Abstract

Background

High rates of COVID-19 vaccination uptake are required to attain community immunity. This study aims to identify factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine uncertainty and refusal among young adults, an underexplored population with regards to vaccine intention generally, in two high-income settings: Canada and France.

Methods

A cross-sectional online survey was conducted from October to December 2020 among young adults ages 18–29 years (n = 6663) living in Canada (51.9%) and France (48.1%). Multinomial logistic regression analyses were performed to identify the sociodemographic and COVID-19-related measures (e.g., prevention behavior and perspectives, health-related concerns) associated with vaccine uncertainty and refusal. We conducted weighted analyses by age, gender and province/region of residence.

Results

Intention to accept vaccination was reported by 84.3% and 59.7% of the sample in Canada and France, respectively. Higher levels of vaccine uncertainty and refusal were observed in France compared to Canada (30.1% versus 11%, 10.2% versus 4.7%). In both countries, we found higher levels of vaccine acceptance among young adults who reported COVID-19 prevention actions. Vaccine uncertainty and refusal were associated with living in a rural area, having lower levels of educational attainment, not looking for information about COVID-19, not wearing a face mask, and reporting a lower level of concern for COVID-19′s impact on family. Participants who had been tested for COVID-19 were less likely to intend to refuse a vaccine.

Conclusions

COVID-19 vaccine acceptance was high among young adults in Canada and France during a time in which vaccines were approved for use. Targeted interventions to build confidence in demographic groups with greater hesitance (e.g., rural and with less personal experience with COVID-19) may further boost acceptance and improve equity as vaccine efforts continue to unfold.

Keywords: COVID-19, Vaccination, Young adults, Preventive measures

1. Introduction

Since the authorization for use, beginning in December 2020, of multiple safe and efficacious COVID-19 vaccines [1], [2], [3], [4], national and global efforts have focused on implementing and scaling up vaccination programming. To achieve community immunity sufficient to stop transmission of the virus [5] and prevent severe COVID-19 [6], high levels of population immunity are needed [7]. Therefore, knowledge about vaccine intentions among various priority populations are needed to optimize public health vaccination programming and messaging. While an emerging body of evidence has documented COVID-19 vaccine intention within general adult populations [8] and among those prioritized for COVID-19 immunization (e.g., front-line health care workers) [9], [10], less is known about how vaccine intentions are unfolding within and across young adult populations.

For many young adults, COVID-19 vaccination will represent their first vaccine decision; yet, there are important knowledge gaps about vaccination intention among young adult populations. For example, the majority of the previous research on young adult vaccine acceptance focuses on university and/or medical students [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], with less attention on how vaccine intentions are distributed differentially within and across diverse populations of young adults, including young adults from different geographic regions and socio-economic profiles. Previous research examining vaccine hesitancy among young adults prior to COVID-19 is limited and somewhat equivocal, leaving important questions about the different factors that influence vaccine acceptance rates among young adult populations. There are also important country- and context-dependent factors that need to be accounted for [17], with previous research highlighting how intentions to receive vaccinations is distributed differentially across different countries [18], [19], [20], with France featuring the lowest rate among European countries [21]. These previous findings underscore the need for research that assesses how contextual and population-based differences are unfolding within and across young adult populations in settings such as Canada and France.

At this juncture, international comparative analyses may provide crucial insights into how public health vaccine interventions can best improve uptake rates among young adults within and across jurisdictions [22], [23], [24]. In Canada and France, two high-income settings implementing a universal and priority-phased approach to vaccination programming, young adults (i.e., those ages 18–29) represent an important population that has been prioritized within the final phases of vaccine distribution efforts. Therefore, our objective is to describe COVID-19 vaccine intentions and identify the factors associated with vaccine uncertainty and refusal among young adults in Canada and France during the last quarter of 2020. Our aim is to identify both the context-specific factors within and across each country associated with vaccine intentions, as well as the characteristics of young adults who are unconvinced or indicate they would refuse vaccination.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

We conducted a cross-sectional, online anonymous survey among young adults ages 18–29 years in Canada and France. This online survey was part of the France Canada Observatory on COVID-19, Youth health and Social well-being (FOCUS) that aims to assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the social and health outcomes among young adults living in Canada and France [25]. The survey was launched during the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic between 8 October and 23 December 2020.

2.2. Study settings

France and Canada represent two distinct contexts with different histories and trends associated with vaccination. Prior to the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, France had one of the highest rates of vaccine hesitancy in the world, and negative attitudes towards vaccination in the French general population has increased since the 2009 influenza A (H1N1) episode [26]. In 2018, France extended the government’s child vaccine mandate to require up-to-date status for 11 vaccines in order to access public and private child care and schools [27]. While vaccination experts and health professionals observed an increase in vaccine hesitancy in recent years in Canada [28], vaccine uptake rates were still relatively high when the COVID-19 pandemic emerged [29], [30]. At that time, only three of ten provinces had implemented a vaccine mandate in schools. It is therefore our hypothesis that these and other contextual factors (e.g., political climate, exposure to misinformation) and information from local authorities about vaccination safety and efficacy could differentially impact vaccine intentions among young adults between the France and Canada contexts [31], [32], [33].

In France, the peak of the second wave was reached in early November with>70,000 cases per day for a country with 67 million inhabitants [34]. The Government of France implemented an increasing series of mitigation measures in late September (e.g., limiting social gatherings, closing bar/restaurants) and throughout October including a curfew in metropolitan areas (October 17–30), a nationwide lockdown (October 30-December 15), and a national curfew that began 15 December 2020 [35], [36].

In Canada, the peak of the second wave was reached in early January 2021 with>8,000 daily cases for a country of 38 million inhabitants [37]. In October-November 2020, each province gradually implemented public health measures from avoiding non-essential travel and limiting social gatherings to the closure of non-essential businesses. At the end of December 2020, province-wide lockdowns were announced in Quebec and Ontario [38], [39], the two most populous provinces. The first COVID-19 vaccine approved by Canadian and European health agencies for use was the Pfizer-BioNTech mRNA vaccine, on December 9 and 21 2020 respectively [40], [41].

2.3. Recruitment and data collection procedures

Ethical approval was granted by the University of British Columbia Behavioural Research Ethics Board (H20-02053). Participants were recruited with convenience sampling through online posts and advertisements on social media platforms (e.g., Facebook, Instagram) and on websites of University partners, press articles, and word of mouth. Respondents were eligible to participate if they: were of legal age in their jurisdiction of residence at the time of the survey (18 or 19 years old depending on the Canadian province or territory, and 18 years old in France) and no more than 29 years; resided in Canada or France; were able to complete the survey in English (Canada) or French (either country). The online questionnaire was designed to collect data on sociodemographics, COVID-19 perceptions and experiences, access to healthcare services, and health outcomes (e.g., mental health). Survey data were collected using Qualtrics software. All participants were provided with an option to enter a lottery draw to win one of three cash prizes ($100 in Canada, 100€ in France). Informed consent was requested on the introductory web page and was required prior to the initiation of the survey questionnaire. Participants were also informed that they could stop completing the questionnaire at any time.

2.4. Study sample

The population for the present study included young adults who completed both the sociodemographic section and the question about the vaccination intention of the online survey.

2.5. Outcome: Intention to vaccinate against COVID-19

COVID-19 vaccination intention was measured by asking participants to state how likely they would want to get a vaccine “if there was a safe and effective vaccine for COVID-19” on a 5-point Likert scale (“definitely”, “probably”, “unsure”, “probably not” and “definitely not”). The definition of our outcome “COVID-19 vaccine intention” was constructed to identify the characteristics of young adults who would be less likely to get vaccinated and who may therefore benefit from additional information about vaccine safety and efficacy. Therefore, our first group of interest combined those who were “unsure” and those who reported they would “probably not” get a vaccine (the unconvinced group). Our second group comprised participants who would “definitely not” get the vaccine (the refusal group). As described in the literature on the continuum of vaccine hesitancy [33], [42], [43], the difference in the level of hesitancy between the “unconvinced” and “refusal” groups may be associated with distinct demographic and behavioural factors. Finally, our third group – the reference group – included participants that indicated they would “definitely” or “probably” get vaccinated (the acceptance group).

2.6. Explanatory variables

Sociodemographic characteristics included age, province or region of residence, area of residence (urban versus rural residents), gender, sexual orientation, educational attainment, employment status, individual income, relationship status and living arrangements. Ethno-racial identity was collected in Canada using the Canadian Institute for Health Information standards [44] and not in France due to the prohibition of collecting such data. Canadian participants were also asked to report they experience of discrimination with regards to their ethno-racial identity: “Have you ever experienced discrimination because of your race/ethnicity?”. In France, the question was phrased as follows: “Have you ever experienced discrimination because of your origins?”. Immigration status was collected by asking participants if they were born in Canada or in metropolitan France.

Participants were asked whether, in the past 6 months, they had: been tested for COVID-19 (yes versus no), had received the test result (“yes, negative”; “yes, positive” or “results was not confirmed”), had looked for information about COVID-19, took actions to decrease the risk of getting or transmitting COVID-19, and knew someone who had experienced severe complications from COVID-19 (e.g., requiring hospitalization, death). We also collected information regarding whether or not they had been tested for COVID-19 in the past 6 months and the results of the tests.

Participants were asked to rate five items of the Coronavirus Anxiety Scale (CAS) [45], using a 5-point Likert-type scale (0=“not at all” to 4=“nearly every day over the last two weeks”), regarding how often they experienced physiologically-based symptoms of fear or anxiety when exposed to COVID-19-related information. Participants with a score ≥ 5 were classified as highly anxious about COVID-19 [46]. Level of concern for COVID-19’s impact on the family and economy was assessed by asking the following questions: “How concerned are you about the impact of COVID-19 on: 1/ the health of vulnerable members of your family (e.g., elderly family or those with chronic conditions)? and 2/ the economy and businesses?”. Each question included a 4-item response scale ranging from “not at all”, “a bit concerned” (recoded as low concern), “quite” to “very concerned” (recoded as high concern). Lastly, we asked participants to indicate whether the attention paid by the government to the concerns and needs of young adults since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic was very insufficient, insufficient, sufficient or more than sufficient.

2.7. Statistical analyses

Given the important compositional differences in populations between France and Canada, our sample weighting approach and regression models were conducted separately by country to highlight the context-specific factors associated with vaccine uncertainty and refusal among young adults.

