Abstract

Extended synaptotagmins (E-Syts) mediate lipid exchange between the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and the plasma membrane (PM). Anchored on the ER, E-Syts bind the PM via an array of C2 domains in a Ca2+- and lipid-dependent manner, drawing the two membranes close to facilitate lipid exchange. How these C2 domains bind the PM and regulate the ER-PM distance have not been well understood. Here, we applied optical tweezers to dissect PM membrane binding by E-Syt1 and E-Syt2. We detected Ca2+- and lipid-dependent membrane binding kinetics of both E-Syts and determined the binding energies and rates of individual C2 domains or pairs. We incorporated these parameters in a theoretical model to recapitulate salient features of E-Syt-mediated membrane contacts observed in vivo, including their equilibrium distances and probabilities. Our methods can be applied to study other proteins containing multiple membrane-binding domains linked by disordered polypeptides.

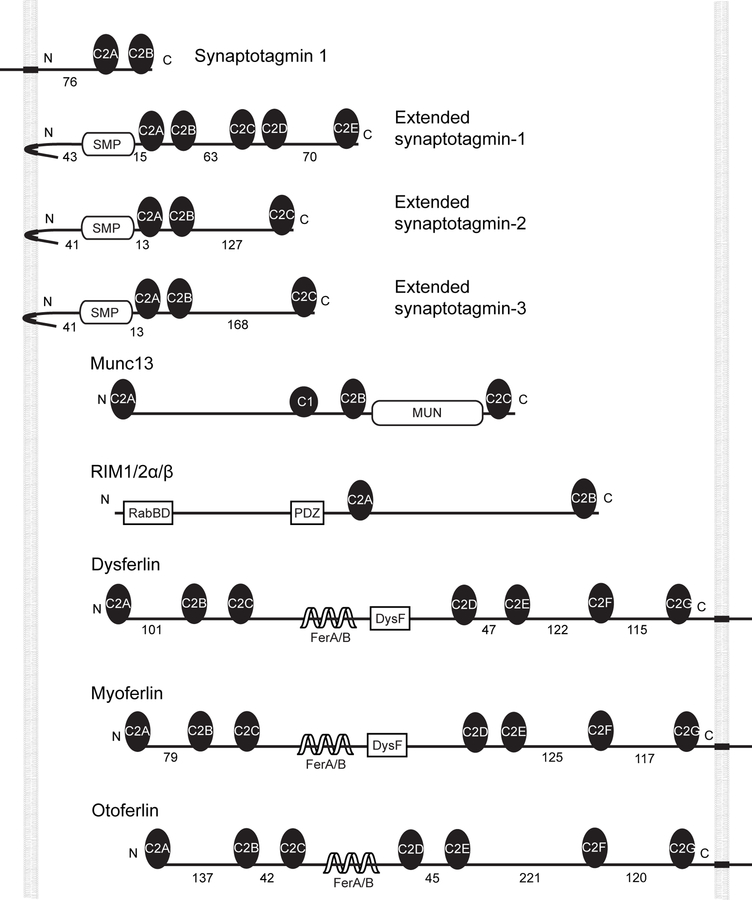

C2 domains are one of the most abundant membrane binding domains, with more than 200 members encoded by human genomes, and participate in numerous biological processes1–3. They show diverse affinities for different phospholipids in either Ca2+-dependent or Ca2+-independent manner. In addition, C2 domains often associate with one another or other protein domains4,5. Interestingly, multiple C2 domains are found in a variety of integral membrane proteins, especially those involved in membrane tethering leading to fusion or lipid exchange3,6–8. These C2 domains often form an array containing two to six C2 domains connected by disordered polypeptides of varying lengths ranging from 5 up to 200 amino acids (Extended Data Fig. 1). These proteins include the synaptotagmins that participate in regulated exocytosis3. They also include other proteins thought to participate in membrane fusion such as otoferlin, myoferlin, and dysferlin6,9, as well as the extended synaptotagmins (E-Syts) that mediate lipid exchanges between the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and the plasma membrane (PM) without bilayer fusion8,10–14. The biological functions and working mechanisms of many of these proteins have not been well characterized. However, it has been shown that C2 repeats are essential for their functions. In many cases, C2 domains in their cytosolically exposed region recognize and bind distinct lipids in another membrane, drawing the two membranes close in a Ca2+-dependent manner to regulate lipid exchange or membrane fusion. Although many methods are available to study membrane binding of isolated C2 domains or domain pairs15,16, it remains challenging to quantify the interactions between C2 repeats and membranes and their associated tethering force that pulls the two membranes, partly due to lack of an approach to dissecting the force-dependent cooperative C2-membrane and C2-C2 interactions. We recently developed a novel approach based on high-resolution optical tweezers to measure protein-membrane interactions17. Here, we used this approach for a comprehensive analysis of the membrane interaction of the cytosolic portion of human E-Syt1 and E-Syt2.

E-Syts are a class of evolutionarily conserved proteins that comprise an N-terminal hydrophobic hairpin anchored into the ER membrane, a synaptotagmin-like mitochondrial lipid-binding protein (SMP) domain, and a C-terminal C2 repeat containing five C2 domains in E-Syt1 (designated as C2ABCDE) and three C2 domains in E-Syt2 (C2ABC, Fig. 1a) and E-Syt37,8,10 (Extended Data Fig. 1). These folded C2 domains are connected by disordered polypeptides of variable lengths. Regulated by cytosolic Ca2+, the E-Syts participate in tethering the PM and the ER, where most lipids are synthesized, to mediate lipid exchange or recruit other proteins11,18. Fluorescence and electron microscopy (EM) of cells transfected with tagged E-Syt1 revealed that this protein, when expressed alone, only sparsely populates ER-PM contacts at resting Ca2+ level with an average membrane separation in the range of 22–25 nm, while upon elevation of cytosolic Ca2+ it undergoes massive accumulation at these sites (resulting in their expansion) in a C2C- and C2E-dependent manner, with an average membrane separation of ~15 nm10,19–21. In contrast, transfected tagged E-Syt2 and E-Syt3 are localized constitutively at membrane contact sites even at a resting Ca2+ level, with a membrane separation of ~19 nm for overexpressed E-Syt3. The C2C domains in both E-Syt2 and E-Syt3 are required for inducing membrane contacts.

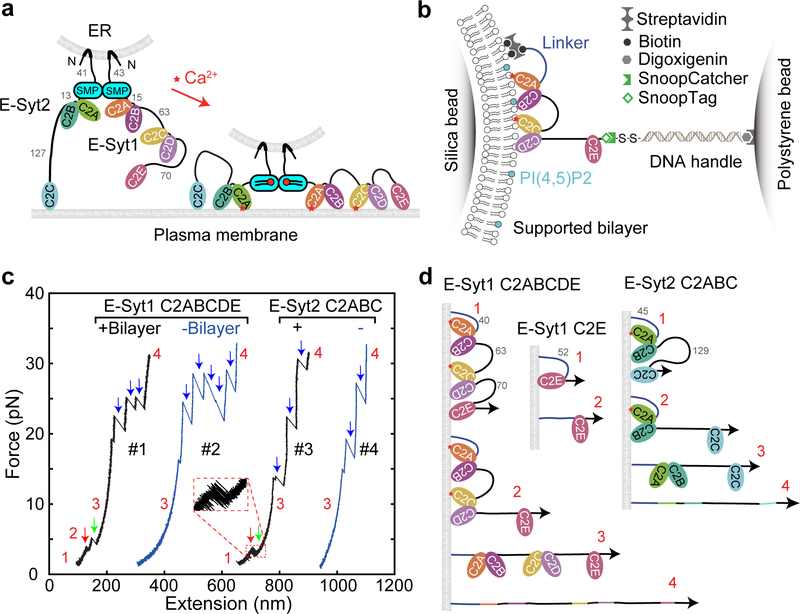

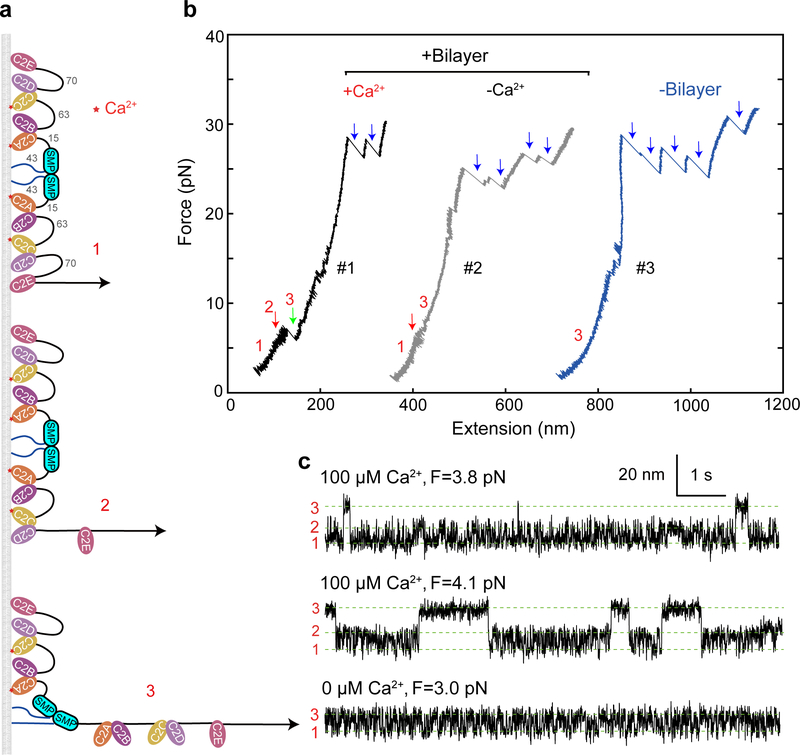

Fig. 1. E-Syt C2 domains bind membranes in a stepwise manner as revealed by optical tweezers.

