Abstract

Nearly 200 million people have been diagnosed with COVID-19 since the outbreak in 2019, and this disease has claimed more than 5 million lives worldwide. Currently, researchers are focusing on vaccine development and the search for an effective strategy to control the infection source. This work designed a detection platform based on Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) by introducing acetonitrile and calcium ions into the silver nanoparticle reinforced substrate system to realize the rapid detection of novel coronavirus. Acetonitrile may amplify the calcium-induced hot spots of silver nanoparticles and significantly enhanced the stability of silver nanoparticles. It also elicited highly sensitive SERS signals of the virus. This approach allowed us to capture the characteristic SERS signals of SARS-CoV-2, Human Adenovirus 3, and H1N1 influenza virus molecules at a concentration of 100 copies/test (PFU/test) with upstanding reproduction and signal-to-noise ratio. Machine learning recognition technology was employed to qualitatively distinguish the three virus molecules with 1000 groups of spectra of each virus. Acetonitrile is a potent internal marker in regulating the signal intensity of virus molecules in saliva and serum. Thus, we used the SERS peak intensity to quantify the virus content in saliva and serum. The results demonstrated a satisfactory linear relationship between peak intensity and protein concentration. Collectively, this rapid detection method has a broad application prospect in clinical diagnosis of viruses, management of emergent viral infectious diseases, and exploration of the interaction between viruses and host cells.

Keywords: Surface-enhanced raman spectroscopy, SARS-CoV-2, Human adenovirus, Influenza virus, Detection method

1. Introduction

Viruses are minute noncellular microorganisms with the simplest structure, existing widely in nature, and a leading cause of biological death [1]. Besides, it is inadvertently known that viruses mutate frequently [2]. The first 20 years of this century have seen an unprecedented rise in the outbreak or epidemic of numerous viral diseases, including SARS [3], H1N1 [4], MERS [5], Ebola hemorrhagic fever [6], and COVID-19 [7] across the globe. The current COVID-19 epidemic has infected more than 200 million people worldwide and claimed more than 5 million lives [8]. The novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) is a single-stranded RNA virus containing 29 coding proteins [9]. Although researchers have uncovered four crucial structural proteins of the virus, there is a paucity of information regarding the effective treatment approach of the virus [10], [11].

Early detection and identification of viruses are of great value for preventing and treating viral infectious diseases. The presently available detection technologies for viruses are mainly based on molecular and serological techniques. The former primarily involves the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and its derivative technology [12], while the latter integrates fluorescence antibody detection [13], Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) [14], etc. However, the application of most of these techniques is limited due to complex operation, high cost, and low sensitivity. For SARS-CoV-2, fluorescence quantitative PCR is the most commonly employed detection method. While this approach has a detection sensitivity of 500–1000 copies/test [15], incorrect sampling timing may yield false-negative cases, such as when the virus has been cleared from the upper respiratory tract [16]. In addition, the application of fluorescence quantitative PCR technology is time-consuming because it requires prior processing of specimens and data analysis after detection. The sample is also susceptible to contamination, and this may result in false positives [17]. In China, the most commonly used serological method is ELISA and chemiluminescence, but they also have false positives due to cross-reactions. For instance, in some cases, seasonal coronaviruses can cross-react with SARS-CoV-2 [18] and cause misdiagnosis of the pathogen [19]. Moreover, the use of PCR and serological detection of emerging infectious diseases of unknown pathogens are solely based on the specific molecular probe of the virus, such as antibodies or DNA Oligomers. So, the development of a rapid, simple, and cost-effective virus detection technology for early identification of viral infection would allow for early clinical intervention and improve the survival of patients.

Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS), a non-destructive and rapid detection technology, has strong detection capability for DNA, protein, and other biological molecules at the single-molecule level. This approach demonstrates high sensitivity and does not require complex pretreatment of samples [20], [21]. As the most basic substance of life, water lacks fluorescent signals and would not interfere with SERS signals. Therefore, SERS technology can far much be applied in the field of life science, including detection of several respiratory viruses, such as human adenovirus type 5 [22], influenza virus [23]. Generally, the hot spot of SERS technology is less than 10 nm space between the gold or silver nanostructures [21], and the size of the virus is nearly 100 nm. In this view, the virus cannot adapt to the hot spot of SERS. The simplicity with the use of traditional SERS technology is unreliable in the detection and identification of the virus. Xingang Zhang et al. [22] developed a novel NNHCMB substrate, which can accurately detect adenovirus with good reproducibility. However, the preparation process of NNHCMB substrate is complicated and not cost-effective. Elsewhere, urchin gold nanoparticle developed by Eom et al. [23] could specifically bind to the sulfhydryl structure of the oseltamivir-resistant influenza virus variant strain and detect the mutant strain at the single molecular level. Although their method demonstrated high sensitivity, it was inferior in generality and could only detect the virus strain with the sulfhydryl group in the structure. Jae-young Lim et al. [24] used SERS technology to detect proteins expressed on the surface of the influenza virus-infected cells. They also explored the infection status of potent influenza mutant strains. However, the method could not pick up the fingerprint of the virus. Instead, it was detected indirectly through the protein expressed after the virus-infected cells, but the fingerprint signal of the protein was easily affected by the inherent protein on the cell surface, resulting in poor accuracy. Therefore, it would be imperative to develop SERS virus detection approaches with high-level accuracy, sensitivity, universality, repeatability, low cost, easy to operate, and free from interference from background fluorescence such as serum or saliva.

Here, we designed a new SERS detection platform, using traditional citrate to reduce silver nanoparticles, and added acetonitrile solvent to form an excellent hot spot suitable for viruses by aggregating calcium ions, and exploring the human adenovirus, SARS-CoV-2 without difference and marker. In addition, combined with machine learning, rapid diagnosis of viruses under low detection limits (100 PFU/test) was attempted within 1 to 2 min. At the same time, use the two mutual solvent acetonitrile characteristics, not only can be used as an excellent internal standard to assess virus content, and to improve the stability of the base has a good preparation by effective (four months) in rapid, precise detection of virus infection, this method possesses broad application prospects, will help new crown worldwide epidemic control.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Preparation of SARS-CoV-2

The inactivated SARS-CoV-2 was purchased from the Henan Key Laboratory of Immunology and Targeted Drugs, School of Laboratory Medicine, Xinxiang Medical University. It was incubated at 37℃ for 13 days after adding 4% paraformaldehyde. When the inactivated SARS-CoV-2 was received, it was immediately sub-packed (20 μL / tube) and stored at 4 ℃.

2.2. Preparation of HAdV

A549 cells were provided by Department of Hygienic Microbiology, Public Health College, Harbin Medical University. A549 cells were cultured with RPMI-1640 (Hyclone, SH30809.01) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, 10099133C) and 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin Solution (Gibco, 15140148). A549 cells in T75 culture bottle were infected with viral suspension, and then incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2. When the cytopathic effect reached 85%, freeze and thaw the cell lysate between 37℃ and dry ice for three times. Centrifuge the cell lysate at 4℃, 3000 rpm for 10 min. Transfer and filter the supernatant through a 0.45 μm filter unit. The filtered supernatant is ready for virus purification. ViraTrapTM Adenovirus Purification Miniprep Kit (Biomega, V1160) was used to purify the virus. After get the purified HAdV, we calculate TCID50 by Reed-Muench method to obtain virus titer (PFU/mL). Finally, we use 2% β-propiolactone to inactivate the virus, and adjust the pH to 7.3–7.4 with 7% NaHCO3.

2.3. Preparation of H1N1 influenza virus

Vero cells were provided by Department of Hygienic Microbiology, Public Health College, Harbin Medical University. Vero cells were cultured with Dulbecco's modification of Eagle's medium Dulbecco, DMEM (Gibco, C11995500BT) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, 10099133C) and 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin Solution (Gibco, 15140148). Vero cells in T75 culture bottle were infected with viral suspension, and then incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2. When the cytopathic effect reached 85%, freeze and thaw the cell lysate between 37℃ and dry ice for three times. Centrifuge the cell lysate at 4℃, 3000 rpm for 10 min. Transfer and filter the supernatant through a 0.45 μm filter unit. The filtered supernatant is ready for determinate the titer. We calculate TCID50 by Reed-Muench method to obtain virus titer (PFU/mL). Finally, we use 2% β-propiolactone to inactivate the virus, and adjust the pH to 7.3–7.4 with 7% NaHCO3.