2.7.1. Sample weighting

To reduce demographic bias due to our sample selection, we applied survey weighting to improve the FOCUS survey representativeness of young adults by age, gender, and province/region of residence according to the 2016 Canada Census data [47] and the 2017 Census data of the French National Institute for Statistical and Economic Studies [48]. To match the Census categories available in both countries, we used three age subsets (18–19, 20–24, and 25–29) and the provincial/regional population breakdown of those aged 18–19 to 29 years in each country. Given that gender identity was not collected in the Canadian and French Census surveys, we used the variable “sex” which was measured as a binary biological construct (male versus female) in both countries. In order to better consider the diversity of gender identity in young adults’ population in our weighting process, survey participants who provided a gender identity other than man or woman (i.e., non-binary, Two-Spirit for Indigenous individuals, other gender identity) were assigned a weight of one, which relies on an assumption that the sample proportion for ‘other gender’ is representative of the target population. The gender ratio was calculated by collapsing ‘other gender’ responses and women into one group. We made this decision based on the assumption that participants who identify with a gender identity other than a man or woman (e.g., non-binary) may experience at least (or more) gender oppression as those who identify as women [49]. Participants who reported “prefer not to say” for gender identity (n = 49 in Canada, n = 61 in France) and those who had missing data for the province or region of residence (n = 126 in Canada, n = 102 in France) were excluded from the analysis sample.

Specifically, survey weights were calculated for each participant using a raking ratio estimation procedure [50], an iterative poststratification method through which weights are applied to individual participants based on census marginal totals. Raking is a common method used to adjust survey data to reduce nonresponse and noncoverage biases, as well as sampling variability [51]. As certain categories of the population were highly under-represented in our survey sample (i.e., participants living in Overseas departments in France, those residing in the territory of Nunavut in Canada), estimated weights were trimmed to reduce the effect of extreme weights on sampling variance.

2.7.2. Regression models

Multinomial logistic regression analyses were performed separately for Canada and France. For these analyses, the vaccine acceptance group was set as the reference group to identify factors associated with vaccine uncertainty and refusal, respectively. Subsequently, the models were re-estimated with the vaccine unconvinced group as a reference to identify factors that distinguished vaccine refusing from participants who were unconvinced. All variables with a p-value < 0.20 in the univariate models were entered into the multivariable models, except for age, individual income, and immigration status (only for France) that were included in all models. For variables with > 5% missing data, missing data were imputed as a separate category as data were assumed be missing not at random. Only wearing a face covering was included because it is the primary prevention tool that has been recommended globally since the beginning of the pandemic [52]. We also hypothesized that participants who reported anti-mask attitudes might be less likely to report other prevention action. Statistical significance was considered at p-value < 0.05. Regression models that accounted for adjusted sample weights were performed using the open source ‘survey’ and ‘svrepmisc’ packages in R (version 4.0.3) [53], [54].

3. Results

Of the 8424 participants of the FOCUS survey, 89.4% provided complete sociodemographic data. Among them, 88.5% completed the vaccination intention question and were included in this analysis, for a study sample of 6663. Just over half (51.9%) were from Canada and 48.1% were from France. Participants characteristics in both samples and according to their responses to COVID-19 vaccine intention are described in Table 1, Table 2 . Overall, the majority of participants, 59.7% in France and 84.3% in Canada, indicated they would accept COVID-19 vaccination. A higher proportion of participants in France (30.1%) were unconvinced about getting a vaccine than in Canada (11%). Over twice as many participants in France (11%) than in Canada (5%) said they would definitely not be vaccinated.

Table 1.

Participants characteristics and vaccination intention in the Canadian sample (N = 3459).

|

Weighted, column % |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Canada, n (%) |

COVID-19 vaccine intention |

||||||

| Definitely | Probably | Unsure | Probably not | Definitely not | |||

| All participants | 3459 (1 0 0) | 63.9 | 20.4 | 6.3 | 4.7 | 4.7 | |

| Socio-demographic characteristics | |||||||

| Age (years) | |||||||

| 18–19 | 533 (15.4) | 15.6 | 16.1 | 20.2 | 8.6 | 10.5 | |

| 20–24 | 1471 (42.5) | 42.5 | 42.3 | 45.4 | 46.9 | 35.8 | |

| 25–29 | 1455 (42.1) | 41.9 | 41.7 | 34.4 | 44.4 | 54.3 | |

| Gender identity | |||||||

| Woman | 1506 (43.5) | 44.3 | 43 | 45.4 | 39.5 | 38.3 | |

| Man | 1647 (47.6) | 45.6 | 49.5 | 49.5 | 56.8 | 55.6 | |

| Non-binary/other gender identity$ | 306 (8.8) | 10.2 | 7.5 | 5 | 3.7 | 6.8 | |

| Province of residence§ | |||||||

| Ontario | 1249 (36.1) | 36.9 | 36.6 | 35.8 | 25.9 | 34.6 | |

| Alberta | 447 (12.9) | 13 | 11.3 | 11.9 | 19.8 | 12.3 | |

| Atlantic | 218 (6.3) | 6.7 | 5 | 6.4 | 8 | 5.6 | |

| British Columbia | 475 (13.7) | 15.2 | 11.7 | 11 | 10.5 | 8.6 | |

| Manitoba | 139 (4) | 3.7 | 3.5 | 6 | 3.7 | 8.6 | |

| Quebec | 785 (22.7) | 21 | 27 | 22.9 | 27.8 | 22.2 | |

| Saskatchewan | 117 (3.4) | 2.8 | 4.2 | 4.1 | 3.1 | 7.4 | |

| Territories | 30 (0.9) | 0.8 | 0.6 | 1.8 | 1.2 | 1.2 | |

| Area of residence | |||||||

| Large urban centre | 2076 (60) | 64.4 | 55.7 | 47.2 | 49.4 | 46.3 | |

| Medium city | 722 (20.9) | 20.6 | 22.2 | 22.0 | 17.9 | 20.4 | |

| Rural area | 155 (4.5) | 3.3 | 4.5 | 6.9 | 9.3 | 13.6 | |

| Small city | 506 (14.6) | 11.7 | 17.7 | 23.9 | 23.5 | 19.8 | |

| Sexual orientation | |||||||

| Straight/heterosexual | 1943 (56.2) | 50.4 | 61.8 | 67.4 | 82.7 | 69.8 | |

| Bisexual | 652 (18.8) | 21.3 | 17.0 | 13.3 | 8.6 | 11.1 | |

| Homosexual/gay/lesbian/other sexual minority£ | 778 (22.5) | 25.8 | 19.1 | 17.0 | 7.4 | 14.8 | |

| Missing data | 85 (2.5) | 2.5 | 2.1 | 2.3 | 1.2 | 4.9 | |

| Ethno-racial identity | |||||||

| Not a visible minoritya | 2943 (85.1) | 85.5 | 83.7 | 84.4 | 88.3 | 82.7 | |

| Indigenousb | 154 (4.5) | 4.1 | 5.4 | 5 | 4.3 | 4.9 | |

| Visible minority, non-Indigenousc | 330 (9.5) | 9.9 | 9.2 | 9.6 | 6.8 | 8.6 | |

| Missing data | 31 (0.9) | 0.5 | 1.7 | 0.5 | 0 | 4.3 | |

| Having experienced racial discrimination | |||||||

| Never/Rarely | 3020 (87.3) | 90.1 | 84.9 | 82.1 | 84 | 69.8 | |

| Sometimes/Fairly often/Very often | 406 (11.7) | 9.2 | 14.3 | 16.1 | 13.6 | 27.8 | |

| Missing data | 34 (1) | 0.6 | 1 | 1.8 | 2.5 | 2.5 | |

| Immigration status | |||||||

| Yes | 360 (10.4) | 10.7 | 10 | 9.2 | 11.1 | 9.9 | |

| No | 3092 (89.4) | 89 | 90 | 90.8 | 88.9 | 90.1 | |

| Missing data | 7 (0.2) | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Education | |||||||

| University (some, completed, or above) | 2046 (59.2) | 64.4 | 57 | 44.5 | 37 | 38.9 | |

| High school or college | 1407 (40.7) | 35.3 | 43 | 55 | 63 | 61.7 | |

| Missing data | 6 (0.2) | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Employment status | |||||||

| Employed | 1428 (41.3) | 39.3 | 41.7 | 43.6 | 52.5 | 51.9 | |

| Student | 1576 (45.6) | 48.4 | 45.3 | 43.6 | 28.4 | 28.4 | |

| Unemployed | 377 (10.9) | 9.9 | 11.3 | 12.4 | 16.7 | 15.4 | |

| Missing data | 77 (2.2) | 2.4 | 1.7 | 0.5 | 2.5 | 4.9 | |

| Individual income (last year, Canadian dollars) | |||||||

| Less than $20,000 (annual) | 1687 (48.8) | 49.7 | 49.2 | 49.5 | 39.5 | 42.6 | |

| $20,000 and more (annual) | 1522 (44) | 43.3 | 44 | 41.3 | 53.1 | 48.8 | |

| Missing / Prefer not to say | 250 (7.2) | 7.1 | 6.8 | 9.2 | 7.4 | 8.6 | |

| In a relationship | |||||||

| Yes | 1737 (50.2) | 52.3 | 45.0 | 48.6 | 56.8 | 40.1 | |

| No | 1596 (46.1) | 44.4 | 51.3 | 47.7 | 38.3 | 53.1 | |

| Missing data | 125 (3.6) | 3.3 | 3.7 | 3.2 | 4.9 | 6.8 | |

| Living arrangements | |||||||

| Living with family members | 1222 (35.3) | 35.3 | 35.8 | 42.7 | 27.2 | 31.5 | |

| Living alone | 479 (13.8) | 12.8 | 14.3 | 17 | 21 | 14.8 | |

| Living with a partner | 869 (25.1) | 26.1 | 22.6 | 21.6 | 29.6 | 23.5 | |

| Living with roommate/friends/other | 814 (23.5) | 23.6 | 25.6 | 18.3 | 19.1 | 25.9 | |

| Missing data | 75 (2.2) | 2.3 | 1.7 | 0.5 | 2.5 | 4.3 | |

| COVID-19 prevention strategy in the last 6 months | |||||||

| COVID-19 testing | |||||||

| No | 2248 (65) | 61.9 | 68.3 | 69.7 | 74.1 | 77.8 | |

| Yes, negative or results not confirmed | 1168 (33.8) | 36.8 | 31.4 | 28 | 24.7 | 19.8 | |

| Yes, positive | 21 (0.6) | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 0 | 1.2 | |

| Missing data | 21 (0.6) | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 1.9 | |