(a) ER-anchored E-Syts form a dimer via their SMP domains and bind to the plasma membrane (PM) via their tandem C2 domains, pulling the ER-PM membrane close to facilitate lipid transfer in a Ca2+-dependent manner. The lengths of disordered linkers joining different C2 domains are indicated by their numbers in amino acids. (b) Schematics of the experimental setup to pull a single E-Syt1 C2 repeat C2ABCDE. (c) Force-extension curves (FECs) obtained by pulling single C2 repeats in the presence or absence of the lipid bilayer. Red and green arrows indicate stepwise C2 unbinding from the membrane, and black arrows denotes unfolding of individual C2 domains. (c) Schematics of different C2 binding states for some C2 domains or repeats tested in this study.

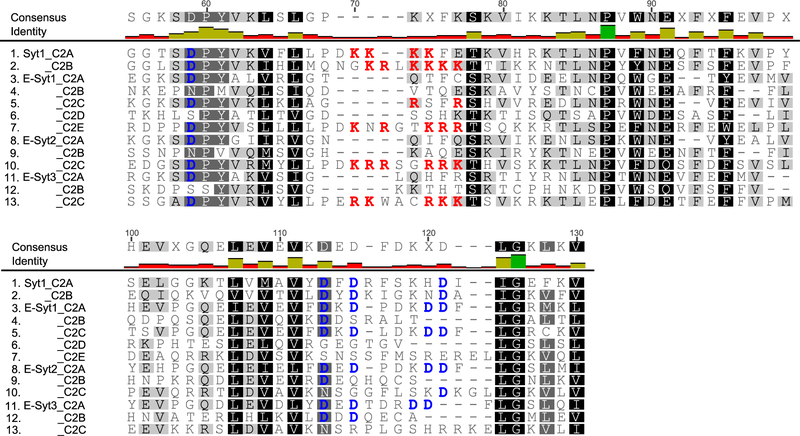

Despite extensive studies, it remains unclear precisely how the E-Syts bind the PM in trans, regulate the ER-PM distance in a Ca2+-dependent manner, and transfer lipids22–25. In general, C2 domains bind membranes via two conserved motifs: a basic patch and a Ca2+-binding site (Extended Data Fig. 2, Supplementary Table 1), both of which favor binding of negatively charged lipids enriched in the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane, such as PS and PI(4,5)P226. The C2A and C2C of E-Syt1 and the C2A of E-Syt2 and E-Syt3 contain the Ca2+-binding motif and bind PM at elevated Ca2+ levels. In contrast, the C-terminal C2 domains of all three E-Syts (C2E of E-Syt1 and C2C of E-Syt2 and E-Syt3) bear only the basic patch and bind the PM at resting Ca2+ levels4,17. In view of this similarity of their C-terminal C2 domains, it is not clear why E-Syt1 and E-Syt2 or E-Syt3 exhibit different efficiency in forming the ER-PM contact sites10,19–21. Intriguingly, E-Syt1 C2B and C2D do not contain any obvious membrane binding motifs. Nevertheless, both C2 domains may directly bind membranes or interacts with the corresponding C2A and C2C partners5,22 to indirectly affect membrane binding. Their exact functions remain to be tested. Furthermore, quantitative understanding of the different efficiency of the three E-Syts in accumulating at, and inducing, ER-PM membrane contacts is lacking. To address these questions, accurate measurements of membrane binding affinities and kinetics of different C2 domains as a function of force, Ca2+ concentration, and lipid composition are required. Membrane bridging by E-Syts occurs against a pulling force that typically attenuates binding and promotes unbinding17. In addition, an analytical method is needed to dissect the cooperativity between different C2 domains in single E-Syts. These experimental and theoretical requirements impose a great challenge to dissect the role of C2 repeats in membrane binding and tethering.

We extended our single-molecule method17 to measure the force-dependent binding affinities and kinetics of E-Syt1 and E-Syt2 as a function of Ca2+ and lipid concentrations. We developed an analytic method to help derive membrane binding parameters corresponding to isolated C2 domains. Using these parameters, we calculated the average tethering force, probabilities, and free energy of different C2 binding states. The derived equilibrium membrane separations and their probabilities match the corresponding measurements in vivo.

Results

Stepwise binding and unbinding of C2 domains in E-Syts.

As in our previous experimental setup17, we tethered fragments of the C2 containing regions of E-Syt1 and E-Syt2, i.e., E-Syt1 C2ABCDE or E-Syt2 C2ABC, to a bilayer-coated silica bead 2 μm in diameter at its amino terminus and to a polystyrene bead at its carboxy terminus via a 2,260 bp DNA handle (Fig. 1b). The two micron-sized beads were optically trapped with dual-trap optical tweezers and used to detect the tension and extension of the protein-DNA tether. To mediate the attachment, we added an Avi-tag followed by a flexible polypeptide linker to the amino terminus of the protein fragment and a 12-amino-acid (a.a.) SnoopTag to its carboxyl terminus27 (Extended Data Fig. 3). The SnoopTag was conjugated to its cognate SnoopCatcher protein to which the DNA handle was crosslinked28. To mimic the lipid composition of the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane, the supported bilayer consisted of 85 mol% POPC, 10 mol% DOPS, 5 mol% PI(4,5)P2, and additional 0.03 mol% biotin-PEG-DSPE unless specified otherwise. Finally, we applied tension to the protein fragment by changing the distance between two optical traps (a process that we will refer to as “pulling”) at a speed of 10 nm/s (Fig. 1c) or kept the protein at a constant mean force by holding the distance constant (Fig. 2).

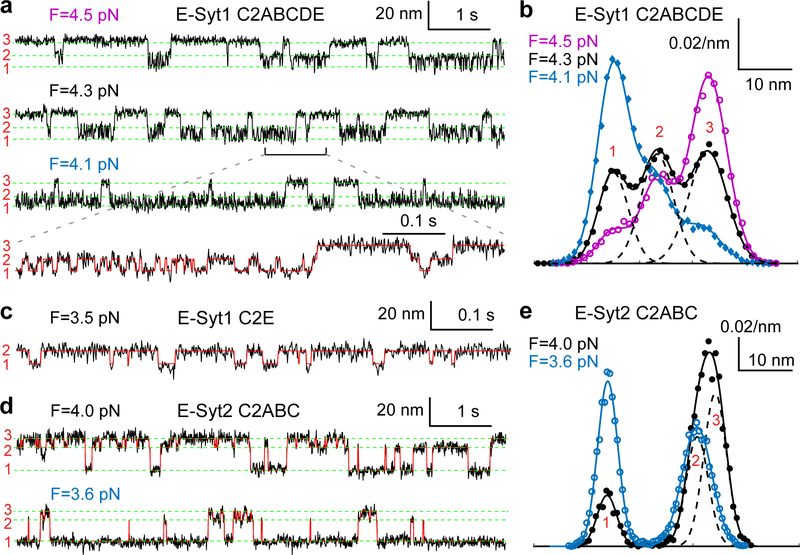

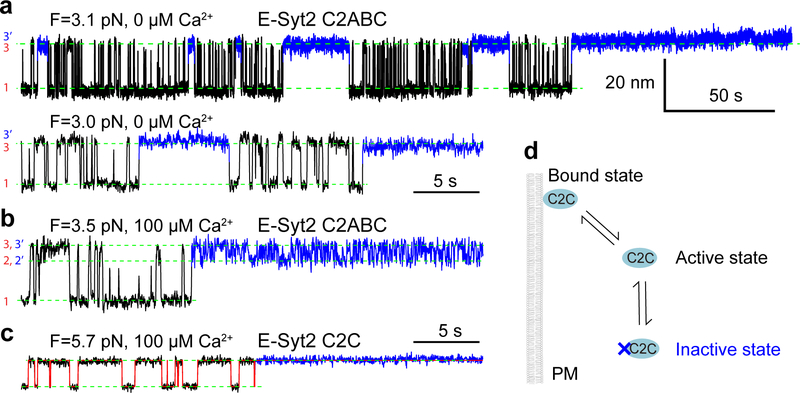

Fig. 2. E-Syt C2 domains reversibly and sequentially bind to membranes.

(a, c, d) Extension-time trajectories at constant mean force F for the C2 repeat E-Syt1 C2ABCDE (a), E-Syt1 C2E (c), or E-Syt2 C2ABC (d). The average extensions of three states (numbered on the left as in Fig. 1d) are marked by green dashed lines. A close-up view of the indicated region in the second trajectory in a is shown in the fourth trajectory. The overlaying red trace represents an idealized state transition derived from hidden-Markov modeling (HMM), as in other extension-time trajectories. (b, e) Probability density distributions of the extensions shown in a or d (symbols) and their best fits with a sum of three Gaussian functions (solid curves), with the individual Gaussian functions shown as dashed curves for the black curves.

We first pulled E-Syt1 C2ABCDE in the presence of 100 μM Ca2+ in the solution. The resultant force-extension curve (Fig. 1c, FEC #1) exhibits at least two extension jumps at low force (<12 pN, red and green arrows) and up to five jumps at high force (>12 pN, blue arrows). The low force jumps are membrane-dependent, as they disappeared when the experiment was repeated in the absence of the membrane (Fig. 1c, FEC #2). Thus, these jumps likely resulted from stepwise unbinding of different C2 domains from the bilayer (Fig. 1d). In contrast, the high force jumps are membrane-independent and represents unfolding of individual C2 domains as was observed before17. Not all C2 unfolding events were detected in each pulling round, due to premature detachment of the protein-DNA tether from bead surfaces typically above 35 pN. E-Syt2 C2ABC showed similar membrane unbinding transitions at low force and C2 domain unfolding at high force (Fig. 1c, FEC #3–4; Fig. 1d).

Close inspection indicates that the low force jumps were generally reversible with frequent flickering between high and low extensions, indicating fast unbinding and rebinding transitions of C2 domains (Fig. 1c, inset). To better resolve the C2 transitions, we held a single C2ABCDE at different constant mean forces and measured the tether extension over an extended time (Fig. 2a). Despite their fast transitions, three distinct states were discernable, as were confirmed by three peaks in the probability density distributions of extension (Fig. 2b). Accordingly, the extension trajectories were well fit by three-state hidden Markov modeling (Fig. 2a, red curve in the bottom trace), revealing average extensions (Fig. 2a, green dashed lines) and probabilities of all states and transition rates among them (Fig. 3a).

