Abstract

Background:

While much is known about the genetic regulation of early valvular morphogenesis, mechanisms governing fetal valvular growth and remodeling remain unclear. Hemodynamic forces strongly influence morphogenesis, but it is unknown whether or how they interact with valvulogenic signaling programs. Side specific activity of valvulogenic programs motivates the hypothesis that shear stress pattern specific endocardial signaling controls the elongation of leaflets.

Results:

We determined that extension of the semilunar valve occurs via fibrosa sided endocardial proliferation. Low OSS was necessary and sufficient to induce canonical Wnt/β-catenin activation in fetal valve endothelium, which in turn drives BMP receptor/ligand expression, and pSmad1/5 activity essential for endocardial proliferation. In contrast, ventricularis endocardial cells expressed active Notch1 but minimal pSmad1/5. Endocardial monolayers exposed to LSS attenuate Wnt signaling in a Notch1 dependent manner.

Conclusions:

Low OSS is transduced by endocardial cells into canonical Wnt signaling programs that regulate BMP signaling and endocardial proliferation. In contrast, high LSS induces Notch signaling in endocardial cells, inhibiting Wnt signaling and thereby restricting growth on the ventricular surface. Our results identify a novel mechanically regulated molecular switch, whereby fluid shear stress drives growth of valve endothelium, orchestrating the extension of the valve in the direction of blood flow.

Keywords: valvulogenesis, valve remodeling, cardiovascular development, shear stress, mechanical regulation

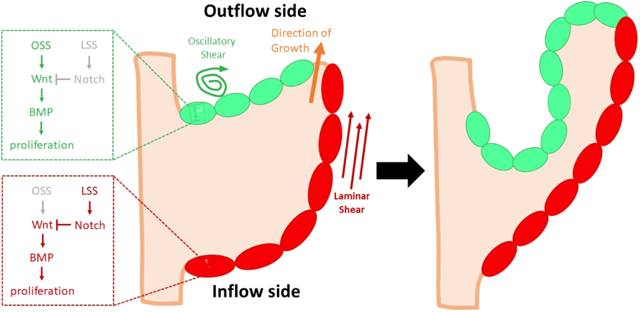

Graphical Abstract

During valve remodeling, the growth of valve primordia requires endocardial proliferation and accommodation. The endocardium on the outflow side of the developing valve (green) senses and transduces low oscillatory shear stress (OSS) to activate canonical Wnt/β-catenin and subsequent canonical BMP signaling that drive endocardial proliferation. In contrast, the endocardial cells on the inflow side of the valve (red) experience laminar shear stress (LSS), activating Notch1 signaling which restricts endocardial growth by inhibiting nuclear translocation of β-catenin. This differential proliferation causes the valve to extend in the direction of blood flow (orange arrow)

Introduction

Congenital heart defects (CHDs) affect about 1 million people1 in the United States. Congenital valve defects account for 20–30% of CHDs, are the most common cause of preterm fetal demise, and can lead to serious complications after birth.2,3 The quest for new therapeutic targets remains a challenge in part because genetics alone does not fully address the etiology of CVDs. In fact, single gene defects and chromosomal abnormalities are responsible for only 10–15% of CHD.4

Heart valve primordia are initiated by endocardial-mesenchymal transition (EndMT), in which endocardial cells differentiate into mesenchymal cells, delaminate, and migrate into the space between the endocardium and myocardium.5 In the outflow tract (OFT), EndMT and the migration of cardiac neural crest (CNC)-derived cells give rise to the mesenchyme of the embryonic semilunar valve cushions.6 After the cellularized cushions fuse to form distinct left and right outflow lumens, the remaining valve primordia grow into thin fibrous leaflets. While the regulation of EndMT during valve formation has been extensively studied,5,7,8 molecular and cellular mechanisms of fetal valvular remodeling remain unclear. Defects in these later phases of morphogenesis that generate clinically significant human valvular malformations but are challenging to study due to premature lethality with genetic manipulation and/or experimental inaccessibility.

Several signaling pathways are known to regulate valve formation, especially during EndMT, including bone morphogenic protein (BMP), Notch, and Wnt signaling.9 These pathways are active during mid-to-late gestation, and previous image data hint at the side-specificity of their expression, though this specificity was unreported. BMP2, 4, 6 appear to be expressed preferentially on the arterial surface of the OFT,10 as is the case with canonical Wnt signaling.11 In contrast, Notch appears to be expressed on the ventricular surface of the OFT.12,13 BMP is associated with priming endocardial cells for EndMT during early valve formation and regulating mesenchymal cell proliferation during valve remodeling.8 Endocardial Notch1/Jag1 signaling has been shown to be required for restraining cushion hypercellularity post-EndMT.9,13–15 Notch1/Jag1 is also required for modulating deposition of proteoglycans and periostin,15 which is required for mesenchymal cell differentiation and matrix maturation.16 Finally, Wnt signaling is involved in proliferation, paradoxically both driving mesenchymal proliferation17 and attenuating mesenchymal growth.18 However, the roles of these signaling pathways in valve maturation and remodeling are not well understood, especially in a gain-of-function sense, in part due to the difficulty and limitations of the use genetic knockout models. BMP ligands and receptors can compensate for one another.8 Notch1 null mutants are embryonic lethal at E10.5, and null mutants of ligands DLL4 and Jag1 are also embryonic lethal.15 Furthermore, Wnt ligands in the AVC endocardium also compensate for each other,9 and endocardial β-catenin knockouts have defective EndMT, causing embryonic lethality by mid-gestation.17,19

Alternatively, remodeling can be studied via the mechanical forces that modulate the process. Altered blood flow in chick embryos can lead to various CVDs that resemble those observed in human babies,20 suggesting that hemodynamic aberrations can explain some valve malformations. Endocardial cells on the inflow side of the OFT valves experience high magnitude laminar shear stress (LSS) in vivo, which is shear stress induced by unidirectional fluid flow. In contrast, cells on the outflow side experience low oscillatory shear stress (OSS), shear stress induced by bidirectional fluid flow that constantly reverses in direction. Expression patterns of signaling pathways appear to reflect this differential flow on either side of the valve. At H33, BMP2/4/6 are expressed in the arterial side of the valve endocardium.10 However, the transduction of hemodynamic signals, as well as the effect of such signals on remodeling must further be explored.

The expressions of signaling programs during fetal valve remodeling are spatially and temporally regulated.10,17,21,22 However, due to current difficulties with genetic models in studying these programs, neither the mechanisms of spatial and temporal regulations of the programs nor the environmental cues that govern them are well known. Genetic manipulation allows for the inference of the role of a gene by their global or lineage specific absence from a tissue, which is challenging in a heterogeneously populated tissue like valves. Furthermore, it is unlikely that the morphological development of the heart valve can be attributed to genetics alone. As the heart grows the meet increased nutrient demands amidst increased embryo size and changes in vascular resistance, the valves must grow accordingly. In this study, we examine the complementary roles that hemodynamic cues play in the spatiotemporal regulation of valve remodeling through accommodation of growth and extension of the valve by the valve endocardium.

Results

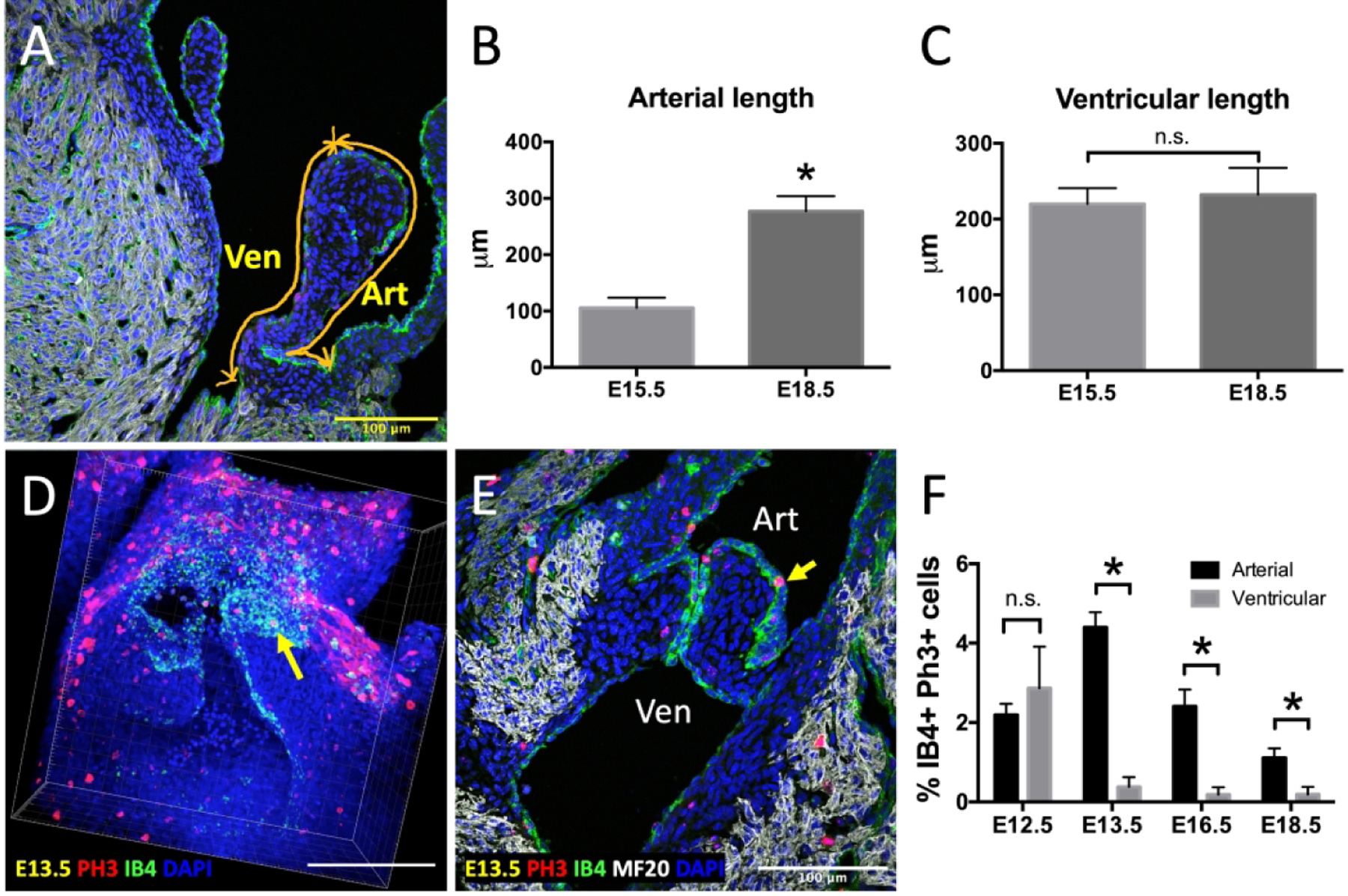

Valve leaflet extension occurs exclusively via fibrosa surface endocardial proliferation

