most strongly drive AP output are typically matched to the mean firing frequency of the neuron. Thus, when driving the neurons to a mean firing rate of 20 Hz under control conditions, we unsurprisingly observed a maximal gain centered at 20 Hz (Fig. 7D). As we have described previously in other PNs, Thy1 neurons also exhibit another peak in the gain–frequency relation at much higher frequency (~300 Hz) that results from high-pass filtering caused by AP threshold accommodation (Higgs and Spain 2011).

Blocking Kv2 channels had two main effects that depended on whether GTx caused a substantial amount of repetitive bursting or a more uniform shift in the distribution of ISIs during the noise plus DC-induced firing (Fig. 7E vs. G). In PNs where the block of Kv2 channels resulted in sustained repetitive bursting (Fig. 7E), the distribution of ISIs has two peaks with a subset of very short ISIs and an increase in the number of very long ISIs (Fig. 7E inset). In these cells, the magnitude of the peak gain increased in GTx and peak gain frequency (or suprathreshold resonance frequency) shifted to a frequency less than the mean firing rate (Fig. 7F; from 21.45 to 12.7 Hz, n = 9, P < 0.0002). Thus, Kv2 normally prevents the entrainment of firing to low-frequency inputs (of ~10 Hz) that result from repetitive bursting.

For the subset of neurons where GTx did not cause substantial repetitive bursting (as determined by visual inspection and a lack of a clear peak or shoulder at short intervals in the ISI histogram; Fig. 7G,H), there was no significant change in the amplitude of the peak gain or the frequency at which peak gain occurred (n = 8). Rather, there was broadening of the sensitivity to input frequencies around the peak of gain versus frequency. Thus, block of Kv2 channels enhances the sensitivity of all Thy1 PNs to low-frequency inputs and in a subset of cells, the transition to repetitive burst firing enhances the efficacy of input currents with frequency components well below the mean firing rate of the cell.

Repetitive Bursting Results in Firing Resonance to Theta Input Frequencies

The repetitive bursting group of PNs in Figure 7E,F includes neurons that had 12–52% of APs contained in bursts during 10-s noisy current steps. In order to gain insight into how repetitive bursting results and suprathreshold resonance is caused by the block of Kv2 channels, we further analyzed a subset of Thy1 PNs in which GTx application resulted in greater than 40% of the APs being contained in bursts during the noisy current injection (four neurons from the group of busters in Fig. 7E met this criterion). We first analyzed if there were particular input current waveforms that favored bursting by comparing the STA of the input current for 1) all APs in control solution, 2) isolated APs in GTx, and 3) the first AP in a burst (Fig. 8A). This analysis revealed that the peak current immediately prior to threshold was the same in all cases. In control, DC current was required to drive the neuron to fire at 20 Hz. In GTx, less DC current was required, and the average current trajectory had shorter rise-times prior to APs. This likely resulted from an increase in accumulated Na+ channel inactivation that occurred during firing when Kv2 channels were blocked. Thus, a faster rising stimulus was required on average to activate sufficient Na+ current to evoke an AP. Further, comparison of the average current trajectory in GTx leading to isolated APs or the first AP in a burst had similar rise-times but the average input current waveform that drove bursts had a prolonged depolarizing-current hump following the onset of the initial spike in a burst (positive current hump indicated by arrow in Fig. 8A). The hump was absent in the STA for isolated APs. Note that although the noisy stimulus had the same statistics in GTx and control solution, normally the fADP is sufficiently blunted by Kv2 conductance so that slow current envelopes do not drive repetitive bursting. This suggests that reduction of Kv2 current would make neurons more susceptible to bursting when driven by synaptic inputs that contain a slow component (e.g., from NMDA receptor activation).

Prior work has shown that Ca2+ entry during the AP leads to activation of SK-type potassium channels and that this conductance contributes to the mAHP, a major factor controlling the refractory period between APs (Schwindt et al. 1988; Lorenzon and Foehring 1993; Pineda et al. 1998; Guan et al. 2015). Each epoch of a multispike burst greatly enhances the Ca2+-dependent mAHP, which in turn controls the interburst interval (see also Huang et al. 2018). We used the same four champion bursters to quantify the amplitude of the mAHP following a burst compared with following isolated APs in GTx (Fig. 8B) and found a significantly enhanced mAHP following bursts. Thus, repetitive bursting would be expected to occur at regular intervals (on average) as determined by an enhanced mAHP that dominates refractoriness.