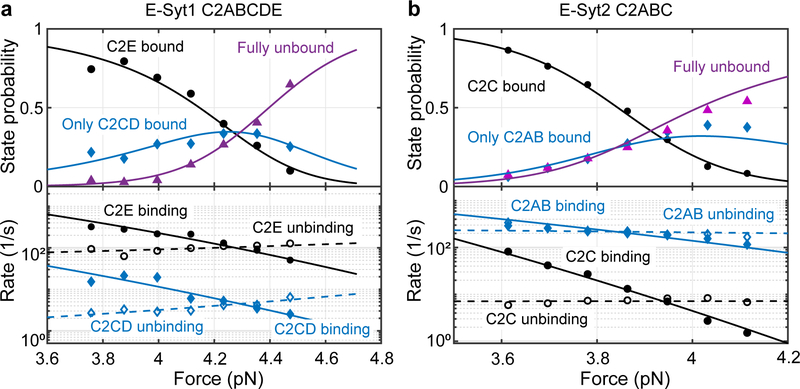

Fig. 3. Force-dependent probabilities and transition rates of different C2 binding sates for E-Syt1 C2ABCDE (a) and E-Syt2 C2ABC (b).

Experimental measurements and their best model fits (see Methods) are indicated by symbols and lines, respectively. The experiments were conducted with 85 mol% POPC, 10 mol% DOPS, 5 mol% PI(4,5)P2, and 0.03 mol% biotin-PEG-DSPE in the presence of 100 μM Ca2+. Due to the large extension changes, state populations changed dramatically with force30.

Next, we derived the C2 binding states associated with the three extension levels. E-Syt1 C2ABCDE contains three well-separated membrane-binding modules: C2AB, C2CD, and C2E (Fig. 1a). Binding of each C2 pair would contribute to a single distinct extension, given the proximity of the two C2 domains in each C2 pair, as was observed for Syt1 C2AB17 and E-Syt2 C2AB5,22. Therefore, sequential membrane binding of all three modules in E-Syt1 would produce four distinct extension levels, including the maximum extension corresponding to the completely unbound state. We noticed that state 3 had the maximum extension among the three observed states and was stable at higher pulling force till C2 unfolding (Fig. 1c, FEC#1). Thus, state 3 represents the completely unbound state. Based on their extensions relative to state 3, state 1 and state 2 probably are C2CD- and C2E-bound states, respectively (Fig. 1d). In contrast, membrane binding by C2AB was too weak to be detected by our assay17.

To confirm our state assignment, we pulled isolated E-Syt1 C2AB and C2E domains under otherwise identical experimental conditions. Consistent with our derivation, we did not observe any membrane binding of E-Syt1 C2AB (Extended Data Fig. 3). This result was surprising, given the presence of the Ca2+ binding motif in C2A and its important role in lipid exchange in vitro4,14, but consistent with the finding that a C2A mutation abolishing its Ca2+ binding barely affects membrane tethering by E-Syt1 both in vitro and in vivo4. As reported previously4, a main role of the Ca2+ binding to the C2A domain may be to release the autoinhibitory interaction of this C2 domain with the SMP domain. Interestingly, we detected weak membrane binding of E-Syt1 C2AB when the DOPS concentration was increased from 10% to 20% (Extended Data Fig. 4). In contrast, we observed membrane binding by E-Syt1 C2E alone (Figs. 2c & 1d). Moreover, the binding exhibited fast kinetics as in E-Syt1 C2ABCDE. Taken together, these results corroborated the C2 binding states derived from our measurements (Fig. 1d).

E-Syt2 C2ABC also shows three-state transitions (Figs. 2d–e), consistent with the presence of two C2 binding modules C2AB and C2C. We previously measured the binding energy and kinetics of the two isolated modules17. Comparing the binding kinetics of these isolated modules with those of the linked ones as in E-Syt2, E-Syt2 C2AB binding/unbinding transition was consistently faster than that of E-Syt2 C2C. Based on the comparison, we derived a sequential binding model for E-Syt2 (Fig. 1d). Different from E-Syt1 C2AB, E-Syt2 C2AB showed moderate affinity for the membrane with 10% DOPS.

Energetics and kinetics of membrane binding.

We analyzed the extension trajectories at constant forces using a three-state hidden-Markov model29, yielding the probabilities and transition rates of all three states as a function of force (Fig. 3). The modeling revealed the sequential transition rates (i.e., rates for transitions between states 1 and 2 and between states 2 and 3) orders of magnitude higher than non-sequential transition rates (i.e., rates for the transition between states 1 and 3), which confirms the sequential binding and unbinding models for both C2 repeats (Fig. 1d).

We fit the measured probabilities and transition rates using a force-dependent protein-membrane binding model, yielding unbinding energy and binding and unbinding rates of all tethered and isolated C2 modules at zero force (Supplementary Table 2)17,30. The binding affinities obtained by us corroborate previous qualitative observations4,10,13,19. Surprisingly, while the C-terminal C2 domains of E-Syt1 and E-Syt2 (i.e. E-Syt1 C2E and E-Syt2 C2C) are closely related to each other, E-Syt1 C2E has much lower membrane binding affinity (6 ± 1 kBT, mean ± SEM throughout the text) than E-Syt2 C2C (13.0 ± 0.7 kBT). This observation suggests that the membrane binding affinity of C2 domains is likely modulated by subtle differences in their canonical binding motifs and residues in other regions. However, the large difference in the binding affinity explains well the different efficiencies of membrane contact formation mediated by both E-Syts19, as will be clarified in the forthcoming section.

Effect of Ca2+ on membrane binding.

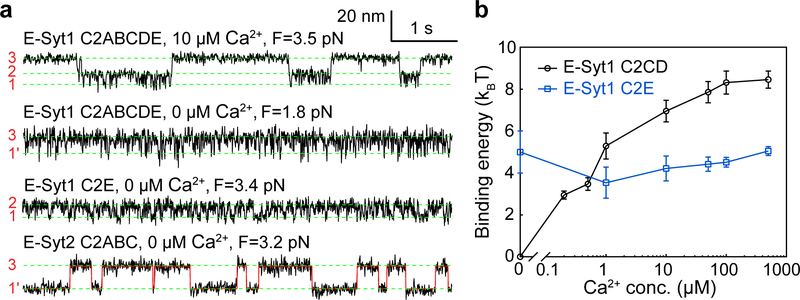

To characterize Ca2+-dependent membrane binding by E-Syt1 C2ABCDE and E-Syt2 C2ABC, we developed a flow control system to facilitate the Ca2+ concentration change in the solution where a single C2 repeat was being pulled (Extended Data Fig. 5). In the presence of 10 μM Ca2+, E-Syt1 C2ABCDE showed robust three-state transitions (Fig. 4a, top trace) as in the presence of 100 μM Ca2+ (Fig. 2a). However, the equilibrium force for C2CD transition was reduced, indicating a decrease in C2CD binding energy. In contrast, the C2E transition barely changed. In the absence of Ca2+, the C2CD transition disappeared, whereas the C2E transition shifted to lower force (~2 pN) but with a slight increase in the extension change (Fig. 4a, second trace). The extension increase is consistent with a longer linker tethering C2E to the membrane (203 a.a.), which is equivalent to a direct transition between unbound state 3 and a C2E-bound but C2CD unbound state 1’. Consequently, the accompanying force decrease does not necessarily indicate a reduced affinity of C2E for the membrane30. Supporting this view, we repeated the experiment using E-Syt1 C2E with a short linker (60 a.a.) and found that the equilibrium force increased to ~3.4 pN (Fig. 4a, third trace). We determined the binding energy of both C2CD and C2E as a function of Ca2+ concentration (Fig. 4b). Consistent with its Ca2+ binding motif (Extended Data Fig. 2), C2CD bound the membrane in a Ca2+-dependent manner: the binding was undetectable in the absence of Ca2+, quickly increased in the range of 0.1–10 μM Ca2+, and reached saturation above 50 μM Ca2+. In contrast, C2E binding was Ca2+-independent, consistent with its lack of the Ca2+ binding motif.

Fig. 4. Membrane binding of E-Syt1 C2CD and E-Syt2 C2AB is Ca2+-dependent, while binding of E-Syt1 C2E and E-Syt2 C2C is Ca2+-independent.

(a) Extension-time trajectories at constant force in different Ca2+ concentrations. (b) Unbinding free energy of E-Syt1 C2CD and C2E as a function of [Ca2+]. Each average energy value was determined by measurements from at least three different single molecules (n = 10 for 500 μM, 100 μM, 50 μM, 10 μM, n = 9 for 1 μM, n = 5 for 0.5 μM, n = 3 for 0.2 μM and 0 Ca2+, respectively). The n number varied as a single molecule broke during buffer changed in all probability. Data are presented as mean values +/− SEM.

Similarly, we measured the membrane binding transition of E-Syt2 C2ABC at constant force in the absence of Ca2+ (Fig. 4a, bottom trace). The transition was two-state and mediated only by E-Syt2 C2C. Consistent with our early results, E-Syt2 C2AB and C2C bound membranes in a Ca2+-dependent and Ca2+-independent manner, respectively (Supplementary Table 2).

Effects of negatively charged lipids.