To assess endocardial growth during valve development at the tissue level, we measured the perimeter of valve primordia on the outflow (arterial) and inflow (ventricular) sides (Figure 1A). The outflow perimeter increased acutely from 105μm at E15.5 to 276μm at E18.5, while there was no difference in endocardial length on the inflow side during the same time frame (Figures 1B, C). We then monitored mitotic activity in the endocardium during valve remodeling from E12.5 to E18.5. Quantitative analysis revealed that mitotic activity was statistically higher on the outflow side of the valve than the inflow side from mid- to late-gestation. At E13.5, the rates of proliferation were 4.4% and 0.4% for outflow and inflow sides, respectively, while at E18.5 the rates were 2.5% and 0.2%. The data also demonstrate that proliferation on the outflow side decreased as the heart continued developing (Figure 1F).

Figure 1.

Enhanced endocardial proliferation and growth on the arterial side of the OFT valves. A, Schematic showed how valve perimeters on the arterial side (Art) and the ventricular side (Ven) were measured. B, Quantification of endocardial length on the arterial side of E15.5, and E18.5 embryos. C, Quantification of ventricular length on the arterial side of E15.5, and E18.5 embryos. D-E, Representative phospho-histone 3 (PH3, red) immunostaining images of E13.5 whole mount reconstruction (D) and 2D section (E) showing more mitotic cells on the outflow or arterial side (Art) compared to inflow or ventricular side (Ven) in the OFT. Yellow arrows indicate PH3-positive endocardial cells. Myocardial cells were stained with MF20 (white), while endocardial cells were stained with IB4 (green). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). F, Quantification of proliferation based on the percentage of cells double positive for IB4 and PH3 over the total number of IB4+ cells. Bar graph shows comparisons between arterial and ventricular endocardial cells between E12.5 and E18.5. Data are means ± SEM. n ≥ 5 embryos per group (B and C), and n ≥ 3 embryos per group (F) and *p < 0.05 via Student t test. Scale bars indicate 100 μm.

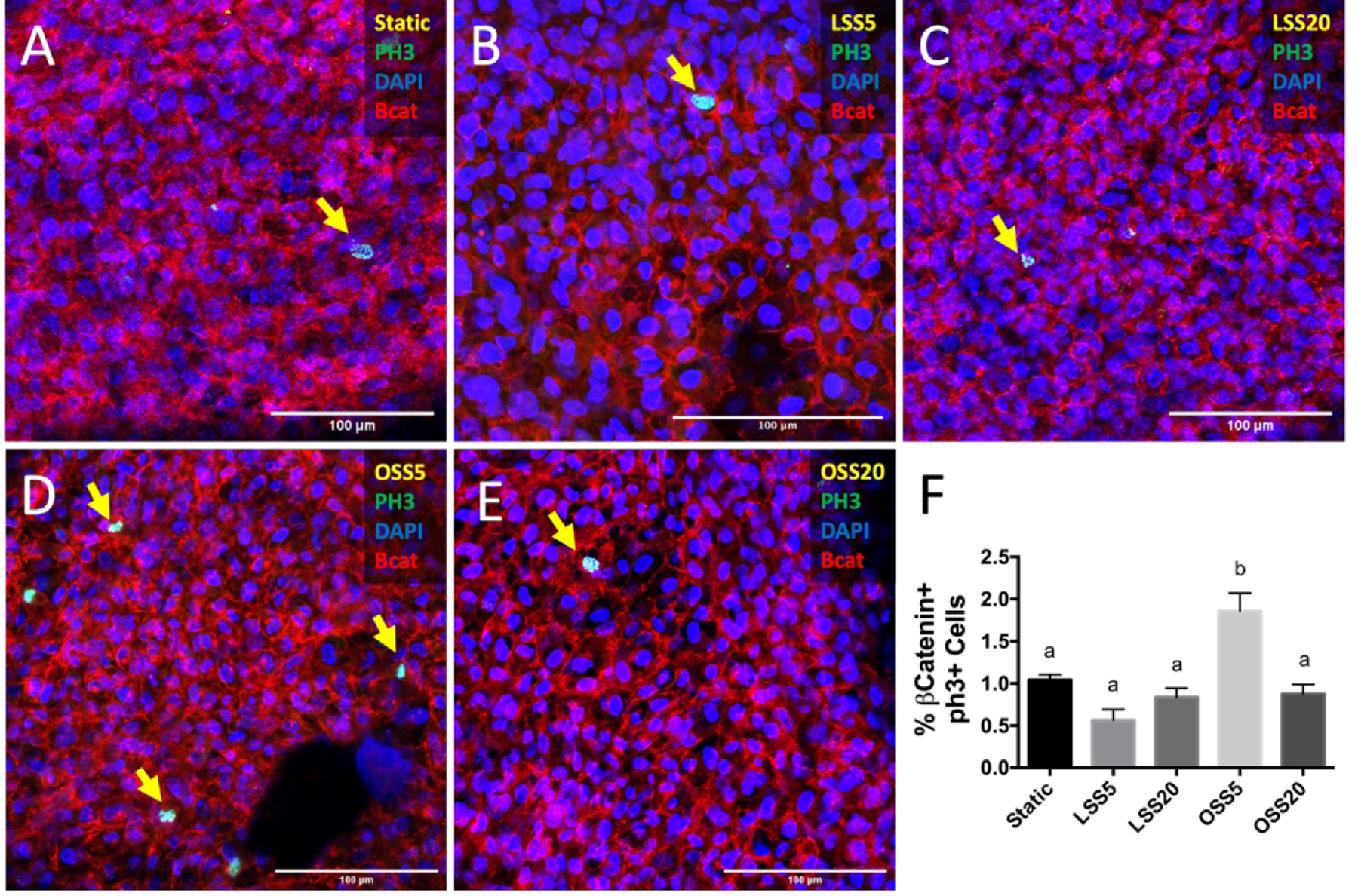

Endocardial proliferation is induced by low magnitude OSS

We then investigated the role of shear stress in this differential proliferation by exposing primary chick embryonic endocardial cells cultured from the ventricular side of the valve to different shear environments. We found that the incidence of proliferation was 77% higher in cells exposed to OSS at 5 dynes/cm2 (OSS5) compared to the static control (Figures 2A and 2D), suggesting that OSS5 is sufficient to induce proliferation on the inflow side of the valves, which normally exhibit downregulated proliferation in vivo (Figure 1). In contrast, other shear conditions – LSS at 5 dynes/cm2 (LSS5), LSS at 20 dynes/cm2 (LSS20), and OSS at 20 dynes/cm2 (OSS20) – had no effect on endocardial proliferation (Figures 2B, C, E).

Figure 2.

Enhanced proliferation under low oscillatory shear. Immunostaining of phosphorylated histone 3 (PH3, green), indicative of active mitosis, in static (A), LSS at 5 dynes/cm2 (LSS5, B), LSS 20 dynes/cm2 (LSS20, C), OSS at 5 dynes/cm2 (OSS5, D), and OSS at 20 dynes/cm2 (OSS20, E). Endocardial cells were stained with β-catenin (red), and nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). F, Quantification of PHH3 activity based on percentage of endocardial cells positive for nuclear PHH3. Yellow arrows indicate PH3-positive proliferating cells. Data are means ± SEM. n ≥ 7 endocardial patches per group. Bars that do not share any letters are significantly different (p < 0.05) via ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparisons correction). Scale bars indicate 100 μm.