2.4. Detection methods in PBS buffer

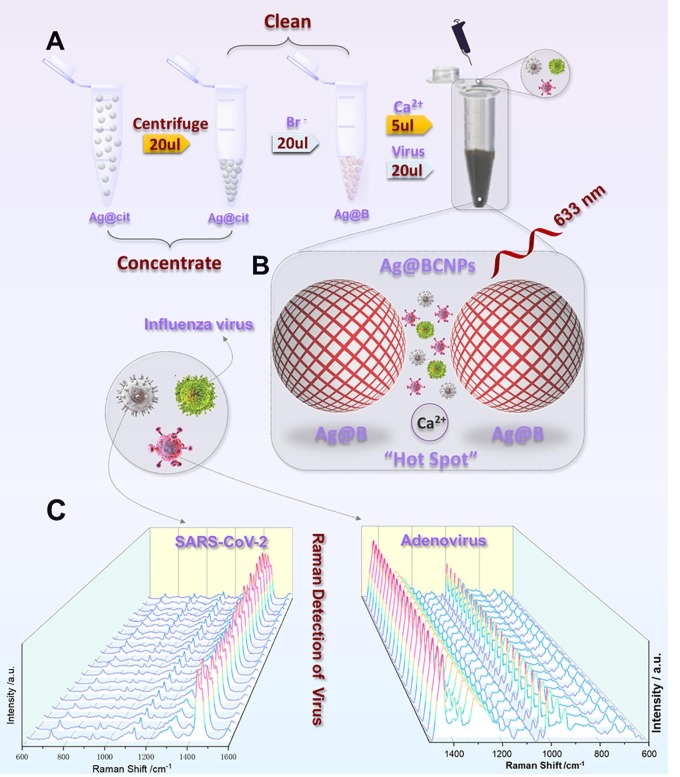

The experimental process is shown in Fig. 1 A and B. The preparation of Ag@BCNPs (silver nanoparticles modified by bromide ion, and added with acetonitrile and calcium ions) is the same as the previous work of our research group [25], and is slightly modified on its basis. The Ag@BCNPs were produced by adding 6 mL 1% sodium citrate into a slightly boiling silver nitrate solution (0.034 g/200 mL) at 96℃. After that, 5 mL of sodium citrate-reduced silver sol was centrifuged (6500 rpm, 20 min, 20° C), after the removal of the supernatant, 20 μL of the centrifuged silver sol was mixed with 20 μL of bromide ion (1 mM) at room temperature for 60 min. Then, add 3 μL of acetonitrile to the mixture and the mixture was further mixed with 20 μL sample and 5 μL of Ca2+ (0.01 M CaCl2·2H2O). After that, the mixture was shaken well for SERS detection. The SERS test instrument is made by WITec alpha 300R. (Germany). The laser wavelength is 633 nm, the scan time is 35 s, the laser power is 28mW, and each test is accumulated once.

Fig. 1.

(A) shows the schematic diagram of the preparation of silver enhanced substrate and virus detection using the SERS method. Ag@cit: Silver nanoparticles obtained by reduction of citrate; Ag@B: Silver nanoparticles modified by bromide ion; Ag@BCNPs: Ag@B with acetonitrile and calcium ions added. (B) shows the conceptual schematic diagram of the relationship between the virus sample and the “hot spots” generated by the silver enhanced substrate. (C) show the SERS spectra obtained by random 20 groups of SARS-CoV-2 (104 PUF/test) and HAdV (105copies/test) samples under the current method (Ag@BCNPs), respectively.

2.5. Detection methods in saliva and serum

The virus particles were added to fetal bovine serum (or artificial saliva) at the desired titer, and the fetal bovine serum (or artificial saliva) was used as the solvent, and the concentration was diluted from high to low. Then, 20 μL of the centrifuged silver sol was mixed with 20 μL of bromide ion (1 mM) at room temperature for 60 min. Then, add 3 μL of acetonitrile to the mixture and the mixture was further mixed with 20 μL sample and 5 μL of Ca2+ (0.01 M CaCl2·2H2O). The other test conditions are the same as those of antibiotics in PBS buffer.