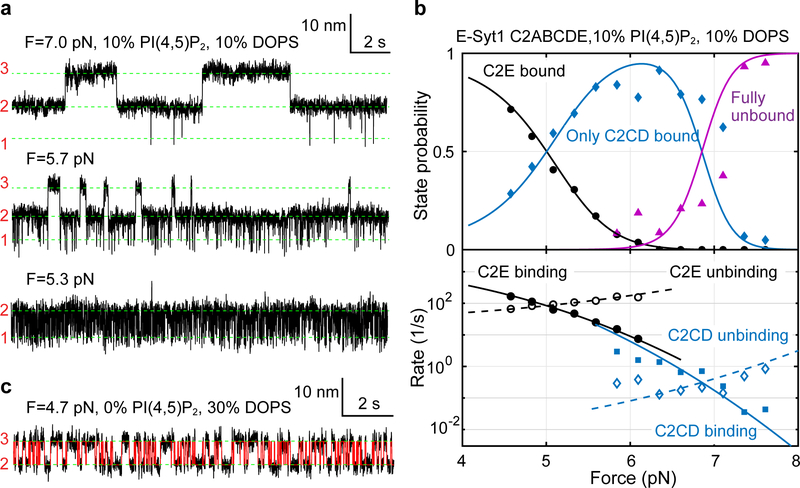

Previous work suggests that E-Syt C2 domains bind PM by recognizing negatively charged lipids, especially PI(4,5)P2 and DOPS, in the inner leaflet of PM4,10,20. To examine the effect of both lipids on membrane binding by C2 repeats, we first increased the PI(4,5)P2 concentration from 5 mol% to 10 mol% and repeated the binding assay. E-Syt1 C2ABCDE continued to bind and unbind sequentially among three states (Fig. 5a). However, both C2CD and C2E transitions shifted to higher force ranges, indicating their tighter membrane binding (compare to Fig. 2a). Moreover, the C2CD transition had greater force shift than C2E, which nearly separated the two otherwise overlapping transitions into different force ranges (Figs. 5a & 5b). Extensive measurements showed that the rise in PI(4,5)P2 concentration from 5% to 10% significantly increased the affinities of C2CD from 10.4 (±0.9) kBT to 14.5 (±0.9) kBT and of C2E from 6 (±1) kBT to 8.4 (±0.3) kBT. To test whether the membrane binding requires specific lipids, we omitted PI(4,5)P2 but increased DOPS to 30% to keep the charge density the same. We found that while the C2CD affinity was reduced, C2E binding was completely abolished (Fig. 5c & Extended Data Fig. 6). Therefore, C2E specifically binds PI(4,5)P2, whereas C2CD binds both DOPS and PI(4,5)P2, with a preference for the latter. The critical role of PI(4,5)P2 in membrane binding of both C2 modules is consistent with the dramatic effect of PI(4,5)P2 on membrane contact formation observed in cells10.

Fig. 5. Membrane binding of E-Syt1 C2CD and C2E differentially depends upon PI(4,5)P2 and DOPS.

(a) Extension-time trajectories of E-Syt1 C2ABCDE at constant force with 10 mol% PI(4,5)P2. (b) Force-dependent probabilities and transition rates of different E-Syt1 binding states (symbols) and their best model fits (lines). (c) Extension-time trajectory of E-Syt1 C2ABCDE at constant force in the presence of 30% DOPS and no PI(4,5)P2.

A novel inactive conformation of E-Syt2 C2C.

Extended measurements of E-Syt2 C2ABC at constant force revealed a fourth state 3’ seen as long gaps between the rapid three-state transitions described above (Extended Data Fig. 7). Besides its long dwell time, the state had the same average extension as the C2C-unbound state 3, indicating a new C2C unbound state. The new state persisted regardless of both Ca2+ and E-Syt2 C2AB. These observations suggest that C2C had two unbound states: one was active for binding membranes within tens of milliseconds under our experimental conditions (the active state), whereas the second state was inactive for membrane binding for a longer period (1–200 s, the inactive state) but could slowly return to the active state. It appears unlikely that the inactive C2C state resulted from an inhibitory association of the C2C membrane binding site with the surrounding linker regions, which would lead to its shorter extension than that of the unbound state. The conformation of the inactive C2C state remains to be explored.

Binding kinetics of the cytosolic E-Syt1 dimer.

To examine the role of the SMP domain on E-Syt1 membrane binding, we attached the entire cytosolic E-Syt1 dimer to the supported bilayer and pulled an E-Syt1 monomer via its C-terminus as we did for the fragments containing C2 domains only (Extended Data Fig. 8). The force-extension curves indicate that the E-Syt1 monomer bound to and unbound from the membrane in a stepwise manner approximately identical to C2ABCDE. The observation was further confirmed by the Ca2+-dependent three-state C2CD and C2E transitions and Ca2+-independent C2E transition at constant force. These comparisons suggest that the SMP domain showed minimal membrane binding affinity and the C2 domains in the two E-Syt1 monomers. Our derivation is consistent with the experimental observations that membrane contacts still form with SMP-truncated E-Syt10 and SMP alone does not bind membranes in trans4.

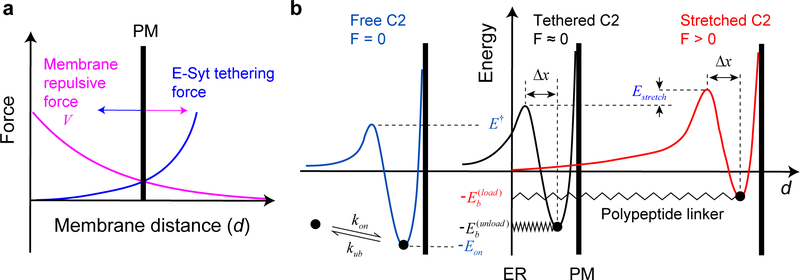

Calculations of trans-membrane binding properties of E-Syts.

Multiscale molecular modeling and other simulation approaches have been applied to calculate various properties of receptor-mediated biomembrane adhesion31,32. Although these methods consider detailed membrane conformations, including membrane deformation and undulation, they are computationally intensive, and to our knowledge, have not been applied to model E-Syt-mediated membrane contacts. Therefore, we developed a simplified analytic method to calculate salient trans-membrane binding properties of E-Syts based on the measured membrane binding parameters of isolated C2 modules (Fig. 6a and Supplementary Table 2). The method included an empirical membrane repulsive potential and considered several distinct features of E-Syts compared with membrane-anchored receptors (see Methods and Extended Data Fig. 9): (1) force-dependent extension and entropic energy of the polypeptide linkers described by a worm-like chain model33; (2) force-dependent binding energy and kinetics of each C2 module; and finally (3) cooperativity between successive binding of C2 modules due to the tethering effect17,34. Because the two E-Syt molecules within a single dimer independently bind the membrane, our calculations were performed for a single E-Syt monomer for simplicity.

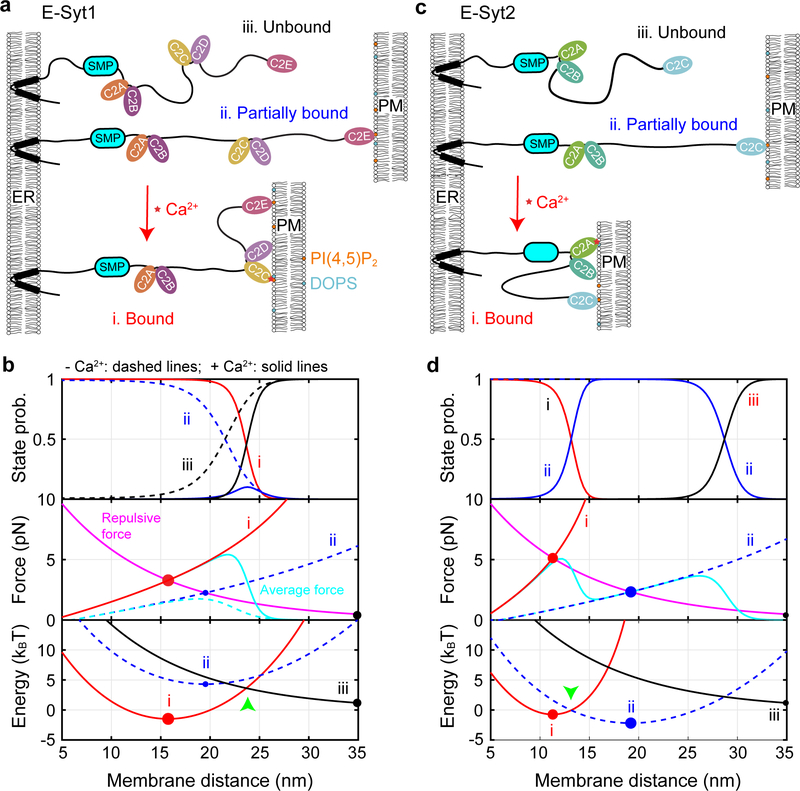

Fig. 6. Properties of E-Syt-mediated ER-PM contacts can be theoretically modeled.

(a, c) Schematics of different C2 binding and membrane tethering states of E-Syt1 (a) or E-Syt2 (c) in the absence and presence of Ca2+. (b, d) Calculated probabilities (top panel), tethering force (middle), and total free energy (bottom) of different states of E-Syt1 (b) or E-Syt2 (d). Calculations corresponding to the presence of Ca2+ or the absence of Ca2+ are indicated by solid and dashed lines, respectively. Equilibrium states are indicated by filled circles with their sizes representing the corresponding state probabilities.

We first calculated the binding probabilities of different C2 modules and their associated membrane pulling forces as a function of the distance between two stationary planar membranes. E-Syt1 C2E is located 76 nm away from the ER membrane as estimated by the contour length of the protein. However, C2E reaches 50% binding probability only at 21.5 nm (Fig. 6b, top panel, blue dashed curve). The tethering force depends on the C2 binding state and the state-averaged force due to C2E binding reaches a maximum of 1.7 pN at 18.8 nm membrane separation (Fig. 6b, middle panel, cyan dashed curve). In the presence of 100 μM [Ca2+], C2CD dominates membrane binding at a PM distance less than 25.2 nm (Fig. 6b, top panel, red solid curve), while binding of C2E alone peaks at ~24 nm with a maximum ~10% probability (blue solid curve). Correspondingly, a single E-Syt1 monomer generates 5.4 pN maximum average tethering force at a distance of 22 nm (middle panel, cyan solid curve).