| Knowing someone who experienced severe complications from COVID-19 | |||||||

| No | 2857 (82.6) | 81.8 | 82.5 | 80.3 | 89.5 | 90.1 | |

| Yes | 446 (12.9) | 13.4 | 13.3 | 13.8 | 8.6 | 8.0 | |

| Missing data | 156 (4.5) | 4.8 | 4.2 | 6 | 1.9 | 1.9 | |

| Looking for information about COVID-19 | |||||||

| Yes | 3350 (96.8) | 98.9 | 97.7 | 91.3 | 88.3 | 80.9 | |

| No | 99 (2.9) | 1.1 | 2.1 | 6.4 | 11.7 | 17.3 | |

| Missing data | 10 (0.3) | 0 | 0.3 | 1.8 | 0 | 2.5 | |

| Wearing a face covering to decrease COVID -19 risks | |||||||

| No | 187 (5.4) | 1.6 | 5.1 | 5 | 19.8 | 45.7 | |

| Yes | 3270 (94.5) | 98.4 | 95 | 94.5 | 80.2 | 54.3 | |

| Missing data | 1 (0) | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.6 | |

| COVID-19-related perceptions and concerns | |||||||

| COVID-19-related anxiety | |||||||

| Low | 2595 (75) | 73.6 | 77.5 | 76.6 | 76.5 | 80.2 | |

| High | 809 (23.4) | 24.9 | 20.9 | 21.6 | 22.2 | 17.3 | |

| Missing data | 55 (1.6) | 1.5 | 1.6 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 3.1 | |

| Level of concern for family and economy | |||||||

| High concern for family and economy | 1243 (35.9) | 37.5 | 35.8 | 37.6 | 25.3 | 23.5 | |

| High concern for family and low concern for economy | 942 (27.2) | 32.4 | 24.3 | 13.8 | 6.8 | 6.8 | |

| Low concern for family and high concern for economy | 603 (17.4) | 12.1 | 20.8 | 24.8 | 41.4 | 42 | |

| Low concern for family and economy | 429 (12.4) | 12.1 | 11.7 | 14.2 | 17.9 | 12.3 | |

| Missing data | 241 (7) | 5.8 | 7.5 | 9.6 | 8.6 | 15.4 | |

| Government attention to young adults' needs and concerns | |||||||

| Insufficient / Very insufficient | 2382 (68.9) | 68.9 | 67.6 | 70.2 | 66 | 74.1 | |

| Sufficient / More than sufficient | 715 (20.7) | 21.4 | 22.1 | 16.1 | 16 | 16 | |

| Missing data | 363 (10.5) | 9.7 | 10.3 | 13.3 | 17.9 | 9.9 | |

$ Other gender identity included intersex, Two-spirit (only for Canada), and other gender identity with an open-text box.

£ Other sexual minority included asexual, pansexual, queer, Two-spirit (only for Canada) and other sexual identity with an open-text box.

§Atlantic included the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, Prince Edward Island, and Nova Scotia and Territories included Nunavut, Yukon, and the Northwest Territories.

aIncludes those who selected “white” only and those who reported “white and Latino” or “white and Middle-Eastern” as per the definition in the Employment Equity Act [49].

bIncludes those who selected “Indigenous (e.g., First Nations, Métis, Inuk/Inuit descent)”.

cIncludes those who selected any ethno-racial category (one or more) other than white or Indigenous. The visible minority groups include: “Black”, “East Asian”, “Southeast Asian”, “Latino”, “Middle Eastern”, “South Asian”, and those who reported another race category that cannot be classified with a visible minority group.

Table 2.

Participants characteristics and vaccination intention in the French sample (N = 3204).

|

Weighted, column % |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Total France, n (%) |

COVID-19 vaccine intention |

||||||

| Definitely | Probably | Unsure | Probably not | Definitely not | |||

| All participants | 3204 (1 0 0) | 28.2 | 31.5 | 18.2 | 11.9 | 10.2 | |

| Socio-demographic characteristics | |||||||

| Age (years) | |||||||

| 18–19 | 550 (17.2) | 15.9 | 16.1 | 17.8 | 17.9 | 22 | |

| 20–24 | 1316 (41.1) | 43.1 | 39.2 | 41.4 | 40 | 41.3 | |

| 25–29 | 1339 (41.8) | 40.9 | 44.7 | 40.8 | 41.8 | 36.4 | |

| Gender identity | |||||||

| Woman | 1475 (46) | 38.6 | 46.7 | 51.7 | 50 | 49.5 | |

| Man | 1581 (49.3) | 55.8 | 48.9 | 42.6 | 47.1 | 47.7 | |

| Non-binary/other gender identity$ | 148 (4.6) | 5.6 | 4.5 | 5.5 | 2.6 | 3.1 | |

| Region of residence^ | |||||||

| Ile-de-France | 786 (24.5) | 30.8 | 27.2 | 20.4 | 18.7 | 13.5 | |

| Nord Est | 632 (19.7) | 20 | 18.7 | 19 | 21.8 | 20.5 | |

| Ouest | 537 (16.8) | 16.7 | 16.9 | 15.8 | 19.2 | 15.6 | |

| Overseas | 91 (2.8) | 1.4 | 2.1 | 6.8 | 1.6 | 3.1 | |

| Sud Est | 648 (20.2) | 17.8 | 21.1 | 19.9 | 19.2 | 26 | |

| Sud Ouest | 509 (15.9) | 13.3 | 14 | 18.2 | 19.2 | 21.1 | |

| Area of residence | |||||||

| Large urban centre | 1626 (50.7) | 60.4 | 51.1 | 43.3 | 48.9 | 38.5 | |

| Medium city | 676 (21.1) | 20.2 | 19.3 | 23.5 | 21.6 | 24.2 | |

| Rural area | 211 (6.6) | 5.4 | 6.2 | 7.5 | 7.9 | 7.6 | |

| Small city | 692 (21.6) | 14 | 23.4 | 25.7 | 21.6 | 29.7 | |

| Sexual orientation | |||||||

| Straight/heterosexual | 2163 (67.5) | 61.5 | 67.8 | 67.1 | 77.1 | 72.8 | |

| Bisexual | 392 (12.2) | 14.4 | 12.1 | 12.7 | 7.1 | 11.9 | |

| Homosexual/gay/lesbian/other sexual minority£ | 550 (17.2) | 21 | 17.7 | 15.8 | 13.7 | 11.6 | |

| Missing data | 99 (3.1) | 3.1 | 2.5 | 4.3 | 2.1 | 3.7 | |

| Having experienced racial discrimination | |||||||

| Never/Rarely | 2521 (78.7) | 82.5 | 80.2 | 77.9 | 74.2 | 70 | |

| Sometimes/Fairly often/Very often | 226 (7.1) | 6.3 | 6.8 | 8.7 | 5.0 | 8.9 | |

| Missing data | 458 (14.3) | 11.2 | 13.1 | 13.2 | 21.1 | 20.8 | |

| Immigration status | |||||||

| No | 2980 (93) | 94 | 92.8 | 91.3 | 92.9 | 94.2 | |

| Yes | 218 (6.8) | 6.1 | 6.9 | 8.2 | 7.1 | 5.5 | |

| Missing data | 6 (0.2) | 0 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.3 | |

| Education | |||||||

| University (some, completed, or above) | 2065 (64.5) | 68.3 | 69.1 | 60.6 | 57.9 | 53.8 | |

| High school or college | 1128 (35.2) | 31.3 | 30.8 | 38.7 | 41.6 | 45.6 | |

| Missing data | 12 (0.4) | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.3 | |

| Employment status | |||||||

| Employed | 1106 (34.5) | 31.2 | 35.4 | 36.3 | 35 | 36.7 | |

| Student | 1601 (50) | 55.4 | 49.6 | 47.3 | 47.9 | 43.4 | |

| Unemployed | 392 (12.2) | 10.2 | 12.3 | 13 | 11.8 | 16.8 | |

| Missing data | 106 (3.3) | 3.2 | 2.8 | 3.4 | 5.3 | 2.8 | |

| Individual income (last year, Euros) | |||||||

| <1200€ per month | 2009 (62.7) | 65.8 | 59.2 | 63.5 | 62.4 | 64.2 | |

| 1200€ per month and more | 927 (28.9) | 27.2 | 33.1 | 26.9 | 28.9 | 25.1 | |

| Missing / Prefer not to say | 268 (8.4) | 7.1 | 7.8 | 9.6 | 8.7 | 10.7 | |

| In a relationship | |||||||

| Yes | 1427 (44.5) | 42.8 | 46.7 | 42.8 | 43.9 | 46.5 | |

| No | 1552 (48.4) | 52.2 | 46.6 | 50.5 | 45 | 43.7 | |

| Missing data | 225 (7) | 5 | 6.7 | 6.7 | 11.1 | 9.8 | |

| Living arrangements | |||||||

| Living with family members | 934 (29.2) | 26.2 | 29.8 | 32.5 | 24.2 | 34.6 | |

| Living alone | 984 (30.7) | 32.5 | 30.6 | 30.3 | 30.8 | 26.6 | |

| Living with a partner | 683 (21.3) | 19.5 | 22.9 | 18.8 | 22.6 | 24.5 | |

| Living with roommate/friends/other | 470 (14.7) | 18.6 | 12.7 | 14.4 | 16.3 | 8.6 | |

| Missing data | 134 (4.2) | 3.3 | 4 | 3.9 | 6.1 | 5.5 | |

| COVID-19 prevention strategy in the last 6 months | |||||||

| COVID-19 testing | |||||||

| No | 1847 (57.6) | 53.8 | 56.8 | 58.7 | 61.6 | 64.8 | |

| Yes, negative or results not confirmed | 1156 (36.1) | 38.9 | 37.8 | 36.1 | 30.5 | 29.1 | |

| Yes, positive | 167 (5.2) | 6.2 | 4.8 | 4.5 | 6.6 | 4 | |

| Missing data | 34 (1.1) | 1.1 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 1.3 | 2.1 | |

| Knowing someone who experienced severe complications from COVID-19 | |||||||

| No | 2309 (72.1) | 68.7 | 70.7 | 72.4 | 77.1 | 78.9 | |

| Yes | 813 (25.4) | 28.2 | 26.7 | 24.1 | 21.8 | 20.2 | |

| Missing data | 82 (2.6) | 3.1 | 2.7 | 3.4 | 1.1 | 0.9 | |

| Looking for information about COVID-19 | |||||||

| Yes | 3024 (94.4) | 96.8 | 97.7 | 92.6 | 95.3 | 79.5 | |

| No | 171 (5.3) | 2.9 | 2.1 | 7.2 | 4.5 | 19.6 | |

| Missing data | 9 (0.3) | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.9 | |