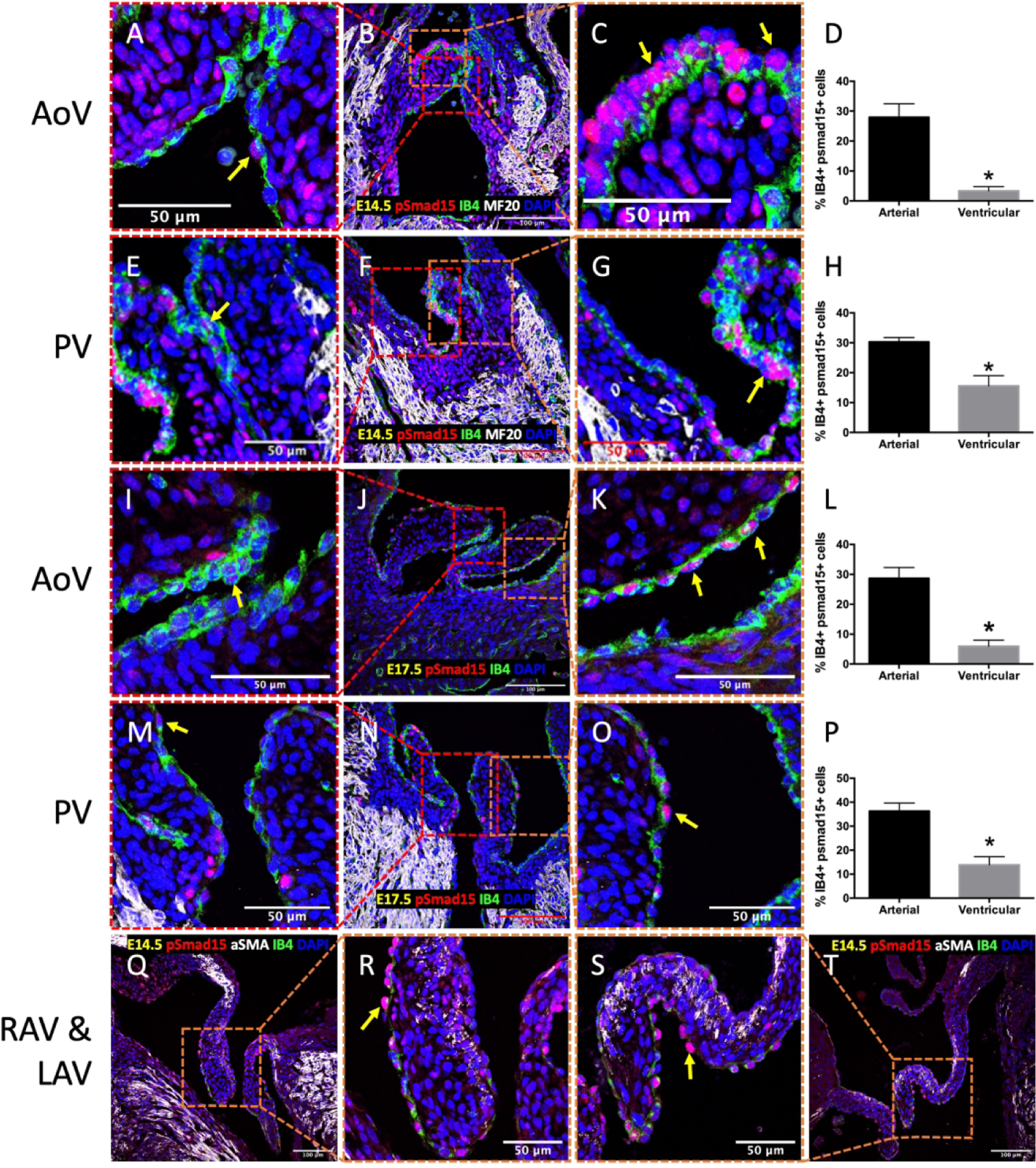

Valve endocardial proliferation associates with side-specific BMP signaling

To begin identifying the factors that mediate this upregulation of proliferation, we examined BMP signaling activity during valve remodeling by performing immunostaining for phosphorylated Smad1/5 (pSmad1/5) in endocardial cells. In the E14.5 aortic valve (AoV), there was a significantly higher proportion of endocardial cells positive for nuclear pSmad1/5 on the outflow side (28%) than the inflow side (4%, Figure 3D), a pattern that was also seen in the E14.5 pulmonary valve (30% and 16%; Figure 3H). Immunostaining further revealed more pSmad1/5-positive endocardial cells on the outflow side of the atrioventricular valves at E14.5 (Figures 3Q–T). This outflow sided endocardial specific pSmad1/5 activity persists through late gestation (E17.5, Figures 3L, 3P) concomitant with valve extension. We also performed a similar analysis on pSmad2/3, which is indicative of TGF-β signaling, another subfamily of proteins in the TGF-β family. However, there was no differential expression in the semilunar valves at E17.5 (Figure 4D). These data establish a conserved program of outflow sided endocardial BMP activity that associates with endocardial proliferation and valve extension.

Figure 3.

Enhanced BMP signaling in endocardial cells on the outflow side of fetal heart valves. Immunostaining of phosphorylated Smad15 (pSmad1/5) in AoV (A-C, I-K) and PV (E-G, M-O) at E14.5 and E17.5. Immunostaining of pSmad1/5 in RAV (Q-R) and LAV (S-T) at E14.5. Arrows indicate positive pSmad1/5 cells (red). Myocardial cells were stained with MF20 or αSMA (white), while endocardial cells were stained with IB4 (green). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). D, H, L, P, Quantification of BMP signaling based on percentage of nuclear pSmad1/5 and IB4 double positive cells. Data are means ± SEM. n = 3 embryos per group. *p < 0.05 via Student t test. Scale bars indicate 100 μm, or 50 μm where indicated.

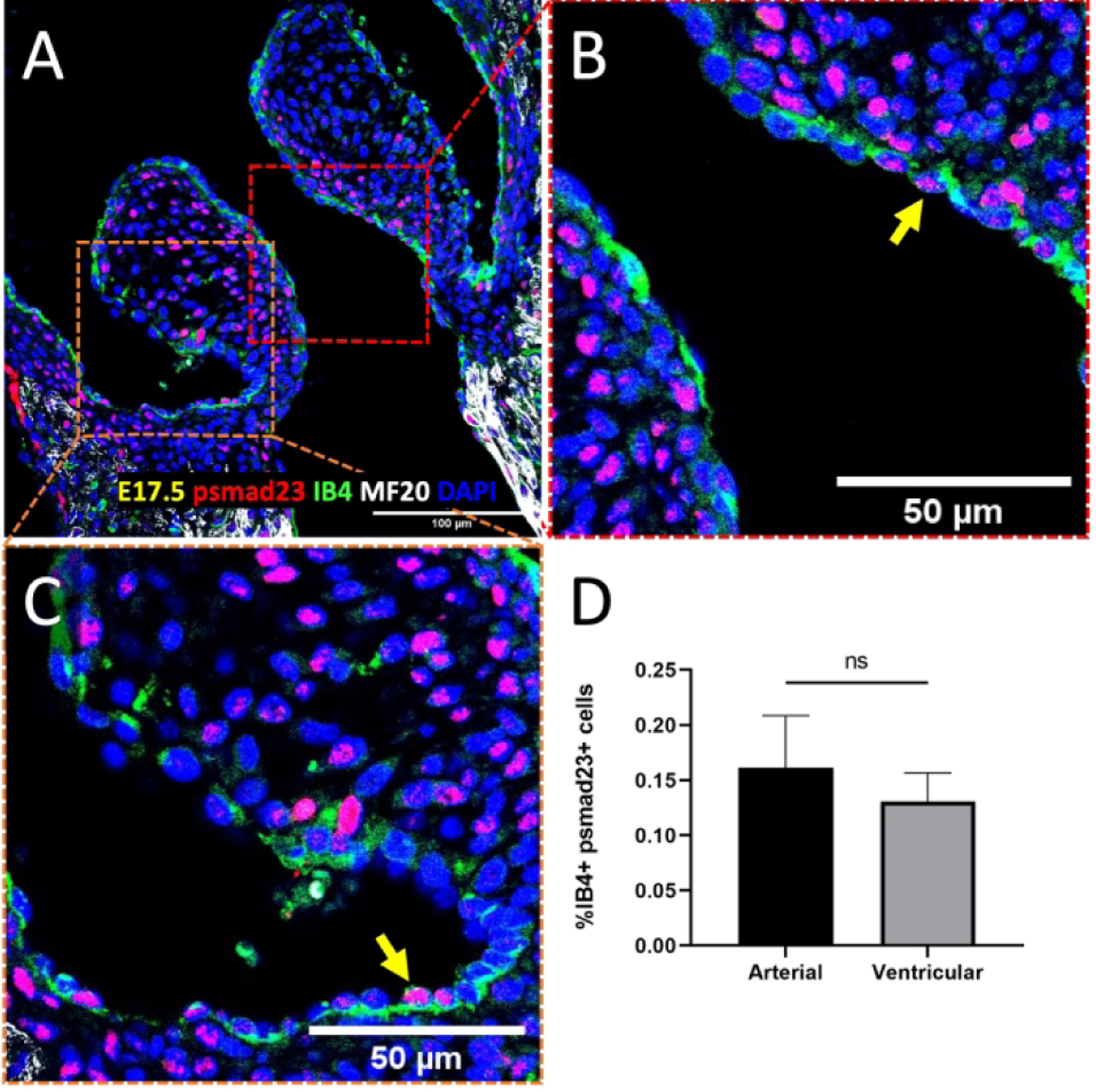

Figure 4.

No differential TGFβ expression in the semilunar valve endocardium. A-C, Immunostaining of phosphorylated Smad23 (pSmad2/3) in the semilunar valves at E17.5. Arrows indicate positive pSmad2/3 cells (red). Myocardial cells were stained with MF20 (white), while endocardial cells were stained with IB4 (green). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). D, Quantification of TGFβ signaling based on percentage of nuclear pSmad2/3 and IB4 double positive cells. Data are means ± SEM. n = 5 embryos per group. *p < 0.05 via Student t test. Scale bars indicate 100 μm, or 50 μm where indicated.