E-Syt2 C2C binds to the PM with 50% probability at 26.7 nm in the absence of Ca2+ (Fig. 6c; Fig. 6d, top panel), a greater distance than E-Syt1 C2E. This observation is consistent with the fact that C2C has much higher binding affinity than C2E, yet comparable linker length from the ER membrane (Fig. 1a, 191 a.a. for E-Syt1 C2E vs 181 a.a for E-Syt2 C2C). Accordingly, E-Syt2 C2C generates a maximum average stretching force of 3.7 pN at 26.2 nm membrane separation (Fig. 6d, middle panel). In the presence of 100 μM Ca2+, C2C binding remains unchanged, whereas C2AB associates with the PM with 50% probability at 13.2 nm and generates maximum tethering force of 5 pN at 12.2 nm.

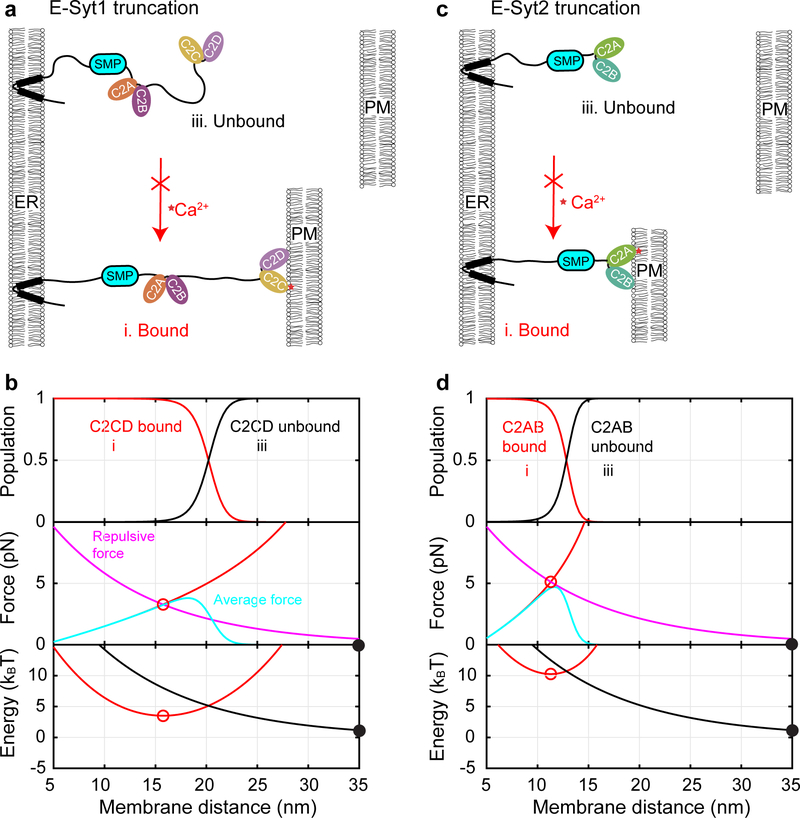

When either membrane is free to move as in the cell, the tethering force generated by E-Syts will be counteracted by the repulsive force between the two membranes (Figs. 6b and 6d, middle and bottom panels). We determined the equilibrium membrane separations for the three E-Syt1 binding states (Extended Data Fig. 9a): 15.8 nm for both C2CD and C2E bound state (Fig. 6b, middle panel, red filled circle), 19.5 nm for the C2E only bound state (hollow circle), and >35 nm for the unbound state indicating no membrane contact formation (gray filled circle). The probabilities of these states are determined by the Boltzmann distribution based on their associated free energy (Fig. 6b, bottom panel; Supplementary Table 3; Extended Data Fig. 9b). In the absence of Ca2+, the C2E bound state has much higher energy (4.3 kBT) than the unbound state with a large membrane separation (0 kBT), implying rare formation of ER-PM contacts. In the presence of 100 μM Ca2+, the C2CD- and C2E-bound state dominates with free energy of −1.5 kBT, indicating robust membrane contact formation. However, C2E is also essential for membrane contact formation by cooperating with C2CD to stabilize the contact. With C2CD alone, the energy of the corresponding C2 tethered state increases to 3.5 kBT, suggesting poor membrane contact formation (Extended Data Fig. 10 & Supplementary Table 3). All these calculations regarding the average distances and probabilities of the E-Syt1-mediated membrane contacts and their Ca2+- and C2E-dependence are consistent with previous measurements4,10,19 (Supplementary Table 3).

Similarly, we calculated the parameters associated with E-Syt2-mediated membrane contacts. Without Ca2+, E-Syt2 C2C stably tethers the PM at 19 nm with a free energy of −2.2 kBT relative to the unbound state (Fig. 6d, middle and bottom panels, filled circles; Supplementary Table 3). With Ca2+, E-Syt2 C2AB further binds to PM, reducing the membrane separation to 11.3 nm and slightly increasing the free energy to −0.75 kBT (Fig. 6d, red hollow circles). The C2AB domain is expected to rapidly bind and unbind from the membrane, because the associated energy barrier is small (Fig. 6d, bottom panel, green arrow), which may facilitate lipid transfer. In the absence of C2C, the energy of the C2AB-bound state increases to 10 kBT, which essentially abolishes membrane contact formation (Extended Data Fig. 10). These calculated parameters are generally consistent with the corresponding in vivo measurements for E-Syt2 or E-Syt3 (Supplementary Table 3)19.

Discussion

Numerous proteins couple their membrane binding to mechanical force generation or sensing as a key process for their biological functions31,35–38. In turn, mechanical force affects proteins binding to membranes. It is technically challenging to investigate the interplay between mechanical force and protein-membrane interactions. Here we applied optical tweezers to quantify membrane binding of E-Syt1 and E-Syt2. We detected stepwise membrane binding of individual binding modules at different force and extracted the binding affinities of isolated C2 modules. Surprisingly, despite the strong similarities of the two C-terminal C2 domains of E-Syt1 and E-Syt2, we found that E-Syt1 C2E has much lower membrane affinity than E-Syt2 C2C. This difference explains the different ability of two E-Syts to mediate membrane contacts in a resting state when expressed alone19, as is confirmed by our theoretical modeling. In addition, C2E requires PI(4,5)P2 for its membrane binding and such requirement cannot be substituted by DOPS. Previous studies had suggested that E-Syt1 C2C interacts with C2E in the absence of Ca2+ and that such interaction inhibits C2E membrane binding4,20 unless cytosolic Ca2+ is elevated. Our single-molecule experiments did not provide support for this hypothesis and revealed instead that the lack of E-Syt1-mediated membrane contacts in low Ca2+ mainly results from the intrinsically weak affinity of the E-Syt1 C2E domain for the PM membrane. It may be possible that an additional auto-inhibitory interaction may be too weak to be detected by our assay17. We also discovered that E-Syt1 C2AB has much lower membrane binding energy (6.5 ± 0.3 kBT at 20 mol% DOPS, Supplementary Table 2) than the closely related E-Syt2 C2AB (9 ± 1 kBT)17. A main function of the Ca2+ binding property of this domain is to release an autoinhibitory interaction with the SMP domain which prevents its lipid transport properties4. In contrast, E-Syt1 C2CD tightly bind membranes with a Ca2+-dependence consistent with in vivo imaging results10.

We developed a theoretical method to successfully predict salient properties of E-Syt-mediated membrane contacts based on the measured C2 binding parameters. Our calculations also revealed new insights into E-Syt-mediated membrane tethering and lipid exchange. Given a maximum tethering force of ~ 5 pN generated by each E-Syt monomer, we estimated that each E-Syt dimer can produce an average force ~ 10 pN. Compared with the force of 10–50 pN to pull a single membrane tubule from the plasma membranes39,40, the average force indicates that a few E-Syt dimers may be sufficient to form membrane contact sites. As the first contact forms, one may expect high cooperativity in the binding of other E-Syts to stabilize or expand the contact. Cooperation may also arise from stable heterodimerization of different E-Syts10. Together, the cooperation may lead to sequential binding of the C2 domains in different E-Syts and corresponding decrease in the ER-PM distance. In a low Ca2+ concentration, E-Syt2 or E-Syt3 may start to tether the PM through their C2C domain at a distance >30 nm, which facilitates E-Syt1 C2E binding at ~24 nm (Fig. 6). Ca2+ elevation triggers ordered PM binding of E-Syt1 C2CD, E-Syt2 C2AB, and finally E-Syt1 C2AB, further reducing the membrane distance and/or expanding the contact sites. The tight ER-PM contacts stimulate direct lipid exchange by E-Syts or recruitment of other proteins, such as Nir2 in mammals or RdgB in Drosophila11,18, to regulate PM lipid homeostasis. All these derivations rely on force-dependent membrane binding of the C2 domains deduced from our experiments, highlighting the unique advantage of the single-molecule manipulation assay in the study of protein-membrane interactions.

Despite its simplicity and analytical nature, our theoretical method relies on the empirical membrane repulsive potential and ignores excluded volume interactions among different segments of E-Syts and membrane surfaces38. These interactions are expected to play a role in membrane contact formation at a short membrane distance or high E-Syt density. More work is required to refine our theoretical method and further test its predictions.

Methods

Plasmids and protein constructs.

The gene coding for residues 93–1104 (SMP-C2ABCDE), 321–1104 (C2ABCDE) or 936–1104 (C2E) of human E-Syt1 was cloned into the pCMV6-An-His vector. The regions coding for residues 321–603 of human E-Syt1 (C2AB) and residues 343–893 of human E-Syt2 (C2ABC) were cloned into the pET-SUMO vector. In both vectors, an Avi tag was inserted between the His tag and the protein and a SnoopTag just after the protein. The plasmids encoding E-Syt2 C2AB and C2C were previously described4,17. The amino acid sequences of all the protein constructs are shown in Supplementary Information.

Protein constructs, expression, and purification.

Expression in eukaryotic cells.