2.6. Machine‑Learning method based on PCA

A total of 1200 Raman shifts from 750 to 1750 cm−1 were chosen as the variables for PCA (Principal Component Analysis) by using Python and Statistical Product and Ser‑vice Solutions. The built‑in “PCA” function was used to get principal component coefficients, principal component scores, and principal component variances. The first three principal components were acquired with F1 interpreting 96.8% of variances, F2 interpreting 3% of variances and F3 interpreting 0.1% of variances. The top two principal components contributed to 99.8% of cumulative contribution which was enough to distinguish the data. This means that 99.8% of the original spectral information is represented in two-dimensional space. The eigenvector of covariance matrix is used to load and compare the Raman spectrum data of multiple groups of samples. Raman spectra are projected onto the score map in proportion to the load. Use the “error ellipse” function to draw the error ellipse with 95% confidence. The main differences of virus Raman spectra were obtained by PCA, and then the data obtained by principal component analysis were classified. The results showed that the virus could be identified by PCA.

3. Results and discussion

The study of the biological activity of SARS-CoV-2 can easily introduce the virus to the environment, and there is no specific therapeutic drug to manage SARS-CoV-2 infection. As such, a model virus is needed to replace the active SARS-CoV-2 with both universalities. Human adenovirus (HAdV) is an unenveloped double-stranded DNA virus with a wide range of hosts [26] and a wide range of tissue tropism. This virus can cause acute adenovirus pneumonia [27], acute gastroenteritis [28], eye keratitis [29], and other diseases. Meanwhile, because HAdV is characterized by weak pathogenicity and mild clinical symptoms after infection, it can serve as an appropriate model organism for virology research. In this work, we designed a novel detection method based on HAdV, which can be employed to detect various viruses, including HAdV, SARS-CoV-2, and influenza virus. The method described here allows for rapid, sensitive, and simple detection.