Shear stress pattern and magnitude controls BMP signaling in valve endocardium

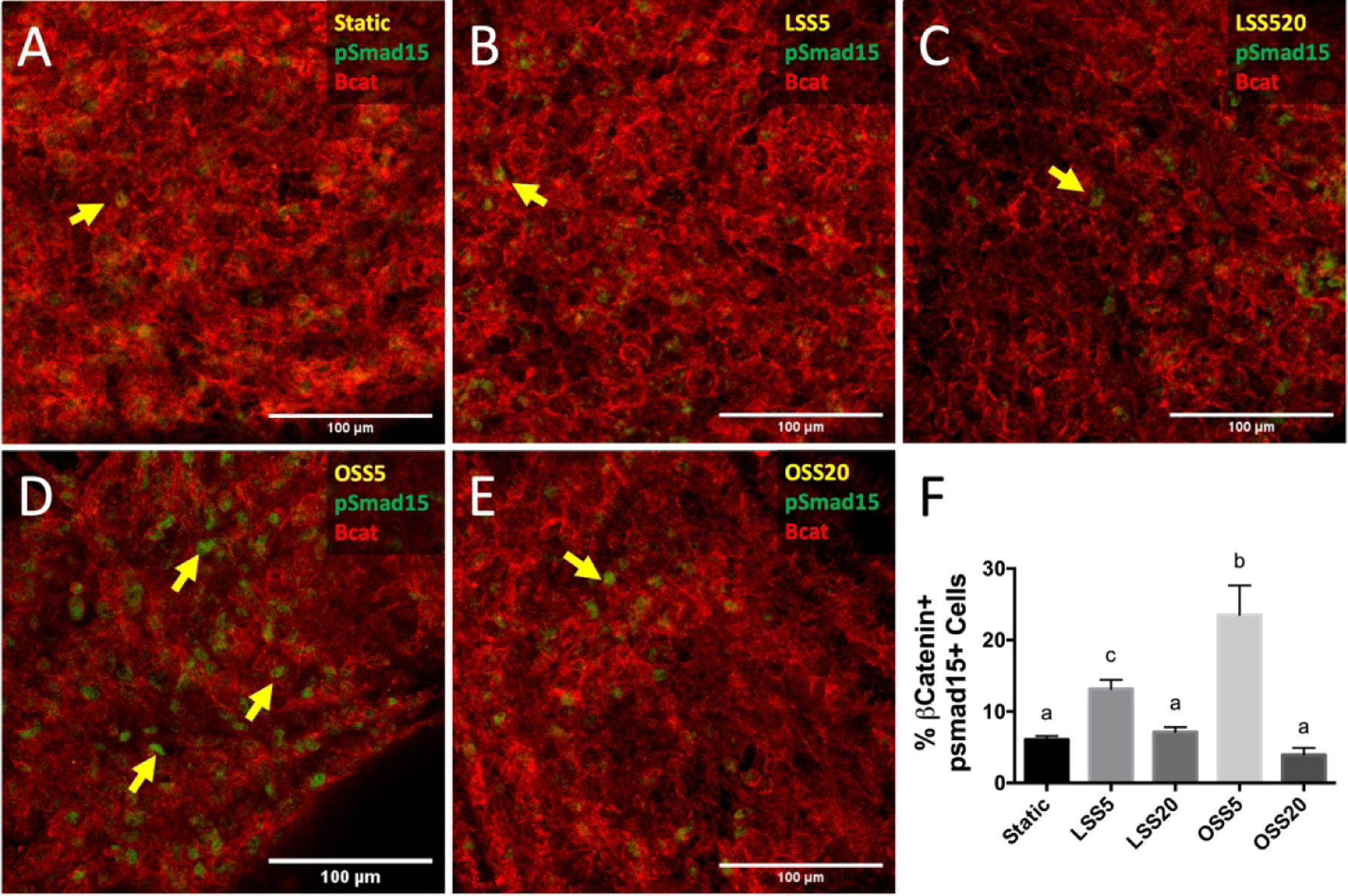

We next tested if BMP signaling, like proliferation, was activated by low OSS in endocardial cells. Endocardial cells exposed to OSS5 demonstrated a three-fold increase of pSmad1/5+ cells over the static control (Figures 5A and 5D), while both LSS20 and OSS20 conditions (Figures 5C and 5E) did not show any increase in BMP signaling, which is consistent with high shear inhibiting BMP signaling on the inflow side of the valve. Interestingly, BMP signaling also increased two-fold in cells exposed to LSS5.

Figure 5.

Enhanced BMP activation under low oscillatory shear. Immunostaining of phosphorylated Smad15 (pSmad1/5, green), indicative of active BMP signaling, in static (A), LSS at 5 dynes/cm2 (LSS5, B), LSS 20 dynes/cm2 (LSS20, C), OSS at 5 dynes/cm2 (OSS5, D), and OSS at 20 dynes/cm2 (OSS20, E). Endocardial cells were stained with β-catenin (red). Arrows indicate positive pSmad1/5 staining. F, Quantification of BMP activity based on percentage of endocardial cells positive for nuclear pSmad1/5. Data are means ± SEM. n ≥ 7 endocardial patches per group. Bars that do not share any letters are significantly different (p < 0.05 via ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparisons correction). Scale bars indicate 100 μm.

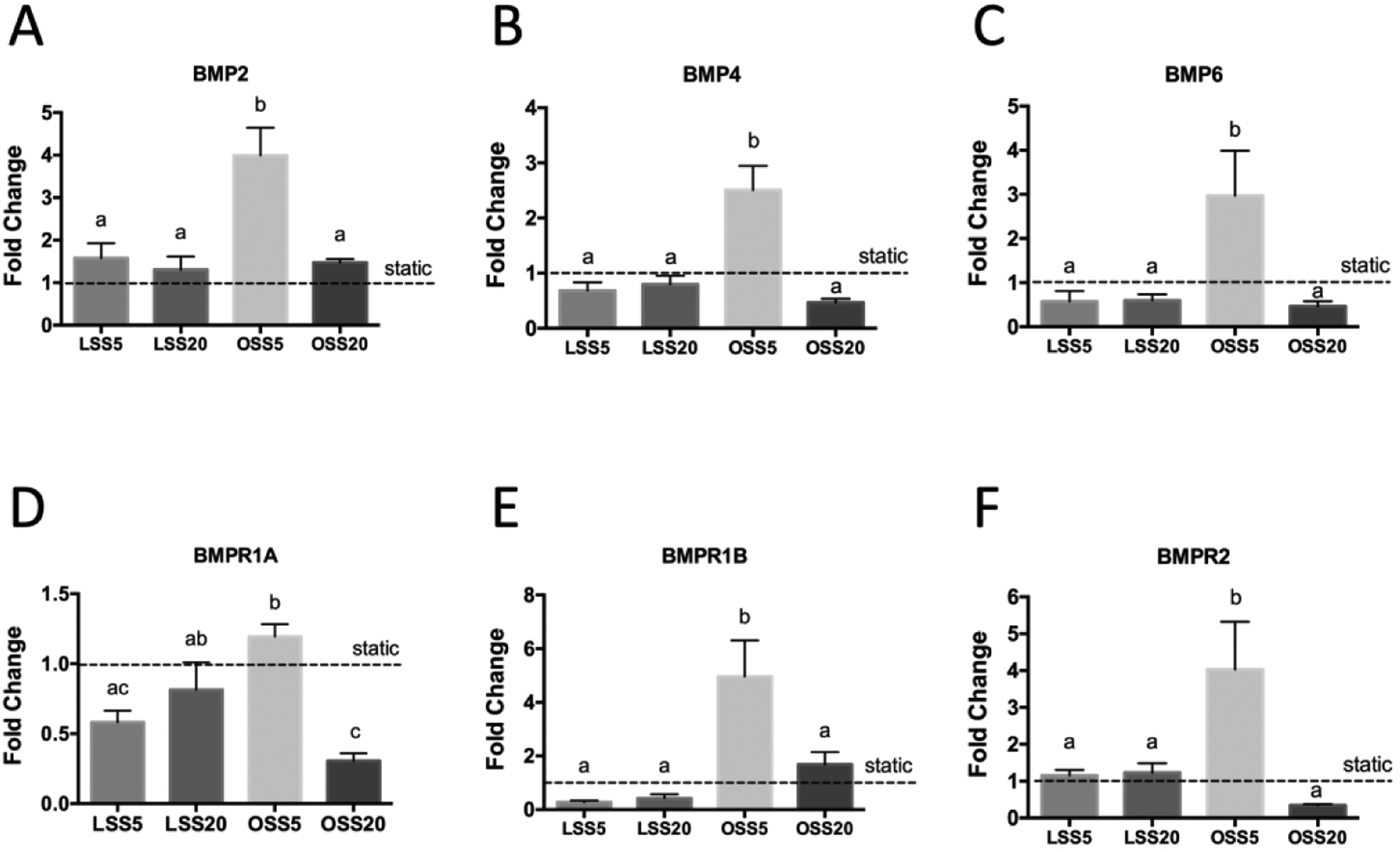

To identify the factors that underly the mechanism of BMP activation, we examined expression of the components of the BMP pathway in response to shear. qRT-PCR revealed expression of ligands BMP2, 4, and 6 were induced in response to OSS5 (Figures 7A–C). Furthermore, examination of BMP receptor type 1 (BMPR1A and BMPR1B) and type 2 (BMPR2) revealed that under the OSS5 condition, there was no significant increase of BMPR1A expression (Figure 7D); however, BMPR1B and BMPR2 expression both increased significantly (Figures 7E, F). These results corroborate low OSS activation of BMP signaling.

Figure 7.

Upregulation of BMP ligands and receptors in response to OSS5. Expression of BMP ligands (A-C) and receptors (D-F) in primary embryonic chick valve endocardial cells exposed to LSS5, LSS20, OSS5, and OSS20. Fold change was normalized to static controls. Data are means ± SEM. n = 5 endocardial patches per group. Bars that do not share any letters are significantly different (p < 0.05 via ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparisons correction).