E-Syt1 SMP-C2ABCDE, E-Syt1 C2ABCDE, or E-Syt1 C2E was expressed in Expi293 cells with an N-terminal His6-tag, as described previously4,13. Briefly, cells were harvested by centrifugation at 300 x g for 5 min and lysed by three freeze–thawing cycles in buffer A [25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, 1× complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche), 0.5 mM TCEP] using liquid nitrogen. The lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 17,000 x g for 30 min, and the protein was isolated by a Ni-NTA column (Clontech). Gel filtration (Superdex 200, GE Healthcare) was used to further purify the protein in buffer B (25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM TCEP). Pool and concentrate the fractions containing E-Syt1 to ~1 mg/ml.

Expression in bacteria.

E-Syt1 C2AB, E-Syt2 C2ABC, E-Syt2 C2AB, or E-Syt2 C2C was transformed into BL21 (DE3) RIL Codon Plus (Agilent) E. coli cells. Cells were grown in Super Broth medium at 37 °C to an OD600 of 0.6, and the expression was induced by addition of 0.5 mM IPTG over night at 18 °C. The cells were collected and lysed by sonication in buffer A. The lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 30,000 x g for 1 h. The protein was purified by the same procedure as the protein expressed in eukaryotic cells. Pool and concentrate the fractions containing E-Syt1 to ~1 mg/ml. The proteins with SUMO tag were digested by SUMO protease over night at 4 °C and then were further purified by Ni-NTA column followed by gel filtration in buffer B.

Protein and DNA handle conjugation.

A unique cysteine residue was introduced to SnoopCatcher and used to crosslink to the thiol-containing 2,260 bp DNA handle as previously described41. The purified E-Syt fragments were biotinylated using BirA biotin ligase (BirA500, Avidity), with free biotin removed by gel filtration (Micro Bio-Spin 6 Columns, Bio-Rad). The E-Syt constructs containing the Snoop tag were mixed with the SnoopCatcher-DNA handle mixture with 5:1 molar ratio of E-Syt protein to SnoopCatcher and then incubated overnight to conjugate the E-Syt proteins to the DNA handles via SnoopCatcher.

Membrane coating on silica beads.

The protocol to prepare membrane-coated silica beads has been detailed elsewhere17. Briefly, a mixture of chloroform-dissolved lipids was dried under a nitrogen flow followed by evaporation in vacuum for one hour. The dried lipids were then rehydrated in the HEPES buffer containing 25 mM HEPES, pH7.4, and 200 mM NaCl. Small unilamellar vesicles (SUVs) were formed by sonication and centrifugation of the hydrated lipids. The silica beads (2.0 μm, SS04N, Bangs Laboratories) were added to the SUVs and vortexed at 37 °C for 45 minutes. SUVs spontaneously collapsed to the surfaces of the silica beads to form supported bilayers with high membrane tension. The beads were then washed five times using the HEPES buffer to remove excessive SUVs through cycles of centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 45 seconds and resuspension. All lipids were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids: POPC (850457P), DOPS (840035P), Brain PI(4,5)P2 (840046X), Biotin-PEG(2000)-DSPE (880129P).

Dual-trap high-resolution optical tweezers.

The dual-trap high-resolution optical tweezers are described elsewhere in detail17,42,43. The optical tweezers are assembled on an optical table (TMC, MA) located in an acoustically isolated and temperature-controlled room. A 1064 nm laser beam from a solid-state laser (Spectra-Physics, CA) is expanded approximately fivefold by a telescope and split into two orthogonally polarized beams. The beams are reflected by two mirrors: one is fixed and the other is mounted on a high-resolution piezoelectric actuator (Mad City Labs, WI) that turns the mirror in two directions. The two beams are combined, further expanded two-fold by a second telescope, and focused using a water immersion 60X objective with a numerical aperture of 1.2 (Olympus, PA) to form two optical traps around the center of a microfluidic chamber44. The outgoing laser beams are collected and collimated by another objective, split by polarization, and projected to two position-sensitive detectors (Pacific Silicon Sensor, CA). The displacements of two trapped beads were detected using back-focal-plane interferometry45. An EMCCD camera (Andor iXon3) is used to for wide-field epifluorescence imaging43. The tweezers were operated using a computer interface written in LabVIEW (National Instruments, TX).

Single-molecule manipulation experiments.

The single molecule experiments have been detailed elsewhere17,41. An aliquot of the protein-DNA conjugate mixture was bound to anti-digoxigenin antibody-coated polystyrene beads 2.1 μm in diameter (Spherotech, IL) and injected to the top microfluidic channel, while the membrane-coated silica beads were injected to the bottom channel. Two beads were captured by optical traps and their Brownian motions were measured to determine the stiffnesses of the two traps. The beads were then brought close to form tethers between two bead surfaces. The pulling experiments were performed at room temperature (~23 °C) in 25 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 200 mM NaCl, 500 μM EGTA, 0–1 mM CaCl2, and the oxygen-scavenging system41.

Hidden-Markov modeling (HMM) and derivations of binding energy and kinetics.

Methods and algorithms of HMM and energy and rate derivations are detailed elsewhere29,30,41, including the MATLAB codes used for these calculations46. Briefly, extension-time trajectories at constant trap separations were mean-filtered using a time window of 1–3 ms and then analyzed by two- or three-state HMM, which revealed probabilities and average extensions of all states and their associated transition rates. The corresponding idealized state transitions were calculated using the Viterbi algorithm. Methods to derive binding energy and kinetics in the presence and absence of membrane tethers were described elsewhere17. Briefly, the force-dependent free energy of each state was determined based on the Boltzmann distribution, while the binding and unbinding rates were calculated based on the Kramers equation. The associated parameters at zero force were obtained by simultaneously fitting the measured probabilities and extensions of all states and their transition rates using a nonlinear model30. Key formulae involved in the fitting are shown Eqs. 1–5 and Eq. 7 with V = 0 in this case in the forthcoming section, but with the measured force F. The positions of the energy barriers for C2 binding and unbinding (Δx in Eq. 5) are also chosen as fitting parameters.

Calculations of trans-membrane binding properties of E-Syts.

The average force (F) of each C2 binding state (Figs. 6b & 6d, middle panel) was calculated using the worm-like chain model33

| (1) |

where L and x are the total contour length and extension, respectively, of the stretched polypeptide linkers due to the trans-membrane binding, and P =0.6 nm is the persistence length of the polypeptide17. The contour length L was determined by the number of disordered amino acids between the N-terminal membrane attachment site and the beginning of the predicted C2 domain in the sequence of each protein construct as listed in Supplementary Information. The contour length per amino acid was chosen as 0.365 nm46. The extension was equal to the membrane separation (d) subtracted by the total length of rigid folded C2 proteins under tension in the pulling direction (h=2~6 nm)30. The total free energy of the tethered membranes (Et, Figs. 6b & 6d, bottom panel) was the sum of the entropic energy of the stretched polypeptide linkers (Estretch), the total C2-membrane binding energy, and the membrane repulsive energy (V). The entropic energy of the polypeptide was calculated based on the worm-like chain model30 with

| (2) |

To calculate the total C2-membrane binding energy, we distinguished membrane-bound C2 modules that are not loaded by the stretching force (e.g., E-Syt1 C2E in the bound state i in Fig. 6a) and those that are (e.g., E-Syt1 C2CD in the bound state i). The former has the membrane binding energy () and binding rate (kb) derived from the measured binding and unbinding rates corresponding to the isolated C2 module (kon and kub in Supplementary Table 2; Extended Data Fig. 9b) due to the tethering effect, i.e.,

| (3) |

where

| (4) |

is the effective concentration of a C2 module around the membrane17. Here, the C2 module is tethered to the membrane by a polypeptide linker with a contour length l, s=0.7 nm2 is the area per lipid, and NA =6.02×1023 per mole the Avogadro constant. For example, E-Syt1 C2E in the bound state i in Fig. 6a has l=25.6 nm (Fig. 1a). The membrane binding parameters of the force loaded C2 module are modulated by both the tethering effect and the stretching force. The tethering effect was considered in the same way as the force unloaded C2 modules, but with a different contour length of the linker that connects the force loaded module to the ER membrane, which yielded the corresponding membrane binding rate (kb), and unbinding rate (kub) in the absence of force. In the presence of the stretching force, the binding rate, the unbinding rate, and the binding energy become

| (5) |

respectively, where Δx is the distance between the location of the energy barrier for the binding and unbinding transition state and the location of the energy well for the bound state determined from the pulling experiment30 (Extended Data Fig. 9b).

The repulsive force or potential between ER and PM is complex and has not been measured39,47. For simplicity, we modeled the repulsive potential V as a function of membrane distance d as

| (6) |

where Em =35 kBT, dc =1 nm, and d1 =10 nm48. Thus, the total energy of the E-Syt-tethered membranes was calculated as

| (7) |

as shown in Figs. 6b and 6d, bottom panel. Except for , all energy terms here are functions of membrane separation d. In addition, the first three terms are state-dependent. Finally, the state populations were computed based on the Boltzmann distribution (Figs. 6b & 6d, top panel). The associated MATLAB codes can be found at https://github.com/zhanglabyale/E-Syt_membrane_tethering_simulation.

Reporting summary.

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this work are deposited in https://github.com/zhanglabyale/E-Syt_membrane_tethering_simulation.

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1. Representative proteins that contain multiple C2 domains.

The lengths (a.a.) of the predicted disordered linkers that join different protein domains or membranes are indicated.

Extended Data Fig. 2. Two conserved membrane binding motifs in the C2 domains of synaptotagmins (Syts) and extended synaptotagmins (E-Syts).

Alignments of the C2 amino acid sequences showing two conserved membrane binding motifs highlighted in bold and color: the Ca2+-binding motif (blue) and the basic patch (red).