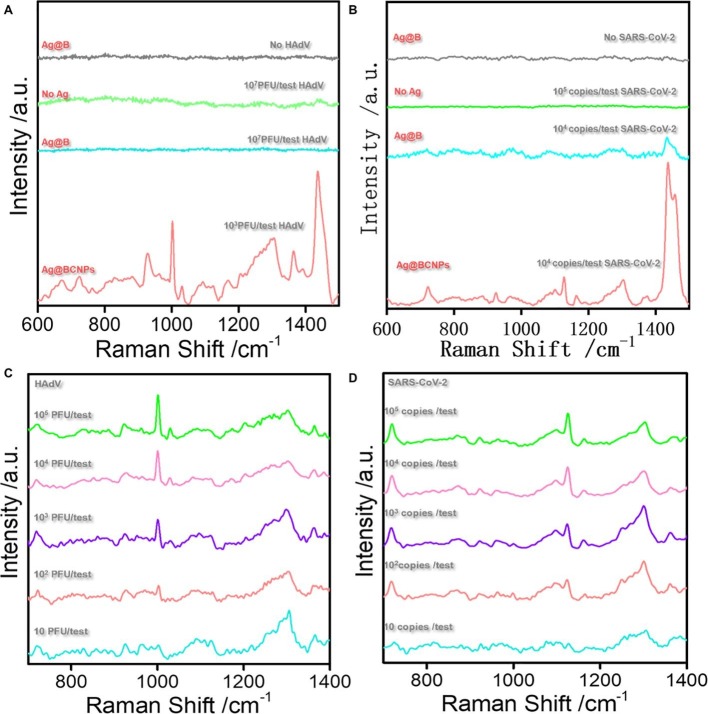

In the recent past, the main bottleneck of direct unlabeled detection of viruses using SERS technology was that the viruses could not enter the hot spots, which resulted in poor detection accuracy and low sensitivity [22] . Meanwhile, background fluorescence such as saliva, serum could easily compromise the SERS results. In Fig. 2 A, the green line shows the Raman spectrum of HAdV at 107 PFU/test, without the presence of a viral signal, while the blue line depicts the presence of a weak virus signal following the addition of iodide-modified silver nanoparticles, but this does not discriminate the virus signal from the impurity signal. To address the problem of impurity signal and obtain high quality virus signal, we selected calcium ion as the aggregator because it can form a stable complex with citrate, so that most of the citrate leave the surface of the silver nanoparticles and avoid the influence of SERS signal of citrate on virus detection (Fig. S1) [30]. Moreover, the positive charge on calcium ions can enhance the electromagnetic field of the silver nanoparticle enforcement system and induce the nanoparticles to gather and form hot spots, thus achieving the purpose of enhancing the Raman signal of the virus [31]. In addition, when acetonitrile is added to the enforced substrate, because acetonitrile is mutually soluble with water, it can be evenly dispersed in the system and enhance the stability of the enhanced substrate. Fig. S2 outlines a fingerprint of HAdV obtained with the current method on an enhanced substrate prepared over a period equal to four months, with the observed enhanced signal remaining very clear. At the same time, there was no significant change in virus signal compared with freshly prepared enhanced substrate. The red line represents the SERS map of HAdV obtained with calcium ion as an aggregator (Fig. 2A). The signal peaks of the protein structure (1000 cm−1) and nucleic acid structure (722 cm−1) in the spectrum are noticeable (the specific peak attribution is in SI). With the same method, we observed the SERS characteristic map of SARS-CoV-2 (Fig. 2B). Fig. S3 shows the TEM of silver nanoparticles, and the aggregation is stable and uniform, and Fig. S4 shows the zeta potential measurement of Ag@B. and Ag@BCNPs. The 20 groups of random SERS maps of HAdV and SARS-CoV-2 obtained at different time intervals are depicted in Fig. 1C, and the generated spectra show high reproducibility and sensitivity. Of note, at the minimum detection concentration of 100 PFU/test (copies/test), the characteristic structures of HAdV (Fig. 2C) and SARS-CoV-2 (Fig. 2D) were well outlined.

Fig. 2.

(A): SERS spectra of HAdV in different systems. SERS spectrum of Ag@B without virus (gray line); Raman spectrum of 107 PUF /test HAdV sample in PBS (green line); SERS spectrum of 107 PUF /test HAdV in silver nanoparticles (blue line); SERS spectrum 103 PUF /test HAdV (brick red line) obtained under the current method (Ag@BCNPs). (B): SERS spectra of SARS-CoV-2 in different systems. SERS spectrum of Ag@B without virus (gray line); Raman spectrum of 105 copies /test SARS-CoV-2 sample in PBS (green line); SERS spectrum of 104 copies /test SARS-CoV-2 in silver nanoparticles (blue line); SERS spectrum 104 copies /test SARS-CoV-2 (brick red line) obtained under the current method (Ag@BCNPs). (C) and (D) respectively show SERS spectra of HAdV and SARS-CoV-2 at different concentrations.