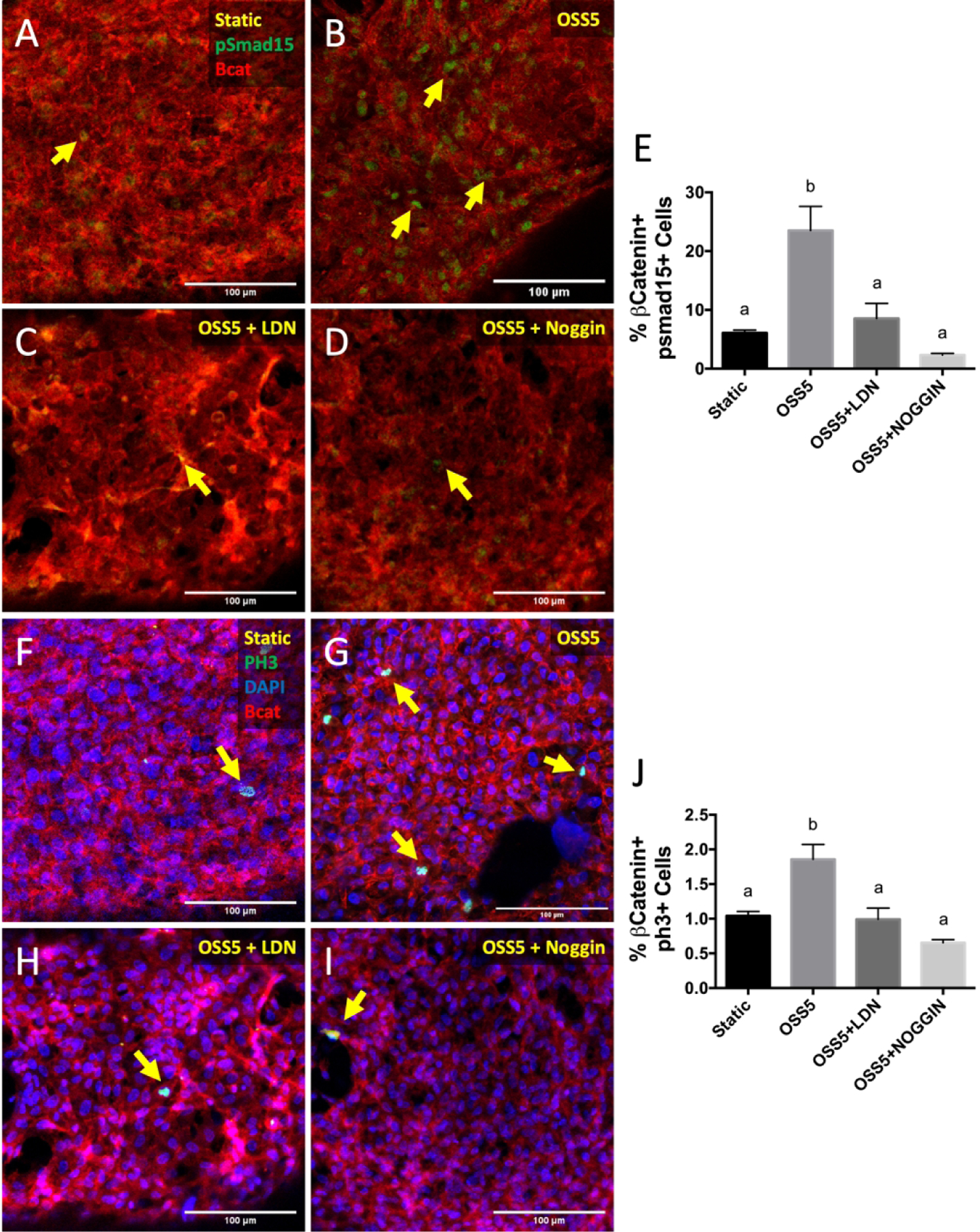

Ligand-dependent paracrine BMP signaling is required for OSS5-induced endocardial proliferation

Given the association between low OSS, proliferation and BMP signaling, we next determined whether BMP mediates shear-driven endocardial proliferation. While OSS5 significantly increases both BMP expression and proliferation (Figures 6B, G), addition of LDN193189, an inhibitor of BMP type I receptors (Alk2 and Alk3), completely blocked this effect (Figures 6C, E, H, J). Addition of Noggin, a BMP ligands scavenger, to the OSS5 condition likewise blocked activation BMP signaling, as well as proliferation (Figures 6D, I). Together, our results demonstrate that low OSS induces endocardial proliferation via BMP 2/4/6 ligand activation.

Figure 6.

Inhibition of BMP signaling downregulates endocardial proliferation under OSS5. Immunostaining of pSmad1/5 in static (A), OSS5 (B), OSS5 + LDN193189 (C), and OSS5 + Noggin (D) conditions. Endocardial cells were stained with β-catenin (red). E, Quantification of pSmad1/5 activity based on percentage of endocardial cells positive for nuclear pSmad1/5. Immunostaining of PH3 in static (F), OSS5 (G), OSS5 + LDN193189 (H), and OSS5 + Noggin (I). Yellow arrows indicate pSmad1/5+ cells. J, Quantification of PH3 activity based on percentage of endocardial cells positive for nuclear PH3. Data are means ± SEM. n ≥ 7 endocardial patches per group. Bars that do not share any letters are significantly different (p < 0.05 via ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparisons correction). Scale bars indicate 100 μm.

Canonical Wnt signaling is required for activation of BMP signaling by low OSS

As BMP signaling is not a known mechanotransduction pathway, we sought to identify a mediator between low OSS and BMP signaling. Previous studies have shown that members of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway are responsive to shear stress in adult endothelial cells.23 We therefore determined the effect of shear stress on canonical Wnt signaling by measuring nuclear β-catenin in endocardial cells exposed to various shear profiles. We found that Wnt signaling was significantly increased under OSS5 as compared to LSS5, LSS20, and OSS20 (Figure 8B).

Figure 8.

Enhanced canonical Wnt signaling on the outflow side of semilunar valves and under low oscillatory shear. A, a reproduction of Figure 2D, with arrows indicating nuclear β-catenin. B, Quantification of canonical Wnt Quantification of canonical Wnt signaling based on percentage of endocardial cells positive for nuclear β-catenin. Data are means ± SEM. n ≥ 5 endocardial patches per group. Bars that do not share any letters are significantly different (p < 0.05 via ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparisons correction). Scale bars indicate 100 μm, or 50 μm where indicated.

To determine if Wnt indeed mediated BMP activation via low OSS5, we treated cells under the OSS5 condition with XAV939. We found that this treatment blocked the increase of BMP expression by OSS5 (Figure 9D), revealing that Wnt signaling mediates the activation of BMP signaling via low OSS.

Figure 9.

Canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling mediates shear-induced regulation of BMP signaling. Immunostaining of pSmad1/5 in endocardial cells exposed to static (A), OSS5 (B), and OSS5 + XAV939 (C). Yellow arrows indicate pSmad1/5+ cells. D, Quantification of BMP activation based on percentage of endocardial cells positive for nuclear pSmad1/5. Data are means ± SEM. n ≥ 5 endocardial patches per group. Bars that do not share any letters are significantly different (p < 0.05 via ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparisons correction). Scale bars indicate 100 μm.

Notch signaling is required for modulation of BMP signaling and proliferation by high LSS

Additionally, we sought to identify a mechanosensory pathway that transduced hemodynamic signals from the inflow side of the valve to inhibit proliferation. Previous studies have shown that Notch expression increases in response to LSS in a dose-dependent manner in arterial endothelial cells.24,25 We found that in endocardial cells at E14.5 and E17.5, Notch1 signaling, measured by NICD expression, was five times higher on the ventricular side than the on arterial side of the semilunar valve (Figure 10D, H). Furthermore, subjecting endocardial cells to high LSS greatly increased Notch1 signaling (82%) as compared to any other flow condition, including static (1.6%, Figure 10N).

Figure 10.

Enhanced Notch signaling on the inflow side of semilunar valves and under high laminar shear. Immunostaining of NICD in the semilunar valves at E14.5 (A-C) and at E17.5 (E-G). Arrows indicate positive NICD cells (red). Myocardial cells were stained with MF20 (white), while endocardial cells were stained with IB4 (green). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). D, H, Quantification of Notch signaling based on percentage of nuclear NICD and IB4 double positive cells. Data are means ± SEM. n ≥ 6 embryos per group. *p < 0.05 via Student t test. Immunostaining of Notch1 (green), in static (I), LSS5 (J), LSS20 (K), OSS5 (L), and OSS20 (M). Arrows indicate nuclear Notch1. Endocardial cells were stained with β-catenin (red). N, Quantification of Notch activity based on percentage of endocardial cells positive for nuclear Notch1. Data are means ± SEM. n ≥ 6 endocardial patches per group. Bars that do not share any letters are significantly different (p < 0.05 via ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparisons correction). Scale bars indicate 100 μm, or 50 μm where indicated.

Given that Notch1 signaling was associated with the ventricular side of the semilunar valves, and induced by high LSS, we determined if Notch1 mediates the inhibition of proliferation via high LSS. We found that the addition of DAPT, an inhibitor of γ-secretase and pan-Notch signaling, to cells exposed to LSS20 caused a two-fold increase of Wnt signaling, BMP signaling, and proliferation as compared to the LSS20 condition alone (Figures 11G, H, and I, respectively), indicating that Notch mediates the downregulation of Wnt and its downstream targets, BMP and proliferation.

Figure 11.

Notch1 signaling mediates shear-induced regulation of proliferation. Immunostaining of PH3 in endocardial cells exposed to static (A), LSS20 (B), and LSS20 + DAPT (C) conditions. Yellow arrows indicate nuclear β-catenin, while green arrows indicate PH3+ cells. Immunostaining of pSmad1/5 in endocardial cells exposed to static (D), LSS20 (E), and LSS20 + DAPT (F) conditions. Yellow arrows indicate pSmad1/5+ cells. G-I, Quantification of canonical Wnt signaling, and BMP signaling, proliferation, based on percentage of endocardial cells positive for nuclear β-catenin, PH3, and pSmad1/5, respectively. Data are means ± SEM. n ≥ 7 endocardial patches per group. Bars that do not share any letters are significantly different (p < 0.05 via ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparisons correction). Scale bars indicate 100 μm.