| Wearing a face covering to decrease COVID -19 risks | |||||||

| No | 398 (12.4) | 5.5 | 9.3 | 11.8 | 16.6 | 37.3 | |

| Yes | 2795 (87.2) | 94.5 | 90.6 | 87.3 | 83.4 | 61.5 | |

| Missing data | 11 (0.3) | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.9 | 0 | 1.2 | |

| COVID-19-related perceptions and concerns | |||||||

| COVID-19-related anxiety | |||||||

| Low | 2527 (78.9) | 80.8 | 81.7 | 74 | 75.5 | 77.4 | |

| High | 549 (17.1) | 16 | 15 | 20.4 | 19.7 | 18 | |

| Missing data | 129 (4) | 3.2 | 3.5 | 5.7 | 4.7 | 4.6 | |

| Level of concern for family and economy | |||||||

| High concern for family and economy | 1285 (40.1) | 42.4 | 40.4 | 42.5 | 38.2 | 30.9 | |

| High concern for family and low concern for economy | 663 (20.7) | 24.9 | 22.3 | 18.3 | 17.1 | 12.5 | |

| Low concern for family and high concern for economy | 516 (16.1) | 13.5 | 14.3 | 17.8 | 17.4 | 24.2 | |

| Low concern for family and economy | 365 (11.4) | 10.1 | 12.7 | 9.4 | 9.7 | 16.8 | |

| Missing data | 376 (11.7) | 9.2 | 10.3 | 12 | 17.9 | 15.6 | |

| Government attention to young adults' needs and concerns | |||||||

| Insufficient / Very insufficient | 2531 (79) | 79 | 78.7 | 76.4 | 81.8 | 81 | |

| Sufficient / More than sufficient | 367 (11.5) | 11.7 | 11.9 | 9.4 | 12.9 | 11 | |

| Missing data | 306 (9.6) | 9.3 | 9.3 | 14.2 | 5 | 7.6 | |

$ Other gender identity included intersex, Two-spirit (only for Canada), and other gender identity with an open-text box.

£ Other sexual minority included asexual, pansexual, queer, Two-spirit (only for Canada) and other sexual identity with an open-text box.

^ Nord Est (Grand-Est, Hauts-de-France, Bourgogne Franche-Comté), Sud Est (Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes, Provence-Alpes-Côte-d’Azur, Corse), Sud Ouest (Nouvelle Aquitaine, Occitanie), and Ouest (Bretagne, Centre Val-de-Loire, Pays de la Loire, Normandie).

3.1. Prevalence of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance

As described in Table 3 , the highest prevalence rates of acceptance in the respective countries were found in the Canadian provinces of British Columbia (88.4%) and Ontario (85.9%) and in the French region of Ile-de-France (70.2%). Those living in large urban areas were more likely to intend to vaccinate in both settings. In both countries, those who identified as bisexual or as a sexual or a gender minority reported a higher level of acceptance compared to their heterosexual and cisgender counterparts (Canada: >90% versus 79.7%, France: >64% versus 57.3%). Higher acceptance rates were also observed in those with university degrees, compared with less formal education (Canada: 89.2%, France: 63.7%), and in those who had been tested negative for COVID-19 (Canada: 88.5%, France: 63.4%). The highest rates of acceptance were found in participants with a high level of concern for family and a low level of concern for the economy (Canada: 94.5%, France: 67.9%). Conversely, more than one third of young adults who were not looking for information about COVID-19 (Canada: 28.3%, France: 37.4%) and those who reported not wearing a face mask (Canada: 39.4%, France: 30.7%) intended to refuse vaccination.

Table 3.

Comparison of the socio-demographic characteristics and COVID-19 related measures per vaccination intention groups in the Canadian (N = 3459) and French samples (N = 3204).

|

Weighted, n (row %) |

p-value1 |

Weighted, n (row %) |

p-value1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Canada (N = 3459) |

France (N = 3204) |

|||||||||

| Acceptance group | Unconvinced group | Refusal group | Acceptance group | Unconvinced group | Refusal group | |||||

| All participants | 2917 (84.3) | 379 (11) | 162 (4.7) | 1914 (59.7) | 963 (30.1) | 327 (10.2) | ||||

| Socio-demographic characteristics | ||||||||||

| Age (years) | 0.004 | 0.003 | ||||||||

| 18–19 | 458 (85.9) | 58 (10.9) | 17 (3.2) | 306 (55.6) | 172 (31.3) | 72 (13.1) | ||||

| 20–24 | 1238 (84.2) | 175 (11.9) | 58 (3.9) | 786 (59.8) | 394 (30) | 135 (10.3) | ||||

| 25–29 | 1220 (83.8) | 147 (10.1) | 88 (6) | 822 (61.4) | 397 (29.7) | 119 (8.9) | ||||

| Gender identity | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Woman | 1282 (85.1) | 163 (10.8) | 62 (4.1) | 820 (55.6) | 493 (33.4) | 162 (11) | ||||

| Man | 1357 (82.4) | 200 (12.1) | 90 (5.5) | 997 (63.1) | 428 (27.1) | 156 (9.9) | ||||

| Non-binary/other gender identity$ | 278 (90.8) | 17 (5.6) | 11 (3.6) | 96 (64.4) | 43 (28.9) | 10 (6.7) | ||||

| Province of residence§ | <0.001 | |||||||||

| Ontario | 1074 (85.9) | 120 (9.6) | 56 (4.5) | _ | _ | _ | ||||

| Alberta | 368 (82.5) | 58 (13) | 20 (4.5) | _ | _ | _ | ||||

| Atlantic | 182 (83.9) | 26 (12) | 9 (4.1) | _ | _ | _ | ||||

| British Columbia | 420 (88.4) | 41 (8.6) | 14 (2.9) | _ | _ | _ | ||||

| Manitoba | 106 (76.3) | 19 (13.7) | 14 (10.1) | _ | _ | _ | ||||

| Quebec | 654 (83.3) | 95 (12.1) | 36 (4.6) | _ | _ | _ | ||||

| Saskatchewan | 91 (77.8) | 14 (12) | 12 (10.3) | _ | _ | _ | ||||

| Territories | 23 (76.7) | 5 (16.7) | 2 (6.7) | _ | _ | _ | ||||

| Region of residence^ | <0.001 | |||||||||

| Ile-de-France | _ | _ | _ | 552 (70.2) | 190 (24.2) | 44 (5.6) | ||||

| Nord Est | _ | _ | _ | 370 (58.5) | 195 (30.9) | 67 (10.6) | ||||

| Ouest | _ | _ | _ | 322 (59.9) | 165 (30.7) | 51 (9.5) | ||||

| Overseas | _ | _ | _ | 34 (37.4) | 47 (51.6) | 10 (11) | ||||

| Sud Est | _ | _ | _ | 374 (57.8) | 188 (29.1) | 85 (13.1) | ||||

| Sud Ouest | _ | _ | _ | 261 (51.3) | 179 (35.2) | 69 (13.6) | ||||

| Area of residence | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Large urban centre | 1817 (87.6) | 183 (8.8) | 75 (3.6) | 1062 (65.3) | 439 (27) | 126 (7.7) | ||||

| Medium city | 612 (84.8) | 77 (10.7) | 33 (4.6) | 378 (55.9) | 219 (32.4) | 79 (11.7) | ||||

| Rural area | 103 (66.5) | 30 (19.4) | 22 (14.2) | 112 (53.1) | 74 (35.1) | 25 (11.8) | ||||

| Small city | 384 (75.9) | 90 (17.8) | 32 (6.3) | 363 (52.5) | 232 (33.5) | 97 (14) | ||||

| Sexual orientation | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Straight/heterosexual | 1550 (79.7) | 281 (14.5) | 113 (5.8) | 1240 (57.3) | 685 (31.7) | 238 (11) | ||||

| Bisexual | 592 (90.7) | 43 (6.6) | 18 (2.8) | 253 (64.4) | 101 (25.7) | 39 (9.9) | ||||

| Homosexual/gay/lesbian/other sexual minority£ | 706 (90.6) | 49 (6.3) | 24 (3.1) | 368 (66.9) | 144 (26.2) | 38 (6.9) | ||||

| Missing data | 70 (82.4) | 7 (8.2) | 8 (9.4) | 53 (54.1) | 33 (33.7) | 12 (12.2) | ||||

| Ethno-racial identity | 0.8 | |||||||||

| Not a visible minoritya | 2482 (84.3) | 327 (11.1) | 134 (4.6) | _ | _ | _ | ||||

| Indigenousb | 128 (83.1) | 18 (11.7) | 8 (5.2) | _ | _ | _ | ||||

| Visible minority, non-Indigenousc | 284 (85.8) | 33 (10) | 14 (4.2) | _ | _ | _ | ||||

| Missing data | 23 (74.2) | 1 (3.2) | 7 (22.6) | _ | _ | _ | ||||

| Having experienced racial discrimination | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Never/Rarely | 2592 (85.8) | 315 (10.4) | 113 (3.7) | 1555 (61.7) | 737 (29.2) | 229 (9.1) | ||||

| Sometimes/Fairly often/Very often | 304 (75.1) | 56 (13.8) | 45 (11.1) | 126 (56) | 70 (31.1) | 29 (12.9) | ||||

| Missing data | 21 (63.6) | 8 (24.2) | 4 (12.1) | 232 (50.8) | 157 (34.4) | 68 (14.9) | ||||

| Immigration status | 0.2 | |||||||||

| No | 2603 (84.2) | 342 (11.1) | 146 (4.7) | 0.8 | 1786 (59.9) | 886 (29.7) | 308 (10.3) | |||

| Yes | 307 (85.3) | 37 (10.3) | 16 (4.4) | 125 (57.3) | 75 (34.4) | 18 (8.3) | ||||

| Missing data | 7 (1 0 0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (50) | 2 (33.3) | 1 (16.7) | ||||

| Education | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| University (some, completed, or above) | 1826 (89.2) | 157 (7.7) | 63 (3.1) | 1315 (63.7) | 574 (27.8) | 176 (8.5) | ||||

| High school or college | 1085 (77.1) | 222 (15.8) | 100 (7.1) | 594 (52.7) | 384 (34.1) | 149 (13.2) | ||||

| Missing data | 6 (1 0 0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (45.5) | 5 (45.5) | 1 (9.1) | ||||

| Employment status | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Employed | 1164 (81.5) | 180 (12.6) | 84 (5.9) | 640 (57.9) | 345 (31.2) | 120 (10.9) | ||||

| Student | 1389 (88.1) | 141 (8.9) | 46 (2.9) | 1001 (62.5) | 458 (28.6) | 142 (8.9) | ||||