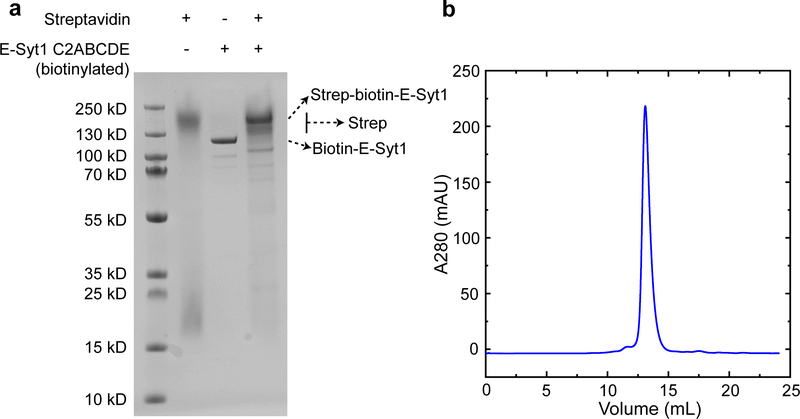

Extended Data Fig. 3. The purified E-Syt1 C2ABCDE was sufficiently pure and biotinylated.

(a) SDS-PAGE of the purified E-Syt1 C2ABCDE stained with Coomassie blue. Streptavidin maintained its tetrameric structure in the SDS gel when it was loaded to the gel without heating to high temperature. Binding of streptavidin to the biotinylated E-Syt1 C2ABCDE shifted the migration of C2ABCDE to a position with a higher molecular weight. (b) Gel filtration chromatogram of E-Syt1 C2ABCDE in a Superdex-200 column. Similar results were obtained from three batches of purified proteins.

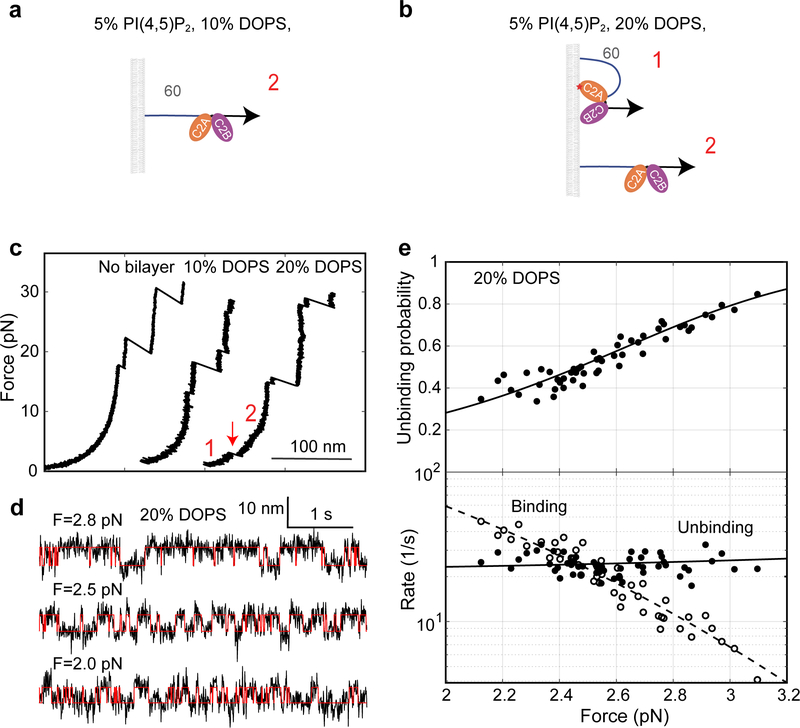

Extended Data Fig. 4. E-Syt1 C2AB only weakly binds to membranes enriched with negatively charged lipids.

(a, b) Diagrams showing no binding (a) and weak binding (b) of the E-Syt1 C2AB domain in the presence of 10% and 20% DOPS, respectively. (c) Force-extension curves showing no membrane binding of E-Syt1 C2AB domain in the absence of supported bilayer or in the presence of the supported bilayer containing 10% DOPS. Weak binding was detected in the presence of 20% DOPS, as indicated by the rip at low force (red arrow). (d) Extension-time trajectories at constant forces (black curves) and their idealized transitions derived from hidden-Markov modeling (red curves). (e) Unbinding probability and binding and unbinding rates (symbols) and their best model fits (lines). The fitting revealed an unbinding energy of 4.4 (±0.3) kBT for the E-Syt1 C2AB domain (Supplementary Table 2).

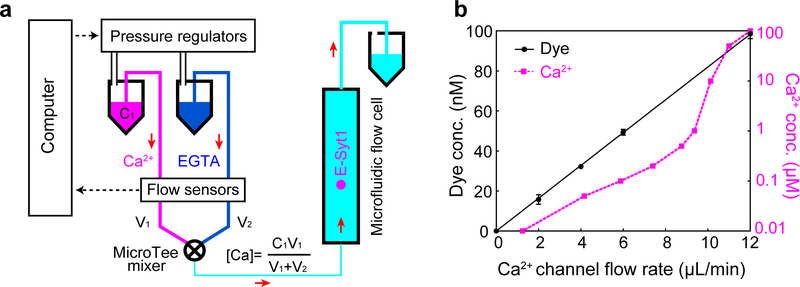

Extended Data Fig. 5. The microfluidic system to facilitate changes of the Ca2+ concentration in the single-molecule manipulation experiment.

(a) Schematics of the microfluidic system to change Ca2+ concentration when a single C2 repeat was being pulled. Two buffers containing 200 mM NaCl, 25 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, and 500 μM EGTA were prepared, one with CaCl2 (Ca2+ buffer) and another without CaCl2 (EGTA buffer). The two buffers were flowed through a mixer into the central flow cell. The two flows were independently controlled using computer-controlled pressure regulators (MS4-LR, Festo, NY) in combination with flow sensors (SLI-0430, Sensirion, Switzerland) that measure the flow rates. The constant flow rate was achieved by adjusting the pressure in the buffer vial through PID feedback control using a LabVIEW interface. The total calcium concentration in the flow cell ([Ca]), which consisted of both free and EGTA-chelated calcium, was determined by the total calcium concentration of the Ca2+ buffer ([Ca]=V1) and volume velocities of the two buffers (V1 and V2) before mixing. The free Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]) in the flow cell was calculated using Maxchelator (Web version v1.2) based on the total concentrations of calcium and EGTA. (b) The measured tracing dye concentration and predicted free Ca2+ concentration in the flow cell as the flow rate of the Ca2+ channel linearly increased from 0 to 12 μL/min while keeping the total flow rate of the two channels at 12 μL/min. To test the concentration change scheme, we added 100 nM rhodamine dye to the Ca2+ buffer and detected the concentration of the dye in the flow cell based on its fluorescence intensity measured by widefield fluorescence microscopy. We linearly increased the flow rate of the rhodamine-containing Ca2+ buffer from 0 to 12 μL/min and simultaneously decreased the flow rate of the EGTA buffer to keep the total flow rate of the two buffers to be 12 μL/min. The dye concentration linearly increased as expected, which justified our concentration change scheme. However, although the observation implied that the total calcium concentration in the flow cell varied linearly as predicted, the corresponding free Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]) responded in a nonlinear manner due to the buffering effect of EGTA. Combining with the flow control system, we detected C2 membrane binding transitions at constant force while changing Ca2+ concentration either continuously in the presence of a flow or stepwise in the absence of flow. While the former method allowed rapid [Ca2+] change at the expense of slight extra noise in force and extension measurements, the latter method permitted more accurate single-molecule measurement in the absence of flow after each [Ca2+] change (Fig. 4).

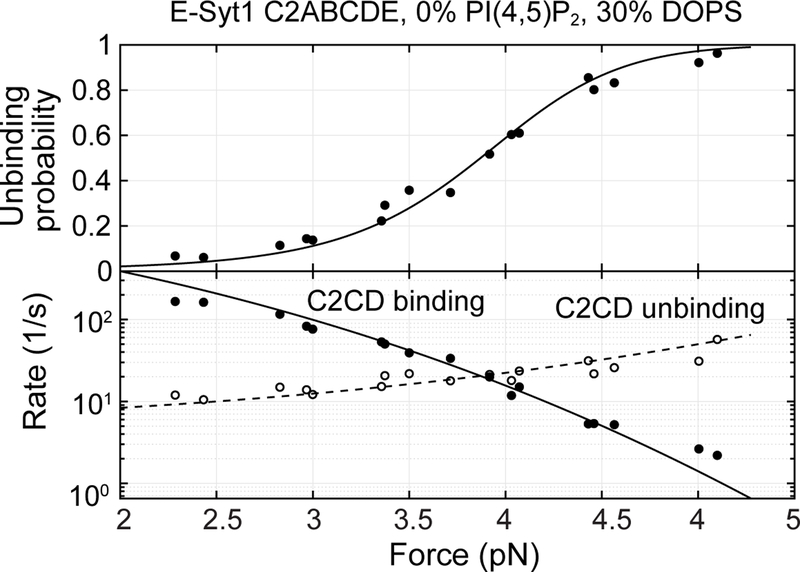

Extended Data Fig. 6. E-Syt1 C2ABCDE binds to the membrane containing 30% DOPS and 0% PI(4,5)P2 via its C2CD domain, but not its C2E domain.

C2CD unbinding probability (top panel) and binding and unbinding rates (bottom panel) as a function of force. The experimental data (symbols) were fit by a nonlinear model to yield the best-fits (lines).

Extended Data Fig. 7. E-Syt2 C2C undergoes a reversible force-dependent, but Ca2+-independent conformational change to inactivate its membrane binding.

(a-c) Extension-time trajectories at constant force in the absence (a) and presence (b) of Ca2+ for E-Syt2 C2ABC or in the presence of Ca2+ for E-Syt2 C2C (c). The long gaps in the unbound state highlighted blue represent the binding inactive state. (d) Diagram of the conformational transition of the C2 domain in the binding active and inactive states.

Extended Data Fig. 8. Cytosolic E-Syt1 containing the SMP domain binds to membranes in a manner like its C2 repeat C2ABCDE.

(a) Schematic diagram showing different E-Syt1 binding states. (b) Force-extension curves obtained by pulling E-Syt1 under different conditions. (c) Extension-time trajectories of E-Syt1 at constant force in the presence or absence of Ca2+.