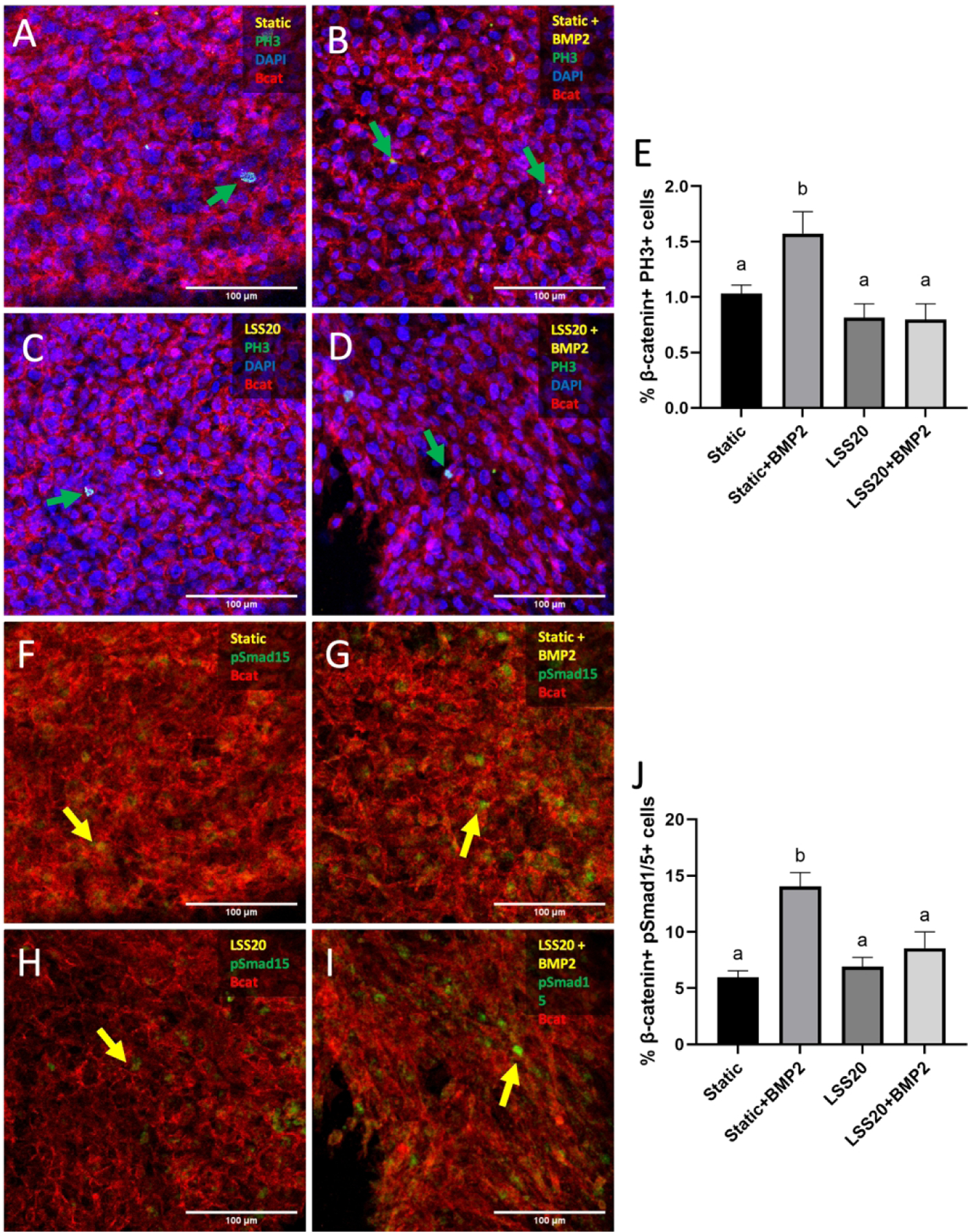

We further elucidated the potential interaction between Notch and BMP. We treated endocardial cells with BMP2 under static and LSS20 stimulation. Endocardial cells under static conditions exhibited significantly higher BMP signaling and proliferation compared to vehicle-treated controls. Interestingly, there was not a similar increase in BMP2-treated cells that were exposed to LSS20, suggesting that exogenous BMP2 administration could not counteract LSS20-induced inhibition of BMP signaling and endocardial proliferation (Figures 12E, J). Together, our results show that LSS inhibits proliferation through Notch1, which antagonizes Wnt signaling as well as its downstream target, BMP signaling.

Figure 12.

BMP2 treatment cannot rescue BMP signaling and proliferation phenotypes under LSS20. Immunostaining of PH3 in endocardial cells exposed to static (A), LSS20 (B), LSS20 + BMP2 (C), and Static + BMP2 (D) conditions. Green arrows indicate PH3+ cells. E, Quantification of endocardial proliferation based on percentage of endocardial cells positive for nuclear PH3. Immunostaining of pSmad1/5 in endocardial cells exposed to static (F), LSS20 (G), LSS20 + BMP2 (H), and Static + BMP2 (I) conditions. Yellow arrows indicate pSmad1/5+ cells. J, Quantification of endocardial proliferation based on percentage of endocardial cells positive for nuclear pSmad1/5. Data are means ± SEM. n ≥ 7 endocardial patches per group. Bars that do not share any letters are significantly different (p < 0.05 via ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparisons correction). Scale bars indicate 100 μm.

Discussion

Congenital heart defects arise due to deviation from the genetic and/or hemodynamic programs that normally drive development. Although early valve development, including EndMT, is well understood, mid-gestation valve morphogenesis remains elusive. Later stages are clinically relevant to congenital heart defects, yet there still are large gaps in our knowledge due to the difficulties of studying later development with genetic-focused inquiries. Our study investigates hemodynamic forces as the coordinator of cellular processes that give rise to the semilunar shape of the OFT valves. Through an integrated array of in vivo assays and in vitro investigations, we demonstrated a novel mechanobiological regulatory program that transduces side-specific hemodynamic information into differential endocardial growth, wherein low-magnitude OSS promotes endocardial cell proliferation, while high-magnitude LSS inhibits it. On the outflow side, low OSS activates Wnt signaling, which in turn upregulates BMP signaling and subsequent proliferation. On the inflow side, high LSS induces Notch signaling, which inhibits both Wnt and BMP signaling pathways, thereby downregulating proliferation.

In this study, we determined how the distal margins of the valve cushions thin and elongate, a process often called excavation, the mechanism and regulation of which was previously unknown.26–28 We determined that endocardial proliferation is higher on the arterial surface on the valve, a pattern that is supported by image data in previous studies but not reported.17,29 Our results lead to a hypothesis of extension, in which hemodynamic cues preferentially induce endocardial proliferation on the arterial surface of the semilunar valves, causing the arterial side to lengthen. As the arterial side lengthens, the valve extends in the direction of blood flow. Mechanical coordination provides tunability to this process, as hemodynamic inputs will converge as valves develop, which could help explain how valves can develop morphologically to be suitable for outflow tracts of different sizes and to conform to cardiac output and vascular resistance needs. This extension model could also explain why defective endocardial proliferation programs, e.g., VEGF, BMP, Nfatc1 result in nonelongated valve leaflets.30–32 Our data suggest that endocardial growth and lengthening is a driving factor for elongation, while recent studies have attributed abnormal valve remodeling to aberrant regulation of mesenchymal cell proliferation. Furthermore, our model (abstract figure) establishes a functional coordination between shear stress and regulation of the side-specificity of endocardial proliferation and valve extension, predicting that any manipulation of hemodynamics may result in a defective valve.

The leaflets of the semilunar valves may experience different regulation due to cell lineage or exposure to different shear stresses. While valve endocardial cells likely are from the same lineage,32,33 valve mesenchymal cells can derive from different lineages.34 While differential mesenchymal makeup of the leaflets could cause them to respond differently to hemodynamic stresses or endocardial paracrine signals, it is unlikely to manifest in late morphological differences. Lineage ablation studies demonstrate that the incidence of malformation is marginal for conditional knockouts after E12.5,35,36 suggesting that mesenchymal cell lineages are more essential for proper initial cushion formation than subsequent morphogenesis. Differential shear profiles, however, may give rise to slight variation in the regulation of the leaflets. While all three leaflets experience OSS on the arterial surface during ventricular systole, during ventricular systole, the arterial surface of the coronary leaflets are thought to experience some LSS during ventricular diastole.37 Clinically, echocardiographic data collected from patients showed that the non-coronary cusp thickens first.38

At the molecular level, we establish that the oscillatory shear-driven upregulation of proliferation is dependent on BMP ligands. Specifically, BMP2/4/6 ligands are upregulated by low-magnitude shear stress, which corroborates in vivo presence of BMP2/4/6 on the outflow surface of the OFT valves10. This is in contrast with the zebrafish, in which BMP and blood flow are both essential contributors to endocardial cell proliferation during early cardiogenesis, but BMP activity is independent of blood flow.39 The direct relationship between BMP and proliferation we demonstrated can also help elucidate why Smad6 and Noggin knockouts exhibit hyperplastic cardiac valves,40,41 as loss of the BMP inhibitors causes aberrant BMP signaling and upregulation of endocardial proliferation. In terms of specific ligands, BMP2 endocardial knockouts exhibit reduced proteoglycans and periostin,42 suggesting that flow-induced endocardial BMP2 is required for valve maturation. Anterior heart field BMP4 knockouts have valves that are reduced in size at E12.5.30 Interestingly, the study reported no difference in cushion cell proliferation or apoptosis but did not measure endocardial-specific proliferation. Our data suggests that BMP4-regulated endocardial proliferation may have been reduced, restricting the overall size of the valve.

The BMP pathway is not known to be mechanosensory, which motivated the search for upstream regulators of inhibition and activation of BMP signaling. We identified that Wnt signaling through β-catenin is shear-sensitive and required for OSS-induced BMP activation and endocardial proliferation. Wnt4 and Wnt9b are ligands that are potentially involved in this axis, as it has been previously shown that these ligands are downregulated in endocardial Tbx20 knockouts, and these knockouts also have reduced endocardial proliferation and unelongated valves,29 which is consistent with our model of extension. Our results demonstrate that ventricular valve endocardial cells are able to respond to low-magnitude OSS by upregulating proliferation and BMP signaling. This is in contrast to their behavior in the context of EMT, wherein the cells do not respond.43

Both BMP and Wnt singaling have been implicated in valve calcification processes.44–46 Computational assessment of hemodynamic forces in bicuspid aortic valve (BAV) have shown that the base of the fused BAV leaflets experiences increased pulsatility and is associated with calcification.47 Furthermore, ex-vivo exposure of porcine aortic valve endothelial cells to unidirectional pulsatile shear stress upregulated proinflammatory genes, including BMP, while OSS did not.48 In light of these findings, it is conceivable that the altered shear stresses experienced by the valves due to certain BAV morphologies initiate the inflammatory milieu that leads to valve calcification.