| Unemployed | 299 (79.3) | 53 (14.1) | 25 (6.6) | 216 (55.1) | 121 (30.9) | 55 (14) | ||||

| Missing data | 64 (84.2) | 4 (5.3) | 8 (10.5) | 58 (54.7) | 39 (36.8) | 9 (8.5) | ||||

| Individual income (last year, Canadian dollars) | 0.12 | |||||||||

| Less than $20,000 (annual) | 1446 (85.7) | 172 (10.2) | 69 (4.1) | _ | _ | _ | ||||

| $20,000 and more (annual) | 1266 (83.2) | 177 (11.6) | 79 (5.2) | _ | _ | _ | ||||

| Missing / Prefer not to say | 204 (81.9) | 31 (12.4) | 14 (5.6) | _ | _ | _ | ||||

| Individual income (last year, Euros) | 0.008 | |||||||||

| <1200€ per month | _ | _ | _ | 1192 (59.3) | 608 (30.2) | 210 (10.4) | ||||

| 1200€ per month and more | _ | _ | _ | 579 (62.4) | 267 (28.8) | 82 (8.8) | ||||

| Missing / Prefer not to say | _ | _ | _ | 143 (53.6) | 89 (33.3) | 35 (13.1) | ||||

| In a relationship | 0.024 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Yes | 1474 (84.9) | 198 (11.4) | 65 (3.7) | 858 (60.1) | 417 (29.2) | 152 (10.7) | ||||

| No | 1344 (84.2) | 166 (10.4) | 86 (5.4) | 943 (60.8) | 466 (30) | 143 (9.2) | ||||

| Missing data | 99 (79.2) | 15 (12) | 11 (8.8) | 113 (50) | 81 (35.8) | 32 (14.2) | ||||

| Living arrangements | 0.009 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Living with family members | 1034 (84.5) | 138 (11.3) | 51 (4.2) | 538 (57.7) | 282 (30.2) | 113 (12.1) | ||||

| Living alone | 384 (80.2) | 71 (14.8) | 24 (5) | 603 (61.3) | 294 (29.9) | 87 (8.8) | ||||

| Living with a partner | 736 (84.7) | 95 (10.9) | 38 (4.4) | 407 (59.6) | 196 (28.7) | 80 (11.7) | ||||

| Living with roommate/friends/other | 702 (86.1) | 71 (8.7) | 42 (5.2) | 296 (63) | 146 (31.1) | 28 (6) | ||||

| Missing data | 62 (83.8) | 5 (6.8) | 7 (9.5) | 70 (52.2) | 46 (34.3) | 18 (13.4) | ||||

| COVID-19 prevention strategy in the last 6 months | ||||||||||

| COVID-19 testing | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| No | 1851 (82.3) | 271 (12.1) | 126 (5.6) | 1059 (57.3) | 576 (31.2) | 212 (11.5) | ||||

| Yes, negative or results not confirmed | 1035 (88.5) | 102 (8.7) | 32 (2.7) | 733 (63.4) | 328 (28.4) | 95 (8.2) | ||||

| Yes, positive | 17 (81) | 2 (9.5) | 2 (9.5) | 103 (61.7) | 51 (30.5) | 13 (7.8) | ||||

| Missing data | 15 (68.2) | 4 (18.2) | 3 (13.6) | 18 (52.9) | 9 (26.5) | 7 (20.6) | ||||

| Knowing someone who experienced severe complications from COVID-19 | 0.015 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| No | 2390 (83.7) | 319 (11.2) | 146 (5.1) | 1335 (57.9) | 714 (30.9) | 258 (11.2) | ||||

| Yes | 390 (87.2) | 44 (9.8) | 13 (2.9) | 524 (64.4) | 224 (27.5) | 66 (8.1) | ||||

| Missing data | 137 (87.8) | 16 (10.3) | 3 (1.9) | 55 (66.3) | 25 (30.1) | 3 (3.6) | ||||

| Looking for information about COVID-19 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Yes | 2876 (85.9) | 342 (10.2) | 131 (3.9) | 1861 (61.5) | 903 (29.9) | 260 (8.6) | ||||

| No | 38 (38.4) | 33 (33.3) | 28 (28.3) | 48 (28.1) | 59 (34.5) | 64 (37.4) | ||||

| Missing data | 2 (20) | 4 (40) | 4 (40) | 5 (55.6) | 1 (11.1) | 3 (33.3) | ||||

| Wearing a face covering to decrease COVID -19 risks | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| No | 71 (37.8) | 43 (22.9) | 74 (39.4) | 143 (36) | 132 (33.2) | 122 (30.7) | ||||

| Yes | 2846 (87) | 336 (10.3) | 88 (2.7) | 1768 (63.2) | 827 (29.6) | 201 (7.2) | ||||

| Missing data | 0 (0) | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | 2 (18.2) | 5 (45.5) | 4 (36.4) | ||||

| COVID-19-related perceptions and concerns | ||||||||||

| COVID-19-related anxiety | 0.038 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Low | 2174 (83.8) | 291 (11.2) | 130 (5) | 1554 (61.5) | 719 (28.5) | 253 (10) | ||||

| High | 698 (86.2) | 84 (10.4) | 28 (3.5) | 296 (53.9) | 194 (35.3) | 59 (10.7) | ||||

| Missing data | 45 (81.8) | 5 (9.1) | 5 (9.1) | 63 (48.8) | 51 (39.5) | 15 (11.6) | ||||

| Level of concern for family and economy | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| High concern for family and economy | 1081 (87) | 123 (9.9) | 38 (3.1) | 791 (61.6) | 393 (30.6) | 101 (7.9) | ||||

| High concern for family and low concern for economy | 890 (94.5) | 41 (4.4) | 11 (1.2) | 450 (67.9) | 172 (25.9) | 41 (6.2) | ||||

| Low concern for family and high concern for economy | 415 (68.7) | 121 (20) | 68 (11.3) | 266 (51.7) | 170 (33) | 79 (15.3) | ||||

| Low concern for family and economy | 350 (81.4) | 60 (14) | 20 (4.7) | 219 (59.8) | 92 (25.1) | 55 (15) | ||||

| Missing data | 182 (75.5) | 34 (14.1) | 25 (10.4) | 187 (49.9) | 137 (36.5) | 51 (13.6) | ||||

| Government attention to young adults' needs and concerns | <0.001 | 0.3 | ||||||||

| Insufficient / Very insufficient | 2001 (84) | 260 (10.9) | 120 (5) | 1509 (59.6) | 757 (29.9) | 265 (10.5) | ||||

| Sufficient / More than sufficient | 628 (87.8) | 61 (8.5) | 26 (3.6) | 226 (61.7) | 104 (28.4) | 36 (9.8) | ||||

| Missing data | 288 (79.6) | 58 (16) | 16 (4.4) | 179 (58.5) | 102 (33.3) | 25 (8.2) | ||||

1P-value calculated from Chi-squared test with Rao & Scott's second-order correction.

$ Other gender identity included intersex, Two-spirit (only for Canada), and other gender identity with an open-text box.

£ Other sexual minority included asexual, pansexual, queer, Two-spirit (only for Canada) and other sexual identity with an open-text box.

§Atlantic included the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, Prince Edward Island, and Nova Scotia and Territories included Nunavut, Yukon, and the Northwest Territories.

^ Nord Est (Grand-Est, Hauts-de-France, Bourgogne Franche-Comté), Sud Est (Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes, Provence-Alpes-Côte-d’Azur, Corse), Sud Ouest (Nouvelle Aquitaine, Occitanie), and Ouest (Bretagne, Centre Val-de-Loire, Pays de la Loire, Normandie).

aIncludes those who selected “white” only and those who reported “white and Latino” or “white and Middle-Eastern” as per the definition in the Employment Equity Act [49].

bIncludes those who selected “Indigenous (e.g., First Nations, Métis, Inuk/Inuit descent)”.

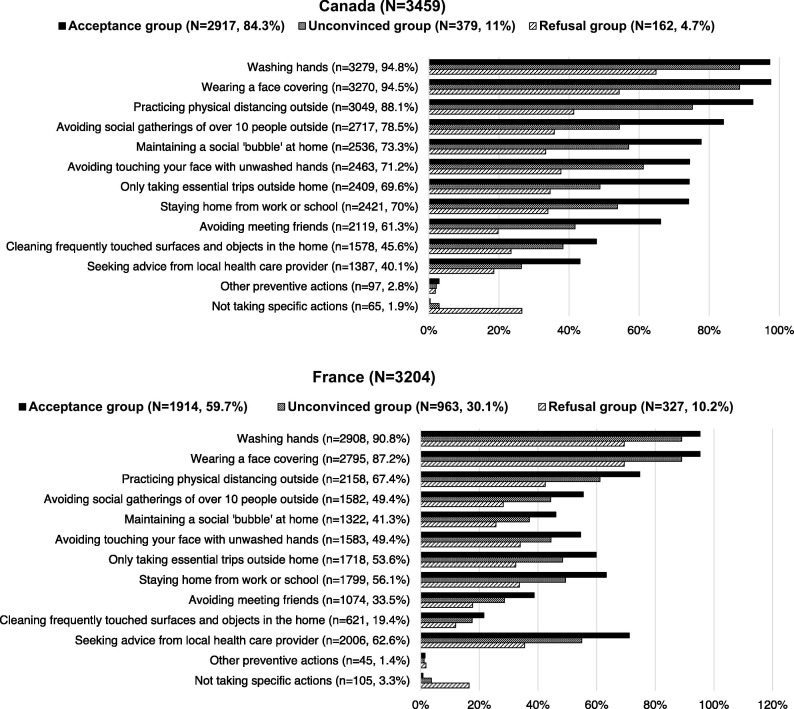

3.2. Vaccination intention and COVID-19 prevention actions

The variation in COVID-19 prevention actions across vaccine intention groups in the Canadian and French samples is reported in Fig. 1 , respectively. In both countries, the vaccine acceptance group reported significantly more COVID-19 prevention actions compared to the unconvinced and refusal groups (p < 0.05). However, respondents who intended to refuse vaccination were more likely to report taking no actions to decrease the risks from COVID-19 compared to the vaccine acceptance and unconvinced participants groups (p < 0.05).

Fig. 1.

COVID-19 prevention actions in vaccine intention groups.