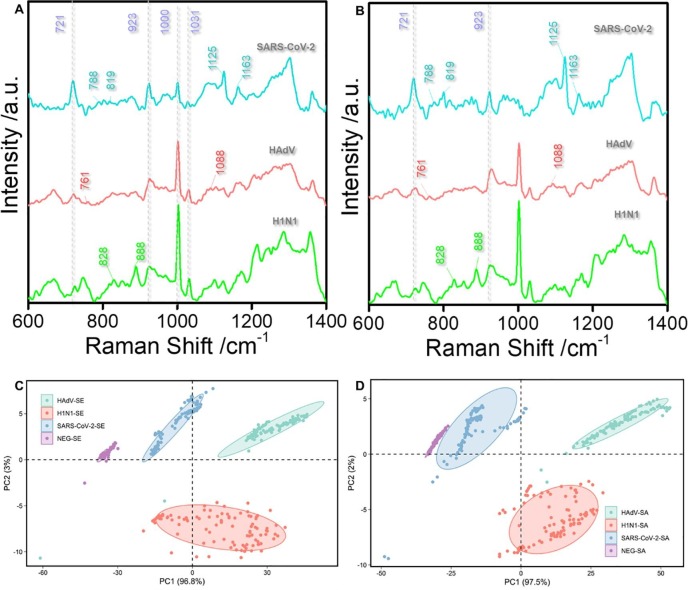

Furthermore, we obtained the Raman spectra of HAdV, SARS-CoV-2, and H1N1 influenza viruses in serum (Fig. 3 A) and saliva (Fig. 3B) via SERS detection. The results under these conditions corroborated with those in the PBS buffer and supported the view that our method is viable for rapid diagnosis and detection of the virus in the biological background. Through comparison of the SERS spectra of the three virus types, the differences in the position of their characteristic peaks were as follows: the characteristic peaks of SARS-CoV-2 (blue line) were in the range of 788–819 cm−1 and 1125–1163 cm−1; the characteristic peaks of HAdV (red line) were within the range of 761–881 cm−1 and 1088–1123 cm−1; the characteristic peak of the H1N1 influenza virus (green line) were in the range of 828–888 cm−1. We also performed principal component analysis (PCA) of the 1000 sets of profiles of each virus molecule in serum (Fig. 3C) and saliva (Fig. 3D) under the current experimental conditions. Of note, the three viruses could easily be distinguished in the biological background based on the changes in the position of characteristic peaks and the intensity of common peaks. The characteristic peak signal of the Raman spectrum was extracted from the noise through PCA analysis. We then applied PCA to the Raman spectrum of serum and saliva with PBS buffer without virus as the control and implemented multiple Raman spectrum analyses on the three viruses. Eventually, the PCA process generated multiple points with different coordinate values on PC1 and PC2. The multiple projection points of each cell were surrounded by a clear 95% confidence ellipse, which did not overlap in each case. The results suggest that, aside from detecting a virus in serum and saliva, the PCA approach can also identify which virus has caused the infection. The mean figure showed that the characteristic peaks of the three viruses in saliva (Fig. S5A) and serum (Fig. S5B) were entirely in support of those in PBS buffer (Fig. S5C). The results of LDA analysis (Fig. S5D-F) were also consistent with those of PCA analysis, which further proved the reliability of the method.

Fig. 3.

(A): SERS spectra of three viruses (SARS-CoV-2, HAdV, H1N1) in serum. (B): SERS spectra of three viruses (SARS-CoV-2, HAdV, H1N1) in saliva. (C): The main characteristics of SERS spectrum were classified by PCA on serum containing COVID-19, HAdV and H1N1 virus respectively. (D): The main characteristics of SERS spectra were classified by PCA on saliva containing COVID-19, HAdV and H1N1 virus respectively.

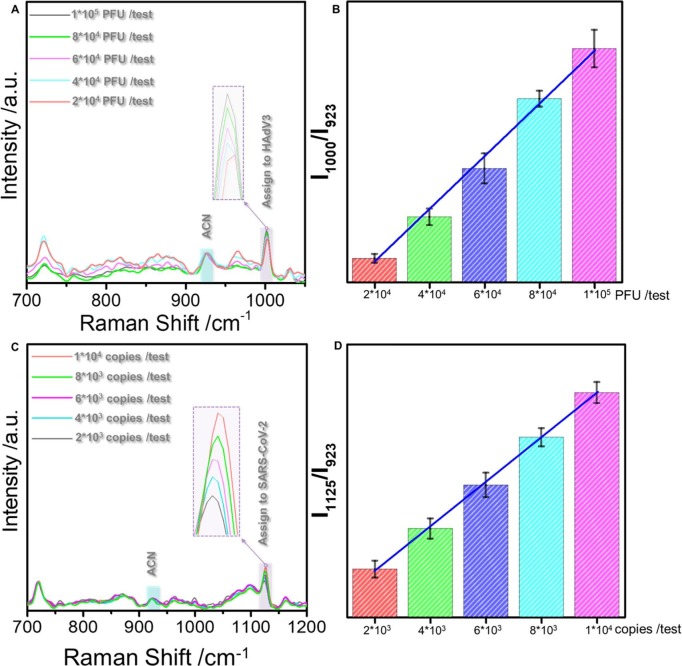

Moreover, we investigated the correlation between the variation of virus titer and the Raman peak intensity further to validate the stability and reproducibility of this method. Fig. 4 shows the concentration-dependent SERS spectrum lines of HAdV in PBS buffer (4A) and SARS-CoV-2 in saliva (4C), respectively. We observed a gradual increase in the intensity of characteristic peak intensity with the rise in virus titer, with using the peak position of 1125 cm−1 in SARS-CoV-2 and the peak position of 1000 cm−1 in HAdV, we evaluated the effect of virus concentration change on peak intensity, demonstrating an incredible linear relationship. The error bar threshold was far less than the threshold required to distinguish different concentrations. These data proved that our method is reliable and stable in the quantitative identification of viruses. Further quantitative analysis of HAdV in saliva (Fig. S7) also demonstrated an upstanding linear relationship between peak intensity and concentration. Taken together, these findings provide convincing evidence that our method can be used to quantify virus samples in saliva and is expected to have an essential prospect in clinical application.