We further identified that Notch1 mediates the downregulation of proliferation by high laminar shear. Previous studies have shown that laminar shear stress upregulates Notch signaling in endothelial cells in a stepwise manner.24,25 Our results demonstrate this behavior in endocardial cells as well, as endocardial cells exposed to LSS20 expressed higher levels of nuclear Notch than those of cells exposed to LSS5. We also showed that Notch1 antagonizes BMP signaling, and as LSS and BMP2 treatment did not affect rate of pSmad1/5 expression or proliferation (Figure 12), this would suggest that Notch may attenuate BMP signaling by (1) downregulating BMP receptors, (2) interacting with BMP intracellular signaling pathways, or (3) scavenging BMP ligands. The LSS20 condition downregulates BMPR2 and BMPR1B (Figure 7), which is consistent with such an assessment. This interaction may alternatively be mediated through Smad6, a BMP inhibitor that is upregulated by Notch signaling in HUVECs.49 Additionally, Notch-induced HEY1, HEY2, and HEYL have been shown to downregulate BMP2 expression in the endocardium of the AVC and ventricular chambers during EndMT.50

Interestingly, we found that Notch1 does not affect proliferation in the endocardial valves at E14.5.13 This discrepancy may be explained as the study focused on endocardial regulation of mesenchymal cells and did not consider the two different surfaces of the valve separately. Finally, our results demonstrate that Notch interacts with Wnt and BMP differently during fetal remodeling than during early EndMT. Whereas Notch downregulates Wnt and BMP in endocardial cells during remodeling, Notch upregulates endocardial Wnt and myocardial BMP expression.9

While XAV939 inhibits propagation of Wnt signaling by promoting the degradation of β-catenin,51 it also known to inhibit Yap signaling.52 The role of Yap signaling in valve morphogenesis is not known. Endocardial-specific deletion of Yap impaired EMT in early valves.53 In cardiomyocytes, deletion of Yap inhibitor Salv led to increased canonical Wnt signaling.54 Yap/Taz is also required for BMP signaling in endothelial cells.55 These reports suggest that Yap may also interact with Wnt to coordinate BMP signaling in valve growth, in particular under different conditions, but more research is necessary to elaborate these roles.

In conclusion, we identify that local hemodynamic signaling potentiates valve growth decisions through operation of the Wnt/Notch molecular switch. Low oscillatory shear stress promotes endocardial proliferation on the arterial surface, while high laminar shear stress restricts it on the ventricular surface of the valve. This switch is controlled not through genetics, but through the flow environments effected by the growing valve, which is sufficient to explain how valves grow in proportion to hemodynamic needs as well as overall outlet size. An interesting observation is that the OSS20 condition downregulates both BMP ligands and receptors. This suggests a hypothesis in which high-magnitude shear that is associated with late-stage valve development could signal the completion of valve remodeling and shut down the Wnt/BMP signaling framework. As the heart grows, the fluid shear stresses it generates increase, decreasing the strength of the proliferation program on the arterial surface of the valve, eventually turning the program off. This is consistent with the rate of proliferation on the arterial side of the valve, which steadily decreases from E13.5 to E18.5 (Figure 1). Moreover, the tip of the valve, at the interface between OSS and LSS, may experience compressive mechanical forces different from either the arterial or ventricular surfaces. How these hemodynamic microenvironments contribute to the regulation of the molecular program requires additional investigation. Further studies to uncover how hemodynamic cues orchestrate underlying biomolecular mechanisms can advance our knowledge on how developmental pathways initiate and conclude the valve remodeling process, resulting in a functional morphology.

Experimental Procedures

Measurement of valve extension

Serial sections across the entire OFT were taken, and length measurements done only on the section with the largest leaflet cross-section. The point of the leaflet that extended farthest in the arterial direction demarcated the point between arterial and ventricular sides. Length measurements of both sides were done in ImageJ.

Measurement of endocardial protein expression

Quantification of endocardial protein expression was determined in vivo via staining of paraffin sections of isolated hearts, and in vivo by staining of endocardial patches. They were stained for the appropriate protein, an endocardial marker, and counterstained with DAPI. The endocardial marker used was IB4 in vivo and β-catenin in vitro. A cell positive for the protein and expressing the endocardial marker along its periphery was considered as a positive endocardial cell, whereas a cell having only the endocardial marker was considered a negative endocardial cell. Arterial and ventricular endocardial cells were distinguished in vivo by the same method as that of valve lengths.

Shear stress bioreactor system

The bioreactor consists of a histology microscope slide, biocompatible double-sided tape (W.W. Grainger), 5mm-thick silicone sheet (McMaster-Carr), and a sticky-Slide I Luer (Ibidi). 4 mm diameter wells were created in the silicone sheet. The components of the bioreactor were clamped together using binder clips. The female Luers of the channel slide were connected to silicone tubing that had a 3.2mm inner diameter (Size 16, Cole-Parmer). Flow was generated for both steady and oscillatory shear experiments as previously described.56 Endocardial cells on the inflow side experience high LSS averaging about 20 dyne/cm2,57,58 whereas those on the outflow side experience low OSS which peaks around 21.3 dyne/cm2.56,59,60 Flow rates were therefore calculated using the height of the channel slides to create shear stresses of 5 dyne/cm2 and 20 dyne/cm2. For oscillatory shear experiments, cells were exposed to shear stress in the forward direction for one-half of a one-second cycle and in the reverse direction for the other half of the cycle. Experiments were run for 24 h at 37°C and 5% CO2 within an incubator.

3D endocardial cell culture

Collagen gels at a concentration of 2 mg/mL collagen were made by mixing 3x Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (Life Technologies), 10% chick serum (Life Technologies), sterile 18 MΩ water, 0.1 M NaOH, and rat tail collagen I (BD Biosciences). An aliquot of the collagen gel solution was pipetted into the wells in the silicone sheet and allowed to solidify for 1 hour at 37C and 5% CO2. The dissected outflow tracts were then placed on top of the collagen gel. After 6 hours of incubation at 37°C and 5% CO2, the valve endocardial cells were repolarized, delaminated, and attached to the surface of the collagen constructs.

To inhibit BMP signaling, LDN189193, an Alk2/3 inhibitor (1μM, Sigma), and Noggin, a BMP ligand scavenger (100ng/mL, Sigma) were used, while DAPT was used to inhibit Notch signaling (10μM, Sigma). To inhibit canonical Wnt signaling, XAV939 (1μM, Sigma) was diluted in DMSO. The endocardial patches were conditioned with media containing the inhibitor for 1 hour prior to the shear stress experiments. Cells were then exposed to media containing the same concentrations of inhibitors during the shear experiments.

Animal samples

Embryonic hearts were harvested from wildtype mouse embryos at E12.5, E13.5, E16.5, and E18.5 in cold PBS. The outflow tracts were then isolated and fixed in cold paraformaldehyde and processed for wholemount immunostaining. For shear stress experiments, fertilized White Leghorn eggs were incubated at 38C and 80% humidity to Hamburger-Hamilton (HH) stage 33+ (Day 7–8, incubational age). Chick embryos were then harvested in cold EBSS (Sigma). Outflow tracts were then isolated and dissected to expose valve primordia, which were then used to generate 3D collagen constructs with endocardial cells seeded on top.

Immunostaining

Samples were fixed with cold 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes, subsequently washed with TBS, permeabilized with 0.3% Triton-X 100 for 20 minutes and washed again in TBS for 2×10 minutes. Samples were then blocked and subsequently incubated with primary antibodies in the blocking solution overnight at 4C. The primary antibodies used were PHH3 (1:200; Abcam, ab10543), MF20 (1:100; Thermo Fisher, 14-6503-82), pSmad1/5 (1:100; Cell Signaling, 9516S), and mouse mAb against β-catenin (1:100; BD Biosciences; 610154). Samples were then washed for 3×10 minutes with TBS and incubated with species-specific Alexa Fluor® 488, 568, or 647 conjugated secondary antibodies in 5% BSA diluted in TBS for 1 hour at room temperature. Samples were then washed again for 3×10 minutes and stained with DAPI. For pSmad1/5 staining, samples were incubated with a donkey-anti rabbit secondary antibody conjugated with HRP. Fluorescence signal was amplified using TSA Amplification Kit (Perkin Elmer) and washed in TBS before staining with DAPI. Images were taken using Zeiss LSM880 Confocal/Multiphoton Upright Microscope (u880).

Gene expression analysis

Total RNA was extracted from endocardial cells on the surface of the 3D collagen gels using Power SYBR™ Green Cells-to-CT™ Kit (Thermo Fisher). The kit was also used to synthesize cDNA was then synthesized from the extracted RNA. Each gel represents a biological replicate, which pools RNA from 2 endocardial patches. qRT-PCR was performed on samples using reagents from the same kit and MiniOpticon Real-Time PCR Detection System (Biorad, Hercules, CA). Primers are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

List of chicken primers used in gene expression analysis.

| GAPDH | F 5′ TATGATGATATCAAGAGGGTAGT 3′ R 5′ TGTATCCAAACTCATTGTCATAC 3′ |

| BMP2 | F 5′ CCAGCTGTTTTGAGGTGGAT 3′ R 5′ ATACAACGGATGCCTTTTGC 3′ |

| BMP4 | F 5′ CCTGGTAACCGAATGCTGAT 3′ R 5′ CTCCTCCTCTTCTTCGGACT 3′ |

| BMP6 | F 5′ TCTTCACGTGGACTCTGTGG 3′ R 5′ TTAAGACCATCCCAGCCAAG 3′ |

| BMPRII | F 5′ GCTACCTCGAGGAGACCATTACA 3′ R 5′ CATTGCGGCTGTTCAAGTCA 3′ |

| BMPR1A | F 5′ TGTCACAGGAGGTATTGTTGAAGAG 3′ R 5′ AAGATGGATCATTTGGCACCAT 3′ |

| BMPR1B | F 5′ GGGAGATAGCCAGGAGATGTGT 3′ R 5′ GGTCGTGATATGGGAGCTGGTA 3′ |

Statistics

Graphs display mean values ± standard error. Data was analyzed using GraphPad Prism 6.0 for Mac. Results were analyzed by two-way Student t-test or one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Differences between means were significant at P<0.05.

Acknowledgements

Imaging data was acquired through the Cornell Institute of Biotechnology’s Imaging Facility, with NIH 1S10OD010605 funding for the shared Zeiss LSM710 Confocal and Zeiss LSM880 Confocal multiphoton inverted microscopes.

Funding statement:

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (CMMI-1635712); and the National Institutes of Health (HL128745, HL143247).

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors declare no competing or financial interests.