Extended Data Fig. 9. Calculations of equilibrium membrane distance and membrane binding energy and kinetics.

(a) Diagram illustrating the equilibrium membrane distance determined by the balanced membrane repulsive force (Eq. 6 in the main text) and E-Syt tethering force (Eq. 1). The equilibrium distance was solved as a solution for the system of equations where V' is the derivative of V(d) and h is the total length of the folded C2 modules in the pulling direction30 (estimated as 2 nm for each C2 module5,22). (b) Energy landscape corresponding to the C2-membrane interaction with the C2 module free in the solution (blue curve), tethered to the membrane by a flexible and relaxed polypeptide linker (black), or tethered to the membrane with a stretched linker (red). The three key parameters of the energy landscape associated with the free C2 module are determined from our single-molecule measurements (Supplementary Table 1). The energy landscape with the tethered and relaxed C2 module (corresponding to the force-unloaded C2 module) is determined by Eq. 3, with an effective concentration of the C2 module around the membrane estimated by Eq. 4. Note that the tethering does not affect the unbinding rate of the C2 module17. Stretching the bound C2 module by moving the PM membrane away from the ER membrane increases the energy barrier for C2 binding by Estretch and decreases the energy barrier for C2 unbinding by FΔx as indicated by Eq. 5.

Extended Data Fig. 10. Calculated state probabilities, forces, and energy as a function of membrane separation due to potential trans-membrane binding of E-Syt1 (left panel) and E-Syt2 (right panel) lacking a membrane-binding C-terminal C2 module.

(a, c) Schematics of different C2 binding and membrane tethering states in the absence and presence of Ca2+ for E-Syt1 (a) or E-Syt2 (c). The calculations were to simulate the results of membrane contact formation from in vivo imaging using E-Syts with mutant C-terminal C2 domains (C2E in E-Syt1 or C2C in E-Syt2 and E-Syt3) that did not bind to membranes or with the domains truncated. (b, d) Calculated probabilities (top panel), average stretching force (middle), and free energy (bottom) of different states for truncated E-Syt1 (b) or E-Syt2 (d). Calculations corresponding to the presence of Ca2+ or the absence of Ca2+ are indicated by solid and dashed lines, respectively, with their colors indicating different states as shown in a or b: red for the bound state I and black for the unbound state iii. Stable and unstable states are indicated by solid and hollow circles, respectively. The derived equilibrium distances and free energy are shown in Supplementary Table 3.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank J. Jiao and A. Rebane for technical assistance. This work was supported by NIH grants R35GM131714, R01GM093341, and R01GM120193 to Y. Z.; R01NS113236 to E.K.; NS36251 and DA018343 to PDC.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Supplementary information is available for this paper.

References

- 1.Lemmon MA Membrane recognition by phospholipid-binding domains. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Bio. 9, 99–111 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hurley JH Membrane binding domains. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1761, 805–11 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pinheiro PS, Houy S & Sorensen JB C2-domain containing calcium sensors in neuroendocrine secretion. J. Neurochem. 139, 943–958 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bian X, Saheki Y & De Camilli P Ca2+ releases E-Syt1 autoinhibition to couple ER-plasma membrane tethering with lipid transport. EMBO J. 37, 219–234 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu JJ et al. Structure and Ca2+-binding properties of the tandem C2 domains of E-Syt2. Structure 22, 269–280 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pangrsic T, Reisinger E & Moser T Otoferlin: a multi-C2 domain protein essential for hearing. Trends Neurosci. 35, 671–680 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Min SW, Chang WP & Sudhof TC E-Syts, a family of membranous Ca2+-sensor proteins with multiple C2 domains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 3823–3828 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saheki Y & De Camilli P The extended-synaptotagmins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1864, 1490–1493 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lek A, Evesson FJ, Sutton RB, North KN & Cooper ST Ferlins: regulators of vesicle fusion for auditory neurotransmission, receptor trafficking and membrane repair. Traffic 13, 185–94 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giordano F et al. PI(4,5)P2-dependent and Ca2+-regulated ER-PM interactions mediated by the extended synaptotagmins. Cell 153, 1494–1509 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang CL et al. Feedback regulation of receptor-induced Ca2+ signaling mediated by E-Syt1 and Nir2 at endoplasmic reticulum-plasma membrane junctions. Cell Rep. 5, 813–825 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saheki Y & De Camilli P Endoplasmic reticulum-plasma membrane contact sites. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 86, 659–684 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saheki Y et al. Control of plasma membrane lipid homeostasis by the extended synaptotagmins. Nat. Cell Biol. 18, 504–515 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu HJ et al. Extended synaptotagmins are Ca2+-dependent lipid transfer proteins at membrane contact sites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 4362–4367 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao HX & Lappalainen P A simple guide to biochemical approaches for analyzing protein-lipid interactions. Mol. Biol. Cell 23, 2823–2830 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Knight JD, Lerner MG, Marcano-Velazquez JG, Pastor RW & Falke JJ Single molecule diffusion of membrane-bound proteins: window into lipid contacts and bilayer dynamics. Biophys. J. 99, 2879–87 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ma L et al. Single-molecule force spectroscopy of protein-membrane interactions. Elife 6, e30493 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nath VR, Mishra S, Basak B, Trivedi D & Raghu P Extended synaptotagmin regulates membrane contact site structure and lipid transfer function in vivo. EMBO Rep. 21, e50264 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fernandez-Busnadiego R, Saheki Y & De Camilli P Three-dimensional architecture of extended synaptotagmin-mediated endoplasmic reticulum-plasma membrane contact sites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, E2004–13 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Idevall-Hagren O, Lu A, Xie B & De Camilli P Triggered Ca2+ influx is required for extended synaptotagmin 1-induced ER-plasma membrane tethering. EMBO J. 34, 2291–305 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kang F et al. E-syt1 re-arranges STIM1 clusters to stabilize ring-shaped ER-PM contact sites and accelerate Ca2+ store replenishment. Sci. Rep. 9, 3975 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schauder CM et al. Structure of a lipid-bound extended synaptotagmin indicates a role in lipid transfer. Nature 510, 552–555 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bian X, Zhang Z, Xiong QC, De Camilli P & Lin CX A programmable DNA-origami platform for studying lipid transfer between bilayers. Nat. Chem. Biol. 15, 830–+ (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li PQ, Lees JA, Lusk CP & Reinisch KM Cryo-EM reconstruction of a VPS13 fragment reveals a long groove to channel lipids between membranes. J. Cell Biol. 219, e202001161 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wong LH, Gatta AT & Levine TP Lipid transfer proteins: the lipid commute via shuttles, bridges and tubes. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Bio. 20, 85–101 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Corbalan-Garcia S & Gomez-Fernandez JC Signaling through C2 domains: More than one lipid target. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1838, 1536–1547 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Veggiani G et al. Programmable polyproteams built using twin peptide superglues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 1202–1207 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Min D, Jefferson RE, Bowie JU & Yoon TY Mapping the energy landscape for second-stage folding of a single membrane protein. Nat. Chem. Biol. 11, 981–987 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang YL, Jiao J & Rebane AA Hidden Markov modeling with detailed balance and its application to single protein folding Biophys. J. 111, 2110–2124 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rebane AA, Ma L & Zhang YL Structure-based derivation of protein folding intermediates and energies from optical tweezers. Biophys. J. 110, 441–454 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steinkuhler J et al. Membrane fluctuations and acidosis regulate cooperative binding of ‘marker of self’ protein CD47 with the macrophage checkpoint receptor SIRPα. J. Cell Sci. 132, jcs216770 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weikl TR, Hu JL, Kav B & Rozycki B Binding and segregation of proteins in membrane adhesion: theory, modeling, and simulations. Adv Biomembr Lipid 30, 159–194 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marko JF & Siggia ED Stretching DNA. Macromolecules 28, 8759–8770 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krishnamurthy VM, Semetey V, Bracher PJ, Shen N & Whitesides GM Dependence of effective molarity on linker length for an intramolecular protein-ligand system. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 1312–1320 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shen H, Pirruccello M & De Camilli P SnapShot: membrane curvature sensors and generators. Cell 150, 1300, 1300 e1–2 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ross TD et al. Integrins in mechanotransduction. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 25, 613–618 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Basu R et al. Cytotoxic T cells use mechanical force to potentiate target cell killing. Cell 165, 100–110 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weikl TR Membrane-mediated cooperativity of proteins. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 69, 521–539 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sheetz MP Cell control by membrane-cytoskeleton adhesion. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Bio. 2, 392–396 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brownell WE, Qian F & Anvari B Cell membrane tethers generate mechanical force in response to electrical stimulation. Biophys. J. 99, 845–852 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jiao JY, Rebane AA, Ma L & Zhang YL Single-molecule protein folding experiments using high-resolution optical tweezers. Methods Mol Biol 1486, 357–390 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moffitt JR, Chemla YR, Izhaky D & Bustamante C Differential detection of dual traps improves the spatial resolution of optical tweezers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 9006–9011 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sirinakis G, Ren YX, Gao Y, Xi ZQ & Zhang YL Combined and versatile high-resolution optical tweezers and single-molecule fluorescence microscopy. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 83, 093708 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang YL, Sirinakis G, Gundersen G, Xi ZQ & Gao Y DNA translocation of ATP-dependent chromatin remodelling factors revealed by high-resolution optical tweezers. Methods Enzymol. 513, 3–28 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gittes F & Schmidt CF Interference model for back-focal-plane displacement detection in optical tweezers. Opt. Lett. 23, 7–9 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gao Y et al. Single reconstituted neuronal SNARE complexes zipper in three distinct stages. Science 337, 1340–1343 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cowley AC, Fuller NL, Rand RP & Parsegian VA Measurement of repulsive forces between charged phospholipid bilayers. Biochemistry-Us 17, 3163–3168 (1978). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zorman S et al. Common intermediates and kinetics, but different energetics, in the assembly of SNARE proteins. Elife 3, e03348 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this work are deposited in https://github.com/zhanglabyale/E-Syt_membrane_tethering_simulation.