3.3. Factors associated with being unconvinced about COVID-19 vaccination

The results from multinomial regression models to identify factors associated with vaccine uncertainty and refusal are presented in Table 4 . In both countries, participants living in a small city or in a rural area (Canada: AOR 1.97 [1.45–2.69] and AOR 2.48 [1.60–3.87] respectively, France: AOR 1.22 [1.01–1.47] only for small city), having a lower level of educational attainment (Canada: AOR 2.03 [1.59–2.59], France: AOR 1.63 [1.34–1.97]), and reporting not looking for information about COVID-19 (Canada: AOR 4.14 [2.21–7.75], France: AOR 2.88 [1.96–4.21]) had higher odds of being unconvinced about vaccination. Conversely, reporting wearing a face covering (Canada: AOR 0.39 [0.25–0.60], France: AOR 0.55 [0.43–0.70]) were less likely to be unconvinced. Young adults who identified as bisexual or another sexual minority (Canada: AOR 0.53 [0.39–0.73] and AOR 0.49 [0.35–0.70] respectively, France AOR 0.74 [0.60–0.91] only for other sexual minority) were less likely to be unconvinced compared to heterosexual individuals. In both countries, young adults with low concern for family and high concern for the economy were more likely to be unconvinced (Canada: AOR 2.25 [1.68–3.01], France: AOR 1.47 [1.20–1.79]) while those with high concern for family and low concern for the economy were less likely to be unconvinced (Canada: AOR 0.48 [0.35–0.64], France: AOR 0.40 [0.22–0.75]). In Canada, participants who said that the attention given by the government to young adults’ needs was sufficient (AOR: 0.67 [0.60–0.89]), and those who knew someone with severe complications from COVID-19 (AOR: 0.76 [0.65–0.90]) were less likely to be unconvinced. In France, difference per region was also observed: young adults residing in regions other than Ile-de-France had higher odds of being unconvinced (AORs ranged from 1.26 in Sud Est to 2.84 in Overseas departments, 95% CIs ranged from 1.02 to 1.56 to 1.48–5.42). French participants who were unconvinced were more likely to live with roommates (AOR: 1.34 [1.06–1.68]) and have higher anxiety levels (AOR: 1.60 [1.33–1.91]), and less likely to be a man (AOR: 0.62 [0.57–0.73]), be students (AOR: 0.62 [0.50–0.76]) and to have tested negative for COVID-19 (AOR: 0.76 [0.66–0.89]).

Table 4.

Sociodemographic and COVID-related health measures associations with vaccine intention among young adults: results from the multivariable multinomial logistic analyses.

| Weighted, AOR [95% CIs]1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canada | France | ||||||

|

Reference: Acceptance group |

Reference: Unconvinced group |

Reference: Acceptance group |

Reference: Unconvinced group |

||||

| Unconvinced group | Refusal group | Refusal group | Unconvinced group | Refusal group | Refusal group | ||

| Socio-demographic characteristics | |||||||

| Age (years) | |||||||

| 18-19 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |

| 20-24 | 1.43 [0.98, 2.08] | 2.10 [1.01, 4.34] | 1.46 [0.69, 3.13] | 1.02 [0.82, 1.27] | 0.82 [0.59, 1.12] | 0.80 [0.57, 1.11] | |

| 25-29 | 1.17 [0.75, 1.82] | 3.29 [1.43, 7.56] | 2.82 [1.19, 6.66] | 1.03 [0.77, 1.38] | 0.53 [0.33, 0.86] | 0.52 [0.32, 0.84] | |

| Gender identity | |||||||

| Woman | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |

| Man | 0.80 [0.63, 1.02] | 0.46 [0.29, 0.72] | 0.57 [0.35, 0.92] | 0.62 [0.54, 0.73] | 0.46 [0.36, 0.59] | 0.74 [0.57, 0.96] | |

| Non-binary/other gender identity$ | 0.72 [0.43, 1.19] | 1.15 [0.53, 2.51] | 1.6 [0.65, 3.94] | 0.85 [0.59, 1.21] | 0.49 [0.27, 0.90] | 0.58 [0.31, 1.09] | |

| Province of residence§ | |||||||

| Ontario | Ref | Ref | Ref | _ | _ | _ | |

| Alberta | 1.29 [0.89, 1.86] | 0.93 [0.44, 1.95] | 0.72 [0.33, 1.59] | _ | _ | _ | |

| Atlantic | 1.10 [0.74, 1.62] | 0.73 [0.34, 1.57] | 0.67 [0.30, 1.50] | _ | _ | _ | |

| British Columbia | 0.85 [0.61, 1.19] | 0.63 [0.35, 1.13] | 0.74 [0.38, 1.41] | _ | _ | _ | |

| Manitoba | 1.26 [0.73, 2.17] | 2.68 [1.26, 5.71] | 2.14 [0.93, 4.90] | _ | _ | _ | |

| Quebec | 1.25 [0.88, 1.76] | 0.99 [0.57, 1.72] | 0.79 [0.43, 1.46] | _ | _ | _ | |

| Saskatchewan | 1.07 [0.61, 1.87] | 1.49 [0.64, 3.47] | 1.39 [0.55, 3.48] | _ | _ | _ | |

| Territories | 1.19 [0.67, 2.10] | 0.54 [0.17, 1.68] | 0.45 [0.14, 1.44] | _ | _ | _ | |

| Region of residence^ | |||||||

| Ile-de-France | _ | _ | _ | Ref | Ref | Ref | |

| Nord Est | _ | _ | _ | 1.58 [1.26, 1.98] | 1.74 [1.19, 2.55] | 1.10 [0.74, 1.64] | |

| Ouest | _ | _ | _ | 1.32 [1.04, 1.67] | 1.32 [0.90, 1.93] | 1.00 [0.67, 1.49] | |

| Overseas | _ | _ | _ | 2.84 [1.48, 5.42] | 2.34 [0.68, 8.01] | 0.82 [0.25, 2.67] | |

| Sud Est | _ | _ | _ | 1.26 [1.02, 1.56] | 1.84 [1.29, 2.63] | 1.46 [1.01, 2.12] | |

| Sud Ouest | _ | _ | _ | 1.82 [1.45, 2.28] | 2.26 [1.54, 3.30] | 1.24 [0.83, 1.84] | |

| Area of residence | |||||||

| Large urban centre | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |

| Medium city | 1.25 [0.94, 1.66] | 1.38 [0.83, 2.29] | 1.11 [0.63, 1.96] | 1.18 [0.98, 1.41] | 1.31 [0.99, 1.73] | 1.11 [0.83, 1.49] | |

| Rural area | 2.48 [1.60, 3.87] | 4.68 [2.22, 9.87] | 1.88 [0.87, 4.05] | 1.22 [0.90, 1.66] | 1.11 [0.69, 1.79] | 0.91 [0.57, 1.45] | |

| Small city | 1.97 [1.45, 2.69] | 2.17 [1.29, 3.63] | 1.10 [0.63, 1.90] | 1.22 [1.01, 1.47] | 1.33 [0.99, 1.78] | 1.09 [0.81, 1.47] | |

| Sexual orientation | |||||||

| Straight/heterosexual | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |

| Bisexual | 0.53 [0.39, 0.73] | 0.91 [0.57, 1.44] | 1.71 [1.00, 2.90] | 0.74 [0.60, 0.91] | 0.86 [0.62, 1.20] | 1.17 [0.82, 1.67] | |

| Homosexual/gay/lesbian/other sexual minority£ | 0.49 [0.35, 0.70] | 0.75 [0.42, 1.33] | 1.52 [0.80, 2.90] | 0.82 [0.67, 1.01] | 0.77 [0.57, 1.05] | 0.94 [0.68, 1.29] | |

| Ethno-racial identity | |||||||

| Not a visible minoritya | Ref | Ref | Ref | _ | _ | _ | |

| Indigenousb | 1.21 [0.71, 2.08] | 1.21 [0.63, 2.34] | 1.00 [0.47, 2.13] | _ | _ | _ | |

| Visible minority, non-Indigenousc | 1.03 [0.64, 1.66] | 1.16 [0.56, 2.39] | 1.12 [0.49, 2.54] | ||||

| Immigration status* | |||||||

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Yes | 0.98 [0.69, 1.38] | 0.60 [0.34, 1.05] | 0.61 [0.35, 1.08] | ||||

| Having experienced racial discrimination | |||||||

| Never/Rarely | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |

| Sometimes/Fairly often/Very often | 1.22 [0.81, 1.83] | 1.44 [0.83, 2.50] | 1.18 [0.65, 2.16] | 1.10 [0.82, 1.47] | 1.66 [1.08, 2.56] | 1.51 [0.95, 2.40] | |

| Missing data | 1.23 [0.86, 1.75] | 1.80 [1.13, 2.89] | 1.47 [0.91, 2.38] | ||||

| Education | |||||||

| University (some, completed, or above) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |

| High school or college | 2.03 [1.59, 2.59] | 2.47 [1.64, 3.73] | 1.22 [0.78, 1.91] | 1.63 [1.34, 1.97] | 1.66 [1.24, 2.22] | 1.02 [0.76, 1.38] | |

| Employment status | |||||||

| Employed | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |

| Student | 0.79 [0.60, 1.04] | 0.80 [0.46, 1.40] | 1.02 [0.56, 1.83] | 0.62 [0.50, 0.76] | 0.45 [0.32, 0.63] | 0.73 [0.51, 1.04] | |

| Unemployed | 0.93 [0.66, 1.32] | 0.51 [0.28, 0.94] | 0.55 [0.28, 1.07] | 0.77 [0.59, 1.01] | 0.91 [0.61, 1.36] | 1.18 [0.78, 1.79] | |

| Individual income (last year, Canadian dollars) | |||||||

| Less than $20,000 (annual) | Ref | Ref | Ref | _ | _ | _ | |

| $20,000 and more (annual) | 0.99 [0.74, 1.31] | 0.83 [0.51, 1.35] | 0.84 [0.50, 1.42] | _ | _ | _ | |

| Missing / Prefer not to say | 1.16 [0.71, 1.89] | 1.22 [0.43, 3.47] | 1.06 [0.36, 3.13] | _ | _ | _ | |

| Individual income (last year, Euros) | |||||||

| Less than 1200€ per month | _ | _ | _ | Ref | Ref | Ref | |

| 1200€ per month and more | _ | _ | _ | 0.82 [0.66, 1.01] | 0.59 [0.42, 0.84] | 0.73 [0.51, 1.04] | |

| Missing / Prefer not to say | _ | _ | _ | 1.09 [0.77, 1.52] | 1.37 [0.88, 2.11] | 1.26 [0.78, 2.03] | |

| In a relationship | |||||||

| Yes | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |

| No | 0.78 [0.59, 1.02] | 1.86 [1.17, 2.97] | 2.40 [1.46, 3.95] | 1.03 [0.87, 1.22] | 0.85 [0.66, 1.11] | 0.83 [0.64, 1.08] | |