References

- 1.Moodie D Adult Congenital Heart Disease. Tex Heart Inst J 38, 705–706 (2011). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoffman JIE & Kaplan S The incidence of congenital heart disease. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 39, 1890–1900 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van der Linde D et al. Birth Prevalence of Congenital Heart Disease Worldwide. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 58, 2241–2247 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferencz C et al. Congenital cardiovascular malformations associated with chromosome abnormalities: An epidemiologic study. The Journal of Pediatrics 114, 79–86 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Butcher JT & Markwald RR Valvulogenesis: the moving target. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 362, 1489–1503 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jain R et al. Cardiac neural crest orchestrates remodeling and functional maturation of mouse semilunar valves. J Clin Invest 121, 422–430 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Combs MD & Yutzey KE Heart Valve Development. Circulation Research 105, 408–421 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garside VC, Chang AC, Karsan A & Hoodless PA Co-ordinating Notch, BMP, and TGF-β signaling during heart valve development. Cell. Mol. Life Sci 70, 2899–2917 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang Y et al. Endocardial to Myocardial Notch-Wnt-Bmp Axis Regulates Early Heart Valve Development. PLoS One 8, (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Somi S, Buffing AAM, Moorman AFM & Hoff MJBVD Dynamic patterns of expression of BMP isoforms 2, 4, 5, 6, and 7 during chicken heart development. The Anatomical Record Part A: Discoveries in Molecular, Cellular, and Evolutionary Biology 279A, 636–651 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bosada FM, Devasthali V, Jones KA & Stankunas K Wnt/β-catenin signaling enables developmental transitions during valvulogenesis. Development 143, 1041–1054 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Monte GD, Grego-Bessa J, González-Rajal A, Bolós V & Pompa JLDL Monitoring Notch1 activity in development: Evidence for a feedback regulatory loop. Developmental Dynamics 236, 2594–2614 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Y et al. Notch-Tnf signalling is required for development and homeostasis of arterial valves. Eur Heart J 38, 675–686 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hofmann JJ et al. Endothelial deletion of murine Jag1 leads to valve calcification and congenital heart defects associated with Alagille syndrome. Development 139, 4449–4460 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.MacGrogan D et al. Sequential Ligand-Dependent Notch Signaling Activation Regulates Valve Primordium Formation and Morphogenesis. Circulation Research 118, 1480–1497 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Norris RA et al. Periostin regulates atrioventricular valve maturation. Developmental Biology 316, 200–213 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Y et al. Myocardial β-Catenin-BMP2 signaling promotes mesenchymal cell proliferation during endocardial cushion formation. J Mol Cell Cardiol 123, 150–158 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goddard LM et al. Hemodynamic Forces Sculpt Developing Heart Valves through a KLF2-WNT9B Paracrine Signaling Axis. Developmental Cell 43, 274–289.e5 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liebner S et al. β-Catenin is required for endothelial-mesenchymal transformation during heart cushion development in the mouse. Journal of Cell Biology 166, 359–367 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Midgett M & Rugonyi S Congenital heart malformations induced by hemodynamic altering surgical interventions. Front. Physiol 5, (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guo L et al. Dynamic Expression Profiles of β-Catenin during Murine Cardiac Valve Development. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease 7, 31 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de la Pompa JL & Epstein JA Coordinating Tissue Interactions: Notch Signaling in Cardiac Development and Disease. Developmental Cell 22, 244–254 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abuammah A et al. New developments in mechanotransduction: Cross talk of the Wnt, TGF-β and Notch signalling pathways in reaction to shear stress. Current Opinion in Biomedical Engineering 5, 96–104 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Driessen RCH et al. Shear stress induces expression, intracellular reorganization and enhanced Notch activation potential of Jagged1. Integrative Biology 10, 719–726 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mack JJ et al. NOTCH1 is a mechanosensor in adult arteries. Nature Communications 8, 1620 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dupuis LE, Osinska H, Weinstein MB, Hinton RB & Kern CB Insufficient versican cleavage and Smad2 phosphorylation results in bicuspid aortic and pulmonary valves. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology 60, 50–59 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hurle JM, Colveé E & Blanco AM Development of mouse semilunar valves. Anat Embryol (Berl) 160, 83–91 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Soto-Navarrete MT, López-Unzu MÁ, Durán AC & Fernández B Embryonic development of bicuspid aortic valves. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases 63, 407–418 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cai X et al. Tbx20 acts upstream of Wnt signaling to regulate endocardial cushion formation and valve remodeling during mouse cardiogenesis. Development 140, 3176–3187 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCulley DJ, Kang J-O, Martin JF & Black BL BMP4 is required in the anterior heart field and its derivatives for endocardial cushion remodeling, outflow tract septation, and semilunar valve development. Developmental Dynamics 237, 3200–3209 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stankunas K, Ma GK, Kuhnert FJ, Kuo CJ & Chang C-P VEGF signaling has distinct spatiotemporal roles during heart valve development. Developmental Biology 347, 325–336 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu B et al. Nfatc1 Coordinates Valve Endocardial Cell Lineage Development Required for Heart Valve Formation. Circulation Research 109, 183–192 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou B et al. Characterization of Nfatc1 regulation identifies an enhancer required for gene expression that is specific to pro-valve endocardial cells in the developing heart. Development 132, 1137–1146 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peterson JC et al. Bicuspid aortic valve formation: Nos3 mutation leads to abnormal lineage patterning of neural crest cells and the second heart field. Disease Models & Mechanisms 11, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eley L et al. A novel source of arterial valve cells linked to bicuspid aortic valve without raphe in mice. eLife 7, e34110 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Henderson DJ, Eley L & Chaudhry B New Concepts in the Development and Malformation of the Arterial Valves. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease 7, 38 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bäck M, Gasser TC, Michel J-B & Caligiuri G Biomechanical factors in the biology of aortic wall and aortic valve diseases. Cardiovascular Research 99, 232–241 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cujec B & Pollick C Isolated Thickening of One Aortic Cusp: Preferential Thickening of the Noncoronary Cusp. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography 1, 430–432 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dietrich A-C, Lombardo VA, Veerkamp J, Priller F & Abdelilah-Seyfried S Blood Flow and Bmp Signaling Control Endocardial Chamber Morphogenesis. Developmental Cell 30, 367–377 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Choi M, Stottmann RW, Yang Y-P, Meyers EN & Klingensmith J The Bone Morphogenetic Protein Antagonist Noggin Regulates Mammalian Cardiac Morphogenesis. Circulation Research 100, 220–228 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Galvin KM et al. A role for Smad6 in development and homeostasis of the cardiovascular system. Nature Genetics 24, 171–174 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saxon JG et al. BMP2 expression in the endocardial lineage is required for AV endocardial cushion maturation and remodeling. Developmental Biology 430, 113–128 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Faure E et al. Side-dependent effect in the response of valve endothelial cells to bidirectional shear stress. International Journal of Cardiology 323, 220–228 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Simmons CA, Grant GR, Manduchi E & Davies PF Spatial Heterogeneity of Endothelial Phenotypes Correlates With Side-Specific Vulnerability to Calcification in Normal Porcine Aortic Valves. Circulation Research 96, 792–799 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gomez-Stallons MV, Wirrig-Schwendeman EE, Hassel KR, Conway SJ & Yutzey KE Bone Morphogenetic Protein Signaling Is Required for Aortic Valve Calcification. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology 36, 1398–1405 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Khan K et al. The Role of Wnt/β-Catenin Pathway Mediators in Aortic Valve Stenosis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol 8, (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sabet HY, Edwards WD, Tazelaar HD & Daly RC Congenitally Bicuspid Aortic Valves: A Surgical Pathology Study of 542 Cases (1991 Through 1996) and a Literature Review of 2,715 Additional Cases. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 74, 14–26 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sucosky P, Balachandran K, Elhammali A, Jo H & Yoganathan AP Altered Shear Stress Stimulates Upregulation of Endothelial VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 in a BMP-4– and TGF-β1–Dependent Pathway. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology 29, 254–260 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mouillesseaux KP et al. Notch regulates BMP responsiveness and lateral branching in vessel networks via SMAD6. Nature Communications 7, 13247 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Luna-Zurita L et al. Integration of a Notch-dependent mesenchymal gene program and Bmp2-driven cell invasiveness regulates murine cardiac valve formation. J Clin Invest 120, 3493–3507 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huang S-MA et al. Tankyrase inhibition stabilizes axin and antagonizes Wnt signalling. Nature 461, 614–620 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang W et al. Tankyrase inhibitors target YAP by stabilizing angiomotin family proteins. Cell Rep 13, 524–532 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang H et al. Yap1 Is Required for Endothelial to Mesenchymal Transition of the Atrioventricular Cushion *. Journal of Biological Chemistry 289, 18681–18692 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Heallen T et al. Hippo Pathway Inhibits Wnt Signaling to Restrain Cardiomyocyte Proliferation and Heart Size. Science 332, 458–461 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Uemura M, Nagasawa A & Terai K Yap/Taz transcriptional activity in endothelial cells promotes intramembranous ossification via the BMP pathway. Sci Rep 6, 27473 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mahler GJ, Frendl CM, Cao Q & Butcher JT Effects of shear stress pattern and magnitude on mesenchymal transformation and invasion of aortic valve endothelial cells. Biotechnology and Bioengineering 111, 2326–2337 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nandy S & Tarbell JM Flush mounted hot film anemometer measurement of wall shear stress distal to a tri-leaflet valve for Newtonian and non-Newtonian blood analog fluids. Biorheology 24, 483–500 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Weston MW, LaBorde DV & Yoganathan AP Estimation of the Shear Stress on the Surface of an Aortic Valve Leaflet. Annals of Biomedical Engineering 27, 572–579 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Butcher JT, Simmons CA & Warnock JN Mechanobiology of the aortic heart valve. J Heart Valve Dis 17, 62–73 (2008). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yap CH, Saikrishnan N, Tamilselvan G & Yoganathan AP Experimental measurement of dynamic fluid shear stress on the aortic surface of the aortic valve leaflet. Biomech Model Mechanobiol 11, 171–182 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]