Fig. 4.

(A): SERS spectra obtained for HAdV at different concentrations (2*104-1*105PUF /test). (B): The bar graph of the value of I1000/I923 corresponding to the change in HAdV concentration. (C): SERS spectra obtained for SARS-CoV-2 at different concentrations (2*103-1*104 copies /test). (D): The bar graph of the value of I1125/I923 corresponding to the change in SARS-CoV-2 concentration.

4. Conclusions

This work presents a novel unlabeled virus detection method that utilizes calcium ions as aggregators, citrate ions are removed from the surface of silver nanoparticles, and acetonitrile is added to ensure the formation of high-quality hot spots. This method in the guarantee under the premise of direct detection of virus particles won the high signal-to-noise ratio and good reproducibility, used the virus of SERS signal has higher sensitivity. With acetonitrile as an internal standard, the present study explores the dropping degree of virus (concentration), the linear relationship between the changes identified in saliva and serum under the background of reliability, but without the interference of background fluorescence. Three highlights of our method include: (1) the real signal for detection of the virion can be obtained. Also, the linear relationship between the variation of the virus concentration in the salivary background can be examined; (2) the lower limit of virus detection is nearly 100 copies/test (PFU/ test); (3) the enhanced substrate prepared with this method has good stability and can maintain upstanding viral molecule-enhanced Raman signal within four months. This method can be used to diagnose of the simulate clinical infected specimens, and has a potential application prospect in epidemic management. It may promote the application of SER technology in virus detection and improve emergency response capacity. The ability to deal with newly emerging virulent infectious diseases and to help analyze the interactions between the virus and host cells is our new research direction.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the Introduce high-level talent incentive project (No. 0103-31021200052)

Footnotes

A detailed description of the experimental method; TEM spectra of the Ag@B and Ag@B with calcium ions and acetonitrile; the zeta potential measurement of Ag@B and Ag@BCNPs; the ANOMD and the LDA results of SARS-CoV-2, H1N1, HAdV and blank control group in different systems; the results of standard test method for virus detection; the Raman peak assign to virus; supplement of SERS spectra. Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2022.135589.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Suttle C.A. Viruses in the sea. Nature. 2005;437:356–361. doi: 10.1038/nature04160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hie Brian, Zhong Ellen D, Berger Bonnie et al. Learning the language of viral evolution and escape. Science, 371(2021)284-288. 10.1126/science.abd7331. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Marra Marco A., Jones Steven J.M., Astell Caroline R., et al. The Genome sequence of the SARS-associated coronavirus. Science. 2003;300:1399–1404. doi: 10.1126/science.1085953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Listed N. Swine influenza: how much of a global threat? Lancet. 2009;373:1495. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(09)60826-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zaki Ali M, van Boheemen Sander, Bestebroer Theo M et al. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia.N Engl J Med, 367(2012)1814-20. 10.1056/nejmoa1211721. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Baize Sylvain, Pannetier Delphine, Oestereich Lisa et al. Emergence of Zaire Ebola virus disease in Guinea.N Engl J Med, 371(2014)1418-25. 10.1056/nejmoa1404505. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Zhu Na, Zhang Dingyu, Wang Wenling et al. A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019.N Engl J Med, 382(2020)727-733. 10.1056/nejmoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard, update at 5:21pm CET, 3 November 2021, https://covid19.who.int/.