| Missing data | _ | _ | _ | 1.09 [0.66, 1.82] | 0.89 [0.43, 1.86] | 0.81 [0.38, 1.72] | |

| Living arrangements | |||||||

| Living with family members | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |

| Living alone | 1.40 [0.98, 2.00] | 0.66 [0.37, 1.19] | 0.47 [0.25, 0.88] | 1.08 [0.89, 1.32] | 0.91 [0.67, 1.22] | 0.84 [0.62, 1.14] | |

| Living with a partner | 0.98 [0.71, 1.34] | 1.08 [0.62, 1.88] | 1.11 [0.61, 2.02] | 1.05 [0.82, 1.33] | 1.13 [0.78, 1.63] | 1.08 [0.73, 1.58] | |

| Living with roommate/friends/other | 0.90 [0.65, 1.24] | 0.83 [0.48, 1.42] | 0.92 [0.51, 1.66] | 1.34 [1.06, 1.68] | 0.74 [0.52, 1.07] | 0.56 [0.38, 0.81] | |

| COVID-19 prevention strategy in the last 6 months | |||||||

| COVID-19 testing | |||||||

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |

| Yes, negative or results not confirmed | 0.91 [0.71, 1.18] | 0.57 [0.36, 0.91] | 0.62 [0.38, 1.03] | 0.76 [0.66, 0.89] | 0.71 [0.56, 0.91] | 0.93 [0.72, 1.20] | |

| Yes, positive | 1.97 [0.25, 15.3] | 5.38 [0.00, >99] | 2.73 [0.00, >99] | 0.98 [0.71, 1.34] | 0.93 [0.57, 1.50] | 0.95 [0.57, 1.59] | |

| Knowing someone who experienced severe complications from COVID-19 | |||||||

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |

| Yes | 0.94 [0.67, 1.32] | 1.08 [0.57, 2.06] | 1.15 [0.58, 2.30] | 0.76 [0.65, 0.90] | 0.75 [0.56, 1.00] | 0.98 [0.72, 1.32] | |

| Looking for information about COVID-19 | |||||||

| Yes | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |

| No | 4.14 [2.21, 7.75] | 6.04 [2.98, 12.3] | 1.46 [0.74, 2.89] | 2.88 [1.96, 4.21] | 6.14 [3.92, 9.61] | 2.14 [1.44, 3.18] | |

| Wearing a face covering to decrease COVID -19 risks | |||||||

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |

| Yes | 0.39 [0.25, 0.60] | 0.07 [0.04, 0.11] | 0.17 [0.10, 0.29] | 0.55 [0.43, 0.70] | 0.17 [0.12, 0.22] | 0.30 [0.23, 0.40] | |

| OVID-19-related perceptions and concerns | |||||||

| COVID-19-related anxiety | |||||||

| Low | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |

| High | 1.03 [0.80, 1.34] | 0.70 [0.44, 1.12] | 0.68 [0.41, 1.12] | 1.60 [1.33, 1.91] | 1.42 [1.05, 1.93] | 0.89 [0.65, 1.21] | |

| Level of concern for family and economy | |||||||

| High concern for family and economy | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |

| High concern for family and low concern for economy | 0.48 [0.35, 0.64] | 0.40 [0.22, 0.75] | 0.85 [0.43, 1.66] | 0.8 [0.66, 0.96] | 0.71 [0.51, 0.98] | 0.89 [0.63, 1.25] | |

| Low concern for family and high concern for economy | 2.25 [1.68, 3.01] | 3.11 [1.86, 5.22] | 1.39 [0.80, 2.41] | 1.47 [1.20, 1.79] | 2.20 [1.64, 2.97] | 1.50 [1.11, 2.04] | |

| Low concern for family and economy | 1.41 [0.99, 2.01] | 1.25 [0.68, 2.29] | 0.89 [0.45, 1.75] | 0.85 [0.67, 1.08] | 1.28 [0.89, 1.83] | 1.50 [1.03, 2.18] | |

| Missing data | 1.18 [0.65, 2.14] | 2.61 [1.31, 5.21] | 2.22 [0.90, 5.49] | 1.31 [0.87, 1.98] | 1.11 [0.62, 1.99] | 0.85 [0.47, 1.53] | |

| Government attention to young adults' needs and concerns | |||||||

| Insufficient / Very insufficient | Ref | Ref | Ref | _ | _ | _ | |

| Sufficient / More than sufficient | 0.67 [0.50, 0.89] | 0.81 [0.51, 1.30] | 1.22 [0.71, 2.09] | _ | _ | _ | |

| Missing data | 1.44 [1.03, 2.01] | 0.72 [0.40, 1.31] | 0.50 [0.27, 0.94] | _ | _ | _ | |

Note: statistically significant associations (p < 0.05) are highlighted in bold.

1AOR = Adjusted Odds Ratio, CI = Confidence Interval.

$ Other gender identity included intersex, Two-spirit (only for Canada), and other gender identity with an open-text box.

£ Other sexual minority included asexual, pansexual, queer, Two-spirit (only for Canada) and other sexual identity with an open-text box.

§Atlantic included the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, Prince Edward Island, and Nova Scotia and Territories included Nunavut, Yukon, and the Northwest Territories.

^ Nord Est (Grand-Est, Hauts-de-France, Bourgogne Franche-Comté), Sud Est (Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes, Provence-Alpes-Côte-d’Azur, Corse), Sud Ouest (Nouvelle Aquitaine, Occitanie), and Ouest (Bretagne, Centre Val-de-Loire, Pays de la Loire, Normandie).

aIncludes those who selected “white” only and those who reported “white and Latino” or “white and Middle-Eastern” as per the definition in the Employment Equity Act [49].

bIncludes those who selected “Indigenous (e.g., First Nations, Métis, Inuk/Inuit descent)”.

cIncludes those who selected any ethno-racial category (one or more) other than white or Indigenous. The visible minority groups include: “Black”, “East Asian”, “Southeast Asian”, “Latino”, “Middle Eastern”, “South Asian”, and those who reported another race category that cannot be classified with a visible minority group.

*The variable “immigration status” was not included in our multivariable analysis among Canadian participants because it was associated with the variable “ethno-racial identity”.

3.4. Factors associated with intention to refuse COVID-19 vaccination

In the models comparing the vaccine acceptance and refusal groups (Table 4), similar associations found in the unconvinced/acceptance models were observed for residing in other regions that Ile-de-France, living in small city/rural area, having low educational attainment, looking for information about COVID-19, wearing a face covering, and the level of concern for family and economy. In contrast, age was an important factor to distinguish those intending to refuse from unconvinced participants. In Canada, those who intended to refuse a COVID-19 vaccine were more likely to be aged between 20 and 24 or 25–29 years (AOR: 2.10 [1.01–4.34]; AOR: 3.29 [1.43–7.56] respectively) compared to the youngest group (i.e., 18–19). In France, young adults aged between 25 and 29 years were less likely to refuse than those aged 18–19 years (AOR: 0.53 [0.33–0.86]). In both countries, participants who identified as man or non-binary (France: 0.46 [0.36–0.59] and AOR 0.49 [0.27–0.90] respectively, Canada: AOR 0.46 [0.29–0.72] only for men), and those who were tested negative for COVID-19 were less likely to say they would refuse vaccination (Canada: AOR 0.57 [0.36–0.91]), France: AOR 0.71 [0.56–0.91]). Canadian participants who intended to refuse a vaccine were more likely to live in Manitoba (AOR: 2.68 [1.26–5.76]), be single (AOR: 1.86 [1.17–2.97]), and less likely to be unemployed (AOR: 0.51 [0.28–0.94]). In France, students (AOR: 0.45 50.32–0.63]) and young adults with a lower income (AOR: 0.59 [0.42–0.84]) were less likely to intend to refuse while those reporting experiences of racial discrimination had higher odds of intending to refuse vaccination (AOR: 1.66 [1.08–2.56]).

3.5. Differences between the unconvinced and refusal groups

In the models comparing the unconvinced and refusal groups (Table 4), being aged 25–29 years (AOR: 2.82 [1.19–6.66]) was associated with refusal in Canada while it was the opposite for French participants of the same age group (AOR: 0.52 [0.32–0.84]). In Canada, those who were single were more likely to intend to refuse a COVID-19 vaccine (AOR: 2.40 [1.46–3.95]). In both countries, being a man (Canada: AOR 0.57 [0.35–0.92]), France: AOR 0.74 [0.57–0.96] and wearing a face covering (Canada: AOR 0.17 [0.10–0.29], France: AOR 0.30 [0.23–0.40]) were associated with intention to refuse vaccination. In Canada, those who were living alone were less likely to intend to refuse a vaccine than to be unconvinced (AOR: 0.47 [0.25–0.88]) while in France, it was those who were living with one or more roommates (AOR: 0.56 [0.38–0.81]). French participants who lived in Sud Est (AOR: 1.46 [1.01–2.12]) and those who were not looking for information (AOR: 2.14 [1.44–3.18]) were more likely to intend to refuse a vaccine. Lastly, young adults living in France who had low concern for family and low or high concern for the economy (AOR: 1.50 [1.03–2.18] and AOR: 1.50 [1.11–2.04], respectively) had higher odds of intending to refuse vaccination.

As shown in the Supplementary Tables, the main significant associations with vaccine uncertainty and refusal (e.g., age, living in small city/rural area, lower level of education, getting tested for COVID-19, not looking for information about COVID-19, not wearing a face covering, level of concern for family and economy) persisted in our analysis with unweighted samples.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to describe factors influencing intentions to vaccinate against COVID-19 among a large sample of young adults. We found that 84.3% of participants intended to get a COVID-19 vaccine in Canada, which is consistent with previous surveys conducted in the general population during the same period of time (i.e., November-December 2020) where 77%-80% of Canadian adults indicated a willingness to be vaccinated [55], [56]. In France, 59.7% of participants reported an acceptance to be vaccinated against COVID-19, a higher rate than findings from the national survey CoviPrev where 53% of French adults in November and 40% in December 2020 reported that they would get a vaccine [57]. These results align with high levels of vaccine acceptance (ranging from 61% to 95%) reported among university and medical students in Italian and US surveys [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], suggesting that young adults are at least as likely, if not more likely, to intend to be vaccinated than older adults.

Despite this encouraging trend, our findings indicate concerning levels of COVID-19 vaccine uncertainty and refusal, particularly in France where respectively 30.1% and 10.2% were unconvinced or unwilling to be vaccinated. In Canada, these levels were half as high: 11% were unconvinced and only 4.7% intended to refuse vaccination. This trend was previously documented in a multi-country survey across all age groups conducted in June 2020 in which 69% of Canadians versus 59% of French reported that they would accept to take a COVID-19 vaccine [19].

Contextual factors, including negative attitudes towards vaccination in the pre-COVID-19 era, were already widespread in France compared to Canada and may help explain the different acceptance rates. For example, a global survey in 2016 indicated that 67% of respondents from France felt vaccines are unsafe (versus 36% in Canada) and 64% had negative thoughts about vaccine effectiveness (versus 45% in Canada) [18]. In France, previous research has also documented a lack of trust in government and health authorities [58], [59]. For instance, a recent Ipsos survey suggests the public’s confidence in the government’s ability to deal effectively with COVID-19 was lower in France compared to Canada in January 2021 (36% versus 60%) [60]. Although a higher proportion of the current study’s participants from France reported that they felt government attention was insufficient (80% versus 69% in Canada), no significant associations were found between assessment of government attention and vaccine intentions in either country. Additional research is needed to explore the reasons why young adults intend to be unconvinced and refuse vaccination to identify messaging that will be most effective for this important priority population.

These findings have important implications for public health COVID-19 vaccine communication strategies among young adult populations. For example, these findings offer a glimpse into how different population sub-groups of young adults may be more likely to express vaccine uncertainty and refusal. Specifically, young adults who reported not looking for information about COVID-19 and those who reported not wearing a face covering were less likely to intend to get vaccinated. This profile may portray a sub-group of young adults who believe that their likelihood of acquiring (and therefore transmitting) COVID-19 is low. Conversely, participants who experienced COVID-19 testing were more willing to get vaccinated compared to those who had not been tested. In France, our findings tend to show that young adults who got COVID-19 were more likely to intend to accept vaccination (61.7% versus 30.5% and 7.8% in the unconvinced and refusal groups, respectively). As previously described in a US study among adults [61], these results may reflect an increase in perceived risk of contracting COVID-19 and a greater engagement in preventive behaviors. Participants who had access to COVID-19 testing may also be prone to navigating health services more easily or have greater confidence in health providers, which has been known as a determinant of vaccine acceptance [33]. Low levels of concern for COVID-19′s impact on one’s family was also associated with increased vaccine uncertainty and refusal, suggesting that those with lower perceptions of COVID-19 risk should be target populations for vaccination programs.

Our findings also highlight that young adults living in rural areas and those with lower educational attainment were more likely to be unconvinced about vaccination. This is consistent with very recent surveys conducted in US adults from the general population [62], [63], but not necessarily with prior Canadian [64] or French surveys [65], suggesting that these associations may be shifting over time, perhaps due to increasing partisanship of vaccine hesitancy [66]. Although additional research is needed to better understand the influence of rurality and education on vaccine intention among young adults [63], on-going and future vaccination programs may benefit from outreach strategies to reach sub-groups of young adults who are living in areas where access to health services and health information is more difficult, and where vaccination may have become politicized in a partisan manner. As previously described [23], [67], we also found that women were less prone to say they would probably or definitely get vaccinated. Nevertheless, this result should be interpreted with caution as the preliminary results on vaccine uptake in Canada indicate that young women ages 18–29 are getting vaccinated (i.e., first dose) at higher rates than young men as of May 2021 (29% versus 19%) [68]. Both the higher uptake and the higher expressed uncertainty may relate to the internationally documented phenomenon of women in affluent ‘western’ countries perceiving COVID-19 as a greater health risk then did men in the same countries [69]. Our analysis also suggests that young adults in France who have experienced racial discrimination were more likely to intend to refuse vaccination. These findings underscore the need for public health policy and programming that addresses the colonial and racist underpinnings of public health that continue to contribute towards health inequities among people of colour.

While most significant associations were found in both countries (e.g., young adults living in remote areas, those with less personal experience with COVID-19), it is important to acknowledge that our findings also show country-specific factors associated with vaccine intention. For example, in Canada, those who intended to refuse a COVID-19 vaccine were more likely to be aged between 20 and 24 or 25–29 years (compared to the 18–19 group) while in France, the older group (25–29) was less likely to intend to refuse vaccination. Differences in terms of socio-economic status was also observed between Canada and France. Canadian participants who were single and those who were living alone were more likely to intend to refuse a vaccine, while in France, being a student and reporting a lower income were associated with lower odds of intending to refuse vaccination. Finally, COVID-19-related anxiety was only associated with vaccine uncertainty among French participants. These differences in findings between Canada and France underscore the need to investigate vaccination intentions in different settings to develop and implement vaccine communication strategies tailored to the contexts in which vaccine campaigns are conducted.

This study has several limitations. First, while our study sample was weighted to be representative of the Canadian and French young adults’ population by age, gender, and province/region of residence, we note several potential biases that may limit the generalizability of our findings. Namely, weighting does not address other potential biases such as under-coverage, self-selection, and non-responses biases, which are each implicated within our sampling procedure [70], [71], [72]. Because survey recruitment and data collection procedures all occurred online, our sample likely does not include those who did not have internet access and do not use social media; these groups are difficult to characterize and obtain accurate estimates that can be accounted for in the weighting process [72]. In addition, it is possible that those who were more interested in the issues investigated by our survey (e.g., COVID-19-related concerns, mental health) were also more likely to respond. Finally, weighting was conducted using only complete cases with respect to age, gender and province/region of residence, which relies on the assumption of Missing Completely at Random (MCAR) – any departure from the MCAR assumption may represent additional sources of bias in the estimates (this applies for both unweighted and weighed estimates). Second, our study was launched during the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic and several contextual changes may have influenced the intention to get vaccinated. In the 12 months since this survey was conducted, Canada and France have faced three new waves (i.e., spring, late summer and winter 2021) and implemented COVID-19 vaccine campaigns from late December 2020. Although vaccine uptake rates have rapidly increased in both countries, with>80% of young adults ages 18–29 years being fully vaccinated in January 2022 (respectively, 84% in Canada [73] and 94% in France [74]), our findings remain relevant as each setting implements booster immunization efforts. Third, vaccine intention was assessed prior to a vaccine being approved for use within these settings.

5. Conclusion

Intention to accept a COVID-19 vaccine is high among young adults in Canada and France. Given young adults represent the most affected age group in terms of COVID-19 cases, their engagement in vaccination programs will play a key role to achieve community immunity and contribute to ending the COVID-19 pandemic. Thoughtful and targeted vaccination messaging needs to be developed alongside young adults to counter mistrust sentiments and improve vaccine acceptance in order to enhance COVID-19 vaccine uptake among young adults.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to the young adults who took part in the FOCUS survey, as well as the current and past researchers and staff involved with this survey. We also thanks Dr. Biljana Jonoska Stojkova for her statistical support in conducting the weighting process.

Funding

This study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Funding Reference Number: VR5 172673). The funder of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.02.085.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Baden L.R., El Sahly H.M., Essink B., Kotloff K., Frey S., Novak R., et al. Efficacy and Safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(5):403–416. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2035389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Polack F.P., Thomas S.J., Kitchin N., Absalon J., Gurtman A., Lockhart S., et al. Safety and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(27):2603–2615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine | FDA [Internet]. [cited 2021 Feb 15]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/emergency-preparedness-and-response/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19/moderna-covid-19-vaccine.

- 4.Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine | FDA [Internet]. [cited 2021 Feb 15]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/emergency-preparedness-and-response/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19/pfizer-biontech-covid-19-vaccine#additional.

- 5.Weekes M., Jones N.K., Rivett L., Workman C., Ferris M., Shaw A., et al. Single-dose BNT162b2 vaccine protects against asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. Authorea Prepr. 2021 doi: 10.7554/eLife.68808. Feb 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dagan N., Barda N., Kepten E., Miron O., Perchik S., Katz M.A., et al. BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine in a Nationwide Mass Vaccination Setting. N Engl J Med [Internet]. 2021;384(15):1412–1423. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2101765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aguas R, Corder RM, King JG, Gonçalves G, Ferreira MU, Gabriela Gomes MM. Herd immunity thresholds for SARS-CoV-2 estimated from unfolding epidemics. medRxiv [Internet]. 2020 Nov 16 [cited 2021 Jul 15];2020.07.23.20160762. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.23.20160762.

- 8.Lin C, Tu P, Beitsch LM. Confidence and Receptivity for COVID-19 Vaccines: A Rapid Systematic Review. Vaccines [Internet]. 2020 Dec 30 [cited 2021 Feb 12];9(1):16. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-393X/9/1/16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Verger P., Scronias D., Dauby N., Adedzi K.A., Gobert C., Bergeat M., et al. Attitudes of healthcare workers towards COVID-19 vaccination: a survey in France and French-speaking parts of Belgium and Canada, 2020. Eurosurveillance. 2021;26(3) doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2021.26.3.2002047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grech V., Gauci C., Agius S. Vaccine hesitancy among Maltese healthcare workers toward influenza and novel COVID-19 vaccination. Early Hum Dev. 2020 Oct;1 doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2020.105213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barello S., Nania T., Dellafiore F., Graffigna G., Caruso R. ‘Vaccine hesitancy’ among university students in Italy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur J Epidemiol. 2020;35(8):781–783. doi: 10.1007/s10654-020-00670-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pastorino R, Villani L, Mariani M, Ricciardi W, Graffigna G, Boccia S. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Flu and COVID-19 Vaccination Intentions among University Students. Vaccines [Internet]. 2021 Jan 20 [cited 2021 Feb 16];9(2):70. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-393X/9/2/70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Qiao S, Tam CC, Li X. Risk exposures, risk perceptions, negative attitudes toward general vaccination, and COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among college students in South Carolina. medRxiv. medRxiv; 2020. p. 2020.11.26.20239483. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Qiao S, Friedman DB, Tam CC, Zeng C, Li X. Vaccine acceptance among college students in South Carolina: Do information sources and trust in information make a difference? medRxiv. medRxiv; 2020. p. 2020.12.02.20242982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Lucia V.C., Kelekar A., Afonso N.M. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among medical students. J Public Health (Bangkok) [Internet]. 2021;43(3):445–449. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdaa230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Szmyd B, Bartoszek A, Karuga FF, Staniecka K, Błaszczyk M, Radek M. Medical Students and SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination: Attitude and Behaviors. Vaccines [Internet]. 2021 Feb 5 [cited 2021 Feb 16];9(2):128. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-393X/9/2/128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Raz A., Keshet Y., Popper-Giveon A., Karkabi M.S. One size does not fit all: Lessons from Israel’s Covid-19 vaccination drive and hesitancy. Vaccine [Internet]. 2021;39(30):4027–4028. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]