- 9.Bukkitgar Shikandar D, Shetti Nagaraj P, Aminabhavi Tejraj M. Electrochemical investigations for COVID-19 detection-A comparison with other viral detection methods.Chem Eng J, 420 (2021)127575. 10.1016/j.cej.2020.127575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Markus H., Hannah K.-W., Simon S., et al. SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry Depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and Is Blocked by a Clinically Proven Protease Inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181:271–280.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu Roujian, Zhao Xiang, Li Juan et al. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet, 395(2020)565-574. 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30251-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Elnifro E.M., Ashshi A.M., Cooper R.J., et al. Multiplex PCR: optimization and application in diagnostic virology. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2000;13:559–570. doi: 10.1128/cmr.13.4.559-570.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jieun K., Sungi K., Junhyoung A., et al. A Lipid-Nanopillar-Array-Based Immunosorbent Assay. Adv. Mater. 2020;32 doi: 10.1002/adma.202070195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Orooji Y., Sohrabi H., Hemmat N., Oroojalian F., Baradaran B., Mokhtarzadeh A., Mohaghegh M., Karimi-Maleh H. An Overview on SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) and Other Human Coronaviruses and Their Detection Capability via Amplification Assay, Chemical Sensing, Biosensing, Immunosensing, and Clinical Assays. Nanomicro Lett. 2021;13(1) doi: 10.1007/s40820-020-00533-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mautner Lena, Baillie Christin-Kirsty, Herold Heike Marie et al. Rapid point-of-care detection of SARS-CoV-2 using reverse transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification (RT-LAMP). Virol J, 17(2020)160. 10.1186/s12985-020-01435-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Jennifer A. Combining Rapid PCR and Antibody Tests Improved COVID-19 Diagnosis. JAMA. 2020;324:1386. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.19129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Elden Leontine J R, van Loon Anton M, van Alphen Floris et al. Frequent detection of human coronaviruses in clinical specimens from patients with respiratory tract infection by use of a novel real-time reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction. J Infect Dis, 189(2004)652-7. 10.1086/381207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Ng Kevin W, Faulkner Nikhil, Cornish Georgina H et al. Preexisting and de novo humoral immunity to SARS-CoV-2 in humans. Science, 370(2020)1339-1343. 10.1126/science.abe1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Zhaohui Y., Zhen Z.u., Liuying T., et al. Genomic analyses of recombinant adenovirus type 11a in China. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2009;47:3082–3090. doi: 10.1128/jcm.00282-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Langer Judith, Jimenez de Aberasturi Dorleta, Aizpurua Javier et al. Present and Future of Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering. ACS Nano, 14 (2020)28-117. 10.1021/acsnano.9b04224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Zong Cheng X.u., Li-Jia M.X., et al. Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy for Bioanalysis: Reliability and Challenges. Chem. Rev. 2018;118:4946–4980. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xingang Z., Xiaolei Z., Changliang L., et al. Volume-Enhanced Raman Scattering Detection of Viruses. Small. 2019;15 doi: 10.1002/smll.201805516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gayoung E., Ahreum H., Hongki K., et al. Diagnosis of Tamiflu-Resistant Influenza Virus in Human Nasal Fluid and Saliva Using Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering. ACS Sens. 2019;4:2282–2287. doi: 10.1021/acssensors.9b00697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jae-Young L., Jung-Soo N., Hyunku S., et al. Identification of Newly Emerging Influenza Viruses by Detecting the Virally Infected Cells Based on Surface Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy and Principal Component Analysis. Anal. Chem. 2019;91:5677–5684. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.8b05533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang X., Zeng J., Sun Q., et al. An Effective Method towards Label-Free Detection of Antibiotics by Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy in Human Serum. Sens Actuators B Chem. 2021;343 doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2021.130084. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yingchen W., Tuo D., Guiyun Q.i., et al. Prevalence of Common Respiratory Viral Infections and Identification of Adenovirus in Hospitalized Adults in Harbin, China 2014 to 2017. Front. Microbiol. 2018;9:2919. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gagandeep S., Sheela R. Potential for the cross-species transmission of swine torque teno viruses. Vet. Microbiol. 2018;215:66–70. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2017.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leopardi Stefania, Holmes Edward C, Gastaldelli Michele et al. Interplay between co-divergence and cross-species transmission in the evolutionary history of bat coronaviruses. Infect Genet Evol, 58(2018)279-289. 10.1016/j.meegid.2018.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Jonas R.A., Ung L., Rajaiya J., Chodosh J. Mystery eye: Human adenovirus and the enigma of epidemic keratoconjunctivitis. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research. 2020;76:100826. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2019.100826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garcia A.C., Vavrusova M., Skibsted L.H. Supersaturation of calcium citrate as a mechanism behind enhanced availability of calcium phosphates by presence of citrate. Food Res. Int. 2018;107:195–205. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2018.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Papadopoulou E., Bell S. Label-Free Detection of Single-Base Mismatches in DNA by Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2011;50:9058–9061. doi: 10.1002/anie.201102776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.